Abstract

Spoken languages make up only one aspect of the communicative landscape of Indigenous Australia—sign languages are also an important part of their rich and diverse language ecologies. Australian Indigenous sign languages are predominantly used by hearing people as a replacement for speech in certain cultural contexts. Deaf or hard-of-hearing people are also known to make use of these sign languages. In some circumstances, sign may be used alongside speech, and in others it may replace speech altogether. Alternate sign languages such as those found in Australia occupy a particular place in the diversity of the world’s sign languages. However, the focus of research on sign language phonology has almost exclusively been on sign languages used in deaf communities. This paper takes steps towards deepening understandings of signed language phonology by examining the articulatory features of handshape and body locations in the signing practices of three communities in Central and Northern Australia. We demonstrate that, while Australian Indigenous sign languages have some typologically unusual features, they exhibit the same ‘fundamental’ structural characteristics as other sign languages.

1. Introduction

Australian Indigenous sign languages are predominantly used by hearing people as a replacement for speech in certain cultural contexts when speech is either impractical or inappropriate. They have been referred to as ‘alternate’ sign languages by Kendon ([1988] 2013) and, like other sign languages that have similar cultural functions, their ‘alternate’ status brings with it some differences when compared to deaf community signed languages which are used as a primary means of communication.

Sign languages are known to exhibit a wide range of articulatory contrasts and distinctions that are distributed in an “organized” and “principled” fashion (Brentari 2019). These criteria are said to distinguish sign from gesture, which in general exhibits no such rules of well-formedness. Following Stokoe’s ([1960] 2005) seminal work on ASL, a number of phonological models have been proposed to account for and describe the structure of sign languages (see Brentari 1998; Sandler 1995; van der Hulst 1993). These models rely on descriptive work which is largely absent in the Australian Indigenous context. In this paper, we extend the geographical scope of understandings of similarities and differences in the phonological features of Australian Indigenous SLs by looking at signing practices across three communities—Warlpiri (Central Australia), Kukatja (Balgo, Western Desert) and Yolngu (East Arnhem Land). In order to address the question as to whether Australian Indigenous SLs possess more than mere “kernels of a phonological system” (Sandler et al. 2011, p. 4) and to deepen understandings of the articulatory principles that define their sign forms, we compare:

- Handshape

- Handedness, symmetry and dominance

- Body-anchored signs

- The size of the signing space

We first provide a brief introduction to Australian Indigenous SLs (Section 1.1), introduce the three regions included in this study (Section 1.2), and summarise previous research on Australian Indigenous SLs (Section 1.3). In Section 2, we unpack some of the theoretical considerations that underpin research on SL phonology, including features of deaf community SLs which have been taken as universal metrics—symmetry and dominance conditions and criteria for unmarked handshapes (Battison 1978). We then outline our methods, including coding decisions for handling polysemy, compound signs, and handshape variation (Section 3.1), annotation in Elan (Section 3.2) and the process of isolating minimal pairs and the phoneme inventories of each SL (Section 3.3). In Section 4.1, we outline the handshape inventories of the three SLs in our study and discuss these findings in relation to frequency and markedness (Section 4.2), and symmetry, handedness and dominance (Section 4.3). Through this we show that Australian Indigenous SLs adhere to the proposed ‘universal’ metrics of sign phonology. In Section 4.4, we summarise our findings about places of articulation on the body and how a proliferation of body locations results in a large signing space for Australian Indigenous SLs. In Section 5, we discuss what the similarities and differences between Australian Indigenous SLs and deaf community SLs can tell us about sign structure. Namely, what aspects of sign phonology can we expect to be found in all sign languages, and what features may be variable, without assuming a ‘developing’ or absent phonology? Appendix A presents the frequencies of contrastive handshapes found in Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu sign.

1.1. Background to Australian Indigenous Sign Languages

Alternate SLs have been documented in various world contexts, and they are used either when silence is required or speaking is impractical: in monastic orders, in noisy workplace environments, or when hunting (Hindley 2014; Mohr 2015). Sign may also serve as a lingua franca when there are many spoken languages, for example the use of Plains Indian Sign Language by Native Americans (Davis 2015; Davis and McKay-Cody 2010). Such alternate SLs are most often developed in hearing communities and they vary in their functions and degree of complexity (Pfau 2012, pp. 528–51). In Indigenous Australia, sign is used for particular cultural and pragmatic reasons. People sign in certain types of gender-restricted ceremonies and in other situations where speaking is inappropriate or disallowed. Sign is used when hunting as a “silent form of coordination” so as to not scare off game (Montredon and Ellis 2014, pp. 11–12); when giving directions; and for communication between interlocutors who are visible to each other yet out of earshot. Using sign enables the circumspection required of certain topics, and sign is one of the resources drawn upon to mark kin-based respect (Green 2019). In some Australian Indigenous communities, sign was the main form of communication used by particular kin in the context of bereavement where sign was used instead of speech during extended periods of mourning. Indigenous SLs appear to have been most developed in regions, such as Central Australia and Western Cape York, where speech taboos extended through such periods of bereavement (Kendon [1988] 2013). In some circumstances, sign may be used alongside speech, and in others it may replace speech altogether. Some Indigenous deaf are also known to make use of these languages as their main form of communication and they may well be seen as primary signers of Australian Indigenous SLs (Bauer 2014). However, the ways that Australian Indigenous SLs, deaf community SLs such as Auslan, and shared gestural practices may interact in Australian contexts awaits further research. The Warlpiri and Kukatja data in our study are from hearing signers, while the Yolngu corpus includes data both from hearing signers and from two deaf Yolngu signers (see also Bauer 2014).

1.2. Some Socio-Linguistic Background to Three Communities under Study

1.2.1. Warlpiri

Warlpiri is a Pama-Nyungan language spoken in Central Australia in a region to the north-west of Alice Springs in communities including Lajamanu, Yuendumu, Willowra, Nyirrpi, Mt Allan and Ti Tree (see Figure 1). The term rdakardaka (lit. ‘hand hand’) is used to refer to the signing practice. Between 1978 and 1986, Adam Kendon worked with Warlpiri signers in the community of Yuendumu to make a record of the sign language used there (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 94). Warlpiri sign is recognised as perhaps one of the most ‘developed’ of the SLs of Australia and this may be due to its extensive use during periods of mourning, especially by widows. Kendon states that there are “about 1500 Warlpiri signs” (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 95). Further research is needed to investigate the extent to which there are lexical differences in signing practices across the different Warlpiri communities. Some examples of Warlpiri sign (as used at Ti Tree) can be found in the online sign language dictionary iltyem-iltyem (see Carew and Green 2015).1

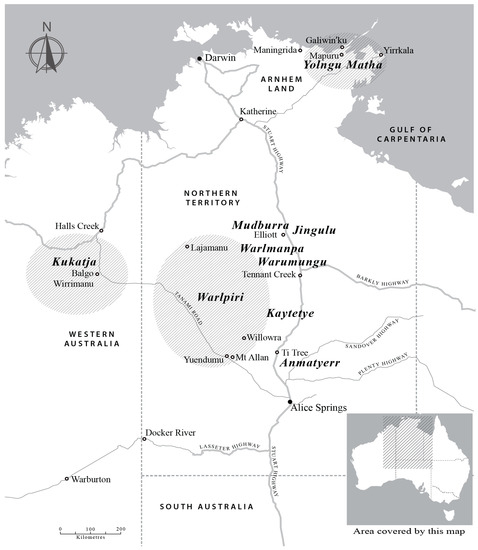

Figure 1.

Map of research locations (Map: Jennifer Green).2

1.2.2. Kukatja

Balgo, also called Wirrimanu, falls within the Western Desert (see Figure 1), a geographical area and cultural bloc that stretches from Kalgoorlie, Western Australia in the south-west to Woomera, South Australia in the south-east, and from Jigalong, Western Australia in the north-west to Hall’s Creek in the north-east (Berndt 1959; Tonkinson 1978). A former mission town, the original mission ‘Old Balgo’ was established in 1943 by German Pallottine missionaries and was situated around 30 km to the west of Balgo’s current location. Many spoken languages are used in Balgo, including Jaru, Walmajarri, Warlpiri, Ngardi, as well as the Western Desert languages Kukatja, Pitjantjatjara, Pintupi and Wangkatjunga. Aboriginal English and Kriol are also spoken by many. The sign language used in Balgo—‘Kukatja sign’3 —is also referred to as marumpu wangka ‘hand talk’ or ‘finger talk’. Our data for Kukatja sign come from six hours of elicitation sessions recorded at Balgo by anthropologist William Lempert in 2015 (see Jorgensen 2020). Signing is an everyday practice for most people in Balgo and use of sign is not only a way of communicating information but serves as “full-bodied ways of expressing the nuance, humour, and individuality embedded within everyday Aboriginal community life” (Lempert 2018, p. 255). Examples of Kukatja sign are available on YouTube through ABC Indigenous.4

1.2.3. Yolngu

The term Yolngu refers to a sociocultural unit and the language varieties spoken in North East Arnhem Land. Arnhem Land stretches from east and southeast of Darwin across to the western coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria. The Yolngu region starts from east of the Blyth River and covers almost 40,000 square kilometres. The languages spoken in this region are collectively referred to as Yolngu Matha and belong to the Pama-Nyungan family group. The sign practices observed throughout the Yolngu territory are locally referred to as goŋu djäma (lit. goŋ—‘hand’; djäma—‘work’) or by the English word actions. Our Yolngu data were collected during two periods of fieldwork conducted in 2009–2010 in three locations: the city of Darwin, Mäpuru homeland and in Galiwin’ku on Elcho Island (Bauer 2014). Through a recent and preliminary comparison of sign use in Maningrida, we have reason to believe there is some similarity in the signing practices in North East Arnhem Land and other communities in Arnhem Land (see Green et al. 2020).5 Further work is required to explore relatedness across the sign systems of Arnhem Land, but we may expect a high degree of continuity in these practices across these regions where there are similar ecologies and cultural practices.

Unlike signing practices found in the North Central Desert region, Yolngu signing is not associated with extensive speech taboos, when spoken language is prohibited for prolonged periods of time and SL used instead. Yolngu signing is used mainly for two purposes: (a) interaction at a distance (for example while fishing or hunting), and (b) communication with deaf and/or hard of hearing Yolngu (Bauer 2014, p. 47).

1.3. Previous Analyses of the Articulatory Features of Australian Indigenous Sign Languages

The first detailed description of articulatory features of any Australian Indigenous SL was Kendon’s work on SLs from what he termed the North Central Desert (NCD) (Kendon 1980, [1988] 2013), which includes signing communities where languages such as Warlpiri, Anmatyerr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Warlmanpa, Mudburra and Jingulu are spoken (see Figure 1). Kendon developed a notation system he termed ‘rdakardaka’ for fine-grained annotation of these SLs.6 He distinguished a total of around 130 parameters (although the count is slightly higher if some minor values and variations are included), including sign location, arm position, handshape, hand orientation, sign action, contact between articulators and modification of movements (Kendon [1988] 2013, pp. 462–73).

Jorgensen (2020) was the first to apply a recent phonological model, developed from analyses of deaf community SLs (Brentari 1998), to examine the structure of an Australian Indigenous SL, focusing on sign used in Balgo. There are partial descriptions of sign action, usually focused on handshapes, from research on signing communities in other parts of the Western Desert and in Arnhem Land (Adone and Maypilama 2014; Bauer 2014; Ellis et al. 2019; Green et al. 2018; James et al. 2020). This research has shown that sign in these communities is characterized by conventionalized form-meaning pairings, realized by contrasts along several main parameters: handshape, orientation, location and movement.

2. Theoretical Considerations

Generally speaking, phonological theory on sign stems from research on deaf community SLs. There are structural patterns in deaf community SLs which have become a metric for the existence of phonology in SLs more generally. There have been few in-depth studies of other types of SLs, such as village, alternate or shared SLs (see Mudd et al. 2020, p. 57). Exploring whether or not Australian Indigenous SLs constitute a distinct phonological ‘type’ requires us to consider the theoretical grounds on which deaf community SLs have been analysed and defined. In this paper, we apply some of the metrics usually applied to deaf community SLs to Australian Indigenous SLs to see whether they follow the same restrictions on form. Our findings have implications for claims about the universality of such metrics.

The following section summarises some relevant phonological ‘universals’ for sign structure, including symmetry, dominance, and characteristics of unmarked handshapes.

2.1. Proposed Phonological Universals for Sign Structure

Signs are commonly distinguished by one- or two-handed articulation. A signer will generally have a preferred dominant hand, and signers can be either left-hand- or right-hand-dominant without changing the meaning of a sign. The dominant hand is the active hand in two-handed signing, while the other hand is the passive or non-dominant hand. In two-handed signing, the non-dominant hand shares the same selected fingers, joint, and movement specifications as the dominant hand, or else acts as its place of articulation.

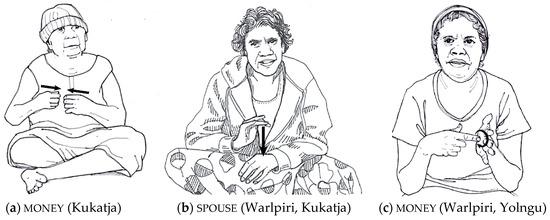

It has been proposed that, language-internally, not all combinations of phonological features are possible when both articulators are active. The forms of two-handed signs have been shown to be restricted on the basis of symmetry and dominance in ASL (Battison 1978; Napoli and Wu 2003). Two-handed signs are seen as more articulatorily complex than one-handed signs because they involve more parts to coordinate, but this complexity varies based on how redundant the non-dominant hand is, and how the informational content is distributed between the two articulators. Many phonological models represent two-handed signs with a feature such as [two-handed] specified somewhere in the structure (Brentari 1998; van der Hulst 1993). This produces a dependant non-dominant hand branch of structure from the articulator node. As first proposed by Battison (1978), in two-handed signing, we see three types of relationships between the dominant and non-dominant hand. In type 1 signs (Figure 2a), both the handshape and the movement pattern of the hands are the same. These are the most redundant and thus least complex type of two-handed sign. As the non-dominant hand is essentially mimicking the dominant hand, this can be formulated as the non-dominant hand branch sharing the features of the dominant hand. In type 2 signs (Figure 2b), the two hands have the same handshape, but the dominant hand moves, while the non-dominant hand acts as its place of articulation. In type 3 (Figure 2c) signs, the hands have different handshapes and the dominant hand acts on the non-dominant hand. For these signs, the non-dominant hand can be conceptualised as both a place of articulation and as having its own branch with specifications such as selected fingers and finger configuration.

Figure 2.

Examples of type 1, type 2, and type 3 two-handed signs (a) money (Kukatja); (b) spouse (Warlpiri, Kukatja); (c) money (Warlpiri) (Illustrations: Jennifer Taylor).

Across these categories, the degree of complexity is linked to departures from symmetry, with the most complex forms (complete lack of symmetry) prohibited. Battison (1978, pp. 33–34) posited two constraints that govern what combinations of phonological features can be co-articulated in two-handed signs:

The Symmetry Condition

- If both hands of a sign move independently during its articulation, then both hands must be specified for the same location, the same handshape, and the same movement (whether performed simultaneously or alternatingly).

The Dominance Condition

- If the hands of a two-handed sign do not share the same specification for handshape (i.e., they are different), then one hand must be passive while the active hand articulates the movement, and the specification of the passive handshape is restricted.

In addition to restrictions on handshape in two-handed signing, previous work on both deaf community (Ann 2006; Battison 1978; Braem 1990) and Australian Indigenous SL phonology (Kendon [1988] 2013, pp. 127–35) suggests that some handshapes are more marked than others. Relative markedness has long been associated with relative complexity in their phonological representation (Brentari 1998; Sandler 1995; van der Hulst 1993), so we may expect that handshapes with minimal specifications will be the unmarked set. The dominance condition is also a diagnostic for finding a set of unmarked handshapes in any given SL. Battison (1978) argues that unmarked forms follow certain characteristics:

- Of the total set of handshapes, they are the most frequently occurring

- They are used by the non-dominant hand in non-symmetrical two-handed signs (dominance condition)

- They are universal (found in all SLs)

- They are acquired first by children

- They are maximally distinctive, i.e., the most contrastive forms possible

- They are easiest to articulate

In Section 4.3, we apply the frequency, dominance and universality criteria to our datasets. There is no research to date on how Australian Indigenous SLs are acquired by children, nor any quantitative analysis of ease of articulation or distinctiveness of their handshape inventories, so these additional criteria must be put aside for now. These topics are potential avenues for future research.

3. Methods

The data that form the basis of our analysis were collected between 2010 and 2019 as part of several research projects aimed at documenting Australian Indigenous SLs and verbal arts in various regions of Australia. The analysis of Warlpiri sign features is based on Kendon’s documentations of Warlpiri sign.7 We revisited Kendon’s original fine-tuned annotations (where he employed the rdakardaka notation) but applied slightly different principles in order to arrive at a dataset on which our frequency counts of features are based.

3.1. Coding Decisions

Describing sign phonology is a unique challenge, complicated by the lack of a standard phonetic notation system such as the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) used for spoken languages (Nyst 2015).8 Due to the many different approaches to SL phonology (see Brentari 1998; Liddell and Johnson 1989; Sandler 2012; van der Hulst 1993), no consensus has been reached on how to analyse and represent the structure of a given SL, and as such there is variation as to the criteria used for the inclusion of sign forms in data sets for phonological analyses.

For the purpose of making comparisons between datasets discussed in this paper, we needed to reach consensus about how to construct the sign type sets (see Section 4 below). In some cases, this meant re-coding previous material. There are a number of theoretical and practical considerations for making sign counts: how to handle polysemous signs and compound signs, whether to include two-handed signs when the dominant hand is acting on the non-dominant hand, and how to deal with the high degree of variation in sign production that we observed in our data. Although it is hard to find accounts where the underlying assumptions are laid bare, in her analyses of Kenyan Sign Language (KSL), Morgan (2017, pp. 52–53) states that the basic criteria for a sign to be ‘eligible’ include:

- The sign is not a compound or fingerspelled word9

- The sign is not a morphological variation of another sign in the database

- The sign is not a phonetic variation of another sign in the database

- The sign may be a lexical or phonological variant of another sign in the database

In the following sections, we outline the principles that we adopted in order to create sign type sets for comparative analysis across the three regions.

3.1.1. Polysemy

The first principle we applied across all datasets is that polysemous signs are only counted once for the purposes of phonological analyses. This delineates the set of distinct sign forms from the set of lexical meanings conveyed by those forms. In Australian Indigenous SLs, many signs have multiple meanings—the mapping of sign to speech does not present a one-to-one correspondence. For example, at a rough estimate, around 17% of the set of Warlpiri tokens are polysemous. All of these have distinct terms in spoken Warlpiri (that essentially correspond to a single sign).10 Polysemies may be based on shared visual attributes, on structural aspects of social organization: Yolngu momu-father’s mother11 and nathi-mother’s father, or on associations based on patterns of interaction: Kukatja pray, church and priest. For some signs, the motivation or cultural logic that drives the polysemy may not be obvious and thus opaque to outsiders: Warlpiri kuturu-nulla-nulla; juka-sugar; and ngarlkirdi-witchetty grub. In our data, polysemous signs are given the same sign ID-gloss with all of their possible meanings listed. Hence, polysemous signs are counted as a single sign type (see Table 1 below) regardless of possible motivations for the polysemy.

3.1.2. Compounds

Dealing with compounds, where two (or more) signs are combined to form a new sign with a new meaning, is more problematic. While Kukatja sign and Yolngu sign seem to have relatively few compound signs, in the Warlpiri data around 30% of signs are compounds and there are around 20 forms that occur repetitively. Some examples include give-yinyi, which occurs in compounds ‘distribute’ and ‘give out of pity’, talk-wangkami, which occurs productively in compounds with meanings such as ‘whirr, howl (of wind)’, ‘use sign language’, ‘tell stories’ and pakarni-hit/break which is found in compounds with meanings such as ‘hit’, ‘break’, ‘split’ and ‘kill’.

In calculating the frequency of various features, including handshape, for Warlpiri and other NCD SLs Kendon focused on what he called ‘simple signs’, with all compound signs excluded as well as asymmetrical two-handed forms and signs with a change in handshape (Kendon [1988] 2013, pp. 112, 126, 128).12 While both Kendon and Morgan explicitly exclude compound signs from their analyses of handshape and other articulatory parameters, we applied the following criteria:

- Where both parts of a compound are already included as ‘simple signs’, we exclude the compound.

- The ‘productive’ parts of compound signs are only counted once.

- Compounds whose parts are otherwise not attested (in whole or part) are included.

3.1.3. Variation

A further issue to be considered was the presence of lexical variants, specifically phonological variation in the handshape parameter, both across an individual’s utterances and across the utterances of multiple consultants from one language group. Earlier studies have focused on sociolinguistic variation in the location parameter in ASL (Lucas et al. 2001, 2002) and in Auslan and NZSL (Schembri et al. 2009), but we are not familiar with any reports of similar variation in handshape in any sign language. At the level of phonological representation, deaf community SLs are taken to be highly codified. While their production may be variable, their underlying form is understood to be consistent. However, Johnston (2012, p. 171) calculates that approximately 30% of Auslan signs and 18% of ASL signs are ‘partially lexicalised’. Recent studies of macro- and micro-social variation in SLs of the Asia-Pacific region add to the impetus to consider variation and the methodologies best fitted to studying it (see Palfreyman 2020, and volume). One claim is that lexical variation is more prevalent in shared SLs than in deaf SLs, and that it is the relatively smaller size of some linguistic communities that allows them to tolerate more variation (Mudd et al. 2020, pp. 55–56).

As our sign IDs are delineated based on form, it was important to have a shared approach to the handshape variation we encountered in our data. We applied the following criteria:

- If there was stability in all other parameters—location, movement, etc.—then these tokens would fall under the same type and be listed under the same sign ID-gloss.

- Variants which differ in a number of parameters are taken to be different sign forms with the same meaning, and given distinct sign ID-glosses.

An example of this distinction is found in the two signs for ‘woman’ in Kukatja. woman-1 may be produced with a variety of handshapes but is consistently realised with contact on the breast. woman-2 is produced in neutral space with an  handshape, sharing no features with woman-1.

handshape, sharing no features with woman-1.

handshape, sharing no features with woman-1.

handshape, sharing no features with woman-1.A further consideration is that variation in handshape also makes it difficult to make judgements about which handshapes to include in counts. To avoid misrepresenting our data, we counted each instance a handshape is used, regardless of whether it contributes to variation in sign production. This way, handshape frequency can be looked at as a count of how many times a particular handshape is produced as a percentage of the total handshape count, regardless of the number of sign types it is produced as part of.

3.2. Annotation in Elan

Using a shared template, the data were annotated in Elan (Wittenburg et al. 2006), with dedicated Elan tiers for handshapes of the right and left hands, handedness, and sign location. We employed the numerical codes developed by Kendon for NCD handshapes (Kendon [1988] 2013, pp. 461–73) as a guide to enable comparability across the three language groups. For signs which involve a change in handshape, both the initial and final handshape were coded. We targeted our coding of sign location to signs which involved some contact with the body as part of their production. This excluded signs which were articulated on the non-dominant hand. An iterative method for feature identification was used in this case, with labels for body location developed in the process of annotation and revised to reflect distinctions or variations as they were found.

3.3. Identification of Handshapes and Body Locations

The internal structure of sign can be described in terms of the major parameters of (a) handshape, (b) place of articulation or location of the sign, (c) movement patterns of the hand, and (d) orientation of the hand in relation to its place of articulation (Battison 1978; Fenlon et al. 2017; Johnston and Schembri 2007, pp. 79–81; Stokoe [1960] 2005). Nonmanual features may also be a contrastive feature of signs (Crasborn 2006; Pfau and Quer 2010). These parameters are comprised of groups of distinctive features and may be represented using feature geometry (see Brentari 1998; Sandler 1995; van der Hulst 1993). As this is a preliminary study of the phonology of Australian Indigenous SLs, we chose to engage with these macro categories first. Brentari (1998, p. 94) notes that these ‘class nodes’ are themselves phonologically salient—they can be manipulated in language games, occur as rhyming units in poetry, are evident in sign errors, and as such “should be recognized as important units in the structure of phonological grammar”.

To determine language-specific inventories of forms, the identification of minimal pairs is a time-honoured approach that provides the basic data for phonemic analyses. That said, as Morgan points out, “In general, there is a need for greater transparency regarding minimal pairs in the sign phonology literature” (Morgan 2017, p. 88). It has been reported that in some SLs, the search for minimal pairs yields few results—for example in Al-Sayyid Bedouin Sign Language, which is a ‘young’ SL, there are no documented minimal pairs at all (Sandler et al. 2011).

For the Kukatja and Yolngu datasets, annotations were exported from Elan and then opened in Excel so that each Elan tier appeared as a separate column and each annotation was on a new row. Excel functions were then used to locate minimal pairs. Total tokens were systematically filtered to those which had the same feature realisation for all parameters but one. The features of this parameter were then compared across tokens to see if they produced a change in meaning, as evidenced by a different sign ID-gloss. At the same time, we noted which features seemed to be variants, i.e., consistently did not result in a change in meaning. With attention to handshape variation, for our minimal pair analysis, the most frequently used handshape was always taken into account. The entire set of tokens was worked through in this way, resulting in a set of minimal pairs and inventories of contrastive handshapes and body locations.

The Warlpiri data were also analysed in Excel but required a different process to achieve a count of handshapes and body locations. Rather than relying on finding minimal pairs in his raw data, we used Kendon’s ([1988] 2013) existing list of what he calls ‘emic’ handshapes.13 We used the rdakardaka notation from Kendon’s Appendix I (pp. 462–73) to determine how phonetic handshapes pattern to these emic handshapes. Using this list of handshapes, we counted every instance of a given handshape across the Warlpiri dataset. This same process was repeated for body locations.

4. Phonological Aspects of Australian Indigenous Sign Languages

In the following sections, we outline the set of contrastive handshapes and body locations used in the three sign communities to begin to tackle the question of whether Australian Indigenous SLs constitute a distinct phonological type. We first outline handshapes used in Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu sign (Section 4.1) before discussing patterns in handshape frequency and markedness (Section 4.2) and in handedness, symmetry and dominance (Section 4.3). We then explore the relationship between body-anchored signs and a large signing space in Australian Indigenous SLs (Section 4.4).

Based on the assumptions outlined in Section 3, Table 1 shows the number of sign tokens and sign types for each signing community in our study.

Table 1.

Number of sign types and tokens in Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu SLs.

Table 1.

Number of sign types and tokens in Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu SLs.

| Sign Language | Community | No. Sign Types | No. Sign Tokens | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warlpiri | Yuendumu | 1304 | 157014 | Kendon (1986–1997) |

| Kukatja | Balgo | 213 | 1031 | Jorgensen (2020) |

| Yolngu | Mäpuru, Galiwin’ku | 284 | 3439 | Bauer (2014)15 |

4.1. Handshapes

The following sections cover the handshapes used in the three sign languages. A comparative table of handshape frequencies can be found in Appendix A.

4.1.1. Warlpiri

From Table 1, it can be seen that the total number of Warlpiri tokens is 1570. Application of the principles outlined in Section 3 results in a dataset of 1304 sign types that were included in handshape and sign location counts.16 Our handshape counts and frequencies for Warlpiri sign differ slightly from Kendon ([1988] 2013) due to our inclusion of two-handed asymmetrical signs, signs which involve a change in handshape, and unique compound parts.

For the whole of the NCD, Kendon described 52 handshapes, of which 41 were deemed emic, with 11 analysed as variants (Kendon [1988] 2013, pp. 120–25). For Warlpiri sign, Kendon identified 35 handshapes in the emic set (ibid, p. 126). The basis of our count of 35 phonemic handshapes for Warlpiri differs slightly. Though ‘ ’ is listed (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128), we found no tokens of this handshape in the data. While Kendon found no ‘simple’ signs in Warlpiri which use the

’ is listed (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128), we found no tokens of this handshape in the data. While Kendon found no ‘simple’ signs in Warlpiri which use the  handshape, it is found in one compound sign. The Warlpiri data include 430 compound signs (in which there are 455 unique parts).17 These use 25 different handshapes, all but two of which also appear in monomorphemic signs. The two novel handshapes are

handshape, it is found in one compound sign. The Warlpiri data include 430 compound signs (in which there are 455 unique parts).17 These use 25 different handshapes, all but two of which also appear in monomorphemic signs. The two novel handshapes are  , used in the sign police and

, used in the sign police and  , in a productive compound part mani, the transitive marker.

, in a productive compound part mani, the transitive marker.

’ is listed (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128), we found no tokens of this handshape in the data. While Kendon found no ‘simple’ signs in Warlpiri which use the

’ is listed (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128), we found no tokens of this handshape in the data. While Kendon found no ‘simple’ signs in Warlpiri which use the  handshape, it is found in one compound sign. The Warlpiri data include 430 compound signs (in which there are 455 unique parts).17 These use 25 different handshapes, all but two of which also appear in monomorphemic signs. The two novel handshapes are

handshape, it is found in one compound sign. The Warlpiri data include 430 compound signs (in which there are 455 unique parts).17 These use 25 different handshapes, all but two of which also appear in monomorphemic signs. The two novel handshapes are  , used in the sign police and

, used in the sign police and  , in a productive compound part mani, the transitive marker.

, in a productive compound part mani, the transitive marker. The two most frequent handshapes— and

and  —account for 38% of handshape tokens, with the six most frequent handshapes representing 60%. Four handshapes—

—account for 38% of handshape tokens, with the six most frequent handshapes representing 60%. Four handshapes—

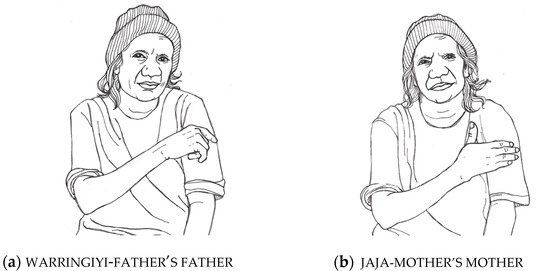

—appear in only one sign each. An example of a Warlpiri minimal pair which differs only in handshape is shown in Figure 3.

—appear in only one sign each. An example of a Warlpiri minimal pair which differs only in handshape is shown in Figure 3.

and

and  —account for 38% of handshape tokens, with the six most frequent handshapes representing 60%. Four handshapes—

—account for 38% of handshape tokens, with the six most frequent handshapes representing 60%. Four handshapes—

—appear in only one sign each. An example of a Warlpiri minimal pair which differs only in handshape is shown in Figure 3.

—appear in only one sign each. An example of a Warlpiri minimal pair which differs only in handshape is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Warlpiri minimal pair for handshape (a) warringiyi-father’s father etc (b) jaja-mother’s mother, etc. (Illustrations: Jennifer Taylor).18

4.1.2. Kukatja

The Balgo dataset includes 36 phonetic handshapes; however, evidence from 14 handshape minimal sets suggests there are 22 phonological handshapes in Kukatja sign.

As mentioned in Section 3.1.3, the search for minimal pairs was made more complicated by significant variation in handshape, with 82 signs (39%) varying in the realisation of the handshape parameter. This meant that two or more handshapes which had strong evidence of being contrastive could also seemingly be freely substituted across tokens of a single sign. This was the case for tokens across a number of language consultants as well as tokens produced by a single signer.

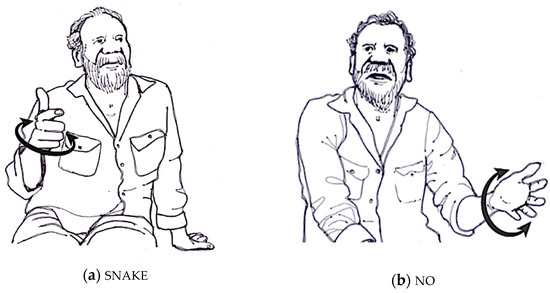

An example of a Kukatja minimal pair which contrasts only in handshape is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

A Kukatja minimal pair for handshape (a) snake (b) no (Illustrations: Jennifer Taylor).

Our Kukatja sign data contain only two compound signs. These signs use three handshapes which all appear in monomorphemic signs and so do not contribute any novel handshapes. One handshape—the  handshape—can be considered a borrowing from common gestural practices across Australia, as it is only used in the sign three. Though it may be ‘non-native’, it has been included, as it is contrastive with a number of other handshapes.

handshape—can be considered a borrowing from common gestural practices across Australia, as it is only used in the sign three. Though it may be ‘non-native’, it has been included, as it is contrastive with a number of other handshapes.

handshape—can be considered a borrowing from common gestural practices across Australia, as it is only used in the sign three. Though it may be ‘non-native’, it has been included, as it is contrastive with a number of other handshapes.

handshape—can be considered a borrowing from common gestural practices across Australia, as it is only used in the sign three. Though it may be ‘non-native’, it has been included, as it is contrastive with a number of other handshapes.The four most frequent handshapes in the Kukatja data (

) account for 75% of handshape tokens in the corpus, while the five least frequent appear in only one sign each, such as the

) account for 75% of handshape tokens in the corpus, while the five least frequent appear in only one sign each, such as the  handshape for goanna and the ‘horn’ handshape

handshape for goanna and the ‘horn’ handshape  for blue tongue lizard.

for blue tongue lizard.

) account for 75% of handshape tokens in the corpus, while the five least frequent appear in only one sign each, such as the

) account for 75% of handshape tokens in the corpus, while the five least frequent appear in only one sign each, such as the  handshape for goanna and the ‘horn’ handshape

handshape for goanna and the ‘horn’ handshape  for blue tongue lizard.

for blue tongue lizard.4.1.3. Yolngu

For the Yolngu dataset, Bauer (2014, p. 77) identified 33 phonetic handshapes. James et al. (2020, p. 18) list 25 handshapes that they call the “most recognisable”, but they do not refer to either their phonemic or phonetic status. While these differences may have resulted from the amount of data available, there are also some methodological differences. James et al. (2020) differentiate between the  handshape and the

handshape and the  handshape (an extremely relaxed articulation) and between the ‘horns’ handshape with and without the extension of the thumb. We have, however, found no examples in our data where the relaxed articulation or the position of the thumb in the ‘horns’ handshape might be contrastive. Therefore, we treat these handshapes as variants.

handshape (an extremely relaxed articulation) and between the ‘horns’ handshape with and without the extension of the thumb. We have, however, found no examples in our data where the relaxed articulation or the position of the thumb in the ‘horns’ handshape might be contrastive. Therefore, we treat these handshapes as variants.

handshape and the

handshape and the  handshape (an extremely relaxed articulation) and between the ‘horns’ handshape with and without the extension of the thumb. We have, however, found no examples in our data where the relaxed articulation or the position of the thumb in the ‘horns’ handshape might be contrastive. Therefore, we treat these handshapes as variants.

handshape (an extremely relaxed articulation) and between the ‘horns’ handshape with and without the extension of the thumb. We have, however, found no examples in our data where the relaxed articulation or the position of the thumb in the ‘horns’ handshape might be contrastive. Therefore, we treat these handshapes as variants.Through analysis of Yolngu handshape minimal pairs in our dataset, there appear to be 17 distinctive handshapes. The six most frequent phonemic handshapes in the Yolngu data (

) account for 90% of sign tokens in the corpus, while the remaining 11 handshapes appear in only 10% of all signs. Some of these remaining handshapes are very infrequent and only ‘weakly’ contrastive, since they appear in only one or two signs in the data. These are, for example, the ‘claw’ handshape

) account for 90% of sign tokens in the corpus, while the remaining 11 handshapes appear in only 10% of all signs. Some of these remaining handshapes are very infrequent and only ‘weakly’ contrastive, since they appear in only one or two signs in the data. These are, for example, the ‘claw’ handshape  , which occurs only in the sign dhiŋga-die, be sick and the ‘nyoka’ handshape

, which occurs only in the sign dhiŋga-die, be sick and the ‘nyoka’ handshape  , named in Yolngu for the only sign which uses the handshape: nyoka-crab.

, named in Yolngu for the only sign which uses the handshape: nyoka-crab.

) account for 90% of sign tokens in the corpus, while the remaining 11 handshapes appear in only 10% of all signs. Some of these remaining handshapes are very infrequent and only ‘weakly’ contrastive, since they appear in only one or two signs in the data. These are, for example, the ‘claw’ handshape

) account for 90% of sign tokens in the corpus, while the remaining 11 handshapes appear in only 10% of all signs. Some of these remaining handshapes are very infrequent and only ‘weakly’ contrastive, since they appear in only one or two signs in the data. These are, for example, the ‘claw’ handshape  , which occurs only in the sign dhiŋga-die, be sick and the ‘nyoka’ handshape

, which occurs only in the sign dhiŋga-die, be sick and the ‘nyoka’ handshape  , named in Yolngu for the only sign which uses the handshape: nyoka-crab.

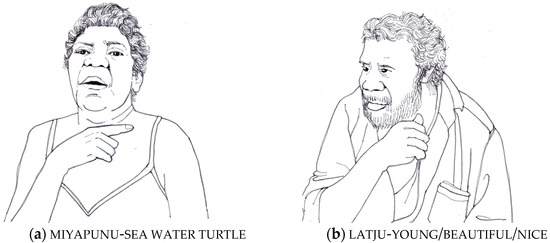

, named in Yolngu for the only sign which uses the handshape: nyoka-crab.Like Kukatja sign, the Yolngu data have a reasonable amount of variation in the handshape parameter. The sign miyapunu-sea water turtle (Figure 5a), while consistently realised with contact on the throat, can be signed, for example, with two different handshapes:  or

or  . Similarly, the sign latju-young, beautiful, nice (Figure 5b) was produced with more than one handshape by a number of different signers:

. Similarly, the sign latju-young, beautiful, nice (Figure 5b) was produced with more than one handshape by a number of different signers:

or

or  . Our Yolngu sign data contain 12 compound signs, such as cold+rain+ix19 ‘cloud’ and stone+ix ‘Darwin’. Similar to Kukatja sign, these Yolngu signs use handshapes which all appear in monomorphemic signs and so do not contribute any additional handshapes.

. Our Yolngu sign data contain 12 compound signs, such as cold+rain+ix19 ‘cloud’ and stone+ix ‘Darwin’. Similar to Kukatja sign, these Yolngu signs use handshapes which all appear in monomorphemic signs and so do not contribute any additional handshapes.

or

or  . Similarly, the sign latju-young, beautiful, nice (Figure 5b) was produced with more than one handshape by a number of different signers:

. Similarly, the sign latju-young, beautiful, nice (Figure 5b) was produced with more than one handshape by a number of different signers:

or

or  . Our Yolngu sign data contain 12 compound signs, such as cold+rain+ix19 ‘cloud’ and stone+ix ‘Darwin’. Similar to Kukatja sign, these Yolngu signs use handshapes which all appear in monomorphemic signs and so do not contribute any additional handshapes.

. Our Yolngu sign data contain 12 compound signs, such as cold+rain+ix19 ‘cloud’ and stone+ix ‘Darwin’. Similar to Kukatja sign, these Yolngu signs use handshapes which all appear in monomorphemic signs and so do not contribute any additional handshapes.

Figure 5.

A Yolngu minimal pair for handshape (a) miyapunu-sea water turtle (b) latju-young/beautiful/nice (Illustrations: Jennifer Taylor).

Figure 5 shows a Yolngu minimal pair which is distinguished by the handshape parameter.

4.2. Relative Frequency and Markedness of Handshapes

The handshape inventories of Kukatja SL, Yolngu SL and Warlpiri SL vary in size from 17 to 35. There is some overlap, with eleven phonemic handshapes shared across the three communities, and several more handshapes which are phonemic in one SL but a variant form in another.

Two handshapes present in Kukatja sign are not shared by either Warlpiri or Yolngu, the  handshape used in grow and the

handshape used in grow and the  handshape used in rock wallaby. Though it has the smallest inventory, Yolngu also exhibits a number of handshapes that are not present in either of the other SLs. These include the

handshape used in rock wallaby. Though it has the smallest inventory, Yolngu also exhibits a number of handshapes that are not present in either of the other SLs. These include the  handshape in bäru-crocodile, and the ‘nyoka’ handshape

handshape in bäru-crocodile, and the ‘nyoka’ handshape  , which is used only in the sign nyoka-crab.

, which is used only in the sign nyoka-crab.

handshape used in grow and the

handshape used in grow and the  handshape used in rock wallaby. Though it has the smallest inventory, Yolngu also exhibits a number of handshapes that are not present in either of the other SLs. These include the

handshape used in rock wallaby. Though it has the smallest inventory, Yolngu also exhibits a number of handshapes that are not present in either of the other SLs. These include the  handshape in bäru-crocodile, and the ‘nyoka’ handshape

handshape in bäru-crocodile, and the ‘nyoka’ handshape  , which is used only in the sign nyoka-crab.

, which is used only in the sign nyoka-crab.Percentages are calculated based on token counts to capture how handshape can vary significantly across tokens of a sign. Appendix A details the total list of contrastive handshapes present in the three SLs. Thumb position and degree of flexion of the unselected fingers may vary in production. For example, the  handshape with the thumb abducted or adducted does not produce any change in meaning, and so we consider these to be variant forms. Despite similarities in which handshapes are represented, by ranking the eleven shared phonemic handshapes by frequency, we can see that the three SLs utilize their inventories somewhat differently. The ranking of shared handshapes is shown in Table 2.

handshape with the thumb abducted or adducted does not produce any change in meaning, and so we consider these to be variant forms. Despite similarities in which handshapes are represented, by ranking the eleven shared phonemic handshapes by frequency, we can see that the three SLs utilize their inventories somewhat differently. The ranking of shared handshapes is shown in Table 2.

handshape with the thumb abducted or adducted does not produce any change in meaning, and so we consider these to be variant forms. Despite similarities in which handshapes are represented, by ranking the eleven shared phonemic handshapes by frequency, we can see that the three SLs utilize their inventories somewhat differently. The ranking of shared handshapes is shown in Table 2.

handshape with the thumb abducted or adducted does not produce any change in meaning, and so we consider these to be variant forms. Despite similarities in which handshapes are represented, by ranking the eleven shared phonemic handshapes by frequency, we can see that the three SLs utilize their inventories somewhat differently. The ranking of shared handshapes is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Frequencies and token counts for eleven handshapes shared between Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu sign.

Notably, for each SL, the frequency of handshapes can be expressed as an exponential decay curve (Rozelle 2003) such that the most common handshape is much more frequent than the second most common handshape, which in turn is much more frequent than the third most common handshape and so on. These frequencies decrease into a long tail, representing a number of handshapes which occur in only a handful of signs. This same pattern is found in deaf community sign languages such as Kenyan Sign Language (Morgan 2017, p. 148), Auslan (Johnston and Schembri 2007, p. 87), as well as ASL, Korean Sign Language, Sign Language of the Netherlands and NZSL (Rozelle 2003, pp. 94–106).

In the case of Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu, in the long tail of this exponential decay curve are five or so handshapes for each SL which appear in only one sign each, such as  used in Kukatja sign grasshopper, or the

used in Kukatja sign grasshopper, or the  handshape used only in nyoka-crab in Yolngu. These handshapes themselves are not unique to Kukatja or Yolngu, appearing in other sign languages (Johnston and Schembri 2007; Puhl et al. 2018). That they are used in just one sign each is unusual. However, Kendon ([1988] 2013, p. 127) noted a tendency of Australian Indigenous SLs towards “highly specialised” handshapes, which is not seen in deaf community sign languages.

handshape used only in nyoka-crab in Yolngu. These handshapes themselves are not unique to Kukatja or Yolngu, appearing in other sign languages (Johnston and Schembri 2007; Puhl et al. 2018). That they are used in just one sign each is unusual. However, Kendon ([1988] 2013, p. 127) noted a tendency of Australian Indigenous SLs towards “highly specialised” handshapes, which is not seen in deaf community sign languages.

used in Kukatja sign grasshopper, or the

used in Kukatja sign grasshopper, or the  handshape used only in nyoka-crab in Yolngu. These handshapes themselves are not unique to Kukatja or Yolngu, appearing in other sign languages (Johnston and Schembri 2007; Puhl et al. 2018). That they are used in just one sign each is unusual. However, Kendon ([1988] 2013, p. 127) noted a tendency of Australian Indigenous SLs towards “highly specialised” handshapes, which is not seen in deaf community sign languages.

handshape used only in nyoka-crab in Yolngu. These handshapes themselves are not unique to Kukatja or Yolngu, appearing in other sign languages (Johnston and Schembri 2007; Puhl et al. 2018). That they are used in just one sign each is unusual. However, Kendon ([1988] 2013, p. 127) noted a tendency of Australian Indigenous SLs towards “highly specialised” handshapes, which is not seen in deaf community sign languages.Some initial observations of differences between the regions can also be made. The most frequent handshapes in all data sets are the  handshape and the

handshape and the  handshape. For Kukatja and Yolngu, the handshapes with next highest frequency are

handshape. For Kukatja and Yolngu, the handshapes with next highest frequency are  and

and  . For Warlpiri, the next most common shapes are the

. For Warlpiri, the next most common shapes are the  handshape and

handshape and  . The

. The  handshape is noteworthy in its relative prominence in Warlpiri, accounting for 6% of sign tokens, compared to less than 1% in both Kukatja and Yolngu. Conversely, the

handshape is noteworthy in its relative prominence in Warlpiri, accounting for 6% of sign tokens, compared to less than 1% in both Kukatja and Yolngu. Conversely, the  handshape is about two times more common in Kukatja and Yolngu than in Warlpiri. The three sign languages under study show differences in their rankings of handshapes after this point. Kukatja uses the

handshape is about two times more common in Kukatja and Yolngu than in Warlpiri. The three sign languages under study show differences in their rankings of handshapes after this point. Kukatja uses the  and

and  handshapes more frequently than Warlpiri or Yolngu. The handshapes

handshapes more frequently than Warlpiri or Yolngu. The handshapes  and

and  are common in Yolngu and

are common in Yolngu and  and

and  are common in Warlpiri (see Appendix A).

are common in Warlpiri (see Appendix A).

handshape and the

handshape and the  handshape. For Kukatja and Yolngu, the handshapes with next highest frequency are

handshape. For Kukatja and Yolngu, the handshapes with next highest frequency are  and

and  . For Warlpiri, the next most common shapes are the

. For Warlpiri, the next most common shapes are the  handshape and

handshape and  . The

. The  handshape is noteworthy in its relative prominence in Warlpiri, accounting for 6% of sign tokens, compared to less than 1% in both Kukatja and Yolngu. Conversely, the

handshape is noteworthy in its relative prominence in Warlpiri, accounting for 6% of sign tokens, compared to less than 1% in both Kukatja and Yolngu. Conversely, the  handshape is about two times more common in Kukatja and Yolngu than in Warlpiri. The three sign languages under study show differences in their rankings of handshapes after this point. Kukatja uses the

handshape is about two times more common in Kukatja and Yolngu than in Warlpiri. The three sign languages under study show differences in their rankings of handshapes after this point. Kukatja uses the  and

and  handshapes more frequently than Warlpiri or Yolngu. The handshapes

handshapes more frequently than Warlpiri or Yolngu. The handshapes  and

and  are common in Yolngu and

are common in Yolngu and  and

and  are common in Warlpiri (see Appendix A).

are common in Warlpiri (see Appendix A). Particularly interesting is the status of the ‘horns’ handshape  across the three Australian Indigenous SLs, being a phonemic handshape in both Warlpiri and Kukatja, but not in Yolngu, where it has been labelled a “marginal handshape” (Adone and Maypilama 2014, p. 24; Bauer 2014, p. 83; James et al. 2020). For Warlpiri, the ‘horns’ handshape represents 5% of the handshape count and is used in many signs including mother and sky (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128).20 Its use appears to be concentrated in Central Australia as it makes up less than 1% of sign tokens in Kukatja and is used in only one sign, blue tongue lizard (Jorgensen 2020). The prevalence of the ‘horns’ handshape in NCD may be a small point of difference between signing practices in these regions.

across the three Australian Indigenous SLs, being a phonemic handshape in both Warlpiri and Kukatja, but not in Yolngu, where it has been labelled a “marginal handshape” (Adone and Maypilama 2014, p. 24; Bauer 2014, p. 83; James et al. 2020). For Warlpiri, the ‘horns’ handshape represents 5% of the handshape count and is used in many signs including mother and sky (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128).20 Its use appears to be concentrated in Central Australia as it makes up less than 1% of sign tokens in Kukatja and is used in only one sign, blue tongue lizard (Jorgensen 2020). The prevalence of the ‘horns’ handshape in NCD may be a small point of difference between signing practices in these regions.

across the three Australian Indigenous SLs, being a phonemic handshape in both Warlpiri and Kukatja, but not in Yolngu, where it has been labelled a “marginal handshape” (Adone and Maypilama 2014, p. 24; Bauer 2014, p. 83; James et al. 2020). For Warlpiri, the ‘horns’ handshape represents 5% of the handshape count and is used in many signs including mother and sky (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128).20 Its use appears to be concentrated in Central Australia as it makes up less than 1% of sign tokens in Kukatja and is used in only one sign, blue tongue lizard (Jorgensen 2020). The prevalence of the ‘horns’ handshape in NCD may be a small point of difference between signing practices in these regions.

across the three Australian Indigenous SLs, being a phonemic handshape in both Warlpiri and Kukatja, but not in Yolngu, where it has been labelled a “marginal handshape” (Adone and Maypilama 2014, p. 24; Bauer 2014, p. 83; James et al. 2020). For Warlpiri, the ‘horns’ handshape represents 5% of the handshape count and is used in many signs including mother and sky (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 128).20 Its use appears to be concentrated in Central Australia as it makes up less than 1% of sign tokens in Kukatja and is used in only one sign, blue tongue lizard (Jorgensen 2020). The prevalence of the ‘horns’ handshape in NCD may be a small point of difference between signing practices in these regions.These frequency counts also serve to satisfy the first proposed criterion for determining unmarked handshapes in a given sign language, as described in Section 2.1. Another metric for unmarked handshapes comes from the dominance condition, which states that in asymmetrical signing the “specification of the passive handshape is restricted” (Battison 1978, p. 34). Thus, we can expect a limited set of handshapes in this context in our SLs, and this does appear to be the case. In Warlpiri,

and

and  represent the nondominant handshape for 90% of asymmetrical two-handed signs. In Kukatja, the non-dominant hand overwhelmingly has either a

represent the nondominant handshape for 90% of asymmetrical two-handed signs. In Kukatja, the non-dominant hand overwhelmingly has either a

or

or  handshape. These three handshapes and their variants account for 89% of relevant tokens. The handshapes

handshape. These three handshapes and their variants account for 89% of relevant tokens. The handshapes

and

and  were used most often by the non-dominant hand in non-symmetrical signs in the Yolngu data.

were used most often by the non-dominant hand in non-symmetrical signs in the Yolngu data.

and

and  represent the nondominant handshape for 90% of asymmetrical two-handed signs. In Kukatja, the non-dominant hand overwhelmingly has either a

represent the nondominant handshape for 90% of asymmetrical two-handed signs. In Kukatja, the non-dominant hand overwhelmingly has either a

or

or  handshape. These three handshapes and their variants account for 89% of relevant tokens. The handshapes

handshape. These three handshapes and their variants account for 89% of relevant tokens. The handshapes

and

and  were used most often by the non-dominant hand in non-symmetrical signs in the Yolngu data.

were used most often by the non-dominant hand in non-symmetrical signs in the Yolngu data. Taking the handshapes which are most frequent and used by the non-dominant hand gives us an unmarked set for each Australian Indigenous SL (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Unmarked handshapes in a number of sign languages.

Generally, the sets of unmarked handshapes for Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu sign are similar. However, comparing these handshapes with what had been proposed as basic handshapes for ASL (Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006), BSL (Sutton-Spence and Woll 1999), and Kata Kolok (De Vos 2012), this appears to be a larger crosslinguistic trend rather than indicative of a close relationship between the three Australian SLs. As expected, most unmarked handshapes in Table 3 can be represented with minimal feature specifications such as [one] or [all] for selected fingers, and maximally distinct joint aperture (i.e., fully open, fully closed).

4.3. Symmetry, Handedness and Dominance

Perhaps the most significant finding of our data is that these three Australian Indigenous SLs adhere to proposed ‘fundamental’ characteristics of well-formedness taken from research on the structure of deaf community SLs and outlined in Section 2.1. Two-handed signs will either be fully symmetrical, with the same handshape and movement pattern for each hand, or the dominant hand will act on the nondominant hand which remains stationary and uses only a limited set of handshapes.

As Table 4 shows, both Yolngu and Kukatja show a preference for symmetry in two handed signs, with over 90% of signs in Yolngu falling under Battison’s (1978) type 1 category. Non-symmetrical two-handed signs (Type 2 and Type 3) are less common in our datasets. In Kukatja, for instance, out of 223 two-handed sign tokens, 131 (59%) exhibit total symmetry in both movement and handshape, 60 (27%) have symmetry in handshape but not movement, and 32 (14%) lack symmetry in both handshape and movement. This follows the expected cline of lack of symmetry and increased complexity, with more complex signs being less common in the lexicon.

Table 4.

Symmetry and asymmetry in two-handed sign tokens in Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu SLs.

Interestingly, Warlpiri shows the complete opposite trend, with a preference for asymmetrical two-handed signing. This pattern may be due to the redundancy of the nondominant hand in symmetrical two-handed signs. Kendon ([1988] 2013, p. 114) notes that “many signs cited in one-handed form may often be performed by both hands acting in unison (it is occasionally hard to decide whether a sign should be classed as unimanual or bimanual symmetric because of this tendency)”. These findings lend strength to the cross-linguistic validity of Battison’s (1978) types and suggest that Australian Indigenous SLs follow the Symmetry and Dominance Conditions just as deaf community SLs do.

In contrast, the structural considerations of handedness and dominance do not appear to exhibit the same patterns in Australian Indigenous SLs as they do in deaf community sign languages. We find a preference for one-handedness, and for flexibility in hand dominance. As can be seen in Table 5, there is an uneven distribution of one-handed vs. two-handed signs in Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu. The majority of signs in our three datasets were articulated with one hand, while approximately only a third of all signs were performed with both hands (i.e., type 1, type 2 or type 3). This preponderance of one-handedness was previously noticed by Kendon ([1988] 2013) in North Central Desert SLs. Other alternate sign languages, such as Ts’xa hunting signs, have been reported to favour one-handed signing as well (Mohr 2015).

Table 5.

Percentage of one vs. two-handed sign tokens21 in three Australian Indigenous sign languages and BSL.

A propensity toward one-handed signs in Australian Indigenous SLs is striking when compared to deaf community SLs. The study of BSL lexicon by Sutton-Spence and Kaneko (2007, p. 290) reveals, for example, quite the opposite pattern. From a sample of 1736 BSL signs, 62% were two-handed signs. Eighteen signs (1%) involved movement from one handedness to two handedness.

Users of Australian sign languages also freely switch hand dominance, sometimes in the middle of an utterance. In the Kukatja data, while all the signers appear to be right-handed and favour this hand when signing, they frequently switch between hands. Flexibility in hand dominance was also noted by Kendon for the NCD, where signers could “enact signs with right or left hand with equal facility” (Kendon [1988] 2013, p. 116).

In summary, more than a half of Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu signs are performed with one hand. If the sign is two-handed, it is very likely to be a symmetrical sign, in which the non-dominant hand shares selected finger, joint and movement specifications with the dominant hand. In both one-handed and two-handed signing, signers may switch, with either hand becoming the dominant articulator.

4.4. Body Anchored Signs and Signing Space

In our analysis of the three data sets, we coded sign types for places of articulation on the body, excluding articulation on the non-dominant hand. We did not include the non-dominant hand as a body location, as these signs are still produced in neutral space, meaning they are simply two-handed. This distinguishes ‘body-articulated’ signs from what may be considered ‘body-anchored’ signs, in which the place of articulation on the body is semantically motivated in some way.

Warlpiri sign has 26 possible body locations, which function as a place of articulation for 382 body-anchored signs, 29% of the total sign count. In Kukatja sign, 80 signs (38%) involve contact or reference to a body part, with 25 different body locations represented in the dataset. Yolngu signs are also articulated on the body in one of 26 possible places of articulation, with 116 (41%) signs involving contact or reference to a body part. Table 6 shows the location of body-anchored signs for each.

Table 6.

Places of articulation on the body in Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu SL.

For Kukatja and Yolngu, the most frequently used body part for sign location is the mouth, in signs such as speak, drink, and eat in both languages. Yolngu also has many signs articulated on the chest (sick, like), the head (woman, live, tea) or the eye (see, glasses, boyfriend). Kukatja body-anchored signs are frequently produced on the stomach (hungry, fat, hair-belt), chest (happy/proud feeling, pain/ache, homesick), the head (think, forget, mad/insane) and the ear (hear/listen, phone). In Warlpiri, the most common places of articulation on the body are the temple (comb, forget, bullock), face (grief, honeyeater, mirage) and chest (cough, worry, anger).

We observe especially strong variation in handshape in body-anchored signs. Thus, the Yolngu sign yothu-child, which is produced near, on, or involving contact with the mouth, can be signed with the

or

or  handshapes. In such signs involving contact or reference to a body part, the location of the sign is ‘meaning-bearing’ and appears to be a more salient parameter than handshape or movement. This may allow handshapes to be more freely realised as long as place of articulation remains consistent, and this could account for the handshape variation we find in the data.

handshapes. In such signs involving contact or reference to a body part, the location of the sign is ‘meaning-bearing’ and appears to be a more salient parameter than handshape or movement. This may allow handshapes to be more freely realised as long as place of articulation remains consistent, and this could account for the handshape variation we find in the data.

or

or  handshapes. In such signs involving contact or reference to a body part, the location of the sign is ‘meaning-bearing’ and appears to be a more salient parameter than handshape or movement. This may allow handshapes to be more freely realised as long as place of articulation remains consistent, and this could account for the handshape variation we find in the data.

handshapes. In such signs involving contact or reference to a body part, the location of the sign is ‘meaning-bearing’ and appears to be a more salient parameter than handshape or movement. This may allow handshapes to be more freely realised as long as place of articulation remains consistent, and this could account for the handshape variation we find in the data.The ways that signs are articulated on the body in Australian Indigenous SLs is a point of difference when compared to deaf community SLs. A number of signs across our three SLs are produced low down on the body—on the thigh, knee, shin or foot. Signs may also be articulated on the back, for example in the Yolngu sign märi-mother’s mother. A proliferation of locations lower on the body speaks to a larger signing space than established for urban deaf community SLs, which is generally restricted vertically from above the head to around the belly button (Klima and Bellugi 1979). Warlpiri, Kukatja, and Yolngu SLs all use a signing space which may extend to utilise the entire body (Bauer 2014; Kendon [1988] 2013; Nyst 2012).

5. Discussion

Our findings show that Australian Indigenous SLs share many structural features with deaf community SLs. These include the general size of handshape inventory and frequency patterns, presence of minimal pairs, unmarked and marked handshapes, and adherence to both the Symmetry Condition and the Dominance Condition. As far as these metrics, taken from deaf community SLs, can be applied as universal standards for the presence of sign language phonology, these features show that Australian Indigenous SLs have more than mere “kernels” of phonology (Sandler et al. 2011, p. 4). Importantly, the fact that alternate SLs exhibit these metrics too lends strength to their proposed universality.

The similarities we see in comparing Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu to each other and to deaf community SLs highlight underlying features that sign systems, which arose out of quite different socio-cultural contexts, have in common. Such underlying features are thus likely to be brought about by cognitive and articulatory pressures on users of sign such as cognitive load and ease of articulation. This can be seen in the Symmetry and Dominance Conditions which formalise restrictions on sign complexity so that signs are not too difficult to produce or process (Battison 1978). Likewise, many languages share similar sets of unmarked handshapes, not because of any historical relationship between SLs, but because they are less complex and easier to produce forms which have been shown to be much more frequently used in the lexicon of any given SL. This same tendency underpins Zipf’s Law (Zipf 1935).

Comparing Warlpiri, Kukatja and Yolngu to each other and to deaf community sign languages also suggests what may be cross-linguistically variable in sign features. In our datasets, we have found a preference for one-handed signing, in contrast to deaf community SLs, in which the distribution of one vs. two-handed signs is more balanced. We also see a willingness to freely switch hand dominance. While urban deaf community SLs tend to prefer a particular hand as the dominant articulator in one-handed signing, van der Hulst and van der Kooij point out that signers of deaf community SLs may “easily switch to the other hand when it is necessary or convenient” (van der Hulst and van der Kooij 2021). Thus, it appears that this difference in sign use is not as pronounced as previously thought, simply because as humans we will sometimes have only one hand available for signing and it may not always be the dominant one. We have also shown that many signs in our data are produced with variable handshapes on a wide range of body parts that extends beyond the signing space commonly described for deaf community SLs.

These differences between Australian Indigenous SLs and deaf community SLs do not necessarily represent a lack of phonological patterning or a ‘developing’ phonology but rather can be explained in relation to the overall semiotic system of which signing is just one part, as well as culturally specific signing practices shared by interlocutors in a small-scale community. After all, sign languages do not exist in a vacuum. We can expect that when present, speech, sign, gesture and environmental and interactional pressures will overlap and influence each other to some degree. A growing consideration of the gestural repertoires of signers is a promising start to unpacking some of these interdependencies (Goldin-Meadow and Brentari 2017; Kusters and Sahasrabudhe 2018; Müller 2018). Although we have suggested that the criteria of ‘well-formedness’ is one that delineates sign from gesture, a clear-cut distinction cannot be made. The role of gesture in signed utterances is further complicated when signing may be accompanied by speech. It is striking that the most common unmarked handshapes are also those documented in gestural repertoires in Indigenous Australia (see for example Wilkins 2003).

Some differences in the extent of available places of articulation on the body are also likely due to sociocultural and environmental factors. Language consultants preferred to communicate and be filmed while sitting cross-legged on the ground, with easy access to their legs. Such a position during conversation is also not unusual in daily life in Australian Indigenous communities. However, it has been shown that signers still articulate some signs lower on the body, even when standing up (Bauer 2014, p. 124). Nyst (2012, p. 563) also suggests that the number of hearing signers may have an effect on the linguistic organisation of space, noting that “a proliferation of locations, including locations not commonly used in sign languages of large Deaf communities (e.g., below the waist or behind the body), seem to be common to most shared sign languages”.23

In addition, although not always the case, some places of articulation may be semantically motivated. For instance, the location on the side of the forehead is frequently associated with the meaning ‘mental state or process’ in various sign languages such as the signs think, understand in ASL, forget in German Sign Language or smart in Russian Sign Language. We also observe this pattern of iconicity in our data. For example, the location near the mouth is associated with signs such as speak, drink, and eat in the languages under study.

As well as sign forms motivated by visual similarities to their referent, Australian Indigenous signs may be semantically motivated in terms of, and exhibit places of articulation on the body part related to, metaphorical extensions found in speech and in non-verbal cultural practices. Particular body locations appear to be very salient for the production of such signs. Signs for kin are one of the best-known examples of this (Green et al. 2018), but there are other examples which highlight the close semantic relationship between these semiotic systems—sign and speech, in these communities. For example, in spoken Yolngu languages, body part terms are commonly used to refer to geographical features, such as mayan ‘throat’, which also denotes ‘creek’. This link is also mirrored in Yolngu sign, where creek is signed by pointing to or touching the throat, using variable handshapes.

Looking beyond deaf community SLs to a more diverse range of sign languages, we also suggest that the size of the signing space used by signers of Australian Indigenous SLs is not as cross-linguistically unusual as it would first seem, but is a tendency found in some small non-urban SLs. In Kata Kolok (De Vos 2012), some signs are articulated on the leg. African American signers of ASL have been noted to use a larger signing space than found in standard ASL (Hill et al. 2009). Morgan (2017, pp. 232, 578) suggests that a large signing space, including the legs and behind the signer’s body, might be a common feature of African SLs, “no matter their age, population size, or complexity”. Two other descriptions of African SLs—Hausa Sign Language from Nigeria (Schmaling 2000) and Adamorobe Sign Language from Ghana (Nyst 2007)—both report signs that are located behind the body, including AdaSL signs younger and sibling (ibid., p. 66). It appears that Australian Indigenous SLs are not unique in the size of the signing space, but rather that research has been too hasty in stating typological tendencies, being based on a small and often related set of SLs. Size of the signing space clearly does differ across SLs, resulting in more or less available places of articulation, but the range of SLs which show a larger signing space than previously assumed suggests it may be urban deaf community SLs which are the typologically unusual ones.

6. Conclusions

This paper represents the first in-depth comparison of phonological aspects of Australian Indigenous SLs to be based on analysis of signing practices from a broad selection of geographic regions. It builds on the work of Kendon ([1988] 2013) on SLs from the NCD and provides a unique contribution to understandings of Australian Indigenous SLs and their typological profile in relation to other SLs. Our analysis captures the systematic structure of the handshape inventories of these languages, frequency patterns, presence of minimal pairs, the occurrence of simpler and more frequently occurring ‘unmarked’ units, and adherence to both the Symmetry Condition and the Dominance Condition. We highlight three features which are typologically unusual in sign language phonology: strong variation in the handshape parameter, a preference for one-handedness, for body-anchored signing, and the use of a large signing space. We reason these features can be better explained, not by the ‘developmental’ status or time-depth of these languages, but rather by socio-linguistic and culturally specific aspects of signing practices in these communities.

We began this paper by asking whether the evidence shows that Australian Indigenous SLs possess more than mere “kernels” of phonology (see Sandler et al. 2011, p. 4). Our findings show that Australian Indigenous SLs do not constitute a phonological ‘type’ that is fundamentally different to other sign languages—they do not differ substantially in terms of the constraints that specify their inventories of segments and in the ways in which these segments are combined.

While the phonology of Australian Indigenous SLs still remains under-researched, our comparative analysis has taken significant steps. As well as widening the geographical region considered, we have refined techniques that can be applied to the question of how to make valid comparisons across data sets that have been compiled by different researchers using various methodologies. One future development that would assist in this task would be the expansion of existing sign fonts to include the contrastive parameters that we have identified in this paper. Applying metrics developed to describe deaf community SLs to alternate SLs such as those found in Indigenous Australia makes an important contribution to our knowledge of sign structure more generally. Whether considering what the structural commonalities of a diverse range of sign languages says about language and cognition, or what structural differences tell us about the role of socio-cultural context in restricting sign form, Australian Indigenous SLs stand to make an important contribution to research on sign phonology. In general terms, this research adds to knowledge of cross-linguistic variation in the visual modality.