2. Corpus of Conversational Santiago Spanish

While priming has attracted great attention in the lab, given the informal nature of

voseo, its association with speech, and its stigmatization, the most reliable data in which to accurately observe its patterning is spontaneous speech, for which we use the Corpus of Conversational Santiago Spanish (CCSS) (cf.

Callaghan 2020).

The CCSS comprises recordings of 36 residents of Santiago made in 2014 and 2015 by the first author. Participants were recruited from the Province of Santiago de Chile, an area enclosed by mountains to the east, west and north. They were all born and raised in Chile with Chilean parents, were residing in Santiago at the time of the recording, and had not lived outside Santiago for an extended period of time in the last five years—that is, all were santiaguinos, or capitalinos, as people from Santiago are known in Chile.

The interactional nature of the second person and the association of voseo with informal speech between people who know each other render conversation the most appropriate genre in which to study its use. Thus, all recordings are of conversations between friends, family members and colleagues, that took place in the home, car or workplace of one of the participants, that is, the kind of interaction they would be likely to have ordinarily. Participants were told that the focus of the study was the relationship between language and society in Chile, but no further information about any linguistic features of interest was given. They were not assigned topics to discuss, but rather were free to talk about anything that they deemed appropriate. A range of different topics came up, including football, movies, travel, parties, mutual friends, school, work, children, debt collectors, the police, and so on.

Out of a total of some 50 recordings comprising 36 h of speech, 17 were selected for inclusion in the corpus. These were primarily two-party conversations (n = 12), but there were also four three-party and one four-party conversation. Recordings were made by 13 research assistants, each of whom was a participant in one or two conversations. The recordings were an average of 50 min long (ranging from 21 to 82 min), and an average of 30 min were transcribed from each, generally starting from some 15 min into the conversation. This provides a total of nine hours of speech and approximately 110,000 words for analysis.

Table 1 presents the breakdown of the participants for age and gender. Participants range from 20 to 62 years of age, split in this table at 35 years, giving a relatively even distribution in each age group. They were of varying social backgrounds: 22 of the 36 have university education; they have a wide range of occupations, working in areas such as education, health care, management, construction, hospitality, and transport; and they come from different

comunas, regions of Santiago that have been used to determine socioeconomic class (e.g.,

Stevenson 2007, p. 233).

2 The data were transcribed by five trained Chilean Research Assistants, who produced time-aligned orthographic transcriptions in F4 (

Dresing and Pehl 2015). The transcription method followed the principles outlined in Du

Bois et al. (

1993), breaking the speech into Intonation Units (IUs), prosodic units generally of two to five words, and rarely more than one clause (though often less, e.g., for single-word IUs consisting of backchannels, response tokens, or discourse markers, such as

sí ‘yes’,

cierto ‘exactly’, or

cachái ‘you know’). A set of orthographic conventions was established, particularly important for the feature under study which occurs predominantly in informal speech and is consequently highly variable in orthographic representation. This is particularly so for syllable-final /s/, which is variably aspirated or elided in Chilean Spanish (cf.

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2009, pp. 119–20). Thus, pronoun

vos is spelt as

vo,

voh,

bo, or

boh; this was standardized to

vos for the transcriptions here. In addition, we follow standard spelling conventions in writing

voseo forms ending in /ay/ without final /s/

(-ái or

-ai) and those ending in /is/ with final /s/ (

-ís) (see

Table 2).

This conversational corpus, collected by community members and transcribed following defined protocols, provides ideal data to probe the tuteo/voseo variation in Chile, and in particular, the impact that priming has on its use.

3. The Chilean Second-Person Singular

Chilean Spanish is characterized by the co-existence of two 2sg familiar forms, both in the pronouns tú and vos, and in the verb forms, tuteo and voseo, illustrated in (4) and (5), respectively. These forms can be contrasted with usted, the so-called “polite” 2sg form (which takes a third-person singular verb form). There are just 55 occurrences of usted verb forms in CCSS, accounting for two percent of all 2sg verbs, almost all of which are either in quoted speech or are to older speakers. Thus, we consider usted to be outside the variable context, which we define as second-person singular familiar verbal forms.

(4) Tú tienes ahorros.

‘You -tú have-tuteo savings.’

(Savings; 1302; Carolina)

(5) o sea vos no tenís ningún concierto.

‘In other words you-vos have-voseo no concert.’

(Football; 947; Matías)

Chilean Spanish has distinct

voseo forms throughout most of the verbal paradigm as seen in

Table 2, which presents the morphology of the set of TAMs for verbs ending in

-ar on the left, and

-er or

-ir on the right (illustrated for

-er, which is identical to

-ir for

voseo, though not for

tuteo). As can be seen, there are distinct forms for

tuteo and

voseo for all but the Imperative, Preterit and Synthetic Future, which we discuss below.

Tuteo and

voseo differ in their morpho-phonological shape—

tuteo is most characterized by /as/ and /es/ endings, and

voseo by /ay/ and /is/ endings. This is likely to promote priming within the paradigms, as shared shape renders individual instances of

tuteo or of

voseo obviously similar, even for those ignorant of their grammatical status. The

voseo > voseo priming is not, however, dependent on shared morpho-phonological shape, as we show below (

Section 4.1).

| | −AR Verbs | −ER/−IR Verbs |

|---|

| | tuteo | voseo | tuteo | voseo |

|---|

| Present indicative | lleg- as | lleg- ái | com- es | com- ís |

| Imperfect indicative | lleg- abas | lleg- abai | com- ías | com- íai |

| Conditional | lleg- arías | lleg- aríai | com- erías | com- eríai |

| Present subjunctive | lleg- ues | lleg- uís | com- as | com- ái |

| Imperfect subjunctive | lleg- aras | lleg- arai | com- ieras | com- ierai |

| Imperative | lleg- a | | com- e | |

| Preterit | lleg- aste | | com- iste | |

| Synthetic Future | lleg- arás | | com- erás | |

Historically, the Imperative, Preterit and Synthetic Future had distinct

tuteo and

voseo forms (e.g.,

Torrejón 1986, p. 679), but today, only what were the

tuteo forms remain in wide use, while the

voseo forms are vanishingly rare. In the CCSS, of 560 Imperative tokens, there are no distinct

voseo forms; of 167 2sg familiar Preterit tokens, there is only one token of the

-stes form, which is purported to be historically

voseo (

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2009;

Torrejón 2010)

3; and the Synthetic Future does not occur, as the Analytic Future is the preferred form (

n = 86). As invariable forms, these TAMs fall outside the variable context and must be excluded from analysis (as has been done in previous variationist studies of

voseo, e.g.,

Fernández-Mallat 2018, p. 100;

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2016, p. 70).

However, here our interest is in how speakers classify these forms. Do they remain associated with their tuteo origins, as an instance of a general [Verb-tuteo] construction, or are they genuinely neutral, as syncretic forms that collapse the tuteo/voseo distinction? As the tú pronoun occurs with both tuteo and voseo, presence of a subject pronoun is not a reliable indication of the form of these verbs, and furthermore, subjects are most commonly left unexpressed, as in example (6) in the Imperative, and (7) in the Preterit. Thus, we appeal to priming to establish the status of these forms: if they indeed share a mental representation with the tuteo forms, then we would expect them to favor a subsequent tuteo; the lack of such a priming effect would suggest that this association has been lost.

(6) Consíguete un pololo.

‘Get-imperative-fixed yourself a boyfriend.’

(Cousins; 1180; Emilia)

(7) te pusiste huevón ya,

‘you-Ø already turned-preterit-fixed into an idiot,’

(Takeaway; 4; Claudia)

Another non-variable form is the lexically specific, fossilized construction

cachái, the

voseo form of the verb

cachar ‘to understand, get’ (possibly from English ‘to catch’,

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2016, p. 100). In the Present Indicative,

cachar occurs virtually categorically in the

voseo form in the CCSS (with just one

cachas in contrast to 360

cachái), consistent with what has been reported in other studies (e.g.,

Fernández-Mallat 2018, p. 70;

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2016, p. 100;

San Martín Núñez 2011, pp. 159–62). Like the invariable TAMs above, then,

cachái falls outside the variable context. But the question remains, however, of whether speakers perceive

cachái to be an instance of the [

Verb-voseo] construction. It is used primarily as a discourse marker, akin to English ‘you know’, as in (8) (322/360). It also occurs as a full verb (

n = 28), for example, with a direct object, meaning to perceive or realize something (cf.

Urzúa-Carmona 2006, pp. 100–5), as in (9), and with a variably expressed pronoun (nearly always

tú, 10/11 instances).

(8) tú enrolái como si fueran más delgados,

cachái?

‘you-tú roll-voseo ((cigarettes)) as if they were thinner,

you-Ø know-cachái?’

(A bit of everything; 401–402; Andrea)

(9) y ahí cachái cómo es el nivel de ellos po huevón.

‘And that’s when you-Ø realize-cachái what level that they’re at man.’

(Barcelona; 925; José)

Cachái has emerged within the last fifty years or so, in parallel with the reported rise of

voseo (e.g.,

San Martín Núñez 2011, pp. 159–62). It is highly frequent in the speech of young Chileans today, accounting for 94% of all instances of the verb

cachar in the CCSS, and around 25% of all 2sg familiar forms produced by speakers of 35 years and younger (of a total of 1242 tokens).

4 For one speaker (Marcela, 31 years old; 123 tokens),

cachái constitutes 55% of her 2sg familiar tokens. Though

cachái does occur in discourse of older speakers, it is much rarer, accounting for just 3% of all 2sg familiar forms (of a total of 904).

Do speakers consider

cachái to be a

voseo form, that is, a manifestation of the [

Verb-voseo] construction, or are they unaware of its structure? Although it has a similar phonological shape to the

voseo Present Indicative, with the /ay/ ending, there is no

tuteo form to contrast it with, and it has been proposed by some authors that it has lost its status as a verb (e.g.,

Gille 2015;

Mondaca Becerra et al. 2015;

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2016, p. 100). Here, too, priming provides insight into the status of this form: if it is recognized as a

voseo form, then it should prime a subsequent

voseo; the lack of such an effect would suggest that it has become fully autonomous and is no longer attached to the

voseo paradigm.

A final consideration is the impact of a pronoun. As already noted, Spanish has variable subject expression, and thus subject pronouns may be expressed (as

tú or

vos in this case) or they may be left unexpressed. The

vos pronoun, however, shows very minimal use. The CCSS presents a total of 304 tokens of the

tú subject pronoun, but just 10 of the

vos subject pronoun.

5 And while the

vos subject pronoun does not occur with

tuteo, the

tú pronoun occurs with both

tuteo and

voseo verb forms, resulting in the occurrence of both [

tú +

Verb-tuteo] and [

tú +

Verb-voseo] constructions. The overwhelmingly favored form with both

tuteo and

voseo (accounting for 80% of tokens occurring in the variable context) is with an unexpressed subject. While the use of

voseo with no pronominal subject has been termed crypto-

voseo, in the sense that the very existence of a parallel

voseo paradigm is concealed by the absence of the

vos pronoun (

Lipski 1994, p. 143), it has also been proposed that the “underlying” pronoun in such a context is “always

tú, as a neutral unmarked form” (

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2016, p. 93). Here again, we use priming to ascertain the status of “mixed

voseo” [

tú +

Verb-voseo], and the impact the presence of a

tú pronoun has on the representation of a

voseo verb form.

We have established, then, that instances of the Imperative, Preterit and

cachái fall outside the variable context, but that tokens with a

tú pronoun do exhibit variability and thus can be included.

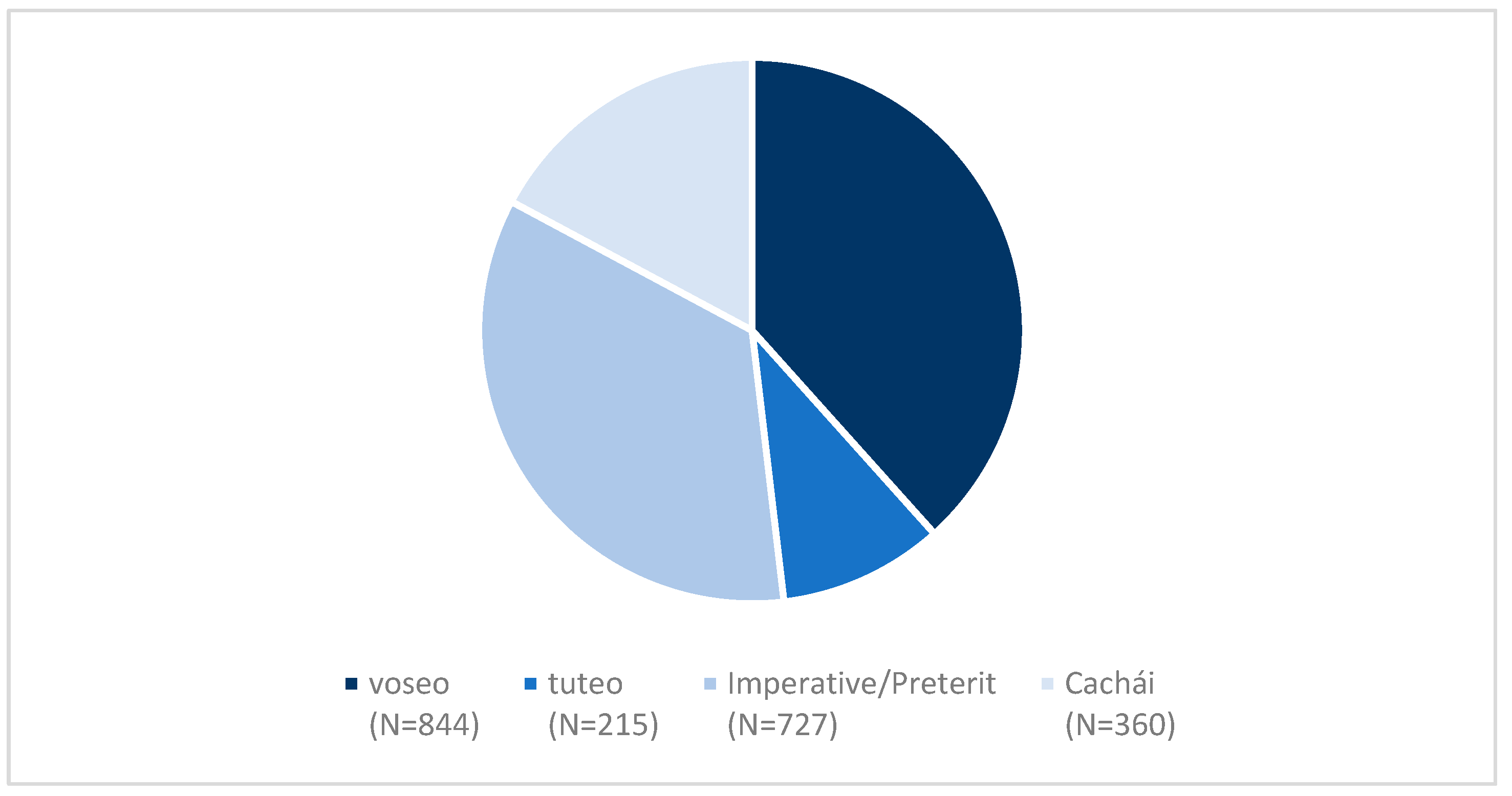

Figure 1 depicts the distribution in the data across the non-variable and variable contexts. What is of particular note here is that the non-variable contexts make up over one half of all 2sg familiar instances—the Imperative and Preterit together represent 35%, and

cachái a further 17%. Within the variable context, the rate of

tuteo is 20%, in contrast with 80%

voseo. What factors impact this variation?

Change over Time

The rate of

tuteo has declined in recent Chilean history, as

voseo has grown in use. This is evident in the data under study here in comparisons across speakers of different ages. As has been robustly demonstrated in sociolinguistic research, the relative stability of patterns of speech in adults allows for comparisons across age groups to serve as a proxy for language use in different time periods, and differences as indicative of change in apparent time (

Sankoff 2006).

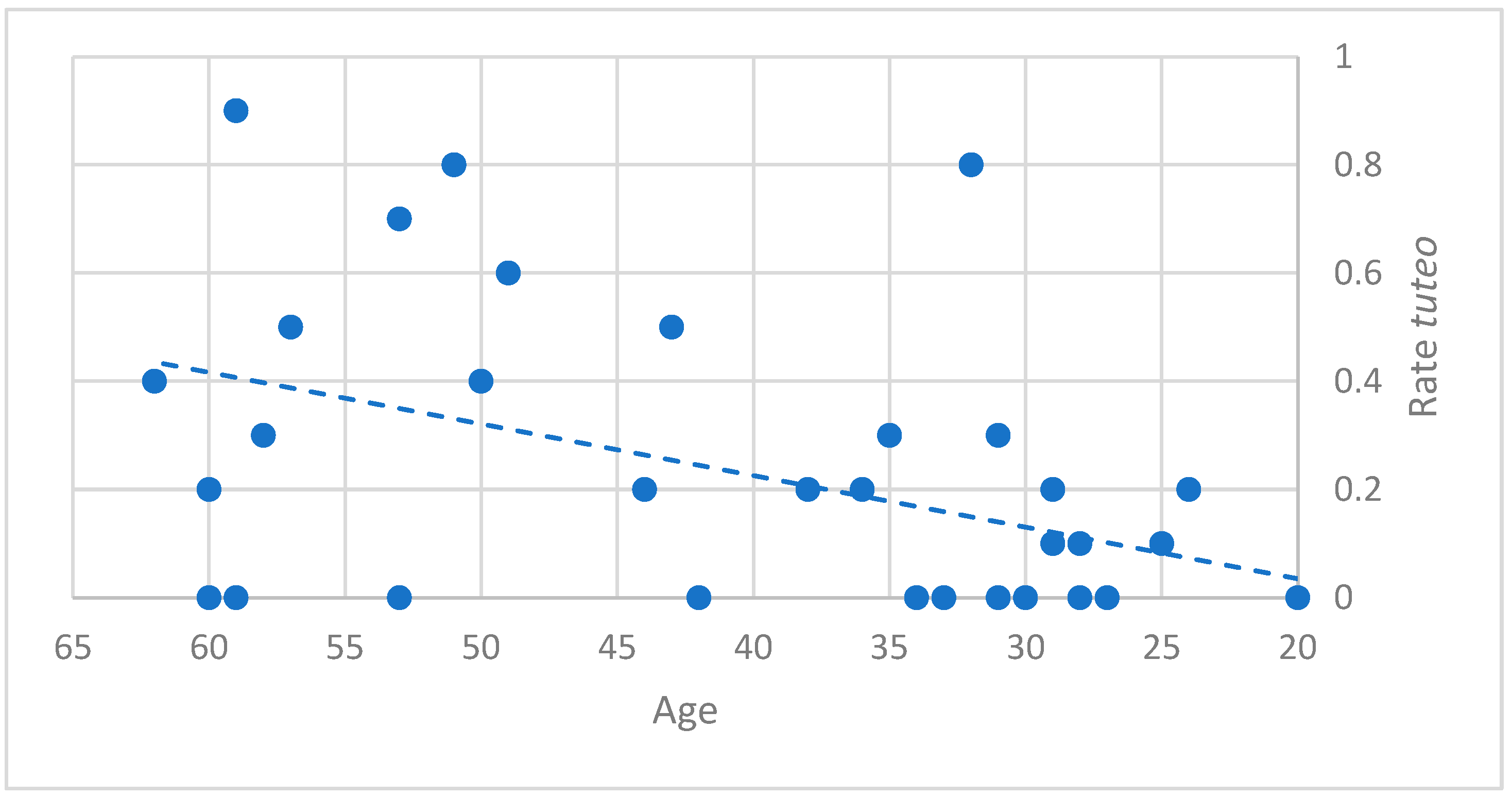

The rates of

tuteo vs.

voseo by age are presented in

Figure 2, which illustrates an overall drop in

tuteo for younger speakers, supporting the change over time towards

voseo. Comparing the age groups in

Table 1, the rate of use drops from 32%

tuteo (138/430) for the older speakers to just 12% (77/629) for the younger speakers.

We also see here a large amount of variability even for speakers of similar ages. This is partly due to a range of conditioning factors, including social (gender and socioeconomic class) and linguistic factors (previous realization, subject pronoun expression, discourse type, clause type, morphological class of verb). Examination of the impact of these factors by

Callaghan (

2020) revealed wholesale change in the nature of this variation, in that not only has the rate of

tuteo dropped over time but the conditioning has also changed. Older and younger speakers differ in terms of the set of significant predictors (e.g., discourse type is significant for older speakers only, for whom

tuteo is disfavored with generic subjects), and in the relative strength of the effect those factors have (e.g., clause type has a stronger effect in younger than older speakers, with a greater disfavoring of

tuteo in questions). In some cases, they differ in the direction of effect (e.g.,

tuteo is favored by higher social classes for the older age group, but by lower social classes for the younger age group) (cf.

Callaghan 2020, p. 195).

One predictor that remains stable across speakers of different ages is previous realization, as a manifestation of priming, which furthermore has the greatest magnitude of effect for both age groups (and overall, see Figure 6 below,

Section 4.4). We will therefore now turn to consider this effect in more detail, paying particular attention to what it reveals about speaker awareness of

tuteo/voseo variation.

4. Priming as a Diagnostic of Associations between tuteo and voseo

Considering priming to be a measure of speaker associations between forms, priming effects can shed light on whether speakers distinguish between the tuteo and voseo paradigms, or whether, as a result of mixing, stigmatization and “invisibilization”, they have become conflated in speakers’ variable grammars. We address this question in three ways. We first consider the effect of a variable tuteo or voseo form in the preceding discourse. We then examine the effect of the presence of a non-variable 2sg familiar form, namely verbs occurring in TAMs that are historically tuteo (in the data here, the Imperative and Preterit), and the fossilized voseo form cachái. For our third set of analyses, we consider the effect of the “mixed voseo” and whether the presence of a tú pronoun weakens the association between voseo forms.

To provide an overall picture of the nature of the priming effect, we describe the general trends through descriptive statistics and visualizations, before testing for statistical significance in those trends with generalized linear mixed effects models and a random forest analysis. For these priming analyses, we exclude tokens for which the previous form or the status of the pronoun (as tú or unexpressed) could not be coded due, for example, to unclear speech (n = 43); seven instances of a vos pronoun in the variable context were also excluded, leaving a total of 1009 tokens for analysis.

4.1. The Impact of the Form of the Previous Realization

We begin by examining the role that the form of previous realization plays in conditioning the tuteo/voseo variation. If speakers recognize and negotiate two separate paradigms, then this should be evident in the patterns resulting from priming: a previous voseo should favor the repetition of a subsequent voseo form, and a previous tuteo should favor a subsequent tuteo. An absence of priming would support the interpretation that the two paradigms are collapsed, and that speakers do not distinguish between forms.

The sample was coded for the form of the most recent 2sg familiar verb occurring within the previous five IUs, generally, around 20 words. As priming is known to weaken with distance (e.g.,

Szmrecsanyi 2005, p. 139;

Travis 2007, pp. 119–21), this relatively close measure maximizes the possibility of observing an effect. Previous 2sg familiar forms by both the interlocutor and the same speaker were included. Of the 356 instances of a previous

tuteo or

voseo, 69 were produced by the interlocutor. These tokens maintain a similar priming effect to those produced by the same speaker, and thus we do not separate out same speaker- from interlocutor-produced primes for the purposes of the analyses.

6Five possible previous realizations were coded: a previous tuteo, as in (10) (where the prime is underlined, and the target in bold); previous voseo (11); previous invariable Imperative or Preterit forms (12); previous cachái (13); and no other 2sg familiar token within the previous five IUs.

(10) no andabas conmigo cuando te perdías.

‘You-Ø weren’t-tuteo with me when you-Ø got lost-tuteo.’

(Memories; 1261; Trinidad)

(11) Sabís la cagada que le vai a dejar a tu amigo huevona?

‘Do you-Ø know-voseo the problems you-Ø are going-voseo to leave your friend idiot?’

(Police; 484; Matilda)

(12) Métete cuando --

cuando quieras.

You-Ø join in- imperative-fixed when --

whenever you-Ø want-tuteo.

(Barbeque; 1430–1431; Viviana)

(13) Cristián: yo pierdo tiempo con esas huevadas,

cachái?

Claudia: perdís tiempo.

Cristián: ‘I waste time on that shit,

you-Ø know-cachái?’

Claudia: ‘You-Ø waste-voseo time.’

(Takeaway; 221–223; Cristián/Claudia)

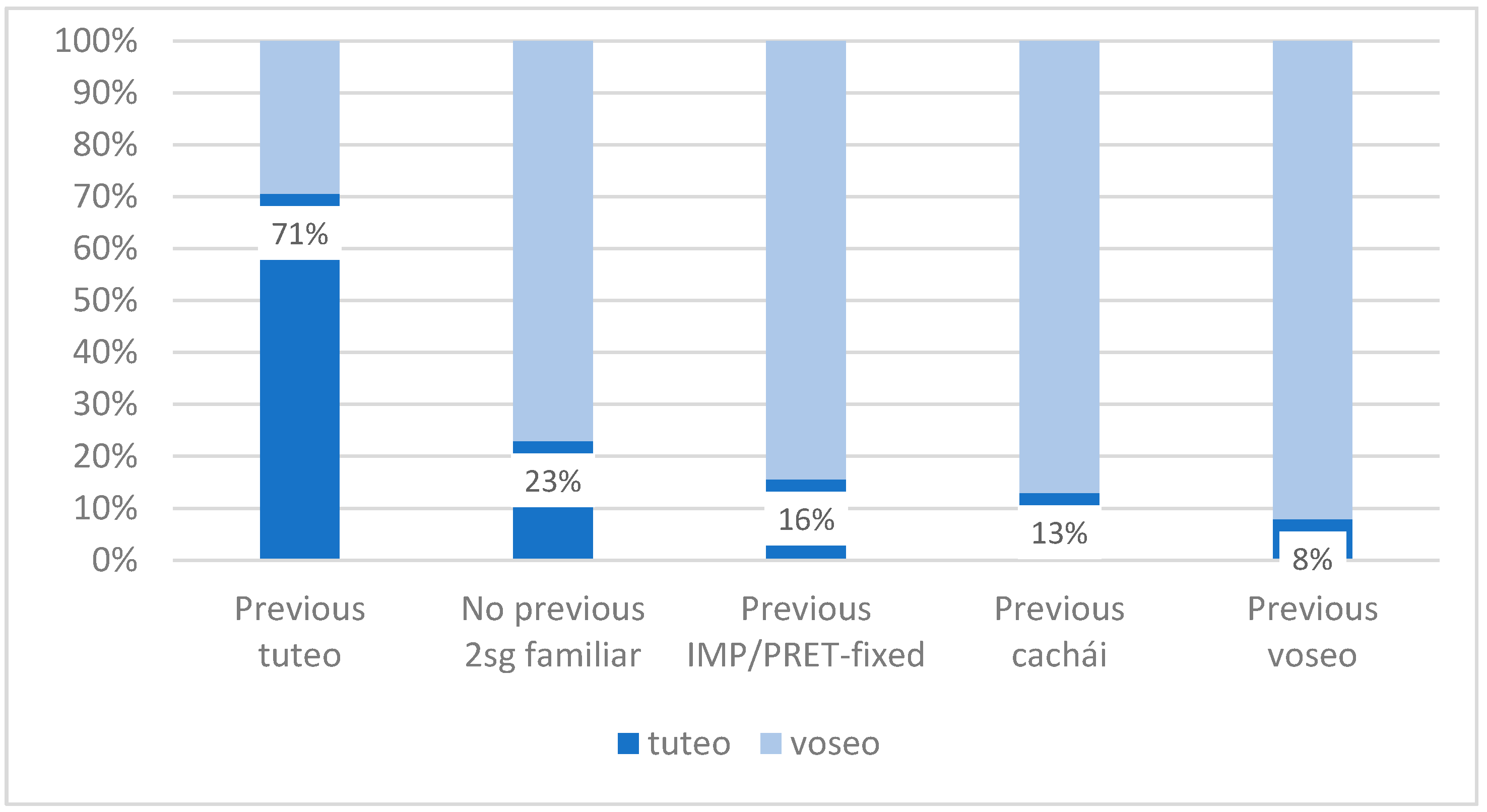

Table 3 shows the distribution of the data according to these five previous contexts, and the rate of

voseo vs.

tuteo in each, which is also depicted in

Figure 3. We see in

Table 3 that one-third of the tokens have a

tuteo or

voseo in the previous five IUs (n = 356), and just under one-half have no 2sg familiar token within the previous discourse, providing sufficient data for meaningful comparisons. A small proportion occurred in the context of a previous Imperative or Preterit, or of a previous

cachái, which we will consider in the following section. For now, we concentrate on the context with a previous (variable)

voseo or

tuteo, as compared with no previous mention, the two left-most columns and the right-most column in

Figure 3.

As can be seen, the rate of

tuteo is overwhelmingly highest with a

tuteo in the previous discourse, at 71%, and lowest in the context of a previous

voseo, at just 8%; in the absence of a prime (with no previous 2sg familiar form), the rate is in between, at 23%. This clearly shows a priming effect, that will be corroborated statistically in

Section 4.4 below—

tuteo is favored in the context of a previous

tuteo, and is disfavored in its absence, particularly in the context of a previous

voseo.

We are able to verify that the favoring of

tuteo following a preceding

tuteo, and

voseo following a preceding

voseo, is a real priming effect, and not simply the inevitable repetition of the same form by speakers with very high rates of one or the other form by comparing the impact of the previous realization across speakers with different baseline rates of

tuteo (cf.

Sankoff and Laberge 1978;

Torres Cacoullos and Travis 2018, p. 90). Speakers were binned into four groups according to their overall rate of

tuteo, separated by 20 percentage points. It was not possible to compare the speakers individually, as few produce enough tokens to reliably identify individual differences—the 36 speakers produce an average of 28 tokens each, with a median of 24, and a range from three to 89. Only five speakers produce over 50 tokens, seven between 30 and 50, and 14 under 20. Fifteen speakers (10 of whom produce under 30 tokens) do not use

tuteo at all in the data, and they are excluded from these comparisons.

7Figure 4 shows the rate of

tuteo for these groups of speakers when there is no 2sg form in the previous five IUs (the solid, darkest line), in the context of a previous

tuteo (the line marked with circles) and a previous

voseo (marked with squares). Here we see that, for both low and high users of

tuteo, their rate of

tuteo is higher when there is a

tuteo in the preceding environment and their rate of

voseo is higher when there is a

voseo in the preceding environment; that is, priming holds independently of the rate of

tuteo. That priming is not limited to any individual speakers is confirmed in the mixed-effect models reported below (

Section 4.4), where the priming effect emerges with speaker run as a random effect.

A further observation from

Figure 4 is that that the strongest

tuteo > tuteo priming is found among those with lower overall rates of

tuteo: for speakers with rates of

tuteo of under 50% (the first two bins), the rate of

tuteo in the presence of a previous

tuteo deviates more from that in the absence of a prime than it does for speakers with rates of over 50%. Conversely, the strongest

voseo > voseo priming occurs amongst those speakers with high baseline rates of

tuteo (the last bin). Such patterning is consistent with what has been reported in the priming literature, whereby less frequent variants tend to exert a stronger priming effect, under what has been described as “surprisal” (

Jaeger and Snider 2007). Thus, while in general, speakers are sensitive to the form of a previous mention, given the predominance of

voseo, those with lower rates of

tuteo are even more so. This is corroborated by the findings across age group: younger speakers, who tend to have lower rates of

tuteo (as seen in

Figure 2), exhibit a stronger

tuteo > tuteo priming effect than older speakers (

Callaghan 2020, p. 202). From a usage-based perspective, we might interpret this in terms of an unexpected instance being more salient (

Jaeger and Weatherholtz 2016), and therefore more readily retrieved and reused in the subsequent discourse.

The priming observed suggests that speakers recognize the [

Verb-voseo] construction as distinct from the [

Verb-tuteo] construction. But to establish this, we must also demonstrate that priming holds across different morpho-phonological realizations of

voseo, and is not limited to instances that share the same form. If priming were reliant on similarity of shape, then it should be manifestly stronger when the prime and target share the same form (/ay/ > /ay/ or /is/ > /is/), as in (14) below, than when they do not (/ay/ > /is/ or /is/ > /ay/) as in (11) above. However, although the rate of

voseo (vs.

tuteo) is marginally higher when the

voseo prime and target take the same shape than when they do not (88%, 168/190 vs. 82%, 98/120), this is not significant (

p = 0.13, Fisher’s Exact Test).

8 That different

voseo morpho-phonological endings prime each other is evidence for

voseo as an abstract category in speakers’ mental representations. The priming here is thus functioning at a schematic level while being marginally strengthened when morphological specificity is shared (cf.

Rosemeyer and Schwenter 2017, p. 30;

Travis et al. 2017, p. 294).

(14) llegái al aeropuerto,

se te suben dos personas,

y las vai a dejar a Santiago,

‘you-Ø arrive-voseo at the airport,

Two people get in,

and you-Ø go-voseo to drop them in Santiago,’

(Back to Santiago; 76–78; Ernesto)

4.2. The Status of Non-Variable Constructions: Imperative, Preterit and cachái

Having established tuteo > tuteo and voseo > voseo priming, we can now use priming to test the status of the non-variable constructions, and whether or not they retain a link with their respective tuteo/voseo origins. The question we ask is: do speakers associate the historically tuteo TAMs (here, the Imperative and Preterit) with the [Verb-tuteo] construction and the voseo-based cachái with the [Verb-voseo] construction? Evidence of this would be found in a rate of tuteo in the context of a previous Imperative or Preterit parallel or similar to that in the context of a previous tuteo, or at least a higher rate than when there is no prime. Similarly, for cachái, evidence would be a rate of voseo in the context of a previous cachái parallel or similar to that in the context of a previous voseo and higher than that in the absence of a prime.

As we see in

Table 3 and

Figure 3 above, the rate of

tuteo in the context of a previous Imperative or Preterit is just 16%. This is less than one quarter of that in the context of a previous

tuteo (71%), and thus these are clearly treated quite distinctly. It is only slightly lower than in the absence of a prime (23%), and we will see below that this difference is not significant (Table 5,

Section 4.4). This indicates that the Imperative and Preterit have shed their historical associations with

tuteo, and function as syncretic, neutral forms.

For

cachái, the rate of

tuteo following a previous

cachái (13%) is in between that when there is no prime (23%), and when there is a previous

voseo (8%). The statistical models we report on below (

Section 4.4) indicate that, in the data overall, the rate of

tuteo in the context of a previous

cachái is not significantly different from that when there is no prime (

p = 0.44), suggesting that

cachái may be a neutral form. We also find that the impact of a previous

cachái is significantly different from that of a previous

voseo in the data overall (

p = 0.02). However, this difference is not significant for the young speakers, who are the main users of

cachái (

p = 0.09), indicating that for them at least

cachái retains a degree of association with the

voseo paradigm.

The classification of these forms is not a minor issue for the analyst, as they account for approximately one-half of all 2sg familiar tokens, as we saw in

Figure 1. The patterning we have observed for priming validates the exclusion of both syncretic forms and

cachái from the

tuteo/voseo variation, and illustrates how priming can help illuminate what counts as an instance of a construction, and so what falls in, and outside of, the variable context (cf.

Tamminga 2016).

4.3. The Status of “Mixed voseo”

The usage data thus far demonstrate strong awareness of distinct

voseo vs.

tuteo paradigms, despite metalinguistic commentary to the contrary. A remaining question is the status of mixed

voseo, that is, a

voseo verb form with a

tú pronoun, seen in (15) (and in (2) above), which we might expect to be less associated with

voseo than instances that occur without a

tú pronoun. If this is the case, then there should be a weaker priming effect when the target verb occurs with a

tú pronoun than without.

(15) Tú creís que va a entender eso el niño?

‘Do you-tú think-voseo the kid is going to understand that?’

(Family; 361; Sara)

For a first view, we look to patterns of subject expression. While theoretically there are three options for 2sg subject realization (

tú, vos, Ø), due to the rarity of the

vos pronoun (just 10 tokens in the CCSS), only two are fully exploited by speakers,

tú or an unexpressed subject. Subject expression can therefore be used as a proxy for the strength of association between the pronoun and verb: if speakers do not distinguish between the two paradigms, then we would expect the rate of occurrence with a

tú pronoun to be similar across

voseo and

tuteo.

Table 4 compares the rates of subject pronoun expression with each verb form. As can be seen, there is a higher rate of pronominal expression with

tuteo than

voseo (31% vs. 18%), indicating that, though speakers do use a

tú pronoun with

voseo verb forms, they are less likely to do so than with a

tuteo verb form. The favoring effect of a

tú pronoun on rate of

tuteo also emerges as significant in the statistical model (see

Table 5,

Section 4.4). Furthermore, mixed

voseo accounts for under 15% of the data (147/1009), suggesting that this is a relatively minor phenomenon, despite the reported predominance of this form in the literature (e.g.,

Torrejón 1986, p. 682).

It is important to note that multiple factors condition patterns of subject expression (cf.,

Torres Cacoullos and Travis 2018, chp. 5), such that care needs to be taken in comparing overall rate differences. A preponderance of tokens in contexts favorable to pronominal expression (e.g., non-coreferential contexts) may result in a higher rate of expression. Such analyses are beyond the scope of this paper, and we now turn to priming as a further measure of the status of mixed

voseo.

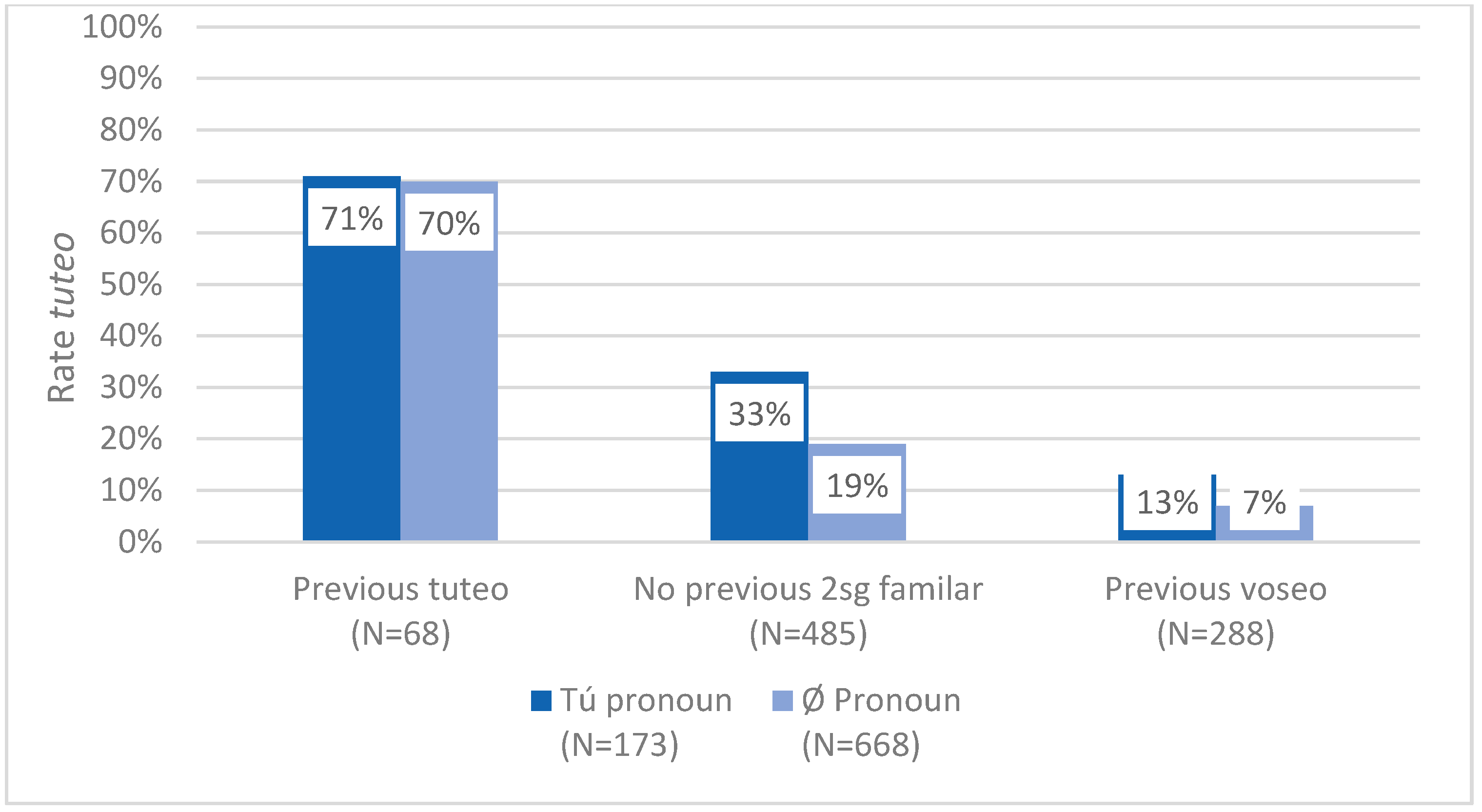

Figure 5 shows the rate of

tuteo across three priming contexts (previous

tuteo, no 2sg familiar token in the previous five IUs, previous

voseo), with a

tú pronoun (darker column, on the left of each pair) and with no subject pronoun (lighter column on the right). First, note that, in the absence of a prime, we observe the predicted effect: a higher rate of

tuteo with a

tú pronoun than with no pronoun. But we also observe a nearly identical priming effect with and without a

tú pronoun: with a

tú pronoun, the rate of

tuteo rises from 13% with a

voseo previous mention to 33% with no previous mention, to 71% with a

tuteo previous mention; with no subject pronoun, it rises from 7% to 19% to 70%. That is, whether or not the target occurs with a

tú pronoun, speakers are sensitive to the overall tendency to repeat the previous form.

It is particularly telling that, in the context of a previous

tuteo, the presence of a pronoun has no impact on the rate of

tuteo; that is, the previous

tuteo overrides the pronoun effect. Although the presence of a

tú pronoun does impact the rate of

tuteo in the context of a previous

voseo, the effect of a previous

voseo is still felt in this context, where the rate of

tuteo is barely one-third that in the absence of a prime (13% vs. 33%). The favoring of

tuteo by a

tú pronoun is confirmed in the statistical models presented below (

Table 5,

Section 4.4), which also reveal that there is no significant interaction between the presence of a pronoun and the previous realization, indicating that each holds independently of the other.

The avoidance of the

vos pronoun, the use of a

tú pronoun with a

voseo verb form, and reports that Chileans claim not to use

voseo because they associate it exclusively with the pronoun may seem to support an interpretation of pronouns as more salient in speakers’ minds than verb forms. This is precisely what has been proposed in the literature, in accordance with the notion that the greater saliency of the

vos pronoun as a lexical item has contributed to it becoming stigmatized, and therefore avoided, while

voseo verb forms fly under the radar, allowing for their expansion in use (

Bertolotti 2015, p. 19;

Huerta Imposti 2011–2012, p. 52;

Hummel 2010, p. 112;

Stevenson 2007, p. 167). This is not, however, what we observe in usage patterns, where priming of verb forms is upheld even in the presence of a

tú pronoun. Though mixed

voseo has been used as evidence of the loss of awareness of the

voseo paradigm (

Carricaburo 1997, p. 34;

Huerta Imposti 2011–2012, p. 54), what the priming data show is that even mixed

voseo is treated by speakers as an instance of the [

Verb-voseo] construction.

These results also allow us to respond to the suggestion that there exists an underlying

tú pronoun for all instances of 2sg familiar verbs with an unexpressed subject (e.g.,

Rivadeneira Valenzuela 2016, p. 93). The priming patterns we observe do not support this interpretation, but rather indicate that speakers create their utterances with

tuteo and

voseo, and with or without pronouns, based on probabilistic usage-based factors, influenced by, among other things, what precedes in the discourse.

4.4. Statistical Analyses

Having observed the general patterns, we now test the statistical significance of these differences, using generalized linear mixed effects models with the glmer() function in R (

Bates et al. 2019;

R Development Core Team 2019). Models were fit with verb form (

tuteo/voseo) as the dependent variable, and previous realization, presence of a

tú pronoun, and age as independent variables. For previous realization, the absence of a prime was used as the reference level; an unexpressed subject was the reference level for pronoun; and age was modeled continuously. Three- and two-way interactions between previous realization, pronoun and age were tested, and then pruned from the model, as none were significant. To take into account differences between speakers and verb types, speaker and verb were included as random intercepts.

Table 5 presents the final model summary.

Table 5.

Output of a generalized linear mixed effects model predicting tuteo.

Table 5.

Output of a generalized linear mixed effects model predicting tuteo.

| | Estimate | Std. Error | Z | p |

|---|

| (Intercept) | 5.86752 | 1.16632 | 5.031 | <0.001 |

| Previous tuteo | −1.53467 | 0.33822 | −4.538 | <0.001 |

| Previous voseo | 0.87474 | 0.28351 | 3.085 | <0.01 |

| Previous syncretic | 0.37496 | 0.32207 | 1.164 | =0.24 |

| Previous cachái | −0.40438 | 0.52527 | −0.770 | =0.44 |

| Pronoun tú | −0.90796 | 0.23260 | −3.903 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.09075 | 0.02627 | −3.454 | <0.001 |

First, this model corroborates the overall priming effect we saw in

Table 3 and

Figure 3: compared with when there is no prime in the previous discourse, the rate of

tuteo is significantly lower in the context of a previous

voseo and significantly higher in the context of a previous

tuteo. Thus,

tuteo primes a subsequent

tuteo and

voseo primes a subsequent

voseo, confirming that these speakers do recognize a relationship between distinct verbs produced in the

voseo vs.

tuteo forms. Despite a lack of explicit metalinguistic awareness and mixing of

voseo verb forms with a

tú pronoun, in actual usage, speakers keep the two paradigms separate.

What of previous syncretic forms and

cachái?

Table 5 indicates that neither is significantly different from contexts where there is no prime, in accordance with our observations above. Releveled models run with a previous

tuteo as the reference level indicate that we are significantly less likely to get

tuteo following syncretic forms than following

tuteo (

β = 1.91,

p < 0.001), supporting the notion that these TAMs have lost their association with

tuteo.

Cachái is slightly different. Although overall, we are more likely to get a subsequent

voseo following another

voseo than following

cachái (

β = 1.28,

p < 0.05), the effect is not significant for the younger speakers, the main

cachái users (

β = 1.19,

p < 0.09)

, suggesting that the association between

cachái and

voseo has not been entirely lost. That is,

cachái may not be a central exemplar of the [

Verb-voseo] construction, but it does retain a link to it.

The model in

Table 5 also indicates that the priming effect is not an artefact of speakers with very high rates of

voseo, as the impact of a previous

voseo or

tuteo holds even when we take account of individual speakers’ preference by including a random intercept for speaker in the model. To further test this, we ran another model identical to the above, but with the addition of an interaction between rate of

tuteo and previous realization, and no interaction was found between a previous

voseo and rate of

tuteo (

β = 1.40,

p = 0.24), nor a previous

tuteo and rate of

tuteo (

β = 2.23,

p = 0.10).

Finally, the model in

Table 5 also tests the impact of a

tú pronoun, which favors

tuteo, as we saw in

Table 4 and

Figure 5. The model shows that the impact of a previous

tuteo is stronger than that of a

tú pronoun (with

z scores of −4.54 and −3.90 respectively). The same is not so for a previous

voseo, which has a slightly lower z score than that of the pronoun (3.10). Nevertheless, that

voseo priming holds in the presence of a

tú pronoun is evident in the fact that an interaction between the presence of a pronoun and previous

voseo fails to reach significance (

β = 0.11,

p = 0.87)—priming and pronoun presence are therefore indeed independent effects.

4.5. The Effect of Priming in Conjunction with Other Conditioning Factors

We mentioned above (

Section 3.1) that multiple factors condition the choice of

tuteo over

voseo. Up to now, we have focused on a subset of these that are directly relevant to priming. Prior work conducting regression analyses that include a full set of linguistic and social predictors has found priming not only to operate alongside these other factors, but to be the strongest predictor of this variation (

Callaghan 2020, p. 197). In order to confirm this here, we conduct one final set of analyses, including the identical dataset to that employed above (

n = 1009), and adding three new predictors: discourse type (reported speech, generic subjects, specific subjects); clause type (questions, main clause declaratives, subordinate clauses), and gender.

To determine the impact of priming while taking into account a full range of predictors, we conduct a conditional random forest analysis. Random forests are built from multiple conditional inference trees, a statistical approach that makes recursive binary splits in the data, according to the strength of the predictors in each subsequent subset of the data. Random forests measure the overall importance of each predictor included in the model by averaging the results across multiple conditional inference trees (here, 1000), each based on a randomly generated subset of the data (

Tagliamonte and Baayen 2012, pp. 159–60). Such a model “ensures that the evaluation of a variable’s importance takes into consideration its behavior in relation to other variables in its ranking” (

Schnell and Barth 2018, p. 64). The result of this analysis, obtained using the ctree() function from the “party” package for R (

Hothorn et al. 2006), is presented in

Figure 6.

As can be seen, the strongest effect is that of individual speaker, as is common in such analyses (

Tagliamonte and Baayen 2012, p. 162).

9 Priming, however, is the next strongest predictor, and is substantially stronger than any other. Age, pronoun and discourse type are ranked next, followed by gender with a marginal effect, and clause type is found not to be worth further consideration. Thus, priming is not only upheld when considering a full set of predictors but it exerts the strongest effect.

5. Conclusions

We have sought here to gain access to information about speaker representations through the study of actual usage. While perception tasks and surveys are often employed to extract attitudinal information, speakers’ own intuitions and judgements do not necessarily produce reliable data for stigmatized variables (

Sankoff 1988, pp. 145–46), as has been shown to be the case for

voseo use (

Bishop and Michnowicz 2010). Here we have demonstrated how spontaneous speech data can offer insights into speakers’ implicit understanding of constructions, examined in terms of degrees of association: because priming occurs across related constructions, the relative strength of priming provides an indication of the strength of the relationship.

The fact that speakers’ choice between

voseo and

tuteo is influenced by the previous 2sg familiar form used in the discourse provides strong evidence that they do distinguish between these paradigms; that is, they recognize, and keep separate, [

Verb-tuteo] and [

Verb-voseo] constructions. For the non-variable forms, however, we found different results. The Imperative and Preterit, despite deriving historically from

tuteo, appear to no longer be associated with it; when occurring in the previous discourse, their impact is no different from that of the absence of a prime, and it is significantly different from that of a previous

tuteo.

Cachái, on the other hand, appears not to have wholly lost its association with the [

Verb-voseo] construction, as, for young speakers at least (the main

cachái users), the impact of a previous

cachái in the discourse is not significantly different from that of a previous

voseo. This illustrates that mental representations can change over time, and that non-variable, or fossilized, forms may not be homogeneous in their degree of autonomy from their source constructions (cf.

Bybee 2006, p. 715).

As we have seen, voseo and tuteo take distinct morpho-phonological forms (e.g., estás vs. estái ‘you are-tuteo/voseo’, tienes vs. tenís ‘you have-tuteo/voseo’), and it is highly likely that this aids in keeping these paradigms apart. But we have also seen that voseo > voseo priming is not dependent on repetition of the same morpho-phonological shape, demonstrating the existence of a schematic [Verb-voseo] construction. Furthermore, the priming of voseo verb forms is retained even with a tú pronoun in the so-called mixed voseo. Thus, though overt expression of a tú pronoun favors tuteo over voseo, it does not override the impact of the previous form, indicating that [tú + Verb-voseo] is still an exemplar of the more general [Verb-voseo] construction.

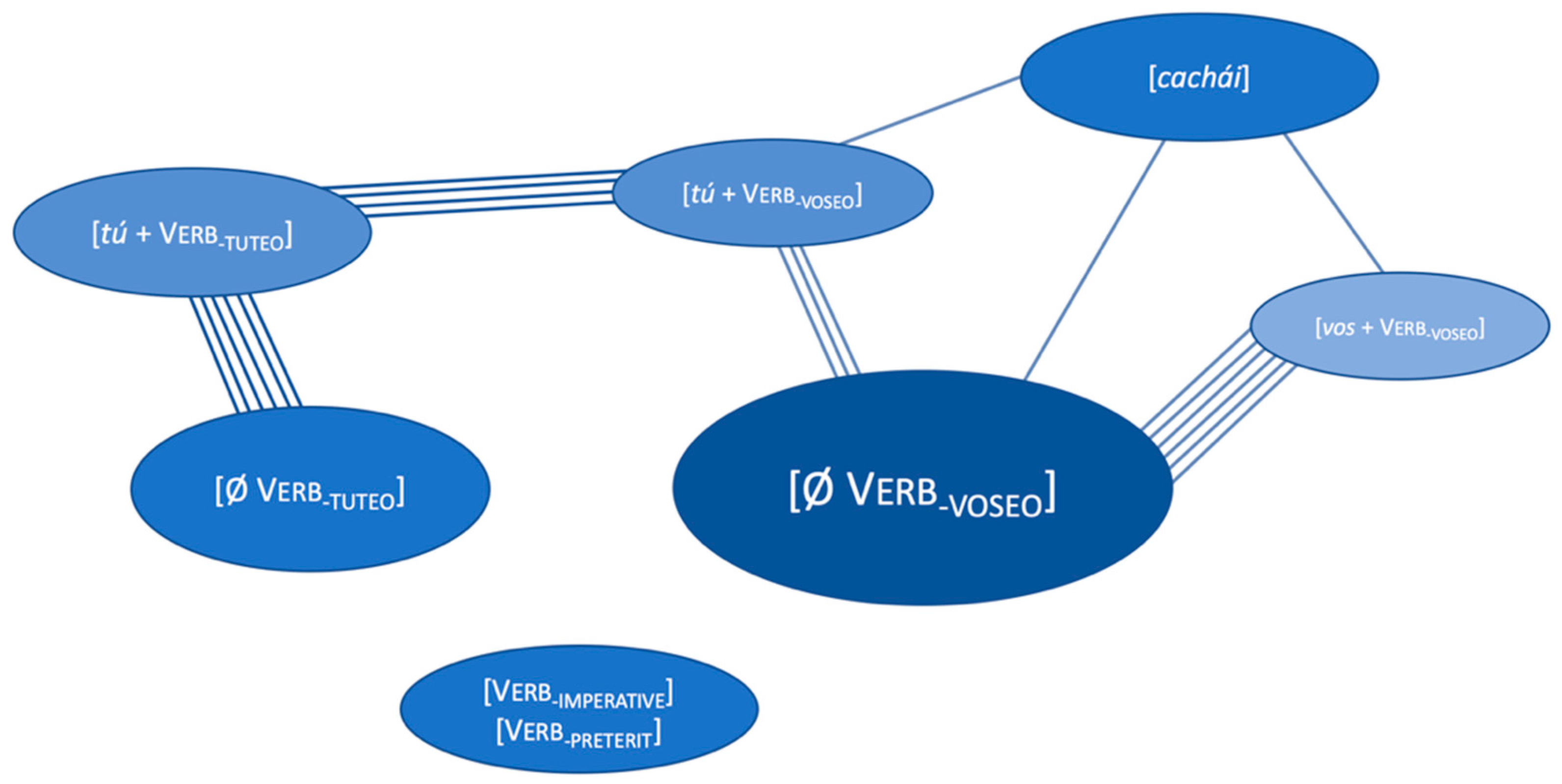

We can capture the mental representations evidenced here with the set of associations depicted in

Figure 7, with [Ø +

Verb-voseo] (the majority variant) at its center: the

tú pronoun is associated with both

tuteo and

voseo, but more strongly with the former; the

vos pronoun, though minimally used, is associated with

voseo verb forms; the syncretic Imperative and Preterit forms are associated with neither construction; and

cachái remains (weakly) associated with

voseo.

This picture does not seem to be consistent with Chileans’ metalinguistic awareness of these forms, which revolves around the vos pronoun, the subject of much commentary and stigmatization, while the tuteo/voseo verb forms pass unnoticed. Nor is it wholly consistent with much of the literature on this topic, that has assumed the existence of an underlying form for each syncretic form, and for instances with an unexpressed pronoun. The results presented here are, however, consistent with a usage-based understanding of grammar, according to which speakers do not construct their speech around abstract underlying forms, but rather as part of their constantly unfolding experience with language. Further, this can function at a highly local level, where one factor constraining variant choice is the form that has been used previously, as evidenced in structural priming.