Abstract

In languages that have a definite article but no indefinite article, the definite article typically maps to definites, and the bare noun maps to indefinites. We investigate this mapping in Malagasy, which imposes an additional restriction: bare nouns cannot be subjects. We ask whether the subject can be interpreted as indefinite, given the obligatory nature of the article. We also look at DPs in other positions (direct object, clefted subjects) to determine whether the mapping between form and meaning is one-to-one. To answer these questions, we administered an on-line questionnaire that presented participants with the choice of the article or the bare noun in the different positions (subject, object, cleft) in contexts that favoured an indefinite/novel interpretation. As predicted, the article was obligatory in subject position, but disfavoured in the object and cleft position. These results confirm current descriptions in the literature. We compare these results with a similar case of definite article in indefinite nominals found in Italian and propose that the article does not carry definiteness features (at least in these cases) but overtly marks (abstract) Case assignment on subjects, while it can remain silent on objects.

1. Introduction

Determiner systems vary widely across languages. As discussed by Lyons (1999), some lack dedicated articles altogether (Japanese, Russian). Others have both definite and indefinite articles (Italian, English)1. A few have only indefinite articles (Turkish, Mam). Moreover, many have a dedicated definite article, but lack an indefinite (Hebrew, Irish). For the latter group of languages, the absence of an article (a bare noun) is therefore typically described as an indication of indefiniteness.

Malagasy (Austronesian) is an example of such a language: it has an article, ny, and no indefinite article. The literature describes ny as definite and bare nouns as indefinite. In other words, the variation between the two forms in (1) (ny mpivarotra ‘the merchant’ vs. mpivarotra ‘a merchant’) does not present any optionality but is assumed to serve a strict mapping between form and meaning, as indicated by the translation (note that Malagasy is VOS):2

| 1. | a. | nahita | ny | mpivarotra | aho tany | an-tsena |

| PST.AT. | see DET | merchant | 1SG PST.LOC | ACC market | ||

| b. | nahita | mpivarotra aho tany | an-tsena. | |||

| PST.AT.see merchant | 1SG PST.LOC | ACC market | ||||

| ‘I saw a merchant/some merchants at the market.’ | ||||||

Complicating this picture, however, is the fact that the article is obligatory in the subject position, as illustrated in (2) (Keenan 1976):3

| 2. | a. | lasa | ny | mpianatra |

| gone | DET | student | ||

| ‘The student(s) left.’ | ||||

| b. | *lasa mpianatra | |||

| gone student | ||||

| ‘A/some student(s) left.’ | ||||

The lack of optionality in subject position may either lead us to suppose that no true indefinite subject can be expressed in this language or that the interpretation of ny is optionally definite or indefinite in this position. Previous literature on the Malagasy article system (e.g., Fugier 1999; Law 2006; Keenan 2007; Paul 2009) has actually claimed that the latter is the case. This raises the issue as to which of two possible analyses is more apt to motivate this contrast: (i) the article ny is not a marker of (in)definiteness but overtly marks a different feature (e.g., abstract Case) mandatorily when the DP is in subject position and optionally elsewhere; or (ii) there are two nys, one is ambiguously definite or indefinite and is marked to appear in subject position; the other is unambiguously definite and is marked to appear elsewhere.4

In this paper, we question the mapping between form and meaning underlying hypothesis (ii) and support hypothesis (i) with the results of an on-line questionnaire, a methodology that has not been previously used to collect native speakers’ intuitions of the interpretative properties of ny in Malagasy. We also check the distribution of ny in clefted subjects, which have not been discussed in the literature. We show that the article in the subject position (where the article is obligatory) is compatible with an indefinite (novel) reading, while novel contexts strongly favour bare nouns in the object position (where the article is optional). The cleft position, where articles are also optional, also favours bare nouns in novel contexts, but there is a slightly higher occurrence of the article than in the object position.5

The questionnaire has been inspired by recent research on Italian indefinite objects carried out by Cardinaletti and Giusti (2016, 2018, 2020) that shows that the definite article can appear in indefinite nominals in the object position alternating with bare nouns, giving rise to diatopic variation. Their analysis of the definite article with indefinite interpretation is based on Giusti’s (2015) hypothesis that conceives the Italian article as a marker of nominal features (gender, number and abstract Case) that is required when the silent definite determiner is merged in SpecDP and is optional when SpecDP is filled with the silent indefinite determiner. The diatopic variation between indefinite articles and bare nouns across regional varieties of Italian regards the rate of speakers’ preferences between the two forms; it thus represents a clear case for true optionality.

This paper is organized as follows. We first provide relevant background on the syntax of Malagasy and the distribution of articles in Section 2, where we spell out our research questions. Section 3 describes the online questionnaire and the participants. The results are presented and discussed in Section 4. Section 5 makes a comparison with the Italian article and spells out our formal analysis. Section 6 concludes, observing that, unlike what is observed in Italian, there is no true optionality in Malagasy: where variation in form is possible (the presence vs. absence of the article); this leads to a difference in meaning.

2. Background on Malagasy

Malagasy is a Western Austronesian language spoken in Madagascar and the diaspora by over 20 million people. The unmarked word order is VOS, and the language is strongly head-initial. One other aspect of Malagasy syntax that will be important to the understanding of the data is the voice system. Verbs carry morphology that indicates the semantic role of the subject. In the examples below, the verb (derived from the root sarona ‘cover’) is marked for the different voices and a different element appears in the clause-final subject position. When the verb is marked with ActorTopic morphology, the agent is the subject (3.a); with ThemeTopic, the theme is the subject (3.b); and with CircumstantialTopic, some other argument is the subject (in (3.c) it is an instrument). The underlined element in the English translation indicates which argument is the subject in Malagasy.

| 3. | a. | manarona | ny | laoka | amin’ | ny | lovia | aho |

| AT.cover | DET | sauce | P | DET | plate | 1SG | ||

| ‘I cover the sauce with the plate.’ | ||||||||

| b. | saronako | amin’ | ny | lovia | ny | laoka | ||

| TT.cover.1SG | P | DET | plate | DET | sauce | |||

| ‘I cover the sauce with the plate.’ | ||||||||

| c. | anaronako | ny | laoka | ny | lovia | |||

| CT.cover.1SG | DET | sauce | DET | plate | ||||

| ‘I cover the sauce with the plate.’ (Rajemisa-Raolison 1966, p. 76) | ||||||||

Note that there is some debate in the literature over the nature of the clause-final position, where some researchers (e.g., Pearson 2005) prefer the term ‘trigger’ over ‘subject’. We set aside this debate as it is somewhat orthogonal to our research questions. All agree, however, that there is a dedicated, clause-final, syntactically prominent position (see Keenan 1976 for extensive discussion).

As noted in (2) above, subjects in Malagasy cannot be bare nouns. Objects, however, have no such restrictions, as in (1).6 While the article ny is often translated as a definite determiner, it has been shown by Fugier (1999); Law (2006); Keenan (2007) and Paul (2009) that this characterization is not accurate. Consider the example below:

| 4. | ka | nandositra | sady | nokapohiko | ny | hazo… |

| then | AT.run-away | and | TT.hit.1SG | DET | tree | |

| ‘Then I ran away and hit a tree…’ (Fugier 1999, p. 17) | ||||||

In (4), the subject of the second conjunct is ny hazo ‘the tree’ (as determined by the ThemeTopic morphology on the verb), but it is translated with ‘a tree’ as there is no salient tree in the discourse context, and the tree is not mentioned in the remainder of the text. Given examples such as (2), the question arises as to how to accurately characterize the meaning of ny.7

Similar issues arise with articles in object position. Although bare nouns are typically translated with indefinites, there are certain contexts where it is not clear that definiteness is the relevant notion, as in (5):

| 5. | a. | tia | boky | frantsay | aho | |

| like | book | French | 1SG | |||

| ‘I like French books.’ | ||||||

| b. | tia | ny | boky | frantsay | aho | |

| like | DET | book | French | 1SG | ||

| ‘I like French books.’ (Rajaona 1972, p. 432) | ||||||

In Rajaona’s discussion of these examples, he suggests that the presence of the article ny in (5.b) signals an implicit opposition with other kinds of books, books not written in French. The example in (5.a), on the other hand, is more neutral. In other words, the article can be associated with contrast. As discussed in Section 4, our results show the possible effect of contrast in clefts, which we describe next.

Similar apparent optionality of the article can be seen in the cleft, where the clefted constituent appears clause-initially, followed by the particle no. Only subjects (and some adjuncts) can cleft in Malagasy (Keenan 1976). However, unlike subjects in the canonical clause-final position, clefted subjects may be bare, as shown in (6).

| 6. | a. | mpianatra | no | lasa | |

| student | FOC | gone | |||

| ‘It’s a/some student(s) who left.’ | |||||

| b. | ny | mpianatra | no | lasa | |

| DET | student | FOC | gone | ||

| ‘It’s the student(s) who left.’ | |||||

Once again, it is not clear how the article (or the lack thereof) is interpreted in clefts. Moreover, this question has not been discussed in the previous literature. We note that the standard analysis of clefts in Malagasy treats the clefted DP as the matrix predicate (Paul 2001; but see Law 2007 for an alternative analysis). In other words, the examples in (6) are a kind of pseudo-cleft, such that (6.b) can be translated as ‘The one(s) who left is/are the student(s)’.

The question of how ny is interpreted has been discussed by other researchers. While Law (2006) simply asserts that subjects with ny can be interpreted as indefinite, Fugier (1999) and Keenan (2007) present examples from texts that support the indefinite (novel) reading. Paul (2009) builds on this literature and arrives at the following conclusions based on naturally occurring examples and elicited felicity judgements. First, in subject position, because the article is obligatory, it allows for a range of interpretations, including both novel and familiar readings. Second, in object position, the article is optional and therefore associated with a fixed interpretation. In particular, the presence of the article gives rise to a familiar reading (previously mentioned or discourse salient). The absence of the article, on the other hand, leads to novel (new) interpretations. She does not, however, discuss the interpretation of clefted DPs.

With respect to the theme of this special issue, Malagasy is of interest in that it displays a case for variation in the occurrence of bare nouns (impossible in subject position, possible in object and clefted subjects) and a case for optionality of the article (in object and cleft position), which is traditionally related to different interpretations. In this paper, we try to answer the following three empirical questions:

- Given that the article is obligatory in subject position, can the DP be interpreted as novel/indefinite?

- Given that the article is optional in both the object and cleft position, is there a difference in the distribution of the article in these contexts when the context facilitates an indefinite interpretation?

- If there is optionality in article use in indefinite contexts, can it be attributed to linguistic or social factors?

3. Methodology

The questionnaire was created using the Qualtrics8 XM Platform™ (versions September–October 2021) and distributed to contacts in the Malagasy community in Madagascar, France and Canada. It included a few demographic questions and the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP) adapted for Malagasy—French bilinguals (Birdsong et al. 2012). The core of the questionnaire consisted of 24 pairs of test items (4 count nouns + 4 mass nouns) * 3 (object, subject, cleft) + 16 distractors.9 All test items presented pairs of sentences, one with the article, one without, and a third option “neither of these”. Some of the distractors also involved the presence of the article, while others showed alternations in accusative case marking (which is obligatory with proper names and kinship terms, optional with demonstratives and null with other DPs). Participants were asked if they might hear such sentences in Malagasy (“Indiquez si on pourrait entendre les phrases suivantes en malgache”). If they chose both sentences, they were further asked if there was a difference between the two and what that difference might be.

Examples of the test sentences are provided below—recall that Malagasy is VOS. Note that in (8), the verb is in the non-active form (glossed as TT—Theme Topic) for the relevant DP to be a subject. The first sentence provides the context, typically a question. The second sentence is the target sentence that participants were asked to judge. The participants saw both versions of the reply—one with the article and one without.

| 7. | Object Position | |||||||

| a. | Namafa | inona | ianao? | |||||

| PST.AT.wipe | what | 2SG | ||||||

| Namafa | (ny) | rano | aho. | |||||

| PST.AT.wipe | DET | water | 1SG | |||||

| ‘What did you wipe up? I wiped up (the) water.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Nametraka inona | tao | anatin’ | ny | harona | ianao? | ||

| PST.AT.put what | PST.LOC | in | DET | basket | 2SG | |||

| Nametraka (ny) | akondro | tao | anatin’ | ny | harona | aho. | ||

| PST.AT.put DET | banana | PST.LOC | in | DET | basket | 1SG | ||

| ‘What did you put in the basket? I put (the) bananas in the basket.’ | ||||||||

| 8 | Subject Position | |||||||

| a | Nahoana | no | madio ny | gorodona? | ||||

| why | FOC | clean DET | floor | |||||

| Nofafako | (ny) | rano. | ||||||

| PST.TT.wipe.1SG | DET | water | ||||||

| ‘Why is the floor clean? I wiped up (the) water.’ | ||||||||

| b | Nahoana | no | mavesatra | ny | harona? | |||

| why | FOC | heavy | DET | basket | ||||

| Napetrako | tao | anatin’ | ny | harona | (ny) | akondro. | ||

| PST.TT.put | PST.LOC | in | DET | basket | DET | banana | ||

| ‘Why is the basket heavy? I put (the) bananas in the basket.’ | ||||||||

| 9. | Cleft | |||||||||

| a | Namafa | menaka | ve | ianao? | ||||||

| ST.AT.wipe | oil | Q | 2SG | |||||||

| Tsia, | (ny) | rano | no | nofafako. | ||||||

| no | DET | water | FOC | ST.TT.wipe.1SG | ||||||

| ‘Did you wipe up oil? No, it’s water that I wiped up.’ | ||||||||||

| b | Nitahiry | ovy | tao | anatin’ | ny | kitapo | ve | ianao? | ||

| PST.AT.keep | potato | PST.LOC | in | DET | bag | Q | 2SG | |||

| Tsia, | ny | voanio | no | noteriziko | tao | anatin’ | ny | kitapo | ||

| no | DET | coconut | FOC | PST.TT.keep | PST.LOC | in | DET | bag | ||

| ‘Did you keep potatoes in the bag? No, I kept coconuts in the bag.’ | ||||||||||

As can be seen in these examples, the context is intended to facilitate an indefinite or novel interpretation of the DP. With respect to our research questions above, the test is designed to fulfill the following expectations:

- a. Consistent choice of the article in subject position would confirm that the article is compatible with an indefinite interpretation.b. Optionality of the article in subject position or a high rate of ‘neither of these’ would suggest that the article can only convey definite (or familiar) interpretation.

- a. Consistent choice of bare nouns in object or cleft position would suggest that the article specializes for definiteness (or familiarity) when it is in competition with bare nouns.b. Optionality in the distribution of the article in object or cleft position would suggest true optionality of meaning of the article.

- a. In case any optionality is present, it may depend on linguistic features (not just subject, object, or clefted position but also mass vs. count nouns).b. Or it may depend on sociolinguistic factors (age, education, provenance or language dominance).

There were 28 participants, 15 female, 13 male. They range from 18 to 73 years of age, with 10 in the 18–31 range, 11 in the 31–51 range and 7 in the 51–75 range. All of them are bilingual Malagasy–French, and French was the language used in the questionnaire for instructions and for the administration of the BLP. Most participants are highly educated (9 with Ph.D.s or higher, 10 with master’s degrees), and only one did not complete high school. Although the participants represent diverse regions in Madagascar, 12 are from the central highlands (the region around the capital, Antananarivo), and 10 are from the northwest. This geographic distribution is not surprising, given how the questionnaire was distributed (mostly via contacts in the capital). While there are regional dialects, the items were formulated in Official Malagasy. As for the BLP, there were roughly 5 groups: 2 French-dominant, 3 balanced, 7 slightly Malagasy-dominant, 11 moderately Malagasy-dominant and 5 strongly Malagasy-dominant.

4. Results and Discussion

Due to the limited number of participants, combined with the high number of relevant factors, we limit ourselves to a descriptive analysis. The consistent results permit us to draw generalizations and provide answers to the empirical questions above. The results of the study confirm the predictions based on the previous literature. Of all the factors considered, the one that determined the acceptability of the article was argument position (subject, object, cleft). More specifically, a bare noun in subject position was accepted only 6% of the time, while in object position, it was accepted 89% of the time. Interestingly, bare clefted DPs were accepted only 75% of the time. Somewhat surprisingly, only two participants displayed any form of optionality, but they did so abundantly (66% of the times, corresponding to object and cleft positions). In other words, they accepted both the bare noun and the DP headed by an article; 12 participants clicked on the “neither of these” button, thereby ruling out both the bare noun and the DP headed by the article, for a total of 25 times (approximately the 3.7% of the rated items), among these, most involved the subject position. No other factors played a role in the results. In other words, the sociolinguistic factors such as age, region, BLP group and the other linguistic factor, the mass versus count distinction, did not affect the choice between an overt article and a bare noun (but see below for some marginal effects). The results suggest that the Malagasy article is unmarked for definiteness (it is neither definite nor indefinite). To avoid ambiguity, speakers use bare nouns for novel reference in positions where they are allowed.

The overwhelming preference for the bare noun (89%) in object position suggests that there is no real optionality: the presence or absence of the article changes meaning. The two participants who displayed apparent optionality (choosing both the bare noun and the noun with the article) highlighted a different interpretation for the two choices, showing that they attributed a familiar interpretation in the case of the presence of the article. This was indicated by their consistent positive answer to the question “Is there a difference in meaning between the two choices?” and their further comments.

Turning to clefts, the bare noun is preferred (75%), but there are more instances of the article than with objects. As with objects, the bare noun is predicted to be preferred due to the novel interpretation. Moreover, Paul (2001) has argued that the clefted element is in fact a predicate and not the subject. As a predicate, which is non-argumental and non-referential, the nominal expression is preferentially bare. The example in (10.a) illustrates a context where the article is incompatible with a nominal predicate, while (10.b) shows that some nominal predicates do allow an overt article. We do not attempt to analyze this restriction, but we take it to show that the clefted element, as a predicate, is compatible with an article.

| 10. | a. | (*Ny) filoha Rabe. |

| DET president Rabe | ||

| ‘Rabe is (the) president.’ | ||

| b. | (Ny) vadiko ilay olona teto omaly. | |

| DET spouse.1SG DEF person PST.here yesterday | ||

| ‘The person who was here yesterday is my spouse.’ (Rajaona 1972, p. 68) |

On the other hand, given that the cleft introduces a contrast (contrastive focus; see Paul 2001) and given Rajaona’s suggestion that the article is associated with contrast, the slightly higher rate of acceptability of the article (25%) suggests that a nominal predicate projects up to the DP-layer in which the discourse feature [+contrast] is expressed by the article. As noted by a reviewer, a textual study of clefts and the occurrence of overt articles could be revealing. We leave such a study for future research.

Turning now to subjects, while the low rate of acceptance of the null article is expected (6%), it is in fact predicted that the acceptance rate should be zero, given the description in the literature. Due to the methodology used to collect the data, this may well be due to “noise”, errors in ticking the intended button or in reading the sentence (the participants could not go back and change their answers).

However, a deeper observation suggests that there may be some generalizations to be noted. A total of nine participants accepted bare nouns in the subject position. Six of these accepted one instance, one participant accepted two instances, and two participants accepted three. As for these nine participants, they are evenly divided between the two genders and represent a range in terms of age, education and BLP. Of the accepted instances of bare noun subjects, most were mass nouns, such as in (11.b), where the subject vary ‘rice’ is underlined (accepted by four different participants):

| 11. | a. | Nataonao | inona | ilay | gony | teto? | |

| PST.TT.do.2SG | what | DEF | sack | PST.LOC | |||

| ‘What did you do with the sack?’ | |||||||

| b. | Notehiriziko | tao | anatin’ | ny | gony | vary. | |

| PST.TT.keep.1SG | PST.LOC | in | DET | sack | rice | ||

| ‘I kept rice in the sack.’ | |||||||

We leave this puzzle for future qualitative research10.

Let us now discuss the answers of the two participants who apparently allowed for optionality 66% of the time, notably always in object and cleft positions and never in subject position. In their comments, they point out that the use of the article indicates that the referent of the noun is known; that is, they attribute familiar interpretation to the article and novel interpretation to the bare nouns. Thus, even if our contexts facilitated a non-familiar interpretation, as confirmed by the results of the other 23 participants, these two participants (and only these two) accommodated the context to make the article acceptable.

Finally, let us comment on the 25 choices for the “neither of these” option, which were rather evenly distributed across 12 participants. For these participants, neither the bare noun nor the DP headed by the article ny were acceptable. The subject position covers 16 of the 25 cases. This result may suggest that for these speakers the presence of the article conveys a familiar interpretation, which is at odds with the context given. Moreover, only in this case is a mass-count distinction detected: most of these cases involve mass nouns. This effect appears related to a preference for null determiners with mass nouns, already noted above with the very marginal acceptability of zero determiners in subject position. However, this preference for a null article with mass nouns is in conflict with the restriction against bare nouns in subject position. It is perhaps this conflict that leads to participants rejecting both sentences. Whether this effect is real needs to be further investigated with qualitative research. Alternatively, it may be the case that our constructed sentences were unacceptable to the participants for reasons unrelated to the presence or absence of the article.

Returning to the research questions above, our results comply with the expectations spelled out in (i.a) and (ii.a) supporting the hypothesis that the article per se does not convey definite or indefinite interpretation but some other nominal features. This is supported by the fact that the article is judged as grammatical in subject position 96% of the time in contexts in which the subject is a novel indefinite and by the fact that bare nouns in these contexts are not chosen 94% of the time. Our data also confirm that the article appears in object position only to convey a familiar interpretation, and for this reason it is only selected 11% of the time in some cases as a possible alternative of the bare noun, but only if the participant has operated an accommodation in the interpretation of the context making a familiar object acceptable. Finally, our data confirm the possibility for some speakers to interpret the article as a marker of contrast appearing on cleft nominals, which according to Paul (2001) are not arguments (not true subjects) but the predicate of the cleft sentence. In the next section, we present a syntactic hypothesis originally proposed for Italian that can account for this variation in the interpretation of articles and bare nouns.

5. A Macroparametric Perspective

The contexts presented in the questionnaire all facilitate “uncontroversial indefinites” in the sense of Braşoveanu and Farkas (2016) or “core indefinites” in the sense of Giusti (2021) and Cardinaletti and Giusti (2018, 2020), that are non-specific, unquantified weak indefinites with no further qualification (e.g., free choice function). This type of indefinite usually lacks a determiner in any language that allows for bare nominals. Take, for example, Dutch, Spanish and French. As observed by Delfitto and Schroten (1991), while Dutch (like all Germanic languages) allows for bare indefinite mass and plural count nouns across the board, in Spanish they are excluded in preverbal subject position, while in French they are totally ungrammatical (12)–(13):

| 12. | a. | Ik heb studenten in het gebouw gezien. | (Dutch) |

| b. | Yo he visto estudiantes en el edificio. | (Spanish) | |

| c. | *J’ai vu étudiants dans l’édifice. | (French) | |

| ‘I saw students in the building.’ |

| 13. | a. | Studenten hebben het gebouw bezet. | (Dutch) |

| b. | *Estudiantes han ocupado el edificio. | (Spanish) | |

| c. | *Étudiants ont occupé l’édifice. | (French) | |

| ‘Students occupied the building.’ |

Note that in the three languages, the ungrammatical examples are rescued by overt indefinite determiners (the plural of ‘one’ in Spanish, which only appears with count nouns, and the partitive article in French, which is possible for both mass and count nouns). In Romance languages, the overt indefinite determiner can also appear where the bare noun is possible, conveying a different type of indefinite interpretation (either quantitative or specific), roughly corresponding to weak some (or s’m) in English (14), while the interpretation is not necessarily quantitative or specific in subject position (15). In (14)–(15), we put Italian into the picture, which displays a partitive article (like French) which is, however, optional, competing with bare nouns in object position (like Spanish):

| 14. | a. | Ho visto (degli) studenti nel palazzo. | (Italian) |

| b. | Yo he visto (unos) estudiantes en el edificio. | (Spanish) | |

| c. | J’ai vu *(des) étudiants dans l’édifice. | (French) | |

| ‘I saw (some) students in the building.’ |

| 15. | a. | *(Degli) studenti hanno occupato il palazzo. |

| b. | *(Unos) estudiantes han ocupado el edificio. | |

| c. | *(Des) étudiants ont occupé l’édifice. | |

| ‘(Some) students occupied the building.’ |

The notable parallel with the Malagasy data above is the fact that in subject position a determiner is mandatory in the three Romance languages. Furthermore, it does not trigger the “enriched” interpretation that it would have in object position, where it competes with a bare noun that is in object position in Italian (14.a) and Spanish (14.b). There are many independent differences, however, as for example, the lack of number marking on count nouns and the lack of an ad hoc overt indefinite determiner in Malagasy.

This latter property reminds us of the possibility in Italian and Italian dialects to have the definite article with the function of “core indefinite” interpretation (here glossed as ART) in many dialects and regional varieties that do not admit bare nouns, as discussed by Cardinaletti and Giusti (2016, 2018, 2020) and Giusti (2021), such as the Anconetano examples in (16):

| 16. | a. | Ieri | non ho | magnato | le | patate (Anconetano) |

| ‘Yesterday | I didn’t | eat | ART | potatoes’. | ||

| b. | Ieri | non ho | bevuto | ‘l | vì. | |

| ‘Yesterday | I didn’t | drink | ART | wine.’ |

In Anconetano, the partitive article is only available with plural count nouns that have a specific interpretation. Thus (17.a) can only mean that there were potatoes that I did not eat, while (17.b) is ungrammatical (or a literal translation from Italian):

| 17. | a. | Ieri | non ho | magnato | dele | patate (Anconetano) |

| Yesterday | not have.1P.SG | eaten | PART.ART | potatoes | ||

| ‘Yesterday there were potatoes that I didn’t eat’. | ||||||

| b. | *Ieri | non ho | bevuto | del | vì. | |

| Yesterday | not have.1P.SG | drunk | PART.ART | wine | ||

| ‘Yesterday I didn’t drink (some) wine. | ||||||

Note that standard Italian, which displays both bare nouns and the partitive article, can also have the definite article with indefinite interpretation in object position, as in (18):

| 18. | a. | Ieri | non ho | mangiato | (le/delle) | patate (Standard Italian) |

| ‘Yesterday | I didn’t | eat | ART/PART.ART | potatoes’. | ||

| b. | Ieri | non ho | bevuto | (il/del) | vino. | |

| ‘Yesterday | I didn’t | drink | ART/PART.ART | wine.’ |

Italian is therefore more similar to Malagasy than any other Romance language in that it has an article that is underspecified for definiteness. Furthermore, as theorized by Cardinaletti and Giusti (2018, 2020), in those contexts and varieties in which the three possibilities (bare noun, ART or PART.ART) are available, one expresses “core indefiniteness”, and the others specialize for enriched interpretation. However, there is a large margin for true optionality, as further argued by Giusti (2021) for Italian and Lebani and Giusti (2022) for two northern Italian dialects.

The comparison with Italian may seem surprising, as noted by a reviewer, but is warranted based on the initial points of comparison, as just noted. Moreover, extending the analysis of Italian (discussed below) to a typologically distinct language such as Malagasy provides extra support for this approach. On the contrary, a comparison with other Austronesian languages would not be fruitful because many of the more familiar Austronesian languages lack articles. Some, such as Tagalog, have a particle within the noun phrase that marks Case, not definiteness (Collins 2019). Others, such as Indonesian, optionally employ demonstratives or possessive marking to explicitly indicate definiteness (Sneddon 1996).

The syntactic analysis for the three indefinite determiners of Italian and Italian dialects is based on Giusti’s (1997, 2002, 2015) claims that: (i) articles are not endowed with semantic features but fill the head of the highest nominal projection with nominal features, which in Italian are gender, number and abstract Case; (ii) the determiner providing the referential properties of the nominal expression is merged in SpecDP; and (iii) abstract Case can differentiate definite and indefinite nominals, thus the alternation of indefinite bare nouns and definite articled nouns in object position is taken as an instance of differential object marking.11

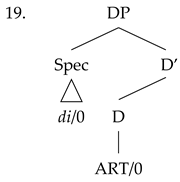

Both elements can be overt or covert, as depicted in (19). The indefinite determiner that occurs with mass and plural count nouns in SpecDP is di, an uninflected form which is the formative of the partitive article:

This structure derives the four determiners in (20), three of which can appear in object position (20.a–c); the fourth only appears in dislocated position resumed by the partitive clitic ne, (20.d’, which replicates on of the possibilities in (ii) fn. 11):

| 20. | a. | Ho raccolto 0 fragole. | Spec and D covert | |||

| b. | Ho raccolto le fragole. | Spec covert; D overt | ||||

| c. | Ho raccolto delle fragole. | Spec and D overt | ||||

| d. | *Ho raccolto di fragole. | Spec overt; D covert | ||||

| ‘I have.1P.SG picked 0/ART/PART.ART/DI strawberries.’ | ||||||

| d′. | Di | fragole, | ne | ho | raccolte. | |

| DI | strawberries, | PART.CL | have.1P.SG | picked. | ||

| ‘I picked strawberries.’ | ||||||

Applying this framework to Malagasy, we assume that the article ny is merged in D and bears no semantic features. We also assume that Malagasy (like Italian) has two null determiners that can appear in Spec, DP: one indefinite and one definite. Just as in Italian, the indefinite null determiner normally combines with a covert D, giving rise to a bare noun. In subject position, however, the indefinite determiner must combine with overt ny (in D). Combination with overt D also occurs when the null indefinite determiner in SpecDP is enriched with contrast features. Moreover, like Italian, the definite null determiner must be in Spec-Head concord with an overt D, whatever grammatical function is attributed to the nominal expression.

Whether the determiner is definite or indefinite, insertion of ny is thus reduced to a matter of realization of nominal features in D depending on the requirements of the null determiner in SpecDP, which in turn may be different in different argument positions. It is therefore only indirectly related to interpretation. What exactly these features are may be easier to determine in Italian where gender and number are overt on the article. Moreover as observed in fn 11, abstract Case on the DP can be diagnosed by the morphology of the resumptive clitic. It is more difficult to establish in Malagasy in which ny is uninflected. Since our analysis is set in the generative perspective which assumes universal properties to be realized in different languages by different morphological devises obeying language specific parameters, we propose that in Malagasy bare vs. overt D in object position is a sort of DOM, marking definite DP with overt Case (ny in D) and leaving indefinite DPs bare. In subject position all DPs, definite or indefinite must have overt Case in D.

This accounts for the otherwise surprising contrast between “core indefinites” in subject position, which are perfectly grammatical with ny and ungrammatical as bare nouns, and “core indefinites” in object or cleft position, which are perfectly grammatical with bare nouns and do not allow for ny insertion, which would signal the presence in Spec of the null definite determiner or (though only marginally) of a contrast feature, as we saw for clefts.

6. Conclusions

This paper has used an online questionnaire to collect data about the distribution of nouns with and without articles in “core indefinite” contexts in three syntactic conditions: subject, object and cleft position. The questionnaire was also designed to control for the mass-count distinction. We have shown that the distribution and interpretation of articles and bare nouns in Malagasy correspond to current descriptions in the literature (Fugier 1999; Law 2006; Keenan 2007; Paul 2009). In the subject position, the article allows indefinite (novel) interpretations. In the object position, novel contexts favour a bare noun. The interpretation of the article in clefts, however, has never been directly addressed in the literature. Our results suggest that the novel context still favours a bare noun in clefts, suggesting that the clefted nominal is not the subject of the cleft construction but the predicate. The slightly higher rates of the article in this position were related to the contrast feature inherent in a cleft. Our syntactic proposal involved two structural positions, the specifier and the head of the highest functional projection in the nominal domain. The specifier hosts operators that are null; the definite and indefinite operators only differ in their requirement to concord with a covert or overt D. Independently of this, D must be filled in subject position. The two conditions that regulate the variation between overt and covert D, therefore, do not give rise to optionality in the Malagasy determiner system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P. and G.G.; formal analysis, I.P., G.G. and G.E.L.; investigation, I.P.; methodology, G.G. and G.E.L.; writing—original draft, I.P. and G.G.; writing—review & editing, I.P., G.G. and G.E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Insight grant (435 2019 0581) to Ileana Paul.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Western University Non-Medical Research Ethics Board on 5 May 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | As pointed out by Lyons (1999, pp. 89–106), indefinite articles are often markers of cardinality and may in fact only express indefiniteness indirectly. For a typological overview of definite and indefinite articles in the languages of the world, we refer the reader to Dryer (2013a, 2013b). |

| 2 | Unless otherwise indicated, examples come from our own fieldnotes. Note that nouns in Malagasy are underspecified for number (Paul 2012): there is no number inflection on nouns or the article ny. Demonstratives and most pronouns, however, carry number morphology. Glosses follow the Leipzig glossing conventions, with the following additions: AT—ActorTopic, TT—ThemeTopic, CT—CircumstantialTopic. |

| 3 | As noted by a reviewer, the DP in an existential construction can be bare, but as shown by Paul (1998, 2000) and Law (2011), this DP is not in the subject position. |

| 4 | Both definiteness and indefiniteness are controversial notions, as observed by Abbott (2014) for definiteness and by Braşoveanu and Farkas (2016) for indefiniteness. Defining these notions here is not crucial in that our focus is on the variation between bare nouns and articled nouns in object position as opposed to subject position. Whatever notion of definiteness and indefiniteness is taken, the research question regards the different mapping of form and meaning in the two argument positions. |

| 5 | The situation for non-core arguments is slightly complicated. As described in Paul (2009), some prepositions obligatorily select for a bare noun while others select for a DP headed by an article. In both instances, the DP can be interpreted as novel or familiar. We did not test these cases in the present questionnaire. |

| 6 | It has at times been claimed in the literature that objects must be bare and cannot take the article ny (e.g., Zribi-Hertz and Mbolatianavalona 1999). We have not observed this restriction in our own fieldwork. |

| 7 | Malagasy has an additional article, ilay, that is strictly anaphoric (“aforementioned”). We set it aside here. |

| 8 | Qualtrics and all other Qualtrics product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 21 May 2022). |

| 9 | An anonymous reviewers asks why we controlled for count versus mass. While in Malagasy, the distribution of the article does not at first glance appear to be sensitive to the count-mass distinction, as in fact is the case in other languages, including Italian, with which we will compare it, we decided it would be prudent to verify this first impression. |

| 10 | The example in (12.b) allows for a different parse, where the subject is null (pro = vary ‘rice’) and the noun vary is treated as a modifier of gony ‘sack’ (‘I kept (it) in the rice sack’). Not all the examples allow for this alternative structure, however. |

| 11 | There is abundant literature on the relation between case morphology and (in)definiteness. For recent discussion we refer the reader to Stark and Ihsane (2020), Sleeman and Giusti (2021) and Sleeman and Luraghi (2022). Italian patterns with French and Catalan in having a special clitic, ne/en, for indefinite nominals that alternates with accusative clitics or nominative pro that resume definite and specific nominals. The alternation in the resumptive pronouns can be taken as evidence that the partitive/accusative alternation also distinguishes different kinds of indefiniteness, since indefinite nominals introduced with an overt determiner (di + ART or just ART) in Italian are resumed by an accusative (i), while bare nominals or bare di nominals are resumed by ne (ii):

‘I didn’t pick (any) strawberries.’ The comparison in (i)–(ii) shows that in Italian an overt ART (with or without di) corresponds to accusative while covert ART (also with or without di) corresponds to ne. In French and Galloitalic dialects overt de (with overt or covert D) corresponds to ne. This suggesting that the features in the DP that are related to the morphology of the determiner include abstract case, which is overtly expressed on clitics. |

References

- Abbott, Barbara. 2014. The indefiniteness of definiteness. In Frames and Concept types. Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy. Edited by Thomas Gamerschlag, Doris Gerland, Rainer Osswald and Wiebke Petersen. Cham: Springer, vol. 94, pp. 323–41. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar]

- Braşoveanu, Adrian, and Donka Farkas. 2016. Indefinites. In The Cambridge Handbook of Formal Semantics. Edited by Maria Aloni and Paul Portner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 238–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2016. The syntax of the Italian determiner dei. Lingua 181: 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2018. Indefinite determiners: Variation and optionality in Italo-Romance. In Advances in Italian Dialectology. Sketches of Italo-Romance Grammars. Edited by Roberta D’Alessandro and Diego Pescarini. Amsterdam: Brill, pp. 135–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Giuliana Giusti. 2020. Indefinite determiners in informal Italian. A preliminary analysis. Linguistics 58: 679–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, James. 2019. Definiteness determined by syntax. A case study in Tagalog. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 37: 1367–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfitto, Denis, and Jan Schroten. 1991. Bare plurals and the number affix in DP. Probus 3: 155–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, Matthew S. 2013a. Definite articles. In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Available online: http://wals.info/chapter/37 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Dryer, Matthew S. 2013b. Indefinite articles. In The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Edited by Matthew S. Dryer and Martin Haspelmath. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Available online: http://wals.info/chapter/37 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Fugier, Huguette. 1999. Syntaxe Malgache. Louvain-la-Neuve: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, Giuliana. 1997. The categorial status of determiners. In The New Comparative Syntax. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. London: Longman, pp. 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, Giuliana. 2002. The functional structure of noun phrases: A bare phrase structure account. In Functional structure in DP and IP. [The Cartography of Syntactic Structures 1]. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 54–90. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, Giuliana. 2015. Nominal Syntax at the Interfaces. A Comparative Analysis of Languages with Articles. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, Giuliana. 2021. A protocol for indefinite determiners in Italian and Italo-Romance. In Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article. [Syntax and Semantics 43]. Edited by Tabea Ihsane. Amsterdam: Brill, pp. 262–300. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, Edward. 1976. Remarkable subjects in Malagasy. In Subject and Topic. Edited by Charles Li. New York: Academic Press, pp. 249–301. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, Edward. 2007. The definiteness of subjects and objects in Malagasy. In Case and Grammatical Relations. Edited by G. Corbett and M. Noonan. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 241–61. [Google Scholar]

- Law, Paul. 2006. Argument-marking and the distribution of wh-phrases in Malagasy, Tagalog and Tsou. Oceanic Linguistics 45: 153–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Paul. 2007. The syntactic structure of the cleft construction in Malagasy. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 765–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Paul. 2011. Some syntactic and semantic properties of the existential construction in Malagasy. Lingua 121: 1588–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebani, Gianluca, and Giuliana Giusti. 2022. Indefinite determiners in two northern Italian dialects. Isogloss 8: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Christopher. 1999. Definiteness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Ileana. 1998. Existentials and partitives in Malagasy. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 43: 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Ileana. 2000. Malagasy existentials: A syntactic account of specificity. In Formal Issues in Austronesian Linguistics. Edited by I. Paul, V. Philips and L. Travis. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Ileana. 2001. Concealed pseudo-clefts. Lingua 111: 707–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Ileana. 2009. On the presence versus absence of determiners in Malagasy. In Determiners: Universals and Variation. Edited by Jila Ghomeshi, Ileana Paul and Martina Wiltschko. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 215–42. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Ileana. 2012. General number and the structure of DP. In Count and Mass Across Languages. Edited by Diane Massam. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, Matt. 2005. The Malagasy subject/topic as an A-bar element. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 23: 381–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaona, Simeon. 1972. Structure du Malgache: Etude des formes prédicatives. Fianarantsoa: Librairie Ambozontany. [Google Scholar]

- Rajemisa-Raolison, Régis. 1966. Grammaire Malgache. Fianarantsoa: Librairie Ambozontany. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman, Petra, and Giuliana Giusti, eds. 2021. Partitive Determiners, Partitive Pronouns and Partitive Case. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman, Petra, and Silvia Luraghi. 2022. Crosslinguistic variation in partitives: An introduction. Linguistic Variation. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, James. 1996. Indonesian. A Comprehensive Reference Grammar. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Elisabeth, and Tabea Ihsane. 2020. Special Issue: Shades of partitivity: Formal and areal properties. Linguistics 58: 605–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zribi-Hertz, Anne, and Liliane Mbolatianavalona. 1999. Towards a modular theory of linguistic deficiency: Evidence from Malagasy personal pronouns. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 17: 161–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).