Fortune and Decay of Lexical Expletives in Germanic and Romance along the Adige River

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Typology of Lexical Expletives in Cimbrian

- (i)

- ′z/-z, which corresponds to German es (English it);

- (ii)

- -da, which approximately corresponds to English there.

2.1. Expletives Required by the Negative Value of the NSP

2.1.1. The Expletive ′z/-z

| (1) | a. | ′Z | snaibet | haüt | atz | Lusérn. |

| it | snows | today | at | Luserna | ||

| b. | Haüt | snaibet=z | atz | Lusérn. | ||

| today | snows=it.cl | at | Luserna | |||

| ‘It is snowing today in Luserna.’ | ||||||

| (2) | a. | Es | schneit | heute | in | Lusérn. |

| it | snows | today | at | Luserna | ||

| b. | Heute | schneit | es | in | Lusérn. | |

| today | snows | it | at | Luserna | ||

| ‘It is snowing today in Luserna.’ | ||||||

| (3) | a. | Bal=z | snaibet | starch | atz Lusérn, | stea=bar | dahuam. | ||

| when=it.cl | snows | hard | at | Luserna, | stay=we.cl | at=home | |||

| ‘When it snows heavily in Luserna, we stay home.’ | |||||||||

| b. | I sperar, | az=(z)6 | snaibe | starch | haüt | atz Lusérn. | |||

| I hope | that=it.cl | snow.conj | hard | today | at | Luserna | |||

| ‘I hope that it will snow heavily today in Luserna.’ | |||||||||

| c. | I vors=mar, | be=z | snaibet | starch | haüt | atz Lusérn. | |||

| I ask=me.dat.cl | if=it.cl | snows | hard | today | at | Luserna | |||

| ‘I’m wondering if it is snowing heavily today in Luserna.’ | |||||||||

| (4) | a. | Wenn es | in | Lusérn | stark | schneit, | bleiben wir | zu Hause. | |||

| when=it.cl | in | Luserna | hard | snows, | remain we | at | home | ||||

| ‘When it snows heavily in Luserna, we remain home.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | Ich | hoffe, dass | es | heute | in Lusern | stark | schneit. | ||||

| I | hope | that | it | today | in Luserna | hard | snows | ||||

| ‘I hope that it will snow heavily today in Luserna.’ | |||||||||||

| c. | Ich | frage | mich, ob | es | heute | in Lusern | stark | schneit. | |||

| I | ask | me | if | it | today | in Luserna | hard | snows | |||

| ‘I’m wondering if it is snowing heavily today in Luserna.’ | |||||||||||

| (5) | a. | Snaibet=z | haüt | atz Lusérn? | |

| Snows=it.cl | today | at | Luserna | ||

| ‘Is it snowing at Lusern today?’ | |||||

| b. | Bo | snaibet=z | haüt? | ||

| where | snows=it.cl | today | |||

| ‘Where is it snowing today?’ | |||||

| (6) | a. | Schneit | es | heute | in Lusérn? | |

| Snows | it | today | in | Luserna | ||

| ‘Is it snowing in Lusern today?’ | ||||||

| b. | Wo | schneit | es | heute? | ||

| where | snows | it | today | |||

| ‘Where is it snowing today?’ | ||||||

| (7) | a. | ‘Z | hatt=en | gevallt, | [az=ta | dar Luca | sai(be) | khent | afn | vairta] |

| it | has=him.cl | pleased | that=da | the Luca | is.conj | come | to=the | party | ||

| ‘He was pleased that Luca came to the party.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Gestarn | hatt=z=en | gevallt, | [az=ta | dar Luca | sai(be) | khent | afn | vairta] | |

| Yesterday | has=it=him.cl | pleased | that=da | the Luca | is.conj | come | to=the | party | ||

| ‘Yesterday, he was pleased that Luca came to the party.’ | ||||||||||

| c. | Hatt=z=en | gevallt | gestarn, | [az=ta | dar Luca | sai(be) | khent | afn | vairta]? | |

| has=it=him.cl | pleased | yesterday | that=da | the Luca | is.conj | come | to=the | party | ||

| ‘Yesterday, did he like yesterday that Luca came to the party?’ | ||||||||||

| (8) | a. | Es | hat | Hans | gefallen, | [dass | Lukas | zum | Fest | gekommen | ist] | ||

| it | has | Hans | pleased | that | Lukas | to=the | party | come | is | ||||

| ‘Hans was pleased that Lukas came to the party.’ | |||||||||||||

| b. | Gestern | hat | (es) | Hans | gefallen, | [dass | Lukas | zum | Fest | gekommen | ist] | ||

| yesterday | has | it | Hans | pleased | that | Lukas | to=the | party | come | is | |||

| ‘Yesterday, Hans was pleased that Lukas came to the party.’ | |||||||||||||

| c. | Hat | (es) | Hans | gestern | gefallen, | [dass | Lukas | zum | Fest | gekommen | ist]? | ||

| Has | it | Hans | yesterday | pleased | that | Lukas | to=the | party | come | is | |||

| ‘Was Hans pleased yesterday that Lukas came to the party?’ | |||||||||||||

| (9) | [Az=ta | dar Luca | sai(be) | khent | afn | vairta], | hatt=(*z)=eni | gevallt | in | Hånsi. |

| that=da | the Luca | is | come | to=the | party | has=(it)=him.cl | pleased | the.dat | John | |

| ‘That Luke came to the party pleased Hans.’ | ||||||||||

| (10) | [Dass | Lukas | zum | Fest | gekommen | ist], | hat | (*es) | Hans | gefallen. |

| that | Lukas | to=the | party | come | is | has | (it) | Hans | pleased | |

| ‘That Luke came to the party pleased Hans.’ | ||||||||||

2.1.2. The Expletive -da

| (11) | a. | Moi nono | iz | khent | atz Lusérn | haüt. | |||

| my grandpa | is | come | to Luserna | today | |||||

| ‘My grandpa came to Luserna today.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Haüt | iz=ta | khent | atz Lusérn | moi nono. | ||||

| today | is=da | come | to Luserna | my grandpa | |||||

| ‘Today, my grandpa came to Luserna.’ | |||||||||

| c. | I sperar, | az=ta | sai(be) | khent | atz Lusérn | moi nono | haüt. | ||

| I hope, | that=da | is | come | in Luserna | my grandpa | today | |||

| ‘I hope that my grandpa came to Luserna today.’ | |||||||||

| d. | Iz=ta | khent | atz Lusérn | moi nono | haüt? | ||||

| Is=da | come | in Luserna | my grandpa | today | |||||

| ‘Did my grandpa come to Luserna today?’ | |||||||||

| (12) | a. | Mein Großvater | ist | (*es) | heute | nach Lusérn | gekommen. | |||

| my grandpa | is | (it) | today | to Luserna | come | |||||

| ‘My grandpa came to Luserna today.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Heute | ist | (*es) | nach | Lusérn | mein Großvater | gekommen. | |||

| today | is | (it) | to | Luserna | my grandpa | come | ||||

| ‘Today, my grandpa came to Luserna.’ | ||||||||||

| c. | Ich hoffe, | dass | (*es) | heute | nach | Lusérn | mein Großvater | gekommen | ist. | |

| I hope, | that | (it) | today | to | Luserna | my grandpa | come | is | ||

| ‘I hope that my grandpa came to Luserna today.’ | ||||||||||

| d. | Ist | (*es) | heute | nach | Lusérn | mein Großvater | gekommen? | |||

| is | (it) | today | to | Luserna | my grandpa | come | ||||

| ‘Did my grandpa come to Luserna today?’ | ||||||||||

| (13) | a. | There arrives a man. |

| b. | I know that there lived a lonely old man in the forest. |

| (14) | a. | *There arrives Mary today | (definiteness effect) | |

| b. | okHaüt | khint=(t)a | di Maria. | |

| today | comes=da | the Mary | ||

| ‘Mary is arriving today.’ | ||||

| (15) | a. | *There has read a book my mother/my mother a book | (transitive verbs) | |||

| b. | okHaüt | hatt=(t)a | gelest | an libar | moi mamma | |

| today | has=da | read | a book | my mother | ||

| ‘Today, my mother has read a book.’ | ||||||

| (16) |  |

2.2. V2 Expletives

| (17) | a. | Haüt | in | balt | hatt=ar | gesek | in | has. |

| today | in=the | wood | has=he.cl | seen | the.acc | rabbit | ||

| ‘Today, he saw the rabbit in the wood.’ | ||||||||

| b. | [CP [Haüt] [in balt] [FinP hatt=ar …. [VP gesek [dp in has]]]] | |||||||

| (18) | a. | Hatt=ar | gesek | in | has | haüt | in | balt? | |

| has=he.cl | seen | the.acc rabbit | today | in=the | wood | ||||

| ‘Did he see the rabbit in the wood today?’ | |||||||||

| b. | Hat | er | heute | im Wald | den Hasen | gesehen? | |||

| has=he.cl | today | in=the wood | the.acc rabbit | seen | |||||

| ‘Did he see the rabbit in the wood today?’ | |||||||||

| (19) | a. | ‘Z | hatt=(t)a | gesek | in | has | dar djunge | in | balt | haüt. |

| it | has=da | seen | the.acc rabbit | the boy | in=the | wood | heute | |||

| ‘Today, the boy saw the rabbit in the wood.’ | ||||||||||

| a. | Es | hat | der Junge | heute | im Wald | den Hasen | gesehen. | |||

| it | has | the boy | today | in=the | the.acc rabbit | seen | ||||

| ‘Today, the boy saw the rabbit in the wood.’ | ||||||||||

- (i)

- The morphological realization: it only occurs on the left of the finite verb (i.e., it refuses enclisis);

- (ii)

- The co-occurrence with enclitic -da: since ’z implies a postverbal (i.e., not raised subject), the enclitic particle -da is always required (cf. 20):

(20) ‘Z laütan=da di klokkn. it ring.pl=da the bells ‘The bells are ringing.’

| (21) | a. | Da | laütan=da | di klokkn. | ||||

| there | ring.pl=da | the bells | ||||||

| ‘There the bells are ringing.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Da | hatt=(d)a | gesek | in | has | dar | djunge. | |

| there | has=da | seen | the.acc hare | the.nom | boy | |||

| ‘There the boy saw the hare.’ | ||||||||

| (22) | a. | Da | laütan=sa. | |||||

| there | ring.pl=they.cl | |||||||

| ‘There they are ringing.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Da | hatt=ar | gesek | in has | haüt | in | balt. | |

| there | has=he.cl | seen | the.acc hare | today | in-the | wood | ||

| ‘There he saw the hare in the wood today.’ | ||||||||

| (23) | a. | *Es | ist | er | angekommen. | |

| it | is | he | arrived | |||

| b. | Es | ist | (auch) ER/DER | gekommen. | ||

| it | is | also | he | arrived | ||

| ‘He also arrived.’ | ||||||

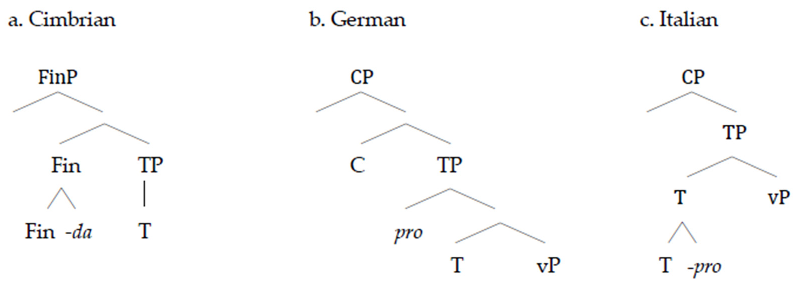

2.3. First Summary

3. The Typology of Lexical Expletives in the Trentino Dialects

| (25) | a. | El | piòve. | (Casalicchio and Cordin 2020, p. 109) | |||

| it | rains | ||||||

| ‘It’s raining.’ | |||||||

| b. | L’a | nevegà | tuta | la | nòt. | ||

| it.cl-has | snowed | all | the | night | |||

| ‘It snowed all night.’ | |||||||

| (26) | È | nevicato. |

| is | snowed | |

| ‘It snowed.’ | ||

| (27) | a. | L’a | fiocà. | (Lavis, S0136_tre_U0409)10 |

| it.cl-has | snowed | |||

| ‘It snowed.’ | ||||

| b. | L’è | nevegà. | (Cinte Tesino, S0136_tre_U0411) | |

| it.cl-is | snowed | |||

| ‘It snowed.’ | ||||

| c. | L’a | nevegà. | (Trento, S0136_tre_U0451) | |

| it.cl-has | snowed | |||

| ‘It snowed.’ | ||||

| (28) | a. | È | nevegà. | (Levico, S0136_tre_U0565) |

| is | snowed | |||

| ‘It snowed.’ | ||||

| b. | A | fiocà. | (Mori, S0136_tre_U0469) | |

| has | snowed | |||

| ‘It snowed.’ | ||||

- (i)

- Inflected verbs in the third person singular always involve a clitic that doubles the argumental preverbal subject even when the last one was not left-dislocated (cf. 29) (see Brandi and Cordin 1989 and Casalicchio and Cordin 2020, p. 110: “Subject clitics must also be expressed when the preverbal subject is a noun phrase, or a pronoun”):13

(29) a. La maestra de matematica la va via. the teacher of math she goes away ‘The math teacher is going away.’ b. *La maestra de matematica va via. the teacher of math goes away c. La maestra de matematica l’ è nada via. the teacher of math she is gone away ‘The math teacher went away.’ d. *La maestra de matematica è nada via. the teacher of math is gone away - (ii)

- As already noted by Brandi and Cordin (1989) and confirmed by Casalicchio and Cordin (2020, pp. 111, 261), clitic reduplication is excluded in three contexts: (a) when the subject occurs in the postverbal position without being right-dislocated (cf. 30) (see also Poletto 1993); (b) in both restrictive relative clauses (cf. 31) and wh-interrogatives on the subject (cf. 32); and (c) with the negative quantifier nissun/nessun/nissuni/nessuni ‘nobody’ (cf. 33).14

| (30) | a. | Va | via | la maestra | de matematica. | |

| goes | away | the teacher | of math | |||

| ‘The math teacher is going away.’ | ||||||

| b. | È | nà | via | la maestra | de matematica. | |

| is | gone | away | the teacher | of math | ||

| ‘The math teacher went away.’ | ||||||

| (31) | Le putele | che | (*le) | ha | parlà | con ti … | (Brandi and Cordin 1989, p. 126) |

| the girls | that | they.cl | have | talked | with you | ||

| ‘The girls who talked to you …’ | |||||||

| (32) | Quante | putèle | (*le) | ha | parlà | con ti? | (Brandi and Cordin 1989, p. 125) |

| how-many | girls | they.cl | have | talked | with you | ||

| ‘How many girls talked to you?’ | |||||||

| (33) | Nesun | (*l’) | è | vegnù | en | tèmp. | (adapted from Casalicchio and Cordin 2020, p. 111) |

| nobody | he.cl | is | come | in | time | ||

| ‘Nobody was on time.’ | |||||||

- (a)

- Postverbal [-hum] subjects in declarative sentences do not to realize the clitic (36 cases versus 8 in VinKo) (cf. 34) (data taken from Kruijt et al., n.d.):

(34) È scominzià la scola. (Brentonico, S0134_tre_U0049) is started the school ‘School has started.’ - (b)

- Postverbal [+hum] subjects in indirect interrogative sentences almost always require a clitic (18 cases vs. 1):

(35) Non so miga ndo che=’l sia nà el Marco. (Brentonico, S0115_tre_U0088) Not know not where that=he.cl is.conj gone the Mark ‘I don’t know where Mark has gone.’s

| (36) | a. | L’è | bela | to sorela. | |||

| she.cl-is | nice | your sister | |||||

| ‘Your sister is nice.’ | |||||||

| b. | I | è | za | grandi | i | pòpi. | |

| they.cl | are | already | grown-up | the children | |||

| ‘The children are already grown up.’ | |||||||

4. The Typology of Lexical Expletives in the Dialects Spoken in Veneto

- (a)

- Examples with the clitic and both auxiliary verbs a ‘has’ and è ‘is’:

(37) a. L’a nevegà. (Verona, S0136_vec_U0420) it.cl-has snowed ‘It snowed.’ b. L’è nevegà. (Verona, S0136_vec_U0439) it.cl-is snowed (38) A ga nevegà. (Bonavigo, S0136_vec_U0450) prt has snowed - (b)

- Examples without the clitic:

(39) a. A nevegà. (Verona, S0136_vec_U0403) has snowed ‘It snowed.’ b. È nevegà. (Sona, S0136_vec_U0402) is snowed c. Ghe nevegà. (Bonavigo, S0136_vec_U0408) has snowed d. Ga nevegà. (Legnago, S0136_vec_U0300) has snowed

| (40) | (E)l ga | nevegà. | (Schio, S0136_vec_U0320) |

| it.cl-has | snowed | ||

| ‘It snowed.’ | |||

| (41) | Ga | nevegà. | (Recoaro, S0136_vec_U0306) |

| has | snowed | ||

| ‘It snowed.’ | |||

| (42) | Ga | nevegà. | (Cittadella, S0136_vec_U0326) |

| has | snowed | ||

| ‘It snowed.’ | |||

| (43) | Ga | nevegà. | (Castelfranco, S0136_vec_U0302) |

| has | snowed | ||

| ‘It snowed.’ | |||

| (44) | L’è | nevegà | (ma no tant). | (Codognè, S0136_vec_U0647) |

| it.cl-is | snowed | (but not too much) | ||

| ‘It snowed (but not too much).’ | ||||

| (45) | Ga | nevegà | (Venezia, S0136_vec_U0454) |

| has | snowed | ||

| ‘It snowed.’ | |||

| (46) | L’è | nevegà | (San Donà, S0136_vec_U0651) |

| it.cl-is | snowed | ||

| ‘It snowed.’ | |||

- (a)

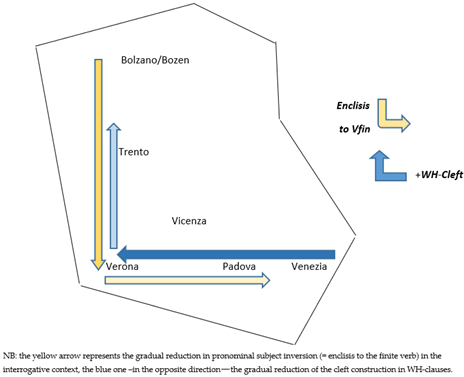

- The maintenance of lexical expletives in the dialects spoken in Trentino is definitely more robust in comparison with the Venetian region with respect to both impersonal subject clitics and the possible co-occurrence with a postverbal subject;

- (b)

- The maintenance of lexical expletives in Veneto exhibits a clear decrease from the southwestern area (the province of Verona) toward the southeastern provinces of Vicenza, Padova, and Venice.22

Second Summary

5. Linguistic Borders and the Potential Role of Language Contact

| (48) | a. | A=lo | nevegà? |

| has=it.cl | snowed | ||

| ‘Did it snow?’ | |||

| b. | È=lo | nevegà? | |

| is=it.cl | snowed | ||

| (49) | È=loi | rivà | to | nonoi? |

| is=he.cl | arrived | your | grandpa | |

| ‘Did your grandpa arrive?’ | ||||

| (50) | a. | Cosa | fa=lo? | |

| what | does=he.cl | |||

| ‘What is he doing?’ | ||||

| b. | Cosa | a=lo | combinà? | |

| what | has=he.cl | done | ||

| ‘What did he do?’ | ||||

| c. | ‘Ndo | va=lo? | ||

| where | goes=he.cl | |||

| ‘Where is he going?’ | ||||

| (51) | a. | L’a | magnà | su | tut? | |

| he.cl-has | eaten | prt | all | |||

| ‘He ate it all, didn’t he?’ | ||||||

| b. | L’a | nevegà | anc’ancò? | |||

| it.cl-has | snowed | also-today | ||||

| ‘It snowed today too, didn’t it?’ | ||||||

| c. | L’i è | rivà | anca | to | nonoi? | |

| he.cl-is | arrived | also | your | grandpa | ||

| ‘Your grandfather arrived too, didn’t he?’ | ||||||

| (52) | a. | Cos’è=(l/lo) | che’l | fa?28 | (Casalicchio and Cordin 2020, p. 120) | ||

| what-is=it.cl | that-he.cl | does | |||||

| ‘What is he doing?’ | |||||||

| b. | End’è=l | che | l’a | metü | la | bórsa? | |

| Where-is=it.cl | that | have.2ps | put | the | bag | ||

| ‘Where did you put the bag?’ | (adapted from Casalicchio and Cordin 2020, p. 320) | ||||||

- Whenever the expletive subject does not occur in the declarative sentence, it does not appear in the interrogative context either in enclisis (cf. 53a-b) or in the much more common cleft construction (cf. 54):

(53) a. Ga nevegà? (Cittadella, Padova) has snowed ‘Did it snow?’ b. Dove ga nevegà uncò? where has snowed today ‘Where did it snow today?’ (54) Dove xe che ga nevegà uncò? (Cittadella, Padova) where is that has snowed today ‘Where did it snow today?’ - Enclisis appears regularly in polarity questions (cf. 55):

(55) a. Va=lo via? (Verona) goes-he.cl away ‘Is he leaving?’ a.’ Va=eo via? (Cittadella, Padova) goes-he.cl away b. È=lo na via? (Verona) is-he.cl gone away ‘Did he leave?’ b.’ Z=eo onda(to) via? (Cittadella, Padova) is-he.cl gone away c. A=lo magnà tuto? (Verona) has=he.cl eaten all ‘Did he eat it all?’ c.’ Ga=eo magnà tutto? (Cittadella, Padova) has=he.cl eaten all

| (56) | a. | El | va via? | Sul serio? | (Cittadella) | ||

| he.cl | goes away. | Seriously | |||||

| ‘He is leaving. Seriously?’ | |||||||

| b. | L’è | ndà | via? | Sul serio? | (Cittadella) | ||

| he.cl-is | gone | away. | Seriously | ||||

| ‘He left. Seriously?’ | |||||||

| c. | L’à | magnà | tuto | anca | uncò? | (Cittadella) | |

| he.cl-has | eaten | all | also | today | |||

| ‘Did he eat it all today as well?’ | |||||||

- III.

- In WH-questions, enclisis is maintained (cf. 57), but there is a strong preference for the cleft construction whose attestation definitely increases from southwest (Verona) moving eastward (Padua) and represents the only option in Venice:

(57) a. Ndo va=lo? (Verona) where goes=he.cl ‘Where is he going?’ a.’ Dove xè che el va? / Dove va=eo? (Cittadella, Padova) where is that he.cl goes / Where goes=he.cl b. Cos’a=lo magnà? (Verona) what-has he.cl eaten ‘What did he eat?’ b.´ Cosa zè che el ga magnà? / Cosa ga=eo magnà? (Cittadella, Padova) what is that he has eaten / what has=he.cl eaten

| (58) Geographical distribution: |

|

- (i)

- Null-subject languages (following Brandi and Cordin 1981, 1989, we analyze the clitic as the manifestation of subject agreement);

- (ii)

- ’residual‘ V2 languages (i.e., V2 languages), such as Italian and English, where finite verb movement to C is limited to well-defined contexts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We are very grateful to the VinKo research group in Verona, in particular, Anne Kruijt, Andrea Padovan, and Stefan Rabanus, and to the two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments that really helped us to improve the clarity of the argumentation. Remaining mistakes are our own. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | VinKo is a spoken corpus based on crowdsourcing; it is designed for linguistic research on audio recordings of minority languages and dialects spoken in the area between Innsbruck and the Po Valley (see Rabanus et al. 2021, http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12124/46, accessed on 1 March 2022). For a description of the platform and its methodology, see Cordin et al. (2018). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Cimbrian exhibits two classes of complementizers that clearly differ with respect to their syntax (see Panieri et al. 2006: p. 339; Grewendorf and Poletto 2009, 2011; Padovan 2011; Bidese et al. 2012; Bidese et al. 2014; Bidese and Tomaselli 2016). The first of these consists of Germanic autochthonous complementizers, which realize an asymmetric word order regarding the position of the finite verb on the right of the negation, the enclitization of the personal pronoun, and the expletive particle -da onto the complementizer. Meanwhile, the second class belongs to the borrowed complementizer ke ‘that’ and the ‘new’ complementizer umbromm ‘because’. In this class, the negation appears on the left of the finite verb, thus very similar to the usage in the main clauses, whereas the complementizer cannot host the pronoun and the particle -da:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | When the sentence is introduced by the complementizer az, the expletive tends to be absorbed due to the postalveolar fricative [z]. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Bavarian is often taken as an exception to this correlation since it is a V2 language which allows a gap in the paradigm of personal pronouns for the second person (singular and plural) and the first person plural (exactly where COMP-agreement morphology is attested), cf. among others, Biberauer (2010). The counterhypothesis that Bavarian cannot be analyzed as a semi-pro-drop language was already discussed in Rabanus and Tomaselli (2017), Tomaselli and Bidese (2019), Poletto and Tomaselli (2021), and Bidese and Tomaselli (2021). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | See Bidese and Tomaselli (2018, p. 63), first presented in June 2014 at the International Conference Understanding pro-drop. A synchronic and diachronic perspective (University of Trento). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | About the auxiliary selection in this area, see, among others, Loporcaro and Vigolo (1995) and Cordin (2009). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Lavis (U0409), Cinte Tesino (U04011), Trento (UO412/451/592/646), Tuenno (U0448), Castello-Molina (U0561), Folgaria (U0571), Pinzolo (U0578), Imer (U0607), Carano (U0624). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Levico (U0565, Male, 19 years old), Mori (U0569, Female, 21 years old). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | For a further discussion of subject agreement morphology in both Romance and Germanic varieties, we refer to Bidese and Tomaselli (2018) and Tomaselli and Bidese (2019). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | According to the extensive literature on the topic (see, among many others, Renzi and Vanelli 1983; Rizzi 1986; Poletto 2000; Roberts 2010a, 2010b), subject clitic doubling in a no-topicalization context is reported in all northern Italian dialects and in some Tuscan varieties. Interestingly this is in contrast with the realization of subject pronouns in [+V2, -NS] Germanic varieties where a preverbal subject always excludes doubling with a pronominal form (enclisis on the right of the finite verb). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | According to Casalicchio and Cordin (2020, p. 262), the absence of subject clitic doubling belongs to a more general phenomenon in these contexts, i.e., the ban of agreement (see also Bidese and Tomaselli 2021 and Padovan et al. 2021), which can be seen not only from the absence of the subject clitic but also from the absence of agreement in number and gender in the participle (cf. ii):

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Cf. ASIt search engine: <http://svrims2.dei.unipd.it:8080/asit-maldura/pages/search.jsp> (accessed on 17 December 2021); see: “Sceglie la regione” Trentino Alto Adige; “Sceglie la provincia” Trento; “Seleziona una o più marche...” soggetto > soggetto postv; sentences 4, 21, 22, 27, 28, 61, 62, 63, 67, 68. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | The role of intonation could prove fundamental in the possible distinction between postverbal right-dislocated structures (which require the clitic) versus postverbal VP internal subjects. Nevertheless, the judgment obtained for sentence (34) as opposed to (36) represents the relevant point, even if it requires further documentation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | The percentage increases if we exclude the data collected in the city (cf. footnotes 16 and 17 below): excluding the 19 informants from Verona (4 with the clitic, 15 without it), 8 of the remaining 22 records collected display an expletive clitic. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | For an analysis of the clitic a as a modal particle rather than a pronominal subject, see Benincà (1994, pp. 15–27). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Verona (4), Colognola ai Colli, Tregnago, Vigasio, Montecchio di Crosara, Bonavigo, Monteforte d’Alpone, Roveredo di Guà, Selva di Progno. If we exclude the two attestations with a collected in Montecchio di Crosara and Bonavigo, we are left with ten attestations with the clitic “l” coherently with our observation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | Verona (15), Zevio (2), Sona, Bonavigo, Montecchio di Crosara, Isola, Negrar, Bovolone, Pescantina, Veronella, Grezzana, Bevilacqua, Legnago, Illasi. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | The two examples with the clitic come from Schio and Sarego; the eight examples without the clitic come from Recoaro, Arsiero, Sarcedo, Pozzoleone, Valdagno, Bassano, Breganze, Thiene. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | We do not consider Rovigo, which seems to behave like Venice (just two records, both without the clitic); nor do we include Belluno, whose area has not yet been covered by data collected in VinKo at this stage of the project. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | A further refinement of the data with the representation of the single investigated localities in a geographical map is beyond the purpose of this paper. We want to thank one of the anonymous reviewers who encouraged us to propose a first row synthesis which could certainly be implemented in the future relying on the revised version of the VinKo corpus. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | The data presented in § 5 have been collected by interviewing dialect speakers of the relevant area (many thanks to SB, AP, EB, CP). It should be noted that they confirm the situation already presented and discussed in Benincà (1994, in particular, chapter 2, Appunti di sintassi veneta) when the ASIT project was just starting (as well as other relevant subsequent digital corpora devoted to dialectal syntax). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | See Casalicchio and Cordin (2020, p. 115): “In C[entral] T[rentino] direct interrogative sentences, a subject clitic must follow the inflected verb when no lexical subject is expressed.” | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | Note that, contrary to what we will see for the Veneto dialects (cf. 54), the cleft itself represents a further context which displays enclisis in Trentino. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | In Trentino, in copular sentences (and, hence, in cleft constructions), an expletive subject pronoun always appears as correlate of the extraposed subject clause. For a more detailed analysis, see Casalicchio and Cordin (2020, p. 317). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | Casalicchio and Cordin (2020, p. 116, footnote 30) noted that young speakers, especially in cities, seem to lose the subject clitic inversion, in particular, in connection with very frequent verbs (see also Poletto 1993 for the same phenomenon in other northern Italian dialectal varieties). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | The only exception is Venice, where the word order pattern that maintains proclisis is well attested and does not imply surprise, as already noted by Benincà (1994):

Nowadays, the variant exemplified in (b) is certainly preferred if not the only one. The exception of Venice confirms, in any case, the gradual loss of enclitic subjects in the interrogative context, starting from the East. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31 | See, among others, Bidese et al. (2014), Padovan et al. (2016), Bidese (2017a, 2017b), Bidese and Tomaselli (2021), in line with the tradition of studies on syntactic contact within the generative framework that goes back at least to Benincà (1994). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Benincà, Paola. 1994. La variazione sintattica. Studi di dialettologia romanza. Bologna: Il mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Biberauer, Theresa. 2010. Semi Null-Subject languages, expletives and expletive pro reconsidered. In Parametric Variation: Null Subjects in Minimalist Theory. Edited by Theresa Biberauer, Anders Holmberg, Ian Roberts and Michelle Sheehan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 153–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2016. The decline of asymmetric word order in Cimbrian subordination and the special case of umbrómm. In Co- and Subordination in German and other Languages. Edited by Ingo Reich and Augustin Speyer. Hamburg: Buske Verlag, pp. 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2018. Developing pro-drop: The case of Cimbrian. In Null Subjects in Generative Grammar: A Synchronic and Diachronic Perspective. Edited by Federica Cognola and Jan Casalicchio. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2021. Language synchronization north and south of the Brenner pass: Modelling the continuum. Language Typology and Universals 74: 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Andrea Padovan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2012. A binary system of complementizers in Cimbrian relative clauses. Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 90: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Andrea Padovan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2014. The syntax of subordination in Cimbrian and the rationale behind language contact. Language Typology and Universals/STUF—Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung 67: 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo, Andrea Padovan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2020. Rethinking Verb Second and Nominative case assignment: New insights from a Germanic variety in Northern Italy. In Rethinking Verb Second. Edited by Rebecca Woods and Sam Wolfe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 575–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo. 2004. Die Zimbern und ihre Sprache: Geographische, historische und sprachwissenschaftlich relevante Aspekte. In Alte Sprachen: Beiträge zum Bremer Kolloquium über ‘Alte Sprachen und Sprachstufen’. Edited by Thomas Stolz. Bochum: Bockmeyer, pp. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo. 2017a. Reassessing contact linguistics: Signposts towards an explanatory approach to language contact. Zeitschrift für Dialektologie and Linguistik 84: 126–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo. 2017b. Der kontaktbedingte Sprachwandel: Eine Problemannäherung aus der I-Language-Perspektive. In Grammatische Funktionen aus Sicht der japanischen und deutschen Germanistik. Edited by Shin Tanaka, Elisabeth Leiss, Werner Abraham and Yasuhiro Fujinawa. Hamburg: Buske Verlag, pp. 135–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bidese, Ermenegildo. 2021. Introducing Cimbrian. The main linguistic features of a German(ic) language in Italy. Energeia 46: 19–62. [Google Scholar]

- Brandi, Luciana, and Patrizia Cordin. 1981. Dialetti e italiano. Un confronto sul parametro del soggetto nullo. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 6: 33–89. [Google Scholar]

- Brandi, Luciana, and Patrizia Cordin. 1989. Two Italian Dialects and the Null Subject Parameter. In The Null Subject Parameter. Edited by Osvaldo A. Jaeggli and Kenneth J. Safir. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 111–42. [Google Scholar]

- Casalicchio, Jan, and Patrizia Cordin. 2020. Grammar of Central Trentino. A Romance Dialect from North-East Italy. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1982. Some Concepts and Consequences of the Theory of Government and Binding. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1986. Knowledge of Language. Its Nature, Origin, and Use. New York: Praeger Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccolone, Simone, and Silvia Dal Negro. 2021. Comunità bilingui e lingue in contatto. Uno studio sul parlato bilingue in Alto Adige. Bologna: Caissa Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Cordin, Patrizia, Stefan Rabanus, Birgit Alber, Antonio Mattei, Jan Casalicchio, Alessandra Tomaselli, Ermenegildo Bidese, and Andrea Padovan. 2018. VinKo, Versione 2 (20.12.2018, 09:20). Korpus im Text, Serie A, 13739. Available online: http://www.kit.gwi.uni-muenchen.de/?p=13739&v=2 (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Cordin, Patrizia. 2009. Gli ausiliari essere e avere nell’italiano regionale trentino. In Italiano, Italiani Regionali e Dialetti. Edited by Anna Cardinaletti and Nicola Munaro. Milano: Franco Angeli, pp. 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Cordin, Patrizia. 2021. Soggetti pronominali deboli. Storie e Linguaggi 7: 153–75. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, Alessandra, Cecilia Poletto, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2021. A crosslinguistic perspective on the relationship between information structure and V2. Paper presented at the CGSW 35, Trento, Italy, June 23–25; Available online: https://event.unitn.it/cgsw35/cgsw_35_paper_27_poletto_et_al.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Grewendorf, Günther, and Cecilia Poletto. 2009. The hybrid complementizer system of Cimbrian. In Proceedings XXXV Incontro di Grammatica Generativa. Edited by Vincenzo Moscati and Emilio Servidio. Siena: Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi Cognitivi sul Linguaggio, pp. 181–94. [Google Scholar]

- Grewendorf, Günther, and Cecilia Poletto. 2011. Hidden verb second: The case of Cimbrian. In Studies on German Language-Islands. Edited by Michael T. Putnam. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 301–46. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, Andres. 2015. Verb Second. In Syntax—Theory and Analysis. An International Handbook. Edited by Tibor Kiss and Artemis Alexiadou. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, vol. II, pp. 342–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Ans van Kemenade. 1995. Verb Second, Pro-Drop, Functional Projections and Language Change. In Clause Structure and Language Change. Edited by Adrian Battye and Ian G. Roberts. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 227–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kruijt, Anne, Patrizia Cordin, and Stefan Rabanus. n.d. On the validity of crowdsourced data. In Corpus Dialectology: From Methods to Theory (French, Italian, Spanish). Edited by Elissa Pustka, Carmen Quijada Van den Berghe and Verena Weiland. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Loporcaro, Michele, and Maria Teresa Vigolo. 1995. Ricerche sintattiche sul confine dialettale veneto-trentino in Valsugana: L’accordo del participio passato. In Italia Settentrionale: Crocevia di Idiomi Romanzi. Edited by Emanuele Banfi, Giovanni Bonfadini, Patrizia Cordin and Maria Iliescu. Tübingen: Niemeyer, pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Padovan, Andrea, Alessandra Tomaselli, Myrthe Bergstra, Norbert Corver, Ricardo Etxepare, and Simon Dold. 2016. Minority languages in language contact situations: Three case studies on language change. Us Wurk 65: 146–74. [Google Scholar]

- Padovan, Andrea, Ermenegildo Bidese, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2021. Circumventing the ‘That-Trace’ Effect: Different Strategies between Germanic and Romance. Languages 6: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovan, Andrea. 2011. Diachronic Clues to Grammaticalization Phenomena in the Cimbrian CP. In Studies on German Language-Islands. Edited by Michael T. Putnam. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Panieri, Luca, Monica Pedrazza, Adelia Nicolussi Baiz, Sabine Hipp, and Cristina Pruner. 2006. Bar lirnen z’schreiba un zo reda az be biar. Grammatica del cimbro di Luserna. Grammatik der zimbrischen Sprach von Lusérn. Trento and Luserna: Regione Autonoma Trentino-Alto Adige/Autonome Region Trentino-Südtirol—Istituto Cimbro/Kulturinstitut Lusérn. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto, Cecilia, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2021. Resilient Subject Agreement Morpho-Syntax in the Germanic Romance Contact Area. Languages 6: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, Cecilia. 1993. Subject clitic/verb inversion in north eastern Italian dialects. Working Papers in Linguistics 3: 95–137. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto, Cecilia. 2000. The Higher Functional Field. Evidence from Northern Italian Dialects. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto, Cecilia. 2019. More than one way out. On the factors influencing the loss of V to C movement. Linguistic Variation 19: 47–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabanus, Stefan, Alessandra Tomaselli, Andrea Padovan, Anne Kruijt, Birgit Alber, Patrizia Cordin, Roberto Zamparelli, and Barbara Maria Vogt. 2021. VinKo (Varieties in Contact) Corpus. Bolzano/Bozen: Eurac Research CLARIN Centre. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12124/46 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Rabanus, Stefan, and Alessandra Tomaselli. 2017. Räume, Grenzen und Übergänge: Subjektrealisierung im Sprachkontaktraum Deutsch-Italienisch. In Räume, Grenzen, Übergänge. Edited by Helen Christen, Peter Gilles and Christoph Purschke. Stuttgart: Steiner, pp. 283–303. [Google Scholar]

- Renzi, Lorenzo, and Laura Vanelli. 1983. I pronomi soggetto in alcune varietà romanze. In Scritti in onore di Giovan Battista Pellegrini. Pisa: Pacini, pp. 121–45. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1986. On the status of subject clitics in Romance. In Studies in Romance linguistics. Edited by Osvaldo Jaeggli and Carmen Silva-Corvalan. Dordrecht: Foris, pp. 391–419. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1990. Speculations on Verb Second. In Grammar in Progress. Edited by Joan Mascaró and Marina Nespor. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 375–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1996. Residual V2 and the WH-Criterion. In Parameters and Functional Heads. Edited by Adriana Belletti and Luigi Rizzi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Ian. 2010a. Agreement and Head Movement. Clitics, Incorporation, and Defective Goals. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Ian. 2010b. Varieties of French and the Null Subject Parameter. In Parametric Variation: Null Subjects in Minimalist Theory. Edited by Theresa Biberauer, Anders Holmberg, Ian Roberts and Michelle Sheehan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli, Alessandra, and Ermenegildo Bidese. 2019. Subject clitic languages in comparison. Subject clitics, finite verb movement, and nominative case assignment in Germanic (Bavarian, Cimbrian) and Romance (French, North Italian) varieties. In La linguistica vista dalle Alpi. Teoria, lessicografia e multilinguismo—Linguistic views from the Alps. Language Theory, Lexicography and Multilingualism. Edited by Ermenegildo Bidese, Jan Casalicchio and Manuela Caterina Moroni. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Rebecca, and Sam Wolfe, eds. 2020. Rethinking Verb Second. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| ENGLISH | CIMBRIAN | GERMAN | ITALIAN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (24) | it | ‘z/-z | es | pro | (impersonal subjects) | |

| TP expletives | ||||||

| there | -da | pro | pro | (with postverbal subjects) | ||

| CP expletives | / | ‘z | es | / | (V2 expletive) |

| TRENTO | VERONA | VICENZA | PADOVA | VENEZIA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (47) | Impersonal subject clitics | 85.7% (12 su 14) | 29.9% (12 su 41) | 20% (2 su 10) | none | none |

| Expletives with a postverbal subject [+/-hum] | (a) 18.1% (b) 94.7% (a. 8 su 44 [-hum]; b. 18 su 19 [+hum]) | none | none | none | none |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomaselli, A.; Bidese, E. Fortune and Decay of Lexical Expletives in Germanic and Romance along the Adige River. Languages 2023, 8, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010044

Tomaselli A, Bidese E. Fortune and Decay of Lexical Expletives in Germanic and Romance along the Adige River. Languages. 2023; 8(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomaselli, Alessandra, and Ermenegildo Bidese. 2023. "Fortune and Decay of Lexical Expletives in Germanic and Romance along the Adige River" Languages 8, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010044

APA StyleTomaselli, A., & Bidese, E. (2023). Fortune and Decay of Lexical Expletives in Germanic and Romance along the Adige River. Languages, 8(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010044