Abstract

The present research paper explores the effects of relexification in the context of an in-group jargon variety. Specifically, it addresses the role of Romani as a supplier language in the process of lexical renewal that is ongoing in Dritto—the jargon of the Italian Travellers. Considered the most ancient descendant of the Italian historical jargon of the Roads, Dritto is a secret code which is still actively used within some socially marginalized service-provider communities, such as the families involved in the circus and the travelling show business. At the margins of the mainstream society, the families of Dritti entertainers share their living and economic spaces with the families of Italian Sinti, whose presence has been documented in Italy for centuries. As a consequence of this intense and prolonged cohabitation, Romani elements have always been documented in the corpora of Italian historical jargon. However, a considerably more significant contribution has recently been documented by researchers among the funfair workers in northern Italy. This work examines the driving factors behind this contact-induced shift by considering the changing socio-economic context faced by the travelling community in the last decades.

1. Introduction

The concept of ‘relexification’, in use since the 60s in creole studies and whose roots can be traced back to the late 19th century (DeGraff 2002, p. 325), was for the first time formally theorized by Muysken (1981) in the context of the analysis on Media Lengua, i.e., a mixed language spoken in Ecuador resulting from the insertion of the Spanish lexicon in the syntactic structure of Quechua. The phenomenon is described as “the process of vocabulary borrowing in which the borrowed element adopts the meaning and use of the element in the receptor language for which it is substituted” (Muysken 1981, p. 55). It is thus recognized as a form of vocabulary substitution where the only element acquired from the target language is the phonological representation, while syntactic features and semantic representations remain unaltered. According to Muysken’s proposal, in order for relexification to occur, the semantic representations of source and target language entries must partially overlap and the two entries must be associated with each other. The mechanism results from the combination between linguistic and other non-linguistic factors which can be political, social, communicative and identificatory (Horvath and Wexler 1997, p. 12).

Subsequently, the theory of relexification was adopted and reworked by Lefebvre and her research team at Université Québec à Montréal (UQAM), which study conducted on the Haitian Creole led to the ‘Relexification Hypothesis for creole genesis’ (Lefebvre and Lumsden 1989; Lefebvre 1993, 1998).

A closely related process is later introduced by Mous (1994) under the name of ‘paralexification’. This is the process by which parallel words sharing meaning and morphological extensions and proprieties exist for the same lexical entry. The term is initially designed for the description of the paralexis system in Mbugu—a mixed language—and is later associated also with the formation of argot, secret languages, slang, ritual languages, taboo languages and similar varieties (Mous 2002). These varieties are defined by the studies as Sondersprachen ‘special languages’ (Siewert 1996), or also known as ‘anti-languages’ (Halliday 1976), i.e., an age or group specific subvariety of a language used by some social groups for the internal communication. In Mous (2003) each of these cases is addressed within the framework of a discussion on the conscious and functional use of linguistic manipulation by means of different strategies, which allow the speakers to control over their language and communicate effectively in a variety of circumstances.

As discussed by Lefebvre (1997) relexification and paralexification represent in two slightly different ways, the same cognitive process that can be referred to as ‘relabelling’ (further discussed in Lefebvre 2008), occurring in a large number of language contact contexts. However, in spite of the attention on its role in the emergence of mixed languages and pidgins and creoles as well in the cases of second language acquisition (cf. Lumsden 1999), less emphasis has been given to how this process applies to the formation of special languages.

Already Halliday’s (1976) early contribution refers to the phenomenon, named ‘relexicalisation’ to address the formation of a second distinctive vocabulary used to encode certain areas of the official language, which are considered central to certain ‘subculture’. Later on, Wittmann (1992) briefly discussed to the importance of relexification in the formation of two special vocabularies, namely ‘joual’ and ‘argot’. These are defined as new varieties created by the acquisition of a number of new lexical resources into the grammatic frame of an existing language; resources which can either be shaped on a language external to the community (in the case of joual) or can result from a process of manipulation of internal linguistic material (in the case of argot).

These studies show a full awareness on the process of lexical substitution typical of the formation of special languages. Despite this, the social process underlying this substitution has never been fully described, nor has been observed the way in which manipulation may replicate in time, reflecting a group identity in constant negotiation.

Taking into account this theoretical framework, the present research explores the effects of relexification in the context of an in-group special variety. Specifically, it addresses the role of Romani as a supplier language in the process of lexical renewal ongoing in the jargon of the Italian Travellers and the functional advantage this has in internal communication. The processes of relexification and expansion are analysed as a consequence of the growing prestige of the Sinti families within this specific peripatetic community and in the light of the socio-economic changes faced in the last decades.

2. Research Context

2.1. The Socio-Economic Setting

The funfair—contemporary embodiment of the medieval fair—is a special economic niche that gathers different social groups linked in multiple different ways to the world of travel. The condition of social marginality and the different lifestyle characterizing this separate world strengthen the Travellers’ perception of belonging to a close-knit community whose sense of self-ascription is built day-by-day in opposition to the outside world, the ‘sedentary’ world. While living on the margins of mainstream society, the funfair community maintains its integrity in spite of, and through, the constant movement and the geographical dispersion across the Italian territory. The dichotomy between inside and outside, flexibility and routines, Travellers and settled, is the ideological distinction around which reality is shaped and reproduced.

The profession is strongly marked in terms of identity and is transmitted from father to son over generations. This transmission also applies to the funfair ride, which is considered to be the centre of the family’s economic life and the symbol of its prestigious status within the community. The rides, as well as the caravans, constitute the core of the material culture that is shared by all Travellers and linked to an equally specific way of living, dwelling, and moving. Together with this, Travellers also agree on certain economic strategies, mostly governed by implicit rules and standards of behaviour. The Travellers community is built upon a social hierarchy which is based on the seniority of families in the world of travel, and it is organized around a dense network relying on marriage alliances.

Despite its evident cohesion in opposition toward the majority society, the fieldwork data shows the funfair as a complex and multifaceted world, where various and rather dynamic feelings of affiliation are likely to be detected, since they evolve in a daily process of membership self-construction (Tribulato 2019). In such a heterogeneous context the individual identity is always relational and is negotiated on the basis of similarity or opposition to other people.

The environment is nowadays shared among Sinti travelling entertainers as well as non-Sinti Travellers who define themselves as ‘Dritti1’. This self-identification is of Italian origin and translates as ‘straight’, here used metaphorically as ‘smart’, ‘cunning’. It was used to describe a large and non-homogeneous group of Travellers who used to frequent seasonal markets and fairs throughout Italy and is now commonly used to designate Italian showmen on the basis of blood affiliation, i.e., people who are born in the environment of the funfair or circus from Traveller parents. The status of being Dritto cannot be acquired over time, such as through marriage, and likewise cannot be lost. For instance, the Dritti may live a sedentary lifestyle for many years and still be recognized as Travellers by the community.

The families of Dritti entertainers share their living and economic spaces with the families of Italian Sinti, whose presence has been documented in Italy for centuries (Piasere 1992). The Sinti families are organized in different groups, based in northern Italy and some parts of central Italy, and they often identify themselves with the name of the region of their first settlement.2 Their continuous presence in the region and short-range nomadism favoured the integration of these groups in the local economic contexts and their collaboration with other vagrants into some special environment such as the travelling show business.

Alongside Dritti and Sinti, two groups that already imply a certain internal variability, there are also several gagi3, that is people who are not Travellers by origin who have joined the world of travel for economic reasons or marriage ties.

2.2. The Language-Scape

The heterogeneous ethnic and identity-related environment of funfair determines an equally complex and multifaceted linguistic panorama in which different linguistic codes interact with each other and create similarities and differentiations, links and borders. The daily choices made by the speakers correspond to temporary and changing contexts. Thus, they reflect both the individuals’ sense of belonging as well as the social dynamics of proximity, estrangement, prestige, sympathy and repulsion. The division between varieties, similarly to that between social groups (Sinti, Dritti, gagi), appears to be blurred as a contextual and fluid result of the continuous process of negotiation. In the regions where my research has been conducted, from an internal perspective it is possible to identify four linguistic varieties to which the speakers refer while defining their linguistic performance:

- (i)

- Gagi: The term ‘Gagi’ refers in this context to the internal use of the language of the mainstream society, such as Italian, the local dialect of Italian or other national languages. To speak well ‘in Gagi’ is considered an important skill to attract clients, talk to suppliers, relate to local authorities, and thus have a successful working activity.

- (ii)

- Dritto: An Italo-Romance-based jargon composed of a small number of specific terms which are embedded into the grammatical structure of Italian and are traditionally used by Dritti Travellers as an internal code of communication and a mark of identity.

- (iii)

- Lombard Sinti: A variety of Romani which belongs to the north-western branch (for the classification of Romani dialects see Matras 2002, 2005; Elšík and Beníšek 2020). The use of Lombard Sinti is no longer common in everyday-life domains, but it is still used by elders in some in-group domains, e.g., visits to relatives, funerals, conflict resolution. The younger generation, often born in mixed households, while not having a good proficiency in the full-fledged language retains a good passive knowledge.

- (iv)

- Dialect: An Italo-Romance variety based on the dialects of northern Italy with the integration of a few Romani lexical elements. It is spoken by groups of Sinti, who seem to have abandoned the use of an Indic-inflected variety of Romani, e.g., Sinti Emiliani and Veneti. Its form doesn’t correspond to the local dialects spoken by the majority society.

2.3. The Jargon of Travellers, ‘il Dritto’

Called Dritto by its speakers, the jargon of Travellers can be considerate one of the most extensive and ancient jargons spoken in Italy. It is a continuation of the Italian historical slang, commonly known as ‘Furbesco’, which has been spoken by Travellers, thieves, tradesmen, and showmen for many centuries. Some of the most ancient collections of lexical items attesting the presence of such a special vocabulary date back to the beginning of the Modern Age. The “Speculum Cerretanorum” by Pini (1484–1486) and the “Nuovo modo de intendere la lingua zerga” (1531), attributed to Brocardo, both included in Camporesi (1973), are two of the most remarkable examples of such historical collections. In contemporary times, the article published by Menarini (1959) is one of the most exhaustive sources which deal specifically with the jargon of the Travellers and offers an incisive socio-economic portrait thereof.

According to the available sources, Dritto is formed by the insertion of a variable corpus of lexical items into the grammatical frame of the co-territorial language. It doesn’t consist in a rigid set of lexical items, but rather of an open, fluid, mobile reservoir of lexical resources. Referring to various jargons spoken in Italy4 Sanga (1993, p. 160) comes to the conclusion that about 80% of the vocabulary is shared among the in-group registers and is mutually intelligible. Moreover, probably as a consequence of centuries of trade, movements, and contacts among marginalized service-provider communities, the vocabulary of old Furbesco is partially shared with other European jargons as well, such as with French Argot, Spanish Germanía, British Cant, and German Rotwelsch (Sanga 1993, p. 158).

Nowadays, the circus and the funfair are the few environments in which the vocabulary of Furbesco retains a significant vitality. The data available are not systematic enough to give an overview of the current extent and geographical diffusion of Dritto in the country. However, it is clear that its vocabulary is spread in different combinations and to various extents among circus and funfair Travellers from different Italian regions. The expressive range of the vocabulary is not very extensive. The reservoir is limited to a few particular communicative domains which are, nevertheless, very prolific. Typically stemming from the jargon formation is the tendency to continuously redefine a specific set of words, considered sensitive, and to work only on pre-existing materials, on what is “already given” (Lurati 1989, p. 11). Among the most productive semantic domains we can mention those referring to human beings and their hierarchical relations (the man, the settled, the policeman, the prostitute, the child, the son, the old man, the workers, the owner); expressions related to the human functions and activities (eating, drinking, sleeping, copulating, speaking, crying); words referring to physical or emotional states (to be ashamed, afraid, ill, drunk, dead); socially interdicted notions and actions (stool, butt, penis, vagina, breast, gun, prison, money, to steal, to kill, to beat, to cheat).

The lexical pool of Dritto is mainly composed by Italo-Romance lexicon. Along with this it is consistent the presence of Romani, which is pointed out by Menarini (1959, p. 474) as one of the most extensive and constant exogenous lexical resources, the result of an intense and prolonged cohabitation of Sinti and Dritti along the same routes. In fact, Romani elements have always been documented in the corpora of Italian historical jargon. Among the analyses on the subject, it is possible to mention the study of Ugo Pellis on the Guardiagrele jargon (1936), the list published by Pasquali (1936) for the Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, “Romaní words in Italian slangs”, Wagner’s (1936) contribution published on Vox Romanica and the study carried out by Tagliavini and Menarini (1938) about the ‘Gypsy’ terms found in the Bolognese criminal jargon. Based on these and other works (Cortelazzo 1975; Piasere 1986; Scala 2004, 2006, 2014) it is clear that the number of Romani words in the historical lexical collections is in most of the cases marginal5 in relation to the overall number of jargon terms. Nevertheless, a rather different situation has recently been documented by researchers among the travelling showmen in northern Italy (Giudici 2011–2012; Scala 2016a, 2016b, 2019; Tribulato 2020), where jargon seems to have embarked a new process of lexical borrowing, which we will discussed in this paper.

3. Methods and Materials

The sociolinguistic data presented in the article were collected by me as part of a broader PhD research project in Cultural Anthropology, focusing on the adaptation strategies of Sinti Travellers within the marginal economic niche of the Italian show business. A multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork has been conducted between 2015 and 2018, for a total of approximately 16 months.

During this period, I followed two different families on their trade fair itineraries in northern Italy. However, the phenomena described here relate specifically to the regions of northeast (Veneto, Friuli and Emilia Romagna), where most of the linguistic material has been gathered. The data set is composed by a heterogeneous group of materials collected with different methods. In particular, of great importance were the fieldnotes, based on a long and intensive participant observation. It is here worth remembering that the jargon examined is perceived as a ‘secret code’ and its use is triggered by some specifical communicative contexts (that we will explore in Section 4.4) which cannot be recreated artificially. It is thus almost impossible to record. Through the active engagement in the social life of the community and in the economic activities carried out by the families of Travellers instead, I have been able to document the communicative behaviors across a wide range of settings and context of interactions, such as the family network, the age cohort, the public spaces and the working activities inside and outside the fairground.

The materials collected contributed to the design of a word list that was used as initial reference point for narrative interviews to the jargon users. These were conducted with 19 respondents, including 7 young adults (15–35), 7 middle-aged adults (35–55) and 5 elderly people (55–75).

The interviews helped to gather elicited data as well as to collect meta-discourse on language which nicely show the emic projections on the discussed language changes and the language ideologies underlying them. Topics for discussion include the role and status of the varieties spoken in the community, the changes that these are experiencing, the reflection on group-internal boundaries, the process of language socialization etc.

4. Results

4.1. Dritto in Change

In comparison to the apport of Romani found in the historical corpora discussed above, my observation on language practices highlights a process of lexical substitution considerably more significant. This appears to be geographically localized in northern Italy, where the presence of Sinti engaged in the travelling show business is numerically significant. In these areas Dritto has adopted a large number of lexical items from the Romani language, which have often complemented or in some cases replaced the traditional vocabulary.

The Dritti interviewed during my field research reported a significant shift in the vocabulary used over the timespan of a few generations. Thus, the phenomenon that is relatively recent seems to have little impact on the elderly, who continue to use just few Romani-derived terms incorporated—perhaps centuries ago—into the jargon of Travellers. A woman of Dritto descent who is now married to a Sinto man observed during an interview on jargon collected in the funfair of Bologna (Emilia Romagna):

My mother used to speak Dritto, she didn’t know what Sinto was. Today Dritto doesn’t exist anymore, it’s mostly spoken by very old people, but there are few very old Dritti Travellers. Most of them are dead and their sons and daughters are married to Sinti. That tradition is now lost. Now my daughters know both languages, but they usually use more Sinti words.(Extract 1—Dritto woman, 48 y.o., Bologna 2016)

This extract remarks a change in the attitude toward the language from the Dritto to the Romani-derived vocabulary which occurred over three generations. Moreover, it delineates the jargon shift as one of the direct results of a changing social context and marriage pattern. According to the consultant Dritto is indeed disappearing because the Dritti Travellers and their so-called ‘traditions’ are disappearing due to the increase in mixed marriages. As confirmed by the data collected, traditional vocabulary is in many cases familiar to the new generations, but rarely actively used by young speakers, who often belittle it as ‘Italian’ (as it is too transparent for the majority society). The discussions on its disappearance are often carried out in terms of ‘loss’, or alternatively of ‘heritage’, ‘tradition’, ‘memory’: “Do you remember when we used to say fangosa [shoe]? When we used to say carbona? [trailer]”, “My mother used to say: come here, I have to check if you’ve got the sgualdi [lice]”. The linguistic customs of the past are often conducted with a mixture of both irony and nostalgia. On the one hand, the outdated vocabulary is considered old-fashioned, bizarre and funny to remember; while on the other, it conveys the idea of a golden age associated with an indefinite past when the in-code was still secret, alive, and not contaminated by the Romani insertions.

These two dimensions can be clearly seen in the framework of the Facebook page called ‘Il Dritto DOCG’ opened in 2008 by a number of Travellers with the aim of collecting linguistic material in Dritto. The page contains two lists: one for lexical items in Dritto and the other for full sentences ‘Gergo del Dritto applicato’ (lit. Dritto’s applied jargon). In the years since the launch of the page, the lists have been frequently updated and the reflection on jargon has been the core of the online community. Before being included in the list, the terms have been suggested, discussed, commented by the members who were motivated to contribute by the administrators. The criteria adopted to select or reject the jargon vocabulary reveal a desire to preserve the traditional lexical items from the influence of the Romani-derived vocabulary. All the Romani loanwords are, indeed, explicitly excluded from the wordlist and in some cases the items in Dritto are matched on the list with the explicit negation of the equivalent from Lombard Sinti (e.g., contrasto not gagio ‘non-traveller’, pila not lovi ‘money’, proso not cheo ‘butt’, sambusa not cistil or sor ‘shut up’, sgrancire not ciordare ‘to steal’, smiciare not dichelare ‘to look’). Moreover, the set of comments provide an insight into the attitude of the community members towards the Dritto vocabulary. The Dritto words are treated as a legacy of the past that they explicitly intend to preserve for the new generations. The past and the memory are the main protagonists of the entire discourse: posts, pictures, and videos inserted between the language debates give the social portrait of a ‘disappeared’ age, the loss of which many regret. In sum, the analysis of this Facebook page confirms the data collected in the fieldwork, according to which Dritto vocabulary is currently perceived as ‘endangered’ as a result of extensive lexical borrowing from Lombard Sinti to a degree that it needs to be rescued by the community. Moreover, its preservation is an integral part of a collective narrative that looks suspiciously to the socio-economic changes that shook the funfair environment in the last decades (e.g., the crisis in the economic sector, the decentralisation of amusement parks in the suburbs, the strict regulations for installing), mostly attributed to the presence of the Sinti families. These are often accused of lowering the quality levels of the services provided as well as damaging the image of the category, which is due to them often associated with the ‘Gypsies’.

4.2. Lexical Substitution

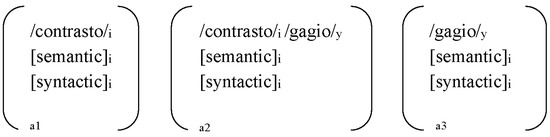

The first step in the process of language renewal towards Romani which is underway in the jargon of Travellers involves the relabelling of old Dritto vocabulary. The process, illustrated in Figure 1, can be described building on the considerations of Lefebvre (2008): Given a lexical entry in Dritto as /contrasto/i (a1) it is assigned a new phonological representation drawn from Romani as /gagio/j (a2), the two forms coexist in parallel, but eventually the original phonological representation will disappear in time (a3).

Figure 1.

Neodritto relabelling model based on Lefebvre (2008).

The result of this process of relabelling is a quite innovative variety (which we will refer to as ‘Neodritto’) composed by a lexical dual system that translates into the possibility to pick between two different lexical reservoirs with different social connotation: ‘Dritto’—the direct continuation of the ancient Furbesco—and ‘Sinto’, meaning a jargon with a Romani lexical basis (not to be confused with the Romani spoken by the Lombard or Piedmontese Sinti) (see also Scala 2016a). Table 1 contains a list of these semantic pairs based on the data collected in the fairgrounds of Veneto and Emilia Romagna. It is here compared the traditional Dritto with the innovative jargon of Travellers, followed by the corresponding source in Lombard Sinti and its translation to English.6

Table 1.

Lexical dual system in Neodritto.

These lexical resources emerge as part of a lexical continuum within which the historical vocabulary of Dritto and Sinto occupy the polar extremes. Speakers are able to actively and passively cover a certain interval of such a continuum. Their ‘common ground’ guarantees mutual comprehension and thus the efficiency of the communicative act. Therefore, each individual has a different repertoire on the basis of social, age, spatial, and regional patterns, and is able to switch his or her speech in order to move more closely towards Dritto or Sinto, or to place him or herself halfway along the continuum.

The following sentences for example have been elicited by a middle-age man of mixed origin (Sinto father and Dritto mother) in the setting of the funfair of Riccione (Emilia-Romagna), where the family participates with a ghost house.10

| (1a) | Hai | pacito | il | contrasto? | ||||

| have.2SG | paid | the | non-traveller_man | |||||

| (1b) | Hai | piscarelato | il | gagio? | ||||

| have.2SG | paid | the | non-traveller_man | |||||

| Have you paid the non-traveller? | ||||||||

| (2a) | Hai | cuccato | la | pila? | ||||

| have.2SG | taken | the | money | |||||

| (2b) | Hai | preso | love? | |||||

| have.2SG | taken | money | ||||||

| Have you earned some money? | ||||||||

| (3) | Fai | cistil! | il | bedo | smiccia | del | loffio | |

| do.2SG | silent | the | policeman | looks | of_the | bad | ||

| Shut up! The policeman is looking at us suspiciously. | ||||||||

| (4) | Dicla | le | fangose | della | gagi! | |||

| Look.2SG | the | shoes | of_the | non-traveller_woman | ||||

| Look at the girl’s shoes! | ||||||||

As it is possible to observe in the ex. 1a–b and 2a–b the semantic and syntactic proprieties of the lexical duplicates fully coincide. The consultant uses these twin sentences precisely to explain how Dritto and Sinto can be used interchangeable to encode the same concept to a different audience or in a different social context. Moreover, they can be also mixed in the same utterance as in the ex. 3 and 4 in order to emphasizes a specific social connotation of a certain word or to evoke a particoular set of values. This find confirm in naturally occurring conversations.

In October 2015 for example, I was working in a foodtruck with A., a Dritto woman in her 50s, who was married (and at the time separated) to a Sinto man. Together with her were working in the foodtruck her son and his Sinto wife. A. made frequent use of jargon to communicate with us about the working activity, as well as to chat with the colleagues outside. She was familiar with both language resources at her disposal and used them as needed to make her communication more effective.

Once, while joking with a friend about her husband, she says:

| (5) | Smiccia, | il | tuo | grimo! |

| Look.2SG | the | your | old man | |

| Look, your old man! | ||||

The preference of Dritto vocabulary in this sentence seems intended to reinforce a link with the friend with whom A. is talking to, underlining their common Dritto origin. Furthermore, the use of the old-fashioned term grimo adds a comic effect to the final implication (your husband/old man).

A few days later A. composed a similar utterance using the Sinto vocabulary while referring to an old Sinto man who arrived to the fairground.

This time she states:

| (6) | Dichela | chi | è | arrivato, | il | puro! |

| Look.2SG | who | is | arrived | the | old man | |

| Look who has arrived, the old man! | ||||||

In the second case the use of Sinto vocabulary seems to be more suitable for the target (young people with Sinti affiliations) as well as to the subject the sentence refers to. Moreover, the use of the term puro besides indicating the person’s age, triggers an association with the values associated by Sinti with seniority, i.e., leadership, morality, honour.

The use of one specific lexical set visibly marks the utterance and is not accidental but can be analysed as “integrated components of a process of social production of meaning and action” (Goodwin 2000, p. 1490). Each term carries a different ideological background and evokes specific feelings, memories and social meanings in the conversation. Moreover, the choice between two different resources can be used to mark the proximity or the distance, and to activate or deactivate different solidarity networks. Most of the times the Travellers are aware of the origin of the lexical items they use and they claim to pick the terms intentionally. Only in a few cases are the Romani-derived forms so integrated into the Italian pattern as to be unrecognizable or, on the contrary, the Dritto items are interpreted as Romani-derived. This is described by Scala (2019, p. 280) as the ‘grey zone’, i.e., the point where the two lexical resources intersect and overlap in the perception of the speakers, who are not able anymore to recognize them as one or the other.

4.3. Lexical Expansion

Alongside the set of Romani-derived words which are well integrated into the jargon in substitution of pre-existing concepts, a larger number of words and expressions are occasionally integrated in daily conversations. It appears that these expressions do not constitute a well-defined corpus of stabilised and processed terms yet. Rather, they may be considered temporary, aim-specific loans, whose usage is supported by mutual intelligibility. In fact, the passive knowledge of the Romani vocabulary allows the speakers to include in their speech performance Romani words or expressions in different proportion depending on the context and the communicative need. The intensity of use of Romani lexical items marks the communicative performance to different degrees. For example, the use of a large number of Romani words by the Travellers would mark the communicative performance to a greater extent and, to quote Matras (2010, p. 129) help to give a specific ‘flavour’ to the conversations (Section 5 for more details).

These spontaneous insertions are neither consistent in the choice of the elements, nor in their form since they can retain some aspects of Romani morphosyntax as we can see in ex. 7.

According to the consultants, temporary loans are used to express new notions, by which the communicative potential of the jargon is increased. The newly adopted words sometimes translate cultural concepts which were introduced by the Sinti families into the funfair environment. I find emblematic in this respect some instults and interjections relating to the domain of death, e.g., calamúle, ‘dead eater’ calamúrdari ‘dead body eater’, calamás ‘flesh eater’, mar múle ‘my deads’, or to the field of shame, as baro coa or baro lac’ ‘big shame’. Otherwise, the new terms often belong to semantic groups which include, for example, words referring to the family network, the social system, the human body, emotions, nature, etc. The speakers say that these terms are often uttered without paying too much attention to the form, but with the sole condition of maintaining the sounds close enough to the original Sinti word to transmit the message correctly. Based on the competence of the speaker, every locution at this stage may appear and sound different from the previous one, up to a point of crystallisation, where one or more linguistic forms are stabilised.

The description of such processes often highlights how the instantaneousness of expressions used in daily conversations represents the crucial engine of linguistic innovativeness. Contingency is recognised by the speakers as a key characteristic of the jargon, which plays a fundamental role in its development. The incorporation of Romani lexicon into the jargon is increasingly consistent in the new generations that is often born in mixed households. The Romani-derived elements used in this dynamic way are often not yet perceived as jargon, and because of their unstable nature it is difficult to classify them.

In 2013, Scala collected a number of utterances that show the pervasiveness that Sinto vocabulary can have on some speakers. Some of these sentences from the same Dritto consultant are included here for illustrative purposes, for an extensive analysis see Scala (2016a, p. 54):

| (7) |

|

As the examples (7) show, the insertion can affect the utterances of the same speaker in different proportions. Sometimes only one Romani-derived term is inserted (a; b), other times almost the whole sentence is Romani-based (c). The lexical items are often linguistically accommodated to Italian (d; e), while in other cases the Romani morphological structure is maintained or even the whole Romani sentence is acquired (f; g). The substitution does not only concern the terms traditionally encoded in jargon but can be applied to each element of a statement.

4.4. Neodritto in Use

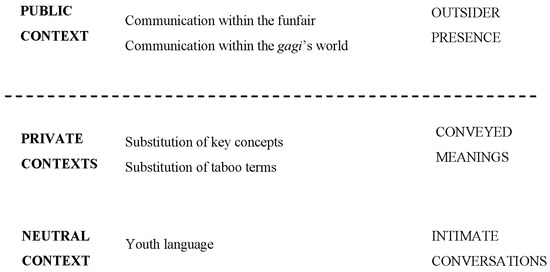

Despite the ongoing process of relexification and expansion, and as illustrated in the Figure 2, most of the communicative functions of the jargon of Travellers have remained consistent with the earlier literature (Menarini 1959) and with the distinctive usages of the special languages (Trumper 2011). The jargon is learned as a secondary vocabulary and used both as a secret device of communication as well as to flag identification and solidarity among members of the community. These two aspects, secrecy and intimacy, are strictly related to each other, continuously interplaying. If, indeed, the exclusion of the outsiders is a fundamental component of jargon behavior, it is possible to consider it not just practical but also ideological (Sanga 2014; Scala 2016a), used to reinforce the exclusivity of the in-group communication.

Figure 2.

Contexts of use of Neodritto.

The most common social context for the use of Neodritto is the public space. In this setting, the trigger for the use of this special vocabulary is the physical or psychological presence of settled people and the need of creating a private and confidential exclusivity space. The fairground is, thus, the first social arena where the jargon is utilized and maybe the most representative. The Travellers use the in-code to exchange information about the ride, to warn each other about dangerous or suspicious situations, or simply to interact and exchange jokes from their working posts, undetected by the customers. All these situations are explicitly bystander-oriented and claimed as secretive by the speakers (see also Rijkhoff 1998). Although jargon is mainly used among gagi, the messages conveyed are often in-offensive and not directly related to them. The code seems used within the fairground’s context to symbolically and emotionally mark the Travellers’ space within this shared context, by stressing a linguistic and cultural distance among traders and customers as well as among the Travellers and the settled (see also Matras 2010, p. 173; Rieder 2018, p. 120). The invisible net constructed by these linguistic acts connects speaker to speaker inside the fairground and sometimes also outside, when Travellers are together in other public spaces such as in shops, bars or restaurants. In both these contexts, the use of the internal code is often characterised by a fast speech performance and by an intensive use of jargon-specific lexical items within short, incisive sentences, that make the locutory act semantically cryptic for the bystanders.

Along with bystander-oriented usages, there are also private usages of the code marked by a less intensive replacement of lexical items which are, however, strongly emphasized by the speakers in the body of the discourse. In these situations, jargon is used to convey some culture-specific concepts, addressing the internal system of values and attitudes (Matras 2010) whose translation into the majority language is challenging for some reason. These are emic definitions (e.g., dritto ‘traveller’, gagio ‘non-traveller’, raclo ‘support worker’), concepts regarding the working sphere (e.g., mestiere ‘funfair ride’, piazza ‘fairground’, impiantare ‘to build the ride’, spiantare ‘to dimantle the ride’), the shared values (e.g., lac’ ‘shame’, víes ‘bad’, sucar, misto ‘good’) or the taboo concepts (e.g., lumli ‘prostitute’, starape ‘jail’, minc’ ‘vagina’). This last category includes words referring to concepts and behaviour that should not be discussed in public, either because considered vulgar, intimate, or sensitive for some reason. The, so-called ‘euphemistic quality’ of jargon (Burridge and Keith 1998) allows speakers to avoid the public sanction while, on the other hand, adds an intimate dimension to the communication.

Alongside these functions that are also common among other special languages, there is another context of use which especially merits attention. It appears to be linked directly with the process of continuous lexical loans from Lombard Sinti, which are used within the Italian grammatical framework in the speech of the youth. Unlike the other uses, in this specific circumstance the special vocabulary of Neodritto is adopted regardless of the social setting to express a bond between peers. The phenomenon, observed by Scala (2016a) in some groups of circus showmen, is evident also within the world of the funfair, where it seems particularly common among the children of mixed families (Dritti-Sinti), i.e., those who have inherited both a strong attitude towards jargon and a good passive knowledge of the Romani vocabulary. This, so-called by the speakers ‘broken’ usage has the advantage of being horizontal, i.e., it unites youth from every family background. Romani speakers usually have an overwhelmingly negative attitude towards such a language usage and accuse the Dritti Travellers of misusing the Romani vocabulary.

Nowadays the jargon ‘giostrivendolo’11 is very popular, half Dritto and Sinto. I always say to my children «speak in Italian and do not feel uncomfortable». I don’t want my children to speak such a broken dialect mixed with the funfair jargon, which is full of vulgarities. Better nothing. This doesn’t mean to be picky, it is just stressing a vulgar usage of the language. I have never loved the jargon. Dritto has downgraded the Sinti language and I don’t like it. When we get together I want the best of you and you should take the best of me (although we need to figure out what the best is).(Extract 2—Sinto man, 52 y.o., Lignano Sabbiadoro 2016)

The main objections of the Sinti people towards such linguistic usage include, among others, the use of obscene language, the code-mixing with multiple linguistic codes, the grammatical inaccuracies and errors, and the use in public contexts. Sinti claim that Romani should only be spoken by those who are capable of using it in its full form (i.e., the elders) and in the appropriate and respectful social circumstances.

5. Discussion

To address the dynamics underlying this phenomenon of lexical renewal, it is important to note Lombard Sinti’s reputation in terms of internal code of communication. A consultant has defined Dritto compared to Romani as “what Italian is compared to Latin”. Another has defined Dritto as “a dialect of Lombard Sinti”. In both these assertions, the recognition of a linguistic superiority of Romani is clear as well as the perception of an intimate connection between it and the jargon vocabulary. Romani and Dritto are often perceived by speakers as two different but closely related languages, which are united by a similar opposing orientation toward the dominant society. Indeed, the Romani language shares its anti-language status with the jargon, just as Romani people share a dualistic perspective with other peripatetic communities based on the internal/external subdivision of the world.

Three functional and structural features of Romani are often pointed out by the jargon speakers in order to underline its high status as compared to the Dritto vocabulary. The first characteristic is its semantic obscurity. The terms of the historical Dritto, already partially comprehensible from the outside when inserted in an Italian grammatical context, have been further weakened, over time, by their partial incorporation into a variety of the majority language. In comparison, the loanwords from the Romani variety spoken by Lombard Sinti are perceived as more ‘obscure’, and therefore more functional to an exclusive communication.

Since when you use a Dritto word in a sentence it is possible to partially understand the meaning, we sometimes replace it with a word in Sinto, which is more difficult. Being here [in the social context of funfair] everyone knows certain expressions.(Extract 3—Dritto man, 38 y.o., Treviso 2016)

The second prestigious element is the perception of Romani as a full-fledged language, including a complete grammatical system and a vast vocabulary that enables extended communication. Compared to it, the number of concepts that can be expressed in Dritto while not being understood by the gagi is substantially limited.

Their language is real because you can say anything. In Sinto I can understand only those three or four words that help me get the meaning of the speech. Circolante12 or Dritto, on the other hand, have only a few words. The Sinti, when they hear us talking like this, they laugh because they say it’s a made-up language.(Extract 4—Dritto man, 41 y.o., Lignano Sabbiadoro 2016)

The third and last factor of linguistic prestige, as evident from extract 4, concerns its status as a ‘historical’ and documented language compared to Dritto which is, on the other hand, considered artificially constructed. For all these reasons, Lombard Sinti is considered an ideal lexical source for the renewal of the jargon.

But can we consider the linguistic prestige sufficient to explain the massive transformations ongoing over the last generations? According to recent studies (Sairio and Palander-Collin 2012), the phenomena of language change or language accommodation to other people’s communicative behaviour are often triggered by the dynamics of social prestige. The latter, as we know, is not a stable attribute and can be lost or acquired over time. In recent years the carnival has undergone rapid social changes that led to a renewal of internal hierarchies within the community. I consider it crucial to examine the renewal of the jargon in connection with the socioeconomic scenario within which it develops, reconstructed together with my consultants. Specifically, in order to have an insight into the dynamics of language variation and change, it is important to reconstruct the power and prestige relations that have elapsed over time between Sinti and Dritti travelling entertainers.

These two peripatetic groups co-existed in the same environment for a long period of time. Socially isolated in specific service-providing niches, they were exposed to mutual linguistic influences, until a certain level of mutual-comprehension was achieved. The Italian Travellers had a good passive knowledge of the Romani variety spoken by Sinti and the Sinti learned to use some Dritto words13. At this stage Dritti and Sinti travelling entertainers were employing distinct strategies to approach the same economic world. While the former occupied the important squares in the city centres, making big investments to buy expensive rides, the latter used to attend the village fairs with small attractions (e.g., targets, carousels, chain rides), using the funfair to live up to their aspirations. At that time, the access to the best fairground was very exclusive, reserved to the families of Travellers best integrated and known in the carnival business. The fairgrounds in large cities were, in fact, run by a committee that used to personally choose the families and trades that could participate at the fairground. With some exceptions, the two groups performed the same job and interacted with each other while, on the other hand, they continued to maintain the boundaries between them.

At the end of the 1960s, the situation changed radically. Act n. 337 of 1968, on the regulation of travelling entertainment, forced local administrations to find specific locations for hosting annual funfairs and transferred the management of those to public bodies. Encouraged by the new law and the economic boom of the time, many other Sinti families entered the funfair world, while those who were already part of it started to penetrate the major fairgrounds. This is often described by the Travellers as a period of ‘levelling’. The Sinti Travellers improved their social and economic status within the travelling show business and began to pose a threat to the economic activities run by Dritti Travellers. The new setting of close cohabitation and competition increased the contacts between the two communities and raised the number of intermarriages, which led to the formation of a rather new mixed community.

Perhaps as a result of these mixed unions, or due to the need for invisibility that the Sinti felt in relation to their new economic position, inflected Romani starts to recede at this stage. The language stopped being the variety of first socialization and was abandoned in the family context, where it has been replaced by Italian. Having lost its role in daily interactions, inflected Romani maintained a symbolic, age-bound relevance in specific socially ritualized areas such as funerals, visits to relatives, mediation processes, storytelling and so on. In this setting, Lombard Sinti continues to be used to mark the family adherence to specific norms of behaviour. The younger generation, often composed of children of mixed families, is excluded from its use as a ‘ritual’ code (prerogative of the elders), but as mentioned still retains a very extensive passive knowledge of its vocabulary, that is often used in the conversations within the age cohort. This age-bound use seems, however, less extensive in the families where Romani is stronger or better transmitted to new generations.

While fluency in Romani was diminishing, its influence on the composition of the jargon of Travellers became more substantial. In accordance with Sairio and Palander-Collin (2012, p. 626), the fascination towards the language grows in parallel with the growing prestige of its speakers. Towards the Sinti Travellers, the Dritti Travellers express, indeed, a contradictory attitude, ranging from obstinate aversion to hidden admiration. The prestige of both the Sinti and their language is often publicly denied but not less effective. The Sinti model is socially stronger: the community is based on an effective system of internal solidarity which benefits from their permeating values. The network of family ties makes them economically more competitive, as well as more fearsome. The younger generations, even when coming from a different background, want to recognize themselves alongside that moral, aesthetic, political and economic model. From the interviews it appears that the Sinto terms are considered by the younger generations as ‘stronger’, ‘more incisive’, ‘more effective’. In comparison, the Dritto vocabulary, as well as the cultural model it represents, is considered inadequate and old-fashioned, further weakened by the partial exposure to outsiders of its group-internal lexicon. Television, movies, the role played by public schools in terms of social cohesion, and the assiduous presence of Travellers in some specific towns famous for their production of carousels or caravans, led to a partial spread of the Dritto vocabulary as it began to enter regional varieties of Italian and youth local slangs. More and more terms from Lombard Sinti were gradually acquired to replace this ‘worn-out’ vocabulary.

6. Conclusions

To summarize, it is possible to observe two different, but closely related, sociolinguistic phenomena. On the one hand, there is a weakening of the traditional Dritto vocabulary and the decreasing competence in inflected Romani among Sinti Travellers. On the other hand, my research reports a massive incorporation of Romani terms into the jargon of travellers and the rebirth of Romani vocabulary and expressions in youth speech. These phenomena are largely intertwined and suggests an extensive renegotiation of the identity of the travelling showbusiness community as a result of the examined changes in the socio-economic configuration of the ecological niche. Fundamental in triggering the phenomenon of relexification seems the mixed marriages, the redefinition of the in-group relations of power and the new prestige status acquired by the Sinti Travellers within the community. The case study examined clearly shows the profound correlation between social and linguistic changes, underlining the extreme regenerative capacity of special vocabularies, whose lexical reservoir is continually remodelled and extended to adapt to the evolving needs of the community. At the center of this creative dynamic of manipulation is the speaker, which daily use of lexical resources constitutes, to quote LePage and Tabouret-Keller (1985), an aware act of identity and agency.

The scenario discussed opens up the studies on relexification to a new field of dynamics as extensive as unexplored, which could explain the formation of other Romani-based special vocabularies. Furthermore, it illustrates a possible process of genesis of a Para-Romani variety, i.e., a speech variety formed by the inclusion of Romani lexicon into the grammatical frames of the language spoken by the non-Roma population (for a comprehensive overview refer to Bakker 2020). It is, in fact, difficult to predict whether or not the use of this relexified and expanded Romani-based jargon by younger generations born into mixed households will lead over time to a stable variety, which could replace the use of Romani. At the moment many indicators point in this direction. Discussing this possible outcome is beyond the scope of this article, but what we can certainly observe is how the relexification of the jargon of Travellers targeting Romani (resulting in Neodritto) and the emergence of a mixed language whose domains and areas of use are extended (the youth speech) are intermediate possibilities of an identical process of contact. There is no point in trying to separate these new varieties, which are part of the same continuum of structures (Matras 1998, p. 23), just as there would be no point in trying to separate their speakers. The linguistic intermingling is, in fact, only the most visible effect of the formation of an in-between community that shares lifestyles, rules, attitudes and material culture, a prolific context for linguistic and cultural exchanges. The internal and external boundaries of this unique and at the same time heterogeneous community are, through the use of a special lexicon, set, readjusted and defended. It is to these that we should therefore turn our attention in order to better understand such processes of linguistic change in their dynamic development and mutual implications.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The availability of this data is restricted for reasons of confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Yaron Matras, Zuzana Bodnarova, Jakob Wiedner and Evangelia Adamou for their valuable suggestions on a previous version of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Dritto (m.sg.), Dritta (f.sg.), Dritti (pl.) |

| 2 | The Lombard Sinti, the Emilian Sinti, the Venetian Sinti, the Piedmontese Sinti, the Sinti from Marche (region at the central east of Italy) and the Estraixaria Sinti are among the more active groups in the Italian funfair. |

| 3 | In this paper the term gagio (m.sg.), gagi (f.sg.), gagi (pl.) is used to refer to the people whose bloodline does not belong to the world of travel, this is in accordance with the use made of it by the speakers in the funfair environment. |

| 4 | The estimate was made by the author comparing the vocabularies of four Italian non-standard varieties: the Gaì (jargon of the shepherds of Bergamo), the Rungin (jargon of the coppersmiths of Val Cavargna), the Ammâscânte (jargon of the coppersmiths of Dipignano) and the jargon of the rope makers of Castelponzone. |

| 5 | An exception to this is the case of the Guardiagrele jargon of the horse traders, which contains a considerable number of terms from the Romani of Abruzzo (Giammarco 1964; Scala 2014). |

| 6 | It is important here to notice how some terms in Lombard Sinti have undergone a semantic shift when adopted by Neodritto, e.g., (36) bédo ‘thing’> ‘policeman’; (35) gavaló ‘villager’ e ráklo ‘gagio boy’> ‘support worker’; (23) gózaro ‘clever’> ‘evil’ etc. |

| 7 | The Italian spelling will be used in this paper for the transcription of ‘Sinto’ (i.e., the vocabulary of Romani origin integrated in Neodritto). The phoneme /ʧ/ in word-final position will be transcripted as -c’ and the phoneme /h/ in word-intial position as -h. This is in accordance to the ‘Sistema di trascrizione semplificato secondo la grafia italiana’ (Sanga 1977). |

| 8 | The word ‘diero’ is a flexible term that acquires meaning according to the context. It is not attested in any of the Romani dictionaries used for the composition of the Dictionary of Gypsy Languages Spoken in Italy (Soravia and Fochi 1995) but it appears in some Romani extracts in Tauber (2006) and is perceived by the speakers as Romani-derived. |

| 9 | In Neodritto cistil < če stil ‘shut up’ the verb-adjective structure is often ignored and the expression is used as a noun to translate ‘silence’ (cf. Scala 2016b), e.g., fai cistil! (ex. 3). |

| 10 | In the examples the italics is used to mark the words in Dritto, the bold italics for loans from Lombard Sinti and the regular font for Italian. |

| 11 | The term comes from the association of the It. ‘giostra’ (ride) with the suffixoid -vendolo used for words like It. ’fruttivendolo’ (greengrocer). The association creates a pejorative effect. |

| 12 | The term is used in this context to define the jargon used by the circus show people, often called ‘Circolanti’. Their vocabulary, while largely coinciding with the one used by the funfair workers, possesses some specific terms referring to the world of the circus. |

| 13 | A few elderly Sinti still occasionally use Dritto words while speaking about certain subjects in Italian. This is probably the trace of the past independence of the code and the prestigious place of its speakers in the world of travel. |

References

- Bakker, Peter. 2020. Para-Romani Varieties. In The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics. Edited by Yaron Matras and Anton Tenser. Cham: Palgrave Mcmillan, pp. 353–83. [Google Scholar]

- Burridge, Kate, and Allan Keith. 1998. The X-phemistic value of Romani in non-standard speech. In The Romani Element in Non-standard Speech. Edited by Yaron Matras. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, pp. 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- Camporesi, Piero. 1973. Il Libro Dei Vagabondi. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Cortelazzo, Manlio. 1975. Voci zingare nei gerghi padani. Linguistica 15: 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGraff, Michel. 2002. Relexification: A Reevaluation. Anthropological Linguistics 44: 321–414. [Google Scholar]

- Elšík, Viktor, and Michael Beníšek. 2020. Romani Dialectology. In The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics. Edited by Yaron Matras and Anton Tenser. Cham: Palgrave Mcmillan, pp. 389–427. [Google Scholar]

- Giammarco, Ernesto. 1964. I gerghi di mestiere in Abruzzo. Rivista dell’Istituto di Studi Abruzzesi 2: 219–39. [Google Scholar]

- Giudici, Chiara. 2011–2012. Il Gergo dei Circensi: Materiali e Ricerche. Master’s thesis, University of Milan, Milan, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, Charles. 2000. Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 32: 1489–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, Michael A. K. 1976. Anti-languages. American Anthropologist 78: 570–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, Julia, and Paul Wexler. 1997. Relexification in Creole and Non-Creole Languages. With Special Attention to Haitian Creole, Modern Hebrew, Romani and Rumanian. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Claire, and John S. Lumsden. 1989. Les langues creoles et la théorie linguistique. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 34: 249–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, Claire. 1993. The role of relexification and syntactic reanalysis in Haitian Creole: Methodological aspects of a research program. In Africanisms in Afro-American Language Varieties. Edited by Salikoko S. Mufwene. Athens: University of Georgia Press, pp. 254–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Claire. 1997. On the Cognitive Process of Relexification. In Relexification in Creole and Non-Creole Languages. With Special Attention to Haitian Creole, Modern Hebrew, Romani and Rumanian. Edited by Julia Horvath and Paul Wexler. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 72–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Claire. 1998. Creole Genesis and the Acquisition of Grammar: The Case of Haitian Creole. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Claire. 2008. Relabelling: A Major Process in Language Contact. Journal of Language Contact 2: 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePage, Robert, and Andrée Tabouret-Keller. 1985. Acts of Identity. Creole-Based Approaches to Language and Ethnicity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden, John. 1999. Language Acquisition and Creolization. In Language Creation and Language Change: Creolization, Diachrony, and Development. Edited by Michel DeGraff. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 129–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lurati, Ottavio. 1989. I marginali e la loro mentalità attraverso il gergo. La Ricerca Folklorica 19: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matras, Yaron. 1998. Para-Romani revisited. In The Romani Element in Non-Standard Speech. Edited by Yaron Matras. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2002. Romani: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2005. The classification of Romani dialects: A geographic-historical perspective. In General and Applied Romani Linguistics. Edited by Dieter W. Halwachs and Gerd Ambrosch. Muenchen: Lincom, pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Matras, Yaron. 2010. Romani in Britain: The Afterlife of a Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menarini, Alberto. 1959. Il gergo della piazza. In La Piazza. Spettacoli Popolari Italiani Descritti e Illustrati. Edited by Roberto Leydi. Milano: Edizioni del Gallo Grande, pp. 461–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mous, Maarten. 1994. Ma’á or Mbugu. In Mixed Languages. 15 Case Studies in Language Intertwining. Edited by Peter Bakker and Maarten Mous. Dordrecht: IFOTT, pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Mous, Maarten. 2002. Paralexification in language intertwining. In Creolization and Contact. Edited by Norval Smith and Tonjes Veenstra. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 113–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mous, Maarten. 2003. The linguistic proprieties of lexical manipulation and its relevance for Ma’á. In The Mixed Language Debate. Theoretical and Empirical Advances. Edited by Yaron Matras and Peter Bakker. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 209–36. [Google Scholar]

- Muysken, C. Pieter. 1981. Halfway between Quechua and Spanish: The case for relexification. In Historicity and Variation in Creole Studies. Edited by Arnold Highfield and Albert Valdman. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers, pp. 52–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali, Pietro Settimio. 1936. Romaní Words in Italian Slangs. Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society 3: 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Piasere, Leonardo. 1986. Le voci zingare del “Glossario del gergo della malavita veronese di Giovanni Solinas”. Civiltà Veronese 2: 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Piasere, Leonardo. 1992. Considerazioni sulla presenza zingara nel nord Italia nel XIX secolo sulla base di alcuni documenti linguistici. Ce fastu? Rivista della Società Filologica Friulana “Graziadio Ascoli” 2: 233–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rieder, Maria. 2018. Irish Traveller Language. An Ethnographic and Folk-Linguistic Exploration. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rijkhoff, Jan. 1998. Bystander deixis. In The Romani Element in Non-standard Speech. Edited by Yaron Matras. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sairio, Anni, and Minna Palander-Collin. 2012. The reconstruction of prestige patterns in language history. In The Handbook of Historical Sociolinguistics. Edited by Juan Manuel Hernández-Campoy and Juan Camilo Conde-Silvestre. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 626–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sanga, Glauco. 1977. Sistema di Trascrizione Semplificato Secondo la Grafia Italiana. Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia I: 167–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sanga, Glauco. 1993. Gerghi. In Introduzione All’italiano Contemporaneo II. La Variazione e gli Usi. Edited by Alberto Sobrero. Roma-Bari: Laterza, pp. 151–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sanga, Glauco. 2014. La segretezza del gergo. In Studi Linguistici in Onore di Lorenzo Massorbio. Edited by Federica Cugno, Laura Mantovani, Matteo Rivoira and Sabrina Specchia. Torino: Atlante Linguistico Italiano, pp. 885–903. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, Andrea. 2004. L’elemento lessicale zingaro nei gerghi della malavita: Nuove acquisizioni. Quaderni di Semantica 25: 103–27. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, Andrea. 2006. La penetrazione della romaní nei gerghi italiani: Un approccio geolinguistico. In Lo spazio Linguistico Italiano e le “Lingue Esotiche”. Rapporti e Reciproci Influssi. Edited by Emanuele Banfi and Gabriele Iannàccaro. Roma: Bulzoni, pp. 93–503. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, Andrea. 2014. La componente romaní nel baccài di Guardiagrele: Rileggendo le raccolte di Ugo Pellis ed Ernesto Giammarco. In Studi Linguistici in Onore di Lorenzo Massorbio. Edited by Federica Cugno, Laura Mantovani, Matteo Rivoira and Sabrina Specchia. Torino: Istituto dell’Atlante Linguistico Italiano, pp. 909–21. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, Andrea. 2016a. Gerghi storici nell’Italia settentrionale odierna: Il caso di giostrai e circensi. Collectia Argotolog 1: 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, Andrea. 2016b. Cestìl “silenzio, attenzione”, grimagliera “protesi dentaria” e gavalò “aiutante”. Intorno all’origine di tre lessemi del dritto. Rivista Italiana di Dialettologia 40: 223–34. [Google Scholar]

- Scala, Andrea. 2019. Codici storici della marginalità nell’Italia nord-occidentale. In Lingue e Migranti Nell’area Alpina e Subalpina Occidentale. Edited by Michela del Savio, Aline Pons and Matteo Rivoira. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 275–87. [Google Scholar]

- Siewert, Klaus. 1996. Sondersprachenforschung: Rotwelschdialekte. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Soravia, Giulio, and Camillo Fochi. 1995. Vocabolario Sinottico Delle Lingue Zingare Parlate in Italia. Roma: Centro Studi Zingari. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliavini, Carlo, and Alberto Menarini. 1938. Voci zingare nel gergo bolognese. Archivum Romanicum XXII: 242–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tauber, Elisabeth. 2006. Du Wirst Keinen Ehemann Nehmen! Respekt, Fluchtheirat und die Bedeutung der Toten bei den Sinti Estraixaria. Münster: LIT Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Tribulato, Chiara. 2020. Dritto in contatto: Elementi romaní nel gergo di una comunità girovaga italiana. In Argot e Plurilinguismo. Edited by Andrea Scala. Argotica 1: 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tribulato, Chiara. 2019. Qui in Mezzo a Noi. I Sinti Nello Spettacolo Viaggiante. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Padua, Ca’ Foscari of Venice and University of Verona, Padova, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Trumper, John. 2011. Slang and Jargons. In The Romance Languages. Edited by Martin Maiden, John C. Smith and Adam Ledgeway. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Max Leopold. 1936. Übersicht über neuere Veröffentlichungen über italienische Sondersprachen. Vox Romanica 1: 264–317. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann, Henri. 1992. Relexification et Créologenèse. Actes du XV Congès International des Linguistes, 9–14 August. Québec: Presses de l’Université Laval, Available online: http://www.nou-la.org/ling/1994b-relex.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).