1. Introduction

Heritage speakers present a unique profile and perspective on the study of language. Several researchers have tried to pinpoint heritage speakers by certain sociolinguistic characteristics, such as culture, familial relationships, immigration, and shifts in their linguistic dominance. From a broad perspective, heritage speakers are people with a connection to a language or speakers who identify culturally and/or ethnically with the language, regardless of their proficiency in it (

Fishman 2001;

Van Deusen-Scholl 2003). From a narrower perspective, heritage speakers are people who were exposed to or learned a language to an extent in infancy, and who preserve a certain level of proficiency in it (

Polinsky and Kagan 2007). The most commonly understood sense of the word in current research is that of

Valdés (

2000) and

Polinsky and Kagan (

2007). Valdés, referring to speakers in the United States, where the community language is English, defines heritage speakers as “individuals raised in homes where a language other than English is spoken and who are to some degree bilingual in English and the heritage language”.

Polinsky and Kagan (

2007) define them as “people raised in a home where one language is spoken who subsequently switch to another dominant language” (p. 368).

Among heritage speakers, many are also heritage learners (HL) of their heritage language. Heritage learners speak “ethnolinguistically minority languages who were exposed to the language in the family since childhood and as adults wish to learn, relearn, or improve their current level of linguistic proficiency in their family language” (

Montrul 2010, p. 3). Therefore, heritage speakers’ linguistic profile is defined by an early exposure to a minority language at home and a shift of primary language status in infancy to the majority language.

Therefore, the goal of this study is to delve into the acquisition of the perception of the Spanish /e/-/ei/ contrast in the phonetics/pronunciation classroom. The focus of this study is twofold: first, it analyzes the difference between heritage Spanish and L2 Spanish learners, and second, it analyzes the difference between High Phonetic Variability Training (HPVT) as an explicit instruction method, as opposed to regular explicit phonetic instruction, with low variability training. HPVT research has overwhelmingly focused on English, and heritage learners of Spanish, to the author’s knowledge, have not been studied. The perceptual contrast between Spanish /e/ and /ei/ and the extent to which explicit phonetics classroom methodologies such as HPVT can aid improving it have not been studied either.

By examining in combination the effects of different explicit phonetics classroom methodologies on the /e/-/ei/ pair on different learners (with a particular focus on heritage learners), this exploratory study gives some preliminary results that could help learners, researchers, and instructors identify challenging sound categories and tailor their learning and teaching so as to shift their attention towards specific pedagogical needs and to create appropriate teaching methodologies with measurable learning objectives.

1.1. Heritage Language Phonology

In spite of the heterogeneity of the proficiency levels of the group, heritage learners have shown some advantageous patterns over L2 learners. Although their acquisition is interrupted, it does not signify a complete halt and loss (

Godson 2004). Research has shown benefits from those linguistic aspects acquired in the earliest stages in life, as opposed to those acquired later in life that either undergo attrition or are not acquired whatsoever. One of the aspects that tend to be preserved best is phonology (

Au et al. 2008;

Polinsky 2015;

Rao and Ronquest 2015). The phonology of a first language is acquired in the earliest stages of the acquisition of the first language. Native-like acquisition of the phonology is considered to occur when the second language is learned between ages 0 and 6–7 as, during that time, the experience with sounds shapes the phonetic perception of infants (

Kuhl and Iverson 1995;

Leather 1999;

Long 1990;

Singleton and Ryan 2004), and it starts decreasing gradually from ages 6 to 12. Some researchers claim an even earlier start and end date to phonological acquisition—from bias towards the native sound system starting in utero (

Ramus et al. 1999) to the end of the sensitive period shortly after birth (

Hyltenstam and Abrahamsson 2003;

Strange and Shafer 2008), up to 6 months of age (

Guion-Anderson 2013), or up to 1 year of age (

Archibald 1998;

Ruben 1997); researchers agree the shaping of a phonological system and language-specific perceptual mapping occurs and solidifies fast (

Werker 1995).

Therefore, a common impression observed in the literature is that heritage learners’ phonological system is more closely aligned with the first language (

Chang 2016;

Lukyanchenko and Gor 2011;

Montrul 2010). Nevertheless, the notion of heritage learners having an advantage in the phonology of their heritage language cannot be equated either with dominant native-like proficiency or with a native-like heritage phonology (

Chang 2016;

Montrul 2010;

Polinsky 2015). Heritage learners’ primary language is not their heritage language, so limitations and differences arise in the (re-)learning process, even for heritage learners with a high proficiency level, exposure, and vast experience with the language, resulting in significant differences in the realization of categories when compared to L1 dominant speakers (

Chang 2016;

Chang et al. 2011). Although heritage phonology is relatively understudied in comparison to heritage morphosyntax, studies in heritage phonology have shown patterns of systemic, nonnative-like characteristics in heritage learners (

Montrul 2010). Studies on heritage language perception and heritage language vowels are summarized below.

1.1.1. Heritage Learner Perception

When considering cross-linguistic speech perception, theories such as the Perceptual Assimilation Model (PAM,

Best 1995;

Best and Tyler 2007) and the Speech Learning Model (SLM,

Flege 1995,

2003) describe the nature of the perceptual interaction of two languages by considering (a) the phonetic similarities and differences between the phonological categories of both languages and (b) the assumption that the perception of the L1 phonological system will be the starting point for the second language. For learners who learn a second language in adulthood, their perception of a second language is warped by linguistic experience, input, and use, solely of the L1.

Heritage learners present a unique challenge to these speech perception theories because, on the one hand, their L1 phonological system, which was acquired and solidified very early, is in competition with the phonological system of the L2. However, this L2 shifts in infancy to become the primary language, relegating and replacing their linguistic experience, input, and use of the L1, so that they begin almost always to communicate in the L2. In spite of this replacement process, the perception of the sounds of the heritage language seems generally to be maintained, regardless of the level of attrition (

Au et al. 2002;

Chang 2016;

Lukyanchenko and Gor 2011;

Montrul 2010;

Oh et al. 2003;

Trujillo 2013).

Chang (

2016, p. 793) explains that “the perceptual advantages resulting from HL experience are particularly compelling because they can be evident even after decades of separation from the initial HL experience and without extensive re-exposure to the HL”. This could be explained within the Cognitive Phonology framework (CP,

Fraser 2006), which draws on the mental representations of phonological categories and how these categories are formed (

Mompean 2003). Having formed and established mental representations of phonological categories early on, it is likely that heritage learners are still able to retrieve them successfully even after a period of dormancy in input and use.

There are many studies, on the other hand, that have seen heritage learners performing differently in their perception of their heritage language than monolingual speakers of the said language.

Lee-Ellis (

2012) found heritage learners of Korean to perform at an intermediate stage between monolingual speakers and L2 learners, and

Lukyanchenko and Gor (

2011) found non-nativelike perception in some Russian contrasts.

Au et al. (

2008) found significantly better perception of Korean sentences by heritage speakers and heritage overhearers than L2 learners, but not a significant difference between the two heritage groups, and

Park (

2009) found L2 English Korean speakers to outperform bilingual Korean-English speakers in perceiving a foreign accent in English, which could signal that heritage learners use L2 categories as a reference to perceive L2 sounds, whereas those who are not as experienced with the L2 rely on L1 sounds (

Park 2009).

In sum, speech perception of the heritage language seems to be robust in spite of the shift in dominance to the majority language and even on par with that of monolingual speakers of the language. However, other linguistic features seem to show that heritage learners are at an intermediate stage of perception between monolingual and L2 speakers.

1.1.2. Heritage Learner Vowels

Phonology is one of the aspects of language that is developed at the earliest stage in language acquisition. Regarding specific speech units, the development of speech acquisition from language-general to language-specific occurs earlier for vowels than for consonants (

Flege et al. 1997;

Polka and Werker 1994). Different studies have shown that vocalic phonemes are established remarkably fast: overlap in the vocalic space is reduced by week 66 of life (

Lieberman 1980), and a study of 100 children found the establishment of vocalic phonemes to occur for 87% of participants by age 4 and for 98% by age 6 (

Irwin and Wong 1983). In spite of the swift categorization of native vowels in early infancy, heritage speakers show different patterns than monolinguals. These patterns can be affected by vowel type, dominance, and stress patterns.

Heritage learner research has exponentially increased since more and more heritage learners return to classes to regain competency in their first language, but a lack of research of their phonological system remains, mainly due to the notion that the early acquisition of phonology gives heritage learners a native-like advantage on their pronunciation (

Au et al. 2008).

Godson (

2003,

2004) was one of the first researchers who studied heritage speakers’ vowels. Western Armenian heritage speakers in California were compared to monolinguals and Western Armenian dominant bilinguals in their production of vowels. Results differed by vowel: heritage speakers produced vowels /i/, /ε/, and /a/ closer to English values. However, their vowels /o/ and /u/, although they were different to Western Armenian monolingual and dominant bilinguals’ values, were not close to English values, signaling a distinct vowel categorization not affected either by the heritage or the primary language.

In the case of heritage Spanish, studies have mostly focused on consonants because monophthongs /i, e, a, o, u/ are considered to be “easy” to acquire, subject to little variation, and relatively stable across dialects (

Hualde 2005;

Quilis and Esgueva 1983;

Rao and Kuder 2016;

Ronquest 2013). In theory, the uncrowded nature of the Spanish vocalic space, as opposed to the complex English vocalic space, only supposes the elimination of vocalic contrasts by assimilating native categories into new target language categories (

Cobb and Simonet 2015). However, vowels that are considered “equivalent” across languages can have different phonetic features that may impede the correct perception and/or production of the L2 sound.

Spanish and English vowels are affected by features such as lexical stress differently: English has traditionally been classified as a stress-timed language that tends toward quality and quantity reduction in unaccented syllables, whereas Spanish has been classified as a syllable-timed language, which shows the same quality and quantity across syllables regardless of stress placement (

Pike 1945). Studies on the vocalic system of heritage Spanish speakers in the United States have found that heritage speakers of Spanish show a different vocalic space than that of Spanish monolinguals (

Rao and Ronquest 2015). It has been observed that front vowels /i, e, a/ are more dispersed in the vocalic space, whereas back vowels /o, u/ are more condensed (

Boomershine 2012;

Ronquest 2012;

Willis 2005).

Ronquest (

2016) also found differences in duration for vowels /a/ and /o/ in heritage speakers, as well as changes in the dispersion of vowels depending on their control over speech. Many studies have also shown a tendency to vowel centralization (

Boomershine 2012;

Ronquest 2012,

2013;

Willis 2005) and shortening of the duration of unstressed vowels (

Ronquest 2013). A tendency to the fronting of /u/ has also been found in heritage learners of Spanish from Chicago (

Cummings Diaz 2019) and from New Mexico (

Willis 2005). Although these differences may signal transfer from English,

Alvord and Rogers (

2014) also found vowel reduction to occur equally in Spanish heritage speakers and in late immigrant Spanish dominant bilinguals from Cuba in Miami.

Shea (

2019) explains that the differences observed between monolingual and heritage learners of a language may be due to some contrasts being lessened to a certain extent in heritage learners, while other sound categories are maintained at a similar level as monolinguals. This could be a result of phonological structural simplification affecting some specific categories, such as consonant clusters or diphthongs, which can be simplified into single consonants or monophthongs (

Shea 2019).

1.2. /e/-/ei/ Contrast

Among the sounds that could undergo the aforementioned process, the contrast under analysis in this study presents a competition between a monophthong and a diphthong. The mid-front unrounded vowel /e/ is present both in Spanish and in English. We can find these sounds in words such as

pena (“pity”) or

pain. However, their phonetic realizations are very different: Spanish /e/ is a short and pure monophthong with no shift in formant values, whereas American English /eɪ/ starts in a more central position in the oral cavity and is diphthongized in an upward glide in the articulation (

Counselman 2015;

Hualde 2005). Due to their different realizations, the relationship between the sounds of both languages is different too: Spanish /e/ is similar to both American English /ɛ/ and /eɪ/, but it is not identical to either, as there is both a tense and a non-diphthongized realization.

Unlike other English dialects, American English does not have a mid-front unrounded monophthong, but only a diphthong. English /eɪ/ is very similar to both the Spanish monophthong /e/ and the diphthong /ei/ and is also an intermediate segment between the two. The English vowel shows an upward glide of the F2 at the end of the vowel when compared to Spanish /e/, whereas the Spanish diphthong is longer than the American English diphthongized vowel /eɪ/ (

Hualde 2005;

Díaz and Simonet 2015). There are two possible scenarios for this situation (

Díaz and Simonet 2015): on the one hand, Spanish /e/ can be assimilated to English /eɪ/, resulting in a diphthongized production of the phoneme. On the other hand, Spanish /e/ can be assimilated to English /ɛ/ while Spanish /ei/ is assimilated to /eɪ/. Although American English /ɛ/ could be a close vocalic category in relation to Spanish /e/, American English /eɪ/ is closer. This leads to a diphthongized production of Spanish /e/.

The diphthongization of the Spanish vowel /e/ by monolingual English speakers distorts the segment and changes the phonemic category of the segment, which can result in an intelligibility problem and a breakdown in communication: the mismatch in both Spanish segments could lead to intelligibility problems in minimal pairs that entail both semantic differences (such as

pena, “pity”, and

peina, “he/she brushes”) and verbal paradigm differences (such as

ves, “you [singular] see”, and

veis, “you [plural] see”). The lack of differentiation between Spanish /e/ and /ei/ is an example of an equivalence classification situation as presented in the Speech Learning Model (

Flege 1995). This situation blocks the creation of two separate categories for the Spanish monophthong and the diphthong. Therefore, both Spanish sounds are perceived as the same phonetic category and are produced similarly as well. This mismatch in the inventory of Spanish and American English has been observed in the perceptual and production problems of Spanish language learners.

The few studies that have analyzed this contrast have focused on the production and explicit instruction of L2 learners:

Díaz and Simonet (

2015) found that L2 Spanish adult learners of different proficiency levels produced /e/ similarly, but with differences when the segment occurred in the penultimate syllable vs. in the last syllable: the former were produced monophthongally, while the latter were produced with a slight diphthongization. In addition, /ei/ was produced differently across groups: native speakers and L2 advanced learners produced a distinct, clear-cut diphthong, whereas intermediate learners did not show a full diphthong, possibly due to the earlier acquisition of the pure, monophthongal characteristics of Spanish /e/, rather than the diphthongal nature of Spanish /ei/.

Moorman (

2017) analyzed the production of Spanish /e/ and /o/ by intermediate and advanced learners enrolled in the 2nd and 6th semester of Spanish courses. Results showed that beginner learners improved their production of these segments, whereas advanced learners did not. The mean F1 and F2 bark values of the advanced group were significantly higher than the native control group, whereas there was not a significant difference between the intermediate and native groups. Both learner groups produced /e/ with a longer duration than their native /e/, but the advanced group’s mean duration was closer to the native group than the intermediate group’s mean duration.

One of the few studies on explicit instruction of the Spanish /e/-/ei/ contrast in the classroom is by

Counselman (

2015). He analyzed the effect of awareness raising in pronunciation in two groups of L2 Spanish learners enrolled in two sections of a conversational Spanish class. Results showed that training that directed the attention to phonetic features in perception was more effective in the development of their production than articulatory training. The considerations that researchers and instructors need to take into account in the design of training and measurements—for example, whether perception and production should be treated equally, or how different learner profiles can benefit from explicit instruction—remain open to more research (

Leather 1999).

1.3. High Phonetic Variability Training

A learner profile that has received very little attention with regard to phonetic or phonological instruction are heritage learners. Only the exploratory study of

Rao et al. (

2020) gives us a glimpse into the effect of explicit phonetic instruction on heritage Spanish learners: after a semester-long explicit phonetic instruction course, five Spanish heritage learners showed significant improvements from pre-test to post-test in the production of mean pitch, pitch range, speech rate, voiceless consonants, and vowels. These significant changes show that heritage learners are not like monolingual native speakers of Spanish. Thus, heritage learners show divergences in their heritage phonological systems, as well as different needs and learning challenges from those of L2 learners (

Montrul 2010). Nevertheless, the assumption that their pronunciation is native-like has meant that this aspect of language learning is assigned a very low priority in the classroom (

Rao and Kuder 2016).

Rao and Kuder (

2016) explain that, in a 2011 survey of the Center for Applied Linguistics, only 2 of 137 textbooks used specifically for heritage learners of Spanish included a section on phonetics and phonology, and that only 10 mentioned pronunciation as a learning objective. Consequently, either heritage learner-specific explicit instruction methods are nonexistent, or current explicit instruction methods have not been applied to heritage learners.

A type of perceptual phonetic training applied to L2 learners that has recently gained traction and has led to numerous research works is High Phonetic Variability Training (HPVT). HPVT consists in exposing learners to the production of sounds by multiple talkers, in different phonetic contexts, and in different communicative settings, rather than one source of speech in the classroom (

Bradlow 2018;

Guion-Anderson 2013;

Kingston 2003;

Thomson 2011). Phonetic representation has two levels: the exemplar level and the category level. The exemplar level records instance-specific tokens and richly detailed acoustic records, whereas the category level imposes generalizations over exemplars to apply patterns that result in essential, linguistically relevant, contrastive features (

Bradlow 2018). By employing high variability in speech, this training resembles the acquisition of a first language and natural acquisition (

Kingston 2003). Training combined with attentional orienting to specific phonetic features also increases the probability of short-term memory processing of the features, and with that, the probability of transferring them from short- term to long-term memory (

Guion-Anderson 2013). Previous studies on the training of the perception and production of L2 sounds have provided stimuli with essential differences between contrastive categories, and their tasks have encouraged discrimination between items in contrastive pairs. It begs the question whether it is enough to be exposed to certain examples of a contrast in order to be able to generalize to new examples, and whether training can lead to transfer competence regarding new tasks—that is, whether the acquisition can support various linguistic functions, such as perception (

Bradlow 2018).

The first studies to start including more variability in the training of learners were those on the English /ɻ/-/l/ contrast (

Logan et al. 1991;

Lively et al. 1993,

1994;

Bradlow et al. 1997) and on Mandarin tones (

Wang et al. 2003). These studies found that exposure to high variation provided direct and indirect benefits in the acquisition of this contrast: Directly, emphasizing consistent variation and multiple levels of similarity allowed the development of multiple levels of speech representation—the phoneme, the talker, the group, etc. Indirectly, highly variable exposure allows learners to create a model for the “golden talker”, offering a clearer and faster path to be able to linguistically form a category for a sound (

Bradlow 2018). These generalization effects were also found to remain six months after the study was conducted (

Lively et al. 1994).

Regarding speech perception, HPVT has generally shown improvement in the perception of many linguistic aspects, including vowels (

Aliaga-Garcia and Mora 2007;

Carlet and Cebrian 2014;

Kingston 2003;

Lambacher et al. 2005;

Iverson et al. 2012). Most studies have focused on English vowels:

Aliaga-Garcia and Mora (

2007) and

Carlet and Cebrian (

2014) studied L1 Catalan learners of English and found that significant improvements occurred in the identification of vowels /i/ and /ʌ/ and in the discrimination of vowel pairs /i:/-/ɪ/ and /æ/-/ʌ/. However, the identification of vowels /ɪ/ and /æ/ did not show any improvement, and accuracy levels were significantly lower than those of native speakers.

Lambacher et al. (

2005) analyzed L1 Japanese speakers enrolled in an HPVT course vs. control learners. They found that HPVT learners improved their identification of English vowels /æ, ɑ, ʌ, ɔ, ɜ/ by 16%, while the control group only improved by 5%.

Studies concerning HPVT and languages other than English are sparser, but they have still rendered positive results.

Kingston (

2003) studied the perception of German round vowels by L1 American English and focused on the perception of three features: height, frontness, and tenseness. The results of height and frontness showed that learners had acquired the German vowels by feature, and not as exemplars: the new vowels that the learners heard in the testing stage were perceived more accurately in height and frontness than the training vowels, particularly when more vowel pairs were used in the training stage. Therefore, he found that exposure to multiple speakers from the same background led to talker-independent perception, that is, acquisition at the category level.

Iverson et al. (

2012) analyzed the performance of both L2 French and L2 English learners after HPVT and found significant gains in discrimination and identification tasks for both groups.

The results of these studies suggest that “highly variably training stimuli facilitate development of robust L2 speech categories, segmental and prosodic, that can be used in both production and perception” (

Guion-Anderson 2013, p. 6). However, all of these studies have looked at HPVT on its own. Only a handful of studies have compared HPVT to more traditional explicit phonetic instruction types.

Wong (

2012) compared the perception and production of English /e/ and /æ/ by L1 Cantonese speakers enrolled in two groups: a high phonetic variability training group (HPVT) and a low variability phonetic training group (LPVT). The results showed a significant difference between groups both in the perception and the production tasks, and that the HPVT group improved more than the LPVT group in the post-test. In addition to the lack of a comparison of HPVT with other types of training, the research on HPVT is mostly centered around the learning of English (

Barriuso and Hayes-Harb 2018) and second or foreign language learners. The effects of HPVT on Spanish sounds and on different learner profiles, such as heritage learners, are still to be researched. Considering its positive effects on L2 learners’ perception, its application to heritage learners could render interesting and positive results.

1.4. Research Questions

Building on previous literature, this study aimed to shed light on the effect of different explicit phonetics instruction types, particularly High Phonetic Variability Training, on the development of the perception of the Spanish segments /e/ and /ei/ by heritage and L2 Spanish learners enrolled in an upper-level undergraduate phonetics course, with particular focus on heritage learners. The research questions are the following:

• (1) Is there a difference between the perception of Spanish /e/ and /ei/ by speakers of Spanish as a primary language and that of heritage speakers of Spanish?

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Although the heritage learners’ perception of the contrast may diverge from that of speakers of Spanish as a primary language, it is expected that they will perceive this distinction at a similar level to that of dominant Spanish speakers.

• (2) Is there a difference between the perception of Spanish /e/ and /ei/ by heritage and L2 speakers?

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Heritage learners will perceive this distinction more accurately than L2 speakers due to their early exposure to the target language.

• (3) Does HPVT aid learners in the perception of this contrast better than LPVT?

Hypothesis 3 (H3). It is expected that participants enrolled in the HPVT treatment group will outperform participants enrolled in the regular phonetics course (LPVT treatment group). However, to the knowledge of the author, HPVT has not been studied in heritage learners, so its effect on this specific population remains to be seen.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Four groups of participants from a large Midwestern university were recruited for this study—a group of heritage learners of Spanish in the HPVT classroom (HPVT-Her), a group of heritage learners in the LPVT classroom (LPVT-Her), a group of advanced Spanish L2 learners in the HPVT classroom (HPVT-L2), and a group of advanced Spanish L2 learners in the LPVT classroom (LPVT-L2). In total, 27 subjects participated in this experiment.

The HPVT-Her group, the focus of this study, contained 6 heritage learners of Spanish enrolled in section A of the course SPAN 303: “Sounds of Spanish”, an upper-division undergraduate course, geared towards upperclassmen Spanish majors and minors, that focuses on explicit phonetic instruction. Their first language was either only Spanish or Spanish and English. All but one were 2nd generation Spanish speakers born in the United States. Five of the participants were of Mexican origin, and one was of Puerto Rican origin (

Table 1). The LPVT-Her group contained 3 heritage learners of Spanish enrolled in section B of the same course. Their first language was also either only Spanish or Spanish and English, although one of the participants mentioned being an “overhearer” of Spanish. This participant was a 3rd generation speaker of Cuban origin, and the other two were 2nd generation speakers of Mexican origin (

Table 1). The two L2 groups, HPVT-L2 (11 participants) and LPVT-L2 (7 participants), were enrolled in the corresponding sections alongside heritage learners. These participants were all from the Midwest, English was their first language, and they had started learning Spanish in their teenage years or later (

Table 2). Although neither the Spanish major nor the Spanish minor at this university follow a specific sequencing of the courses, SPAN 303 is usually taken by students in their final two years of the program, though some students enroll in their 2nd year. Due to this, the Spanish level of these students varies. At graduation, the program expects an advanced low level in Spanish majors according to the

ACTFL (

2012).

In order to establish a baseline for how speakers whose primary language is Spanish perceive the /e/-/ei/ contrast, 7 speakers from Spain, Ecuador, Mexico, El Salvador, and Puerto Rico were recruited as part of the control group. These participants were recruited to establish the difference between the participants and a primary, native Spanish model, thus testing the occurrence of perception differences in the speech of heritage and L2 learners, regardless of instruction group. All were doctoral students who had moved to the United States from their home countries to pursue graduate studies, and each of them had learned English as an L2 in adulthood.

Although both sections of SPAN 303 used the same textbook, the pedagogic methodologies of the sections were different. In the HPVT section of the course, the participants’ source of Spanish input was varied: participants were exposed to recordings of multiple speakers of different dialects of Spanish, as well as the instructor’s input. The instructor was originally from Spain and had spoken Spanish her entire life. In the LPVT section of the course, the participants’ sole source of input was their instructor. The instructor was originally from Michigan and was an advanced doctoral candidate of the Spanish Linguistics program at the university. The instructor of the HPVT section provided the LPVT section instructor with the materials before applying the changes to reflect the multiple sources of speech in each lesson.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Instruction

Participants were divided into groups depending on their enrollment in the two sections of SPAN 303: “Sounds of Spanish” course—section A (HPVT training) or section B (LPVT training). Participants were not made aware of the difference between the sections. Regardless of the section, students followed the same syllabus and calendar: first, they were instructed on the concepts of syllabification, lexical stress, and the phoneme-allophone relationship. Second, the phonetic theory behind each Spanish phoneme and their segmental characteristics (height, frontness, and roundness of vowels; place, manner, and voicing for consonants) were analyzed. As well as the aforementioned characteristics, the phonetic realization(s) of each of these phonemes in different contexts were studied. When necessary, the differences between the target Spanish sounds and the most similar and/or problematic L2 English sounds were discussed. Third, learners also analyzed their own speech in Praat (

Boersma and Weenink 2009) in exercises such as identifying their vowel’s F1 and F2 in spectrograms or measuring their Voice Onset Time values in spectrograms of stop consonants. Finally, they interviewed a Spanish speaker from a Spanish-speaking country for their final group projects. The datasets from these two groups came from an assignment at the beginning and at the end of the semester.

However, the HPVT-Her and HPVT-L2 groups followed the High Phonetic Variability Method. Participants of these groups were exposed to speech that varied by dialect, sex, length of utterance, rhythm of utterance, and audio conditions. The majority of these recordings were extracted from the website es.forvo.com (

Forvo Media 2007). On this website, internet users can upload recordings of any word in Spanish (among other languages), and each entry includes at least one recording of the word in isolation. Usually, entries of more frequent words include multiple recordings of the word in isolation, as well as recordings of the word in a phrase, including set phrases and proverbs. Each entry specifies the gender and nationality of the speaker who has uploaded it. Students were exposed to these recordings in the lecture portion of the class, which took approximately 40 min. Each example of a word containing the target sound of the lesson featured a recording, which the instructor played and asked students to repeat. Thus, if a sound had three different words as examples, students heard three different people pronouncing the sound, and they repeated their utterances. In order to practice with the target sounds, students often completed group activities like finding three different recordings of five words in Forvo (

Forvo Media 2007), repeating them, and then writing a story containing these words to later recite in class. The LPVT-Her and LPVT-L2 groups were exclusively conducted by the instructor, and the difference in input was reduced both in quantity and variability. Participants were exposed to a number of recordings to reflect dialectal differences at the end of the semester, but not every day of instruction as the participants in the HPVT-Her and HPVT-L2 groups were.

2.2.2. Vowels

The vowels under study in this experiment are the Spanish monophthong /e/, a mid-front vowel, and the Spanish diphthong /ei/, which starts as a mid-front vowel and glides into a higher and more fronted position. Spanish is a syllable-timed language that shows the same quality and quantity across syllables regardless of stress placement (

Pike 1945), is not affected by centralization or reduction processes depending on context, and its inventory does not have lax vowels (

Nadeu 2014). On the other hand, English is a stress-timed language that tends to quality and quantity reduction and centralization of vowels in unaccented syllables. It also has a similar number of tense and lax vowels across dialects.

The English vowels show a relatively higher F2 position than Spanish vowels (

Bradlow 1995), and thus, English front vowels /i/ and /eɪ/ are located more peripherally than the Spanish front vowels /i/ and /e/.

Bradlow’s (

1995) results also showed that General American English /eɪ/ tends to have a lower F1 value than Spanish /e/. A comparison between the Spanish and English data of

Bradlow (

1995) (

Table 3) shows that the closest American English vowel to Spanish /e/ (in CVCV sequences) in terms of F1 is English /eɪ/ (both in CVC and CVCV sequences), whereas the closest in terms of F2 is English /ɛ/ in CVC sequences and English /ɪ/ in CVCV sequences. These results mirror the assimilation of these vowels by native Spanish speakers to their native Spanish categories (

Escudero and Chládková 2010), in which American English /ɪ/ and /ɛ/ were within the 2σ ellipse values of native Spanish /e/.

As

Díaz and Simonet (

2015) mention, it could be the case that both Spanish /e/ and /ei/ are assimilated to English /eɪ/, triggering the diphthongized pronunciation of both sounds. Garcia de las

Bayonas (

2004) explained that the diphthongized English /eɪ/ is closer to /e/ than any other monophthong vowel (like /ɛ/), which could lead to interferences.

2.3. Procedure

Before the data were collected, participants signed a consent form that was written in English. The data were collected in two ways: first, the datasets of the HPVT-Her, HPVT-L2, LPVT-Her, and LPVT-L2 groups were part of two compulsory homework assignments for the SPAN 303 course. The assignments were completed at the beginning (pre-test) and end (post-test) of the semester, and they rendered two identical datasets, containing a background questionnaire, three oral production tasks (which were not analyzed in this paper), and the perception t under study in this paper. The researcher, who was the instructor of section A of SPAN 303 (HPVT training), collected the datasets of the HPVT-Her and HPVT-L2 groups. The datasets of the LPVT-Her and LPVT-L2 groups were collected by the instructor of section B of SPAN 303 (LPVT training) and sent to the investigator. Second, the datasets of the control participants were collected by the investigator in the Phonetics and Phonology Laboratory at the University of Illinois. The control group met with the investigator once, at the middle of the semester. The analysis of the data took place after the semester ended. The background questionnaire and the perception task are explained below.

2.3.1. Background Questionnaire

Participants completed two background questionnaires. One at the end of the pre-test, and one at the end of the post-test. The first questionnaire provided information on the participants’ linguistic background, experience with Spanish, daily use, and exposure to it. Participants also self-reported their proficiency in Spanish pronunciation, which aspects of Spanish pronunciation they find most challenging, and their opinion about their performance on the tasks. As the data were collected from intact classrooms, this information was used to equalize the sample, as well as to determine if students needed to be discarded from the sample. Those students who spoke another language at home (e.g., Tamil, Kannada) and/or who did not complete both sessions were not considered for this experiment. In total, 15 students were discarded. The second questionnaire was a shorter version of the first one: participants only responded to questions regarding their performance post-test.

2.3.2. ABX Perceptual Discrimination Task

In this task, participants heard a minimal pair produced by a native speaker of Spanish (words AB) and later heard one of these words produced by another native speaker (word X). Identification data were not obtained in this study due to the higher cognitive load of that type of task (

Flege et al. 1994;

Strange and Shafer 2008). An ABX task combines short memory and non-linguistic processing of sounds, but due to the large number of stimuli and its memory-heavy component, this forces participants to retrieve their categorical knowledge (

Cavar et al. n.d.). The recordings came from 7 native speakers of Spanish from Spain and El Salvador. Two of these speakers were male and five were female. The sequence of speakers was randomized, and participants heard sequences of male-female, female-male, female-female, and male-male. The words used were 20 real target words that elicited 10 minimal pairs (

Appendix A). For each participant, 80 perception tokens were analyzed. Each token was coded by segment, word, testing time, instruction type of the participant, and Spanish language status. Both the pre-test and the post-test had the same /e-ei/ pairs due to the small number of contrastive pairs in the Spanish language.

Participants completed the task in SurveyGizmo, where they were prompted to choose which word the second speaker repeated. For each sequence of ABX, there was a 100-millisecond gap between words A and B, and a 150-millisecond gap between words B and X. The stimuli were divided in two blocks, and there was a question between blocks that asked participants to click “A” to test their attention. None of the words appeared in written form to avoid orthographic bias. Participants heard each target minimal pair sequence twice, and each word of the vowel pair had an allocated sequence, in which it was the correct answer. Participants did not receive feedback.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed with a mixed effects logistic linear regression (glm, package lme4,

Bates et al. 2015) in which the dependent variable was response, coded as “1” for correct and “0” for incorrect. The fixed factors were the segment (/e

/ and /ei/), group (HPVT and LPVT), testing time (pre-test and post-test), position of the segment in the word (penultimate syllable vs. ultimate syllable), and Spanish language status (control primary vs. heritage vs. L2). The random factors were participant and word. Two analyses were carried out for this experiment. First, a regression was run to see whether there was a difference in perception between the control group of primary Spanish speakers, the heritage group, and L2 groups as a whole. In this analysis, segment and Spanish language status were the fixed factors. The second regression focused on the effect of instruction on the heritage and L2 learners only, to see whether instruction and the type of instruction had had an effect on the perception of the difference between

/e

/ and /ei/ in both groups. The data of heritage learners were further analyzed individually to see whether patterns arose in the small sample.

The data for this study were analyzed in three steps: first, the heritage and L2 groups were compared to see how the perception of the learner groups differed from the control group of primary Spanish speakers, with a focus on whether there were differences by segment. Secondly, the learner groups were analyzed to see whether High Phonetic Variability Training had a specific effect in the perception of learners from the pre-test to the post-test. Finally, and due to the small size of the heritage sample, heritage learners were analyzed individually to see whether any patterns arose.

4. Discussion

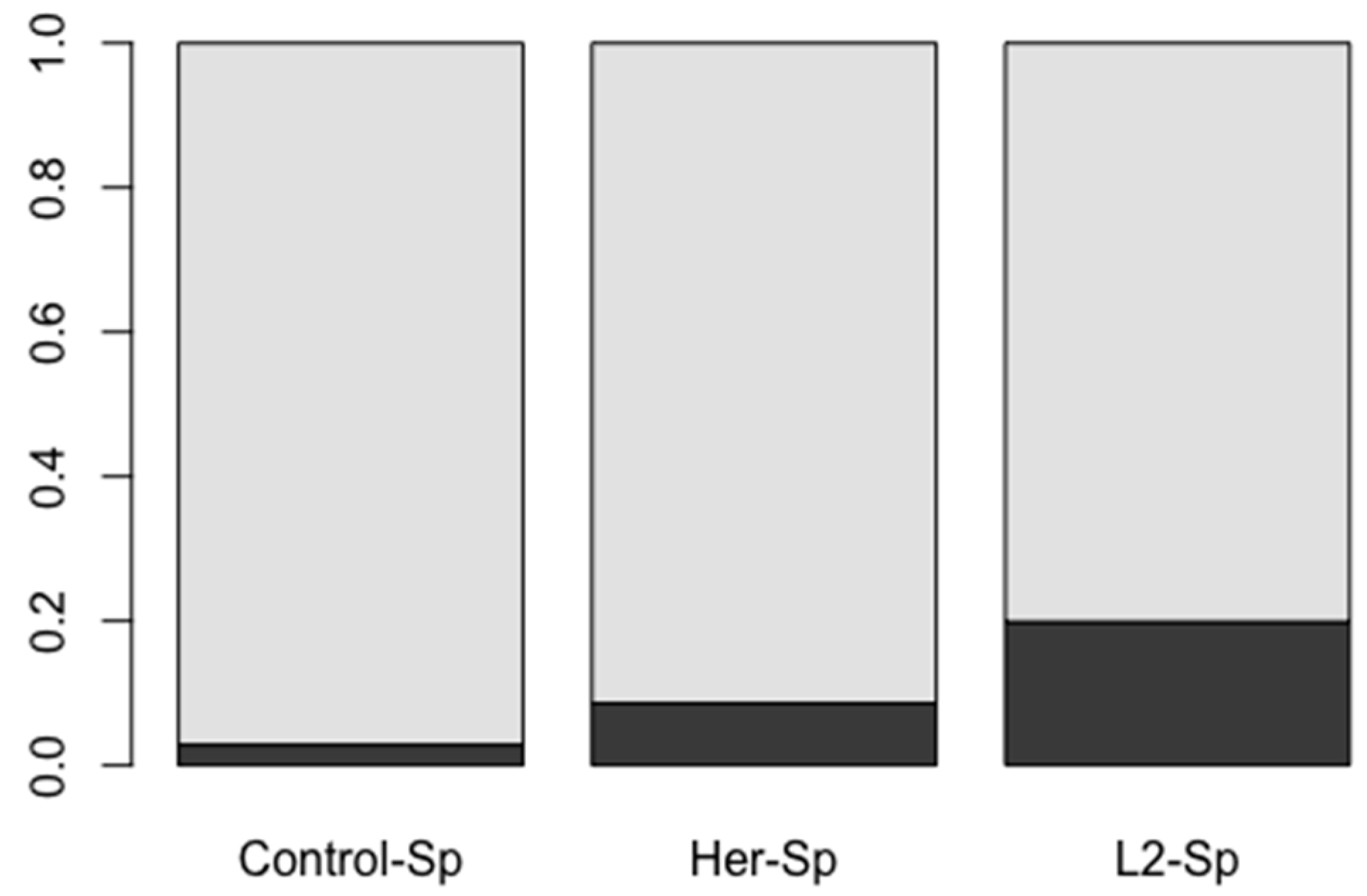

The findings of this study show that, generally, heritage and L2 learners of Spanish are capable of perceptually discriminating between the Spanish monophthong /e/ and the diphthong /ei/ across different minimal pairs and of separating them into categories. These minimal pairs include both lexical and paradigmatic contrasts of meaning, and learners are able to attune their perceptual skills to ascertain the acoustic characteristics of a segmental contrast that does not occur in their primary language, English. The malleability of the perceptual categories of English /e/ into the perceptual separation of Spanish /e/ and /ei/ also aligns with one of the main assumptions of the SLM—that the capacities for speech acquisition remain adaptive over the life span (

Flege 1995,

2003). In particular, heritage learners of Spanish are more accurate at distinguishing the contrast than L2 learners (91.39% accuracy vs. 80.14% accuracy). When compared to a baseline of control speakers whose primary language is Spanish (97.14% accuracy), heritage learners did not significantly differ from them, while L2 learners did. These results concur with the notion that heritage phonology is one of the aspects that is most resistant to change: as

Chang (

2016, p. 805) mentions, “there is something special about childhood linguistic experience with respect to the knowledge of language that is acquired during this time period”.

Explicit instruction also rendered more accurate results after post-test for all learning groups, but the success was different by group and instruction type. Both groups of heritage learners performed better than both groups of L2 learners. However, the increase in accuracy from the pre-test to the post-test for both HPVT groups was higher than for LPVT groups. The particular increase in accuracy in discriminating between Spanish /e/ and /ei/, attained by the participants exposed to High Phonetic Variability Training, supports the hypothesis that exposure to multiple sources of speech can aid in the development of perceptual skills. This is consistent with the results of

Kingston (

2003);

Lambacher et al. (

2005);

Aliaga-Garcia and Mora (

2007); and

Carlet and Cebrian (

2014). This increase in accuracy in the discrimination between Spanish /e/ and /ei/ by heritage learners in the HPVT group has some especially compelling results: these learners improved in the perception of this contrast from 91.25% in the pre-test to 96.25% in the post-test, which is only 0.89% below the native control average. These results could suggest that HPVT has allowed for the generalization of the contrast to occur for these learners. This process conforms to a category shift from a perceptual task to a representational task (

Escudero and Boersma 2004;

Escudero 2005,

2009); that is, the perceptual mapping of the learners has changed to allow for the learning of the contrast to be distributed.

Although not at the level of control speakers or heritage learners, the increase in accuracy of L2 learners exposed to HPVT also indicates a higher benefit than from the low variability common in standalone phonetics courses. L2 Spanish learners in the HPVT section improved by 5%, at the same rate as heritage learners in the HPVT section. Both groups in the LPVT group improved 2% from the pre-test to the post-test. A possible explanation for this difference is reported in

Guion-Anderson (

2013): it is possible that both groups have reoriented their attention to the relevant acoustic cues of /e/ and /ei/; but it is likely that the LPVT group has not been able to develop the ability to process and generalize these cues due to the lack of variability in the input. These significant improvements in the HPVT group, as well as the difference from the LPVT groups, show that High Phonetic Variability Training aids learners in acquiring these sounds at the category level, rather than in acquiring them based on specific exemplars (

Bradlow 2018).

Examining the segments under study from the perspective of different speech perception theories, Spanish /e/ and /ei/ would fall into a single-category assimilation case under the Perceptual Assimilation Model (

Best 1995;

Best and Tyler 2007), and they would both be classified as similar segments to English /e/ under equivalence classification within the Speech Learning Model (

Flege 1995,

2003). Both classifications consider the establishment of Spanish categories to be dependent upon their association to native sounds. The results of this study do not find a significant difference in discrimination accuracy when the response is /e/ or when the response is /ei/. With that said, the categorization of these sounds could occur in two ways: (a) the assimilation of Spanish /ei/ to English /eɪ/, with the assimilation of Spanish /e/ to English /ɛ/, or (b) the formation of a separate category altogether. In the case of L2 learners, even though improvements are observed, these do not occur at the level of control speakers. It is likely that the first scenario is taking place. In the case of heritage learners, the second scenario could be possible, as could the recurrence of Spanish categories acquired in infancy. The results from the heritage learners also concur with Cognitive Phonology (

Fraser 2006) in that it seems that they have been able to keep /e/ and /ei/ “mentally distinct” (

Fraser 2006, p. 69), as is appropriate for the Spanish language.

Therefore, these findings seem to support the hypotheses of all research questions: the hypothesis of research question 1 is confirmed: even though control primary Spanish speakers are slightly more accurate than heritage learners in the perceptual discrimination of Spanish segments /e/ and /ei/, this difference is not significant, and both control speakers and heritage learners of Spanish reach at ceiling accuracy levels. Regarding research question 2, the hypothesis is also confirmed: heritage learners are significantly more accurate at perceiving the Spanish /e/-/ei/ contrast than L2 learners. Although the perception of this contrast by foreign language learners is accurate approximately three times out of four, they do not discriminate the difference at ceiling or near ceiling as do the control and heritage groups. The exposure to a variety of sources of Spanish in an advanced upper-level course and a notable improvement from pre-test to post-test does not guarantee that L2 learners will achieve native-like perceptual mapping of the contrast, and further learning or experience should be necessary.

The findings for these hypotheses demonstrate that heritage learners are not the traditional language learner, and that in this case, they do not differ from speakers who speak Spanish as a primary language. On account of this, the question arises: is HPVT truly beneficial for learners, or is their performance based on the early acquisition and solidification of the vocalic categories of their first language? With that in mind, a case-by-case analysis (

Table 6) is necessary. As mentioned before, seven out of the nine heritage learners showed improvement from the pre-test to the post-test. The improvement of the seven participants ranged from 3.75% to 8.15%, with an average of 6.34%. Considering these learners by the type of instruction there were exposed to, the two participants from the LPVT group who improved (025, and 031) did so by 7.5%. The average improvement for the HPVT group participants was lower, at 5.88%. These results suggest that heritage learners exposed to LPVT benefit more from it than those exposed to HPVT. Nevertheless, the participants who improved less than 7.5% in the HPVT group (007, 026, and 033), regardless of their improvement percentage, all improved to 100%. The two participants in the LPVT group who improved did not reach ceiling levels in the post-test. The propitious conditions of these learners could have led to improvement towards complete accuracy: these learners are high-proficiency learners who are either majoring or minoring in their heritage language, who receive consistent and varied input combined with instruction, in this course and others. These conditions can lead to becoming “fully fluent, and in some cases, indistinguishable from native speakers in many aspects of their grammar” (

Montrul 2015, p. 210). That is why early acquisition is not enough to explain the advantage of heritage learners in phonology. The quantity and quality of the input and the continued use of language—as in the example from

Shea (

2019), in which participants come from the Chicagoland area, where Mexican and other Latinx communities allow for a large density of interactions in Spanish—could have an effect on how aspects of heritage learners’ linguistic knowledge fully develop (

Kim 2020;

Montrul 2015).

Another matter that needs to be addressed after individual analyses are the two participants whose accuracy decreased. Participant 016, enrolled in the HPVT group, went from 100% accuracy in the pre-test to 97.5% in the post-test. The decrease in accuracy is low. However, participant 002, enrolled in the LPVT group, decreased her accuracy from 87.5% in the pre-test to 77.5% in the post-test. A possible reason for this decrease could be the mismatch in the acquisition process; that is, the phonology of the baseline language is acquired naturalistically, whereas the re-learning process takes place in a classroom and is a formal process (

Polinsky 2015). Another possibility is that, for these participants, this contrast has undergone phonological structural simplification. This simplification has been observed in complex segments, such as diphthongs (

Shea 2019) which is the case with /ei/, and it has also been observed in other linguistic structures like pidgins and creoles, which tend to have monophthong vocoids (

Nichols 2009), although not always (

Klein 2006). Heritage learners whose performance deviates from monolingual native norms usually do so because of differences in experience and proficiency (

Au et al. 2002;

Shea 2019). Although these learners were enrolled in an upper-level course in the Spanish curricula, the level of the students varies. The individual analyses show us that heritage learners are not a monolith, and that formal instruction can affect them differently. Conversely, combining the HPVT results with the fact that the course focused on all Spanish sounds, and the fact that the instruction of vowels and the /e/-/ei/ difference was conducted in three class sessions within the semester, these findings suggest that the effect of high phonetic variability training is robust.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to contribute to the present literature on heritage language acquisition by demonstrating that explicit phonetic instruction, and particularly, High Phonetic Variability Training, can be beneficial in the re-learning of the phonology of the first language. The findings in this study have implications for both linguistic research and pedagogical applications. Firstly, these findings confirm that heritage learners’ perceptual mapping of their first language’s phonology is generally robust and can be maintained regardless of a shift in language dominance from Spanish into English. However, a number of learners show a level of perceptual accuracy midway between that of monolingual native speakers and that of L2 learners. Secondly, these findings show that when learners are not completely native-like in perception, the application of certain pedagogical training types in class, particularly instruction in which learners are exposed to a range of speakers and dialects, can help learners in the development of their perceptual skills from phonetic exemplars to the generalization of phonological categories (

Bradlow 2018), thus reaching native-like perceptual mapping. A significant increase in accuracy and native-like levels in the post-test by heritage learners enrolled in HPVT supports this. Therefore, even though heritage learners already have a strong perceptual system for their heritage language, these findings suggest that near ceiling perceptual performance can still be improved to at-ceiling perception with explicit classroom instruction and exposure to variability in speech.

These findings shed light on the perception of heritage sounds and their development through classroom instruction. It is important, however, to recognize the shortcomings of this study: first of all, as participants were recruited from real, intact classes, the number of heritage learner participants in this study is not high enough to fully confirm the presented hypotheses. Instructors were also assigned to those classes before the study. The difference in the instructors’ linguistic backgrounds, one being a native speaker of Spanish, and the other an advanced non-native speaker, could have resulted in different vocalic models for students. Another issue that could challenge the necessity of a study such as this is the low functional load of the /e/-/ei/ contrast: there are very few minimal pairs with this contrast, and most are lexical. The minimal pairs that present paradigmatic contrasts only work in the dialect of Northern and Central Spain, where the second person plural is spoken using vosotros, thus creating pairs like ves-veis. Studies on vowels with higher functional loads or consonants that tend to have transfer effects from English combined with HPVT could inform us even further on heritage language phonology and instruction. Despite these shortcomings, these findings offer us some preliminary data from which to extend the analysis to larger groups of participants, and they offer a glimpse into what could be achieved in explicit phonetic instruction courses to maximize the learning opportunities for learners who are oftentimes ignored in curriculum design. It is essential to note that the SPAN 303 course covers all consonantal and vocalic segments of Spanish, as well as some suprasegmental aspects. Yet participants who in the entire semester were instructed on the /e/-/ei/ contrast three times were able to enhance their perception in a very short amount of time.

This study focuses on the perception of the Spanish /e/-/ei/ contrast and on how explicit phonetic instruction like HPVT can aid in the development of perception. In order to understand the phonological system of heritage learners, it is imperative to see if the gains in perception by means of HPVT can also occur in production. In a study on the differences between the perception and production of Spanish lexical stress by heritage learners,

Kim (

2020) found that while perception was comparable to monolingual native levels, production digressed from monolingual native production values. It appears that production requires more experience in the heritage language (

Chang 2016) and is dependent upon the similarity of the primary and heritage languages’ sounds (

Godson 2003,

2004). Observing the positive effects of HPVT on speech perception, it would be interesting to see whether its facilitating scope also extends to speech production in future studies.