Typological Shift in Bilinguals’ L1: Word Order and Case Marking in Two Varieties of Child Quechua

Abstract

1. Introduction

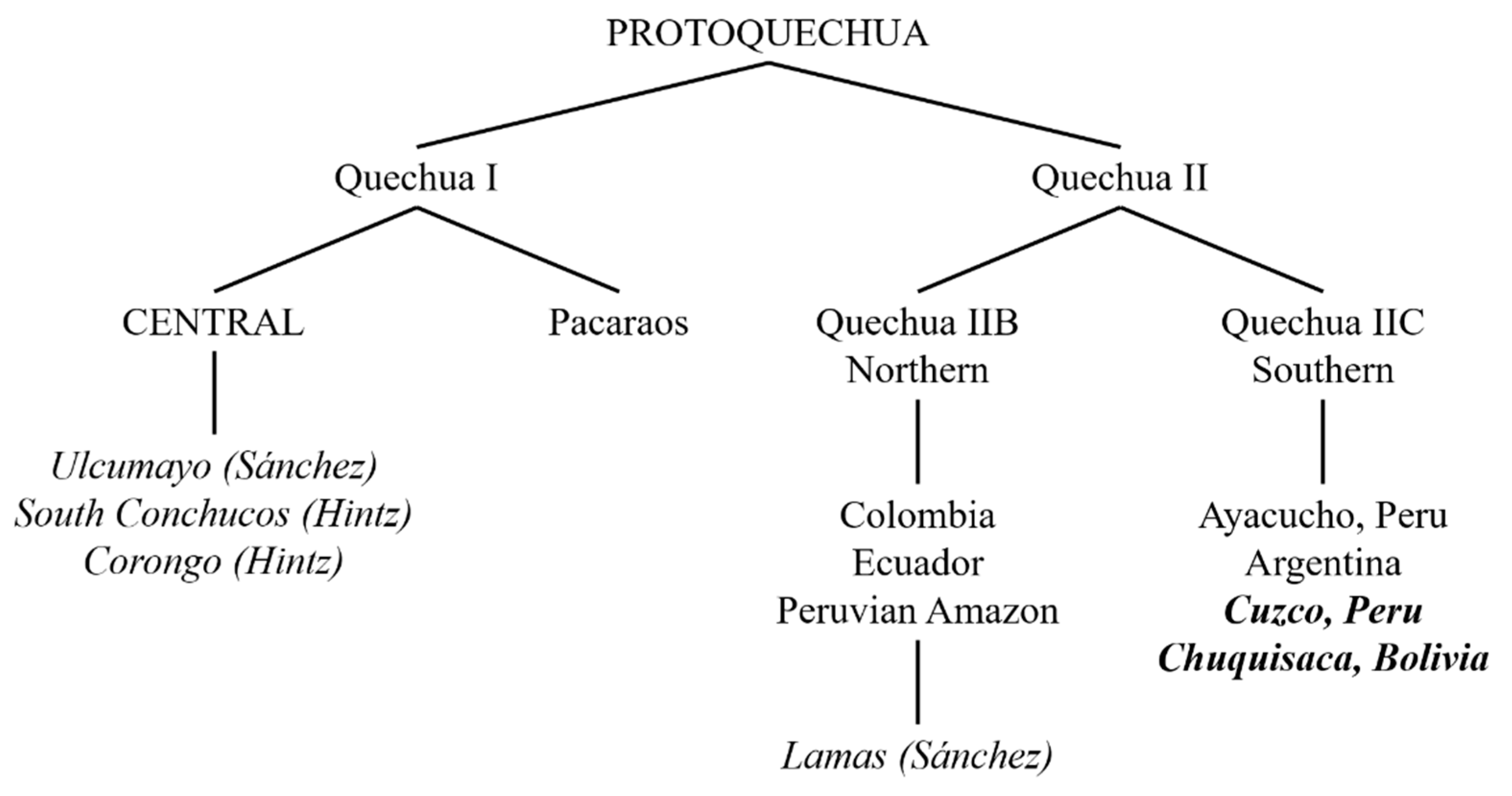

2. Overview of Southern Quechua in Cuzco and Chuquisaca

Chuquisaca, Bolivia lies near the southern extreme of the linguistic area that produced Standard Colonial Quechua (quz/quh). Movement among people there was reinforced through one of the world’s major silver mining circuits of the 16th century. Cuzco Quechua is the prestige variety which has been documented for over 500 years, whereas Bolivian varieties have rarely received attention (Durston 2007; Mannheim 1991). Quechua is now ‘definitely endangered’ in this region as intergenerational transmission is increasingly abandoned in favor of Spanish.

2.1. Factors Determining Quechua Language Variation

3. Overview of Properties of Quechua and Spanish Relevant to This Study

3.1. Morphological Properties

| 1. | Wasi-y-pi | hampi-wa-chka-n-mi |

| house-1pos-loc | cure-1obj-prog-3-direv | |

| “(I can testify that) He/she is treating me in my home.” | ||

| 2. | Me | está | cur-ando | en | mi | casa |

| 1obj | is | cure-prog | in | 1pos | house | |

| “He/she is treating me in my home.” | ||||||

| 3. | Yanapa-chka-Ø-nki |

| help-prog-3obj-2 | |

| “You are helping him/her/someone.” |

| 4. | Chay | wawa-cha-ta | puñu-ya-chi-y! |

| that | child-dim-acc | sleep-int-caus-imp | |

| “Make that child go to sleep!” | |||

| 5. | Haku-chu | llaqta-ta |

| go-intrr | town-obj | |

| “Shall we go to town?” | ||

| 6. | Abankay-ni-n-ta-m | carretera-qa | ri-chka-n | Andawaylas-man-qa |

| Abancay-euf-3pos-obj-direv | road-top | go-prog-3 | Andahuaylas-dat-top | |

| “The road to Andahuaylas passes through Abancay.” | ||||

3.2. Word Order in Main Clauses

| 7. | Luwis | tanta-ta | mikhu-chka-Ø-n |

| Lewis | bread-acc | eat-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “Lewis is eating bread.” | |||

| 8. | Tanta-ta-m | Luwis | mikhu-chka-Ø-n |

| bread-acc-direv | Lewis | eat-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “It is bread that Lewis is eating.” | |||

| 9. | Mikhu-chka-Ø-n-mi | tanta-ta | Luwis |

| eat-prog-3obj-3-direv | bread-acc | Lewis | |

| “Lewis is eating bread.” | |||

3.3. Word Order at the Phrase Level in Quechua

- Adjectives precede nouns

- Possessors precede possessed nouns

- Verbs precede auxiliaries

- Subordinate clauses precede matrix clauses

| 10. | qan-pa | alqu-yki |

| you-gen | dog-2pos | |

| “your dog” | ||

| 11. | waka-q | chaki-n |

| cow-gen | foot-3pos | |

| “the cow’s foot” | ||

| (Cusihuamán Gutiérrez 1976, p. 147) | ||

| 12. | José | agarró | el | sombrero | de | María |

| José | grabbed | the | hat | gen | María | |

| “José grabbed María’s hat.” | ||||||

| 13. | José | le | tocó | el | brazo | a | María |

| José | 3obj | touched | the | arm | to | María | |

| “José touched María’s arm.” | |||||||

3.4. Contrasts in the Specification of Nouns in Quechua and Spanish

| 14. | Waka | q’achu-ta | mikhu-n |

| bovine | forage-acc | eat-3 | |

| “Cows eat forage.” | |||

| 15. | Waka-qa | q’achu-ta | mikhu-chka-n | wata-na-n-pi |

| bovine-top | forage-acc | eat-prog-3 | tie-nom-3pos-loc | |

| “The cow is eating forage at its hitching post.” | ||||

| 16. | Hatun | llama-ta | qhawa-chka-ni |

| big | llama-acc | watch-prog-1 | |

| “I am watching a/the big llama.” | |||

| 17. | Huk | llama-ta | qhawa-chka-ni |

| one/other | llama-acc | watch-prog-1 | |

| “I am watching one/another/the other llama.” | |||

4. Previous Experimental Studies of L1 Development of Quechua Word Order, Morphological Marking, and Interpretation

- Accusative case-marking is robust in Quechua first-language acquisition, except with Spanish loanwords.

- Accusative case-marking is acquired prior to direct object verbal morphology.

- Final subjects are frequent at early stages of acquisition. There is no evidence of a preference for SVO word orders in early Quechua acquisition.

- For one child, subject agreement morphology preceded object agreement morphology.

4.1. The Mechanism of Change in Hintz’s Work on Verbal Periphrasis

| 18. | Native Quechua order | Puñu-q | ri-ni |

| sleep-nom | go-1 | ||

| “I will be asleep.” | Santiago del Estero Quechua | ||

| verbstem-nominalizer | auxiliary-inflection | ||

| 19. | Spanish-influenced order | Ri-ni | puñu-q |

| go-1 | sleep-nom | ||

| auxiliary-inflection | verbstem-nominalizer |

4.2. Sánchez’s Theory of Functional Convergence in Bilingual Quechua-Spanish

The specification of a common set of features shared by the equivalent functional categories in the two languages spoken by a bilingual, takes place when a set of features that is not activated in language A is frequently activated in language B in the bilingual mind.

5. Statement of Our Experimental Hypotheses

- Word order in simple declarative sentences (SOV is expected, with allowances for the fronting of focused elements);

- Word order in possessive phrases (the order possessor-possessed is expected);

- Use of accusative markers (we expect -ta on nouns to distinguish objects from subjects in main clauses; subjects have no overt case marking. -ta may also mark goals and paths; -ta-marked objects must be further distinguished from adverbs); and

- Use of determiners (no determiners are expected to exist; instead, adjectives, demonstrative pronouns, and numbers precede the nouns they modify).

6. Methodology

6.1. Population and Participant Selection

6.2. An Initial Distinction between the Two Varieties in the Corpus

| 20. | Cuadernó-ta | hap’i-chka-n |

| notebook-acc | grab-prog-3 | |

| “He is grabbing the notebook.” | ||

| (Chuquisaca, female, age 8) | ||

| 21. | Cuadernó-Ø | hap’i-chka-n |

| notebook-acc | grab-prog-3 | |

| “He is grabbing the notebook.” | ||

| (Chuquisaca, female, ages 9 and 12) | ||

7. Analysis and Findings

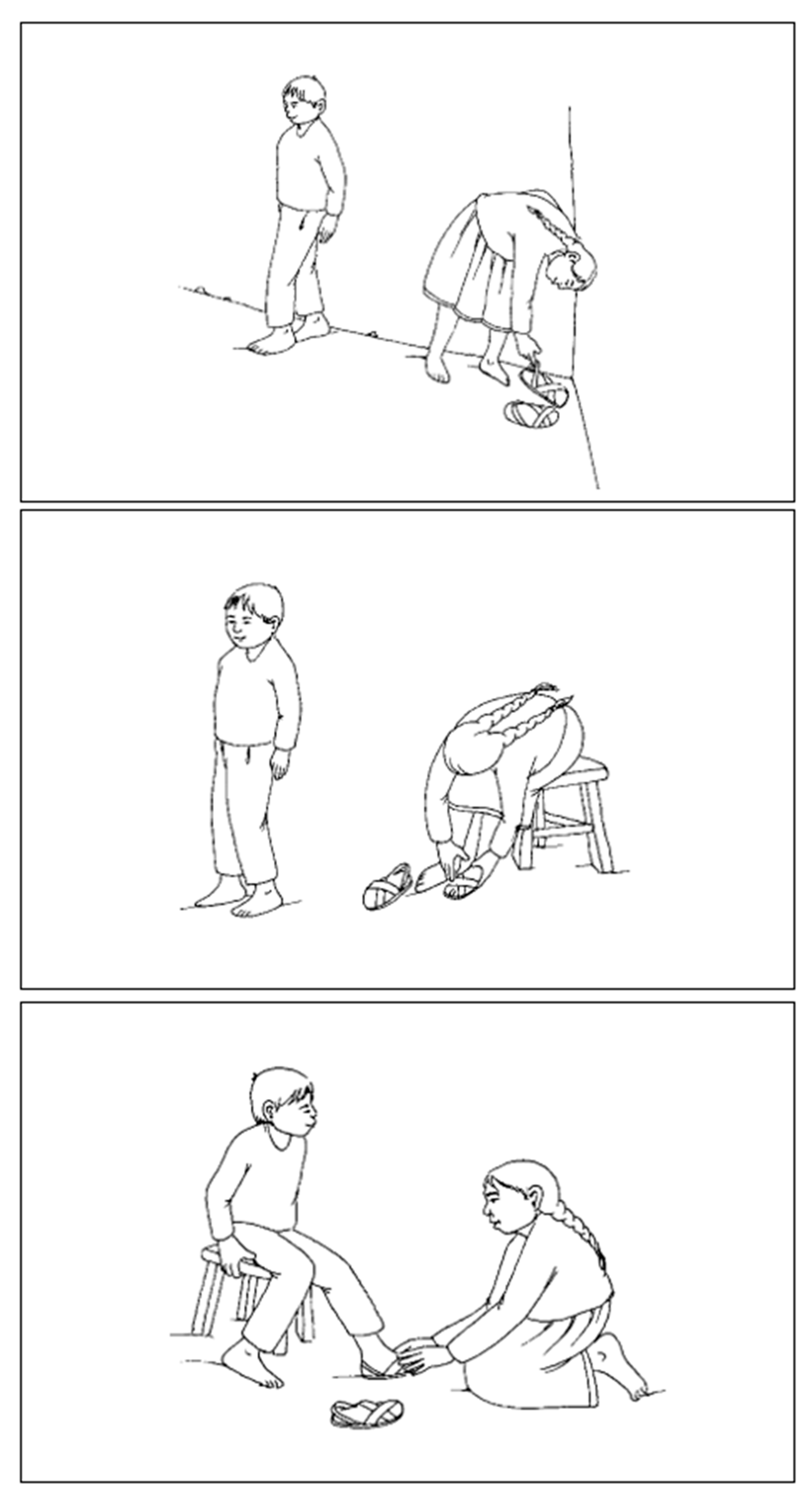

7.1. Procedures

7.2. Analysis of VO vs. OV Word Order

| 22. | Chura-chka-Ø-n | uhut’a-ta |

| put-prog-3obj-3 | sandal-acc | |

| “She’s putting the sandal on him.” | ||

| (VO; Chuquisaca, female, age 9) | ||

| 23. | Ana | hap’i-chka-Ø-n | José-ta |

| Ana | grab-prog-3obj-3 | José-acc | |

| “Ana is grabbing José.” | |||

| (SVO; Cuzco, male, age 10) | |||

| 24. | Maqchi-ku-chka-Ø-n | chika-cha | maki-n-ta |

| wash-refl-prog-3obj-3 | girl-dim | mano-3pos-acc | |

| “The little girl is washing her hands.” | |||

| (VSO; Cuzco, male, age 6) | |||

| 25. | Hach’i-chka-Ø-n | mistura-ta | José |

| winnow-prog-3obj-3 | confetti-acc | José | |

| “José is winnowing the confetti.” | |||

| (VOS; Cuzco, male, age 10) | |||

| 26. | Uhut’a-ta | chura-chka-Ø-n |

| sandal-acc | put-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “She’s putting the sandal on him.” | ||

| (OV; Chuquisaca, female, age 9) | ||

| 27. | José | mistura-ta | hach’i-chka-Ø-n |

| José | confetti-acc | winnow-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “José is winnowing the confetti.” | |||

| (SOV; Cuzco, male, age 6) | |||

| 28. | Uma-n-ta | José | hap’i-ku-Ø-n |

| head-3pos-acc | José | agarrar-refl-3obj-3 | |

| “José is grabbing his head.” | |||

| (OSV; Cuzco, male, age 12) | |||

| 29. | Bisturas-ta | hach’i-chka-Ø-n | anchay |

| confetti-acc | winnow-prog-3obj-3 | that.one | |

| “That one is winnowing the confetti.” | |||

| (OVS; Cuzco, female, age 11) | |||

| 30. | José-ta | maqchi-chka-Ø-n | uya-n-ta |

| José-acc | wash-prog-3obj-3 | face-3pos-acc | |

| “She is washing José’s face.” | |||

| (VO; Cuzco, male, age 5) | |||

| 31. | Maki-n-ta | hap’i-chka-Ø-n | José-q-ta |

| hand-3pos-acc | grab-prog-3obj-3 | José-gen-acc | |

| “She is grabbing José’s hand.” | |||

| (OV; Chuquisaca, female, age 13) | |||

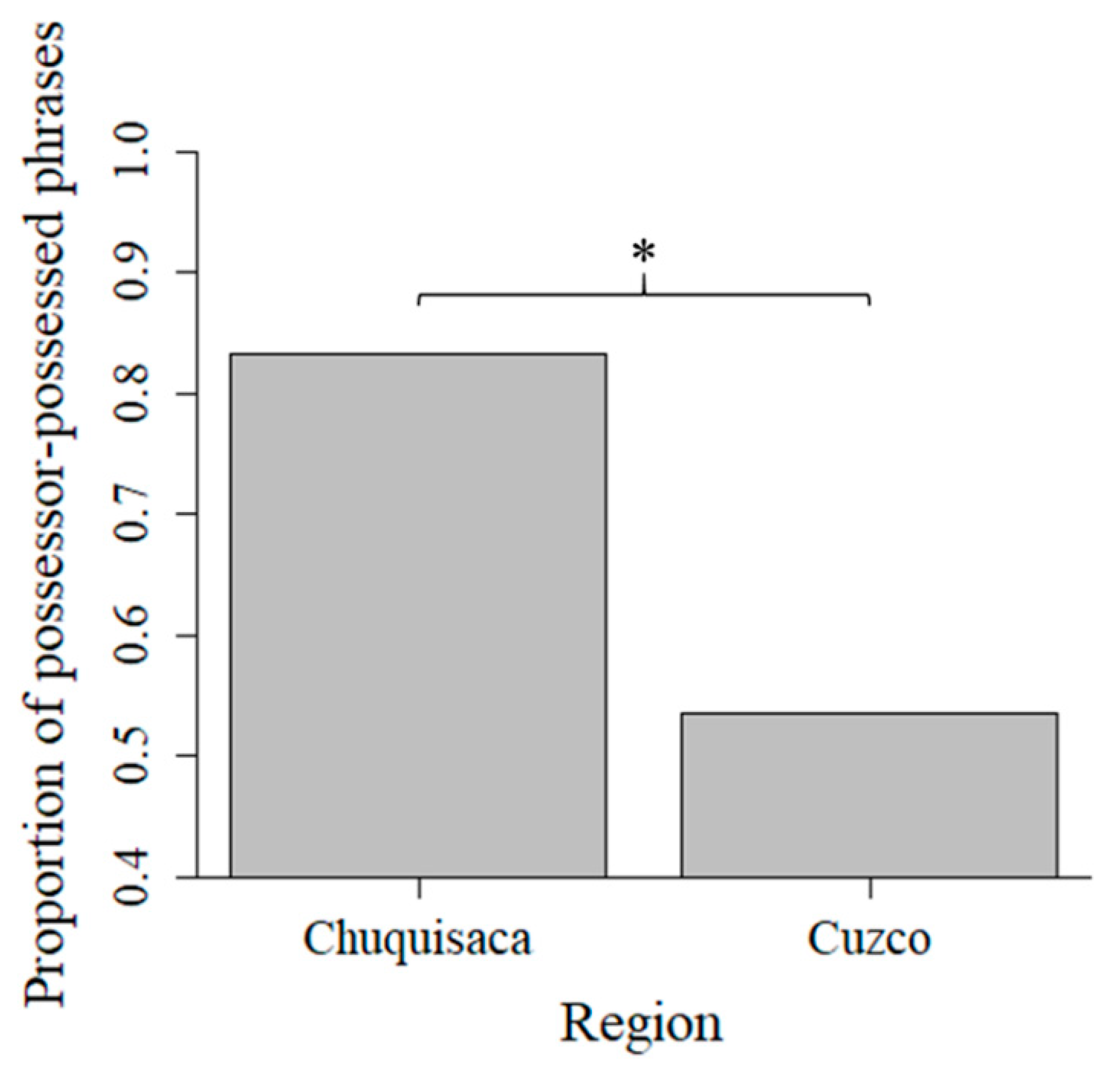

7.3. Analysis of Possessor-Possessed vs. Possessed-Possessor Word Order

| 32. | Ana-q | chaki-n-ta | maylla-chka-Ø-n |

| Ana-gen | foot-3pos-acc | wash-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “He’s washing Ana’s foot.” | |||

| (possessor-possessed; Chuquisaca, female, age 11) | |||

| 33. | José-pa | maki-n-ta | hap’i-chka-Ø-n |

| José-gen | hand-3pos-acc | grab-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “She’s grabbing José’s hand.” | |||

| (possessor-possessed; Cuzco, female, age 9) | |||

| 34. | Maki-n-ta | huk-pa-ta | maylla-chka-Ø-n |

| hand-3pos-acc | other-gen-acc | wash-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “She’s washing someone else’s hand.” | |||

| (possessed-possessor; Chuquisaca, female, age 10) | |||

| 35. | Chaki-n-ta | Ana-q-ta | maqchi-chka-Ø-n |

| foot-3pos-acc | Ana-gen-acc | wash-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “He’s washing Ana’s foot.” | |||

| (possessed-possessor; Cuzco, male, age 12) | |||

7.4. The Emergence of Determiners

| 36. | Chaymanta | chay | wambriyo | mira-rka-n | chay | sapu-ta |

| then | that | boy | look-pst-3 | that | toad-acc | |

| “Then, that boy looked at that toad.” | ||||||

| 37. | Suk | motelo | mira-yka-n | suk | sapitu-ta |

| a | turtle | look-dur-3 | a | toad-acc | |

| “A turtle is looking at a toad.” | |||||

| 38. | Kay-pi | huk | ladu-ta | hach’i-yu-chka-Ø-n |

| here-loc | other | side-acc | toss-int-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “Here, he is tossing it somewhere else.” | ||||

| (Cuzco, male, age 6) | ||||

| 39. | Pay | huk-ni-n-ta | hap’i-chka-Ø-n |

| 3 | one-euf-3pos-acc | grab-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “She is grabbing one of them.” | |||

| (Cuzco, male, age 13) | |||

| 40. | Huk | qhari | warmi-ta | hap’i-chka-Ø-n |

| a | man | woman-acc | grab-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “A man is grabbing the woman.” | ||||

| (Chuquisaca, female, age 10) | ||||

| 41. | Huk | qhari-ta | tupa-chka-Ø-n |

| a | man-acc | touch-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “She is touching a man.” | |||

| (Chuquisaca, male, age 8; female, age 10) | |||

| 42. | Huk | warmi | hap’i-chka-Ø-n |

| a | woman | grab-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “He is grabbing a woman.” | |||

| (Chuquisaca, male, age 11) | |||

| 43. | Huk | warmi-man | punchu-chi-chka-Ø-n |

| a | woman-dat | poncho-caus-prog-3obj-3 | |

| “He is putting the poncho on a woman.” | |||

| (Chuquisaca, female, age 10) | |||

8. Discussion of Results

9. Conclusions and Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 44. | Ana | ujut’a-ta | chura-Ø-n |

| Ana | sandal-acc | put-3obj-3 | |

| “Ana puts the sandal on him.” “Ana puts the sandal on herself.” “Ana puts the sandal there.” “Ana puts the sandal somewhere.” | |||

| 45. | José | sumbuku-ta | chura-ku-Ø-n |

| José | hat-acc | put-refl-3obj-3 | |

| “José puts the hat on himself.” | |||

| 46. | José | chumpa-ta | puñuna-pata-man | chura-Ø-n |

| José | sweater-acc | bed-top-dat | put-3obj-3 | |

| “José puts the sweater on the bed.” | ||||

| 47. | Ana | awana-ta | hap’i-Ø-n |

| Ana | loom-acc | grab-3obj-3 | |

| “Ana grabs the loom.” | |||

| 48. | José | uma-n-ta | hap’i-Ø-n |

| José | head-3pos-acc | grab-3obj-3 | |

| “José grabs her head.” “José grabs someone’s head.” | |||

| 49. | José | kukuchu-n-ta | hap’i-ku-Ø-n |

| José | elbow-3pos-acc | grab-refl-3obj-3 | |

| “José grabs his elbow.” | |||

References

- Adelaar, Willem. 2020. Linguistic connections between the Altiplano region and the Amazonian lowlands. In Rethinking the Andes-Amazonia Divide: A Cross-Disciplinary Exploration. Edited by Adrian J. Pearce, David G. Beresford-Jones and Paul Heggarty. London: UCL Press, pp. 239–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín de Alderetes, Lelia Inés. 2016. La Quichua: Gramática, Ejercicios y Selección de Textos. Buenos Aires: Dunken, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark C. 1996. The Polysynthesis Parameter. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Mark C. 2001. The Atoms of Language: The Mind’s Hidden Rules of Grammar. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Barragán Romano, Rossana. 1994. ¿Indios de arco y Flecha?: Entre la Historia y la Arqueología de las Poblaciones del Norte de Chuquisaca (Siglos XV–XVI). Sucre: Antropólogos del Surandino. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, Garland D., Bernardo Vallejo C., and Rudolph C. Troike. 1971. An Introduction to Spoken Bolivian Quechua. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, J. Kathryn. 1986. Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology 18: 355–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, José, Liliana Paredes, and Liliana Sánchez. 1995. The genitive clitic and the genitive construction in Andean Spanish. Probus 7: 133–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. 1987. Lingüística Quechua. Cuzco: Centro Bartolomé de las Casas. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. 2008. Quechumara: Estructuras Paralelas del quechua y del Aimara. La Paz: Plural Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. 2020. La presencia puquina en el aimara y en el quechua: Aspectos léxicos y gramaticales. Indiana 37: 129–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero Céspedes, Cintya Elizabeth, and Verónica Cruz Agudo. 2013. Descripción de la estructura morfológica Nominal y Verbal del Quechua de Anzaldo (Valle Alto–Cochabamba). Master’s thesis, Universidad Mayor de San Simón, Cochabamba, Bolivia. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney, Ellen H. 1999. Child acquisition of the Quechua affirmative suffix. In Proceedings from the Second Workshop on American Indigenous Languages. Santa Barbara: University of California, Santa Barbara, pp. 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney, Ellen H. 2002. Child acquisition of Quechua causatives and change-of-state verbs. First Language 22: 29–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, Ellen H. 2006. Adult and child production of Quechua relative clauses. First Language 26: 317–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, Ellen H. 2008. Child Production of Quechua Evidential Morphemes in Conversations and Story Retellings; University of Texas at El Paso Unpublished manuscript. Available online: https://works.bepress.com/ellenhcourtney/11/ (accessed on 1 June 2013).

- Courtney, Ellen H. 2010. Learning the meaning of verbs: Insights from Quechua. First Language 30: 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, Ellen H. 2015. Child acquisition of Quechua evidentiality and deictic meaning. In Quechua Expressions of Stance and Deixis. Edited by Marilyn Manley and Antje Muntendam. Boston: Brill, pp. 101–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, Ellen H, and Muriel Saville-Troike. 2002. Learning to construct verbs in Navajo and Quechua. Journal of Child Language 29: 623–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusihuamán Gutiérrez, Antonio. 1976. Gramatica Quechua: Cuzco-Collao. Lima: Ministerio de Educación. [Google Scholar]

- Dankel, Philipp, and Mario Soto Rodríguez. 2012. Convergencias en el área andina: La testimonialidad y la marcación de la evidencialidad en el español andino y en el quechua. In El Español de los Andes: Estratégias Cognitivas en Interacciones Situada. Edited by Philipp Dankel, Victor Fernández Mallat, Juan Carlos Godenzzi and Stefan Pfänder. Berlin: Lincom, pp. 89–120. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, Werner, Charlotte Koster, and Jan Koster. 1986. What can we learn from children’s errors in understanding anaphora? Linguistics 24: 203–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durston, Alan. 2007. Pastoral Quechua: The History of Christian Translation in Colonial PERU, 1550–1650. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2019. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 22nd ed. Dallas: SIL International. Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Fedzechkina, Maryia, Elissa L. Newport, and T. Florian Jaeger. 2016. Balancing effort and information transmission during language acquisition: Evidence from word order and case marking. Cognitive Science 41: 416–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. In Universals of Human Language. Edited by Joseph H Greenberg. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 73–113. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, Joaquín, and Federico Sánchez de Lozada. 1978. Gramática Quechua: Estructura del Quechua Boliviano Contemporáneo. Cochabamba: CEFCO/Editorial Universo. [Google Scholar]

- Hintz, Daniel J. 2009. Reordenamiento sintáctico en construcciones verbales analíticas del Quechua por el contacto con el castellano. Lingüística 22: 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hintz, Daniel J. 2011. Crossing Aspectual Frontiers: Emergence, Evolution, and Interwoven Semantic Domains in South Conchucos Quechua Discourse. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hintz, Daniel J. 2016. Auxiliation and typological shift: The interaction of language contact and internally-motivated change in Quechua. In Language Contact and Change in the Americas: Studies in Honor of Marianne Mithun. Edited by Andrea L Berez-Kroeker, Diane M Hintz and Carmen Jany. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, Susan E. 2002. Second Language Acquisition of Spanish Morpho-Syntax by Quechua-Speaking Children. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kalt, Susan E. 2009a. Bilingual Children’s Object Agreement and Case Marking in Cusco Quechua. University of British Columbia Working Papers in Linguistics. Vancouver: University of British Columbia, p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Kalt, Susan E. 2009b. The speech of children from Cusco and Chuquisaca. The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America. Access Is Currently Restricted Due to Age of interviewees. Available online: https://www.ailla.utexas.org/islandora/object/ailla%3A124493 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Kalt, Susan E. 2012a. Cambios morfosintácticos en castellano impulsados por el quechua hablante. In El Español de los Andes: Estratégias Cognitivas en Interacciones Situada. Edited by Philipp Dankel, Victor Fernández Mallat, Juan Carlos Godenzzi and Stefan Pfänder. Berlin: Lincom, pp. 165–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kalt, Susan E. 2012b. Diseño de investigaciones sistemáticas para idiomas poco documentados: El caso del quechua y el castellano andino. In Actas del Segundo Simposio Sobre Enseñanza y Aprendizaje de Lenguas Indígenas de América Latina (STLILLA). Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame. [Google Scholar]

- Kalt, Susan E. 2015. Pointing in space and time: Deixis and directional movement in schoolchildren’s Quechua. In Quechua Expressions of Stance and Deixis. Edited by Marilyn Manley and Antje Muntendam. Boston: Brill, pp. 25–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, Susan E. 2016. Duck and frog stories in Chuquisaca Quechua. The Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America. Available online: https://www.ailla.utexas.org/islandora/object/ailla%3A258876 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Laime Ajacopa, Teófilo. 2014. Quichwapi Rimarisqa Rimay Jap’inamanta: Pragmática de los Enunciados en el Quechua. La Paz: Plural Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Lastra, Yolanda. 1968. Cochabamba Quechua Syntax. The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Claire, and Pieter Muysken. 1988. Mixed Categories: Nominalizations in Quechua. Dordrecht: Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Loebell, Helga, and Kathryn Bock. 2003. Structural priming across languages. Linguistics 41: 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luján, Marta, Liliana Minaya, and David Sankoff. 1984. The Universal Consistency Hypothesis and the prediction of word order acquisition stages in the speech of bilingual children. Language 60: 343–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, Bruce. 1991. The Language of the Inka Since the European Invasion. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mannheim, Bruce. 2018. Three axes of variability in Quechua: Regional diversification, contact with other indigenous languages, and social enregisterment. In The Andean World. Edited by Linda J Seligmann and Kathleen S Fine-Dare. New York: Routledge, pp. 507–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, Bruce, Susan A Gelman, Carmen Escalante, Margarita Huayhua, and Rosalía Puma. 2010. A developmental analysis of generic nouns in Southern Peruvian Quechua. Language Learning and Development 7: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, Hans. 1951. The syntactical change from inflectional to word order system and some effects of this change on the relation verb-object in English. Anglia 70: 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, Pascual José. 1992. Incorporation and Case Theory in Spanish: A Crosslinguistic Perspective. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Washington, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Muntendam, Antje. 2015. Discourse deixis in Southern Quechua: A case study on topic and focus. In Quechua Expressions of Stance and Deixis. Edited by Marilyn Manley and Antje Muntendam. Boston: Brill, pp. 208–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, Johanna. 1986. Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar. Language 62: 56–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, Johanna. 1992. Linguistic Diversity in Space and Time. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Gary J. 1963. La clasificación genética de los dialectos quechuas. Revista del Museo Nacional XXXII: 241–52. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta Zurita, Elvira. 2006. Descripción Morfológica de la Palabra Quechua: un Estudio Basado en el Quechua de Yambata, Norte de Potosí. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés, La Paz, Bolivia. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza Martínez, Pedro. 2015. Qhichwa Suyup Simi Pirwan: Diccionario de la Nación Quechua. Sucre: Consejo Educativo de la Nación Quechua. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 3.6.1. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2003. Quechua-Spanish Bilingualism: Interference and Convergence in Functional Categories. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2004. Functional convergence in the tense, evidentiality and aspectual systems of Quechua Spanish bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 147–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2010. The Morphology and Syntax of Topic and Focus: Minimalist Inquiries in the Quechua Periphery. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sichra, Inge. 2009. Bolivia andina. In Atlas Sociolingüístico de Pueblos Indígenas en América Latina, 1st ed. Cochabamba: Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF), Fundación para la educación en contextos de multilingüismo y pluriculturalidad (FUNPROEIB Andes) and Agencia Española para la Cooperación Internacional al Desarrollo (AECID), vol. 2, pp. 559–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Louisa R., Manuel Segovia Bayo, and Felicia Segovia Polo. 1971. Sucre Quechua: A Pedagogical Grammar. Madison: University of Wisconsin. [Google Scholar]

- Tily, Harry. 2010. The Role of Processing Complexity in Word Order Variation and Change. Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Torero, Alfredo. 1964. Los dialectos quechuas. Anales Científicos de la Universidad Agraria 2: 446–78. [Google Scholar]

- Torrego, Esther. 1998. The Dependencies of Objects. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Urton, Gary. 1997. The Social Life of Numbers: A Quechua Ontology of Numbers and Philosophy of Arithmetic. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- van de Kerke, Simon. 1996. Agreement in Quechua: Evidence against Distributed Morphology. In Linguistics in the Netherlands 1996. Edited by Crit Cremers and Marcel den Dikken. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 121–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Melgarejo, Gaby Gabriela. 2019. “Ma ni pi Qhichwa Purituta ma Parlanchu”: El Quechua en un Contexto de Migración Familiar en dos Comunidades Hablantes de la Región de Tarabuco, Chuquisaca, Bolivia. Master’s thesis, Universidad Mayor de San Simón, Chuquisaca, Bolivia. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Henceforth, we refer to the entire group as “schoolchildren” for the sake of brevity. |

| 2 | In fact, Mannheim refers to “regional diversification” and “enregisterment,” which for our purposes are simplified to “regional distancing” and “social register.” |

| 3 | The following glossing conventions are used in this paper: 1 “first-person subject”; 1obj “first-person object”; 1pos “first-person possessive”; 2 “second-person subject”; 2pos “second-person possessive”; 3 “third-person subject”; 3obj “third-person object”; 3pos “third-person possessive”; acc “accusative”; caus “causative”; dat “dative”; dim “diminutive”; direv “direct evidential”; dur “durative”; euf “euphonic”; gen “genitive”; imp “imperative”; instr “instrumental”; int “intensifier”; intrr “interrogative”; loc “locative”; nom “nominalizer”; obj “object”; pst “past tense”; prog “progressive”; refl “reflexive”; top “topic.” Parentheses are used to indicate optionality. |

| 4 | Sánchez lists -ta as a potential marker of definiteness, but we note that the noun marked with -ta in example 14 receives generic interpretation. |

| 5 | Various analyses of these double -ta sentences are possible; see for example Lefebvre and Muysken (1988, pp. 148–49) and Masullo (1992). We repeated the analysis reported below with the 18 double-ta datapoints omitted and obtained the same significant effects, patterning in the same directions—that is, significant effects of Region (z = −1.97, p < 0.05), Accusative-Inclusion (z = 5.94, p < 0.001), and Sex (z = 2.11, p < 0.05), but not Age (z = −0.88, n.s.). |

| 6 | Recall that omission of the accusative marker is a feature of the Bolivian variety alone in this corpus (N-Chuquisaca = 338 vs. N-Cuzco = 3 utterances). As such, we do not include the interaction of Region by Accusative-Inclusion. |

| 7 | Including random slopes for Accusative-Inclusion by-Child (χ2(2) = 1.18, n.s.; cf. Region, Sex, and Age are all between-Child variables), Sex by-Picture (χ2(2) = 3.01, n.s.), or Age by-Picture (χ2(2) = 3.96, n.s.) instead of random slopes for Region by-Picture failed to improve model fit relative to the random intercepts model. Including random slopes for Accusative-Inclusion by-Picture instead of random slopes for Region by-Picture did improve model fit relative to the random intercepts model (χ2(2) = 12.10, p < 0.005), but not relative to the model that included random slopes for Region by-Picture (AIC-Region by-Picture model = 1386.5, AIC-Accusative-Inclusion by-Picture model = 1386.2; Δ = 0.3, n.s.): Since we are ultimately interested in the effects of Region, we included random slopes for Region by-Picture in order to control for within-Picture variation in the effects of Region before adding random slopes for other dependent variables. However, the same effects as in the analysis reported below remained significant and patterned in the same direction in the model that included random slopes for Accusative-Inclusion by-Picture instead (i.e., the effects of Region (z = −2.67, p < 0.01), Accusative-Inclusion (z = 3.18, p < 0.005), and Sex (z = 2.03, p < 0.05) were significant, but the effect of Age was not (z = −1.03, n.s.)). Including random slopes for Accusative-Inclusion by-Child (χ2(2) = 1.07, n.s.) or Age by-Picture (χ2(3) = 6.44, n.s.) in addition to random slopes for Region by-Picture failed to improve model fit relative to the model that included only random slopes for Region by-Picture. Models that included random slopes for Accusative-Inclusion or Sex by-Picture in addition to random slopes for Region by-Picture failed to converge. Hence, we do not consider models with more complex random effects structures. R code: glmer (WordOrder ~ Region + Accusative-Inclusion + Sex + Age + (1|Child) + (1 + Region|Picture), family = binomial, control = glmer Control (optimizer = “bobyqa”), …). |

| 8 | Including random slopes for Region by-Picture failed to improve model fit relative to the random intercepts model (χ2(2) = 4.67, n.s.), whereas models that included random slopes for Sex by-Picture or for Age by-Picture failed to converge. Hence, we report the results of the random intercepts model. R code: glmer (Accusative-Inclusion ~ Region + Sex + Age + (1|Child) + (1|Picture), family = binomial, control = glmer Control (optimizer = “bobyqa”), …). |

| 9 | Models that included random slopes for Region, Sex, or Age by-Picture failed to converge, likely reflecting that we overfitted the model by adding random slopes (recall that we are analyzing 79 total datapoints here). R code: glmer (WordOrder ~ Region + Sex + Age + (1|Child) + (1|Picture), family = binomial, control = glmer Control (optimizer = "bobyqa"), …). |

| 10 | An anonymous reviewer suggests that greater Aymara influence in the South, even centuries ago, could also contribute to more frequent dropping of accusative -ta since Aymara marks the accusative by suppressing the final vowel of the marked N(P) (i.e., via subtractive morphology). |

| Morphological Type | Isolating | Dependent-Marking | Head-Marking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word order type | Head-initial | Head-final | Free |

| Exemplar | English | Japanese | Mohawk |

| Spanish | Spanish | ||

| Quechua | Quechua |

| +Singular | +Female | −Female |

|---|---|---|

| +definite | la | el |

| −definite | una | un |

| −Singular | +Female | −Female |

| +definite | las | los |

| −definite | unas | unos |

| Sex | Region | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Chuquisaca | Cuzco | |||||||||||

| N children | 52 | 52 | 50 | 54 | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||||

| N children | 7 | 9 | 8 | 13 | 22 | 14 | 9 | 13 | 7 | 1 | 1 | |||

| VO-Type Sentences | OV-Type Sentences | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO | SVO | VSO | VOS | Total | OV | SOV | OSV | OVS | Total |

| 259 | 19 | 3 | 3 | 284 | 1402 | 55 | 9 | 10 | 1476 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalt, S.E.; Geary, J.A. Typological Shift in Bilinguals’ L1: Word Order and Case Marking in Two Varieties of Child Quechua. Languages 2021, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010042

Kalt SE, Geary JA. Typological Shift in Bilinguals’ L1: Word Order and Case Marking in Two Varieties of Child Quechua. Languages. 2021; 6(1):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010042

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalt, Susan E., and Jonathan A. Geary. 2021. "Typological Shift in Bilinguals’ L1: Word Order and Case Marking in Two Varieties of Child Quechua" Languages 6, no. 1: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010042

APA StyleKalt, S. E., & Geary, J. A. (2021). Typological Shift in Bilinguals’ L1: Word Order and Case Marking in Two Varieties of Child Quechua. Languages, 6(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6010042