3.1. Word-Initial Engma Deletion

The first area of change examined here is phonological. Phonologically, Kunwok has some typical features of Australian languages: it has a CV(C)(C) syllable structure (

Dixon 1980), a “long flat” consonant series lacking voicing contrast and manner-of-articulation contrast in the obstruents (

Butcher 2006) and makes regular use of the velar nasal (/η/) in the word-initial position (

Donohue et al. 2013). The weakening or deletion of initial consonants is a well-known phenomenon in Australian languages; however, studies have tended to take a historical perspective (e.g.,

Alpher 1976;

Hale 1964;

Dixon 1980,

2002;

Blevins 2001;

Fletcher and Butcher 2014;

Hercus 1979), focusing on diachronic changes and phonetic trends, rather than a sociolinguistic synchronic view (as adopted by

Amery 1985;

Langlois 2004;

Mansfield 2015). Languages neighbouring Kunwok that have some sort of initial consonant lenition documented include Giimbiyu, Gaagudju, Amurdak, Iwaidja, Mawng, Kunbarlang, Burarra and Ngalakgan (

Blevins 2001). Engma is considered to be particularly susceptible to deletion as it has weak perceptual cues, along with other velars, nasals, labials and glides (

Fletcher and Butcher 2014, p. 112).

In Kunwok, initial engma deletion is restricted to closed-class morphemes: noun class and gender prefixes, pronominal prefixes, free pronouns and kin terms

4 (

Marley 2020, forthcoming). Examples (1) and (2) demonstrate how this variable manifests. Note that free pronouns (e.g.,

ngaye and

ngayed) and pronominal prefixes (e.g.,

nga-) may drop the initial velar nasal in example (2) but that prefixless (or zero-prefixed) noun and verb roots such as “Echidna” (

ngarrbek) and “be called/named”

ngeyyo do not permit the initial nasal to be dropped:

| (1) | Sentence with initial engma: |

| | Ngarrbek | ø-ngeyyoy | ... | ø-yimeng | ‘ngaye | nga-re | ku-wardde’ |

| | Echidna | 3m-be.called.PI | | 3m-say.PP | 1sg.DIR | 1m-go.NP | LOC-rock |

| | “Her name was Echidna ... and she said ‘I’m going to the stone country.” |

| | BKC_Carroll_D6 |

| (2) | Sentence with initial engmas deleted: |

| | _A-neke | yi-yimerranj, | _ayed | _a-yimarrang? | _Al-wanjdjuk | _a-yimarra! |

| | VEG.DEM | 2m-become.PP | what | 1m-become.NP | FE-emu | 1m-become.IMP |

| | “That’s what you turned into, [but] what will I turn into? I’ll become an emu!” |

| | BKC_Evans1991_Alwanjuk_emu |

Initial engma deletion is also regionally distributed, with speakers from the eastern region of the dialect chain rarely exhibiting the deleted variant while speakers from the west and south have traditionally always dropped it (

Evans 2003). Bininj from the central region (Kunwinjku speakers) vary in their behaviour, with some speakers never dropping engma, others consistently dropping engma and many showing considerable internal variation (example 3).

| (3) | Ngarrbek | ø-yimeng | ‘Aye | wanjh | nga-re | ku-wardde | nani’. | Wanjh |

| | Echidna | 3m-say.PP | 1sg.DIR | CONJ | 1m-go.NP | LOC-rock | MA.DEM | CONJ |

| | almangayi | ø-yimeng | ‘Mak | ngaye | nga-re | kabbal | nga-yo’. |

| | FE.turtle | 3m-say.PP | INTERJ | 1sg.DIR | 1m-go.NP | plains | 1m-lie.NP |

| | “Echidna said ‘I’m going to the stone country then’ and turtle said ‘Well I’m going to live on the floodplains’.” |

| | BKC_Marley_Conrad_echidnaTortoise01 |

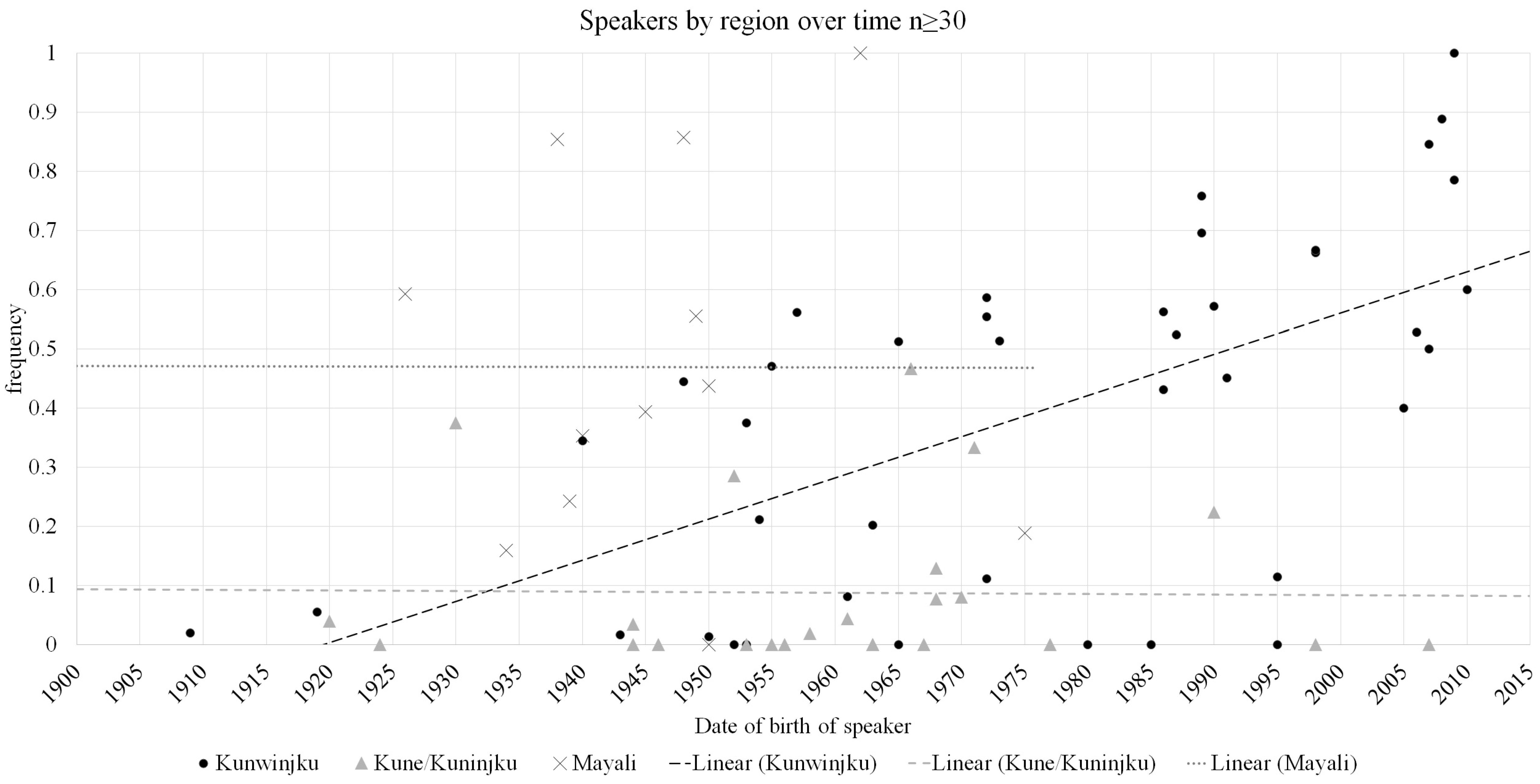

Diachronic analysis of the word-initial engma variable in the BKC indicated that engma deletion is becoming more common over time, particularly in speakers from the central region. The chart in

Figure 2 plots individual speaker data (where n ≥ 30 tokens per speaker) by their birth year and by region. Trendlines

5 for each of the three regional groups indicate that Eastern Kunwok speakers (Kune/Kuninjku) have maintained a low rate of deletion, while there is likely to be a sound change in progress for Kunwinjku speakers as they have had a clear and significant (

p = 0.00003) increase in initial engma deletion over time. Note that the Mayali data are somewhat skewed as the youngest speaker in this sample was born in 1975, and so the Kunwinjku speakers in this dataset are the only ones whose Kunwok is changing.

An age-grading hypothesis for the observable change is unlikely as the recordings span a 60 year period (1959–2019) with several of the older speakers in the BKC recorded when they were young adults. As for Bininj from the east, while there are some outliers, current data suggest that they have not (yet) adopted the variable, possibly helped by the fact that communities in that region tend to socially align themselves with their Rembarrnga and Dalabon-speaking kin, and neither language has been documented to delete the initial engma.

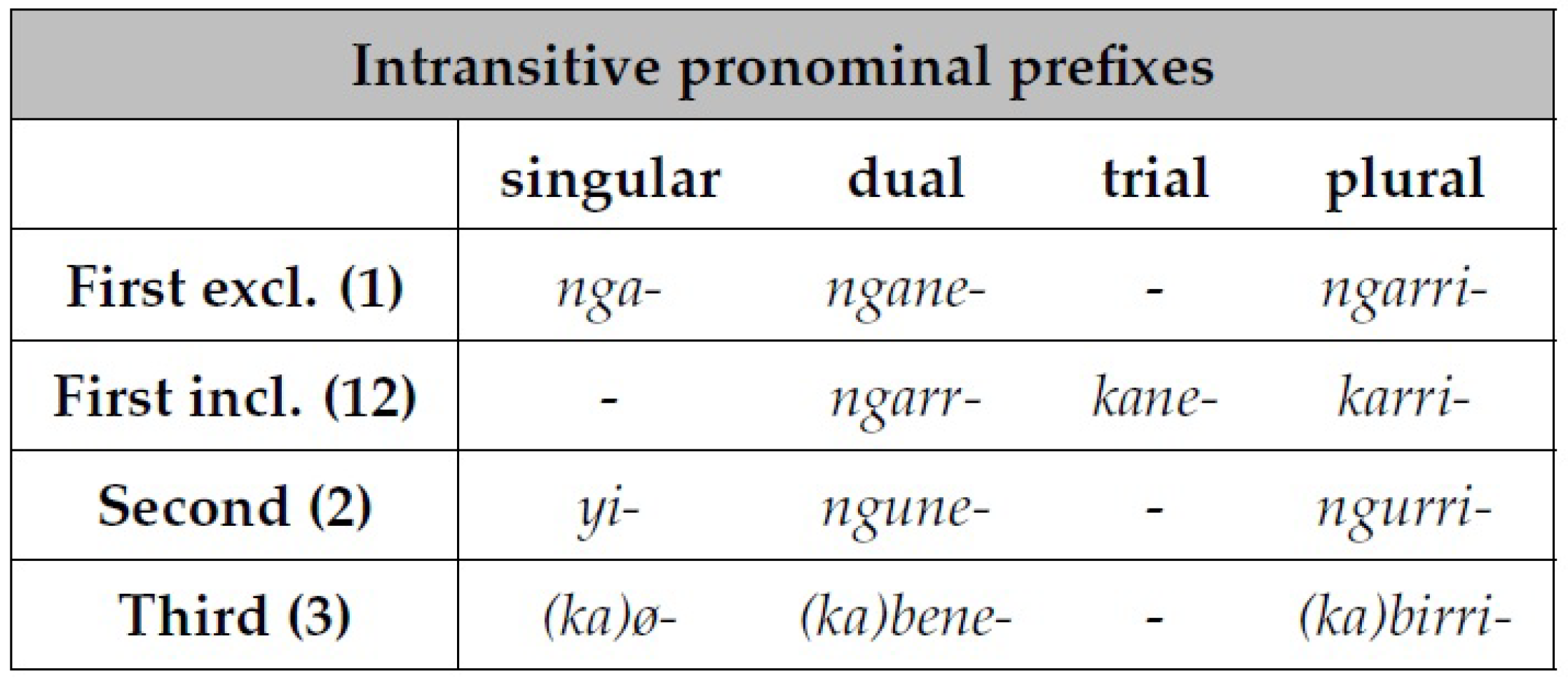

3.2. Pronominal Prefixes in Kunwok

Kunwok has both bound and free pronominal forms, but this paper focuses only on the obligatory bound forms (

Evans 2003). As with most non-Pama-Nyungan languages, Kunwok is a prefixing language with a rich system of pronominal prefixes that affix to verb stems (example (4)) as well as nouns, adverbs, adjectives and numerals (example (5)):

| (4) | Prefix on verb stem: |

| | Ngurri-wam |

| | 2a-go.PP |

| | “You mob went” |

| (5) | Prefix on numeral and nominal predicate: |

| | Bu | ngarri-danjbik | ngarri-wurdurd-ni |

| | CONJ | 1a-three | 1a-child-PI |

| | “When we three were children” |

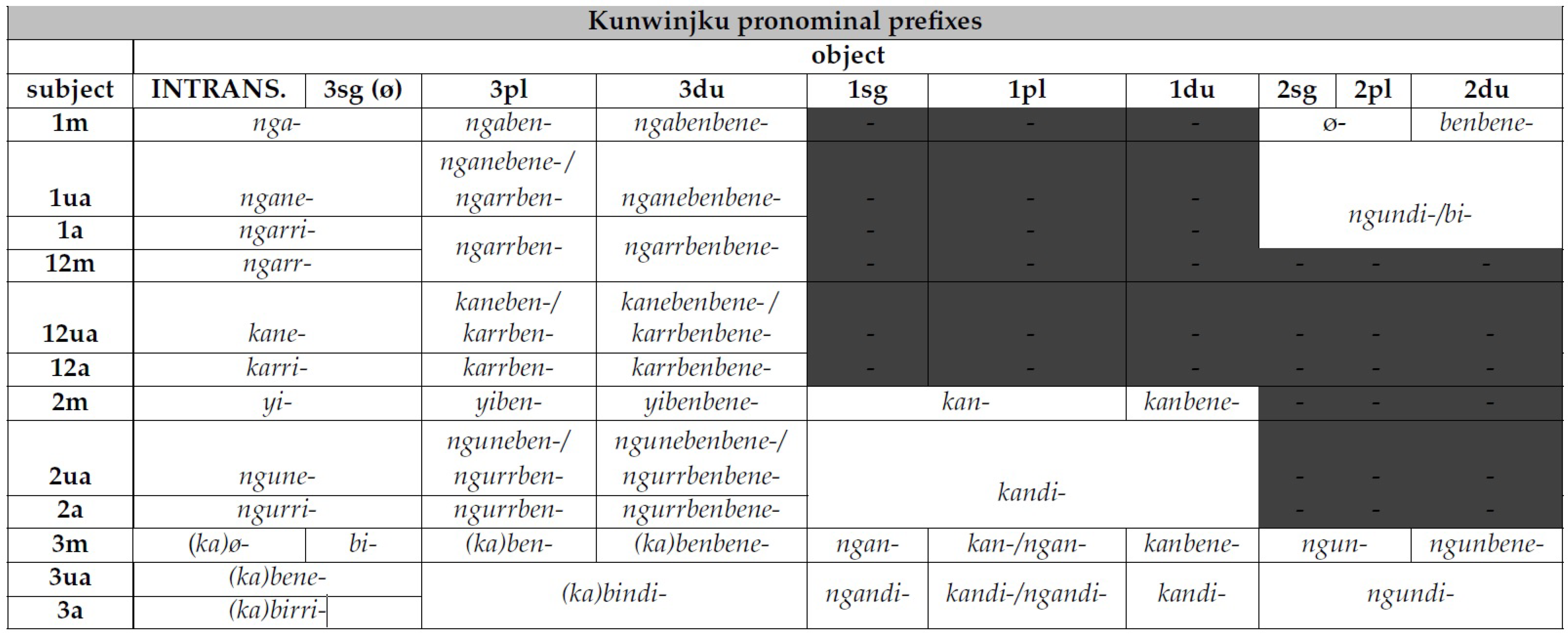

As Kunwok is a polysynthetic language, its verbs can take multiple arguments. A result of this is a set of prononimal prefixes that code both subject and object in a single form, many of which have a semi-regular structure. The convention used for glossing composite transitive pronominal forms is “Subject > Object”; e.g., ngaben- 1m>3pl = 1m.SUB acting on 3pl.OBJ.

| ngabenbene- | 1m>3du | ngaben- | 1m>3pl |

| ngarrbenbene- | 12m>3du | ngarrben- | 12m>3pl |

| yibenbene- | 2m>3du | yiben- | 2m>3pl |

| benbene- | 3m>3du | ben- | 3m>3pl |

This compounding structure, however, is not consistent throughout the whole paradigm, with some combinations syncretising across number, person or clusivity boundaries.

| bindi- | 3ua/3a>3du/3pl |

| ngundi- | 3a>2/1a>2 |

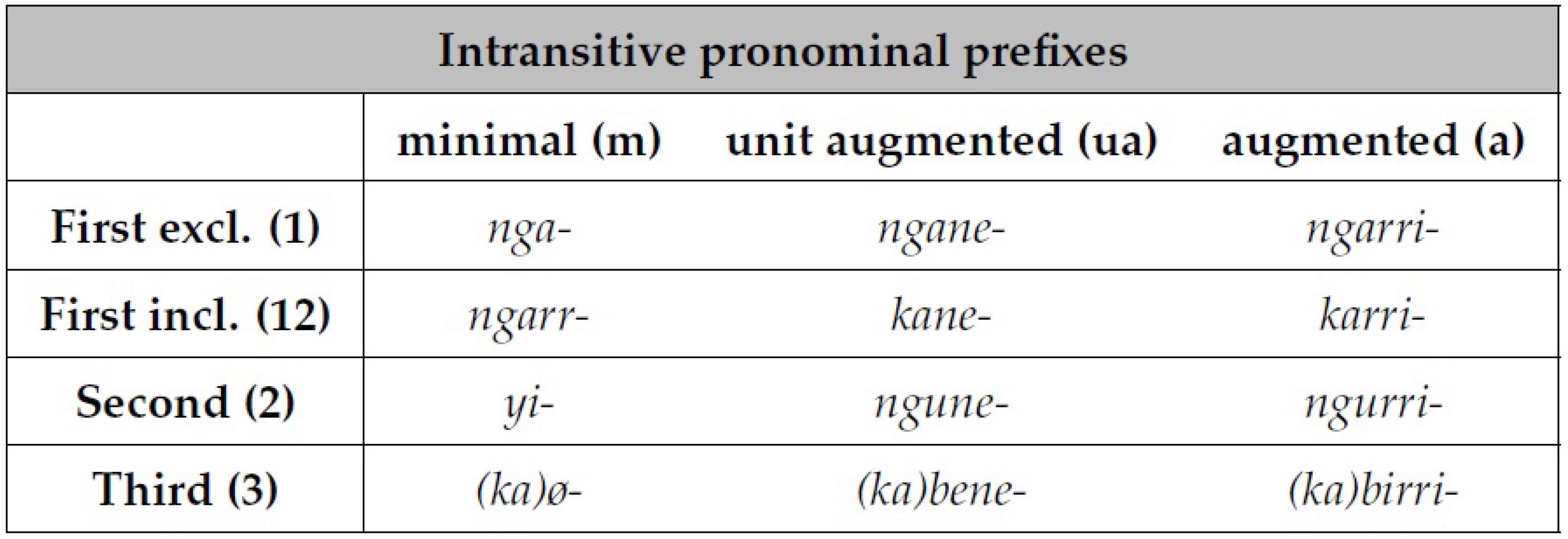

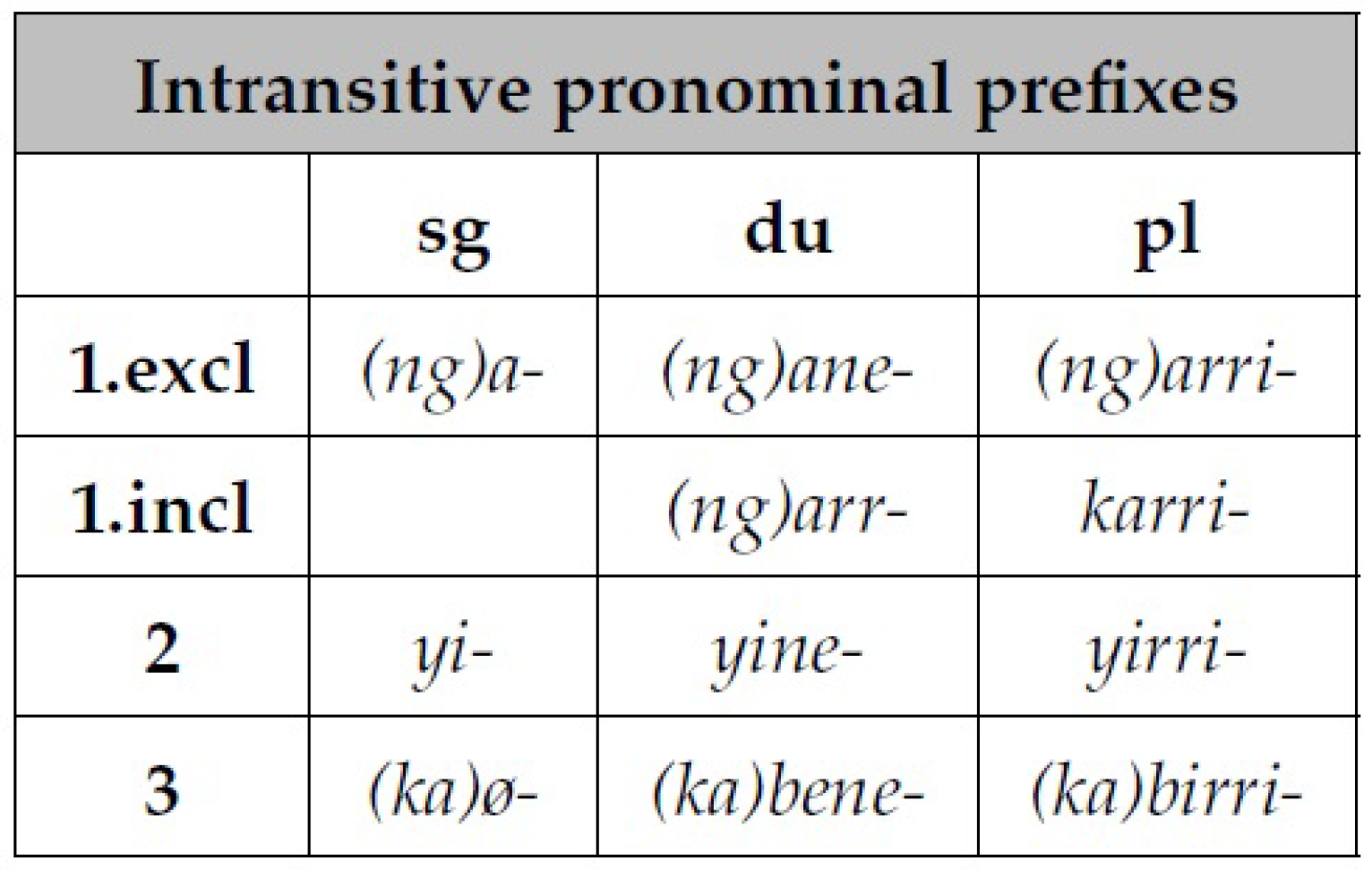

To complicate things further, there are two different formulating patterns for the subject and object. Subjects use a “minimal|unit-augmented|augmented” system (

McKay 1975) while objects adhere to the more common singular|dual|plural number marking. The minimal|unit-augmented|augmented (min|ua|aug) is a way of categorising pronouns according to relative number (

Table 1) instead of absolute number (

Table 2). It is applied to pronominal systems that mark clusivity and have a singular|dual|plural number system.

Evidence that a min|ua|aug arrangement is the most logical schematisation can be seen in the morphological structures of the pronouns; note that all augmented forms end in -rri and all unit-augmented forms end in -ne, suggesting that this arrangement is inherent to the language and not only the wishful projection of order onto the system by linguists.

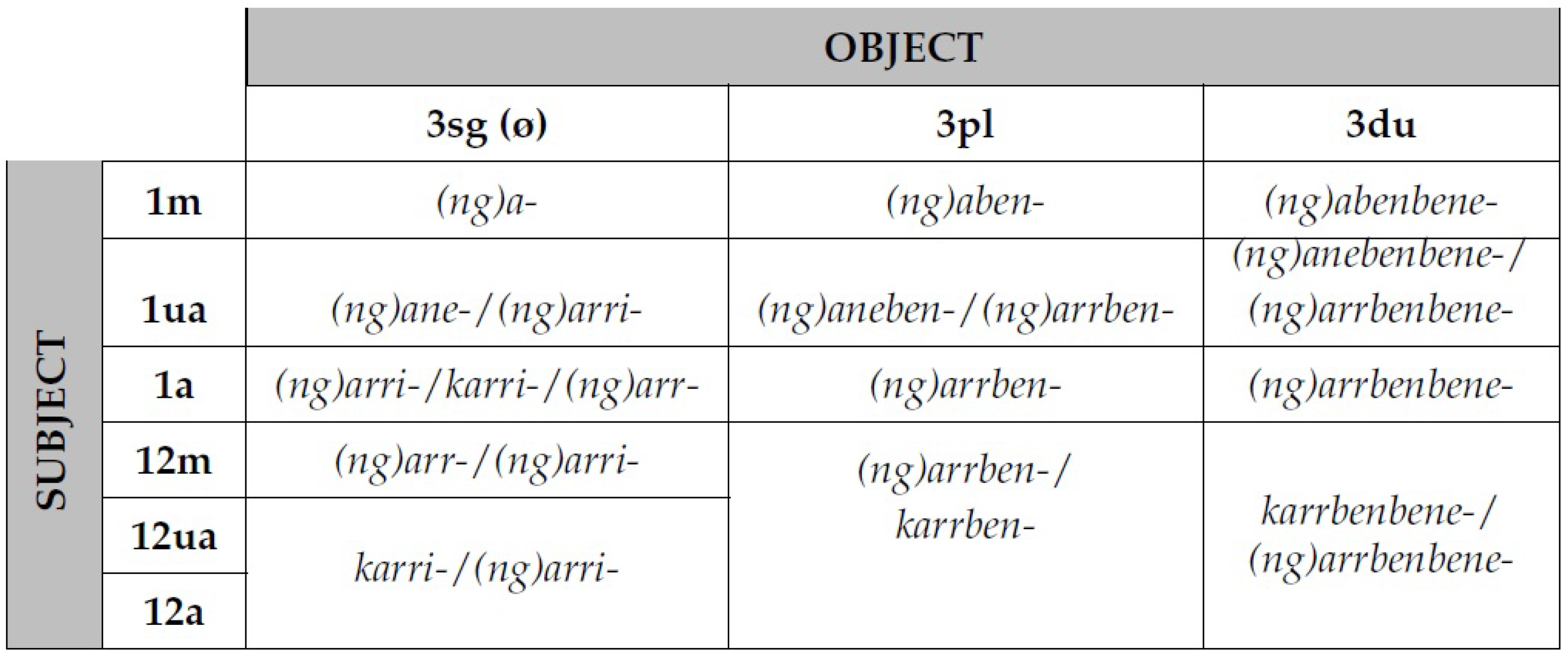

The transitive pronominal paradigm is a somewhat larger and more convoluted matrix.

Table 3 illustrates how the subjects can be placed on the y-axis and objects on the x-axis to create a schema of an attested pronominal prefix paradigm. In the instances where the subject and object are the same (i.e., the blacked-out cells), a reflexive or reciprocal suffix is used with an intransitive prefix form (e.g.,

ngane-na-rr-en [1ua-see-RR-NP], “We were looking at each other”).

This matrix presents the most frequent realisations of the prefixes in the existing grammatical descriptions of Kunwok (

Carroll 1976;

Evans 2003;

Hale 1959;

Oates 1964) but a survey of individual speaker paradigms revealed considerable variation. By comparing the attested pronominal forms of speakers in the BKC, two patterns emerged that correlated with speaker age. The first was the regularisation of second person prefixes, such that the non-singular second person forms (beginning with

ngu-) are brought into line with the singular form

yi-, resulting in

ngune- (2ua) and

ngurri- (2a), respectively, being produced as

yine- and

yirri- (

Section 3.2.1). The second recurring deviation in the above paradigm is in the first-person subject, where there is evidence of number neutralisation and obsolescence of the 12ua form

kane- (

Section 3.2.2).

3.2.1. Regularisation of Second Person Prefixes

The second feature of young people’s Kunwok is a regularisation pattern observed in the second person non-minimal forms (i.e., ua and aug). The regularised forms were first noticed in children’s speech during fieldwork in 2016; however, this pattern has since been recorded in the speech of adults aged up to 45 years (examples 6 and 7).

| (6) | Baleh | ngudda | yine-ma.ng |

| | where | 2.DIR | 2ua>3sg-get.PP |

| | “Where did you get it?” |

| | Janet, 20 years |

| | BKC_Singer_RS1-371 DM2 landmark interview ext lg_JM_RS |

| (7) | Like | yi-bengkan | udda | yirri-wam | the | other | day | kakkak-dorreng | Beatrice |

| | like | 2sg-remember.NP | 2.DIR | 2a-go.PP | the | other | day | MM-COM | Beatrice |

| | “Like, do you remember, you went with kakkak Beatrice the other day” |

| | Chantelle, 31 years |

| | BKC_Marley_Chantelle_kin_Convo |

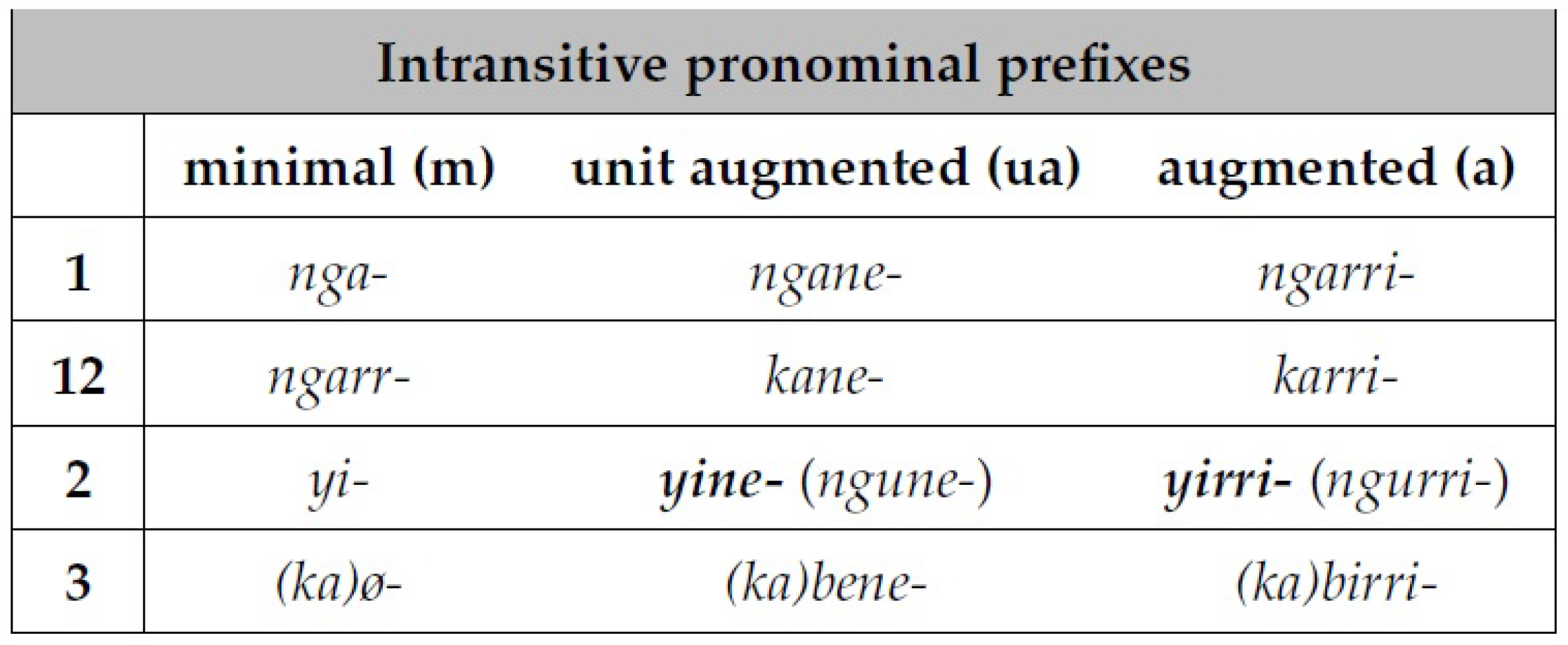

The resulting regularised paradigm is shown here (

Table 4):

Further investigation revealed that speakers who employed this regularised second person prefix also extended this pattern deeper into the paradigm to regularise any pronominal form beginning with ngu- (examples (8)–(10)).

| (8) | Wurdurd | ngaye | ngal-kodjok | and | al-kangila | yindi-bekkan |

| | children | 1sg.DIR | II-skin.name | and | II-skin.name | 1a>2pl-listen.NP |

| | “Children, Ngal-kodjok, Ngal-kangila and I are listening to you” |

| | Alexandria, 19 years |

| | BKC_Marley_Alexandria_prns |

| (9) | Yawurrinj | boken | yinebenbene-na.yinj | al-kodjokodjok |

| | young.man | two | 2ua>3du-see.IRR | II-REDUP.skin.name |

| | “Guys, did you two see Al-kodjokodjok?” |

| | Lorina, 19 years |

| | BKC_Marley_Lorina_prns |

| (10) | Mah | yin-bengkan | ka-yime | ‘beautiful’ |

| | INTERJ | 3m>2sg-know.NP | 3m.NP-say.NP | beautiful |

| | “So she’ll teach you how to say ‘beautiful” |

| | Chantelle, 31 years |

| | BKC_Marley_Chantelle_kin_Convo |

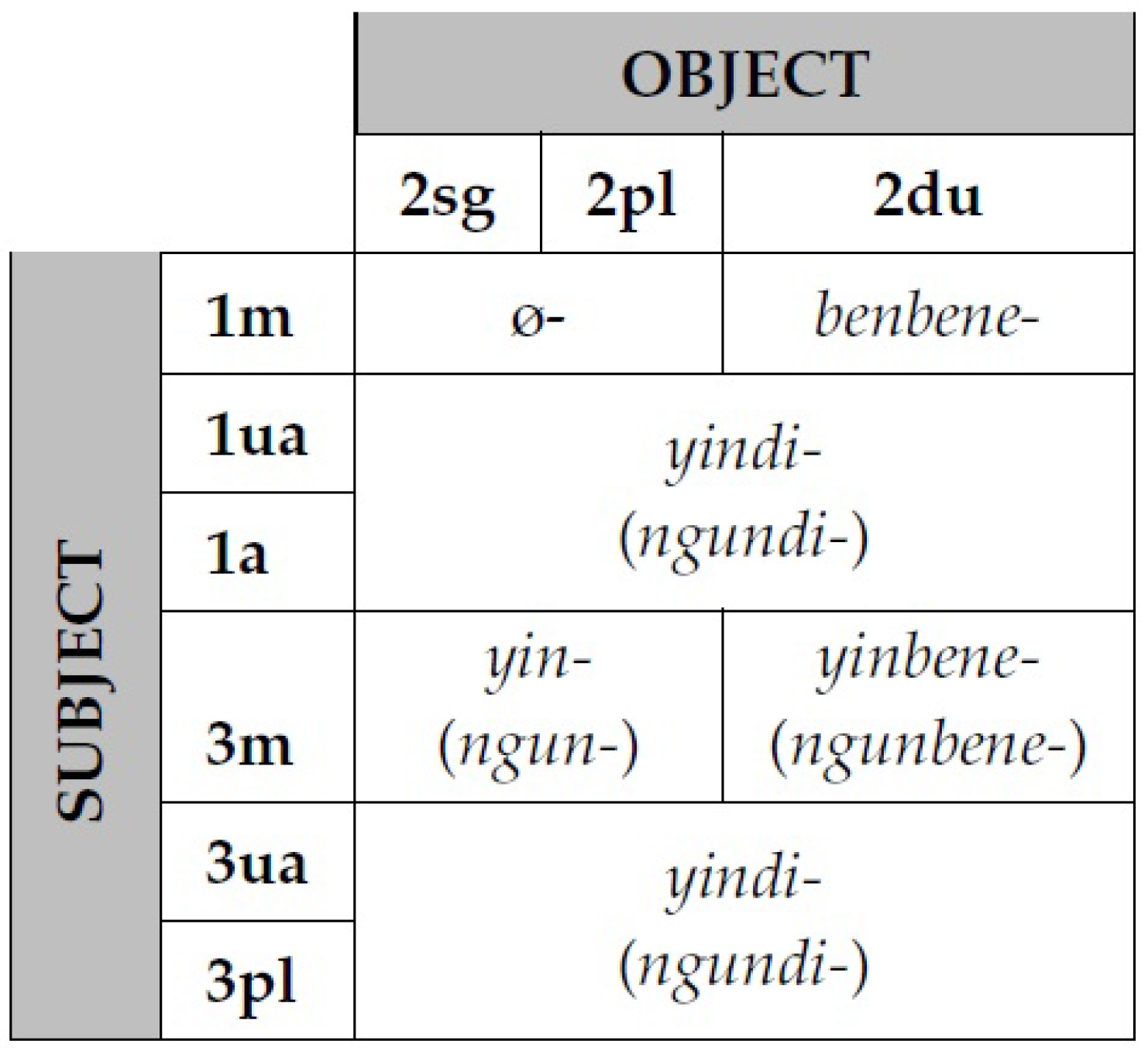

All pronominal prefixes that begin with

ngu- refer to the second person in some way, either as a subject or object, and so the regularisation pattern is occurring in the whole second person prefix series and not only the intransitives (

Table 5 and

Table 6):

Not all speakers who produced yine- and yirri- consistently transferred this pattern across to the more complex forms in the paradigm, and some speakers exhibited internal variation using both the canonical (ngurri-) and the regularised (yirri-) forms (example (11)):

| (11) | Mah | yirri-ray | kurih | ngurri-dirri |

| | well | 2a-go.IMP | there | 2a-play.NP |

| | “Well go over there and play” |

| | Chantelle, 31 years |

| | BKC_Marley_Chantelle_kin_Convo |

Only 11 speakers in the BKC were recorded with a regularised form, so this phenomenon is still emergent.

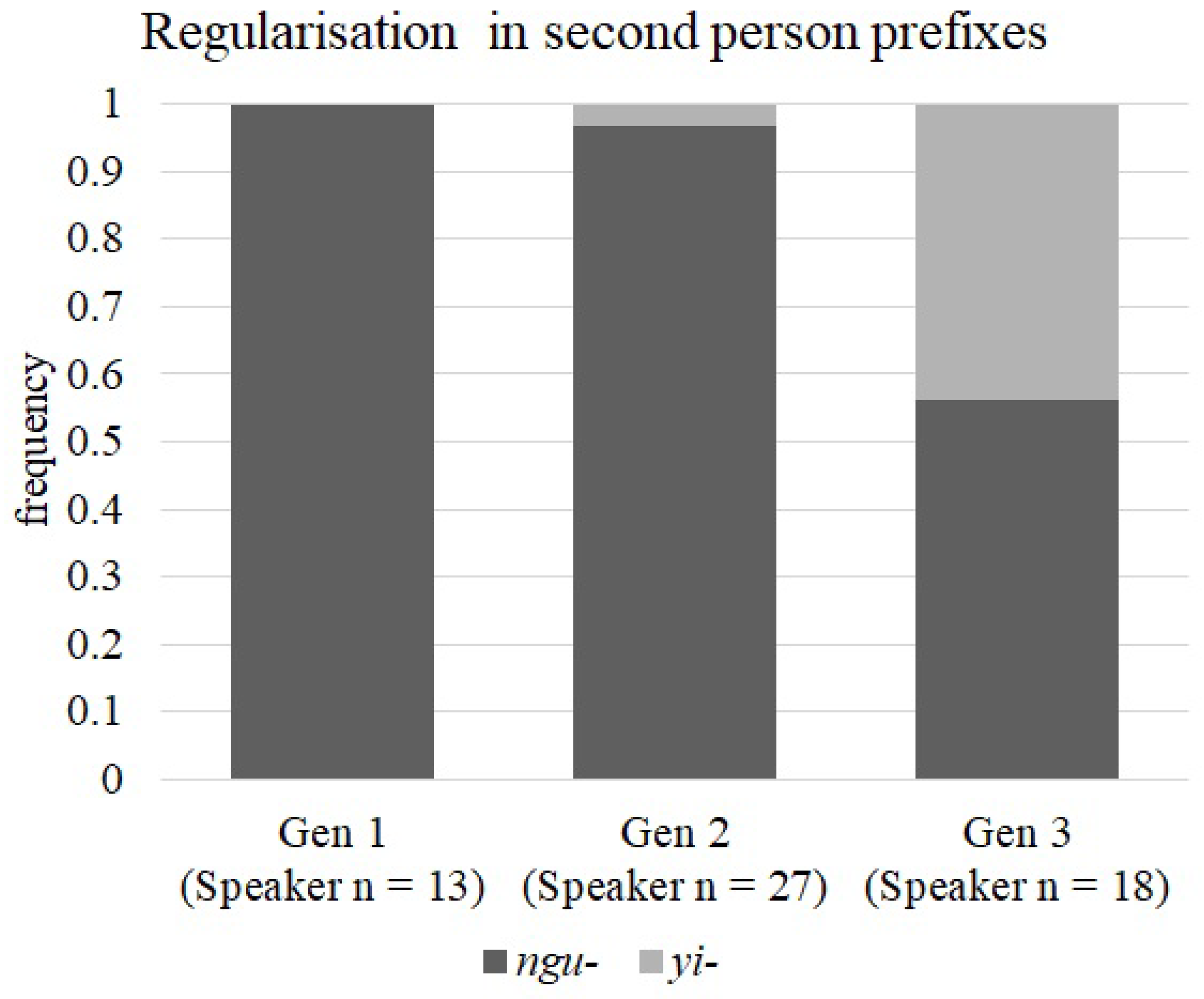

Figure 3 plots the second person non-singular prefix forms in the BKC over three generations: Gen 1: 1907–1944, Gen 2: 1945–1976 and Gen 3: 1977–2010. The total number of speakers represented here is 58, as 40 speakers had no tokens of the non-singular/minimal second person (as either subject or object) in their dataset and so were omitted from this analysis. This chart shows that the majority of the documented regularisation in the BKC is found in Generation 3’s data, while no one in Generation 1 was found to regularise.

Overall, 12 speakers were recorded regularising: 11 from Gen 3 and 1 from Gen 2. This single Gen 2 speaker stands out, not only because he is the only representative of his generation here, but also because he is one of only two men recorded regularising. It is tempting to posit that this is a female-led change; however, this is an artefact of the skewed nature of the dataset: of the 39 members of Gen 3 in the BKC, only 7 are male. Future research specifically focusing on the speech of young Bininj will no doubt provide greater detail as to the leaders of change in this group.

Finally, the regularisation pattern does not extend to the free pronouns. Note that in example (6), the speaker uses the second person direct pronoun

ngudda, which remains unaffected by the changes occurring in the prefixes, as do the other second person free pronouns (

Table 7). This regularisation means that the link between bound and free forms is becoming much more opaque, with a dual root system emerging where free pronouns begin with

ngu- (with the exception of the emphatic singular

yingan) but bound pronouns use the

yi- root.

This deepening divide between bound and free forms is a predicted step in the evolution of pronouns. Australian languages are said to cycle between bound and free pronouns, with one series feeding the other (

Dixon 2002;

Harvey 2003), with Dixon proposing the following evolutionary stages (p. 354):

| Stage I | Bound pronouns are identical to free forms or are a transparent reduction from them; |

| Stage II | Bound pronouns are substantially (or totally) different from free pronouns; |

| Stage III | The old free pronouns have been lost and new ones formed, involving the addition of bound pronominal affixes or clitics to an invariable root. |

Several of the Gunwinyguan and neighbouring non-Pama-Nyungan languages

6 have been identified as being at Stage II of this cycle, including Kunwok (

Dixon 2002, p. 357), but the ongoing decrease in transparency between free and bound second person pronouns in Kunwok potentially indicates a transition to a more advanced step within Stage II.

3.2.2. First Person Clusivity and Number Neutralisation

Regularisation is not the only way that young Bininj are varying Kunwok pronominal prefixes. There is considerable evidence that number marking in first person inclusive prefixes is also undergoing a change. The locus of instability in a min|ua|aug system is in the first person non-singulars, where there is effectively a five-way distinction between non-singular first person forms:

| |

minimal

|

unit augmented |

augmented |

| 1

| nga- | ngane- | ngarri- |

| 12

| ngarr- | kane- | karri- |

A survey of the first person pronominals in the BKC indicated that number distinction and clusivity opposition are potential sites of change. The prefix typically denoting 12ua

kane- is particularly sensitive to neutralisation, most likely because it is so uncommon. Of 2203 tokens of first person plural prefixes, only 17 tokens were

kane-, and all of these were produced by speakers born before 1973 (

Table 8).

The data suggest that

kane- is obsolete for young Bininj—a trend that is further supported by the fact that the corresponding 12ua free oblique pronoun

karrewoneng is not attested at all in the BKC. The absence of both 12ua pronominals points towards a general decline in the salience of the unit-augmented inclusive context and raises the question of which direction the unit-augmented inclusive (12ua) is neutralising in; i.e., with the minimal or with the augmented? From my own observations, it is the augmented which is absorbing the 12ua meaning—a not unexpected direction since three would normally be treated as augmented in other persons. The corpus only catches four tokens of

karri- with the inclusive unit-augmented (12ua) meaning, but I often took the opportunity when I was with only two consultants (i.e., only three of us) to ask how I might say “let’s go”, with the response most often being

karri-re. Likewise, when I was with three Bininj and they decided to leave, the most common form was

karri-re. The resulting paradigm shape as a consequence of the collapsing between

karri- and

kane- is illustrated in

Table 9. Note that the loss of the 12ua distinction means that there is no need to continue with the min|ua|aug analysis:

The neutralisation of 12ua is also found in the transitive prefixes, such that 12ua > 3nsg often syncretises in form with 1a > 3nsg, 12m > 3nsg or 12a > 3nsg. In examples (12) and (13), the speakers provide two different pronominal forms to the same 12ua > 3du elicitation task: the first syncretising 12ua > 3du with the canonical 1a > 3du form ((ng)arrbenbene-) and the second syncretising with the canonical 12a > 3du form (karrbenbene-):

| (12) | Ngalkodjok | ngalbangardi | ngarrbenbene-kadjun |

| | SKIN.NAME | SKIN.NAME | 12ua>3du-follow.NP |

| | “Ngalkodjok albangardi and I followed them (two)” |

| | BKC_Marley_Conrad_prns |

| (13) | Nuk | ngurri-bengkan | karribenbene-nang | ngaye | wurdurd | boken |

| | INTERJ | 2a-remember.NP | 12ua>3du-see.PP | 1sg.DIR | children | two |

| | “Maybe, do you remember when we saw those two kids?” |

| | BKC_Marley_Enosh |

As speakers have neutralised 12ua in different directions, there is some variety as to the direction of neutralisation in individual speakers’ paradigms.

Table 10 aggregates the 1 > 3 transitive forms attested by Generation 3 speakers. Not only is

kane- and its anticipated accompanying transitive forms (

kaneben-/

kanebenbene-) not attested, but there is neutralisation across clusivity boundaries, which further muddies semantic distinctions between first persons. As such, 12ua > 3pl is usually realised as either

(ng)arrben- or

karrben-, and

(ng)arrben- could mean either 1a > 3pl, 12m > 3pl or 12a > 3pl:

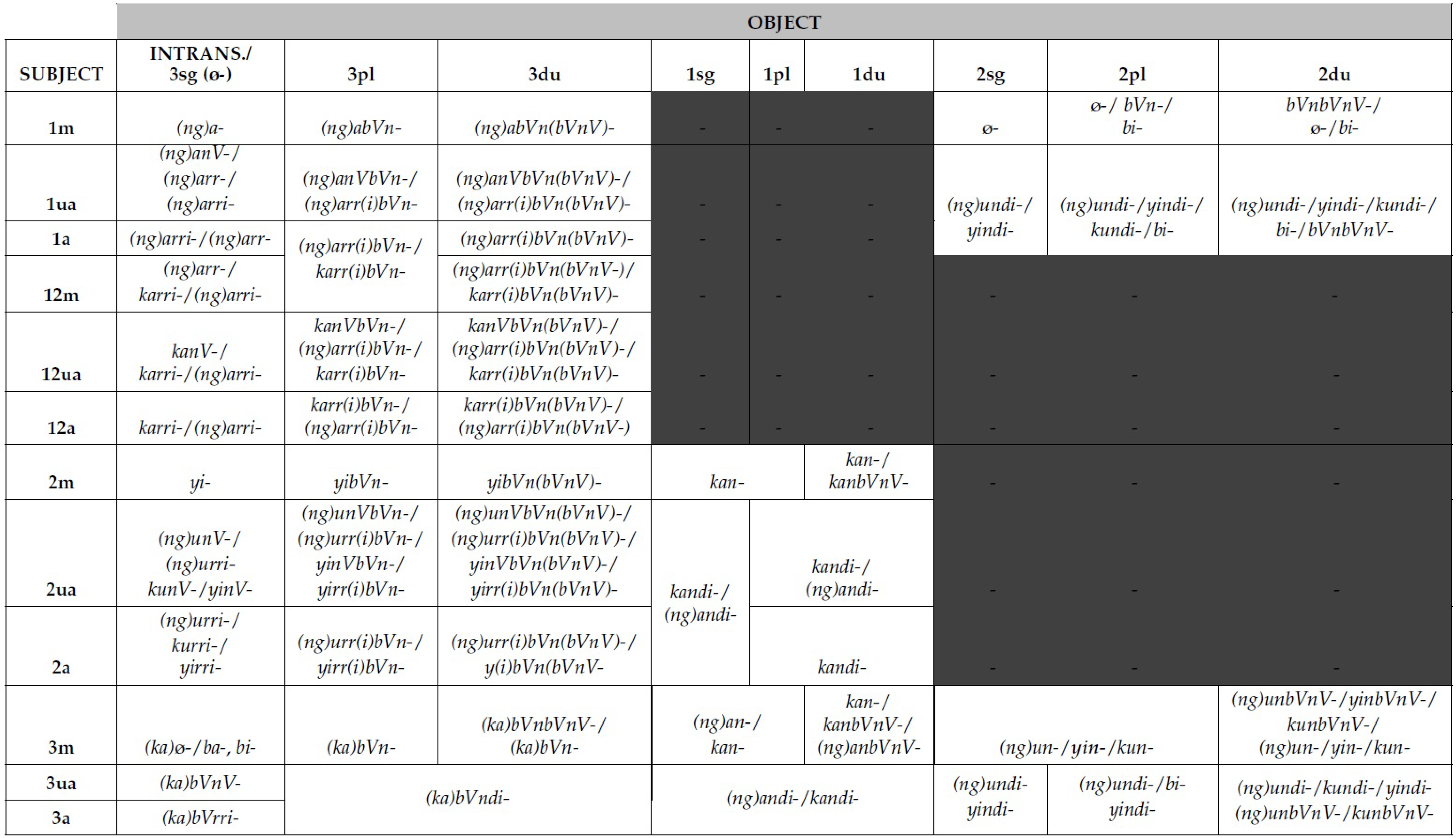

An outcome of this variation is numerous pronominal paradigms in circulation at once in the community. Not only are regularisation and neutralisation occurring, but there are also regional differences in pronominal prefix vowels. This is in addition to the initial-engma deletion and intraspeaker variation (as seen in

Table 10) in regularisation, neutralisation and engma deletion. This results in an astounding number of possible combinations and consequently paradigm shapes.

7 Table 11 combines into a single matrix all the attested forms in the BKC. Here, the initial engma variable is noted in brackets, while the regionally circumscribed vowels (e.g.,

bene-/

bani-/

bini- for 3ua) are replaced with “V”. In cases where two (or more) adjacent pronominal functions have the same form(s) (e.g., 2m > 1sg and 2m > 1pl (

kan-), the cells have been collapsed into a single cell to indicate syncretism. In many cells, there is variation in form and so multiple prefixes are included (e.g., 1m > 2du =

bVnbVnV-/ø-/

bi-). Finally, there are instances om wjocj the same form appears in multiple cells that are not necessarily adjacent to one another or in combination with the same variants.

BVnbVnV-, for example, has at least four semantically distinct functions—3m > 3du, 1m > 2du, 1ua > 2du, and 1a > 2du—but it does not co-occur with the same variants across these functions. In short, massive variation is presented, not only in the form and function of pronominals but also in the syncretism, all of which allows for multiple concurrent pronominal paradigms to coexist in the community—a situation that I call paradigmatic pluralism.

The obvious question that arises here is how this considerable semantic variation in the pronominal prefixes affects comprehension. In many instances of ambiguity, person reference markers external to the verbal complex, such as free pronouns, skin names

8 and kin terms, providing Bininj with the option of specification when necessary. In example (14), the speaker uses free pronouns (

ngarrewoneng and

ngaye) to clarify number and clusivity, which are unspecified in the prefix

ngandi-:

| (14) | Ngandi-bukkani | ngarrewoneng | Ngalwamud | dja | ngaye |

| | 3nm>1nsg-show.PI | 1uaOBL | FE-skin.name | CONJ | 1sg.DIR |

| | “They used to show us two, Ngalwamud and me.” |

| | Garde_Mark_on_Rock |

Although Bininj do clarify in this manner, ambiguous person reference may in fact be preferred.

Garde (

2013, p. 1) posits that there is a high tolerance for and even an expectation of vague and allusory person reference on the basis that “under-specification and circumspect reference” are culturally appropriate discourse norms.

Heath (

1991) also argued that there are sociocultural motivations for ambiguous person and number marking in the pronominal paradigm, citing pragmatic value in assigning irregular forms, particularly in first and second person combinations. In his view, the opacity of the 1

2 pronouns affords speakers a means to navigate delicate or taboo communicative scenarios without contravening social and cultural norms. Thus, imperatives, bad news or deference can all be respectfully signalled by playing down the addressee–speaker relationship by omission, substitution or skewing pronominal forms. As he puts it, “such irregular and problematic combinations are more, not less, highly valued than regularised alternatives would be; the latter would make life easier for grammarians, but more difficult for flesh-and-blood native speakers engaged in actual communicative acts” (

Heath 1991, p. 86).

While this is a very attractive explanation, there is one rather large stumbling block. If person obfuscation were solely pragmatically motivated, we would expect parallel syncretism in the free pronouns (e.g.,

ngudda,

ngudangke or

ngudberre), which has not been found to occur (yet). A study of syncretism in Dalabon (

Evans et al. 2001) revealed similar patterns of syncretism and, although syncretisms in Dalabon were historically likely to be pragmatically motivated, this is now a morphological concern as the patterns are grammaticalised to specific areas of the transitive pronominal paradigm. Thus, what may have begun as a fairly ordered process has became less transparent over time, with the directionality of the syncretism remaining similar but the rules of referral becoming inconsistent between speakers.

3.3. Borrowing

Buffalo traders came to the East Alligator River region in the 1870s, marking the introduction of English (or at least pidgin English) to the country of Gaagudju, Ngaduk, Amurdak, Giimbiyu and Kunwok (Kundjeyhmi) languages. Contact with Kriol is much more recent. Generally associated with the Kimberleys, WA and the Katherine and Roper River regions of the NT, Kriol is the second largest language in the NT after English, with around 20,000 speakers (

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016). It has been expanding in range (

Dickson 2016) and is now the primary language in southern Arnhem Land and the neighbouring Roper River area, as many of the traditional languages of the region, such as Jawoyn, Dalabon, Rembarrnga, Ngalakgan, Wubuy, Marra, Mangarrayi and Alawa, are no longer spoken or have very few fluent speakers left (

Battin et al. 2020).

At a glance, English and Kriol loanwords in Kunwok appear to be on the rise. The BKC was surveyed for instances of loanwords which were then cross-tabulated with the speaker’s date of birth. Note that while there was an occasional word from languages other than English and Kriol (e.g., Mawng), these were far too few in number to investigate further. Loanword counts can be measured in two ways: first, by the raw number of tokens that are encountered in the dataset, and second, by counting the number of distinct loanwords. For instance, the most frequently attested loanword,

muddika, “car”, occurs 78 times in the corpus but is only one of a total of 816 English/Kriol loans attested. In terms of the proportion of borrowing, Generation 3 (1977–2010) ranked significantly higher than the generations that preceded them (15% of their data were loanwords), but varied very little from Gen 2 in terms of the number of loaned items (469 individual loan words vs. 442) (

Table 12):

The majority of loans are nouns accompanying imported cultural concepts and artefacts, such as “car” (

muddika) and “cat” (

budjiked). The earliest loans from English have often been fully phonologically incorporated into Kunwok (“pussycat” →

budjiket), but this process is far from predictable or systematic, as

Poplack (

2018) has established in her work on French–English contact effects in Canada. For instance, the word “mission”,

mishin, stubbornly retains its sibilant in all instances attested in the BKC, despite being a common loanword in the early days of contact, while the /s/ in “pussycat” is faithfully transformed into the palatal stop /c/ (〈dj〉). Additionally, not all loanwords were directly imported from English but came via a neighbouring language. This is particularly true of Makassan loans, many of which entered Kunwok via the Iwaidjan languages (

Evans 1992). Some of the loans can be considered “gratuitous” (

Haspelmath 2009) in that such loans are synonymous with already existing Kunwok words. For example, the verb “to help” is the most frequently borrowed loan verb (either from English “help” or Kriol

helbam) in the corpus (n = 17), outranking the Kunwok verb of the same meaning

bidyikarrme (n = 9). In examples (15) and (16), two speakers are retelling the same story (based on an elicitation tool by

O’Shannessy 2004) but employ different ways of saying “help”. The first uses the Kunwok

bidyikarrme, while the second uses the English “help” accompanied by the Kunwok verb

yime, “do/say”, to form a periphrastic verbal construction.

| (15) | Nani | djarrang | karri-bidyikarrme

|

| | MA.DEM | horse | 12a-help.NP |

| | “Let’s help the horse” |

| | BKC_Marley_Alexandria |

| (16) | Then | ngalbadjan | nakornkumo | help | bini-yimeng

|

| | then | mother | father | help | 3ua-do.PP |

| | “Then the mother and the father helped him” |

| | BKC_Marley_Kiara_2 |

This second strategy is the preferred manner of incorporating loan verbs in Australian languages, particularly in non-Pama-Nyungan languages (

Wohlgemuth 2009). It typically involves an uninflected loan verb (the coverb) carrying the semantic weight of the complex predicate accompanied by a recipient language verb (the light verb) which has been semantically bleached but hosts the inflectional morphology (

McGregor 2013;

Meakins and O’Shannessy 2012;

Schultze-Berndt 2000). This loan verb integration strategy is one of three possible ways to borrow verbs. The most common cross-linguistically is by direct insertion, whereby a loan verb is brought into the recipient language with no morphosyntactic accommodation (

Wohlgemuth 2009) (example (17)). The second is the coverb strategy (example (18)). The third method, which is also attested in Kunwok, is by indirect insertion, in which the donor verb is affixed with some sort of verbalising element to nativise it (example (19)).

| (17) | Direct insertion example in German (from English loan) |

| | Wir | klick-en |

| | 1pl.NOM | click-PRES.1pl |

| | “We click” | |

| (18) | Coverb insertion example in Italian (from English loan) |

| | Fai | clic | ed | ascoltare |

| | do.2sg.PRES | click | and | listen.INF |

| | “Click and listen” |

| (19) | Indirect insertion example in Greek (from English loan) |

| | Klik-ár-o |

| | click-VBSR-1sg |

| | “I click” |

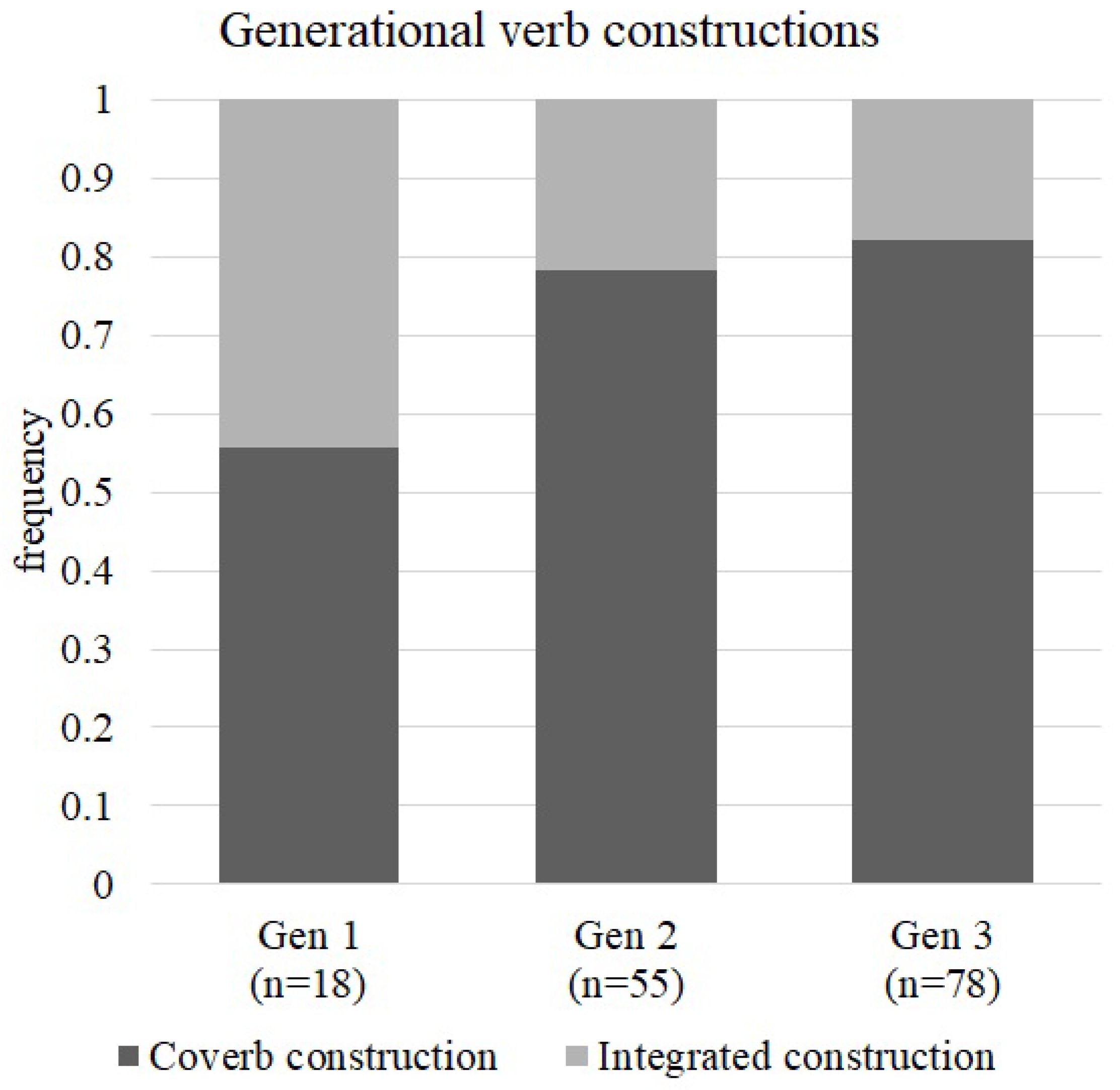

Kunwok speakers use two of these strategies to integrate borrowed verbs—coverb constructions and indirect insertion—with younger speakers showing a stronger preference for the coverb strategy than the previous generations (see

Figure 4).

Wohlgemuth’s (

2009, p. 147) global survey of loan verbs indicated that using multiple strategies to accommodate verbs is not uncommon (26.7% of his sample, n = 352), and that in Australia, the two preferred methods are coverb constructions and indirect insertion. As a regular feature in Australian languages, coverb constructions frequently feature as the primary verbal structure: 90% of Gurindji (Pama-Nyungan) verbal structures, for example, are coverb constructions (

Bowern 2014, p. 278). Kunwok, however, only uses this construction for loans, and in fact, coverb constructions are heavily implicated in contact scenarios, with the phenomenon in Australia particularly concentrated near the Pama-Nyungan—non-Pama-Nyungan border (

Bowern 2014). Of the Gunwinyguan languages, only Kunbarlang employs coverbs for native elements (

Kapitonov 2019), indicating that coverbs are not an inherent feature of Gunwinyguan languages but rather a consequence of contact.

9There are only three attested light verbs in Kunwok, giving it one of the smallest light verb inventories documented in an Australian language (

Bowern 2014). The most common verb used as a light verb is “do/say”,

yime, with 175 of 201 (87%) coverb constructions in the BKC employing it. The other two verbs, “go”,

re, and “carry/take”,

kan, are far less frequent, with

re attested 24 times (12%) and

kan only twice, both times by the same speaker.

Loan verbs that are inserted indirectly are suffixed with the verbaliser

-(h)me10 (examples (20) and (21)) and will inflect according to the paradigm for verbs ending in

-me. There were far fewer tokens and examples of verbs borrowed this way, and they tend to be verbs that were borrowed in the early days of contact, such as “buy” and “work” (examples (20) and (21)). Nonce examples of indirectly incorporated verbs were provided by a couple of speakers during an interview on the topic (examples (22) and (23)). Note that these examples use Kriol verbs, identifiable by the Kriol transitive suffix

-im (examples (22) and (23)).

| (20) | English: ‘buy’ + -hme |

| | Baleh | kore | bene-baya-hmeng? |

| | Where | LOC | 3ua>3sg-buy-VBSR.PP |

| | “Where did they buy it from?” |

| | PARADISEC_CC01-000-BWALKCOMMS0_S8 |

| (21) | English: ‘work’ + -hme |

| | Dja | kunu | bedman-ni | stockman | barri-woki-hmi | kunu |

| | CONJ | in.that.way | 3a-PI | stockman | 3a-work-VBSR.PI | in.that.way |

| | “So those stockmen used to work like that” |

| | BKC_Garde_Bokmarnde_Nlo |

| (22) | Kriol: daunlodim ‘download’ + -me |

| | Nga-dawnlodim-meng | korroko |

| | 1m-download-VBSR.PP | before |

| | “I already downloaded it” |

| | Marley_fieldnotes20180826 |

| (23) | Kriol: bilimab ‘fill’ + -me |

| | Yi-bilimab-men |

| | 2m>3sg-fill.up-VBSR.IMP |

| | “Fill it up!” |

| | Marley_fieldnotes20170426 |

The sample size presented here is too small to draw any solid conclusions about changes in the way loan verbs are integrated into Kunwok, but of the 194 tokens of coverb constructions in the corpus, 57% were produced by Gen 3 (

Figure 5). This provides a preliminary indication that coverb constructions are on the rise in Kunwok.

A similar rise in the adoption of complex predicates has also been observed in Murrinhpatha, where

Mansfield (

2014, p. 420) noted an increase in coverb constructions with English loan verbs, especially in the speech of young men. Murrinhpatha, like Kunwok, is a highly synthetic non-Pama-Nyungan language, with children still learning it as a first language, but the documented rise of coverbs in Murrinhpatha differs to that observed in Kunwok in that there are a number of Murrinhpatha verbs (albeit limited) that ordinarily take the form of the coverb plus light verb construction. Additionally, Murrinhpatha very rarely incorporates borrowed verbs into the synthetic verb complex (Mansfield found only a single example) on the basis that the other verbal elements and verb roots are too rigid and opaque to allow for the insertion of novel borrowed forms.

Comparative and historical analyses of the verbal morphology of Australian languages have demonstrated that verbs in Northern Australia follow a cyclical evolutionary path, transforming from synthetic to phrasal structures and eventually back again (

Dixon 2002;

Schultze-Berndt 2003). Grammaticalisation and phonological erosion generally underlie this process; however, contact may also play a role in some cases. With respect to Murrinhpatha,

Mansfield (

2016, p. 356) argues that contact has facilitated a turn in the cycle. The same hypothesis is not advanced for the neighbouring Daly River language Ngan’gityemerri. Ngan’gityemerri has undergone some radical morphosyntatic restructuring to its verbal complex in the past century, which

Reid (

2003, p. 120) argues is unrelated to contact with English. In Kunwok, the rise of the coverb in young people’s speech may signal a similar incipient turn of the evolutionary wheel, but whether this is as a direct response to English/Kriol contact (as with Murrinhpatha) or a coincidence (as with Ngan’gityemerri) requires further investigation.