1. Introduction

Yaeyaman is one of six indigenous languages of the Ryukyuan Archipelago. These languages are the only known languages related to Japanese and are classified as sister languages to Japanese in what constitutes the Japonic language family (

Pellard 2015). Ryukyuan languages had long been studied as dialects of Japanese until they were recognized as languages in the UNESCO

Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger (

Mosely et al. 2010). Yaeyaman and its closest relative language Dunan (on Yonaguni Island) are both classified as ‘severely endangered.’ Linguistically, Yaeyaman is about 70% cognate with Japanese, a rate similar to the difference between French and Spanish; however, the lack of an established orthography means that both oral and written communication are mutually unintelligible. This extends to certain varieties within Yeayama, which are also unintelligible to speakers of other Yaeyaman varieties. While the remaining speakers of Yaeyaman are literate in Japanese, Yaeyaman has never been popularly written.

As can be seen in

Table 1, there has been a recent increase in descriptive research regarding Yaeyaman with linguists building on the groundbreaking work of

Miyara (

1995) and

Suzuki et al. (

2001). Currently, comprehensive dictionaries exist for Hatoma, Taketomi, Kohama and Ishigaki Shikāza. Grammars and Grammar Sketches are now available for Miyara, Hateruma, Kuro, Shikāza, Shiraho, Taketomi, Funauki and Sonai with more descriptive work being carried out by graduate students every year. On the sociolinguistic front,

Hammine (

2019,

2020,

2021,

2022) has provided many valuable insights into the sociolinguistic situation in Yaeyama.

Life for a typical Yaeyaman became more difficult following the 1609 defeat of the Ryukyuan Kingdom by the Satsuma Clan of Kyushu in mainland Japan. This led to the levying of a heavy poll tax on the people in 1640 that limited travel and often led to forced migrations within Yaeyama and from other parts of Okinawa to collect enough revenue after villages were destroyed by natural disasters, famine, typhoons, or malaria.

In the 19th century, there were an estimated 27 local varieties of Yaeyaman (

Takahashi 2009). Within 30 years of the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in 1879, the Ryukyuan languages had been labeled as ‘dialects’ of Japanese and an orchestrated language education policy began to gradually increase efforts to ban their use outside of school as well (

Anderson 2019). Today, Yaeyaman has been primarily replaced by Japanese in almost all domains of use, with most people born after 1970 having been raised as monolingual Japanese speakers (

Heinrich 2012).

Currently there are approximately 18 varieties in the Yaeyaman Archipelago (

Figure 1), all of which are severely endangered; nine varieties appear to have been lost in the 20th century. There remain eight varieties of Yaeyaman on Ishigaki Island, four on Iriomote Island, and one on each of Aragusuku, Hatoma, Hateruma, Kohama, Taketomi, and Kuro (

Aso 2015). All remaining 18 varieties still have very proficient speakers, based on the precept that anyone born before 1940 has a high probability of being a full speaker.

1According to current demographic data, there were 2555 residents born between 1931 and 1941, and 799 born in 1930 or before within Ishigaki City (

JD Freak! 2022a,

2022b). In Taketomi Town, there are 211 residents born between 1931–41 and 134 born in or before 1930. This gives a total of approximately 3699 full speakers of one or more of the eighteen varieties. In view of current life expectancies, these statistics also suggest that there will be fewer than 1000 speakers remaining ten years from now. Note, however, that there are also some speakers of Yaeyaman that have emigrated to Okinawa Island, to mainland Japan, to Hawaii, or to the Americas. Regardless of the exact number of remaining speakers, the situation is alarming.

However, the fate of the Yaeyaman language has never simply been at the hands of mainland Japanese policies. The effect of mental colonization (

Fanon and Philcox 2004) led local governments and teacher associations to value (only) the Japanese language and to unequivocally identify as Japanese, marginalizing in so doing their own heritage language and culture. The message that Yaeyaman was for the past and not to be valued eventually undermined their confidence in their identity and led to a psychological dependance on being Japanese.

Hammine (

2022) surmises, “it was the Ryukyuan people themselves who chose to pursue a Japanese identity by reverting to Japanese. Perhaps, after being colonized by two nations, Japan and America, it was considered a better choice to abandon their Indigenous languages and speak Japanese in order to become Japanese. Perhaps, Ryukyuans were eager to escape discrimination, ostracism, or marginalization, fearful of being treated as second-class citizens by the Japanese.” Their experience often compelled them to become the main proponents of language shift in the second half of the 20th century, the most prescient example being during the occupation when the US military’s recommendation that the Okinawans return to using their own languages was rebuked by local government officials (

Gillan 2012).

As language shift to Japanese escalated so did the replacement of local conceptualizations in the language with concepts inherent to Japanese. While step-by-step details of how language shift and loss took place in the Ryukyus is now well-documented (

Anderson 2019), no attention has been paid so far to local concepts such as the orientation system or seasonal expressions of Yaeyaman that are on the verge of disappearing.

I interviewed four full speakers (X, Y, A, B). All four speakers saw the loss of their language as unavoidable and as a natural process of the flow of time. Most also expressed feelings indicating they thought this loss was regrettable, but A, the first woman to be head of her local Azakai council, admitted that she only began to feel that way in the last ten years. On the other hand, X insisted she did not feel the loss of the language even amounted to as much as a regret, nantomo omowanai ‘I don’t think anything of it.’ Three of the rusty speakers in their sixties all told me similar things such as D, who stated “We were raised to think it was bad to speak sumamuni ‘island language’. It was dirty and Japanese was beautiful.”

This negative attitude towards their language is constantly being reenforced by their own words voluntarily calling it

hōgen ‘dialect’. The dictionary, a treasure that Miyagi Shinyū devoted much of his later life, is titled

Ishigaki Hōgen Jiten ‘Ishigaki Dialect Dictionary’ (

Miyagi 2003). The way in Yaeyaman to overcome saying the word dialect,

sumamuni is itself listed in the dictionary as

hōgen ‘dialect’ in Japanese. In a world where the impact of words is so clearly understood such that ‘he’ and ‘man’ are quite rightly no longer used to refer to people generally (to give but one gender asymmetric and exclusive language example), the fact that also those who are active in the efflorescence of Yaeyaman themselves continue to use the word

hōgen is problematic as the use of this terminology effectively undermines their cause.

One additional point of concern that reflects the people of Yaeyama and their complicated attitude towards their language is the complete lack of any literature outside of the documentation of folk songs and folk tales. While Yaeyama is blessed with a rich tradition of music, song, and stories, all of which are still proudly performed and offer the people a space where they can use their heritage language (

Gillan 2012), no other work has been produced in Yaeyaman. That one could grow up speaking a language with friends and family yet accept it to be natural that at school one must learn to read and write Japanese is evidence of linguistic colonization, and that upon learning to read and write, you accept to not aspire to write in your own language is an effect of the colonization of the mind. This results in the belief that their language truly is a dialect, and therefore not fit for literature. A, herself with four published books of haiku and a celebrated carrier as a calligraphy instructor, insisted that she never thought to write in her own language.

“No, there was no way I would ever think to write in sumamuni, we were all told that things from the past were bad and that it was time to modernize. I remember that from when I was a kid. They told me the old ways and speaking sumamuni were bad so I just believed them. So rather than thinking to say write in sumamuni, or that sumamuni was something of value, I just thought that sumamuni was bad, furui mono wa dame dakara (because everything that is old is bad).”

The picture that emerges from such accounts is that Ishigaki Yaeyaman is a language for the illiterate, best forgotten. Furthermore, old is seen as a problem if we are dealing with the Ryukyus. After this brief introduction, let us next turn to nonconformist concepts about space in Yaeyaman.

2. Nonconformist Concepts

Nonconformist concepts are ways of seeing and describing the environment that differ from our modern notion of the world. Modern global concepts have been spread through societies by formal education and mass media and from monolingualized nation-states to the colonized or otherwise dominated parts of the world. Japanese and Korean are two widely spoken modern languages that still show some window into other ways of communication and cognition (

Evans 2010, p. 74). Their patterns such as a requirement to explicitly state that one cannot be certain of another’s inner thoughts and feelings and is only speculating (…sō

2 desu/…gatte) reveal differences in expression that help to push back against the calls of universalists to attach limits and rules to the range of human communication (

Evans 2010, p. 180). However, Japanese and Korean are now largely modernized. It is only when linguists look to the periphery, at many of the 3000 endangered languages, where some clues as to the expanse of diversity in our language patterns, and the thoughts and cultural views behind them can be exposed.

Further compounding the loss of nonconformist concepts is that, often, the remaining fluent speakers have adapted to life using another language and forget these knowledge systems as they are no longer applicable in their current circumstances (

Brenzinger 2006,

2007). Newcomers looking to learn the language may often be primarily motivated by purposes such as to spread a religion and often fail to look for these original concepts. Additionally, large personal sacrifices are required to acquire fluency in and document the language and stories of peoples often living in remote, inhospitable, or war-torn places. Still, some people do so. Daniel Everett, for example, has devoted over 30 years of his life to living in the center of the Amazon rain forest documenting the Pirahã people. His work describing Pirahã communication has revealed holes in the previously thought to be universal theories for human phonetics and grammar. These were the long-held theories from prominent linguists such as Ladefoged and Chomsky concerning what were thought to be the universal limits on induction and that recursion was a requirement of and main distinction between human communication and other animals (

Everett 2009, pp. 215–40).

3In work similar to that of Everett, new discoveries of language and nonconformist concepts generally come hand in hand. They pose new questions into how language, cognition, and culture impact each other (

Traxler 2012;

Evans 2010). In response to the threat of significant linguistic diversity loss, linguists in growing numbers have made progress in finding more examples of the unique and unexpected ways humans can communicate. This has, for example, had a major influence on the study of evidentiality, including the immediacy of experience principle (

Dixon 2016, pp. 91–94)

4. It may be the case that cognition and language diversity are infinite in variation but many pieces to the picture are becoming increasingly more difficult to find.

3. Orientation Systems

Frames of reference, how humans indicate location, also known as orientation systems, are one aspect of communication long thought to be universal until

Stephen Levinson (

2003) and others began to report on the wide variety of ways people orient themselves in the world. These systems are usually divided into four types: from the perspective of the speaker (right and left); from the perspective of the object (front, back, and side); based on a geographical landmark such as a river, mountain, or coastline (toward/away from the mountain/coast up/down river); and absolute directions (east, west, north, and south). Different ways to give directions have been documented around the globe, including

Michael Fortescue’s (

2011) mapping of the North Pacific Rim and

Bill Palmer’s (

2007) work in Oceania to name only a two. We now have documented a wide variety of systems humans use for referring to space in contrast to the conformist modern concept of orientation in most of the developed world, which is primarily based on the perspective of the speaker (right, left, or strait). For over a millennium it had been assumed that using right and left were fundamental to being human in western philosophy (

Evans 2010, p. 162). Japanese people have adopted the modern concept of using left and right although cardinal directions are still used more in the certain parts of the countryside and on street signs and advertisement hoardings on highways.

In the Ryukyuan context, although Yaeyaman possesses a rather distinct orientation system, Yaeyaman, or any other systems in the Ryukyus, have hardly been documented at all, with the only existing research on Ishigaki collected and conducted on Ishigaki substrate Japanese.

Takekuro (

2007, p. 414) proposes that the reason for ignoring the local language in her study is ‘no instance of the terms spoken in the Yaeyama dialect was found during my data collection.’ This argument is partly true, as I also found a number of the rusty speakers under 70 unable to use the system and hesitant to use Yaeyaman to explain directions as it may likely lead to confusion. One highly fluent rusty speaker said, “there are lots of people out there and we don’t always know who might understand our language so if I try and give directions in

sumamuni I am probably just making things more complicated.” The explanation for this attitude of willingness to accommodate to the Japanese by Yaeyaman speakers can be found in Communication Accommodation Theory (CAT) (

Dragojevic et al. 2016).

CAT is a theory that describes the ways that humans alter the way they communicate with different people generally to improve the relationship or to create distance. According to CAT, all humans adjust some or all aspects of their communication to be more similar to or less similar to the person they are addressing, including linguistic (language, tone, accent, speech rate), paralinguistic (pauses and utterance length) and non-verbal elements (eye movement, smiling gesture, and gazing) to either remain unchanged, be more, or less, similar to their interlocutor (

Dragojevic et al. 2016). Convergent shifts in style, in the Yaeyaman context an upward, long-term, psychological language shift away from Yaeyaman towards Japanese, increases understanding, enhances interactional satisfaction, lowers the sense of social distance, and gives a positive impression to the interlocutor. Conversely, a divergent shift away from Japanese style speaking to when addressing native Japanese speakers gives a negative impression, increases the sense of social distance, and makes the communication mutually less intelligible. While convergent shifts to be more similar to the addressee bear benefits such as economic and socially upward opportunities, they have been found to lead to a loss of value in their own indigenous identity (

Marlow and Giles 2010).

5. The Yaeyaman Orientation System

The orientation systems in this paper are for Aragusuku and Shikāza Yaeyaman. Aragusuku is a pair of islands that after being evacuated

7 during the war, never recovered their former population. It is currently mostly uninhabited with only people originally from the island being allowed to travel there or bring guests. It does not have a Wikipedia page and the two full speakers and one rusty speaker who helped to explain their system reside on Iriomote Island. Full speaker B had never returned since taking refuge in Iriomote in 1944. Shikāza (

Figure 2) is the combination of four main districts of Yaeyaman that make up most of the dense urban center of Ishigaki city: Tonoshiro, Ōkawa, Ishigaki, and Arakawa districts. Many of the terms I collected throughout interviews were also listed in the Ishigaki dictionary. However, more interviews of more full and rusty speakers are necessary to fully confirm some of the conclusions in this article.

5.1. Inherent Landmark System

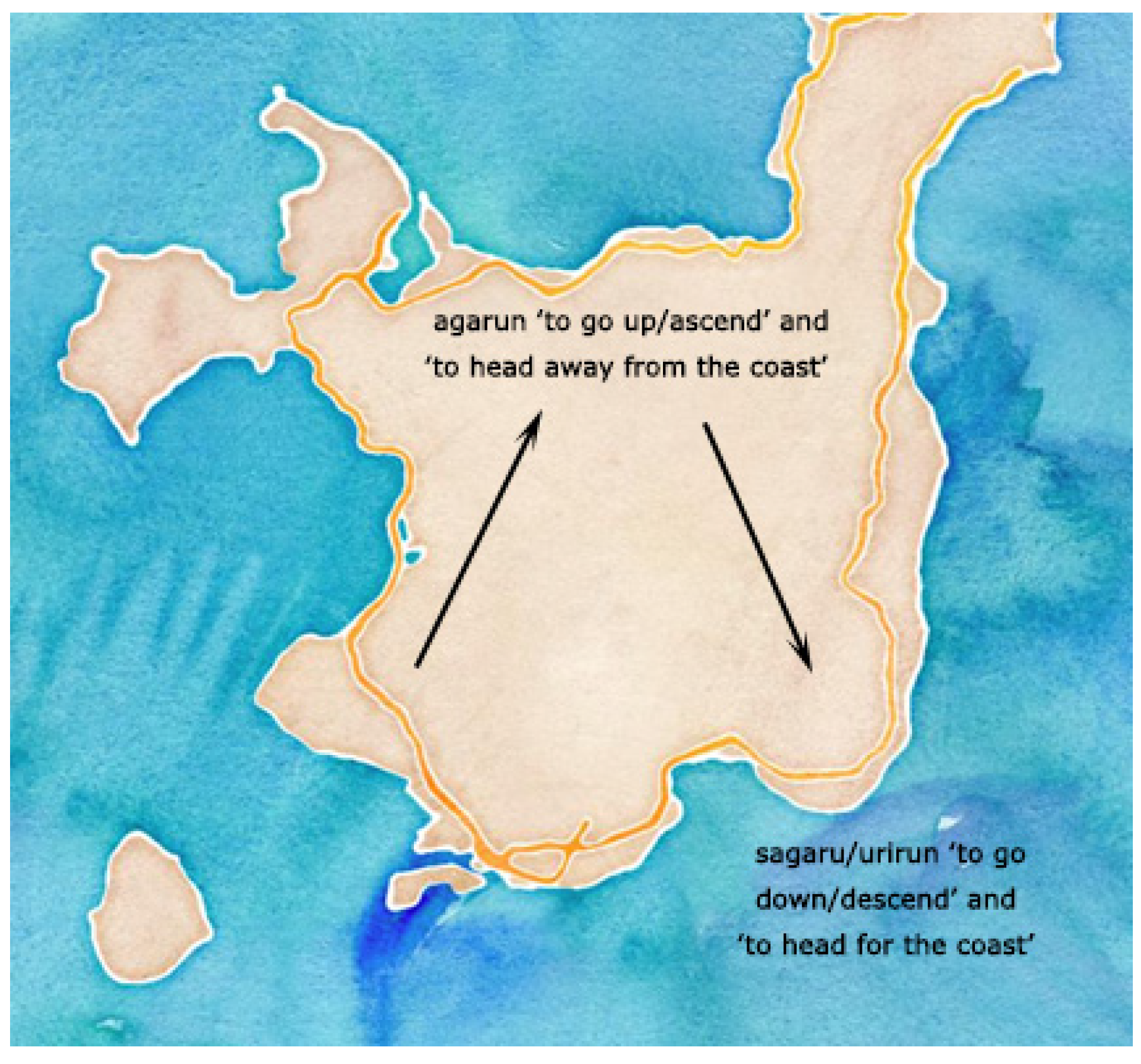

The Shikāza system includes a landmark based (inherent) expressions for heading towards the coast,

urirun/sagarun and heading away from the coast towards the mountains

agarun (

Figure 3). This is quite common with island societies though it has not been found in a lot of recent island settlements of creole languages (

Nash et al. 2020). Although rising or lowering elevation is implicit in these terms, they are used regardless of whether there is any change in elevation or not. While the more complex “object absolute” house-based system is more difficult for the rusty speakers to use, they often use the Japanese equivalents of the terms meaning heading up or heading down in replacement of standard Japanese words for straight, south, and north that a typical Japanese would use. C said, “I will use Japanese when giving street directions,

kita ni agate ’head up north’. So even though I have switched to Japanese, I will still say

yamagawa ni agaru toka ‘head up mountainward or’,

minami nara, umigawa ni sagaru toka ‘for south, head down oceanward’ for giving directions even though it is in Japanese.”

According to Z, this system does not exist in Aragusuku Yaeyaman, because both islands are so small and flat that one is essentially always heading towards a coast.

5.2. The House-Based System Inside the Home

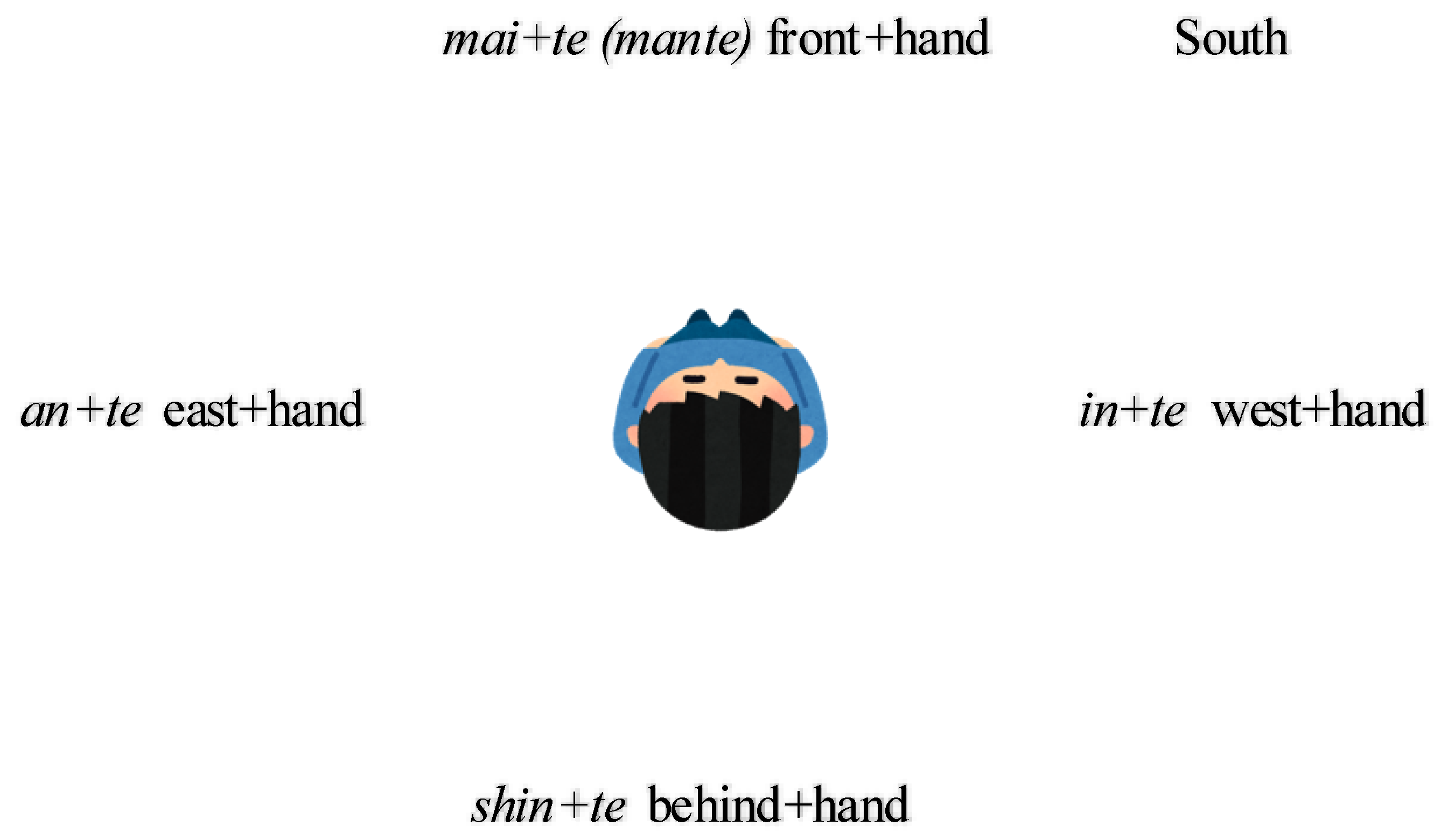

The most dominant orientation system used in Yaeyaman was found to be quite similar in Shikāza and Aragusuku. It is based around the home and can be used for relative reference in limited circumstances, inherent reference primarily, and can also be used as a way of referring somewhat to cardinal directions (absolute) outside of the home. Words for front, back, east, and west are given an ending depending on whether one is inside the home, talking about the surrounding homes, or outside of the neighborhood. It can also be used inherently to talk about the homes surrounding another home or shop.

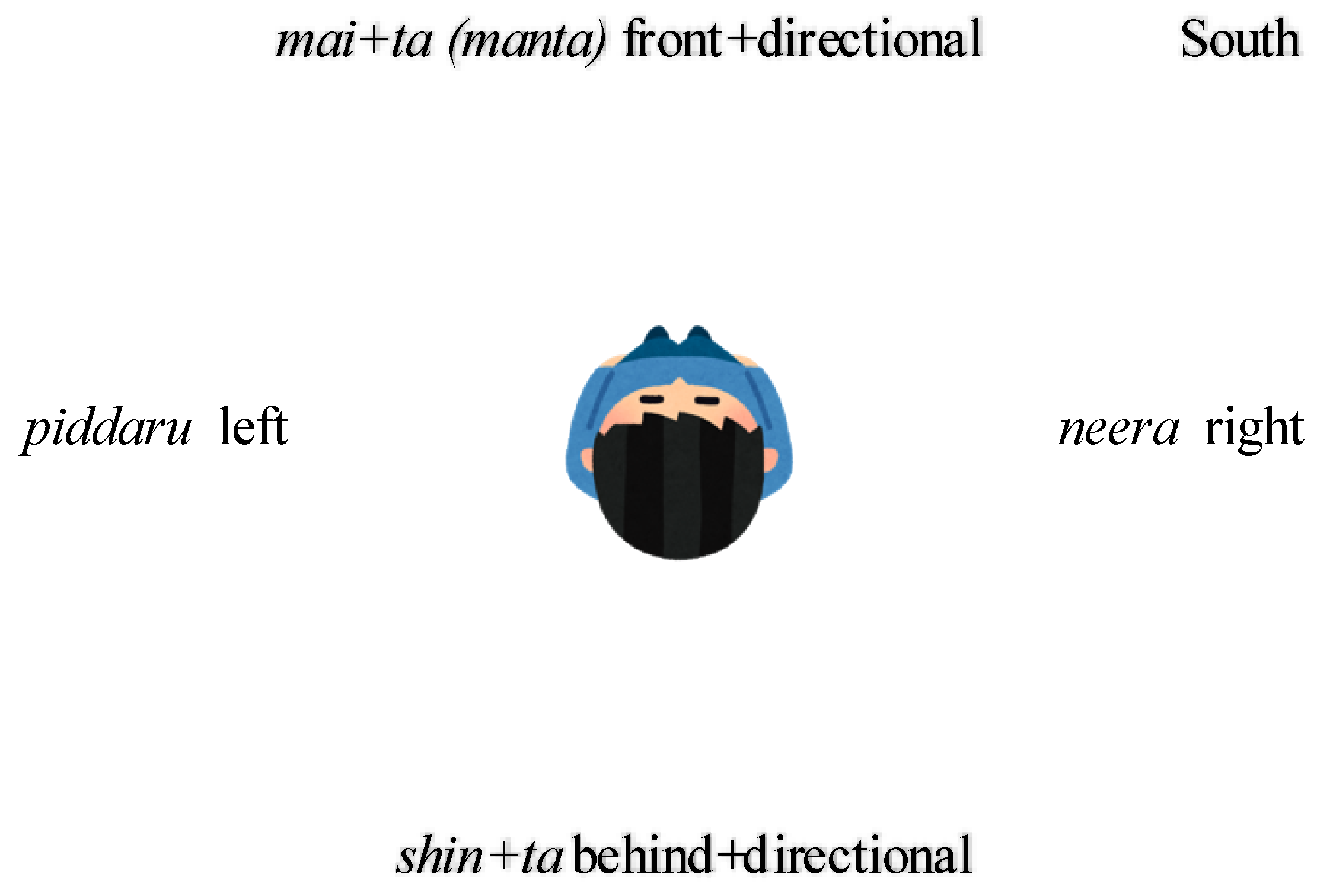

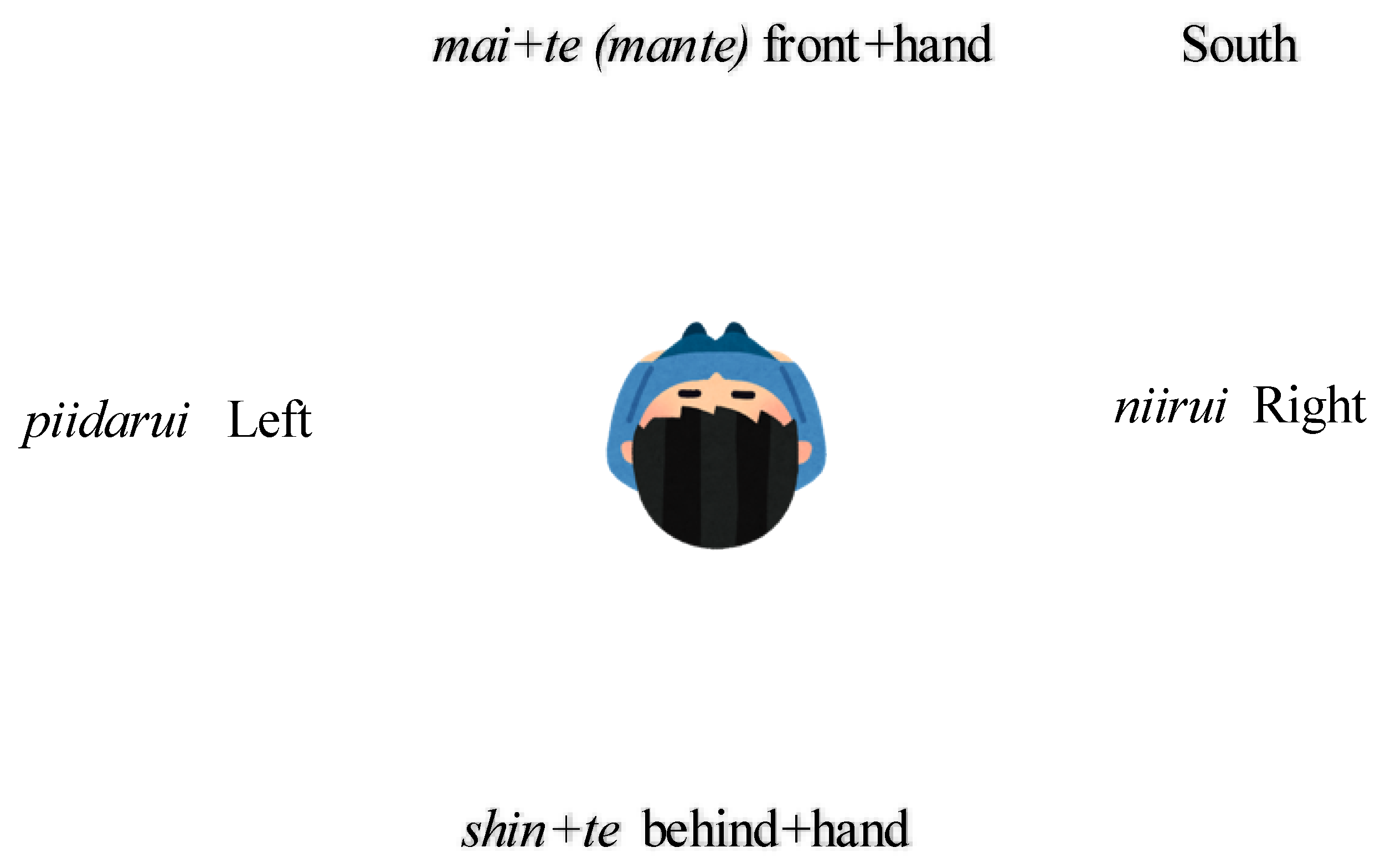

At the close at hand level, this system allows for the use of left and right (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The system can be used relatively to address an object in all four directions based on where the person is sitting or standing. The most common examples given in interviews were for pointing out where objects were in regard to another person based on the other person’s perspective, or for pointing out things directly in front or behind oneself. C, when asked if she used the ‘-

ta’ ending expressions, replied that while never using them outdoors, “I have sometimes used them to talk about in front of myself or behind myself.”

However, while at the close at hand level this system allows for relative reference, it generally is considered as a rule that everything is facing south. All of the houses, except for those in unfortunate circumstances, are built south facing, and all of the speakers I interviewed said that normally in the home you would also be sitting south facing. That is the rule, but especially front and back terms may be used from the perspective of the person when in the home or outside of the neighborhood.

The next stage of the system, inside the house but out of hands’ reach, can best be understood listening to the explanation of Z. “In Aragusuku for things inside the house shinte na munu ‘the thing right behind you’ and mante nu munu ‘the thing right in front of you’. But then inside the house you would use left and right for things near you because they are near your right and left hands. But if something is out of reach of your hands then you could say inte and ante for things to the east and west of you.”

This is also mirrored in the Shikāza system with

inta and

anta replacing the words for left and right. At this stage of the system, terms generally switch to being based on the house or as one sitting facing the south. If the toilet was in the back of the house one would use

shinte in Aragusuku and

shinta in Shikāza to express the location (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

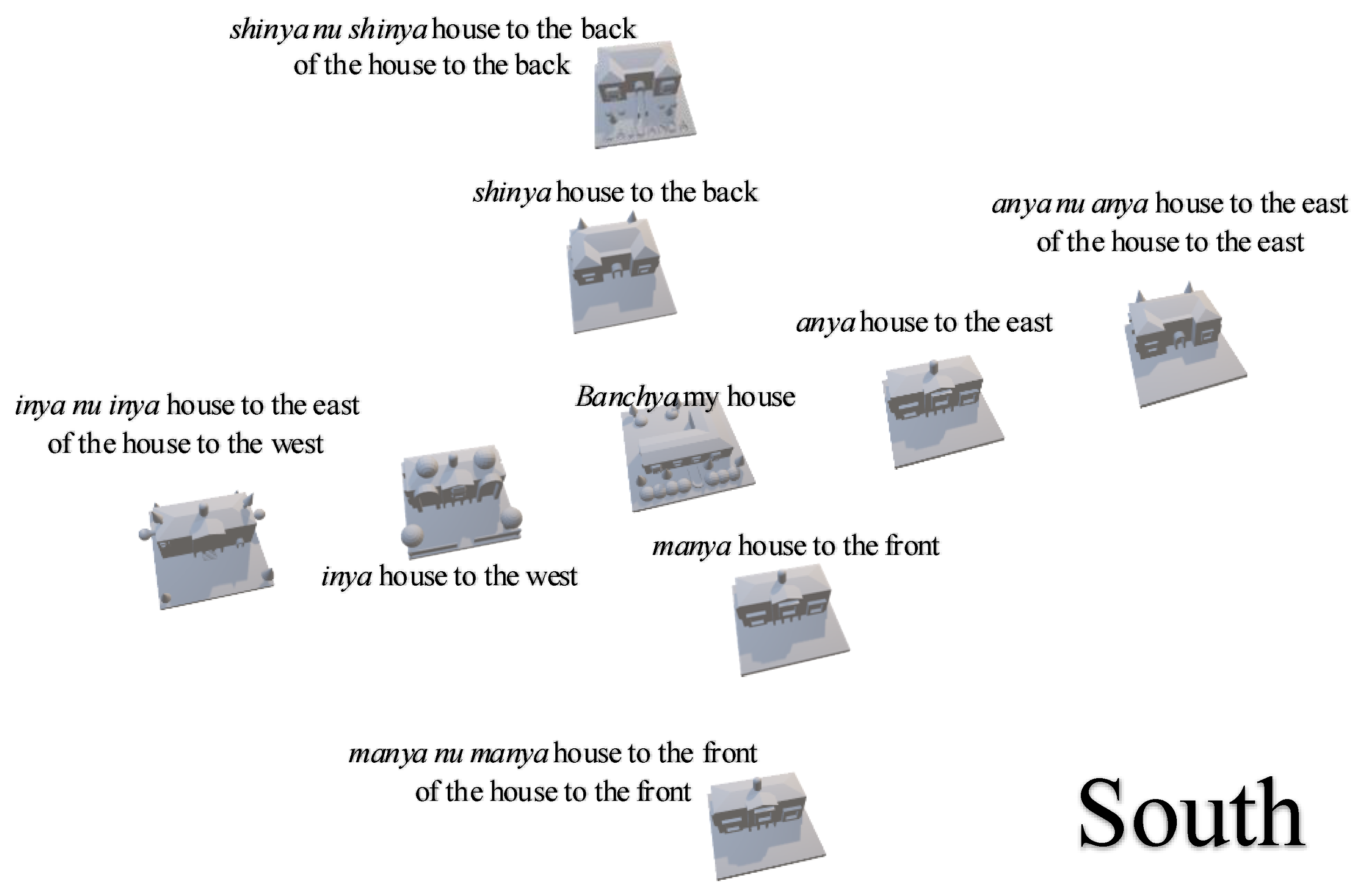

5.3. The House-Based System at Neighborhood Level

While most of the rusty speakers said they were able to use the inside expressions to some degree, they were all very familiar with and competent in the use of the system at house level for referring to the houses around one’s house (

Figure 8). This would appear to be at the heart of the system, and one the rusty speakers grew up hearing the most often when they were little compared to use of the system beyond the house. It can be assumed that this house-based way of envisioning one’s local community spread into giving directions both inside and outside of the home. It has the same set of prefixes for front, back, west, and east attached to the word for house

ya instead of the directional -

ta.

According to Z and B, if you happened to live in a house that was east or west facing, you would refer at all levels of the system based on your house’s direction as long as you were in or nearby your house. This meant using the east and west terms for south and north. As this is a rare case, to convincingly prove this, one would have to find one of these houses with full and rusty speakers to observe their conversations, which was beyond the scope of this project.

This system is always used in Yaeyaman to refer to the houses around one’s home. Quite commonly, the surrounding houses would be those of relatives but rather than saying ‘would you bring this over to your aunt’s house’ or ‘to your grandmother’s house’, ‘would you bring this over to’ and one of ‘inya, shinya, manya, anya,’ would be used. C recounts, “my mother would often say to me, hey bring this over to the manya or shinya. I used them a lot especially when I was younger. Probably every day.” She notes in other parts of the interview that all of the houses around her are of blood relatives. F recounts, “it is strange to me that the system uses front and back but then the cardinal directions east and west. To me the system doesn’t really make sense, but it is very natural for me to use it to talk about the houses around us with manya, inya, anya, and shinya.”

In addition to their use for the houses in the neighborhood, full Shikāza speaker B used the house terms when giving directions on the street for how to get to the nearest post office:

| shita=kai | uree-tte=yoo, | fuugaa+kooban=kai tsuki+ku-ba, |

| coast=ALL9 | descend-SEQ=FP | Ōkawa+police.box=ALL. arrive+come-CND2 |

| ‘Head down descending yeah, when (you) get to Fuugaa police box |

| |

| unyaa=nu | manyaa=haa” |

| that.house=GEN | front.house=FP |

| (it’s the) house in front of (it).’ |

Unya nu manya ‘the house in front of that house’ is the expression despite the fact that to a relative Frame of Reference user such as myself, the house would be behind the police office. With the house reference system, everything is seen from the perspective of that house not from the perspective of the two people in conversation.

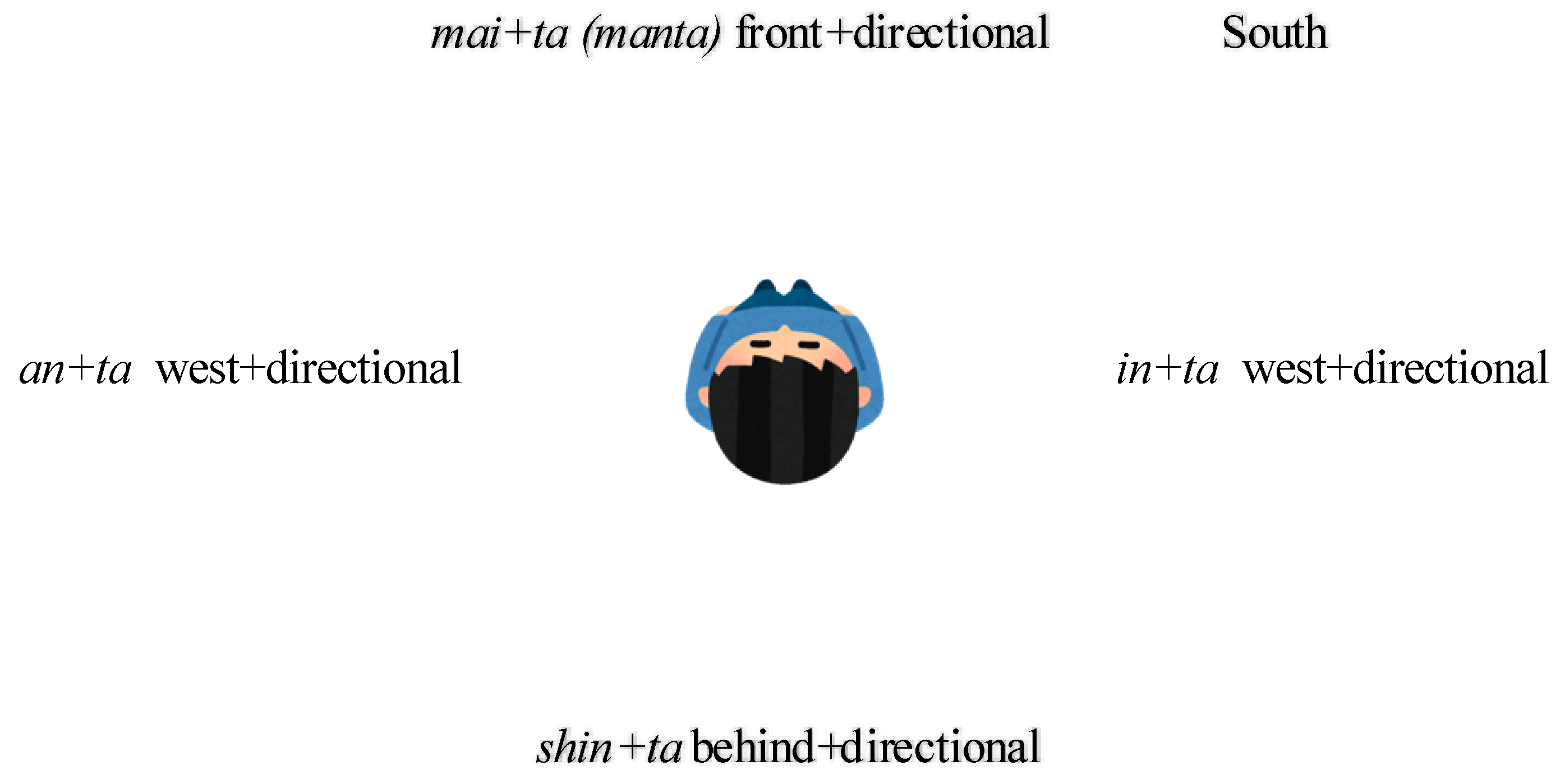

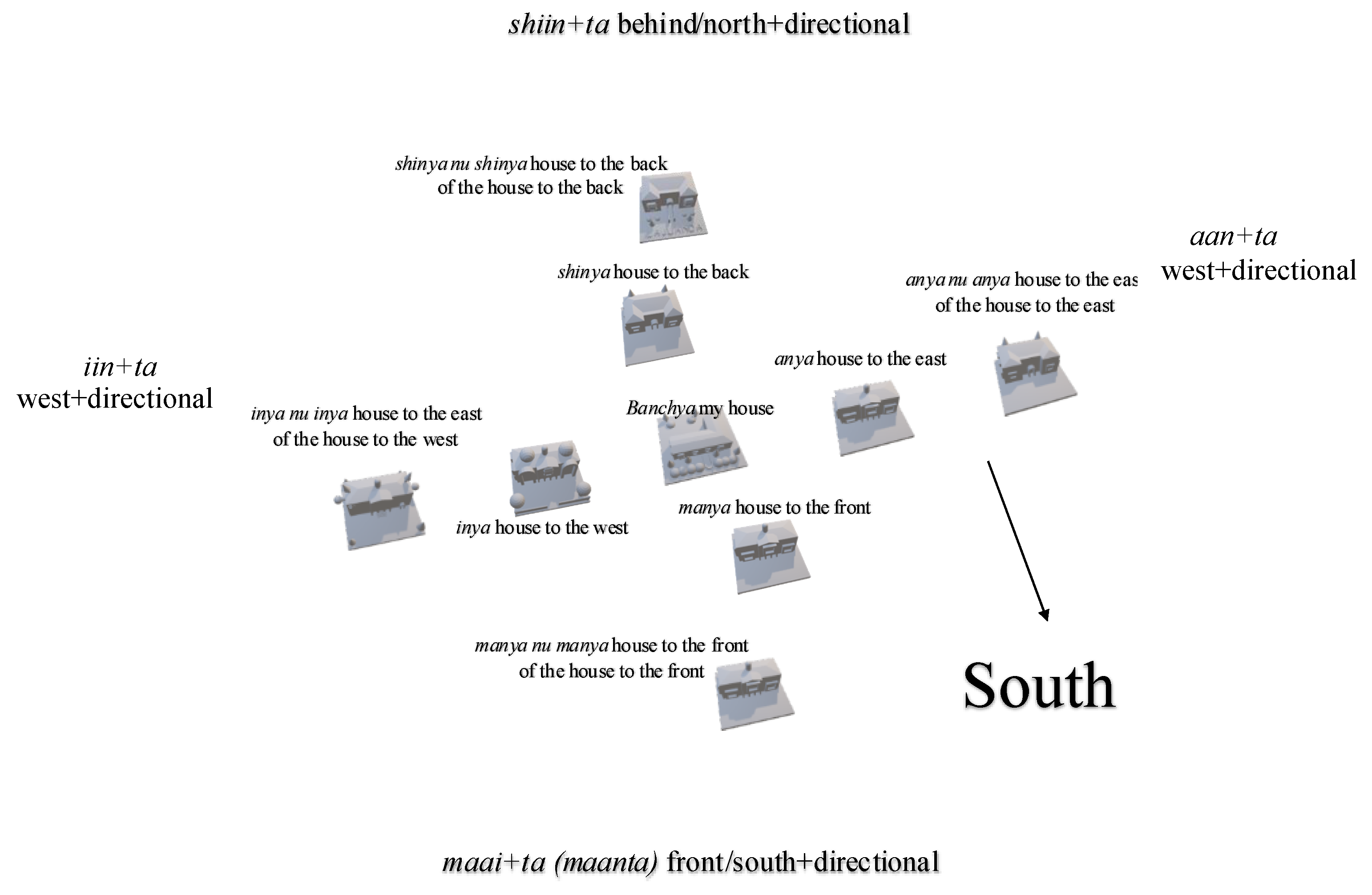

5.4. The House System Outside of the Neighborhood

For talking about places outside of two sets of surrounding houses, the system replaces the

ya ‘house’ with the directional ‘-

ta’ (

Figure 9). Locations would be referred based on the location of the south facing home of the speaker. While the terms are for describing location from the home, they tend to replace the cardinal directions in usage. When asked to translate them into Japanese, C translated them as

inta ‘towards the west’

anta ‘towards the east’

shinta ‘towards the north’, and

manta ‘towards the south. When asked why house-based terms were used instead of cardinal terms, the answers were generally along the lines that one could use cardinal terms. Additional interviews of more proficient full speakers are needed to further explore this, but the profound and pervasive nature of the house system is an ostensible cause. When B was asked for directions to the city hall he replied, “

yakuba=kai=ya=yoo uma=kara massugu aanta=kai par-u-kkaa yakuba atarir-u.” “To the city hall yeah? From where you are, if you head straight in the

aanta direction you will reach the city hall.”

Cardinal directions tend to be reserved for when the location is at some great distance. Z explained, “For where the sun rises you would use the regular direction words iru ‘west’ and aru ‘east’.” B explained that for things far away kamaara, a cardinal directional was used. Although this is not corroborated by the dictionary, which does not list the words with a longer first vowel sound or explain that there is an alternate meaning, all those I interviewed claimed that the first vowel was long in use outside of the home. Rusty Shikāza speaker E explained, “anta is when it is close aanta is when giving directions.” To which B added, “kaamaru aru ‘far off to the east’ when it is really far.” As to the distance where the line is drawn, it appears to be based on walking distances. E explained “I think kaamara is used for places that were far before there were cars. Now what we might have used kaamara for can be reached in just five minutes or so by car.”

Finally, similarly to the inside home system, the terms for

manta ‘front’ and

shinta ‘back’ can be used based on the direction the speaker or listener is facing and ignoring the standard compass based on the house facing south. In this case,

manta would shift from meaning in a south of the house direction to meaning just ahead in the direction you are facing. Full Shikāza speaker B explains with the example:

| manta=nu | maaru=kai | haru-kkaa | machiya | ar-u. |

| Front.dir-GEN area=ALL | walk-CND1 shops | have-NPST | | |

| ‘If (you) head in the direction ahead (of you), there are shops. |

| takaa=ni | ari=du | ur-u |

| lots=ADVR | have=FOC | be-NPST |

| There are many (of them).’ |

They then offer the explanation for when one can use it based on personal perspective or house object perspective:

Well, if you are walking… (pause) hmm, normally… what is the standard is that you are sitting down. Then

manta is always to the south. But if you are walking and you wanted to say, ‘oh, if you just keep walking a bit more straight ahead’

mai nu maita ‘the

maita in front of you’. So normally it would be based on where you are sitting (facing south).

Inta haa, shinta haa, anta haa, inta haa10. But when you are walking you can use

manta for the direction you are heading.

As in the indoor system, the general rule is that you are sitting down/facing south, but especially manta ‘front’ and shinta ‘back’ can be used based on the person’s perspective. Additionally similar, as with the example above, is that the manta/shinta of the addressee is just as often used as the manta/shinta of the speaker. They were facing me but gesturing in the direction in front of me, my manta when giving the above example to the question if there were any shops around here.

5.5. Full and Rusty Shikāza Speaker Ability to Use the House Based Directional System

A had talked about the system more in the March interviews but focused on the fact that no one uses it anymore because almost no one understands it.

“Yeah, we used to use those expressions, but we have taxi drivers from all over Japan, plus we have people from other islands and tourists here who won’t understand them. They don’t even know what direction south is so even though it would be natural for me to say ‘turn south’ in Japanese, they don’t understand. Also, a lot of Taxi drivers are confused by local people. We have been told since Okinawa was returned back to Japan in 1972 to not use those expressions, so I just use right and left and everyone understands. I could still use them with people from the island but now I only use them in the rare case that a driver is from the island.” (She is no longer able to walk outside of her home.)

This level of accommodating people not familiar with the spatial reference system of Yaeyaman emerges here as a main expedient of its disuse. This was the same case with Rusty speaker C, who explained that giving directions is not something that happens that often and it is a situation when explaining clearly is important. Even though she has become quite concerned over the years of the loss of the language and has become determined to use Yaeyaman as often as possible, she was still hesitant to use this system with anyone other than her mother:

“Taxi drivers wouldn’t understand at all (laughing). Yeah, there are lots of people out there and we don’t always know who might understand our language so If I try and give directions in sumamuni I am probably just making things more complicated.”

A week after the interview, C got back to me with some examples that she had started to notice her mother using of the home-based reference system outside of the home. She said she had never picked up on her mother using the expressions beyond the -

ya ending house system in the interview. One example she had noticed in the week after the interview:

| maita=nu | machiya=kara | nuuru=Ø | kai+kii+hyuu-nu |

| front.dir=GEN | store=ABL | seaweed=ACC | buy+come+receive-NEG.Q |

| ‘(Could you) go and buy (some) seaweed from (the) store to our maita ‘the south/front of our house’?’ |

Rusty speaker D has also gained a lot of fluency in Yaeyaman but did not tend to use the expressions at all. When asked, he said “You can use them (house-based reference expressions) with people from the island, but we also have words for left and right too, so I just use those. I think most people just use those.” Finally, when I asked D about the loss of this system he mentioned, as A had previously, that taxi drivers were really confused by people using the system and an island-wide campaign had been made to encourage people not to use the system.

F said that the only people he used Yaeyaman with were his parents and relatives. Although he was familiar with and could use the -

ya endings at neighborhood level, he did not have anyone to use the expressions with outside of his family. He said his main reason for rarely using the language was that he did not learn the appropriate way to speak to an elder/superior so he would be chastised. Speaking Japanese was safer in that respect. Even though he could communicate with his parents, he had avoided doing so in Yaeyaman. F is an Okinawan-Yaeyaman contact variety speaker. When asked if he can use the expressions:

“I don’t use it naturally, but my family members who have older family members do occasionally use it, but only when the person they are talking to is old enough. They don’t seem to use it when talking to younger people.”

No one really knew what to say when I asked the rusty speakers about the loss of this system. All of my consultants are increasingly active in using and promoting Yaeyaman, and everyone I spoke to also agreed wholeheartedly that losing the language would be terrible, but the loss of nonconformist concepts such as their orientation system was not something they had thought about in this context.

B was a monolingual Yaeyaman speaker until age seven and has spent most of his life as a farmer. He was able to use the entire system naturally and explain the finer details of how the system worked. When asked about the inability of younger generations to use the orientation system and other nonconformist concepts and their loss, he replied, “Well, you know, sumamuni is naturally going to go away. Disappear.”

We see in the loss of the indigenous orientation system that language endangerment is not simply a disuse of the language, but also a simplification of the language and the concepts it implies. Let us explore this further with one more example, that of reference for seasons in Yaeyaman.

6. The Yaeyaman Seasons

There are five seasons specific to Yaeyama:

fuyu winter-mid-November〜February

urizin early spring-March〜April

baganaci young summer-May〜June

naci summer-July〜mid-September

sisanaci white summer-mid-September〜mid-November

This is in contrast with Japan, which has a long tradition of celebrating nature divided into four distinct seasons, though there is a fifth season called tsuyu ‘rainy season’. In fact, Japanese people are quite proud of their climate. One will often overhear the odd phrase, ‘I like Japan because it has four seasons.’ These four seasons have a long tradition of being split into early middle and late periods and eulogized in haiku with kigo ‘season words.’ It is this concept of four distinct seasons plus a rainy season that has been pressed into the psyche of the Yaeyaman people through school education and Tokyo media even though they have traditional words for their own seasons naturally tailored to their environment.

Of all of the Shikāza speakers interviewed, only the full speakers could name the five seasons in Yaeyaman. Two rusty speakers with high fluency were able to name most of them but were not able to give immediate answers. D was able to remember most of them because he had been asked how to say the rainy season in Yaeyaman in the weekly Zoom class he teaches. Both D and C were both clearly aware of the fact that there is no rainy season in Ishigaki, but he had to look up the words for the five seasons to make sure he had remembered them correctly, and often uses the Japanese term tsuyu in that classes’ social media discussions.

When asked how many seasons there are in Yaeyaman, C replied:

“How many? Hmmm, I wonder. Well, there is summer and winter but there aren’t words for fall and spring I think. urizin or pisanatsu. Seasons slightly different than summer and seasons slightly different than winter exist but I don’t think there is an expression for spring. You should ask (A)”

When asked why she thinks she and many other speakers cannot remember or use the weather terms, she told me the following:

“Well for the weather, it is because Japan’s weather terms have been brought here. And we all speak hyōjungo ‘standard language (Japanese)’. From weather forecasts for example, we don’t have tsuyu, but people still use it here. Things like that, we get the weather forecasts from the population center (Tokyo) and so that becomes our main news.”

“…if you turn on the TV NHK’s broadcast, it is the same one direct from Tokyo. And the program always begins with Tokyo. So those places become the main subject of the news. The biggest example that happens the most frequently is with typhoons. If there is a typhoon here but it isn’t approaching Tokyo, then we won’t even be mentioned. Not unless it is a massive high-level typhoon, they won’t tell us about it. Nowadays we can look at the weather forecast and see them (typhoons) coming on global radar, but before we would have no idea that a typhoon was coming when we watched the weather forecasts.”

NHK is the national television station of Japan. It is the first TV channel that was broadcast to Ishigaki in Japanese, and it has had a large influence on the population. D said NHK was formative in his opinions of Yaeyaman (referred to as dialect in the comment below) and Japanese:

“Yeah, I was raised to think and always had in my head until recently that speaking in dialect (Yaeyaman) was wrong/bad. And that Japanese was beautiful. Everything on the TV was in standard language (Japanese) so I felt I had to learn to speak like that. Yeah, the impact (from Japanese TV) was very big on me. The Japanese on the TV and radio was very beautiful, so I was raised to think that that was the appropriate way to speak.”

C asked if she thought mainstream Japanese media was part of the causing the loss of Yaeyaman nonconformist concepts:

“I think that is what is happening. I mean, in our minyo ‘folk songs’, urizin or other expressions for the seasons and other things from sumamuni way of thinking are still there but in modern weather terms we just don’t use them.”

Conversations such as these with Yaeyaman rusty and full speakers confirm

Brenzinger’s (

2006,

2007) observation that the mass media is a prime means of spreading conformist modern concepts. Asked if C’s mother (a full speaker) uses the season expressions:

“We don’t use them; she doesn’t say them. Now in the past when they did farming, they would have terms for when to plant seeds or harvest that went with the weather, but now that my mother is old, and she doesn’t farm, of course, so the time when she would use those words doesn’t occur anymore so she would not think to express those ideas, so I don’t hear them.”

According to A, there are three seasons in Yaeyama with

baganaci and

sisanaci the terms for the beginning and end periods of summer. Fall is the season that Ishigaki does not have, which was an inner struggle for her has a haiku author

“Even though we don’t have fall, I really have to use the fall kigo terms to write haiku (laughing). (Pause) Well there is no rule that says I have to use them, but one is supposed to organize a whole year’s worth of seasonal poems when completing a book of haiku. I find it very difficult to organize a whole book without using the kigo terms for fall. For example, even though it is swelteringly hot here, because obon [Bon Festival] is technically a fall kigo I wrote a poem in the fall section about obon that doesn’t have anything to do with the fall season.”

She then noted how she feels about having to go out of her way to manufacture fall poems:

“Yes, because there is never a feeling of fall here, I just do things like go out of my way to find chestnuts and make chestnut rice so I can write a poem with fall kigo. I guess it is OK (laughing).”

Conformism is strong, so strong that some go on to create sentiments and expressions that do not exist. All the while, the terminology and the concepts that capture the environment are lost. Looking at Yaeyman through standard Japanese eyes make it look poor, as in the sense that there is, for example, no fall season and thus, that one cannot write a complete book of haikus in a Yaeyaman setting. A shift in perspective, that is, a shift towards the unique concepts and terminology that very precisely capture the environment and the life in Yaeyama challenges such views. Yaeyaman appears to no longer be confusing or old, but precise and rooted in the immediate present.

7. Conclusions

This paper has shown that while ostensibly collecting descriptive data on unique Yaeyaman concepts, the participants’ responses rationalize why speakers in the past (and the present) accommodated non-speakers by using Japanese. They know that mainland Japanese or monolingual Yaeyamans and Okinawans are unable to understand non-conformist systems, and thus they do not venture to use them and are now even unsure how the systems work themselves. The full speakers are aware that losing the language would serve as a great loss, but they are still unsure how to maintain their languages, and what to maintain thereof. Decolonization is a process, and a difficult one at that. Among the middle and young generations, a resurgence has taken place and many of them engage to save their heritage language. They seek to build their own fluency by speaking sumamuni with their parents before it is too late. All the while, their focus often does not include the concepts of their ancestors. The nonconformist concepts patent to the language are at the heart of what it is to think similarly to them, and to see the world from a Yaeyaman perspective; however, it is these perspectives that appear to be too undervalued. While a decolonization of the mind in the Yaeyamans has begun, fully appreciating a non-Japanese world view remains a task that is out if sight to many at the present. However, saving a language but with the concepts of the replacing language (Japanese), continues to reproduce the idea that the replacing language is (conceptually) superior to the heritage language. It bears traces of the colonist ideology.

While Japanese policies can be blamed for much of the state of Ryukyuan languages, the low status of these languages in the minds of their people acquired through colonization remains one of the greatest barriers to the populations ability to organize a means to reverse the shift to Japanese. A further obstacle, albeit not fully addressed in this paper, is that the accommodation of monolingual Japanese speakers is so unconsciously entrenched in the minds of the full and rusty speakers, that they see only such linguistic behavior as pragmatically acceptable. The rusty speakers have never suffered from the negative consequences from such accommodation that occur in other settings globally. On the contrary, the modern Yaeyaman rusty or semi speakers interviewed for this paper appear completely consumed with concerns of not appropriately accommodating to monolingual Japanese speakers. This illustrates how deeply the colonization of their minds has taken place as their behaviors are entirely natural considering the circumstances of their experience. A further factor may be the inclusive nature of the Yaeyaman people (

Kerr 2018), but such communicative behavior has resulted in the abandonment of their unique cognitive concepts.

This article argues that by highlighting expressions that convey a unique Yaeyaman world view, people can hold their heritage tradition in a higher esteem and begin to feel more pride in their heritage identity. However, in addition to embracing this conceptual heritage knowledge, undoing the present accommodation behavior is a fundamental part of the decolonization process for Yaeyama and its people. By using their concepts along with Yaeyaman when speaking in public and creating charts and other explanatory materials for Japanese speakers to understand, new, semi, and rusty speakers could make a significant step towards decolonization while also preserving the heritage knowledge of what could be lost in translation into a language such as Japanese, which is full of modern concepts. Practices such as initially greeting in Yaeyaman everyone one meets and without apology may also contribute to the solution. Alternatively, while perhaps impossible for many graduate students struggling to complete PhDs and find ways to obtain gainful employment, descriptive linguists could potentially do more to focus on these nonconformist concepts both by focusing more research on them and by relying less on translation for their analysis when possible.