Accepting a “New” Standard Variety: Comparing Explicit Attitudes in Luxembourg and Belgium

Abstract

1. Introduction

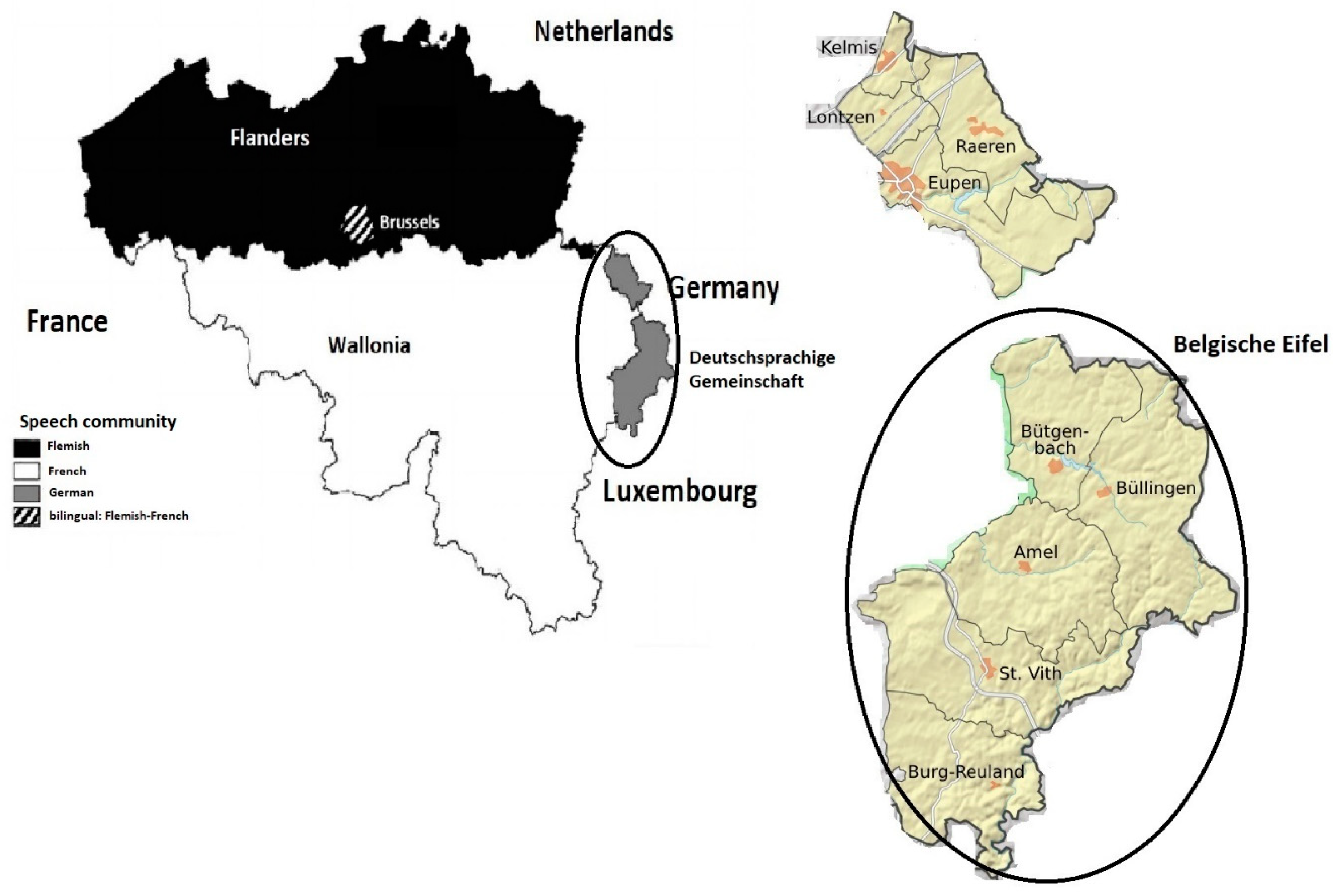

1.1. Belgische Eifel/“Deutschsprachige Gemeinschaft” in Belgium

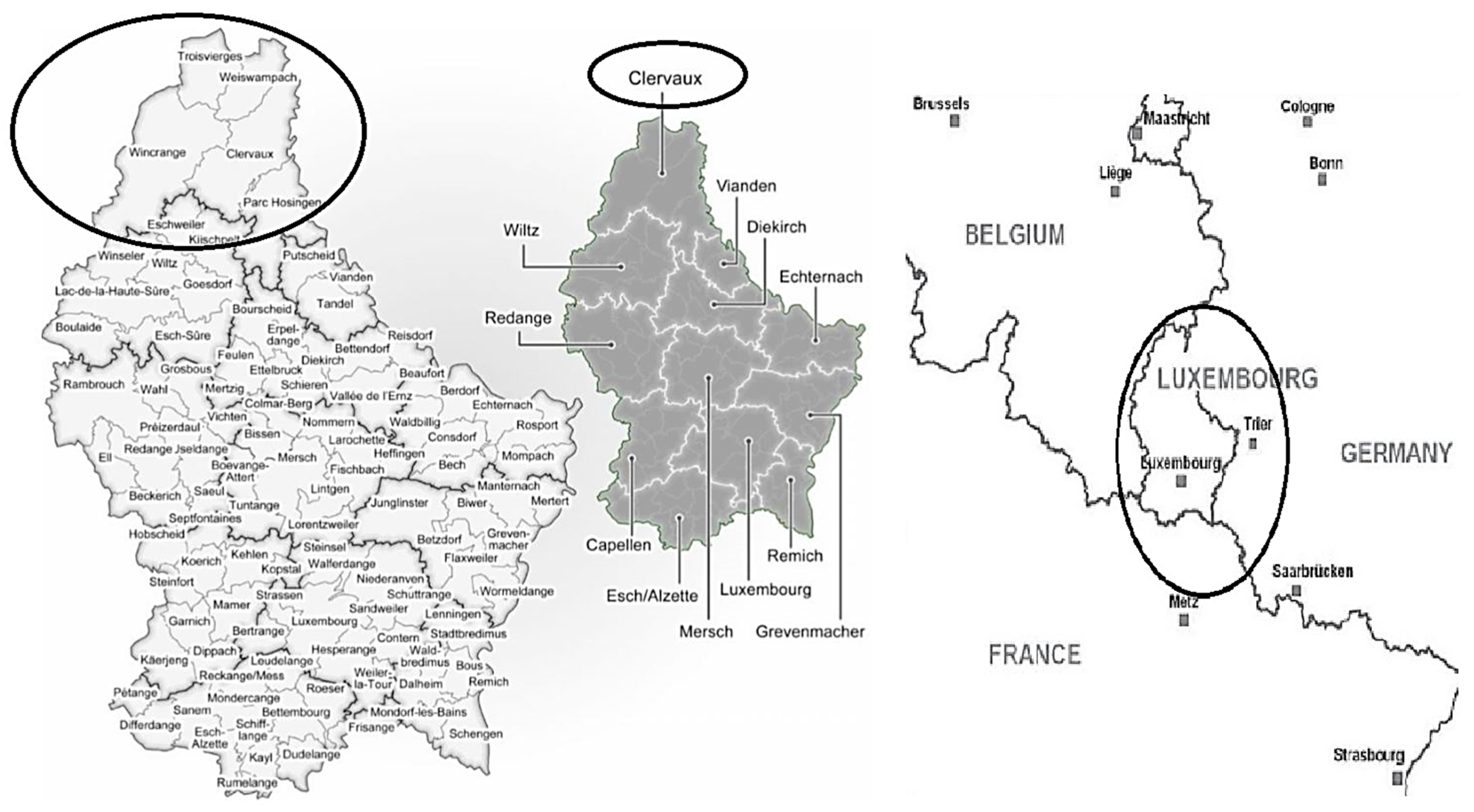

1.2. Clervaux/the Éislek region of Luxembourg

1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

- (a)

- Are explicit attitudes towards Standard German in Belgium more positive than towards Standard Luxembourgish in Luxembourg, as suggested by their different degrees of standardisation?

- (b)

- What are the explicit attitudes towards additional standardised contact varieties, i.e., French in Belgium, and French and German in Luxembourg?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

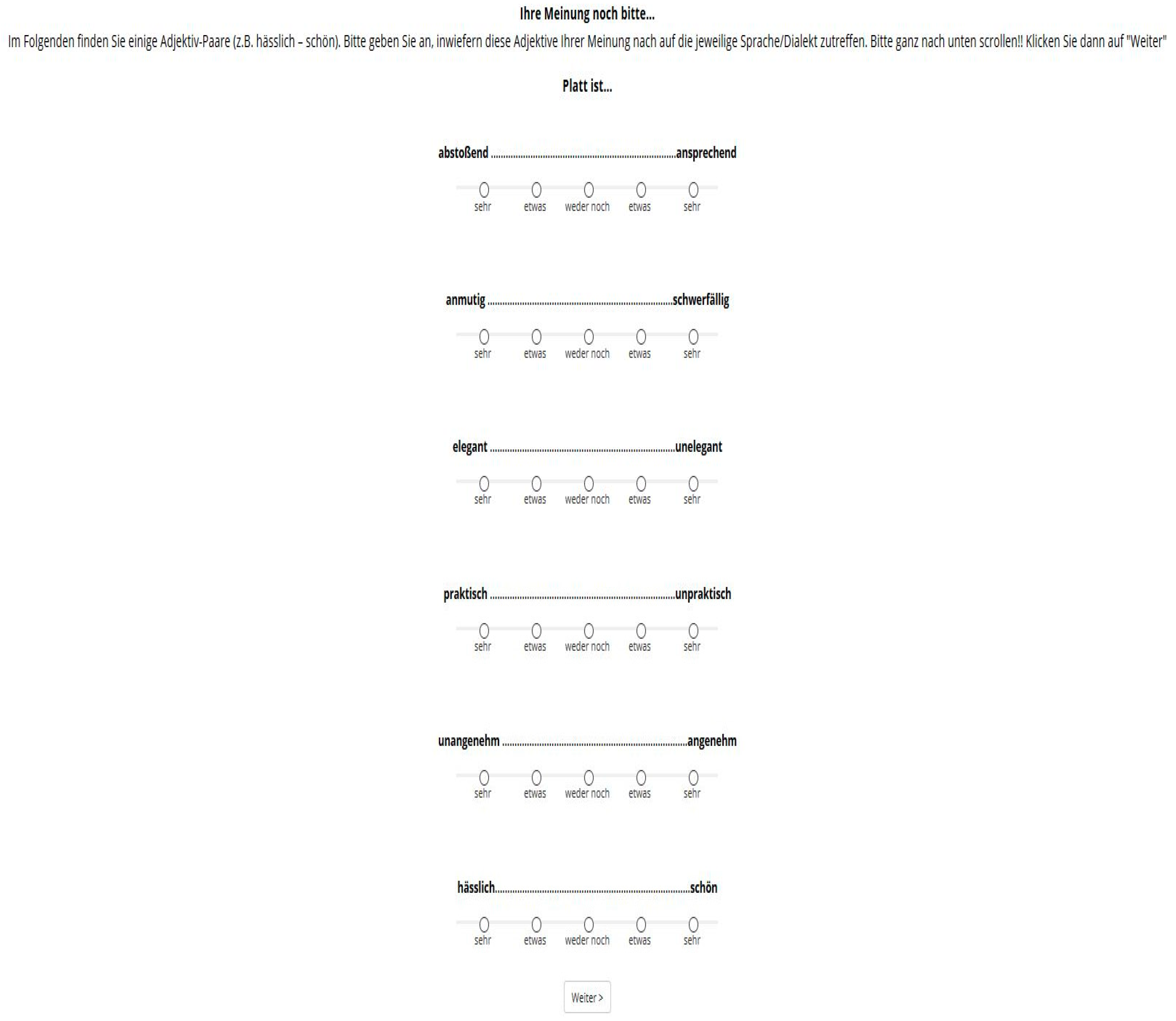

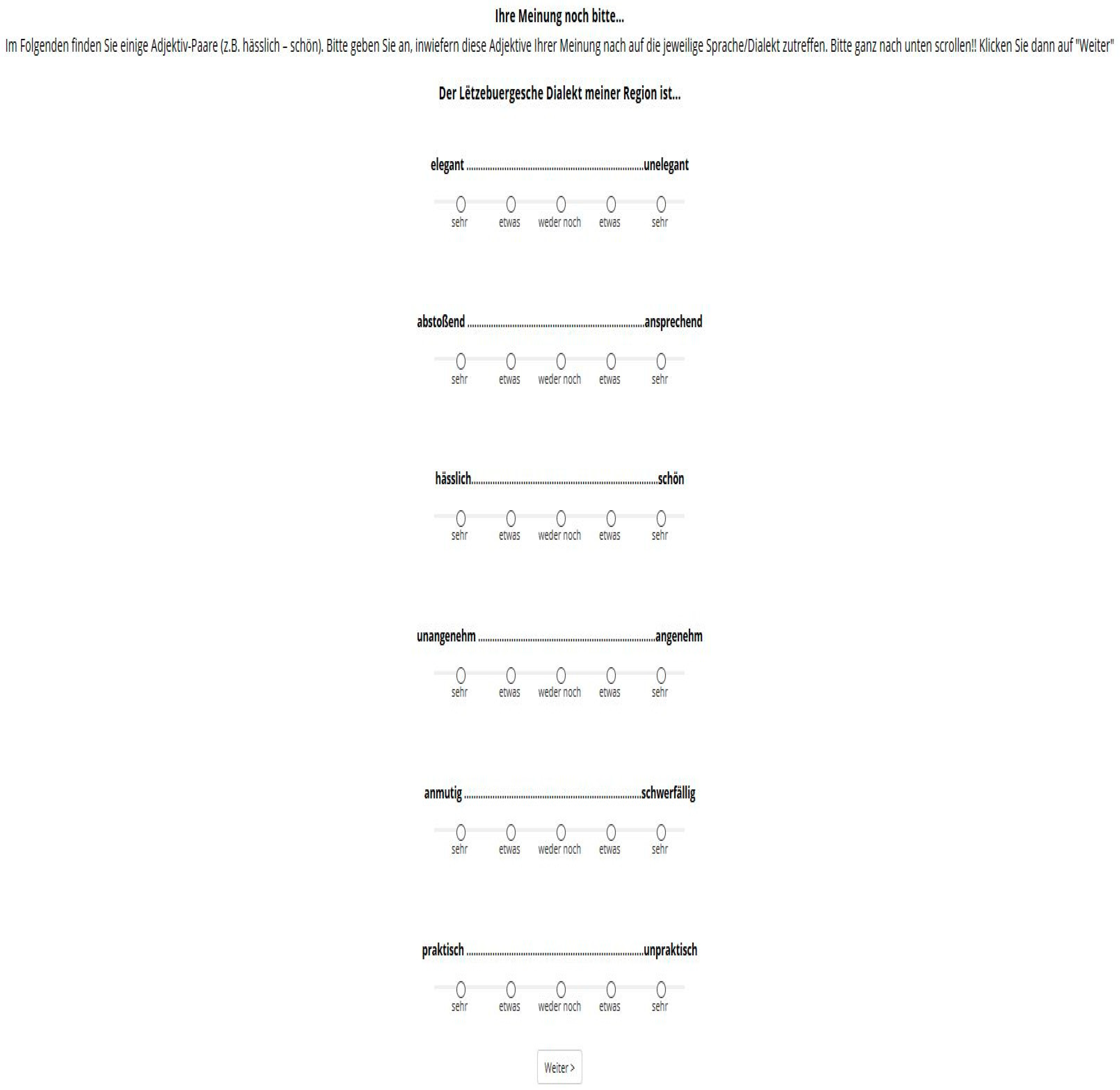

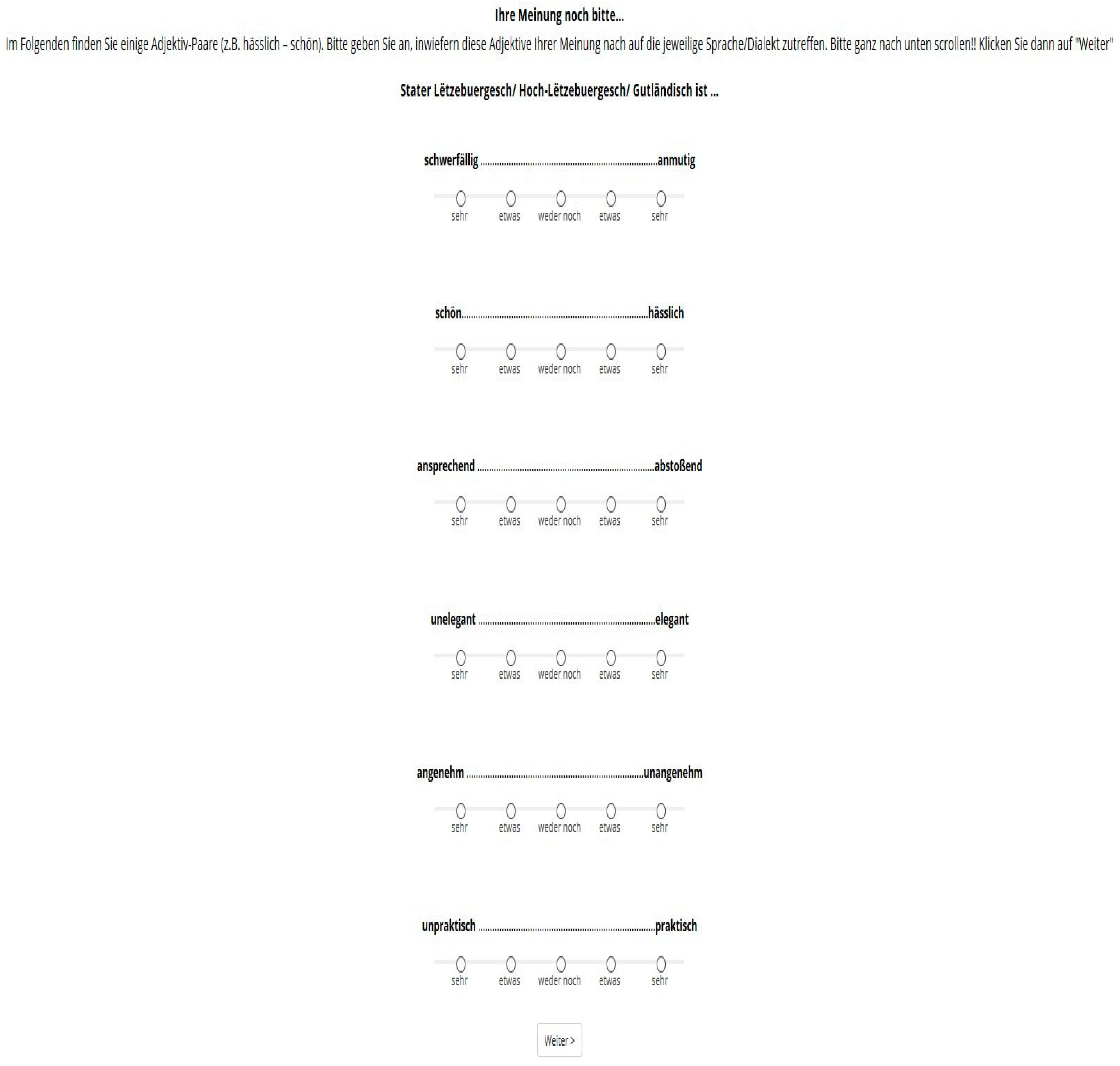

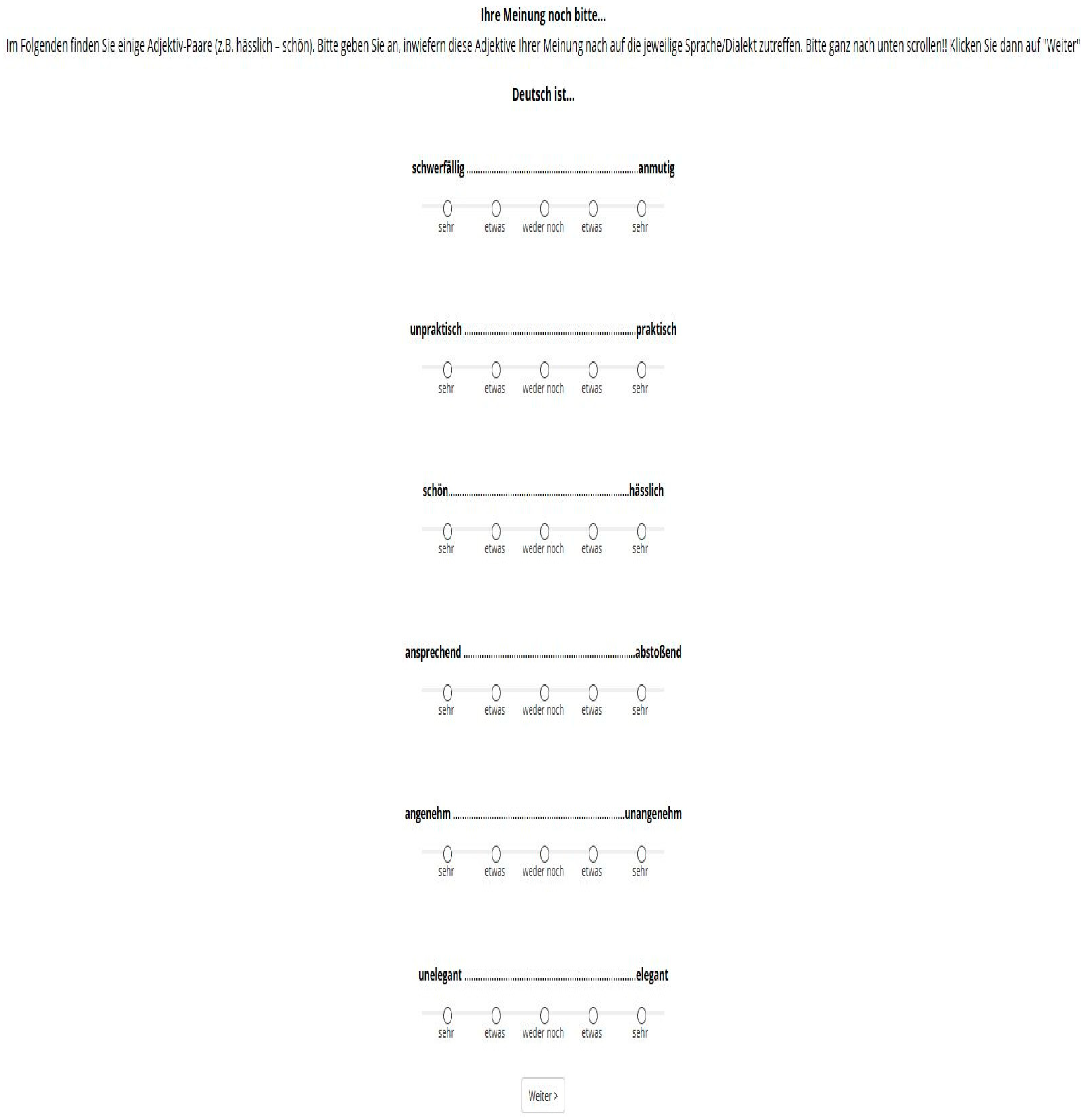

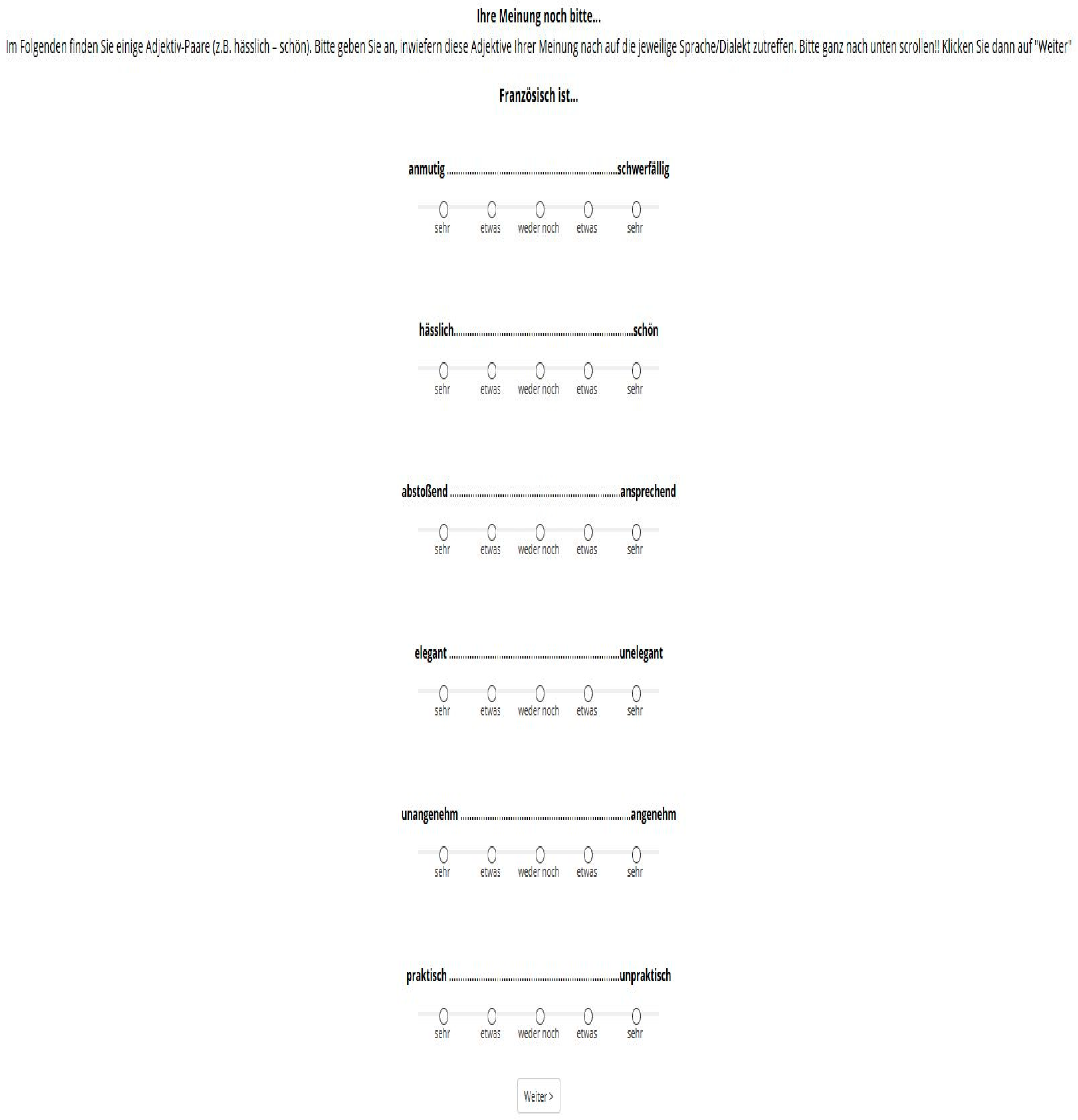

2.2. The Attitudes towards Language (AtoL) Questionnaire

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

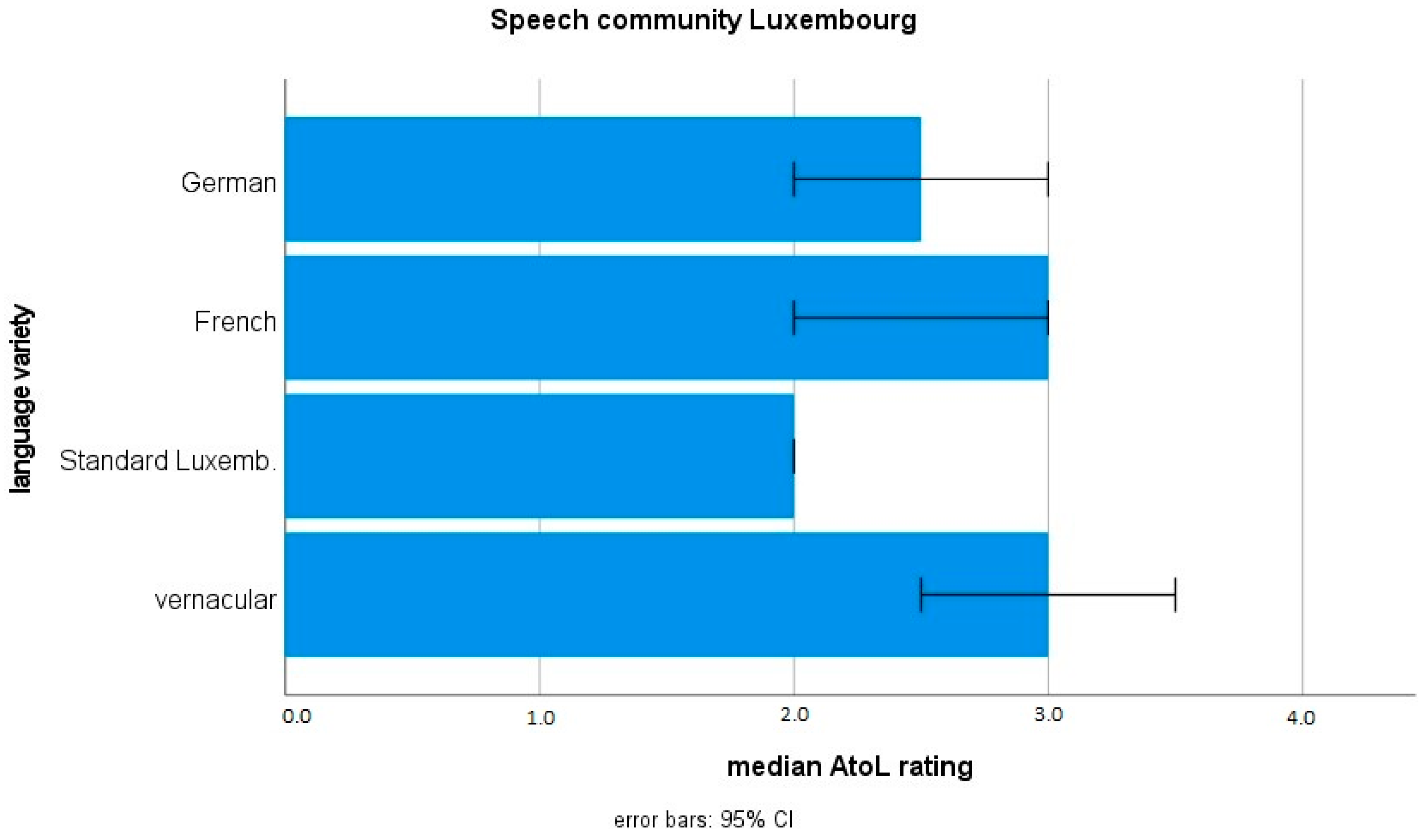

3.1. Within-Speech Community Analysis: Luxembourg

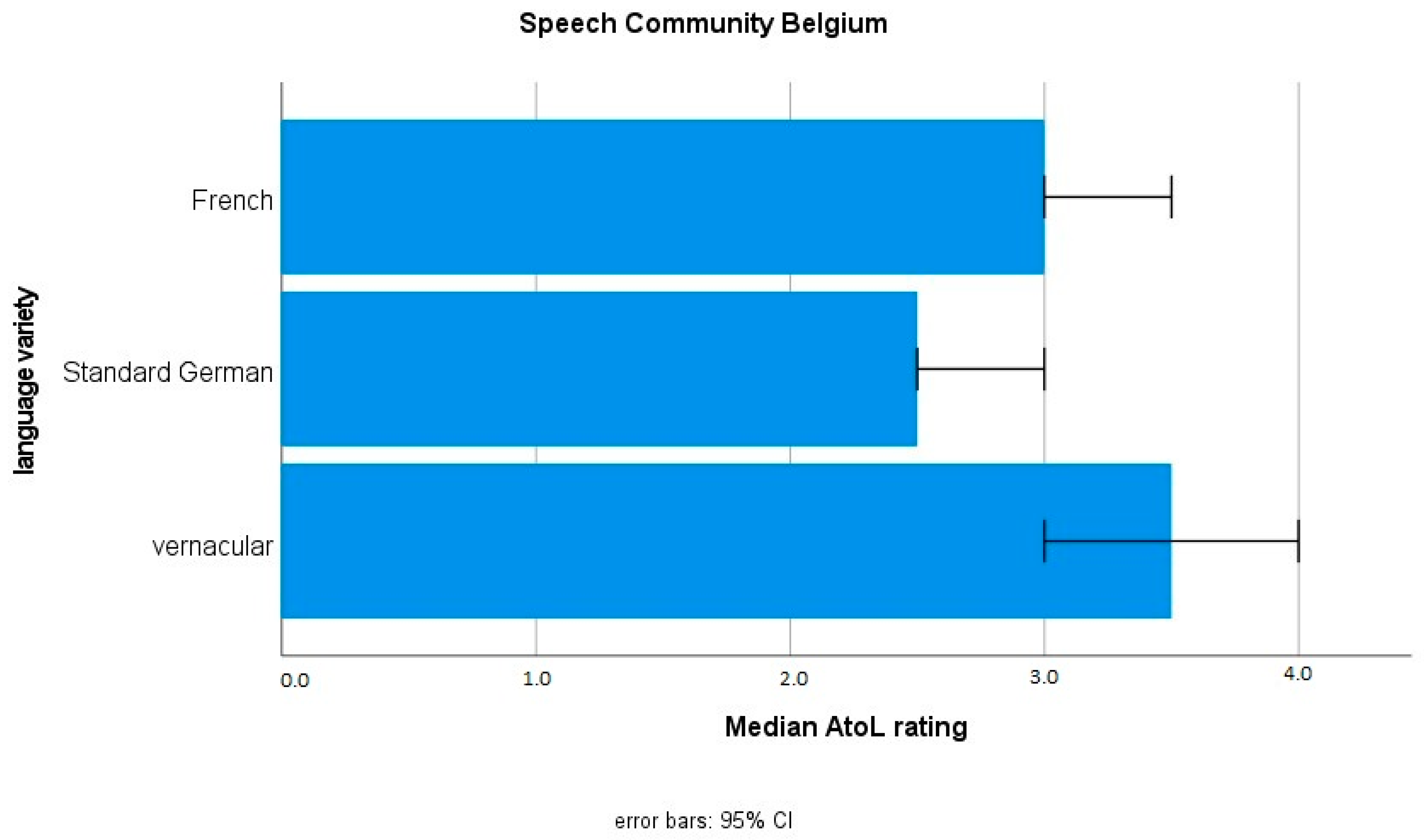

3.2. Within-Speech Community Analysis: Belgium

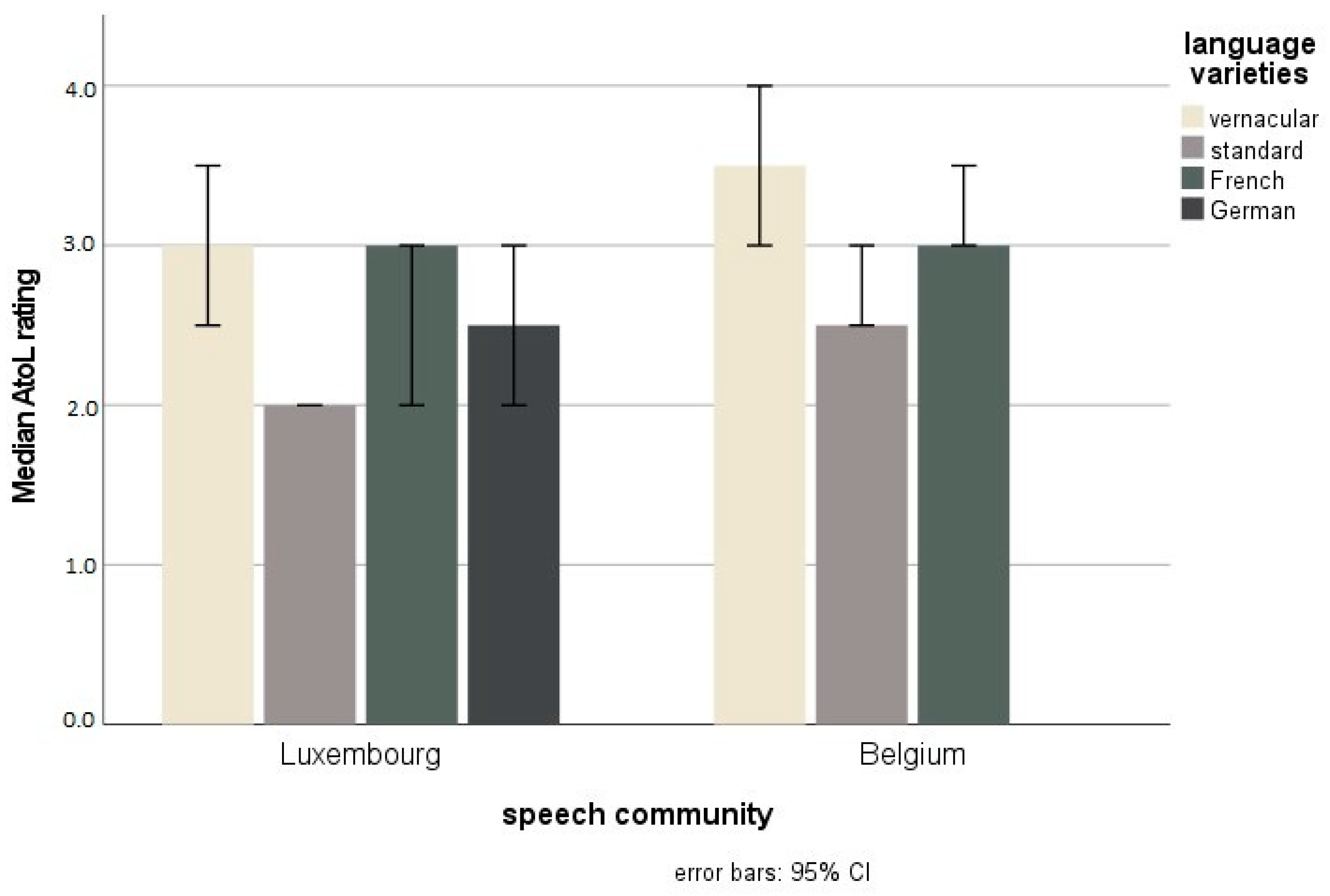

3.3. Between-Speech Community Analysis: Belgium vs. Luxembourg

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | While we will use this denomination in our presentation, the object of our study is Moselle Franconian, a Germanic vernacular spoken in the Deutschsprachige Gemeinschaft and not “German”. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Limburgian-Ripuarian is also identified as vulnerable by UNESCO, but it is Moselle Franconian we are concerned with here. |

| 4 | The language law in 1984 did not use the term “official language”, but it defined Luxembourgish to be the national language, next to German and French, as the languages of administration and judiciary (see Fehlen 2016). |

| 5 | We are very grateful to Nathalie Entringer for having provided us with the raw data of this study, which have not been matched yet with participants’ biographical information, including their place of residence. |

| 6 | Four participants did not complete the norming study, resulting in variability of the provided data for different parts of the study. |

References

- Adams, Zoe. 2019. The relationship between implicit and explicit attitudes to British accents in enhancing the persuasiveness of children’s oral health campaigns. Linguistics Vanguard 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, Astrid. 2019. Language discrimination in Germany: When evaluation influences objective counting. Journal of Language and Discrimination 3: 232–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammon, Ulrich. 1989. Towards a Descriptive Framework for the Status/Function (Social Position) of a Language within a Country. In Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties. Edited by Ulrich Ammon. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 107–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ammon, Ulrich. 1995. Die Deutsche Sprache in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz das Problem der Nationalen Varietäten. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ammon, Ulrich. 2015. Die Stellung der Deutschen Sprache in der Welt. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Colin. 1992. Attitudes and Language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy, John, and Kristine Horner. 2018. Ein Mischmasch aus Deutsch und Französisch: Ideological tensions in young people’s discursive constructions of Luxembourgish. Sociolinguistic Studies 12: 323–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruch, Robert. 1953. Grundlegung einer Geschichte des Luxemburgischen. Luxembourg: Linden. [Google Scholar]

- Cargile, Aaron, Howards Giles, and Ellen Ryan Bouchard. 1994. Language attitudes as a social process: A conceptual model and new directions. Language and Communication 14: 211–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combuchen, Jo. 2009. Deutsch in Belgien. Lebende Sprachen 53: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, James, Haley De Korne, and Pia Lane. 2018. Standardising Minority Languages Reinventing Peripheral Languages in the 21st Century. In Standardizing Minority Languages: Competing Ideologies of Authority and Authenticity in the Global Periphery. Edited by Pia Lane, James Costa and Haley De Korne. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Coupland, Nikolas, and Tore Kristiansen. 2011. SLICE: Critical perspectives on language (de-)standardisation. In Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe. Edited by Tore Kristiansen and Nikolas Coupland. Oslo: Novus Press, pp. 11–35. [Google Scholar]

- Darquennes, Jeroen. 2019. Komplexe Überdachung III: Belgien. In Language and Space: An International Handbook of Linguistic Variation/Band 4: Deutsch. Edited by Joachim Herrgen and Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 1060–76. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Winifred. 2006. Normbewusstsein, Normkenntnis und Normtoleranz von Deutschlehrkräften. In Variation im Heutigen Deutsch: Perspektiven für den Sprachunterricht. Edited by Eva Neuland. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, pp. 483–91. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Winifred. 2018. Sprachnormen in der Schule aus der Perspektive der “Critical Language Awareness”. In Variation—Normen—Identitäten. Edited by Alexandra Lenz and Albrecht Plewnia. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 177–96. [Google Scholar]

- De Groof, Jetje. 2002. Two hundred years of language planning in Belgium. In Standardization: Studies from the Germanic Languages. Edited by Andrew Linn and Nicola McLelland. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 118–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, Jan, and Agnes Moors. 2007. How to Define and Examine the Implicitness of Implicit Measures. In Implicit Measures of Attitudes: Procedures and Controversies. Edited by Bernd Wittenbrink and Norbert Schwarz. New York: Guilford Publications, pp. 179–94. [Google Scholar]

- Deminger, Szilvia. 2000. Spracheinstellungen in einer Sprachinselsituation: Die deutsche Minderheit in Ungarn. In Einstellungsforschung in der Soziolinguistik und Nachbardisziplinen Studies in Language Attitudes. Edited by Szilvia Deminger, Joachim Scharloth, Thorsten Fögen and Simone Zwickl. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, pp. 109–23. [Google Scholar]

- Devonish, Hubert. 2003. Caribbean Creoles. In Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present. Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, and Tatsuya Taguchi. 2009. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing. Florence: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, John, Kerry Kawakami, and Kelly Beach. 2001. Implicit and Explicit Attitudes: Examination of the Relationship between Measures of Intergroup Bias. Chichester: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, John, Kerry Kawakami, Natalie Smoak, and Samuel Gaertner. 2009. The Nature of Contemporary Racial Prejudice: Insights from Implicit and Explicit attitudes. In Attitudes: Insights from the New Implicit Measures. Edited by Richard Petty, Russell Fazio and Pablo Briñol. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 165–92. [Google Scholar]

- Durrell, Martin. 1999. Standardsprache in England und Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 27: 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichinger, Ludwig, and Gerhard Stickel. 2012. Sprache und Einstellungen Spracheinstellungen aus Sprachwissenschaftlicher und Sozialpsychologischer Perspektive. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Entringer, Nathalie, Peter Gilles, Sara Martin, and Christoph Purschke. 2018. [Schnëssen-App—Är Sprooch fir d’Fuerschung]. Unpublished Raw Data. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, Russell, and Tamara Towles-Schwen. 1999. The MODE Model of Attitude-Behavior Processes. In Dual-Process Theories in Social Psychology. Edited by Shelly Chaiken and Yaacov Trope. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Fehlen, Fernand. 2009. BaleineBis: Une Enquête sur un Marché Linguistique Multilingue en Profonde Mutation/Luxemburgs Sprachenmarkt im Wandel. Luxembourg: SESOPI Centre Intercommaunitaire. [Google Scholar]

- Fehlen, Fernand. 2016. Die Luxemburger Mehrsprachigkeit. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Feitsma, Anthonia. 2002. ‘Democratic’ and ‘elitist’ trends and a Frisian Standard. In Standardization: Studies from the Germanic Languages. Edited by Andrew Linn and Nicola McLellend. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 205–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Charles. 1968. Language development. In Language Problems of Developing Nations. Edited by Jyotirindra Das Gupta, Joshua Fishman and Charles Ferguson. New York: Wiley, pp. 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Andy. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (and Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll). London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Joshua. 1991. Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Joshua. 2001. Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, Susan, Amy Cuddy, Peter Glick, and Jun Xu. 2002. A Model of (Often Mixed) Stereotype Content: Competence and Warmth Respectively Follow From Perceived Status and Competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, Robert. 1988. The Socio-Educational Model of Second-Language Learning: Assumptions, Findings, and Issues. Language Learning 38: 101–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, Peter. 2010. Attitudes to Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski, Bertram, Fritz Strack, and Galen Bodenhausen. 2009. Attitudes and Cognitive Consistency: The Role of Associative and Propositional Processes. In Attitudes: Insights from New Implicit Measures. Edited by Richard Petty, Russell Fazio and Pablo Brinol. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 85–117. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Mikaela Marlow. 2011. Theorizing Language Attitudes Existing Frameworks, an Integrative Model, and New Directions. Annals of the International Communication Association 35: 161–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, Howard, and Tamara Rakić. 2014. Language Attitudes: Social Determinants and Consequences of Language Variation. In The Oxford Handbook of Language and Social Psychology. Edited by Thomas Holtgraves. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, Peter. 1998. Virtual Convergence and Dialect Levelling in Luxembourgish. Folia Linguistica. Acta Societatis Linguisticae Europaeae 32: 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, Peter. 1999. Dialektausgleich im Lëtzebuergischen. Zur Phonetisch-Phonologischen Fokussierung einer Nationalsprache. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles, Peter. 2015. From Status to Corpus: Codification and Implementation of Spelling Norms in Luxembourgish. In Language Planning and Microlinguistics from Policy to Interaction and Vice Versa. Edited by Winifred Davies and Evelyn Ziegler. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 128–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles, Peter. 2019. Komplexe Überdachung II: Luxemburg. Die Genese einer neuen Nationalsprache. In Language and Space: An International Handbook of Linguistic Variation/Band 4: Deutsch. Edited by Joachim Herrgen and Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles, Peter, and Jürgen Trouvain. 2013. Illustrations of the IPA: Luxembourgish. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 43: 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles, Peter, Sebastian Seela, Heinz Sieburg, and Melanie Wagner. 2010. Sprachen und Identitäten. In Doing Identity in Luxemburg: Subjektive Aneignungen—Institutionelle Zuschreibungen—Sozio-Kulturelle Milieus. Edited by IPSE-Identités Politiques Sociétés Espaces. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 63–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gramß, Annette. 2008. Die Deutsch-Französische Sprachgrenze in Belgien: Eine Soziolinguistische Studie Links und Rechts der Neutralstraße. Saarbrücken: Vdm Verlag Dr. Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, Anthony, Debbie McGhee, and Jordan Schwartz. 1998. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74: 1464–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenoble, Lenore, and Lindsay Whaley. 2005. Saving Languages: An Introduction to Language Revitalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grondelaers, Stefan, and Paul van Gent. 2019. How “deep” is Dynamism? Revisiting the evaluation of Moroccan-flavored Netherlandic Dutch. Linguistics Vanguard 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondelaers, Stefan, Roeland van Hout, and Paul van Gent. 2016. Destandardization is not destandardization: Revising standardness criteria in order to revisit standard language typologies in the Low Countries. Taal en Tongval 68: 119–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, Einar. 1966. Language Conflict and Language Planning: The Case of Modern Norwegian. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Einar. 1997. Language Standardization. In Sociolinguistics: A Reader. Edited by Nikolas Coupland and Adam Jaworski. London: Macmillan, pp. 341–52. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, Kristine, and Jean Jacques Weber. 2008. The Language Situation in Luxembourg. Current Issues in Language Planning 9: 69–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, Kristine, and Jean Jacques Weber. 2010. Small languages, education and citizenship: The paradoxical case of Luxembourgish. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2010: 179–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, Kristine, and Jean Jacques Weber. 2015. Multilingual education and the politics of language in Luxembourg. In Past, Present and Future of a Language Border. Edited by Catharina Peersman, Gijsbert Rutten and Rik Vosters. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 233–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kloss, Heinz. 1978. Die Entwicklung Neuer Germanischer Kultursprachen Seit 1800, 2nd ed. Düsseldorf: Schwann. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, Tore. 2015. The primary relevance of subconsciously offered attitudes. Focusing the language ideological aspect of sociolinguistic change. In Responses to Language Varieties. Variability, Processes and Outcomes. Edited by Alexei Prikhodkine and Dennis Preston. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, Tore, and Adam Jaworski. 1997. Language attitudes in a Danish cinema. In Sociolinguistics: A Reader and Coursebook. Edited by Nikolas Coupland. Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 291–305. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Wallace, Richard Hodgson, Robert Gardner, and Stanley Fillenbaum. 1960. Evaluational reactions to spoken languages. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 60: 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Wallace, Moshe Anisfeld, and Grace Yeni-Komshian. 1965. Evaluational reactions of Jewish and Arab adolescents to dialect and language variation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2: 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Wallace, Robert Gardner, Romona Olton, and K. Tunstall. 1968. A study of roles and attitudes and motivation in second language learning. In Readings in the Sociology of Language. Edited by Joshua Fishman. The Hague: Mouton, pp. 473–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Pia, James Costa, and Haley De Korne. 2018. Standardizing Minority Languages: Competing Ideologies of Authority and Authenticity in the Global Periphery. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781138125124 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Lehnert, Tessa. 2018. Speaker Evaluations in Multilingual Contexts: The Predictive Role of Language and Nationality Attitudes as Distinct Factors in Explicit and Implicit Cognition. Ph.D. thesis, University Luxembourg, Luxembourg. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Melvyn Paul, and Gary Simons. 2010. Assessing Endangerment: Expanding Fishman’s GIDS. Revue Roumaine de Linguistique 2: 103–20. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro-Rodriguez, Veronica, May Boggess, and Anne Goldsmith. 2013. Language Attitudes in Galicia: Using the Matched-Guise Test among High School Students. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 34: 136–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitz, Péter, and Stephan Elspaß. 2012. Pluralismus oder Assimilation? Zum Umgang mit Norm und arealer Sprachvariation in Deutschland und anderswo. In Kommunikation und Öffentlichkeit. Sprachwissenschaftliche Potentiale Zwischen Empirie und Norm. Edited by Susanne Günthner, Wolfgang Imo, Dorothee Meer and Jan Georg Schneider. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mattheier, Klaus. 2003. German. In Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present. Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 211–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mattheier, Klaus, and Peter Wiesinger. 1994. Dialektologie des Deutschen. Tübigen: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Robert, and Erin Carrie. 2018. Implicit–explicit attitudinal discrepancy and the investigation of language attitude change in progress. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, James. 1991. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, Robert. 2017. Deutsch in Ostbelgien—ostbelgisches Deutsch? In Standardsprache Zwischen Norm und Praxis. Theoretische Betrachtungen, Empirische Studien und Sprachdidaktische Ausblicke. Edited by Melanie Wagner, Winifred Davies, Annelies Häcki Buhofer, Regula Schmidlin and Eva Lia Wyss. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 89–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mulac, Anthony, and Torborg Louisa Lundell. 1982. An Empirical Test of the Gender-Linked Language Effect in a Public Speaking Setting. Language and Speech 25: 243–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muljacic, Zarko. 1989. Über den Begriff Dachsprache. In Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties. Edited by Ulrich Ammon. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 256–78. [Google Scholar]

- Neises, Diane. 2013. Levelling toward a Higher Standard? A Study on Dialect Perception and Its Potential Implications for Language Change in Luxembourg. Master’s thesis, University of York, York, UK. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Nelde, Peter, and Jeroen Darquennes. 2002. German in Belgium: Linguistic Variation from a Contact Linguistic Point of View. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 23: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, Gerald. 1996. Luxembourg and Lëtzebuergesch. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Gerald. 2000. The spelling of Luxembourgish. Systems and developments since 1824. In Essays on Politics, Language and Society in Luxembourg. Edited by Gerald Newton. Lewiston: Mellen, pp. 135–58. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, Bernadette. 2010. Galician and Irish in the European Context: Attitudes towards Weak and Strong Minority Languages. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, Bernadette. 2018. Negotiating the Standard in Contemporary Galicia. In Standardizing Minority Languages: Competing Ideologies of Authority and Authenticity in the Global Periphery. Edited by Pia Lane, James Costa and Haley De Korne. New York: Taylor and Francis, pp. 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, Charles. 1952. The nature and measurement of meaning. Psychological Bulletin 49: 197–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, Dennis. 1989. Standard English Spoken Here: The Geographical Loci of Linguistic Norms. In Status and Function of Languages and Language Varieties. Edited by Ulrich Ammon. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 324–54. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Dennis. 1999. A Language Attitude Approach to the Perception of Regional Variety. In Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology. Edited by Dennis Preston. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 359–73. [Google Scholar]

- Redinger, Daniel. 2010. Language Attitudes and Language Behaviour in a Multilingual Educational Context. The Case of Luxembourg. Ph.D. dissertation, University of York, York, UK. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Laura, and Stefan Grondelaers. 2019. Implicitness and experimental methods in language variation research. Linguistics Vanguard 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Laura, Dirk Speelman, and Dirk Geeraerts. 2018. Measuring language attitudes using the Personalized Implicit Association Test: A case study on regional varieties of Dutch in Belgium. Journal of Linguistic Geography 6: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Laura, Dirk Speelman, and Dirk Geeraerts. 2019. The relational responding task (RRT): A novel approach to measuring social meaning of language variation. Linguistics Vanguard 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothe, Astrid. 2012. Deutsch und andere Sprachen. In Sprache und Einstellungen Spracheinstellungen aus Sprachwissenschaftlicher und Sozialpsychologischer Perspektive. Edited by Ludwig Eichinger and Gerhard Stickel. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 119–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Bouchard, Ellen, and Miguel Carranza. 1977. Ingroup and Outgroup Reactions to Mexican American Language Varieties. In Language, Ethnicity and Intergroup Relations. Edited by Howard Giles. London: London Academic Press for the European Association of Experimental Social Psychology, pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Bouchard, Ellen, Howard Giles, and Richard Sebastian. 1982. An integrative perspective for the study of attitudes toward language variation. In Attitudes towards Language Variation. Social and Applied Contexts. Edited by Ellen Ryan Bouchard and Howard Giles. London: E. Arnold, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidlin, Regula. 2011. Die Vielfalt des Deutschen: Standard und Variation Gebrauch, Einschätzung und Kodifizierung einer Plurizentrischen Sprache. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Schoel, Christiane, and Dagmar Stahlberg. 2012. Spracheinstellungen aus sozialpsychologischer Perspektive II: Dialekte. In Sprache und Einstellungen Spracheinstellungen aus Sprachwissenschaftlicher und Sozialpsychologischer Perspektive. Edited by Ludwig Eichinger and Gerhard Stickel. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 205–27. [Google Scholar]

- Schoel, Christiane, Jennifer Eck, Janin Roessel, and Dagmar Stahlberg. 2012a. Spracheinstellungen aus sozialpsychologischer Perspektive I: Deutsch und Fremdsprachen. In Sprache und Einstellungen Spracheinstellungen aus Sprachwissenschaftlicher und Sozialpsychologischer Perspektive. Edited by Ludwig Eichinger and Gerhard Stickel. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 163–205. [Google Scholar]

- Schoel, Christiane, Janin Roessel, Jennifer Eck, Jana Janssen, Branislava Petrovic, Astrid Rothe, Selma Carolin Rudert, and Dagmar Stahlberg. 2012b. “Attitudes Towards Languages” (AToL) Scale. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 32: 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STATEC. 2019a. Atlas Démographique du Luxembourg. Available online: https://statistiques.public.lu/en/index.html (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- STATEC. 2019b. Population par Commune au 1er Janvier 2019. Available online: https://statistiques.public.lu/en/index.html (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Stell, Gerald. 2006. Luxembourgish Standardization. Louvain-la-Neuve: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1972. Sex, covert prestige and linguistic change in the urban British English of Norwich. Language in Society 1: 179–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2017. UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/index.php?hl=en&page=atlasmap (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Urla, Jacqueline, Estibaliz Amorrortu, Ane Ortega, and Jone Goirigolzarri. 2018. Basque Standardization and the New Speaker: Political Praxis and the Shifting Dynamics of Authority and Value. In Standardizing Minority Languages: Competing Ideologies of Authority and Authenticity in the Global Periphery. Edited by Pia Lane, James Costa and Haley De Korne. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Vari, Judit, and Marco Tamburelli. 2020. Standardisation: Bolstering positive attitudes towards endangered language varieties? Evidence from implicit attitudes. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhiest, Glenn. 2015. Die Deutschsprachige Gemeinschaft Belgiens als visuelle Sprachlandschaft. Germanistische Mitteilungen 41: 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Melanie. 2015. German in Secondary Schools in Luxembourg: The Implementation of Macro-Level Language Policies on the Micro Level of the Luxembourgish German-Language Classroom. In Language Planning and Microlinguistics from Policy to Interaction and Vice Versa. Edited by Winifred Davies and Evelyn Ziegler. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Sandra. 2009. Dialekt in Ostbelgien, Nordrhein-Westfalen und Rheinland-Pfalz. Eine Untersuchung zu Regionalen und Nationalen Unterschieden in der Verbreitung des Dialekts und den Dialektattitüden, Verglichen mit der Sprachsituation in Luxemburg. Master’s thesis, Université de Liège, Liège, Belgium. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Messerich, Jacqueline. 2011. Luxemburgisch als Fremdsprache (LAF). In Linguistische und Soziolinguistische Bausteine der Luxemburgistik. Edited by Peter Gilles and Melanie Wagner. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, pp. 337–45. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, Mervyn, and Christian Jordan. 2009. Mutual influence of implicit and explicit attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45: 748–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesinger, Peter. 1982a. Deutsche Dialektgebiete außerhalb des deutschen Sprachgebiets: Mittel-, Südost-und Osteuropa. In Dialektologie: Ein Handbuch zur Deutschen und Allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Edited by Werner Besch, Ulrich Knoop, Wolfgang Putschke and Herbert Ernst Wiegand. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 900–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesinger, Peter. 1982b. Die Einteilung der deutschen Dialekte. In Dialektologie: Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und Allgemeinen Dialektforschung. Edited by Werner Besch, Ulrich Knoop, Wolfgang Putschke and Herbert Ernst Wiegand. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 807–900. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Timothy, Samuel Lindsey, and Tonya Schooler. 2000. A Model of Dual Attitudes. Psychological Review 107: 101–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolard, Kathryn, and Susan Gal. 2001. Languages and Publics: The Making of Authority. Manchester: St. Jerome. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn, Christopher, and Robert Hopper. 1985. Measuring Language Attitudes: The Speech Evaluation Instrument. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 4: 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, Evelyn. 2012. Language standardization in a multilingual context: The case of German in 19th century Luxembourg. Sociolinguistica 26: 136–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| English | German | Luxembourgish |

|---|---|---|

| VALUE | VALUE | VALUE |

| beautiful–ugly | schön–hässlich | schéin–ellen |

| appealing–abhorrent | ansprechend–abstoßend | uspriechend–ofstoussend |

| pleasant–unpleasant | Angenehm–unangenehm | agreabel–desagreabel |

| inelegant–elegant without style–with style | unelegant–elegant | net elegant–elegant |

| clumsy–graceful | schwerfällig–anmutig | schwéierfälleg–liichtfälleg |

| practical–impractical (L) | unpraktisch–praktisch (L) | onpraktesch–praktesch (L) |

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Estimate | Lower | Upper | SE | Z | p | Odds Ratio |

| age | 0.00423 | 0.01262 | 0.0211 | 0.00860 | 0.492 | 0.622 | 1.004 |

| gender: | |||||||

| male–female | 0.20908 | 0.59500 | 0.1759 | 0.19652 | 1.064 | 0.287 | 0.811 |

| French_competence | 0.21551 | 0.11078 | 0.5433 | 0.16669 | 1.293 | 0.196 | 1.240 |

| Standard_competence | 0.21233 | 0.15370 | 0.5800 | 0.18696 | 1.136 | 0.256 | 1.237 |

| vernacular_competence | 0.30620 | 0.00765 | 0.6213 | 0.16026 | 1.911 | 0.056 | 1.358 |

| speech community: | |||||||

| BELG–LUX | 1.05252 | 0.62855 | 1.4818 | 0.21750 | 4.839 | <0.001 | 2.865 |

| language variety: | |||||||

| Standard–vernacular | 1.43942 | 1.90275 | 0.9838 | 0.23424 | 6.145 | <0.001 | 0.237 |

| French–vernacular | 0.47418 | 0.91824 | 0.0330 | 0.22565 | 2.101 | 0.036 | 0.622 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vari, J.; Tamburelli, M. Accepting a “New” Standard Variety: Comparing Explicit Attitudes in Luxembourg and Belgium. Languages 2021, 6, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030134

Vari J, Tamburelli M. Accepting a “New” Standard Variety: Comparing Explicit Attitudes in Luxembourg and Belgium. Languages. 2021; 6(3):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030134

Chicago/Turabian StyleVari, Judit, and Marco Tamburelli. 2021. "Accepting a “New” Standard Variety: Comparing Explicit Attitudes in Luxembourg and Belgium" Languages 6, no. 3: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030134

APA StyleVari, J., & Tamburelli, M. (2021). Accepting a “New” Standard Variety: Comparing Explicit Attitudes in Luxembourg and Belgium. Languages, 6(3), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6030134