Abstract

In contrast to views that treat positions and standpoints as defining the scope of argumentation, our normative pragmatic approach sees positions and standpoints as interactionally emergent products of argumentative work. Here, this is shown in a detailed case study of a question-answer session in which former US President Donald J. Trump was pressed by journalists to express and defend his standpoint on the Charlottesville protests by neo-Nazis and White nationalists. Trump repeatedly evaded efforts to pin down his standpoint; however, with each of his answers to the questions, his built-up position circumscribed the range of possible standpoints he could take. To the end, he avoided backing down from any prior statement expressing his standpoint, while also preserving a degree of maneuverability regarding what his standpoint amounted to.

1. Introduction

The possibility of disagreement is ubiquitous in human interaction, and its management is a constant concern. Elsewhere, we have described argumentation as a very abstract set of resources for managing disagreement, grounded in the pragmatics of communication and overlaid with situated norms of reasonableness (van Eemeren et al. 1993, p. 2; Jackson 2019; Jackson and Jacobs 1980; Jacobs 1999; Jacobs and Jackson 1989). Along with other communication scholars (e.g., Innocenti 2022; Kauffeld and Goodwin 2022; Weger and Aakhus 2005), we have embraced ‘normative pragmatics’ as a label for our approach. Though informed and influenced by other contemporary argumentation theories, normative pragmatics is distinctive in asserting that both the structure and the substance of argumentative discourse emerge from interaction, meaning that what participants in argumentation end up producing as positions and standpoints are collaborative productions.

‘Standpoint’ and ‘position’ are important but problematic theoretical terms. ‘Standpoint’ is often used interchangeably with claim or conclusion (usually the highest-order node in a complex case), and ‘position’ is a body of supporting arguments—a case—that justifies or undermines a standpoint. Argumentation that elaborates positions may proceed after standpoints have been formulated (for example, in formal policy debates). However, acknowledged standpoints are not a prerequisite to argumentation. Arguments occur without them. Even when put on the record, getting a standpoint clearly formulated can be an arduous task.

A more fundamental and general pattern in argumentative discourse is what Musi and Aakhus (2018) dubbed the target-callout sequence, where the callout problematizes something about another conversational act (the “arguable” in Jackson and Jacobs 1980). A targeted arguable can itself be a standpoint, something from which a standpoint could be derived, or something only very loosely connected with what might emerge as a standpoint (Jackson 1992). A position may be built up around a field of possible standpoints, without a commitment to any one in particular. In addition, the meaning of any standpoint that is expressed depends upon its location in its context of occurrence, much of which is discursive.

This study examines a high-profile case of standpoint emergence that allows us to display the precarity of notions such as standpoint and position. The case concerns former US President Donald J. Trump and his standpoint regarding events that took place in August 2017, after a White nationalist rally in Charlottesville ended in violence and death. Trump issued two statements in the days following this event and these, together with a hijacked press conference, remain objects of political controversy. We will trace the emergence of Trump’s putative standpoints through the two statements and his answers to hostile questioning during the press conference. The analytic question of this study echoes a Watergate-era meme: What was the President’s standpoint and when did he take it?1

This case is unusual, but not because it involves standpoint emergence. Standpoint emergence, even absence, is completely commonplace in ordinary language interaction and discourse. This case is unusual because it makes the work involved in standpoint emergence so evident. Here, standpoint emergence is the interactional achievement of reporters trying over and over to pin down the President’s standpoint, circumscribing what it possibly could be and inferring it from the position he builds. It has already been shown that in situations like this, questioned politicians may covertly resist questioning through various tactics of evasion (Clayman and Heritage 2002, chp. 7). They often look for an equivocal non-answer that still looks like an answer and that allows them to “leave the field” of the agenda set out by the question (Bull 2008; Jacobs 2016; Polcar and Jacobs 1997). We will see this pattern in many of Trump’s responses. In this case, journalists in their collective follow-ups “pursue a standpoint” in a way akin to how single interviewers can “pursue an answer” (Romaniuk 2013).

This case is also unusual because it reveals departures from the norms for interactional formatting in a presidential press conference. American presidential press conferences operate conventionally as a question-answer inquiry conducted in a “neutralistic” manner (Clayman 1988, 1992; Clayman and Heritage 2002). Reporters are not supposed to argue with the interviewee. Asking questions, introducing assertions as reports of other people’s views, and positioning assertions as prefaces to questions are all practices that work to avoid the appearance of arguing. Since the 1960s, the questioning of presidents has become markedly more aggressive and adversarial (Clayman et al. 2006; Heritage and Clayman 2013), coming to more closely resemble the thinly veiled argumentativeness of Prime Minister’s Question Time in the UK Parliament (Mohammed 2018). However, the question-answer format remains in force. Even in their notoriously confrontational news interview, Dan Rather and George H. W. Bush collaborated to maintain the question-answer structure (Schegloff 1988). Still, everyone knows that the questions in these cases are not simply information-seeking acts. Both sides calculate the argumentative consequences of their questions and answers. All parties orient to the possibilities for a would-be debate lurking in the background. The participants play, as it were, one kind of language game on the board of another. Question-answer becomes a “functional substitute” for open argumentation (van Eemeren et al. 1993, chp. 6; Jacobs 1989, 2002), a way to fashion and probe argumentative positions without openly disagreeing and debating. The case analyzed here is illuminating precisely because the pretense of a purely information-gathering activity could not be sustained as the journalists broke into open, direct, bald-on-record disagreement and counterargument.

2. Methods

The case materials were various records of discourse produced in early- to mid-August of 2017; the anchoring texts consisted of two statements issued by President Trump on 12 August and 14 August and a press conference held on 15 August. Working from these anchoring texts, we compiled other contextual data to position them within ongoing argumentative discourse in news and social media. The statements were brief comments on a White nationalist rally that occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia, on 11 and 12 August and were based on written scripts but delivered orally at events organized for other purposes. The press conference was called to introduce a new infrastructure initiative. The President’s prepared presentation was excluded when preparing a technical transcript of the question-answer period. Video recordings and vernacular transcripts were available from various news organizations (ABC News, Associated Press-New York Times, C-SPAN, CNN, FOX News, NBC News, POLITICO, and the White House). The technical transcript with video links (Jacobs et al. 2022) contained features and content omitted from journalistic transcriptions. Each recording allowed differential access to what was being said, especially during overlapped shouting by journalists reacting to Trump’s answers or bidding for the floor.

We examined the two statements and the press conference using the microanalytic methods typical of our earlier work (Jackson 1986; Jacobs 1986, 1988, 1990); however, we also drew on external discourse for further context. Political speech has taken on a complexity Mohammed (2019) termed “networked open-endedness”. Any individual utterance in modern political discourse both draws on and contributes to assumed broader discourses. We treated the two statements and the press conference as if they contained pointers to this mutually understood context. These anchor texts (especially the press conference) contained many references to prior events and phrases suggesting shared background knowledge; we used these as query strings for systematic searches of prior discourse. For the retrieval of news content, we used LexisNexis. For the retrieval of social media content, we used a bundle of natural language processing tools known as the Social Media Macroscope (Yun et al. 2020). The results from these queries were analyzed both quantitatively (e.g., content volume and topical themes) and qualitatively (e.g., argument reconstruction). In this way, we were able to work backwards in time to aid our analysis of the three anchor texts. Using the same methods, we were able to work forwards in time to check certain interpretations against uptake in subsequent discourse (analogously to the “next turn proof procedure” used in conversation analysis; see Sidnell 2013).

3. Results and Discussion

As a starting point for analysis, we treated President Trump’s two statements on Charlottesville as conveying his nominal standpoint. Both statements were glossed (Garfinkel and Sacks 1970) as condemnations of what happened in Charlottesville; however, both permitted multiple interpretations of exactly who or what he was condemning and even doubt about whether any condemnation was made at all.

3.1. The Two Statements on Charlottesville

The first statement was delivered from a written script late Saturday afternoon at an unrelated bill-signing ceremony. Video recordings captured a moment in which Trump appeared to go off-script (C-SPAN 2017; see Holan 2017 for full statement). The ad-libbed portion is underlined in the following excerpt:

But we’re closely following the terrible events unfolding in Charlottesville, Virginia. We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence on many sides, on many sides. It’s been going on for a long time in our country. Not Donald Trump, not Barack Obama, it’s been going on for a long, long time. It has no place in America. What is vital now is a swift restoration of law and order and the protection of innocent lives.

The “terrible events unfolding in Charlottesville” occurred during a rally instigated by Unite the Right (a movement embraced by ultra-right-wing organizations, including self-identified Nazis and White nationalists), nominally to protest the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee, the iconic general for the Confederate army during the American Civil War.2 The rally was planned for Saturday, 12 August, but the organizers called protestors to an impromptu Friday night march to the statue. In a surreal echo of 1930s newsreels, newscasts showed lines of protestors, clad in white sport shirts and khaki pants, carrying tiki torches and chanting racist slogans (e.g., “Jews will not replace us!”, “Blood and soil!”, “Into the ovens!”, “Blacks will not replace us!”, and “White lives matter!”). Counter-protestors gathered, and shouting back and forth led to fighting (mostly shoving and hitting). Injuries were reported on both sides.

Early Saturday morning, both sides reassembled and resumed hostilities. Before noon, the Governor of Virginia declared a state of emergency and law enforcement ordered the crowds to disperse. The violence seemed to have ended. However, around 1 p.m., a neo-Nazi protestor ploughed his car into a crowd of dispersing counter-protestors, causing multiple injuries and the death of Heather Heyer. Videos of the attack appeared almost immediately on television news and social media.

Trump’s statement was most plausibly motivated by the killing. His notice of the protest was minimal until Heather Heyer’s death. Despite being a prolific tweeter, Trump sent out nothing about Charlottesville prior to 12 August. As the violence escalated, Trump began tweeting; seven of his eight 12th August tweets referred directly or indirectly to Charlottesville (Brendan n.d.). Beginning around 1 p.m. he tweeted that “we must ALL be united” against hate, that Charlottesville was “sad,” that “swift restoration of law and order” was needed, that “we are watching developments,” and finally, hours after the killing, “condolences”. In the days surrounding the event, he tweeted nothing about racism and bigotry, nor anything condemning the protestors.

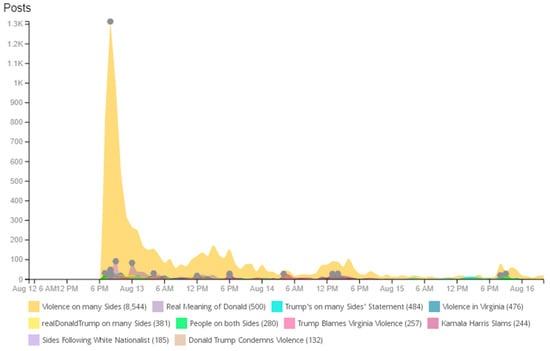

The ad-libbed “on many sides” phrase in the Saturday statement was widely interpreted as an interjection to avoid denouncing the protestors. For the next two days, Trump’s statement drew fierce criticism for blaming all sides and for failing to even name the right-wing hate groups who organized the rally and fostered the views of the killer. Queries on the phrase “on many sides” retrieved over 13,000 tweets (not including retweets). Substantively, the attention paid to “many sides” was negative. Figure 1 shows a burst of commentary soon after the statement along with a classification of the topical content. These “topic waves” reveal what significance tweeters found in the phrase “many sides”. The figure shows (roughly) what was being said on Twitter: not “Trump condemns racism,” but “Trump blames both sides”. The news coverage was similar, treating his focus on the violence as a way to include both sides in his condemnation and to avoid condemning racism. Over 2000 stories were retrieved from LexisNexis in the days just following the statement, and “many sides” often appeared in the headlines, attesting to the significance attached to this phrase.

Figure 1.

Topic waves following Trump’s Saturday statement. (Crimson Hexagon).

Others in Trump’s administration quickly named the killing an act of domestic terrorism, and many critics demanded that Trump do the same. Trump issued a stronger statement on Monday, August 14, again reading from a prepared script. This time, he named specific groups (passage underlined; see Rubin 2017 for the full statement):

As I said on Saturday, we condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of bigotry, hatred, and violence. It has no place in America. And as I have said many times before, no matter the color of our skin, we all live under the same laws; we all salute the same great flag; and we are all made by the same almighty God. We must love each other, show affection for each other, and unite together in condemnation of hatred, bigotry, and violence. We must discover the bonds of love and loyalty that bring us together as Americans. Racism is evil, and those who cause violence in its name are criminals and thugs, including the KKK, neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans. We are a nation founded on the truth that all of us are created equal. We are equal in the eyes of our creator, we are equal under the law, and we are equal under our constitution. Those who spread violence in the name of bigotry strike at the very core of America.

The inclusion of “other hate groups” in the list introduced an ambiguity that could not be explored by the press, since Trump took no questions; however, many people treated the statement as the kind of condemnation they were calling for.

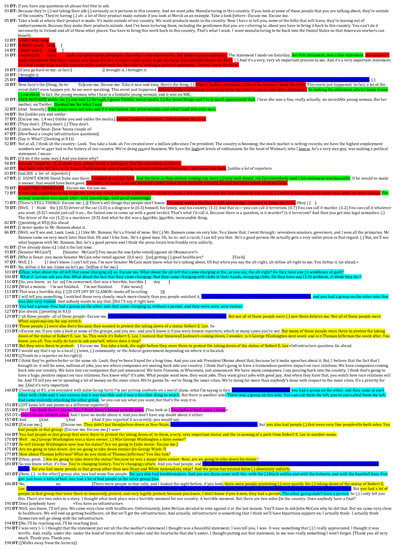

Tuesday morning, Trump invited strong suspicion that his Monday “racism is evil” statement was disingenuous, read only grudgingly because his staff insisted that he do so. He re-tweeted a cartoon image headed “FAKE NEWS CAN’T STOP THE TRUMP TRAIN,” depicting a train running over a person with the CNN logo for a head and torso as railroad ties fly to both sides of the track (Figure 2). The visual resemblance to the widely circulated video of the neo-Nazi car ploughing through flying counter-protestors was obvious, and although the tweet was deleted within minutes, it was captured and discussed on social media and in the mainstream press (e.g., Sullivan and Haberman 2017).

Figure 2.

Tuesday morning Trump train retweet.

Going into the press conference on 15 August, President Trump was on record as having condemned “in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence”. However, exactly what (and whose) egregious display he had condemned, and whether he had done so authentically, was very much in doubt. Whether and how his statements expressed his standpoint would depend on the position he developed subsequently and which parts of the statements he adhered to under questioning.

3.2. The Press Conference

The press conference was called by the President to announce a new infrastructure initiative, which he did while flanked by three Cabinet members. However, reporters largely ignored that agenda. After concluding his prepared remarks, Trump invited questions. From the very first reporter’s question, and throughout the session, Trump was called on to answer for his standpoint on Charlottesville. In response, Trump developed his position. In this section, we will show how reporters’ questions and challenges shaped the standpoint Trump wound up defending as he built up his position.

3.2.1. Overview of the Question-Answer Period

Figure 3 displays a visual overview of how Trump’s position developed over time. We preserved the proportionality and distribution of different themes by stripping out reporters’ turns. Under persistent questioning, Trump produced several lines of argument. We identified six, for which we have provided glosses. Going into the press conference, Trump was committed overtly to the first line (Nazis are bad, and I condemned them) and conjecturally to the fourth (the alt-left was also violent) and fifth (both sides are to blame), depending on whether the Monday statement counted as a withdrawal of the ad-lib comments on Saturday.

Figure 3.

Trump’s major lines of argument (color coded) distributed over time. Dark blue: Nazis are bad, and I condemned them. Green: My statements were good. Red: I had to wait for the facts to make a full statement. Light blue: The alt-left was also violent and should be blamed. Purple: Both sides are to blame. Yellow: Some of the protestors were very fine people with legitimate reasons to protest that should not be condemned.

The color coding lets us see a major pivot point about halfway through the press conference. Before the pivot, Trump developed lines of argument that could excuse the equivocality of his Saturday statement as merely waiting for the facts required to make an unequivocal and superseding condemnation of the protestors on Monday. The dominant themes early in the interaction were that his statements were good (highlighted in green) and that he had to wait for the facts before making a full statement (highlighted in red). After the pivot, Trump developed lines of argument that were clearly inconsistent with a plain condemnation of the protestors, including reaffirmation that both sides held blame (highlighted in purple), condemnation of the alt-left (highlighted in light blue), and excluding some alt-right protestors (the “very fine people”) from any share of the blame (highlighted in yellow).

As he responded to the series of questions and challenges, the position Trump developed changed the sense that could be made of his earlier statements. They remained condemnations of violence, but they could no longer be heard as condemnations of racism and White nationalism, at least not in the way that many press conference reporters would accept. The statements could no longer be heard as condemnations of Nazis alone or of all the protestors. In addition, a sense of excuse seemed to mitigate the condemnation. Trump never openly withdrew or contradicted any of what he said; he just reframed it all.

3.2.2. Initial Questions and Argument Development

In this and the following sections, we will show the reporters’ contributions to Trump’s position-building and the emergence of his standpoint. The development of Trump’s position was reactive: it emerged from answers to questions posed by journalists, whose loosely coordinated but persistent efforts seemed to have been designed to force Trump (DT in the transcript) into either unmistakably condemning the Charlottesville protestors or openly refusing to do so.

The first question (02, Figure 4)3 comes from ABC’s Mary Bruce (R1). The open-ended WH-question is in line with the characteristically deferential stance press reporters take toward the President. It is already tinged with combativeness.4 The question about business leaders may appear to be loosely related to infrastructure, but it is not. It is about Trump’s Charlottesville statements, and everybody knows it. The question presumes that Trump knew who “these CEOs” were, and knew why they were resigning. And Trump did know. He had been tweeting back at a series of resignations by CEOs announced after his second statement on Charlottesville. Trump must hear that the point of the question was to address the criticisms those resignation announcements were raising. However, Trump resists the implicit agenda behind the question, evading the point by attributing their motive to not doing their jobs and not bringing jobs back into the country.

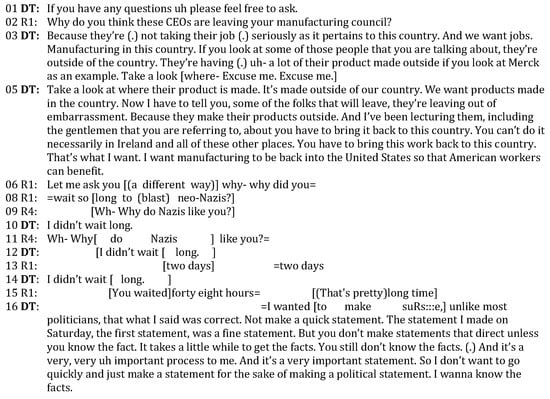

Figure 4.

Transcript excerpt 01–16.

Bruce’s next question (06/08 in Figure 4) presses the point, making it clear that Trump has not really answered the question by prefacing her follow-up with “Let me ask you (a different way)”. She then, in effect, formulates the CEOs’ reason for resigning: “Why did you wait so long to (blast) neo-Nazis?” This accusatory formulation (Clayman 2010) signals that Trump waited longer than normal (“so long”) and also implicates (in alignment with the CEOs) that a president should “blast neo-Nazis”. It is a call to account. Trump seemingly accepts the implicature that he should “blast neo-Nazis” by failing to deny it, but; however, he rejects waiting too long (10), defiantly repeating “I didn’t wait long” (12, 14) as Bruce cuts in to baldly refute his claim (13, 15). Already, the press conference has taken on an unusually aggressive and confrontational tone that has slipped far outside the neutralistic circle (Heritage and Clayman 2010, p. 240). Trump’s turn 16 (Figure 4) offers a justification for waiting: he needed to “know the facts”. This line of argument will be reiterated and developed throughout the first part of the press conference.5

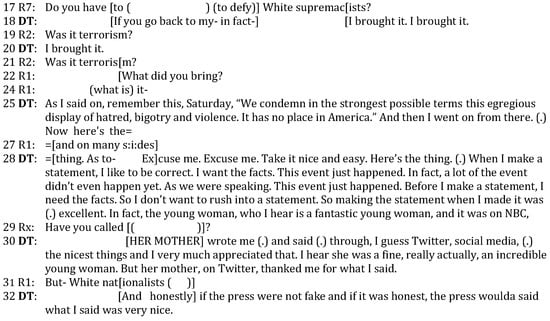

Wanting to have facts before making public statements is not unreasonable. However, the reporters refuse to accept this as accounting for the difference between the two statements. While Trump is still talking, an unknown reporter (R7) shouts out a question that was partly undecipherable but clearly meant as a rhetorical question, challenging the need to know any facts other than that the protestors were White nationalists (17, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Transcript excerpt 17–32.

Trump was keenly aware of the background controversies motivating Bruce’s and other reporters’ questions and challenges. This is evidenced in by the fact that he reads aloud a written version of his initial Saturday statement that he pulled from his pocket (18/20, Figure 5). Trump’s quote in (25, Figure 5) is apparently offered as proof that his first statement “was a fine statement” (16, Figure 4). However, he omits the portion he had ad-libbed on Saturday. He reads up to that point and then continues, “And then I went on from there”. Almost immediately in objection, Bruce interjects “and on many sides” (27), implicating that the incendiary phrase was the reason for public outcry. However, as he will continue to do later on when Bruce again brings up the phrase (75), Trump ignores her. He just continues to develop his rationale for making a second statement on Monday and then defends the Saturday statement as nevertheless “excellent” (28) and “very nice” (32).6 By this point, Trump has not offered any defense of his “many sides” statement, but neither has he openly backed down from it.

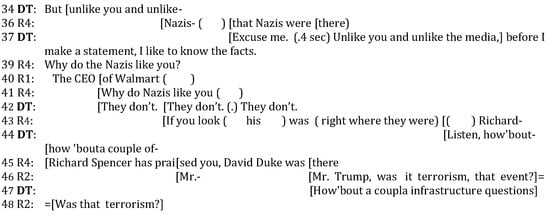

A chaotic exchange follows (see Figure 6). Reporter R4 asserts “Nazis were there” then twice shouts out the taunt “Why do Nazis like you?” (36, 39, 41; see also his prior taunts in 09 and 11, Figure 4). When Trump angrily shouts back, “They don’t. They don’t. They don’t” (42), the reporter baldly rebuts the denial without asking any question (43, 45). In turns 44 and 47, Trump asks for “a coupla infrastructure questions” and then looks at Mary Bruce, whose mention of “the CEO of Walmart” (40) may have seemed the most promising among bad alternatives.

Figure 6.

Transcript excerpt 34–48.

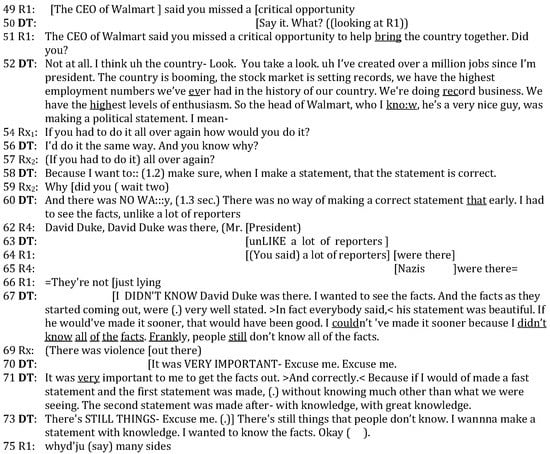

Bruce’s question (49, 51, Figure 7) turns out to pursue the issue behind her opening and follow-up questions regarding the CEO resignations—not the infrastructure agenda Trump had called for. As in his prior response (03/05, Figure 4), Trump steers the issue to the economy (52). However, he understands the reason for the CEO’s criticism: when asked by the next reporter if he had to do “it” all over again, how would he do “it” (54), Trump takes “it” as referring to his Charlottesville statements, not to the economic policies he had just raised (56). The question at least lightly calls for some acknowledgement of error.

Figure 7.

Transcript excerpt 49–75.

However, Trump will have none of it. He would “do it the same way” (56), and he reiterates his line that he wanted to make sure his statement was “correct,” that he “had to see the facts,” and that Saturday was too “early” (58, 60).

This defense meets immediate resistance from the reporters. In (59), a reporter (Rx2) accusatorily repeats Mary Bruce’s earlier criticism (13/15, Figure 4): why did Trump wait two days? Reporter R4 repeats his unanswered rebuttal that “David Duke was there” (62) and that “Nazis were there” (65). Mary Bruce shouts out a bald refutation: “You said a lot of reporters were there. They’re not just lying” (64/66). Another reporter asserts, “There was violence out there” (69). Finally, after Trump denies that he knew David Duke was there (67) and reiterates that he wanted to know all the facts and needed time to make a statement “with knowledge” (67, 70/71, 73), Mary Bruce calls out of the clamor, “whyd’ju (say) many sides” (75).7

Trump will not use this line of argument again. He will not assert again that his statements were of high quality. He will drop the argument that his need to know the facts and desire to make a correct statement were the reasons for the difference between the Saturday and Monday statements. However, he never actually backs down or withdraws those arguments.

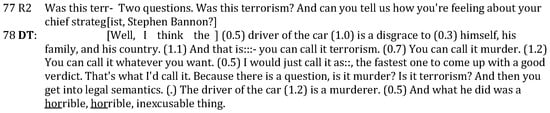

However, New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman (R2) is still after an answer to her terrorism question, which she shouted out four times before (19, 21, Figure 5; 46, 48, Figure 6). The question indexes the widespread criticism of Trump’s failure to denounce the Charlottesville protestors in terms he readily applied to acts of violence by non-Whites.8 When Trump gives her the floor (Figure 8), she adds a second question about Steve Bannon. Both questions present Trump with difficult dilemmas. For the first, to answer no would expose sympathy for racist White supremacists; to answer yes would offend these same groups. Thus, Trump dodges the question, treating it as just a matter of semantics. Although he clearly condemns the killing of Heather Heyer, he neither affirms nor denies that it was terrorism.

Figure 8.

Transcript excerpt 77–78.

Haberman’s second question may seem unrelated, but is in fact closely tied to the first. The question references an article Haberman had published the day before (Haberman and Thrush 2017). The article highlighted Bannon’s association with the alt-right, along with his efforts to dissuade the president from “antagonizing a small but energetic part of his base” by criticizing alt-right activists. It portrayed the president as wanting to distance himself from Bannon but being unable “to follow through”. Trump’s ambivalence toward Bannon was portrayed as a tension between “a foxhole friendship forged during the 2016 presidential campaign and concerns about what mischief Mr. Bannon might do once he leaves”. The two questions are really one: was Trump’s seeming reluctance to condemn the protest in Charlottesville or to call the murder terrorism because his “chief strategist” had warned him not to do so? Expressing confidence in Bannon might bolster this suspicion.

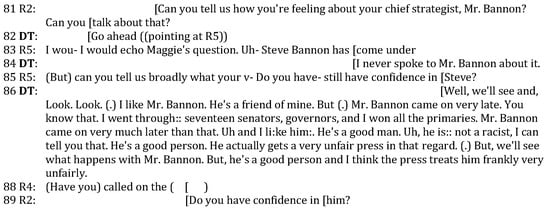

At first, Trump dodges the Bannon question. Rather than answer Haberman’s follow-up repeat of the second question (81, Figure 9), Trump calls on another reporter (82). In an unusual tag-team move, that reporter (R5) uses his opportunity to pursue an answer to “Maggie’s question” (83).

Figure 9.

Transcript excerpt 81–89.

When Trump says in turn 84 that he never spoke to Mr. Bannon about it, what is “it”? There is no clear prior referent in either (81) or (83). However, “it” can be linked to “this” in “was this terrorism?” In the question about Bannon, Trump hears suspicion that Bannon was advising him to not call the Charlottesville murder terrorism. The Haberman and Thrust article reported that “Mr. Bannon consulted with the president repeatedly over the weekend as Mr. Trump struggled to respond to [Charlottesville]”. Trump’s subsequent, evasive response (86) leaks his awareness of this article. Haberman and Thrush reported that his advisor was seen as “the mastermind behind the rise of a pliable Mr. Trump,” “the real power and brains behind the Trump throne,” and the reason for Trump’s election. Trump mentions that Bannon joined his campaign “very late,” after Trump had “gone through” seventeen primary opponents on his own. Trump also claims, without prompting, that Bannon “is not a racist”—another suggestion from the article (Trump: “He actually gets a very unfair press in that regard”). However, while Trump hears what Haberman’s second question is driving at, he does not really answer it, not even when she repeats her follow-up (89).

3.2.3. Candidate Standpoints at Midpoint

At this point in the analysis, it is worth taking stock of where things stand and how Trump and the reporters got there. First, the focal arguables in this press conference were the Saturday and Monday statements. Possible glosses of Trump’s position (“My statement was a good one,” “I needed to know the facts,” and “I could not make the Monday statement sooner”) are all subordinate considerations, arguments that responded to not-so-latent criticisms of his statements (such as “You did not condemn Nazis,” “You waited too long,” and “You should have called the killing terrorism”). The question-answer interaction explored the disagreement space around the speech acts of condemning and criticizing.

Trump himself characterized his two statements as condemnations. That label was used in the part of his Saturday statement that he re-read (25, Figure 5).9 All of Trump’s subordinate standpoints and arguments seemed to be designed to defend that speech act. Whether the reporters were challenging the felicity of the condemnations or challenging their very characterization as condemnations is somewhat obscure. However, their questions clearly signaled their negative assessments of Trump’s Charlottesville statements.

Second, the questioning by reporters amounts to a loosely coordinated effort to implement a remedial interchange (Goffman 1971) that would get Trump to admit and repair wrongdoing in his statements (e.g., failure to forcefully condemn the protestors, to do so in a timely manner, and without reluctance or equivocation), otherwise risk exposing himself as a fascist and racist sympathizer. In the face of Trump’s resistance, the reporters have repeatedly broken the pretense of disinterested inquiry. Their lapses into open objection and counterargument come off as acts of censure.

Nevertheless, Trump appeared to concede ground and adopted a less provocative position (and corresponding standpoint) in the early unfolding of the question-and-answer period. In important ways, his argumentative position in the press conference seemed to commit him to a refashioned, more circumscribed and unequivocal, less qualified sense of condemnation. At midpoint, Trump has defended his Saturday and Monday statements in a way that even more strongly committed him to those statements as the kind of condemnations of the protestors that the reporters seemed to want to hear. He accepted the implicature in Mary Bruce’s early follow-up question that he should “blast” neo-Nazis. By omitting the “on many sides” ad-lib, his revisionary re-reading of the Saturday statement could implicate that he no longer blamed both sides. In addition, his defense of his statements could be taken as at least implicating that he would now denounce the Charlottesville protestors for racism, lay the blame on them for the violence and Heather Heyer’s death, and more generally disavow the racist agenda of the White supremacist alt-right. Still, Trump had not said or done any of this openly and directly.

3.2.4. The Pivot

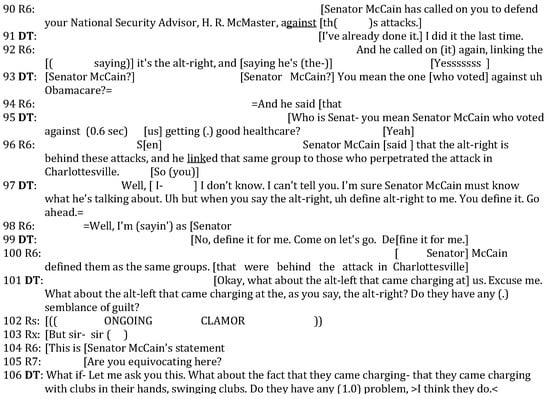

Halfway through the question-answer interaction, at around turn 97 (Figure 10), a pivot point is reached. Trump begins demanding answers from his questioners, interrogating them. In addition, he will respond to further questions and objections with new lines of argument. Those new lines of argument change the force and significance of all that he had externalized thus far.

Figure 10.

Transcript excerpt 90–106.

Trump calls on reporter R6 rather than answering Haberman’s follow-up about his confidence in Steve Bannon (89, Figure 9). R6 reports Senator John McCain’s call for Trump to defend his National Security Advisor against attacks (90, Figure 10). The topic would seem to be a new one, but R6 never gets to her question. Trump cuts her off, dismissing McCain’s call (91), and interrupting again to attack McCain for casting the decisive vote that blocked the repeal of Obamacare (93/95). When R6 announces that McCain linked McMaster’s “alt-right”10 attackers to those “who perpetrated the attack in Charlottesville” (96), Trump aggressively demands that she “define alt-right” (97, 99). In turns 98 and 100, R6 adopts the neutralistic footing of a reporter (Clayman 1992), offering McCain’s definition: he “defined them as the same groups”. The lurking agenda is brought close to the surface: would Trump side with his advisor, McMaster, against the same alt-right attackers behind Charlottesville?

Before R6 completes “that were behind the attack in Charlottesville,” Trump cuts her off again. To the audible gasp of the press corps, he blurts out: “What about the alt-left that came charging at us. Excuse me. What about the alt-left that came charging at the, as you say, the alt-right? Do they have any semblance of guilt?” (101). The stunned press corps erupts (102). Then, as if to double down on the force of what he has just done, over the din of the reporters, Trump amplifies his “what about” challenges with more rhetorical questions: “What about the fact that they came charging … with clubs in their hands, swinging clubs? Do they have any problem?” He rapidly spits out his own answer: “I think they do” (106). The significance of what Trump has done is apparent to everyone—as captured by an unknown reporter screeching out over the clamor: “Are you equivocating here?” (105). Perhaps not equivocating, at least not any longer, but he certainly is escaping the net of commitments toward which the press corps had been channeling him.

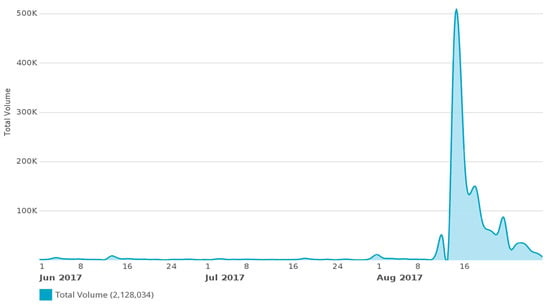

Trump’s introduction of the term ‘alt-left’ is a telling indicator of his alignment with the protestors. This is not just a matter of contrasting semantics, but one of social positioning. Trump could have asked, “What about the counter-protestors?” but instead chose a term that, at the time, was used exclusively by the far right. ‘Alt-left’ was not widely known or used prior to the press conference. Trump’s use placed him among those few who were using the term and showed the intimacy of his knowledge of that social world. Figure 11 shows the results of a search (using Crimson Hexagon) for Twitter mentions of ‘alt-left’. Few tweets used the term before the press conference, and a qualitative review of its earlier use shows use primarily by alt-right sympathizers to describe their opposition. ‘Alt-right’ was invented as a term of self-reference; ‘alt-left’ was coined as an epithet. Trump’s argument that “the alt-left” also engaged in violence was an act of alignment with those alt-right users.

Figure 11.

Tweets mentioning ‘alt-left’ before and after the 15 August press conference.

An even clearer signal of Trump’s alignment can be found in turn 101, where Trump appears to say the alt-left came charging at “us”. Our transcription is open to challenge: All other published transcripts show this as “em” (or as indecipherable). “Us” appeared at first in Politico’s transcript; however, they amended it after White House objections. After listening repeatedly to all the recordings posted by news organizations, we believe that Politico had this right the first time. Trump utters a monosyllabic word that begins with a vowel and ends with “s”. The video shows no lip closure required for “m”. In addition, it does not sound like he cut off “em” and slid into an elided “e- -scuse me” (if that is even phonologically possible). A slip of the tongue, “us,” would explain the subsequent repeat repair. After a hitch and parenthetical marker, “us” in the prior sentence is reformulated as “the alt-right”: “What about the alt-left that came charging at the- as you say, the alt-right?” (hitch, marker, and replacement underlined in bold; see Kitzinger 2013, pp. 234–36). Trump signals that he misspoke.

Before the pivot, Trump seemed willing to shed the “on many sides” ad-lib and all that it implicated. Now, at the pivot point, Trump openly defends the alt-right—not for their attacks on McMaster, but for their violence in Charlottesville. Rather than backing down from the Saturday ad-lib apportioning blame, he bolsters it. He has now mitigated, even excused, alt-right violence.11 This line of argument will be reiterated and developed throughout the remainder of the press conference.12

3.2.5. Trump Leans into Opposition

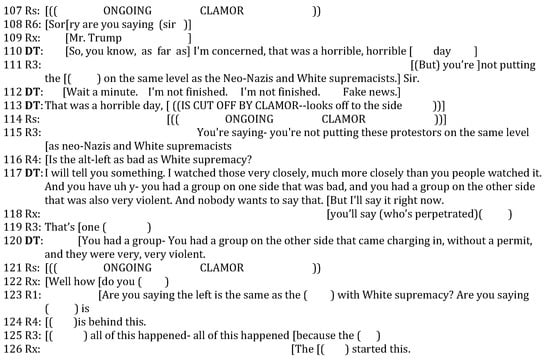

Trump’s new position received a flurry of calls to, in effect, take it back (“Are you saying?” “You’re not putting”). Figure 12 contains what we could make out from reporters close enough to a microphone during the uproar. Even interrogative sentences (108, 123) sound incredulous. From here on, while Trump continues to call on and receive questions, many reporters simply move into an openly oppositional argument of a kind not found in any previous reports of Presidential news interviews or press conferences.

Figure 12.

Transcript excerpt 107–126.

The clamor at this point is so loud and unrelenting that, after trying to shush the mob, Trump stops talking altogether and simply looks away (112/113). His “both sides” comments (117, 120) incite more clamor.

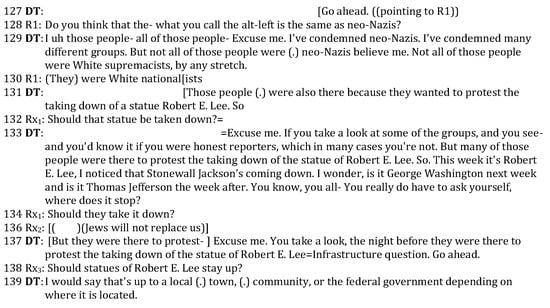

When Trump calls on Mary Bruce (Figure 13), he develops another new line of argument that leaves the reporters perhaps even more exasperated and bewildered. When asked if he thinks that the alt-left “is the same as neo-Nazis” (128), Trump affirms that he had condemned neo-Nazis and “many groups,” but denies that all the Charlottesville protesters were neo-Nazis or White supremacists “by any stretch” (129). Two implicatures are worth unpacking. First, by failing to disagree with the direction of Bruce’s question, Trump tacitly accepts the equivalence. Second, he excludes many protestors from condemnation by denying that they all were neo-Nazis or White supremacists.

Figure 13.

Transcript excerpt 127–139.

In (130), Bruce denies the basis for immunity (“They were White nationalists”). Perhaps in response to her contradiction, Trump interrupts to retort that “those people were also there (…) to protest the taking down of a statue [of] Robert E. Lee,” implicating a difference from protesting in favor of White nationalism.13 He then develops a slippery slope argument for their protest that nominally has nothing to do with White nationalism and that he himself seems to endorse (133).

The slipperiness of implicated commitments and standpoints, and the difference between what someone actually says and openly acknowledges and what someone is only projected to commit to is neatly illustrated when a reporter presses Trump to explicitly confirm his agreement with the protestors (138). Trump adopts a weaker kind of alignment, in now characteristically equivocal fashion (139). When pressed, he is noncommittal to the protestors’ demand that the statue remain in place. In effect, he only commits to the protestors having a legitimate rationale.

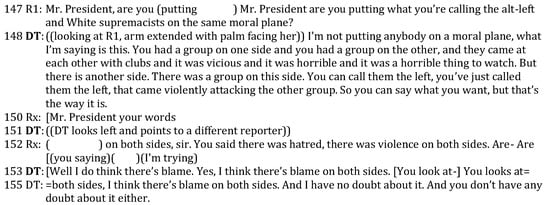

Dodging a more pointed follow-up (“Are you against the Confederacy?”; 141, full transcript in (Jacobs et al. 2022)), Trump took a more general question about race relations (143, full transcript), which he used to return to the press conference’s infrastructure theme, saying the “millions of jobs” he “brought back into the country” would have “a tremendous impact on race relations” (144, full transcript). However, reporters again ignore the infrastructure theme. In turn 147 (Figure 14), Mary Bruce all but repeats her questions from turns 123 (Figure 12) and 128 (Figure 13). This time, she draws out an inferential consequence: Trump has put the alt-left and White supremacists on the same moral plane (cf. Clayman 2017). Trump denies this and restates “what I’m saying” (148). Trump’s answer still does not satisfy the reporters. In (152) Bruce’s line is recycled.

Figure 14.

Transcript excerpt 147–155.

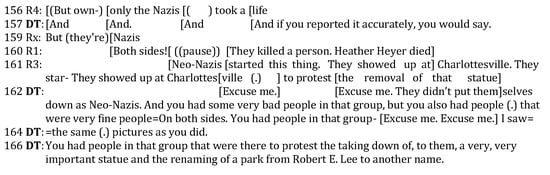

More clamor follows Trump’s insistence on putting “blame on both sides” (155, Figure 14). He is again shouted down with baldly assertive counterarguments (Figure 15). Mary Bruce simply exclaims “Both sides!” (160) and then shouts out, “They killed a person. Heather Heyer died”. On the recordings, other reporters can be heard shouting “But own- only the Nazis took a life” (156) and “But they’re Nazis” (159). CNN’s Jim Acosta objects: “Neo-Nazis started this thing. They showed up at Charlottesville. They star- They showed up at Charlottesville to protest the removal of that statue” (161). In response to this wave of counterargument, Trump cuts in to retort, “They didn’t put themselves down as neo-Nazis” and this time asserts that not only were there “some very bad people in that group, but you also had people that were very fine people, on both sides” (162). Then he reiterates the Robert E. Lee statue motive for the protest (166).

Figure 15.

Transcript excerpt 156–166.

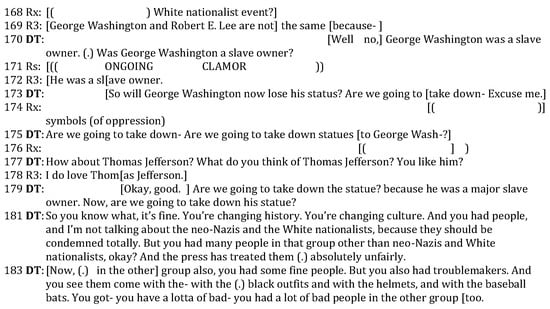

Trump’s position and standpoint is finally clear to the reporters, and is clearly unacceptable to them. In the ongoing clamor that initiated the talk shown in Figure 16, Trump cuts off CNN news reporter Jim Acosta, who is still openly counterarguing against Trump’s slippery slope argument from turn 133 (Figure 13).

Figure 16.

Transcript excerpt 168–183.

Trump turns the tables and again switches roles, asking the reporter questions that obtain concessions (170, 177) followed by “punchline” questions (173/175, 179) showing the contradiction between Acosta’s concessions and the logic of his defense for removing Robert E. Lee’s statue. In a kind of summary conclusion (181/183), Trump frames the protest as an expression of concern for “history” and “culture”, rather than as an expression of White supremacy. He distinguishes the defenders of history and culture from neo-Nazis and White nationalists. He acknowledges “some fine people” on both sides but insists that there were “troublemakers” and “a lot of bad people” among the counter-protestors. Moreover, he reasserts that the press treated the legitimate protestors “absolutely unfairly”.14 The reporters’ collective strategy of posing questions designed to obtain a backdown on pain of exposure has not gone as hoped. Somehow, Trump has slipped through their net.

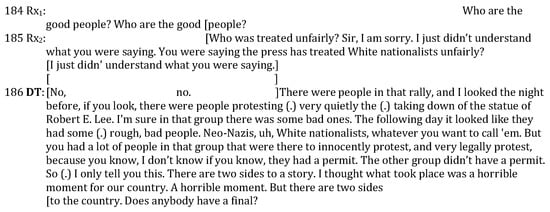

Further follow-up questions (184, 185, Figure 17) indicate the reporters’ difficulty even processing Trump’s position that not all the protestors were White nationalists or neo-Nazis.

Figure 17.

Transcript excerpt 184–186.

By the end of his statement in (186, Figure 17), Trump and the press corps are at a standoff. The reporters’ repeated challenges on the variations of the same topical agenda indicate that they are not at all satisfied with Trump’s answers. They do not accept that any people could be “innocently” protesting the removal of Robert E. Lee’s statue or that there could be any “good” or “fine” people in that group. They do not accept Trump apportioning blame to counter-protestors. In addition, they do not accept Trump using that blame to qualify and mitigate the condemnation of the protestors.

Trump, for his part, has supplemented and qualified what seemed to be his initial position, carefully restricting the blame to “very bad people,” and not extending it to all the protestors or even to the alt-right. He has avoided attributing either racism or responsibility for violence to the “very fine people” among the protestors. He has conveyed sympathy for their cause without openly endorsing the racist attitudes and beliefs that are at the center of that cause. The meaning of his “condemnation” has changed from the direction it seemed to be going earlier. His arguments have erased the distinctions between racial motivation for violence and other kinds of motivation, between racially motivated hatred and other kinds of hatred. In addition, he has lumped all together murder, beatings, assaults, fights, and scuffles as condemnable violence.

Finally, after answering a solicited question on infrastructure and one on whether he had spoken to Heather Heyer’s family, Trump left the podium.

4. Conclusions

Throughout this press conference, the object of argument—the arguable—proved itself not to have had a stable, definitive sense or force prior to the argument. Even when glossed as a condemnation, its meaning remained open and contestable. Exactly what President Donald Trump was doing in his Saturday and Monday statements on Charlottesville emerged over the course of his defenses, built up in response to queries and attacks. As one set of arguments at the beginning of the press conference developed Trump’s position, the sense of his statements as a condemnation took on one appearance. As he added new lines of argument later, the nature of that “condemnation” radically changed. Callouts often test not only the grounds for a standpoint, but what, if any, standpoint is being taken. Probed by the press corps, Trump appeared to be searching for his standpoint.

We maintain that this is how even “normal” argumentation works. If argumentation is a language game played with a scoreboard of commitments (Lewis 1979), players keep a running score in smeary chalk. Managing to get things put “on the record” is no easy task, and its accomplishment at one moment may be undone in the next. It is especially difficult to play two games at once, all the more so when one team of players (here, the reporters) must make piecemeal contributions, unplanned far down the line, their chance at a turn dependent on selection by an evasive respondent. Perhaps a standoff should count as a win in this kind of game.

This study of argumentation, carried out from the vantage point of pragmatics, proved to be revealing. It placed at center stage the properties of argument that the mainstream studies of argument downplay—its communicative and interactional foundations. Students of language use have long recognized the importance of context in providing meaning to utterances (cf. Garfinkel and Sacks 1970; Grice 1989; Sperber and Wilson 1986). Literal propositional meaning invariably underspecifies and leaves open-ended the meaning that is conveyed. Likewise, the temporal unfolding and interactional production of the elements of argument (e.g., standpoints and positions) reveal their social existence and functional design. These are not methodological problems to be overcome through reconstruction or incidental preliminaries to be erased through analytic reduction. They are essential properties to be captured and incorporated into the analysis of argument.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J. (Scott Jacobs), S.J. (Sally Jackson) and X.Z.; methodology, S.J. (Scott Jacobs), S.J. (Sally Jackson) and X.Z.; investigation, S.J. (Scott Jacobs), S.J. (Sally Jackson) and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J. (Scott Jacobs), S.J. (Sally Jackson) and X.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.J. (Scott Jacobs), S.J. (Sally Jackson) and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Jacobs, Scott, Xiaoqi Zhang, and Sally Jackson. 2022. Transcript of Press-Trump Exchange from the Podium, Trump Tower lobby, 15 August 2017. [PDF document deposited for open access at IDEALS: Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship.]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2142/114175 (accessed on 9 June 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | During Senate hearings on a White House coverup of a break-in at Democratic party headquarters in the Watergate Hotel, Republican Senator Howard Baker famously asked, “What did the President know and when did he know it?” |

| 2 | Confederate monuments had become contested as symbols of White supremacy (Pereira-Fariña et al. 2022). |

| 3 | Numbers in parentheses indicate turn. |

| 4 | Many transcripts circulated by news outlets begin R1′s question with the customary deferential address form, “Mr. President”. No initial address form is audible on any recording. |

| 5 | Six times Trump says something to the effect that he did not want to make a “quick” statement (turn 16), “to rush” into a statement (28, Figure 5), or to make a “fast statement” (71, Figure 8); that Saturday was too “early” (60, Figure 8); and that he could not have made his Monday statement sooner (67, Figure 8). He says he waited until Monday so that he knew “the facts” and what he said was “correct” (16, Figure 4). Four other turns (28, Figure 5; 58, 60, and 71, Figure 8) repeat that he wanted to make sure that what he said was correct. The importance of knowing the facts is mentioned thirteen times in the first five minutes of questioning (four times in turn 16, Figure 4; then twice in 28, Figure 5; again in 37, Figure 6; and 60; three times in 67; and finally, in 71 and 73, all in Figure 7). See red color coding in Figure 3. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Oddly, reporters never directly asked what new facts led to the Monday revisions or what Trump thought he knew at the time to justify his Saturday statement. |

| 8 | (Bump 2019) compiles Trump’s well-known history of making “fast” condemnations of violence by non-Whites, often labeling them as terrorism, while remaining silent on violent acts by Whites. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | As the editor of Breitbart News, Steve Bannon openly proclaimed, “We’re the platform for the alt-right” (Posner 2016). |

| 11 | He has also made moot the standing of the argument that he needed facts and time to make a correct statement. |

| 12 | Twice, he will describe “one side” and “the other side” as “very violent” (117, 120, Figure 12). He will later say, “you had a group on one side and you had a group on the other” who “came at each other with clubs” and “a group on this side (…) the left, that came violently attacking the other group”. It was “horrible” and “vicious” (148, Figure 14). Still later, he will assert that the counter-protestors “also had troublemakers” and “a lot of bad people”. He will point out their black outfits, helmets, bats, and clubs (183, Figure 16). See light blue color coding in Figure 3. |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Notice Trump’s stance here allows the same slipperiness and strategic equivocality as with the prior version of the argument (139, Figure 14). |

References

- Brendan. n.d.Trump Twitter Archive [4 May 2009, 2:54:25 P.M. EST–8 January 2021, 10:44:28 A.M. EST]. Available online: thetrumparchive.com (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Bull, Peter. 2008. “Slipperiness, evasion, and ambiguity”. Equivocation and facework in noncommittal political discourse. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 27: 333–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bump, Phillip. 2019. How Trump Talks about Attacks Targeting Muslims vs. Attacks by Muslims. Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/03/18/how-trump-talks-about-attacks-targeting-muslims-vs-attacks-by-muslims/?utm_term=.323d083d515e (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- C-SPAN. 2017. Donald J. Trump Commenting on the Violence Charlottesville. User Clip: Many Sides. Available online: https://www.c-span.org/video/?c5011166/user-clip-sides (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Clayman, Steven E. 1988. Displaying neutrality in television news interviews. Social Problems 35: 474–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, Steven E. 1992. Footing in the achievement of neutrality: The case of news interview discourse. In Talk at Work. Edited by Paul Drew and John Heritage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 163–98. [Google Scholar]

- Clayman, Steven. 2010. Questions in Broadcast Journalism. In “Why Do You Ask?”: The Function of Questions in Institutional Discourse. Edited by Alice F. Freed and Susan Erhlich. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 256–78. Available online: https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195306897.001.0001/acprof-9780195306897-chapter-12 (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Clayman, Steven. 2017. The micropolitics of legitimacy: Political positioning and journalistic scrutiny at the boundary of the mainstream. Social Psychology Quarterly 80: 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, Steven, Marc N. Elliott, John Heritage, and Laurie L. McDonald. 2006. Historical trends in questioning presidents. Presidential Studies Quarterly 36: 561–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayman, Steven, and John Heritage. 2002. The News Interview: Journalists and Public Figures on the Air. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eemeren, Frans H., Rob Grootendorst, Sally Jackson, and Scott Jacobs. 1993. Reconstructing Argumentative Discourse. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, Harold, and Harvey Sacks. 1970. On formal structures of practical action. In Theoretical Sociology. Perspectives and Developments. Edited by John C. McKinney and Edward A. Tiryakian. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, pp. 337–66. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1971. Remedial interchanges. In Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New York: Basic Books, pp. 95–187. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, Paul. 1989. Studies in the Way of Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haberman, Maggie, and Glenn Thrush. 2017. Bannon in Limbo as Trump Faces Growing Calls for the Strategist’s Ouster. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/14/us/politics/steve-bannon-trump-white-house.html (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Heritage, John, and Steven Clayman. 2010. Talk in Action. Interactions, Identities, and Institutions. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781444318135 (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Heritage, John, and Steven E. Clayman. 2013. The changing tenor of questioning over time: Tracking a question form across U.S. presidential news conferences 1953–2000. Journalism Practice 7: 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holan, Angie Drobnic. 2017. In Context: President Donald Trump’s Statement on ‘Many Sides’ in Charlottesville, Va. PolitiFact. Washington, DC and St. Petersburg: Poynter Institute. Available online: https://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/article/2017/aug/14/context-president-donald-trumps-saturday-statement/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Innocenti, Beth. 2022. Demanding a halt to metadiscussions. Argumentation 36. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Sally. 1986. Building a case for claims about discourse structure. In Contemporary Issues in Language and Discourse Processes. Edited by Donald G. Ellis and William A. Donohue. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 129–47. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Sally. 1992. “Virtual standpoints” and the pragmatics of conversational argument. In Argumentation Illuminated. Edited by Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, J. Anthony Blair and Charles A. Willard. Amsterdam: International Centre for the Study of Argumentation (SICSAT), pp. 260–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Sally. 2019. Reason-giving and the natural normativity of argumentation. Topoi 38: 631–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Sally, and Scott Jacobs. 1980. Structure of conversational argument: Pragmatic bases for the enthymeme. Quarterly Journal of Speech 66: 251–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Scott. 1986. How to make an argument from example in discourse analysis. In Contemporary Issues in Language and Discourse Processes. Edited by Donald G. Ellis and William A. Donohue. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 149–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Scott. 1988. Evidence and inference in conversation analysis. In Communication Yearbook 11. Edited by James A. Anderson. Newbury Park: Sage, pp. 433–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Scott. 1989. Speech acts and arguments. Argumentation 3: 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Scott. 1990. On the especially nice fit between qualitative analysis and the known properties of conversation. Communication Monographs 57: 243–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Scott. 1999. Argumentation as normative pragmatics. In Proceedings of the Fourth ISSA Conference on Argumentation. Edited by Frans H. van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, J. Anthony Blair and Charles A. Willard. Amsterdam: International Centre for the Study of Argumentation (SICSAT), pp. 397–403. Available online: https://rozenbergquarterly.com/issa-proceedings-1998-argumentation-as-normative-pragmatics/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Jacobs, Scott. 2002. Maintaining neutrality in third-party dispute mediation: Managing disagreement while managing not to disagree. Journal of Pragmatics 34: 1403–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Scott. 2016. Employing and exploiting the presumptions of communication in argumentation: An application of normative pragmatics. Informal Logic 36: 159–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jacobs, Scott, and Sally Jackson. 1989. Building a model of conversational argument. In Rethinking Communication, Vol. 2: Paradigm Exemplars. Edited by Brenda Dervin, Lawrence Grossberg, Barbara J. O’Keefe and Ellen Wartella. Newbury Park: Sage, pp. 153–71. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Scott, Xiaoqi Zhang, and Sally Jackson. 2022. Transcript of Press-Trump Exchange from the Podium, Trump Tower lobby, August 15, 2017. [PDF Document Deposited for Open Access at IDEALS: Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship.]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2142/114175 (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Kauffeld, Fred J., and Jean Goodwin. 2022. Two views of speech acts: Analysis and implications for argumentation theory. Languages 7: 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, Celia. 2013. Repair. In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Edited by Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 229–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, David. 1979. Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic 8: 339–59. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00258436 (accessed on 9 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Dima. 2018. Argumentation in Prime Minister’s Question Time: Accusation of Inconsistency in Response to Criticism. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, Dima. 2019. Standing standpoints and argumentative associates: What is at stake in a public political argument? Argumentation 33: 307–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musi, Elena, and Mark Aakhus. 2018. Discovering argumentative patterns in energy polylogues: A macroscope for argument mining. Argumentation 32: 397–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Fariña, Martin, Marcin Koszowy, and Katarzyna Budzynska. 2022. It was never just about the statue’: Ethos of historical figures in public debates on contested cultural objects. Discourse & Society 33: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcar, Leah, and Scott Jacobs. 1997. Evasive answers: Reframing multiple argumentative demands in political interviews. In Argument in a Time of Change: Definitions, Frameworks, and Critiques. Proceedings of the Tenth NCA/AFA Conference on Argumentation. Edited by James F. Klumpp. Annandale: National Communication Association, pp. 226–31. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2294942/Evasive_answers_Reframing_multiple_argumentative_demands_in_political_interviews (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Posner, Sarah. 2016. How Steve Bannon Created an Online Haven for White Nationalists. Mother Jones 41: 4. Available online: https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2016/08/stephen-bannon-donald-trump-alt-right-breitbart-news/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Romaniuk, Tanya. 2013. Pursuing answers to questions in broadcast journalism. Research on Language & Social Interaction 46: 144–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Molly. 2017. He Finds the Words. Full Text: Donald Trump Says “Racism Is Evil” in His Latest Statement on Charlottesville. QUARTZ. [Website, qz.com]. August 14. Available online: https://qz.com/1053270/full-text-donald-trumps-statement-on-charlottesville/ (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1988. From interview to confrontation: Observations of the Bush/Rather encounter. Research on Language and Social Interaction 22: 215–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidnell, Jack. 2013. Basic conversation analytic methods. In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis. Edited by Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, Dan, and Dierdre Wilson. 1986. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Eileen, and Maggie Haberman. 2017. Trump Shares, Then Deletes, Twitter Post of Train Hitting Cartoon Person Covered by CNN Logo. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/15/us/politics/trump-shares-then-deletes-twitter-post-of-cnn-cartoon-being-hit-by-train.html?searchResultPosition=1 (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Weger, Harry, Jr., and Mark Aakhus. 2005. Competing demands, multiple ideals, and the structure of argumentation practices. A pragma-dialectical analysis of televised town hall meetings following the murder trial of O.J. Simpson. In Argumentation in Practice. Edited by Frans H. van Eemeren and Peter Houtlosser. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Joseph, Nickolas Vance, Chen Wang, Luigi Marini, Joseph Troy, Curtis Donelson, Chieh-lee Chen, and Mark D. Henderson. 2020. The Social Media Macroscope: A science gateway for research using social media data. Future Generation Computer Systems 11: 819–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).