Abstract

Spanish speakers constitute the largest heritage language community in the US. The state of Florida is unusual in that, on one hand, it has one of the highest foreign-born resident rates in the country, most of whom originate from Latin America—but on the other hand, Florida has a comparatively low Spanish language vitality. In this exploratory study of attitudes toward Spanish as a heritage language in Florida, we analyzed two corpora (one English: 5,405,947 words, and one Spanish: 525,425 words) consisting of recent Twitter data. We examined frequencies, collocations, concordance lines, and larger text segments. The results indicate predominantly negative attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension, but predominantly positive attitudes on the solidarity dimension. Despite the latter, transmission and use of Spanish were found to be affected by pressure to assimilate, and fear of negative societal repercussions. We also found Spanish to be used less frequently than English to tweet about attitudes; instead, Spanish was frequently used to attract Twitter users’ attention to specific links in the language. We discuss the implications of our findings (should they generalize) for the future of Spanish in Florida, and we provide directions for future research.

1. Introduction

Relocation of people as a result of globalization and (voluntary as well as involuntary) migration almost inevitably leads to shifts in language use (Fishman 2001; United Nations (ND) n.d.). Movement of people, to some extent, disrupts intergenerational language-in-culture continuity (Fishman 1991) due to the fact that in many cases, in the host society, the migrants’ language is a minority language—and specifically, a heritage language—within a new majority language context. Heritage languages are defined as “languages other than the dominant language (or languages) in a given social context,” which tend to be learned in the home environment (Kelleher 2010, p. 1). Fishman’s three-generation model elucidates how heritage languages commonly disappear over three generations as a result of language shift and lacking intergenerational transmission (Fishman 1991; Fishman 2001; see also Kircher 2019). The reasons for this, and the process itself, are complex. Initially, the first generation encounters circumstances that impact their access to education, integration into professional contexts, and upward mobility—which inevitably leads to socio-economic disadvantages. If they are not already speakers of the host society’s majority language, the first generation of newcomers tends to adapt the use of their heritage language, frequently restricting it to their home and their own social circles (i.e., minoritized contexts), with limited presence of the majority language (Stavans and Ashkenazi 2020).

The second generation usually grows up to be bilingual in the heritage language and the host society’s majority language. This is known as heritage bilingualism (Kelleher 2010; see also Rothman 2009; Polinsky 2011). The second generation also tends to face a multitude of challenges. For example, many heritage bilinguals feel peer pressure to let go of their heritage language due to stigmatization (Flores and Rosa 2015) and negative attitudes (Kircher 2019). This, in turn, can negatively impact their psychological well-being (De Houwer 2015). The difference in social status between the society’s majority language and the heritage language (as well as the social stigma frequently attached to the latter) is also often reflected in individuals’ linguistic proficiencies: Many struggle to reach and maintain a certain degree of proficiency in their heritage language (Benmamoun et al. 2013; Sherkina-Lieber 2020). Moreover, societal disadvantages do not disappear with the second generation being bilingual: Educational or professional opportunities tend to be held and controlled by majority language-speaking individuals without a recent migration background (Fishman 2001)—and heritage language speakers are often not perceived to belong to this group (Fishman 2001; Benmamoun et al. 2013).

With this conflict in identity arises another challenge: Many simply do not pass on active knowledge of the heritage language to their children, hoping that being a speaker of the majority language will ameliorate their prospects in life (Fishman 2001; Campbell-Montalvo 2020). Therefore, the third generation often only has a passive knowledge of the heritage language—or it is entirely monolingual in the society’s majority language.

The societal integration of heritage languages often depends on their status and the category to which they belong. Fishman (2001) identifies three categories of heritage languages: (i) immigrant, (ii) indigenous, and (iii) colonial heritage languages. Immigrant heritage languages are brought to a particular context by newcomers to a host society, indigenous heritage languages arise as a result of systematic political and societal oppression of indigenous populations, and colonial heritage languages are ones that are brought to other linguistic contexts as a result of colonial movements. However, while the latter are, strictly speaking, heritage languages, they are not minoritized in the way that immigrant and indigenous heritage languages are, and they thus do no hold the same minoritized status as the other two categories of heritage languages. In some cases, however, a colonial heritage language can, at a later point, become an immigrant heritage language. Spanish in the US is an example of this: While Spanish is used in contexts around the globe as a result of colonization, and it is in fact the world’s third most widely-spoken language (Rivera-Mills 2012), Spanish in the US is nevertheless considered an immigrant heritage language (Fishman 2001; Kelleher 2010; Valdés 2001).

Spanish arrived in the US during the 16th century, when explorer Ponce de León disembarked onto the east coast of Florida. Over the course of the subsequent three centuries, Spanish spread within the US—partly as a result of Spanish speakers leaving Florida for other locations, but primarily as a result of the Mexican-American War in 1848 and the annexation of Cuba and Puerto Rico. Subsequently, significant waves of the spread of Spanish occurred during World War I and then again in the 1980s, when many Spanish speakers moved from Latin America to the US in the hope of better socio-economic opportunities (Potowski and Carreira 2010). There is still ongoing immigration of Spanish-speaking individuals to the US—and nowadays, with approximately 14% of the US population using the language at home, Spanish speakers constitute the largest heritage language community in the country (U.S. Census Bureau 2019a).

Florida, the first home of Spanish in the US, has one of the highest foreign-born resident rates (20.5%), with the majority of these individuals coming from Latin America (75.6%; U.S. Census Bureau 2019b). Nevertheless, according to the latest census, the state now has a comparatively low Spanish language vitality and seemingly low rates of intergenerational transmission (with only 22.5% of the state’s population using the language at home, and no more than 3.5% of 5- to 17-year-olds doing so—compared to 28.8% and 5.8%, respectively, in California, and 29.2% and 6.1%, respectively, in Texas; U.S. Census Bureau 2019b). In other US states, such as California and Texas, the majority of Spanish speakers come from Mexico and other Central American backgrounds (Lopez et al. 2013). Florida’s Hispanic and Latinx population also includes individuals from these backgrounds (13% from Mexico and 10% from other Central American countries)—but these are far outnumbered by individuals from the Caribbean (28% are Cuban, 21% Puerto Rican, and 4% Dominican) as well as from South America (18%) and other Spanish-speaking origins (6%; U.S. Census Bureau 2019b). As a consequence of this highly diverse Hispanic and Latinx population, there is not one particular variety of Spanish that is spoken in Florida, but rather multiple varieties of Spanish which coexist (see, e.g., Carter and Lynch 2015).

Studies suggest that many Spanish speakers in the US hold negative attitudes toward their own language (see, e.g., Surrain 2018, for a literature review). There is also some recent research that has investigated attitudes toward different varieties of Spanish among Spanish speakers in Miami, the cultural center of Florida, finding that Latinx undergraduate students in this city perceived peninsular Spanish to hold a higher prestige than other varieties, such as Columbian and Cuban Spanish (Callesano and Carter 2019). However, we are not aware of any work that has systematically examined attitudes toward Spanish as a language (rather than different varieties of it)—either in Miami or elsewhere in the state. Yet, a study that considers attitudes toward the Spanish language as such, and that takes account of Florida as a whole, has the potential to shed light on the underlying reasons for the low vitality of Spanish in this state.

In this article, we therefore present the first exploratory investigation of this kind, in which we employed a corpus-assisted discourse study of Twitter data to find out about the language attitudes of Spanish-speaking and English-speaking Floridians throughout the state. Our aim was to examine the nature of these attitudes as well as the underlying reasons for the language’s low vitality in Florida. To provide the necessary theoretical background, we begin by outlining the key concepts of attitude theory that are of relevance to our research before explaining the methodology of our study. We then provide an analysis of our findings—and the subsequent discussion focuses on the potential implications our findings can be seen to have as well as the future research they necessitate.

2. Theory

Language attitudes are traditionally defined as “any affective, cognitive or behavioural (i.e., conative) index of evaluative reactions towards different varieties and their speakers”—or, more inclusively, their users (Ryan et al. 1982, p. 7). As this definition indicates, language attitudes are considered to comprise three components: affect, that is, feelings concerning varieties and their users; cognition, that is, beliefs about varieties and their users; and conation, that is, behavior (or behavioral intentions) regarding varieties and their users (see, e.g., Bohner 2001).1 The study of attitudes is of great importance because all intergroup relations are characterized by—positive as well as negative—prejudices (i.e., feelings), stereotypes (i.e., beliefs), and discrimination (i.e., behaviors) (Bourhis and Maas 2005).

The inclusion of the speakers, or language users, in the aforementioned definition of language attitudes, is due to the close link between language and social identity—that is, those parts of an individual’s self-concept that are associated with their membership in particular social groups (Tajfel and Turner 1986). Based on a large body of research evidence, it has long been acknowledged that language is a key symbol of social identity, “an emblem of group membership” (Grosjean 1982, p. 117). Attitudes toward particular varieties thus effectively reflect attitudes toward their users (Garrett et al. 2003). This evinces that language attitudes are not founded on linguistic or aesthetic quality per se, but that they are instead based upon knowledge of the social connotations that specific varieties hold among those who are familiar with them, upon “the levels of status, prestige, or appropriateness that they are conventionally associated with in particular speech communities” (Cargile et al. 1994, p. 227). Such connotations are not set in stone, and language attitudes can change as social mores change (Kircher 2016). Yet notably, because people react to language as if it were an indicator of the social characteristics of its users, discrimination on the grounds of language is in effect a proxy for discrimination based on individuals’ (perceived) ethnicity, migration background, social status, and other salient social group memberships (Kircher and Zipp forthcoming; see also Kutlu 2020; Kutlu et al. forthcoming).

Language attitudes are commonly assumed to have two main evaluative dimensions: status and solidarity. On the one hand, a variety with high status is one that individuals associate with power, economic opportunity, and upward social mobility. Consequently, attitudes on the status dimension are connected with a variety’s utilitarian value (Gardner and Lambert 1972). On the other hand, a variety toward which individuals hold positive attitudes on the solidarity dimension is one that elicits feelings of attachment and belonging: It holds “vital social meaning and … represent[s] the social group with which one identifies” (Ryan et al. 1982, p. 9). Attitudes on the solidarity dimension are thus linked with in-group loyalty and illustrate the connection between language and social identity. Status and solidarity are not mutually exclusive: Research has shown that under certain circumstances, it is possible for varieties to be evaluated positively (or negatively) on both dimensions (see, e.g., Giles and Watson 2013, for a more detailed discussion).

The importance of language attitudes, as Cargile and Giles (1997, p. 195) put it, lies in the fact that they “bias social interaction—and often in those contexts where important social decision-making is required.” Particularly for heritage language speakers, negative attitudes toward their heritage language can have highly detrimental effects. Firstly, attitudes influence which language(s) an individual uses in which contexts and with whom, including the decision of which language(s) they pass on to their children (De Houwer 1999; Kircher 2019). In the long run, the influence of such microlevel linguistic choices has severe implications at the macro-level. Language attitudes thus play a key role in whether heritage language communities undergo language shift (and sometimes loss), or whether they are able to maintain their languages (see, e.g., Sallabank 2013). Secondly, in contexts where individuals do decide to pass on their heritage languages to their children, negative attitudes toward the specific languages involved—as well as negative attitudes toward bilingualism as such—not only impact children’s early bilingual development but also affect their psychological well-being (De Houwer 2015, 2017).

3. Methodology

In order to investigate attitudes toward Spanish as a heritage language in Florida and assess their likely implications, we conducted a corpus-assisted discourse study of Twitter data. Twitter is a microblogging site on which users can post messages—known as tweets—of up to 280 characters. Specifically, we examined two corpora: one comprising English tweets and the second consisting of Spanish tweets.

We use the term corpus to mean “a collection of texts (a ‘body’ of language) stored in an electronic database” (Baker et al. 2006, p. 48), which can be “analysed using a computer” (Brezina 2018, p. 15). While corpus-linguistic analysis can very effectively reveal discursive patterns in large amounts of data, it is “not sufficient in explaining or interpreting the reasons why certain linguistic patterns were found . . . because this type of analysis does not take into account the social, political, historical and cultural context of the data under consideration” (Baker 2010, p. 141). We, therefore, combined the use of quantitative corpus methods with the qualitative examination of our data—an approach that broadly fits under the remit of corpus-assisted discourse study (see, e.g., Vessey 2016a; Jaworska and Themistocleous 2018).

This approach has been used very effectively to investigate language ideologies (e.g., Orpin 2005; Vessey 2015; Kircher and Fox 2019). Yet, apart from Jaworska and Themistocleous (2018), whose focus was rather different,2 there does not seem to be any previous research that has employed a corpus-assisted discourse study to examine language attitudes. Specifically, we are not aware of any such study that has investigated language attitudes based on social media data. Examining social media data has the advantage of providing insights into the unprompted, spontaneous attitudes of a wide range of individuals (Durham forthcoming). By means of our corpus-assisted discourse study of Twitter data, we thus aimed to shed light on attitudes in a manner that is largely unaffected by the social desirability biases that so often influence the expression of language attitudes when direct methods of elicitation—such as questionnaires, interviews, and focus groups—are employed (Baker 1992).

Specifically, our research questions were the following:

- Q1: Do the data reveal attitudinal differences with regard to the status and the solidarity dimension?

- Q2: Are attitudes expressed differently in the English and the Spanish corpus?

- Q3: Do the data provide possible explanations for the low vitality of Spanish in Florida?

3.1. Data Collection

We decided to collect Twitter data because the data from this microblogging site (unlike many other social media data) are within the public domain (see, e.g., Durham forthcoming). Following ethical guidelines regarding online data collection (Spilioti and Tagg 2017), we only started collecting data once we had received Institutional Review Board clearance, which was also approved by Twitter. Data were collected using the rtweet package (Kearney 2019) in R (with our code being available on OSF website, see Supplementary Materials section), and it took place over a period of 12 weeks from mid-July 2020 until early October 2020.

In order to geotag tweets to Florida, we used the lookup_coords() function, selecting Florida as the location. This function uses Twitter’s geotag data and selects locations that are specified within the function. For instance, lookup_coords (“New York”) will return data that were produced by someone tweeting from New York. Of course, in principle, this means that a corpus based on geo-tagged data can also include data from tweeters simply visiting the location under investigation. However, firstly, the number of visitors to Florida is likely to have been comparatively low during the period of investigation due to the COVID-19-related travel restrictions; and secondly, it is unlikely that so many visitors to Florida would tweet about the Spanish language that it would significantly interpolate our findings.

We used the search_tweets() function to enter our search words, which included pertinent terms such as “Spanish speakers,” “Spanish-speaking,” “Español,” “Hispanic,” “Latino,” and “Latina.” To avoid the same tweet being captured more than once, we used the include_rts function as FALSE, which eliminates retweets. It could be argued that retweets (in many cases) indicate endorsement of the attitudes expressed in the original tweet. Nevertheless, we decided to exclude retweets because, in this exploratory study, we were primarily interested in tweeters’ original expressions of their attitudes toward Spanish.

The N (i.e., number) function was kept at the default setting of 18,000, meaning that 18,000 tweets were downloaded per 15 min. Based on these downloaded tweets, two corpora were created: one containing English data (183,278 tweets amounting to 5,405,947 words) and one including Spanish data (20,959 tweets amounting to 525,425 words).3 The fact that the Spanish corpus is significantly smaller than the English corpus—even though we collected tweets from the same location during the same exact time period—did not hinder data analysis.

3.2. Data Analysis

While there is no single methodology for how to “do” corpus analysis (Hunston and Thompson 2006, p. 3), there are some commonly used procedures, namely, the determination of frequencies—that is, highly frequent words and phrases; and the analysis of collocations—that is, the words with which pertinent terms tend to co-occur. These are of interest because “words that are repeated … are understood to have a particular function within the society producing the texts,” and because “isolated words are not understood to be meaningful on their own; rather, meaning is understood to be achieved through the repeated use of words in fixed or semi-fixed phrases” (Vessey 2016a, p. 5).4

Thus, making use of the Word List tool in the corpus linguistics program AntConc (Anthony 2019), we began by examining what words occur frequently in our corpora. Ignoring articles, conjunctions, and other words that are not relevant in this context, we focused solely on frequently-occurring terms that are clearly linked with tweeters’ attitudes toward Spanish. We grouped commonly occurring words together into the broad semantic categories of attitudes on the status dimension (for descriptors that link to themes such as economic opportunity and utilitarian value) and attitudes on the solidarity dimension (for descriptors that link to themes such as in-group loyalty). To facilitate comparison between the two differently-sized corpora, all frequencies were normalized, and we considered frequencies in words per ten thousand (wptt). Subsequently, we used AntConc’s Concordances tool to investigate the collocates of the most pertinent terms, employing the standard search window of five spaces to the left and to the right of the search term (Baker 2006). Mutual Information (MI) scores allowed us to establish that words were not merely co-occurring by chance. Such MI scores use a logarithmic scale to express “the ratio between the frequency of the collocation and the frequency of random co-occurrence of the two words in combination” (Gablasova et al. 2017, p. 163). MI scores of 3 or above are commonly taken as evidence of statistical significance (Vessey 2015). Finally, we considered selected concordance lines—that is, lines that “present an individual lexical item within its ‘co-text’ across numerous texts” (Vessey 2016a, p. 6), as well as larger discourse segments in the form of entire tweets.

4. Results

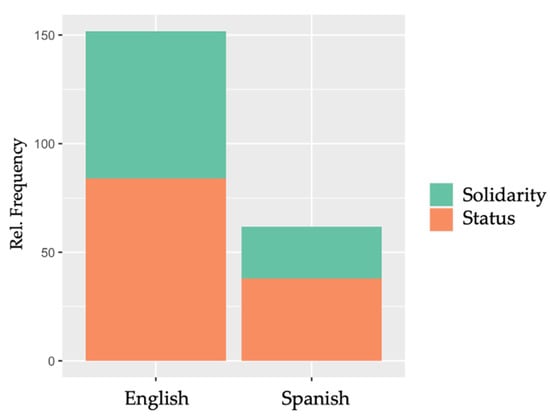

One of the most immediate findings to emerge from the data is that both corpora contain more descriptors that pertain to the status dimension than to the solidarity dimension (see Figure 1: In the English corpus, the status-related descriptors amount to 83.92 wptt and the solidarity-related descriptors to 67.81 wptt; in the Spanish corpus, the status-related descriptors amount to 37.82 wptt and the solidarity-related descriptors to 23.91 wptt). Notably, the English corpus contains higher relative frequencies of both status- and solidarity-related descriptors.

Figure 1.

Relative frequencies of status-related and solidarity-related descriptors in the English and the Spanish corpus.

4.1. Attitudes on the Status Dimension

As noted above, a language with high status is one that individuals associate with power, economic opportunity, and upward social mobility. Attitudes on the status dimension are thus connected with a language’s utilitarian value (Gardner and Lambert 1972). At first sight, the fact that both corpora contain more frequently-occurring descriptors that pertain to the status dimension than to the solidarity dimension may give the impression that positive attitudes toward Spanish prevail in terms of status. However, a closer investigation of the data indicates that this is not the case. In fact, neither of the two corpora contains any descriptors that directly and exclusively refer to positive attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension. As Table 1 shows, the status-related descriptors in both corpora can be divided into three semantic categories: namely, directly negative, negative and positive, and indirectly positive.

Table 1.

Absolute and relative frequencies of status-related descriptors in the English and the Spanish corpus.

Both corpora contain one frequently-occurring descriptor which suggests that the tweeters associate the Spanish language with a lack of economic opportunity, namely, unemployment/desempleo (Table 1). This indicates negative attitudes toward Spanish in terms of its status, as illustrated by the following tweet:

“In April, national unemployment for Latinos peaked at 18.5%. For Latina women, it was even higher, at 20.”

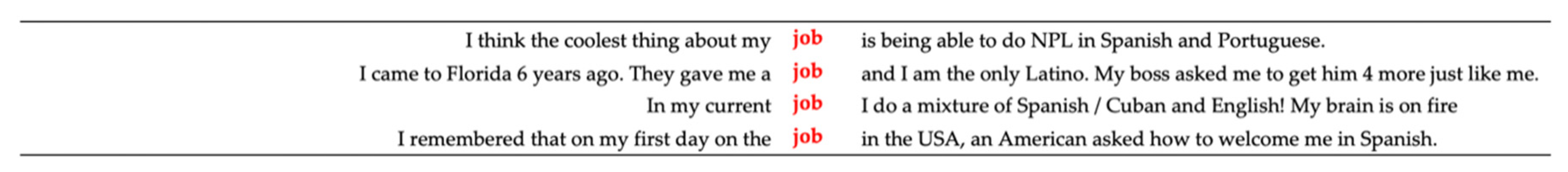

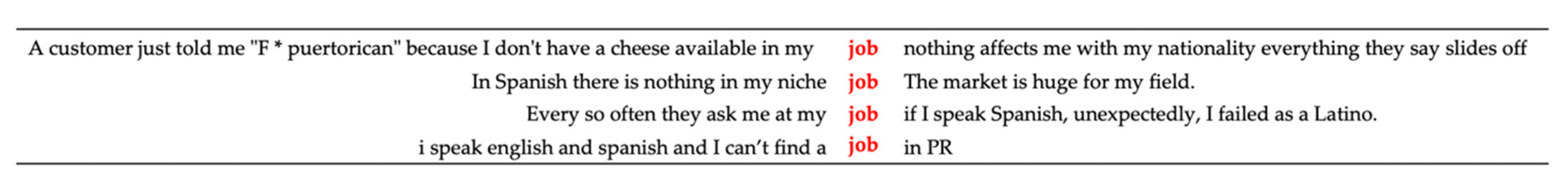

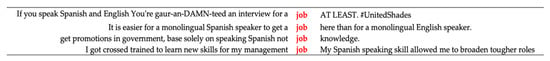

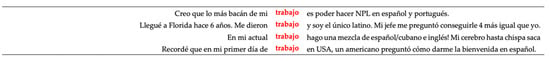

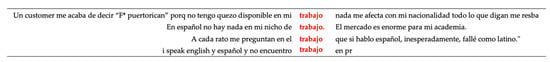

Both corpora also contain several frequent descriptors relating to the status dimension that are sometimes used in contexts in which they convey negative attitudes, while at other times, they are used in contexts where they indicate positive attitudes (see Table 1). These descriptors make reference to employment (i.e., work/trabajo, working/trabajando, and job) as well as education (i.e., school/escuela, college/universidad, and education/educación). The latter semantic category relates to the status dimension in the sense that education is usually considered to be necessary in order to achieve economic opportunity and upward social mobility. To exemplify the different uses of certain descriptors in the English corpus, Figure 2 shows concordance lines illustrating the use of job in ways that indicate positive attitudes, while Figure 3 shows concordance lines in which the same term is used in a manner that indicates negative attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension. To exemplify the different use of certain descriptors in the Spanish corpus, Figure 4 shows concordance lines illustrating the use of trabajo (“work”) in ways that indicate positive attitudes, while Figure 5 shows concordance lines in which the same term is used in a manner that indicates negative attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension (see Appendix A for translations).

Figure 2.

Concordance lines for job that indicate positive attitudes on the status dimension.

Figure 3.

Concordance lines for job that indicate negative attitudes on the status dimension.

Figure 4.

Concordance lines for trabajo that indicate positive attitudes on the status dimension.

Figure 5.

Concordance lines for trabajo that indicate negative attitudes on the status dimension.

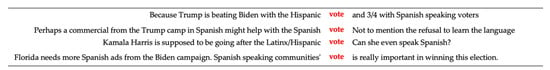

Notably, both corpora contain several frequently-occurring descriptors relating to the theme of politics—and specifically the 2020 US presidential elections—that indirectly allow us to draw conclusions regarding tweeters’ attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension (see Table 1). These terms (e.g., election/elecciones, voters/votantes, and voting/votación) are relevant in this context because they make reference to the role that Spanish plays in politicians’ (re-)election by Floridians, as illustrated by the concordance lines in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Concordance lines for vote that illustrate the role of Spanish in politicians’ (re-)election.

Florida is one of the so-called battleground states—that is, those states in which even a small number of votes can determine the outcome of the elections. As the quotes from some tweeters in our corpora illustrate, the Spanish language is seen to play a role in the voting decisions made by Spanish speakers, and the use of Spanish is found to be crucial in attracting more voters toward presidential candidates. For instance, the first tweet below shows that political parties that conduct more outreach toward Latinx groups have a higher likelihood of getting votes from those communities, contributing to their electoral success. The tweet indicates that without their support, the election results could potentially change, thus indirectly demonstrating positive attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension:

“Because Trump is beating Biden with the Hispanic vote and 3/4 with Spanish speaking voters (did the poll in Spanish) Democrats made another stupid move and made Bush Republican Anna Navarro their Latino outreach. Democrats need to do better if they want to win.”

The same theme is present in the tweet below, which is taken from our Spanish corpus:

“Trump se encuentra en el sur de Florida en busca del voto latino, uno de los bloques de votantes más importantes del estado https …” (Trump finds himself in South Florida looking for the Latin vote, one of the most important blocks of voters in the state https …)

Predominantly Spanish-speaking media outlets also seem to be using Twitter to attract Spanish-speaking voters’ attention. The underlying idea is that once voters’ attention has been captured, they are more likely to vote for the political party that the media outlet is associated with. This indicates the power that Spanish-speaking voters are perceived to hold, which can be interpreted indirectly as an indication of status. This is exemplified in the following tweet:

“Telemundo seems to want their Spanish speaking audience to vote for Trump. Remember this is one of only two Spanish networks in America. They have a lot of power.”

An examination of lexical collocates in the English corpus supports our overall findings. We investigated the collocates of “Spanish,” “Spanish speakers,” and “Spanish-speaking,” and while we found no collocations for “Spanish” and “Spanish speakers” that provide insights into language attitudes, the expression “Spanish-speaking” collocates significantly with three pertinent terms, namely viewers (MI: 7.4), voters (MI: 3.0), and students (MI: 3.4). Viewers and voters are both part of the aforementioned, indirectly positive semantic category relating to the important role of Spanish in the 2020 presidential elections; the term students falls into the aforementioned semantic category of education—a prerequisite to economic opportunity and upward mobility.

On a related note, the term “Florida” itself also collocates with voters both in the English corpus (MI: 6.7) and in the Spanish corpus (MI: 8.7). This can be seen as further evidence for the importance of Florida, and the Spanish-speaking voters in the state, in the 2020 presidential elections. However, the term “Florida” does not collocate with any other pertinent terms that provide insights into the role of Spanish in this state.

In the Spanish corpus, we investigated the lexical collocates of the terms “español,” “(hispano-)hablantes,” and the lemma “hablar español,”5 which can be considered equivalent to the aforementioned terms examined in the English corpus (i.e., “Spanish,” “Spanish speakers,” and “Spanish-speaking”). Notably, in the Spanish corpus, none of these terms have significant collocates pertaining to attitudes on the status dimension. The collocates that are significant in the English corpus all have MI scores below the level of statistical significance in the Spanish corpus.

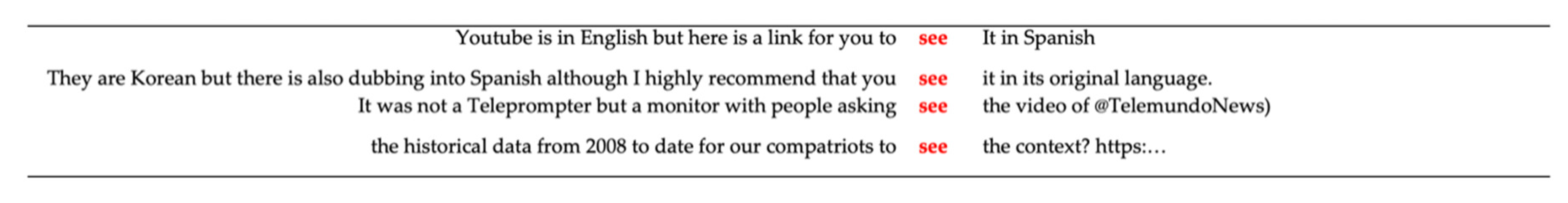

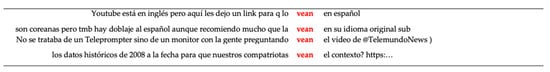

The lack of pertinent collocates in the Spanish corpus is likely linked to the fact that the relative frequencies of status-related descriptors were much lower in the Spanish corpus than in the English corpus, for each of the semantic categories—directly negative, negative and positive, and indirectly positive (see Table 1). This, in turn, is likely to be a reflection of the fact that Spanish—at least in the tweets that constitute our corpus—is commonly used for one specific purpose, which is largely absent from our English data: namely, to direct users to specific links which allow them to view something in Spanish. This is illustrated by the fact that ve (“watch!”) and vean (“y’all watch!”) together have a relative frequency of 2.9 wptt, and these terms collocate significantly with en video (“on video”) (MI: 6.65) and en link (“through the link”) (MI: 8.07). The concordance lines in Figure 7 illustrate this point.

Figure 7.

Concordance lines for vean that illustrate the use of tweets in the Spanish corpus directing readers to links.

4.2. Attitudes on the Solidarity Dimension

As noted above, a language toward which individuals hold positive attitudes on the solidarity dimension is one that elicits feelings of attachment and belonging, and which individuals associate with the social group with which they identify. Attitudes on the solidarity dimension are thus linked with the aforementioned social identity and in-group loyalty (Ryan et al. 1982). In both corpora, the relative frequencies of solidarity-related descriptors are lower than the relative frequencies of status-related descriptors (see Figure 1). However, it is notable that the solidarity-related descriptors in both corpora clearly and exclusively make reference to positive attitudes toward Spanish. As Table 2 shows, the frequently-used positive descriptors can, in both corpora, be divided into two semantic categories: namely community and family.

Table 2.

Absolute and relative frequencies of solidarity-related descriptors in the English and the Spanish corpus.

The category of community contains not only the words community/comunidad and communities/comunidades themselves, but also descriptors relating to different ways in which Spanish speakers are linked with each other (e.g., culture/cultura and friends/amigas/amigos) (Table 2). The first tweet below illustrates how the language connects the tweeter to their community and allows them to bond with other community members:

“It is important speaking with them one on one (in Spanish) and connecting to the community in Spanish. When I was a kid, this was the only way for me to connect with my people.”

The second tweet illustrates how speaking Spanish affords the tweeter a sense of acceptance, attachment, and belonging to their community:

“I am half Colombian half Mexican. I start speaking Spanish and they’re like, where’d you learn that. It’s always so nice to see that your community and friends appreciate your language. This is my city, I belong here.”

Both of these tweets exemplify tweeters’ positive attitudes toward Spanish on the solidarity dimension, and they show clearly that the language is perceived to hold vital social meaning. Notably, while numerous tweets containing discourses of this kind are present in the English corpus, none could be found in the Spanish corpus.

We have included the frequently-occurring descriptor heritage/patrimonio in the category of family (Table 2), although it could arguably also be included in the category of community. Either way, it clearly suggests positive attitudes on the solidarity dimension. This is illustrated by the next Tweet, which discursively constructs the role of the Spanish language in the tweeter’s social identity:

“Speaking Spanish is my heritage. It is what makes me who I am.”

The category of family also contains not only the term families/familias itself but also descriptors referring to specific family members (i.e., mom/mamá, parents/padres, and children/niñas/niños) as well as generation/generación (Table 2). Overall, the data reveal that families play a crucial role in transmitting the Spanish language to the next generation and that this is felt to be important—as illustrated, for example, by this tweet:

“My miami family made me embrace more my Spanish side and I realized how much I’ve been missing out.”

However, it should be noted that while some families transmit Spanish to their children and speak the language at home, our data also suggest that others are more careful about this—and some even consciously avoid it out of concern that speaking Spanish may harm their children’s future prospects. The tweet below shows how societal views of Spanish, particularly in education, have led the tweeter’s mother to reconsider the use of Spanish at home:

“I remember in elementary school being forbidden from speaking Spanish with my mom. They actually threatened to send child services to accuse my mom of leaving me unequipped to deal with American society for speaking Spanish to me.”6

Moreover, the following tweet illustrates that some families are not only concerned about the potentially negative consequences of speaking the Spanish language itself but also about the ’foreign’ accent it might lead to in English:

“My mom encouraged me to speak English at home to avoid an accent.”

An examination of lexical collocates in the English corpus again supports our overall findings: While there are no notable collocations for “Spanish” and “Spanish speakers,” the expression “Spanish-speaking” collocates very strongly with two pertinent terms, namely friends (MI: 4.3), which falls into the aforementioned semantic category of community, and family (MI: 4.1), which falls into the eponymous semantic category.

In the Spanish corpus, an investigation of the terms “español,” “(hispano-) hablantes,” and the lemma “hablar español” did not yield any statistically significant collocates pertaining to attitudes on the solidarity dimension. This is a parallel to the aforementioned findings regarding the status dimension. Again, this may be due to the much lower relative frequencies of descriptors relating to this dimension of attitudes, and again, this is in turn likely to be linked with the fact that the Spanish tweets in our corpus are so frequently used for the purpose of directing users to specific links which allow them to view something in Spanish.

5. Discussion

The aim of our study was to investigate attitudes toward Spanish as a heritage language in Florida by means of a corpus-assisted discourse study of English and Spanish Twitter data. Certainly, there are some limitations to the work presented here. For instance, the fact that we collected data in the summer and autumn before the 2020 US presidential elections has led to the frequency of terms that may not have been as common at other points in time. To ascertain this, more longitudinal data would need to be collected. Moreover, while investigating attitudes by analyzing social media data has numerous advantages (as discussed above), it also has the disadvantage that the data are not representative. For example, not everyone has access to the internet and the necessary electronic devices, which leads to an under-representation (or potentially even lacking representation) of many socially disadvantaged parts of the population. In addition, not all age groups use social media—and even among those who do, it is likely that they employ a microblogging site like Twitter with different frequencies and for different purposes. This may lead to an under-representation of certain age groups (see also Durham forthcoming). Due to these limitations, we can make no claims regarding the generalization of our findings. Moreover, with Twitter data, it is not possible to ascertain the tweeters’ L1s and proficiencies in the language(s) under investigation. Thus, for instance, we could not establish whether certain tweeters used English because they were unable to use Spanish or because they decided against it. While we set out to investigate attitudes toward Spanish in Florida overall, and not just among Spanish speakers, this means that we cannot ascertain attitudinal differences between different linguistic groups. Yet, limitations notwithstanding, this exploratory study offers meaningful insights into attitudes toward Spanish as a heritage language in Florida.

At the outset, we asked three research questions. RQ1 asked: “Do the data reveal attitudinal differences with regard to the status and the solidarity dimension?” The frequently-used descriptors, the collocations of the term “Spanish-speaking,” and the qualitative data all suggest that with regard to the status dimension, our tweeters hold predominantly negative attitudes toward Spanish. They commonly seem to associate the language with lacking economic opportunities. Positive attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension are almost exclusively observed indirectly when reference is made to the role of the language in the 2020 presidential elections. For the solidarity dimension, on the other hand, the frequently-used descriptors, the collocations of the term “Spanish-speaking,” and the qualitative data all provide evidence of predominantly positive attitudes toward the Spanish language. Our findings suggest that the language provides tweeters with a sense of belonging to their family and their community, and that their linguistic heritage is viewed as an integral part of their social identity.

The fact that, overall, tweeters in Florida seem to hold comparatively negative attitudes toward Spanish on the status dimension can be explained by the circumstances we outlined in the introduction—including unequal access to education, restricted upward mobility, and limited socio-economic prospects for the first generation of migrants, and challenges for their descendants because educational and professional opportunities tend to be controlled by majority language-speaking individuals without a recent migration background (Fishman 2001). In this light, it is not surprising that Spanish in Florida appears not to be associated with power, economic opportunity, and upward social mobility—and why the tweeters whose data we collected in our corpora do not perceive it to hold high utilitarian value. By contrast, the fact that overall, tweeters in Florida seem to hold predominantly positive attitudes toward Spanish on the solidarity dimension can be explained by the role that the language plays within individuals’ families and communities. It is as a result of this that tweeters perceive it to provide them with a sense of belonging and in-group loyalty: It represents the pertinent social group(s) with which they identify.

With regard to the practical implications of our findings, it is important to bear in mind that attitudes on the solidarity dimension can be crucial determinants of why languages persist in intergroup situations, regardless of their status (see, e.g., Cargile et al. 1994). Tweeters’ positive attitudes toward Spanish in Florida could therefore be interpreted as boding well for the language’s future—were it not for the other data we found, which suggest that the intergenerational transmission of Spanish is affected by families’ fears of negative repercussions at the societal level if their children use Spanish, or even if they speak English with a Spanish accent. This finding is likely to be a consequence of a strong societal pressure to assimilate, and it suggests that despite the vital social meaning that Spanish holds for them, many families in Florida are likely to follow Fishman’s aforementioned three-generation model of language shift (Fishman 1991, 2001). Based on the work of De Houwer (2015, 2017), it is very probable that this impacts the psychological well-being of migrants who are heritage language speakers, and of their descendants.

With regard to language attitude theory, it is noteworthy that the findings of our study show that the dimensions of attitudes which have been found in offline data—that is, status and solidarity—are also clearly present in online data. We are planning to conduct further research into attitudes toward Spanish in Florida by means of different, direct methods to shed light on whether and to what extent expressions of language attitudes in online spaces differ from those in offline spaces—because so far, little is known about whether the former mirror the latter, or whether the (relative) anonymity afforded in online spaces affects the expression of language attitudes. Such a mixed-methods approach will allow for more nuanced and comprehensive insights than any method could provide on its own (see, e.g., Kircher and Hawkey forthcoming).

RQ2 asked: “Are attitudes expressed differently in the English and the Spanish corpus?” We found that, overall, the same trends can be observed in both corpora regarding the relative frequencies of status-related versus solidarity-related descriptors. Both corpora also contain frequently-used descriptors pertaining to the same semantic categories: that is, directly negative, negative and positive, and indirectly negative on the status dimension; as well as community and family on the solidarity dimension. However, the relative frequencies of all categories of descriptors were much higher in the English corpus than in the Spanish corpus, and there was more evidence of the discursive construction of language attitudes in the former than in the latter. Moreover, as the different sizes of our corpora demonstrate, Spanish was used much less frequently on Twitter than English within Florida during the time period of our data collection. While we cannot generalize from our data to other time periods, both language practices and metalanguage in our corpora suggest that Twitter data reflect the aforementioned low Spanish vitality that has been observed in Florida more generally.

As noted above, behavior constitutes one of the components of language attitudes. Along with the expression of the beliefs and feelings discussed in Section 4, this aspect of the tweeters’ linguistic behavior—that is, their predominant use of English rather than Spanish in their tweets—might be interpreted as an indication of their negative attitudes toward the Spanish language. However, it is impossible to be certain about this since other factors, such as the tweeters’ lacking knowledge of the language or insecurity about their Spanish writing skills, could also be at the root of this behavior. It is also probable that the tweeters’ (imagined) audiences played a role in their language choices. Moreover, it should be noted that—despite growing multilingualism—English remains the dominant language of the internet, including communication on Twitter (Lee 2016). Further research is thus necessary to clarify whether the extent to which Spanish is used in Floridians’ tweets really is an indication of their language attitudes.

In any case, it is notable that in our corpus, Spanish is frequently used for a purpose that sets it apart from the English corpus: namely, to direct Twitter users’ attention to links where they can gather information in Spanish. This is a consequence of our data collection method that we had not foreseen. Vessey (2016a, 2021) attests to this same use of tweets in Canadian Twitter corpora—but in her data, it was not found to be predominant in a heritage or minority language. Again, further research using different, direct methods of attitude elicitation will allow us to explore differences between English and Spanish data in more detail, and obtain more nuanced information on whether and how attitudes are expressed in these two languages.

RQ3 asked: “Do the data provide possible explanations for the low vitality of Spanish in Florida?” Regrettably, it is not possible to answer this question based on the data investigated here. There are no correlates of the term “Florida” that allow us to draw any conclusions about what makes Florida different from other states such as California and Texas, and none of the information that surfaced during our analysis of the corpora provides any relevant insights. Yet, based on the socio-cultural context, we hypothesize that there are several possible reasons for the comparatively low vitality of Spanish in Florida. As outlined in the introduction, Florida is different from other states because its Hispanic and Latinx community is much more diverse (U.S. Census Bureau 2019b; see also, e.g., Brown and Lopez 2013; Carter and Lynch 2015). It is possible that this diversity results in a population so heterogeneous that it does not offer individuals a sufficiently strong reference point for their social identity, and this could lead to less positive attitudes toward the Spanish language than the attitudes that are found in more homogeneous speaker communities. Another possibility is that the large number of so-called snowbirds—that is, individuals who migrate from colder northern climates to the warmth of Florida for the winter—impacts the community. The (part-time) presence of these snowbirds, many of whom hail from linguistically more homogeneous environments, might lead to a particularly strong pressure to assimilate to English. To find out whether these or other reasons are at the root of Florida’s comparatively low Spanish vitality, we plan to conduct further research that will take a two-pronged approach: Firstly, we will look at larger corpora that comprise data from different states for comparison, and secondly, we will consider smaller segments of Florida so that we can compare areas with different demographic compositions. In combination with the data we plan to collect by means of the aforementioned direct methods, we hope that such an extended corpus-assisted discourse study will allow us to fully answer RQ3.

Supplementary Materials

The R Script for data collection is available online at https://osf.io/4qf7g/?view_only=b0a82c06f13e4e9bbb1fe1bacad56403.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.K. and E.K.; methodology, E.K. and R.K.; software, E.K.; validation, R.K. and E.K.; formal analysis, R.K. and E.K.; investigation, E.K. and R.K.; resources, R.K. and E.K.; data curation, E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, R.K. and E.K.; visualization, E.K.; supervision, R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Florida (protocol code IRB201900180 and date of approval on 7/21/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ongoing research.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to James Hawkey and Rachelle Vessey, as well as two anonymous Languages reviewers, for their insightful and constructive comments on a previous version of this manuscript. We would also like to thank Adriana Ojeda for her support with the Spanish to English translations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anthony, Laurence. 2019. AntConc (Version 3.5.8) [Computer Software]. Tokyo: Waseda University. Available online: https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Baker, Colin. 1992. Attitudes and Language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Paul. 2006. Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Paul. 2010. Sociolinguistics and Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Paul, Andrew Hardie, and Tony McEnery. 2006. Glossary of Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and Challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohner, Gerd. 2001. Attitudes. In Introduction to Social Psychology. Edited by Miles Hewstone and Wolfgang Stroebe. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 239–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bourhis, Richard Y., and Anne Maass. 2005. Linguistic prejudice and stereotypes. In Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society. Edited by Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier and Peter Trudgill. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 1587–601. [Google Scholar]

- Brezina, Vaclav. 2018. Statistics in Corpus Linguistics: A Practical Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Anna, and Mark Hugo Lopez. 2013. Mapping the Latino population, by state, county and city. Pew Hispanic Center 202: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle. 2006. Social stereotypes, personality traits and regional perception displaced: Attitudes towards the “new” quotatives in the U.K. Journal of Sociolinguistics 10: 362–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callesano, Salvatore, and Phillip M. Carter. 2019. Latinx perceptions of Spanish in Miami: Dialect variation, personality attributes and language use. Language and Communication 67: 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Montalvo, Rebecca. 2020. Linguistic Re-Formation in Florida Heartland Schools: School Erasures of Indigenous Latino Languages. American Educational Research Journal, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargile, Aaron Castelan, and Howard Giles. 1997. Understanding language attitudes: Exploring listener affect and identity. Language & Communication 17: 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Cargile, Aaron Castelan, Howard Giles, Ellen B. Ryan, and James J. Bradac. 1994. Language attitudes as a social process: A conceptual model and new directions. Language and Communication 14: 211–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Phillip. M., and Andrew Lynch. 2015. Multilingual Miami: Current Trends in Sociolinguistic Research. Language and Linguistics Compass 9: 369–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, Annick. 1999. Environmental factors in early bilingual development: The role of parental beliefs and attitudes. In Bilingualism and Migration. Edited by Guus Extra and Ludo Verhoeven. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, Annick. 2015. Harmonious bilingual development: Young families’ well-being in language contact situations. International Journal of Bilingualism 19: 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, Annick. 2017. Minority language parenting in Europe and children’s well-being. In Handbook on Positive Development of Minority Children and Youth. Edited by Natasha J. Cabrera and Birgit Leyendecker. New York: Springer, pp. 231–46. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-campos, Manuel, and Jason Killam. 2012. Assessing Language Attitudes through a Matched-guise Experiment: The Case of Consonantal Deletion in Venezuelan Spanish. Hispania 95: 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Durham, Mercedes. Forthcoming. Content analysis of social media data. In Research Methods in Language Attitudes. Edited by Ruth Kircher and Lena Zipp. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fishman, Joshua A. 1991. Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, vol. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, Joshua A. 2001. 300-plus years of heritage language education in the United States. In Heritage languages in America: Preserving a National Resource. Edited by Joy Kreeft Peyton, Donald A. Ranard and Scott McGinnis. Washington, DC and McHenry: Center for Applied Linguistics & Delta Systems, pp. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Nelson, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. Undoing appropriateness: Raciolinguistic ideologies and language diversity in education. Harvard Educational Review 85: 149–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gablasova, Dana, Vaclav Brezina, and Tony McEnery. 2017. Collocations in corpus-based language learning research: Identifying, comparing, and interpreting the evidence. Language Learning 67: 155–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Robert C., and Wallace E. Lambert. 1972. Attitudes and Motivation in Second-Language Learning. Rowley: Newbury House. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Peter, Nikolas Coupland, and Angie Williams. 2003. Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity and Performance. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Bernadette M. Watson. 2013. The Social Meanings of Language, Dialect and Accent: International Perspectives on Speech Styles. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 1982. Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunston, Susan, and Geoff Thompson. 2006. System and corpus: Two traditions with a common ground. In System and Corpus: Exploring Connections. Edited by Geoff Thompson and Susan Hunston. London: Equinox, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworska, Sylvia, and Christiana Themistocleous. 2018. Public discourses on multilingualism in the UK: Triangulating a corpus study with a sociolinguistic attitude survey. Language in Society, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, Michael W. 2019. rtweet: Collecting and analyzing Twitter data. Journal of Open Source Software 4: 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, Ann. 2010. Who Is a Heritage Language Learner. Heritage Briefs. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics and Delta Systems, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Ruth. 2016. Montreal’s multilingual migrants: Social identities and language attitudes after the proposition of the Quebec Charter of Values. In Language, Identity and Migration: Voices from Transnational Speakers and Communities. Edited by Vera Regan, Chloe Diskin and Jennifer Martyn. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 217–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Ruth. 2019. Intergenerational language transmission in Quebec: Patterns and predictors in the light of provincial language planning. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, Ruth, and Sue Fox. 2019. Multicultural London English and its speakers: A corpus-informed discourse study of standard language ideology and social stereotypes. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, Ruth, and James Hawkey. Forthcoming. Mixed-methods approaches to the study of language attitudes. In Research Methods in Language Attitudes. Edited by Ruth Kircher and Lena Zipp. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kircher, Ruth, and Lena Zipp, eds. Forthcoming. An introduction to language attitudes research. In Research Methods in Language Attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kutlu, Ethan. 2020. Now You See Me, Now You Mishear Me: Raciolinguistic accounts of speech perception in different English varieties. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, Ethan, Mehrgol Tiv, Stefanie Wulff, and Debra Titone. Forthcoming. The Impact of Race on Speech Perception and Accentedness Judgments in Racially Diverse and Non-Diverse Groups. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Carmen. 2016. Multilingualism Online. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Mark Hugo, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, and Danielle Cuddington. 2013. Diverse Origins: The Nation’s 14 Largest Hispanic-Origin Groups. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Danny C., Javier Rojo, and Rubén A. González. 2019. Speaking Spanish in white public spaces: Implications for literacy classrooms. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 62: 451–54. [Google Scholar]

- Moyna, María Irene, and Verónica Loureiro-Rodríguez. 2017. La técnica de máscaras emparejadas para evaluar actitudes hacia formas de tratamiento en el español de Montevideo. Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana 15: 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Orpin, Debbie. 2005. Corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis: Examining the ideology of sleaze. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 10: 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2011. Reanalysis in adult heritage language: New evidence in support of attrition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 33: 305–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim, and Maria Carreira. 2010. Spanish in the USA. In Language Diversity in the USA. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Mills, Susana V. 2012. Spanish heritage language maintenance. In Spanish as a Heritage Language in the United States: The State of the Field. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 155–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Ellen Bouchard, Howard Giles, and Richard J. Sebastian. 1982. An integrative perspective for the study of attitudes toward language variation. In Attitudes towards Language Variation: Social and Applied Contexts. Edited by Ellen Bouchard Ryan and Howard Giles. London: Edward Arnold, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sallabank, Julia. 2013. Attitudes to Endangered Languages: Identities and Policies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkina-Lieber, Marina. 2020. A classification of receptive bilinguals: Why we need to distinguish them, and what they have in common. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 10: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilioti, Tereza, and Caroline Tagg. 2017. The ethics of online research methods in applied linguistics: Challenges, opportunities, and directions in ethical decision-making. Applied Linguistics Review 8: 163–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavans, Anat, and Maya Ashkenazi. 2020. Heritage language maintenance and management across three generations: The case of Spanish-speakers in Israel. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrain, Sarah. 2018. ‘Spanish at home, English at school’: How perceptions of bilingualism shape family language policies among Spanish-speaking parents of preschoolers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by Stephen Worchel and William G. Austin. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- The Associated Press. 2019. Florida Nurses: Clinic Warns Only Speak English or Be Fired. Latino Rebels. Available online: https://www.latinorebels.com/2019/08/20/floridanurses/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2019a. Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=hispanic&g=0400000US12&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B03001&hidePreview=false (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2019b. Language Spoken at Home, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estiamates. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=spanish&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S1601&hidePreview=false (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- United Nations (ND). n.d. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/theme/international-migration/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2001. Learning and Not Learning English: Latino Students in American Schools. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vessey, Rachelle. 2015. Corpus approaches to language ideology. Applied Linguistics 38: 277–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessey, Rachelle. 2016a. Language ideologies in social media: The case of Pastagate. Journal of Language and Politics 15: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessey, Rachelle. 2016b. Language and Canadian Media: Representations, Ideologies, Policies. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Vessey, Rachelle. 2021. Nationalist language ideologies in tweets about the 2019 Canadian general election. Discourse, Context & Media 39: 100447. [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa, Ikuko Patricia. 2010. Creaky voice: A new feminine voice quality for young urban-oriented upwardly mobile American women? American Speech 85: 315–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | While this definition only makes reference to attitudes toward entire varieties (i.e., languages, dialects, accents), there is in fact also a growing body of research toward particular linguistic features and phenomena, including attitudes toward quotatives (Buchstaller 2006), vocal fry (e.g., Yuasa 2010), phonetic variables (e.g., Díaz-Campos and Killam 2012), and forms of address (e.g., Moyna and Loureiro-Rodríguez 2017). However, this article focuses exclusively on attitudes toward the Spanish language. |

| 2 | They investigated representations of multilingualism as a metalinguistic construct in traditional media and then compared these with survey-based attitudinal data. |

| 3 | As these numbers indicate, there was an average of 29 words per tweet in the English corpus, compared to an average of 25 words per tweet in the Spanish corpus. There are several possible reasons for this difference, including the fact that Spanish is a pro-drop language (i.e., certain classes of pronouns can be omitted in contexts where they are grammatically and/or pragmatically inferable). It is also possible that the lower average word count per tweet in the Spanish corpus is a result of the fact that many Spanish tweets included links, as we will discuss below. Links count as one word but take up many character spaces. In any case, it is very unlikely that the different averages of words per tweet affected our overall findings. |

| 4 | Another common procedure is the investigation of keywords—that is, words which are unusually frequent when one’s own corpus is compared to a larger reference corpus (see, e.g., Vessey 2016b). However, for reasons of space, this procedure is not discussed here. |

| 5 | This means that we investigated not only the infinitive “hablar” (“to speak”) itself but also all conjugated forms of this verb. |

| 6 | Evidently, we cannot know whether the tweeter and their mother were actually in Florida at the time of this occurrence. In fact, the tendency for Latinx parents to use English with their children is not an uncommon one in the US (see, e.g., Martinez et al. 2019). Nevertheless, given that there is much evidence of language-based discrimination of Florida’s Spanish-speaking population (see, e.g., The Associated Press 2019), we consider this tweeter’s recollection of their mother’s behaviour meaningful in the present context. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).