1. Introduction

To date, most efforts at classifying Arabic dialects have been concerned with grouping dialects on the basis of shared forms. At times, these forms have been phonological, such as the reflexes of *

q that inform the well-known sedentary–bedouin division; at others, they have been morphological, such as the

1sg imperfective prefix

n- that differentiates western from eastern varieties (see

Palva 2006 on these, among others). In this paper I put forth an alternate proposal: that it may be beneficial to look past forms themselves, and add to our toolset the use of semantic typology as a metric for grouping and subgrouping dialects. In doing so, the possibility arises that formally dissimilar features in two or more varieties may actually have more in common than previously thought, at least to the extent that the features in question exhibit the same types of polysemy. This approach is not exclusive of existing classification schemes. Instead, it may be seen as a way to further test and refine previous characterizations, or otherwise break a tie when a classification decision is questionable.

Although the typological approach itself can theoretically be applied to any number of interrelated feature sets, I opt to focus here on the interplay between nominal morphosyntax and a set of semantic notions that I refer to with the umbrella term ‘definiteness’. The choice to use the term holistically follows that of other works, including

Lyons (

1999), similarly titled

Definiteness, and presumes

Chafe’s (

1976, p. 39) definition of the same as “whether I think you already know and can identify the particular referent I have in mind”. Nonetheless, to be clear, in speaking of ‘definiteness systems’, my focus is on a particular range of definite-indefinite meanings, including relevant subcategories, that can accompany common nouns in response to Chafe’s question (whether or not the answer is affirmative). Definiteness is a useful feature set with which to test a typological classification approach for various reasons, among them that (1) it can be modeled with a reasonable degree of precision, (2) Arabic dialects are known to differ in the ways they express it, and (3) sufficient material exists such as to be able to model discrete dialects and compare them, at least on a preliminary basis.

Most discussion of definiteness in the Arabic dialectological literature is, as is often true of other features, primarily concerned with formal representations. These discussions can be subdivided into two primary types, the first being the shape and assimilation patterns of the so-called “definite article” *

al-1, and the second being the presence and shape of “indefinite articles” in dialects that exhibit them. In the case of the former, the article *

al- typically receives little explicit semantic discussion, as it is usually presumed to indicate true definiteness. Indefinite articles have fared somewhat better, perhaps because they clearly depart from formal expectations imparted by the standard language, and differ within dialects themselves;

Mion (

2009) provides an excellent survey of these articles, and even provides a preliminary (form-focused) typology, though his paper stops short of placing them into a comparative semantic framework.

The organization of the present paper is as follows: I begin with a theoretical discussion of definiteness and models that can be used to envision it, especially as they apply to the Arabic case. Following that, and in keeping with the overall focus on meaning over form, I provide a tier-by-tier view of the primary semantic categories attested in the above models, providing evidence of variation in Arabic by drawing on material from the dialectological literature. The next section provides more complete models of a sample of discrete Arabic dialects, selected again to exhibit the extent of possible variation, and to allow for side-by-side comparison. Finally, I return to questions of dialect classification, including both how we can construct schemes from the present data and how these schemes might interact with classification proposals previously made.

Because linguistic examples are drawn from various sources, many of which exhibit different conventions, I have adapted them (with the exception of Nubi) into a single transcription system and provided my own interlinear glosses and free translations.

2 In addition, throughout this paper I follow

Dryer (

2014, p. e234) in adopting an intentionally broad and more semantically oriented definition of the term ‘article,’ which is used interchangeably with ‘marker’ to refer to any morphosyntactic structure that adds referential meaning to a noun. As such, its use here should not be understood as a syntactic judgment of any particular form.

2. Modeling Definiteness

As a starting principle, definiteness (in the holistic sense) is presumed here to be a semantic property of nouns in all human languages, stemming from shared cognitive perceptions of the world, entities within it, and other humans’ knowledge of them. This semantic view is distinct from the grammatical expression of definiteness, which may be realized differently (or not at all) on a language-by-language basis.

Dryer’s (

2005a,

2005b) respective overviews of definite and indefinite articles for the

World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS) underscore this point, showing that common cross-linguistic definiteness systems include formal representation of (1) both definiteness and indefiniteness, (2) definiteness but not indefiniteness, (3) indefiniteness but not definiteness, and (4) neither definiteness nor indefiniteness. Despite the variability of possible arrangements, maps of the same data show that they are not distributed at random, but rather display areal characteristics, often bridging disparate language families that are geographically proximate, but then varying inside a single language family that is geographically distributed. As Arabic falls into the latter category, that it sees variability in the expression of definiteness is a reasonable initial assumption.

Although grammarians often speak of “definiteness and indefiniteness” in binary terms, scholars have nonetheless recognized that definiteness and its expression cannot adequately be envisioned on a bipartite basis. In the past half-century, various models have been offered as visualizations of the cognitive statuses that underlie nominal referentiality, a common component of which has been the subdivision of either the ‘definite’ or ‘indefinite’ categories—often both—into more precise subcategories. These models have also generally recognized the same ordering of categories, which form a sort of continuum along which formal representations might be distributed. Here I briefly review some of these models and select one for the present task, then move more explicitly into the Arabic case.

2.1. The Wheel Model

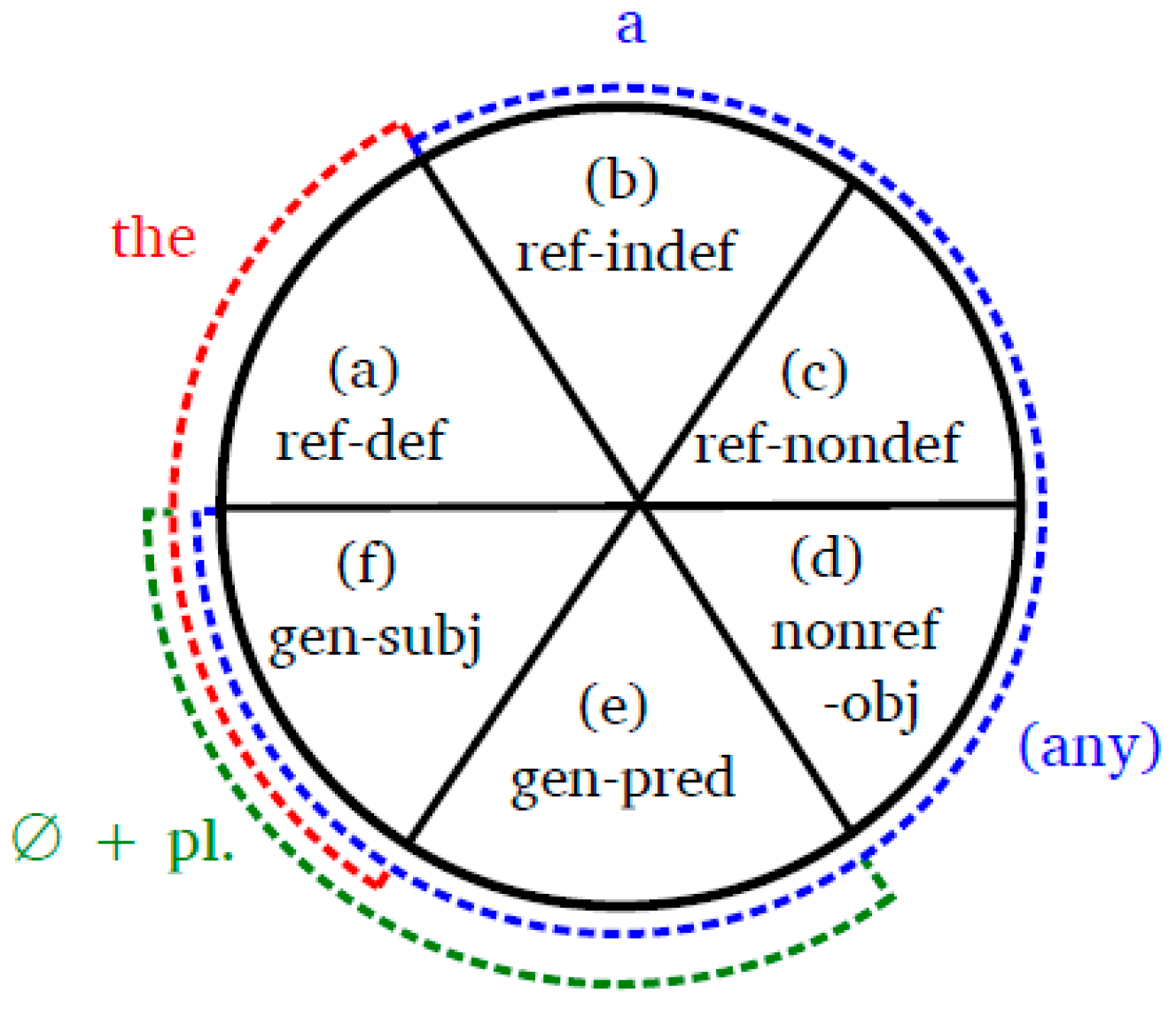

Givón (

1978, p. 298) proposes a wheel-shaped model that distinguishes six possible nominal statuses, which he identifies as (a) ‘referential definite’, (b) ‘referential indefinite’, (c) ‘referential nondefinite’, (d) ‘nonreferential object’, (e) ‘generic predicate’, and (f) ‘generic subject’, with the first and last categories bordering each other.

Figure 1 shows this model as he envisioned it for standard English. The choice of a wheel is motivated by Givón’s observation that, while languages often use a single morphosyntactic strategy (possibly including zero-marking) for two or more statuses at once, their distribution across categories is nearly always contiguous. One notes, for example, that the English ‘indefinite article’

a (or

an) can indicate multiple underlying semantic statuses. Givón’s terms are somewhat clumsy—it not immediately apparent how one would contrast ‘indefinite’ and ‘nondefinite’ without reviewing examples—but they do establish the basic principle of multiple semantic distinctions underlying a single form. He also rightly indicates that plural and singular forms do not have to follow the same patterning, and uniquely carves out space in his model for generic entities.

3 2.2. The Givenness Hierarchy

Gundel et al. (

1993) approach the same issue more broadly, framing definiteness as a subcomponent of a larger set of meanings, including those indicated by personal and demonstrative pronouns, that they refer to as ‘givenness’. They propose a ‘Givenness Hierarchy’ (

Table 1) consisting of six cognitive statuses, wherein the more discursively ‘known’ or ‘given’ a referent it is, the further to the left of the hierarchy it will be. The three rightmost statuses in the Givenness Hierarchy might be seen as corresponding with the four statuses (a)–(d) of Givón’s Wheel Model, showing a discrepancy in the choice of subdivision despite a general agreement that subdivisions should exist. One contribution of Gundel, Hedberg, and Zacharski is that they provide a formal representation of one of the ‘indefinite’ subcategories by giving informal English

this as an indefinite article, a use that is further confirmed in

Ionin (

2006), who calls it a ‘specific’ marker. As it is useful to be able to provide semantically nuanced free translations, I make ample use of indefinite

this in translations of Arabic examples in this paper.

2.3. The Reference Hierarchy

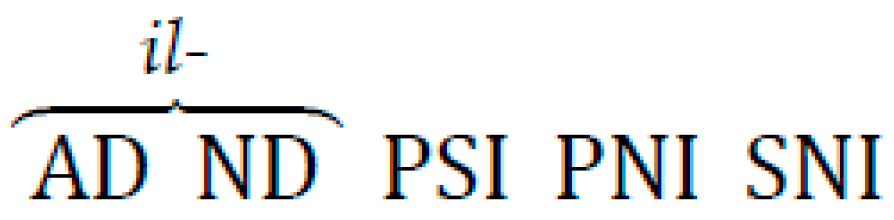

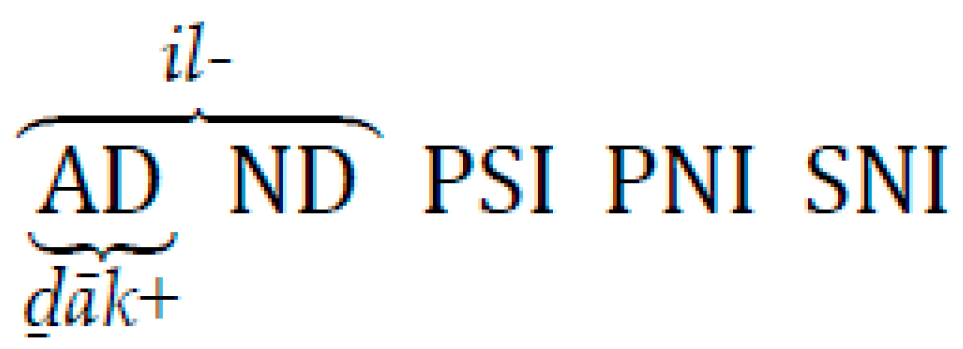

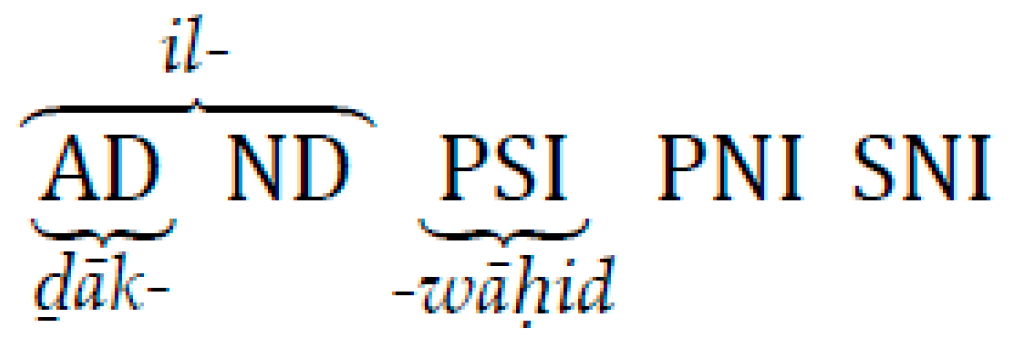

Drawing together advantages of both the Wheel Model and the Givenness Hierarchy, a more recent proposal by

Dryer (

2014, p. e235) by the name of the ‘Reference Hierarchy’ (

Table 2) combines the more limited scope and greater categorical distinctiveness of the former with the hierarchical implications of the latter. Dryer’s model enjoys the unique advantage of having been constructed on the basis of a large corpus of real-world language data, which featured in his (

Dryer 2005a,

2005b) work for the WALS database; as such, it is likely to be sufficient for the description of most languages (including Arabic). Like Givón before him, Dryer emphasizes the tendency of articles to be both polysemous and contiguous across a particular range of meanings; meanwhile, like Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski, Dryer relies on the notion of a hierarchical relationship whereby nouns that are more ‘known’ or ‘given’ are located further to the left. His choice of five categories is more akin to the Wheel Model, though he leaves out generics and splits ‘referential definites’ into ‘anaphoric definites’ and ‘nonanaphoric definites’. Also like the Wheel Model, the Reference Hierarchy proposes three non-generic indefinite statuses, i.e., one more than the Givenness Hierarchy indicates. Finally, although Dryer’s particular terminologies are lengthy, he does provide a set of 2 to 3-letter abbreviations (in heading of

Table 2), which are particularly suitable for in-line reference and interlinear glosses.

2.4. Applying the Reference Hierarchy

Because it captures the advantages of models before it, was specifically proposed as a response to cross-linguistic data, and allows for abbreviated reference to particular semantic statuses, I opt to use the Reference Hierarchy as the working model for the current paper, and hereby adopt the terms ad, nd, psi, pni, and sni for their respective meanings. These abbreviations are henceforth used liberally in both glosses and prose. It is nonetheless worth pointing out that broad terminological consensus has yet to emerge within this field of inquiry, so I summarize each status as follows, for clarity:

Anaphoric definite (ad), which is a subset of both Givón’s ‘referential definite’ and Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski’s ‘uniquely identifiable’, refers to the status of a noun that the speaker presumes identifiable to the listener because the referent has already been explicitly introduced or implied in the present discourse. In English it is obligatorily marked with the, and optionally with the demonstrative adjectives this or that.

Nonanaphoric definite (nd), which is also a subset of Givón’s ‘referential definite’ and Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski’s ‘uniquely identifiable’, refers to the status of a noun that a speaker presumes identifiable to the listener because the referent is available through shared world knowledge. In English it is obligatorily marked with the.

Pragmatically specific indefinite (

psi), which corresponds with Givón’s ‘referential indefinite’ and is a subset of Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski’s ‘referential’, refers to the status of a noun that the speaker can uniquely identify but presumes the listener cannot. It has elsewhere been called ‘specific’, and in English is obligatorily marked with

a(n), or in more informal varieties with

this (

Ionin 2006).

Pragmatically nonspecific (but semantically specific) indefinite (

pni), which corresponds with Givón’s ‘referential nondefinite’ and is a subset of Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski’s ‘referential’, refers to the status of a noun that neither the speaker nor listener can uniquely identify, but which the speaker conceptualizes as being distinct from others of its type. It has elsewhere been called ‘existential’, and in English is obligatorily marked with

(a)n, but can also be marked with

some (

Israel 1999).

Semantically nonspecific indefinite (sni), which corresponds with Givón’s ‘nonreferential object’ and Gundel, Hedberg, & Zacharski’s ‘type identifiable’, refers to the status of a noun that is fully unindividuated and is interchangeable with any other of its type. In English it is obligatorily and exclusively marked with a(n).

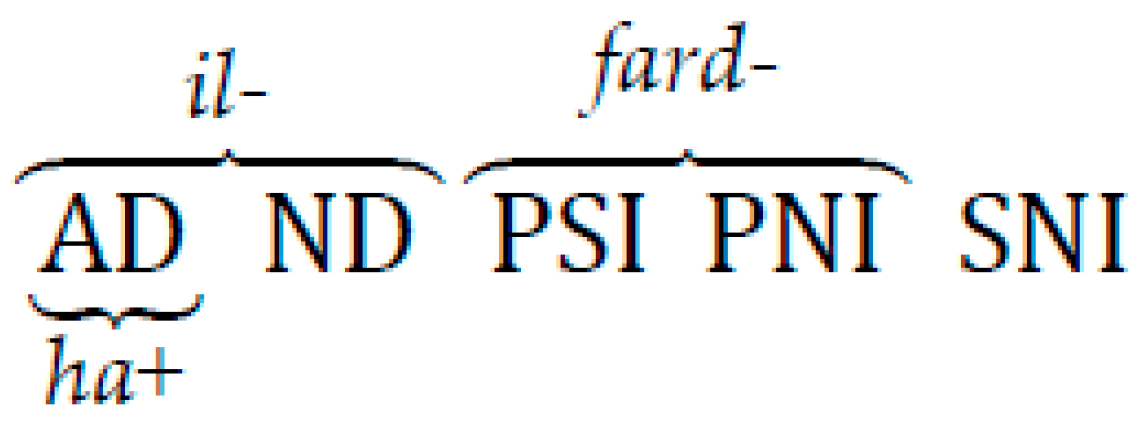

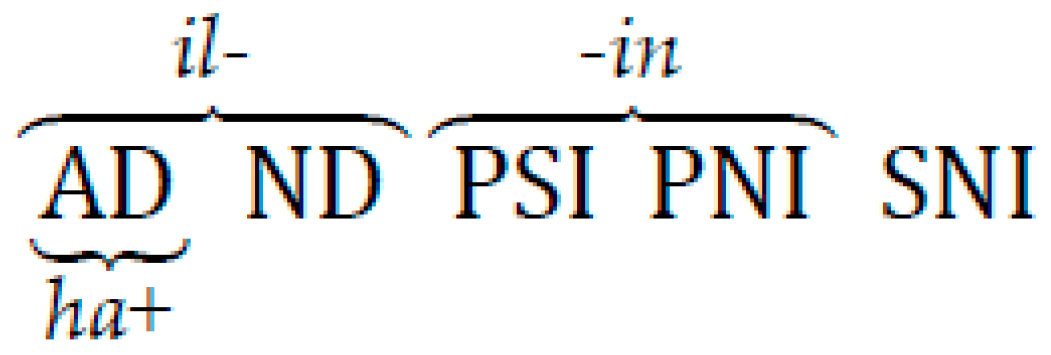

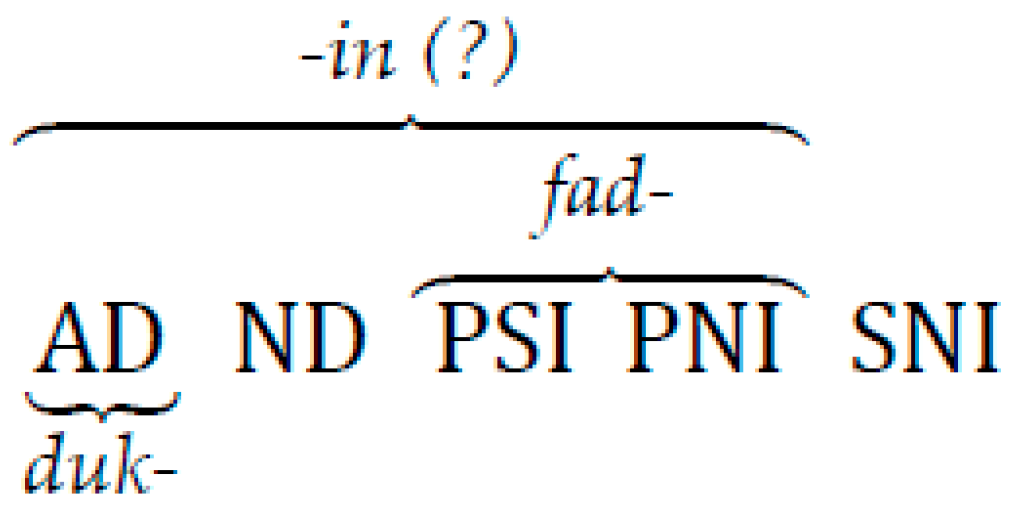

Using the above definitions, it is possible to build a visual representation of a given language’s definiteness system by representing the Reference Hierarchy as a series of blocks along which corresponding forms can be mapped.

Figure 2 gives my interpretation of the system in spoken American English. The articles represented at top,

the and

a(n), are obligatory; meanwhile, the forms at bottom represent auxiliary strategies. This strategy is maintained for other iterations of the model in this paper. The visual model has the added benefit of easing comparison between multiple systems, as is our purpose here, and explored further in

Section 4.

2.5. Definiteness in Arabic

A handful of works to date have treated definiteness (or aspects of it) in Arabic specifically. Of these,

Brustad (

2000, pp. 18–43) is the most immediately relevant in both its focus on spoken Arabic and its comparative approach. She introduces the idea of a ‘definiteness continuum’ that includes not only meanings that are “wholly definite” or “wholly indefinite”, but also exist within an intermediate range that she terms ‘indefinite-specific’. Within the current framework, “wholly” definite and indefinite correspond with the statuses

ad/nd and

sni, respectively; meanwhile, the indefinite-specific range that Brustad speaks of seems to cover both

psi and

pni. Looking at Moroccan, Egyptian, Syrian, and Kuwaiti dialects, Brustad identifies common patterns, among them the marking of true definites (

ad/nd) with a reflex of *

al-, as well as the zero-marking of non-referential (

sni) nouns. Taken alone as a binary opposition, this initial observation corresponds with the way definiteness in Arabic is often framed.

At the same time, Brustad also establishes the presence of structures that add more nuance than the binary model allows, many of which vary by dialect. Within the indefinite-specific range, she documents use of reflexes of *

wāḥid ‘one’ for all four dialects, observing that it often marks a new topic that is subsequently adopted in the discourse. I qualify such referents as inherently

psi, in that new topics are necessarily known to the speaker—who can therefore expound upon them—but are presumed inaccessible to the listener. Nonetheless, as Brustad notes that *

wāḥid is often restricted to humans (e.g.,

wāḥid badwi ‘a certain bedouin’, p. 20), I am more inclined to read it in such cases as an indefinite pronoun modified by an adjective (i.e.,

someone (who is a) bedouin) rather than a truly inclusive article that can modify any common noun. The exception is in Moroccan, which I discuss more specifically in

Section 3.3.

For Moroccan and Syrian varieties, Brustad locates an article

ši, which she glosses as ‘some (kind of)’ and contends speakers use “to indicate that they have a particular type of entity in mind”. Brustad also raises the possibility of interpreting dialectical

tanwīn as a sort of indefinite-specific marker, citing

Ingham’s (

1994, pp. 47–50) comments on its semantic qualities in Najdi Arabic, and shows how both partitive structures and demonstrative adverbs can have the same semantic effect in Egyptian (

Brustad 2000, pp. 30–31). Under the broad definition of ‘article’ used here—which, again, privileges semantic function over syntactic analysis—I consider such structures part of a given dialect’s article system, and specifically include them in below models.

Elsewhere, Brustad complexifies uses of the article *

al-, typically seen to be a marker of true definiteness. Two principal qualifications arise from her data. The first of these is that while true definite (

ad and

nd) nouns are consistently represented with *

al-, anaphoric definites are often further marked with an unstressed demonstrative adjective (

hād-,

ha-, etc.) as a means of increasing their discursive prominence (112–139). I see this common strategy as akin to other auxiliary strategies for marking particular referential meanings, and thus class these as a type of

ad marker. The second qualification involves the presence of *

al- in apparently indefinite contexts, which Brustad identifies as a common occurrence in Moroccan (e.g.,

xəṣṣ-

ni l-wəld ‘I need a son’; p. 36). I interpret this as evidence that the Moroccan reflex of *

al- is distributed over a wider range of referential statuses in general (see

Section 4.9).

There are few other holistic studies of definiteness in spoken Arabic.

Turner (

2018) is comparative and concerned exclusively with spoken Arabic, and employs the same descriptive model as the current paper to explore variability in spoken Arabic; the reader is encouraged to refer to it for additional data presented within the Reference Hierarchy framework.

Fassi Fehri (

2012, pp. 205–31) provides a more traditional syntactic view of determination in Arabic and Semitic at large, and includes some spoken Arabic data. Remaining studies that have relevance for the study of definiteness in Arabic can be divided into two types. The first are those that focus on single varieties, such as

Caubet’s (

1983),

Belyayeva’s (

1997), and

Fabri’s (

2001) focused and theoretically nuanced descriptions of definiteness in Moroccan Arabic, Palestinian Arabic and Maltese, respectively. The second type of relevant studies are those that examine a single form through a multifunctional semantic lens, and include in turn accounts of its articular functions; among these,

Wilmsen’s (

2014) expansive account of

ši across Arabic varieties and

Leitner and Procházka’s (

forthcoming) examination of

fard in the dialects of Iraq and Khuzestan stand out.

5. Definiteness and Classification

In theory, if the definiteness systems of Arabic dialects can be modeled, they should be relatively easy to classify. In practice, various complications arise that mean any attempt at classification will necessarily be subject to caveats and in need of ongoing refinement. As indicated more than once above, some of the systems themselves need more focused study to confirm how fully applicable the provisional models I have provided are to the dialect group as a whole. Scholars of Levantine Arabic, for example, face an open question as to just how close the unstressed anaphoric demonstrative complex hal- has come to acting as an obligatory article; similarly, scholars of Moroccan and Iraqi dialects may be able to further quantify uses of their respective indefinite articles in the same way by looking at them through a primarily semantic lens.

A related question is the concept of ‘obligatory’ vs. ‘auxiliary’, which I have attempted to frame here as a sort of continuum, the intermediate range of which might be described as ‘conventionalized’. For the purpose of grouping and classification, it seems that obligatory articles—those that are required when a speaker wants to denote a particular referential meaning—should take priority, as they represent a sort of linguistic consensus on the part of the speaker community that is not present for other markers. Nonetheless, is not always immediately clear what ‘obligatory’ means. It seems unwise to treat it as an absolute notion that only a single contrasting token would disqualify, especially when diglossic practices allow speakers to switch between registers (and their respective definiteness systems) at will. Instead, it seems more reasonable to look at the preponderance of the evidence: what forms most often arise in everyday conversation between native speakers of the variety in question? I suggest that these highly conventionalized strategies should also be prioritized for the purposes of classification.

This is not to say, either, that less frequent auxiliary strategies have no value, else I would not have included them here. To the contrary, it does appear worthwhile to point out that a majority of Arabic varieties optionally use unstressed demonstratives for anaphoric definite meanings, and that both varieties that do not (such as Egyptian) and varieties that oblige them (such as some in the Levant) are the outliers. It does seem relevant to note that not just one, but at least two, Arabic varieties (Egyptian and Sanaani) show the same typological pattern of co-opting a demonstrative adverb as a marker of specific indefinites, even if these are not required or even all that frequently used, statistically speaking, to express that meaning. Most importantly, although these are synchronic patterns, all fully crystallized innovations were presumably in flux at one time, so for the historical record alone it is worth noting that such strategies exist.

With these qualifications in mind, then, we can approach the question of classification more directly. I propose that there are two primary methodologies for grouping dialects when looking at a set of interrelated semantic features, as is the case with definiteness. The first is a ‘single-tier’ approach, meaning we simply limit our view to a particular type of meaning within the Reference Hierarchy, survey the forms that are attested for it, and order them into groups. This approach is not particularly distinctive from the survey I provided in

Section 3, and can be useful as a starting point for hypotheses, especially because it is suitable for identifying outliers. The Central Asian group, for example, clearly stands out in that it does

not obligatorily mark definite (

ad/nd) nouns (see

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2), and Moroccan clearly stands out in that it

can mark full indefinite (

sni) nouns (see

Section 3.5). Nonetheless, while this approach might be initially useful for looking beyond forms and toward semantic function—e.g., for noting that

ši and

*fard have at least partial semantic overlap—it is not particularly useful for comparing systems as whole.

Instead, I offer that a preferable approach is to look at the distribution of forms holistically, in what might be called a ‘multi-tier’ approach. It is still necessary, of course, that we prioritize some features over others as a means of subgrouping, but as a general principle I hold that each primary subgroup should be selected to describe as many varieties as possible while whittling away the outliers. One possible schema, based on the comparative systems given in

Section 4 (minus Nubi), and taking into account the above points about obligatory and conventionalized forms, as is follows:

There are admittedly other ways in which this same set of metrics could be ordered, and the varieties in question consequently be grouped, but this one has a few advantages. The first is that the present classification does give some credence to traditionalist views of Arabic as having a normative system where *al- is a “definite article,” while leaving room for exceptions and, at the same time, expanding the profile of what a “normative” dialect is by showing that a majority of these do have at least some means of marking indefinite referents, a pattern that stretches from the Atlantic to the Gulf. A second advantage is that the classification serves to group together varieties that might not necessarily share features, but which do share basic semantic patterns, in turn opening the door for diachronic questions, especially when these varieties are geographically distant from each other. I do not mean to imply by this a hereunto undiscovered genetic relationship between Moroccan and Central Asian varieties, but I do mean to point out that both groups have seen the strict categorical distinction between definites and indefinites unravel, and they are both at the far ends of the Arabic-speaking world.

Interpreted this way, the definiteness data align most closely with a ‘core-periphery’ classification model, in that a strict formal distinction between definites and indefinites is maintained across a large, contiguous cultural area and frays only at its edges. Within the core area, there is frequent variation in the particular means of marking referential indefiniteness, and somewhat of a northern–southern split as one moves from unmarked or optional marking strategies of Egypt, Yemen, and the Gulf to the more conventionalized strategies of the Levant and Mesopotamia, but the strict and exclusive association of

*al- with definiteness goes unchallenged. Meanwhile, on the geographic fringes of this core, dialects break away typologically by either (1) extending

*al- to indefinite meanings or (2) detaching it from definite meanings.

11 The concept of peripheral dialects has been explored in volumes such as

Owens (

2000) and

Anghelescu and Grigore (

2007), and even though such varieties are just as often defined by what they are not than what they have in common, the addition of definiteness as a metric does at least support the idea of the ‘core’ against which they are defined as a viable linguistic entity.

Other classification proposals do not align as well with a scheme based on definiteness systems. The oft-proposed east–west division of dialects (see

Palva 2006) is not easily evident here, especially given that the minimal expression of indefiniteness in Hassaniya varieties fall into the same general pattern as dialects much further east, including those of Egypt, Yemen, and Kuwait. The bedouin–sedentary division (again see Palva) is tenable only on the basis of the

tanwīn feature, which is largely limited to bedouin-type varieties and is unique among indefinite markers in that it is conditioned by syntactic factors in addition to semantic ones. Nonetheless, in a purely typological sense, the presence of a conventionalized indefinite marker actually places DT-expressive bedouin varieties such as Najdi closer to the indefinite-marking sedentary dialects of the Levant and Mesopotamia than it does to other bedouin varieties that lack it, such as western Hassaniya or Kuwaiti. Finally, one may consider whether, within the sedentary dialects, an urban-rural division is relevant; this too seems unlikely, given the systems found in a given geographic region

do tend to be contiguous across urban and rural areas. The Levantine

pni article

ši, for example, is used by speakers both in Beirut and small mountain villages in the same way that the Moroccan

psi article

wāḥəd is found both in the old cities and rural countryside.

In summary, the system-level configuration of definiteness marking does ultimately seem to be an areal pattern, and even minor differences between systems might consequently be useful for further subdividing clusters of geographically adjacent dialects. This possibility has already been raised for eastern vs. western Hassaniya (

Section 4.4), as well as Levantine (

Section 4.6) varieties. I also offer the observation that somewhere between central Algeria and Tunisia, dialects see an abrupt shift from complex, Moroccan-like systems (

Section 4.9) to simplex, Libyan-like systems (

Section 4.1). Precisely where these lines may lie—and why—is a question for future studies to address. Many of the systems in question seem to be the product of innovation, whether via semantic extension or leveling, and whether prompted by contact or otherwise. As it seems reasonable to expect that groups that innovate together, along the same timeline and to the exclusion of nearby groups, are indeed more likely to share history and social ties, further studies on definiteness and referentiality in spoken Arabic will be of value to the larger project of dialect classification.