Abstract

Balkan varieties of Turkic, particularly those on the periphery of the Turkic spread area in the region, such as Gagauz and West Rumelian Turkish, are commonly observed to have head-initial verb phrases. Based on a wide survey, this paper attempts a more precise description of the pattern of VP directionality across Balkan Turkic and shows that there is considerable variation in how prevalent VX order is, a pattern that turns out to be more complex than the previous descriptions suggest: Two spectrums of directionality can be discerned between XV and VX orders, contingent upon type of the dependent of the verb and dialect locale. The paper also explores the grammatical causes underlying this shift in constituent order. First, VX order seems to be dependent upon whether a clause is nominal or not. Nonfinite clauses of the nominal type have XV order across Balkan Turkic, while finite clauses and nonfinite clauses of the converbial type show differing degrees of VX order depending on type of dependent and geographical location. Second, VX order appears to be an outcome of verb movement to the left of the dependent in finite clauses and nonfinite clauses of the converbial type, rather than head parameter shift.

1. Introduction and Literature Review

Southwest Turkic (also known as Oghuz Turkic) varieties have been spoken in the Balkans since around the middle of the 13th century, represented in the present day by Gagauz and the Balkan dialects of Turkish (Artun 2013, pp. xiv, xix; Johanson 2021, p. 133). These varieties, referred to as Balkan or Rumelian Turkic or Turkish, can be said to consist of three subgroups.1 The first is the West Rumelian Turkish dialect group spoken in the disputed territory of Kosovo in Serbia, North Macedonia, and western Bulgaria (Németh 1956, 1980). The second subgroup is what I refer to as North Rumelian Turkic which appears to be a continuum of dialects whose southern tip is constituted by what I will refer to somewhat inaccurately as Dobruja Turkish (i.e., the Turkish dialects of northeastern Bulgaria) and whose northernmost member is Gagauz, spoken mostly in Moldova (cf. Boev 1968 cited in Günşen 2012; Kowalski 1933, p. 26). From this perspective, Gagauz may be taken as a peripheral Turkish dialect rather than as a separate language (Johanson 2021, p. 50). Also, Dobruja Turkish likely also includes the Southwest Turkic varieties between northeastern Bulgaria and Moldova, i.e., those spoken in Constanţa and Tulcea counties in Romania. The third subgroup, namely East Rumelian Turkish, is spoken in the greater Thrace region of the Balkans.

Balkan Turkic, particularly Gagauz and West Rumelian Turkish, is commonly observed to have gone through extensive syntactic changes (see e.g., Friedman 2006; Menz 2014). These changes are due to the effects of language contact in the Balkan sprachbund largely with South Slavic languages and can reach such an extent that Balkan Turkic syntax is sometimes said to have been slavicized (see e.g., Friedman 1982, p. 60; and Doerfer 1959, p. 270; Pokrovskaja 1979; Kakuk 1960; Mollova 1970, p. 218 cited therein; as well as Johanson 2021, p. 50). More generally, the influence of language contact can be said to be driving Balkan Turkic towards Standard Average European syntax.2 Among Standard Average European syntactic features, (S)VO basic word order (cf. Haspelmath 2001, p. 1504; Dryer 1998, p. 286) is a frequently noted property of Balkan Turkic and will be investigated in depth in this paper.

The remarks above, although generally factual, should not be taken to mean that the observations in the literature on constituent order in Balkan Turkic, and more specifically on the directionality of the verb phrase, are clear and consistent. On the contrary, sources can be divided into four groups with somewhat conflicting positions regarding this issue.

The first group of scholarly works either explicitly remarks or at least implies that (S)VO order is either dominant or the norm in Balkan Turkic. For instance, according to Doerfer (1959, p. 271), Johanson (2021, pp. 790, 936), and Menz (1999, p. 40; 2014, pp. 61–62) basic word order in Gagauz is (S)VO. Kirli (2001; cited in Menz 2014, p. 61) quantifies her observations and notes that only 30% of the sentences in her Gagauz sample are verb-final (cf. the (S)OV constituent order which is canonical across Turkic). As for West Rumelian Turkish, Gülsevin (2017, pp. 110–11) remarks that nonfinal positioning of the verb is a characteristic of these varieties. Balcı (2010) observes that sentences in which the verb is in a nonfinal position are preponderant in Kosovar and Macedonian Turkish. Similarly, Jable (2010, pp. 148–49) notes that sentences with (S)OV order are rarely used in Kosovar Turkish varieties.

According to a second group of works, (S)VO order is frequent (more so than in, say, standard Turkish). For instance, Friedman (1982, pp. 33–35; 2006, pp. 40–41) notes that in West Rumelian Turkish the verb is found in a nonfinal position far more frequently than in standard Turkish. Matras and Tufan (2007) and Katona (1969, p. 165) make the same observation for Macedonian Turkish specifically, based on data from the dialects of Gostivar and Resen, respectively. İğci’s (2010, p. 129) observations on Kosovar Turkish based on data from the Vushtrri dialect are also along these lines.3

A third position is seen in Matras (2009, p. 251) who claims that Macedonian Turkish has retained the canonical (S)OV order of Turkish.4

Finally, a fourth group of works hints at a more complex and varied picture. After noting that the basic constituent order in Gagauz is (S)VO, Özkan (1996, pp. 209–10) stresses that there is much deviation from this. Finally, Günşen (2010, pp. 471–75) observes that sentences that deviate from the canonical (S)OV order are seen increasingly more frequently in Balkan Turkic as one travels westward in the Balkans.

2. Research Questions and Summary Answers

In the light of the discussion above, four main problems can be identified in the literature on constituent order in Balkan Turkic. First, as already pointed out, individual studies are not consistent with each other. Second, the observations are usually not clear enough in the sense of not being quantified where they can be. Third, they can be said to have low resolution in the sense of not being differentiated with respect to different dependents of the verb. Finally, they often have a narrow focus in that they rely on data from a single locale or variety. These issues raise the following interrelated research questions:

- (i)

- What are the extents of dependent–verb (XV) versus verb–dependent (VX) orders in Balkan Turkic?

- (ii)

- How much variation is there among different varieties of Balkan Turkic in the directionality of the verb phrase?

- (iii)

- How much variation is there in the directionality of the Balkan Turkic verb phrase with respect to different dependents of the verb?

In this paper, I first aim to address these three questions by providing a more differentiated (i.e., four dependent types) and comprehensive (i.e., 25 dialect locales) description of constituent order in the verb phrase in Balkan Turkic based on data from the Balkan Turkic Corpus (Keskin et al. in preparation). As I do so, I will quantify my answers as much as possible.

To give short and rough intimations of my answers to the three research questions, there is considerable variation across Balkan Turkic in how prevalent (S)VX order is, a pattern that turns out to be more complex than the previous descriptions suggest. First, dependents of the verb can be ranked based on their frequency of occurrence in a VX order as: bare objects < accusatives < obliques < dependent clauses. Second, varieties can also be ranked, based on how much use they make of VX order, very roughly as: East Rumelian Turkish < Dobruja Turkish < Macedonian Turkish < Kosovar Turkish < Western Bulgarian Turkish and Gagauz. More generally, VX order gradually dominates as Balkan Turkic varieties fan out over the Balkans. So, to sum up, my findings appear to be roughly in agreement with the fourth group of works summarized above, elaborating their basic position.

Second, in addition to the observational questions above, I will address the following interrelated theoretical questions that the discussion above raises:

- (iv)

- If there is indeed a preference for VX order in at least some Balkan Turkic varieties, what grammatical factor (e.g., the type of clause in which the verb and its dependents are found) underlies it?

- (v)

- Is this preference a sign of parameter shift from head-final to head-initial in the Balkan Turkic verb phrase?

Briefly, VX order in Balkan Turkic seems to be dependent upon whether a clause is nominal or not. Nonfinite clauses of the nominal type have XV order across Balkan Turkic, while finite clauses and nonfinite clauses of the converbial type show differing degrees of VX order depending on type of dependent and geographical location. Secondly, VX order appears to be an outcome of verb movement to the left of the dependent in finite clauses and nonfinite clauses of the converbial type, rather than head parameter shift.5

3. The Structure of the Paper

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section I give some brief information about the textual sources, method, and statistical tools that I have used. Next, in Section 5, I address research questions (i–iii) with a detailed exposition of my findings that reveal the two spectrums of directionality that I mentioned above: Section 5.1 is on the ranking of verb plus dependent pairs with respect to what degree they follow VX order, while Section 5.2 focuses on the ranking of Balkan Turkic varieties, based on how much use they make of VX order. In the subsequent three sections, I turn to research questions (iv–v). In Section 6, I report my findings on the role of the ‘nouniness’ of a clause in the directionality of the verb phrase. In Section 7, I present my verb movement account that connects nouniness and word order in the verb phrase. Finally, in Section 8, I argue against a rival account involving head parameter change in the verb phrase. Section 9 concludes the paper.

4. Textual Sources, Method, and Statistics

As pointed out above, the data used in this corpus-based investigation come from the Balkan Turkic Corpus. The texts in this corpus, totaling around 80 thousand words, were culled from the following sources:

- Dialect texts

- West Rumelian Turkish

- Kosovar Turkish: personal accounts in Sulçevsi (2019)

- Macedonian Turkish: folk tales in Destanov (2016) and Kakuk (1972), folk tales and personal accounts in Katona (1969)

- Western Bulgarian Turkish: folk tales and accounts of traditions in Kakuk (1961a, 1961b)

- North Rumelian Turkic

- Gagauz: Folk tales selected from numerous sources and published by Özkan (2007)

- Dobruja Turkish: miscellaneous texts in Haliloğlu (2017)

- East Rumelian Turkish: folk tales and accounts of traditions in Hazai (1960) and Kakuk (1958)

- Historical texts that show early Balkan Turkic features (the so-called ‘transcription texts’)6

- 14th century: Schiltberger’s Our Father published by Helmholdt (1966)

- 15th century: Yusof and Jakob Papas’ letters published by Brendemoen (1980), Pietro Bruto and Hadriano Fino’s bible verses in Weil (1953)

- 16th century: Filippo Argenti’s phrases in Adamović (2001), Bartholomaeus Georgievits’ dialogue, Our Father, the Apostles’ Creed, etc. in Heffening (1942), Marco Antonio Begliarmati’s dialogue in Teza (1892), the anonymous phrases in Adamović (1976), Guillaume Postel’s phrases in Drimba (1966), Reinhold Lubenau’s phrases in Adamović (1977)

- 17th century: Pietro Ferraguto’s dialogue in Bombaci (1940), Giovan Battista Montalbano’s sayings in Gallotta (1986), sample text in Du Ryer (1630), the anonymous dialogue in Blau (1868), Miklós Illésházy’s dialogue in Németh (1970), dialogue and Our Father in Herbinius (1675)

These texts were first coded sentence by sentence using a sentence annotation interface for the features below, and the features were stored in a database:

- Directionality: bare object–verb versus verb–bare object, oblique–verb versus verb–oblique, etc. (a total of 21 pairs of opposing features)7

- Clause type: main, argument, relative, adverbial

- Finiteness: finite, nonfinite

- Metadata: century, author, genre, provenance

The texts were then analyzed based on directionality, clause type, finiteness, century, and provenance, using a query module that uses the stored grammatical properties.

Three separate tools were used for statistical tests and basic mathematical operations: (i) Lancaster Stats Tools online that runs R code (Brezina 2018), (ii) Real Statistics Resource Pack for Microsoft Excel (Zaiontz 2020), and (iii) MS Excel (version 2202).

5. Spectrums of Directionality

The summary of the corpus queries on the order of the verb and four dependent types in main clauses in 25 dialect locales is given in Table 1.8

Table 1.

Distribution of verb–dependent orders in main clauses across Balkan Turkic.

The four VX combinations (i.e., Vbar, Vacc, Vobl, and VEC) are indicated in the leftmost column, sorted on their total percentages of occurrence across the 25 dialect locales (given in the rightmost column) in increasing order from top to bottom. Dialect locales are indicated in the top row, sorted on the total percentages of all VX orders observed in those locales (given in the bottommost row) in increasing order from left to right.

Two spectrums of directionality can be discerned in the table, contingent upon type of the dependent of the verb and dialect locale. (Color coding was used in the table for both the percentages and the groups of dialects for ease of interpretation.) They will be treated in more detail in the following two subsections.

5.1. Verb Plus Dependent Combinations

A slightly more detailed breakdown of verb-plus-dependent combinations can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

V+X pairs in different word orders.

The four V+X combinations are indicated in the leftmost column and the specific orders in which these combinations are seen are indicated in the top row. Thus, the intersection of V+bar and VX (viz. 35%), for instance, indicates the percentage at which the Vbar order is attested in Balkan Turkic in general. This percentage was calculated by adding up the number of examples that show a Vbar order in all 25 locales and dividing this sum by the sum of all examples with V+bar. The same approach was used, mutatis mutandis, for the other combinations. The column “Other” indicates the percentage of examples where it is impossible to establish the position of the dependent relative to the verb. These are usually cases where the constituents of the dependent are scattered on two sides of the verb.

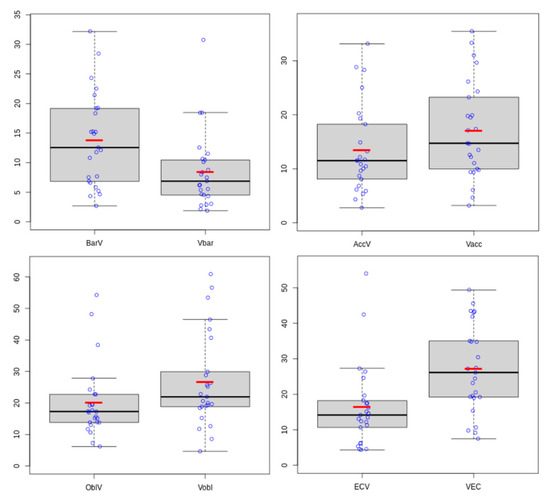

A considerably more detailed breakdown of V+X pairs is given in the four boxplots in Figure 1, visualizing the data that constitute the basis of the discussion in this section.

Figure 1.

Comparison of XV versus VX orders.

These boxplots display the following data: relative frequencies for each dialect locale (small circles) of four different V+X pairs (in reading order: V+bar, V+acc, V+obl, V+EC) along with the mean (short horizontal lines inside the grey boxes). The grey boxes represent interquartile ranges, and the long horizontal lines inside them the medians. The ‘whiskers’ extending from the gray boxes cover the highest and lowest frequencies, excluding the outliers.

As can be seen in Table 2, V+bar pairs have the most conservative orders overall: Vbar order stands at 35% in total across Balkan Turkic. This is significantly lower than the barV order (i.e., 65%), as shown by a t-test performed including all 25 locales (t(45.99) = 2.6, p = 0.012, with a medium effect size, r = 0.36, 95% CI [0.07, 0.57]). Vbar order is less frequent in terms of the number of dialect locales in which it is seen at or above 50% as well. It reaches that frequency in nine locales only.

Vacc and Vobl orders are much more common and have similar frequencies at 53% and 54% in total, respectively, across Balkan Turkic. The difference between accV and Vacc orders is statistically nonsignificant (t(47.58) = 1.49, p = 0.142). In other words, these orders have a balanced distribution across Balkan Turkic. As for oblV versus Vobl orders, the latter seems to be narrowly more dominant statistically speaking (one-tailed t-test t(44.87) = 1.78, p = 0.041, with a small-to-medium effect size, r = 0.26). Also, a higher than 50% Vacc order is seen in 16 locales, and Vobl order in 17 locales.

VEC order has a slightly higher frequency in total than Vacc and Vobl and is at 55%. This is significantly higher than the incidence of ECV order (t(47.77) = 3.13, p = 0.003, with a medium effect size, r = 0.41, 95% CI [0.14, 0.62]). The higher frequency of “Other” orders in V+EC pairs can be attributed to the size and structure of the clausal dependents that allows them to be split into two, as opposed to the bare, accusative, and oblique noun phrase dependents. Finally, there are 19 locales where a higher than 50% VEC order is observed, a little more than for Vacc and Vobl.

To put the preceding descriptions into a larger context, it might also be worth mentioning the distribution of the six possible orders of three main constituents at clause level (i.e., the permutations of subject, noun phrase dependents (‘◊’), and verb). For this, I will use data from Gagauz as a representative case and give the percentages of corresponding orders in spoken standard Turkish as a reference point, as in Table 3 (Turkish percentage data based on the data set from the RUEG corpus (Wiese et al. 2021)).9

Table 3.

Constituent orders in Gagauz and Turkish.

In both of these Southwest Turkic varieties the S◊V and SV◊ orders are the two most frequent orders, as is also the case cross-linguistically according to WALS data (Dryer 2013b), with the difference that SV◊ dominates in Gagauz, and S◊V in Turkish. One interesting observation, here, is that ◊SV word order, the least common word order worldwide according to WALS data, is the third most common order in Turkish by a very narrow margin. In total, V◊ orders (i.e., SV◊, VS◊, and V◊S) in Gagauz stand at 61.3%, while the percentage of ◊V orders (i.e., S◊V, ◊VS, ◊SV) in Turkish is 87.0%. These data show that standard Turkish is more verb-final than all Balkan Turkic varieties studied here, as would presumably be expected.

We can sum up the discussion above as in (1), which shows how conservative or progressive a verb plus dependent pair is:

- (1)

- Spectrum of Verb Plus Dependent Pairsverb+bare object < verb+accusative < verb+oblique < verb+dependent clause

These findings corroborate Özkan’s (1996, pp. 209–10) observation above that there is much variation in V+X order and place it in a more orderly perspective.

5.1.1. Typological Perspectives

The spectrum in (1) appears to be consistent with typological tendencies, in the light of data with limited scope. Based on data from the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures (WALS; Dryer and Haspelmath 2013), we can compare the positions of the “most patient-like argument in a transitive clause” (Dryer 2013a) (roughly corresponding to my category ‘acc’) and a “noun phrase or adpositional phrase…that functions as an adverbial modifier…of the verb” (Dryer and Gensler 2013) (roughly corresponding to my category ‘obl’) relative to the verb. According to those data, Vacc is the dominant order in V+acc pairs in about 44% of the languages in the WALS sample (Dryer 2013a, 2013b; Dryer and Gensler 2013), while Vobl has a slightly higher frequency than VAcc (when compared to oblV) and is at 51% (Dryer and Gensler 2013). WALS provides no data that can be used to glean the orders of dependent clauses and bare objects with respect to the verb.

The typological perspective can also be applied to interpret the ranking in (1) as a hierarchy in the typological sense: A dialect will tend not to have Vbar order unless it has Vacc order, will not have Vacc order unless it has Vobl order, and so on. This observation is supported by a Spearman’s correlation test, performed by assigning the V+X orders in Table 1 less than 50% a rank value of 1 and those above 50% a rank value of 2. The results of the test are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Spearman’s correlations (rs and significance).

According to this test, there are medium-to-strong and strong positive correlations (** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05) between all orders but Vbar–Vacc. Between these two orders there is a marginally nonsignificant (p = 0.055) medium correlation.

5.1.2. Historical Perspectives

An earlier phase of the spectrum of verb plus dependent pairs in (1) can be observed in 14th–17th century transcription texts cited above, which reflect properties of Early Balkan Turkic (see e.g., Keskin in press; Hazai 1990; Stein 2016). A summary of the data from these texts is given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparison of VX orders in two different eras.

In these sources, V+bar pairs have the most conservative orders as with modern dialects. Vbar order stands at 13% in total, which is significantly lower than the barV order, as shown by a t-test done on all 16 transcription texts (t(22.77) = 3.45, p = 0.002, with a large effect size, r = 0.52, 95% CI [0.19, 0.74]).

Vacc and Vobl orders are more common than Vbar and have comparable frequencies at 31% and 38% in total, respectively. The difference between accV and Vacc orders is statistically nonsignificant, probably due to the small sample size (t(26.61) = 0.66, p = 0.513). That is also the case for V+obl pairs, even though Vobl is more common than Vacc is (t(29.44) = 1.12, p = 0.273). In other words, both verb-initial and verb-final orders of V+acc and V+obl pairs appear to have a balanced distribution in historical texts. Thus, V+obl pairs have not tipped over to VX order yet, unlike in modern Balkan Turkic, even though the change appears to have begun and V+obl pairs look more progressive than V+acc.

In transcription texts, embedded clauses are the dependents to be found most frequently in the post-verbal position as compared to the other three dependent types, which suggests that the shift to VX order in Balkan Turkic may have begun with V+EC pairs. (The V+obl combination may have been the next constituent pair historically to begin to shift to VX order, given that it is the second most frequent VX order). Yet, even though it is at 59%, VEC is narrowly more dominant than ECV, statistically speaking, suggesting that V+EC pairs have only recently tipped over to VX order (one-tailed t-test t(29.996) = 1.88, p = 0.035, with a medium effect size, r = 0.33).

5.2. Dialect Locales

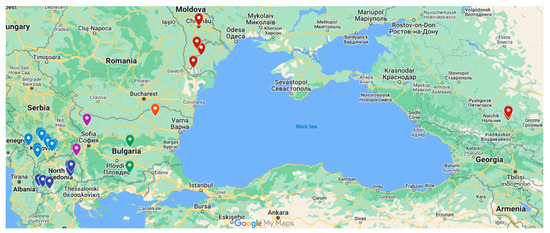

We turn now to the second spectrum, namely that of the various varieties from which the data used in this study come. These varieties are members of the three main subgroups of Balkan Turkic, and sometimes of smaller divisions within these three subgroups:10

- West Rumelian

- Kosovar Turkish: Mamuşa/Mamushë/Mamuša (Mam), Gilan/Gjilani/Gnjilane (Gji), Prizren/Prizreni/Prizren (Priz), Yanova/Janevë/Janjevo (Jan), Mitroviça/Mitrovica/Kosovska Mitrovica (Mit), Priştine/Prishtinë/Priština (Pris), Dobırçan/Miresh/Dobrčane (Dob), Vıçıtırın/Vushtrri/Vučitrn (Vuc), İpek/Pejë/Peć (Pej)

- Macedonian Turkish: Resne/Resen (Res), Ali Koç/Ali Koč (Ali), Ohri/Ohrid (Ohr), Yeni Mahalle/Jeni Maale (Jen), Konçe/Konče (Kon), Buçim/Bučim (Buc)

- Western Bulgarian Turkish: Montana (Mon), Köstendil/Kyustendil (Kyu)

- North Rumelian

- Gagauz: Kişinöv/Chișinău (Chi), Ossetia (Oss), Tomay/Tomai (Tom), Bessarabia (Bes), Odesa (Ode)

- Dobruja Turkish: Razgrad (Raz)

- East Rumelian

- Kırcaali/Kărdžali (Kar)

- Kazanlık/Kazanlăk (Kaz)

Figure 2.

Dialect locales.

East Rumelian as a whole is the most conservative subgroup, where the VX order is observed at just 29% in total. This percentage was calculated by adding up the number of examples involving the four VX orders from the two locales belonging to this group in my sample (i.e., Kărdžali and Kazanlăk) and dividing this sum by the sum of all examples with V+X combinations. The same approach was used for the other dialect groups as well.

Kosovar and Macedonian Turkish can each be split up into two groups based on the total frequency of VX orders attested. In Kosovar Turkish I (Gjilani, Mamushë, and Prizreni) and Macedonian Turkish I (Ali Koč, Ohrid, Resen, and Jeni Maale) VX order is at 34% and 41%, respectively, while Kosovar Turkish II (Miresh, Janevë, Mitrovica, Pejë, Prishtinë, and Vushtrri) and Macedonian Turkish II (Bučim and Konče) are more progressive with 62% and 57%, respectively.

Dobruja Turkish represented by Razgrad is in between East Rumelian and Kosovar Turkish I with a VX order at 38%.

At the high end of the spectrum are the varieties of western Bulgaria and Gagauz with VX orders at 66% and 67% in total, respectively.

The descriptions above can be summarized as in (2):

- (2)

- Balkan Turkic Dialect SpectrumEast Rum. Tur. (29%) < Kos. Tur. I (34%) < Dob. Tur. (38%) < Mac. Tur. I (41%)< Mac. Tur. II (57%) < Kos. Tur. II (62%) < West. Bul. Tur. (66%)/Gagauz (67%)

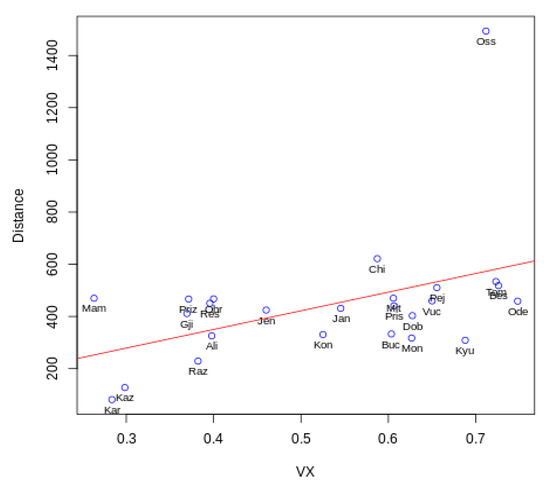

In addition to (2), there is another geographical correlate of VX order that is not explicit in that formulation. A Pearson’s correlation revealed a medium-to-high positive correlation between a dialect locale’s distance in kilometers (obtained from Google Maps) from the Kapıkule border crossing point in Turkey (the geographical southeastern tip—on the border of eastern Thrace in Turkey and the rest of the Balkans—of the network of Balkan Turkic varieties that fans out northwestward) and the frequency of VX order in that locale (r = 0.438; p = 0.029; 95% CI [0.052, 0.71]). The correlation can be visualized as in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Correlation between distance from Kapıkule and frequency of VX order.

This finding can be summed up as in (3):

- (3)

- Fanning out Effect in Balkan TurkicAs the network of Balkan Turkic varieties fans out away from the borders of Turkey, the frequency of VX orders increases with distance.

These results echo back to Günşen’s (2010, pp. 471–75) presumably impressionistic assertion above that VX order gradually dominates in Balkan Turkic as we go westward in the Balkans. The correlation between just the westward spread of Balkan Turkic expressed as a distance measure and the frequency of VX order, however, is marginally nonsignificant (Pearson’s r = 0.361; p = 0.076). One needs to take cognizance of the ‘fanning out effect’ in the spread of Balkan Turkic and factor in its northward spread as well, as I have done.

The fanning out effect is likely due to the decreasing size of Turkish-speaking communities in the Balkans in the northwestward direction. A Pearson’s correlation test showed that there is a strong negative correlation between the percentage of Turkish speakers in a municipality (data available only for Kosovo and North Macedonia (Simovski 2022; Zabërgja et al. 2013)) and the frequency of VX order in that municipality (r = −0.53; p = 0.04; 95% CI [−0.82 to −0.03]). In other words, speakers tend to use more VX order as speech communities shrink. This finding can be taken as a partial (sociolinguistic) explanation for the distribution of VX order in Balkan Turkic.

We have now answered research questions (i–iii), namely those that concern the extent and variability of XV versus VX orders in Balkan Turkic with respect to different dependents of the verb and varieties. Next, we turn to questions (iv–v), namely, to a discussion firstly of the potential grammatical factors that underlie a VX order, and next, of the case for a parameter shift from head-final to head-initial. As the reader will presently see, this discussion can only hope to be an initial theoretical exploration, and much future research is needed to fill in the details.

6. Nouniness and Directionality of the Verb Phrase

VX versus XV orders may be determined by various grammatical factors depending on the language: different settings of the head-parameter (i.e., head-initial versus head-final), the type of clause in which the verb and its dependents are found (e.g., embedded versus main clause) as in continental West Germanic; tense/aspect of the clause (e.g., future versus perfect) as in Nupe (Kandybowicz and Baker 2003), Vata, and Gbadi (Koopman 1984, p. 42 ff.); and presence of negation as in Grebo, Mursi, and Mbosi (Dryer 2013c). In addition to these, the connection between finiteness and verb placement in languages such as French, Italian, and Icelandic has also been explored by a large body of work in the spirit of Pollock (1989) (see Koeneman (2000) for an overview of the earlier literature), with the general observation that finite verbs move while nonfinite verbs remain in situ.

I explored the potential correlations between the abovementioned factors (except the head parameter) and V+X order in Balkan Turkic with a logistic regression model run using V+acc and V+obl as test cases. For this, all examples with accusative-marked and oblique dependents were identified in all 25 dialect locales (a total of 3759 examples). These were then coded for constituent order (VX and XV), as the outcome variable. In addition, explanatory variables (or predictors) which could potentially have an effect on constituent order, based on the literature cited above, were also coded. These were clause type (main, adverbial, argument, and relative), tense (past, perfective, aorist, and progressive), negation (affirmative and negative), and finiteness (finite, nonfinite clauses of the nominal type, and nonfinite clauses of the converbial type). The categories ‘nominal (nonfinite)’ and ‘converbial (nonfinite)’ refer to the following structures: Nominal clauses are the most salient dependent clauses in Turkic languages and are marked by the dedicated nominalization markers attached to the verb stems (see e.g., Kornfilt 1997, secs. 1.1.2.2.6, 1.1.2.3, 1.1.2.4, and Göksel and Kerslake 2005, chps. 24–26). Converbial clauses are adverbial clauses that are marked with suffixes reserved for adverbial functions (see e.g., Kornfilt 1997, sec. 1.1.2.4 and Göksel and Kerslake 2005, sec. 8.5.2.2).

The model revealed the category coded as ‘finiteness’ to be a significant predictor of the constituent order used (LL = 30.74, p < 0.0001; C-index: = 0.52), while clause type, tense, and negation did not have a significant effect as predictors.11,12 Note, however, that within the category of finiteness, whether a clause was nominal or not seemed to be the central factor rather than finiteness itself: XV order was used in nonfinite clauses of the nominal type in 71% of the examples, while the VX order remained at 29% (a significant difference, p = 0.041) (cf. Menz 1999, pp. 101–2). In finite clauses and nonfinite clauses of the converbial type, by contrast, the distribution of the two possible orders were balanced: XV = 52% and 57% respectively (nonsignificant differences when compared to VX order, i.e., p > 0.05).13,14 Among the nonfinite clauses of the nominal type, infinitival complement or adjunct clauses in -mAA/-mA/-mAK constitute 80% of the cases, while the overwhelming majority of the remaining 20% is made up of relative and adverbial clauses in -(y)An and -DXK. Below are two examples of typical infinitival clauses with XV orders from the region:

| (4) | a. | Çeket-miş | [ kız-ı | aara-maa ]. | (Gagauz) | |

| begin-PRF | girl-ACC | look.for-INF | ||||

| ‘He began to look for the girl’. (Özkan 2007, p. 103) | ||||||

| b. | Ben | çik-ar-ım | [ kismet-ım-i | ara-maa ]. | (Mac. Tur. II) | |

| 1SG | go.out-AOR-1SG | livelihood-1SG.POSS-ACC | search-INF | |||

| ‘I am going out to look for my livelihood’. (Destanov 2016, p. 191) | ||||||

In (4a) the infinitival clause is the bracketed segment and is a complement clause with the verb aara ‘look for’ marked in -mAA as predicate. The accusative-marked object kız ‘girl’ is to the left of the verb. The infinitival clause in (4b) is directly comparable to the previous, with the difference that it is a purpose clause.15

Then, given that the observed effect was independent of the finite versus nonfinite distinction and was present in nominal clauses (and not in converbial clauses), the conclusion suggests itself that the determining factor is not finiteness per se, but a property such as [±nominal], possibly found on a nominal head in the structure of nominal clauses (e.g., Ger°, MN°, etc. as suggested by Baker (2011) or Borsley and Kornfilt (2000)), realized by -mAA in the examples above. We can sum up these observations in the following generalization:

- (5)

- The Nouniness Condition on Constituent Order in Balkan TurkicNominal clauses have dominant XV constituent order, while finite and converbial clauses have balanced VX and XV orders.

7. The Verb Movement Hypothesis

Given that the nouniness condition in (5) only expresses a correlation, it does not say anything about the actual process that brings about that particular arrangement of constituents. The possibility that I will entertain here is that of verb movement, inspired by the literature cited above, which establishes that finite verbs move, and nonfinite verbs remain in situ in many languages, with consequences on word order (with the difference that needs to be factored in that nonfinite clauses of the converbial type are aligned with finite clauses in Balkan Turkic). A competing possibility is that the word order differences between nominal versus nonnominal clauses in Balkan Turkic is due to contrasting settings of the head parameter for each domain, i.e., a head parameter change to head-initial in nonnominal clauses. Below, I advance one preliminary argument for the ‘verb movement hypothesis’, which can be roughly formulated as in (6), and a number of counterarguments to the ‘head parameter hypothesis’ in Section 8, thereby arguing (more indirectly than directly) for the former option.

- (6)

- Verb Movement Hypothesis

- VX order in Balkan Turkic nonnominal clauses can be derived through the movement of the verb to the left of its dependent.

- XV order in nominal clauses is due to the verb remaining in situ.

I emphasize the uncertain scope of this proposal, particularly of (6a) as I do not have evidence as to precisely which cases of VX in nonnominal clauses it applies to and in which dialect groups; this requires an in-depth study with a narrower focus. One can probably safely claim that it covers the syntax of varieties with dominant VX order in finite main clauses, as well as nominal clauses in all Balkan Turkic, but the hypothesis will have to remain tentative at best at this stage, pending future evidence.16

Under a generative approach, it would be reasonable to assume that (6) would translate into structures and operations along the lines of (7):

| (7) | a. | … | [F′ F° [VP Dep Vfin ]] | ⇨ | … | [F′ Vfin … [VP Dep tVfin ]] |

| b. | … | [F′ F° [VP Dep Vfin ]] |

In (7a), which represents the derivation of a nonnominal clause with VX constituent order, the verb is first merged with a dependent to its left. At a subsequent stage of the derivation, the verb moves to a functional head position to the left of the VP (F°) across the dependent’s position, thereby yielding the VX order. In (7b), which represents the derivation of a nominal clause with XV constituent order, the verb remains in situ, yielding the XV order.17

The obvious problem with the structures in (7) is that, in the light of standard assumptions about Turkish syntax, there should not be any head positions to the left of the verb (i.e., F°) for it to move to, since all head positions would be to the right of the verb, given the head-finality of Turkish clausal architecture under these assumptions, as in (8) (see e.g., Uzun 2000):

- (8)

- … [GP … [G′ … [FP … [F′ … [VP Dep V ] … F° ] … G° ] …

The solution to this problem lies in an alternative theory of head directionality within the generative paradigm, namely one developed by Haider (1992; 2010, chp. 1; 2013, chp. 3 & 5; 2015). According to this approach, directionality is based on two premises: One, structure building or ‘merger’ is universally right-branching. Two, what is parameterized is the ‘licensing’ of complements by a lexicalized head. A lexicalized head (in the form of a lexical category such as an overt verb, or a functional category such as an overt adposition) can specify in its lexical entry that its complement be positioned to its left, thereby deriving a head-final phrase.18 Thus, this theory rules out head positions to the right of the verb that it can move to, as in (9):

- (9)

- * … [F′ … [VP Dep V ] … F° ] ⇨ … [F′ … [VP Dep tV ] … V ]

I turn now to the evidence in favor of the verb movement hypothesis, particularly its implementation in (7). First, note that in Turkish the insertion of elements such as adverbs between a bare object and a verb is grammatically marginal at best, due to the immediate structural adjacency of the verb and the bare object in a configuration comparable to (7b). The only exception to this generalization is focus particles, which behave like clitics, as in (10). Accusative–verb pairs are not subject to this constraint.

| (10) | Para | (✓da | / | ??bu sabah | / | *hesab-ın-a) | gönder-di-m. |

| money | FOC | this morning | account-2SG.POSS-DAT | send-PST-1SG | |||

| ‘I sent money as well/this morning/to your account’. | |||||||

This generalization seems to apply to Balkan Turkic as well. Interveners comparable to those in example (10) are seen in only 9% of examples with XV order that have adverbials, etc. alongside the bare objects in varieties with dominant XV order like standard Turkish (10% in all Balkan Turkic). Whereas in examples with XV order that contain accusative-marked objects, interveners are found in 58% of the examples (59% in all Balkan Turkic).

Now, against this background, one prediction of (7) is the following: Given that the verb moves out of the verb phrase in (7a), it should be possible to position various elements between the bare object and the verb in nonnominal clauses, for instance by adjoining them to the verb phrase as in (11a). Under (7b), by contrast, there is no room between the verb and the object in a nominal clause, and the only possibility would be to position any potential elements to the left of the pair. Thus, any intervener should be unacceptable comparable to the ungrammatical options in (10). This is schematized in (11b).

- (11)

- a. … [F′ Vfin … Adv [VP Bar tVfin ]]b. … [F′ F° … Adv [VP Bar (*Adv) Vnfin ]]

This prediction is borne out, as we routinely find elements positioned between verbs and bare objects in finite VX structures in Balkan Turkic, particularly in varieties with dominant VX order, as in (12):19

| (12) | a. | İç-me-yäsin | bu günnerdä | içki. | (Gagauz) | |

| drink-NEG-OPT.2SG | these days | liquor | ||||

| ‘You should not drink any liquor these days’. (Özkan 2007, p. 175) | ||||||

| b. | Öge ane-si | ver-me-y | on-a | su. | (W. Bg. Tur.) | |

| stepmother-3SG.POSS | give-NEG-PRS.3SG | 3SG-DAT | water | |||

| ‘Her/his stepmother does not give her/him any water’. (Kakuk 1961a, p. 352) | ||||||

In (12a) the temporal adverb bu günnerdä ‘these days’ is positioned between the predicate içmeyäsin ‘you should not drink’ and the bare object içki ‘liquor’. In (12b), the intervener is the oblique object ona ‘to him/her’.

This contrasts with the pattern in infinitival clauses, where we find no examples with interveners between bare objects and verbs, only focus particles as in Turkish (cf. (10)). Adverbs and comparable elements are positioned mostly to the left of a bare object–verb pair, as in (13) from Gagauz:20

| (13) | a. | O | [pek gözäl | türkü | dä | çal-maa] | becer-är-miş. |

| 3SG | very well | ballad | FOC | play-INF | do.well-AOR-PRF | ||

| ‘S/he could play ballads very well’. (Özkan 2007, p. 103) | |||||||

| b. | Gel-sin | [ben-dän | harç | iste-mää ]. | |||

| come-IMP.3SG | 1SG-ABL | tribute | request-INF | ||||

| ‘He should come to request tribute from me’. (Özkan 2007, p. 177) | |||||||

In the infinitival clause in (13a), the manner adverb pek gözäl ‘very well’ is found to the left of the bare object–verb pair türkü çalmaa ‘to play ballads’. The focus particle dä is the only element that can be positioned in between the two. In (13b) the oblique pronoun bendän ‘from me’ is likewise to the left of the bare object–verb pair.

Also, 89% of the examples which involve interveners (cf. (12)) are from varieties with dominant VX orders (i.e., Kosovar Turkish II, Macedonian Turkish II, Western Bulgarian Turkish, and Gagauz), and there is a medium to strong positive correlation among the varieties in Table 1 between (i) the ratio of the number of examples with intervening elements from each locale to the number of examples with Vbar order from each locale and (ii) the percentage of VX order in each locale, as shown by a Pearson’s correlation analysis (r = 0.408, p = 0.048, 95% CI [0.005, 0.696]). This suggests that the mechanism in (7) applies to varieties with dominant VX orders in main clauses and that the VX order in dialects with dominant XV orders may be derived differently.

8. Against the Head Parameter Hypothesis

Finally, I present some data against the ‘head parameter hypothesis’, i.e., to repeat, that the differences in the linear order of verbs and their dependents between nominal versus nonnominal clauses in Balkan Turkic are due to contrasting settings of the head parameter for each domain, i.e., a parameter change to head-initial in nonnominal clauses. The discussion is built on the head-directionality diagnostics developed by Haider (1992, 2010; see also Haider 2015; Haider and Szucsich 2022) which have a special focus on the verbal domain. Among these diagnostics I will make use of only a subset and focus on nominal and finite clauses due to the availability of data in my sample: strictness of linear order, compactness, order of auxiliaries and verbs, and edge effect.

Haider’s diagnostics are set in the following context. The linear positions of a head and its dependents can be theoretically captured in various ways: (i) they may be a reflex of their original phrase-structural positions, (ii) the outcome of a syntactic process that has moved them to their linear positions, or (iii) the outcome of post-syntactic rules of linearization. The diagnostics aim to tease the first option apart from the latter two and to distinguish between the possibilities afforded by the first option (i.e., head-final versus head-initial structures). They rely on the observation that head-final versus head-initial architectures produce distinct sets of syntactic properties.

(i) Strictness of linear order: Head-initial phrases have a strict linear order, whereas head-final ones allow word order variation (i.e., scrambling). For a head-initial verb phrase, this might mean that the objects cannot be reordered among themselves, or that they cannot be fronted across the verb, etc. Data from Balkan Turkic varieties with dominant VX order clearly violate this generalization: As I showed in Table 3, Gagauz permits all six permutations of subject, object, and verb. Also, the two ways of ordering accusatives and obliques in the post-verbal position are both attested. The same observations apply to the other Balkan Turkic varieties as well. Two examples from Gagauz can be found in (14):

| (14) | a. | Ver-er | çocaa | bıçaan-ı | |||

| give-AOR.3SG | boy;DAT | knife;3SG.POSS-ACC | |||||

| ‘S/he gives the boy his/her knife’. (Özkan 2007, p. 135) | |||||||

| b. | Kız | ver-er | o | kiad-ı | bir | markitancı-ya | |

| girl | give-AOR.3SG | that | paper-ACC | a | messenger-DAT | ||

| ‘The girl gives that note to a messenger’. (Özkan 2007, p. 153) | |||||||

In (14a), the dative object çocaa ‘to the boy’ and the accusative object bıçaanı ‘his/her knife’ follow the verb verer ‘s/he gives’ in that order. In (14b), by contrast, the order of the objects is reversed with the accusative-marked object o kiadı ‘that note’ leading.

(ii) Compactness: Head-initial phrases are compact, in the sense that interveners between the head and its dependents are disallowed. Head-final phrases do not impose such a restriction.21 As I showed in (12), Balkan Turkic allows interveners even between a verb and a bare object—the tightest possible pair in the verbal domain—in a VX structure. Such examples can be reproduced with accusative and oblique objects, and embedded clauses as dependents.

(iii) Order of auxiliaries and verbs: In VX languages, auxiliaries and quasi-auxiliaries precede the main verb in a rigid sequence, and there is no VX language that allows variation in this order. Thus, if any word order variation is possible here, the language cannot be a VX language; it must be XV. Across Balkan Turkic, Turkic auxiliaries such as ol, bil, and ver are used in their usual positions in the verb complex to the right of the verb stem, which by itself would be the property of an XV language. Additionally, novel analytical forms are attested in the region that make use of the existential and negative existential forms var ‘there is; present, existent’ and yok ‘there is not; absent, nonexistent’ in combination with a main verb and possible other elements. Assuming that the criterion of the rigid order of auxiliaries can also be applied to var/yok that take on auxiliary-like roles, one can make the following observation:22 These elements occur in a range of positions relative to the verb and its possible dependents (VXAux, AuxVX, etc.), hinting at a syntactic system that is not VX. Two examples from Gagauz are given in (15):

| (15) | a. | Pin-mää | üst-ün-ä | yok nası. |

| mount-INF | top-3.POSS-DAT | NEG:AUX | ||

| ‘One cannot mount it’. (Özkan 2007, p. 114) | ||||

| b. | Yok nası | yaklaş-maa | ||

| NEG:AUX | approach-INF | |||

| ‘One cannot approach it’. (Özkan 2007, p. 176) | ||||

In both examples, the analytical auxiliary form consists of the negative existential yok and the wh-word nası ‘how’, plus an infinitive verb marked with -mAA, expressing (im)potentiality. In (15a) yok nası is positioned to the right of the verb pinmää ‘to mount’ and its dative object. In (15b), by contrast, yok nası is to the left of the verb.

(iv) Edge effect: The head of a left-adjunct to a head-initial phrase must immediately precede the host phrase; any intervening material is disallowed. There is no edge effect in a head-final phrase. This means, for instance, that a prepositional phrase cannot left-adjoin a head-initial verb phrase because of the intervening prepositional complement. Examples of this can be found in Balkan Turkic, as in (16) from Kosovar Turkish II, suggesting that the verb phrase is not head-initial.

| (16) | a. | Ben | [PP | teri | yedi | yaşında ] | [VP | konoş-miş-om | Türçe ]. |

| 1SG | until | seven | years of age | speak-PRF-1SG | Turkish | ||||

| ‘I spoke Turkish until I was seven years of age’. (Sulçevsi 2019, p. 258) | |||||||||

| b. | Ben=y-ım | Kosovali | [PP | nice | cünülli ] | [VP | col-miş-ım | Türkiye-ye ]. | |

| 1SG=COP-1SG | Kosovar | as | volunteer | come-PRF-1SG | Turkey-DAT | ||||

| ‘I am Kosovar, I have come to Turkey as a volunteer’. (İğci 2010, p. 158) | |||||||||

In (16a) the offending temporal adverbial is a PP headed by the preposition teri ‘until’, borrowed into Kosovar Turkish from Albanian. The PP is positioned between the subject ben ‘I’ and the verb phrase konoşmişom Türçe ‘(I) spoke Turkish’, presumably adjoined to the VP. Following the edge effect, teri should be adjacent to the verb, but the prepositional complement yedi yaşında ‘seven years of age’ intervenes without a problem. (16b) is less clear: the PP headed by nice ‘as’ is again found to the left of the VP. However, it is not entirely clear whether the PP is adjoined to the VP or is a clause-initial adverbial in a clause with a null subject. Among the several examples of this kind in my sample, there are none with unambiguously positioned overt subjects.

To sum up the preceding discussion, the possibility of scrambling, the presence of interveners between the verb and its dependents, flexibility in the order of auxiliaries, and the lack of an edge effect suggest that the verb phrase in Balkan Turkic, particularly in varieties with dominant VX order, is not head-initial. In other words, the head parameter could not have shifted to the head-initial setting in nonnominal clauses.23

9. Conclusions

The frequency of VX order across Balkan Turkic is subject to much variation. First, verb plus dependent orders can be ranked as follows based on how conservative or progressive they are:

- (1′)

- Spectrum of Verb Plus Dependent Pairsverb+bare object < verb+accusative < verb+oblique < verb+dependent clause

Second, varieties can also be ranked, based on how much use they make of VX order as:

- (2′)

- Balkan Turkic Dialect SpectrumEast Rum. Tur. (29%) < Kos. Tur. I (34%) < Dob. Tur. (38%) < Mac. Tur. I (41%)< Mac. Tur. II (57%) < Kos. Tur. II (62%) < West. Bul. Tur. (66%)/Gagauz (67%).

This observation can also be expressed in more general terms as:

- (3′)

- Fanning out Effect in Balkan TurkicAs the network of Balkan Turkic varieties fans out away from the borders of Turkey, the frequency of VX orders increases with distance.

The interaction of the two spectrums of directionality brings about a pattern that is more complex than the previous descriptions suggest.

VX order in Balkan Turkic seems to be dependent upon nouniness of the clause among various grammatical factors, as summarized in the following generalization:

- (5′)

- The Nouniness Condition on Constituent Order in Balkan TurkicNominal clauses have dominant XV constituent order, while finite and converbial clauses have balanced VX and XV orders.

The mechanism underlying VX order—at least in varieties where that constituent order is the dominant one—seems to be the movement of the verb to the left of its dependent in nonnominal clauses:

- (6′)

- Verb Movement Hypothesis

- VX order in Balkan Turkic nonnominal clauses can be derived through the movement of the verb to the left of its dependent.

- XV order in nominal clauses is due to the verb remaining in situ.

Parameter shift to a head-initial setting in nonnominal clauses is unlikely to be the cause of the VX order, since empirical evidence points towards the conclusion that the verb phrase in Balkan Turkic, particularly in varieties with dominant VX order, is not head-initial.

Funding

The academic research that constitutes the foundation of this article was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) grant 313607803, as part of the projects Head directionality change in Turkic in contact situations: A diachronic comparison between heritage Turkish and Balkan Turkic (project number: SCHR 1261/3-1) and Clause combining in Balkan Turkic: Pathways and stages of contact-induced grammaticalization (project number: SCHR 1261/4-1) within the Research Unit Emerging Grammars in Language Contact Situations: A Comparative Approach (FOR 2537). The APC was covered by the IOAP of the University of Potsdam.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it relied entirely on data made public by the sources listed in the references (see also Section 4).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was also waived for the above-stated reason.

Data Availability Statement

RUEG corpus data are available at the link provided in the references. All other data used for the study can be obtained from the sources listed in the references (see also Section 4).

Acknowledgments

I thank Jaklin Kornfilt, Christoph Schroeder, Luka Szucsich, and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimers apply.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I prefer to use the more general term ‘Turkic’, except when ‘Turkish’ is the more established term in the literature, as it is not entirely clear to what degree these varieties have diverged and so whether at least some should be considered separate languages or can still be seen as dialects of Turkish. Several different classifications of Balkan Turkic varieties have been proposed in the literature. I refer the reader to Günşen (2012) for further information. |

| 2 | The term ‘Standard Average European’ is due to Whorf (1944) and, in recent studies, refers to a proposed sprachbund that includes Romance, Germanic, Balto-Slavic, the Balkan languages, etc. (see e.g., Haspelmath 1998, 2001; van der Auwera 2011). |

| 3 | Throughout the paper I refer to dialect locales with the forms used in the majority languages of the countries or territories in which the locales are located. I have no political motivations for this. |

| 4 | This apparent inconsistency in Matras’ views could perhaps be reconciled by interpreting his remarks in the following way: Macedonian Turkish may have relaxed the constraints on the use of the post-verbal objects in Turkish but not so far as to say that it has begun to stray away from the canonical (S)OV order of Turkish. In other words, there might not be a third position in the discussion; it would be integrated with the second. |

| 5 | For the purposes of this paper, we can use a definition of finiteness that is close to its traditional definition: the presence of verbal tense, person, and number. Nonfinite elements will, then, either lack these or have their nominal counterparts, as in the case of nominalizations. |

| 6 | An anonymous reviewer questions the relevance of transcription texts for diachronic studies of Balkan Turkic. This is a legitimate concern given the following background (see e.g., Hazai 1990; Stein 2016). The field of Turkology was the scene of a debate in the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s revolving around the question of whether the linguistic content of transcription texts (particularly the Georgievits and Illésházy texts) consistently reflected any particular Turkish variety. Németh (1968, 1970) argued that the texts were representative of Balkan Turkic. Kissling (1968) opposed this view with the claim that the texts simply contained idiosyncratic linguistic mixtures and reflected an at best imperfectly learned Turkish superimposed on a Balkan substrate. The debate was eventually settled, however, in favor of the former position, and a school emerged that uses transcription texts as consistent sources of data for historical linguistic studies of Turkish (see e.g., Csató et al. 2016). |

| 7 | In the context of Turkish grammar, ‘bare object’ refers to a nonspecific object that is morphologically unmarked for case. An ‘oblique’ is a dependent marked in dative, locative, or ablative case. I will use the following abbreviations for verb and dependent pairs to avoid verbose descriptions: X = any dependent, bar = bare object, acc = accusative-marked object, obl = oblique, EC = embedded clause; verb plus dependent pairs in any constituent order: V+X, V+bar, V+acc, V+obl, V+EC; verb-final pairs: XV, barV, accV, oblV, ECV; verb-initial pairs: VX, Vbar, Vacc, Vobl, VEC. |

| 8 | The explanations of the abbreviations used for the dialect locales, the geographical distributions of these locales, and the color coding used in the table can be found in Section 5.2. |

| 9 | These frequency distributions for standard Turkish differ considerably from those given in Slobin (1978, p. 19, cited by Erguvanlı 1984, p. 2): S◊V = 48%, SV◊ = 25%, VS◊ = 6%, V◊S = 0%, ◊VS = 13%, ◊SV = 8%; ◊V = 69%, V◊ = 31%. I do not know what these differences may be due to. |

| 10 | The names of the dialect locales on this list are given (where applicable) in Turkic/Albanian/romanized Serbian, Turkic/romanized Macedonian, Turkic/Moldovan, or Turkic/romanized Bulgarian. |

| 11 | This relatively low C-index suggests that other explanatory variables have an impact on constituent order in addition to finiteness. Indeed, an alternative model with ‘variety’ (i.e., the one that each example comes from) as an additional explanatory variable had a better C-index (LL = 385.92, p < 0.0001; C-index: = 0.67). However, I did not take that model into consideration, as the present exploration focuses on grammatical factors among all possible determinants of constituent order. The following factors among others may be taken into account in the future to increase the explanatory potential of alternative logistic regression models: scrambling, properties of the matrix verb (e.g., whether it is a control, modal, or aspectual verb (cf. Icelandic; see e.g., Thráinsson 1984; 2007, sec. 8.2)), specificity of the object, etc. |

| 12 | An anonymous reviewer points out that mood (comprising imperatives/prohibitives, optatives, and interrogatives) is an important determinant of constituent order in Turkish. However, a logistic regression model based on a sample of 462 examples containing accusative-marked objects from Kosovar Turkish and Gagauz showed this grammatical factor not to be a significant predictor (LL = 6.52, p = 0.368). |

| 13 | An anonymous reviewer suggests that different types of converbial clause may diverge with respect to constituent order, particularly the most common converb -(y)Xp and the others. I have not found a significant difference from this perspective between the converbs attested in my sample (i.e., -(y)Xp, -(y)ken, -DX(y)nAn, -(y)XncA, -mAdAn, -(y)ArAk) using a log-likelihood test (G test: 3.56 (5), p = 0.61), although the data suggests that a larger sample may reveal the differences that the reviewer suspects to be present. |

| 14 | The early phases of this pattern can be observed in 14th–17th century transcription texts, where nominal clauses show almost no VX order with only 4%, while that order is at 35% in finite clauses. The texts contain very few examples of converbial clauses none of which are VX. |

| 15 | Unlike infinitival clauses in -mA in standard Turkish, those in -mAA in Balkan Turkic do not change their ending depending on the matrix verb in a way that makes the case they might be bearing clear. The forms in these examples may be dative-marked (cf. ara-mağ-a [search-Inf-Dat] ‘in order to look for’ in standard Turkish) or simply be bare. The matrix verbs that take infinitival complements normally assign dative, accusative, etc. to their noun phrase complements. I follow Menz (1999) in my glossing and do not attempt to analyze the infinitival marker into possible component suffixes for the purposes of this paper. |

| 16 | I also have very little to add about what the trigger for verb movement may be or, in other words, why such an asymmetry between nominal and nonnominal clauses should exist. One can always postulate a formal feature that triggers leftward verb movement in finite and converbial clauses but that runs the risk of just being stipulative. A truly explanatory account might attempt to draw a link between verb movement and the sizes of the three domains: Nominals might be ‘truncated’, such that they lack a higher position for the verb to move to. This may or may not go hand in hand with the degree of embeddedness of nonfinite clauses (assuming that dependent clauses may be embedded to different degrees on a cline from parataxis to hypotaxis): Converbial clauses may be less embedded, i.e., be closer to the parataxis end of the spectrum than nominal clauses (Christoph Schroeder, p.c.). |

| 17 | I had pointed out in footnote 11 that finiteness (or more accurately nouniness) as a factor does not fully account for the facts, as shown by a statistical indicator. There, I had also suggested some additional factors that could be investigated in the future, such as scrambling, properties of the matrix verb, specificity of the object, etc. This also ties in with two observational facts reported above: (i) Some nonnominal clauses have XV constituent order (52–57%), and (ii) some nominal clauses VX (29%). These observations are embedded in the formulation of the nouniness condition in (5). Now, the caveat that the nouniness condition does not have full force and effect naturally extends to my theoretical implementations of it in (6) and (7). Approaching the issue from a syntax theoretic perspective, one might propose, as suggested by an anonymous reviewer, that the application of verb movement has some degree of optionality. Part of this optionality may be apparent and could turn out to be down to some of the other factors mentioned, such as the properties of the matrix verb (which may or may not trigger verb movement in the embedded clause), while part of it may have to be expressly implemented by means of technical apparatus. This is, once more, an open question that I defer to future work. |

| 18 | Haider’s theory of head directionality is closely akin to Kayne’s (1994) proposal, in that both hypothesize that phrase structures are universally asymmetric, that they are right-branching. I refer the reader to Haider (2015, pp. 93–94) for a contrastive discussion of the two approaches. |

| 19 | There were no examples of converbial clauses with bare objects and adverbs, etc. in my sample. |

| 20 | This observation may not hold for the complements of restructuring verbs, as suggested by an example in Menz (1999, p. 49) in which the restructuring verb intervenes between the infinitive verb and its bare object: bir iš iste-r-im sor-maa [a matter want-Aor-1sg ask-Inf] ‘I’d like to ask something.’ Such examples are common in my sample, but none of them contain bare objects, so I am unable to comment further on this. |

| 21 | The following was brought to my attention by Luka Szucsich (p.c.): Given the noncompactness of head-final phrases, it is surprising that no interveners should be allowed between a verb and its bare object in Turkish, as observed in (10). As was pointed out in the discussion of that example, accusative-marked objects, by contrast, can be separated from their verbs by interveners as expected under the noncompactness of head-final phrases. These observations hold in Balkan Turkic varieties with dominant XV order as well. Jaklin Kornfilt (p.c.) suggests that the unexpected pattern with bare objects may have to do with the incorporation of bare objects into the verb. |

| 22 | Christoph Schroeder (p.c.) points out that this argument weakens if var and yok in these constructions are no longer copular elements, i.e., if they just function as markers of negation and affirmation respectively. I have no evidence to rule out this possibility at this point. |

| 23 | The observations in this section also suggest that some varieties of Balkan Turkic, such as Gagauz, may belong to a third language type, rather than being either head-initial or head-final (also pointed out to me by Luka Szucsich (p.c.) and an anonymous reviewer): the so-called T3 languages with no fixed licensing direction (e.g., Slavic languages; see e.g., Haider 2013, 2015; Haider and Szucsich 2022). Like Gagauz, for instance, T3 languages resemble head-initial languages on the surface but behave like head-final ones. This is another issue to be explored in future work. |

References

- Adamović, Milan. 1976. Vocabulario Nuovo mit seinem Türkischen Teil. Rocznik Orientalistyczny 38: 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Adamović, Milan. 1977. Das Osmanisch-türkische Sprachgut bei R. Lubenau. Beiträge zur Kenntnis Südosteuropas und des Nahen Orients 25. München: R. Trofenik. [Google Scholar]

- Adamović, Milan. 2001. Das Türkische des 16. Jahrhunderts: Nach den Aufzeichnungen des Florentiners Filippo Argenti (1533). Göttingen: Pontus Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Artun, Erman. 2013. Geçmişten Günümüze Kültürel Değişim ve Gelişim Sürecinde Balkanlarda Türkçe. Hëna e Plotë “Beder” Üniversitesi 1: x–xx. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark C. 2011. Degrees of Nominalization: Clause-like Constituents in Sakha. Lingua 121: 1164–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcı, Mustafa. 2010. Kosova ve Makedonya Türk Ağızlarında Devrik Cümle Meselesi. Avrasya Etüdleri 38: 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Otto. 1868. Bosnisch-türkische Sprachdenkmäler. Leipzig: Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Boev, Emil. 1968. Bulgaristan Türk Diyalektolojisiyle İlgili Çalışmalar. In XI. Türk Dil Kurultayında Okunan Bilimsel Bildiriler 1966. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, pp. 171–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bombaci, Alessio. 1940. Padre Pietro Ferraguto e la Sua Grammatica Turca (1611). Annali del Reale Istituto Superiore Orientale di Napoli, Nuova Serie 1: 205–36. [Google Scholar]

- Borsley, Robert D., and Jaklin Kornfilt. 2000. Mixed extended projections. In The Nature and Function of Syntactic Categories. Syntax and Semantics 32. Edited by Robert D. Borsley. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 101–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brendemoen, Bernt. 1980. Labiyal Ünlü Uyumunun Gelişmesi Üzerine Bazı Notlar. Türkiyat Mecmuası 19: 223–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brezina, Vaclav. 2018. Statistics in Corpus Linguistics: A Practical Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csató, Éva Á., Astrid Menz, and Fikret Turan, eds. 2016. Spoken Ottoman in Mediator Texts. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Destanov, Ekrem. 2016. Doğu Makedonya Sözlü Geleneğinde Masallar Üzerine Bir Inceleme. Unpublished dissertation, Yildiz Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Doerfer, Gerhard. 1959. Das Gagausische. In Philologiae Turcicae Fundamenta I. Edited by Jean Deny, Kaare Grønbech, Helmuth Scheel and Zeki Velidi Togan. Wiesbaden: Steiner, pp. 260–71. [Google Scholar]

- Drimba, Vladimir. 1966. ‘L’Instruction des Mots de la Langue Turcesque’ de Guillaume Postel (1575). Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı-Belleten 14: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dryer, Matthew S. 1998. Aspects of word order in the languages of Europe. In Constituent Order in the Languages of Europe. Edited by Anna Siewierska. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 283–319. [Google Scholar]

- Dryer, Matthew S. 2013a. Order of object and verb. In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online: https://wals.info/chapter/83 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Dryer, Matthew S. 2013b. Order of subject, object and verb. In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online: https://wals.info/chapter/81 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Dryer, Matthew S. 2013c. Position of negative morpheme with respect to subject, object, and verb. In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online: https://wals.info/chapter/144 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Dryer, Matthew S., and Orin D. Gensler. 2013. Order of object, oblique, and verb. In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online: https://wals.info/chapter/84 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Dryer, Matthew S., and Martin Haspelmath, eds. 2013. The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online: https://wals.info (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Du Ryer, André. 1630. Rudimenta Grammatices Linguae Turcicae. Paris: Antoniu Vitray. [Google Scholar]

- Erguvanlı, Eser E. 1984. The Function of Word Order in Turkish Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Victor A. 1982. Balkanology and Turcology: West Rumelian Turkish in Yugoslavia as Reflected in Prescriptive Grammar. Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics 2: 1–77. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Victor A. 2006. West Rumelian Turkish in Macedonia and adjacent areas. In Turkic Languages in Contact. Edited by Hendrik Boeschoten and Lars Johanson. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gallotta, Aldo. 1986. Latin Harfleriyle Yazılmış Birkaç Osmanlı Atasözü. İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı Dergisi 24–25: 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Göksel, Aslı, and Celia Kerslake. 2005. Turkish: A Comprehensive Grammar. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gülsevin, Gürer. 2017. Yaşayan Türkiye Türkçesi Ağızlarının Tarihî Dönemlerini Belirleyebilmek İçin Bir Yöntem Denemesi Örneği: XVII. Yüzyıl Batı Rumeli Türkçesi Ağızları. Ankara: Türk Dil Kurumu Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

- Günşen, Ahmet. 2010. Rumeli Ağızlarının Söz Dizimi Üzerine I: Makedonya ve Kosova Türk Ağızları Örneği. Turkish Studies 5: 462–94. [Google Scholar]

- Günşen, Ahmet. 2012. Balkan Türk Ağızlarının Tasnifleri Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme. Turkish Studies 7: 111–29. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, Hubert. 1992. Branching and Discharge. Working Papers of the SFB 340 23. Stutgart: University of Stuttgart. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, Hubert. 2010. The Syntax of German. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, Hubert. 2013. Symmetry Breaking in Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, Hubert. 2015. Head directionality. In Contemporary Linguistic Parameters. Edited by Antonio Fábregas, Jaume Mateu and Michael T. Putnam. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, Hubert, and Luka Szucsich. 2022. Slavic Languages—“SVO” Languages without SVO Qualities? Theoretical Linguistics 48: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliloğlu, Neşe. 2017. Zavet Köyü Türk Ağzı. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Ahi Evran University, Kırşehir, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin. 1998. How Young is Standard Average European? Language Sciences 20: 271–87. [Google Scholar]

- Haspelmath, Martin. 2001. The European linguistic area: Standard Average European. In Language Typology and Language Universals: An International Handbook. Edited by Martin Haspelmath, Ekkehard König, Wulf Oesterreicher and Wolfgang Raible. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 2, pp. 1492–510. [Google Scholar]

- Hazai, György. 1960. Textes Turcs du Rhodope. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 10: 185–229. [Google Scholar]

- Hazai, György. 1990. Die Denkmäler des Osmanisch-Türkeitürkischen in nicht-arabischen Schriften. In Handbuch des türkischen Sprachwissenschaft. Edited by György Hazai. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Heffening, Willi. 1942. Die türkischen Transkriptionstexte des Bartholomaeus Georgievits aus den Jahren 1544–1548. Leipzig: Brockhaus. [Google Scholar]

- Helmholdt, Wolfgang. 1966. Das türkische Vaterunser in Hans Schiltbergers Reisebuch. Central Asiatic Journal 11: 141–43. [Google Scholar]

- Herbinius, Johannes. 1675. Horae Turcico-Catecheticae: Sive Institutio Brevis Catechetica, Cuiusdam Turcae Circumcisi. Danzig: David-Fridericus Rhetius. [Google Scholar]

- İğci, Alpay. 2010. Vıçıtırın-Kosova Türk Ağzı. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Ege University, Izmir, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Jable, Ergin. 2010. Kosova Türk ağızları. Unpublished dissertation, Sakarya University, Sakarya, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, Lars. 2021. Turkic. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kakuk, Suzanne. 1958. Textes Turcs de Kazanlyk II: Zehra Džafer. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 8: 241–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kakuk, Suzanne. 1960. Constructions Hypotactiques dans le Dialecte Turc de la Bulgarie Occidentale. Acta Orientalia Hungarica 11: 249–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kakuk, Suzanne. 1961a. Die türkische Mundart von Küstendil und Michailovgrad. Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 11: 301–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kakuk, Suzanne. 1961b. Türkische Volksmärchen aus Küstendil. Ural-altaische Jahrbücher 33: 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kakuk, Suzanne. 1972. Le Dialecte Turc d’Ohrid en Macédoine. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 26: 227–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kandybowicz, Jason, and Mark C. Baker. 2003. On Directionality and the Structure of the Verb Phrase: Evidence from Nupe. Syntax 6: 115–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, Louis K. 1969. Le Dialecte Turc de la Macédoine de l’Ouest. Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı-Belleten 17: 57–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, Cem, Taner Sezer, Christoph Schroeder, Lale Diklitaş, Zeynep Güler, Nil Özkul, Süleyman Yüceer, Ayşe N. Güler, and Ebru Özgenç. in preparation. Balkan Turkic Corpus. University of Potsdam.

- Keskin, Cem. in press. Rumelian Turkish Features in Pietro Ferraguto’s Grammatica Turchesca (1611). Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft.

- Kirli, Nadejda. 2001. N. N. Baboglu’nun ‘Legendanın izi’ Adlı Eserinin Cümle Bilgisi Yönünden İncelemesi. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Çukurova University, Adana, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Kissling, Hans J. 1968. Bemerkungen zu einigen Transkriptionstexten. Zeitschrift für Balkanologie 6: 119–27. [Google Scholar]

- Koeneman, Olaf. 2000. The Flexible Nature of Verb Movement. Utrecht: LOT Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, Hilda. 1984. The Syntax of Verbs. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1997. Turkish. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, Tadeusz. 1933. Les Turcs et la Langue Turque de la Bulgarie du Nord-Est. Krakow: Polska Akademia Umiejętności. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2009. Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron, and Şirin Tufan. 2007. Grammatical borrowing in Macedonian Turkish. In Grammatical Borrowing in Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Edited by Yaron Matras and Jeanette Sakel. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 215–27. [Google Scholar]

- Menz, Astrid. 1999. Gagausische Syntax: Eine Studie zum kontaktinduzierten Sprachwandel. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Menz, Astrid. 2014. Gagauz. Journal of Endangered Languages 3: 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mollova, Mefküre. 1970. Coïncidences des zones linguistiques bulgares et turques dans les Balkans. In Actes du 10e Congrès International des Linguistes. Bucharest: Editions de l’Académie de la Republique Socialiste de Roumanie, pp. 217–21. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, Gyula. 1956. Zur Einteilung der türkischen Mundarten Bulgariens. Sofia: Bulgarische Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, Gyula. 1968. Die türkische Sprache des Bartholomaeus Georgievits. Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 18: 263–71. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, Gyula. 1970. Die türkische Sprache in Ungarn im siebzehnten Jahrhundert. Bibliotheca Orientalis Hungarica 13. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, Gyula. 1980. Bulgaristan Türk Ağızlarının Sınıflandırılması Üzerine. Türk Dili Araştırmaları Yıllığı-Belleten 1981: 113–67. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, Nevzat. 1996. Gagavuz Türkçesi Grameri. Türk Dil Kurumu Yayınları 657. Ankara: Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu. [Google Scholar]

- Özkan, Nevzat. 2007. Gagavuz Destanları. Türk Dil Kurumu Yayınları. Ankara: Atatürk Kültür, Dil ve Tarih Yüksek Kurumu. [Google Scholar]

- Pokrovskaja, Ljudmila A. 1979. Nekotorye osobennosti sintaksisa gagauzskogo jazyka i balkansko-tureckix govorov. In Problemy Sintaksisa Jazykov Balkanskogo Areala. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1989. Verb Movement, Universal Grammar, and the Structure of IP. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 365–424. [Google Scholar]

- Simovski, Apostol. 2022. Census 2021; Republic of North Macedonia State Statistical Office. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.mk/PrikaziSoopstenie_en.aspx?rbrtxt=146 (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Slobin, Dan. 1978. Universal and Particular in the Acquisition of Language. Presented at workshop-conference on Language Acquisition: State of the Art, Philadelphia, PA, USA, May 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Heidi. 2016. The Dialogue between a Turk and a Christian in the Grammatica Turchesca of Pietro Ferraguto (1611). Syntactical features. In Spoken Ottoman in Mediator Texts. Edited by Éva Á. Csató, Astrid Menz and Fikret Turan. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 161–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sulçevsi, İsa. 2019. Kosova Türkçesi ve Fiil Yapıları. Unpublished dissertation, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

- Teza, Emilio. 1892. Un Dialogo Turco Fatto in Italia nel Cinquecento. Rendiconti della R. Accademia dei Lincei 1: 391–407. [Google Scholar]

- Thráinsson, Höskuldur. 1984. Different types of infinitival complements in Icelandic. In Sentential Complementation. Edited by Wim de Geest and Yvan Putseys. Dordrecht: Foris, pp. 247–56. [Google Scholar]

- Thráinsson, Höskuldur. 2007. The Syntax of Icelandic. Cambridge Syntax Guides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uzun, Engin. 2000. Anaçizgileriyle Evrensel Dilbilgisi ve Türkçe. Istanbul: Multilingual. [Google Scholar]

- van der Auwera, Johan. 2011. Standard Average European. In The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide. Edited by Bernd Kortmann and Johan van der Auwera. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, vol. 1, pp. 291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Weil, Gotthold. 1953. Ein unbekannter türkischer Transkriptionstext aus dem Jahre 1489. Oriens 6: 239–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whorf, Benjamin L. 1944. The Relation of Habitual Thought and Behavior to Language. ETC: A Review of General Semantics 1: 197–215. [Google Scholar]