The Prosodic Expression of Sarcasm vs. Sincerity by Heritage Speakers of Spanish

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Background on Sarcasm

2.2. Prosodic Manifestations of Sarcasm

2.3. Acquisition of Sarcasm

2.4. Spanish Heritage Speaker Prosody

2.5. Spanish Heritage Speaker Pragmatics

2.6. Sociolinguistic Considerations

2.7. Current Agenda

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Materials

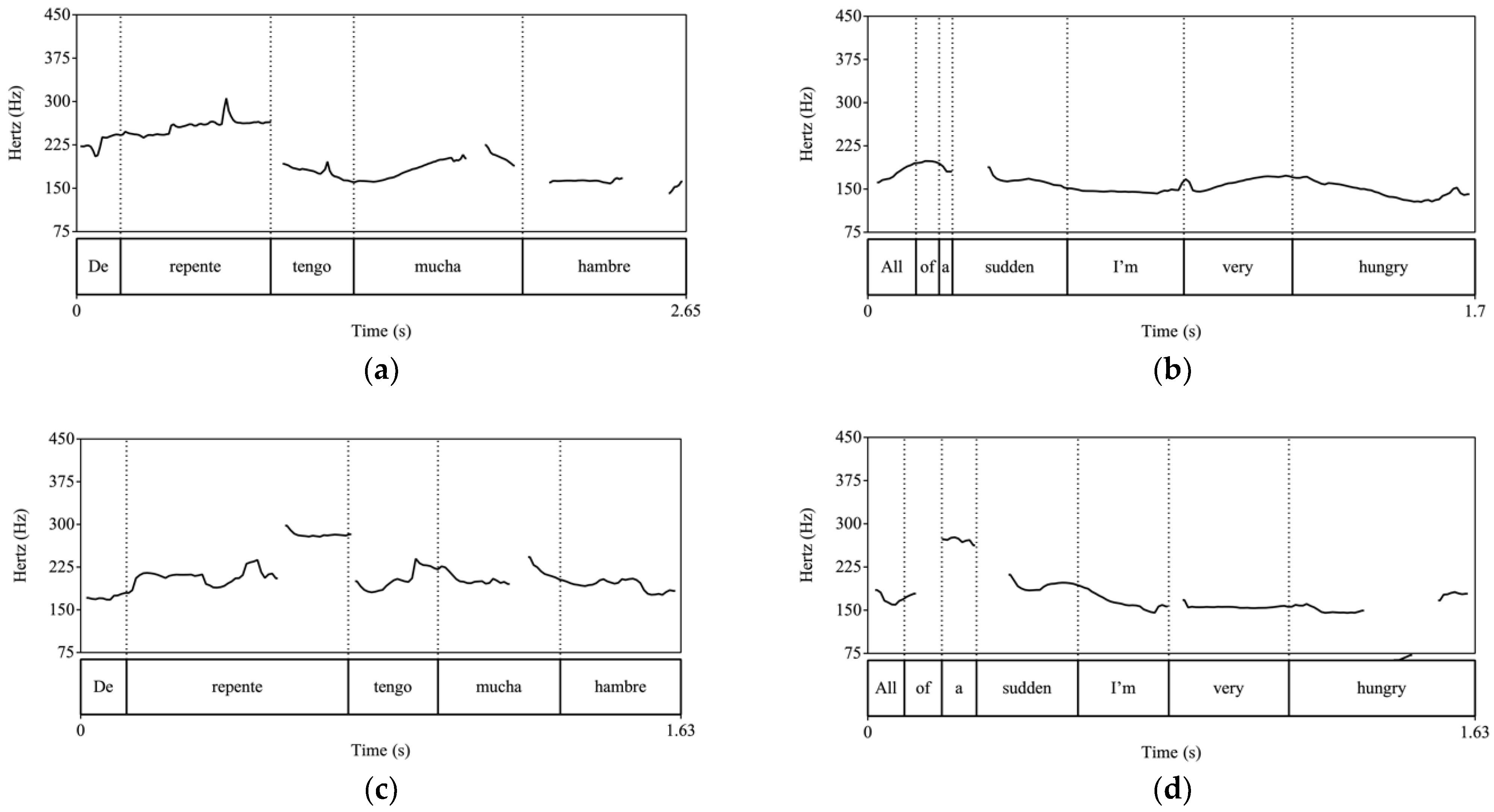

- (1)

- Eliciting sarcasm in EnglishHypothetical context: You’re on an airplane and your friend says, “They’re going to serve us food now.” The food doesn’t smell good, and the flight crew hasn’t treated you well.Scripted response: All of a sudden, I’m very hungry.

- (2)

- Eliciting sincerity in EnglishHypothetical context: You’re on an airplane and your friend says, “They’re going to serve us food now.” The airline has a reputation for serving delicious food.Scripted response: All of a sudden, I’m very hungry.

- (3)

- Eliciting sarcasm in SpanishHypothetical context: En un avión, tu amigo te dice, “Nos van a servir comida.” La comida no huele bien y la tripulación no te ha tratado bien.Scripted response: De repente tengo mucha hambre.

- (4)

- Eliciting sincerity in SpanishHypothetical context: En un avión, tu amigo te dice, “Nos van a servir comida.” La aerolínea tiene una reputación de servir comida rica.Scripted response: De repente tengo mucha hambre.

3.3. Acoustic Analysis

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

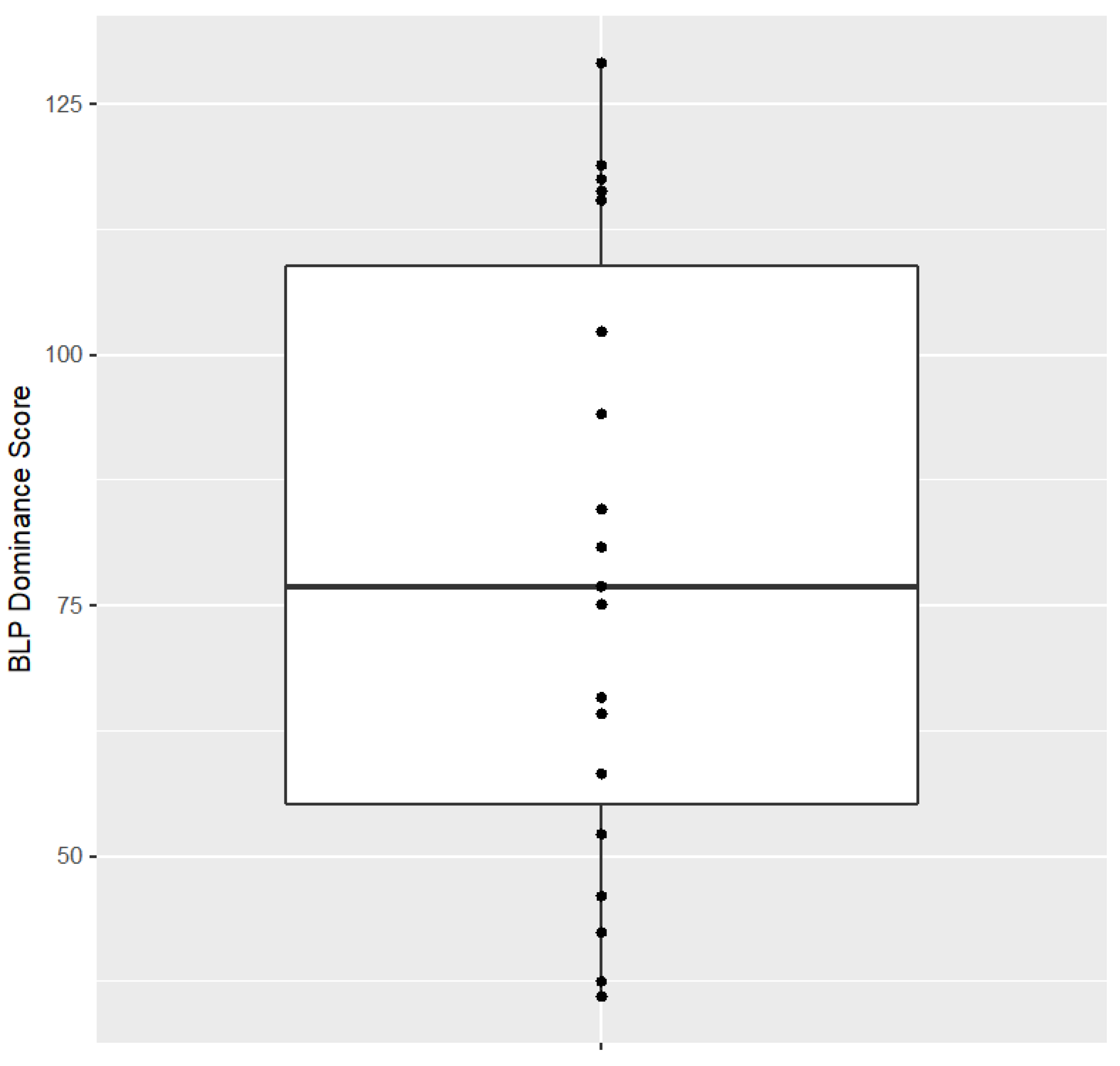

4.1.1. BLP

4.1.2. Acoustic Measures

4.2. Inferential Statistics

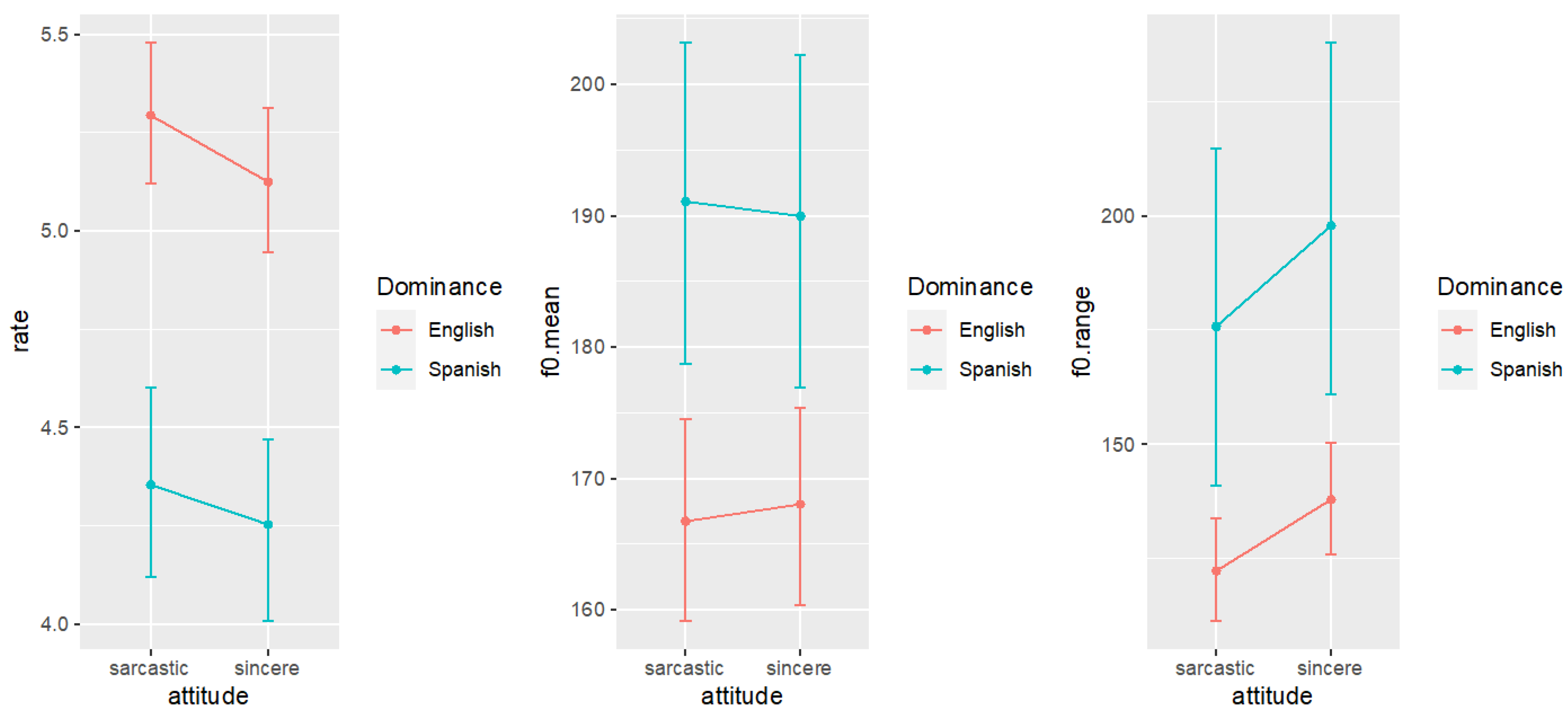

4.2.1. Speech Rate

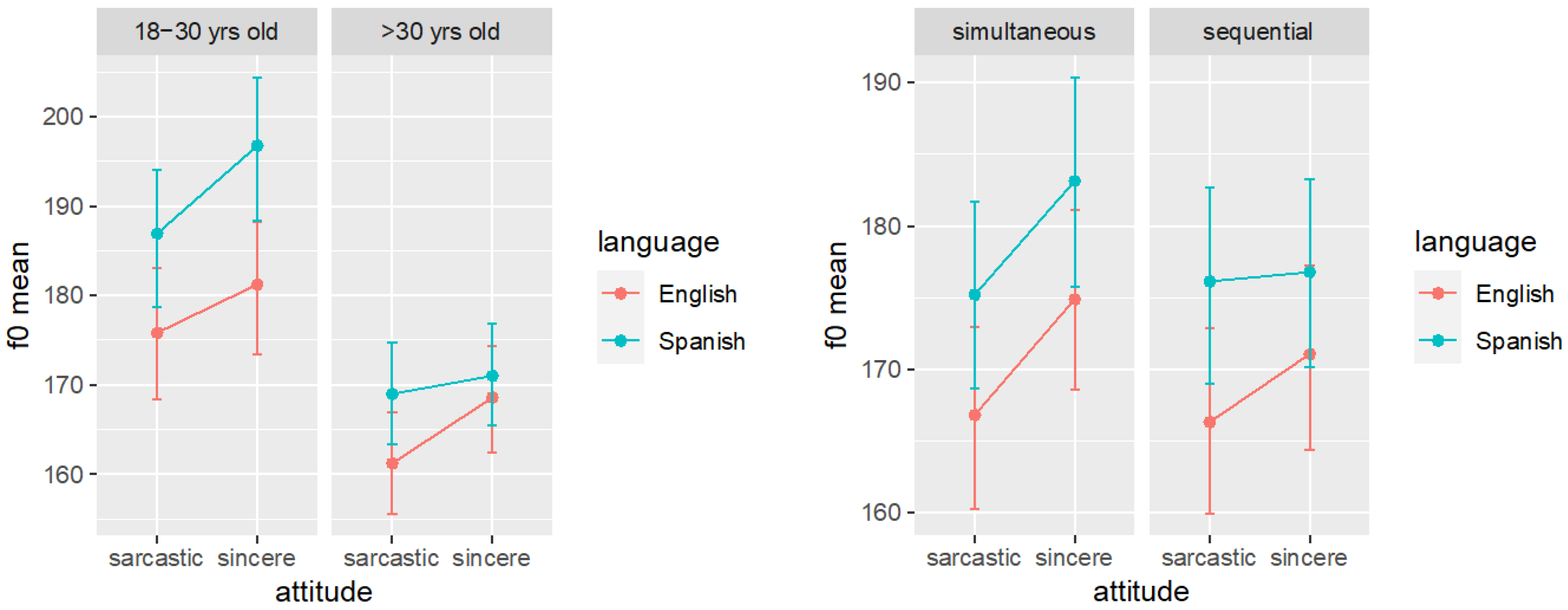

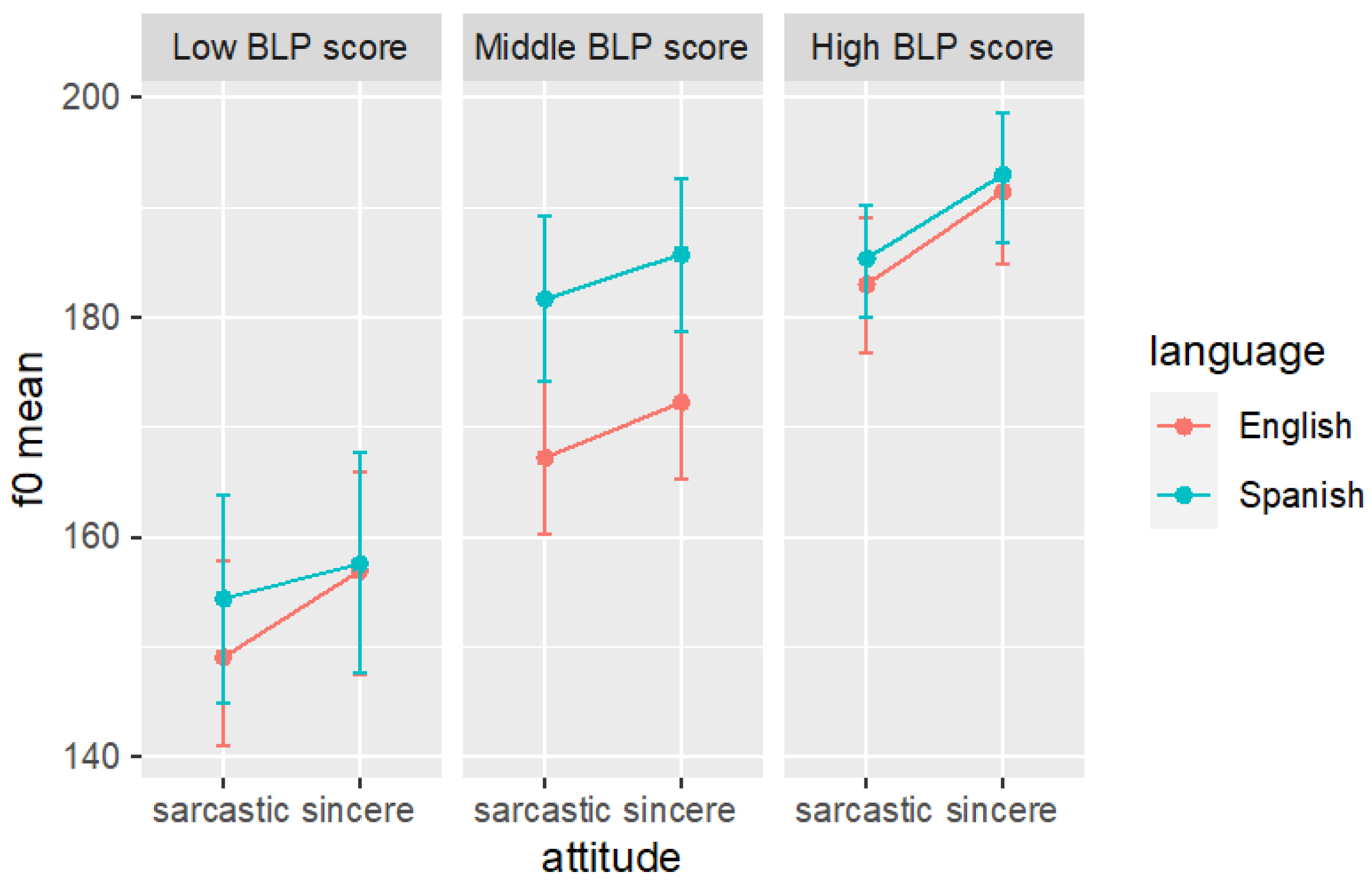

4.2.2. F0 Mean

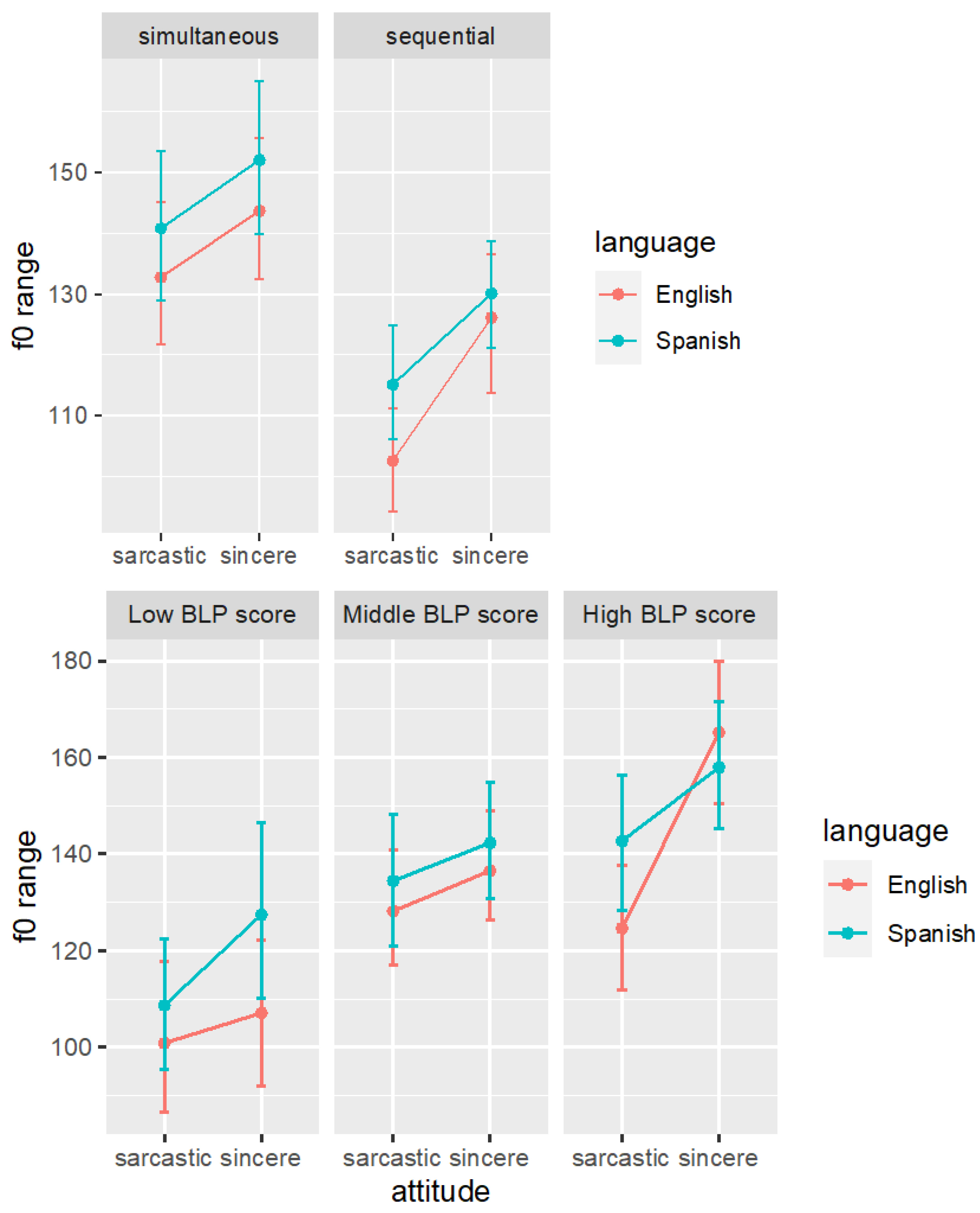

4.2.3. F0 Range

4.2.4. Family Effect

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Participant ID | Age (Age Group) | Gender | Place of Birth | Bilingual Type | BLP Score | English Dominance |

| ENG03 | 23 (18–30) | Female (F) | US | Simultaneous (Sim) | 65.8 | Mid (M) |

| ENG04 | 51 (30+) | F | US | Sequential (Seq) | 52.2 | Low (L) |

| ENG05 | 20 (18–30) | F | US | Sim | 80.8 | M |

| ENG08 * | 50 (30+) | Male (M) | Mexico | Seq | 118.9 | High (H) |

| ENG12 * | 40 (30+) | M | US | Sim | 46 | L |

| ENG13 | 36 (30+) | F | US | Sim | 116.3 | H |

| ENG14 | 35 (30+) | M | US | Sim | 42.4 | L |

| ENG15 | 20 (18–30) | M | US | Sim | 94.1 | M |

| ENG16 | 52 (30+) | M | Mexico | Seq | 102.3 | M |

| ENG17 | 43 (30+) | M | US | Sim | 75.1 | M |

| ENG19 | 23 (18–30) | F | US | Sim | 58.2 | M |

| ENG20 | 40 (30+) | F | US | Seq | 64.2 | M |

| ENG21 * | 18 (18–30) | F | US | Sim | 117.5 | H |

| ENG22 * | 45 (30+) | M | Mexico | Seq | 36 | L |

| ENG23 * | 44 (30+) | F | Mexico | Sim | 129.1 | H |

| ENG24 | 26 (18–30) | F | US | Sim | 84.6 | M |

| ENG25 | 19 (18–30) | F | US | Seq | 37.5 | L |

| ENG26 * | 49 (30+) | F | Mexico | Seq | 76.9 | M |

| ENG27 * | 46 (30+) | F | Mexico | Seq | 115.4 | H |

Appendix B

| Participant ID | Age | Gender | Place of Birth | BLP Score |

| SPA06 | 81 | Female (F) | Mexico | −183.1 |

| SPA07 | 73 | F | Mexico | −69.6 |

| SPA10 | 48 | F | Mexico | −15.7 |

| 1 | As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, research on the prosody of sarcasm should be mindful of the various types of sarcasm when interpreting results. Given that the current study is, to our knowledge, the first of its kind, teasing apart the effects on prosody of subcategories of sarcasm in the speech of heritage speakers is a topic left for future work. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | An anonymous reviewer notes that further exploration of the homeland varieties linked to heritage speakers would be a useful point to consider in related research. To date, the lack of studies on our dependent variables of interest as they pertain to varieties of Mexican Spanish leads us to leave the reviewer’s observation as a consideration for future work. |

| 4 | While this is generally the case when comparing f0 in Spanish and English, an anonymous reviewer points out that f0 range can demonstrate variation across varieties of a given language (see Mennen et al. 2012, 2014 and references therein). |

References

- Aalberse, Suzanne, Ad Backus, and Pieter Muysken. 2019. Heritage Languages: A Language Contact Approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, Brian. 1983. Form and function in children’s understanding of ironic utterances. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 35: 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, Takanori. 1996. Sarcasm in Japanese. Studies in Language 20: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvord, Scott. 2010. Variation in Miami Cuban Spanish interrogative intonation. Hispania 93: 235–55. [Google Scholar]

- Amengual, Mark. 2019. Type of early bilingualism and its effect on the acoustic realization of allophonic variants: Early sequential and simultaneous bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 954–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, Katsura, and Susan Guion. 2007. Prosody in second language acquisition: Acoustic analysis of duration and F0 range. In Language Experience in Second Language Speech Learning: In Honor of James Emil Flege. Edited by Ocke-Schwen Bohn and Murray Munro. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 281–97. [Google Scholar]

- Attardo, Salvatore, Jodi Eisterhold, Jennifer Hay, and Isabella Poggi. 2003. Multimodal markers of irony and sarcasm. Humor-International Journal of Humor Research 16: 243–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, Jacob, Natasha Swiderski, Vanina Machado, Celina Valdivia, Yasaman Rafat, Ryan Stevenson, and Rajiv Rao. Forthcoming. The intonation of absolute questions in Argentinian- and Venezuelan-Canadian heritage speakers of Spanish: Investigating parental and English influences. Spanish as a Heritage Language.

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, Mary, Manuel Díaz-Campos, Julia McGory, and Terrell Morgan. 2002. Intonation across Spanish, in the Tones and Break Indices framework. Probus 14: 9–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David, Libby Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: COERLL, University of Texas at Austin, Available online: https://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual/ (accessed on 30 September 2015).

- Blum-Kulka, Shoshana, and Hadass Sheffer. 1993. The metapragmatic discourse of American-Israeli families at dinner. In Interlanguage Pragmatics. Edited by Gabriele Kasper and Shoshana Blum-Kulka. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 196–224. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2020. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer program]. Version 6.1.16. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Bosker, Hans, Anne-France Pinget, Hugo Quené, Ted Sanders, and Nivja de Jong. 2012. What makes speech sound fluent? The contributions of pauses, speed and repairs. Language Testing 30: 159–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousfield, Derek. 2008. Impoliteness in Interaction. Amsterdam and New York: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, Gregory, and Jean Fox Tree. 2002. Recognizing verbal irony in spontaneous speech. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 17: 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryant, Gregory, and Jean Fox Tree. 2005. Is there an ironic tone of voice? Language and Speech 48: 257–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Busà, Maria Grazia, and Martina Urbani. 2011. A cross linguistic analysis of pitch range in English L1 and L2. In Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Edited by Wai Sum Lee and Eric Zee. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong, pp. 380–83. [Google Scholar]

- Capelli, Carol, Noreen Nakagawa, and Cary Madden. 1990. How children understand sarcasm: The role of context and intonation. Child Development 61: 1824–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheang, Henry, and Marc Pell. 2008. The sound of sarcasm. Speech Communication 50: 366–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheang, Henry, and Marc Pell. 2009. Acoustic markers of sarcasm in Cantonese and English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 126: 1394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheang, Henry, and Marc Pell. 2013. Recognizing sarcasm without language: A cross-linguistic study of English and Cantonese. In Prosody and Humor. Edited by Salvatore Attardo, Manuela Maria Wagner and Eduardo Urios-Aparisi. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Aoju, and Diantha De Jong. 2015. Prosodic expression of sarcasm in L2 English. In L2 Spoken Discourse: Pragmatic and Prosodic Aspects. Edited by Marina Chini. Milano: FrancoAngeli, pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Colantoni, Laura, Alejandro Cuza, and Natalia Mazzaro. 2016. Task related effects in the prosody of Spanish heritage speakers. In Intonational Grammar in Ibero-Romance: Approaches Across Linguistic Subfields. Edited by Meghan Armstrong, Nicholas Henriksen and Maria Vanrell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cruttenden, Alan. 1984. Intonational misfits. In Intonation, Accent and Rhythm. Edited by Dafydd Gibbon and Helmut Richter. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper, Jonathan. 2005. Impoliteness and entertainment in the television quiz show: The Weakest Link. Journal of Politeness Research 1: 35–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cutler, Anne, Delphine Dahan, and Wilma van Donselaar. 1997. Prosody in the Comprehension of Spoken Language: A Literature Review. Language and Speech 40: 141–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De-la-Mota, Carme, Pedro Martín Butragueño, and Pilar Prieto. 2010. Mexican Spanish intonation. In Transcription of Intonation of the Spanish Language. Edited by Pilar Prieto and Paolo Roseano. Munich: Lincom, pp. 319–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dews, Shelly, Joan Kaplan, and Ellen Winner. 1995. Why not say it directly? The social functions of irony. Discourse Processes 19: 347–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dews, Shelly, Ellen Winner, Joan Kaplan, Elizabeth Rosenblatt, Malia Hunt, Karen Lim, Angela McGovern, Alison Qualter, and Bonnie Smarsh. 1996. Children’s understanding of the meaning and functions of verbal irony. Child Development 67: 3071–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupoux, Emmanuel, Christophe Pallier, Nuria Sebastian, and Jacques Mehler. 1997. A destressing “deafness” in French? Journal of Memory and Language 36: 406–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elias, Maria. 2013. ‘Tengo bien harto esperando en la línea’ (I am fed up waiting in line): Complaint Strategies by Second-Generation Mexican-American Bilinguals. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Arizona State University, Tucson, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Estebas-Vilaplana, Eva. 2014. The evaluation of intonation: Pitch range differences in English and in Spanish. In Evaluation in Context. Edited by Geoff Thompson and Laura Alba-Juez. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 179–94. [Google Scholar]

- Face, Timothy, and Pilar Prieto. 2007. Rising accents in Castilian Spanish: A revision of Sp_ToBI. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 6: 117–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fonagy, Ivan. 1971. Synthèse de l’ironie (Overview of irony). Phonetica 23: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froemming, Brenda, and Rajiv Rao. 2021. The tritonal pitch accent in the broad focus declaratives of the Spanish spoken in Cuenca, Ecuador: An acoustic and sociolinguistic analysis. Estudios de Fonética Experimental (Journal of Experimental Phonetics) 29: 119–40. [Google Scholar]

- García, Maryellen, and Elizabeth Leone. 1984. The use of directives by two Hispanic children: An exploration of communicative competence. In National Center of Bilingual Research Report Series. Los Alamitos: National Center for Bilingual Research, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, Andrew, and Jennifer Hill. 2006. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrig, Richard, and Yegeniya Goldvarg. 2000. Additive effects in the perception of sarcasm: Situational disparity and echoic mention. Metaphor and Symbol 15: 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Raymond. 2000. Irony in talk among friends. Metaphor and Symbol 15: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenwright, Melanie, and Penny Pexman. 2010. Development of children’s ability to distinguish sarcasm and verbal irony. Journal of Child Language 37: 429–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Glenwright, Melanie, Jayanthi Parackel, Kristene Cheug, and Elizabeth Nilsen. 2014. Intonation influences how children and adults interpret sarcasm. Journal of Child Language 41: 472–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gussenhoven, Carlos. 2002. Intonation and interpretation: Phonetics and phonology. In Proceedings of Speech Prosody 2002. Edited by Bernard Bel and Isabelle Marlien. Aix-en-Provence: Laboratoire Parole et Langage, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Rivas, Carolina. 2008. Actos de habla mixtos: Reflexiones sobre la pragmática del español en referencia a la teoría y métodos actuales de análisis. Núcleo 20: 149–71. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Rivas, Carolina. 2011. El efecto del género en el discurso bilingüe. Un estudio sobre peticiones. (The effect of gender in bilingual discourse. A study on requests). Estudios de Lingüística Aplicada 29: 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Haiman, John. 1998. Talk is Cheap: Sarcasm, Alienation, and the Evolution of Language. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, Jeffrey, Philip Dunham, and Kelley Purdy. 2000. Children’s comprehension of critical and complimentary forms of verbal irony. Journal of Cognition & Development 1: 227–48. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Melanie, and Penny Pexman. 2003. Children’s perceptions of the social functions of verbal irony. Discourse Processes 36: 147–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Michael, Viola Miglio, and Stefan Th. Gries. 2015. Mexican and Chicano prosody: Differences related to information structure. In Proceedings of the 6th Annual Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference. Edited by John Levis, Rania Mohammed, Manman Qian and Ziwei Zhou. Ames: Iowa State University, pp. 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Haverkate, Henk. 1984. Speech Acts, Speakers, and Hearers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia, Roberto, and Anna Cieślicka. 2015. Bilingual Figurative Language Processing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hualde, José Ignacio, and Pilar Prieto. 2016. Towards an International Prosodic Alphabet (IPrA). Laboratory Phonology 7: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keenan, Thomas, and Kathleen Quigley. 1999. Do young children use echoic information in their comprehension of sarcastic speech? A test of echoic mention theory. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 17: 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jiyun. 2014. How Korean EFL learners understand sarcasm in L2 English. Journal of Pragmatics 60: 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Ji Young. 2019. Heritage speakers’ use of prosodic strategies in focus marking in Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Ji Young, and Gemma Repiso-Puigdelliura. 2021. Keeping a Critical Eye on Majority Language Influence: The Case of Uptalk in Heritage Spanish. Languages 6: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissling, Elizabeth. 2018. An exploratory study of heritage Spanish rhotics: Addressing methodological challenges of heritage language phonetics research. Heritage Language Journal 15: 25–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfhagen, David, Rajiv Rao, and Sandro Sessarego. 2021. Declarative intonation in four Afro-Hispanic varieties: Phonological analysis and implications. In Aspects of Latin American Spanish Dialectology. In Honor of Terrell A. Morgan. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos and Sandro Sessarego. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 155–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, D. Robert. 2008. Intonational Phonology, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laval, Virginie, and Alain Bert-Erboul. 2005. French-speaking children’s understanding of sarcasm: The role of intonation and context. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 48: 610–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, Geoffrey. 1983. Principles of Pragmatics. New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler, Jean. 1979. Categorical and schematic organization in memory. In Memory, Organization, and Structure. Edited by Richard Puff. New York: Academic Press, pp. 259–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mennen, Ineke, Felix Schaeffler, and Gerard Docherty. 2012. Cross-language differences in fundamental frequency range: A comparison of English and German. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 131: 2249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mennen, Ineke, Felix Schaeffler, and Catherine Dickie. 2014. Second language acquisition of pitch range in German learners of English. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 36: 303–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina Andrea. 2012. The grammatical competence of Spanish heritage speakers. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States. Edited by Sara Beaudrie and Marta Fairclough. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 101–20. [Google Scholar]

- Oprea, Silviu Vlad, and Walid Magdy. 2020. The effect of sociocultural variables on sarcasm communication online. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 4: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual y Cabo, Diego, and Jason Rothman. 2012. The (il)logical problem of heritage speaker bilingualism and incomplete acquisition. Applied Linguistics 33: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Passoni, Elisa, Adib Mehrabi, Eroz Levon, and Esther de Leeuw. 2018. Bilingualism, pitch range and social factors: Preliminary results from sequential Japanese-English bilinguals. Proceedings of Speech Prosody 2018: 384–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko, Aneta. 2006. Bilingual Minds. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Jörg. 2019. Fluency and speaking fundamental frequency in bilingual speakers of high and low German. In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Melbourne, Australia 2019. Edited by Sasha Calhoun, Paola Escudero, Marija Tabain and Paul Warren. Canberra: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc., pp. 1655–59. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Sara, Kathryn Wilson, Timothy Boiteau, Carlos Gelormini-Lezama, and Amit Almor. 2016. Do you hear it now? A native advantage for sarcasm processing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognitition 19: 400–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrehumbert, Janet. 1980. The Phonology and Phonetics of English Intonation. Doctoral dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, Derrin. 2018. Heritage Spanish pragmatics. In The Routledge Handbook of Spanish as a Heritage Language. Edited by Kim Potowski. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 190–202. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, Derrin, and Richard Raschio. 2007. A comparative study of requests in heritage speaker Spanish, L1 Spanish, and L1 English. International Journal of Bilingualism 11: 135–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, Derrin, and Richard Raschio. 2008. Oye, ¿qué onda con mi dinero? An analysis of heritage speaker complaints. Sociolingusitic Studies 2: 221–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim. 2007. Language and Identity in a Dual Immersion School. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Rajiv. 2013. Prosodic consequences of sarcasm versus sincerity in Mexican Spanish. Concentric: Studies in Linguistics 39: 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Rajiv. 2016. On the nuclear intonational phonology of heritage speakers of Spanish. In Advances in Spanish as a Heritage Language. Edited by Diego Pascual y Cabo. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Rajiv. 2019. The phonological system of adult heritage speakers of Spanish in the United States. In The Routledge Handbook of Spanish Phonology. Edited by Sonia Colina and Fernando Martínez-Gil. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 439–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Rajiv, and Mark Amengual. 2021. The phonetics and phonology of heritage Spanish. In Aproximaciones al estudio del español como lengua de herencia. Edited by Diego Pascual y Cabo and Julio Torres. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Puente, Sergio. 2014. Prosody in Contact: Spanish in Los Angeles. Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell, Patricia. 2000a. Actors’, partners’, and observers’ perceptions of sarcasm. Perceptual and Motor Skills 91: 665–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, Patricia. 2000b. Lower, slower, louder: Vocal cues of sarcasm. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 29: 483–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwell, Patricia. 2005. Sarcasm on television talk shows: Determining speaker intent through verbal and nonverbal cues. In Psychology of Moods. Edited by Anita Clark. New York: Nova Science, pp. 109–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell, Patricia. 2007. Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 36: 361–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, Rachel. 2021. Researching Spanish heritage language pragmatics in study abroad. In Heritage Speakers of Spanish and Study Abroad. Edited by Rebecca Pozzi, Tracy Quan and Chelsea Escalante. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 101–16. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. The gradual loss of mood distinctions in Los Angeles Spanish. Language Variation and Change 6: 255–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 2001. Sociolingüística y pragmática del español. (Sociolinguistics and pragmatics of Spanish). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Skoog Waller, Sara, and Mårten Eriksson. 2016. Vocal age disguise: The role of fundamental frequency and speech rate and its perceived effects. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ullakonoja, Riikka. 2007. Comparison of pitch range in Finnish (L1) and Russian (L2). In Proceedings of the 16th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Edited by Jürgen Trouvain and William Barry. Saarbrücken: Saarbrücken University, pp. 1701–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ushakova, Tatiana. 1994. Inner speech and second language acquisition: An experimental-theoretical approach. In Vygotskian Approaches to Second Language Research. Edited by James Lantolf and Gabriela Appel. Norwood: Ablex, pp. 135–56. [Google Scholar]

- Voyer, Daniel, and Cheryl Techentin. 2010. Subjective auditory features of sarcasm. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 227–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, Joel. 1981. Variation in the requesting behavior of children. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 27: 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichmann, Anne. 2000. The Attitudinal Effects of Prosody, and How They Relate to Emotion. Available online: https://www.isca-speech.org/archive_open/archive_papers/speech_emotion/spem_143.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Winner, Ellen. 1988. The Point of Words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winner, Ellen, and Sue Leekam. 1991. Distinguishing irony from deception: Understanding the speaker’s second-order intention. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 9: 257–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Desai, Yang. 2019. Heritage Learner Pragmatics. In Handbook of SLA and Pragmatics. Edited by Naoko Taguchi. New York: Routledge, pp. 462–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zárate-Sández, Germán. 2015. Perception and Production of Intonation among English-Spanish Bilingual Speakers at Different Proficiency Levels. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

| Panel | Attitude | Language | Speech Rate (syll/s) | f0 Mean (Hz) | f0 Range (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | Sarcastic | Spanish | 3.8 | 204.3 | 119.8 |

| 2b | Sarcastic | English | 5.9 | 166.6 | 68.1 |

| 2c | Sincere | Spanish | 5.5 | 218.0 | 122.7 |

| 2d | Sincere | English | 6.1 | 182.4 | 122.3 |

| Dependent Variable | Main Effects | Interactions |

|---|---|---|

| Speech rate | Attitude Language | Attitude × Language Attitude × Age Language × Age Language × Gender Language × Dominance |

| f0 mean | Attitude Language Gender | Attitude × Language × Age Attitude × Bilingual type Language × Dominance |

| f0 range | Attitude Language Gender | Attitude × Bilingual type Language × Dominance |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rao, R.; Ye, T.; Butera, B. The Prosodic Expression of Sarcasm vs. Sincerity by Heritage Speakers of Spanish. Languages 2022, 7, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010017

Rao R, Ye T, Butera B. The Prosodic Expression of Sarcasm vs. Sincerity by Heritage Speakers of Spanish. Languages. 2022; 7(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleRao, Rajiv, Ting Ye, and Brianna Butera. 2022. "The Prosodic Expression of Sarcasm vs. Sincerity by Heritage Speakers of Spanish" Languages 7, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010017

APA StyleRao, R., Ye, T., & Butera, B. (2022). The Prosodic Expression of Sarcasm vs. Sincerity by Heritage Speakers of Spanish. Languages, 7(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010017