Abstract

Iconic words constitute an integral part of the lexicon of a language, exhibiting form-meaning resemblance. Over the course of time, semantic and phonetic transformations “weaken” the degree of iconicity of a word. This iconicity loss is known as the process of de-iconization, which is divided into four stages, and, at each consecutive stage, the degree of a word’s iconicity is reduced. The current experimental study is the first to compare and contrast how English (N = 50) and Russian (N = 106) subjects recognize visually presented native iconic words (N = 32). Our aim is two-fold: first, to identify native speakers’ ability to perceive the fine-grained division of iconicity; and second, to control for the influence of participants’ native languages. This enables us to provide a more exhaustive analysis of the role of iconicity in word recognition and to combine empirical results with a theoretical perspective. The findings showed that the speakers of these languages are not equally sensitive to iconicity. As opposed to the English-speaking participants, who showed almost similar performance on each group of iconic words, the Russian participants tended to respond slower and less accurately to the words that were higher in iconicity. We discuss the major factors that may affect iconic word recognition in each language.

1. Introduction

Interest in iconicity is on the rise within cognitive sciences, psychology, and linguistics (Nielsen and Dingemanse 2021). Although there is no link between the phonological structure and meaning of an arbitrary word (made meaningful by convention only), every natural language contains a portion of non-arbitrary elements that sound in spoken languages, or are articulated in sign languages, like what they mean (Blasi et al. 2016; Joo 2020; Östling et al. 2018). It was shown that different words consisting of specific combinations of vowels and consonants, are non-arbitrarily associated with specific sensorimotor and emotional features (Kawahara 2020). An iconic form-meaning relationship is perceived directly both visually and aurally from the physical form of a word. This resemblance-based mapping between form and meaning is caused by synaesthesia (Ramachandran and Hubbard 2001) and cross-modality (Sidhu and Pexman 2018a). Iconicity is generally considered a universal feature of a language: words with at least some degree of iconicity are registered in all languages across the world (Akita and Pardeshi 2019; Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz 2001).

The share of imitative words in the lexicon of a language depends on a particular scholar’s view on iconicity—whether all the words with historically iconic roots should be considered or just modern vivid interjections like brr or oof. The fact that languages develop over time suggests that iconic words also continuously appear, and then, over the course of their development, lose their iconic traits (Flaksman 2017). Nevertheless, unlike many non-Indo-European languages, which are rich in iconic words, Indo-European languages (i.e., English and Russian) are generally seen as relatively arbitrary (Imai and Kita 2014) (this comparison is based on the number of imitative words and their share in respective lexicons—for the discussion—see (Bartens 2000, pp. 41–43; Hinton et al. 1994, introduction)). In terms of morphology, for example, the comparative study of phonetic iconicity in Slavic, Germanic, Romance, and Finno-Ugric languages revealed no language-general tendency for the dominant occurrence of front high vowels and front consonants in diminutive affixes and high back vowels and back consonants in augmentative ones (Stekauer et al. 2009).

Traditionally, researchers interested in iconicity have focused on its audial perception, since iconic words are regarded more as a part of spoken language—often accompanied by gestures—than a part of written language (Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz 2001). Although the written sign system of a language is basically conventional, iconic items do occur there. This is especially true for the languages with alphabetic writing systems where sound sequences are coded with corresponding letter sequences. Moreover, they are essential for literary texts: “The iconicity of linguistic sound, which plays a minor part in language as a system, plays a leading character in literature, especially in poetry” (Johansen 1993, p. 227). The question raised in the present research is whether or not the users of two Indo-European languages from different groups, Germanic and Slavic, and of different morphological types, analytic (English) and synthetic (Russian), are sensitive to spoken word iconicity represented in writing and, if so, to what extent.

To date, there have been only a few experiments addressing the visual perception of spoken iconicity in these languages. For instance, a psycholinguistic study by Monaghan and Fletcher (2019) indicated that for the speakers of English, the visual processing of individual phoneme-meaning correlations (the relations between the manner of articulation and the meaning) in non-words was more important than cross-modal associations. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study on the investigation of the visual recognition of English iconic words by native English speakers in a lexical decision task. The study by Sidhu et al. (2020) examined the recognition of English iconic words in a visual lexical decision task by undergraduate students with a fluent command of English. The findings revealed faster and more accurate responses to words higher in iconicity. Studies on the investigation of Russian iconicity are scarce. The experimental study by Tkacheva et al. (2019) on the investigation of the visual perception of Russian and English iconic words by Russian adults (N = 148) has found that iconic words were identified more slowly and with a greater number of errors than non-iconic words. The findings are explained by the cognitive complexity of recognizing iconic words, which contain both semantic and figurative information. The linguistic study by Flaksman (2020) has shown that the less iconic a Russian word is, the more it is morphologically marked, which is typical of a synthetic language.

It is noteworthy that most psycholinguistic studies regard iconicity as a discrete property that is either present or absent (Dingemanse et al. 2020). Furthermore, the degree of iconicity is established not by means of (historical) linguistics but measured over the course of an experiment. Perry et al. (2015) hypothesized that words belonging to different grammatical categories exhibit different degrees of iconicity across languages. The results of their experiments showed that English native speakers rated visually presented onomatopoeic words (i.e., moo) and interjections (i.e., ouch) as most iconic, while nouns (i.e., jeans) and grammatical words (i.e., here) were least iconic. The authors also claimed that the words sounding like what they mean are the earliest words learned by both L1 and L2 learners of English. Winter et al. (2017) replicated these findings using native speaker ratings of the degree of iconicity of English words (N = 3001). The results showed that English sensory words, particularly those related to sound and touch, are more iconic than abstract ones. Altogether, their results proved that English sensory words are more strongly related to iconicity than to systematicity.

The current study builds on previous research by taking into consideration the concept of the de-iconization stage of iconic words, i.e., the degree of iconic quality and form-meaning resemblance (Flaksman 2015). The criteria for the classification of imitative words according to de-iconization stages are: (1) morphological and syntactic integration; (2) influence of regular sound changes; and (3) influence of semantic shifts (ibid.). The application of these criteria allows distinguishing words on four de-iconization stages, which co-exist simultaneously in the language. Criterion (1) separates iconic interjections and ideophones from the syntactically and morphologically integrated imitative nouns, verbs, etc. The latter can be further sub-divided into words either with or without form and/or meaning changes (Flaksman 2015, pp. 128–40):

Words at SD-1 are the most vivid, imitative words, mainly interjections that have not changed their form or meaning (e.g., Eng. grr! (int.)—‘a sign of anger or annoyance’; Rus. tpruu! (int.)—‘an exclamation, predominantly applied to horses as a command to stop’).

Words at SD-2 are content words that retain their original sound-related meaning, having not yet undergone any regular sound changes (e.g., Eng. bleep (N)—‘a short high-pitched sound made by an electronic device as a signal’; Rus: gul (N)—‘a continuous low noise’).

Words at SD-3 have lost either their original form through significant sound changes or their original (sound-related) meaning through semantic shifts (e.g., Eng. bib (N)—‘a piece of clothing fastened round a child’s neck to keep the clothes clean while eating’, probably from Latin bibere ‘to drink’; Rus: mops (N)—‘a pug’, a borrowing from Dutch or German Mops, from the verb with the original meaning ‘to look sulky, to pout’, cf. Dutsch moppen (1678) ‘to mutter, mumble, sulk, pull a face’ and English mope ‘to make a grimace, to make faces’, perhaps imitative of movements of the lips, according to OED).

Words at SD-4 have fully lost their imitative quality and remain iconic by origin only (e.g., Eng. craze (N)—‘an enthusiasm for a particular activity’, late ME in the sense ‘break, produce cracks’; Rus: klok (N)—‘a tuft’, originally a sound-symbolic word, according to Koleva-Zlateva (2008, p. 162)).

Flaksman (2015, pp. 128–31) emphasized that SD-1 words differ from the rest due to numerous reasons: this de-iconization stage is optional, as there is evidence for many imitative words being coined as SD-2 words already; they exhibit phonetic hyper-variation and instability of form (expressive ablaut, gemination, expressive vowel lengthening, metathesis); they can be reduplicated (partially or totally) without a change in meaning; and they are phonosemantically inert (Flaksman 2013), that is they are not affected by regular sound changes (unless they have proceeded to SD-2). Furthermore, although there is a significant body of research exploring visual word recognition, there is still a continuing debate as to how lexical access proceeds. Previous research (Sidhu et al. 2020; Aryani et al. 2019) has found a facilitatory effect of iconicity on the lexical processing of visually presented stimuli. The question is which additional factors can affect the visual recognition of iconic words besides iconicity itself. Obviously, interfering factors may include the frequency of words (Winter et al. 2017) and their neighborhood density (Sidhu and Pexman 2018b). Generally, in English, 71.5% of all words are monosyllabic (Gitt 2006), which results in a higher neighborhood density for monosyllabic experimental and non-word stimuli as compared with Russian. It may be an important contributing factor to the speed and accuracy of word recognition. Also, previously it was shown that different words, consisting of specific combinations of vowels and consonants, are non-arbitrarily associated with specific sensorimotor and emotional features (Kawahara 2020), i.e., that different kinds of non-arbitrary mappings can affect the process of recognition when appearing in the same stimulus (Sidhu et al. 2020). Furthermore, sound-symbolic phenomena may occur also in non-words due to specific combinations of letters in them (Sidhu and Pexman 2019). Moreover, errors, delays, and inaccuracies of recognition are typical for words, which do not behave according to the sound structure of the target language (Styles and Gawne 2017).

There are also psycholinguistic features of target word stimuli to consider, such as familiarity, imageability, emotional valence, and emotional arousal, which can affect the process of visual recognition when filled with an individual meaning for the participant (Citron et al. 2014). It is known that conceptual recognition relies on the perceptual system, and, sometimes, perceptual–conceptual interference occurs where perceptual stimulation in a particular sensory modality leads to slower or less accurate recognizing of information from the same modality (Vermeulen et al. 2008); however, there is the reverse process, called perceptual–conceptual facilitation, wherein perceptual stimulation leads to faster and more accurate recognition (Connell and Lynott 2012b). Thus, it was shown that words referring to concepts with a strong visual component are recognized faster and more accurately in a lexical decision task in comparison with non-visual words, which have a similar length and frequency (Connell and Lynott 2012a).

We propose an alternative framework to study sensitivity to visually presented iconicity in two typologically different Indo-European languages—English (analytic) and Russian (synthetic)—based on the division of iconic words according to four de-iconization stages—an additional explanatory variable that was neglected in previous research. We aim to learn how English and Russian participants recognize visually presented native iconic words in comparison with arbitrary words and non-words. We attempt to identify which factors may affect iconic word recognition in each language, given that the lexical decision time is a dependent variable. The independent variables are word frequency, neighborhood density, type of stimuli (non-words, arbitrary words, iconic words belonging to four de-iconization stages), and the individual differences of the subjects. Based on the results of the previous studies, we posit the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The most explicit iconic words are recognized more slowly and less accurately than the other content words by native speakers of Russian.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Speakers of each language are equally sensitive to iconicity and show similar recognition pattern whilst perceiving explicit iconic words (SD-1, SD-2).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The Russian and English experimental stimuli (N = 64 for each language) were rigorously selected following the pre-defined clear-cut criteria of homomorphism in terms of the length (monosyllabic), the lexical category (mainly nouns with few interjections on SD-1), and the mean frequency of the groups of stimuli (Flaksman et al. 2020). All lexical stimuli contained an equal number of iconic (N = 32) and arbitrary (N = 32) words, which were selected from The Russian Etymological Dictionary by Vasmer (2009), the Dictionary of Russian phonosemantic abnormalities by Shliahova (2004), The Oxford English Dictionary (OED 2020), the Frequency Dictionary by Lyashevskaya and Sharov (2009), and the Dictionary of English Iconic Words on Historical Principles by Flaksman (2016).

The English stimuli frequency was estimated based on the standardized measure of frequency per million words in OED containing 600 thousand lexemes of contemporary English from 1870–2020. Based on its overall frequency score per million words (fpm), each word is assigned to a frequency band on a logarithmic scale. The groups of iconic stimuli contained the words in the following bands: SD-1 from band 3 (0.01–0.099 fpm) to band 5 (1–9.9 fpm), mean band 3.625 (0.063 fpm); SD-2 from band 2 (<0.0099 fpm) to band 5 (1–9.9 fpm), mean band 3.75 (0.075 fpm); SD-3 from band 3 (0.01–0.099 fpm) to band 6 (10–99 fpm), mean band 4.375 (0.375 fpm); and SD-4 from band 3 (0.01–0.099 fpm) to band 6 (10–99 fpm), mean band 4.375 (0.375 fpm).

As for the Russian stimuli frequency, it was estimated based on the rate of instances per million words (imp.-the number of word tokes per million in the Russian National Corpus, RNC, www.ruscorpora.ru, accessed on 9 September 2021 a collection of texts of XIX-XXI). This frequency rate is stated in the Frequency Dictionary (Lyashevskaya and Sharov 2009). The groups of iconic stimuli contained the words with the following frequency rates: SD-1 from 0.4 imp to 11.1 imp, M = 2.8 imp; SD-2 from 0.6 imp to 16.0 imp, M = 5.3 imp; SD-3 from 0.8 imp to 11.7 imp, M = 4.2 imp; and SD-4 from 0.5 imp to 13.6 imp, M = 6.1 imp.

In contrast to the OED, the RNC does not contain word lemmas, but rather word tokens that increase its size up to circa 900 million tokens. Since the English and Russian frequency data are estimated on the basis of the corpuses that are different in size, they could not be compared. Also, as the corpus data shows, the more iconic a word is the less frequent it is. Therefore, the groups of English (M = 0.8 fpm, Band 4) and Russian (M = 6.2 imp) arbitrary words were collected among mid- and low-frequency words so that the mean frequency of these groups matched the mean frequency of the iconic groups of stimuli.

We also identified the orthographic neighborhood density of the stimuli. An orthographic neighbor is a word of the same length that differs from the original string by one letter. We systematically varied vowels and consonants in each word to determine the number of a word’s orthographic neighbors. For example, in the word ‘lid’, first, we varied the vowel to identify the number of neighbors; second, we varied the initial consonant, with the rest of the orthographic environment being kept constant, i.e., we searched for 3-letter words that ended in -id with the help of the online dictionary www.thefreedictionary.com accessed on 12 August 2021; finally, we conducted the same procedure with the last consonant.

All lexical stimuli were paired with non-words (N = 64 for each language). The non-words were created according to the phonotactic constraints of the language so that they behave according to the sound structure of the language and would not cause any recognition inaccuracies (Styles and Gawne 2017). In addition, each non-word stimulus followed the same segmental composition as the corresponding lexical word and did not include common phonesthemes, like br-, gr-, scr-, sl-, gl-, sm-, fl-, sn-, and sw-. The groups of arbitrary words and non-words were used as control stimuli.

The design of the experiment required the careful selection of experimental stimuli. First, the iconicity in a word was identified by applying the method of phonosemantic analysis, which was introduced by Voronin (2006). Only the words marked as ‘echoic’, ‘imitative’, ‘onomatopoeic’, or ‘mimetic’ in the etymology section were selected, with the exclusion of words marked as ‘dialectal’ and ‘obsolete’. Second, the iconic words were classified into four equal groups (N = 8 each) according to their stages of de-iconization (SD) by applying the method of the diachronic evaluation of the imitative lexicon (Flaksman 2017).

Though words with a different degree of iconicity circulate in the language simultaneously, they need to be investigated separately and not as a discrete unit. This (etymological) division gives us a clearer and more systematic picture of the perception of iconic words in unrelated languages. The ‘new’ words, i.e., interjections, (SD-1) could sometimes be confused with non-words since they are not yet lexicalized, while the ‘old’ ones (SD-4) are most likely to be indistinguishable from arbitrary words since they have lost both their original iconic form and meaning. It is noteworthy that in a synthetic language (Russian), iconicity loss, accompanied by the integration of a vivid iconic word (interjection) into the grammatical system of a language, inevitably entails word-class-changing inflection, e.g., Rus. xlop! (int.)—‘clap’, xlop-ok (N)—‘a clap’, xlop-a-t’ (V)—‘to clap’. This example also illustrates that, in English (an analytic language), the loss of iconicity does not necessarily involve the modification of a word form as conversion is a leading mechanism of word-formation in an analytic language. This language property, among other factors, may affect the process of lexical access. Table 1 and Table 2 present the total sets of the English and Russian experimental stimuli correspondingly.

Table 1.

English Experimental Stimuli.

Table 2.

Russian Experimental Stimuli.

As demonstrated, iconic words selected as stimuli are predominantly onomatopoeic words—some of them with an additional, mimetic component (Eng. fie). Words from phonaesthemic groups were excluded from the study due to the lack of phonaesthemic words in Russian. All the content stimuli were homomorphous, i.e., controlled for length (monosyllabic Russian words are on average 1.4 times longer than English words (Polikarpov 1997)), grammatical category (all nouns, except for the SD-1 group presented by new, most ‘vivid’ iconic interjections), and frequency (see Table 1 and Table 2). The mean overall frequency of the English and Russian iconic stimuli constitutes 0.22 per million words (low Band 4) and 5.3 imp., respectively. We have matched the stimuli for word frequency; however, it would have been impossible to match them for neighborhood density as well as take into consideration the challenging task of selecting the stimuli for four different SDs. The results of the follow-up check of the neighborhood density are presented in Table 1 and Table 2. They show that the mean neighborhood density of the English stimuli (2.8) is three times higher than that of the Russian stimuli (0.9). The mean neighborhood density of the English and Russian non-words is also quite different and constitutes 1.1 and 0.5, respectively. The stimuli were used in the psycholinguistic method of Lexical Decision (Meyer and Schvaneveldt 1971).

2.2. Participants

The participants for the experiment met the following criteria: age (18–55 y.o.), native speakers of English and Russian, respectively, having no obstacles to participation in a computerized study. The intended sample size was at least 50 participants to obtain valid data using a multivariate experimental plan with repeated measurements (Guo et al. 2013). A total of 156 subjects participated in the research: 106 native speakers of Russian (35 m, 71 f) aged between 18 and 50 (M = 23.75 years), and 50 native speakers of English (28 m, 22 f) from the UK (18), the US (27), and Canada (5) that were aged between 20 and 53 (M = 30.65 years). Each participant gave their written informed consent prior to participating in the study, reported taking no medications that could potentially affect their reaction time, having normal and corrected-to-normal vision, and no mental, psychiatric, and neurological disorders. At first, the data was collected on Russian-speaking subjects during the period from October to December of 2020. To attract the subjects to participate in the experiment, ads were placed on the Internet in social networks and in groups of student communities. The data collection on English-speaking subjects was carried out during the period from January to April of 2021. It turned out to be a difficult task to attract native English speakers to participate in the experiment, since people did not have confidence in the software that needed to be installed on their personal computers. Therefore, we had to contact 43 private language schools in St. Petersburg and Moscow, where native English speakers worked. A 7th of them were school authorities, and, after the consent of the native English speakers, provided us with their email addresses. Also, all friendly and working relationships with native English speakers living outside of Russia were activated in order to invite them to participate in the experiment. Therefore, the sample of native English-speaking subjects is much smaller than the one of Russian-speaking. Each participant was financially compensated with ₽1000 upon completion of the experiment by transferring the money to a personal bank account or through the Western Union payment system for foreign citizens. After receiving financial compensation, the subjects provided a receipt for received remuneration.

2.3. Procedure

All the information and data exchange between the experimenters and the subjects took place via email correspondence due to the global pandemic from COVID-19. Given these circumstances, the present study was designed as a computerized survey without face-to-face data collection. The experiment was carried out using the pre-installed computer system “Longitude”—a software elaborated for automated stimuli exposition in a randomized order during psychological experiments (Software Longitude, Version 19, production of LLC “Longitude”, St. Petersburg, Russia) (Miroshnikov 2011). The detailed participation instructions and informed consent forms, along with the software distributive, were sent to each participant by email. During the Lexical Decision session, all the stimuli were presented on the screen in random order one by one (see Table 1 and Table 2). The subject’s task was to identify as quickly and accurately as possible the presented stimulus as a word of their native language or a non-word by pressing the corresponding button on the keyboard. Identification time was restricted to 1000 ms. The experimental session was preceded by a training one, where 10 words and 10 non-words were presented in random order. The data was automatically saved upon completion of the experiment in the corresponding folder on the computer and a participant was given feedback on the number of right answers, mistakes, and belated reactions without further specification. The number of attempts to pass the experimental session was automatically reduced to one so that, on completion of the experimental session, the participant could not pass it again. We set such restrictions in order to avoid learning and biased data. If the participant was unhappy with his/her results and wanted to improve them due to his/her perfectionism, there was no such option available. Such additional control measures were due to the remote form of computerized data collection and, accordingly, the lack of the experimenter’s ability to control this process personally. Upon completing the experiment, each participant sent the file with the data to the research group and received a financial reward.

2.4. Data Analysis

Despite the fact that, at first, the data collected on Russian-speaking subjects were analyzed, and then the data collected on native English speakers were analyzed, the sequence of statistical data analysis for both stages of the study were identical. The IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp. Released 2017, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the data. The performance measures were response time (lexical decision time) and number of error responses. To compare the lexical decision time (LDT) to the different groups of stimuli (factor Parameter), only correct reaction times of up to 1000 ms were included in the analysis. First, we controlled for the effect of the factor Parameter on LDT, taking into account word frequency and orthographic neighborhood density in the between-subject design. Non-words were not included in the analysis at this step. We fitted the univariate ANOVA (Generalized Linear Model GLM: Univariate) model with the fixed factor Parameter (5 levels), dependent variable LDT, random factor Participant № (#case), and the covariates Frequency and Neighbors. Such an analysis allows for subtracting from the variance of the error of the dependent variable (residual variance) those parts of its variance resulting from the influence of between-subjects differences, as well as the influence of the word frequency and neighborhood density. It increases the effect size of the factor under study and its statistical power. The proportion of variance in the dependent variable as the effect size of this factor (covariates) is presented in the results as Partial Eta Squared (η2).

Post-Hoc pairwise comparisons of different levels of the factor Parameter were performed in Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) in the same manner, with the inclusion of only statistically significant effects. The Bonferroni adjustment was used for multiple comparisons. The use of more complex GLMMs is more appropriate since GLMs do not allow for Post-Hoc pairwise comparisons if covariates are included in the analysis. On the other hand, the GLMM is not used to calculate the effect size (η2) of the factors and covariates.

The non-word stimuli were included in the second step of the analysis. Similarly, the univariate ANOVA (GLM: Univariate) model was performed, with LDT as the dependent variable, Parameter as the fixed factor (6 levels), and Participant № (#case) as a random factor. In addition to the pairwise comparisons of the previous step, the Simple Contrast method was used to compare the level of non-words with each of the other five levels. Error analysis was performed as the final step of our data analysis. For that purpose, a Chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of the measures for iconic words at different stages of de-iconization, as well as arbitrary words and non-words.

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy

The frequencies of delays and correct and erroneous reactions for different types of stimuli are shown in Table 3 (English-language sample) and Table 4 (Russian-language sample).

Table 3.

Contingency table Parameter*Accuracy for the English-language Sample.

Table 4.

Contingency table Parameter*Accuracy for the Russian-language Sample.

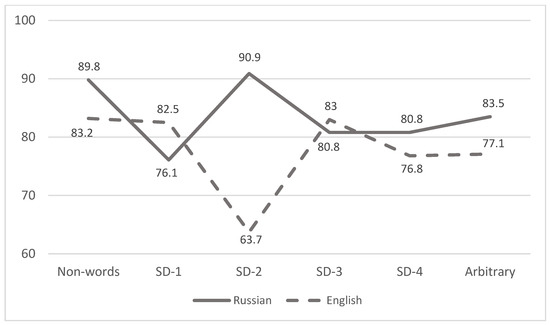

The difference in response accuracy (RA) between iconic and arbitrary words was statistically significant for neither Russian (χ2 = 3.539; df = 2; p = 0.170) nor English (χ2 = 0.144; df = 2; p = 0.931) participants. The effect was tested for each SD group. Figure 1 presents the results for Russian (solid line) and English (dashed line) native speakers.

Figure 1.

Accuracy rates for visual recognition of the English and Russian stimuli.

3.2. Lexical Decision Time

To compare the reaction time of word recognition, only correct reactions were taken into account: erroneous reactions and delays from 1000 ms and above were excluded from the statistical analysis of LDT (lexical decision time). The proportion of the remaining (correct) reactions, depending on the type of stimulus and the sample, ranged from 63.7% to 90.9% (statistics that show comparison of the reaction time to non-words and target stimuli in English and Russian, page 14). Descriptive statistics for lexical decision reaction time are presented in Table 5 and Table 6. Descriptive statistics for the covariates Frequency and Neighbors are presented in Table 7.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for the Reaction Time to the English Stimuli Depending on Their Type.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics for the Reaction Time to the Russian Stimuli Depending on Their Type.

Table 7.

Descriptive statistics for covariates Frequency and Neighborhood density (ND).

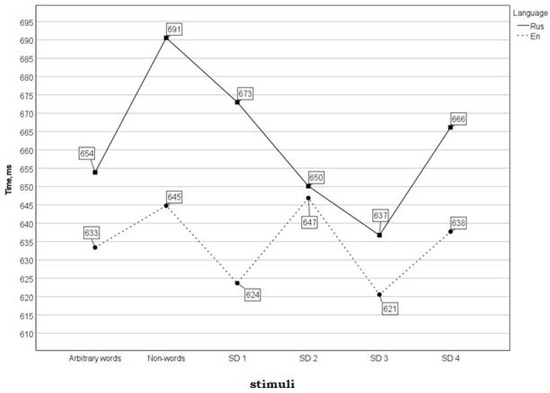

Figure 2 below shows the mean reaction time (in ms) of word recognition for Russian (solid line) and English (dashed line) native speakers.

Figure 2.

Word recognition time (in ms) depending on the type of the stimuli in Russian and English.

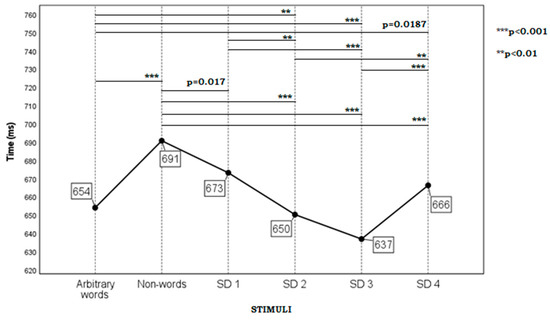

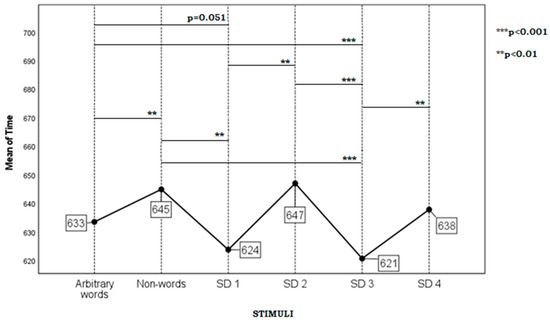

Figure 3 and Figure 4 below show the average reaction time (in ms) of word recognition with a demonstration of the statistical significance for Russian and English stimuli, respectively.

Figure 3.

Word recognition time (in ms) depending on the type of the stimuli in Russian.

Figure 4.

Word recognition time (in ms) depending on the type of the stimuli in English.

For the English-speaking sample, we got statistically significant results for the first step of the analysis: the main effects of the factor Parameter (F (4; 269.514) = 5.809; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.079), the covariate Frequency (F (1; 2205) = 32.002; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.014), and the factor #case (F (49; 287.106) = 12.065; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.673). The effect of the covariance Neighbors (F (1; 2205) = 0.559; p = 0.455) and the effect of the interaction of the factors Parameter and #case (F (196; 2205) = 0.983; p = 0.555) turned out to be statistically insignificant. The statistical significance and effect size of Parameter on LDT were significantly higher with Frequency taken into account (p < 0.001; η2 = 0.079) than without it (p = 0.064; η2 = 0.039). The results of Post-Hoc pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 8. The effect of the factor Parameter explains 7.9% of the LDT variance, the effect of the covariate accounts for 1.4% of its variance, and the effect of the between-subjects differences (factor #case) accounts for 67.3% of its variance.

Table 8.

Statistically significant results of Post-Hoc pairwise comparisons for the levels of the factor Parameter (English-speaking sample).

The differences in 5 out of 10 pairs of stimuli were statistically significant: Arbitrary words–SD3, SD1–SD2, SD2–SD3, and SD3–SD4. The differences in the pair Arbitrary words–SD1 were only slightly below statistical significance. For the Russian-speaking sample, we got the following statistically significant results of the first step: the main effects of the factor Parameter (F (4; 464.691) = 10.996; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.086), the covariate Frequency (F (1; 5086) = 103.805; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.020), and the factor #case (F (105; 580,045) = 8.370; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.602). The effect of the covariance Neighbors (F (1; 5086) = 0.242; p = 0.623) and the effect of the interaction of the factors Parameter and #case (F (420; 5086) = 1.103; p = 0.081) turned out to be statistically insignificant. Statistical significance and the effect size of Parameter on LDT with Frequency taken into account turned out to be the same (p < 0.001; η2 = 0.086) as without it (p < 0.001; η2 = 0.087). The results of Post-Hoc pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 9. Statistically significant differences were found in 8 out of 10 pairs of stimuli.

Table 9.

Statistically significant results of Post-Hoc pairwise comparisons for the levels of the factor Parameter (Russian-speaking sample).

Thus, statistical significance and the size effects of the factors and covariates are nearly identical for the English- and Russian-speaking samples. Noticeable differences between the samples are observed in pairwise comparisons of mean LDTs for different types of stimuli.

The results of the analysis of univariate ANOVA (GLM: Univariate) with the addition of the level Non-words for the English sample are as follows: the effect of the factor Parameter F (5; 263,240) = 4.694; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.082; the effect of the factor #case F (49; 640.226) = 14.292; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.522; and the effect of the interaction of the factors Parameter and #case F (245; 4819) = 1.032; p = 0.354. The results of the application of the Simple Contrast method (F (5; 4819) = 4.840; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.005) are presented in Table 10. In 3 out of 5 pairs of stimuli the differences were statistically significant.

Table 10.

Comparison of the Reaction Time to Non-Words and Target Stimuli in English.

The results of the analysis of univariate ANOVA (GLM: Univariate) with the addition of the level Non-words for the Russian sample are as follows: the effect of the factor Parameter F (5; 537.715) = 52.193; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.327; the effect of the factor #case F (105; 945,700) = 7.492; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.454; and the effect of the interaction of the factors Parameter and #case F (525; 11071) = 1.841; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.454. The results of the application of the Simple Contrast method (F (5; 11,071) = 95,145; p < 0.001; η2 = 0.041) are shown in Table 11. The differences were statistically significant (p < 0.001) in all five pairs of stimuli.

Table 11.

Comparison of the Reaction Time to Non-Words and Target Stimuli in Russian.

3.2.1. Iconic/Arbitrary Words

For the English groups SD-1 (χ2 = 8.239; df = 2; p = 0.016) and SD-3 (χ2 = 9.632; df = 2; p = 0.008), the effect was significant: the RA for these iconic words was higher than that for arbitrary words. The effect was also significant for the English SD-2 group (χ2 = 33.587; df = 2; p = 0.0001), however, the accuracy was lower. The result was not statistically significant for the English SD-4 group (χ2 = 1.390; df = 2; p = 0.499). The RA for the Russian SD-1 group (χ2 = 26.001; df = 2; p < 0.001) was significantly lower than that for arbitrary words. For the Russian SD-2 group, the RA was significantly higher than that for arbitrary words (χ2 = 28.953; df = 2; p < 0.001). For the Russian SD-3 and SD-4 groups, the result was not statistically significant (χ2 = 3.902; d = 2; p = 0.142).

3.2.2. Iconic/Non-Words

The RA for the English non-words was higher than that for all groups of the English iconic words taken together (χ2 = 36.190; df = 2; p < 0.001). It was higher than that for the SD-2 (χ2 = 104.280; df = 2; p <0.001) and SD-4 (χ2 = 17.153; df = 2; p < 0.001) groups, but it did not differ significantly from the groups SD-1 (χ2 = 0.482; df = 2; p = 0.786) and SD-3 (χ2 = 0.531; df = 2; p = 0.767). The recognition of the English words from the SD-2 and SD-4 groups was the least accurate when compared with non-words. The RA for the Russian non-words was higher than that for the groups SD-1 (χ2 = 149.321; df = 2; p < 0.001), SD-3 (χ2 = 81.730; df = 2; p < 0.001), and SD-4 (χ2 = 71.179; df = 2; p < 0.001). It was not statistically different from the SD-2 group (χ2 = 3.677; df = 2; p = 0.159).

3.2.3. Non-Words/Arbitrary Words

The English participants performed better on non-words than on arbitrary words (χ2 = 31.100; df =2; p < 0.001). The RA for Russian arbitrary words was lower than that for non-words (χ2 = 393.883; df = 2; p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

First of all, it is worth emphasizing that our independent variables taken into account in the analysis had different effects on the results. Neighborhood density had no statistically significant effect on the results, while accounting for the frequency of the words allowed us to take into account a significant proportion of the variance of the dependent variable, thereby making the effect of distinguishing between stimuli more pronounced. We hypothesized that the most explicit iconic Russian words would be recognized more slowly and less accurately than the other content words by native speakers of Russian (H1). According to our second hypothesis (H2) we expected similar recognition patterns in both Russian and English speakers concerning explicit iconic words (SD-1 and SD-2) even though the results of previous studies suggested that English iconic words are recognized faster (Sidhu et al. 2020), and we assumed that a degree of iconicity plays a crucial role and iconicity itself is a general language feature. It appeared that indeed the most explicit iconic Russian words (SD-1) are recognized slower than all other words, and less accurately as well. However, Russian words belonging to SD-2 are recognized faster and the most accurately in comparison with all other words. As for the words of SD-3, they are recognized faster and with more accuracy corresponding to arbitrary words. SD-4 words are recognized similarly to arbitrary words within the parameters of speed and accuracy. Given this, our first hypothesis is confirmed. We can state that native speakers of Russian show a high sensitivity to the most explicit iconic words. However, less explicit iconic words (SD-2, SD-3, SD-4) differ significantly in the patterns of their recognition from SD-1 and the tendency is, the lesser iconicity, the closer they are to arbitrary words in terms of the speed and accuracy of their recognition. We suppose that SD-1 words are recognized slowly and less accurately due to the cognitive complexity of the task connected with the necessity for decoding the information on both lexical and figural levels. It is likely that the most explicit iconic words activate the cross-modal interaction, which happens when linguistic stimuli contain multiple acoustic and articulatory features and thus the process of recognition of such stimuli involves the integration of inputs across modalities. Given this, Parise (2016) in his review compares sound symbolic associations and cross-modal correspondences, thereby supposing that they are related to each other. In our case, all SD-1 Russian words are directly associated with movements that distinguish them from other stimuli, so presumably their perception includes visual-motor cross-modal interactions and this process is reflected in the time delay of LDT and the inaccuracies of their recognition.

However, for English stimuli, the different results are obtained. It appears that, paradoxically, SD-1 words are recognized faster and more accurately than arbitrary words and words belonging to SD-2 and SD-4. At the same time, SD-2 words are recognized the most slowly and the least accurately than all other words. SD-3 words are recognized the fastest and as accurately as SD-1 words. As well, SD-4 words are recognized similarly to arbitrary words within the parameters of speed and accuracy, which eventually coincides in the recognition of patterns with the same type of Russian stimuli (SD-4). Given this, and concerning the second hypothesis, our results showed that the differences in the recognition of iconic words in Russian and English are rather language-specific and there is no similarity in the recognition patterns except for words belonging to the SD-4 group. It is noteworthy that our results concerning the most explicit iconic English words (SD-1) go along with the results of previous studies in which it was shown that iconic words are recognized faster (Sidhu et al. 2020). It should be noted that English words of SD-1 are very different from Russian words of SD-1, since they are related to the emotional component, while Russian words, as mentioned above, are associated with movement. It is likely that there are various neurocognitive mechanisms behind the perception of these words, which may cause such a difference in the speed and accuracy of LDT. Concerning SD-2 English words, which are recognized the most slowly and the least accurately—even less accurately than non-words—the results could be attributable to their grammatical ambiguity. English words like buzz or puff can function as (1) interjections, (2) nouns, and (3) verbs. For example, puff is (1) an interjection representing ‘the act of blowing a puff of air, smoke’, (2) a noun referring to ‘the action of puffing’, and (3) a verb with the meaning ‘to blow out (air, one’s breath, smoke, etc.) (OED). This structural ambiguity might have caused hesitation in categorizing these stimuli as ‘words’ or ‘non-words’. Moreover, the SD-2 group is characterized by the lowest accuracy rate (63.7), both among the English and Russian stimuli.

As for the group of non-words, it was used to balance word decisions with non-word decisions. The non-words were constructed according to the phonotactic constraints of the English and Russian languages, correspondingly. Moreover, they contained legal letter strings so that they were pronounced as regular English/Russian words. Rather, the results showed the general language tendency to the more accurate and slower recognition of non-words in comparison with the iconic stimuli taken together.

Overall, the results show different recognitions of English and Russian iconic words at different stages of de-iconization, except for SD-4 words. The English participants recognized the words at SD-1, SD-3, and SD-4 at roughly the same speed. However, we observe a different pattern in the responses of the Russian subjects: the RT decreased starting with non-words through SD-1 to SD-3 group, i.e., the more de-iconized a word is, the faster it is identified. Surprisingly, however, there was a sudden increase in RT to the most de-iconized words at SD-4 as presented in Figure 2. Presumably, this could be attributed to the fact that this group included three borrowed words (lunch, putsch, and puff) that were recognized slower and with a greater number of mistakes than the other words, which might have affected the speed and accuracy of the word recognition of the whole group. The overall RA to all stimuli groups was rather high for both participants groups: 80% in the responses of the English participants; for the Russian participants, the RA was higher for non-words and the SD-2 group (ca. 90%); and for the other stimuli groups, the mean accuracy was 80%. This might serve as an indication that, along with orthographic and phonological representation, the participants activated the semantic code.

Recent research (Sidhu et al. 2020; Aryani et al. 2019) has provided evidence for the facilitative role of iconicity in language processing. Since iconic words possess a more direct link between phonology and semantics, their processing is argued to be faster. This could be one of the factors that influenced the responses of the English participants. Despite the fact that the words at SD-1 are difficult to categorize into one of the major word classes, they were recognized as quickly as SD-3 and SD-4 stimuli, and even faster than SD-2 words. However, here arises the question as to why the Russian native speakers did not demonstrate the same pattern with regard to this group of stimuli. A possible speculative explanation can be proposed based on the frequency of SD-1 words in written texts. Also, it should be noted that in English, unlike Russian, there is a large number of semantically ambiguous words (i.e., words with more than one meaning) that are processed and represented differently in the human mind (Eddington and Tokowicz 2015).

It is important to mention that most research on iconicity rationally focuses on auditory perception, since iconic words, at least explicit iconic words at SD-1, are mostly used in informal everyday speech. The current study is one of the few studies to provide insight into the visual perception of iconic words. Although we have controlled for the word frequency of the stimuli, it would be advantageous to control for the word frequency in written contemporary texts, i.e., words that appear the most in printed language are easier to recognize than words that appear less frequently (Grainger 1990). The study by Kalman and Gergle (2014) has revealed the relatively high written frequency of interjections (which correspond to SD-1 words in our study) in computer-mediated communication (CMC) in English. They explored letter repetitions as a CMC cue from a collection of emails. Their findings revealed that many of the repetitions were onomatopoeic words (e.g., Boommm! Craaash! Ooops!), which were used to imitate spoken non-verbal cues. Another study, which focused on the subtitles of British television programs, revealed that they often contain “typos and other non-word-like structures (like aaaarrrrgh or zzzzzzzzzzzz)” (Van Heuven et al. 2014). Such examples are representatives of ‘new’ imitative SD-1 words, which shows that such rare lexis is visually presented in subtitles quite frequently. In these words, letter repetition indicates gemination (consonant lengthening) or vowel lengthening, both of which are typical traits of ideophones (Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz 2001) and SD-1 onomatopoeic interjections (Flaksman 2015). We assume that we might observe these frequency effects in the performance of the English participants. To our knowledge, there are no similar studies in Russian therefore it is problematic to draw conclusions in this respect. Word prevalence (i.e., the number of people who know the word) might be an additional factor to explain the fact that some low-frequency words are recognized as quickly and accurately as high-frequency words are (Brysbaert et al. 2019). These observations may account for the significant delay in the recognition of words at SD-1 in Russian.

Last, but not least, we should take into consideration the differences between individuals in terms of their cognitive abilities, for example, in the degree of semantic reliance. There are also the psycholinguistic features of target word stimuli to consider such as familiarity, imageability, emotional valence, and emotional arousal, which can affect the process of visual recognition when filled with an individual meaning for the participant (Citron et al. 2014). The task in the current study was to answer as quickly and accurately as possible, emphasizing speed over accuracy. It means that subjects should rather rely on orthographic code, which results in faster responses to words with more neighbors (Binder et al. 2003). However, if some of the subjects chose to put greater emphasis on accuracy (in which case we observe a reverse picture: responses to words with few or no neighbors are faster), a somewhat different explanation for the response patterns could be provided. If this was the case with our English participants, for example, this could partially account for their response pattern (the SD-2 group was the lowest to recognize among all SD-groups, with the mean number of neighbors of 2.1).

5. Conclusions

The current findings add to a growing body of literature on the visual perception of iconic words. We present evidence that although iconicity is universal in nature, the processing of iconic words is different across languages—speakers of two typologically different languages, Russian and English, are not equally sensitive to iconicity. Whereas the degrees of de-iconization are recognized by the Russian participants who tended to respond slower and less accurately to the words higher in iconicity, the results of the English-speaking participants cannot be explained by reference solely to the presence or the degree of iconicity. The only group of English words that caused some difficulties in classifying them as words or non-words was the SD-2 group, which were explicit imitative words that have not yet lost their original meaning and form. It is necessary to take into consideration such additional factors as the meaning of sound symbolic words, their systematic associations with different sensory modalities, familiarity, imageability, emotional valence, and emotional arousal, along with word frequency, written word frequency, word prevalence, etc. Although iconicity is argued to contribute to language processing, our findings do not provide much evidence for general processing enhancement. First, we need to be specific and distinguish between the auditory and visual perception of iconic words. Second, we need to take into consideration the cross-linguistic differences in the distribution of iconic words.

Further research in this field might explore the simultaneous process of the auditory and visual perception of iconicity and compare how visual information affects the processing of auditory information and vice versa. In light of the importance of the instruction as implied by Binder et al. (2003), namely, to answer either quickly or accurately, which can lead to different results, we recommend that future research specifically addresses this issue and examines the impact of different instructions on RT and RA in the lexical decision task. Data obtained from an experimental group(s) with different instructions would provide a more reliable and accurate measure of iconic words recognition and an interesting comparison to the findings of the present paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and Y.S.; methodology, Y.L., Y.S., L.T. and M.F.; software, A.N.; validation, A.N.; formal analysis, A.N.; investigation, E.K.; resources, Y.L., Y.S. and M.F.; data curation, E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L., Y.S., L.T. and M.F.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., Y.S., L.T. and M.F.; visualization, A.N.; supervision, L.T.; project administration, L.T.; funding acquisition, L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by RFBR, grant No. 20-013-00575 “Psychophysiological indicators of the perception of sound symbolic words in native and foreign languages”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to no disclosure of any personal information.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: [https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1nDKB8s1KPCkiXR6SrbxN49qZMyOta20M?usp=sharing] (5 October 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Akita, Kimi, and Prashant Pardeshi, eds. 2019. Ideophones, Mimetics and Expressives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Aryani, Arash, Chun-Ting Hsu, and Arthur M. Jacobs. 2019. Affective iconic words benefit from additional sound–Meaning integration in the left amygdala. Human Brain Mapping 40: 5289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartens, Angela. 2000. Ideophones and Sound Symbolism in Atlantic Creoles. Helsinki: Gummerus Printing Saarjärvi. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, Jeffrey R., Kristen McKiernan, Melanie Parsons, Chris Westbury, Edward Possing, Jacqueline Kaufman, and Lori Buchanan. 2003. Neural correlates of lexical access during visual word recognition. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 15: 372–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasi, Damián E., Søren Wichmann, Harald Hammarström, P. F. Stadler, and Morten H. Christiansen. 2016. Sound–Meaning association biases evidenced across thousands of languages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113: 10818–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brysbaert, Marc, Paweł Mandera, Samantha F. McCormick, and Emmanuel Keuleers. 2019. Word prevalence norms for 62,000 English lemmas. Behavior Research Methods 51: 467–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Citron, Francesca, Brendan Weekes, and Evelyn Ferstl. 2014. How are affective word ratings related to lexicosemantic properties? Evidence from the Sussex Affective Word List. Applied Psycholinguistics 35: 313–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connell, Louise, and Dermott Lynott. 2012a. Strength of perceptual experience predicts word processing performance better than concreteness or imageability. Cognition 125: 452–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connell, Louise, and Dermott Lynott. 2012b. When does perception facilitate or interfere with conceptual processing? The effect of attentional modulation. Frontiers in Psychology 3: 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dingemanse, Mark, Marcus Perlman, and Pamela Perniss. 2020. Construals of iconicity: Experimental approaches to form–meaning resemblances in language. Language and Cognition 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eddington, Chelsea M., and Natasha Tokowicz. 2015. How meaning similarity influences ambiguous word processing: The current state of the literature. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 22: 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flaksman, Maria. 2013. Preservation of long vowels in onomatopoeic words denoting pure tones: Phonosemantic inertia. Paper presented at Joseph M. Tronsky XVII Memorial Annual International Conference Indo-European Comparative Linguistics and Classical Philology, Saint-Petersburg, Russia, June 24–26; Edited by Kazansky Nikolaj. St. Petersburg: Nauka, pp. 917–23. [Google Scholar]

- Flaksman, Maria. 2015. Diachronic Development of English Iconic Vocabulary. Ph.D. thesis, University of St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg, Russia. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Flaksman, Maria. 2016. A Dictionary of English Iconic Words on Historical Principles. St. Petersburg: Institute of Foreign Languages/RHGA. [Google Scholar]

- Flaksman, Maria. 2017. Iconic treadmill hypothesis. Dimensions of Iconicity. Iconicity in Language and Literature 15: 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaksman, Maria. 2020. Some preliminary remarks on de-iconization of the Russian imitative lexicon. Current Issues in Linguistics 9: 262–67. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Flaksman, Maria A., Yulia V. Lavitskaya, Yulia G. Sedelkina, and Liubov O. Tkacheva. 2020. Stimuli Selection Criteria for the Experiment “Visual Perception of Imitative Words in Native and Non-Native Language by the Method Lexical Decision”. Discourse 6: 97–112. (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitt, Werner. 2006. In the Beginning Was Information. Green Forest: Master Books. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, Jonathan. 1990. Word frequency and neighborhood frequency effects in lexical decision and naming. Journal of Memory and Language 29: 228–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Yi, Henrietta L. Logan, Deborah H. Glueck, and Keith E. Muller. 2013. Selecting a sample size for studies with repeated measures. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hinton, Leanne, Johanna Nichols, and John J. Ohala, eds. 1994. Sound Symbolism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, Mitsumi, and Sotaro Kita. 2014. The sound symbolism bootstrapping hypothesis for language acquisition and language evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 369: 20130298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johansen, Jorgen Dines. 1993. Dialogic Semiosis: An Essay on Signs and Meaning; Indiana University Press. Available online: https://ur.hk1lib.org/book/2076725/624bbd (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Joo, Ian. 2020. Phonosemantic biases found in Leipzig-Jakarta lists of 66 languages. Linguistic Typology 24: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, Yoram, and Darren Gergle. 2014. Letter repetitions in computer-mediated communication: A unique link between spoken and online language. Computers in Human Behavior 34: 187–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, Shigeto. 2020. Sound symbolism and theoretical phonology. Language and Linguistics Compass 14: e12376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleva-Zlateva, Zhivka. 2008. Slavonic words of phonoiconic origin. Studia Slavica Hungarica 53: 381–95. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Lyashevskaya, Olga N., and Sergey A. Sharov. 2009. Frequency Dictionary of the Modern Russian Language. Moscow: Azbukovnik, Available online: http://dict.ruslang.ru/freq.php (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Meyer, David E., and Roger W. Schvaneveldt. 1971. Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval operations. Journal of Experimental Psychology 90: 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miroshnikov, Sergey A. 2011. Methodical Materials for the Psychological Research Software Package. St. Petersburg: LEMA. [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan, Padraic, and Matthew Fletcher. 2019. Do sound symbolism effects for written words relate to individual phonemes or to phoneme features? Language and Cognition 11: 235–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, Alan K., and Mark Dingemanse. 2021. Iconicity in word learning and beyond: A critical review. Language and Speech 64: 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxford English Dictionary. 2020. Available online: https://www.oed.com (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Östling, Robert, Carl Börstell, and Servane Courtaux. 2018. Visual iconicity across sign languages: Large-scale automated video analysis of iconic articulators and locations. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Parise, Cesare V. 2016. Crossmodal correspondences: Standing issues and experimental guidelines. Multisensory Research 29: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, Lynn K., Marcus Perlman, and Gary Lupyan. 2015. Iconicity in English and Spanish and Its Relation to Lexical Category and Age of Acquisition. PLoS ONE 10: e0137147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikarpov, Anatoliy A. 1997. Some factors and regularities of analytic/synthetic development of language system. Paper presented at the XIII International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Düsseldorf, Germany, August 10–17; Available online: http://www.philol.msu.ru/~lex/articles/fact_reg.htm (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Ramachandran, Vilayanur Subramanian, and Edward. M. Hubbard. 2001. Synaesthesia: A window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies 8: 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shliahova, Svetlana S. 2004. Drebezgi yazyka: Slovar’ russkijh fonosemanticheskikh anomalii [Shards of Language: A Dictionary of Russian Phonosemantic Abnormalities]. Perm: Perm Pedagogic University Press. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu, David M., and Penny M. Pexman. 2018a. Five mechanisms of sound symbolic association. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 25: 1619–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sidhu, David M., and Penny M. Pexman. 2018b. Lonely sensational icons: Semantic neighbourhood density, sensory experience and iconicity. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 33: 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, David M., and Penny M. Pexman. 2019. The sound symbolism of names. Current Directions in Psychological Science 28: 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, David, Gabriella Vigliocco, and Penny Pexman. 2020. Effects of iconicity in lexical decision. Language and cognition 12: 164–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stekauer, Pavol, Renáta Gregová, Zuzana Kolaříková, Lívia Körtvélyessy, and Renáta Panocová. 2009. On phonetic iconicity in evaluative morphology. In Languages of Europe’ in Culture, Language and Literature Across Border Regions. Krosno: PWSZ, pp. 123–32. [Google Scholar]

- Styles, Suzy J., and Lauren Gawne. 2017. When does Maluma/Takete fail? Two Key Failures and a Meta-Analysis Suggest that Phonology and Phonotactics Matter. i-Perception 8: 2041669517724807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tkacheva, Liubov O., Yulia G. Sedelkina, and Andrey D. Nasledov. 2019. Possible cognitive mechanisms for identifying visually-presented sound-symbolic words. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art 12: 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heuven, Walter J., Pawel Mandera, Emmanuel Keuleers, and Marc Brysbaert. 2014. SUBTLEX-UK: A new and improved word frequency database for British English. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 67: 1176–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vasmer, Max Julius Friedrich. 2009. Russisches Etymonogisches Worterbuch. Translated by Trubachev. Moscow: O.n., Astrel’. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, Nicolas, Olivier Corneille, and Paula M. Niedenthal. 2008. Sensory load incurs conceptual processing costs. Cognition 109: 287–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voeltz, Friedrich Karl Erhard, and Christa Kilian-Hatz, eds. 2001. Ideophones. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Voronin, Stanislav V. 2006. The Fundamentals of Phonosemantics. Moscow: Lenand. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Winter, Bodo, Marcus Perlman, Lynn K. Perry, and Gary Lupyan. 2017. Which words are most iconic? Iconicity in English sensory words. Interaction and Iconicity in the Evolution of Language. Interaction Studies 18: 443–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).