Abstract

A comparison of emerging signed languages and creole languages provides evidence that, when language is emerging, it prioritizes marking the novelty of information; is readily recursive; favors the manner of action (aspect) over the time of action (tense); develops inflection readily only in a visual, as opposed to aural, mode; and develops derivational opacity only as the result of drift over long periods of time.

1. Introduction

While there has been some controversy since the turn of this century as to whether it is definitional to creole languages that they emerge from pidgin varieties, it is empirically documented that certain creoles have done so. Examples include the Bislamic creoles such as Tok Pisin (Mühlhaüsler 1986), the central African creole Sango (Samarin 2000), and Hawaiian Creole English (Roberts 2000). There are also traits in all creole languages beyond these that indicate ancestry either in pidginization or other degrees of the interrupted transmission of language (cf. McWhorter 2018). It is therefore possible to reconstruct structural developments typical of the pathway from pidgin to a full language.

In the tradition of previous studies such as Fischer (1978) and Meier (1984), but utilizing data and perspectives developed since, this study will compare the manifestation of six grammatical features in creoles and signed languages. The features will be six that have been widely addressed in the literature on the pathway from pidgin to creole. The goal will be to establish both parallels and contrasts between these processes in the two types of language, in order to assess which processes may be universal to the language competence and which are conditioned by the difference between the spoken and manual modalities.

The presentation will proceed upon certain assumptions about creole languages, which follow.

- (1)

- Creoles are the product of broken transmission of a significant degree, such that creole genesis constitutes the re-emergence of a language. Creole genesis is not solely a combinatory process of hybridization between languages, within which second-language acquisition plays but a marginal role (cf. Mufwene 2001).

- (2)

- The traditional classification of Pacific varieties such as Tok Pisin as “pidgins” born of a process distinct from the one that yielded the Atlantic “creoles” is artificial. Tok Pisin and its sister languages have now been spoken natively for generations and qualify as creole languages having developed in an analogous fashion to languages such as Papiamentu and Haitian Creole. Any apparent genealogical difference between the Pacific and the Atlantic varieties is due only to the fact that for the latter, the genesis process is largely lost to written history.

- (3)

- Creoles constitute a synchronic type of language. This is not in the presence of “creole” features unknown in other languages, but in the combined absence of certain features, at least some of which are always present in older languages not born of severely interrupted transmission (cf. McWhorter 1998, 2018).

(General statements about creole traits are based on the author’s knowledge, confirmed by consultation with the Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures Online [ApiCS].)

2. Word Order

Neither creoles nor signed languages offer direct evidence of one word order being fundamental to language, either diachronically or synchronically. However, signed languages possibly lend more insight on this issue than creoles.

2.1. Word Order in Creoles

It has often been claimed that creolization yields SVO order regardless of the word orders of the source languages, with this suggesting that SVO is language’s fundamental word order in, for example, Universal Grammar (cf. Bickerton 1981). An especially interesting piece of evidence for this idea is Berbice Creole Dutch, with SVO order despite its main and possibly only substrate language being the SOV African language Ijo, and even its lexifier language Dutch being partly SOV.

However, in a broader view, creoles’ word order is determined considerably by the degree of contact with their source languages after genesis. For example, the Indo-Portuguese creoles have emerged with Portuguese’s SVO despite the SOV order of their Indo-Aryan and Dravidian substrate languages. However, Portuguese itself has exerted heavy pressure upon many of them during their lifespans (for example, Korlai Portuguese emerged amidst Catholic religious instruction (Clements 1996)), and notably, the Korlai variety has moved towards SOV as it is increasingly used only among speakers of its substrate Marathi. These creoles have offered little indication of what a “basic” word order would be.

In the same way, Berbice Creole Dutch, for which all but no historical sources survive, may have begun as SOV but moved towards SVO under pressure from English and Guyanese Creole English over time. Similarly, the creolized version of the pidgin Chinook Jargon was SVO despite Chinook itself being VSO, but then its speakers’ dominant language was English. It is sparsely discussed that Philippine Creole Spanish is VSO as are its substrate languages; however, these indigenous Philippines languages have always been spoken alongside it.

All other creoles are the product of source languages that are all (or in the case of Hawaiian Creole English, mostly) SVO. There has been properly no case in which an SOV lexifier and an SOV substrate is documented to have yielded an SVO creole. The Berbice Dutch case is closest, but besides it possibly having emerged as SOV, Dutch is SOV in embedded rather than matrix clauses, meaning that the elementary input from it would have been SVO in any case.

2.2. Word Order in Signed Languages

In contrast, signed languages’ word order is obviously much less affected by spoken languages in terms of grammar, and they are often SOV in contrast to the spoken languages in their contexts. This includes Italian Sign Language (Fischer 2014), Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language (Sandler et al. 2005), Nicaraguan Sign Language (Flaherty 2014), and the signed language of Providence Island (Washabaugh 1986), where hearing signers used SOV order when in daily contact with the deaf but tended more towards SVO otherwise, this being the order of the English and Spanish spoken on the island.

However, many signed languages have been argued to have SVO as their fundamental order, such as American Sign Language (henceforth ASL). Furthermore, within individual signed languages, the manual modality allows a good deal of heterogeneity in word order, depending, for example, on whether or not the object is human (Meir et al. 2017), or because of the possibility of the simultaneity of expression (e.g., of a verb and its object, or of a non-manual sign extending over the duration of the others), or agreeing verbs favoring SOV order while plain ones favor SVO (e.g., in Flemish Sign Language Vermeerbergen et al. 2007). Because of factors such as these, Bouchard and Dubuisson (1995) question whether signed languages can be analyzed as having a basic word order at all, arguing that the manual modality leaves the sequence of elements less important than in the spoken language.

2.3. Implications for the Language Faculty

However, no analyst has proposed a reason for why the manual modality would especially favor verb-finality itself, as opposed to word order heterogeneity. Given that SOV is such a common basic word order among signed languages (although hardly a universal), signed languages demonstrate, at least, that there are no grounds for an assumption that SVO order is a default setting upon which SOV is a variation (cf. Flaherty et al. 2016 for evidence that silent gesturing favors SOV). This can be taken as lending indirect but useful support to the idea of SOV as human language’s diachronically original, and perhaps even synchronically fundamental, word order (cf. Givon 1971; Gell-Mann and Ruhlen 2011).

3. Determiners

3.1. Determiners in Creoles

A classic summary description of determiners in creoles is Bickerton’s (1981) claim that these languages instantiate a “bioprogram” that yields overt definite and indefinite determiners for specific meaning and zero marking for non-specific (or “generic”) meaning. However, with the broader perspective on creoles possible today, decades later, this formulation is as questionably “universal” as the one stipulating SVO as fundamental.

Bickerton’s characterization applies largely to Atlantic English- and French-based creoles, as well as the West African English-based creoles descended from the former such as Krio and Nigerian “Pidgin,” and the Indian Ocean French creoles of Mauritius and Seychelles. However, all of the English-based creoles here are descendants of a single original language (Hancock 1987; McWhorter 1995; Baker 1999), such that they cannot be analyzed as all manifesting a trait independently. All of the French-based creoles of the Caribbean are likely descendants of a single original language (McWhorter 2000, pp. 146–94). Thus, all of these creoles could be seen as manifesting the determiner pattern just 2 times rather than in cross-creole fashion over 25 or more times.

Moreover, the English-based creoles are most imprinted substratally by African languages of the Kwa clade in Niger–Congo, which happen to display the determiner pattern Bickerton observed. Arguments that French creole substrates were similar would also be relevant, with the Gbe languages of Kwa specified by Lefebvre (1998) for Haitian and by Jennings (1995) for French Guyanais. Thus, genetic relationships and substrate influence render the prevalence of this determiner pattern less unexpected than it would seem.

Then, beyond these creoles, the bioprogram determiner pattern is barely in evidence at all. Portuguese-based creoles do not have a definite determiner, with the distal demonstrative instead “bleeding” into a role intermediate between demonstrative and determiner as needed. These languages instead have only an indefinite determiner. Tok Pisin and its sisters also have only an indefinite determiner. Creolized Chinook Jargon had only a definite one, although studies are unclear as to whether this was a demonstrative or a true determiner, given that it was derived from an original demonstrative (ukuk) and its phonetic erosion to uk cannot be taken alone as an indication that it had changed its grammatical status.

The determiner configuration that Bickerton identified is so common among creoles because the Atlantic English ones are the product of lexifier and substrate languages that all happen to have overt definite and indefinite determiners, with the substrate languages tending to zero-mark the generic. However, this combination of source languages did not always produce the Bickerton configuration (viz. the Portuguese creoles of the Gulf of Guinea, with Edo, having definite and indefinite specific determiners, as its primary substrate). The French creoles, apart from being all likely tracing to a single ancestor (McWhorter 2000, pp. 146–94 argues that even the Indian Ocean creoles trace to the same ancestor as the Atlantic French-based creoles), have always existed amidst heavy contact with French, thus making it especially likely that they would all have definite and indefinite determiners.

Beyond these creoles, among those born of different kinds of source languages, the visible tendency is that creolization most readily yields an indefinite determiner. For example, the Atlas of Pidgin and Creole Language Structures Online survey reveals but one language with a definite but not an indefinite determiner, and this is a pidgin rather than a creole (Yimas-Arafundi Pidgin). Indefinite determiners are a form of new information marking, and there is evidence that markings of this emerge in creoles before markings of given information (cf. McWhorter 2009 on new information marking in Saramaccan).

3.2. Determiners in Signed Languages

There has not yet been as much cross-linguistic research on determiners in signed languages as on creoles. However, the work that exists suggests that the situation is rather similar.

ASL, for example, has a definite and indefinite determiner (Bahan et al. 1995; MacLaughlin 1997). However, in ASL and signed languages more generally, determiners do not mark generic (non-specific) referents (De Vriendt and Rasquinet 1989), and even specific referents are not marked as obligatorily as in many spoken languages, since they must incorporate referential information (Neidle and Nash 2012, p. 274).

Just as many creoles have definite determination only via recruitment of the distal demonstrative in especially grammaticalized meaning, the distinction between demonstrative and determiner in signed languages is also often a matter defined by a continuum (ibid. p. 271). There is evidence, on the other hand, that in signed languages as in creoles, indefinite determination is entrenched more quickly. Catalan Sign Language, for example, has a richer array of constructions for indefinite determination than for definite (Barberà 2016).

3.3. Implications for the Language Faculty

A tentative conclusion from creoles and signed languages is that emergent language develops the overt marking of new information before the overt marking of given information. This is consonant with a conception of it being central to language to transmit information, as well as to continuously justify calling upon and sustaining the interlocutor’s attention. Also relevant here is Scott-Phillips’ argument (Scott-Phillips 2015) that language would have emerged from an ostensive imperative of seeking attention for information transfer, such that pragmatics of this kind are fundamental to human language while syntax and morphology are ontogenetically secondary.

4. Subordinate Clauses

4.1. Subordination in Creoles

The overt marking of subordination is universal in creoles. They differ only in the obligatoriness of the marking (which tends to be modest) and in how wide a range of subordination constructions is marked.

All known creoles have an overt relativizer, either a pronoun or “particle.” This element is almost always optional, but nevertheless robustly conventionalized, as in Saramaccan:

| (1) | Dí mujέε (dí) mi lóbi hánsε. |

| DEF woman REL I love pretty | |

| “The woman (whom) I love is pretty.” |

In Tok Pisin, the development of such marking from the pidgin to the creole stage has been observed, with one relativizing strategy grammaticalizing a pragmatic usage of ya “here”:

| (2) | Meri ya i stap long hul ya em i hangre. |

| woman REL SM stay in hole REL 3S SM hungry | |

| “The woman who stayed in the hole was hungry.” (Sebba 1997, p. 114) |

Most creoles also have an overt marker of sentential complementation. This has often been grammaticalized from the verb “talk” or “say,” and in many creoles beyond the literal semantics of speech; cf. táa (> táki) in Saramaccan:

| (3) | Mi sábi táa i tá wóoko. |

| I know COMP you IMPF work | |

| “I know that you are working.” |

Other creoles grammaticalize other words for the function, such as “how” in Santome Creole Portuguese:

| (4) | Ê na ta sêbê ku(ma) kwa sa pe dê fa. |

| he NEG PAST know COMP thing be father his NEG | |

| “He didn’t know that it was his father.” (APiCS) |

Only in many of the Atlantic French-based creoles is there no reported marker of sentential complementation, including claims that recruitments of French que as ki are borrowings rather than integral to the creole (Peleman 1978).

Thus, while pidgins indeed tend to lack overt markers of subordination, creole languages offer, for example, no support to claims that embedding is incidental rather than integral to the language faculty (Sampson 2005; Everett 2005).

This could be treated as evidence of a transfer from the source languages. However, creoles only incorporate a subset of the grammatical features their source languages offer, even when all of the languages offer the same feature (McWhorter 2012). For example, creoles can lack definite or indefinite determiners even if their lexifiers and/or substrate had them (cf. above). However, creoles do not eschew the overt marking of subordination in contrast to such marking in source languages. Such marking would appear to be integral to spoken languages’ emergence and genesis.

4.2. Subordination in Signed Languages

In signed languages, too, there is evidence that the development of embedding is fundamental to the emergence of language (cf. Liddell 1980).

In the youngest signed languages such as certain village-based ones, embedding is absent in the first generation (cf. Sandler et al. 2011). An especially useful study is Kastner et al. (2014), documenting the emergence of subordination in the young Kafr Qasem Sign Language, which has begun at what could be called a “pidgin” stage but has developed its own type of subordination through prosodic blending of the embedded modifying expression, accompanied by non-manual signals.

In an older sign language like ASL, analysts have documented that along with a raised brow (Liddell 1980), backwards head tilt, and raised upper lip, relativization can be indicated with an overt “complementizer” sign, a postposed manifestation of “that” (ibid. p. 150):

| (5) | IX FEED DOG BITE CAT THAT THAT |

| “I fed the dog that bit the cat.” |

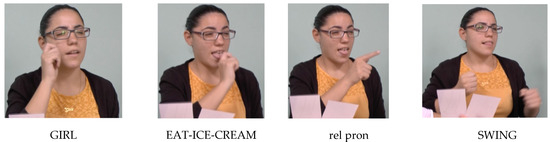

Branchini and Donati (2009) also note a sentence-final relativization particle in Italian Sign Language, and manual signs for relative clauses have also been described in German Sign Language (Leuninger 2005) and Hong Kong Sign Language (Tang and Lau 2012). In older signers of Israeli Sign Language, there was no systematic marking of relative clauses. Nonmanual markers for relative clauses (Nespor and Sandler 1999) only became systematic in the second generation of the emergence of this language, and in the third generation, a manual relative pronoun emerged (Dachkovsky 2020. Both manual and nonmanual markers of relative clauses in ISL are seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

‘The girl who is eating ice cream is swinging’. The relative clause is marked nonmanually by squint and head movement forward to the end of the clause, and manually by the clause-final relative pronoun pointing sign. There is a prosodic break between the relative clause (GIRL EAT-ICE-CREAM IX) and the rest of the sentence (SWING). (Dachkovsky 2020). Pictures courtesy of the Sign Language Research Lab, University of Haifa.

The overt marking of sentential complementation is documented in many signed languages. Padden (1988) notes that ASL marks sentential complementation with a final pronoun copy that refers to the first, matrix subject in embedded structures (6a), but must refer to the subject of the second clause in coordinate structures, so that (6b) is ungrammatical.

| (6) | (a) | 1INDEX DECIDE iINDEX SHOULD iDRIVEj SEE CHILDREN 1INDEX |

| “I decided he ought to drive over to see his children, I did.” | ||

| (b) | *1HITi, iINDEX TATTLE MOTHER iINDEX | |

| “I hit him and he told his mother, I did.” |

Strategies for marking sentential complementation are multifarious in signed languages; however, the ASL construction is in no sense a default. In Israeli Sign Language, a relativizer has developed in a fashion familiar in spoken language: from a locative deictic sign (Dachkovsky 2020). But in Dutch Sign Language, direct speech complements can be marked with the sign for “attract attention” (Dutch roepen) (Van Gijn 2004, p. 36):

| (7) | rightASKsigner ATTRACT-ATTENTIONsigner IXaddressee WANT COFFEE |

| “He/she asks me ‘Do you want any coffee?’” |

In Hong Kong Sign Language, embeddedness reveals itself in otherwise unexplainable ungrammaticalities. Examples can be found in direct argument questions, in which wh-words can be sentence-initial or sentence-final, but when embedded can only be sentence-final (Tang and Lau 2012, p. 353):

| (8) | FATHER WONDER *(WHO) HELP KENNY WHO |

| “Father wondered who helped Kenny.” |

In Hong Kong Sign Language, as in others, sentential complement subordination can also be accompanied by non-manual signs such as shakes of the head, leaning of the body.

4.3. Implications for the Language Faculty

If, as Everett (2005) famously argued, the Amazonian language Pirahã lacks embedding, his proposition that this invalidates the idea of embedding (and thus recursion in general) as a feature of Universal Grammar is not supported by emergent languages of either the spoken or manual modality. Creole languages develop overt markers of subordination quite readily in the transition from pidgin to creole: no creole could be recruited as support for a claim that Universal Grammar lacks recursion. Meanwhile, signed languages also quickly develop markers of both relativization and sentential complementation, with only the youngest sign languages lacking these (just as pidgins do in contrast to creoles).

5. Tense and Aspect Marking

5.1. Tense and Aspect Marking in Creoles

Bickerton (1981) claimed that creoles universally share a three-way contrast between three preposed “particles” marking:

- (1)

- anterior past, marking dynamic verbs as past-before-past and stative ones as simple past;

- (2)

- nonpunctual, both the progressive and the habitual;

- (3)

- irrealis, and that these combine in orders uniform across creoles to lend various aspects and moods (e.g., Sranan’s a ben sa e waka “He would have been walking” contains the equivalent particles in the same order as in Haitian Creole’s expression of the same sentence, li t’av ap mache).

Predictably, creoles’ marking of tense and aspect has been shown to be less uniform than Bickerton implied. Not all creole past markers are “anterior” ones that express a past-before-past with dynamic verbs (Mauritian Creole French’s ti dose not, for example). Saramaccan has dedicated habitual markers, one of them well-entrenched in the grammar (ló > lóbi “love”), rather than expressing the habitual via context with the progressive marker tá. Many creoles do not have a single irrealis marker but distinct ones for future and potential (cf. Saramaccan’s gó vs. sá), etc.

However, missed amidst the critiques but worthy of remark is the fact that creoles do share a core of three markers of, roughly, past, progressive, and future. As ordinary as this may seem superficially, the questions are why:

- (1)

- no attested creole marks only aspect and not tense the way Chinese and many Southeast Asian languages do. Only creolized Chinook Jargon lacked tense marking, and there is a question as to how far from the pidgin this variety was.

- (2)

- no attested creole has a future marker but not a past marker as Vietnamese, Ewe, and many languages do not.

- (3)

- no attested creole has simply not developed markers of tense or aspect at all, the way the Papuan language Maybrat has not (Dol 2007).

- (4)

- no creole expresses the habitual specifically with zero marking the way English does.

Instead, even creoles of a non-Indo-European lexical base converge on sharing the same basic trio of markers, including Nubi Creole Arabic.

If creoles actually were not distinguishable as a class, then they would presumably diverge considerably in their choices of tense and aspect markers, just as older languages do.

A riposte could be that creoles were too recently imprinted by their source languages to have morphed grammar-internally to this extent. But if source languages determined which tense and aspect markers each creole had, we would still expect much more variation. Why does there not exist an English-based creole in which the habitual is dedicatedly marked with zero as it is in English, or in which the progressive marker is extended beyond the continuative to the present as it is in English? To extend the analysis to mood, why has no creole emerged with a monomorphemic marker of the conditional as there is in western European languages, except ones highly decreolized towards, for example, English?

Creoles have instead regularly selected from their source languages three features, while omitting to incorporate the many others. Bickerton’s characterization of these three elements was too specific, but the heart of his observation was correct.

5.2. Tense and Aspect Marking in Signed Languages

In signed languages, the expression of aspect is universal, but many do not obligatorily express tense overtly (Friedman 1975), instead using adverbials where necessary (such as Israeli Sign Language (Meir and Sandler 2008, p. 89)). Where some signed languages are claimed to express tense, it is on subsets of verbs rather than all of them. ASL has what Aarons et al. (1995) term lexical tense markers, distinguishable from adverbials in occurring inside the VP, while Jacobowitz and Stokoe (1988) identified flexion as marking past and extension as marking future in a subset of ASL verbs. British Sign Language has some verbs that have distinct signs in the present and past (Sutton-Spence and Woll 1999, p. 116).

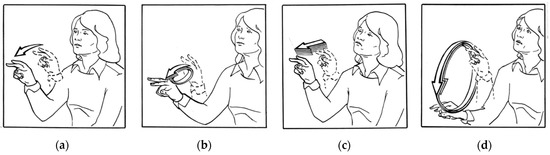

However, signed languages have richer arrays of ways to mark aspect than tense, often combining manual and non-manual signs (Pfau et al. 2012a, p. 196). For example, Israeli Sign Language, while leaving tense unmarked, has three aspectual markers (Meir and Sandler 2008, p. 91). In addition to the common marking of the continuous and the habitual, for example, with repetitive movements and different path shapes (e.g., Klima and Bellugi 1979; Meir and Sandler 2008), one of Israeli Sign Language’s aspectual markers is a perfect marker glossed ALREADY (Meir 1999), somewhat similar to the ASL marker FINISH. Whereas signed languages typically restrict tense marking, if present, to a subset of verbs, Sign Language of the Netherlands has a habitual affix for verbs whose signs cannot by iterated physically (Hoiting and Slobin 2001). Signed languages seem as prone to develop aspectual marking as creoles are to developing a trio of markers of past, progressive, and future. Examples of temporal aspect marking in ASL are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Temporal aspects in American Sign Language (Klima and Bellugi 1979) (a) LOOK (citation form), (b) LOOK Habitual, (c) LOOK Durational, (d) LOOK Continuative. (With permission from Urusula Bellugi).

5.3. Implications for the Language Faculty

Signed languages, in particular, suggest that despite the traditional centrality of tense to the analysis and pedagogy of Indo-European languages, aspect is more fundamental to the human language capacity. There is typological support for this as well, in that while there exist languages that mark aspect but not tense (Chinese and many East Asian languages), there seem to be few to none that mark tense but not aspect.

Creole languages regularly mark tense as well as aspect. However, the bias in extant creoles’ source languages may play a part here similar to the part it plays in word order and the presence of overt determiners. In any known language emerging from a pidgin-level variety, all or at least most of the source languages have both past and future markers (one exception being that Niger-Congo’s Ewe lacks a past marker, but no creole is known to have had this language as its main substrate as opposed to one of many). For example, there is no creole based on languages like Chinese and Vietnamese, which might show us a creole emerging with no marking of tense.

The closest example is varieties of Malay/Indonesian born of second-language acquisition by various peoples of Indonesia and contiguous areas. Some of these have been classified as creoles. Baba Malay, for example, is Malay acquired incompletely and affected by transfer from Hokkien Chinese. Baba Malay has a marker of perfective aspect rather than past tense, and no grammaticalized marker of futurity as a category (Lee forthcoming). However, the incomplete acquisition in Malay/Indonesian cases like these was not as extreme as pidginization, and both the perfective marker and the adverbially marked future are Malay/Indonesian features.

Still, there are suggestions even within creoles of the centrality of aspect. In creolized Chinook Jargon, as well as the pidgin variety, amidst the highly limited amount of grammatical machinery there was an aspect marker but no tense markers. Also, creoles develop new aspectual constructions more readily than new tenses.

In Saramaccan, beyond the past, future, and progressive markers, the ones in this table have emerged as well, via grammaticalization of verbs, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Aspect and mood markers in Saramaccan beyond the “big three”.

Of the six, four are aspectual. Saramaccan has not developed a pluperfect, remote future, or narrative-present construction. Aspect would seem to have been felt more urgent to express.

6. Inflection

6.1. Inflection in Signed Languages

An often-noticed contrast between signed languages and creoles is that while creoles have little or no inflectional morphology, signed languages are rich in it (cf. Aronoff et al. 2005).

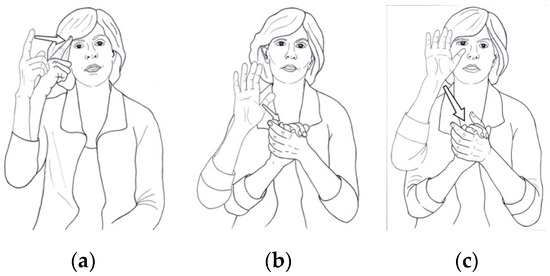

First, most established signed languages have a class of verbs referred to in much of the literature as agreeing verbs (Padden 1988; Meir 2002; Lillo-Martin and Meier 2011), mostly verbs of transfer (literally and metaphorically) such as give, send, take, help, and tell, which have affixes indexed to the verb’s arguments. Verb agreement in ASL is exemplified in Figure 3. The phenomenon differs in detail from sign language to sign language, but it is present in many established sign languages that have been studied. Meir (2012) documents the emergence of this kind of inflection in Israeli Sign Language, in which such verbs come to be rendered from and to points in space referring to the arguments. Emergent sign languages may not have agreeing verbs at the outset (Padden et al. 2010; Meir and Sandler 2008, p. 87); however, Rathmann and Mathur (2008) demonstrate that once established, this kind of marking becomes more complex over time.

Figure 3.

Some examples of verb agreement in ASL. (a) I-GIVE-YOU, (b) I-GIVE-HIM, (c) (I-)GIVE-ALL. With permission from Carol Padden. (Spatial agreement with subjects other than first person, not pictured, also occurs regularly in ASL and other sign languages).

Second, signed languages develop a type of classifiers that manifest “depiction” verbs, of motion and location (cf. Emmorey 2013). That they belong to a discrete set which can occur redundantly with the specific nouns they refer to indicates their status as agreement inflection (Supalla 1996). The motions and locations that attach to these classifiers elaborate the meaning (cf. Meir and Sandler 2008, p. 111 for a useful cataloguing of classifiers in Israeli Sign Language). Signed languages also indicate aspect inflectionally as shown in Figure 2 above.

6.2. Inflection in Creoles

The pidginization process eliminates all or most inflectional affixation, and it only re-emerges in creoles very slowly. In some, sustained contact with a source language preserves a small amount of inflection, or allows it to be borrowed over time, often reanalyzing its behavior and function. For example, in Mauritian Creole, the French distinction between finite and infinitive verb stems is preserved as short and long forms derived from them, respectively, but reanalyzed; the long form carries what can be analyzed as an affix, with the occurrence of the forms determined by syntax, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Short and long verb forms in Mauritian Creole French.

Otherwise, inflection in creoles tends to occur in highly proscribed contexts. In Santome Portuguese Creole, ba “go” occurs as be when followed by an adjunct (E ba ke “He went home;” E be d’ai “He went from here” (APiCS)). In Saramaccan, with the same verb, “go,” the imperfective proclitic tá occurs as nán-: Mi tá wáka “I am walking;” Mi nángó “I am going.”

Saramaccan also has what can be analyzed as an object agreement marker, in the specific context of shared object serial verb constructions. In the sentence below, the low tones of “turtle” are fixed and thus do not participate in the rightward spread of high tone through the sentence. However, the high tone spread “jumps” over this object and alights upon the first syllable of the second verb kulé, which in citation form has a high tone only on its second syllable. Thus the tonal spread is a kind of object agreement.

| (9) | Mi ó | nákí dí | lògòsò kúlé gó a | mí wósu |

| 1S FUT hit | DEF turtle | run | go LOC my house | |

| ‘I will hit the turtle and run to my house.’ (Rountree 1972, p. 325) | ||||

6.3. Implications for the Language Faculty

The relative richness of inflection in signed languages makes it clear that it is an overgeneralization to stipulate that emergent languages must be low on inflection. However, modality is the reason for the contrast between spoken and signed languages here.

For one, in signed languages inflection can be readily indicated iconically, via hand position or movement, or in the case of shape classifiers, by lexical signs recruited as inflections (Meir et al. 2010). In spoken language, inflection most readily emerges from a long-term process: the grammaticalization of lexical items. Also, as Poizner and Tallal (1987) noted, while visual processing of language is ill-suited to linear processing as rapid as what is possible in spoken language, “Signed languages have the potential for multiple channels for encoding grammatical information: face, head, torso, eyes, and various joints of the two arms can realize morphemically distinct information simultaneously” (cf. also Aronoff et al. 2005; Sandler 2018).

Language processed through the eye, then, develops inflection readily upon emergence; language processed through the ear does not. As such, inflection in emergent spoken languages (i.e., creoles) is unexpected; in signed languages, what would be unexpected is its absence. However, Aronoff et al. (2005) note the relevance of the difference between simultaneous and sequential morphology. The latter, developed via grammaticalization of erstwhile unbound morphemes, is much less common in signed languages, with the reason for this being their youth. In this sense, signed languages parallel creoles, as they so often do. (However, just as creoles are usually not completely devoid of new affixation, Polish Sign Language has developed several grammaticalized affixes marking negation, degrees of time, and “not yet” (Tomaszewski and Eźlakowki 2021a, 2021b).)

7. Derivational Compositionality

McWhorter (1998, 2012) argues that creoles are the world’s only languages which combine three features:

- (1)

- morphologically—very little or no inflectional morphology, bound or free

- (2)

- phonologically—very little or no lexical or grammatical tone

- (3)

- semantically—non-compositional derivational combinations.

We might ask the extent to which signed languages, as new languages, conform to this prototype.

As seen above, they do not, in terms of inflectional morphology. Also, obviously, the tonal aspect is irrelevant to signed languages. However, in terms of derivation, signed languages and creoles appear to pattern similarly.

7.1. Derivational Compositionality in Creoles

Derivational processes leave a cline of compositionality in older languages, such as in English, where we can identify four degrees:

- Predictable: recount;

- Unpredictable, but recoverable: overlook, transmission (in reference to cars), sometimes termed institutionalization (Bauer 1983, p. 38);

- Analyzable: i.e., as involving morphology, but with the specific meaning of one or more elements now opaque: understand, make up;

- Fossilized: sloth < slow + th.

In creole languages, born recently of pidgins, there are always cases of unpredictability in derivation, as no language could exist without them given the realities of culture and the vagaries of labelling. However, not enough time has passed for the emergence of cases of Level 3, where elements of a derived word have lost their synchronic meaning.

While generally overlooked in grammatical descriptions, cases like this are typical of languages that have existed for countless millennia (i.e., most human languages). They occur not only in combinations of roots with derivational prefixes, but in compounding, as in these Mandarin cases (Packard 2000, p. 222), given in Table 3:

Table 3.

Analyzable but opaque compounds in Mandarin.

Creoles that have co-existed with their lexifiers borrow Level 3 cases from them, as in French creoles (explaining data regarding the prefixes de- and re- adduced by DeGraff 2005). However, in creoles that have not co-existed with their lexifiers, Level 3 cases are rare to nonexistent. For example, in Saramaccan there are only cases of Level 2—institutionalizations—rather than Level 3 (McWhorter 2013), as shown in Table 4. This is due to Saramaccan’s emergence from a pidgin just some centuries ago.

Table 4.

Level Two compounding in Saramaccan Creole.

7.2. Derivational Compositionality in Signed Languages

Compositional derivational morphology occurs in signed languages, but is limited (Aronoff et al. 2005; Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006). However, compounding is very common in signed languages; e.g., compounds were 40% of the lexicon of the signed language of Providence Island in the Caribbean. However, studies suggest that signed language compounds are of the Level 2 type rather than Level 3.

Emergent compounds have predictable meanings, such as ASL’s BLUE^SPOT “bruise,” FACE^NEW “stranger,” LOOK^STRONG “resemble,” RED^FLOW “blood,” and SEE^MAYBE “check” (Klima and Bellugi 1979; Valli et al. 2011, p. 68; Sutton-Spence and Woll 1999, p. 102). Then, “frozen” compound signs develop, in which the meaning is less predictable, and the phonology differs from that which would express the elements in simple combination (Liddell and Johnson 1986), for example, BELIEVE from THINK^MARRY in ASL, shown in Figure 4. However, signers often remain aware of the meaning of the elements within these frozen signs (Brennan 1990; Pfau et al. 2012b, pp. 171–72). In emerging signed languages, compounding often occurs productively, if erratically, on the fly.

Figure 4.

ASL compound. The constituents (a) THINK and (b) MARRY, and the compound (c) BELIEVE. Images courtesy of the Sign Language Research Lab, University of Haifa.

This is equivalent to Level 2 compounding in spoken languages. Thus signed languages appear to conform to the Creole Prototype in this regard.

8. Conclusions

The goal of this exploration has not been to merely show that creoles and signed languages have much in common. For one, the case that signed languages are emergent languages would seem unexceptionable. Then, while the case that creoles are products of emergence rather than simply mixture is less universally accepted, the traditional pidgin-to-creole life cycle is empirically documented for some creoles and reconstructed for others with argumentation thus far unaddressed by critics in its details (cf. McWhorter 2018).

Thus, we would expect signed languages and creoles to share many features. The goal in this paper is to examine whether, on the basis of these similarities (as well as the dissimilarities), these two kinds of language can shed light on the nature of emergent human language in general.

The conclusions to draw from the findings here suggest that:

- There is no reason to suppose that SVO is a “default” word order.

- Because indefinite markers convey new information, their stronger likelihood of early emergence in both creoles and signed languages can be analyzed as evidence that emergent languages develop the overt marking of new information before that of given information. This hypothesis is reinforced by evidence that creoles develop dedicated markers of new information before markers of given information.

- Clause embedding develops as a rule in emergent languages, contra hypotheses that embedding is one of the many structures a language might choose from and is especially encouraged by writing conventions. Under this analysis, languages that lack embedding exemplify not the essence of language, but a departure from it.

- Aspect marking develops before, and then more richly than, tense marking.

- Inflection develops slowly in spoken languages because of the nature of speech processing but can proliferate quickly even in the emergent speech of the manual modality.

- While derivational combinations in language are often less than optimally transparent even upon emergence, because of inevitable idiosyncrasies in the connection between label and concept (overlook as to neglect rather than to gaze beyond), derivational opacity (i.e., understand) emerges only over time, via semantic drift (i.e., of the type documented in Israeli Sign Language by Meir and Sandler 2008, pp. 229–31) combined with cultural change.

In sum, when language is emerging, it prioritizes marking the novelty of information (confirming Scott-Phillips 2015); is readily recursive (contra Everett 2005); favors the manner of action (aspect) over the time of action (tense); develops inflection readily only in a visual, as opposed to aural, mode; and develops derivational opacity only as the result of drift over long periods of time.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aarons, Debra, Benjamin Bahan, Judith Kegl, and Carol Neidle. 1995. Lexical tense markers in American Sign Language. In Language, Gesture, and Space. Edited by Karen Emmorey and Judy S. Reilly. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, Mark, Irit Meir, and Wendy Sandler. 2005. The paradox of sign language morphology. Language 81: 301–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahan, Benjamin, Judy Kegl, Dawn MacLaughlin, and Carol Neidle. 1995. Convergent evidence for the structure of determiner phrases in American Sign Language. In Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Meeting of the Formal Linguistics Society of Mid-America. Edited by Leslie Gabriele, Debra Hardison and Robert Westmoreland. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Clubs Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Philip. 1999. Investigating the origin and diffusion of shared features among the Atlantic English Creoles. In St. Kitts and the Atlantic Creoles. Edited by Phillip Baker and Adrienne Bruyn. London: Westminster University Press, pp. 315–64. [Google Scholar]

- Barberà, Gemma. 2016. Indefiniteness and specificity marking in Catalan Sign Language. Sign Language and Linguistics 19: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Laurie. 1983. English Word Formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bickerton, Derek. 1981. Roots of language. Ann Arbor: Karoma. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, Denis, and Colette Dubuisson. 1995. Grammar, order & position of wh-signs in Quebec Sign Language. Sign Language Studies 87: 99–139. [Google Scholar]

- Branchini, Chiara, and Caterina Donati. 2009. Relatively different: Italian Sign Language relative clauses in a typological perspective. In Correlatives Cross-Linguistically. Edited by Aniko Liptak. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 157–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Mary. 1990. Word Formation in British Sign Language. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, Clancy. 1996. The Genesis of a Language: The Formation and Development of Korlai Portuguese. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Dachkovsky, Svetlana. 2020. From a demonstrative to a relative clause marker. Sign Languages and Linguistics 23: 142–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vriendt, Sera, and Max Rasquinet. 1989. The expression of genericity in sign language. In Current Trends in European Sign Language Research: Proceedings of the 3rd European Congress on Sign Language Research. Edited by Siegmund Prillwitz and Tomas Volhaber. Hamburg: Signum Verlag, pp. 249–55. [Google Scholar]

- DeGraff, Michel. 2005. Morphology and word order in “creolization” and beyond. In Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 293–372. [Google Scholar]

- Dol, Philomena. 2007. A Grammar of Maybrat. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Emmorey, Karen, ed. 2013. Perspectives on Classifier Constructions in Sign Languages. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, Daniel. 2005. Cultural constraints on grammar and cognition in Pirahã: Another look at the design features of human language. Current Anthropology 46: 621–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Susan. 1978. Sign language and creoles. In Understanding Language Through Sign Language Research. Edited by Patricia Siple. New York: Academic Press, pp. 309–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Susan. 2014. Constituent order in sign languages. Gengo Kenkyu 146: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, Molly. 2014. The Emergence of Argument Structural Devices in Nicaraguan Sign Language. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, Molly, Katelyn Stangl, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2016. Do lab attested biases predict the structure of a new natural language? In Proceedings of the Eleventh Evolution of Language Conference. Edited by Seán Roberts, Christine Cuskley, Luke McCrohon, Lluís Barceló-Coblijn, Olga Fehér and TessaVerhoef. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Lynn. 1975. Space, time, and person reference in American Sign Language. Language 51: 940–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, Murray, and Merrit Ruhlen. 2011. The origin and evolution of word order. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108: 17290–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givon, Talmy. 1971. Historical syntax and synchronic morphology: An archeologist’s field trip. Chicago Linguistic Society 7: 394–415. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, Ian. 1987. A preliminary classification of the Anglophone Atlantic creoles with syntactic data from thirty-three representative dialects. In Pidgin and Creole Languages: Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke. Edited by Glenn Gilbert. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 310–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hoiting, Nini, and Dan Slobin. 2001. Typological and modality constraints on borrowing: Examples from the Sign Language of the Netherlands. In Foreign Vocabulary in Sign Languages: A Cross-Linguistic Investigation of Word Formation. Edited by Diane Brentari. Mahwah: Erlbaum, pp. 121–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobowitz, Lynn, and William Stokoe. 1988. Signs of tense in ASL verbs. Sign Language Studies 60: 341–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, William. 1995. Saint-Cristophe: Site of the first French creole. In From Contact to Creole and Beyond. Edited by Philip Baker. London: University of Westminster Press, pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner, Itamar, Irit Meir, Wendy Sandler, and Svetlana Dachkovsky. 2014. The emergence of embedded structure: Insights from Kafr Qasem Sign Language. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klima, Edward, and Ursula Bellugi. 1979. The Signs of Language. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Nala H. forthcoming. A Grammar of Baba Malay. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Lefebvre, Claire. 1998. Creole Genesis and the Acquisition of Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leuninger, Helen. 2005. Gebärdensprachen: Struktur, Erwerb, Verwendung (Linguistische Berichte—Sonderhefte). Hamburg: Buske. [Google Scholar]

- Liddell, Scott. 1980. American Sign Language Syntax. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Liddell, Scott, and Robert Johnson. 1986. American Sign Language compound formation processes, lexicalization, and phonological remnants. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 4: 445–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Martin, Diane, and Richard Meier. 2011. On the linguistic stats of ‘agreement’ in sign languages. Theoretical Linguistics 37: 95–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLaughlin, Dawn. 1997. The Structure of Determiner Phrases: Evidence from American Sign Language. Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McWhorter, John. 1995. Sisters under the skin: A case for genetic relationship between the Atlantic English-Based Creoles. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 10: 289–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhorter, John. 1998. Identifying the creole prototype: Vindicating a typological class. Language 74: 788–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhorter, John. 2000. The Missing Spanish Creoles. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- McWhorter, John. 2009. Oh, Noo! A bewilderingly multifunctional Saramaccan word teaches us how a creole language develops complexity. In Language Complexity as an Evolving Variable. Edited by Geoffrey Sampson, David Gil and Peter Trudgill. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 141–63. [Google Scholar]

- McWhorter, John. 2012. Case closed? Testing the feature pool hypothesis. (Guest Column No. 1). Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 27: 171–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhorter, John. 2013. Why noncompositional derivation isn’t boring: A second try on the “other” part of the Creole Proptotype Hypothesis. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 28: 167–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhorter, John. 2018. The Creole Debate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, Richard. 1984. Sign as creole. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 7: 201–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meir, Irit. 1999. Thematic structure and verb agreement in Israeli Sign Language. Sign Language and Linguistics 2: 263–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meir, Irit. 2002. A cross-modality perspective on verb agreement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 20: 413–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meir, Irit. 2012. Word classes and word formation. In Sign Language: An International Handbook. Edited by Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach and Bencie Woll. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 77–112. [Google Scholar]

- Meir, Irit, and Wendy Sandler. 2008. A Language in Space. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meir, Irit, Wendy Sandler, Carol Padden, and Mark Aronoff. 2010. Emerging sign languages. In The Oxford Handbook of Deaf Studies, Language, and Education 2. Edited by Marc Marschark and Patricia Elizabeth Spencer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meir, Irit, Mark Aronoff, Carl Börstell, So-One Hwang, Deniz Ilkbasaran, Itamar Kastner, Ryan Lepic, Adi Lifshitz Ben-Basat, Carol Padden, and Wendy Sandler. 2017. The effect of being human and the basis of grammatical word order: Insights from novel communication systems and young sign languages. Cognition 158: 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mufwene, Salikoko. 2001. The Ecology of Language Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlhaüsler, Peter. 1986. Pidgin and Creole Linguistics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Neidle, Carol, and Joan Nash. 2012. The noun phrase. In Sign Language: An International Handbook. Edited by Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach and Bencie Woll. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 265–92. [Google Scholar]

- Nespor, Marina, and Wendy Sandler. 1999. Prosodic phonology in Israeli Sign Language. Language and Speech 42: 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, Jerome. 2000. The Morphology of Chinese: A Linguistic and Cognitive Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padden, Carol. 1988. Interaction of Morphology and Syntax in American Sign Language. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Padden, Carol, Irit Meir, Mark Aronoff, and Wendy Sandler. 2010. The grammar of space in two new sign languages. In Sign languages: A Cambridge Survey. Edited by D. Brentari. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 573–95. [Google Scholar]

- Peleman, Louis. 1978. Diksyonne Kreol-Franse (French Creole Dictionary). Port-au-Prince: Bon Nouvel. [Google Scholar]

- Pfau, Roland, Markus Steinbach, and Benicie Woll. 2012a. Tense, aspect and modality. In Sign Language. Edited by Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach and Bencie Woll. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 186–204. [Google Scholar]

- Pfau, Roland, Markus Steinbach, and Benicie Woll. 2012b. Sign Language: An International Handbook. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann, Christian, and Gaurav Mathur. 2008. Verb agreement as a linguistic innovation in signed languages. In Signs of the Time: Selected Papers from TISLR 2004. Edited by Josep Quer. Hamburg: Signum, pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Poizner, Howard, and Paula Tallal. 1987. Temporal processing in deaf signers. Brain and Language 30: 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Sarah J. 2000. Nativization and the genesis of a Hawaiian Creole. In Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles. Edited by John McWhorter. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 257–300. [Google Scholar]

- Rountree, S. Catherine. 1972. Saramaccan tone in relation to intonation and grammar. Lingua 29: 308–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarin, William. 2000. The status of Sango in fact and fiction. In Language Change and Language Contact in Pidgins and Creoles. Edited by John McWhorter. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 301–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, Geoffrey. 2005. The ‘Language Instinct’ Debate. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, Wendy. 2018. The body as evidence for the nature of language. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, Wendy, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2006. Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambrdige: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, Wendy, Irit Meir, Carol Padden, and Mark Aronoff. 2005. The emergence of grammar: Systematic structure in a new language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102: 2661–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, Wendy, Irit Meir, Svetlana Dachkovsky, Carol Padden, and Mark Aronoff. 2011. The emergence of complexity in prosody and syntax. Lingua 121: 2014–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scott-Phillips, Thomas. 2015. Speaking Our Minds. London: Macmillan Education UK. [Google Scholar]

- Sebba, Mark. 1997. Contact Languages: Pidgins and Creoles. New York: St. Martin’s. [Google Scholar]

- Supalla, Ted. 1996. The classifier system in American Sign Language. In Noun Classes and Categorization. Edited by Colette Craig. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-Spence, Rachel, and Bencie Woll. 1999. The Linguistics of British Sign Language: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Gladys, and Prudence Lau. 2012. Coordination and subordination in sign languages. In Sign Language: An International Handbook. Edited by Roland Pfau, Markus Steinbach and Bencie Woll. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 340–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski, Piotr, and Wiktor Eźlakowki. 2021a. Negative affixation in Polish Sign Language. Sign Language Studies 21: 290–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, Piotr, and Wiktor Eźlakowki. 2021b. Temporal affixation in Polish Sign Language. Sign Language Studies 22: 106–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, Clayton, Ceil Lucas, Kristin J. Mulrooney, and Miako Villanueva, eds. 2011. Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gijn, Ingeborg. 2004. The Quest for Syntactic Dependency: Sentential Complementation in Sign Language of the Netherlands. Utrecht: LOT. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeerbergen, Myriam, Mieke Van Herreweghe, Philemon Akach, and Emily Matabane. 2007. Constituent order in Flemish Sign Language and South African Sign Language: A cross linguistic study. Sign Language and Linguistics 10: 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washabaugh, William. 1986. Five Fingers for Survival. Ann Arbor: Karoma. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).