Learning to Teach English in the Multilingual Classroom Utilizing the Framework of Reference for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Cultures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Utilizing FREPA in Pre-Service English Teacher Training

2. Materials and Methods

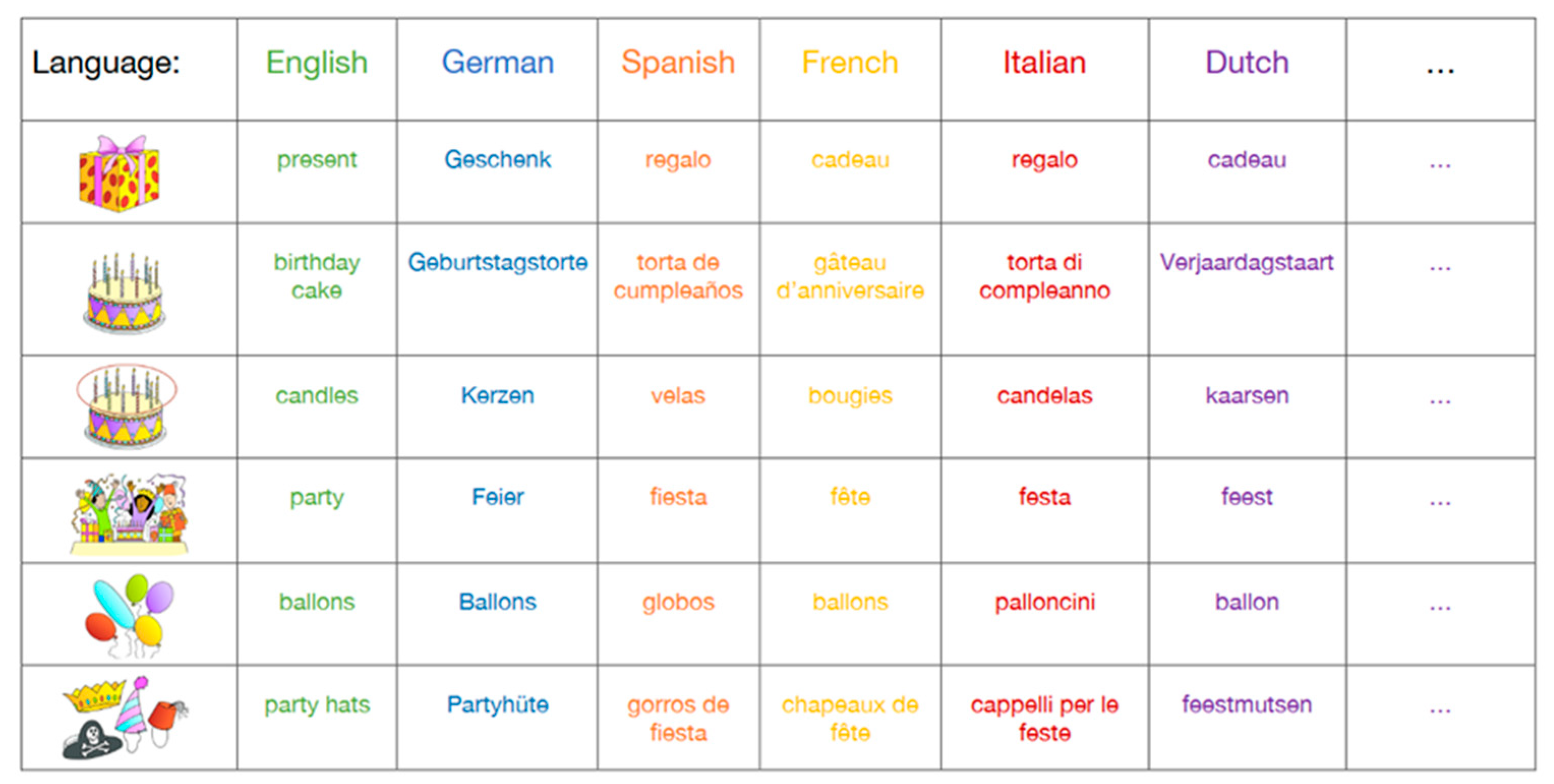

2.1. Example Activity 1: Children of the World, Special Days

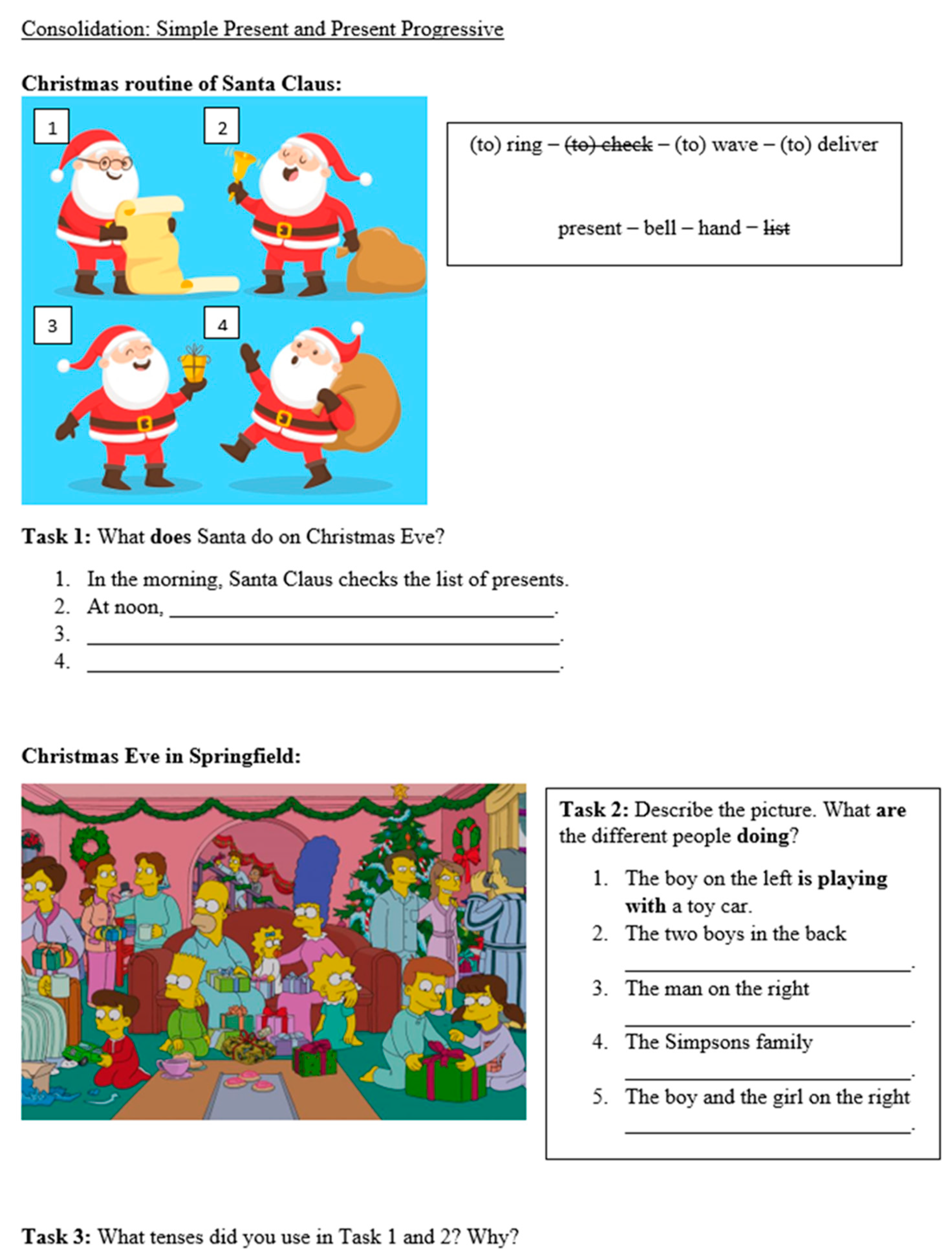

2.2. Example Activity 2: Present Simple vs. Present Progressive Tenses

3. Results

3.1. Example Activity 1: Children of the World, Special Days

- ▪

- K5.1: Knows that there are very many languages in the world

- ▪

- K5.2: Knows that there are many different kinds of sounds used in languages

- ▪

- K6: Knows that there are similarities and differences between languages/linguistic variations

- ▪

- K7.2: Knows that one can build on the structural, discursive, pragmatic similarities between languages in order to learn languages

- ▪

- A2.3: Sensitivity to linguistic/cultural similarities

- ▪

- A3.2.1: Being curious about (and wishing) to understand the similarities and differences between one’s own language/culture and the target language/culture

- ▪

- A12.4: Disposition to reflect on the differences between languages/cultures and on the relative nature of one’s own linguistic/cultural system

- ▪

- A14.3.1: Confidence in one’s capacities of observation/of analysis of little known or unknown languages

- ▪

- A18.1: A positive attitude towards the learning of languages (and the speakers who speak them)

- ▪

- S2.3: Can make use of linguistic evidence to identify (recognise) words of different origin

- ▪

- S3.3.1: Can establish similarity and difference between languages/cultures from observation/analysis/identification/recognition of some of their components

- ▪

- S3.5: Can perceive global similarities between two/several languages

- ▪

- S4: Can talk about/explain certain aspects of one’s own language/one’s culture/other languages/other cultures

- ▪

- S5: Can use knowledge and skills already mastered in one language in activities of comprehension/production in another language

- ▪

- S5.3.1: Can make interlingual transfers/transfers of recognition/transfers of production from a known language to an unfamiliar one

- ▪

- S7.4: Can profit from transfers made successfully/unsuccessfully between a known language and another language in order to acquire features of that other language

3.2. Example Activity 2: Present Simple vs. Present Progressive Tenses

- ▪

- K6.7: Knows that words can be constructed differently in different languages

- ▪

- K6.8: Knows that the organization of an utterance may vary from one language to another

- ▪

- K7.2: Knows that one can build on the (structural, discursive, pragmatic) similarities between languages in order to learn languages

- ▪

- A2.4: Being sensitive both to differences and to similarities between different languages

- ▪

- A2.6: Sensitivity to the relativity of linguistic uses

- ▪

- A4.1: Mastery of one’s resistances/reticence towards what is linguistically different

- ▪

- A7.5: Motivation to study/compare the functioning of different languages

- ▪

- A11.1: Being disposed to distance oneself from one’s own language/look at one’s own language from the outside

- ▪

- S1.4: Can observe/analyse syntactic and/or morphological structures

- ▪

- S2.2.2: Can identify/recognize a morpheme/a word in the written form of familiar and unfamiliar languages

- ▪

- S2.4: Can identify/recognize grammatical categories/functions/markers

- ▪

- S2.5: Can identify languages on the basis of identification of linguistic forms

- ▪

- S3.8: Can compare grammatical functions of different languages

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Activity 1: Children of the World, Special Days

Appendix A.2. Activity 2: Present Simple vs. Present Progressive Tenses

| 1 | The EPOSTL is a tool for students in teacher training that allows them to reflect on their knowledge of didactics and the necessary skills for language teaching, as well as to assess their developing didactic competences (Newby et al. 2007, p. 5). |

References

- Bialystok, Ellen. 2017. The bilingual adaptation: How minds accommodate experience. Psychological Bulletin 143: 233–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, Vera, Jasone Cenoz, Nina Dalmann, and Franziska Rogge. 2020. Addressing linguistic diversity in the language classroom in a resource-oriented way: An intervention study with primary school children. Language Learning 70: 382–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čajko, Irena H. 2014. Developing metalinguistic awareness in L3 German classrooms. In Teaching and Learning in Multilingual Contexts. Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives. Edited by Agnieszka Otwinowska and Gessica De Angelis. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Candelier, Michel, Antoinette Camilleri-Grima, Véronique Castellotti, Jean-Francois de Pietro, Ildiko Lörincz, Franz-Joseph Meißner, Artur Noguerol, and Anna Schröder-Sura. 2012. A Framework of Reference for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Cultures. Competences and Resources. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Available online: https://carap.ecml.at/Descriptorsofresources/tabid/2654/language/en-GB/Default.aspx (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2003. The additive effect of bilingualism on third language acquisition: A review. International Journal of Bilingualism 7: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christison, MaryAnn, Anna Krulatz, and Yesim Sevinç. 2021. Supporting teachers of multilingual young learners: Multilingual Approach to Diversity in Education (MADE). In Facing Diversity in Child Foreign Language Education. Edited by Joanna Rokita-Jaśkow and Agata Wolanin. Cham: Springer, pp. 271–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Vivian. 1991. The poverty-of-the-stimulus-argument and multi-competence. Second Language Research 7: 103–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Vivian. 1992. Evidence for multicompetence. Language Learning 42: 557–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2018. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Companion Volume with New Descriptors. Cambridge: CUP, Available online: https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Cutrim Schmid, Euline, and Torben Schmidt. 2017. Migration-based multilingualism in the English as a foreign language classroom: Learners’ and teachers’ perspectives. Zeitschrift für Fremdsprachenforschung 28: 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, Gessica. 2007. Third or Additional Language Acquisition. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, Gessica. 2011. Teachers’ beliefs about the role of prior language knowledge in learning and how these influence teaching practices. International Journal of Multilingualism 8: 216–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifer, Jason W., and Debra Titone. 2021. Bilingualism: A neurocognitive exercise in managing uncertainty. Neurobiology of Language 2: 464–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, Barbara. 2015. On the Dynamics of Early Multilingualism. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hopp, Holger, and Dieter Thoma. 2021. Effects of plurilingual teaching on grammatical development in early foreign-language learning. The Modern Language Journal 105: 464–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, Holger, Jenny Jakisch, Sarah Sturm, Carmen Becker, and Dieter Thoma. 2020. Integrating multilingualism into the early foreign language classroom: Empirical and teaching perspectives. International Multilingual Research Journal 14: 146–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakisch, Jenny. 2015. Mehrsprachigkeit und Englischunterricht: Fachdidaktische Perspektiven, schulpraktische Sichtweisen. Fremdsprachendidaktik inhalts- und Lernorientiert. Frankfurt am Main: Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Jessner, Ulrike. 2008. Teaching third languages: Findings, trends and challenges. Language Teaching 41: 15–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jessner, Ulrike. 2014. On multilingual awareness or why the multilingual learner is a specific language learner. In Essential Topics in Applied Linguistics and Multilingualism. Studies in Honor of David Singleton. Edited by Miroslaw Pawlak and Larissa Aronin. Cham: Springer, pp. 175–84. [Google Scholar]

- Komusin, Julia. 2017. Sprachliche Vielfalt und ihr Stellenwert. Eine Studie zur Wahrnehmung bei Angehenden Englischlehrkräften [Language Diversity and its Value. A Study on the Perception of Prospective English Teachers]. Master’s thesis, University of Münster, Münster, Germany. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Kopečková, Romana, and Gregory J. Poarch. 2022. Teaching English as an Additional Language in German Secondary Schools: Pluralistic Approaches to Language Learning and Teaching in Action. In Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Teaching Foreign Languages in Multilingual Settings. Edited by Anna Krulatz, Georgios Neokleous and Anne Dahl. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Kopečková, Romana, Marta Marecka, Magdalena Wrembel, and Ulrike Gut. 2016. Interactions between three phonological subsystems of young multilinguals: The influence of language status. International Journal of Multilingualism 13: 426–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, Judith F., Jason W. Gullifer, and Eleonora Rossi. 2013. The multilingual lexicon: The cognitive and neural basis of lexical comprehension and production in two or more languages. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33: 102–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krulatz, Anna, Anne Dahl, and Mona E. Flognfeld. 2018. Enacting Multilingualism. From Research to Teaching Practice in the English Classroom. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk. [Google Scholar]

- Krulatz, Anna, Georgios Neokleous, and Anne Dahl, eds. 2022. Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Teaching Foreign Languages in Multilingual Settings. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, Eliane, Anna Krulatz, and Eivind N. Torgersen. 2021. Embracing linguistic and cultural diversity in multilingual EAL classrooms: The impact of professional development on teacher beliefs and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education 105: 103428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdi, Georges, and Bernard Py. 2009. To be or not to be … a plurilingual speaker. International Journal of Multilingualism 6: 154–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, David, Rebecca Allan, Anne-Brit Fenner, Barry Jones, Hanna Komorowska, and Kristine Soghikyan. 2007. European Portfolio for Student Teachers of Languages. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Available online: http://archive.ecml.at/mtp2/fte/pdf/c3_epostl_e.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Otwinowska, Agnieszka, and Gessica De Angelis. 2014. Teaching and Learning in Multilingual Contexts. Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Peyer, Elisabeth, Malgorzata Barras, and Gabriela Lüthi. 2020. Including home languages in the classroom: A videographic study on challenges and possibilities of multilingual pedagogy. International Journal of Multilingualism 19: 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyer, Elisabeth, Malgorzata Barras, Gabriela Lüthi, and Karolina Kofler. 2019. Project Teaching and Learning Foreign Languages in Schools under the Sign of Multilingualism: Selected Materials. Fribourg: Institute of Multilingualism. [Google Scholar]

- Poarch, Gregory J. 2018. How the use and control of multiple languages can affect attentional processes. In The Interactive Mind: Language, Vision and Attention. Edited by Nivedita Mani, Ramesh K. Mishra and Falk Huettig. Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Poarch, Gregory J., and Andrea Krott. 2019. A bilingual advantage? An appeal for a change in perspective and recommendations for future research. Behavioral Sciences 9: 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Poarch, Gregory J., and Ellen Bialystok. 2017. Assessing the implications of migrant multilingualism for language education. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 20: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poarch, Gregory J., and Janet G. Van Hell. 2018. Bilingualism and the development of executive function in children. In The Interplay of Languages and Cognition. Edited by Sandra A. Wiebe and Julia Karbach. New York: Routledge, pp. 172–87. [Google Scholar]

- QUA-LiS NRW—Qualitäts- und UnterstützungsAgentur Landesinstitut für Schule. 2009. Aufgaben und Ziele des Faches English. Lernplannavigator Grundschule. Available online: https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/lehrplaene/lehrplannavigator-grundschule/englisch/lehrplan-englisch/aufgaben-ziele/aufgaben-und-ziele.html (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Roberts, Leah, and Sarah Ann Liszka. 2013. Processing tense/aspect-agreement violations online in the second language: A self-paced reading study with French and German L2 learners of English. Second Language Research 29: 413–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason. 2011. L3 Syntactic transfer selectivity and typological determinacy: The Typological Primacy Model. Second Language Research 27: 107–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Aims | Procedure | Interaction | Media/Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 min | Introduce the lesson | Welcome and introduction | Teacher (T) | |

| 3 min | Start with a familiar point | Task 1: listening to the song “Happy Birthday” in different languages | Individual work | Audio/Video, Speaker, work sheet to write down the languages |

| 5 min | Probe awareness about diverse languages and sensitivity towards similarities and differences among them | Discussion (in German) about the languages students (Ss) discovered. How did they recognize a language? Do they know the song in another language? | Plenary | |

| 5 min | Make Ss’ languages visible | Task 2: T pins the phrase “Happy Birthday” and an equivalent in another foreign language he/she knows. Ss offer the phrase in other languages they know. T has prepared cards with phrases that the children are likely to contribute and some extra empty cards for Ss’ additional phrases | Plenary | Board, prepared cards, empty cards, magnets |

| 10 min | Be “language detectives” and discover lexical equivalents | Envelope Game—T prepares pictures and birthday-related words in English and 5 different languages in an envelope. Ss match the words with the pictures and guess the language. | Group work | Envelopes with cards with words, work sheet |

| 5 min | Talk and reflect about differences and similarities between languages, discuss strategies for the task (in German) | Which words are similar? Which words are different? How did you go about the task? | Plenary | |

| Follow up: discussion of birthday celebrations across the world |

| Time | Aim | Procedure | Interaction | Media/Material |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 min | Lead-in, establishing context, activating schemata | Jingle Bells song in different languages | YouTube | |

| 1 min | Learning aims for the session | Explaining work sheet and tasks | T | Work sheet |

| 3 min | Revision of Simple Present | Task 1: Ss describe Santa Claus’ Christmas routine with the help of pictures | Individual work > pair check | |

| 3 min | Revision of Present Progressive | Task 2: Ss describe the picture “Christmas Eve in Springfield” | Individual work > pair check | |

| 5 min | Discussion of function and form of present tenses in English | Task 3: Ss share their results from Task 1 and 2 | Plenary | |

| 7 min | Cross-linguistic observation and comparison | Tasks 4 and 5: Ss identify progressive forms in different languages | Group work | |

| 5 min | Distancing from one’s own grammar in relation to English grammar | Task 6: with the help of Task 4 + 5, Ss share their observations about other languages with/without present progressive, and compare to target English | Plenary |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kopečková, R.; Poarch, G.J. Learning to Teach English in the Multilingual Classroom Utilizing the Framework of Reference for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Cultures. Languages 2022, 7, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030168

Kopečková R, Poarch GJ. Learning to Teach English in the Multilingual Classroom Utilizing the Framework of Reference for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Cultures. Languages. 2022; 7(3):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030168

Chicago/Turabian StyleKopečková, Romana, and Gregory J. Poarch. 2022. "Learning to Teach English in the Multilingual Classroom Utilizing the Framework of Reference for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Cultures" Languages 7, no. 3: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030168

APA StyleKopečková, R., & Poarch, G. J. (2022). Learning to Teach English in the Multilingual Classroom Utilizing the Framework of Reference for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Cultures. Languages, 7(3), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030168