Abstract

Authority is both a pragmatic condition of much public discourse and a form of argumentative appeal routinely used in it. The goal of this contribution is to propose a new account of challenging authority in argumentative discourse that benefits from the interplay of the resources of recent speech act theory and argumentation theory. Going beyond standard approaches of the two disciplines, the paper analyzes nuanced forms of establishing and, especially, challenging discourse-related authority. Can Donald Trump advise his own scientific advisors on potential COVID-19 treatments? Addressing questions like this, the paper identifies various paradoxes of authority and the forms of authority discussed in the literature. It then distinguishes between argument from authority (or expert opinion) and argument to authority (or expert opinion) and argues that this rearranged structure mutually benefits the pragmatic account of speech act theory and the schematic account of argumentation theory in the task of better understanding and critiquing discourses such as Trump’s.

1. Introduction

As early as in his Rhetoric, Aristotle (2007, p. 39, 1356a) claimed that ethos, the character of the speaker, is “the most authoritative form of persuasion”. In turn, contemporary speech act theory demonstrates how for virtually all speech acts to be felicitously performed, the speaker needs to be in a position of an epistemic (theoretical) or deontic (practical) authority (Austin 1962; Searle 2010).1 However, while fundamental in understanding how authority functions in discourse, these classic approaches have a specific, and somewhat limited, focus. Aristotle looked exclusively into the speaker’s “entechnic” authority, which was established explicitly in discourse. By contrast, speech act theorists typically draw on what Aristotle would call an “atechnic” authority, namely one that is pre-established and formally recognized in terms of the “deontic powers” of speakers.

In this paper, I turn instead to more nuanced forms of establishing and, especially, challenging discourse-related authority. This is in line with recent work in speech act theory, which has defended a subtler account of various “authoritative illocutions” (Langton 1993) extending beyond institutional contexts to common speech acts, such as ranking someone or something. Inspired by insights from Austin (1962) and Lewis (1979), this work highlights how authority can be negotiated on the fly as conversation develops. In its turn, argumentation theory has successfully examined the details of various forms of argument from authority, and of argument from expert opinion in particular.

The goal of this contribution is to propose a new account of challenging authority in argumentative discourse that benefits from the interplay of the resources of recent speech act theory and argumentation theory. The guiding question is, accordingly: In which ways can the authority of the speaker be challenged for argumentative purposes? To address this question, I first present, in Section 2, an interesting case of (ab)using authority in public discourse: an April 2020 press conference during which Donald Trump remarked that UV light and bleach can eliminate coronavirus from the human body. Is there any authority involved in his comments and, if so, how can it be challenged? This case reveals various difficulties, indeed paradoxes, of authority and expertise in public discourse, something I turn to in Section 3. Here, the varieties of authority discussed in the literature are presented as possible ways out of the paradoxes. Further, in Section 4, I first briefly recount how argument from authority is treated in argumentation theory as one of the argument schemes with associated critical questions aimed at testing its quality. I then present my own proposal that distinguishes between argument from authority (or expert opinion) and argument to authority (or expert opinion). Finally, in Section 5, I show how this rearranged structure mutually benefits the pragmatic account of speech act theory and the schematic account of argumentation theory in the task of better understanding and critiquing discourses such as Trump’s.

2. Can a President Advise His Advisors?

Donald Trump’s presidency has been a continuous source of inspiration for research interested in the tricky, and often outright harmful, pragmatics of public argument (Beaver and Stanley 2019; Herman 2022; Herman and Oswald 2021; Jacobs et al. 2022; Khoo 2017, 2021; Neville-Shepard 2019; Ryan Kelly 2020; Saul 2017, 2021; Tirrell 2017). One of the presidency’s fascinating twists came on 23 April 2020, during one of the daily press conferences Trump’s White House organized in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier that day, the US government’s COVID task force met to discuss the preliminary scientific data on the impact of various conditions (light, temperature, humidity, and disinfectants) on the persistence of the new coronavirus on surfaces and airborne aerosols. Trump did not attend that meeting; instead, he was later briefed about it by his aides. However, “it was clear to some aides that he hadn’t processed all the details before he left to speak to the press” (McGraw and Stein 2021, online). The memorable moment of that conference came when Trump spoke after William N. Bryan, the acting undersecretary for science and technology at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Bryan briefly presented some of the tentative findings discussed by the task force on how sun’s UV light and some disinfectants could quickly and effectively eliminate the coronavirus on surfaces such as counters or door handles. Trump then took the floor to say the following:

THE PRESIDENT: Thank you very much. So I asked Bill a question that probably some of you are thinking of, if you’re totally into that world, which I find to be very interesting. So, supposing we hit the body with a tremendous—whether it’s ultraviolet or just very powerful light—and I think you said that that hasn’t been checked, but you’re going to test it. And then I said, supposing you brought the light inside the body, which you can do either through the skin or in some other way, and I think you said you’re going to test that too. It sounds interesting.

ACTING UNDERSECRETARY BRYAN: We’ll get to the right folks who could.

THE PRESIDENT: Right. And then I see the disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute. One minute. And is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning. Because you see it gets in the lungs and it does a tremendous number on the lungs. So it would be interesting to check that. So, that, you’re going to have to use medical doctors with. But it sounds—it sounds interesting to me.

So we’ll see. But the whole concept of the light, the way it kills it in one minute, that’s—that’s pretty powerful.2

There has been an immediate backlash against Trump’s remarks, widely described as “crazy”, “surreal”, or “shocking” (McGraw and Stein 2021, online). One line of attack was straightforwardly factual, based on the not-so-hard-to-verify observation that Trump parted his way with medical truth. In the words of science writer, David Robert Grimes (holder of a PhD in medical ultraviolet radiation): “No, you cannot inject UV light into your body to cure #COVID19—neither biology or physics work that way.”3 Another group of critical responses focused instead on the possible harm caused by Trump’s words, especially if some of the president’s listeners seriously considered the idea of injecting, ingesting, or inhaling disinfectant. Alarmed by the hazards of such plausible reactions, various experts (toxicologists, pulmonologists, physicians, and public health officials) called this idea “irresponsible”, “extremely dangerous”, and “frightening”: “There’s absolutely no circumstance in which that’s appropriate, and it can cause death and very adverse outcomes.”4

Trump’s comments were thus criticized for being incorrect and potentially harmful. These two forms of attack can be precisely grasped within Austin’s (1962) speech act theory. In his seminal work, Austin posited that “the total speech act in the total speech situation” (1962, p. 147) consists of three analytically distinguishable aspects: locution (the performance of an act of saying something with a certain meaning, that is, with a certain sense and reference: She said “x”), illocution (the performance of an act in saying something, the conventional force or function for which locution is used: She argued that x), and perlocution (the performance of an act by saying something, that is, “consequential effects upon the feelings, thoughts, or actions of the audience, or of the speaker, or of other persons”: She convinced me that x) (Austin 1962, Lectures VIII-IX; see Sbisà 2013, pp. 230–233). Criticizing Trump for being at odds with scientific knowledge amounts, most directly, to rejecting the locutionary content of his comments.5 Challenging his remarks for being potentially harmful amounts to objecting to their pernicious perlocutionary consequences—i.e., “upon the feelings, thoughts, or actions of the audience”. In this way, health experts and commentators engaged openly in public argumentation against Trump’s comments. They did so by exploring the disagreement space—“the entire complex of reconstructible commitments […], a structured set of opportunities for argument” (Jackson 1992, p. 261)—in its two pragmatically salient ways. They pointed out falsehoods of his locutions—injecting UV light into the body is not an interesting option to test, for scientists already know it does not work—and their detrimental perlocutionary effects.

Conspicuously absent from the larger public controversy was attention to the illocutionary force of Trump’s remarks: the obvious but missing link between his locutions and perlocutions. The central question of the Austinian, speech act-based pragmatics—what did he do with his words?—has remained unasked, even though it has been unreflectively answered, one way or another. Yet, by concentrating on the question of illocutionary force one can inquire into a distinct, and often crucial, way of challenging Trump’s, and any other similar, discourse. Since this is precisely the focus of this paper, we then need to ask: So, what did Trump do?

Above, I have been very circumspect in denoting Trump’s words simply as “words”, “remarks”, or “comments”—otherwise, I would have given off what is to be investigated. Various media reporting and commenting on the event have been more direct about characterizing his speech acts as “musings” (The Guardian), “wonderings”, or simply “assertions” used while Trump was “eagerly theorizing about treatments”; indeed, Trump resorted to “a science administrator to back up his assertions” (The New York Times).6 All these illocutionary acts belong to a broad class of “assertive” or “representative” speech acts (Searle 1975a; cf. Green 2009; Witek 2021b). Other commentators have instead identified the president’s comments in terms of “suggesting”, “recommending”, or “advising” to test bleach or UV light as a coronavirus therapy. These belong to a notably distinct class of speech acts, namely that of “directives” (Searle 1975a).7 In contrast to assertives, which sit firmly in the realm of theoretical (epistemic) reasoning, directives such as proposals and pieces of advice are characteristic conclusions of practical arguments (Corredor 2020; Gauthier 1963; Lewiński 2021b). A speaker considers various means to be taken under given circumstances—vis-à-vis the goal to be achieved and the values to be observed—and concludes by means of, among other things, suggesting, recommending, or advising that X should be done. Significantly for the context under discussion, standard medical procedures inevitably combine the two classes of speech acts and, more broadly, epistemic and practical authority. The expert assertions making up a medical diagnosis, an exercise of epistemic authority, form the basis for practical reasoning that issues in “medical” or “health advice”, which is an exercise of practical authority (Bigi 2018; Van Poppel 2019).

Donald Trump, however, is not a medical doctor and this was not a medical consultation. Still, it was an official press conference organized to report and discuss preliminary scientific data on possible COVID-19 treatments. Is there any sense in which Trump could be taken to issue health advice to his own advisors or even to American citizens at large? The details of the communicative situation, and a better grasp of the authority conditions behind speech acts, are needed to answer this question.

The White House press briefing was a par excellence polylogical communicative situation, one that involves a complex constellation of speakers and hearers (Lewiński 2021a, 2021c). In his remarks, Trump comments on the results of medical studies his scientific advisors discussed earlier that day. He is directly addressing Bryan (and later also Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator present at the briefing) in what can be understood as interrogative mood.8 Arguably, the surface grammar of Trump’s expressions is that of a declarative mood (hence some of the commentators rightly reported his speech in terms of “assertions”); he basically states or reports things, including his own discourse (“I asked”, “I said”). Nonetheless, the prosody of the spoken discourse, Trump’s gestures (inquisitive head nods, widening eyes), and confirmation-seeking pauses indicate an overall interrogative construction, not unlike in tag questions (even if the “Isn’t it [the case]?” bit is merely implicit here). There is a curious progression in Trump’s discourse. Ostensibly, at first he is merely reporting on an exchange he has just had with his science advisors: “So I asked Bill a question […] and I think you [Bill] said that […] And then I said […]” In the public context of the press conference, he is now seeking an on-record confirmation of the “very interesting” idea of testing light as a coronavirus therapy, a confirmation which Bill Bryan eagerly provides (“We’ll get to the right folks who could [test it].”); however, it has been clear to most anyone that Trump is not merely reporting on “ask[ing] Bill a question”, contrary to his disingenuous disclaimer right at the beginning of the fragment. The second part, right after Bryan’s keen interjection, takes on a decidedly more prospective, rather than retrospective, stance:

Here, Trump abandons the reported speech format and directly presents his assessment of the situation (“it gets in the lungs and it does a tremendous number on the lungs”), followed by an evaluative judgment that “it would be interesting to check that.” It is unclear, however, whether this in any way continues his report on the prior conversation with advisors or rather directly presents the president’s independent “talent” (see below).9 This strategic ambiguity at the illocutionary level (see Lewiński 2021a) is part of the potential manipulation and lets Trump plausibly deny any sincere commitment to either the assertoric (“it does”) or directive (“check that”) force of his words. Yet, these are precisely the commitments critical commentators took him to task for. Given the official capacity he is speaking in, he can be reasonably taken to be requesting, advising, or even commanding his administration’s officials that some potential treatments be “tested” or “checked.”10 Such an official request presupposes that such treatments are worthy of serious scientific testing, something Trump directly reinforces by labeling them “very interesting” and “pretty powerful.” Noticeably, then, in contrast to the earlier case of the antimalarial drug, hydroxychloroquine, Trump didn’t openly advocate, let alone mandate, the use of bleach or UV light to cure the new coronavirus. All the same, he clearly suggested—in one of the possible illocutionary readings of the verb “to suggest”11—that using them is a potentially effective way of treating COVID-19.THE PRESIDENT: Right. And then I see the disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute. One minute. And is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning. Because you see it gets in the lungs and it does a tremendous number on the lungs. So it would be interesting to check that. So, that, you’re going to have to use medical doctors with. But it sounds—it sounds interesting to me.

All this happened in the presence of other White House staff (including the vice president, Mike Pence), accredited journalists, and American, indeed global, audiences. The already complex illocutionary picture gets even more complex. Trump might be intentionally and conventionally performing plural illocutionary acts in his intervention (see Lewiński 2021a, 2021c). On the one hand, by addressing his officials he seems to be clearly directing them via request, advice, or even command, once the veil of reported speech drops. On the other hand, simultaneously addressing American and global audiences, Trump can be taken to suggest, recommend, or advise the general public, via the journalists present, to “try this at home”; in his words: “to check” how a “disinfectant […] injection […] does a tremendous number on the lungs.” Again, any such illocutionary intention can be, and has been (see below), disavowed by Trump. If he knew speech act theory, he could say that “trying this at home” can at most be a mere distal perlocutionary effect of his words on some reckless people, an effect for which he bears no responsibility. Whether the harm was potential and perlocutionary, or direct and illocutionary, some institutional actors felt compelled to avert it. This included Reckitt Benckiser, the manufacturer of globally distributed disinfectant brands, who issued an official statement. Again, the reported speech (“RB has been asked whether…”) complicates interpretation here, but it is clear some people took up Trump’s remarks, under whichever illocutionary force, as legitimizing the use of disinfectants as a potential coronavirus treatment.

Due to recent speculation and social media activity, RB (the makers of Lysol and Dettol) has been asked whether internal administration of disinfectants may be appropriate for investigation or use as a treatment for coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

As a global leader in health and hygiene products, we must be clear that under no circumstance should our disinfectant products be administered into the human body (through injection, ingestion or any other route). As with all products, our disinfectant and hygiene products should only be used as intended and in line with usage guidelines. Please read the label and safety information. (https://www.rb.com/media/news/2020/april/improper-use-of-disinfectants/ accessed on 8 Feburary 2022)

One key feature in answering questions of the illocutionary force of someone’s speech acts are the authority relations implied in the felicity conditions for such speech acts. A key idea behind speech act theory, as originally formulated by J. L. Austin (1962), was that for various important speech acts to be “felicitously” performed, the speaker needs to be in a position of authority: only a judge can announce a verdict and only a general can command an army. Early speech act theory thus paid special attention to institutional forms of authority that are constitutive of various exercitive and verdictive (Austin 1962) or directive and declarative (Searle 1969, 1975a) speech acts. More recently, philosophers have defended a more nuanced account of such “authoritative illocutions” (Langton 1993). Many of the common speech acts, from entitled requests to harmful rankings typical of pornography and hate speech, similarly appeal to a speaker’s authority that can often be passively accommodated, thus giving the speech its authoritative force (e.g., Langton 1993, 2015, 2018a, 2018b; Bianchi 2019; Kukla 2014; Lance and Kukla 2013; Maitra 2012; McDonald 2021; McGowan 2019; Sbisà 2019; Witek 2013, 2021a). A speaker’s authority can be used for good or ill; in the latter case, speech can constitute and cause harm precisely because it is authoritative. Harmful speech would neither constitute subordination of its targets nor cause their distress (etc.), were it not for the pre-existing or accommodated authority of the speaker. A practical task is to devise various ways of blocking (Langton 2018a), defying (Lance and Kukla 2013), or otherwise undoing (Caponetto 2020) the force of such speech.

In our case, since this was the President of the United States speaking, Trump’s “questions” were hardly ever treated as just questions or mere “musings” or “wonderings.” Most commentators quite directly responded to what they took up as public “recommendation” or “advice.” The disinfectant producer, Reckitt Benckiser, might even be playing the game of taking Trump seriously by responding as if he was officially committed to recommending that “internal administration of disinfectants may be appropriate for investigation or use as a treatment for coronavirus.” In this context, it is startling to see that, contrary to most critics’ focus on the locutionary error and perlocutionary harm, Trump himself skillfully manages the illocutionary indirectness and ambiguity of his words. Indeed, he was uncharacteristically circumspect about the content of his words. Once questioned on-the-spot by the journalists attending the press conference over the possibly dangerous consequences of his remarks, he responded, “I would like you to speak to the medical doctors to see if there’s any way that you can apply light and heat to cure. Maybe you can, maybe you can’t. Again, I say, maybe you can, maybe you can’t. I’m not a doctor.” However, when further pressed by a Washington Post reporter, he retorted, “I’m the president and you’re fake news … I’m just here to present talent, I’m here to present ideas.”12 The following day, when again asked about his discourse, Trump doubled down on this by claiming, “I was asking sarcastically to reporters just like you to see what would happen.”13 That is to say, while he was quite evasive about—even hedging—the content of his words, Trump was very clear on the authority conditions behind his discourse. In his words, he is “not a doctor” to adjudicate and advise on medical details (although, of course, he can significantly influence health policies in the US), but he is the POTUS and in a position “to present talent” and “ideas”—both his own and his scientific advisors’, one might surmise. By the superior powers of the president who summons media to listen to him, he can also fool the “fake news” journalists and bleach producers by sarcastically asking questions “to see what would happen.”

This is all about the illocutionary force of what happened, and especially about POTUS’s entitlement to perform certain speech acts that others, such as journalists and even his scientific advisors present at the meeting, cannot perform (at least with the same illocutionary force). Once this becomes the focus of attention, the more nuanced questions that link pragmatic and argumentative analysis emerge. Given that authority is both a pragmatic condition of much public discourse and a form of argumentative appeal routinely used in it, one key question is how these two perspectives reinforce each other in the task of understanding how authority can be challenged. Such understanding will let us see in more detail how questionable public statements, such as Trump’s, can be criticized beyond their locutionary content and perlocutionary harm.

3. Paradoxes of Authority

Authority is an unlikely hero both within the tradition of argumentation theory and speech act theory. It constrains our free intellectual enterprise and fetters public argument. Moreover, when it enables various forms of communication—as is the case with Aristotle’s successful persuasion—these can be bad or insidious forms. Yet, we so badly need it that it is here with us to stay and to be recognized, as there is no prospect of wiping it entirely from argumentation and communication. This predicament engenders various paradoxes of authority.

The first of the paradoxes is well-recognized within argumentation theory (Bachman 1995; Goldman 2001; Goodwin 1998; Jackson 2008; Willard 1990). On the one hand, the argument from authority becomes the fallacious argumentum ad verecundiam, as it stifles the independent examination of reasons, thus endangering one of the basic principles of rationality. Indeed, if autonomous, unfettered, and unbiased weighing of reasons is what rationality consists of, then reliance on external authority with its prêt-à-porter judgements undercuts reason. Blind obedience to religious authority of any creed and epoch is a specimen of the grave offence to reason committed by appeals to authority.14 On the other hand, in the complex world we live in, there is only so much we can learn via direct, first-hand perceptual experience and individual reflection. A vast majority of our knowledge is second-hand knowledge, derived from the testimony of others in the position to know—i.e., eyewitnesses, experts, educators, public authorities, etc. (Lackey 2008). We simply cannot reason without arguments from epistemic authority, be them arguments from expert opinion, from testimony, or otherwise from the position to know. Hence the first paradox: authority both appears to be an unreasonable form of argumentation and its very condition of possibility.

The second paradox has been identified in the speech act literature as “the authority problem” (Bianchi 2019; Langton 2018b; Maitra 2012). Some form of authority is needed for a successful performance of many, if not all, speech acts.15 Institutional performatives are an obvious case here: only “a proper person” under “appropriate circumstances” can name a ship or baptize a baby (Austin 1962; see Langton 2018b; Searle 2010). However, if such institutional authority is a necessary felicity condition for powerful speech acts that modify our social world—by creating new institutional facts, (de-)legitimizing actions, commanding others, etc.—then “ordinary”, “low-status” speech seems seriously constrained in what it can achieve. In particular, it cannot constitute subordination—a complex speech act that ranks others as inferior, deprives them of rights, and legitimizes discrimination (Langton 1993)—via hate speech, pornography, or some other variety of harmful discourse. Lacking the power to do harm, ordinary discourse appears forever innocuous. However, the harm is there. Given this, we arrive at the second paradox: recognized authority seems to be a necessary condition for performing powerful speech acts, including those that subordinate and harm others; however, while this condition is by definition absent from most ordinary discourse, the power and the harm are still there.

As one would expect from philosophical work, these paradoxes can be solved via conceptual effort, mostly by distinguishing various forms of authority. There are at least three forms of response to the first paradox. One might deny that deference to the authority’s judgment is presumptively reasonable to start with—experts too can be mistaken or biased (Duijf 2021; Mizrahi 2018). The polar opposite is to maintain that deference to authority has not just a presumptive but indeed a pre-emptive status (Raz 2006; Zagzebski 2012). Since experts are experts precisely because they know better, consistently following their judgements is, overall, an epistemically better strategy than trying to correct their judgments with one’s inexpert reasons; the latter are thus effectively pre-empted. Finally, one can argue that an argument from (an expert’s) authority, while presumptively good, should be demoted to but one of the elements in the overall mix of reasons we weigh (Jäger 2016; Lackey 2018; cf. Steward 2020). Apart from non-experts’ own understanding of the topic, this mix includes means that they have to reasonably assess the expertise of experts, without becoming experts themselves—i.e., they can verify experts’ institutional credentials, check if there are particular interests biasing what they say, compare their past predictions with what actually happened, or see how experts fare in public discussions with other experts (Goldman 2001, 2018; cf. Collins and Weinel 2011; Fuhrer et al. 2021; Goodwin 2011).16 On such a view, authority is an ubiquitous but also tamed phenomenon of human rationality. Important for the discussion here, Lackey (2018) theorizes this view as “the expert-as-advisor model”—rather than pronouncing authoritative judgements, expert advisors offer guidance which should be adjusted to the advisee’s beliefs and concerns via interactively constructed arguments and explanations. The question thus turns to the shape and quality of argumentative activities.

The second paradox can be solved by examining different sources of authority (Maitra 2012; see also Bianchi 2019; Langton 2015, 2018b). What Austin and other early speech act theorists envisaged was a basic (positional) authority, granted in virtue of occupying an institutionally recognized position—that of a president, judge, priest, army general, or ship captain, for example. However, this authority extends to various forms of delegation of authority, such as when the captain officially delegates the mate to run the ship as he sleeps. Maitra (2012) calls this derived (positional) authority. Importantly, derived authority can be given actively, as in our captain’s case, or passively, via omission rather than action. The mate can instead be bossing around the deck without prior conferral of the captain—but if the captain turns a blind eye to this, the mate is presumed to be acting on the captain’s blessing. Finally, such tacit acceptance of authority by virtue of simply going along with someone’s initiative can also be granted by people without superior positional authority at all. The captain and the mate both drown in a shipwreck, and so a private crew member takes to distributing tasks among the survivors on the desert island: “go and pick up wood”, do this, do that. If their directives are followed, however reluctantly, by others, the entrepreneurial survivor becomes the boss of the island. Maitra calls this licensed authority, which in a way magically pops up, ex nihilo, without prior chain of command, as it were.17 It is precisely via such licensing that ordinary discourse can become authoritative, thus resolving the second paradox.

On top of these distinctions, the first paradox can be understood as a paradox of epistemic authority, while the second one is largely a paradox of deontic authority. The former—also called theoretical, cognitive, de facto, or know-that authority—is an authority to perform reliable assertions, grounded in knowledge or expertise within a specific field. The latter—also called practical, administrative, executive, de jure, or know-how authority—is instead an authority to issue commands, based in a recognized entitlement to direct others. A superbly trained lieutenant can be an epistemic authority to an uninstructed major, but it is the latter who, by his military rank, has deontic authority over the former (Bocheński 1965; see Brożek 2013; Koszowy and Walton 2019; Langton 2015, 2018b; Raz 2006). Bocheński’s distinction is powerful, as it mirrors “two main classes of utterances”: declaratives and imperatives, the former having the word-to-world direction of fit, the latter having the world-to-word direction of fit (Searle 1975a, 2010). However, there are complex cases that attract scrutiny, such as a doctor’s imperatives (“take two of these each morning”) or a master dancer’s instructions, which are both epistemically and deontically grounded (Goodwin 1998; Langton 2015).18

In this way, the picture of authority has gotten murky. We have two broad classes of authority (epistemic and deontic), three forms of authority (basic, derived, and licensed), and two basic perspectives to understand their impact (as pre-emptive or presumptive reasons). And there is more, as will shortly become apparent. Nonetheless, these distinctions are instrumental in understanding the complex dynamics of authority in much public discourse.

Returning to the Trump example, it becomes apparent that he takes an argument from an (ostensible) epistemic expert (Bill Bryan), and then couches it in his deontic authority of the president. Thus, an expert’s consideration of preliminary scientific results morphs, rather too hastily and surreptitiously, into an official directive, whether it was a suggestion, request, recommendation, or advice. Given this, anyone listening would be best advised not to treat Trump’s words as reasons pre-empting other reasons, for instance those of the producer of Lysol and Dettol who in the most direct words possible disclaimed the use of these disinfectants for COVID treatment. Others, such as the Democratic Senate Minority Leader, Charles E. Schumer, called out Trump for being “a quack medicine salesman.”19 Such critical moves prevent Trump from gaining a derived epistemic authority, quite enthusiastically given by Bryan (“We’ll get to the right folks who could [test the light and bleach treatments]”), and rather implicitly by the quiet Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, who sat right by the president but failed to protest his “musings.” They also point to the question of the basic structure of arguments from authority and their fallaciousness—rightly the domain of argumentation theory, to which I now turn.

4. Arguments from and to Authority

4.1. Arguments from Authority in Argumentation Theory

As already mentioned, argumentation theory has a long tradition of examining arguments from authority. The key question is a normative one: under which conditions and in which forms are such arguments reasonable? There is no space to discuss this tradition here even briefly (see Zenker and Yu, forthcoming, for a recent, comprehensive account). Instead, I immediately turn to a standard approach that relies on argument schemes, recognized forms of inference derived, one way or another, from Aristotle’s topoi (Rigotti and Greco 2019). A good example of this approach is Walton’s proposal, which was recently revised in Koszowy and Walton (2019; see also Walton et al. 2008). For Walton and his colleagues, the basic argument from (expert’s epistemic) authority consists of a straightforward syllogistic structure:20

Major Premise: Source E is an expert in subject domain S containing proposition A.Minor Premise: E asserts that statement A is true (false).Conclusion: A is true (false).

The inference rule warranting the step from premises to the conclusion—“generally, but subject to exceptions […] if an expert states that a statement A is true, then A can tentatively be accepted as true”—is, according to Koszowy and Walton, merely optional, as one of the “several ways” the simple scheme “can be expanded” (2019, p. 291). Nonetheless, it is this inference rule that reveals the defeasible character of arguments from authority (mind the “generally, but subject to exceptions” clause). More specifically—something that Walton’s approach is well-known for—it is “subject to defeat by the asking of appropriate critical questions” (Koszowy and Walton 2019, p. 292), namely:

Expertise Question: How credible is E as an expert source?Field Question: Is E an expert in the field F that A is in?Opinion Question: What did E assert that implies A?Trustworthiness Question: Is E personally reliable as a source?Consistency Question: Is A consistent with what other experts assert?Backup Evidence Question: Is E’s assertion based on evidence?

These questions seem to be standard considerations in appraising epistemic authority. Indeed, Goldman’s list of “five possible sources of [argument-based] evidence” for evaluating experts by novices captures an almost co-extensive set of elements:

(A) Arguments presented by the contending experts to support their own views and critique their rivals’ views. (Cf. consistency and backup evidence question)(B) Agreement from additional putative experts on one side or the other of the subject in question. (Cf. consistency and expertise questions)(C) Appraisals by “meta-experts” of the experts’ expertise (including appraisals reflected in formal credentials earned by the experts). (Cf. field and expertise questions)(D) Evidence of the experts’ interests and biases vis-à-vis the question at issue. (Cf. trustworthiness question)21(E) Evidence of the experts’ past “track-records” (Cf. backup evidence and expertise question)(Goldman 2001, p. 91)

Another approach to an argument scheme from an expert opinion is to drain the scheme from any such substantive considerations and instead focus on the barebones of the inference itself. Wagemans (2011) is one exponent of such a minimalistic approach, which is grounded in the pragma-dialectical approach to argumentation (note the conclusion-on-the-top convention). According to him, the scheme can be limited to the following elements:

1 Opinion O (X) is true or acceptable (Y). [conclusion]1.1 Opinion O (X) is asserted by expert E (Z). [premise]1.1′ Being asserted by expert E (=Z) is an indication of being true or acceptable (=Y). [linking premise aka the inference rule]

This scheme is inferentially correct, as it includes the necessary inference rule as indeed necessary, rather than optional. It can further be extended to include various substantive considerations, such as those above. Indeed, Wagemans (2011) offers one good way of doing it, resorting to the concept of subordinative (aka serial) argumentation, whereby one of the two premises (1.1 or 1.1′) is further supported by more precise sub-arguments with substantive content regarding the quality of expertise.

4.2. Relation between Arguments from and to Authority

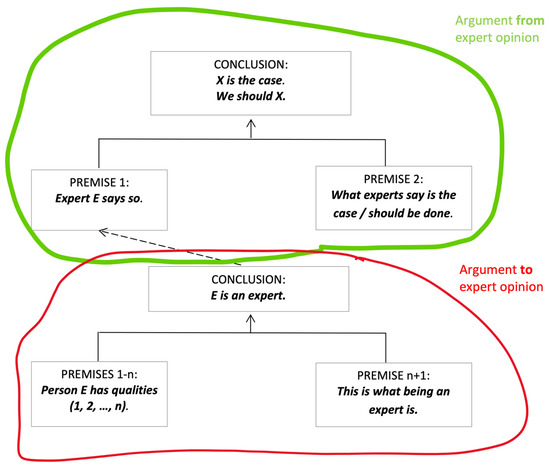

The scheme below (see Figure 1) is a simple way of organizing the tradition of investigating appeals to authority in terms of an argument scheme.

Figure 1.

Arguments from and to expert opinion.

The scheme includes most of the elements recognized in the argumentation literature but rearranges them. It assumes informal arguments are composed of two premises, not unlike Toulmin’s (1958) Data (Premise 1) and Warrant (Premise 2).22 (Each of these can be further supported, e.g., via Backing the Warrant: see Wagemans 2011.) It is formulated so as to include both the epistemic (x is the case) and deontic (we should do x) authority of experts.23 However, here is the difference with an approach like Wagemans’s: nothing like the subordinative argumentative support is yet present here. Instead, there are two different arguments linked by an obvious semantic presupposition (the line between Conclusion of an argument to expert opinion and Premise 1 of an argument from expert opinion is dashed to indicate presuppositional rather than argumentative support). On top, there is the argument from expert opinion—an expert says something and we argue from this that it is the case/should be done. The inference rule (Premise 2) states that what experts say is the case/should be done. Being a presumptive rule, it can be controverted on a case-by-case basis via an all-things-considered judgement, much in the way Goldman (2001, 2018), Lackey (2018), or Rescher (2006) theorize it. However, it can also be objected to as a rule: Are experts really to be revered and followed? (cf. Duijf 2021; Mizrahi 2018). That would be the only critical question to the argument scheme as a scheme. Strange as it may sound, it is of course the question many skeptics, including populists resorting to cheap anti-science skepticism, ask. Premise 1 can be questioned too, but in a manner of an empirical, rather than inferential, question: perhaps expert E just never said X?

Importantly, a simple semantic presupposition of Premise 1 of the argument from expert opinion is that E is (indeed) an expert. Are they? Once we start critically examining this issue, it becomes a to-be-defended conclusion of the argument to expert opinion. How do we defend that someone is an expert? Goldman’s (2001) and Koszowy and Walton’s (2019) considerations nicely capture what expertise is in the social world we live in.24 An arguer can thus offer a set of premises (1, 2, …, n) that defend the status of the expert in question. This, again, opens a set of empirical questions: Did they really publish in top peer-reviewed journals? Are they a PhD in the discipline under discussion? Are they acknowledged in that discipline? Did they “get things right” in the past? Even if so, are they not biased this time round? etc. Finally, the inference rule (Premise n + 1) states that the set of qualities adduced is sufficient to identify someone as an expert. This too can be challenged: perhaps being against the consensus within the discipline is what being a real talent is (as the 19th-century “solitary genius” myth would have it), or having a strong, partial interest is an inherent quality of expertise?25

This layout linking arguments from and to authority—and, in particular, the epistemic authority of an expert—brings about a number of advantages. It seems to strike the right balance between the somewhat baroque schemes of Walton and colleagues and the minimalistic scheme of Wagemans. It incorporates all chief elements recognized by them in a novel order that rearranges and clarifies the critical questions that can be asked when authority is to be challenged. Perhaps most surprisingly, it puts all but one of Walton’s critical questions as targeting the argument to rather than from authority.26 Further, these are questions against the empirical rather than the inferential premise of the scheme (against Toulmin’s Data, rather than Warrant). They are thus doubly removed from what a critical question against a scheme of reasoning should be. The rationale behind this relegation is quite straightforward: if we are not dealing with experts to start with, we can hardly have an argument from expert opinion. (Mind you, even if there is a genuine expert/authority invoked, an argument from their opinion can still go wrong—an expert can be misrepresented, or expertise can be in-principle challenged.)

In this way, the layout organizes the ways of challenging authority.

5. Authority Challenged with Arguments

In her account of how authority can be accommodated and challenged, Langton concludes the following: “Hearers can sometimes respond to harmful speech by arguing against it; and sometimes, in a quite different way, by blocking the conditions of its success” (Langton 2015, pp. 28–29). Langton’s blocking (see also Langton 2018a; Lewiński 2021a) centers on hearers’ refusal to accommodate certain conditions of felicity of various speech acts, notably the condition of authority constitutive of various exercitive and verdictive (Austin 1962) or directive and declarative (Searle 1969, 1975a) speech acts. She treats such an illocutionary challenge (see also Caponetto 2020) “in a quite different way” than a locutionary challenge, that is, arguing against something. “I don’t take orders from you” or “you’re not entitled to give me orders”27 are thus radically different from saying, “We should first find fire, and only then go pick up wood”, or, “Wood? On a desert island!?”

On the account presented here, this is a false dichotomy—“blocking the conditions of [a speech’s] success” is arguing too, if one adopts a sufficiently pragmatic notion of argumentation. I have defended such a notion here,28 focusing on the argument from and to (epistemic) authority. What remains to be done is to fill out some important details of this account.

Langton’s view on what “arguing against” is reflects a general philosophical inclination to limit argumentative justification and challenge to the propositional content of what is said. Pollock’s (1987) account is one good instance of this inclination. Pollock famously distinguished between two ways of attacking a prima facie reason: a rebutting defeater, an argument for a conclusion that contradicts the conclusion defended by the other arguer, and an undercutting defeater, an attack on the inferential link (warrant) between a premise and the conclusion adduced. Both are obviously forms of locutionary challenge, which are limited to questioning the propositional content of the conclusion (¬C) or the inference rule warranting the move from the premise to the conclusion (¬(P→C)). However, current argumentation theory offers a much richer understanding of what a critical argumentative reaction to someone else’s discourse can be (see esp. Krabbe and van Laar 2011). While there is no room here to fully benefit from this work, I focus on how a discourse such as Trump’s can be challenged, relying on the discussion in the previous two sections. In doing this, I hope to show how the pragmatic and argumentative perspectives reinforce each other in the task of understanding how authority can be challenged.

As discussed in Section 2, Trump’s (implicit) conclusion that “bleach can be a powerful way of treating COVID-19” can, and has been, questioned on locutionary and perlocutionary grounds. By way of a direct rebutting defeater (“under no circumstance should […] disinfectant products be administered into the human body”) or some critical question (“Are you sure?”, “How can it ever work?”, “Isn’t it dangerous?”), the conclusion of the argument from authority (see Figure 1) can be challenged. Further, the scheme’s Premise 2, which expresses the inferential rule, can be defeated by some undercutter (but it has not been; to the contrary, it has been quite strongly defended by critical commentators). Curiously, the examination of Premise 1—what Trump, the purported authority, actually said—took on a decidedly illocutionary character. While some commentators criticized Trump for “asserting” falsehoods, others downgraded his remarks to “musings” or “wonderings.” Most, however, understood him to be “suggesting”, “recommending”, or “advising” the use of bleach and UV light. These directive speech acts turn our attention to the authority-based felicity conditions and thus to the argument to authority.

The first obvious objection here is that Trump is not an expert at all. As discussed earlier, there is an interesting ambiguity here between him possessing the supreme deontic authority, that of the President of the United States, and him not possessing satisfactory epistemic authority. Despite this ambiguity, the conclusion of the argument to authority has been unambiguously challenged, most explicitly by those who called him “a quack medicine salesman” (see Section 3). Further, more precise details of the authority in question can be challenged (see Premise 1 − n of the argument to expert opinion in Figure 1). Trump is quite obviously not trained in any field remotely close to medicine or epidemiology. He does not even possess minimal, isolated, second-hand knowledge, as he did not attend the meeting of the coronavirus taskforce, nor did he make any effort to listen to his scientific advisors trying to brief him on their deliberations (on that particular day, or as a general practice; see McGraw and Stein 2021). Importantly, while the advisors’ silence as he was delivering his remarks might be seen as a form of derived authority, it can only improve his credibility in the eyes of the clueless audience, but not his proper epistemic expertise. Contrary to credibility, knowledge cannot be supplied by one’s audience (Langton 2015). However, even credibility has been undermined, given the ample and immediate disclaimers by most any expert taking to public or social media. Further, Trump can also be accused of ideological bias, with the track-record of his advocacy for hydroxychloroquine providing a good counterargument here. Finally, Premise n + 1 of the argument to expert opinion can be challenged; perhaps it is enough for Trump, to count as an expert, to “present [his] talent” rather than engage in academic hairsplitting?

In this way, various illocutionary forms of blocking of what seems dangerously misfired advice are reinterpretable as explicit argumentative challenges to various elements of a clearly laid-out scheme that links an argument from expert opinion to an argument to expert opinion.

Two important remarks are in place, both concerning the possible authority bestowed on Trump by his hearers.29 First, the fact that Trump’s advisors present at the meeting—notably Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus coordinator—did not directly object to or block his suggestions demonstrates a general interpretative difficulty for any approach based on tacit approval. It can be a silent act of licensing or accommodating someone’s authority; however, it can also result from inherent communicative and social obstacles. Birx and Bryan could, and likely would, be immediately fired for challenging their commander-in-chief. Yet, even less intimidating circumstances can be hard for potential authority challengers. As a linguistic activity involving doubt, disagreement, even confrontation, interpersonal argumentation in general is socially and psychologically costly and potentially dangerous (Paglieri and Castelfranchi 2010). Similarly, blocking is fraught with several systemic barriers (Langton 2018a, pp. 159–161): it requires wit and courage that not everybody can muster in the spur of the moment. But then again, is being “a person that is hard to challenge” not one of the inherent features of being in a position of authority to start with? Second, even if Trump’s hearers, from his expert advisors to “the general public”, somehow granted him authority out of their own will, what kind of authority would that be? As discussed above, deontic authority can be established by collective, even if tacit, recognition (see esp. Langton 2015; Maitra 2012; Witek 2013)—and so it can be removed by voting someone out of office or otherwise dismissing them. Epistemic authority comes with social recognition too, but that does not mean it is socially constructed all the way down. At its core lies knowledge and expertise that, on a mainstream interpretation, is independent of someone else’s appraisal (see esp. Goldman 2018). All the same, successful argumentative interactions potentially contribute to knowledge while failed ones gradually hack away at it (anything from the Socratic dialogues to our back-and-forth exchanges with peer reviewers attests to it). Herein lies the power of challenging purported experts with various forms of counterargumentation presented here: while some of it can be as immediate as Langton’s blocking, other forms can well rely on patient reflection and persistent communicative engagement.

6. Conclusions

The paper set out to address the following question: In which ways can the authority of the speaker be challenged for argumentative purposes? To address this question, I examined details of a much-debated event of public discourse, Trump’s apparent “advice” to use bleach and UV light as a COVID-19 treatment. This led me to, however briefly, discuss some of the broader theoretical questions of authority in public argumentation. While engaging in this discussion, I hope to have showed how nuanced, yet fundamental, problems of public discourse identified by speech act theorists and social epistemologists can become an inspiration and an object of study for argumentation theorists. Likewise, in turn, how argumentation theory can feed back into a broad pragmatic study of discourse thanks to its developed framework of concepts and methods for understanding and evaluating forms of inference, such as arguments from and to authority. All this is largely unsurprising, given that authority is a complex pragmatic and argumentative phenomenon of public discourse. I hope the proposal of this paper can advance our understanding of its mechanisms.

Funding

This work was funded by national funds through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT: Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) under the project UIDB/00183/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank audiences at the University of Neuchâtel, Autonomous University of Madrid, University of Granada, University of Sorbonne Nouvelle, and the Nova University Lisbon for precious comments and criticisms of the earlier drafts of this work. My special thanks go to Steve Oswald and the two anonymous reviewers for their detailed, constructive criticisms of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | I follow the original terminology introduced by Bocheński (1965; see Brożek 2013; Koszowy and Walton 2019), while acknowledging the theoretical-practical distinction as perhaps more standard (Raz 2006; see Langton 2015), although potentially confusing too (Langton 2018b). Here, I use the epistemic interchangeably with the theoretical, and deontic with practical, without any firm conceptual commitments. |

| 2 | Official transcript from: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-vice-president-pence-members-coronavirus-task-force-press-briefing-31/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). For a video recording of the fragment in question, see https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/it-s-irresponsible-it-s-dangerous-experts-rip-trump-s-n1191246 (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). |

| 3 | As quoted in The Washington Post report “Trump claims controversial comment about injecting disinfectants was ‘sarcastic’” available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/24/disinfectant-injection-coronavirus-trump/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). |

| 4 | In the words of the former Food and Drug Administration commissioner Scott Gottlieb cited in The Washington Post report “Trump claims controversial comment about injecting disinfectants was ‘sarcastic’” available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/24/disinfectant-injection-coronavirus-trump/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). See also NBC News’ article “‘It’s irresponsible and it’s dangerous’: Experts rip Trump’s idea of injecting disinfectant to treat COVID-19” available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/it-s-irresponsible-it-s-dangerous-experts-rip-trump-s-n1191246 (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022) and The Guardian’s piece “Coronavirus: medical experts denounce Trump’s theory of ‘disinfectant injection’” at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/trump-coronavirus-treatment-disinfectant (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). |

| 5 | As pointed out by an anonymous referee, it can also be an indirect way of challenging Trump’s presupposition of expertise. When commentators such as Dr. Grimes call out Trump’s falsehoods—“No, you cannot inject UV light into your body to cure #COVID19—neither biology or physics work that way”—they simultaneously suggest that Trump knows nothing about biology and physics. |

| 6 | As reported in: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/24/health/sunlight-coronavirus-trump.html (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). |

| 7 | See however Searle’s reservations on treating “suggestion” in terms of a separate illocutionary act to start with: “I can insist that we go to the movies or I can suggest that we go to the movies; but I can also insist that the answer is found on page 16 or I can suggest that it is found on page 16. The first pair are directives, the second, representatives. […] Both ‘insist’ and ‘suggest’ are used to mark the degree of intensity with which the illocutionary point is presented. They do not mark a separate illocutionary point at all. […] Paradoxical as it may sound, such verbs are illocutionary verbs, but not names of kinds of illocutionary acts” (Searle 1975a, p. 368). (Note that a similar illocutionary ambiguity between (weak) assertives and directives applies to “wondering.”) This point, while broadly correct, is inconsequential to the analysis in this paper; for consistency, I treat suggestion in its directive sense throughout. |

| 8 | Indeed, Trump clearly turns his gaze and attention to Bryan while also addressing him several times via “you”, as in “I think you said that that hasn’t been checked, but you’re going to test it.” See: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/it-s-irresponsible-it-s-dangerous-experts-rip-trump-s-n1191246 (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). |

| 9 | For a detailed analysis of the argumentative functions of reported speech see Gobbo et al. 2022). One such function is, quite expectedly, to construct an argument from authority (see Section 4 below), while an important challenge is to precisely dissect the various voices reported, thus pinning down the speaker’s own commitments. |

| 10 | Asking a question—itself a directive speech act—has long been recognized as a vehicle for a wide array of other, indirect speech acts, notably requesting (Searle 1975b). While “can you pass me the salt?” is the standard, idiomatic example of it, “is there a way we can do something like that[?]” would function analogously. But given the official authority of the president over his advisors, it can even be understood as a command, with “yes, sir!” being the most appropriate response here, as well shown in Bryan’s earlier “We’ll get to the right folks who could”. |

| 11 | See Note 7 above. |

| 12 | As reported in The Guardian’s piece “Coronavirus: medical experts denounce Trump’s theory of ‘disinfectant injection’” at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/trump-coronavirus-treatment-disinfectant (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). For a detailed case study exposing Trump’s skill of evading efforts to pin down his standpoint by inquisitive journalists during press conferences, see Jacobs et al. 2022). |

| 13 | See, e.g., https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/24/health/sunlight-coronavirus-trump.html (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022); https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/trump-disinfectants-covid-19/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). In her study of figleaves—linguistic techniques meant to mask harmful content of a speaker’s message—in political discourse, Saul (2021, pp. 170–171) singles out the “I was only joking” or “I was being ironic” response as one common way of disingenuously denying the seriousness of some prior, harmful speech act. |

| 14 | Unsurprisingly, the critique of appeals to authority undergirds the secular Enlightenment mindset, as epitomized in Locke’s denouncement of the argumentum ad verecundiam in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) (see Bachman 1995; Goodwin 1998; Hamblin 1970). |

| 15 | Work on epistemic authority and epistemic injustice (Fricker 2007) has brough attention to the fact that also Austinian constatives—and not merely performatives—are in the end warranted by authority. See also Austin (1962, p. 137) on (not) having the right / (not) being in a position “to state” something as parallel to (not) having the right “to order”. |

| 16 | It is not hard to see that the possibility of non-expert assessment of experts solves a well-known version of the first paradox of authority that runs as follows. We need experts because we cannot have sufficient knowledge on all the things in the world; reliance on such experts is only reasonable if we appeal to the right experts; to select right experts, we need to evaluate their reasons on substantive grounds; but to do so, we should be experts ourselves. Yet this directly contradicts the first premise, that we need to resort to the judgement of experts precisely because we ourselves cannot be experts. Goldman’s (2001) argument removes the evaluation on substantive grounds premise, thus avoiding the paradox. See Fuhrer et al. (2021) and Moldovan (2022) for further discussion. |

| 17 | The desert island example with the “go and pick up wood” imperative is due to Austin (1962, p. 28) and has been recently discussed, among others, by Langton (2015, 2018b) and Witek (2013, 2021a) as an original example of accommodated authority, that is, authority tacitly provided by other parties to a conversational situation. See Lewis (1979) for an influential account of “the rule of accommodation”. |

| 18 | Already in his Elements of Logic (1826) and Elements of Rhetoric (1828), Richard Whately distinguished between the authority of an expert’s “example, testimony, or judgment” (auctoritas) and the authority of those in a position of power (potestas) (Hansen 2006). (Modern languages such as Polish similarly use autorytet for auctoritas but władza for potestas.) While the deference to the former might be presumptively reasonable, it might also be usurped by the latter, thus leading to the fallacy of authority (argumentum ad verecundiam), not unlike in our Trump’s case. |

| 19 | As reported by The Washington Post in “Trump claims controversial comment about injecting disinfectants was ‘sarcastic’”: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/24/disinfectant-injection-coronavirus-trump/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022). For an analysis of the epistemic status of the authority of a “quack doctor”—whose gullible disciples can only present with credibility, but never the knowledge-based expertise—see Langton (2015). |

| 20 | This scheme directly concerns the epistemic authority of an expert. Parallel schemes for deontic authority can be found in Koszowy and Walton (2019). |

| 21 | Here is another well-known paradox of epistemic authority, which Guerrero (2021) has recently analyzed as the “Interested Expert Problem.” On a standard view, experts should possess impartial knowledge, free of contaminating vested interests and selective biases (hence conditions such as Goldman’s and Walton’s). Real experts are impartial experts. All the same, expertise is intricately intertwined with interests: particular interests can motivate knowledge, result from knowledge, or develop simultaneously with knowledge. A climate activist can become a maritime biologist, a maritime biologist can become a climate activist, or both activities can grow in parallel from experiencing the radically changing oceans (see Guerrero 2021, for illuminating examples and broader theoretical analysis). This might be a feature common enough to identify an “impartial” or “disinterested expert” as a contradiction in terms. For argumentation scholars, this paradox explains the perplexing features of the “circumstantial” ad hominem fallacy, a form of attack whereby an arguer’s interests and biases, rather than arguments, are challenged (e.g., van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1992). Since via such attacks, given the bias identified, the attacker is effectively “claiming that the other party has no right to speak”, they amount to “offences against a fundamental norm for argumentative discourse”, the freedom rule (van Eemeren and Grootendorst 1992, p. 153). All the same, as identified by Walton and others, such attacks are reasonable challenges to authority-based arguments. See Zenker (2011) for further discussion. |

| 22 | I am aware that in the context of the lively debates in argumentation theory this representation seems, at best, careless. Freeman (2011, p. 88) argues that Toulmin’s warrants representing inference rules “are not parts of arguments” and, as such, “should not be included in diagrams of argument texts”. Similarly, Hitchcock chastises the practice of presenting warrants as premises as being “radically misconceived”: “The claim [conclusion] is not presented as following from the warrant; rather it is presented as following from the grounds [data] in accordance with the warrant. A warrant is an inference-licensing rule, not a premiss.” (Hitchcock 2017, pp. 83–84, italics in the original). While this dispute is not merely verbal, nothing I say here rests on any particular theoretical commitment in this respect. Premises or not, warrants contribute to any argument by licensing its inference. As such—precisely in the spirit of Toulmin’s (1958) original analysis—they should be “laid out” for our critical inspection. And this is my intention here. |

| 23 | As such, it excludes the “purely” deontic authority of non-experts, such as the authority of Bocheński’s (1965, p. 167) “rather unintelligent and uninstructed major” over “a lieutenant who is highly skilled in military science” (see p. 8 above). But the scheme can easily be tweaked to include this variety of authority too. Argument from authority: Premise 1: Deontic authority A says: Do X!; Premise 2: Deontic authorities should be followed; Conclusion: We should X. Argument to authority: Premise 1 − n: Person A has qualities (1, 2, …, n) (e.g., is a formal boss, a delegated superior, or an informally recognized leader); Premise n + 1: This is what being a deontic authority is; Conclusion: A is a deontic authority. Thus, a set of critical challenges to such a purely deontic authority is organized similarly to the scheme to and from expert authority in Figure 1. |

| 24 | For simplicity, I gloss over the question of whether the characteristics of expertise laid out by Goldman and Koszowy and Walton are ontological or epistemological, that is, whether they constitute expertise to start with or rather let us identify pre-existing experts (see Goldman 2001, 2018, and Lackey 2018, for discussion). My formulation might suggest the former—a kind of conceptual definition to be filled in—but it works equally well with the epistemic reading. See also Croce (2019) and Scholz (2018). |

| 25 | See Croce (2019); Fuhrer et al. (2021); Goldman (2018); Moldovan (2022); Scholz (2018) for a recent discussion “on what it takes to be an expert”. |

| 26 | The only straightforward exception being the “opinion question” targeting the empirical Premise 1 of argument from authority (as such, also not a proper inferential scheme question). The “consistency” and “backup evidence” questions are ambiguous between addressing Premise 1 of the argument from authority and one of the Premises 1-n of the argument to authority. Yet, the latter reading seems to take precedence: saying something consistent with other experts and properly backed up (e.g., by scientific results) is a general characteristic of an expert, rather than a contingent feature of one assertion. |

| 27 | Austin’s (1962, p. 28) original examples discussed by Langton (2015). |

| 28 | See Lewiński (2021c); Lewiński and Aakhus (2022) for further details. |

| 29 | And both indicated by anonymous reviewers as challenging problems. |

References

Primary Sources

https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-vice-president-pence-members-coronavirus-task-force-press-briefing-31/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/it-s-irresponsible-it-s-dangerous-experts-rip-trump-s-n1191246 (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/24/disinfectant-injection-coronavirus-trump/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.c-span.org/video/?c4871173/president-trump-injecting-disinfectants (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52407177 (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/trump-coronavirus-treatment-disinfectant (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/24/health/sunlight-coronavirus-trump.html (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.chicagotribune.com/coronavirus/ct-nw-trump-white-house-sunlight-heat-fight-virus-20200424-7dnhtyxltvdazkp24mybuefmou-story.html (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/trump-disinfectants-covid-19/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/23/trump-bleach-one-year-484399 (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).https://www.rb.com/media/news/2020/april/improper-use-of-disinfectants/ (accessed on 8 Feburary 2022).Secondary Sources

- Aristotle. 2007. On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse, 2nd ed. Translated by George A. Kennedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, John Langshaw. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, James. 1995. Appeal to authority. In Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings. Edited by Hans V. Hansen and Robert C. Pinto. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, pp. 274–86. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, David, and Jason Stanley. 2019. Toward a non-ideal philosophy of language. Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 39: 501–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Claudia. 2019. Asymmetrical conversations: Acts of subordination and the authority problem. Grazer Philosophische Studien 96: 401–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigi, Sarah. 2018. The role of argumentative practices within advice-seeking activity types: The case of the medical consultation. Rivista Italiana di Filosofia Del Linguaggio 12: 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bocheński, Joseph M. 1965. Analysis of authority. In The Logic of Religion. New York: New York University Press, pp. 162–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brożek, Anna. 2013. Bocheński on authority. Studies in East European Thought 65: 115–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Caponetto, Laura. 2020. Undoing things with words. Synthese 197: 2399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Harry, and Martin Weinel. 2011. Transmuted expertise: How technical non-experts can assess experts and expertise. Argumentation 25: 401–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corredor, Cristina. 2020. Deliberative speech acts: An interactional approach. Language & Communication 71: 136–48. [Google Scholar]

- Croce, Michel. 2019. On what it takes to be an expert. The Philosophical Quarterly 69: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijf, Hein. 2021. Should one trust experts? Synthese 199: 9289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, James B. 2011. Argument Structure: Representation and Theory. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer, Joffrey, Florian Cova, Nicolas Gauvrit, and Sebastian Dieguez. 2021. Pseudoexpertise: A conceptual and theoretical analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 732666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, David P. 1963. Practical Reasoning: The Structure and Foundations of Prudential and Moral Arguments and Their Exemplification in Discourse. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gobbo, Federico, Macro Benini, and Jean H. M. Wagemans. 2022. More than relata refero: Representing the various roles of reported speech in argumentative discourse. Languages 7: 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, Alvin I. 2001. Experts: Which ones should you trust? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 63: 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, Alvin I. 2018. Expertise. Topoi 37: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, Jean. 1998. Forms of authority and the real ad verecundiam. Argumentation 12: 267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, Jean. 2011. Accounting for the appeal to the authority of experts. Argumentation 25: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Mitchell S. 2009. Speech acts, the handicap principle and the expression of psychological states. Mind & Language 24: 139–63. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, Alexander. 2021. The interested expert problem and the epistemology of juries. Episteme 18: 428–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, Charles Leonard. 1970. Fallacies. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Hans V. 2006. Whately on arguments involving authority. Informal Logic 26: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Thierry. 2022. Ethos and pragmatics. Languages 7: 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Thierry, and Steve Oswald. 2021. Everybody knows that there is something odd about ad populum arguments. In The Language of Argumentation. Edited by R. Boogaart, H. Jansen and M. van Leeuwen. Cham: Springer, pp. 305–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, David. 2017. On Reasoning and Argument. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Sally. 1992. “Virtual standpoints” and the pragmatics of conversational argument. In Argumentation Illuminated. Edited by Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, J. Anthony Blair and Charles A. Willard. Amsterdam: SicSat, pp. 260–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Sally. 2008. Black box arguments. Argumentation 22: 437–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Scott, Sally Jackson, and Xiaoqi Zhang. 2022. What Was the President’s Standpoint and When Did He Take It? A Normative Pragmatic Study of Standpoint Emergence in a Presidential Press Conference. Languages 7: 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, Christoph. 2016. Epistemic authority, preemptive reasons, and understanding. Episteme 13: 167–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, Justin. 2017. Code words in political discourse. Philosophical Topics 45: 33–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, Justin. 2021. Code words. In The Routledge Handbook of Social and Political Philosophy of Language. Edited by J. Khoo and R. Sterken. New York: Routledge, pp. 147–60. [Google Scholar]

- Koszowy, Marcin, and Douglas Walton. 2019. Epistemic and deontic authority in the argumentum ad verecundiam. Pragmatics and Society 10: 151–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krabbe, Eric C. W., and Jan Albert van Laar. 2011. The ways of criticism. Argumentation 25: 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, Rebecca. 2014. Performative force, convention, and discursive injustice. Hypatia 29: 440–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, Jennifer. 2008. Learning from Words: Testimony as a Source of Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lackey, Jennifer. 2018. Experts and peer disagreement. In Knowledge, Belief, and God: New Insights in Religious Epistemology. Edited by M. A. Benton, J. Hawthorne and D. Rabinowitz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 228–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lance, Mark, and Rebecca Kukla. 2013. ‘Leave the gun; take the cannoli’: The pragmatic topography of second-person calls. Ethics 123: 456–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langton, Rae. 1993. Speech acts and unspeakable acts. Philosophy and Public Affairs 22: 293–330. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, Rae. 2015. How to get a norm from a speech act. The Amherst Lecture in Philosophy 10: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, Rae. 2018a. Blocking as counter-speech. In New Work on Speech Acts. Edited by Daniel Fogal, Daniel W. Harris and Matt Moss. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 144–64. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, Rae. 2018b. The authority of hate speech. In Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Law. Edited by John Gardner, Leslie Green and Brian Leiter. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 123–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lewiński, Marcin. 2021a. Illocutionary pluralism. Synthese 199: 6687–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewiński, Marcin. 2021b. Conclusions of practical argument: A speech act analysis. Organon F 28: 420–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewiński, Marcin. 2021c. Speech act pluralism in argumentative polylogues. Informal Logic 41: 421–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewiński, Marcin, and Mark Aakhus. 2022. Argumentation in Complex Communication: Managing Disagreement in a Polylogue. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, David. 1979. Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic 8: 339–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, Ishani. 2012. Subordinating speech. In Speech and Harm: Controversies over Free Speech. Edited by Ishani Maitra and Mary Kate McGowan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 94–120. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Lucy. 2021. Your word against mine: The power of uptake. Synthese 199: 3505–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, Mary Kate. 2019. Just Words: On Speech and Hidden Harm. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, Meridith, and Sam Stein. 2021. It’s been Exactly One Year since Trump Suggested Injecting Bleach. We’ve Never been the Same. Politico. Available online: https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/23/trump-bleach-one-year-484399 (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- Mizrahi, M. 2018. Arguments from expert opinion and persistent bias. Argumentation 32: 175–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, Andrei. 2022. Technical language as evidence of expertise. Languages 7: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville-Shepard, Ryan. 2019. Post-presumption argumentation and the post-truth world: On the conspiracy rhetoric of Donald Trump. Argumentation and Advocacy 55: 175–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglieri, Fabio, and Cristiano Castelfranchi. 2010. Why argue? Towards a cost–benefit analysis of argumentation. Argument and Computation 1: 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, John. 1987. Defeasible reasoning. Cognitive Science 11: 481–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raz, Joseph. 2006. The problem of authority: Revisiting the service conception. Minnesota Law Review 90: 1003–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rescher, Nicolas. 2006. Presumption and the Practices of Tentative Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti, Eddo, and Sara Greco. 2019. Inference in Argumentation. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Kelly, Casey. 2020. Donald J. Trump and the rhetoric of ressentiment. Quarterly Journal of Speech 106: 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, Jennifer M. 2017. Racial figleaves, the shifting boundaries of the permissible, and the rise of Donald Trump. Philosophical Topics 45: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, Jennifer M. 2021. Racist and sexist figleaves. In The Routledge Handbook of Social and Political Philosophy of Language. Edited by Justin Khoo and Rachel Sterken. New York: Routledge, pp. 161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sbisà, Marina. 2013. Some remarks about speech act pluralism. In Perspectives on Pragmatics and Philosophy. Edited by Alessandro Capone, Franco Lo Piparo and Marco Carapezza. Cham: Springer, pp. 227–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sbisà, Marina. 2019. Varieties of speech act norms. In Normativity and Variety of Speech Actions. Edited by Maciej Witek and Iwona Witczak-Plisiecka. Leiden: Brill, pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, Oliver R. 2018. Symptoms of expertise: Knowledge, understanding and other cognitive goods. Topoi 37: 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, John R. 1969. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]