Abstract

Literacy is an essential tool for functioning in a modern society and, as such, it is often taken for granted when developing second language learning curricula for people who need to learn another language. However, almost 750 million people around the world cannot read and write, because of limited or absent formal education. Among them, migrants face the additional challenge of having to learn a second language as they settle in a new country. Second language research has only recently started focusing on this population, whose needs have long been neglected. This contribution presents a systematic review of the classroom-based research conducted with such learners and aims at identifying the teaching practices that have proven to be successful and the principles that should inform curriculum design when working with this population. A first observation emerging from the review concerns the scarcity of experimentally validated studies within this domain. Nonetheless, based on the results of the available literature, this work highlights the importance of contextualized phonics teaching and of oral skills development, which turn out to be most effective when emphasis is put on learners’ cultural identities and native languages.

1. Introduction

According to the most straightforward definition, literacy can be conceived of as the ability to read and write. While a proper definition of literacy is still not unanimously agreed upon (Vágvölgyi et al. 2016; Perry et al. 2017; Perin 2020), current perspectives tend to extend beyond a basic knowledge of written language to encompass the notion of function. Accordingly, literacy comprises not only the ability to read and write, but also the ability to use such skills to function in society. UNESCO, for example, describes literacy as “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves a continuum of learning in enabling individuals to achieve their goals, to develop their knowledge and potential, and to participate fully in their community and wider society” (UIS Glossary). Along this line, according to the OECD, “literacy is defined as the ability to understand, evaluate, use, and engage with written texts to participate in society, achieve one’s goals, and develop one’s knowledge and potential” (OECD 2013, p. 59). While nowadays the term literacy is used also in a broader perspective to indicate knowledge of specific domains such as financial literacy, digital literacy, health literacy, etc., in this review, we will specifically concentrate on print literacy, i.e., understanding and expressing ideas in printed language (Perin 2020). Despite the positive trend highlighted in recent reports by UNESCO (UNESCO 2017, Fact Sheet), which reports a shift from 25% to 10% youth illiteracy over the course of the last fifty years, about 14% of the world’s population remains illiterate, meaning that 750 million adults still lack basic reading and writing skills.

The importance of literacy is evident when we consider the many benefits it brings about for individuals. Resolution 56/116 of the United Nations (United Nations 2002) recognizes the centrality of literacy for lifelong learning, stating that “literacy is crucial to the acquisition, by every child, youth and adult, of essential life skills that enable them to address the challenges they can face in life, and represents an essential step in basic education, which is an indispensable means for effective participation in the societies and economies of the twenty-first century”. Beneficial effects are found in individual (e.g., self-esteem, empowerment, creativity), political (e.g., political participation and democracy), cultural (e.g., cultural openness and preservation of cultural diversity), social (e.g., health, education, gender equality), and economic (e.g., individual income) terms (UNESCO 2006). On the other hand, lack of literacy makes functioning in a society more difficult: those who cannot acquire basic literacy skills have fewer opportunities of employment and income generation, experience higher chances of poor health, and are more likely to turn to crime and/or rely on social welfare (Cree et al. 2012).

A population which is particularly likely to experience such difficulties is represented by people who migrate, particularly those who move from developing to developed societies. According to a recent estimate (The International Organization for Migration—IOM 2020), about 272 million people around the world are migrants. For such people, particularly those whose formal schooling was limited or absent and who migrate to a country where a language other than their L1 is spoken, support to become literate is fundamental in order to actively integrate into the host society. Basic literacy skills appear to be crucially important when considering the intimate connection between such skills and the possibility of learning a second language. Although it is certainly possible to acquire a new language orally, non-literate and low-literate people cannot rely on print materials (e.g., dictionaries) and literacy-based learning strategies (e.g., taking notes) typically utilized by teachers and exploited by learners with a formal education background. Such a claim is supported by the recent findings of second language research, according to which the stronger the literacy skills in the L1, the easier it is to learn a new language (Tarone and Bigelow 2005). Learning a second language is of paramount importance for the migrant who wants to integrate in the new society: knowledge of a second language allows access to the labor market, information, health care, and education, and an understanding of administrative procedures that are key to daily life (IOM 2020). In addition, knowledge of the second language is often vital for those migrants who look to settle permanently in the host country, given the growing tendency for national governments to attach language requirements to the granting of citizenship, and/or the right to residence. Literacy is therefore a key factor to fully participate in the host community, allowing new citizens to advocate for themselves and their families most effectively. While it is theoretically possible to reach the minimum oral language requirements without alphabetic knowledge, it is often the case that official language certifications involve a reading and (sometimes even at the lowest levels) a writing section. Indeed, even requirements for the beginner level of the Common European Framework for languages (A1), on which certifications across Europe are generally based, has been conceived on the assumption that learners possess a minimum amount of literacy skills.

Unfortunately, many of the linguistic courses dedicated to the integration of migrants in the host country are rarely suited to the literacy needs of such individuals. Indeed, even beginner language courses often take for granted basic literacy skills, thus resulting as inadequate and demotivating for those learners who cannot master such abilities. At the same time, despite the predominance of non-literate learner profiles among immigrants and the potential consequences that this condition may have on their life, it appears that non-literate and low-literate learners have been substantially neglected by most scientific research too. Many scholars lament the lack of literacy-related research focusing on this specific profile and on how the lack of basic skills may hinder successful second language acquisition (Bigelow and Tarone 2004; Peyton and Young-Scholten 2020; Tarone 2010; Tarone et al. 2009). On the one hand, research on literacy acquisition has so far focused mostly on children or on adult native speakers’ acquisition. On the other hand, almost all research on second language acquisition has focused on educated, highly literate learners, somewhat implying that the conclusions drawn for such learners may be generalizable for all learners, thereby also for learners with little or no literacy (Tarone 2010). This state of affairs appears to be slowly changing, as more focused attention has been paid recently to such learners both in the field of scientific research (e.g., the recent founding of an organization specifically dedicated to research on this learner profile, Literacy Education and Second Language Learning for Adults—LESLLA) and within the context of international policies on migration-related issues (e.g., the Council of Europe’s recent project LIAM—Linguistic Integration of Adult Migrants).

The present article proposes to review the major contributions developed within this relatively new domain in order to understand which specific instructional strategies might be useful when teaching this population, concentrating on the results provided by classroom-based research conducted with such learners. Condelli and Wrigley (2004a), in a similar review (and so other similar studies, such as the one by Burt et al. 2003), highlighted the paucity of scientifically validated intervention studies conducted with adult illiterate or low-literate second language learners. The authors, who concentrated on the 1983–2003 time period, stress that they could only identify two studies which specifically focused on adult second language learners. Unfortunately, no useful teaching suggestions can be inferred from such studies, since one (Saint Pierre et al. 2003) did not report treatment-control differences, while the other (Diones et al. 1999) is indicated by the authors of the review as having important methodological flaws. We therefore propose to verify whether the growing interest towards this learner profile in more recent years has been reflected in classroom-based research that could help shed light on the effectiveness of specific teaching practices.

Before turning to the discussion of such contributions, we provide a brief overview of the processes involved in reading (for detailed discussion see, e.g., Grabe 2009), focusing on what is known about how low educated second language learner adults (hereinafter, LESLLA learners) develop literacy, and on the specific challenges posed by teaching to such learners (for a more detailed review of such aspects, see Condelli and Wrigley 2004b; Tranza and Sunderland 2009; Bigelow and Vinogradov 2011; and the recent Peyton and Young-Scholten 2020). We then present the studies selected for this systematic review, providing a description of their main characteristics and a discussion of their findings.

1.1. Developing Reading in Adulthood: A Complex Challenge

Learning to read is no mean feat, even when the acquisition process takes place during the first years of schooling. Even though reading might seem simple and effortless to the skilled reader, it is a complex process during which several components intervene and need to be automatized (Perfetti and Marron 1998; Grabe 2009).

A first pre-requisite that needs to be developed is print awareness, i.e., being able to recognize the functions and uses of print, and to understand that there is a relationship between oral and written language (Clay 2000). This ability has been found to be a first important predictor of children’s literacy achievement in their L1 (Johns 1980; McGee et al. 1988). When it comes to the reading abilities themselves, two different types of underlying processes have been proposed: so-called ‘lower-level’ and ‘higher-level’ processes (Grabe 2009). Lower-level processes refer to fast, automatic word recognition skills, which in turn entails orthographic knowledge and knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondences (i.e., decoding skills), syntactic processing (extracting basic grammatical information at the clause-level), and semantic processing of the clause (combining word meanings and structural information into basic units of meaning). Higher-level processes, on the other hand, involve understanding text structure, using inferencing and background knowledge, and monitoring comprehension. The term ‘lower’, in this context, is not to be intended as ‘less important’; on the contrary, lower-level skills constitute a pre-requisite for developing effective higher-level abilities. Automatizing such skills and becoming a fluent reader (i.e., reading with speed and ease) is a key step for the reading process to be successful. Fluency promotes reading comprehension as, since automatic processes require less cognitive effort, more resources can be freed up and consequently allocated for comprehension (Pressley 2006). Therefore, both lower- and higher-level skills are equally necessary and need to interact in a dynamic way.

While we know much about how reading develops during infancy and about effective instructional strategies to boost its development (see, e.g., the research findings reported by the National Reading Panel 2000), much less is known about adult readers who have not acquired or automatized the reading process. Adults may struggle with reading for different reasons, such as specific learning disabilities, lack of educational opportunities, and a different linguistic background. Research on the topic is complicated by the fact that such variables may interact and cannot always be easily disentangled. Nonetheless, attempts to model reading constructs with adults have also been carried out. The study by MacArthur et al. (2010), for example, set out to investigate the reliability and construct validity of measures of reading component skills in a sample of struggling adult learners, finding that the best fitting model was one including measures of decoding, word recognition, spelling, fluency, and comprehension. Among the studies focusing on the models of adult reading, some scholars caution against the widespread tendency of applying child-based assumptions to the adult population (Nanda et al. 2010; Mellard et al. 2010).

Research has indeed highlighted both similarities and differences in the literacy acquisition process of adults and children. On the one hand, it has been claimed that children and adults behave alike in that they both ultimately need to acquire the same set of skills. Research on such issues (Kurvers 2007, 2015; Kurvers and Ketelaars 2011) has demonstrated that children and adults go through the same stages when learning to read, showing that adult beginner readers exhibit the same stage-like behavior proposed for young children (Frith 1985). Specifically, they would start recognizing words first based on contextual clues and memorization of visual images (logographic stage), later passing through a phase in which words are decoded letter by letter and their corresponding sounds blended into a spoken word (alphabetic stage). At a later stage, decoding would be progressively automatized, and words recognized based on their orthographic shapes and matched to an internal orthographic lexicon (orthographic stage). Acquiring the alphabetical principle is thus key to adult reading development too and should be reflected, according to the authors, by appropriate training in the recognition of grapheme–phoneme correspondences.

Another aspect with respect to which adults and children behave similarly, at least to a certain extent, concerns the above-mentioned notion of print awareness. Research has shown that such a skill cannot be taken for granted for non-literate adults, even when they are exposed to print-rich environments, as found by the study by Kurvers et al. (2009). The study, which was conducted on illiterate adult learners who had spent some time in print-rich environments typical of Western societies, revealed that being exposed to printed input is not per se sufficient for learners to develop print awareness, at least not in all its facets. On the other hand, while adults and children looked alike in many ways, the study also showed that adults can bring to the classroom some concepts of print and are not totally oblivious as to its uses and functions. This means that teachers do necessarily need to start afresh when introducing print (Bigelow and Vinogradov 2011).

Despite some similarities between adults and children, there are also specific factors that need to be considered when focusing on the challenges faced by adult emergent readers, especially when they also are second language learners. A first important aspect to consider is literacy in the L1. It is well acknowledged that L1 literacy level is one the factors facilitating learning to read in a second language, since literacy skills acquired in the native language may transfer to the second language and thus help learners experience fewer difficulties (Grabe and Stoller 2011). Even though not all L1 literacy skills are thought to be transferable, being literate in another language brings with it the added benefit of making learners more aware of the strategies that can be used for reading in the second language. Therefore, adults’ lack of literacy in their L1 is likely to impact negatively on their possibilities of success in literacy learning in the L2 (Burt et al. 2003). Secondly, limited proficiency in the L2 further exacerbates the difficulties of the acquisition process. Research has shown that such a variable is an even stronger predictor of L2 reading abilities, in that a minimum threshold of L2 language proficiency level is necessary for skills and strategies to be transferred from the native language (Carrell 1991; Tan et al. 1994). A consistent body of research has confirmed this hypothesis and has found evidence of the interdependence of L2 oral skills and literacy (Tarone et al. 2009; Vinogradov and Bigelow 2010). On the one hand, strong oral language skills help learners develop literacy in the second language (Condelli et al. 2009); on the other hand, literacy skills may boost oral language development. A series of studies conducted by Tarone and colleagues (see Tarone et al. 2007 for review) demonstrated that alphabetic literacy improves conscious processing of linguistic forms. Specifically, adults who had some degree of literacy were better able to perceive and repeat oral corrections. Literacy did not impact on the ability of acquiring new vocabulary during interaction with a native speaker, but corrections concerning the syntactic level were more likely to be neglected by illiterate subjects. Such findings show that learners’ level of alphabetic print literacy might affect the way L2 oral skills are acquired during interaction with other speakers. The implications for teaching are evident: since lack of literacy skills does not only affect literacy development in the L2, but also oral skills development, instruction in alphabetic print literacy should be one of the central components of L2 courses for migrants.

Another known factor correlated to literacy development is phonological awareness, i.e., the reader’s sensitivity concerning the segmentation, identification, and manipulation of L2 sound structures (phoneme, syllable, onset, coda, rhyme). Recognized as an important factor in reading L1 development, phonological skills appear to vary in adult emergent readers depending on which specific subskill is tested. Full phonological awareness comprises awareness of words, syllables, and their subparts (onset and rhyme), but also the more specific component of phonemic awareness, i.e., being able to understand that syllable subparts can be further analyzed in individual consonants and vowel sounds. While the former typically emerges without formal schooling (Peyton and Young-Scholten 2020), the latter is often lacking in adults who did not receive any formal education (Young-Scholten and Strom 2006). Indeed, their performances on phonemic awareness tasks tends to be on a par with that of pre-school children. Moreover, this ability appears to develop only when learning to read in an alphabetic script. Readers of logographic and syllabic systems do not typically possess it, since this skill is not required to read in such systems. This means that even literate learners will not have developed phonemic awareness if their writing system is not alphabetic and will find learning to read alphabetically harder if not provided with training in this skill (Bradley and Bryant 1983; Read et al. 1986). LESLLA learners often face an additional difficulty in developing phonemic awareness: since this skill requires having acquired the phonology of the target language, adults with low oral skills in the L2 will find it even more challenging to develop.

1.2. Teaching Literacy to Adult Second Language Learners

Studies on effective reading instruction practices have been abundant in the last decades, but the bulk of research has been carried out with a focus on children. The findings summarized by the National Reading Panel (2000) highlighted that, in order to be successful, reading instruction should concentrate on the enhancing of decoding skills and phonemic awareness (frequently jointly referred to as ‘alphabetics’), fluency, vocabulary knowledge, and efficient comprehension strategies. Given the similarities characterizing children’s and adults’ path to literacy acquisition, the same core areas were given attention in a seminal review of effective practices in adult reading instruction (Kruidenier 2002). Among the reviewed studies, however, data concerning second language students were often lacking or extremely limited. Though, on the one hand, it has been repeatedly suggested that some techniques can be suitable for instructing non-literate adults, if carefully adapted (Burt et al. 2005; Burt et al. 2008), recent reviews of the literature on adult illiterate L2 learners have pointed out that a separate reading pedagogy for these learners should be implemented (Bigelow and Schwarz 2010; Faux and Watson 2020).

A long-standing debate concerns the viability of phonics instruction (i.e., teaching letter-sound correspondences) for adult learners. The controversy regards the efficiency of two opposite classic methods of teaching reading, the so-called bottom-up versus top-down approaches. The former emphasizes the teaching of phonics encouraging teaching of letters, sound/symbol correspondences, syllables, words, word families, and sentences. This approach focuses less on meaning and more on automatizing the recognition of sound–symbol correspondences. The latter (top-down) starts from the opposite direction, by focusing first on sight recognition of most common words and possibly short sentences, shifting the focus to syllables, sounds, and letters only afterwards. Criticism towards the former of such approaches has stressed that focusing on bits of decontextualized language likely has an impact on motivation and often appears useless to the adult learner. On the other hand, the above-mentioned claim that adult learners go through an alphabetic stage when developing reading skills seems to justify focusing on the teaching of decoding skills. The pedagogical approach currently advocated by many practitioners is a balanced one that combines the best of both the bottom-up and top-down perspectives: since reading is a complex ability implying both top-down and bottom-up processes (Birch 2007), the recommendation is to focus on both skills, engaging students in the reading of meaningful texts, while at the same time explicitly teaching sounds, syllables, and word families (Burt et al. 2008; Vinogradov and Bigelow 2010). A proposal that strives to commit to this recommendation is the so-called whole-part-whole approach (see, e.g., Vinogradov and Bigelow 2010). Teachers present a topic which is relevant to learners, eliciting discussion and providing useful vocabulary on the topic. Once learners are familiar with the topic and its vocabulary, the focus shifts to literacy features, such as symbol–sound correspondences. The activities then shift once again to sharing stories about the topic and practicing oral and written language skills. The advantage of such an approach is that, while emphasis is put on phonics (too), sounds are not presented out of context (e.g., in decontextualized words or in pseudowords, that carry little or no meaning to the learners). As we will see, some of the classroom-based research has indeed tested the validity of such an integrated approach.

Several other studies have pointed out principles that should be considered when teaching this population, sometimes including suggestions for methods and materials for improving literacy and L2 instruction (Florez and Terrill 2003; Vinogradov 2008, 2010; Beacco et al. 2017). However, despite the growing numerosity of such proposals, most studies concentrating on specific approaches for non-literate adults typically report results very vaguely and propose recommendations based on practitioners’ observations which are rarely experimentally tested in a rigorous way. The scarcity of scientifically validated studies is, after all, easily understandable. One of the challenges of conducting research with this population consists in the difficulty of having consistent and reliable data, since such learners typically attend courses for a brief period of time and in a discontinuous way. As noted by Condelli et al. (2009), personal issues related to childcare, lack of transportation, and work commitments are likely to cause such learners to drop out early. Moreover, an additional problem of conducting research on effective literacy practices is represented by the highly heterogeneous variety of literacy profiles teachers commonly find in their classes. Following the classification given in Burt et al. (2008), we can recognize at least six different profiles:

- Non-literate, i.e., learners who have had no access to literacy instruction, which is, however, available in their native country;

- Pre-literate, i.e., learners whose first language has no written form or is in the process of developing a written form (e.g., many American indigenous, African, Australian, and Pacific languages have no written form);

- Semi-literate, i.e., learners with limited access to literacy instruction;

- Non-alphabet literate, i.e., learners who are literate in a language written in a non-alphabetic script (e.g., Mandarin Chinese);

- Non-Roman-alphabet literate, i.e., learners who are literate in a language written in a non-Roman alphabet (e.g., Arabic, Greek, Korean, Russian, and Thai), sometimes with different directions of reading;

- Roman alphabet literate, i.e., learners who are literate in a language written in a Roman alphabet script (e.g., French, German, and Spanish). They read from left to right and recognize letter shapes and fonts.

Naturally, such a heterogeneity of profiles poses serious limitations to the implementation of rigorous experimental research methodologies.

One often-cited work that strived to observe in a scientific way existing classroom practices is the seminal What works study by Condelli et al. (2009), which identified a number of factors affecting English language learning and literacy development of low-literate learners. The study did not test a specific intervention program, but rather looked at existing practices in order to gain an understanding of what factors impact the most on LESLLA learners’ success. Based on data collected from 13 adult programs involving ESL literacy students, the authors identified a number of instructional variables related to students’ learning gains. Specifically, the authors measured students’ gains in three areas: (i) basic reading skills (ii) reading comprehension, and (iii) oral language skills. Four techniques were found to be related to increases in such areas: (i) ‘connection to the outside’, (ii) oral communication emphasis, (iii) use of learners’ L1, and (iv) varied practice and interaction strategies. More precisely, ‘connection to the outside’, i.e., the habit of making connections relating to the world learners are confronted daily, was positively associated with a growth in basic reading skills. On the other hand, reading comprehension was best supported in those classes where students’ native language was used for clarification. Finally, progress in oral L2 skills was observed when teachers used a variety of modalities to teach concepts and allowed student interaction, when they used students’ native language for clarification and when emphasis was put on oral communication activities.

Such recommendations, as we will see, have been taken into consideration and have been implemented in a number of intervention studies, to which we now turn.

2. Method

We conducted a systematic review, following the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. 2009), whose methodology and results will be discussed in this and in the following sections. Specifically, we review a small number of relevant studies that have been conducted with LESLLA learners, reporting and discussing the main findings of classroom-based research. In the present section, we provide details concerning the methodology used to retrieve the relevant studies, while Section 3 and Section 4 present an overview of the main characteristics of the selected studies and a discussion of their main results.

2.1. Search Strategy

We ran a first literature search in May 2020 and, to update the review, we repeated the search process in October 2020 and June 2021. The following electronic databases were consulted: Scopus, Eric (Institute of Education Science) hosted by Proquest, Web of Science, APA PsycInfo, APA PsycArticles, and Academic Search Premier hosted by EbscoHost. The following search terms were used in Abstract, Title, and Keywords:

| (low-literate OR illiterate OR non-literate OR low-educated OR preliterate OR emergent OR “limited schooling” OR “limited literacy” OR migrant OR immigrant) |

| AND |

| (literacy OR writing OR reading) |

| AND |

| (intervention OR training OR practice OR programme OR program OR course OR education OR development OR instruction OR teaching OR approach OR method OR “instructional approach” OR “instructional practice”) |

| AND |

| (“second language” OR L2 OR “language learning” OR “other language”) |

| AND |

| (adult) |

Concerning language, manuscripts written in English were considered for review. As for publication timeframe, since the work by Condelli and Wrigley (2004a) focused on studies published up to 2003, we limited the search to the 2003–2021 time period. In addition to database searching, we also examined the reference lists of the publications under consideration.

2.2. Criteria for Studies’ Selection

Studies were considered eligible for review if they met the following criteria:

- participants had to be adult (aged 16 years old or older) learners of a second language and had to be either non-literate (i.e., they could not read and write neither in their own language nor in any other language) or low-literate (i.e., they attended school but had a reading level below the average primary school level);

- a specific pedagogical intervention aimed at teaching and/or improving the literacy of participating subjects was proposed and its details were clearly described; studies focusing on language development only were excluded;

- literacy levels of participants were measured prior and after the intervention;

- the effects of the proposed intervention were tested on an experimental group of participants and were either compared to those of a control group (exposed to an alternative treatment or no treatment), or not compared to any control group;

- the outcomes of the intervention had to be focused at least partially on literacy-related abilities, which were considered primary outcomes. Following MacArthur et al. (2010), we consider the following five constructs as indicators of literacy levels: decoding, word recognition, spelling, fluency, and comprehension. Any measure related to language proficiency and phonological abilities were considered as secondary outcomes.

3. Results

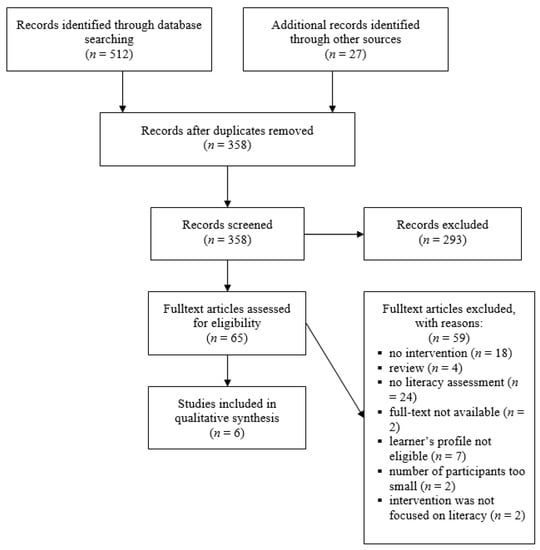

The searches on the above-mentioned databases yielded a total of 512 records. A further 27 studies were found in reference lists of published studies. Of these 539 studies, 181 were removed as duplicates. Abstract screening on the remaining 358 records led to the exclusion of 293 studies. This left us with 65 potentially eligible studies, which underwent full-text examination, concentrating on their research questions and design. Of these, 6 studies met the established inclusion criteria and were therefore selected for review. Figure 1 summarizes the selection process:

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Title and abstract screening as well as full-text screening were carried out independently by the authors, who assessed the studies against the established inclusion criteria. Disagreements were discussed together until a decision was reached.

3.1. Included Studies

We selected four experimental or quasi-experimental studies (Blackmer and Hayes-Harb 2016; Condelli et al. 2010; Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014; Smyser and Alt 2018), in which the efficacy of a specific pedagogical intervention was tested by comparing a treatment group and a control group (exposed to alternate treatment or no treatment), and two studies (Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011; Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos 2007) where, despite the absence of a control group, literacy gains were measured at the end of the intervention.

As for the target language, it is worth mentioning the fact that the majority of the studies concentrated on L2 English, with the exception of two studies (Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011; Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014) on L2 Hebrew. While the proposed teaching strategies may be generalized to the teaching of literacy in other second languages, it is important to stress that English is a language with a deep orthography (i.e., consistency of mapping between letters and sounds is low and irregular words are frequent; Geva and Wang 2001) and therefore phonics interventions might need to differ from those for languages with shallow or transparent orthographies (e.g., Italian, Spanish, German).

3.2. Participants’ Profile

The studies considered included a total of 1515 participants overall (available information about participants of each study is given in Appendix A). Taken individually, they involved different numbers of participants, but they generally included up to one hundred participants. The only notable exception is the study by Condelli et al. (2010), which was conducted on a larger number of learners (n = 1344). One common aspect of many studies is the downsizing of participants during the intervention, mainly due to dropouts (e.g., Blackmer and Hayes-Harb 2016; Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014; Smyser and Alt 2018) or unstable performance on test measures (e.g., Smyser and Alt 2018).

Even though not all the studies report clear information about the age range and average age of the participants, all involved adult learners, 18 years old or older. Participants’ first language backgrounds are not always reported, but appear to be heterogeneous (spanning from Burmese, Arabic, Nepali, Somali, Kunama, and Kirundi to Swahili, etc.) in the majority of the studies (Blackmer and Hayes-Harb 2016; Condelli et al. 2010; Smyser and Alt 2018). Two studies (Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011; Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014) were specifically focused on Ethiopian migrants whose primary language is Amharic.

3.3. Characteristics of Interventions

The proposed interventions exhibit considerable heterogeneity regarding program characteristics and underlying theoretical frameworks, and course duration and intensity. This section provides an overview of such characteristics. The most relevant details of each study are summarized in Appendix B.

3.3.1. Intervention Duration and Intensity

Program durations in the studies considered spanned from 10–12 weeks (Condelli et al. 2010; Smyser and Alt 2018; Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos 2007) to 30–32 weeks (Blackmer and Hayes-Harb 2016; Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011). One study reports longer duration, up to one year (Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014). Total hours of instruction spanned from a minimum of 30/40 h (Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos 2007) to 177 h (Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011). Course intensity varied across the studies, with frequency ranging from two classes (Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011) to four classes (Smyser and Alt 2018; Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos 2007) per week.

3.3.2. Program Implementation: Personnel and Fidelity of Implementation

Most interventions were administered by experienced L2 native teachers, even though not all studies clearly report the level of expertise and/or certification of teachers. One study (Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos 2007) does not clearly indicate whether the researcher or a teacher administered the intervention. Two studies (Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011; Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014) additionally employed participants’ L1 native teachers to support learners’ literacy development in their L1 too.

Half of the considered studies describe steps taken to guarantee the fidelity of implementation (Blackmer and Hayes-Harb 2016; Condelli et al. 2010; Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014). Among such steps, the most frequent appear to be delivering specific teacher training, on site visits aimed at observation and feedback, and researcher–teacher meetings. However, precise information about the evaluation of fidelity of implementation is only provided in the study by Condelli et al. (2010).

3.3.3. Study Quality and Risk of Bias

In order to assess the risk of bias we considered (i) the presence of a control group, (ii) randomization, (iii) measures to ensure fidelity of program implementation, and (iv) use of standardized assessment tools.

Only the study by Condelli et al. (2010) presents all four characteristics and is therefore judged to have a low risk of bias. On the contrary, risk of bias was judged to be high for two studies: specifically, the study by Fanta-Vagenshtein does not meet any of the above-mentioned criteria and the study by Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos (2007) only indicates the use of standardized tests.

In comparison, the studies by Blackmer and Hayes-Harb (2016) and Kotik-Friedgut et al. (2014) are considered to be at lower risk, given that they match two out of four of such criteria.

Finally, the study by Smyser and Alt (2018) does not provide information about the fidelity of implementation. However, it is legitimate to assume that the proposed treatment (PowerPoint presentation of target word stimuli, likely regulated by settings imposed by the researchers) was independent from the teacher’s style of instruction. Therefore, we judged the study as having a low risk of bias.

3.3.4. Characteristics of the Interventions

All studies provided specific details concerning the theoretical framework and principles followed to design the interventions and specifics about the type of practices implemented. We briefly summarize such details for each individual study, before examining their findings. It is worth noticing that not all studies appear to focus on the same literacy level, with some concentrating more on the acquisition of basic decoding skills and others seemingly taking for granted some degree of basic reading skills and focusing on their automatization or on reading comprehension.

The work by Condelli et al. (2010) set out to test the effectiveness of a reading intervention for low-literate ESL learners based on the textbook Sam and Pat. Volume I (Hartel et al. 2006) in improving the reading and English language skills of adults. The textbook was specifically designed for ESL literacy level learners and is based on the methods adopted in the Wilson and Orton-Gillingham reading systems developed for native speakers1 (Wilson and Schupack 1997; Gillingham and Stillman 1997). The teaching methodology adopted in the experimental group integrates from such reading systems the following strategies:

- shifting students systematically and sequentially from simple to complex skills and materials;

- using multisensory approaches to segmenting and blending phonemes (e.g., sound tapping);

- putting emphasis on decoding, fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension; and

- using sound cards and controlled texts (wordlists, sentences, stories) to practice the acquired skills; continuously reviewing in a cumulative fashion the letters, sounds, and words already learned.

Some adaptations were however made to meet the needs of the specific population under investigation. These concerned the sequence in which the sounds of English are taught2, the words chosen for phonics and vocabulary study, the simplification of grammar structures presented, and the addition of systematic reading instruction to ESL instruction. The textbook is not solely focused on the development of basic reading skills, but also integrates language instruction related to basic speaking skills, reading vocabulary, and the basics of English grammar. Content-wise, the textbook strives to establish that connection to the outside which is sought for in adult teaching by proposing content and related vocabulary that is relevant to learners’ daily lives. For both reading and language skills, special attention was dedicated by the authors of Sam and Pat to create carefully controlled materials, so that learners only encounter previously taught phonics patterns, vocabulary, and grammar structures. All in all, according to the authors, this textbook implements the principles identified by the same research group (Condelli and Wrigley 2004a) as promising for fostering literacy development in low-literate learners and differs from traditional ESL instruction (which was administered to the control groups in their study) for the specific attention given to phonics and basic literacy skills that are usually taken for granted and therefore neglected in regular ESL adult courses.

Specific innovations for phonics teaching are proposed in the program developed by Blackmer and Hayes-Harb (2016), which focused primarily on practices having to do with helping learners develop low-level print decoding skills in L2 English. Specifically, the experimental treatment designed by the researchers relied on instructional strategies that involved skills of letter identification, mapping between letters and phonemes, and reading one-, two-, and three-letter words. Details about instructional strategies introduced by their approach and how they differentiate from traditional instruction are very specific and concern the following areas:

- simultaneous introduction of uppercase and lowercase letters (versus uppercase before lowercase), since the latter, being more frequently encountered outside class, may be more useful to learners;

- use of both real and nonsense words (versus only real words), to demonstrate possible letter sequences;

- word reading after the introduction of the first two phonemes (versus 22 phonemes before starting to read), to encourage early development of blending skills;

- early introduction of vowels after four consonants (versus vowels introduced after all consonants);

- teaching phonemes relying on letter cards (versus phoneme–picture association);

- teaching groups of words combining the same letters in different sequences, as in bad, dab (versus use of onset–rhyme word families, such as bad, dad); and

- use of a marking system to help readers decode words (versus no marking system), indicating nonsense words (*daf), direction of reading (arrows from left to right), and vowels (‘x’ under vowels to focus on their pronunciations).

This approach was administered to two experimental groups (two classes with two different teachers) and its effects were compared with those resulting from traditional literacy instruction administered by the same teachers in two other classes functioning as control groups.

Attention to phonics teaching is also acknowledged as important by Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos (2007), which however, highlights potential complications of focusing exclusively on this aspect when working with LESLLA learners. One of the problems highlighted by the authors is the observation reported in Burt et al. (2005) that alphabetics (phonics and phonemic awareness instruction) typically assumes high oral language skills and vocabulary, a condition which is often absent in this specific learner profile. The authors therefore propose a combined approach in which enabling skills training (focus on lower-level skills) and whole language activities (focus on higher-level skills) are integrated. Such methodology is referred to as whole-part-whole approach (see discussion in §1.2). In their study, about half of the weekly load (1.5–2 h) was dedicated to whole language methods and the other half was assigned to phonics and phonemic awareness instruction. Specifically, the focus was shifted to parts of words only after participants learned or were able to recognize such words. Phonics and phonemic awareness activities concerned:

- attention to letter–sound correspondences (30–45 min per week), focusing on a sound of a word and transitioning to other words having the same sound. Attention was given to short vowels, long vowels, digraphs, and consonant blends;

- phonemic awareness activities (10–20 min per week), such as identifying phonemes, rhymes, and blending;

- presentation of onset/rhyme word families (each week, no more details about length of instruction provided), such as pay, say, day.

After focusing on such activities, attention was shifted back to whole words, practiced in a sentence or story context. Content-wise, attention was given to exploiting real life topics during classes (e.g., health, employment, shopping).

Concerns about the possibility of the efficient teaching of phonics are raised in the work by Smyser and Alt (2018). Their study problematizes the choice of phonics-based instruction for illiterate learners, highlighting the fact that developing phonemic awareness presupposes having metalinguistic skills often unavailable to this type of learner. The authors suggest an alternative route to help migrants to develop enough language to complete everyday tasks. Specifically, the proposed treatment aims at developing the skill to recognize and spell words that is independent of meaning and does not rely upon phonology. Such a skill relies on the development of Mental Orthographic Representations (MORs), defined as “stored images of written words in memory” (Apel et al. 2012, p. 2185, as cited in Smyser and Alt 2018). Therefore, they propose a specific treatment that focuses on access to the L2 through a visual mode, rather than focusing on teaching to map sounds to symbols. The underlying assumption is that MORs can be developed without conscious attention being paid during the learning process and without requiring access to the phonemic system. Since initial MOR acquisition has been found to play an important role in early literacy development (it is significantly related to one’s ability to decode words and was found to be a predictor of reading abilities), the authors propose that focusing on the development of MORs in adults with limited literacy might be a viable route to foster learning. To help learners develop stable mental images, the authors therefore suggest drawing on principles of learning theory proposed by Ricks and Alt (as cited in Smyser and Alt 2018), according to which, given the right type of input, humans are able to learn without consciously trying (implicit learning). Specifically, such input should be variable and complex enough. On the one hand, learners need variability to detect and learn phonological, semantic, morphological, and syntactic patterns of language; on the other hand, the linguistic contexts in which target stimuli are presented can be beneficial for visual word processing because complexity helps learners extract information about syntactic categories. The proposed intervention therefore specifically focused on learning a series of words presented to learners in either a high variability/high complexity context or high variability/low complexity context. It is worth noticing that this is the only study, among those here reviewed that does not propose a complete course, but rather a brief treatment to be implemented within the context of standard ESL classes (more precisely, 3 min overall for the high variability/low complexity group and 8 min for the high variability/high complexity group). Written words were repeatedly presented (24 times total each) to learners on a screen and associated with a recorded voice reading the target word. High linguistic complexity was achieved by situating the target word in the context of short sentences of no more than six words, while variability was ensured through the presentation of target words in different sizes and fonts. Participants functioned as their own controls as they were given two lists of words, one which was taught in class with traditional methods (which are assumed to feature low variability contexts) and the other one was taught in one of the two experimental conditions.

The last two studies we describe present interventions specifically conceived for Ethiopian adults emigrated to Israel, learning Hebrew L2 with a background of Amharic L1. The study conducted by Fanta-Vagenshtein (2011) developed a model substantially based on the principles identified as effective by Condelli and Wrigley (2004b). Specifically, attention was dedicated to presenting topics connected the outside world, use of the student’s native language, and use of heterogeneous practices. Therefore, the topics discussed during class were based on real-life material that acknowledged the contribution adult learners bring to the class thanks to their background knowledge and the materials selected were familiar and relevant to the learners’ daily lives and culture. A peculiarity of this program is represented by the use of learners’ first language: the intervention was administered by four instructors, one teacher and one cross-cultural coach for each language (Amharic and Hebrew). Literacy instruction was thus imparted in both the L1 and L2, with half of class time (90 min) focusing on Hebrew and the other half on Amharic. The author stresses the importance of such a choice, within which the L1 teacher was not considered as a mere translator, but on the same level as the L2 teacher. This led to the acknowledgement of each teacher’s individual value in passing on their knowledge to learners and helped foster cooperation in the classroom. It also facilitated establishing a symmetrical dialogue between the two teachers and maximized the use of the two languages as supporting each other. The presence of the two coaches (one for each language) was also stressed for its ability to create collaboration between the L1 teacher, the L2 teacher, and the learners. Another aspect worth mentioning is that students were actively involved in the design of the intervention, as they helped select topics of interest and were consulted about preferred lessons timetables and duration. No specific details about specific reading instructional methods are provided by the author, thus it is unclear whether specific choices were made about basic reading skills teaching.

Some similarities with the study by Fanta-Vagenshtein (2011) are found in the pedagogical approach proposed by the authors in Kotik-Friedgut et al. (2014), based on the cultural-historical Vygotskian approach to learning and on Lurian systemic dynamic neuropsychology (Luria 1973, as cited in Kotik-Friedgut et al. 2014). According to such a theoretical framework, the social context of development needs to be taken into consideration when dealing with the development of knowledge in both adults and children. Pedagogical interventions should therefore maximize opportunities for listening, speaking, reading, and writing, by relying on the learners’ cultural traditional oral knowledge and on their cultural norms and codes. The other underlying assumption is neuropsychological in nature and maintains that, with protracted learning, the plasticity of the illiterate adult brain can allow changes in its functioning, even at later stages in life (Castro-Caldas et al. 1998). Based on the research findings on the effects of illiteracy on cognitive functions3, the authors argue that a set of neuropsychological abilities should be reinforced when teaching a second language to illiterate adults. For this reason, interventions should also comprise non strictly linguistic activities. Specifically, teaching activities should concentrate on phonological abstraction (activities that emphasize phonological awareness), semantic categorization, identification of similarities, visuo-perceptual abilities (spatial exercises, including the spatial orientation of words, spatial discrimination of letters, discrimination of ambiguous pictures), activities that emphasize verbal memory (i.e., recalling sentences), and abstraction abilities and proverb interpretation. In addition to this, following the recommendations by Condelli and Wrigley (2006), the authors recommend using communicative and realistic language materials, especially real-life dialogues using authentic language. They also propose that the initial focus in second language programs should be on oral skills, separating speaking and listening skills from reading and writing skills. Finally, the importance of having a bilingual teacher is stressed, since the use of the learner’s native language for clarification can improve reading comprehension and oral communication skills in the target language. Such recommendations translated into an experimental program in which special attention was dedicated to the development of the basic neuropsychological abilities needed to learn to read, among which are phonological awareness and visual perception. Phonological awareness activities were first introduced in the native language, relying on the L1 oral skills of the participants and then in the L2 target language. Given the difficulties of letter discrimination in Hebrew, participants were also administered visual perception training, aimed at boosting the ability to recognize the relationship between an image and its components. A specific reading software was developed for this aim, to embed phonemes, syllables, letters, words, and language patterns into short- and long-term memory to improve phonological awareness. The software also featured language development activities, presenting authentic everyday dialogues among Hebrew speakers of Ethiopian origin. The topics proposed were ‘survival-related’ and therefore especially relevant to participants. Finally, active involvement of learners’ in curriculum design was ensured through end-of-class reflective feedback sessions, in which participants were stimulated to talk about their difficulties and their success and to express their preferences for subsequent lessons.

3.3.5. Outcome Measures

All the studies under examination measured at least one literacy-related ability before and after the experimental intervention. Specific details on pre- and post-tests are given in Appendix C.

Almost all studies provide at least measures of decoding and/or word recognition, with the exception of Smyser and Alt (2018), which only measured participants’ spelling ability, neglecting all other literacy measures. On the other hand, no other study focused on such an ability. In general, most studies focused on measures of basic reading skills, while fluency and reading comprehension were generally overlooked (except for Condelli et al. 2010 and Fanta-Vagenshtein 2011, which measured reading comprehension). Only two studies (Condelli et al. 2010; Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos 2007) made use of standardized assessment tests, while the remaining specifically designed their own custom tools to assess literacy.

3.3.6. Effects of Interventions on Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Reporting findings that separate primary from secondary outcomes proves difficult for many of the considered studies, since the majority of them tend to either measure progress by collapsing and averaging the different measures or do not clearly report the results for each separate post-test component. We will try, nonetheless, whenever possible, to keep this distinction in the following description of outcomes.

As for primary outcomes, four studies report evidence of gains in literacy-related areas. Kotik-Friedgut et al. (2014) report an overall effect of their program, as improvement in the experimental group was significantly higher relative to the comparison group. Specifically, for what concerns primary outcomes, this effect was found in letter recognition performances. No significant differences were found between improvement scores of the experimental and control groups in the areas of reading familiar and unfamiliar words; however, the initial gaps between the experimental and control groups, which favored the latter in the pre-test, were significantly reduced after the intervention.

Improved decoding skills were also exhibited by participants in the study by Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos (2007): specifically, gains were observed in their ability to decode clusters and short vowels, while long vowels proved to be more challenging.

Improvement in the spelling abilities of participants was found in one of the two experimental conditions of the study by Smyser and Alt (2018). Students benefitted from exposure to the high visual variability/low complexity context for learning new words. On the other hand, no significant gain was observed in the learning of words presented within the high variability/high complexity context.

Finally, it is unclear whether a clear-cut distinction between literacy- and language-related measures was drawn in the study by Fanta-Vagenshtein (2011), who nonetheless reports significant progress made by participants in both their native (Amharic) and target (Hebrew) languages. Improvement was found in both reading and writing. Gains were evident in reading comprehension (from scores of 17.8% to 39.3% in Hebrew and from 17.8% to 63% in Amharic) and in free writing (from 10.7% to 50% in Hebrew and from 7% to 71% in Amharic). In general, the author reports greater progress in the participants’ native language than in the target language.

Two interventions did not obtain the desired impact on literacy development. Results from the study by Condelli et al. (2010) highlight that, on average, students participating in the study made statistically significant gains in literacy-related measures over the course of the term, with 1 to 2 months of growth exhibited. However, no significant difference in learning outcomes was found between the control group, which was taught using standard instruction, and the experimental group, whose instruction was guided by the Sam and Pat textbook. Despite the statistically significant higher proportion of time spent on reading instruction in the experimental group, there were no significant impacts of the experimental intervention on the reading outcomes, not even when considering subgroups based on their L14. When considering subgroups of students based on their initial literacy score, the authors report that those who initially had the lowest scores performed better than students in the control group in one of the decoding measures (Woodcock–Johnson word attack) in the post-test. However, this difference turned out to be not statistically significant. No evidence of an impact of treatment was found in any of the other literacy measures.

A difference between experimental and control groups was, on the other hand, observed in the study by Blackmer and Hayes-Harb (2016), but surprisingly in favor of the latter. When considering all participants together, overall, test scores improved over the course of the study period. However, sub-analyses showed that students taking part in the control classes outperformed those in the treatment condition. All in all, the control group’s progress was substantially greater than that of experimental group. Specifically, while students in the control group learned 23 phonemes and could read 37 words by the end of the project, students in the experimental group learned 10 phonemes and could read 16 real words. Interestingly enough, statistical analyses showed that the effect of the factor Approach was moderated by the factor Teacher, i.e., students in the treatment condition who were taught by Teacher A outperformed students in the treatment condition taught by Teacher B. On the other hand, there was no Teacher effect for the control group.

As for secondary outcomes, three of the four studies which reported literacy gains also found improvement in language-related or phonological abilities measures. Concerning the latter, participants in Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos (2007) were better able to (i) identify the initial sound of a word that was spoken to them, (ii) identify same letter sounds, and (iii) identify words by blending individual sounds. Phoneme identification tests were also administered in the study by Blackmer and Hayes-Harb (2016), but the authors do not mention specific improvement in this area.

Among the studies that more clearly differentiate literacy from language-related measures, Kotik-Friedgut et al. (2014) observed gains in the areas of word and sentence production from pictures, while Condelli et al. (2010) reported 5 to 6 months of growth in language skills when considering all participants that took part into the study, but no significant impact of the experimental intervention on such area. An overview of the main results is given in the following Table 1:

Table 1.

Overview of treatment-control differences in reviewed studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effects of Phonics-Based Teaching

One core aspect of most of the considered interventions was the proposal of some kind of phonics teaching. As we mentioned above, research does not unanimously agree on the efficacy of teaching letter–sound correspondences to adults, arguing how demotivating can be for adult readers starting with the decontextualized presentation of letters and sounds. The study by Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos (2007) tried to circumvent such a drawback, proposing an integrated approach that does not do away with phonics, but suggests starting from words. The findings reported seem to be promising, as at the end of the program, participants showed improvement both in the area of decoding and in phonemic awareness in English. Findings thus indicate that phonics teaching proves to be useful for non-literate learners, provided it is contextualized. On the other hand, among their sample of participants, there were some learners who already possessed some degree of literacy in their L1 and it is interesting to notice how such participants did not show similar improvement. This could indicate that insisting on phonics instruction at more advanced stages of literacy development does not seem to be a particularly effective way to improve fluent decoding. However, as the authors themselves admit, this result might be imputable to the lack of adequate fine-grained measurements used for pre- and post-tests. In other terms, since the decoding skills of L1-literate subjects were already strong at the beginning, the test might have not been adequate enough to capture their progress. In general terms, the results of this study need to be interpreted with caution, since some methodological weaknesses may have impacted the results. On the one hand, the sample of participants (nine subjects, considering both L1-literate and non-literate adults) was by no means large enough to allow generalizations; on the other hand, there was no control group in the study.

Other studies, as we have seen, focused on phonics too, proposing specific modifications to the way it is traditionally taught. Reported findings indicate that such modifications are not always effective, however. Results from the study by Condelli et al. (2010) highlight that, on average, students participating in the study improved over the course of the term. However, from their results, it seems that being exposed to ESL standard instruction or to specific reading instruction guided by the Sam and Pat textbook made no difference. If such results need to not discard the overall efficacy of the proposed treatment, they cannot demonstrate its greater efficacy compared to standard instruction.

Similarly, the findings reported in the study by Blackmer and Hayes-Harb (2016), which introduced some very specific details about how phonics could be taught (such as the early introduction of vowel sounds, the use of a marking system, and a focus on nonwords), do not seem to fully support the effectiveness of the proposed practices, given that learners in the control classes outperformed those in the experimental ones. An important source of information as to why the intervention did not seem to work can be found by also analyzing the qualitative data (i.e., interviews with teachers and students) which were collected throughout the program. Based on such data, we gain an understanding of which specific instructional strategies were well received and what, on the contrary, was felt to be less effective. According to the teachers and the researchers, the main weaknesses of the experimental approach were lack of visual support (no images were used), lack of use of onset–rhyme word families, focus on non-meaningful text (nonsense words), and early introduction of a second vowel. Specifically, the strategy of teaching to read pseudowords, besides real words, was not welcomed favorably by students, who found it confusing and mostly not useful. While teachers recognized the value of nonsense words in evaluating students’ ability to manipulate phonemes, they showed a preference for teaching real words, in agreement with students, as they found that teaching nonwords made the students lose motivation. Furthermore, students in the experimental group appeared to be struggling with the early introduction of a second vowel (specifically, <e> after vowel <a>, which was introduced after teaching 8 consonants and reading 7 words with <a> versus 21 consonants and 23 words with <a> in the control group). The teachers observed that students in the experimental group appeared to be struggling with the strategy of reviewing two vowels (<a> and <e>) at the same time. Students who were given more time to work with the consonants and vowel <a> (control group) were more successful at distinguishing between <a> and <e>. Lack of use of images associated with words’ initial letter was also a strategy disliked by the teachers, who find the use of pictures ‘indispensable’. Finally, the marking system proposed in the experimental approach did not prove particularly effective and, in one teacher’s opinion, had the effect of ‘adding stress’ for the learners, who did not appear to fully understand its purpose. On the other hand, the simultaneous teaching of uppercase and lowercase letters was welcomed by both teachers and students, who expressed their satisfaction, as lowercase letters appear to be more commonly found (for example, in official forms) and are therefore more useful to learners.

Despite the abundance of criticism towards the proposed innovations, it is nonetheless worth reminding the reader that this study found an effect of the Teacher factor for what concerns the experimental groups, i.e., that the intervention designed by the researchers seemed to work better in one of the two groups. This could mean that one of the two teachers administering the experimental approach did not fully implement it, despite steps taken by the authors in order to ensure fidelity of implementation. For this reason, we must remain cautious in concluding that the suggested modifications to phonics teaching did not work out. Additionally, as the authors themselves acknowledge, the small number of participants’ data analyzed (=20) might also have played a role. In general, to such observations it needs to be added that, even though the study did not show particularly positive outcomes, the problem does not seem to be constituted by phonics teaching per se, given that the control group was taught phonics too. The specific strategies proposed, however, did not prove to be successful, at least for beginning readers with a very low level, as the one involved in the study.

Overall, it seems that integrated approaches that combine focus on meaning and attention to word analysis are particularly favored by learners, who exhibit positive outcomes when such methods are implemented. The concerns raised by some scholars (and among the studies reviewed here, Smyser and Alt 2018) about the need for metalinguistic awareness to be able to analyze a word’s smaller units are legitimate as we have seen that, for example, proposing a marking system to LESLLA learners seems to result in additional confusion for them.

On the other hand, for such beginning learners, an approach which could be more effective is the one proposed by Smyser and Alt (2018), who suggest relying on mental orthographic representations (MORs) to foster word recognition and did obtain significant gains in at least one of their treatment conditions. More specifically, the authors found that high visual variability (i.e., presenting the same word written in different fonts and sizes) promotes more learning of MORs (as measured by spelling) than regular classroom activities (typically presenting low variability stimuli). On the other hand, no significant gain was observed in the learning of words presented in highly complex contexts (i.e., not presented in isolation, but inserted in short sentences). What the results highlight is therefore that too much complexity does not appear to benefit learners, as learners might lack adequate familiarity with the L2 syntax, vocabulary, and/or orthography to identify the word in context and develop a stable representation of the word. The authors thus concluded that presenting stimuli with low linguistic complexity and high visual variability promotes the rapid learning of how to spell vocabulary words. Such speed would indicate that learners are able to tap into implicit language learning processes and create stable representations for words. Despite the positive outcome of the study, it is however worth noticing that the study tested treatment effectiveness on a limited number of stimuli (five experimental words), which might question its efficacy in the long term and with larger sets of materials. Indeed, one often cited concern about relying on sight words learning regards its lack of economy and the potential consequences it might have in terms of memory load. In other words, we might wonder how efficient the treatment could be once the number of stimuli starts to increase. Developing orthographic mental representations for words might in our opinion work best if exploited as a starting point for those learners with very limited literacy skills. Such learners might benefit from having a restricted vocabulary store to draw upon to develop word analysis skills. Even though it is unlikely that learners can rely solely on such a method, especially as they progress through courses, such an approach can provide them with a basic orthographic vocabulary to be exploited within integrated phonics instruction.

4.2. Valuing Learners’ Identity

Aside from the issue of phonics instruction, another aspect that was explored by more than one study relates to the possibility of using participants’ native language. As we mentioned above, such practice emerged as a successful strategy in the observational What works study and seemed to be confirmed as such in the two interventions in which L1 instructors were present. The use of L1 is beneficial when used for clarification, but also if used as a direct means for teaching literacy in the native language. Although the performed analyses in the two studies cannot single out which specific factors proved more successful, both interventions differentiate from the others in promoting the use of the learners’ native language, both for clarifying concepts and as a subject for learning literacy. This strategy seemed to be particularly welcomed by participants in both studies and may have been one of the strengths of the programs, in agreement with the findings by Condelli et al. (2009). Interestingly, Fanta-Vagenshtein (2011) reports greater progress in Amharic than in Hebrew. Such a result is not surprising, in the author’s view, given that learners could rely on knowledge of their L1 and did not have therefore the burden of having to learn a new language. It is legitimate to assume that literacy gains in the L2 were (at least partly) a direct consequence of learners learning to read in their own language. As we discussed above, once learners develop reading skills in one language, they can successfully transfer them to another language, at least to a certain extent. This confirms the idea that at least part of L1 literacy skills can indeed be transferrable to the L2 reading development, as put forward in past SLA scholarship. Of course, exploitation of such a strategy is sometimes problematic from a practical point of view, since it naturally requires homogeneous L1 learners’ background, but also the availability of native or near-native teachers (or mediators) of a particular language.

Related to the use of L1 (but not necessarily) is the strategy of promoting learners’ cultural identity, which is beneficial in that it can help the integration of the learner, who feels respected and valued for the cultural contribution s/he brings to the community and finds, in turn, motivation to learn how to function in that community. Open-ended interviews conducted at the end of the course with participants in Fanta-Vagenshtein (2011) confirm this, as they expressed their satisfaction with the course highlighting that, in their opinion, using their native language gave them pride in their culture and motivation to continue studying. Although the study by Fanta-Vagenshtein did not compare participants’ performances against those of a control group, the subsequent study by Kotik-Friedgut et al. (2014), which registered an overall improvement in the experimental group further corroborates the hypothesis that valuing the learner’s identity can be particularly effective with illiterate second language learners.

An additional reason for the registered improvement in both the interventions might have to do with the studies’ shared effort to promote learners’ autonomy, as both programs emphasized efforts to actively engage participants in the course design. On the one hand, such strategies aim to stimulate motivation and make students responsible for their own learning process. On the other hand, listening to the learners’ voices might be beneficial for teachers to better focus on their needs. Another already recommended practice which seems to find validation is that of bringing in the outside. Although we cannot disentangle its effect from those of other instructional practices, such a strategy was integrated in all the interventions that report some kind of literacy (and language) improvement. Selecting content topics (and the materials used for their presentation in class) which are relevant to the daily life of the learners is a strategy which is welcomed by participants and which tends to correlate with positive results in reading development. The advantage of relying on such a strategy, as we have seen, is that it helps keep the learners motivated by focusing on strategic skills which are needed to function in society (for instance, knowing how to fill in documents is instrumental in many of the activities that an adult might typically be engaged in, such as, e.g., registering at an employment office, receiving health care, opening a bank account, etc.). This is confirmed in the qualitative data collected by Kotik-Friedgut et al. (2014). Although the learners’ attitudes about the importance of learning the L2 were similar in both the control and program groups, the perception of language proficiency and self-efficacy was significantly higher in the experimental group. Students in the experimental group were more confident in their ability to read street signs and read newspaper headlines in Hebrew, complete personal questionnaires, and interview for a job.

4.3. Promoting Oral Communication

Finally, focusing on oral communication skills also proves to be effective, not only for improving oral linguistic competence, but also for developing literacy skills. Trupke-Bastidas and Poulos (2007) discuss this when observing that learners who benefitted the most in their intervention were those who had strong oral skills and were willing to communicate with others, confirming that oral skills can boost literacy development. Although the idea of concentrating on oral communication activities to foster literacy may sound counterintuitive, the fact that interventions that put emphasis on such activities prove successful for literacy too corroborates the claims by Tarone and colleagues on the close connections between oracy and literacy skills.

4.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The present review has some limitations that can inspire future research. Firstly, a potential concern pertains to the restricted number of studies that were selected for review and discussion. On the one hand, such a small number was determined by the inclusion criteria which specifically focused on research which was experimentally validated. We acknowledge the presence of a growing number of studies addressing the issue of best LESLLA teaching practices and the valuable suggestions such studies may offer. Hopefully, future research will provide experimental evidence to support the effectiveness of such proposals. On the other hand, we acknowledge that a possible explanation for the small number of found studies resides in the decision to limit the search to studies that were published in English, which leaves out the potentially good suggestions coming from locally published studies.

Secondly, this review does not discuss the potential advantages of using technology-enhanced learning systems to support literacy acquisition. Such systems have been increasingly exploited in the field of language acquisition and, more recently, also in the specific domain of literacy acquisition. Their applications appear to be promising (Malessa, forthcoming), both in terms of learners’ engagement and in terms of the opportunities they offer to users to learn at their own pace. Experimental data about the efficacy of such methods will likely provide further knowledge to support literacy acquisition and inform curriculum design for working with LESLLA learners.

5. Conclusions