Abstract

The rising population of heritage speakers (HS) in university courses in the US has increased the need for instructors who understand the linguistic, social, and cultural profiles of their students. Recent research has discussed the need for specialized courses and their differentiation from second-language (L2) classes, as well as the intersection between HS and language attitudes. However, prior studies have not examined HS students’ language attitudes toward the sociolinguistic background of the instructors and their effect on classroom interactions. Therefore, this study explores HS students’ overall language attitudes and perceptions of their instructors’ sociolinguistic background. In a survey, HS university students (N = 92) across the US assessed four instructor profiles along five dimensions. Results showed that students rated more favorably instructors born and raised in Latin America, followed by those from Spain. Furthermore, HS favored these two profiles over HS or L2 profiles as their course instructors. However, preferences were less marked in the online context. These findings demonstrate that to design supportive learning spaces with—rather than for—HS students, programs must first acknowledge how classroom dynamics are shaped by the perspectives brought into the learning space and by the context of the learning space itself.

1. Introduction

In the current political and sociolinguistic climate, academic institutions are making a concerted effort to reaffirm their commitment to supporting historically marginalized populations through intentional curriculum design. Considering that the Latinx community comprises the largest “minority” population in the US and that Spanish heritage speakers (HS) possess unique linguistic and educational needs (e.g., Valdés 2005), to create equitable programs, departments must listen to the experiences of the Latinx community when designing HS learning spaces.

The field of Spanish heritage language (HL) education has experienced tremendous growth since the late 1990s (Beaudrie 2018). Although this responds to the growing demand/need for programs adapted to this population’s specific needs, “the general tendency toward foreignizing Spanish as the go-to paradigm bears on a postcolonial model of education that draws from notions of linguistic purity, resulting in, among other issues, a ‘paternalistic’ instinct to fix what is perhaps misperceived as broken or deficient” (Pascual y Cabo and Prada 2018, p. 4). This tendency has led to many programs taking a “remedial” approach to designing heritage courses for heritage language learners (HLL), rather than designing programs with HLL, often lacking consideration for their needs and interests beyond linguistic competency.

Alvarez’s (2013) critique of modern Spanish departments proposed a new framework to avoid these paternalistic tendencies, including the implementation of service-based learning, a topic explored further in Section 1.1 below, and the repositioning of Spanish not as a foreign language but as one native to the US, an idea that has been supported by many others. Additionally, the author noted the ramifications of current discriminatory treatment of heritage Spanish beyond just language ability, particularly on the perception of ethnic identity. Consider the words of Anzaldúa (2007):

Chicanos who grew up speaking Chicano Spanish have internalized the belief that we speak poor Spanish. It is illegitimate, a bastard language … we use our language differences against each other. … Repeated attacks on our native tongue diminish our sense of self … So, if you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity—I am my language.(p. 81)

Spanish departments, and heritage programs in particular, must pursue the goal of recognizing and legitimizing Chicano, Boricua, and other US Latinx communities if not for the social well-being of HS students, then for the increased academic performance that comes with increased self-esteem (i.e., Lane et al. 2004). To this end, Alvarez (2013) recommended the integration of Latino studies and critical race theory into Spanish curricula in order to address these identities consciously and considerately, a recommendation which draws from heritage Spanish programs’ own origins in US civil rights movements.

Numerous authors have, indeed, argued that heritage classrooms are a space to address larger questions such as attitudes, ideologies, and identities. For example, Carreira (2000) stated that the heritage classroom represents “the single most important forum where [generalized negative attitudes toward US Spanish] can be exposed as groundless, and where the dual task of validating the regional variants represented in the classroom while teaching the standard language can be accomplished” (p. 423). Similarly, Villa (2002) argued that engaging in well-reasoned academic exchange can help diminish commonly held popular myths about US Spanish. More recently, Pascual y Cabo and Prada (2018) suggested that Spanish teaching and learning need to (1) promote bilingualism and critically address the realities of bilingual speakers, (2) shift the historical and cultural focus from foreign to local Spanish-speaking communities, (3) adopt flexible and inclusive pedagogical approaches that go beyond language, and (4) emphasize student-led learning.

Although the term HS is broadly accepted in the literature, the definitions and characterization of the term are almost as diverse as the people it intends to describe. This diversity stems from the wide spectrum of lived experiences that these speakers exhibit. Definitions of HS are approached from both linguistic and sociocultural dimensions. According to Valdés (2001), a HS is an individual “who was raised in a home where a non-English language was spoken, who speaks or at least understands the language […] and who is to some degree bilingual in that language and in English” (p. 38). This definition was adopted for the current study1.

It should also be noted that linguistic stigmatization is not unique to US Spanish-speaking communities. Polinsky (2016) aptly stated, “In the days of Benjamin Franklin, German was most likely the primary HL in the US; in modern times, it is Spanish, and it may well be Somali fifty years from now” (p. 342). At present, this study adds to an already substantial body of literature on heritage Spanish, but may, in time, be reinterpreted to serve in a new context.

These principles further motivate the rationale to differentiate HL programs from traditional second-language (L2) classrooms (e.g., Valdés et al. 1981; Pascual y Cabo and Prada 2018). However, the implementation of such programs is often challenged by the diverse attitudes, ideologies, and perspectives that emerge within such contexts. Therefore, as Pascual y Cabo and Prada (2018) argued, “it is by first acknowledging the ecological workings of learning spaces, and adopting a wide-angle stance on our resources, that optimal paths for action can be identified” (p. 11). Thus, in order to curate curricula that fully address the multifaceted needs of HS students, there is an identifiable need for researchers in linguistics and education to cooperate and collaborate, rather than continue research into the two fields separately (Polinsky 2016; Román et al. 2019).

The first step in addressing the design of these new curricula is for HS programs to understand the linguistic, social, and cultural profiles of their students and acknowledge how classroom dynamics are shaped by the perspectives brought into the learning space and by the context of the learning space itself. Thus, the specific goal of this study is to explore the interaction of the instructors’ sociocultural backgrounds and students’ language attitudes within this space. Second, we seek to examine these dynamics, particularly as they relate to classroom contexts (i.e., course type and modality) to design supportive and effective learning environments. It is to previous studies on these dynamics that we turn to next.

1.1. Attitudes and Ideologies in the Heritage Classroom

Previous studies have attempted to acknowledge the ecological workings of the learning space by focusing on various emergent factors affecting classroom dynamics. These have included, but are not limited to, faculty/administration and Spanish heritage learners’ attitudes towards HLLs’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds, student attitudes towards language maintenance and use, ideologies of Spanish in HL textbooks, HS course selection and course experience in mixed (L2/HS) classrooms, and student linguistic attitudes of Spanish in the HL classroom.

For example, Pascual y Cabo and Prada (2018) provided an overview of commonly detected instructor and administration attitudes towards students’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds and strongly argued for a new curricular approach (Redefining Spanish Teaching and Learning—“RSTL”) that shifts emphasis away from the often held belief that grammatical knowledge is the only goal of heritage courses for one that “positively expand(s) the perceptions and practices of students and teachers with regard to US Spanish (both the language(ing) and the cultural practices)” (p. 3).

Román et al. (2019) sought to gauge internal linguistic discrimination resulting from attitudes Spanish–English bilingual teachers held toward their HLL. They questioned the frequency and manner in which teachers corrected “incorrect” student utterances that reflected common constructions in US Spanish. The findings revealed that the majority of teachers promoted a purist attitude, i.e., that there is only one correct way to speak Spanish and it should never be mixed with English. The authors referred to these negative attitudes from “first-generation Spanish speakers, and Latinos in general” (p. 11) as internal linguistic discrimination. Teachers born in the US were less likely to make corrections, but still were critical of common heritage student mistakes. The authors noted that these behaviors could be a result of a lack of sociolinguistic or HL training for these instructors, and, thus, they maintain the prescriptive attitude that “Spanglish is never an option” (p. 25).

In contrast, Loza (2017) found that many instructors in heritage Spanish programs are already aware of the inequity caused by myths about language varieties. Heritage Spanish instructors in the Southwest US reported being aware of the negative stigmas around US Spanish and that they themselves did not believe the misconceptions. They accepted the use of US Spanish in the classroom and promoted its use at work in the community. Despite the instructors openly espousing “counter-hegemonic ideologies” (p. 73) in interviews, when asked to grade a written task, they resorted to simplistic conceptions of language that could not differentiate HL variation and actual error. This revealed that even well-intentioned instructors, who know they should respect heritage varieties of Spanish, often do not know how to actualize that respect and can lead to “unknowingly reinforcing and institutionally validating [standard Spanish’s] hegemony” (p. 73). The ideal curriculum, according to the author, will not designate separate domains to standard Spanish and to US Spanish, as is often the case for heritage programs; instead, it will help HLLs develop a critical awareness of language, teaching them to understand, question, and then manipulate common language ideologies for their own benefit.

Pascual y Cabo et al. (2017) examined how participating in community service-learning activities with the local Hispanic community influenced HLLs’ attitudes toward their language and culture. Prior to participation, survey data revealed that although the students had generally positive attitudes towards their language and culture, they did not feel comfortable using Spanish outside the home. After participating in community service-learning activities that prompted the use of their language in diverse and professional contexts (accompanied by course content that focused on increasing “sociolinguistic awareness and fostered positive attitudes toward the HL”), students reported increased confidence in their use of Spanish. In addition, students demonstrated a greater appreciation of how their language skills could be an asset to the community and reported an increased motivation to advance their knowledge and use of the HL. Sánchez-Muñoz (2016) found a similar increase in motivation via community involvement that emphasized the value of Spanish beyond the family. The authors concluded that community service-learning activities coupled with curriculum focused on sociolinguistic awareness can have a positive effect on language attitudes and competencies of HS students.

In a similar vein, Wilson and Martínez (2011) examined HS students’ attitudes toward language maintenance by administering a questionnaire to HS of Spanish in New Mexico. The questionnaire prompted the participants to select from a list of commonly used identity labels with which they related and to indicate on a Likert scale their agreement with statements regarding their motivation for maintaining/using Spanish. These statements were designed to address dimensions such as sentimental, instrumental, intrinsic, and communicative value. The data revealed that students overwhelmingly identified as Hispanic first and foremost, but the majority also selected additional labels of identity such as American, Latino, Spanish, and Mexican, amongst others, providing “evidence that identity is fluid and dynamic” (Gonzales 2005). Furthermore, students indicated that their motivations for maintaining their language use were, in order of dimension, instrumental, intrinsic value, sentimental, and communication, indicating that they valued Spanish mainly for professional and academic advantages.

In an extension of the Wilson and Martínez (2011) study, Henderson et al. (2020) investigated the correlations of course level, gender, and ethnic identity labels along the same attitudinal dimensions (Instrumental, Sentimental, Communication, and Value). Using the same survey tools as Wilson and Martínez (2011), they identified that beginner- and advanced-level students presented different correlations to language attitudes even though they reported similar ethnic identities. These correlations varied significantly by ethnic identity, course level, and gender. “First-semester students who self-identified as ‘Mexican American,’ ‘Hispanic,’ and ‘Spanish’ rated the Value dimension higher than peers who did not claim those labels. ‘Anglo’ correlated negatively with both the Value and Communicative dimensions. Fourth-semester students who self-identified as ‘Latino/a’ had positive attitudes in the Sentimental, Instrumental, and Communicative dimensions. ‘Native American’ and ‘Spanish’ correlated negatively with Sentimental while ‘American’ correlated negatively with Instrumental.” (p. 27). With regard to course level, the advanced-level students held more favorable language attitudes than their beginner-level peers. However, regardless of level, females demonstrated more positive attitudes than males. These findings suggest that when evaluating and developing HL programs, it is important to consider the specific ethnic identity and background of the HS students as well as their current course level to identify the affective and motivational factors influencing the learning space.

Sánchez-Muñoz (2016) studied HS students’ attitudes toward heritage Spanish along with their perceived ability and confidence using Spanish before and after taking their first heritage Spanish course. Unsurprisingly, students’ ratings increased in all four aspects (i.e., oral, listening, reading, and writing) by the end of the course. Most notable was the increase in writing ability and confidence, which is often a primary motivation for HS students to enroll in heritage courses since they lack formal writing experience in the HL. Perhaps due to different geographical contexts, the qualitative results of this study contradict the original findings of Wilson and Martínez (2011); students expressed a strong desire to preserve their Spanish in order to maintain their Latinx identity and to avoid discrimination by other Latinxs for a lack of language skills. Students’ reflections revealed they saw little professional value in speaking Spanish, instead viewing it as the language of “the menial workers and the undocumented” (p. 214). Despite this social stigma, students were more motivated to continue their Spanish studies toward the end of the course, as their confidence had increased, and they had new/renewed interest in the social value of the language. The author concludes that heritage classrooms possess a healing power to improve students’ linguistic confidence and resolve internalized negative views toward their HL.

Ideologies beyond those of the faculty or students, such as those that emerge in HL textbooks, have also been examined. Leeman and Martínez (2007) evaluated the discourse present in prefaces and introductions to Spanish for HS textbooks published between 1970 and 2000. Their analysis revealed that the “intertextual discourse emerging in Spanish HL textbooks correlates with broader ideologies regarding the societal role of the university, the positioning of ethnic studies programs, and the portrayal of cultural and linguistic diversity within academia and society at large.” (p. 1). Interestingly, they highlighted that there was a transition from the 1970s–1980s’ focus on access, inclusion, and representation for the minority Spanish language to a focus on economic competitiveness and globalization in the 1990s. They discussed how this transition from student identity to commodification had often contradictory implications. Most relevant to this current discussion is that it appears that the pendulum is beginning to swing back in the other direction with an intentional emphasis on identity as a way to restore equity amongst HLLs who have internalized many of these conflicting ideologies regarding the prestige and value of their heritage languages and cultures, which have not been adequately addressed in the “tendency toward foreignizing Spanish as the go-to paradigm” of many university language programs, as extensively discussed by Pascual y Cabo and Prada (2018).

Accordingly, Potowski (2002) uncovered that HS students largely enrolled in traditional language classes. That is, rather than enrolling in tailored HL classes, they believed that their language skills were inadequate for a heritage class. Moreover, these same students reported feeling inferior to the non-heritage second-language learners who had more prior exposure and instruction in formal varieties of Spanish and linguistic terminology. Potowski (2002) cites that “some students interpret corrective feedback from their instructors as messages that their Spanish is substandard (which some of them unfortunately believed even before they entered the class). While nonnative Spanish students are undoubtedly corrected often by TAs, bilingual students experience ‘correction’ differently because it is tied in with their personal and cultural history” (p. 8). It is important to mention that there are other studies, such as Ducar (2008), which show that HLLs in their study actually desired corrective feedback. Therefore, the method by which corrective feedback is given is crucial, insofar that it requires a sensitivity to the students’ background and identity as a HS of Spanish in the US context.

Moreover, HS students appear to actually experience more anxiety in traditional language courses than in heritage courses. Prada et al. (2020) examined the phenomenon of HL Anxiety by comparing the anxieties of HS students in traditional language classes and those enrolled in classes specifically designed for HS. The students in heritage courses overwhelmingly reported lower levels of anxiety in the classroom, which the authors attribute to five themes. First among those themes was the disposition of the instructor toward heritage varieties of Spanish. Students felt previous language instructors looked at their home language with disdain, coinciding with the discussion above. One student even remarked “yo era el ejemplo de lo que está mal en español” (“I was an example of bad Spanish,” p. 104). Thus, previous instructors’ attitudes supported societal beliefs of heritage Spanish as “broken” or “deficient”, only deepening students’ feeling of inadequacy. Conversely, in the heritage course, the instructor recognized and expressed interest in the students’ language, and, accordingly, students felt that their language was validated, and their anxiety decreased. The study also cited the inherently more content-focused approach of heritage courses (rather than grammar-focused as in traditional classes) as another contributing factor to reduced anxiety. In traditional classes, the emphasis on grammar and correct orthography can be demotivating for HS students. For example, students lamented losing many points on assignments for missing accent marks and the silent letter h despite being able to produce the language aloud correctly. Alvarez (2013) expands on this phenomenon of “accent-based terrorism” (p. 140), citing students losing points for leaving accents off their own name. In the heritage course, however, the students were able to use the language to discuss culturally relevant topics, which encouraged participation and made the class less threatening. From these findings, the authors were able to conclude that heritage courses are a better option than traditional courses when it comes to mitigating HL Anxiety.

This section has reviewed the diverse attitudes and ideologies held by both teachers and students in the HL classroom and how they contribute to the construction of a classroom context to either invalidate or support the HL. Some instructors assert a more traditional, unsupportive stance toward the HL, as attested in Román et al. (2019), while others—trained in sociolinguistics and/or heritage pedagogy—acknowledge the problems of inequity (Loza 2017). Though these sympathetic instructors may not address the HL flawlessly, even their positive disposition toward the language can benefit the class dynamic by reducing HS’ anxiety (Prada et al. 2020). Likewise, it is essential to understand the classroom from the HS’ perspective and their views on the HL. While Sánchez-Muñoz (2016) partially contradicts Wilson and Martínez (2011), the findings correlate well with those of Henderson et al. (2020); together, these studies strongly suggest that the intrinsic value of Spanish, i.e., its connection to family culture and Latinx identity, is the primary reason for most HS to pursue further education in the language. We touched on how curricular design, whether focused more on grammar or on content, treats heritage Spanish. Next, we move to further discuss the impact of classroom design, namely the distinction between classroom modality, either online or face-to-face, especially in regard to social capital that students prioritize.

1.2. The Effect of Context and Modality

As discussed above, certain contexts have been found to be more effective for heritage instruction, especially those that minimize student anxiety and capitalize on the learner’s current knowledge to interact in meaning-based activities through which they can acquire additional grammar and vocabulary during discourse-level activities (Beaudrie 2020). These approaches include content-based language education, genre-based pedagogy, project-based learning, and experiential learning (Carreira 2016; Parra et al. 2018; Beaudrie 2020). Furthermore, it has been found that HS students enrolled in upper-level courses, courses that are typically focused on particular content rather than the acquisition of the language, hold more favorable language attitudes (Henderson et al. 2020), which contributes to a more positive evaluation of such classes. Henderson et al. (2020) suggest that the positive attitudes among higher course level students may be due to increased opportunities to use the language within the heritage community which lead to a stronger sense of Latinx identity and pride. The authors argue that Spanish Heritage Language programs that encourage cultural interactions with the heritage community and real-world communication foster the development of positive attitudes towards the use of Spanish in the public sphere and in the classroom. Additionally, it is also likely that shifting away from the focus on language as the object of study in the lower-level courses to language as a vehicle of study in the advanced-level courses, minimizes the insecurities the students may have about their linguistic competencies since they are no longer scrutinized under the microscope.

Additionally relevant, and particularly timely, is the effect of modality. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic when this study was conducted, the vast majority of university language courses were taught in a face-to-face (F2F) environment. Many adopted a “flipped-design” approach in which much of the direct instruction of grammatical or vocabulary topics occurred outside of the classroom via digital presentations. Although this flipped approach was referred to as a hybrid model of course delivery, it still depended on a large F2F component that focused on real-time communicative activities with the instructor or peers. The least common model for language course delivery type was the 100% online format. Among these exclusively online courses, both asynchronous and synchronous models were adopted; however, those that had synchronous requirements typically met for less “real-time” than their F2F counterparts. Previous research, and this current study, have taken a general dichotomous approach to comparing these two modalities (F2F and online) without considering the spectrum of nuanced model approaches (i.e., hybrid, hyflex, asynchronous, synchronous, etc.) that have emerged and have been more broadly adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Within this simplified online versus F2F dichotomy, Coryell and Clark (2009) tested the hypothesis that HS students would feel less anxious in an online environment that did not require interacting in person (Beauvois 1998; Kelm 1992; Roed 2003). The authors interviewed self-assessed anxious HS students enrolled in online Spanish courses, but found that rather than feeling less anxious, the design of the asynchronous course reinforced the idea that language was performance and that one needed to get it “right” before they could properly engage in conversation and participate meaningfully within the community. On the other hand, the learners expressed that the online environment was “a safer space for them to wrestle with feelings of linguistic and cultural incompetence” (p. 465). The authors suggest that to counter this perception of one “right way” of using a language, online programs would benefit from offering students opportunities to practice with native speakers, experts, and other students “to develop the intercultural, pragmatic, and grammatical complexities of language in context”. Such opportunities would provide a “supportive environment that connects more appropriately with their learning needs and expectations,” (p. 501).

In order to further assess the effects of modality on language education, Torres (2020) set out to examine how interactions on digital platforms affect the production of written texts. Results show that interactions in the online context led to a higher production of syntactic coordination, which is associated with lower proficiency levels, compared to the more syntactically complex structures produced during the F2F interactions. More importantly, Torres (2020) found that HS students in fact considered communication in the online modality to be more difficult than in the F2F modality. According to the author, this extra layer of complexity may have deeper implications in HL online education, since the students may be allocating their cognitive and linguistic resources not only to the task at hand (in this case, a collaborative writing task) but also to navigating the online format.

Although not specifically evaluating HS students, Marull and Kumar (2020) examined the effect of centering an online language program around telecollaborative coaching sessions with native speakers. The online courses were mixed L2/HS classes, and each week, students met in small groups via Zoom for conversation practice with native speakers of the language located across Latin America and Spain through the platform LinguaMeeting (www.linguameeting.com (accessed on 1 September 2021). A survey of over 300 students found that “meeting with a native speaker reduced their sense of isolation, facilitated a friendship with the coach, provided a preferred way to learn about Spanish culture, offered an authentic opportunity to practice language skills with a native speaker which improved their opinion of the coach’s home country, and improved the overall quality of the online course (mean ratings greater than 8.4 out of 10 in all categories)” (p. 633). Additionally relevant to the current study is that the students rated over 80 on a Likert Scale (0–100) that the coaching sessions helped them improve “anxiety about speaking Spanish with a native Speaker” and helped them “to apply classroom skills to a ‘real-life’ context”. Although the data did not separate the HS students from the L2 students, the findings of this study align positively with the conclusions that Coryell and Clark (2009) suggested above and indicate a positive direction of study for both HS and L2 students in this modality.

Obviously, HS students have different needs than L2 learners, but HS students themselves are variable in their needs as well. Henshaw (2016a) explored how online modalities can address these individual needs. First, the author suggests online courses allow for more individualization to meet each student’s needs specifically, which can be especially useful in mixed L2/HS classes. Second, online courses readily emphasize reading and writing, and these literacy skills are often what HS students need because they lack written exposure to the HL. Third, online courses may be less anxiety-inducing for two reasons: (1) there is no speaking in front of the whole class so there is no performance anxiety and (2) students can review the online material as much as needed without facing shame from their peers. However, Henshaw (2016b) noted several possible pitfalls in instrumenting online heritage courses. The rigidity of computer-graded assignments may perpetuate feelings of inferiority in HS students by promoting the idea that there is only one “right-way” to use Spanish, especially when answers are marked as incorrect with no explanation provided. Additionally, online courses may hinder a sense of classroom community, leaving students feeling isolated, an especially weighty cost for HS students who come to the heritage classroom seeking to connect with fellow HS (consider though that an approach such as that described above by Marull and Kumar (2020) would remediate many of these concerns). Lastly, Henshaw detailed the overall lack of HL-oriented online course materials, which poses a challenge for accurately accounting the benefits of this form of instruction.

1.3. The Current Study

The above studies highlight the dynamic nature of the language classroom for the HS. That is, HS classroom contexts can either reinforce negative attitudes and ideologies or facilitate a shift toward positive evaluation of the heritage language and culture. Moreover, we have highlighted how these dynamics might play out differently across various contexts (i.e., course type) and modalities (i.e., online versus F2F).

Along with course level, Wilson and Martínez (2011) and Henderson et al. (2020) studied the effect of ethnic background on HS student attitudes toward several dimensions of language values. Though recognizing the influence of ethnic background in the classroom, their study only examined the students’ background and did not address how the ethnic background of the instructor correlated with student attitudes towards them and the learning environment, let alone how such interactions would be modulated by course level or modality. In fact, to date, few studies have addressed the attitudes held by HS students themselves toward the instructor of these courses. More specifically, in this current study, we seek to explore how HS students perceive and respond to having an instructor who comes from a similar or different sociolinguistic background. We are particularly interested in how students perceive and evaluate their instructors across the dimensions of content and linguistic knowledge, shared cultural background, respect towards the instructors’ linguistic background, and expectations regarding sensitive feedback. These dimensions are particularly important, as elucidated by Beaudrie (2020):

In the affective realm, Spanish HL students consistently have a higher integrative motivation to regain or further develop their heritage language, but at the same time they have unique needs such as low linguistic self-esteem (Gonzalez 2011), ethnic identity issues (He 2006), and negative attitudes toward their own linguistic varieties (Beaudrie and Ducar 2005; Martínez 2003). Their typical motivations for taking Spanish courses are to reconnect with their cultural heritage; to learn about the history, values, and traditions of their own and other Hispanic cultures; and to connect with other members of the heritage language community (Beaudrie et al. 2009; Carreira and Kagan 2011).

In the current study, we explore HS students’ attitudes toward the sociolinguistic background of their language instructors and their perceived support in the HL. Moreover, we extend the studies of Wilson and Martínez (2011) and Henderson et al. (2020) to consider specific classroom types within the dichotomous lower-level/upper-level split (i.e., language versus content course), as well as modality (i.e., F2F versus online) to account for how various classroom contexts interact with instructor backgrounds and students’ language attitudes.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

In order to address the above goals, the following specific research questions were formulated.

RQ1. How do HS students perceive four different instructor profiles along the dimensions of Content Knowledge, Grammatical Knowledge, Shared Cultural Background, Respect for the Instructor’s Linguistic Background, and Ability to Provide Sensitive Feedback? What differences exist, if any, between the student ratings across the four instructor groups?

RQ2. What preferences do HS students have regarding their instructors’ sociolinguistic background across course contexts?

RQ3. Does modality, specifically online2 or face-to-face, interact with the HS students’ perceptions and preferences?

Thus, the goal of this study is twofold. First, we aim to explore HS students’ attitudes toward their instructors’ sociolinguistic backgrounds. Second, we further examine these dispositions, particularly as they relate to classroom modality (i.e., face-to-face and online courses). Highlighting the interplay between student attitudes and these learning spaces, we will discuss their impact on classroom dynamics and provide practical implications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In order to study the HS student experience in the Spanish classroom, an online survey3 was designed and distributed among Spanish-speaking Latinx university HS students attending institutions in the United States. Participation was anonymous and voluntary, and the survey was completed using Qualtrics software, Version 20184. As compensation, every 20th participant received a USD 20 Amazon Gift Card, if they chose to share their email. This survey was designed for a larger research project and only a subset of the data collected using this instrument was employed to answer the research questions in the present study.

To begin, participants first signed an informed consent and then read Valdés’s (2005)5 definition of HS and were asked to self-identify whether they fit the characteristics of a HS. Those who self-identified as a HS continued to the next section of the survey. Participation was discontinued, however, for those who did not meet the criteria of the survey6.

Regarding the survey design, questions were divided into six sections. First, Section A comprised 30 questions that explored the participants’ linguistic background, specifically: languages by order of acquisition, language dominance, exposure to each language, self-rated proficiency7, and language use in home, school, and community settings. Section B consisted of five continuous Likert-scale questions regarding the participants’ perceptions and attitudes towards four instructor profiles and two course delivery modes (i.e., online versus F2F). Sections C, D, and E consisted of a total of 25 questions that included continuous Likert-scale and multiple-choice responses regarding their previous experiences with different course types (i.e., Spanish as a second language, Spanish as a HL, and content courses in Spanish) and course delivery modes, as well as their preferences regarding instructor profile when taking a Spanish course. Lastly, Section F contained four open-ended qualitative questions8 that gave the participants an opportunity to expand their responses and provide additional relevant information about their college experience as a heritage student taking courses in a Spanish department. Descriptions for instructors’ backgrounds, classroom settings, and course type were provided in the survey and read as follows:

- Instructor profile descriptions9:

- Instructor profile 1: This instructor is a Spanish speaker who was born and raised in Spain, completed most of their education in Spanish in Spain, and came to the US as an adult. He/she is now pursuing a PhD in Literature or Spanish Linguistics and teaches courses in a Spanish department at a US college.

- Instructor profile 2: This instructor is a Spanish speaker who was born and raised in a Latin American Spanish-speaking country, completed most of their education in Spanish in their country of origin, and came to the US as an adult. He/she is now pursuing a PhD in Literature or Spanish Linguistics and teaches courses in a Spanish department at a US college.

- Instructor profile 3: This instructor is a Spanish speaker who was born and raised in the US, identifies as a Heritage Spanish Speaker, and completed their education mostly in the US and in English. He/she is now pursuing a PhD in Literature or Spanish Linguistics and teaches courses in a Spanish department at a US college.

- Instructor profile 4: This instructor is an English speaker who was born and raised in the US, completed their education mostly in the US, learned Spanish as a second language in school, and lived in a Spanish-speaking country for an extended period of time (between 6 months and 5 years). He/she is now pursuing a PhD in Literature or Spanish Linguistics and teaches courses in a Spanish department at a US college.

- Course Delivery

- Face-to-Face courses: Teaching is conducted in a classroom at a set time on specific dates. Students must physically attend the class. Traditional college classes are usually F2F.

- Online courses: Learning materials are available in their entirety through an online platform. Usually, the students can log in at any time and complete their assignments at their own pace as long as they meet the set deadlines. Courses taken in their entirety on Sakai, Blackboard, eCollege, Canvas, etc., are online courses.

- Course Type

- Spanish as a Second Language courses: Courses geared towards improving all aspects of the Spanish language (reading, writing, listening, speaking, vocabulary, fluency, cultural awareness). These courses may mix students who are learning Spanish as a second language and heritage Spanish speakers. For instance, Spanish I, Spanish II, Advanced Spanish Grammar and Composition, Oral Spanish.

- Spanish as a Heritage Language courses: Courses geared towards improving mostly written Spanish abilities, mastering different registers in spoken and written Spanish, expanding cultural knowledge, and increasing confidence in using the language. Only HS may take these courses. Examples are Spanish for Native Speakers, Spanish for Heritage Speakers, Spanish for Bilinguals, Culture and Composition for Heritage Speakers.

- Content courses taught in Spanish: Courses that specialize in a topic such as literature, linguistics, translation/interpreting, or cultural analysis and are taught in Spanish. Examples of these courses are Introduction to Hispanic Literature, Spanish Linguistics, Introduction to Translation, Medical Interpreting, or Spanish Culture.

2.2. Participants

A total of N = 92 students responded to the survey. All participants were HS of Spanish as defined by Valdés (2001, 2005). The majority (72%) reported being born in the United States, whereas 26.8% reported being born in a Spanish-speaking country including Colombia, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Cuba, Peru, and Puerto Rico. The participants were attending institutions in New Jersey (15.2%), Florida (35.9%), Texas (44.6%), and Other (4.3%) and were enrolled in Spanish courses of different levels at the time of participation (75% female; 25% male). The self-declared language of dominance was English for 80.4% of the respondents, Spanish for 18.5%, and Other for 1.1%. Spanish was reported to be the first language for 61.3% of the participants, English for 37.6%10, and Both Equally for 1.1%. Participants reported that 51.2% had taken at least one Spanish course taught by a native speaker (Spain/Latin America), 40.2% had taken at least one Spanish course taught by a HS, and 37% had taken at least one Spanish course taught by an L2 Spanish speaker. See Table 1 below for complete descriptive statistics of the participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the participants.

3. Results

In this section, statistical analyses employed to answer the research questions are presented. These analyses and their implications will be discussed in Section 4.

3.1. Participants’ Ratings of Instructor Profiles

The survey in the present study elicited the HS students’ perceptions for the four different instructor profiles along five dimensions: Content Knowledge, Grammatical Knowledge, Shared Cultural Background, Respect for the Instructor’s Linguistic Background, and Ability to Provide Sensitive Feedback. These perceptions were measured using a sliding 1 through 5 Likert scale, with 1 being “Strongly disagree” and 5 being “Strongly agree”.

First, to establish which statistical tests needed to be run to find out what differences exist, if any, across the four instructor type groups, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of normality was conducted. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test identified the absence of normal distribution of the continuous variables, which therefore required non-parametric tests. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare the student ratings11. To calculate pairwise comparisons, the paired samples Wilcoxon test was used.

Table 2 below presents a summary of findings for each of the five dimensions. The Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed statistically significant differences for all five dimensions. Subsequent subsections present non-parametric multiple comparisons to identify differences among the four instructor profiles.

Table 2.

Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric tests for ratings of instructor profiles.

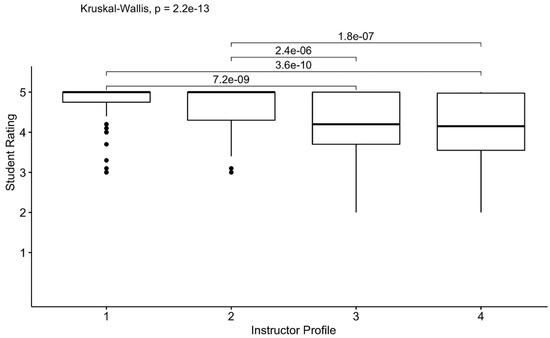

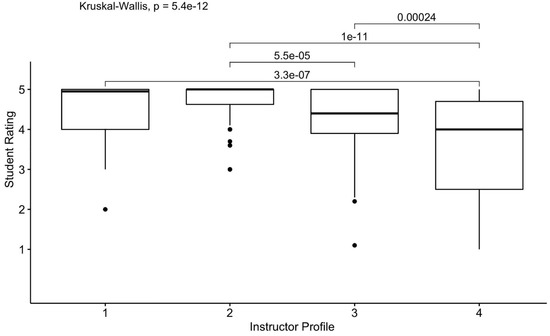

3.1.1. Content Knowledge

First, participants were instructed to use a sliding 1 through 5 Likert scale to indicate to which extent they agreed with each instructor profile’s content knowledge: He/she possesses strong content knowledge in Spanish linguistics and/or literature). Profile 1 had the highest mean rating (M = 4.76, SD = 0.49), followed by Profile 2 (M = 4.69, SD = 0.49), Profile 3 (M = 4.17, SD = 0.812), and Profile 4 (M =4.11, SD = 0.79).

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings on content knowledge, H(3) = 62.02, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.16. The median and interquartile (IQR) of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 5.0 (IQR = 0.25), 5.0 (IQR = 0.7), 4.2 (IQR = 1.3), and 4.15 (IQR = 1.43), respectively. A post hoc analysis using paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 3 regarding content knowledge (z = −5.79, p < 0.001), as well as between Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −6.27, p < 0.001), Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −4.71, p < 0.001), and Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −5.22, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −1.39, p = 0.952) and 3 and 4 (z = −0.56, p = 0.952). See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Content knowledge ratings according to instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

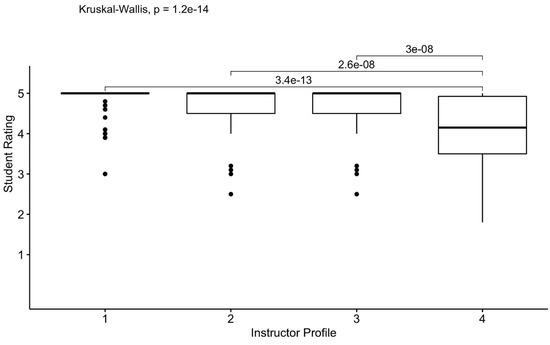

3.1.2. Respect for the Instructor’s Linguistic Background

Next, participants used a sliding 1 through 5 Likert scale to indicate the extent to which they agreed for each of the instructor profiles: I respect his/her Spanish. For this question, students assigned higher scores, on average, to Profile 2 (M = 4.85, SD = 0.42), followed by Profile 1 (M = 4.83, SD = 0.42), Profile 3 (M = 4.57, SD = 0.61), and Profile 4 (M = 4.39, SD = 0.78).

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings regarding their respect for the instructors’ linguistic background, H(3) = 37.98, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.1. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 5.0 (IQR = 0.0), 5.0 (0), 5.0 (IQR = 0.8), and 4.8 (IQR = 1.0), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 3 regarding their respect for Spanish (z = −5.79, p < 0.001), as well as between Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −6.27, p < 0.001), Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −4.71, p < 0.001), and Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −5.22, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −1.39, p = 1.0) and 3 and 4 (z = −0.56, p = 1.0). See Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Respect for Spanish ratings according to instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

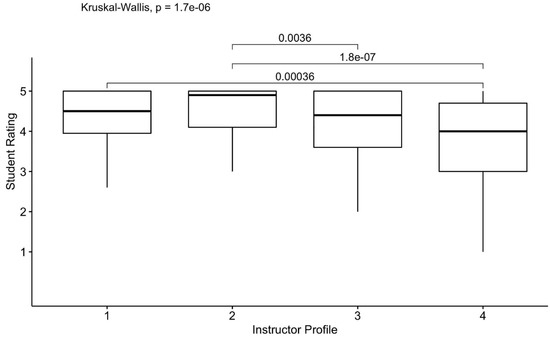

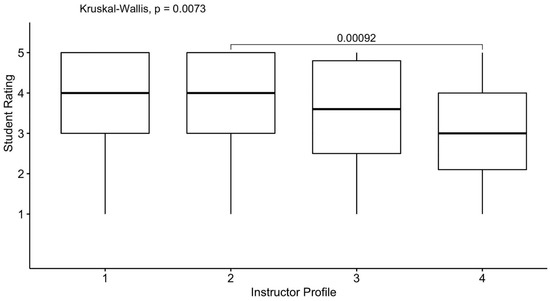

3.1.3. Grammatical Knowledge

The third question concerned their evaluation of each instructor’s grammatical knowledge (i.e., He/she possesses strong grammatical knowledge in Spanish). For this statement, Profile 1, on average, received the highest mean rating (M = 4.84, SD = 0.41), closely followed by Profile 3 (M = 4.70, SD = 0.54) and Profile 2 (M = 4.69, SD = 0.53). However, Profile 4 (M = 4.08, SD = 0.84), received the lowest mean rating, on average.

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that profile type significantly affected student ratings regarding their attitude towards their instructors’ grammatical knowledge, H(3) = 62.02, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.18. The median IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 5.0 (IQR = 0.0), 5.0 (IQR = 0.5), 5.0 (IQR = 0.5), and 4.15 (IQR = 1.42), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −7.28, p < 0.001), Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −5.57, p < 0.001), and Profiles 3 and 4 (z = −5.54, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −2.27, p = 0.14), Profiles 1 and 3 (z = −2.26, p = 0.15), and Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −0.02, p = 1.0). See Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Grammatical Knowledge ratings according to instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

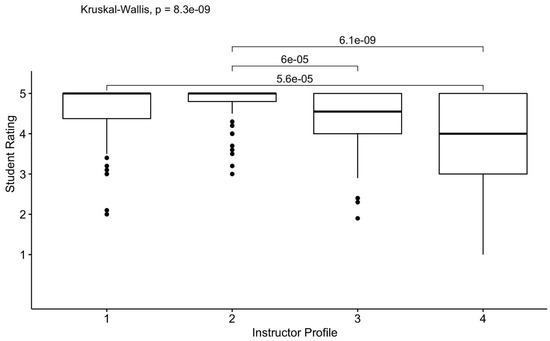

3.1.4. Shared Cultural Knowledge

The fourth question students responded to concerned shared cultural knowledge (i.e., He/she and I would have some similar cultural knowledge and experiences). For this statement, Profile 2, on average, received the highest mean rating (M = 4.22, SD = 0.95), followed by Profile 3 (M = 4.20, SD = 1.05), Profile 4 (M = 3.44, SD = 1.16) and Profile 1 (M = 3.21, SD = 1.18).

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings regarding perceived shared cultural knowledge, H(3) = 55.32, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.14. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 3.5 (IQR = 2.0), 4.3 (IQR = 1.0), 4.7 (IQR = 1.3), and 3.9 (IQR = 1.4), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −5.84, p < 0.001), Profiles 1 and 3 (z = −5.45, p < 0.001), Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −4.86, p < 0.001), and Profiles 3 and 4 (z = −4.64, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −1.15, p = 1.0) and Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −0.27, p = 1.0). See Figure 4 below.

Figure 4.

Shared Cultural Knowledge ratings according to instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

3.1.5. Sensitive Feedback

Next, participants responded to the statement on instructors’ ability to provide sensitive feedback (i.e., I think he/she would give culturally sensitive feedback to Spanish heritage students). Profile 2 received the highest mean rating (M = 4.53, SD = 0.58), followed by Profile 1 (M = 4.33, SD = 0.71). Profile 3 (M = 4.16, SD = 0.85) and Profile 4 (M = 3.78, SD = 1.00) received the lowest ratings, on average.

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings regarding perceived ability to provide culturally sensitive feedback, H(3) = 29.60, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.07. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 4.5 (IQR = 1.05), 4.9 (IQR = 0.98), 4.4 (IQR = 1.4), and 4 (IQR = 1.7), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −3.57, p < 0.001), Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −5.22, p < 0.001), and Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −2.88, p = 0.004). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −1.85, p = 0.39), Profiles 1 and 3 (z = −1.21, p = 1.0), and Profiles 3 and 4 (z = −2.35, p = 0.12). See Figure 5 below.

Figure 5.

Sensitive Feedback ratings according to instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

3.2. Participants’ Preferences on Instructor Profiles

Next, the survey elicited HS students’ preferences on instructor profiles when taking three different course types (Spanish Language, Heritage, Content) across two modalities (i.e., F2F and Online). These preferences were measured using a sliding 1 through 5 Likert scale, with 1 being “Extremely unlikely” and 5 being “Extremely likely”.

Table 3 below presents a summary of findings for each of the six combinations. The Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed statistically significant differences for all combinations except for Online L2 Spanish. Subsequent subsections present non-parametric multiple comparisons to identify differences among the four instructor profiles.

Table 3.

Kruskal–Wallis Non-parametric tests for instructor preference for each class type combination.

3.2.1. L2 Spanish Courses: F2F versus Online

For F2F L2 Spanish, students assigned higher scores, on average, to Profile 2 (M = 4.77, SD = 0.46), followed by Profile 1 (M = 4.56, SD = 0.70), Profile 3 (M = 4.35, SD = 0.80), and Profile 4 (M = 3.82, SD = 1.18).

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings regarding their preferences when taking a F2F L2 Spanish course, H(3) = 40.52, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.1. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 5.0 (IQR = 0.63), 5.0 (IQR = 0.2), 4.55 (IQR = 1.0), and 4 (IQR = 2.0), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −4.03, p < 0.001), as well as between Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −4.01, p < 0.001), and Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −5.81, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −2.41, p = 0.096), Profiles 1 and 3 (z = −1.80, p = 0.43), and 3 and 4 (z = −2.70, p = 0.04). See Figure 6 below.

Figure 6.

Ratings according to F2F Spanish course type and instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

Next, regarding Online L2 Spanish courses, the participants exhibited similar behaviors. That is, Profile 2 on average, was assigned higher ratings (M = 3.45, SD = 1.41), followed by Profile 1 (M = 3.29, SD = 1.49), Profile 3 (M = 3.18, SD = 1.38), and Profile 4 (M = 3.01, SD = 1.42). There also appears to be mild variation in responses, indicated by each category’s standard deviation.

However, a Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type did not significantly affect student ratings regarding their preferences for this course type and modality, H(3) = 3.96, p = 0.27; η2 = 0.003. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 3.4 (IQR = 3.1), 3.7 (IQR = 2.9), 3.4 (IQR = 2.4), and 3 (IQR = 2.42), respectively. See Figure 7 below.

Figure 7.

Ratings according to Online Spanish course type and instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

3.2.2. Heritage Spanish Courses: F2F versus Online

This section explores students’ preference toward taking heritage Spanish courses F2F versus online, with respect to instructors 1 through 4. For F2F Heritage Spanish, students assigned higher scores, on average, to Profile 2 (M = 4.71, SD = 0.52), followed by Profile 1 (M = 4.50, SD = 0.68), Profile 3 (M = 4.26, SD = 0.83), and Profile 4 (M = 3.56, SD = 1.21).

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings in regard to their preferences when taking a F2F Heritage Spanish course, H(3) = 62.02, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.14. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 4.95 (IQR = 1), 5.0 (IQR = 0.38), 4.4 (IQR = 1.1), and 4.0 (IQR = 2.2), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −5.11, p < 0.001), as well as between Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −4.04, p < 0.001), Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −6.81, p < 0.001), and Profiles 3 and 4 (z = −4.19, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −2.39, p = 0.103) and 1 and 3 (z = −1.71, p = 0.452). See Figure 8 below.

Figure 8.

Ratings according to Face-to-Face Heritage Spanish course type and instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

For Online Heritage Spanish courses, similar preferences were exhibited, with Profile 2 (M = 3.78, SD = 1.31) receiving the highest scores, on average, followed by Profile 1 (M = 3.59, SD = 1.35), Profile 3 (M = 3.42, SD = 1.31), and Profile 4 (M = 3.06, SD = 1.31). Again, mild variation across responses was exhibited, denoted by each profile’s standard deviation.

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings regarding their preferences when taking an Online Heritage Spanish course, H(3) = 62.02, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.02. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 4.0 (IQR = 2), 4.0 (IQR = 2), 3.6 (IQR = 2.3), and 3.0 (IQR = 1.9), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There was a significant difference between the ratings assigned to Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −1.80, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −0.82, p = 1.0), Profiles 1 and 3 (z = −0.96, p = 1.0), Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −2.56, p = 0.09), Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −1.80, p = 0.43), and 3 and 4 (z = −1.51, p = 0.79). See Figure 9 below.

Figure 9.

Ratings according to Online Heritage Spanish course type and instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

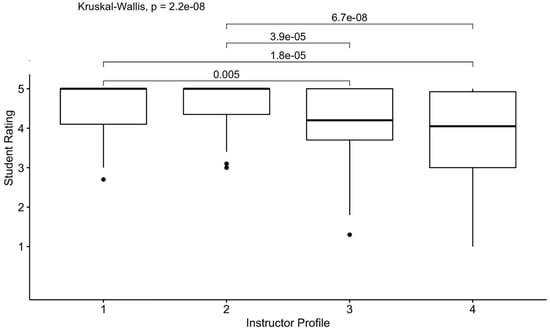

3.2.3. Content Courses: F2F versus Online

This section explores students’ modality preference toward taking a content course, with respect to instructors 1 through 4. In the case of F2F Content in Spanish, Profile 2 received the highest rating, on average (M = 4.66, SD = 0.58), followed by Profile 1 (M = 4.53, SD = 0.68), Profile 3 (M = 4.16, SD = 0.87), and Profile 4 (M = 3.85, SD = 1.07).

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings in regard to their preferences when taking a F2F Content course in Spanish, H(3) = 38.49, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.1. The Median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 5.0 (IQR = 0.9), 5.0 (IQR = 0.65), 4.2 (IQR = 1.3), and 4.05 (IQR = 1.92), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were significant differences between the ratings assigned to Profiles 1 and 3 (z = −2.81, p = 0.005), Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −4.11, p < 0.001), Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −4.11, p < 0.001), and Profiles 2 and 4 (z = −5.40, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −1.31, p = 0.19) and Profiles 3 and 4 (z = −1.72, p = 0.52). See Figure 10 below.

Figure 10.

Ratings according to F2F content course type and instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

For Online Content in Spanish, a similar trend occurred. Profile 2 received the highest rating (M = 3.80, SD = 1.33), followed by Profile 1 (M = 3.59, SD = 1.40), Profile 3 (M = 3.48, SD = 1.26), and Profile 4 (M = 3.16, SD = 1.33).

A Kruskal–Wallis test showed that instructor type significantly affected student ratings regarding their preferences when taking an Online Content course in Spanish, H(3) = 9.70, p = 0.003; η2 = 0.02. The median and IQR of ratings for Profiles 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 3.8 (IQR = 2.05), 4.15 (IQR = 2.0), 3.7 (IQR = 1.58), and 3.4 (IQR = 2.0), respectively. A post hoc analysis using a paired samples Wilcoxon test was conducted with a Bonferroni correction, resulting in a significance level set at 0.0125 (0.05/4). There were no significant differences between Profiles 1 and 2 (z = −0.84, p = 1.0), Profiles 1 and 3 (z = −0.74, p = 1.0), Profiles 1 and 4 (z = −2.01, p = 0.265), Profiles 2 and 3 (z = −1.75, p = 0.48), and Profiles 3 and 4 (z = −1.43, p = 0.918). Significance was approached between Profiles 2 and 4; however, it did not meet the adjusted significance level (z = −1.75, p = 0.017). See Figure 11 below.

Figure 11.

Ratings according to online content courses and instructor profile. Instructor 1 is a native speaker from Spain, Instructor 2 is a native speaker from Latin America, Instructor 3 is a Heritage Speaker of Spanish, and Instructor 4 is an L2 Spanish speaker.

3.3. Participants’ Preferences on Modality

This survey also examined students’ overall interest in taking a course either F2F or online. Students read the following questions and marked their responses on a sliding scale:

- “I am very interested in taking F2F Spanish language classes (L2 or Heritage) to improve my Spanish.”

- “I am very interested in taking Online Spanish language classes (L2 or Heritage) to improve my Spanish.”

- “I am very interested in taking F2F content courses in Spanish.”

- “I am very interested in taking Online content courses in Spanish.”

To corroborate the findings above and examine differences, if any, between student ratings for both F2F and online courses, scores for both language and content courses were averaged. An independent t-test was conducted to compare students’ preference between F2F and online courses in language and content. According to the analysis, there was a significant difference in students’ preference toward F2F courses (M = 4.64, SD = 0.65) and online courses (M = 2.66, SD = 1.31); t = 11.905, df = 109.79, p < 0.001). These results suggest that students prefer F2F courses over online courses. Table 4 presents the summary statistics for the survey responses according to modality of delivery below.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for the participants’ preferences on modality of delivery.

3.4. Summary of Main Findings

Before turning to the discussion, we offer a brief summary of this study’s findings in Table 5, which includes a general description of the three main research questions and the findings that emerged.

Table 5.

Summary of main findings.

4. Discussion

In this section, we revisit the results presented in the previous section and provide an integrated discussion of the main findings.

4.1. Discussion of Research Question 1

Regarding the first set of research questions, we aimed to answer: How do HS students perceive the four different instructor profiles along the dimensions of Content Knowledge, Grammatical Knowledge, Shared Cultural Background, Respect for the Instructor’s Linguistic Background, and Ability to Provide Sensitive Feedback? What differences exist, if any, between the student ratings across four instructor type groups?

It is important to note that all profiles received considerably high ratings. However, differences in scores for the five dimensions reveal a noticeable trend regarding the students’ perceptions toward the four instructor profiles. In the case of Content Knowledge and Grammatical Knowledge, participants rated the instructor native to Spain, Profile 1, higher on average than the other profiles, Profiles 2, 3, and 4. This trend was reversed for questions on cultural relatability (i.e., Shared Cultural Knowledge, Respect for the Instructor’s Linguistic Background, and Sensitive Feedback). In other words, participants, on average, assigned higher ratings to Profile 2, instructors native to Latin America and Profile 3, the Heritage instructor. Profile 3, on the other hand, did not achieve the highest rating in any of them. Additionally, students assigned, on average, the lowest scores to the L2 instructor, Profile 4, in all but one dimension. For Shared Cultural Knowledge, Profile 4, the L2 Instructor, received higher scores, on average, than Profile 1, instructors from Spain.

The lower scores assigned to Heritage and L2 Instructors, Profiles 3 and 4, respectively, may be indicative of commonly held beliefs among HS students about the two profiles. That is, there is: (1) the belief that HS instructors’ Spanish, despite being speakers of Spanish, holds a lower social value than that of speakers from Spanish-speaking countries; and (2) a disposition that L2 instructors are less relatable regarding students’ cultural and linguistic needs.

Accordingly, HS may be exhibiting popular discourses on the prestige and value of their heritage language and culture. That is, they may view their Spanish to be substandard on different dimensions, as conveyed by Potowski (2002). These language ideologies reflect the perpetuation of negative stereotypes and feelings of inferiority previously reported in the literature. Nonetheless, research, such as Beaudrie (2020), contends that HS students strongly desire to reconnect with their cultural heritage and to stand in solidarity with other members of the HL community. This finding is reflected in these findings, particularly along the lines of instructors’ cultural relatability and shared background.

With regard to L2 speakers, Profile 4, HS students assigned lower scores, on average, in response to these instructors’ linguistic and cultural relatability. Although this finding is not necessarily surprising, this trend should be accounted for in pedagogical and curricular decision making. Additionally, the low ratings for cultural aspects suggest that HS may underestimate the extent of cultural relatability that such speakers might actually possess, taking into consideration the extensive integration typically required for such speakers to acquire such a high level of proficiency. Anecdotally, many L2 instructors are often parents and/or spouses to HS, making them intimately familiar with and empathetic to the challenges experienced by HS. Equally plausible, though, is that this negative bias toward the L2 speaker is in response to actual previous experiences familiar to many HS perpetrated by this profile, such as past linguistic suppression and embarrassment in the educational setting or discriminatory practices at a societal level. Worth noting, however, is that in terms of cultural similarity, participants assigned higher scores, on average, to the L2 Instructor, Profile 4. These ratings were higher than instructors from Spain, Profile 1, suggesting that students may relate more to non-Hispanic US nationals due to their shared sociopolitical environment than they do with Peninsular Spanish speakers.

Instructors must seek to instill a collective awareness and widespread level of commitment to HS language teaching, moving beyond monoglossic framings and the stigmatization of language repertoires. What is needed is a critical rethinking of bilingualism and an understanding of language that acknowledges the flexibility and skill in HS’ everyday language practices. Such an approach allows instructors to advocate for HS by avoiding deficit approaches. This practice may, in turn, develop students’ metalinguistic awareness that problematizes the all-too-common goal of which teachers strive for mastery of the “target language”.

Additionally, we would like to emphasize that these findings should not be taken as evidence or argument to support that certain profiles are better suited to teach Spanish as a Heritage Language than others. Rather, we encourage programs and departments to acknowledge these perceptions and to offer professional development opportunities to their instructors, regardless of their backgrounds, in order to equip them with the necessary tools to address the students’ prejudices in social, cultural, and linguistic realms. These trainings should not only discuss pedagogical practices and general classroom management techniques but also touch on subjects related to social justice, linguistic discrimination, and cultural bias, among others.

4.2. Discussion of Research Question 2

The second research question considered HS students’ preferences regarding their instructors’ sociolinguistic background in different course contexts. When prompted to identify their preferences across contexts and modalities, participants consistently indicated that they preferred to have an instructor native to Latin America at the front of the classroom, followed by an instructor native to Spain, then a Heritage instructor, and lastly an L2 instructor. The most common pattern showed an overt preference for instructors native to Latin America or Spain over the others. Moreover, the instructor native to Latin America was always preferred over the Heritage or L2 instructor, except in the case of online courses. That is, in the case of online courses, the significance was limited to only a preference for the instructor native to Latin America over the L2 Instructor. This finding is in line with our previous discussion: While the participants were HS themselves, they chose the Spanish and the Latin American instructors as preferred linguistic models in the classroom and, while both of these two profiles are prestigious speakers of the language, the Latin American one is perceived as being culturally closer to the student. Thus, the combination of these two factors results in the Latin American instructor being their preferred profile for all class types.

This trend suggests that, despite students assigning higher ratings, on average, to Profile 1 in Content Knowledge and Grammatical Knowledge, participants placed a high value on instructors’ cultural proximity and relatability. More importantly, students assigned lower scores, on average, to the Heritage instructor, Profile 3, for all class types, despite identifying themselves as one. Moreover, the L2 instructor, Profile 4, was the lowest rated across class types, which may be interpreted as further confirmation for the beliefs aforementioned. These findings are most perplexing when compared with the findings of Román et al. (2019) that non-US-born Spanish instructors (i.e., Profiles 1 and 2) are more likely to embrace and enact purist language ideologies. That is, Román et al. (2019) demonstrates that these instructors often correct their students more and are less likely to tolerate code-switching. For HS students, this disposition may generate a classroom dynamic that is less supportive and less understanding of their unique abilities and needs as bilinguals. This current study, however, demonstrates how, on average, HS prefer these classrooms, seemingly due to the overt prestige of the instructor’s language background.

These language attitudes may determine students’ preferences, such that these dispositions do not always align with—and sometimes run counter to—their actual experiences in the classroom. This dynamic reiterates the need for HL programs to tackle these biases before they become realized, especially as these students rarely have a choice for the background of their Spanish instructor. Turning again toward the aspect of cultural relatability, it is interesting that the cultural proximity of Profile 2 is influential, making it the most preferred instructor profile. This finding contradicts the authors’ a priori hypothesis, such that Profile 3 instructors relate to HS students in terms of their cultural and ethnolinguistic backgrounds, but received lower scores than Profile 2. Consequently, it is important to recognize HS instructors for the unique sensitivity that they can bring to their classes and to harness it as a valuable tool in the classroom. It should also be noted that all instructors received lower ratings in online class types, which might be taken as their disregard or dislike of online classes in general. This claim was further sustained by the results for the third research question, presented below.

4.3. Discussion of Research Question 3

The effect of modality revealed that students displayed an overt preference for F2F courses over those offered online. Taking into consideration that this study was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is very possible that not all students had participated in or had been exposed to online pedagogy. The survey did not specifically probe students’ previous experience with online education and, thus, their preferences may have been guided largely by negative stereotypes of online courses. Conversely, the development of online language pedagogy was still quite nascent at the beginning of the pandemic and certainly, improved methods have emerged from the widespread focus and experimental models that have since been implemented. The interaction of previous experience with online education and student preferences, especially post pandemic, will no doubt enrichen this direction of inquiry and complement the current findings.

Nonetheless, this modality effect mirrors and further supports the results obtained by Torres (2020), which found that HL learners expressed more difficulty completing communicative tasks in an online environment. Therefore, one possibility for the preference for F2F courses could be due to their comfort with using the HL in oral communication in a F2F context. Additionally, as Henshaw (2016b) pointed out, online courses may hinder a sense of classroom community, and this sense of isolation, which although broadly reported by online students of all backgrounds, disproportionately affects HS who specifically enroll in HL courses to find community and to connect with others of similar experiences. Therefore, the lack of student preference for online courses as well as an indifference to the instructor type within this modality suggests a student-held belief that online courses are largely impersonal and anonymous and more technology-driven than relationship-based. Therefore, it would be irrelevant to them who is instructing such a course.

However, with the newfound focus on online pedagogy coupled with the rapid development of technological tools, the context is perfect for a transformation of the online environment into an intimate and personal setting. In line with Marull and Kumar’s (2020) relationship-based framework for online language instruction, these emerging technologies and approaches may exponentially increase the ways in which students can interact amongst themselves and with others to create rich and supportive communities. These opportunities could be particularly transformative to HL pedagogy if properly harnessed by providing a safe space for HS students to connect with geographically distanced peers to critically reflect on questions of identity and to discuss their shared experiences as Latinxs in the United States. In addition, these technologies could provide the bridge for students to engage remotely with service initiatives within Spanish-speaking communities locally, nationally, and internationally and as such, increase the effectiveness of the heritage classroom via community involvement, as discussed above. The disruption of COVID-19 has accelerated a change in attitudes towards online learning. The perception that online learning is the least effective for language instruction has been put into question as more begin to realize that one modality is not by nature alone superior to another, nor can a modality itself guarantee outcomes. Although each context is very different and presents different opportunities and challenges, with proper implementation, online courses can be the vehicle that transforms the way we envision our relationship with time and space in educational contexts. As the quality of online instruction increases and the academic community begins to realize the benefit of its geographical and temporal freedom, instructors and students alike may strategically begin to recognize online courses as a flexible alternative to complement or to implement creative and enriching learning experiences.

4.4. Discussion of Future Directions

With regard to future research, one fruitful direction would be to further examine individual variations and unpack contextual differences in the classroom and university settings. For example, there was greater variation in ratings assigned to Profiles 3 and 4, which suggests additional contributing factors toward student perceptions. As a testament to this variation, preliminary analyses signaled a relationship between student proficiency (i.e., self-rated proficiency on listening, speaking, reading, and writing) and ratings. There also appears to be a relationship between previous experience and student ratings. Regarding the relationship between Spanish language proficiency and student ratings, it appears that students with higher proficiency assigned higher instructor ratings. However, the overall preference for native speakers, especially the Latin American native (i.e., Profile 2), remained. This pattern may suggest that students hold more favorable views as they gain greater linguistic competence. Further research should continue interrogating the relationship between language proficiency and students’ attitudes toward their instructors.

Driven by this finding—that is, that the L2 and HS instructors were consistently rated lower than the instructors native to Latin America or Spain—a preliminary analysis examined differences between students with previous experience compared with those without experience. Table 6 below provides some descriptive statistics for these interactions along the five dimensions studied.

Table 6.

Instructor profile ratings based on previous experience with that instructor profile.