Multimodal Resolution of Overlapping Talk in Video-Mediated L2 Instruction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Overlap Resolution in Video-Mediated Interaction

3. Video-Mediated L2 Learning

Tutoring as an Instructional Activity

4. Context and Methods

5. Results: The Multimodal Design of Simultaneous Start-Up Resolutions

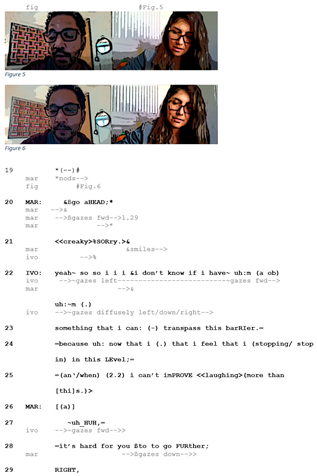

5.1. The Lip Pressing Gesture

5.2. The Go Ahead Utterance

5.3. The Combination of the Lip Pressing Gesture and Go Ahead Utterance

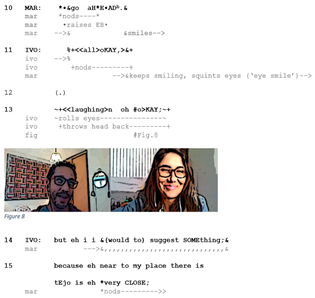

5.4. A Contrasting Case: The Resolution of Overlap without the Enhanced Explicitness Strategy

6. Discussion and Implications: Overlap Resolution and the Management of Language Use/Learning Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Transcription Conventions

| Verbal transcription according to GAT 2 (Couper-Kuhlen and Barth-Weingarten 2011) | |

| SYLlable | focus accent |

| sYllable | secondary accent |

| ? | rising to high |

| , | rising to mid |

| – | level |

| ; | falling to mid |

| . | falling to low |

| : | lengthening, by about 0.2–0.5 s |

| :: | lengthening, by about 0.5–0.8 s |

| ::: | lengthening, by about 0.8–1.0 s |

| °h | inbreath of appr. 0.2–0.5 s duration |

| (.) | micro pause, estimated, up to 0.2 s duration appr. |

| (-) | short estimated pause of appr. 0.2–0.5 s duration |

| (--) | intermediary estimated pause of appr. 0.5–0.8 s duration |

| (---) | longer estimated pause of appr. 0.8–1.0 s duration |

| (0.5)/(2.0) | measured pause of appr. 0.5/2.0 s duration (to tenth of a second) |

| [ ] | overlap and simultaneous talk |

| [ ] | |

| = | fast, immediate continuation with a new turn or segment (latching) |

| and_uh | cliticizations within units |

| <<laughing> > | laughter particles accompanying speech with indication of scope |

| ((cough)) | non-verbal vocal actions and events |

| ( ) | unintelligible passage |

| (may i) | assumed wording |

| (may i say/let us say) | possible alternatives |

| <<creaky> > | glottalized |

| <<h> > | higher pitch register |

| <<all> > | allegro, fast |

| ’SO | rising accent pitch movement |

| Multimodal transcription adapted from Mondada (2019) | |

| * * | Descriptions of embodied actions are delimited between two identical symbols that are synchronized with correspondent stretches of talk or time indications. |

| *---> | The action described continues across subsequent lines |

| ---->* | until the same symbol is reached. |

| ---->l.1 | The end of the described action is located several lines after its beginning. It is indicated with the corresponding line number after the first arrow. |

| >> | The action described begins before the excerpt’s beginning. |

| --->> | The action described continues after the excerpt’s end. |

| ..... | Action’s preparation. |

| ---- | Action’s apex is reached and maintained. |

| ,,,,, | Action’s retraction. |

| fig | The exact moment at which a screen shot has been taken |

| # | is indicated with a sign (#) showing its position within the turn/a time measure. |

| Multimodal transcription symbols: | |

| $ | Mari’s hand movements |

| § | Ivo’s hand movements |

| + | Ivo’s nodding |

| ▲ | Mari’s head direction |

| * | Mari’s nodding |

| ß | Mari’s eye gaze |

| • | Mari’s eyebrows |

| ~ | Ivo’s eyebrow movements and gaze |

| & | Mari’s mouth, lips movements and smile |

| % | Ivo’s mouth movements |

| @ | Mari’s chin |

| ∆ | Ivo’s torso movements |

| |name: | Indication of video problems due to connection difficulties stating the name of the person whose video is concerned. |

| Multimodal transcription abbreviations | |

| EB | eyebrows |

| RE | right eye |

| RH | right hand |

| fwd | forward |

| twd | toward |

| scr | screen |

| 1 | A complete list of the transcription conventions is found in the Appendix A. |

References

- Arminen, Ilkka, Christian Licoppe, and Anna Spagnolli. 2016. Respecifying mediated interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction 49: 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaman, Ufuk. 2018. Task-induced development of hinting behaviors in online task-oriented L2 interaction. Language Learning & Technology 22: 95–115. [Google Scholar]

- Balaman, Ufuk. 2019. Sequential organization of hinting in online task-oriented L2 interaction. Text & Talk 39: 511–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaman, Ufuk, and Simona Pekarek Doehler. 2022. Navigating the complex social ecology of screen-based activity in video-mediated interaction. Pragmatics 32: 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhiah, Hassan. 2009. Tutoring as an embodied activity: How speech, gaze and body orientation are coordinated to conduct ESL tutorial business. Journal of Pragmatics 41: 829–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhiah, Hassan. 2013. Gesture as a resource for intersubjectivity in second-language learning situations. Classroom Discourse 4: 111–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, Julie E., Pedro Fonseca, Ilana Mermelstein, and Myles Williamson. 2021. Zoom disrupts the rhythm of conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, Helen Melander, and Johanna Svahn. 2020. Collaborative work on an online platform in video-mediated homework support. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 3: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino Avila, Marco Octavio. 2019. Exploring teachers’ and learners’ overlapped turns in the language classroom: Implications for classroom interactional competence. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 9: 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clayman, Steven E. 2012. Turn-Constructional Units and the Transition-Relevance Place. In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Edited by Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 150–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth. 2021. Language over time: Some old and new uses of OKAY in American English. Interactional Linguistics 1: 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth, and Dagmar Barth-Weingarten. 2011. A system for transcribing talk-in-interaction: GAT 2 for English. Gesprächsforschung—Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion 12: 1–51. Available online: http://www.gespraechsforschung-online.de/fileadmin/dateien/heft2011/px-gat2-englisch.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth, and Margret Selting. 2018. Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth, and Sandra A. Thompson. 2000. Concessive patterns in conversation. In Cause, Condition, Concession, Contrast: Cognitive and Discourse Perspectives. Edited by Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen and Bernd Kortmann. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creider, Sarah Chepkirui. 2020. Student talk as a resource: Integrating conflicting agendas in math tutoring sessions. Linguistics and Education 58: 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppermann, Arnulf, and Axel Schmidt. 2021. Micro-Sequential Coordination in Early Responses. Discourse Processes 58: 372–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppermann, Arnulf, Lorenza Mondada, and Simona Pekarek Doehler. 2021. Early Responses: An Introduction. Discourse Processes 58: 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFelice Box, Catherine. 2015. When and how students take the reins: Specifying learner initiatives in tutoring sessions with preschool-aged children. Applied Linguistics Review 6: 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehler, Simona Pekarek, and Ufuk Balaman. 2021. The Routinization of Grammar as a Social Action Format: A Longitudinal Study of Video-Mediated Interactions. Research on Language and Social Interaction 54: 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooly, Melinda, and Nuriya Davitova. 2018. What Can We Do to Talk More: Analysing Language Learners Online Interaction. Hacettepe University Journal of Education 33: 215–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekin, Semih, Ufuk Balaman, and Fatma Badem-Korkmaz. 2021. Tracking telecollaborative tasks through design, feedback, implementation, and reflection processes in pre-service language teacher education. Applied Linguistics Review, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskildsen, Søren Wind. 2020. From Constructions to Social Action: The Substance of English and Its Learning from an Interactional Usage-Based Perspective. In Ontologies of English, 1st ed. Edited by Christopher J. Hall and Rachel Wicaksono. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskildsen, Søren Wind, and Ali Reza Majlesi. 2018. Learnables and Teachables in Second Language Talk: Advancing a Social Reconceptualization of Central SLA Tenets. Introduction to the Special Issue. The Modern Language Journal 102: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, Peter, and John Local. 1983. Turn-competitive incomings. Journal of Pragmatics 7: 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgin, Ufuk, and Adam Brandt. 2020. Creating space for learning through ‘Mm hm’ in a L2 classroom: Implications for L2 classroom interactional competence. Classroom Discourse 11: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, Karen, Maxi Kupetz, and Hie-Jung You. 2019. ‘Embracing social interaction in the L2 classroom: Perspectives for language teacher education’—an introduction. Classroom Discourse 10: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Lloret, Marta. 2015. Conversation analysis in Computer-assisted Language Learning. CALICO Journal 32: 569–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Joan Kelly. 2020. L2 classroom interaction and its links to L2 learners’ developing L2 linguistic repertoires: A research agenda. Language Teaching, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Joan Kelly, and Stephen Daniel Looney. 2019. Introduction: The Embodied Work of Teaching. In The Embodied Work of Teaching. Edited by Joan Kelly Hall and Stephen Daniel Looney. Bristol: Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Joan Kelly, Tianfang Wang, and Su Yin Khor. 2020. The Links between the Linguistic Designs of L2 Teacher Questions and the Student Responses They Engender. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 8: 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M. Obaidul, Asaduzzaman Khan, and M. Monjurul Islam. 2018. The spread of private tutoring in English in developing societies: Exploring students’ perceptions. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 39: 868–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, Regine, and Ursula Stickler. 2012. The use of videoconferencing to support multimodal interaction in an online language classroom. ReCALL 24: 116–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Christian, and Paul Luff. 1993. Media Space and Communicative Asymmetries: Preliminary Observations of Video-Mediated Interaction. Human–Computer Interaction 7: 315–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, John. 2016. On the diversity of ‘changes of state’ and their indices. Journal of Pragmatics 104: 207–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoey, Elliott M., and Kobin Kendrick. 2017. Conversation Analysis. In Research Methods in Psycholinguistics and the Neurobiology of Language: A Practical Guide. Edited by Annette M. B. de Groot and Peter Hagoort. Hoboken and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 151–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ilomäki, Sakari, and Johanna Ruusuvuori. 2020. From appearings to disengagements: Openings and closings in video-mediated tele-homecare encounters. Social Interaction: Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 3: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakonen, Teppo, and Heidi Jauni. 2021. Mediated learning materials: Visibility checks in telepresence robot mediated classroom interaction. Classroom Discourse 12: 121–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, Gail. 1984. Notes on a systematic deployment of the acknowledgement tokens “Yeah”; and “Mm Hm”. Paper in Linguistics 17: 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, Gabriele. 2004. Participant Orientations in German Conversation-for-Learning. The Modern Language Journal 88: 551–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendon, Adam. 2004. Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, Daisuke, Taiane Malabarba, and Joan Kelly Hall. 2018. Data collection considerations for classroom interaction research: A conversation analytic perspective. Classroom Discourse 9: 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyland, Christopher. 2018. Resistance as a resource for achieving consensus: Adjusting advice following competency-based resistance in L2 writing tutorials at a British University. Classroom Discourse 9: 267–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licoppe, Christian, and Julien Morel. 2012. Video-in-Interaction: “Talking Heads” and the Multimodal Organization of Mobile and Skype Video Calls. Research on Language and Social Interaction 45: 399–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luff, Paul, Christian Heath, Hideaki Kuzuoka, Jon Hindmarsh, Keiichi Yamazaki, and Shinya Oyama. 2003. Fractured ecologies: Creating environments for collaboration. Human-Computer Interaction 18: 51–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malabarba, Taiane. 2015. O percurso do agir interacional no trabalho docente: Do projeto de ensino às participações contingentes em sala de aula de língua inglesa [The Interactional Trajectories of English-as-a-Foreign-Language Teaching: From the Instructional Project to Contingent Participations]. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, São Leopoldo, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2007. Multimodal resources for turn-taking: Pointing and the emergence of possible next speakers. Discourse Studies 9: 194–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2014. The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 65: 137–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2015. Ouverture et préouverture des réunions visiophoniques. Reseaux 194: 39–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondada, Lorenza. 2019. Conventions for Multimodal Transcription. Available online: https://www.lorenzamondada.net/multimodal-transcription (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Moorhouse, Benjamin Luke, Yanna Li, and Steve Walsh. 2021. E-classroom interactional competencies: Mediating and assisting language learning during synchronous online lessons. RELC Journal, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, Kristian. 2009. Establishing recipiency in pre-beginning position in the second language classroom. Discourse Processes 46: 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Hanh, Ann Tai Choe, and Cristiane Vicentini. 2022. Opportunities for second language learning in online search sequences during a computer-mediated tutoring session. Classroom Discourse, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbertz-Siitonen, Margarethe. 2015. Transmission delay in technology-mediated interaction at work. Psychology Journal 13: 203–34. Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/51325 (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Oloff, Florence. 2013. Embodied withdrawal after overlap resolution. Journal of Pragmatics 46: 139–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloff, Florence. 2019. Okay as a neutral acceptance token in German conversation. Lexique 25: 197–225. Available online: https://lexique.univ-lille.fr/data/images/numero-25/10_Oloff_ok%20pagin%C3%A9e_FINALE_20-12.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Park, Innhwa. 2017. Questioning as advice resistance: Writing tutorial interactions with L2 writers. Classroom Discourse 8: 253–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhleder, Karen, and Brigitte Jordan. 2001. Co-Constructing Non-Mutual Realities: Delay-Generated Trouble in Distributed Interaction. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 10: 113–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rusk, Fredrik, and Michaela Pörn. 2019. Delay in L2 interaction in video-mediated environments in the context of virtual tandem language learning. Linguistics and Education 50: 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, Harvey. 1992. Lectures on Conversation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50: 696–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1997. Whose text? Whose context? Discourse and Society 8: 165–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2000. Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society 29: 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2007. Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2010. Some Other “Uh(m)”s. Discourse Processes 47: 130–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Jan Georg. 2017. Medien als Verfahren der Zeichenprozessierung: Grundsätzliche Überlegungen zum Medienbegriff und ihre Relevanz für die Gesprächsforschung. Gesprächsforschung—Online-Zeitschrift Zur Verbalen Interaktion 18: 34–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sert, Olcay. 2017. Creating opportunities for L2 learning in a prediction activity. System 70: 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, Olcay. 2021. Transforming CA Findings into Future L2 Teaching Practices: Challenges and Prospects for Teacher Education. In Classroom-Based Conversation Analytic Research: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Pedagogy. Edited by Silvia Kunitz, Numa Markee and Olcay Sert. New York: Springer International Publishing AG, pp. 259–79. [Google Scholar]

- Seuren, Lucas M., Joseph Wherton, Trisha Greenhalgh, and Sara E. Shaw. 2021. Whose turn is it anyway? Latency and the organization of turn-taking in video-mediated interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 172: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanovic, Melisa. 2018. Social deontics: A nano-level approach to human power play. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior 48: 369–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennevig, Jan. 2000. Getting Acquainted in Conversation: A Study of Initial Interactions. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Uskokovic, Budimka, and Carmen Talehgani-Nikazm. 2022. Talk and Embodied Conduct in Word Searches in Video-Mediated Interactions. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Steve. 2006. Investigating Classroom Discourse. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Waring, Hansun Zhang. 2005. Peer tutoring in a graduate writing centre: Identity, expertise, and advice resisting. Applied Linguistics 26: 141–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, Hansun Zhang. 2011. Learner Initiatives and Learning Opportunities in the Language Classroom. Classroom Discourse 2: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waring, Hansun Zhang. 2016. Theorizing Pedagogical Interaction: Insights from Conversation Analysis. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wigham, Ciara R. 2017. A multimodal analysis of lexical explanation sequences in webconferencing-supported language teaching. Language Learning in Higher Education 7: 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malabarba, T.; Mendes, A.C.O.; de Souza, J. Multimodal Resolution of Overlapping Talk in Video-Mediated L2 Instruction. Languages 2022, 7, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020154

Malabarba T, Mendes ACO, de Souza J. Multimodal Resolution of Overlapping Talk in Video-Mediated L2 Instruction. Languages. 2022; 7(2):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020154

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalabarba, Taiane, Anna C. Oliveira Mendes, and Joseane de Souza. 2022. "Multimodal Resolution of Overlapping Talk in Video-Mediated L2 Instruction" Languages 7, no. 2: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020154

APA StyleMalabarba, T., Mendes, A. C. O., & de Souza, J. (2022). Multimodal Resolution of Overlapping Talk in Video-Mediated L2 Instruction. Languages, 7(2), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020154