2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 89 students were recruited from the third-year multi-section Spanish course entitled Spanish Language Skills: Writing, offered at a midwestern university. From the 89 students initially recruited, 76 of them took part in the study. All participants were L2 learners of Spanish, pursuing either a major or a minor in Spanish, attended class regularly, and completed all online submissions on time, including the peer reviewing tasks.

2.2. Procedures: Data Collection

Data were collected from multiple sources, including a background questionnaire, a pre-writing activity, students’ written essay (which included an Outline, a Draft, and a Final Version), and online written peer feedback.

First, the background questionnaire collected demographic information (e.g., age, major, total number of years studying Spanish) and other information regarding students’ experiences writing and peer reviewing in Spanish. Then, the pre-writing activity was administered. The activity was completed during class time, and all course sections met in the Language Media Center of the university equipped with about 60 computers. Students were given 25 min to complete the pre-writing activity: write a narrative based on a story illustrated in six panels. Their responses were submitted via Canvas, the learning management system (LMS) used at the university. Since the writing task was timed and it allowed for the differentiation between the writing abilities of the learners, students’ responses to this activity were considered valid indicators of their initial writing skills. This assessment served the purposes of this study but should not be confused with a more standard measure of language proficiency, such as the ACTFL Writing Proficiency Test.

After finishing the background questionnaire and the pre-writing activity, participants were involved in an online L2 Spanish writing essay focused on a personal narrative. A total of four weeks were dedicated to three topics: (1) teach students about the genre, (2) give them appropriate training, and (3) have them write and submit their essay (Outline, Draft, and Final Version) as well as the peer feedback.

Regarding the teaching sessions (1), and to avoid pedagogical differences between sections, the researcher, together with the support of the instructor of each section, taught and implemented the same teaching module in all six sections of the course. The curriculum during the four weeks of the study was the same across all sections. Thus, the content, teaching style, materials, homework assignments, and the specific examples of the genre used for each phase of the essay (Outline, Draft, and Final Version) were the same across all six sections. This ensured that all students received the same instruction on how to write a personal narrative. The arrangement also allowed students to attend a different class section if, for any reason, they had to be absent from a meeting of their own class. Otherwise, they were asked to schedule an appointment with the researcher to go over the contents covered in class.

Students also received the same peer review and technology training (2). Each of these training processes (i.e., in technology and in peer reviewing) were woven into the teaching curriculum and, therefore, took place throughout the four weeks of the study. Students received training in peer reviewing for both the Outline and the Draft assignments. The training started with a class discussion exercise, and through other critical thinking activities, progressed to providing students with specific tools and resources that would help them give richer, more specific, constructive, and varied feedback. Specifically, the main training tasks included reading, reflecting on, and discussing the principles and values of peer review; practicing with the peer review guidelines for each assignment; discussing the range of different types of comments; and analyzing, commenting on, and discussing peer reviewing techniques on samples of personal narratives.

The technology training allowed students to become familiar with the platform, identify technological issues, and ask for help if they experienced other problems with the platform. The students learned the required procedures to access the peer’s essay and to respond to the peer review guidelines. They also saw demonstrations of the variety of resources offered in the peer review platform and further explored and practiced with them during class time. After training, no additional instructions were added to the peer review activities since students were already familiar with the platform.

Regarding the students’ submissions (3), the writing assignment consisted of narrating a personal experience, which could be a travel adventure, a memorable event, an accident, a life-changing experience, etc. For the assignment, students were asked to write an engaging, interesting, and suspenseful story that would incorporate the key elements of a personal narrative (e.g., title, presentation, rising action, climax, falling action). The specific features of the genre were discussed in class, as part of the content curriculum.

The sources of data obtained from the essay included two drafts, the Outline and Draft assignments, both of which were peer reviewed and revised to result in the Final Version assignment. In other words, the three main steps of the drafting process included: (1) writing the Outline or the Draft assignment; (2) completing a peer review activity using PeerMark software; and (3) making the necessary revisions and adjustments before submitting a newer version of their work. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the same three-step procedure was followed in the Outline phase and the Draft phase. Then, students’ Final Versions were sent to the instructor for a grade.

Data collection ended with students’ submission of their Final Version, which was used as an indicator of their final performance. The grade that each instructor gave to their students, however, was irrelevant for the purposes of this study. This ensured consistency in the students’ assessments, especially because each of the six instructors used their own version of the rubric. Some graded more strictly than others, as instructors often prefer an achievement curve, where all students obtain relatively high grades, rather than a normally distributed curve, where only a few students obtain high and low grades. A normal curve, however, is always preferred in regression analyses.

2.3. Data Management: Online Plantforms and Task Arrangements

All draft submissions (Outline, Draft, and Final Version) and all feedback comments written to the assigned peers were supported by the Canvas platform, the online Learning Management System (LMS) used at the university. Integrated in Canvas, the external tool PeerMark (also known as Turnitin Feedback Studio) was used as the main software for students to carry out the online peer review sessions. The PeerMark platform and its embedded tools offer students scaffolding to provide effective feedback on both local and global issues (

Li and Li 2018). Design features of the Turnitin platform (e.g., commenting tools, composition marks, highlighting) allow students to highlight problematic segments and add explanatory comments. Students can also respond to the instructor’s questions, which guide students on the main elements they need to focus on when giving comments (

Illana-Mahiques 2019a;

Li and Li 2018).

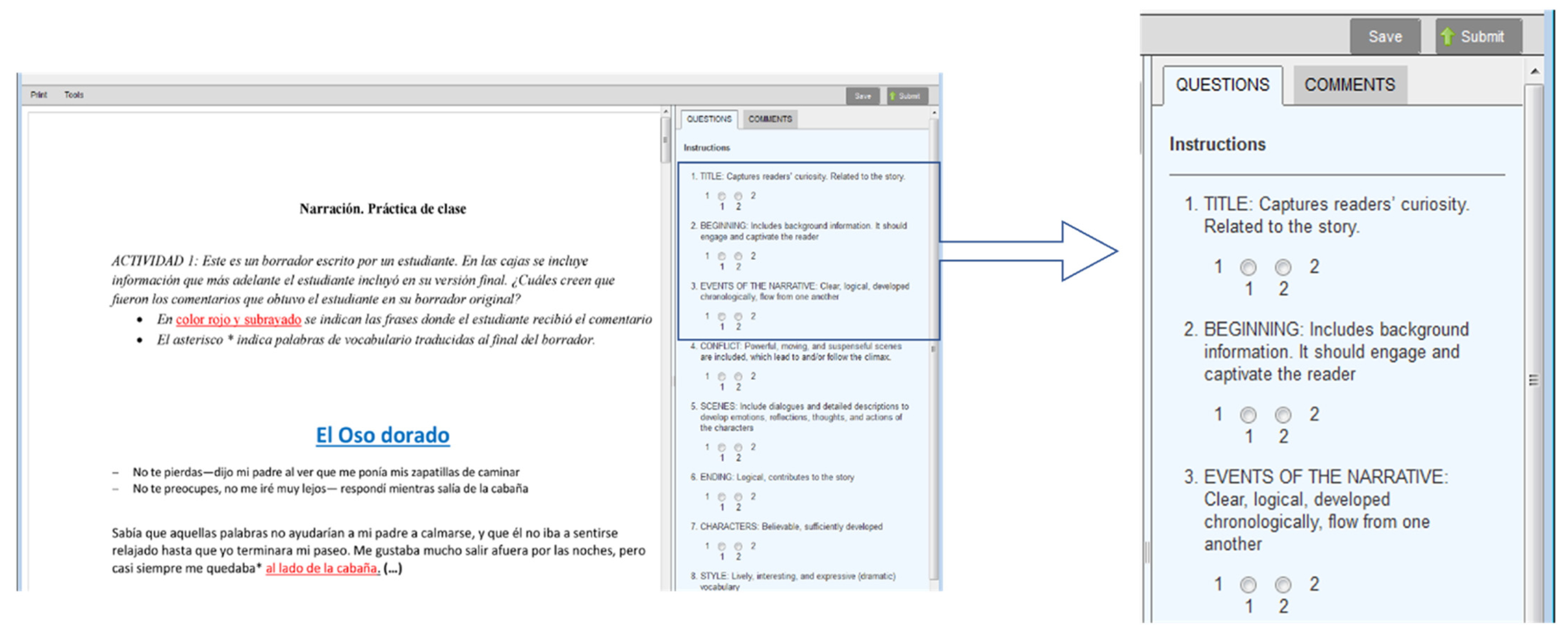

For this project, the peer review guidelines were presented in a checklist format to ensure that students would not miss any criterion. Because PeerMark did not allow for a check off list and required, instead, a minimum of two choices (multiple choice format), the numbers 1 and 2 were used strategically to imitate a check off list format (i.e., 1 = no comment needed for this criterion, 2 = comment added in response to the criterion). The main purpose of this list of criteria was to guide students’ focus towards the main elements of a narration. Student responses to this checklist, however, were not relevant and were not part of the data collection. Thus, for the peer review, only the feedback comments that students wrote were considered part of the data collection.

Figure 2 is an example of what students saw when they opened a peer’s assignment in PeerMark. Then

Figure 3 shows PeerMark’s tools palette, which offers students additional functions, such as including quick marks or changing colors to highlight different areas of the peer’s draft.

Another advantage of the PeerMark is that it can be embedded into various LMS (i.e., Canvas, Blackboard, Sakai) as long as the institution supports the tool. This facilitates students’ work in that they don’t have to navigate to another platform. Similarly, it also assists instructors in planning and managing the peer review activity, while all the data remain recorded within the LMS (

Li and Li 2018). In this case, the software allowed the entire project to take place online and within the Canvas platform. As a result, class time could be spent on issues related to training and task management.

Regarding the structure of the peer review assignment, online sessions were set up to be asynchronous and anonymous. Students completed the tasks at different times and places, and they used their preferred computer. Reviewers’ identities were kept confidential to encourage students to comment more and to provide more honest feedback. To further ensure anonymity, assignments were arranged so that no two students reviewed each other’s paper. Additionally, to enable students to fully participate in the peer review interaction, students were asked to comment in their L1, so their L2 proficiency would not prevent them from fully expressing their ideas (

Ho and Savignon 2007;

Yang et al. 2006).

2.4. Measures of L2 Writing

Measures of writing quality were applied to three of the students’ submissions: (1) the pre-writing activity, (2) the Draft assignment, and (3) the Final Version assignment. Respective to each set of data, (1) writers’ initial writing skills were measured in terms of the assessment score given to their pre-writing activity (an illustrated story); (2) quality of the peer draft was measured by the assessment score given to the peer’s Draft assignment; and (3) writing quality of students’ final performance was defined as the assessment score assigned to the writer’s Final Version. All assessments were conducted after the language writing project was finalized. This helped to avoid any possible bias and maintain similar pedagogical practices across all sections.

The three aforementioned sets of data were assessed in terms of their quality, and two different holistic rubrics were used for their evaluation. A slightly simpler holistic rubric was used to assess the 25-min pre-writing activity (see

Appendix A), whereas both the Draft and the Final Version assignments were assessed with a more detailed rubric that targeted in greater depth the qualities of a narrative (see

Appendix B). The criteria included in both rubrics responded to the genre of the personal narrative. The rubrics not only consider global specifications, such as organization, content, and idea development, but also include local criteria related to language usage (e.g., grammar, sentence structure, vocabulary, and mechanics).

Reliability checks were carried out by comparing the researcher’s ratings with another expert’s rating. After practicing with the rubric, the researcher and the expert rater rated 65% of the data together, discussing possible differences until agreement was reached. The rest of the data were coded by the researcher independently. Interrater reliability was ensured by contacting and training yet a third experienced rater, who in both cases rated a sample (20% of the data) of the pre-writing assignment (r = 0.84, p < 0.01) and the Final Version assignment (r = 0.87, p < 0.01).

2.5. Comment Analysis

Comments from the peer reviewers were segmented into feedback points. A feedback point can be defined as “a self-contained message on a single issue of peer writing” (

Cho and Cho 2011, p. 634). Each feedback point was then classified using a coding scheme similar to that of

Min (

2005) and

Lu and Law (

2012). Specifically, the researchers’ scheme (

Lu and Law 2012;

Min 2005) was adjusted to create a typology that could classify all feedback points collected in this study. To increase validity, changes made to the categories were discussed with two other researchers in the field of L2 writing.

From the comments that the 76 participants gave to the Outline and Draft assignments, a total of 2318 feedback points were categorized into two dimensions: the affective dimension (praise/empathy, explanation of the praise) and/or the cognitive dimension (problem identification, suggestion, alteration, and justification).

The affective dimension refers to general affective perceptions of peer drafts. Positive statements were coded as praise and empathy (P/E) when they appeared as quick formulaic expressions to encourage the writer (e.g., “good job”). Longer statements that explained and summarized the positive aspects of the text were coded as explanation of the praise (EP) (e.g., “I like how you provide a detailed description of the main characters to highlight their personality”).

The cognitive dimension takes a purposeful perspective, informing writers about issues to address in their essay. A feature was coded as

problem identification (PI) if the comment located or pinpointed a specific problem. A feedback point was coded as

suggestion (S) if it provided the student writers with specific advice or a solution to a problem. Feedback comments that addressed language issues (such as word choice or grammar) were tagged as

alteration (A). Statements that clarified the reviewer’s rationale for giving a comment were coded as

justification (J). Finally, a comment was coded as

elaboration (E) when it asked the writer to add more details about a specific issue or event. Intercoder reliability was reached with another coder and 20% of the total data were coded together (r = 0.94,

p < 0.01). Following the same coding model, the researcher coded the rest of the data independently using the adjusted feedback taxonomy (

Lu and Law 2012;

Min 2005) summarized in

Figure 4.

Segmenting all comments from the Outline and Draft assignments into feedback points and then classifying them into categories provided an important data set that was used in the descriptive and the statistical analyses. Thus, for all the analyses conducted in this study, data on student feedback comments refer to the feedback points collected in both the Outline and the Draft assignments.

2.6. Statistical Data Analysis

The data analysis proceeded in several stages. To address Research Question 1, the types of comments that students made (both in the Outline and the Draft assignments) were analyzed in terms of frequency counts through descriptive statistics. For Research Questions 2 and 3, the specific comment types predicting final performance were measured using multiple regression analyses. Specifically, two regression models were used that considered final performance as the dependent variable. Model 1 is more general in that it takes into consideration the total amount of feedback given (independent variable 1) and the total amount of feedback received (independent variable 2). Model 2 is more specific in that it considers the specific types of feedback given. The independent variables (x1, x2, xp) correspond to the raw frequency of each of the feedback types given. Finally, for Research Question 4, additional factors related to giving and receiving feedback (i.e., students’ initial writing skills and quality of peer draft) were taken into consideration in terms of their impact in the reviewing stage. The effects of these two factors in predicting students’ use of specific types of comments were analyzed through a correlation analysis.

3. Results

Participants (N = 76) gave to their peers a total of 2318 feedback points, all of which were classified by type. The types of online feedback given and received, together with other relevant measures from the 76 students, were included in the analysis. Statistical analyses were employed to answer the four research questions. The following sections summarize the findings in relation to each of the research questions guiding the study.

3.1. Summary of Descriptive Statistics: Types of Online Comments Used

Table 1 shows the raw frequency (f), the percentage (pp), and the mean (M) number for each of the comment types provided by reviewers.

The most frequent feedback type was suggestion comments (f = 458, pp = 19.76, M = 6.03) and the second most frequent type was praise and empathy comments (f = 412, pp = 17.77, M = 5.42). The least frequent type of feedback was explanation of praise comments (f = 264, pp = 11.39, M = 3.47) and the second least frequent was problem identification (f = 270, pp = 11.65, M = 3.55).

Overall, and probably due to the influence of peer review training, the different types of comments were generally well distributed. Between the highest and the lowest frequencies, participants gave other types of comments, namely alteration (f = 278, pp = 11.99, M = 3.66), justification (f = 307, pp = 13.24, M = 4.04), and elaboration (f = 329, pp = 14.19, M = 4.33). It should be noted that among the three types of comments, alteration—correcting language errors—was not near the top of the list of comments most frequently used. Students really did focus on content and on offering support and encouragement to their fellow writers.

3.2. Multiple Regression: Predictive Effects of the Online Peer Review Roles

Research Question 2 analyzes whether giving extensive online feedback, receiving extensive online feedback, or both can predict the quality of learners’ Final Version. A multiple regression analysis was used to address this research question. The test for the regression analysis consisted of one dependent variable (y), namely final score, and two independent variables, the total amount of online feedback received (x1) and the total amount of online feedback given (x2). After checking that no significant violations of the regression model were made, the regression coefficients were calculated.

The results displayed in

Table 2 show that, of the two independent variables entered in the model, only the total amount of online feedback given (x

2 = GAVE_Total) was a significant predictor of the participants’ final score (y’ = Final_Score), with a

p-value = 0.01 which is

p < 0.05 on a two-tailed test. The other predictor, namely total amount of online feedback received (x

2 = REC_Total), did not prove to be significant (

p-value = 0.37). Overall, and as shown in

Table 3, the model accounted for 12.8% (R Square) of the variance in the dependent variable.

3.3. Multiple Regression: Predictive Effects of the Online Feedback-Giving by Comment Types

As a follow-up to the results from the previous research question, Research Question 3 analyzes whether giving specific types of online comments can predict the quality of learners’ Final Version. Through a second multiple regression analysis, the writing quality of the participants’ Final Version (y), as measured by the rubric on students’ Final Version (see

Appendix B), was used as the dependent variable, and the distributed tally of all the possible types of online comments given (x

1, x

2, x

3, x

4, x

p) were used as the independent variables.

Adjustments were made to address multicollinearity, so no pair of variables would have a high coefficient (>0.60). Specifically, the variable praise and empathy (PE) was eliminated from the regression module because it was highly correlated with explanation of the praise (EP) comments. This adjustment was found appropriate for two reasons: first, to avoid bringing redundant information into the regression model and, second, to obtain more accurate statistical results without compromising the overall taxonomy, which still captured the affective dimension. After the adjustments, the regression analysis included the student’s final performance as the only dependent variable (y’) and a total of six independent variables (PI, S, A, J, E, EP) corresponding with the types of online feedback given.

As shown in

Table 4, among all feedback given there are three variables with significant contributions to the model: identifying problems (PI) to peers (

p = 0.05,

p < 0.05); justifying (J) a specific comment provided to the peer (

p = 0.036,

p < 0.5); and giving affective feedback that explains a specific praise comment (EP) (

p = 0.003). It seems reasonable that identifying a problem and justifying it contributed to students engaging in activities of higher cognitive demand. The strongest predictor of final performance, however, is explanation of praise (EP). From the giver’s perspective, it is possible that because students focus and engage in what the peer did well, they are able to return to their own work and apply some of the same strategies they praised to their peer’s work. Overall, as shown in

Table 5, the model accounted for 26.2% (R Square) of the variance in the dependent variable.

3.4. Correlation Analyses between Specific Factors and Types of Comments Reviewers Provide

To reveal the factors that may lead students to provide a specific type of feedback, a correlation analysis was carried out.

Table 6 is a summary of the correlation analysis, which shows two types of pair relationships. The first column (Initial_Score) shows the relationship between each type of feedback given and students’ initial writing skills, as measured by the rubric on the pre-writing activity (see

Appendix A). The second column (Peer_Draft_Score) shows the relationship between each type of feedback given and the quality of the peer Draft, as measured by the rubric on the writer’s Draft submission (see

Appendix B). The strength of each relationship is measured in terms of the correlation coefficients.

The results from

Table 6 show only two significant correlations between the different types of comments and the two aforementioned factors of interest: reviewers’ initial writing skills and the quality of the peer’s Draft. The strongest correlation is between giving comments that identify a problem (IP) and the initial writing skills of the reviewer. Then the second strong correlation is between giving suggestions comments (S) and the initial writing skills of the reviewer. In other words, the higher the initial L2 writing skills of the reviewers, the more problem identification (PI) and suggestion (S) comments they gave. The rest of the feedback types did not correlate significantly with either of the factors. That is, the quality of the peer’s Draft did not significantly trigger any particular type of feedback from the peer reviewer.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the types of feedback used most by learners and analyze how inhabiting the roles of online feedback giver and receiver impact learners’ writing performance. Additionally, the influence of other factors, namely the reviewers’ initial writing skills (assessed from the pre-writing activity) and the quality of the peer drafts (assessed from the peer’s Draft assignment), were also considered in exploring in more detail the role of the online feedback giver.

Results in response to Research Question 1 showed that the type of comment most commonly used was suggestion, followed by praise and empathy comments. Conversely, the type of comment used the least was explanation of the praise, and the second least used was problem identification. These results indicate that students offer many suggestions, but the specific problem is not always pointed out. Similarly, students give many formulaic praise and empathy comments (e.g., “good job!”), but an explanation of what in particular is good and why is not always added.

These results inform our training practices, which could teach reviewers about giving more complete, varied, and elaborate comments. For example, training could emphasize the value of pointing out a problem before offering a suggestion, or the value of following up with a praise comment in order to explain what was done well and why. Offering reviewers a clear structure on how to write their comments has been supported in previous research (

Min 2005;

Nilson 2003). Especially in L2 peer reviewing, authors such as

Min (

2005) affirm that a step-by-step procedure “may appear rigid and unnecessary in response groups” but “it is crucial for EFL paired peer review since there is usually little time for reviewer and writer to discuss the written comments” (p. 296). This becomes even more relevant in the online setting, where there is no face-to-face interaction between writers and reviewers.

It is also worth noting that, while the number of alteration comments is relatively high, there is no evidence of students overusing this type of surface comment, which targeted error correction. This may be a result of the peer review training sessions, which prioritized commenting on content, not only on grammar. In fact, it is possible that the greater focus placed on content may have led students to give more suggestion comments. It is also possible that students prioritized this type of comment because they found it easier to make, were already familiar with its structure, or because it was often practiced in the training sessions, which encouraged students to be constructive and to give suggestions on their peers’ work.

Ultimately, and in regard to the overall classification of the online feedback types, descriptive statistics showed that the comments were well distributed among the seven different feedback types. Participants used a variety of online feedback types in a balanced manner, and the relative frequency of each of the categories ranged between 11% and 20%. Thus, despite the peer review being conducted in the online context, none of the feedback types was overused or underrepresented. Instead, students were able to balance out their tendency to comment on surface issues (

Berg 1999b;

Hu 2005;

Levi Altstaedter 2016) and use the array of feedback types available to them (

Illana-Mahiques 2019b). These findings may indicate students’ ability to transfer and apply what they learn from the training to their own online context.

Results in response to Research Question 2 showed that giving online feedback was a significant predictor of the students’ final scores, whereas receiving online comments did not significantly predict final scores. These findings are consistent with previous studies in the field that argue for the benefits of giving feedback (

Cho and Cho 2011;

Lu and Law 2012;

Lundstrom and Baker 2009). Specifically, the findings support the idea that developing analytical skills and learning how to review others’ writing may ultimately lead students to become better writers, more capable of assessing, revising, and improving their own drafts. As

Meeks (

2017) emphasizes in the

Eli Review blog, “giving feedback teaches students something about writing they can’t learn from drafting.”

Cho and MacArthur (

2011) make a similar argument in their learning-by-reviewing hypothesis, which argues that peer reviewing sets students up to carefully assess, judge, and revise their own work, ultimately writing better essays themselves. In the field of L2 learning,

Lundstrom and Baker (

2009) arrived at the same conclusion, claiming that giving feedback is better than receiving, at least in terms of improving L2 learners’ final written performance. The present study, however, confirms similar findings in teaching languages other than English (Spanish) and with the online context as the main space for reviewing and providing comments to their peer’s text.

By exploring in greater depth the role of the feedback-giver, results from Research Question 3 identified three types of online comments that were significant in predicting reviewers’ scores in their own Final Version: problem identification (PI), justification (J), and explanation of the praise (EP). While the bulk of research to support these findings comes from the L1 literature (except for

Lundstrom and Baker 2009), similar explanations may be used in interpreting the findings in the L2 online context and in relation to the three feedback types that appeared as significant.

Giving problem identification comments requires higher cognitive abilities, such as comparing and contrasting, evaluating, and thinking critically about the peer’s text. The purpose is to identify the parts of the text that are problematic, difficult to understand, confusing, misplaced, or that lack additional elements. As students develop the ability to see such problems in the texts they review, it is possible they can transfer their skills as reviewers to themselves as writers so that they can critically self-evaluate their own writing and make appropriate revisions (

Lundstrom and Baker 2009). This finding is consistent with previous research showing that students can learn from critiquing, identifying problems, or providing weakness comments to peers (

Cho and Cho 2011;

Cho and MacArthur 2011;

Lu and Law 2012). As

Cho and Cho (

2011) conclude, “by commenting on the weakness of peer drafts, reviewers can develop knowledge of writing constraints that then helps the reviewers to monitor and regulate their own writing” (p. 639).

Justification comments, which explain in greater detail the reason why something needs to be changed, included, revised, or reorganized, also appeared to be significant in predicting writers’ performance. This type of comment allows reviewers to build on their perspective as readers, and also to articulate further reasons and explanations for the problem identification or suggestion comments. It also requires higher order thinking as they ask reviewers not only to envision the draft that would result from incorporating the suggestions and addressing the problems, but also articulate this process and encourage writers to picture a better version of their drafts. As Meeks states in her blog (

Meeks 2017), “giving feedback is […] cognitively demanding because it asks reviewers to talk to writers about specific ways to transform

the draft that is into

the draft that could be.”

Explanation of the praise appeared as the strongest predictor of final performance. It refers to positive, non-formulaic, and non-generic comments that justify to the writer how or why a specific part of the text is well written. While literature supporting the usefulness of positive comments is inconclusive (

Cho and Cho 2011;

Lu and Law 2012), this study aligns with

Cho and Cho’s (

2011) study. As the authors affirm, through giving positive comments, “student reviewers may gain knowledge of effective writing strategies” (p. 639). This applies to the L2 online context as well. Students not only are able to perform well in the online platform, but as they analyze the features of good writing and become familiar with the writing criteria, they also become more capable of applying some of this knowledge to review and revise their own writing.

These findings strengthen the arguments presented earlier in the discussion about helping students write more detailed and complete comments. Thus, beyond motivating students to use an ample variety of comments, training could give students clear guidance in adding problem identification comments to other kinds of comments (e.g., suggestion comments), or in following up feedback comments with justification or explanation of the praise comments. These more complete and elaborate comments may not only benefit writers but, in agreement with the learning-by-reviewing hypothesis (

Cho and MacArthur 2011), they prompt reviewers to use higher cognitive skills that ultimately lead reviewers to write better essays themselves.

In addition to training, other factors may influence students’ feedback-giving abilities. This issue was analyzed to address Research Question 4. The significant correlation between both giving problem identification comments and giving suggestion comments with the reviewers’ initial writing skills showed that students with higher initial writing skills (as measured by the rubric in

Appendix A) are more inclined to identify problems and add suggestions or solutions to their comments. It is possible that factors such as self-confidence, self-perceived proficiency, assertiveness, and/or knowledge about the topic of the peer’s essay lead students with higher initial writing skills to point out problems and offer solutions. It is also possible that detecting and explaining problems requires more knowledge about writing than giving other types of comments. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies.

Cho and Cho (

2011) found that “the higher the level of writing possessed by the reviewers, the more they commented on problems regarding the micro- and macro-meanings of the peer draft” (p. 637), as opposed to focusing on surface issues.

Regarding the quality of the peer draft, the non-significant correlations show that student reviewers are able to give a variety of feedback types regardless of the quality of the Draft assignment (as measured by the rubric in

Appendix B). These results are relevant in L2 peer reviewing. It would be expected that as higher-skilled writers are able to identify more problems and give more suggestions comments, they would do so in a differentiated manner. That is, lower quality essays would receive less praise and more critiques (e.g., problem identification, suggestions) and, conversely, higher quality essays would receive more praise and fewer critiques (

Cho and Cho 2011). However, based on the non-significant correlations, it seems that reviewers’ criteria for giving problem identification (PI) and suggestion (S) comments does not depend on the quality of the peer draft. That is, problem identification (PI) and suggestion (S) comments were given to both higher quality Draft submissions and lower quality Draft submissions.

A plausible argument that may help explain these findings is that reviewers’ initial writing skills influence reviewing activities in a different manner from that of the quality of the peer draft. Initial writing skills were influential in giving problem identification and suggestion comments, but not in giving positive comments. In contrast, quality of the peer draft was not important in eliciting any particular type of comment, not even problem identification or suggestion comments.

Another interesting finding lies at the interaction of the findings from Research Questions 3 and 4. The findings for Research Question 3 demonstrated that giving online comments such as justification (J) and explanation of the praise (EP) can help student reviewers improve their own drafts. The findings for Research Question 4 further demonstrated that reviewers’ ability to give these types of comments and learn from them is not fully determined by their initial skills. This conclusion is supported by previous studies on the benefits of giving feedback (

Lundstrom and Baker 2009;

Meeks 2016) as well the peer review literature on the effectiveness of giving peer review training (

Berg 1999a,

1999b;

Hu 2005;

Levi Altstaedter 2016;

Min 2005). As suggested in these studies, factors such as peer review training (

Min 2005), student anonymity and engagement in the reviewing activity (

Lundstrom and Baker 2009), as well as frequency and intensity of the review sessions and length of the comments given (

Meeks 2016) may also help explain students’ ability to benefit from the feedback comments they give.

5. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the complexities involved in online peer reviewing, emphasizing the role of the feedback-giver and their final essay scores after they receive appropriate peer review training. Rather than focus on how online feedback affects writers’ revisions, the study demonstrated the learning-by-reviewing hypothesis: the idea that critiquing and giving constructive online feedback to peers actually help feedback-givers write better essays themselves.

The findings obtained in the study also invite us to rethink the notion of feedback and peer reviewing in the online context. First, good-quality feedback should be judged not only in terms of its inputs, features, or conventions, but also in terms of identifiable impacts on learning (

Gielen et al. 2010;

Nelson and Schunn 2008). As shown in the study, the impact of online feedback-giving extends beyond the student receiving the comments to benefit both givers and receivers of online feedback. Second, online peer reviewing should not be understood as a mere process of transmitting information from the reviewer to the writer through a technological platform. Far from being a linear technique, online peer reviewing should be approached from a more organic multilateral perspective that positions both reviewers and writers as active learners engaged in generating feedback loops. That is, the outputs, in this case the online feedback comments given to peers, circle back and become inputs for reviewers to improve their own essay. This way, online feedback comments reviewers give to their writers further feed their own learning, ultimately making them better writers.

This study also shows that the initial writing skills of the learners, as assessed from the pre-writing activity, does not determine the online feedback comments students are able to give. Together with the previous results, these findings have important implications because they suggest that students’ ability to learn from the feedback they give does not depend only on their writing skills. Instead, other practices, such as training, increasing practice, and encouraging students to give longer and more complete feedback can lead reviewers to learn from the feedback they give to their peers (

Meeks 2016).

Finally, it should be mentioned that while the findings of this study help to advance the field of feedback-giving in the online peer review context, much research is still needed in this area. Research focused on better understanding the L2 online peer review context is scarce, and quantitative research that simultaneously analyzes the roles of giving and receiving feedback in a real-life setting is almost non-existent. Therefore, more research is needed that confirms these results and expands our still limited knowledge about students’ roles when engaged in L2 online peer reviewing practices.

6. Directions for Future Research

This research study answered some questions related to feedback-giving practices, but also raised several new questions that could be explored in future L2 peer review research. One of the main findings of this study is that students are able to learn from the feedback they give. However, the specific variables that enhance students’ learning is an area yet to be explored. The study considered the total number of comments given and received, and also the varied types of comments given. Future studies may consider exploring additional variables such as the length and richness of the comments, the language used to convey the feedback (i.e., L1 or L2), the tone employed by the reviewers (e.g., hedging), and the strategies to combine different types of comments, and whether any of these variables help predicting students’ performance in their revised draft.

A related area of interest is analyzing the effects of individual differences or other mediating variables in the reviewer’s feedback-giving abilities. Factors such as initial writing skills and the quality of the peer draft were explored in this study. Future research may consider other factors, such as students’ proficiency level, GPA, or scores obtained in previous L2 courses, and whether these influence the amount and types of feedback that reviewers give to their peers.

Taking a broader perspective, this study explored peer review practices during a four-week period, mainly collecting data on the personal narrative essay. Future researchers may extend their data collection to an entire semester, so that peer review is explored in other writing modalities (e.g., description, exposition, argumentation) or in other genres (e.g., fiction, poetry).

It should also be pointed out that the results obtained in the correlational analyses refer to peer review practices in which students participate as both givers and receivers of feedback. No generalizations should be made to contexts in which students only give, or only receive feedback, or when peer review is done in small groups. Nevertheless, because peer review sessions can be implemented in many ways, it is important for instructors and researchers to be aware of the potential that each arrangement may offer. Thus, more research may be conducted to learn about and explore the different contexts.

Finally, while the results in this study apply to asynchronous online peer review sessions, it cannot be assumed that similar findings will be obtained in synchronous online sessions or in traditional face-to-face settings. Future research may explore in what ways different modes shape the nature of peer review, whether the specific mode selected influences the roles of giving and receiving feedback, and what techniques may compensate for potential difficulties in either of the modes. Additionally, while online feedback and traditional review are very different (

Ho and Savignon 2007;

Tuzi 2004), this does not mean that online feedback practices (synchronous and asynchronous) cannot be valuable complements to face-to-face peer review activities. As emphasized in previous research (

Tuzi 2004), the various forms of feedback should not be understood as isolated or mutually exclusive practices. Instead, and given the different benefits and characteristics associated with each mode, the practices may be combined in many ways. For example,

Chang (

2012) predicts positive benefits from combining the three peer review modes of face-to-face, synchronous, and asynchronous online interaction. However, more research is needed in this area to better understand how different combinations may impact peer review sessions.