Abstract

This study documents and accounts for the behavior of the place of articulation of latent segments in the Panoan languages Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua. In these languages, the lexical category of the word governs the place of articulation (PoA) of latent consonants. Latent segments only surface when they are syllabified as syllable onsets. They surface as coronal consonants when they are part of verbs; but they occur as non-coronal consonants when they belong to nouns or adjectives. In non-verb forms, by default, they are neutralized to dorsal in Shipibo-Konibo, and to labial in Capanahua. The analysis proposed consists in using the well-known markedness hierarchy on PoA, |Labial, Dorsal > Coronal > Pharyngeal|, and harmonically aligning it with a morphological markedness hierarchy in which non-verb forms are more marked than verb forms: |NonVerb > Verb|. This creates two fixed rankings of markedness constraints: one on verb forms in which, as expected, coronal/laryngeal is deemed the least marked PoA, and another one on non-verb forms in which the familiar markedness on PoA is reversed so that labial and dorsal become the least marked places of articulation. The study shows that although both Panoan languages follow the general cross-linguistic tendency to have coronal as a default PoA, this default can be overridden by morphology.

1. Introduction

The goal of this article is to present and account for a rare morpho-phonological interaction found in Panoan languages like Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua: the interplay between word-lexical category and the place of articulation (PoA) of latent segments. In both languages, latent segments surface when they are syllabified as syllable onsets. They are deleted if they were to occur as syllable codas. When they are parsed as onsets, by default, they appear as coronal sounds if they belong to a verb form. However, in non-verb paradigms, latent segments, when parsed as onsets, surface neutralized to dorsal by default in Shipibo-Konibo, and to labial in Capanahua. In order to account for this phenomenon, an analysis is proposed in which the markedness hierarchy on PoA, |Labial, Dorsal > Coronal > Pharyngeal|, is harmonically aligned with a morphological markedness hierarchy in which non-verb forms are more marked than verb forms: |NonVerb > Verb|. As a result, two fixed rankings of markedness constraints are obtained, one on verb forms in which, as expected, coronal/laryngeal is deemed the least marked PoA, and another one on non-verb forms in which the familiar markedness on PoA is reversed so that labial and dorsal become the least marked places of articulation. The analysis not only brings into focus the possibility to reverse the PoA markedness due to morphological factors but also points out to the existence of noun-positional markedness constraints.1

The study is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the main phonological characteristics of Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua relevant to the data discussed in the subsequent sections. These include their segmental inventories with particular attention to glottal stops and the placeless nasal /N/, their syllable structure and the stress patterns. Section 3 offers comprehensive evidence for the existence of latent consonants in the final position of non-verb roots, verb roots and suffixes. The evidence is drawn from stress, syllabification and the interaction between them. Section 4 presents detailed data describing the behavior of the PoA of latent segments in verb and non-verb forms as well as in suffixes. Section 5 shows that the placeless nasal /N/ when it surfaces in the onset position presents the same patterns of PoA that latent segments show. Section 6 discusses the evidence available for latent segments in adverb roots. Section 7 provides an account for the behavior of the PoA in latent segments as they appear in different lexical categories. Finally, Section 8 summarizes the proposal and discusses their theoretical relevance in terms of the existence of noun-positional markedness constraints and the reversal of the place markedness hierarchy due to morphological factors.

2. Phonological Outline

Shipibo-Konibo (ISO-639-3: shp) and Capanahua (ISO-639-3: kaq) are two Panoan languages spoken in the Peruvian Amazon. While the former is relatively healthy in terms of children learning the language and the number of speakers it has (about 22,500 speakers—Eberhard et al. 2020), Capanahua is highly endangered (fewer than 100 fluent speakers—Eberhard et al. 2020). Both languages have similar segmental inventories and phonotactics (Elias-Ulloa 2004, 2009, 2011; Loos 1969; Loos and Loos 1998; Loriot et al. 1993; Valenzuela et al. 2001). They both have the same vowels: /a, i, ɨ, ʊ/. Their consonants are: /p, t, k, ʔ, m, n, N, β, s, ʃ, ʂ, h, t͡s, t͡ʃ, ɖ͡ʐ, j, w/. The segments /t, t͡s, n, s/ represent dental consonants. A conspicuous difference between Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua is the distribution of the glottal stop. While in Capanahua (Elias-Ulloa 2009), /ʔ/ could appear as part of the first syllable of many roots (e.g., /ʔiʔβʊ/‘owner’, /tʊʔkʊ/‘frog’) and affixes (e.g., /taʔ/(evidential), /-ʔʊ̃/ ‘about’); in Shipibo-Konibo (Elias-Ulloa 2016), the glottal stop has a much more restricted distribution. It can only occur as the first segment of a reduced number of suffixes (/-ʔati/(verbalizer), /-ʔiti/(verbalizer), /-ʔiɖ͡ʐa/(intensifier)).

The segment /N/ represents a nasal that lacks an underlying specification for PoA in the oral cavity. On the surface, when it occurs as a coda, it takes the PoA of the following consonant. If /N/ occurs word-finally, then it is typically realized as a nasal segment with an [ŋ]-like quality or as a muffed nasalized continuation of the preceding vowel, represented by [N]. For instance, the word /βiNpiʃiN/ (sp. of plant), which has two placeless nasals, is realized as: [βĩm.pi.ʃĩN]. The phonetic characteristics of the /N/ realization are not surprising. They have been observed in other languages, like Japanese (Labrune 2012; Tronnier 1996; Yoshida 2003; Youngberg 2018), Caribbean Spanish (Trigo 1988) and Ashaninka (Anderson 1978; Dirks 1953; Mihas and Maxwell 2019), in which the /N/ nasal has been reported to occur. Yamane (2013), for instance, carried out an ultrasound study of the phonetic realization of/N/in Japanese and found that in general, its realization involves a significant dorsum raising, which explain the [ŋ]-like quality perceived during its production. de Lacy (2002, 2006) proposes to distinguish between two types of nasal segments that lack a specification for PoA in the oral cavity: a nasalized glottal stop; and a nasalized glottal continuant, which, based on McCawley (1968), is reported to be usually phonetically realized as a nasal continuation of the preceding vowel or as a velar or uvular nasal. The latter is quite close to the behavior for /N/ observed in Shipibo-Konibo/Capanahua. In this study, I will continue to use the [N] symbol to denote the output correspondent of the placeless nasal /N/ in word-final position, independently of how it is phonetically realized. In terms of phonological features, I assume /N/ is minimally specified as [+consonantal, +sonorant] and [+nasal]. Crucially, it lacks the [–continuant] feature present in other nasals, and a specification for PoA within the oral cavity.

The occurrence of [N] on the surface is restricted to appear in coda position in both Panoan languages and it is in complementary distribution with /m/ and /n/, which are only found in the onset position of syllables (Section 5 describes what happens when /N/ is followed by a vowel and, therefore, resyllabified as an onset). A conspicuous characteristic of [N]-coda is that it completely nasalizes all vowels and glides around it. This phenomenon is responsible for the nasalized vowels observed in both languages: [ã, ĩ, ɨ̃, ʊ̃]. The words shown in (1) are shared by both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua.2

| (1) | a. | /βinʊN/ | → | [βi.ˈnʊ̃N] | ‘aguaje (sp. of fruit)’ |

| b. | /jaja -N/ | → | [j̃ã.ˈj̃ãN] | ‘woman’s mother-in-law’ (ergative) | |

| c. | /jʊkaN/ | → | [jʊ.ˈkãN] | ‘guava’ | |

| d. | /wɨaN/ | → | [w̃ɨ̃.ˈãN] | ‘brook’ |

In both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, the preferred syllable structure is an onset consonant followed by a vowel. However, it is possible to find onsetless syllables and syllables with a coda consonant. Complex syllabic margins are forbidden. Only the sibilant fricatives /s, ʃ, ʂ/ and the nasal /N/ are allowed in the coda position of the syllable. In addition to those sibilants and the nasal /N/, Capanahua allows the glottal stop as a syllable coda. See data in in (1) and (2).

| (2) | a. | [ˈwi.sʊ] | ‘black’—Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| b. | [ˈkɨ.ʊ.ti] | ‘to howl’—Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua | |

| c. | [ˈmɨs.kʊ.ti] | ‘to blend’—Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua | |

| d. | [ˈmaʃ.pi] | ‘head warts’—Shipibo-Konibo/‘horn, crest’—Capanahua | |

| e. | [wi.ˈɖ͡ʐiʂ] | ‘thin’—Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua | |

| f. | [ˈtɨʔ.wɨ.ti] | ‘to limp’—Capanahua |

Both languages display a main-stress window formed by the first two syllables of the word. Main stress falls on the second syllable if it is closed; otherwise, it falls on the first syllable. Stressed syllables receive a high pitch (Elias-Ulloa 2000, 2005, 2011).

| (3) | a. | /nɨtɨ/ | → | [ˈnɨ.tɨ] | ‘day’—Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| b. | /miskʊ/ | → | [ˈmis.kʊ] | ‘cramp’—Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua | |

| c. | /t͡ʃikiʃ/ | → | [t͡ʃi.ˈkiʃ] | ‘lazy’—Shipibo-Konibo | |

| d. | /tɨpaʃpi/ | → | [tɨ.ˈpaʃ.pi] | ‘beard’—Capanahua |

This pattern is robust in both languages. When the roots receive suffixes that change the structure of the final syllable, the main stress shifts accordingly. This can be seen in the data in (4). In the bare forms in (4.a–b), the main stress falls on the first syllable since the second one is open. Both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua have a suffix that attaches to non-verb forms to mark ergative, locative, instrumental. This suffix has two underlying forms, /-N/ and /-aN/, and the former is used with roots that end in a vowel and the latter, with those roots that end in a consonant.3 The /-N/ allomorph turns the final open syllable of the roots in (4.a–b) into closed syllables. Therefore, the main stress is now attracted to the second syllable (see the third column). In (4.c–d), the main stress falls on the second syllable in the bare forms because those syllables are closed. Since those nouns end in a consonant, they receive the /-aN/ allomorph,4 which turns the second syllable of the resulting form into an open one and, as expected, this time the main stress occurs on the first syllable of the word (see the third column of the forms in (4.c–d)).

| (4) | UR | Bare form | /-N/form | Gloss. |

| a. | /βakɨ/ | [ˈβa.kɨ] | [βa.ˈkɨ̃N] | ‘child, son’ Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| b. | /ɖ͡ʐani/ | [ˈɖ͡ʐa.ni] | [ɖ͡ʐa.ˈnĩN] | ‘hair’ Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| c. | /t͡ʃʊɖ͡ʐiʃ/ | [t͡ʃʊ.ˈɖ͡ʐiʃ] | [ˈt͡ʃʊ.ɖ͡ʐi.ʃĩN] | ‘hard’ Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| d. | /pʊβɨʂ/ | [pʊ.ˈβɨʂ] | [ˈpʊ.βɨ.ʂɨ̃N] | ‘scabies on the arm’ Capanahua |

As shown in (4), main stress never goes beyond the first two syllables of the word. The only exception to this pattern is nouns in vocative case. The vocative requires the main stress to be located on a vowel that must be at the very end of the word. If the root ends in a vowel, that vowel receives the main stress. If it ends in a consonant, then the vowel [a] is inserted as a hosting site to the main stress. This is illustrated in the data in (5).

| (5) | UR | Bare form | Vocative form | Gloss. |

| a. | /βakɨ/ | [ˈβa.kɨ] | [βa.ˈkɨ] | ‘child, son’ Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| b. | /kʊka/ | [ˈkʊ.ka] | [kʊ.ˈka] | ‘uncle’ Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| c. | /ʂʊNtakʊ/ | [ˈʂʊ̃n.ta.kʊ] | [ʂʊ̃n.ta.ˈkʊ] | ‘young woman’ Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| d. | /atapa/ | [ˈa.ta.pa] | [a.ta.ˈpa] | ‘hen, chicken, rooster’ Shipibo-Konibo |

| e. | /βaʃʊʃ/ | [βa.ˈʃʊʃ] | [βa.ʃʊ.ˈʃa] | (sp. of caterpillar) Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua |

| f. | /kamʊʂ/ | [ka.ˈmʊʂ] | [ka.mʊ.ˈʂa] | (sp. of snake) Shipibo-Konibo |

3. Evidence for Latent Segments

3.1. In Non-Verb Roots

The origin of latent segments in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, and in Panoan languages in general, is an old phonological process of vowel deletion that took place in Proto-Pano (Loos 1973; Shell 1985). As part of this phenomenon, trisyllabic roots underwent apocope. The loss of that final vowel resulted, synchronically, in several bisyllabic words that end in a coda consonant, which was originally the onset of the dropped vowel. The data in (6) show words that end in a sibilant or a nasal in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua. The first column shows their reconstruction in Proto-Pano (Shell 1985).

| (6) | Proto-Pano | Shipibo-Konibo | Capanahua | Gloss. | |

| a. | *mɨ.t͡si.si | mɨ.ˈt͡sis | mɨ̃n.ˈt͡sis | ‘finger nail’ | |

| b. | *βaʔ.ki.ʃi | βa.ˈkiʃ | βaʔ.ˈkiʃ | ‘yesterday, tomorrow’ | |

| c. | *ʔʊʔ.pʊ.ʂɨ | hʊ.ˈpʊʂ | ʔʊʔ.ˈpʊʂ | ‘nigua’ (sp. of flea) | |

| d. | *ʔa.mɨ.nʊ | a.ˈmɨ̃N | ʔa.ˈmɨ̃N | ‘capybara’ (sp. of rodent) | |

| e. | *βɨ.tɨ.mɨ | βɨ.ˈtɨ̃N | βɨ.ˈtɨ̃N | ‘fish stew’/‘soup’ |

Among Panoan languages, Chácobo is characterized by having preserved most of the third syllables in words that were reduced to bisyllables in other Panoan languages. It has been invaluable to the reconstruction of the final lost syllable in Proto-Pano. The data in (7) show the Chácobo cognates of the words in (6).

| (7) | Proto-Pano | Chácobo | Gloss. | |

| a. | *mɨ.t͡si.si | mɨ́.t͡si.si | ‘fingernail’ | |

| b. | *βaʔ.ki.ʃi | βa.kí.ʃi | ‘yesterday, tomorrow’ | |

| c. | *ʔʊʔ.pʊ.ʂɨ | hʊ.pɨ́.ʂɨ | ‘nigua’ (sp. of flea) | |

| d. | *ʔa.mɨ.nʊ | ʔa.mɨ́.nʊ | ‘capybara’ (sp. of rodent) | |

| e. | *βɨ.tɨ.mɨ | βɨ.tɨ́.mɨ | ‘food’ |

In the examples above, the consonant left at the end of the bisyllabic words after the deletion of the final vowel is a sibilant or a nasal. Both types are consonants that Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua deem licit to occupy the coda position of their syllables. The data in (8), however, show that when final vowel deletion could have left a consonant at the end of the word that was not an acceptable syllable coda, the resulting word in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua displays a final open syllable. Although we cannot see the final underlying consonant in the resulting words, I will demonstrate shortly that it is present as a latent segment.

| (8) | Proto-Pano | Shipibo-Konibo | Capanahua | Gloss. | |

| a. | *tɨ.tɨ.pa | tɨ.ˈtɨ | tɨ.ˈtɨ | (sp. of falcon) | |

| b. | *ʂa.ka.ta | ʂa.ˈka | ʂa.ˈka | ‘skin, peel’ | |

| c. | *ma.pʊ.ka | ma.ˈpʊ | ma.ˈpʊ | ‘clay’ | |

| d. | *kwɨ.βi.t͡ʃi | kɨ.ˈβi | --- | ‘lower lip’ | |

| e. | *ʔa.wa.ra | a.ˈwa | ʔa.ˈwa | ‘tapir’ |

Once again, Chácobo was not affected by this phenomenon and shows the third syllable lost in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua. See data in (9).

| (9) | Proto-Pano | Chácobo | Gloss. | |

| a. | *tɨ.tɨ.pa | tɨ.tɨ́.pa | (sp. of falcon) | |

| b. | *ʂa.ka.ta | ʂa.ká.ta | ‘skin, peel’ | |

| c. | *ma.pʊ.ka | má.pʊ.ka | ‘clay’ | |

| d. | *kwɨ.βi.t͡ʃi | kɨ.βí.t͡ʃi | ‘lip’ | |

| e. | *ʔa.wa.ra | ʔá.wa.ra | ‘tapir’ |

Synchronically, apocope is no longer a productive phenomenon in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua. As shown in (10), native words and loanwords with more than two syllables have been incorporated into those languages, and their final third syllable is always kept.

| (10) | a. | ʊ.ˈt͡ʃi.ti | ‘dog’ |

| Shipibo-Konibo (loanword from Arawakan languages) | |||

| b. | is.ˈpã.j̃ʊ̃.ɖ͡ʐʊ | ‘Spanish’ | |

| Shipibo-Konibo (loanword from Spanish) | |||

| c. | ˈʔa.ta.pa | ‘chicken, hen, rooster’ | |

| Capanahua (loanword from Arawakan languages) | |||

| d. | ˈʂʊ̃n.ta.kʊ | ‘young woman’ | |

| Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua (native word) | |||

Now let us further examine the cases where the final consonant left after the apocope is not a permissible coda (namely, it is neither [s, ʃ, ʂ] nor [N]). As observed in (8), when that happens, the final consonant does not appear on the surface form. However, it is still synchronically part of the underlying representation of the word. Three pieces of evidence support this statement: (i) main stress assignment, (ii) resyllabification, and (iii) the interaction between main stress and resyllabification.

Let us examine each supporting piece of evidence. Section 2 established that in Panoan-languages like Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, the main stress falls on the word-initial syllable by default ([ˈnɨ.tɨ] ‘day’), unless the second syllable is closed. In that case, the main stress appears on the second syllable ([nɨ.ˈpaʂ]—sp. of aquatic plant). As observed in the data in (8), although the final consonant does not surface,5 the main stress occurs on the second syllable signaling the presence of a latent consonant at the end of the word. The presence of a latent coda creates a case of opaque stress assignment; that is, the stress falls on the second syllable because it is closed; but on the surface, we do not see any segmental trace of the latent consonant (e.g., /awaC/→ [a.ˈwaC] → [a.ˈwa] ‘tapir’). The uncharacteristic assignment of the main stress in those cases serves as a reminder that the word ends in a closed syllable. The data in (11) show the underlying representation of the forms presented in (8) for Shipibo-Konibo. The C at the end of the roots stands for the latent consonant.

| (11) | UR | Surface form | Gloss. | ||

| a. | /tɨtɨC/ | → [tɨ.ˈtɨC] | → | [tɨ.ˈtɨ] | (sp. of falcon) |

| b. | /ʂakaC/ | → [ʂa.ˈkaC] | → | [ʂa.ˈka] | ‘skin, peel’ |

| c. | /mapʊC/ | → [ma.ˈpʊC] | → | [ma.ˈpʊ] | ‘clay’ |

| d. | /kɨβiC/ | → [kɨ.ˈβiC] | → | [kɨ.ˈβi] | ‘lower lip’ |

| e. | /awaC/ | → [a.ˈwaC] | → | [a.ˈwa] | ‘tapir’ |

For comparison, in the data in (12.a–b), we can see the behavior of the stress when the root ends in a vowel. In this case, the stress appears on the initial syllable since the second one is open in all the stages of representation. In contrast, the data in (12.c–d) show cases in which the root ends in a consonant that is deemed licit to surface as a syllable coda. In those cases, just as it did in the data in (11), the stress appears on the second syllable since it is closed.

| (12) | UR | Surface form | Gloss. | |

| a. | /βakɨ/ | → | [ˈβa.kɨ] | ‘child’ |

| b. | /ʂata/ | → | [ˈʂa.ta] | (sp. of poisonous plant) |

| c. | /βakiʃ/ | → | [βa.ˈkiʃ] | ‘yesterday, tomorrow’ |

| d. | /maʂaʂ/ | → | [ma.ˈʂaʂ] | ‘rubble’ |

The second piece of evidence that there is a latent consonant at the end of words like those in (11) comes from resyllabification. When the latent segment is resyllabified as a syllable onset, it surfaces as a full-blown consonant. This happens when a vowel, brought through suffixation, is added immediately after the latent consonant. The data in (13) illustrates this through the /-aN/ allomorph discussed in Section 2. All the examples displayed behave as the words in (4.c–d), which end in a consonant (for instance, /pʊβɨʂ -N/→ [ˈpʊ.βɨ.ʂɨ̃N] ‘scabies on the arm’—LOC). The data in (13) comes from Shipibo-Konibo but the same behavior is observed in Capanahua. The latent segment appears in bold. If the underlying forms in (13) did not have a final latent consonant, then we would expect the resulting forms to show the/-N/allomorph immediately after the final vowel of the root, instead of the /-aN/ allomorph, as it was the case in (4.a–b): /βakɨ -N/→ [βa.ˈkɨ̃N] ‘child’.

| (13) | UR | Bare form | /-N/ form | Gloss. |

| a. | /tɨtɨC/ | [tɨ.ˈtɨ] | [ˈtɨ.tɨ.kãN] | (sp. of falcon) |

| b. | /ʂakaC/ | [ʂa.ˈka] | [ˈʂa.ka.kãN] | ‘skin, peel’ |

| c. | /mapʊC/ | [ma.ˈpʊ] | [ˈma.pʊ.kãN] | ‘clay’ |

| d. | /kɨβiC/ | [kɨ.ˈβi] | [ˈkɨ.βi.kãN] | ‘lower lip’ |

| e. | /awaC/ | [a.ˈwa] | [ˈa.wa.kãN] | ‘tapir’ |

Again, for comparison, the data in (14) show both the bare and /-N/ forms of roots that end in a vowel and that end in a licit coda. Once more, those that end in a consonant present the same behavior as those that have a latent consonant.

| (14) | UR | Bare form | /-N/ form | Gloss. |

| a. | /βakɨ/ | [ˈβa.kɨ] | [βa.ˈkɨ̃N] | ‘child’ |

| b. | /ʂata/ | [ˈʂa.ta] | [ʂa.ˈtãN] | (sp. of poisonous plant) |

| c. | /βakiʃ/ | [βa.ˈkiʃ] | [ˈβa.ki.ʃĩN] | ‘yesterday, tomorrow’ |

| d. | /maʂaʂ/ | [ma.ˈʂaʂ] | [ˈma.ʂa.ʂɨ̃N] | ‘rubble’ |

The position of the main stress on the second syllable of a bisyllabic word and the presence of a latent segment are so entangled that loanwords that have final stress are reinterpreted as having a latent segment. The data (15) show examples of this phenomenon in words borrowed from Spanish into Shipibo-Konibo. Their final stress is taken as a cue for the presence of a latent final consonant, which surfaces when it manages to be resyllabified as the onset of a following vowel as in the case of the /-N/ forms.

| (15) | UR | Bare form | /-N/ form | Gloss. |

| a. | /hʊseC/ | [hʊ.ˈse] | [ˈhʊ.se.kãN] | ‘José’ (proper name from/xo.ˈse/) |

| b. | /kahiC/ | [ka.ˈhi] | [ˈka.hi.kãN] | ‘coffee’ (from [ka.ˈfe]) |

| c. | /βaNβʊC/ | [βãm.ˈβʊ] | [ˈβãm.βʊ.kãN] | ‘bamboo’ (from [bam.ˈbu]) |

Nouns in vocative case also make apparent the presence of final latent segments. Remember that the vocative requires the main stress to appear on a vowel that is aligned with the word-right edge. See data set in (5). If the noun ends in a vowel, the main stress occurs on it (/βakɨ -VOC/ → [βa.ˈkɨ] ‘Child!’); if it does not, then the vowel [a] is inserted so the main stress can fall on it (/kamʊʂ -VOC/ → [ka.mʊ.ˈʂa]—sp. of snake). The examples from Shipibo-Konibo in (16) show that roots that contain a latent segment also trigger [a]-epenthesis in order to obtain the vocative form. That is, roots with latent segments pattern together with those that have full-blown final consonants.

| (16) | UR | Bare form | Vocative form | Gloss. |

| a. | /tɨtɨC/ | [tɨ.ˈtɨ] | [tɨ.tɨ.ˈka] | (sp. of falcon) |

| b. | /awaC/ | [a.ˈwa] | [a.wa.ˈka] | ‘tapir’ |

| c. | /kapɨC/ | [ka.ˈpɨ] | [ka.pɨ.ˈka] | ‘alligator’ |

| d. | /wɨʂaC/ | [wɨ.ˈʂa] | [wɨ.ʂa.ˈka] | ‘Huexa’ (proper name) |

| e. | /hʊseC/ | [hʊ.ˈse] | [hʊ.se.ˈka] | ‘José’ (proper name) |

The data in (16) can be compared to (17). In the latter, we find roots that end in a vowel or in a consonant that can be a licit coda. They are shown in both their bare and vocative forms. The data in (16) with its latent segments behave as those that have a final consonant in (17.c–d).

| (17) | UR | Bare form | Vocative form | Gloss. |

| a. | /βakɨ/ | [ˈβa.kɨ] | [βa.ˈkɨ] | ‘son’ |

| b. | /tita/ | [ˈti.ta] | [ti.ˈta] | ‘mother’ |

| c. | /t͡ʃaɖ͡ʐaʂ/ | [t͡ʃa.ˈɖ͡ʐaʂ] | [t͡ʃa.ɖ͡ʐa.ˈʂa] | ‘kingfisher’ |

| d. | /hʊnas/ | [hʊ.ˈnas] | [hʊ.na.ˈsa] | ‘Jonas’ (proper name) |

The third piece of evidence for latent segments is the interaction between resyllabification and changes in the position of the main stress. Let us examine the data set presented in (13) in more detail. The main stress occurs on the second syllable in bare forms. However, when the /-aN/ allomorph is added, not only the latent segment is resyllabified as an onset, what deems it licit to surface, but also the main stress jumps back from the second syllable to the word-initial one. This behavior is the same to what was observed in (4.c–d) with bisyllabic roots that have a full-blown final consonant, namely, their second syllable is closed and, therefore, able to attract the main stress. However, once the final consonant is resyllabified as an onset, the second syllable becomes open and consequently, the main stress moves to the initial syllable. If the roots in (13) did not have a latent consonant, it would be completely unexpected why the stress jumps to the initial syllable when the /-aN/ allomorph is added. The examples presented in (18) allow us to observe and compare the pattern just described, in a concise fashion, in a root that ends in a vowel (/mapʊ/), one with a latent segment (/kapɨC/), and one with a final consonant (/βaʃʊʃ/).

| (18) | UR | Bare form | /-N/ form | Gloss. |

| a. | /mapʊ/ | [ˈma.pʊ] | [ma.ˈpʊ̃N] | ‘head’ |

| b. | /kapɨC/ | [ka.ˈpɨ] | [ˈka.pɨ.kãN] | ‘alligator’ |

| c. | /βaʃʊʃ/ | [βa.ˈʃʊʃ] | [ˈβa.ʃʊ.ʃãN] | (sp. of caterpillar) |

Before proceeding to discuss latent segments further, we should consider whether it would not be better synchronically to analyze them as part of suffixes and instead of part of roots. Thus, for instance, why should we not regard /-kaN/ to be the suffix in the data in (13)? I compare the consequences of both proposals in (19). In the alternative analysis, the root for ‘tapir’ would not have a final latent consonant, it would end in a vowel. In order to account for the unexpected position of the main stress on the second syllable, although it is an open syllable; we would have to mark that syllable as bearing an underlying high pitch or as carrying lexical stress. This would account for the form ‘tapir’ takes when it appears in bare form: [a.ˈwá]. However, that analysis would also predict the wrong stress pattern when the ergative suffix is added. Since the latent segment would be analyzed as part of the suffix, then we would have to posit a third allomorph, /-kaN/. The result would be the unattested mapping:/awá -kaN/ → *[a.ˈwá.kãN] ‘tapir’ (ERG). That is, since the root for ‘tapir’ would have a high pitch lexically marked on its second syllable, the position of the main stress would not depend any longer on syllable structure. When the /-kaN/ allomorph is added, the main stress is wrongly predicted to remain on the second syllable since there is no reason to move it.

| (19) | UR | ‘tapir’ | ||

| a. | Analysis proposed in this study | /awaC/ | → | [a.ˈwá] |

| /awaC -N/ | → | [ˈá.wa.kãN] | ||

| b. | Alternative analysis | /awá/ | → | [a.ˈwá] |

| /awá -kaN/ | → | *[a.ˈwá.kãN] |

Furthermore, both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua have actual /-kaN/ suffixes that show that roots like /kapɨC/ ‘alligator’ and /awaC/ ‘tapir’ do have a final latent consonant. Let us examine one of them in Shipibo-Konibo. The /-kaN/ suffix exists and attaches to nouns in verbless clauses to reorient the conversation topic (Valenzuela 2003). For example, when the /-kaN/ suffix is added to the noun /βakɨ/ ‘child’, it results in: [ˈβa.kɨ.kãN] ‘(and what about the) child?’. For the sake of comparison, the data in (20) presents four noun roots, the first one ends in a vowel, the second one ends in a sibilant consonant and the other two roots end in a latent consonant. The data set presents their forms when they occur as bare roots, and then in their /-N/ forms and /-kaN/ forms. In terms of syllable structure and stress position, the three roots with final consonants pattern altogether. Compare the /-N/ form and the /-kaN /form of /kapɨC/ ‘alligator’. Segmentally, they are identical, but they are distinguished by the position of their main stress: [ˈka.pɨ.kãN] ‘alligator’ (ERG) vs. [ka.ˈpɨ.kãN] ‘(and what about the) alligator?’ The difference in the stress placement readily follows from the presence of a latent consonant at the end of the root for ‘alligator’: /kapɨC/. With the /-aN/ allomorph, the latent consonant is resyllabified as an onset and surfaces as [k]. When this happens, the second syllable becomes open and thus, main stress is assigned to the first syllable of the word:/kapɨC -aN/ → [ˈka.pɨ.kãN]. That does not happen when the /-kaN/ suffix is added. The root latent consonant remains as the coda of the second syllable, which is therefore closed. This attracts the main stress to the second syllable of the word: /kapɨC -kaN/ → [ka.ˈpɨC.kãN] → [ka.ˈpɨ.kãN]. The root /kamʊʂ/ in (20.b) shows exactly that same pattern but with a full-blown final consonant that can be observed in all contexts.

| (20) | UR | bare form | /-N/ form | /-kaN/ form | Gloss |

| a. | /βakɨ/ | [ˈβa.kɨ] | [βa.ˈkɨ̃N] | [ˈβa.kɨ.kãN] | ‘child, son’ |

| b. | /kamʊʂ/ | [ka.ˈmʊʂ] | [ˈka.mʊ.ʂãN] | [ka.ˈmʊʂ.kãN] | (sp. of snake) |

| c. | /kapɨC/ | [ka.ˈpɨ] | [ˈka.pɨ.kãN] | [ka.ˈpɨ.kãN] | ‘alligator’ |

| d. | /awaC/ | [a.ˈwa] | [ˈa.wa.kãN] | [a.ˈwa.kãN] | ‘tapir’ |

3.2. In Verb Roots

Thus far, we have presented evidence for the latent segment in non-verb roots. We can also find latent segments in verb roots due to the deletion of root final vowels. An instance of vowel deletion that creates latent segments in verbs is found when a body-part prefix is added to a bisyllabic root. Since body-part prefixes are monosyllabic in Panoan languages, the new stem would have ended up having three syllables. To avoid that result, the stem-final vowel is deleted. The data in (21) from Shipibo-Konibo show some instances of that phenomenon in three roots. In the first column, we can see the underlying representation of three roots. In the second column, a prefix has been added to each one:/pa-/ ‘ears, handles’, /βɨ-/ ‘eyes’, and /pɨ-/ ‘back’. In each case, the resulting stem loses its final vowel. In (21.a), the consonant [ʂ] is left as the stem-final segment, which always manages to surface since sibilants are allowed in both onset and coda positions. However, that is not the case in (21.b) and (21.c). The final-stem consonants after vowel deletion are [k] and [ɖ͡ʐ], respectively. Both are illicit segments to surface as syllable codas so that they become latent segments when parsed in that position.

| (21) | Bare root | Prefixed root |

| a. | /nɨʂa/ ‘to tie (it)’ | /pa- nɨʂa/ →/panɨʂ/‘to tie (it) by the handles’ |

| b. | /t͡sɨkɨ/ ‘to tear (it) out’ | /βɨ- t͡sɨkɨ/ →/βɨt͡sɨC/‘to tear the eyes out’ |

| c. | /ɖ͡ʐɨɖ͡ʐa/‘to slash (it)’ | /pɨ- ɖ͡ʐɨɖ͡ʐa/→/pɨɖ͡ʐɨC/‘to slash (it) from behind’ |

The data presented in (22), (23), and (24) show the same three roots and stems from (21) but this time conjugated employing the suffixes /-kɨ/ COMP and /-ai/ INC. The former ensures that if there is any preceding consonant, it will be parsed as a syllable coda while the latter makes sure any preceding consonant will be parsed as a syllable onset. This behavior can be straightforwardly seen by comparing (22.c) and (22.d). In [pa.ˈnɨʂ.kɨ], the main stress appears on the second syllable because it is closed but in [ˈpa.nɨ.ʂa.i], it occurs on the first syllable because now the second syllable is open. The data in (22.a) and (22.b) gives us a point of reference so we can see what happens with syllabification and the stress pattern when no prefixation takes place. The data in (23) and (24) contain latent segments (marked in bold) and presents the same syllabification and stress patterns as the data in (22). When the latent segment is parsed as a coda, it cannot surface but the main stress considers the second syllable to be closed and is attracted to it. See (23.c) and (24.c). Once it appears as a syllable onset, main stress jumps back to the word-initial syllable. See (23.d) and (24.d).

| (22) | UR | Surface form | |||||

| a. | /nɨʂa -kɨ/ | → | [ˈnɨ.ʂa.kɨ] | ||||

| ‘(s/he) tied (it)’ (COMP) | |||||||

| b. | /nɨʂa -ai/ | → | [ˈnɨ.ʂa.i] | ||||

| ‘(s/he) is tying (it)’ (INC) | |||||||

| c. | /pa- nɨʂa -kɨ/ | → | /panɨʂ -kɨ/ | → | [pa.ˈnɨʂ.kɨ] | ||

| ‘(s/he) tied (it) by the handles’ (COMP) | |||||||

| d. | /pa- nɨʂa -ai/ | → | /panɨʂ -ai/ | → | [ˈpa.nɨ.ʂa.i]6 | ||

| ‘(s/he) is tying (it) by the handles’ (INC) | |||||||

| (23) | UR | Surface form | |||||

| a. | /t͡sɨkɨ -kɨ/ | → | [ˈt͡sɨ.kɨ.kɨ] | ||||

| ‘(s/he) tore (it) out’ (COMP) | |||||||

| b. | /t͡sɨkɨ -ai/ | → | [ˈt͡sɨ.kɨ.a.i] | ||||

| ‘(s/he) is tearing (it) out’ (INC) | |||||||

| c. | /βɨ- t͡sɨkɨ -kɨ/ | → | /βɨt͡sɨC -kɨ/ | → | [βɨ.ˈt͡sɨ́C.kɨ] | → | [βɨ.ˈt͡sɨ.kɨ] |

| ‘(s/he) tore (his) eye out’ (COMP) | |||||||

| d. | /βɨ- t͡sɨkɨ -ai/ | → | /βɨt͡sɨC -ai/ | → | [ˈβɨ.t͡sɨ.ta.i] | ||

| ‘(s/he) tears (his) eye out’ (INC) | |||||||

| (24) | UR | Surface form | |||||

| a. | /ɖ͡ʐɨɖ͡ʐa -kɨ/ | → | [ˈɖ͡ʐɨ.ɖ͡ʐa.kɨ] | ||||

| ‘(s/he) slashed (it)’ (COMP) | |||||||

| b. | /ɖ͡ʐɨɖ͡ʐa -ai/ | → | [ˈɖ͡ʐɨ.ɖ͡ʐa.a.i] | ||||

| ‘(s/he) is slashing (it)’ (INC) | |||||||

| c. | /pɨ- ɖ͡ʐɨɖ͡ʐa -kɨ/ | → | /pɨɖ͡ʐɨC -kɨ/ | → | [pɨ.ˈɖ͡ʐɨ́C.kɨ] | → | [pɨ.ˈɖ͡ʐɨ.kɨ] |

| ‘(s/he) slashed (it) from behind’ (COMP) | |||||||

| d. | /pɨ- ɖ͡ʐɨɖ͡ʐa -ai/ | → | /pɨɖ͡ʐɨC -ai/ | → | [ˈpɨ.ɖ͡ʐɨ.ta.i] | ||

| ‘(s/he) is slashing (it) from behind’ (INC) | |||||||

Trisyllabic-verb roots also underwent deletion of their final vowel. For instance, Shell (1985) reconstructs the verb ‘to whisper’ as */βaʂɨʂɨ/whose synchronic correlate is /βaʂɨʂ/ in both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua. In this case, the final consonant left after vowel deletion is a sibilant and, therefore, permitted to appear as a coda or as an onset. This same phenomenon has also created latent segments when the consonant left at the end was not a sibilant or the /N/ nasal. For instance, Loriot et al. (1993) proposes */waʃikʊ/ as an ancient Shipibo-Konibo form to the modern verb /waʃiC/ ‘to refuse (it) maliciously’. The final latent segment only emerges when it is syllabified as an onset. The data in (25) shows the root /waʃiC/ as it receives the suffixes /-kɨ/ COMP and /-ai/ INC. Syllabification and stress behave parallel to the examples discussed in (22) to (24).

| (25) | UR | Surface form | |||

| a. | /waʃiC -kɨ/ | → | [wa.ˈʃiC.kɨ] | → | [wa.ˈʃi.kɨ] |

| ‘(s/he) refused (it) maliciously’ (COMP) | |||||

| b. | /waʃiC -ai/ | → | [ˈwa.ʃi.ta.i] | ||

| ‘(s/he) refuses (it) maliciously’ (INC) | |||||

In Capanahua, we can use the same tests to see whether a verb root or stem has a final latent consonant. A minor difference is that in Capanahua when two vowels meet at a morpheme boundary, a glottal stop is inserted between them. Compare (26.a) to (26.c): the epenthetic [ʔ] only appears in the former because otherwise the vowels [a] and [i] will be in contact at the morpheme boundary. In all other respects, Capanahua behaves as Shipibo-Konibo: (i) if the second syllable is closed, main stress occurs on it. See data in (26.d). This is also the case of (26.f) due to the latent consonant. Otherwise, main stress occurs on the initial syllable. See (26.a–c) and (26.e). Latent segments only surface when they are syllabified as the onset of a vowel. See example in (26.e). If the verb /nʊkʊC/ did not have a final latent consonant, then we would mistakenly expect a glottal stop to appear between the last vowel of the root and the suffix/-i/: *[ˈnʊ.kʊ.ʔi]. Compare it to [ˈba.na.ʔi] in (26.a).

| (26) | UR | Surface form | |||

| a. | /bana -i/ | → | [ˈba.na.ʔi] | ||

| ‘(s/he) cultivates (it)’ (INC) | |||||

| b. | /bana -kiN/ | → | [ˈba.na.kĩN] | ||

| ‘while (s/he) was cultivating (it)’ (SR) | |||||

| c. | /mʊʔiN -i/ | → | [ˈmʊ.ʔi.ni] | ||

| ‘(s/he) gets up’ (INC) | |||||

| d. | /mʊʔiN -kiN/ | → | [mʊ.ˈʔĩŋ.kĩN] | ||

| ‘while (s/he) was getting up’ (SR) | |||||

| e. | /nʊkʊC -i/ | → | [ˈnʊ.kʊ.ti] | ||

| ‘(s/he) arrives’ (INC) | |||||

| f. | /nʊkʊC -kiN/ | → | [nʊ.ˈkʊ́C.kĩN] | → | [nʊ.ˈkʊ.kĩN] |

| ‘while (s/he) was arriving’ (SR) | |||||

3.3. In Suffixes

Latent segments are not only present in lexical morphemes but also in suffixes. The data in (27) show some examples from Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua.

| (27) | Shipibo-Konibo | Capanahua | |

| a. | /-C/(MID) | g. | /-kɨʔC/(MID) |

| b. | /-jaC/(FUT) | h. | /-jaʔC/‘early’ |

| c. | /-pakɨC/‘downriver’ | i. | /-pakɨC/‘downriver’ |

| d. | /-ʔinaC/‘upriver’ | j. | /-ʔiʔnaC/‘upriver’ |

| e. | /-ʔibaC/‘the other day’ | k. | /-βʊ̃kɨC/‘one against the other’ |

| f. | /-βaiC/‘all day long’ | l. | /-jakɨC/‘to turn into, change direction’ |

As in the previous cases examined earlier, the latent segment at the end of those suffixes only surfaces when they are syllabified as onsets. The data in (28) illustrate this behavior through the latent consonant in the suffix /-jaC/ that marks future in Shipibo-Konibo. (28.a) shows that when the suffix that marks the incompletive aspect, /-ai/, is attached to the verb root/pi/‘to eat’, no consonant intervenes between them and the main stress falls on the initial syllable since the second one is open. In (28.b), the suffix /-jaC/ occurs immediately after the verb root. Since /-jaC/ is followed by a vowel (provided by the incompletive aspect suffix), its latent segment surfaces syllabified as an onset. Since the second syllable is light, the main stress appears on the initial one. In contrast, in (28.c), the suffix /-jaC/ is followed by the plural suffix /-kaN/. This time its latent segment does not surface since it could not be syllabified as an onset. Nevertheless, the main stress can still see it and considers the second syllable closed; therefore, it is attracted to it.

| (28) | UR | Surface form | |||

| a. | /pi -ai/ | → | [ˈpi.a.i] | ||

| ‘(s/he) is eating’ (INC) | |||||

| b. | /pi -jaC -ai/ | → | [ˈpi.ja.ta.i] | ||

| ‘(s/he) will eat’ (FUT, INC) | |||||

| c. | /pi -jaC -kaN -ai/ | → | [pi.ˈjaC.ka.na.i] | → | [pi.ˈja.ka.na.i] |

| ‘They will eat’ (FUT, PL, INC) | |||||

In the data in (29), we have the middle voice suffix of Shipibo-Konibo which consists of a single latent segment, /-C/. In (29.a–b), we observe the verb root /t͡ʃʊpɨ/ ‘to open, to unfold’ and the completive and incompletive suffixes, /-kɨ/ and /ai/, respectively. Since in both cases, the second syllable remains open, the main stress occurs on the initial one. As predicted, no latent consonant appears between the root and the /-ai/ suffix in (29.b). However, the forms in (29.c–d) do have a latent segment that corresponds to the middle voice suffix. In (29.c), the main stress appears on the second syllable since the phonology of Shipibo-Konibo can see the latent segment closing that syllable. Compare it to (29.a). In (29.d), the latent segment is parsed as a syllable onset and, therefore, it manages to surface as [t]. The main stress appears on the initial syllable because the second syllable is now truly open.

| (29) | UR | Surface form | |||

| a. | /t͡ʃʊpɨ -kɨ/ | → | [ˈt͡ʃʊ.pɨ.kɨ] | ||

| ‘(s/he) unfolded (it)’ (COMP) | |||||

| b. | /t͡ʃʊpɨ -ai/ | → | [ˈt͡ʃʊ.pɨ.a.i] | ||

| ‘(s/he) is unfolding (it)’ (INC) | |||||

| c. | /t͡ʃʊpɨ -C -kɨ/ | → | [t͡ʃʊ.ˈpɨC.kɨ] | → | [t͡ʃʊ.ˈpɨ.kɨ] |

| ‘(it) got unfolded’ (COMP) | |||||

| d. | /t͡ʃʊpɨ -C -ai/ | → | [ˈt͡ʃʊ.pɨ.ta.i] | ||

| ‘(it) is getting unfolded’ (INC) | |||||

The suffixes shown in (30) indicate that not all of them possess a final latent segment in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua. The data in (31) from Shipibo-Konibo demonstrates that no latent segment appears at the end of /-ma/ NEG, /-jama/ NEG and /-ɖ͡ʐiβi/ when followed by a suffix, like the incompletive aspect /-ai/, that begins in a vowel and would allow for any latent consonant to be resyllabified as an onset.

| (30) | Shipibo-Konibo | Capanahua | ||||

| a. | /-ma/CAUS | e. | /-ma/CAUS | |||

| b. | /-jama/NEG | f. | /-jama/NEG | |||

| c. | /-jʊɖ͡ʐa/INTENS | g. | /-jʊɖ͡ʐa/INTENS | |||

| d. | /-ɖ͡ʐiβi/‘again, also’ | h. | /-βaʔina/‘all day long’ | |||

| (31) | a. | /pi -ma -ai/ | → | [ˈpi.ma.i] *[ˈpi.ma.ta.i] | ‘(s/he) is making (him) eat’ (CAUS, INC) | |

| b. | /pi -jama -ai/ | → | [ˈpi.ja.ma.i] *[ˈpi.ja.ma.ta.i] | ‘(s/he) is not eating’ (NEG, INC) | ||

| c. | /pi -ma -ɖ͡ʐiβi -ai/ | → | [ˈpi.ma.ɖ͡ʐi.βi.a.i] *[ˈpi.ma.ɖ͡ʐi.βi.ta.i] | ‘(s/he) is making (him) eat again’ (CAUS, ‘again’, INC) | ||

4. Lexical Category and the Place of Articulation (PoA) of Latent Segments

In both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, regardless of what was the original manner of articulation in Proto-Pano, latent segments always surface as stops. Their PoA shows a more complex pattern of neutralization, however. When latent segments manage to surface as syllable onsets, their PoA is governed by the lexical category of the word that contains them. In verb paradigms, latent segments appear as coronal; while in non-verb paradigms, they surface as non-coronal, that is, either as labial or dorsal consonants.

The first column in (32) shows a short but representative list of nouns and adjectives in their reconstructed forms in Proto-Pano (Shell 1985). The final vowels of the roots appear in parentheses as a reminder that they underwent apocope leaving behind an illicit coda consonant, which became a latent segment. In order to see those latent consonants in the synchronic correlates of Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, the roots appear suffixed in their/-N/forms (e.g., Shipibo-Konibo:/kanaC -aN/ → [ˈka.na.kãN], Capanahua: /kanaC -aN/ → [ˈka.na.pãN]). In Capanahua, all latent segments in non-verb paradigms have been neutralized to labial. In Shipibo-Konibo, they all have been neutralized to dorsal.

| (32) | Proto-Pano | UR | Shipibo-Konibo | Capanahua | ||

| a. | *ka.na.p(a) | /kanaC -aN/ | → | ˈka.na.kãN | ˈka.na.pãN | ‘lightning’ |

| b. | *ka.pɨ.t(ɨ) | /kapɨC -aN/ | → | ˈka.pɨ.kãN | ˈka.pɨ.pãN | ‘alligator’ |

| c. | *ʔi.na.k(a) | /(ʔ)inaC -aN/ | → | ˈi.na.kãN | ˈʔi.na.pãN | ‘slave’ |

| d. | *saʔ.βa.k(a) | /sa(ʔ)βaC -aN/ | → | ˈsa.βa.kãN | ˈsaʔ.βa.pãN | ‘empty’ |

| e. | *maʂ.ka.t͡ʃ(a) | /maʂkaC -aN/ | → | ˈmaʂ.ka.kãN | ˈmaʂ.ka.pãN | ‘top’ |

| f. | *ʔa.wa.r(a) | /(ʔ)awaC -aN/ | → | ˈa.wa.kãN | ˈʔa.wa.pãN | ‘tapir’ |

In contrast, latent segments are all neutralized to coronal in verb forms. In the data in (33), we have the bisyllabic verb root /pɨka/ ‘to punch holes’ from Shipibo-Konibo. When the completive aspect suffix/-kɨ/is added in (33.a), the stress appears on the initial syllable showing that its second syllable is open; that is, there is no latent segment at the end of the root. When the incompletive aspect suffix /-ai/ is added in (33.b), as expected, no latent consonant appears between the final vowel of the root and the initial vowel of the suffix. The stress again falls on the initial syllable because the second one is open.

If we add a body-part prefix to that verb root; for instance, the prefix /kɨ-/ ‘mouth, lip’, the result would be a trisyllabic stem so in order to maintain bisyllabicity, the final vowel is dropped (/kɨ- pɨka/ → /kɨpɨk/‘to punch a hole in someone’s lip’), and the dorsal consonant /k/ would end up as the final latent segment of the stem. However, the problem is that latent segments in verb forms can only be coronal when they surface so that the original /k/ of the root /pɨka/ is neutralized to /t/. This pattern can be seen in (33.c) and (33.d). In the former, the stress on the second syllable shows that there is a latent consonant there, so the syllable is regarded as closed by the phonology of the language; in the latter, the incompletive aspect suffix /-ai/ allows the latent consonant to surface as a syllable onset, the main stress jumps to the initial syllable and as shown, the PoA of the latent consonant is now coronal.

| (33) | UR | Surface form | ||||

| a. | /pɨka -kɨ/ | → | [ˈpɨ.ka.kɨ] | |||

| ‘(s/he) punched holes’ (COMP) | ||||||

| b. | /pɨka -ai/ | → | [ˈpɨ.ka.i] | |||

| ‘(s/he) is punching holes’ (INC) | ||||||

| c. | /kɨ- pɨka -kɨ/ | → | /kɨ- pɨk -kɨ/ | → [kɨ.ˈpɨk.kɨ] | → | [kɨ.ˈpɨ.kɨ] |

| ‘(s/he) punched holes in (his) lip’ (COMP) | ||||||

| d. | /kɨ- pɨka -ai/ | → | /kɨ- pɨk -ai/ | → | [ˈkɨ.pɨ.ta.i] | |

| ‘(s/he) is punching holes in (his) lip’ (INC) | ||||||

The data in (34) shows the same pattern as in (33) but this time with the root /tʊpi/ ‘to gather’ whose second consonant is labial, /p/. When the prefix /ma-/ ‘head, surface/floor’ is added, the final vowel of the stem is dropped and/p/becomes latent (/ma- tʊpi/→/matʊp/‘to gather from the floor’). As in the case described above, when the latent segment surfaces as an onset, its PoA is neutralized to coronal because the word is a verb. This is shown in (34.d).

| (34) | UR | Surface form | ||||

| a. | /tʊpi -kɨ/ | → | [ˈtʊ.pi.kɨ] | |||

| ‘(s/he) gathered (them)’ (COMP) | ||||||

| b. | /tʊpi -ai/ | → | [ˈtʊ.pi.ai] | |||

| ‘(s/he) is gathering (them)’ (INC) | ||||||

| c. | /ma- tʊpi -kɨ/ | → | /ma- tʊp -kɨ/ | → [ma.ˈtʊp.kɨ] | → | [ma.ˈtʊ.kɨ] |

| ‘(s/he) gathered (them) from the floor’ (COMP) | ||||||

| d. | /ma- tʊpi -ai/ | → | /ma- tʊp -ai/ | → | [ˈma.tʊ.ta.i] | |

| ‘(s/he) is gathering (them) from the floor’ (INC) | ||||||

As shown in the data in (35) and (36), the same behavior is found in Capanahua. In (35), we see a verb root that has a final latent segment, /pat͡saC/ ‘to wash clothes’ and appears with two suffixes: the incompletive aspect suffix, /i-/; and the switch-reference suffix for simultaneous action, /-kiN/. The root-final consonant emerges as a coronal onset, [t], in (35.a) when the following suffix is a vowel but when the suffix begins with a consonant, as in (35.b), the latent segment cannot surface.

| (35) | a. | /pat͡saC -i/ | → | [ˈpa.t͡sa.ti] | |

| ‘(s/he) washes clothes’ (INC) | |||||

| b. | /pat͡saC -kiN/ | → [pa.ˈt͡saC.kĩN] | → | [pa.ˈt͡sa.kĩN] | |

| ‘while (s/he) was washing clothes’ (SR) | |||||

In (36), we can see how a consonant with a non-coronal PoA in Capanahua is neutralized to coronal if it ends up as the latent segment of a verb stem. In this instance we have the verb /wakɨ/ ‘to lift’, whose second consonant is a dorsal stop, /k/. The form in (36.a) shows that the verb root does not have a latent consonant. When the incompletive aspect suffix /-i/ is added, a glottal stop is inserted so the vowel of the verb root and that of the suffix are not in direct contact. In (36.b) and (36.c), the verb stem is /kɨwaC/ ‘to lift (its) edge’ which results from prefixing /kɨ-/ ‘lip, edge’ to the root/wakɨ/‘to lift’. The outcome of this morphological operation would be a three-syllable stem therefore, as also was the case in Shipibo-Konibo, to preserve bisyllabicity, the final vowel is dropped (/kɨ- wakɨ/ → /kɨwak/). In (36.b), when the latent consonant is parsed as an onset, it surfaces as coronal, even though we can trace back its original PoA to dorsal. In (36.c), the latent consonant cannot surface if it has been parsed as a coda, but the main stress can still see it as it is attracted to the heaviness of the second syllable.

| (36) | UR | Surface form | ||||

| a. | /wakɨ -i/ | → | [ˈwa.kɨ.ʔi] | |||

| ‘(s/he) lifts (it)’ (INC) | ||||||

| b. | /kɨ- wakɨ -i/ | → | /kɨ- wak -i/ | → | [ˈkɨ.wa.ti] | |

| ‘(s/he) lifts (its) edge’ (INC) | ||||||

| c. | /kɨ- wakɨ -kiN/ | → | /kɨ- wak -kiN/ | → [kɨ.ˈwak.kĩN] | → | [kɨ.ˈwa.kĩN] |

| ‘while (s/he) was lifting (its) edge’ (SR) | ||||||

We can also see how the PoA of a latent segment changes when the lexical category of the word changes. The data in (37) to (40) come from Shipibo-Konibo. In (37) and (38), we have the noun root, /pʊpʊ/‘owl’ and an adjective root /βɨnɨ/ ‘happy’. They do not have a latent segment. No latent consonant ever appears between those roots and their suffixes. Of particular interest are the forms in (37.d), (37.e), (38.c), and (38.d) where by adding a verb suffix to the bare root (either a noun or an adjective), we obtain a derived verb. Thus, for example, the noun /pʊpʊ/ ‘owl’ becomes [ˈpʊ.pʊ.a.i] ‘(s/he) is turning into an owl’ by adding the incompletive aspect, /-ai/.

| (37) | a. | /pʊpʊ/ | → | [ˈpʊ.pʊ] | noun ‘owl’ in bare root form |

| b. | /pʊpʊ -N/ | → | [pʊ.ˈpʊ̃N] | noun ‘owl’ in/-N/form | |

| c. | /pʊpʊ -VOC/ | → | [pʊ.ˈpʊ] | noun ‘owl’ in vocative form | |

| d. | /pʊpʊ -ai/ | → | [ˈpʊ.pʊ.a.i] | verb in incompletive aspect form (‘s/he is turning into an owl’) | |

| e. | /pʊpʊ -kɨ/ | → | [ˈpʊ.pʊ.kɨ] | verb in completive aspect form (‘s/he turned into an owl’) | |

| (38) | a. | /βɨnɨ/ | → | [ˈβɨ.nɨ] | adjective ‘happy’ in bare root form |

| b. | /βɨnɨ -N/ | → | [βɨ.ˈnɨN] | adjective ‘happy’ in/-N/form | |

| c. | /βɨnɨ -ai/ | → | [ˈβɨ.nɨ.a.i] | verb in incompletive aspect form (‘s/he is becoming happy’) | |

| d. | /βɨnɨ -kɨ/ | → | [ˈβɨ.nɨ.kɨ] | verb in completive aspect form (‘s/he became happy’) |

In contrast, we have a noun root and an adjective root with a latent segment each in (39) and (40): /isaC/ ‘bird’ and /βɨnaC/ ‘new’. The morphological forms are identical to those shown in (37) and (38). The latent consonant surfaces as a dorsal in the noun forms but as coronal in the verb form. The data in (39) and (40) also provide a clear instance of a synchronic alternation between neutralization to coronal and non-coronal PoA that was undergone by a latent segment depending on the lexical category of the word hosting it.

| (39) | a. | /isaC/ | → | [i.ˈsa] | (noun) | |

| ‘bird’ | ||||||

| b. | /isaC -aN/ | → | [ˈi.sa.kãN] | (noun) | ||

| ‘bird’ (/-N/form) | ||||||

| c. | /isaC -VOC/ | → | [i.sa.ˈka] | (noun) | ||

| ‘bird’ (VOC) | ||||||

| d. | /isaC -ai/ | → | [ˈi.sa.ta.i] | (verb) | ||

| ‘s/he is turning into a bird’ (INC) | ||||||

| e. | /isaC -kɨ/ | → [i.ˈsaC.kɨ] | → | [i.ˈsa.kɨ] | (verb) | |

| ‘s/he turned into a bird’ (COMP) | ||||||

| (40) | a. | /βɨnaC/ | → [βɨ.ˈnaC] | → | [βɨ.ˈna] | (adjective) |

| ‘new’ | ||||||

| b. | /βɨnaC -aN/ | → | [ˈβɨ.na.kãN] | (adjective) | ||

| ‘new’ (/-N/form) | ||||||

| c. | /βɨnaC -ai/ | → | [ˈβɨ.na.ta.i] | (verb) | ||

| ‘it is becoming new’ (INC) | ||||||

| d. | /βɨnaC -kɨ/ | → [βɨ.ˈnaC.kɨ] | → | [βɨ.ˈna.kɨ] | (verb) | |

| ‘it became new’ (COMP) | ||||||

4.1. Dialectal Variations

Although the patterns discussed above are robust, there exist native speakers of Shipibo-Konibo that show a slightly different treatment of the PoA of latent segments. For them, latent segments are always neutralized to coronal [t] both in verb and in non-verb forms. Instances of this dialectal variation is shown in the data in (41). No such variation has been observed in Capanahua.

| (41) | UR | Noun bare form | Standard: /-N/form | Dialectal variation: /-N/form | Gloss. |

| a. | /inaC/ | [i.ˈna] | [ˈi.na.kãN] | [ˈi.na.tɨ̃N] | ‘slave’ |

| b. | /kapɨC/ | [ka.ˈpɨ] | [ˈka.pɨ.kãN] | [ˈka.pɨ.tɨ̃N] | ‘alligator’ |

| c. | /pɨkaC/ | [pɨ.ˈka] | [ˈpɨ.ka.kãN] | [ˈpɨ.ka.tɨ̃N] | ‘back’ |

| d. | /ᶊakaC/ | [ᶊa.ˈka] | [ˈᶊa.ka.kãN] | [ˈᶊa.ka.tɨ̃N] | ‘shell’ |

4.2. Exceptions

There exist some exceptions to the generalization about coronal being the default PoA for latent segments in verb forms. However, they are extremely rare. In Shipibo-Konibo, I only know of two exceptions that correspond to two verbs with high frequency of occurrence and that can behave as verbalizers as well as play much of the role that ‘do-support’ does in English. These are the intransitive verb /ʔik/ ‘to be, to happen’; and the transitive verb /ʔak/ ‘to do, to say’. They both have a latent segment but when it emerges, it always appears as a dorsal stop. In (42), we can observe both verbs together with the infinitive suffix /-ti/ and the incompletive aspect suffix /-ai/. With the former, the latent segment does not surface since it does not have the chance to be parsed as an onset. In contrast, with the suffix /-ai/, the latent consonant does surface, and it appears as dorsal, [k].

| (42) | a. | /ʔik -ti/ | → | [ˈʔi.ti] | ‘to be, to happen’ (INF) |

| b. | /ʔik -ai/ | → | [ˈʔi.ka.i] | ‘(it) is happening’ (INC) | |

| c. | /ʔak -ti/ | → | [ˈʔa.ti] | ‘to do, to say’ (INF) | |

| d. | /ʔak -ai/ | → | [ˈʔa.ka.i] | ‘(it) is doing (something)’ (INC) |

Capanahua is slightly more complex. As Shipibo-Konibo, Capanahua possesses the equivalents of the verbs in (42). They are: /ʔiʔk/ ‘to be, to exist, to say’ and /ʔaʔk/ ‘to do, to say’. They both have a latent segment that surfaces as dorsal. In addition, I know of four other Capanahua verb suffixes that have non-coronal latent segments: /-ʂiʔk/ (immediate future in declarative sentences), /-paʔit͡ʃ/ ‘to feel like (doing something)’, /-ɖ͡ʐit͡ʃ/ ‘quick, yet’, and/-kaʔtit͡ʃ/ ‘each time’. The data in (43) and (44) show the behavior of the latent segments of /-ʂiʔk/ and /-ɖ͡ʐit͡ʃ/, respectively. As observed in (43.b) and (44.b), they surface faithful to their underlying PoA specification.

| (43) | a. | /pi -ʂiʔk -wɨ/ | → | [pi.ˈʂiʔ.wɨ] | ‘eat (it soon)!’ (FUT, IMP) |

| b. | /baɖ͡ʐi -ʂiʔk -i/ | → | [ˈba.ɖ͡ʐi.ʂiʔ.ki] | ‘the sun will rise (soon)’ (FUT, INC) | |

| (44) | a. | /hʊ -ɖ͡ʐit͡ʃ -wɨ/ | → | [hʊ.ˈɖ͡ʐi.wɨ] | ‘come quickly!’ (‘quick’, IMP) |

| b. | /βʊ -ɖ͡ʐit͡ʃ -i/ | → | [ˈβʊ.ɖ͡ʐi.t͡ʃi] | ‘(they) go quickly’ (‘quick’, INC) |

5. PoA of Morpheme-Final Nasals

Regarding their PoA, nasal consonants at the end of morphemes behave in a very similar way to the latent segments that we have been discussing. An important difference, compared to latent segments, is that nasal consonants are always allowed to surface either as syllable onsets or codas. See the data in (45) from Shipibo-Konibo. As described in Section 2, the nasal coda /N/ takes the PoA of the following consonant if it is a stop. In word-final position, it surfaces as [N] and always strongly nasalizes the preceding vowel and the said nasalization can spread to surrounding vowels and glides.

| (45) | a. | /nʊnʊN/ | → | [nʊ.ˈnʊ̃N] | ‘duck’ |

| b. | /isiN/ | → | [i.ˈsĩN] | ‘illness’ | |

| c. | /hʊnaN/ | → | [hʊ.ˈnãN] | ‘smoked’ | |

| d. | /jaja -N/ | → | [j̃ã.ˈj̃ãN] | ‘woman’s mother-in-law’ | |

| e. | /ʂʊNtakʊ/ | → | [ˈʂʊ̃n.ta.kʊ] | ‘young woman’ | |

| f. | /pɨNpɨN/ | → | [pɨ̃m.ˈpɨ̃N] | ‘butterfly’ |

It is also possible to find cases where an underlying /m/or/n/ becomes [N] when parsed as a coda consonant. This can be observed in the data in (46) and (47) where we have the verb roots /tima/ ‘to hit/bang (something against another object)’ and /tina/ ‘to pack’, respectively. Those verb roots form a minimal pair whose sole difference is the intervocalic nasals: /m/and/n/. For comparison with what it is described next, they appear suffixed, in (46.a–b) and (47.a–b), with the completive and incompletive aspect suffixes, /-kɨ/ and /-ai/. When a body prefix like /t͡ʃi-/ ‘buttocks, behind, stern, tail’ is added, the root-final vowels are dropped to avoid creating a trisyllabic stem. Once the root final vowels are deleted, the consonants/m/and/n/become the final consonants of their morphemes and in that context, they are neutralized to [N] if they occur as codas or to [n], since the roots are verbs, if they occur as onsets. This can be seen in (46.c–d) and (47.c–d). As a result, both prefixed-verb roots become homophones.

| (46) | UR | Surface form | ||||

| a. | /tina -kɨ/ | → | [ˈti.na.kɨ] | |||

| ‘(s/he) packed (it)’ (COMP) | ||||||

| b. | /tina -ai/ | → | [ˈti.na.i] | |||

| ‘(s/he) is packing (it)’ (INC) | ||||||

| c. | /t͡ʃi- tina -kɨ/ | → | /t͡ʃi- tin -kɨ/ | →/t͡ʃitiN -kɨ/ | → | [t͡ʃi.ˈtĩN.kɨ] |

| ‘(s/he) packed (it) from the stern’ (COMP) | ||||||

| d. | /t͡ʃi- tina -ai/ | → | /t͡ʃi- tin -ai/ | → | [ˈ t͡ʃi.ti.na.i] | |

| ‘(s/he) was packing (it) from the stern’ (INC) | ||||||

| (47) | UR | Surface form | ||||

| a. | /tima -kɨ/ | → | [ˈti.ma.kɨ] | |||

| ‘(s/he) hit/banged (it against something)’ (COMP) | ||||||

| b. | /tima -ai/ | → | [ˈti.ma.i] | |||

| ‘(s/he) hits/bangs (it against something)’ (INC) | ||||||

| c. | /t͡ʃi- tima -kɨ/ | → | /t͡ʃi- tim -kɨ/ | →/t͡ʃitiN -kɨ/ | → | [t͡ʃi.ˈtĩN.kɨ] |

| ‘(s/he) hit/banged (his/her) buttocks (against something)’ (COMP) | ||||||

| d. | /t͡ʃi- tima -ai/ | → | /t͡ʃi- tim -ai/ | → | [ˈ t͡ʃi.ti.na.i] | |

| ‘(s/he) hits/bangs (his/her) buttocks (against something)’ (INC) | ||||||

When the nasal /N/ is parsed as a syllable onset, its PoA, as in the case of latent segments, will depend on the lexical category of the word hosting it. If it is a verb, its PoA will be invariable a coronal nasal, [n]. See, for instance, (46.d) and (47.d). In contrast, if the word is a non-verb form (namely, a noun or an adjective), then the nasal consonant /N/ will surface as non-coronal, specifically as a labial nasal, [m], but never as a dorsal nasal, [ŋ]. This again happens regardless of what the original PoA of the nasal was. The data in (48), (49), and (50) from Shipibo-Konibo shows this. The nasal/N/under discussion appear in bold. The reconstructed forms in Proto-Pano are displayed for the datasets in (48) and (49). Observe that in the former, the nasal consonant of the final syllable in the reconstructed form is a coronal nasal, [n]; while in the latter, it is a bilabial nasal, [m]. Once the root-final vowel was lost, /N/ was left as the final segment of the morpheme. As shown in (48.b) and (49.b), in coda position, it always surfaces as [N]. In (48.c–d) and (49.c–d), /N/appears as a labial nasal, [m], when it is parsed as an onset. In contrast, in (48.e–f) and (49.e–f), the same/N/surfaces as a coronal nasal, [n], when it is parsed as an onset. The difference is that in (48.c–d) and (49.c–d), /N/belongs to a noun while in (48.e–f) and (49.e–f), it belongs to a verb. The same pattern is shown in (50) when the root is an adjective.

| (48) | a. | *kamano (Proto-Pano) | ‘jaguar, demon’ | ||

| b. | /kamaN/ | → | [ka.ˈmãN] | noun in bare form | |

| c. | /kamaN -aN/ | → | [ˈka.ma.mãN] | noun in /-N/ form | |

| d. | /kamaN -V/ | → | [ka.ma.ˈma] | noun in vocative form | |

| e. | /kamaN -ai/ | → | [ˈka.ma.na.i] | verb in incompletive aspect form (‘s/he turned into a jaguar’) | |

| f. | /kamaN -i/ | → | [ˈka.ma.ni] | verb in switch reference form (‘while s/he turns into a jaguar’) | |

| (49) | a. | *wiʃtima (Proto-Pano) | ‘star’ | ||

| b. | /wiʃtiN/ | → | [wiʃ.ˈtĩN] | noun in bare form | |

| c. | /wiʃtiN -aN/ | → | [ˈwiʃ.ti.mãN] | noun in /-N/ form | |

| d. | /wiʃtiN -V/ | → | [wiʃ.ti.ˈma] | noun in vocative form | |

| e. | /wiʃtiN -ai/ | → | [ˈwiʃ.ti.na.i] | verb in incompletive aspect form (‘s/he turned into a star) | |

| f. | /wiʃtiN -i/ | → | [ˈwiʃ.ti.ni] | verb in switch reference form (‘while s/he turns into a star’) | |

| (50) | a. | (unknown Proto-Pano form) | ‘good, nice’ | ||

| b. | /hakʊN/ | → | [ha.ˈkʊ̃N] | adjective in bare form | |

| c. | /hakʊN -aN/ | → | [ˈha.kʊ.mãN] | adjective in /-N/ form | |

| d. | /hakʊN -ai/ | → | [ˈha.kʊ.na.i] | verb in incompletive aspect form (‘s/he is becoming nice) | |

| e. | /hakʊN -kɨ/ | → | [ha.ˈkʊ̃N.kɨ] | verb in completive aspect form (‘s/he became nice) | |

6. PoA of Latent Segments in Adverbs

Morphologically, adverb roots in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua pattern with verb roots. They can show participant agreement in the form of switch-reference morphology that is characteristic of verbs (Loriot et al. 1993; Valenzuela 2003). In (51) and (52), taken from Valenzuela (2003, pp. 172–73), the adverb /kikiN/ ‘well to a higher degree’ occurs with the switch-reference suffixes: /-ʂʊN/ and /-aʂ/.7 In (51), the adverb /kikiN/ appears combined with the suffix /-ʂʊN/. The final segment of the adverb occurs parsed as the coda of the second syllable, which attracts the main stress. As expected, in coda position, the nasal surfaces as placeless: [N]. In contrast, in (52), the same adverb root appears suffixed by /-aʂ/. This allows the final consonant of the adverb to occur as a syllable onset and, as we can observe, when this happens, its PoA is neutralized to coronal, just as verbs do.

| (51) | ki.ˈkiN.ʂʊN ˈpi.kɨ |

| kikiN-ʂʊN pi-kɨ | |

| Extremely-SR eat-COMP | |

| ‘(he/she) ate (the food) elegantly’ | |

| (52) | ˈki.ki.naʂ ˈja.ka.ta |

| kikiN-aʂ jakaC-a | |

| Extremely-SR sit-CPLP | |

| ‘sitting extremely well (like posing)’ |

Adverbs can also be turned into verbs just by attaching tense/aspect suffixes. When this occurs, if the adverb root has a final latent or nasal consonant, it surfaces as coronal. This is illustrated in the data in (53) and (54).

| (53) | UR | Surface form | Gloss. | |||

| a. | /ʊt͡ʃʊC/ | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊC] | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊ] | ‘far’ |

| b. | /ʊt͡ʃʊC -kɨ/ | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊC.kɨ] | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊ.kɨ] | ‘(it) got further away’ |

| c. | /ʊt͡ʃʊC -ai/ | → | [ˈʊ.t͡ʃʊ.ta.i] | ‘(it) is getting further away’ | ||

| (54) | UR | Surface form | Gloss. | |||

| a. | /kikiN/ | → | [ki.ˈkĩN] | ‘well to a higher degree’ | ||

| b. | /kikiN -kɨ/ | → | [ki.ˈkĩN.kɨ] | ‘(he) bettered himself’ | ||

| c. | /kikiN -ai/ | → | [ˈki.ki.na.i] | ‘(she) is bettering herself’ | ||

However, unlike nouns, adjectives and verbs, there is no clear evidence when it comes to adverb roots on what PoA latent segments take when they surface as syllable onsets. The cases shown in (51) and (52) cannot be taken as evidence that they neutralize to coronal since it can be argued to represent adverbs that have been turned into verbs; and, therefore, it is not surprising their PoA neutralizes to coronal. Thus, they would not be different from the cases in (53) and (54). Unfortunately, there are a small number of suffixes that can combine with adverb roots and that do not change their lexical category, and all of them begin with a consonant (e.g., /-ma/ NEG, /-tian/ ‘during that time’, /-t͡ʃa/ ‘a bit more’). They cannot tell us what happens to the PoA of latent and nasal segments in adverb roots. See data in (55) and (56).

| (55) | UR | Surface form | Gloss. | |||

| a. | /ɖ͡ʐama/ | [ˈɖ͡ʐa.ma] | ‘now’ | |||

| b. | /ɖ͡ʐama -ma/ | [ˈɖ͡ʐa.ma.ma] | ‘long time ago’ (NEG) | |||

| c. | /ɖ͡ʐama -tian/ | [ˈɖ͡ʐa.ma.ti.ãn] | ‘at that time’ | |||

| (56) | UR | Surface form | Gloss. | |||

| a. | /ʊt͡ʃʊC/ | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊC] | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊ] | ‘far’ |

| b. | /ʊt͡ʃʊC -ma/ | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊC.ma] | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊ.ma] | ‘near’ (NEG) |

| c. | /ʊt͡ʃʊC -t͡ʃa/ | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊC.t͡ʃa] | → | [ʊ.ˈt͡ʃʊ.t͡ʃa] | ‘a bit further’ |

7. Analysis

7.1. Coronal as the Default PoA of Latent Segments in Verb Forms

In phonology, it has been long observed that when a consonant requires a PoA in the oral cavity, coronal is the preferred, the least marked option (de Lacy and Kingston 2013; Kenstowicz 1994; Paradis and Prunet 1989, 1990a, 1990b, 1991; Rice 1994, 1996, 2000a, 2000b; Stemberger and Stoel-Gammon 1991). Other studies suggest that coronal is not the least unmarked PoA for consonants, but laryngeal is. In that approach, coronal only emerges as the second best least-unmarked option for PoA when the grammar blocks laryngeal (Lombardi 1991, 2002; McCarthy 1994a, 1994b). In OT (McCarthy and Prince 1994; Prince and Smolensky 1993, 2004), these observations have been typically captured through the fixed ranking of constraints in (57).8 The ranking of *Labial and *Dorsal over *Coronal is proposed by Prince and Smolensky (1993, 2004); Smolensky (1993) while the ranking of *Coronal over *Pharyngeal, by Lombardi (2002).9

| (57) | *Labial, *Dorsal >> *Coronal >> *Pharyngeal |

In order to account for the PoA of latent segments found in verb forms in both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, I propose to use a version of the fixed ranking in (57) that penalizes the occurrence of consonants with certain PoA in the final position of verb forms. This is shown in (58).

| (58) | *Labial]Verb, *Dorsal]Verb >> *Coronal]Verb >> *Pharyngeal]Verb |

I assume that the ranking between *Labial]Verb and *Dorsal]Verb is not fixed. It can vary from one language to another. However, whatever their ranking, both always outrank *Coronal]Verb. The environment that triggers a violation of each constraint is provided in (59) to (62).

| (59) | *Labial]Verb: Assign a violation mark for each labial consonant that occurs at the end of a verb form. |

| (60) | *Dorsal]Verb: Assign a violation mark for each dorsal consonant that occurs at the end of a verb form. |

| (61) | *Coronal]Verb: Assign a violation mark for each coronal consonant that occurs at the end of a verb form. |

| (62) | *Pharyngeal]Verb: Assign a violation mark for each pharyngeal consonant that occurs at the end of a verb form. |

The analysis that follows will also require the following constraints. The faithfulness constraint Max-C penalizes the deletion of consonants present in the input10 while Ident[Place] assigns a violation to output consonants that have not preserved their PoA specification. On the other hand, the markedness constraint HavePlace requires output consonants to be specified for PoA. The *ʔ constraint is Lombardi (2002)’s *[+glottal] constraint. Its counterpart *[-glottal], which outranks it and militates against pharyngeal segments, can be assumed to be present but undominated in languages like Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua so no pharyngeal consonant is ever able to appear. Finally, the *ŋ constraint militates against the occurrence of velar nasal consonants in the output.

| (63) | Max-C: Consonants must be preserved in the output. |

| (64) | Ident[Place]: The place of articulation of consonants must be preserved in the output. |

| (65) | HavePlace: An output consonant must have a place specification. |

| (66) | *ʔ: Do not have glottal consonants. |

| (67) | *ŋ: Do not have velar nasal consonants. |

Table 1 shows the verb root /kamiC/ ‘to strain to lift (something)’. Its final segment is a latent consonant. As a convention, all the output correspondents of the latent segment appear in bold. The ranking of Max-C, HavePlace, *ʔ, *Dorsal]Verb and *Labial]Verb over *Coronal]Verb ensure that the latent consonant always surfaces as coronal when parsed as a syllable onset. The ranking in Table 1 also accounts for why morpheme-final nasal consonants when parsed as onsets surface as coronal in verb forms regardless of whether they have an underlying place specification or not (e.g., /kʊβiN -ai/ → [ˈkʊ́.βi.na.i] ‘(it) is boiling’).

Table 1.

/kamiC -ai/→ [ˈká.mi.ta.i] ‘(s/he) is straining to lift (it)’ (Shipibo-Konibo).

Section 4 showed that in both Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, when a bisyllabic-verb root receives a body-part prefix, apocope is triggered to avoid resulting in a trisyllabic stem. Thus, for example, when the prefix /kɨ-/ ‘in the lip(s)’ is added to the root /pɨka/ ‘to punch holes’ in (33), the resulting stem is /kɨpɨk/ ‘to punch holes in (his) lip(s)’. The apocope should have left the /k/ of /pɨka/ as the final consonant, but since it is a stop consonant it becomes a latent segment when parsed as a coda (/kɨpɨk -kɨ/ → [kɨ.ˈpɨk.kɨ] → [kɨ.ˈpɨ.kɨ] ‘(s/he) punched holes in (his) lip’). However, it surfaces not as a dorsal consonant but as a coronal when it is parsed as an onset (/kɨpɨk -ai/ → [ˈkɨ.pɨ.ta.i] ‘(s/he) is punching holes in (his) lip’). Thus, it does not matter what the original PoA was (the segment could be placeless or specified for any place), when the morpheme-final latent consonant surfaces as an onset in a verb form, it always appears as coronal, [t]. This behavior is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

/kɨpɨk -ai/→ [ˈkɨ.pɨ.ta.i] ‘(s/he) is punching holes in (his) lip’ (Shipibo-Konibo).

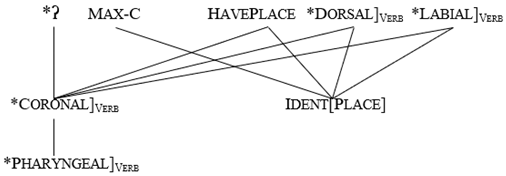

The OT grammar in (68) summarizes how Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua govern the PoA of their latent segments when they occur as syllable onsets in verb forms. The ranking of *Dorsal]Verb, *Labial]Verb, and *ʔ over *Coronal]Verb and Ident[Place] turns coronal the default PoA for consonants appearing at the end of a morpheme. The ranking of HavePlace over *Coronal]Verb and Ident[Place] ensures that they do not surface as placeless to satisfy the constraints militating against the different places of articulation. The neutralization to coronal occurs regardless of whether the morpheme-final consonant is underlyingly specified for place or not.

| (68) Constraint ranking to account for PoA of latent segments in verb forms |

|

7.2. Non-Coronal as the Default PoA of Latent Segments in Non-Verb Forms

Harmonic Alignment (Prince and Smolensky 1993) is a mechanism in OT by which two markedness hierarchies are combined to create two fixed rankings of markedness constraints. The elements in each markedness hierarchy are ordered from the highest degree to the lowest according to some dimension of prominence. One of the markedness hierarchies refers to a linguistic property or structure and the other markedness hierarchy refers to linguistic contexts. Thus, each of the resulting markedness constraints militates against the presence of a linguistic property/structure occurring in a context. The higher a constraint is ranked within the fixed ranking, the more undesirable the occurrence of that property in the context indicated by the constraint. For instance, Prince and Smolensky (1993, 2004) align the sonority markedness hierarchy (in which vowels are more prominent than sonorants and sonorants, more prominent than obstruents, represented as |Vowels > Sonorants > Obstruents|) with a markedness hierarchy on syllable positions (in which the syllable nucleus is more prominent than the syllable margins, represented as |Nucleus > Margins|). The sonority markedness hierarchy provides the linguistic property while the syllable position markedness hierarchy provides the contexts. The alignment of the markedness hierarchies proceeds by first combining the most prominent element of the markedness hierarchy that provides the context with the most prominent element of the markedness hierarchy that provides the linguistic property. Thus, we obtain: Nucleus/Vowels. Then, we continue to combine the same most prominent element of the context-referring markedness hierarchy with the second most prominent element of the property-referring markedness hierarchy, which gives us: Nucleus/Sonorants. This is repeated until all the elements of the property-referring markedness hierarchy have been combined with the most prominent element of the context-referring markedness hierarchy. When this procedure is applied to the first element of the markedness hierarchy on syllable positions, the result is the Harmonic Scale displayed in (69). Then, when we get to the other end of the context-referring markedness hierarchy, we start combining its least prominent element with the least prominent element in the other markedness hierarchy. In the case of the markedness hierarchy on syllable positions, the element on the other end of the markedness hierarchy is Margins and it should be first combined with the least prominent element in the sonority markedness hierarchy. Thus, the first combination that we get is: Margins/Obstruents. Then, we combine Margins with the second least prominent element in the sonority markedness hierarchy: Margins/Sonorants. At the end, the result is the Harmonic Scale displayed in (70).

| (69) | HNucleus = Nucleus/Vowels › Nucleus/Sonorants › Nucleus/Obstruents |

| (70) | HMargins = Margins/Obstruents › Margins/Sonorants › Margins/Vowels |

Each harmonic scale is converted into a fixed ranking of markedness constraints by reversing the order of its elements and assigning to each element the meaning “do not have the property X in the context Y”. This meaning is indicated by an asterisk. Thus, for example, *Nuc/Obs means: “do not have an obstruent in the syllable nucleus” (a violation is assigned for every obstruent that occurs as a syllable nucleus). The Fixed Rankings derived from the harmonic scales just discussed appear in (71) and (72), respectively.

| (71) | CNucleus = *Nuc/Obs >> *Nuc/Son >> *Nuc/Vowels |

| (72) | CMargins = *Marg/Vowels >> *Marg/Obs >> *Marg/Son |

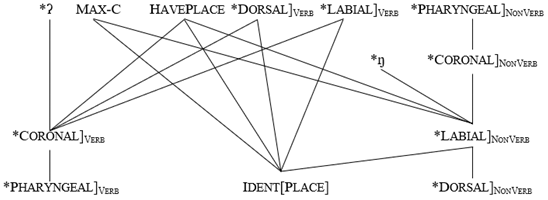

A key observation when the fixed rankings of constraints that result from combining two markedness hierarchies are compared is that the preference for the elements in the property-referring markedness hierarchy appear in opposite order according to the context in which they are evaluated. Thus, for instance, while in the syllable nucleus, obstruents are highly unwelcome; in the syllable margins, they are highly desired. This is exactly the situation we find in Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua regarding the PoA of latent segments: in verb forms, labial and dorsal are avoided and coronal is the preferred choice. In contrast, in non-verb forms, labial or dorsal are the preferred choices while coronal is evaded. The obvious difference is that in both Panoan languages, the context in which this occurs is not phonetic or phonological in nature. It is not like the case of the syllable position markedness hierarchy which refers to the syllable nucleus and its margins. In the case of Shipibo-Konibo and Capanahua, the context is morphophonological: the final segmental position of morphemes in verb and non-verb forms. This study claims that in both Panoan languages, the reference to those contexts is the reflection of a markedness hierarchy represented as: |NonVerb > Verb|. The Verb element refers to the segmental position at the end of a verb morpheme (either a verb root, stem, or suffix). The NonVerb element refers to the segmental position at the end of noun and adjective morphemes (either non-verb roots, stems or suffixes). Now, let us harmonically align the morphological markedness hierarchy |NonVerb > Verb| with the PoA markedness hierarchy |NonCoronal > Coronal > Pharyngeal|. During the harmonic alignment procedure, I will use NonCoronal to refer to both labial and dorsal together. The alignment creates the two harmonic scales displayed in (73) and (74).

| (73) | HVerb = Verb/Phar › Verb/Cor › Verb/NonCor |

| (74) | HNonVerb = NonVerb/NonCor › NonVerb/Cor › NonVerb/Phar |

When the elements of those harmonic scales are turned into constraints, we end up with the two fixed rankings indicated in (75) and (76).

| (75) | CVerb = *Verb/NonCor >> *Verb/Cor >> *Verb/Phar |

| (76) | CNonVerb = *NonVerb/Phar >> *NonVerb/Cor >> *NonVerb/NonCor |

The fixed ranking in (75), which applies to verb forms, is the one that we have already employed in Section 7.1, shown in (58), under the more decipherable labels: *Dorsal]Verb, *Labial]Verb >> *Coronal]Verb >> *Pharyngeal]Verb. I intend to keep using that label format. Thus, the constraints of the fixed rankings in (75) and (76) will appear henceforth displayed as in (77) and (78).11

| (77) | *Dorsal]Verb, *Labial]Verb >> *Coronal]Verb >> *Pharyngeal]Verb |

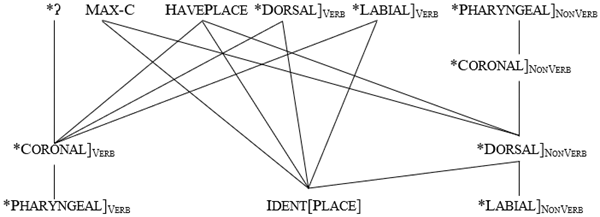

| (78) | *Pharyngeal]NonVerb >> *Coronal]NonVerb >> *Dorsal]NonVerb, *Labial]NonVerb |

In Shipibo-Konibo, latent segments surface as dorsal in non-verb forms. Table 3 shows the noun /kapɨC/ ‘alligator’ in its /-N/ form, [ˈka.pɨ.kãN], which in this instance marks ergative. The latent segment is parsed as the onset of the vowel provided by the /-aN/ allomorph. The fixed ranking in (78), with *Labial]NonVerb over *Dorsal]NonVerb, maps the latent segment onto a dorsal consonant, [k].

Table 3.

/kapɨC -aN/→ [ˈka.pɨ.kãN] ‘alligator’ (/-N/form)—Shipibo-Konibo.

Unlike Shipibo-Konibo, latent segments in Capanahua surface as labial in non-verb forms. Table 4 shows that the ergative form of the same noun shown in Table 3, /kapɨC -aN/ ‘alligator’ surfaces as [ˈka.pɨ.pãN] in Capanahua, with the latent segment mapped as a labial consonant, [p]. This result is obtained through the same ranking of constraints but this time, with *Dorsal]NonVerb outranking *Labial]NonVerb.

Table 4.

/kapɨC -aN/→ [ˈka.pɨ.pãN] ‘alligator’ (/N/form)—Capanahua.

When a noun root like /kapɨC/ ‘alligator’ is turned into a verb as in /kapɨC -ai/ ‘(s/he) becomes an alligator’, the latent consonant of the root surfaces coronal, [ˈka.pɨ.ta.i], since its evaluation is, in this case, governed by the ranking in (77) for verb forms and not by that in (78) that is for non-verb forms. This is illustrated in Table 5. The constraints of the ranking in (78) are not shown since they do not receive any violation.

Table 5.

/kapɨC -ai/→ [ˈka.pɨ.ta.i] ‘(s/he) becomes an alligator’ (Shipibo-Konibo).

Section 5 showed that when the nasal /N/ occurs in the final position of morphemes and is syllabified as an onset, the PoA it acquires follows the same pattern observed in latent segments. That is, it surfaces as coronal in verb forms and as non-coronal in non-verb forms. In Capanahua, where latent segments in non-verb forms are mapped onto the labial stop, [p]; the nasal /N/, as expected, is mapped onto [m]: /βinʊN -aN/ → [ˈβi.nʊ.mãN] ‘aguaje’ (/-N/ form). This is because of the ranking of the *Dorsal]NonVerb constraint over the *Labial]NonVerb constraint, which was illustrated in Table 4 for the Capanahua word/kapɨC -aN/ → [ˈka.pɨ.pãN] ‘alligator’ (/N/form).

However, unlike Capanahua, *Labial]NonVerb outranks *Dorsal]NonVerb in Shipibo-Konibo. Thus, latent segments in non-verb forms obtained a default dorsal PoA, [k]. This was shown in Table 3: /kapɨC -aN/ → [ˈka.pɨ.kãN] ‘alligator’ (/N/ form). One would then expect that the nasal /N/ of Shipibo-Konibo would also follow that pattern and surface as a dorsal nasal consonant: [ŋ]. However, this is not the case. In Shipibo-Konibo, the nasal/N/at the end of a morpheme in a non-verb form always surfaces as a labial, [m], in onset position; not as a dorsal. In Capanahua, this makes sense since latent segments in that context are neutralized to labial. However, since Shipibo-Konibo chooses dorsal as the default PoA to neutralize its latent segments in non-verb forms, the occurrence of [m] instead of the velar nasal *[ŋ] is unexpected.

Table 6 shows that the reason why [m] occurs in Shipibo-Konibo is different to why it does so in Capanahua. While in Capanahua, the nasal/N/at the end of a non-verb form surfaces as [m] in onset position because of the ranking *Dorsal]NonVerb >> *Labial]NonVerb; in Shipibo-Konibo, the placeless nasal surfaces as [m] under the same conditions because dorsal nasals are not an option in the language; namely, the dorsal nasal, [ŋ] does not belong to the segmental inventory of the language so any attempt to map /N/ to [ŋ] is blocked. The *ŋ constraint shown in Table 6 encapsulates this prohibition. The nasal /N/ cannot surface faithfully in syllable onsets either since nasals must always have a PoA in that position. Therefore, the only other non-coronal nasal that is available and licit to occur as a syllable onset in non-verb forms is the bilabial one, [m], and that is the one that we observe to occur.

Table 6.

inʊN -aN/→ [ˈβi.nʊ.mãN] ‘aguaje’ (/-N/form)—Shipibo-Konibo.