Language Norm and Usage Change in Catalan Discourse Markers: The Case of Contrastive Connectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Broadly speaking, a convention is a pattern of behavior shared throughout a community and can be defined as the outcome that everyone expects in interactions that allow two or more equivalent actions (e.g., shaking hands or bowing to greet someone).

2. Internal and External Factors of Change

2.1. Paradigmatic Relations and Bilingual Context

2.2. Historical Background: The Codification of Catalan

| 1906 | First International Conference on the Catalan Language (Congrés internacional de la llengua catalana) |

| 1907 | Creation of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans, the Catalan Academy for Sciences and Arts |

| 1911 | Creation of Secció Filològica (Philology Section) of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans, a branch devoted to the establishment of the norm and the study of Catalan |

| 1912 | Publication of Pompeu Fabra’s Gramática de la lengua catalana (written in Spanish) |

| 1913 | Publication of a unified orthography (Normes Ortogràfiques) |

| 1918 | Publication of Fabra’s Gramàtica de la llengua catalana, adopted in 1933 as the official normative grammar by the Catalan Academy, IEC |

| 1932 | Publication of the official dictionary, Diccionari de la llengua catalana, written by Pompeu Fabra and adopted as normative by IEC |

With the Republican revolution in April 1931, the Catalan language obtained the legal recognition that it had been lacking for more than two centuries. The Statute of Autonomy voted for by the Catalan people established it as the only official language for internal purposes, although the text finally approved by the Spanish Parliament would see it share official status with Spanish.

…by 1930 there were 27 newspapers being published in correct and corrected Catalan. There were also two radio stations broadcasting in the language of the country.

Although the refinement ‘is still unfinished’ (“encara està inacabada”) and its dissemination ‘was just beginning’ (“tot just comença”), Fabra concluded his speech in front of the most conservative audience of Catalanism by saying ‘today we can be glad to have achieved not only this orthographic unity, but also that linguistic unity which has made possible to elevate Catalan to the official Language of Catalonia […].

3. The Origin and Evolution of Catalan Contrastive Connectives: Previous Contributions

…com és sabut, no res menys ha estat usat molt, en el català modern, com a conjunció adversativa, ús que nosaltres hem combatut i que sembla, en fi, comptar ja amb ben pocs partidaris, almenys entre els bons escriptors, que, com a rèplica a les conjuncions del tipus nientemeno, néanmoins, semblen ja preferir no gens menys a no res menys.(Fabra 1926; apud Mir and Solà 2011, p. 747)

…as generally known, no res menys has been very much used in Modern Catalan as an adversative conjunction, which we have fought against, and now it seems to have very few supporters, at least among good writers, who, as a correspondence to conjunctions of the type nientemeno, néanmoins, already seem to prefer no gens menys rather than no res menys.

- (a)

- No obstant constructions are first documented in 12th century texts in Latin.

- (b)

- Most Western Romance languages incorporate this marker almost simultaneously, by the second half of the 14th century, e.g., Spanish no obstante, Italian nonostante, French nonobstant, and Portuguese não obstante (Garachana 2019b, pp. 141–42). In the case of Catalan, the first attested occurrence is a 14th century translation of Boccaccio’s Il Corbaccio. The fact that the Romance developments, except for Italian, do not follow the general phonetic evolution, implying the simplification of consonants (bs > s), but keep the Latin structure, is a strong argument for considering its introduction as a grammatical calque, as opposed to a grammaticalization process, which usually implies phonetic reduction and adaptation to the phonetic system of the target language.

- (c)

- Constructions with no obstant spread from theological texts to law texts—most lawyers were also clergymen—because they were a useful rhetorical device in argumentation and gave a ‘Latin-like’ flair to the text, which was fashionable in 14th and 15th century texts (Garachana 2019a, p. 156; in print: Section 38.5.2.4).

Per tant, a la darreria dels segles xix–xx, dels dos valors vius de tanmateix [confirmació] [contrast]—s’incorpora al model normatiu el segon. No es tracta pas d’una creació ex novo del llenguatge literari català, sinó de la potenciació d’un dels matisos en joc que, en última instància, corresponia a una cadena “natural” de valors des d’antic: des del valor de [càlcul] fins al valor de [contrast]

Therefore, by the end of the 19th–20th centuries, one of the two actual values of tanmateix [confirmation] [contrast] is incorporated to the norm model, namely, the second one. It is not an ex novo creation of Catalan literary language, but the promotion of one of the nuances at play, which, all in all, corresponded to an old ‘natural’ chain of meanings: from the meaning of [calculation] to the meaning of [contrast].

4. The Study

4.1. Materials and Methodology

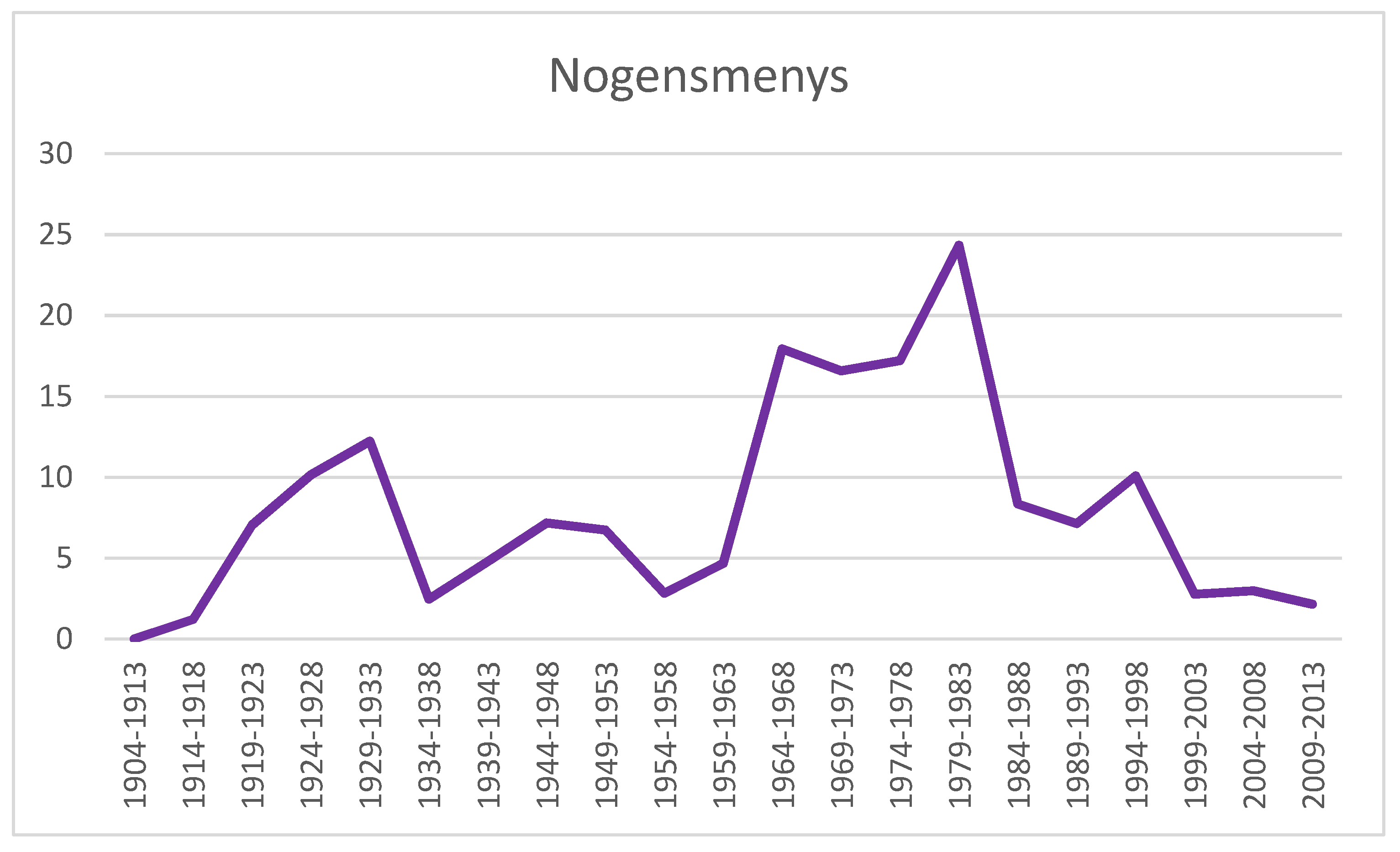

4.2. The Rise and Fall of Nogensmenys

| (1) | Ha quedat sense resoldre la situació de Zangskar, ja que és territori eminentment budista però s’administra des de Kargil. Nogensmenys, a totes tres regions es parlen dialectes tibetans, però només existeix tradició culta escrita a les zones budistes. (Alay, Josep Lluís: Tibet, el país de la neu en flames, 2010) |

| The situation in Zangskar remained unsolved, as it is an eminently Buddhist territory but it is administered from Kargil. Nogensmenys (‘however’), Tibetan dialects are spoken in all three regions, but there is a formal written tradition only in Buddhist areas. | |

| (2) | Abans, l’arribada del seu pare sempre era per Mila motiu d’alegria: ara fins la seva arribada l’entristí. Ell, nogensmenys, no digué res. (Juan Arbó, Sebastià: Tino Costa, 1947) |

| Earlier her father’s arrival was always a cause for joy for Mila: now even his arrival saddened her. He, nogensmenys (‘nonetheless’), said nothing. | |

| (3) | a. Si un home té una esposa lletja a més no poder, i nogensmenys li sembla que podria competir amb la mateixa Venus, ¿no seria igual que si fos verament bella? (Medina i Casanovas, Jaume: Elogi de la follia, 1982) |

| If a man has a very ugly wife, and nogensmenys (‘yet’) he thinks she could compete with Venus herself, wouldn’t it be as if she was really beautiful? | |

| b. L’Església catòlica —ens diu Walter de Hert— considerava els joglars frívols i massa mundans però, nogensmenys, en tolerava l’aparició en festes religioses perquè, en aquella època, garantien un públic nombrós. (Racionero, Lluís: El discurs, 1987) | |

| The Catholic Church—Walter de Hert reports—considered the minstrels frivolous and too mundane, but, nogensmenys (‘nevertheless’), tolerated their presence at religious festivals because, at that time, they guaranteed a large audience. |

| (4) | nogensmenys |

| 1. [ADVno grad V1]; [V1 ADVno grad] Tanmateix1. […] | |

| 2. [ADVno grad] A més1 (loc.). […] | |

| 3. [V1 ADVno grad (que N2)] Ni més ni menys1 (loc.). […] | |

| 4. [ADVno grad] No-res-menys4. […] (DDLC) |

| (5) | La gent de Garba observava respectuosa, de cua d’ull: només entrellucat, sever i llunyà, corbata de nus ben ample i botines de xarol, el cavaller era nogensmenys, sí, el Capità de l’Antonio López. (Porcel, Baltasar: Lola i els peixos morts, 1994) |

| The people of Garba watched respectfully, out of the corner of their eye: only entangled, stern and distant, a wide-knotted tie and patent leather boots, the gentleman was nogensmenys (‘nothing less’), yes, Captain Antonio López. |

| (6) | nogensmenys adv. [LC] Sense que sigui obstacle allò que s’acaba de dir o que queda sobreentès. […] (DIEC) |

Nogensmenys, tot i romandre en un àmbit d’ús altament formal, és una mostra d’una proposta d’incorporació d’un element nou en el moment d’elaboració de la norma del català contemporani normatiu i d’exclusió d’un altre element tradicional, el vell noresmenys.

Despite remaining as highly formal in use, nogensmenys illustrates a proposal to incorporate a new element at the time of elaboration of contemporary normative Catalan while excluding another traditional element, the old-fashioned noresmenys.

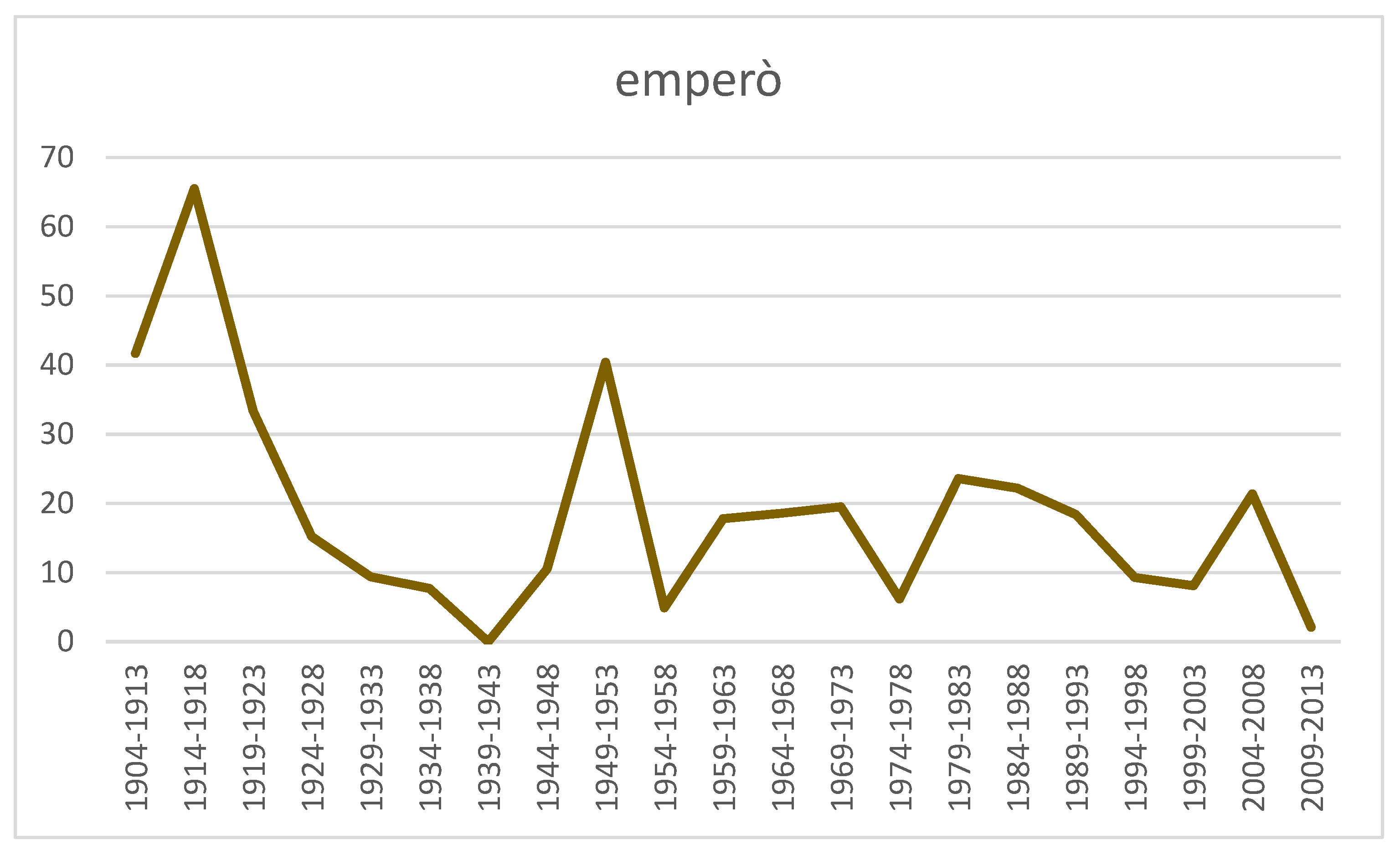

4.3. The Mysterious Case of Emperò

| (7) | a. I se n’entrava ell al campament. Emperò el jove servent seu, Josuè fill de Nun, romania dins la tenda. (Clascar, Frederic: L’Èxode, 1925) |

| And he went into the camp. Emperò (‘but’) his young servant Joshua, son of Nun, remained in the tent. | |

| b. El pantà de Canelles permet l’existència d’un salt de 96 m, emperò presenta l’inconvenient que perd part de les aigües per filtració per un fons de roques calcàries. (Vila, Marc-Aureli: Catalunya: rius i poblament, 1998) | |

| The Canelles reservoir allows for the existence of a water jump of 96 m, emperò (‘but’) it has the disadvantage of losing part of the water by filtration through limestone rocks at the bottom. | |

| (8) | a. Aquesta dificultat em confongué per bastant de temps. Crec, emperò, que pot ésser explicada en gran part. Albertí i Gubern, Santiago; Albertí, Constança: L’origen de les espècies, 1982) |

| This difficulty has been confusing me for quite some time. I think,emperò (‘however’), that it can be largely explained. | |

| b. No cal fer-se il·lusions, emperò. (Melià i Pericàs, Josep: Els mallorquins, 1967) | |

| We’d rather not deceive ourselves, emperò (‘however’). |

| (9) | emperò conj. [LC] Però 1, 2 i 3[…] (DIEC) |

Emperò tampoc no és dolent; però, en general, deuria preferir-se però, més popular i menys feixuc.(Fabra 1918, p. 217)

Emperò is not that bad, but, in general terms, però should be preferred, because it is more popular and less heavy.

Notem finalment, en català antic, la forma concurrent emperò, que en els Doc. apareix molt sovint en substitució de però intercalat i menys sovint en substitució de però inicial, sense que això ens autoritzi, naturalment, a establir una diferència de significacions entre ambdues formes. Equivalents però i emperò, la conservació d’ambdues formes no seria de cap utilitat, i així ho han reconegut els escriptors moderns decidint-se encertadament a favor de l’ús exclusiu de però.

In Old Catalan, there is, finally, the concurrent form emperò, that appears very often in [Cancelleria’s] documents substituting intermediate però and less often substituting initial però, which does not allow us to establish a difference in meaning between the two forms. Since però and emperò are equivalent, the preservation of both forms would be of no use, and so modern writers have recognized it, rightly deciding in favor of the exclusive use of però.

| (10) | La relació dels parlars catalans occidentals amb l’oest (és a dir, amb el centre lingüístic peninsular) és clara, i els esbossos insinuats d’arguments estructurals sobre vocalisme (que podrien desenrotllar-se qui-sap-lo) ho proven a bastament. No ens enganyem, emperò. (Badia i Margarit, Antoni Maria: La formació de la llengua catalana, 1981) |

| The relationship of Western Catalan dialects with the West (that is, with the peninsular linguistic center) is clear, as the insinuated sketches of structural arguments about vocalism (which could further unfold) clearly show. Let’s not fool ourselves, emperò (‘though’). |

| (11) | Ja a l’època visigòtica comencen d’apuntar certes modalitats lingüístiques regionals que havien de transcendir després als dialectes mossàrabs. Emperò sembla que tals particularitats no eren molt acusades dins els parlars dels romanics peninsulars, i que tampoc no diferien molt dels del Sud de la Gàl·lia. (Sanchis Guarner, Manuel: Gramàtica valenciana, 1950) |

| Already in the Visigothic period, certain regional linguistic modalities began to emerge, which would later transcend into the Mozarabic dialects. Emperò (‘but’) it seems that such peculiarities were not very noticeable in the speeches of the peninsular Romances, and that they did not differ much from those of southern Gaul. | |

| (12) | De cinc en amunt els partitius són idèntics als ordinals; emperò en lloc de desè, centè i milè, s’usen les formes dècim, centèsim i mil·lèsim amb preferència. (Sanchis Guarner, Manuel: Gramàtica valenciana, 1950) |

| From five on, partitives are identical to ordinals; emperò (‘but’) instead of desè, centè and milè the forms dècim, centèsim and mil·lèsim are preferred. |

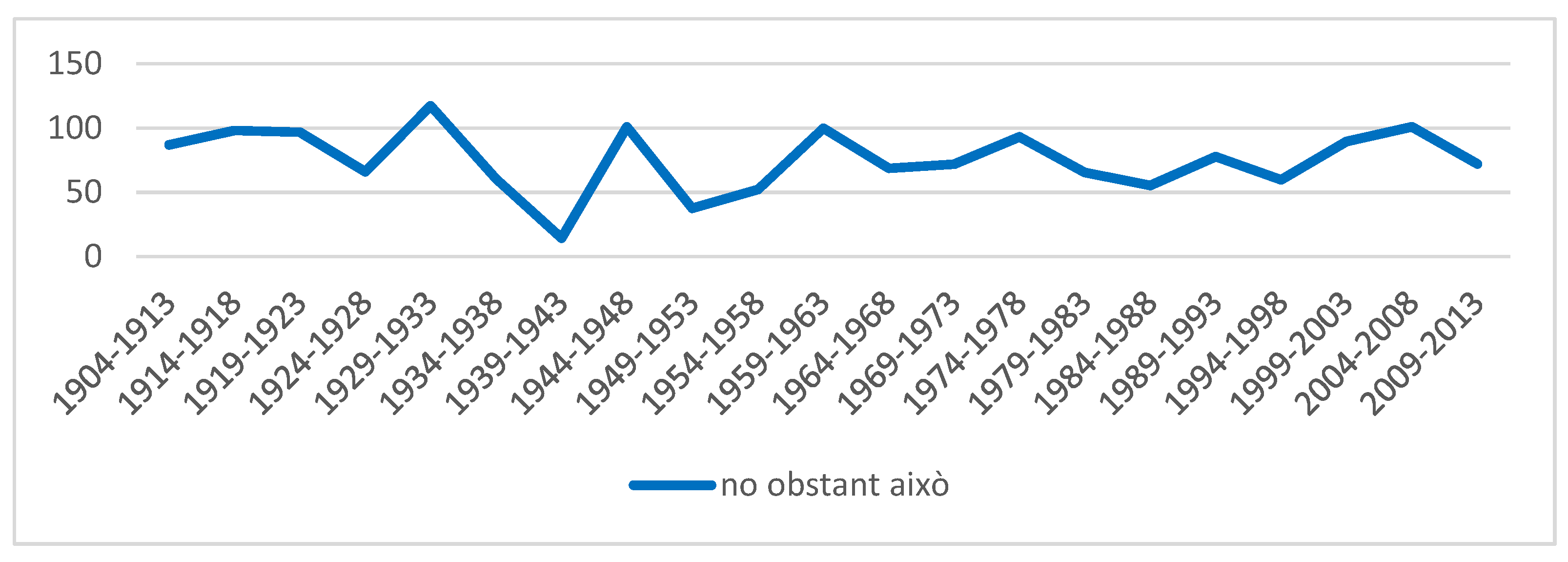

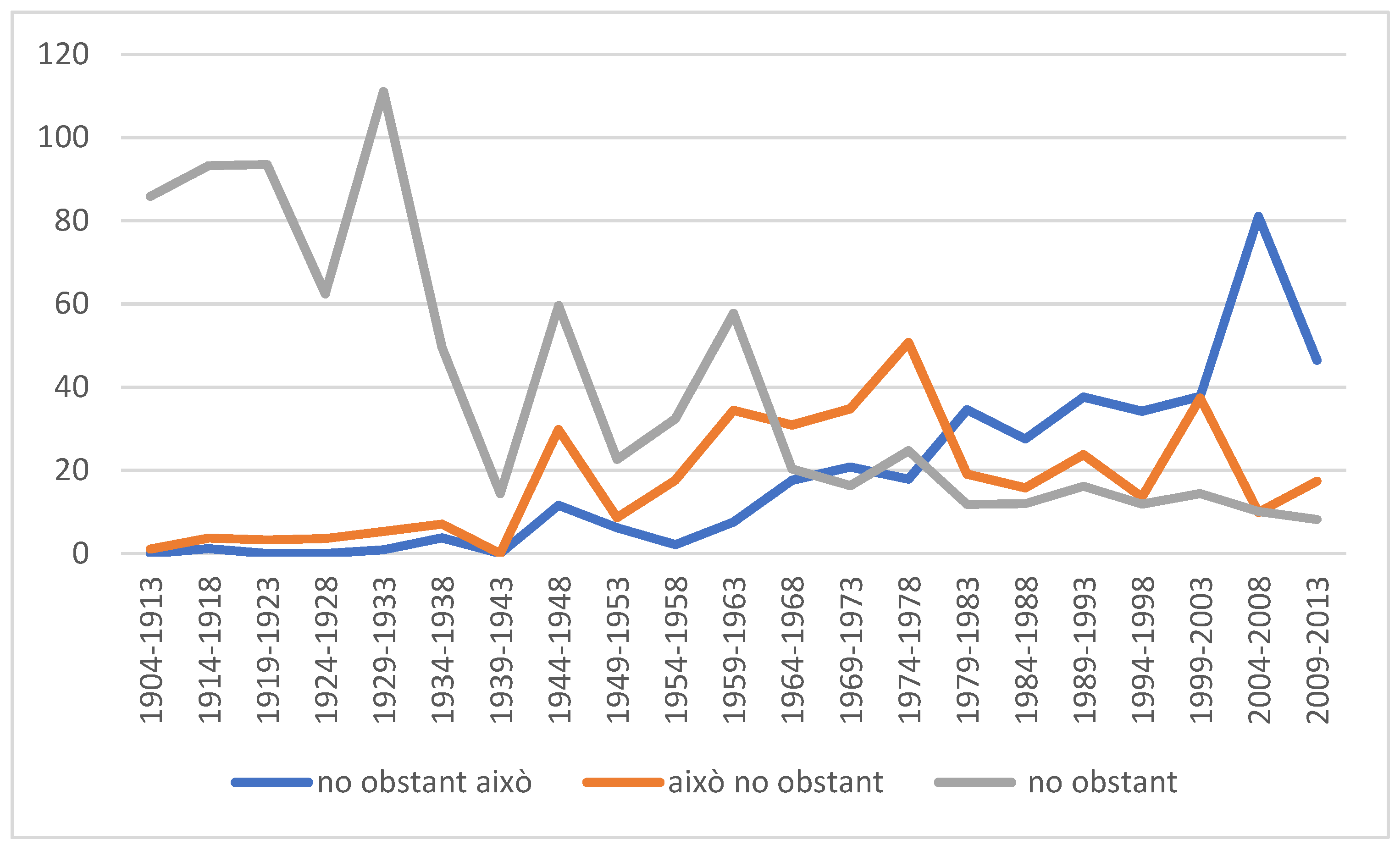

4.4. The Deictic Anchoring of No obstant (això)

| (13) | Potser hauria sentit una gran pena. I, no obstant, havia d’ésser així. (Puig i Ferreter, Joan: Camins de França, 1934) |

| Maybe he would have felt a great pity. And, no obstant (‘yet’), it had to be that way. | |

| (14) | Plaute i Molière feien "comèdies", vol dir-se, caricatures: això no obstant, els seus retrats de l’avariciós no són inexactes (Joan: Diccionari per a ociosos, 1964) |

| Plautus and Molière made "comedies", that is, caricatures: això no obstant (‘however’), their portraits of the greedy are not inaccurate. | |

| (15) | Momentàniament, existia un cert equilibri […]. La situació, no obstant això, s’hauria de malaguanyar inevitablement, així que els condicionaments que la feien possible esclatessin d’una manera o de l’altra. (Melià i Pericàs, Josep: Els mallorquins, 1967) |

| At the moment, there was a certain balance […]. The situation, no obstant això (‘however’), would inevitably have to be undermined, so that the conditions that made it possible would explode one way or another. |

| (16) | 2 1 [LC] no obstant això [o això no obstant] loc. adv. Tanmateix. […]. |

| 2 2 [LC] no obstant loc. adv. Tanmateix. […] (DIEC, s.v. obstar) | |

| (17) | no obstant loc. adv. 1. Tanmateix1. […]. Var.: això no obstant, no obstant això. (DDLC) |

| (18) | No obstant: cast. no obstante. (a) conj. i prep. Malgrat, sense que sigui obstacle […].—(b) No obstant això, o simplement No obstant: malgrat això, amb tot i això. […]. (DCVB, s.v. obstant) |

En aquestes frases la subordinada fa de subjecte; i, no obstant, en algunes d’elles, pot ésser representada per ho.(Fabra 1956, p. 98)

In these sentences the subordinate clause is the subject; and, no obstant ‘nonetheless’, it can be represented by [the pronoun] ho.

Incorrecta ha de considerarse la conjunción no obstant [n. a.], que presenta hoy a veces un cuadro de usos parecido a los de las locuciones castellanas “no obstante” y “sin embargo”.(Badia 1962, II, p. 97, Fn 12)

The conjunction no obstant [non-acceptable] must be considered incorrect; nowadays it often exhibits a series of uses similar to the Spanish expressions “no obstante” and “sin embargo”.

(1) A vegades apareix *no obstant en comptes de les expressions adverbials o conjuntives N1 tanmateix, N1 nogensmenys, amb tot, així i tot. La locució, absolutament vàlida com a preposició […], no és acceptable en el camp conjuntiu i cal desterrar-la. (2) No cal dir que encara és menys tolerable el flagrant barbarisme *sin embargo, massa freqüent en el llenguatge parlat de molts.(Badia 1994, p. 315)

(1) We can sometimes find *no obstant instead of the adverbial or conjunctive expressions N1 tanmateix, N1 nogensmenys, amb tot, així i tot. The expression, which is totally valid as a preposition […], is not acceptable as a conjunction and must be avoided. (2) Needless to say that the clearly foreing expression *sin embargo, too frequent in many people’s speech, is even worse.

La reducció de la locució no obstant això a no obstant, encara que no està acceptada normativament, té cada vegada més un major grau d’acceptació social.(Lacreu 1990, p. 327, Fn 3)

The reduction of the expression no obstant això into no obstant, even if it is not normatively accepted yet, is gaining social acceptance.

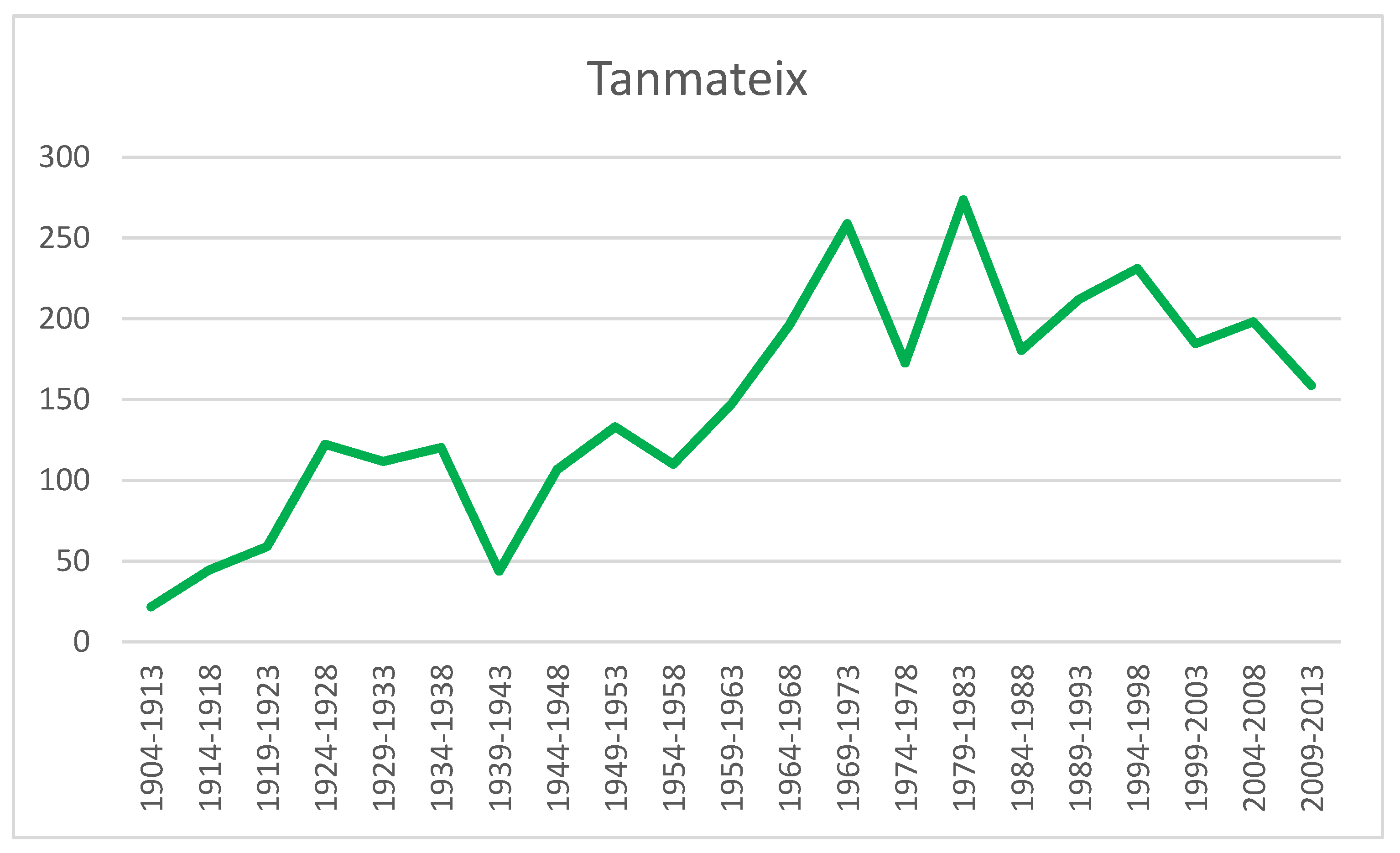

4.5. The Generalization of Tanmateix

| (19) | L’assimilació era natural en el nivell de la vida ordinària, però inconcebible en el pla literari. Tanmateix, l’assimilació cultural també compta amb exemples que mereixen d’ésser reportats. (Fuster, Joan: Nosaltres, els valencians, 1962) |

| Assimilation was natural at the level of ordinary life, but inconceivable at the literary level. Tanmateix (‘however’), there are also examples of cultural assimilation that deserve to be reported. | |

| (20) | Al Llibre dels fets de Jaume el Conqueridor apareix un cavaller Bernat de Rocafort, que ha estat identificat per Ferran Soldevila amb un majordom de la cúria reial del mateix nom que acompanyà el monarca a la campanya de Mallorca del 1228–1229. No hi ha, tanmateix, cap indici, fora de la coincidència del nom, que permeti relacionar aquest cortesà del segle xiii amb el nostre guerrer. (Marcos Hierro, Ernest: Almogàvers. La història, 2005) |

| In Llibre dels fets by James the Conqueror there is a knight named Bernat de Rocafort, who Ferran Soldevila identifies with a butler of the royal curia who accompanied the monarch in the campaign of Majorca in 1228–1229. There is, tanmateix (‘however’), no indication, apart from the coincidence of the name, that this 13th-century courtier can be related to our warrior. | |

| (21) | a. Eren uns carrers com qualssevol altres, i uns individus desconeguts. I tanmateix, us entreteníeu força mirant-los i admirant-los. (Fuster, Joan: Diccionari per a ociosos, 1964) |

| They were streets like any other, and unknown individuals. And tanmateix (‘yet’), you had a lot of fun watching and admiring them, | |

| b. Tenia la sensació que es liquidava un període oratjós i tenebrós de la meva vida, però, tanmateix, important. (Puig i Ferreter, Joan: Camins de França, 1934) | |

| I had the feeling that a stormy and gloomy period of my life was coming to an end, but tanmateix (‘yet’) it was important. | |

| c. Hom no pot negar que som, tanmateix, molt ignorants sobre l’abast total dels diversos canvis climàtics […] (Albertí i Gubern, Santiago; Albertí, Constança: L’origen de les espècies, 1982) | |

| There is no denying that we are, tanmateix (‘however’), very ignorant about the full extent of the various climate changes […] |

| (22) | tanmateixadv. ∥ 1. adv. Realment, de veres; cast. realmente, de verdad. […] ∥ 2. adv. Serveix per a fer l’afirmació d’un fet expressant ensems una limitació de tal fet o l’existència de certes dificultats que s’oposaven a la seva realització; cast. desde luego […]. ∥ 3. adv. De totes maneres; cast. de todos modos […]. (DCVB) |

| (23) | tanmateix adv. Expressa que una cosa és lògic que ocorri, esp. malgrat allò que semblava oposar-s’hi. […] | adv. Expressa que una cosa ha d’ésser perquè en resulti explicable una altra. […] ∥ adv. Nogensmenys. (DIEC) |

Casi imposible resulta dar una versión univalente de partícula tan matizada como tanmateix: expresa que es natural que suceda una cosa, en especial a pesar de aquello que parecía oponerse; que algo ha de realizarse para que de ello pueda darse razón de otra cosa; que lo que se acaba de decir no es obstáculo para algo.(Badia 1962, II, p. 97, Fn 11)

It is almost impossible to give a univalent version of a particle as nuanced as this one: it expresses that it is natural for something to happen, especially in spite of what seemed to oppose it; that something must occur to justify something else; that what has just been said is not an obstacle to something.

…Al llarg del segle xx, l’ensenyament, la lectura i els mitjans de comunicació deuen haver estat les vies a través de les quals el tanmateix [adversativoconcessiu] ha arribat a estendre’s, fins i tot, en registres orals mitjanament formals.

…Throughout the 20th century, teaching, printed material and the media must have been the ways through which tanmateix with an [adversative-concessive] meaning has come to extend, even in medium formality oral registers.

Potser aquesta tria per tanmateix amb valor [adversativoconcessiu] tingué a veure amb la preocupació de Pompeu Fabra per suplir, entre d’altres, el castellanisme sin embargo

The selection of tanmateix with an [adversative-concessive] meaning probably had to do with Pompeu Fabra’s concern to substitute, among others, the Spanish expression sin embargo.

Tot i difondre’s inicialment en l’àmbit d’ús formal, tanmateix constitueix un altre exemple d’una proposta, en aquest cas molt reeixida, de promoció d’un valor d’un element lingüístic en el moment de construcció de la norma fabriana.

Although initially disseminated in formal use contexts, tanmateix is another example of a proposal, in this case very successful, to promote the value of a linguistic item at the time of construction of Fabrian norm.

5. Conclusions

- (a)

- The neologism nogensmenys occurs 3 times in Fabra’s works included in the corpus, 35 times in Badia’s works, and 8 times in Sanchis’ grammar. Only Badia seems to make an extensive—very extensive, in fact—use of this connective.

- (b)

- Even though emperò was considered unadvisable since 1918, Badia uses emperò in 34 cases in the CTILC, 30 of which are in 4 different books (published in 1976, 1979, and 1981), always as a parenthetical connective. Sanchis (1950/1993, p. 285) also adheres to Fabra’s preference for però, but uses emperò 57 times in his grammar, thus contradicting the explicit norm therein.

- (c)

- The questioned variant no obstant is used by Fabra in grammars and also in letters he wrote. Badia and Sanchis only use no obstant això (32 and 2 cases, respectively), which is consistent with their explicit norm.

- (d)

- Tanmateix is not problematic. Its frequency is variable (Fabra: 7 examples, Badia: 34 examples, Sanchis: 51 examples) not linked to any explicit norm.

The pressure of Spanish on the different areas of use has caused a certain purist attitude among some of the codification agents and institutions, although language users have protested against this on various occasions throughout history.

Concebre la codificació de la llengua catalana moderna com el seu «redreçament» i aquest com, en bona mesura, la seva «descastellanització» era alhora l’expressió d’una ideologia lingüística i d’una línia programàtica d’actuació.

To conceive the codification of modern Catalan as its "straightening" and this as its "de-castilianization" was, to a large extent, both the expression of a linguistic ideology and a programmatic line of action.

De manera que Fabra construïa un artefacte que havia de vehicular l’anonimat en l’àmbit territorial i social en què s’havia de difondre, en competència amb l’anonimat de què ja gaudia l’espanyol a les terres de llengua catalana hispàniques. Aquest era un objectiu polític a assolir. Així ho demanava la creació de la consciència lingüística nacional dels catalans i la plena funcionalitat del català com a llengua pariona de l’espanyol, del francès o de l’italià.

So Fabra was building an artifact intended to implement anonymity in the territorial and social space in which it was to be spread, competing with the anonymity that Spanish already enjoyed in the Catalan-speaking territories in Spain. This was a political goal to be achieved. And this was needed in order to create the national linguistic consciousness of Catalan people and the full functionality of Catalan as a language which is equal to Spanish, French or Italian.

- (a)

- Changes in use cannot always be accounted for by resorting (only) to internal factors. External factors can trigger or have an influence on linguistic change.

- (b)

- The analysis of an item must take into consideration its paradigmatic relationships.

- (c)

- A complete analysis of the origin and evolution of prescriptive rules and their translation in use can only be based on comparing the information from different sources (at least, dictionaries, grammars, and corpus examples). The (explicit) norm and the current use should be confronted in order to uncover potential contradictions and inconsistencies.

- (d)

- The codification of formal use is a complex process in which ideology plays an important role.

- (e)

- In a language contact situation, (socio)linguistic analysis cannot be limited to one of the languages, especially when dealing with a minoritized language.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

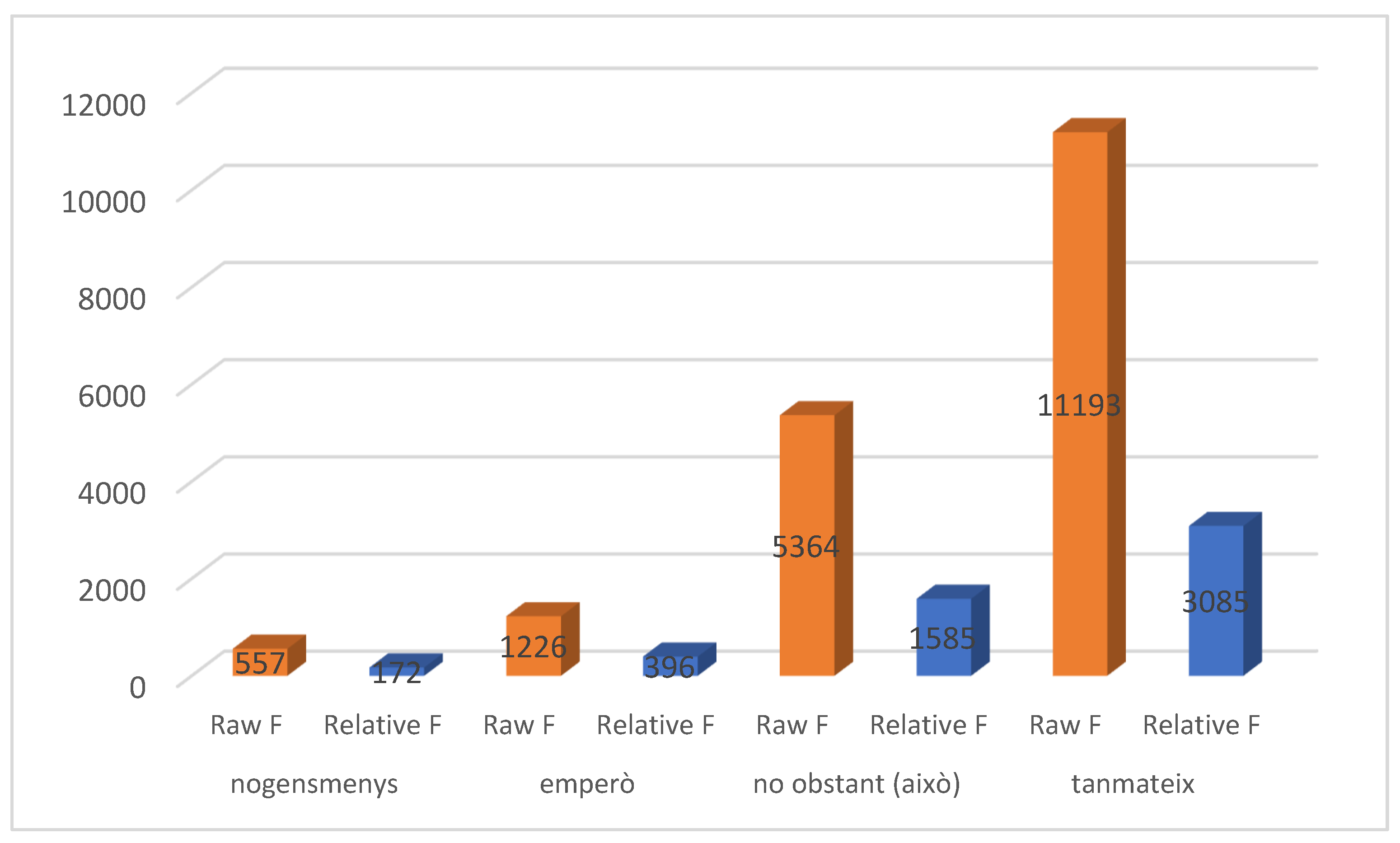

| Period | Words | Nogensmenys | Emperò | No Obstant (Això)/ Això No Obstant | Tanmateix | ||||

| N | N pmw | N | N pmw | N | N pmw | N | N pmw | ||

| 1904–1913 | 2,856,132 | 0 | 0.0 | 119 | 41.7 | 248 | 86.8 | 62 | 21.7 |

| 1914–1918 | 2,457,502 | 3 | 1.2 | 161 | 65.5 | 241 | 98.1 | 109 | 44.4 |

| 1919–1923 | 2,695,417 | 19 | 7.0 | 90 | 33.4 | 261 | 96.8 | 159 | 59.0 |

| 1924–1928 | 2,758,061 | 28 | 10.2 | 42 | 15.2 | 182 | 66.0 | 337 | 122.2 |

| 1929–1933 | 3,188,862 | 39 | 12.2 | 30 | 9.4 | 374 | 117.3 | 356 | 111.6 |

| 1934–1938 | 3,658,458 | 9 | 2.5 | 28 | 7.7 | 221 | 60.4 | 440 | 120.3 |

| 1939–1943 | 1,668,717 | 8 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 14.4 | 73 | 43.7 |

| 1944–1948 | 1,811,005 | 13 | 7.2 | 19 | 10.5 | 183 | 101.0 | 193 | 106.6 |

| 1949–1953 | 2,081,115 | 14 | 6.7 | 84 | 40.4 | 78 | 37.5 | 277 | 133.1 |

| 1954–1958 | 2,838,615 | 8 | 2.8 | 14 | 4.9 | 148 | 52.1 | 312 | 109.9 |

| 1959–1963 | 2,355,305 | 11 | 4.7 | 42 | 17.8 | 235 | 99.8 | 346 | 146.9 |

| 1964–1968 | 3,012,098 | 54 | 17.9 | 56 | 18.6 | 207 | 68.7 | 590 | 195.9 |

| 1969–1973 | 3,076,261 | 51 | 16.6 | 60 | 19.5 | 221 | 71.8 | 796 | 258.8 |

| 1974–1978 | 3,078,936 | 53 | 17.2 | 19 | 6.2 | 287 | 93.2 | 531 | 172.5 |

| 1979–1983 | 3,819,895 | 93 | 24.3 | 90 | 23.6 | 250 | 65.4 | 1045 | 273.6 |

| 1984–1988 | 3,236,522 | 27 | 8.3 | 72 | 22.2 | 179 | 55.3 | 584 | 180.4 |

| 1989–1993 | 5,046,720 | 36 | 7.1 | 93 | 18.4 | 392 | 77.7 | 1070 | 212.0 |

| 1994–1998 | 5,057,383 | 51 | 10.1 | 47 | 9.3 | 302 | 59.7 | 1169 | 231.1 |

| 1999–2003 | 5,055,566 | 14 | 2.8 | 41 | 8.1 | 453 | 89.6 | 933 | 184.5 |

| 2004–2008 | 5,037,948 | 15 | 3.0 | 108 | 21.4 | 509 | 101.0 | 998 | 198.1 |

| 2009–2013 | 5,123,913 | 11 | 2.1 | 11 | 2.1 | 369 | 72.0 | 813 | 158.7 |

| Total | 69,914,431 | 557 | 172 | 1226 | 396 | 5364 | 1585 | 11,193 | 3085 |

| 1 | The complete paradigm of contrastive parenthetical connectives is included in Cuenca (2002, § 31.2.3.3 and 2006, § 5.3.3). It is also included in a revised version in the new Catalan reference grammars: GIEC (§ 25.3.3), GEIEC (§ 21.3.1), GBU (§ 25.2). |

| 2 | The word però has two different uses in Catalan: as a conjunction, equivalent to ‘but’, and as a parenthetical connective, equivalent to ‘however’. Position and prosody differentiate these two uses: però is sentence initial when used as a conjunction and it is sentence medial or final and appositional when used as a parenthetical connective. Also, emperò, a reinforced variant of però, exhibits these two uses (see Section 4.3). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | Giacalone Ramat and Mauri (2012) also point to external factors as important in the evolution of contrastive connectives derived from Latin tota via, dum interim, per tantum and per hoc in French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | The grammaticalization hypothesis was the one Garachana developed for the parallel form in Spanish (Garachana 2014). |

| 8 | For an account of this process in Spanish, see Pérez Saldanya and Salvador (2014, pp. 3798–801). |

| 9 | Institut d’Estudis Catalans is the Catalan academy of humanities and sciences (www.iec.cat access on 7 January 2021). Among its functions, the most relevant is that of being the authority in all matters related to Catalan. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | See Appendix A for a detailed account of the evolution of connectives. The table included in Appendix A allows to observe and compare the evolution in the raw and relative frequency of each marker in the periods between 1904 and 2013. |

| 12 | The quotations corresponding to dictionaries will not be translated through a following gloss. The relevant parts will be quoted, translated, and explained in the following text. The examples in dictionaries have been deleted (marked as […]) to improve readability. Since they are all online dictionaries, the complete entries can easily be retrieved if necessary. |

| 13 | In his work, Fabra uses nogensmenys, often preceded by i ‘and’, in 3 cases, and he lists the form as an adversative connective adverb in all his grammars. |

| 14 | Badia exhibits the higher score of all authors as for frequency of use (35 cases). |

| 15 | In the period 2014–2018, there are only three occurrences, belonging to one book, which includes other old-fashioned markers, namely the causal car. |

| 16 | In 1950 all the cases (57) belong to the Gramàtica valenciana by Sanchis Guarner (most of the 84 cases in the period 1949–1953). Of the 90 cases for the period 1979–1963, 25 correspond to the translation o Darwin’s On the origin of species (L’origen de les espècies by Santiago Albertí i Gubern and Constança Albertí, 1982). In 2008 there were 108 cases, all but one from the book Acrollam by Biel Mesquida. In fact, Mesquida is the author who most frequently uses emperò (146 cases). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | Normalization per million words according to analyzable words for each period. |

References

Corpus

CTILC = IEC: Corpus Textual Informatitzat de la Llengua Catalana, Barcelona, IEC, 1985. Available online: https://ctilc.iec.cat/scripts/index.asp (accessed on 15 September 2021).Dictionaries

DCVB = Alcover, Antoni M.; Moll, Francesc de B. Diccionari català-valencià-balear. Palma: Moll, 1930–1962. Available online: https://dcvb.iec.cat (accessed on 15 September 2021).DIEC = Diccionari de la llengua catalana. Barcelona: IEC, 1995, 2nd edition 2007. Available online: https://dlc.iec.cat/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).DDLC = Diccionari descriptiu de la llengua catalana, 1998–2016. Barcelona: IEC. Available online: http://dcc.iec.cat/ddlcI/scripts/index.html?ini=hola (accessed on 15 September 2021).Grammars

Badia i Margarit, Antoni M. 1962. Gramática catalana. Madrid: Gredos.Badia i Margarit, Antoni M. 1994. Gramàtica de la llengua catalana. Descriptiva, normativa, diatòpica, diastràtica. Barcelona: Enciclopèdia Catalana.GBU = IEC. 2019. Gramàtica bàsica de la llengua catalana. Barcelona: IEC.GCC = Solà, Joan, Maria-Rosa Lloret, Joan Mascaró, and Manuel Pérez Saldanya, eds. 2002. Gramàtica del català contemporani. Barcelona: Empúries.GEIEC = IEC. 2018. Gramàtica Essencial de la Llengua Catalana. Barcelona: IEC. Available online: geiec.iec.cat (accessed on 15 September 2021).GIEC = IEC. 2016. Gramàtica de la llengua catalana. Barcelona: IEC.GUL = Cuenca, Maria Josep, and Manuel Pérez Saldanya. 2002. Guia d’usos lingüístics. València: Institut Interuniversitari de Filologia Valenciana.Fabra, Pompeyo. 1912. Gramática de la lengua catalana. Facsimile of the 1912 edition. Barcelona: Edicions Aqua, 1982.Fabra, Pompeu. 1918/1933. Gramàtica catalana. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans.Fabra, Pompeu. 1956. Gramàtica catalana. Barcelona: Teide.Lacreu, Josep. 1990. Manual d’ús de d’estàndard oral. València: Publicacions de la Universitat de València.Sanchis Guarner, Manuel. 1950. Gramàtica valenciana. València: Torre. [New edition by Antoni Ferrando. València. Altafulla, 1993].General References

- Amato, Roberta, Lucas Lacasa, Albert Díaz-Guilera, and Andrea Baronchelli. 2018. The dynamics of norm change in the cultural evolution of Language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115: 8260–65. Available online: www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1721059115 (accessed on 7 July 2021). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Argenter, Joan. 2020. Ideologies lingüístiques en context i conseqüències normatives. In Simposi Pompeu Fabra. Barcelona: IEC, pp. 112–22. [Google Scholar]

- Arguedas, Estellés Maria, and Maria Josep Cuenca. 2017. Ans y antes: De la anterioridad a la refutación en catalán y en español. Zeitschrift für Katalanistik 30: 165–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brumme, Jenny. 2020. Normative grammars. In Manual of Standardization in the Romance Languages. Edited by Franz Lebsanft and Frank Tacke. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Carreras, Joan, ed. 2009. The Architect of Modern Catalan: Selected Writings/Pompeu Fabra (1868–1948). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, Maria Josep. 1992–1993. Sobre l’evolució dels nexes conjuntius en català. Llengua i Literatura 5: 171–213. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, Maria Josep. 2002. Els connectors textuals i les interjeccions. In Gramàtica del català contemporani. Edited by Joan Solà, Maria-Rosa Lloret, Joan Mascaró and Manuel Pérez Saldanya. Barcelona: Empúries, vol. 3, pp. 3173–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, Maria Josep. 2006. La connexió i els connectors. Perspectiva oracional i textual. Vic: Eumo. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, Maria Josep. 2013. The fuzzy boundaries between discourse marking and modal marking. In Discourse Markers and Modal Particles. Categorization and Description. Edited by Degand Liesbeth, Bert Cornillie and Paola Pietrandrea. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, Maria Josep, Sorina Postolea, and Jacqueline Visconti. 2019. Contrastive markers in contrast. Discours: Revue de linguistique psycholinguistique et informatique 25: 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Espinal, M. Teresa. 2002. La negació. In Gramàtica del català contemporani. Edited by Soan Jolà, Maria-Rosa Lloret, Joan Mascaró and Manuel Pérez Saldanya. Barcelona: Empúries, vol. 3, pp. 687–2757. [Google Scholar]

- Fabra, Pompeu. 1926. La coordinació i la subordinació en els documents de la cancilleria catalana durant el segle XIVè. Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar. 2014. Gramática e historia textual en la evolución de los marcadores discursivos. Rilce 30: 959–84. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar. 2019a. Els connectors i la connexió. Gramàtica del català antic, Edited by Josep Martines and Manuel Pérez Saldanya. chp. 38, in print. [Google Scholar]

- Garachana, Mar. 2019b. Més enllà de la gramaticalització. El desenvolupament del marcador discursiu no obstant això en català. Caplletra 66: 137–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heine, Bernd. 2013. On discourse markers: Grammaticalization, pragmaticalization, or something else? Linguistics 51: 1205–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC—Institut d’Estudis Catalans. 2020. Simposi Pompeu Fabra. Barcelona: IEC. [Google Scholar]

- Lenepveu, Véronique. 2007. Toutefois et néanmoins, une synonymie partielle. Syntaxe et Sémantique 8: 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí i Castell, Joan. 2020. La ideologia lingüística de Pompeu Fabra aplicada a la concepció i a la confecció de la normativa. In Simposi Pompeu Fabra. Barcelona: IEC, pp. 102–9. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Caterina. 2017. El marcador discursiu noresmenys en català antic. Zeitschrift für Katalanistik 30: 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Caterina. 2018. La Gramaticalització dels Connectors Contraargumentatius en Català Modern. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat d’Alacant, Alacant, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Caterina. 2019. Origen i evolució dels connectors de contrast en català. València: IIFV, Barcelona: PAM. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Caterina. 2020. Origin and evolution of a pragmatic marker in Catalan: The case of tanmateix. Catalan Journal of Linguistics, 161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, Caterina. 2008. Coordination Relations in the Languages of Europe and Beyond. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, Jordi, and Joan Solà, eds. 2011. Obres Completes/Pompeu Fabra. Barcelona, València and Palma: ECSA, Edicions 62; Edicions 3i4; Moll. Volume 7. Available online: https://ocpf.iec.cat/ocpf.cgi (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Pérez Saldanya, Manuel, and Vicent Salvador. 2014. Oraciones concesivas. In Sintaxis histórica de la lengua española. Tercera parte. Edited by Concepción Company Company. México: FCE-UNAM, pp. 3697–839. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, Salvador. 2008. Gramaticalización por tradiciones discursivas: El caso de esto es. In Sintaxis histórica del español. Nuevas perspectivas desde las tradiciones discursivas. Edited by Johannes Kabatek. Madrid-Frankfurt: Vervuert/Iberoamericana, pp. 249–74. [Google Scholar]

- Rafanell, August. 2020a. The language reform, the Institut d’Estudis Catalans and the work of Pompeu Fabra. In Manual of Catalan Linguistics. Edited by Joan A. Argenter Giralt and Jens Lüdtke. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 517–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rafanell, August. 2020b. From Pompeu Fabra to the present day: Language change, hindrance to corpus and status planning. In Manual of Catalan Linguistics. Edited by Joan A. Argenter Giralt and Jens Lüdtke. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 545–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ramat, Anna Giacalone, and Caterina Mauri. 2012. Gradualness and pace in grammaticalization: The case of adversative connectives. Folia Linguistica 46: 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, Enric, and Manuel Prunyonosa. 2002. La coordinació. In Gramàtica del català contemporani. Edited by Joan Solà, Maria-Rosa Lloret, Joan Mascaró and Manuel Pérez Saldanya. Barcelona: Empúries, vol. 3, pp. 2181–245. [Google Scholar]

- Serradilla Castaño, Ana. 2009. Empero: La historia de una palabra en continuo movimiento. In Fronteras de un diccionario: Las palabras en movimiento. Edited by Elena de Miguel Aparicio. San Millán de la Cogolla: Cilenguas, pp. 295–326. [Google Scholar]

- Strubell, Miquel. 2011. The Catalan Language. In A Companion to Catalan Culture. Edited by Dominic Keown. London: Tamesis, pp. 117–42. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs, and Richard B. Dasher. 2002. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woolard, Kathryn A. 2016. Singular and Plural: Ideologies of Linguistic Authority in 21st Century Catalonia. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Catalan | Spanish | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| emperò | empero | ‘but/however’ |

| tanmateix | -- | ‘however’ |

| -- | sin embargo | ‘however’ |

| en canvi | en cambio | ‘instead’ |

|

al contrari per contra | al contrario por contra, por el contrario | ‘on the contrary’ |

| ara (bé) | ahora (bien) | ‘but’ (emphatic) |

|

però (non-initial) per (ai)xò | -- | ‘though’ |

| no obstant (això)/ això no obstant | no obstante | ‘notwithstanding’ |

| nogensmenys | -- | ‘nonetheless’ |

|

(tot) amb tot malgrat tot | con todo (y con eso) a pesar de/pese a todo | ‘all in all’ ‘notwithstanding’ |

|

(amb) tot i (amb) això tot i així/així i tot | aun así | ‘even so/still’ |

| de tota manera/de totes maneres | de todas maneras/formas de todos modos de cualquier manera | ‘anyway’ |

| en tot cas/en qualsevol cas | en todo/cualquier caso | ‘in any case’ |

| sigui com sigui/vulgui | sea como sea/fuere | ‘no matter what’ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuenca, M.-J. Language Norm and Usage Change in Catalan Discourse Markers: The Case of Contrastive Connectives. Languages 2022, 7, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010066

Cuenca M-J. Language Norm and Usage Change in Catalan Discourse Markers: The Case of Contrastive Connectives. Languages. 2022; 7(1):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010066

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuenca, Maria-Josep. 2022. "Language Norm and Usage Change in Catalan Discourse Markers: The Case of Contrastive Connectives" Languages 7, no. 1: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010066

APA StyleCuenca, M.-J. (2022). Language Norm and Usage Change in Catalan Discourse Markers: The Case of Contrastive Connectives. Languages, 7(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010066