Abstract

This paper investigates additive links to discourse alternatives in picture comparison dialogues produced by adult native speakers of English and German. Additive relations are established across turns when participants are confirming the presence of matching objects on both pictures (A: “I have X”. B: “I also have X”). Speakers thereby describe their own picture and construe the interlocutor (or rather: the interlocutor’s picture) as a discourse alternative. Whereas the vast majority of the confirming descriptions in German contain an additive particle (auch), less than half of the corresponding confirmations in the English data do (“also”, “too”, etc.). Numbers differ even more drastically in polarity questions (“Do you (also) have X?”) that are equally typical for the dialogue task. Such frequency differences are at odds with recent accounts treating additive particles as being quasi obligatory when their presupposition is satisfied. An in-depth contrastive analysis of lexical, syntactic and information structural properties reveals that the default mapping of information units on syntactic functions (subject) in conjunction with the SVO word order of English leads to a structure in which subject, initial (topic) position and the particle’s associated constituent coincide. This would make the relation to its discourse alternative more prominent than warranted by the dialogue task and speakers of English leave this relation unmarked or resort to alternative constructions instead. The V2 syntax of German, on the other hand, allows for a dissociation of discourse topic and associated constituent. It allows the speaker to topicalize reference to the matching object, to highlight the confirmation of its presence on the speaker’s picture, and to relate the changing information to its discourse alternative in a non-contrastive way.

Keywords:

discourse alternatives; dialogue; English; German; additive particles; syntax; information structure 1. Introduction

This paper investigates speakers’ language-specific ways of construing particular information units as discourse alternatives and linking them together with the help of additive focus particles. To this end, language production data were elicited from speakers of English and German solving the same communicative task. Dyads of speakers were invited to compare mutually invisible pictures and to exchange information about similarities and differences, linking their own utterances to their interlocutors’ preceding descriptions in coherent ways. To this end, speakers can use additive focus particles like “too”. In (1), speaker B confirms that “having three fruits” is a valid description of her1 own picture. The particle “too” associates with the changing information (the referent of the first-person subject pronoun = B). It comes with the presupposition2 that the set of alternatives is not empty, i.e., the given description holds for at least one contextually relevant discourse alternative. In (1) the only other member of this set is the first-person subject pronoun of the preceding utterance that is referring to speaker A. The particle creates an additive link between the information unit expressed in its associated constituent (henceforth AC, surrounded by square brackets) and the discourse alternative. It marks that the alternatives are not mutually exclusive with regard to the given state of affairs, or, put the other way around, that a common denominator (having three fruits) is valid for both.

| (1) | A: | I’ve got three fruits |

| B: | [I] have three fruits too (E.03–04)3 |

While the term “focus particle” suggests that the particle’s AC corresponds to the information focus of the utterance, the exchange under (1) casts some doubts on the generalizability of this idea. The first-person pronouns produced by A and B refer to the deictically given discourse participants. As required by the task, each of them makes claims about their own picture, and similarities (as well as differences) between the pictures are expected. A reading according to which speaker B wants to inform A that A cannot have a definite set of three fruits, because B (and only B) has it, is excluded in the context. The information unit “speaker’s picture” is thus given and rather topical than focal, and there is no reason to assume a contrastive relation between the relevant discourse alternatives.

It is therefore not surprising that the information status of the AC of additive particles has been a matter of debate in the literature. There is a consensus that it is a focus when the particle is preceding its AC. In German, speaker B’s turn in (1) could be translated with (as least) the variants given in (2).

| (2a) | auch | [ich] | habe | drei früchte |

| part | pro-1sg | have-1sg | three fruits | |

| (2b) | [ich] | habe | auch | drei früchte |

| pro-1sg | have-1sg | part | three fruits | |

| (2c) | drei früchte | habe | [ich] | auch |

| three fruits | have-1sg | pro-1sg | part |

In (2a) the particle precedes its AC. The focal accent falls on the AC, whereas the particle itself is unstressed. As pre-posed particles did not occur in the current data set (even though they are frequent in other types of discourse; Reimer and Dimroth 2021), they are largely disregarded in the following. In both (2b) and (2c), the particle is stressed. The variants differ, however, in the position of its AC.

According to Krifka (1998), with stressed particles following their AC, both, the discourse alternative and the AC of the particle should be analysed as contrastive topics. He assumes an implicit discourse question like “What do A and B have in their pictures?”. The statement “Speaker A has three fruits” is an incomplete answer to that question and the expression referring to its topic (Speaker A) is therefore marked by a raising accent indicating that a statement about the missing alternative (Speaker B) will follow to “close” the question. A contrastive topic marked with a so-called bridge contour (Büring 2016) thus triggers alternatives on its own, in addition to the focus alternatives. Sæbø (2004) suggests that only the AC of the particle is a contrastive topic whereas there is typically nothing contrastive about the preceding discourse alternative. He provides convincing examples in favour of unmarked aboutness topics as discourse alternatives in narratives. When additive relations are established across turns in a dialogue like (1), a contrastive topic intonation in speaker A’s utterance seems even less likely. Both discourse participants are aware that the underlying discourse question will only be completely answered after the second speaker’s description, so there is no need to indicate incompleteness in the first place. According to Dimroth (2004), even the particle’s AC does not have to be contrastive. Next to a contrastive topic, any piece of background information can be used to establish additive links to discourse alternatives. This seems a likely analysis for (2c) where the sentence initial topic is dissociated from the particle’s AC.

In case the AC does not correspond to the utterance’s focus, the question arises as to what the focus of the relevant utterances should be. Consider the data in (1) again. Given the implicit discourse question in the background, the direct object (“three fruits”) is the most likely focus constituent of speaker A’s statement. In B’s utterance, however, this piece of information is given (maintained) and deaccented accordingly. In fact, the entire utterance is a repetition of what A just said about his picture, this time with reference to B’s picture, though. The particle “too”, however, is stressed—suggesting that the particle itself might be the focus of B’s utterance. This analysis would then raise the question, what the focus alternatives would be. Krifka (1998) and Dimroth (2004) suggest that the alternative of stressed additive particles like English “too” or German auch is negation. A’s description of his picture is presented to B with the aim to find out whether B can or cannot confirm it with respect to her own picture. The polarity of B’s answer is thus at issue.

It seems then that we are dealing with two types of alternative sets. Whereas the particle marks an additive relation between speaker B (the particle’s AC) and speaker A (or rather speaker B’s and speaker A’s picture), the intonationally marked information focus of B’s utterance falls on the particle itself and establishes a focal contrast between the selected alternative (confirmation) and the deselected alternative (negation).

Let us come back to the first alternative relation for a moment. As briefly mentioned above, additive particles are treated as presupposition triggers. The particle “too” in B’s utterance in (1) triggers the presupposition that there is an alternative to its AC for which a similar claim can be made. Recent accounts investigate this relation more closely and insist that additive particles are quasi compulsory when their presuppositions are satisfied (Amsili and Beyssade 2010; Eckardt and Fränkel 2012). This is the case in (3) (from Amsili and Beyssade 2010). Without the additive particle, recipients would be encouraged to interpret “Mary is sick” as being in contrast to or as correcting the statement “John is sick”. This problem arises because similar claims are made about John and Mary. Krifka (1998) calls this the distinctiveness condition that is evoked by contrastive topics: “The use of too allows to violate distinctiveness by explicitly stating a discourse relation.” (p. 125). Based on Sæbø (2004), Schmitz et al. (2018, p. 11) refer to additive particles as “anti-contrastivity markers” and point out that they can also fulfil this function when discourse alternatives are not as explicit as in (3).

| (3) | John is sick. [Mary] is sick, too. |

An analysis of additive particles as being obligatory under the given circumstances is, however, at odds with the language-specific frequency differences reported in some studies. Benazzo and Dimroth (2015) summarize evidence for the frequency of additive particles in German and French newspaper corpora, literary translations and their own elicited production studies and find that German auch is 2–3 times more frequent than French aussi. They also find that this tendency already holds for the production of young children acquiring German or French as L1s.

Speakers of German and Dutch also produced significantly more additive particles than speakers of French and Italian in a film-retelling task (Dimroth et al. 2010). The authors concluded that language specific ways to organize the information flow in discourse led speakers to construe particular information units as relevant discourse alternatives in some languages more than others. If a core function of additive particles is to avoid unwarranted contrasts, then such contrasts may simply arise more often in some languages than in others because of the speakers’ preferences for structuring information in discourse. These preferences in turn arise from typological differences between the relevant languages, in particular, their syntax and their repertoire of marked work orders, their prosodic systems, and their set of particles expressing additivity, affirmation and contrast. These claims mainly relate to narrative monologues, however, i.e., a type of discourse that leaves speakers with quite some freedom for the selection and organisation of information in response to a given stimulus.

The oral picture description dialogues analysed in the current study exert more constraints, since speakers must adapt to what was said before and thereby align content and information structure of their utterances to their interlocutors’ preceding turns. Given that the majority of the objects depicted on the picture stimuli were similar, the task provided a favourable context for marking additive relations. We had no concrete expectations concerning the relative amount of additive markings in English, but the data revealed quite dramatic frequency differences: whereas the fourteen dialogues available for English contain a total of 28 additive particles (“too”, “also”, “as well”, “either” and “neither” counted together), the ten dialogues available for German contain a total of 88 additive particles (only auch).

Typical exchanges consist of a description of objects and their locations/properties by one speaker and a confirmation or rejection by the other. Only confirming utterances provide a context for additive particles. Whereas such contexts almost invariably elicited additive particles in German (4), quite a few speakers got by without additive particles in English (5).

| (4) | A: | oben rechts kommt bei mir ne gelbe teekanne |

| top right comes on mine (= on my picture) a yellow teapot | ||

| B: | ja, die hab [ich]auch (G.03–20) | |

| yes, I have that too4 | ||

| (5) | A: | so, I have toothpaste |

| B: | I’ve got toothpaste (E.09–10) |

Recall that there is, in principle, no contrast to be avoided, since B’s statement cannot be misunderstood as challenging A’s statement in any way. The nature of the task makes clear that A and B are talking about two pictures and two tokens of the relevant objects. In a way, explicitly marking that B’s claim is meant to hold in addition to A’s is simply redundant. Still, additive particles abound, at least in German, and a literal translation of the sequence in (5) feels distinctly odd and is not attested in the data. It is the aim of the current paper to find out what motivates these differences. This research question has several sub-questions, namely:

- (a)

- Do English speakers simply leave the relation unmarked as in (5) or do they prefer a different way of expressing a confirmation instead?

- (b)

- Are there structural properties of the relevant utterances that make the integration of additive particles quasi obligatory in German and rather non-preferred in English?

- (c)

- Does this follow from more general typological differences (SVO vs. V2) and their impact on the organisation of particular information units in discourse?

In the results section, these questions will be addressed in turn. Since the analysis consists of a series of steps, interim results will be discussed directly following their presentation. The paper ends with a more general Discussion and Conclusion section.

2. Materials and Methods

In a picture comparison task (“Spot the difference!”), pairs of participants were asked to compare two mutually invisible photos with twelve randomly distributed everyday objects (see Supplementary Materials) and to identify as many differences as possible in a limited amount of time (five minutes). While most objects (henceforth called “entities” in order to avoid confusion with grammatical objects) were equally presented on both pictures, some had changed position or properties (e.g., a toilet roll with and one without paper) and some had been replaced by different entities on one of the pictures. The photos were handed out to the participants in the form of A4 colour prints.

Participants were 28 adult native speakers of English (14 dyads) and 20 adult native speakers of German (10 dyads). All participants had grown up in monolingual families. They were students of the universities in York and Münster, respectively, and they were rewarded for their participation.

Participants were seated left and right of a cardboard partition that prevented them from looking at each other’s pictures. No fixed roles were assigned5, i.e., it was up to the interlocutors to find out how they wanted to go about the task. Given the time pressure, most dyads quickly decided that taking turns in providing information about one picture and subsequently confirming/rejecting it with respect to the other picture was an efficient solution.6 During the conversation, roles typically shifted several times. Dialogue partners could, for example, reject a description proposed by their interlocutor and immediately continue with a description of their own picture. The production of the dialogues was recorded and orthographically transcribed without going in detail about types of backchannel behaviour (hmhm), the timing of overlaps or the lengths of pauses.

The resulting dialogues were then broken down into a number of smaller units consisting of a description provided by one speaker and a subsequent confirmation or rejection uttered by the other. Typically, in a first move, interlocutor A names and locates an entity on his picture (e.g., “There is a yellow teapot in the top-right corner”). First moves can optionally contain a reference to A or to his picture (e.g., “I have a yellow teapot in the top-right corner”; oben rechts ist bei mir eine gelbe teekanne—“top right is in mine7 a yellow teapot”). First moves can also be presented in the form of a polarity question instead of an assertion (“Do you have a yellow teapot in the top-right corner?”). In this case, A encodes the information about his picture in the presupposition of the question. Speaker A can only ask this question because there is a teapot in the top-right corner of his picture.

In a second move, interlocutor B can then either reject or confirm A’s proposal with respect to her own picture. In the following, only confirming second moves following first move statements (not questions) will be analysed since they provide the conditions for the addition of discourse alternatives. Confirmations can in principle concern the existence, the location or the properties of an entity. In the majority of the cases, confirmation is simply achieved by affirmative particles (“yes”/ja), sometimes extended or replaced by adverbial modifiers (“(yeah) exactly”/(ja) genau) or the repetition of a single constituent from the interlocutor’s preceding first move description.

In a considerable number of cases, however, B opts for a fuller confirmative move. There are two options then. In a comparison, B explicitly states the similarity of both pictures (“I have the same”). In a description, B focuses on the properties of her own picture instead (“I’ve got a teapot”)8. It is only in context that a confirming second move description can be distinguished from a first move description, unless it contains some anaphoric expression (“I’ve got the teapot”; “I’ve got that”) or an additive particle (“I’ve got a teapot as well”). In the latter case, B construes A (or rather: A’s picture) as a discourse alternative and establishes an additive relation between both. Recall that in the task at hand, explicitly marking this additive relation in a confirming statement or a polarity question (“Do you also have a yellow teapot?”) is in principle redundant. It is clear from the start that both interlocutors are talking about their own pictures and that B’s description adds to A’s without challenging it. The descriptions are not mutually exclusive and B’s confirmation cannot be misunderstood as contrastive or corrective, since B cannot even see A’s picture.

3. Results and Discussion

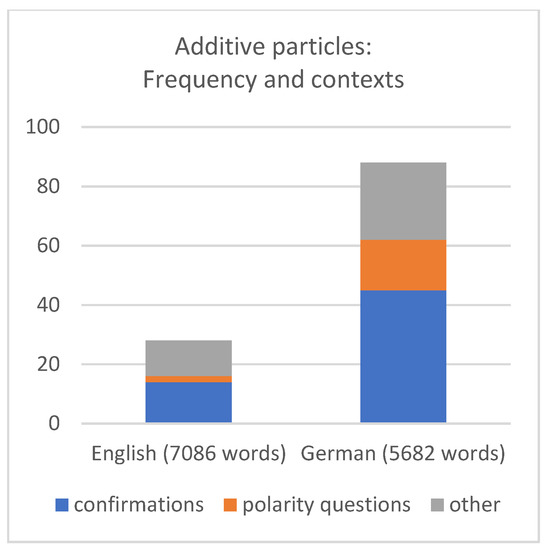

There are substantial differences between German and English with respect to the absolute frequency of additive particles. The ten German dialogues contained more than three times more additive particles than the fourteen English dialogues. Figure 1 shows their distribution across polarity questions, confirmations and other contexts.

Figure 1.

Absolute frequency of additive particles in relation to the number of words in the two sub-corpora.

Examples for confirmations can be found in (1) and (4) in the Introduction; (6) is an example for a polarity question. The remainder (“other”) subsumes the addition of entities in first move descriptions, i.e., an enumeration of entities from only one speaker’s picture (7), the addition of possible labels for a given entity (8) and some ambiguous cases.

| (6) | ist der apfel [bei dir]auch oben rechts? (G.12–13) |

| “is the apple in yours also top right?” | |

| (7) | okay, I have an orange in the top-left and a pear at the bottom (..) but I also have [an apple] (E.13–14) |

| (8) | links daneben könnte eine zitrone sein aber auch [eine limone], ziemlich rund, grünlich-gelb (G.18–19) |

| “left next to it could be a lemon but also a lime, rather round, greenish-yellow” |

As shown in Figure 1, these “other” cases are also more frequent in German than in English, but we will only consider confirmations and polarity questions in the remainder of this paper.

3.1. Confirmations

In this task, speakers can choose between two types of confirmations. The first possibility is a comparison with what was said before. In this case, speakers explicitly mark the similarity between both pictures. Confirming comparisons differ in the amount of information they contain (A: “There is a yellow teapot in the upper right corner” B: “I have the same teapot/I have the same”). Their exact meaning depends on the content of the preceding first move description. This is different in confirming descriptions that do not contain lexical items expressing the similarity between both pictures. Instead, speaker B makes an independent statement about her own picture. Confirming descriptions can, but need not contain additive particles (A: “There is a yellow teapot in the upper right corner“ B: “Okay I’ve got a teapot (as well)”).

Both confirming comparisons and confirming descriptions can occur with and without elliptical reductions. Given that they often directly follow a first move description provided by the other speaker, they have in fact a strong tendency to be elliptical (A: “I have a yellow teapot right of the orange“ B: “Same/So do I/Me too”). Speakers tend to leave out material that is repeated from the preceding context and thus highly activated.

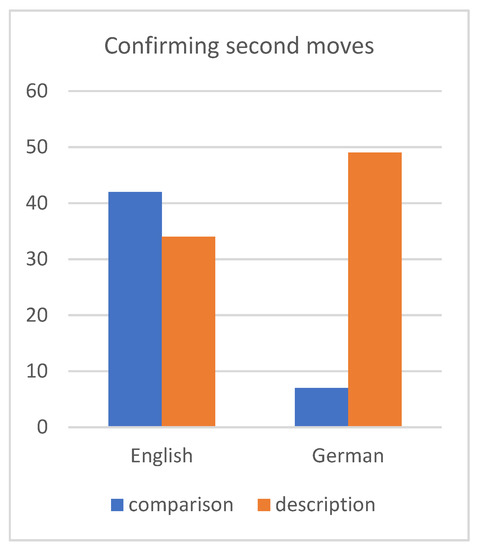

Whereas speakers of English produced comparisons and descriptions with roughly the same frequency in their confirming second moves, this was not at all the case for speakers of German who strongly preferred descriptions, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Types of confirming second moves, absolute numbers.

A Pearson’s chi-square test revealed that the distribution of second move comparisons versus second move descriptions in the production of the two language groups was significantly different: X2(1) = 25.26, p < 0.001. Both types of confirmations, i.e., comparisons and descriptions, will be addressed in turn.

3.2. Comparisons

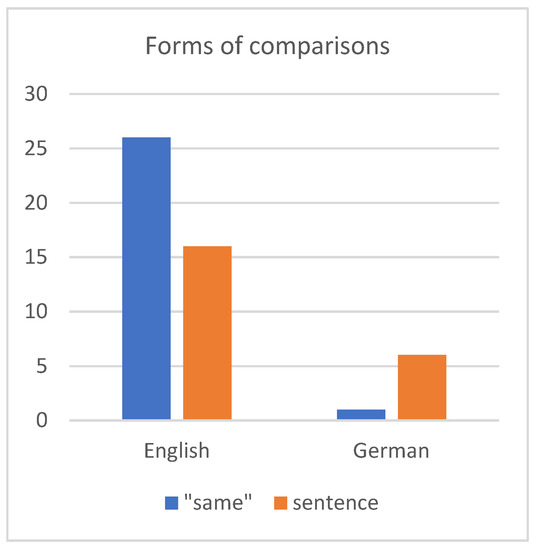

Confirming comparisons contain lexical expressions like “same”, “like”, “similar”, “identical” or their German counterparts. They explicitly mark that the attributes ascribed to speaker B’s picture match those of speaker A’s picture. There is thus no need to establish an additive relation between the two pictures and none of the comparisons contains an additive particle. They nearly always follow directly after speaker A’s first move description and are often elliptical. More than half of the English comparisons consist of the word “same” used in isolation (“same” in Figure 3; see (9) below). All comparisons containing a finite verb were coded as “sentence” (examples (10)–(12)).

Figure 3.

Forms of comparisons, absolute numbers.

A Pearson’s chi-square test revealed that the distribution of verb containing sentences versus elliptical utterances of “same”(or equivalent) produced in second move comparisons by the two language groups was significantly different: X2(1) = 5.49, p < 0.05. Both types of confirmations will be addressed in turn.

| (9) | A: | and then to the right of the highlighter I’ve got sellotape |

| B: | same (E.26–27) | |

| (10) | A: | next to my highlighter is a sellotape dispenser |

| B: | I have the same thing, okay (E.19–21) | |

| (11) | A: | I have an orange in the top-left corner |

| B: | so do I (E.17–18) |

There were only very few comparisons in German. With the exception of a single example (13), they were all of the “sentence” type.

| (12) | A: | (der apfel ist) oben rechts zwischen der birne und der teekanne so |

| “the apple is top right between the pear and the teapot” | ||

| B: | alles klar, ist bei mir identisch (G.12–13) | |

| “all right, it‘s identical in mine” | ||

| (13) | A: | dann ist da ein blaues logo oder sowas drauf (..) und weiße schrift die man aber nicht lesen kann |

| “then there is a blue logo or something (..) and a white writing that you cannot read, however” | ||

| B: | Ja, dito (G.16–17) | |

| “yes, ditto” |

As shown in Figure 3, more than half of the English comparisons consist of the adjective “same” used in isolation that seems to have no suitable counterpart in German9. The German adjective gleich (“same, similar”) did not occur in this function. The overall frequency differences between comparisons and descriptions shown in Figure 2 might thus be due to the English speakers’ preference for this economic solution that is unavailable in German. Due to this lexical gap, speakers of German are more or less forced into “sentence”-like confirmations—including descriptions that attract additive particles (or at least provide an opportunity for their use). Even “sentence”-like comparisons are, however, more frequent in English than in German, so the availability of economic one-word replies cannot be the only reason for the increased number of comparisons in English. Instead, it could be a result of English speakers’ avoidance of confirming descriptions, and this in turn could have to do with the need to establish and possibly mark an additive discourse relation that is not easily compatible with the available lexical and syntactic resources.

3.3. Descriptions

Unlike comparisons, description do not lexically signal sameness. Rather, speaker B talks about her own picture only. Confirming descriptions either confirm an entities existence (“Yes, I have a teapot (too)”), or they pick up the entity introduced by speaker A and confirm its properties (“Yes, my teapot is yellow (too)”).

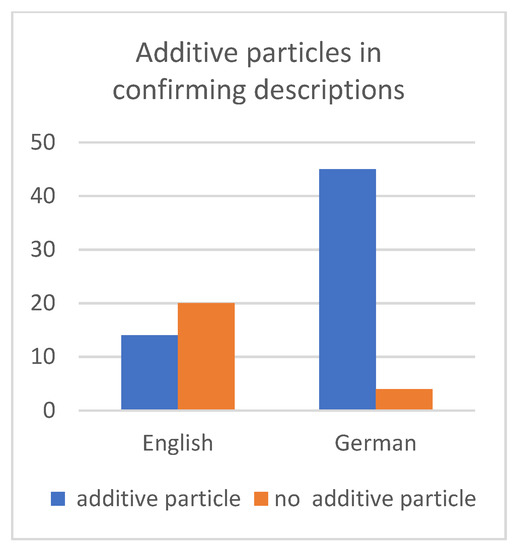

The corpus consists of 83 confirming descriptions. As shown in Figure 4, they are less frequent in English than in German, despite the bigger corpus, and importantly, the majority of the English descriptions does not contain an additive particle, whereas this is clearly the exception in German.

Figure 4.

Additive particles in confirming descriptions, absolute numbers.

A Pearson’s chi-square test showed that the proportion of additive particles in second move descriptions was significantly different in the two language groups: X2(1) = 25.06, p < 0.001. Like comparisons, descriptions can come in the form of full sentences or ellipses. Elliptical descriptions in both English and German consist only of an obligatory additive particle and its AC (14). Whereas speakers of German use this possibility in about 50% of all cases, there are only four elliptical utterances in English. Descriptions without additive particles always contain a verb in both languages. (15)–(18) are examples for sentence-type confirming descriptions with and without additive particles.

| (14) | A: | links ganz oben hab ich ne orange |

| “left at the top I have an orange” | ||

| B: | [ich]auch (G.10–11) | |

| “me too” | ||

| (15) | A: | I have a toothpaste right next to that |

| B: | [I] have a toothpaste there as well (E.17–18) | |

| (16) | A: | (das abstreifding) ist rechts vorne |

| “the dispenser is front right” | ||

| B: | ja der ist rechts vorne (G.01–02) | |

| “yes it is front right” | ||

| (17) | A: | in the top-right corner there’s a yellow teapot, like a plastic teapot |

| B: | Yeah I’ve got a teapot (E.22–23) |

Even though confirming descriptions with additive particles are possible in English (15), speakers do without in the majority of the cases (17). In German, however, descriptions without additive particles are exceptional.

Why is it possible to leave the additive relation between the information unit referring to the current speaker (or her picture) and its discourse alternative unmarked in English, but not in German? Why do confirming descriptions like (17) leave an impression of incompleteness to speakers of German even though the additive particle is in principle redundant? In order to answer these questions, we will study the properties of the confirming descriptions in more detail and find out whether their structure differs as a function of the presence vs. absence of an additive particle. We will first examine the way the changing information unit is encoded.

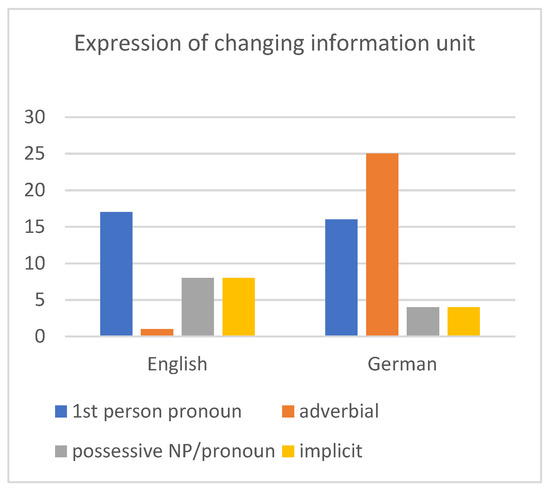

In principle, all descriptive confirmations have a bipartite structure. There is maintained information, i.e., information about the descriptive properties of the picture that speaker A proposed and that speaker B confirms, e.g., the presence of a given entity, its properties, its location, or a combination thereof. In addition, there is changing information. What has changed in B’s second move in comparison to A’s first move is the reference to the picture under discussion (A’s picture vs. B’s picture). This information unit can be encoded in different ways: First person pronouns (“I have a yellow teapot (too)”), adverbials referring to the pictures (“There is a teapot in mine (as well)”), and possessive NPs or pronouns (“My teapot/Mine is yellow (too)”) occur next to the possibility to leave this information unit implicit (“The teapot is yellow”). Figure 5 shows the frequency of the different variants.

Figure 5.

Realisation of changing information unit (reference to speaker’s picture) in confirming descriptions, absolute numbers.

First person pronouns are the preferred way of encoding reference to the changing information in English, whereas adverbials, more specifically bei mir (“in mine”) prevail in German. Possessives and implicit cases are second most common in English and comparatively rare in German. They are used with equal frequency within both languages.

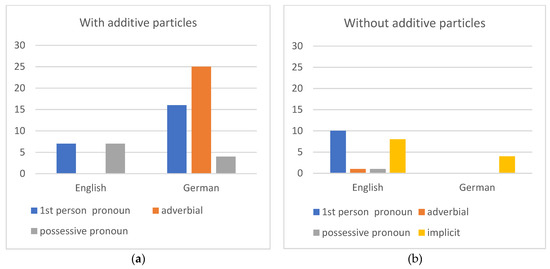

Additive particles are only possible with explicitly mentioned changing information (=their AC). In this case, the maintained information represents the common denominator that holds for the particle’s AC and its discourse alternative. Importantly, explicit expressions referring to the changed information always occur in combination with an additive particle in German, whereas they regularly appear without additive markers in English, in particular when the changing information is encoded by a first-person pronoun (Figure 6). Recall that implicit reference to the speaker/the picture is no option in utterances with additive particles since they would be lacking an associated constituent. Figure 6 thus also indicates that the German descriptions in our data always contain an additive particle as soon as an expression referring to the speaker/the speaker’s picture is present.

Figure 6.

Realisation of changing information unit (reference to speaker’s picture) in confirming descriptions with additive particles (a) and without additive particles (b), absolute numbers.

Let us consider these possibilities in turn. Adverbials of the type bei mir occur almost exclusively in German, either in sentences (18) or in elliptic utterances (19), and often in both, first and second move descriptions (18, 19). Example (20) is the only example attested in English.

| (18) | A: | da liegt bei mir ein tennisball. | |||||

| “there is a tennis ball in mine” | |||||||

| B: | alles klar, | der | liegt | [bei mir] | auch | unten (G.08–09) | |

| all right, | this-nom | lie-3sg | with me | also | below | ||

| “all right, it is at the bottom in mine too” | |||||||

| (19) | A: | daneben rechts ist bei mir ein tesafilmabroller | |||||

| “next to it to the right is in mine a sellotape dispenser” | |||||||

| B: | [bei mir]auch. (G.16–17) | ||||||

| “in mine too” | |||||||

| (20) | B: | how many objects are in your picture? | |||||

| A: | twelve | ||||||

| B: | okay, there are twelve objects in mine (E.13–14) | ||||||

Where German has no good equivalent for “same”, English has no good equivalent for bei mir. Like “same” in English, elliptical bei mir auch can function as an all-purpose confirmation of “what was said before” without targeting any particular information unit. It is not always clear to what exactly it refers, i.e., what the maintained and thus similar information is.

In verb containing confirmations, bei mir always occurs post-verbally, whereas the preverbal position is typically filled with a third person pronoun referring to the entity that the speakers talk about (18). Speaker B can thus anaphorically refer to the entity introduced by speaker A and make it the sentence initial aboutness topic of her own utterance. This might be a decisive advantage for hosting additive particles, as will become clear below.

The lack of a suitable adverbial encoding reference to the changing information forces speakers of English to devote the grammatical subject to this task. This leaves them with two possibilities to map the changing information onto the subject role: first person pronouns or possessives. Both occur with the same frequency in the English data (see Figure 6 above).

Using a possessive NP or pronoun (“my X”/”mine”) as a subject is an ideal solution, as it links both functions: The possessive refers to the topic (the entity talked about) and encodes reference to the current speaker at the same time. The two functions encoded separately in the German bei mir constructions (topical entity = subject pronoun; reference to the current speaker = bei mir adverbial; cf. (18)) are fused in the subject constituent when a possessive is used. With this construction, English SVO syntax allows speakers to use the entities as subjects and anaphoric discourse links in initial position and to simultaneously mark an additive relation between the two speakers/pictures. There are 12 possessives altogether in confirming descriptions. With only one exception, they co-occur with an additive particle in both German and English and the relevant utterances have a similar structure. The possessives appear in initial position in either sentence-like (21) or elliptical (22) utterances.10

| (21) | A: | and then a tea candle (..) that hasn’t been used? |

| B: | No, [mine] hasn’t been used either (E.22–23) | |

| (22) | B: | what colour is your teapot? |

| A: | yellow | |

| B: | yep, [mine] too (E.24–25) |

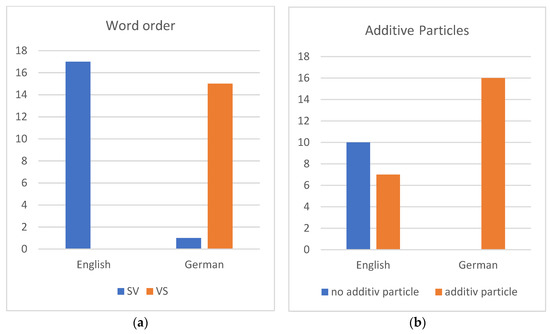

Additive descriptions with possessive subjects are, however, restricted to confirming the properties or the location of the relevant entities (21), (22). For the confirmation of the existence of a particular entity, speakers have to resort to first-person subject pronouns combined with the verb “have”. Reference to speaker and entity are no longer mapped onto the same syntactic constituent (subject) and the syntactic constraints of German (V2) and English (SVO) therefore have an impact on suitability of this structure for the integration of additive particles. Figure 7 shows that first person pronouns are invariably in initial position in English, whereas this is clearly the exception in German.11 More often than not English first-person descriptions are realised without additive particles, again in stark contrast to German.

Figure 7.

Descriptions with first person subject pronouns: Frequency of word order patterns (a) and additive particles (b), absolute numbers.

Due to German V2 syntax, speakers can place the direct object (NP or pronoun) in pre-verbal position, while the first-person subject pronoun occurs post-verbally (23). Instead of fusing reference to the entity and to the speaker in a possessive pronoun that functions as the particle’s associated constituent, German splits the two tasks up in a way similar to what we saw with the bei mir adverbials above. The expression referring to the entity is in initial position and functions as an anaphoric discourse link to what was said before. In the terms of Speyer (2008), these referents can be qualified as “Topic” (discourse-old, uniquely identifiable, talked about) and “Contrast” (belonging to a set of entities which is being evoked). The speakers’ choice to put the grammatical object referring to the entity in first position could be motivated by both properties, as “Topics” and “Contrasts” compete for first position and are not mutually exclusive (Speyer 2008, p. 283). The first-person pronoun, on the other hand, encodes the changing information, but is maximally downgraded at the same time. In Speyer’s (2010) terms, it is expressing the “Origo”, rather than the “Topic”. In our data, it occurs in the immediately post-verbal position (see Frey 2004) where it functions as the particle’s AC. English SVO syntax excludes this possibility. First person subject pronouns have to be placed pre-verbally, at the expense of the topical/contrastive discourse entity (24). In the initial position, this information unit does not seem to be an ideal AC for an additive particle, as speakers prefer to leave the additive relation unmarked in the majority of cases (25).

| (23) | A: | daneben kommt nochmal ein teelicht | ||||

| “next to it comes a tea candle” | ||||||

| B: | dasteelicht | hab | [ich] | auch (G.03–20) | ||

| the tea-candle-acc | have-1sg | pro-1sg | too | |||

| “I’ve got a tea candle too” | ||||||

| (24) | A: | bottom left I’ve got a coffee cup | ||||

| B: | [I]’ve got a coffee cup as well (E.20-C) | |||||

| (25) | A: | in the middle of that column is a plastic clear tape dispenser | ||||

| B: | yeah I’ve got that (E.22–23) | |||||

It seems, thus, that the word order constraints of German and English play a major role in determining the information flow in confirming descriptions. Whereas possessive subjects are an ideal solution for encoding the changing information unit in both languages (restricted, however, to confirming properties/locations), first-person subject pronouns encoding the changing discourse alternative are bound to the initial position in English, but not in German. German V2 word order provides speakers with a multifunctional initial position that can host the topic and dissociate it from the expression referring to the current speaker. This is not easily possible in English (SVO), where the subject has to perform “triple duty” (Los and Starren 2012). Additive particles applied faute de mieux to an initial subject (24) might highlight the changing information more than is warranted in the dialogue task, where a non-contrastive addition of information about the two pictures is expected. Note that there is not a single occurrence of auch pre-posed to its AC in German (#auch [ich] habe eine gelbe teekanne; #eine gelbe teekanne habe auch [ich]). Pre-posed additive particles associate with a focused AC that would lead to an even stronger contrastive relation with the relevant discourse alternative.

German V2 syntax allows for a division of labour that is favouring additive linking. Speakers can place the grammatical subject encoding the changing information unit further to the right. In its immediately post-verbal position, the first-person subject pronoun functions as the particle’s AC while being backgrounded at the same time. The changing information unit is thus related to a discourse alternative without attracting any emphasis at all. The initial expression referring to the topical entity, on the other hand, establishes an anaphoric coherence relation between the second move confirmation and the preceding first move description where the entity was introduced by the interlocutor.12 There are only two additive utterances in German in which the AC is in pre-verbal position.

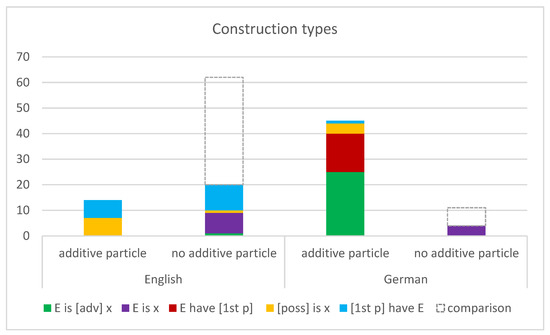

Figure 8 summarizes the findings.

Figure 8.

Frequency of the five construction types identified in confirming descriptions, absolute numbers. Square brackets in the structures indicate the position of the expressions encoding reference to the speaker (“bei mir”, “I”, “mine/my x”) that can be construed as the AC of an additive particle if there is one.

In principle, speakers have the following possibilities to confirm the properties of an entity: A possessive pronoun or NP referring to the entity is used in initial position ([poss] is x). It functions as an additive particle’s AC and an additive link is established between the relevant entities on both pictures. This works for both languages. Alternatively, some other expression referring to the entity can be combined with a bei mir adverbial and an additive particle (E is [adv] x). Since there is no good English equivalent to bei mir, this solution is only available in German. Yet another possibility is not to refer to the speaker at all (E is x). This avoids creating an unintended contrast. Without reference to the changing information, the structure excludes additive particles. This solution is more frequent in English than in German.

When confirming the existence of an entity, a subject pronoun referring to the speaker plus the verb have is the preferred realization in both languages. The reference of the 1st person pronouns is the only changing information (speaker A vs. speaker B) and thus a potential locus of contrast. English subject pronouns obligatorily occupy the first position ([1st p] have E) whereas German subject pronouns occur post-verbally in the vast majority of the cases (E have [1st p]). As shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, the English variant occurs with or without additive particle, and the second possibility is slightly more frequent. The German variant, however, always contains an additive particle. The abovementioned differences in the languages’ lexical repertoire and their syntactic properties might explain why speakers of English leave a considerable amount of their confirming descriptions unmarked for the additive relation between the changing information unit and its discourse alternative and why they frequently resort to confirming comparisons (“I have the same”) instead.

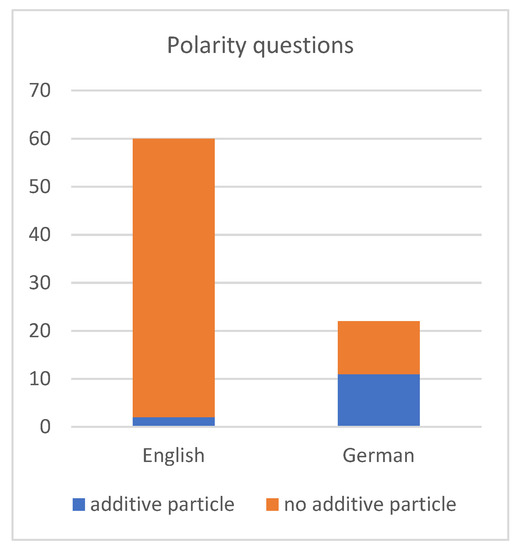

3.4. Polarity Questions

This final section completes the picture by investigating additive particles in first move polarity questions. Targeting speaker B’s picture, these questions contain a hidden description of speaker A’s picture that has not been stated independently before. Consider (26) below: Having a brown cardboard tube on his picture is the only motivation that A can have for asking this question.

Whenever polarity questions contain an additive particle, an expression referring to speaker B or her picture (second person pronoun or bei dir adverbial) functions as the particle’s AC. The questions behave just like the confirming descriptions in this respect, with the difference that the presupposition has not been asserted in a preceding utterance.

| (26) | Have [you] got a brown cardboard tube as well? (E.15–16) |

| (27) | Ist der apfel [bei dir]auch oben rechts? (G.12–13) |

| “Is the apple in yours also top right?” |

There is a big difference concerning the overall frequency of polarity questions in English and German (Figure 9). This might be an artefact of coding, since only polarity questions with a (verb-initial) question syntax or ellipses with a raising contour and containing second person pronouns (you/du) or bei dir adverbials were considered. A relatively high number of German utterances with declarative syntax and a rising intonation were excluded from this analysis, as they could not be unambiguously distinguished from descriptive first move statements with a rising intonation contour indicating continuation (cf. Petrone and Niebuhr 2014).

Figure 9.

Frequency of additive particles in polarity questions, absolute numbers.

These overall frequency differences do not prevent us from noting that half of the polarity questions produced by speakers of German contain additive particles, whereas English speakers hardly use them at all. A Pearson’s chi-square-test revealed a highly significant association between language and particle use in polarity questions: X2(1) = 26.27, p < 0.001. Additive particles are much more frequent in German than in English, but less frequent than in German confirming descriptions (Figure 1). They are compulsory in verbless ellipses (bei dir auch? “in yours as well?”), but content wise, they are in principle as redundant in polarity questions as in confirming descriptions.

In a particle-prone language like German, their absence might indicate, however, that a polarity question does not contain a hidden description of the current speaker’s own picture (presupposition). Quite a few of the German polarity questions without particles target properties that are actually different in both pictures. This is something the speaker cannot normally foresee in this task, but there are cases in which the questions follow an earlier description by the interlocutor that deviates from what the current speaker sees on his picture. Consider (28) and (29), for example. The current speaker’s picture shows a toilet roll without paper, whereas the other picture shows a toilet roll with paper (see Supplementary Materials). The interlocutor’s unspecific description of just “a toilet roll” elicits a quest for clarification in the form of a polarity question from the current speaker.

| (28) | A: | eine klopapierrolle rechts daneben |

| “a toilet roll to the right of it” | ||

| B: | ist da noch klopapier dran? (G.03–20) | |

| “is there still loo paper left?” | ||

| (29) | ist die rolle bei dir voll? (G.01–02) | |

| “is the roll in yours full?” | ||

If additive particles are quasi compulsory when the relevant presupposition is satisfied, their absence becomes meaningful, too. As was shown above for confirming descriptions and polarity questions, this is the case for German, but not for English.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study found large frequency differences between German and English with respect to additive particles produced in otherwise highly comparable discourse moves (confirming descriptions and polarity questions) in picture comparison dialogues. Such differences are not predicted by semantic and pragmatic accounts assuming that the use of additive particles is guided by language independent principles. In particular, presuppositions that are explicitly expressed in discourse should induce an “obligatoriness of too and other additives” (Amsili and Beyssade 2010) regulating the relation between information units and their discourse alternatives. Exactly these kinds of contexts were analysed in the present paper, with the finding that additive particles were clearly “more obligatory” in German than in English. The relevance of these principles is diluted by a number of language specific lexical and syntactic constraints.

The availability of suitable adverbials like “same” (English) or bei mir (German) seem to be responsible for a good deal of the speakers’ decisions in favour of either confirming comparisons (no additive particles possible) or confirming descriptions (many additive particles with the bei mir adverbials as their AC). In addition to these lexical reasons, syntactic ones are relevant for the structure of the descriptions and the ease with which additive discourse relations can be marked.

Descriptions often contain 1st person subject pronouns, in particular, when it is the existence (“I have x”) and not some property of an entity that is to be confirmed. In English (SVO), subject pronouns in initial position are the unmarked default. In German (V2), the same surface order is the result of a choice and thus, “informative”. Therefore, no contrast between the referents of the unmarked English subject pronouns has to be healed and an “anti-contrastivity marker” (Schmitz et al. 2018) is not compulsory. On the contrary, construing an initial subject pronoun as a particle’s AC might even strengthen the unintended interpretation of the interlocutors as opposite alternatives. Research shows that scope particles make the relation between discourse alternatives more salient and recognizable (Gotzner et al. 2013). The very particle that contributes to the conversion of an unmarked referent into a salient discourse alternative is then needed to qualify the relation between the alternatives as additive rather than contrastive. In a way, inserting an additive particle makes the situation worse and better at the same time. This paradoxical situation might be reflected in the English speakers’ unclear preferences.

Due to its V2 syntax, no such problem arises in German. Speakers simply avoid subject pronouns in first position in their confirmations.13 Instead, they topicalize reference to the entities talked about and make these referents more salient than the comparison or contrast between the interlocutors. The 1st person subject pronouns are downgraded to the immediately post-verbal position where they are barely “visible” and can be used to tighten discourse cohesion without collateral damage. The excessive use of additive particles with the downgraded subject pronouns as their ACs might thus serve the expression of agreement and foster discourse alignment, rather than suppressing unintended contrasts (cf. the “anti-contrastivity marker” proposed in Schmitz et al. 2018).

Next to the favourable word order, the high frequency of additive particles in German might also be due to the fact that the particle itself carries focal stress14 and highlights the affirmative polarity of the answer. What is at issue in a second move confirmation is the polarity of the claim (there are also second move rejections). The contribution of the particle comes close to so-called verum focus, i.e., a focal accent on the finite verb (Höhle 1992). Whereas verum focus typically expresses a contrastive focus on polarity (e.g., affirmation rejecting negation), the stressed particles rather resemble information focus. In the picture description dialogues, polarity is at issue, but it is not contrastive in a confirmation, where affirmation is maintained from the interlocutors’ preceding description. The particle could thus be needed to generate an intonation contour without misleading focal accents on other constituents. It is an open question, to what extent this contributes to the quasi-obligatoriness of German additive particles in the type of utterances analysed here. If intonation plays a role, it can again only be a language-specific one. There is no similar problem in English, where speakers seem to find utterances without particles perfectly felicitous in the given context.

Taken together, these language-specific differences might explain why speakers of German always use additive particles when reference to the speaker is overtly encoded (possessive NP or pronoun, bei mir adverbial, 1st person subject pronoun). Possessive NPs or pronouns fuse reference to the aboutness topic (the entity) and the speaker. The other two options encode reference to the speaker in isolation, but this is achieved without any highlighting. Speakers of English, on the other hand, leave nearly 60% of their confirming descriptions unmarked for the additive relation between the changing information unit and its discourse alternative. As there is no suitable adverbial of the bei mir kind, 1st person subject pronouns are the only option for the isolated reference to the speaker that is needed for confirming the existence of entities. Given that subject pronouns are bound to the initial position, making them the AC of some particle and thus, initiating the search for a discourse alternative (Spalek and Zeldes 2017) means using an additive particle to heal a problem that would not have arisen without the particle. English speakers thus hesitate between SVO utterances with and without particles and they prefer comparisons to descriptions.

To sum up: In English, the default mapping of information units on syntactic functions in conjunction with SVO word order leads to a structure in which subject, initial (topic) position and the particle’s associated constituent necessarily coincide (“I have a yellow teapot”). If an additive particle were used (“[I] have a yellow teapot, too”), it would make the relation to the discourse alternative more prominent than warranted by the dialogue task. Speakers of English tend to leave this relation unmarked or resort to alternative constructions instead (“I have the same”). The V2 syntax of German, on the other hand, allows for a dissociation of discourse topic and added constituent. Speakers can topicalize reference to the entity, putting it in the forefront of the interlocutor’s attention, and relate the changing information (speaker) to its discourse alternative in a non-contrastive way (OVS surface order: Die Teekanne habe ich auch).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D. and M.S.; methodology, C.D. and M.S.; data analysis, C.D. and M.S.; writing, C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is archived at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Germany and Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In the following I will use male pronouns for speaker A and female pronouns for speaker B. |

| 2 | Note that additive particles trigger presuppositions whereas restrictive focus particles are part of the assertion proper. |

| 3 | Individual dialogues from the picture description corpus are identified by capitals (E for English, G for German) and numbers indicating the speaker dyad (here: dyad with participants 03 and 04). Examples without such indications are not drawn from the corpus but made up for illustration purposes. |

| 4 | Interlinear glosses will be provided for later examples where word order matters. |

| 5 | The setup was thus different from the procedure known from map tasks, for example, where participants are assigned the role of a “giver” and a “follower” and keep them throughout the task (Anderson et al. 1991). |

| 6 | Some dyads started by negotiating where (on the picture) to start the description; in a few other cases one speaker first listed the twelve entities without specifying their location or properties, but this was always followed by a phase during which each entity was considered individually. |

| 7 | The prepositional phrases bei mir and bei dir literally translate as ‘with me’ and ‘with you’. Whereas they are highly frequent in the German data, there is only a single occurernce of this type in English. A informs B that there are twelve entities on his picture and B replies There are twelve objects in mine (E.13–14). We will therefore use in mine/in yours in the translations. |

| 8 | Confirming descriptions can be holistic (signalling approval concerning an entity, its properties and location) or restricted to only the entity (I’ve got a pear but it is somewhere else; There is a toilet role in the middle, but it is empty). |

| 9 | Speakers do say genau (‘exactly’). This adverb (like its English translation), does however not mark sameness, but rather the degree of sameness and was therefore disregarded. |

| 10 | There are two cases of inversion (“neither has mine”) with negative particles in English. |

| 11 | Note that elliptical cases were treated as exhibiting the wordorder predominant in the respective language. There were five elliptical utterances of the type ich auch (‘me too’) in German. They were added to the VS order that was attested with the 10 out of 11 verb-containing utterances. The single elliptical utterance (me too) in English was added to the SV pattern. |

| 12 | In German first move descriptions, the initial position is typically filled with a locative expression, whereas the NP referring to the newly introduced entity is placed post-verbally. |

| 13 | From the three possibilities to integrate an additive particle with the subject pronoun as its AC that were illustrated in example (2) in the introduction, only one was actually used for confirming the existence of an entity on the speaker’s picture, and it is the one with the word order that is impossible in English (OVS). |

| 14 | The choice between stressed and unstressed variants of German auch correlates with the particle’s position relative to its AC (Reimer and Dimroth 2021). |

References

- Amsili, Pascale, and Claire Beyssade. 2010. Obligatory presupposition in discourse. In Constraints in Discourse, Pragmatics and Beyond. Edited by Peter Kühnlein, Anton Benz and Candace L. Sidner. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 2, pp. 105–23. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Anne H., Miles Bader, Ellen Gurman Bard, Elizabeth Boyle, Gwyneth Doherty, Simon Garrod, Stephen Isard, Jacqueline Kowtko, Jan McAllister, Jim Miller, and et al. 1991. The Hcrc Map Task Corpus. Language and Speech 34: 351–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzo, Sandra, and Christine Dimroth. 2015. Additive particles in Romance and Germanic languages: Are they really similar? Linguistik Online 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büring, Daniel. 2016. (Contrastive) Topic. In The Oxford Handbook of Information Structure. Edited by Caroline Féry and Shinichiro Ishihara. Oxford: OUP, pp. 64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine. 2004. Fokuspartikeln und Informationsgliederung im Deutschen. Tübingen: Stauffenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Dimroth, Christine, Cecilia Andorno, Sandra Benazzo, and Josje Verhagen. 2010. Given claims about new topics. How Romance and Germanic speakers link changed and maintained information in narrative discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 42: 3328–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, Regine, and Manuela Fränkel. 2012. Particles, Maximize Presupposition and discourse management. Lingua 122: 1801–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Werner. 2004. A medial topic position for German. Linguistische Berichte 198: 153–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gotzner, Nicole, Katharina Spalek, and Isabell Wartenburger. 2013. How pitch accents and focus particles affect the recognition of contextual alternatives. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Edited by Markus Knauff, Michael Pauen, Nathalie Sebanz and Ipke Wachsmuth. Austin: Cognitive Science Society, pp. 2434–39. [Google Scholar]

- Höhle, Tilman. 1992. Über Verum-Fokus im Deutschen. In Informationsstruktur und Grammatik. Edited by Joachim Jacobs. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 112–41. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, Manfred. 1998. Additive particles under stress. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 8: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, Bettelou, and Marianne Starren. 2012. A typological switch in early Modern English—And the beginning of one in Dutch? Leuvense Bijdragen—Leuven Contributions in Linguistics and Philology 98: 98–126. [Google Scholar]

- Petrone, Caterina, and Oliver Niebuhr. 2014. On the intonation of German intonation questions: The role of the prenuclear region. Language and Speech 57: 108–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimer, Laura, and Christine Dimroth. 2021. Added alternatives in spoken interaction: A corpus study on German auch. Languages 6: 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæbø, Kjell Johan. 2004. Conversational contrast and conventional parallel: Topic implicatures and additive presuppositions. Journal of Semantics 21: 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, Tijn, Lotte Hogeweg, and Helen de Hoop. 2018. The use of the Dutch additive particle ook ‘too’ to avoid contrast. Tijdschrift voor Nederlandse Taal- en Letterkunde 134: 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Spalek, Katharina, and Amir Zeldes. 2017. Converging evidence for the relevance of alternative sets: Data from NPs with focus sensitive particles in German. Language and Cognition 9: 24–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Speyer, Augustin. 2008. German Vorfeld-filling as constraint interaction. In Constraints in Discourse. Edited by Anton Benz and Peter Kühnlein. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 267–90. [Google Scholar]

- Speyer, Augustin. 2010. Filling the German vorfeld in written and spoken discourse. In Discourse in Interaction. Edited by Sanna-Kaisa Tanskanen, Marja-Liisa Helasvuo, Marjut Johansson and Mia Raitaniemi. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 263–90. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).