A Variationist Study of Subject Pronoun Expression in Medellín, Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pronombrismo

2.1. Previous Treatments of the Effect of the Verb on SPE

2.1.1. Verb Type

- cognitive verbs (pensar ‘think,’ saber ‘know,’ creer ‘believe,’ etc.)

- perceptive verbs (oler ‘smell,’ ver ‘see,’ sentir ‘feel,’ etc.)

- enunciative verbs (afirmar ‘state;’ decir ‘say, tell;’ comentar ‘comment;’ hablar ‘speak;’ etc.)

- desiderative and manipulative verbs (desear ‘wish,’ ordenar ‘command,’ querer ‘want,’ pedir ‘ask,’ etc.).

- other verbs (i.e., verbs that do not correspond to the above categories).

2.1.2. Lexical Content of the Verb

- Mental activity verbs, which require psychological effort from the speaker (acordarse ‘remember,’ analizar ‘analyze,’ aprender ‘learn,’ decidir ‘decide,’ desear ‘wish,’ escoger ‘select,’ imaginar ‘imagine,’ intentar ‘attempt,’ etc.).

- Estimative verbs, which imply the speaker’s opinion or judgment (admirar ‘admire,’ considerar ‘consider,’ creer ‘believe,’ opinar ‘believe,’ pensar ‘think,’ respetar ‘respect,’ suponer ‘suppose,’ etc.).

- Stative verbs, which escape all dynamic processes and are not affiliated with activities that the speaker undertakes, either mentally or physically (crecer ‘grow,’ criarse ‘be raised,’ enamorarse ‘fall in love,’ estar ‘be,’ llamarse ‘be called,’ ser ‘be,’ tener ‘have,’ valer ‘be worth,’ vivir ‘live,’ etc.).

- External activity verbs, which imply physical, mental, or behavioral activity or which derive from movement, or an ongoing situation (acabar ‘finish;’ avanzar ‘advance;’ cambiar ‘change;’ comprar ‘buy;’ conseguir ‘obtain, get;’ criar ‘raise;’ dar ‘give;’ decir ‘say, tell;’ entrar ‘enter;’ escribir ‘write;’ hablar ‘speak;’ hacer ‘do, make;’ ir ‘go;’ llegar ‘arrive, come;’ mirar ‘watch;’ salir ‘leave;’ ver ‘see;’ etc.).

2.1.3. Psychological vs. Other Verbs

2.1.4. Lexical Frequency

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Speech Community, the Corpus, and the Dataset

3.2. Research Questions and Hypothesis

- (a)

- How are overt and null pronominal subjects distributed in the Spanish of Medellín, and how does this variety compare with other varieties of Spanish in terms of subject pronoun expression?

- (b)

- How do social predictors condition SPE in Medellín, and how do their effects in this speech community compare to those in other communities?

- (c)

- Is the internal conditioning on subject pronoun expression in Medellín Spanish similar to what is found throughout the Hispanic World? Do all verbs within the same category similarly condition SPE?

3.3. Predictors Explored

3.3.1. Social Predictors

3.3.2. Linguistic Predictors

| 1. | Por la timidez que yo mantenía, yo sudaba hasta frío para hablarle a ella; es que yo era una persona muy tímida. (H21-5, 489) |

| ‘Because of the shyness that I used to maintain, I had a cold sweat even as I talked to her; it’s because I was a very shy person.’ | |

| 2. | Ø Creo, Ø no conozco mucho el proyecto, y en lo que Ø conozco, es como el despelote que ha causado en las vías. Pero Ø no sé, Ø no conozco pues tampoco. Ø Sé que es una cosa similar al Transmilenio de Bogotá, pero Ø no estoy tampoco como muy informada (M13-5, 283). |

| ‘I think I don’t know much about the project, and in what I know, it’s like the mess that it has caused on the roads. But I don’t know, and I’m not familiar with it either. I know that it is something similar to Bogota’s Transmilenio, but I’m not that well informed either.’ |

| 3. | Pues ∅ llevo una vida muy así tranquila. Sí, pues, ∅ me divierto por ahí un rato. (M21-1, 267) ‘Well, I lead such a quiet life. Yes, so I enjoy myself around a little bit.’ |

| 4. | A ver. El sitio donde yo vivía se llama el barrio Restrepo. (M23-3, 42) |

| ‘Let’s see. The place where I lived is called the Restrepo quarter.’ | |

| 5. | En la casa, lo que más hace uno, pues, uno llega del trabajo es a descansar. (H32-1, 129) |

| ‘At home, what one does more, so, one returns from work only to rest.’ |

3.4. The Envelope of Variation and the Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Distribution of Variable Pronominal Subjects and Predictor Model

4.2. Social Conditioning

4.3. Internal Conditioning

4.3.1. Subject-Related Conditioning

| 6. | Entonces yo asumí toda la responsabilidad de mi casa. Cuando Ø empecé a trabajar, pues ya uno con su platica, pues entonces uno ya con un ambiente distinto, uno como padre en la casa, entonces uno se sentía pues que Ø era pues como muy grande, ¿cierto? Entonces, en ese tiempo, siempre Ø me tomaba mis guaros. (H33-3, 318-323) |

| ‘So, I assumed all the responsibility of my household. When I started to work, then one with one’s money, so then one is in a different environment, one as a parent in the household; thus, one felt, well that … was something very big, right? So, at that time, I would always drink my shots.’ |

4.3.2. Clause-Related Conditioning: Discourse Type

| 7. | No, ella es bien, ∅ es muy alegre, ella es chévere. Ella tiene raticos que, pues ∅ es aburrida, y hay ratos que ∅ es alegre. Siempre ∅ ha sido pues, buena mujer. (H11-4, 214) |

| ‘No, she is well (good), she is very happy, she is awesome. She’s got her moments, well she’s boring, and she’s got times when she’s happy. She’s always been well, a good woman.” |

| 8. | Pues la rutina mía como diaria, pues ∅ me levanto, o sea, todos los días ∅ tengo clase, si no es de seis es de ocho, ∅ me levanto, pues ∅ me baño, normal, ∅ me voy para la universidad. (M03-5, 349-354) |

| ‘Well, my daily routine, so I get up, well, every day I have class; if it’s not at six, it’s at eight. I get up, then I bathe; normally, I go to the university.’ |

4.3.3. Verb-Related Conditioning

- (a)

- verbs that favor overt pronominal subjects (creer ‘think, believe;’ pensar ‘think;’ decir ‘say, tell;’ vivir ‘live;’ trabajar ‘work;’ etc.)

- (b)

- verbs with a neutral effect (tener ‘have,’ ir ‘go,’ estar ‘be,’ poder ‘can,’ quedar ‘stay,’ and irse ‘leave’), and

- (c)

- verbs that favor null subjects (poner ‘put;’ imaginarse ‘imagine;’ volver ‘return;’ mirar ‘look;’ hablar ‘speak, talk;’ venir ‘come;’ llevar ‘take, carry’).

- Saber ‘know’ has a neutral effect in Medellín and the New York Colombian community and favors overt subjects in Barranquilla but favors null subjects in Xalapa, Mexico.

- Tener ‘have’ has a neutral effect in Medellín and promotes overt subjects in Barranquilla but favors null subjects in Xalapa and New York, respectively.

- Hacer ‘make, do’ despite favoring null subjects in Medellín and Xalapa, has the opposite effect in the New York Colombian community and has a neutral effect in Barranquilla.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Factor | Prob. | % Overt | N | % Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creer ‘believe’ | .882 | 72.3% | 155 | 3.4% |

| Pensar ‘think’ | .747 | 50.0% | 84 | 1.8% |

| Decir ‘say, tell’ | .737 | 46.7% | 195 | 4.2% |

| Vivir ‘live’ | .728 | 46.6% | 103 | 2.2% |

| Trabajar ‘work’ | .723 | 48.9% | 47 | 1.0% |

| Comprar ‘buy’ | .646 | 40.7% | 27 | 0.6% |

| Recordar ‘remember’ | .627 | 40.0% | 20 | 0.4% |

| Ser ‘be’ | .625 | 33.4% | 341 | 7.4% |

| Llegar ‘arrive’ | .618 | 34.4% | 61 | 1.3% |

| Acordarse ‘remember’ | .618 | 37.5% | 24 | 0.5% |

| Meter ‘stick’ | .617 | 38.1% | 21 | 0.5% |

| Tratar ‘try’ | .615 | 38.9% | 18 | 0.4% |

| Conocer ‘know’ | .602 | 32.1% | 84 | 1.8% |

| Querer ‘want’ | .587 | 30.8% | 78 | 1.7% |

| Saber ‘know’ | .572 | 28.7% | 216 | 4.7% |

| Ver ‘see’ | .566 | 28.2% | 170 | 3.7% |

| Levantarse ‘get up’ | .55 | 28.6% | 28 | 0.6% |

| Salir ‘exit, leave’ | .533 | 25.8% | 66 | 1.4% |

| Tener ‘have’ | .510 | 23.5% | 425 | 9.2% |

| Ir ‘go’ | .508 | 23.5% | 132 | 2.9% |

| Jugar ‘play’ | .507 | 23.8% | 21 | 0.5% |

| Encontrar(se) ‘find, meet’ | .507 | 23.8% | 21 | 0.5% |

| Estar ‘be’ | .506 | 23.3% | 219 | 4.7% |

| Coger ‘take’ | .504 | 23.5% | 17 | 0.4% |

| Poder ‘can’ | .504 | 23.1% | 108 | 2.3% |

| Quedar ‘stay’ | .504 | 23.3% | 43 | 0.9% |

| Ayudarse ‘help’ | .484 | 21.1% | 19 | 0.4% |

| Irse ‘leave’ | .479 | 21.1% | 71 | 1.5% |

| Sentir ‘feel’ | .466 | 20.0% | 60 | 1.3% |

| Pasar ‘pass’ | .465 | 19.2% | 26 | 0.6% |

| Llevar ‘take, carry’ | .458 | 18.8% | 32 | 0.7% |

| Empezar ‘start’ | .458 | 17.6% | 17 | 0.4% |

| Casarse ‘marry’ | .449 | 16.7% | 18 | 0.4% |

| Necesitar ‘need’ | .448 | 16.7% | 18 | 0.4% |

| Reunir(se) ‘meet’ | .440 | 15.8% | 19 | 0.4% |

| Hablar ‘speak, talk’ | .432 | 18.1% | 221 | 4.8% |

| Entender ´understand’ | .431 | 15.0% | 20 | 0.4% |

| Saludar ‘greet’ | .428 | 13.3% | 15 | 0.3% |

| Bajar ‘get down’ | .410 | 11.8% | 17 | 0.4% |

| Venir ‘come’ | .407 | 15.1% | 53 | 1.1% |

| Mirar ‘look’ | .402 | 13.9% | 36 | 0.8% |

| Volver ‘return’ | .397 | 12.9% | 31 | 0.7% |

| Imaginarse ‘imagine’ | .375 | 12.5% | 48 | 1.0% |

| Poner ‘put’ | .328 | 7.9% | 38 | 0.8% |

References

- Abreu, Laurel. 2009. Spanish Subject Personal Pronoun Use by Monolinguals, Bilinguals and Second Language Learners. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, Laurel. 2012. Subject Pronoun expression and priming effects among bilingual speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish. In Selected Proceedings of the 14th Hispanic Linguistic Symposium. Edited by Kimberly Geeslin and Manuel Díaz-Campos. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Aijón Oliva, Miguel, and Maria José Serrano. 2010. El hablante en su discurso: Expresión y omisión del sujeto de creo. Oralia 13: 7–38. [Google Scholar]

- Aijón Oliva, Miguel, and Maria José Serrano. 2013. El sujeto posverbal: Función pragmática y cognición en las cláusulas declarativas. Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 114: 309–31. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela. 2015. Variation of Overt and Null Subject Pronouns in the Spanish of Santo Domingo. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho, Rafael Orozco and Naomi Lapidus Shin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade Rodríguez, Ricardo, María Claudia González Rátiva, and David A. Jaramillo. 2008. La representatividad poblacional en el estudio sociolingüístico de Medellín. Lenguaje 38: 527–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Jiménez, Bárbara. 1995. A Sociolinguistic Analysis of a Change in Progress: Pronominal Overtness in Puerto Rican Spanish. Cornell Working Papers in Linguistics 13: 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley, Robert, and Lucinda Pease-Alvarez. 1996. Null and expressed subject pronoun variation in Mexican-descent children’s Spanish. In Sociolinguistic Variation: Data, Theory, and Analysis. Edited by Jennifer Arnold, Renee Blake and Brad Davidson. Stanford: Center for the Study of Language and Information, pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley, Robert, and Lucinda Pease-Alvarez. 1997. Null Pronoun variation in Mexican-descent children’s narrative discourse. Language Variation and Change 9: 349–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrenechea, Ana María, and Alicia Alonso. 1973. Los pronombres personales sujetos en el español de Buenos Aires. In Studia Iberica: Festschrift für Hans Flasche. Edited by Körner Karl-Hermann and Klaus Rühl. Bern and München: Francke, pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bentivoglio, Paola. 1980. Why Canto and Not yo Canto? The Problem of First-Person Subject Pronoun in Spoken Venezuelan Spanish. Master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bentivoglio, Paola. 1987. Los Sujetos Pronominales de Primera Persona en el Habla de Caracas. Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, Consejo de Desarrollo Científico y Humanístico. [Google Scholar]

- Botero, Fernando. 1996. Medellín 1890–1950. Historia Urbana y Juego de Intereses. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2001. Phonology and Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2003. Mechanisms of change in grammaticization: The role of frequency. In The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Edited by Richard Janda and Brian Joseph. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 624–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2006. From usage to grammar: The mind’s response to repetition. Language 82: 711–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, John Haiman, and Sandra Thompson. 1997. Essays on Language Function and Language Type: Dedicated to T. Givon. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, and David Eddington. 2006. A usage-based approach to Spanish verbs of ‘becoming’. Language 82: 323–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan, and Rena Torres Cacoullos. 2008. Phonological and grammatical variation in exemplar models. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 1: 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Richard. 1992. Pronominal and Null Subject Variation in Spanish: Constraints, Dialects, and Functional Compensation. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Richard. 1993. Ambiguous agreement, functional compensation, and non-specific tú in the Spanish of San Juan, Puerto Rico and Madrid, Spain. Language Variation and Change 5: 305–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Richard. 1994. Switch reference, verb class and priming in a variable syntax. In Papers from the Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society: Parasession on Variationin Linguistic Theory. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, vol. 30, pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Richard. 1995. The scope and limits of switch reference as a constraint on pronominal subject expression. Hispanic Linguistics 6: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Richard. 1996. A community-based test of a linguistic hypothesis. Language in Society 25: 61–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Richard. 1998. A variable syntax of speech, gesture, and sound effect: Direct quotations in Spanish. Language Variation and Change 10: 43–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Richard, and Nydia Flores-Ferrán. 2004. Perseveration of subject expression across regional dialects of Spanish. Spanish in Context 1: 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Ana M., and Ryan M. Bessett. 2015. Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish in Contact with Portuguese. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho, Rafael Orozco and Naomi Lapidus Shin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 145–67. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana M., and Michael Child. 2011. Subject Pronoun Expression in a Variety of Spanish in Contact with Portuguese. In Selected Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Jim Michnowicz and Robin Dodsworth. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana M., Rafael Orozco, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. 2015. Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, Luz Estella. 2005. El parlache: Resultados de una investigación lexicográfica. Forma y Función 18: 71–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Álvaro. 2014. Ser más pro o menos pro: Variación en la expresión de sujeto pronominal en el castellano limeño. Lingüística 30: 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Jack K. 2009. Sociolinguistic Theory. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, Jenny. 2004. Sex and gender in variationist research. In The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Edited by J. K. Chambers, Peter Trudgill and Natalie Schilling-Estes. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 423–43. [Google Scholar]

- Claes, Jeroen. 2011. ¿Constituyen las Antillas y el Caribe continental una sola zona dialectal? Datos de la variable expresión del sujeto pronominal en San Juan de Puerto Rico y Barranquilla, Colombia. Spanish in Context 8: 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company Company, Concepción, and Julia Pozas Loyo. 2009. Los indefinidos compuestos y los pronombres genéricos-impersonales omme y uno. In Sintaxis Histórica de la Lengua Española. Segunda Parte: La Frase Nominal. Directed by Concepción Company Company. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, Universidad Autónoma de México, pp. 1073–222. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William, and D. Alan Cruse. 2004. Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa, Johan. 2020. Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish-Palenquero Bilinguals: Contact and Second Language Acquisition. Ph.D. dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- de Prada Pérez, Ana. 2009. Subject Expression in Minorcan Spanish: Consequences of Contact with Catalan. Ph.D. dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- de Prada Pérez, Ana. 2015. First Person Singular Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish in Contact with Catalan. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- de Prada Pérez, Ana. 2020. The Interaction of Functional Predictors and the Mechanical Predictor Perseveration in a Variationist Analysis of Caribbean Spanish Heritage Speaker Subject Pronoun Expression. Languages 5: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Prada Pérez, Ana, and Inmaculada Gómez Soler. 2020. The effect of person on the subject expression of Spanish heritage speakers. In Dialects from Tropical Islands: Caribbean Spanish in the United States. Edited by Wilfredo Valentín-Márquez and Melvin González-Rivera. New York: Routledge Publishers, pp. 128–50. [Google Scholar]

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística (DANE). 2019. Resultados del Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda de Colombia. Available online: https://sitios.dane.gov.co/cnpv/#!/vihope_clase (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Enghels, Renata. 2012. Transitivity of Spanish perception verbs: A gradual category? Borealis: An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 2: 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez, Emilia. 1984. El Pronombre Personal Sujeto en la Lengua Española Hablada en Madrid. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. [Google Scholar]

- Erker, Daniel, and Gregory R. Guy. 2012. The role of lexical frequency in syntactic variability: Variable subject personal pronoun expression in Spanish. Language 88: 526–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasold, Ralph. 1990. The Sociolinguistics of Language. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Susana. 2013. Impersonality in Spanish personal pronouns. In Deixis and Pronouns in Romance Languages. Edited by K. Kragh and J. Lindschouw. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Acosta, Diana. 2020. El voseo en Medellín, Colombia: Un rasgo dialectal distintivo de la identidad paisa. Dialectología 24: 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ferrán, Nydia. 2002. A Sociolinguistic Perspective on the Use of Subject Personal Pronouns in Spanish Narratives of Puerto Ricans in New York City. Munich: Lincom-Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ferrán, Nydia. 2004. Spanish subject personal pronoun use in New York City Puerto Ricans: Can we rest the case of English contact? Language Variation and Change 16: 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ferrán, Nydia. 2007a. Los Mexicanos in New Jersey: Pronominal expression and ethnolinguistic aspects. In Selected Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Jonathan Holmquist, Augusto Lorenzino and Lotfi Sayahi. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ferrán, Nydia. 2007b. A bend in the road: Subject personal pronoun expression in Spanish after 30 years of sociolinguistic research. Language and Linguistics Compass 1: 624–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ferrán, Nydia. 2009. Are you referring to me? The variable use of UNO and YO in oral discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 41: 1810–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Matthew. 2019. La Expresión de la Posesión Nominal en Medellín, Colombia. Master’s thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Miguel, José. 2005. Aproximación empírica a la interacción de los verbos y esquemas construccionales, ejemplificada con los verbos de construcción. ELUA 19: 169–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Adele E. 2006. Constructions at Work: The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Torrego, Leonardo. 1992. La Impersonalidad Gramatical. Madrid: Arcos Libros. [Google Scholar]

- González-Rátiva, María Claudia (Coord.). 2008. Corpus Sociolingüístico de Medellín [Electronic Portal]. Medellín: Facultad de Comunicaciones, Universidad de Antioquia, Colombia. Available online: http://comunicaciones.udea.edu.co/corpuslinguistico/ (accessed on 22 August 2017).

- Hochberg, Judith. 1986. Functional compensation for /s/ deletion in Puerto Rican Spanish. Language 62: 609–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Paul, and Sandra Thompson. 1980. Transitivity in grammar and discourse. Language 56: 252–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Paul, and Elizabeth Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, Luz Marcela. 2001. La variable Expresión del Sujeto en el Español de los Colombianos y Colombo-Americanos Residentes en el Condado de Miami-Dade. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, Luz Marcela. 2005a. El uso de tú, usted y uno en el español de los colombianos y colomboamericanos. In Contactos y Contextos Lingüísticos: El Español en los Estados Unidos y en Contacto con otras Lenguas. Edited by Luis Ortiz López and Manel Lacorte. Madrid and Frankfurt: Iberoamericana/Vervuert, pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado, Luz Marcela. 2005b. Condicionamientos sintáctico-semánticos en la expresión del sujeto en el español colombiano. Hispania 88: 335–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, Luz Marcela, and Ivan Ortega-Santos. 2019. On the use of uno in Colombian Spanish: The role of transitivity. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 12: 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra, Yolanda, and Pedro Martín Butragueño. 2015. Subject Pronoun Expression in Oral Mexican Spanish. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho, Rafael Orozco and Naomi Lapidus Shin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 1972. Sociolinguistic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leroux, Martine, and Lidia-Gabriela Jarmasz. 2005. A study about nothing: Null subjects as a diagnostic of the convergence between English and French. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Limerick, Philip P. 2018. Subject Expression in a Southeastern U.S. Mexican Community. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Linford, Bret, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. 2013. Lexical Frequency Effects on L2 Spanish Subject Pronoun Expression. In Selected Proceedings of the 16th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Jennifer Cabrelli Amaro, Gillian Lord, Ana de Prada Pérez and Jessi Elana Aaron. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 175–89. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Sanz, Cristina. 2011. Null and Overt Subjects in a Variable System: The Case of Dominican Spanish. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff, Miriam. 2009. Replication, transfer, and calquing: Using variation as a tool in the study of language contact. Language Variation and Change 21: 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michnowicz, Jim. 2015. Subject Pronoun Expression in Contact with Maya in Yucatan Spanish. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho, Rafael Orozco and Naomi Lapidus Shin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 103–22. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, Mónica. 2014. “Vos sos paisa”: A study of address forms in Medellín, Colombia. In New Directions in Hispanic Linguistics. Edited by Rafael Orozco. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Giraldo, José Joaquín. 1967. Sobre el voseo en Colombia. Thesaurus 22: 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Giraldo, José Joaquín. 1982. El español de Colombia. Thesaurus 37: 23–92. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Amparo. 1980. La expresión de sujeto pronominal de primera persona en el español de Puerto Rico. Boletín de la Academia Puertorriqueña de la Lengua Española 8: 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2007. Social Constraints on the Expression of Futurity in Spanish-Speaking Urban Communities. In Selected Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Jonathan Holmquist, Augusto Lorenzino and Lotfi Sayahi. Somerville: Cascadilla, pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2009. La influencia de factores sociales en la expresión del posesivo. Lingüística 22: 25–60. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2015a. Pronominal variation in Costeño Spanish. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho, Rafael Orozco and Naomi Lapidus Shin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2015b. Castilian in New York City: What can we learn from the future? In New Perspectives on Hispanic Contact Linguistics in the Americas. Edited by Sandro Sessarego and Melvin González-Rivera. Madrid: Iberoamericana, pp. 347–72. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2016. Subject Pronoun Expression in Mexican Spanish: ¿Qué pasa en Xalapa? Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 1: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2018a. Spanish in Colombia and New York City: Language Contact Meets Dialectal Convergence. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2018b. El castellano colombiano en la ciudad de Nueva York: Uso variable de sujetos pronominales. Studies in Lusophone and Hispanic Linguistics 11: 89–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, Rafael. 2019. A New Perspective on Subject Pronoun Expression: The Effects of Lexical Idiosyncrasy. Paper presented at International Conference on Language Variation in Europe (ICLAVE) 10, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 26–28 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael. n.d. La expresión de sujetos pronominales entre centroamericanos en Luisiana. Submitted to Lingüística y Literatura.

- Orozco, Rafael, and Gregory Guy. 2008. El uso variable de los pronombres sujetos: ¿Qué pasa en la costa Caribe colombiana? In Selected Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Maurice Westmoreland and Juan Antonio Thomas. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, Rafael, Catalina Méndez Vallejo, and Lee-Ann Vidal-Covas. 2014. Los efectos condicionantes del verbo en el uso variable de los pronombres personales de sujeto. In Actas del XVII Congreso Internacional de la Asociación de Lingüística y Filología de la América Latina: João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brasil. João Pessoa: Universidade Federal da Paraíba, pp. 2342–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz López, Luis. 2009. Pronombres de sujeto en el español (L2 vs L1) del Caribe. In El Español en Estados Unidos y Otros Contextos de Contactos: Sociolingüística, Ideología y Pedagogía. Edited by Manel Lacorte and Jennifer Lehman. Frankfurt Main: Vervuert, Madrid: Iberoamericana, pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz López, Luis A. 2011. Spanish in contact with Haitian Creole. In The Handbook of Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 418–45. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, and Ana Celia Zentella. 2007. Apuntes preliminares sobre el contacto lingüístico y dialectal en el uso pronominal del español en Nueva York. In Spanish in Contact: Policy, Social and Linguistic Inquiries. Edited by Kim Potowski and Richard Cameron. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 275–95. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, and Ana Celia Zentella. 2012. Spanish in New York: Language Contact, Dialectal Leveling, and Structural Continuity. Oxford: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, Ana Celia Zentella, and David Livert. 2007. Language and dialect contact in Spanish in New York: Toward the formation of a speech community. Language 83: 770–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrehumbert, Janet. 2001. Exemplar dynamics: Word frequency, lenition, and contrast. In Frequency and the Emergence of Linguistic Structure. Edited by Joan Bybee and Paul Hopper. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 137–58. [Google Scholar]

- Posio, Pekka. 2011. Spanish subject pronoun usage and verb semantics revisited: First and second person singular subject pronouns and focusing of attention in spoken Peninsular Spanish. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 777–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posio, Pekka. 2015. Reference range and variability of impersonal constructions with human reference in peninsular spoken Spanish: ‘se’ and the third person plural. Spanish in Context 12: 373–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posio, Pekka. 2018. Properties of Pronominal Subjects. In The Cambridge Handbook of Spanish Linguistics. Edited by Kimberly L. Geeslin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 286–306. [Google Scholar]

- Scrivner, Olga, and Manuel Díaz-Campos. 2016. Language Variation Suite: A theoretical and methodological contribution for linguistic analysis. Proceedings of the Linguistic Society of America 1: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, María José. 2012. El sujeto pronominal usted/ustedes y su posición. Variación y creación de estilos comunicativos. Spanish in Context 9: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi. 2013. Women as leaders of language change: A qualification from the bilingual perspective. In Selected Proceedings of the 6th Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Ana Maria Carvalho and Sara Beaudrie. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 135–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Naomi. 2015. Bilingual language acquisition: Spanish and English in the first six years. Heritage Language Journal 12: 314. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Naomi, and Ricardo Otheguy. 2013. Social class and gender impacting change in bilingual settings: Spanish subject pronoun use in New York. Language in Society 42: 429–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi, and Daniel Erker. 2015. The emergence of structured variability in morphosyntax: Childhood acquisition if Spanish subject pronouns. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho, Rafael Orozco and Naomi Lapidus Shin. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 169–90. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1977. A Discourse Study of Some Aspects of Word Order in the Spanish Spoken by Mexican-Americans in West Los Angeles. Master’s thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1982. Subject Expression and Placement in Spoken Mexican-American Spanish. In Spanish in the United States: Sociolinguistic Aspects. Edited by Jon Amastae and Lucía Elías-Olivares. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1994. Language Contact and Change: Spanish in Los Angeles. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1988. Oral narrative along the Spanish-English bilingual continuum. In On Spanish, Portuguese and Catalan Linguistics. Edited by John Staczek. Washington, DC: Georgetown, pp. 172–84. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen. 1997. Avances en el estudio de la variación sintáctica: La expresión del sujeto. Cuadernos del Sur 27: 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, Carmen, and Andrés Enrique-Arias. 2017. Sociolingüística y Pragmática del español, Segunda Edición. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Julie. 1999. Phonological and Syntactic Variation in the Spanish of Valladolid, Yucatán. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2006. Analysing Sociolinguistic Variation. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali. 2012. Variationist Sociolinguistics: Change, Observation, Interpretation. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, John. 1995. Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes in Linguistic Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Cacoullos, Rena, and Catherine E. Travis. 2011. Testing convergence via code-switching: Priming and the structure of variable subject expression. International Journal of Bilingualism 15: 241–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Cacoullos, Rena, and Catherine Travis. 2018. Bilingualism in the Community Code-Switching and Grammars in Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Cacoullos, Rena, and Catherine Travis. 2019. Variationist typology: Shared probabilistic constraints across (non-)null subject languages. Linguistics 57: 653–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Cacoullos, Rena, and J. Walker. 2009. The present of the English future: Grammatical variation and collocations in discourse. Language 85: 321–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2010. (Inter)subjectivity and (inter)subjectification: A reassessment. In Subjectification, Intersubjectification and Grammaticalization. Edited by Kristin Davidse, Lieven Vandelanotte and Hubert Cuyckens. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 29–71. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, Catherine E. 2005a. Discourse Markers in Colombian Spanish: A Study in Polysemy (Cognitive Linguistics Research). Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, Catherine E. 2005b. The yo-yo effect: Priming in subject expression in Colombian Spanish. In Theoretical and Experimental Approaches to Romance Linguistics: Selected Papers from the 34th Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages, 2004. Edited by Randall Gess and Edward J. Rubin. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 329–49. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, Catherine E. 2007. Genre effects on subject expression in Spanish: Priming in narrative and conversation. Language Variation and Change 19: 101–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, Catherine E., and Rena Torres Cacoullos. 2012. What do subject pronouns do in discourse? Cognitive, mechanical and constructional factors in variation. Cognitive Linguistics 23: 711–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grammatical Person | Pronominal Rate | Overt SPPs | Null Subjects | N | % Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st singular | 32% | 816 | 1743 | 2559 | 55% |

| 2nd singular | 33% | 67 | 137 | 204 | 4% |

| 3rd singular | 42% | 297 | 417 | 714 | 15% |

| All plural | 10% | 114 | 1032 | 1146 | 25% |

| All pronouns | 28% | 1294 | 3329 | 4623 | 100% |

| Predictor | p-Value | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Grammatical person and number of the subject | 4.05−69 | 42 |

| Discourse type | 2.91−20 | 40 |

| Priming | 6.27−19 | 17 |

| Tense Mood & Aspect | 8.91−11 | 23 |

| Speaker’s age | 1.62−8 | 12 |

| Transitivity | 2.15−5 | 18 |

| Factor | Prob. | % Overt | N | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speaker’s Gender | ||||

| Women | [.50] | 28% | 2357 | |

| Men | [.50] | 28% | 2266 | |

| Range | 0 | N.S. | ||

| Speaker’s Age | ||||

| Over 55 | .57 | 33% | 1687 | |

| 30 to 54 | .48 | 27% | 1839 | |

| 15 to 29 | .45 | 24% | 1097 | |

| Range | 12 | 1.62−8 | ||

| Factor | Prob. | % Overt | N | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

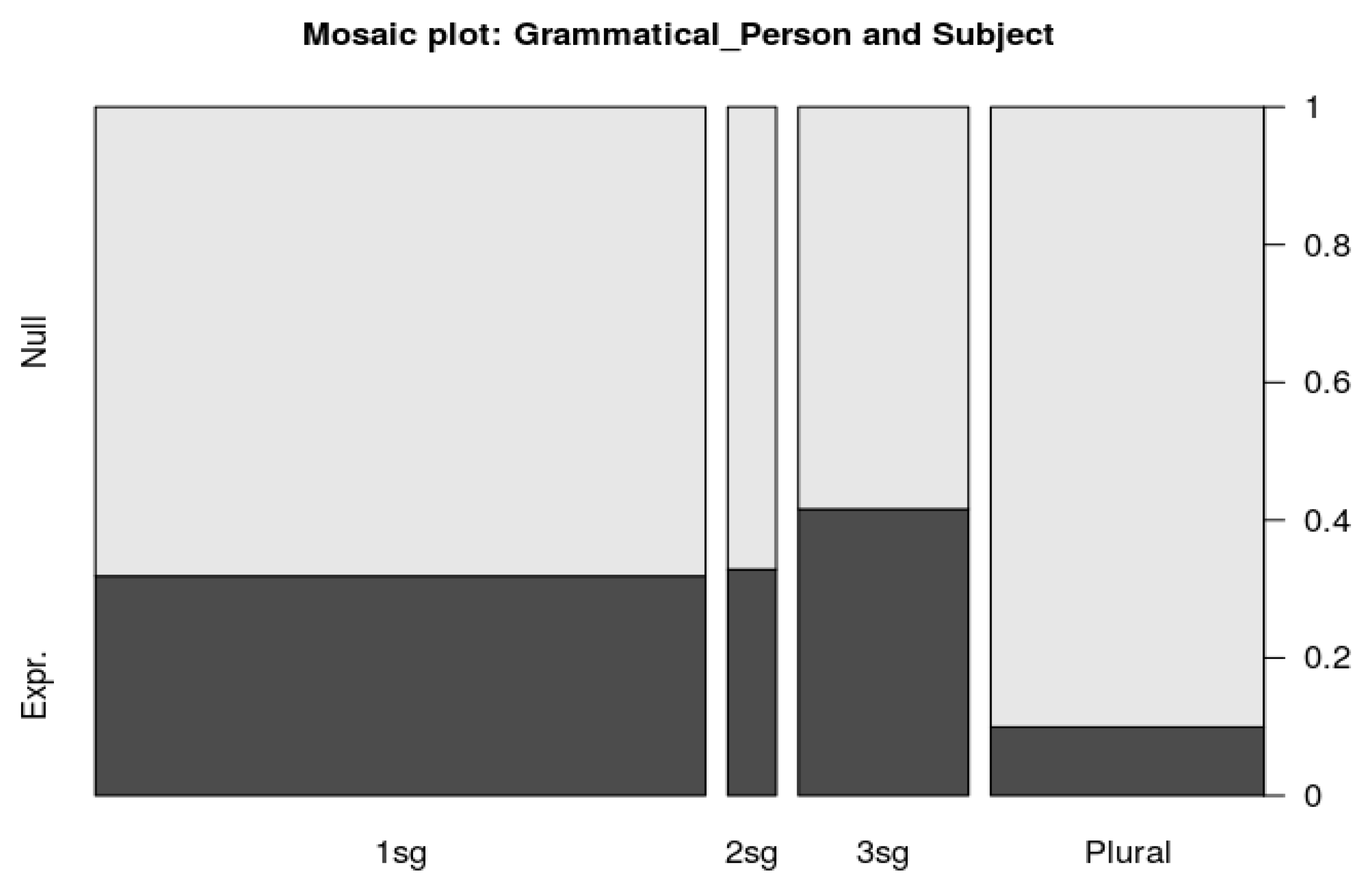

| Grammatical Person and Number of the Subject | ||||

| Third Singular | .64 | 42% | 714 | |

| Second Singular | .59 | 33% | 204 | |

| First Singular | .59 | 32% | 2559 | |

| Plural | .22 | 10% | 1146 | |

| Range | 42 | 4.05−69 | ||

| Discourse Type | ||||

| Opinion | .62 | 33% | 1326 | |

| Narrative | .60 | 29% | 2033 | |

| Hypothetical Situation | .58 | 28% | 560 | |

| Description | .51 | 25% | 355 | |

| Routine | .22 | 7% | 349 | |

| Range | 40 | 2.91−20 | ||

| Tense Mood and Aspect | ||||

| Imperfect | .61 | 37% | 422 | |

| Present Indicative | .53 | 29% | 2832 | |

| Preterite Indicative | .49 | 26% | 563 | |

| Other | .38 | 21% | 806 | |

| Range | 23 | 8.91−11 | ||

| Verb Transitivity | ||||

| Unergative | .61 | 35% | 305 | |

| Transitive | .52 | 31% | 2194 | |

| Unaccusative | .51 | 27% | 1059 | |

| Other | .44 | 26% | 377 | |

| Reflexive | .43 | 19% | 688 | |

| Range | 18 | 2.15−5 | ||

| Priming | ||||

| Previous Overt Subject | .56 | 40% | 970 | |

| Outside Priming Environment | .55 | 35% | 1024 | |

| Previous Null Subject | .39 | 21% | 2629 | |

| Range | 17 | 6.27−19 | ||

| Factor | Prob. | N | % Overt | % Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creer ‘believe’ | .882 | 155 | 72.3% | 3.4% |

| Pensar ‘think’ | .747 | 84 | 50.0% | 1.8% |

| Decir ‘say, tell’ | .737 | 195 | 46.7% | 4.2% |

| Vivir ‘live’ | .728 | 103 | 46.6% | 2.2% |

| Trabajar ‘work’ | .723 | 47 | 48.9% | 1.0% |

| Comprar ‘buy’ | .646 | 27 | 40.7% | 0.6% |

| Ser ‘be’ | .625 | 341 | 33.4% | 7.4% |

| Llegar ‘arrive’ | .618 | 61 | 34.4% | 1.3% |

| Acordarse ‘remember’ | .618 | 24 | 37.5% | 0.5% |

| Conocer ‘know’ | .602 | 84 | 32.1% | 1.8% |

| Querer ‘want’ | .587 | 78 | 30.8% | 1.7% |

| Saber ‘know’ | .572 | 216 | 28.7% | 4.7% |

| Ver ‘see’ | .566 | 170 | 28.2% | 3.7% |

| Levantarse ‘get up’ | .550 | 28 | 28.6% | 0.6% |

| Salir ‘exit, leave’ | .533 | 66 | 25.8% | 1.4% |

| Tener ‘have’ | .510 | 425 | 23.5% | 9.2% |

| Ir ‘go’ | .508 | 132 | 23.5% | 2.9% |

| Estar ‘be’ | .506 | 219 | 23.3% | 4.7% |

| Poder ‘can’ | .504 | 108 | 23.1% | 2.3% |

| Quedar ‘stay’ | .504 | 43 | 23.3% | 0.9% |

| Irse ‘leave’ | .479 | 71 | 21.1% | 1.5% |

| Sentir ‘feel’ | .466 | 60 | 20.0% | 1.3% |

| Pasar ‘pass’ | .465 | 26 | 19.2% | 0.6% |

| Llevar ‘take, carry’ | .458 | 32 | 18.8% | 0.7% |

| Hablar ‘speak, talk’ | .432 | 221 | 18.1% | 4.8% |

| Venir ‘come’ | .407 | 53 | 15.1% | 1.1% |

| Mirar ‘look’ | .402 | 36 | 13.9% | 0.8% |

| Volver ‘return’ | .397 | 31 | 12.9% | 0.7% |

| Imaginarse ‘imagine’ | .375 | 48 | 12.5% | 1.0% |

| Poner ‘put’ | .328 | 38 | 7.9% | 0.8% |

| Verb | Prob. | N | % Overt | Category | X2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creer ‘believe’ | .882 | 112/155 | 72.3% | Monotransitive | 49.86 | <.001 |

| Poner ‘put’ | .328 | 3/38 | 7.9% | |||

| Vivir ‘live’ | .728 | 48/103 | 46.6% | Unergative | 27.43 | <.001 |

| Hablar ‘speak, talk’ | .432 | 40/221 | 18.1% | |||

| Llegar ‘arrive’ | .618 | 21/61 | 34.4% | Unaccusative | 3.79 | .05 |

| Volver ‘return’ | .397 | 4/31 | 12.9% | |||

| Acordarse ‘remember’ | .618 | 9/24 | 37.5% | Reflexive | 4.64 | .03 |

| Imaginarse ‘imagine’ | .375 | 6/48 | 12.5% |

| Collocation | Prob. | % Overt | N | % Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creo | .877 | 73.0% | 108/148 | 3.2% |

| Sabe | .876 | 81.0% | 17/21 | 0.5% |

| Soy | .807 | 60.0% | 39/65 | 1.4% |

| Vivo | .785 | 63.0% | 17/27 | 0.6% |

| Tenía | .770 | 51.6% | 16/31 | 0.67% |

| Pienso | .757 | 54.5% | 30/55 | 1.19% |

| Digo | .754 | 52.3% | 46/88 | 1.90% |

| Estaba | .747 | 51.9% | 14/27 | 0.58% |

| Ve | .739 | 53.6% | 15/28 | 0.61% |

| Dije | .731 | 52.2% | 12/23 | 0.50% |

| Puede | .721 | 45.0% | 9/20 | 0.43% |

| Es | .700 | 37.4% | 34/91 | 1.97% |

| Tiene | .690 | 41.2% | 14/34 | 0.74% |

| Está | .689 | 40.0% | 8/20 | 0.43% |

| Era | .669 | 36.7% | 11/30 | 0.65% |

| Recuerdo | .593 | 36.8% | 7/19 | 0.41% |

| Hago | .591 | 25.6% | 10/39 | 0.84% |

| Conozco | .583 | 30.8% | 12/39 | 0.84% |

| Acuerdo | .567 | 33.3% | 6/18 | 0.39% |

| He tenido | .554 | 26.3% | 5/19 | 0.41% |

| Conocí | .542 | 32.0% | 8/25 | 0.54% |

| Levanto | .538 | 26.1% | 6/23 | 0.50% |

| Voy | .538 | 25.0% | 7/28 | 0.61% |

| Tengo | .530 | 25.0% | 34/136 | 2.94% |

| Veo | .521 | 27.8% | 15/54 | 1.17% |

| Somos | .500 | 23.5% | 8/34 | 0.74% |

| Salgo | .495 | 20.0% | 5/25 | 0.54% |

| Siento | .492 | 22.2% | 8/36 | 0.78% |

| Me voy | .468 | 13.6% | 3/22 | 0.48% |

| Sé | .468 | 22.4% | 34/152 | 3.29% |

| Puedo | .431 | 15.8% | 3/19 | 0.41% |

| Estoy | .421 | 18.0% | 11/61 | 1.32% |

| Imagino | .384 | 13.2% | 5/38 | 0.82% |

| Eramos | .382 | 14.3% | 3/21 | 0.45% |

| Tenemos | .350 | 12.7% | 8/63 | 1.36% |

| Son | .323 | 10.3% | 3/29 | 0.63% |

| Vea | .300 | 7.4% | 2/27 | 0.58% |

| Estamos | .267 | 5.9% | 2/34 | 0.74% |

| Hacemos | .250 | 3.6% | 1/28 | 0.61% |

| Vamos | .227 | 0.0% | 0/23 | 0.50% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orozco, R.; Hurtado, L.M. A Variationist Study of Subject Pronoun Expression in Medellín, Colombia. Languages 2021, 6, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010005

Orozco R, Hurtado LM. A Variationist Study of Subject Pronoun Expression in Medellín, Colombia. Languages. 2021; 6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrozco, Rafael, and Luz Marcela Hurtado. 2021. "A Variationist Study of Subject Pronoun Expression in Medellín, Colombia" Languages 6, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010005

APA StyleOrozco, R., & Hurtado, L. M. (2021). A Variationist Study of Subject Pronoun Expression in Medellín, Colombia. Languages, 6(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010005