Abstract

Within sociolinguistic research on small languages like Low German, differentiation into new and native speakers has become established. The relationship between the two different groups of speakers is sometimes conceptualized as an insurmountable “gap”. In addition to different acquisition paths and competencies, identity discourses of belonging, authority and authenticity, as well as typical practices, are all crucial elements of these differences. Despite these differences, the intergenerational language-centered analog community of practice (CofP) “Plattdüütschkring” consisting of approximately 10 new and native speakers of the regional language Low German has existed since 2005. This article is based on an explorative case-study analyzing the network “Plattdüütschkring” as an example of successful cooperation between new speakers and native speakers on the basis of typical attitudes and linguistic practices. In order to gain authentic, subjectively experienced insights into identities, normative conceptions and individual language experiences within and outside the network, meta-linguistic reflections of the members themselves were analyzed. These meta-linguistic reflections were collected through narrative interviews with the same and different members at the two survey dates 2010/11 and 2020. The findings show norms of monolingual language use, narrative identities of a normative hierarchy of acquisition scenarios and competences as aspects of belonging. Social and learning-oriented and thus multiple individually appropriate functions of the network can explain the motivation for long-term membership. These outcomes help to understand the role of language attitudes in CofP in the language development of small languages as well as abstract characteristics of successful language-centered networks.

1. Introduction: The Sociolinguistic Context of Low German and the Theoretical Foundation of Language Attitudes, Low German, “New Speakers” and Communities of Practice

1.1. Sociolinguistic Context: The Vulnerable Regional Language Low German in Germany and Specific Networks

In order to establish the relevance of networks for the language maintenance of small languages by way of introduction, this chapter first outlines the sociolinguistic context of Low German (Section 1.1), the theoretical basis of central concepts (Section 1.2) and derives the research objectives from this (Section 1.3).

This paper focuses on language settings in connection with Low German. This is a West Germanic variant related to Standard German, English and Frisian. On the one hand, it has many similarities with High German due to language kinship and a constant language contact situation; on the other hand, there are differences at all linguistic-systematic levels (Stellmacher 2017; Thies 2007). The historical variant of Middle Low German was spread throughout the entire North Sea and Baltic region from the 13th to 16th centuries as the lingua franca of the Hanseatic merchants’ guild. After a loss of prestige and a corresponding decline in use from the 17th century onwards (Gabrielson 1983), Low German today represents a dialect with a high degree of internal differentiation (Stellmacher 2017; Spiekermann et al. 2016; Arendt et al. 2017). The language area in Germany comprises the northern federal states of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Schleswig-Holstein, Lower Saxony, Bremen, Hamburg and, to some extent, Brandenburg and Saxony-Anhalt. The number of competent speakers is comparatively low. According to current surveys, only 15% can speak Low German well or very well, 48% understand it well or very well (Möller 2008; Adler et al. 2016). A comparison with a 1984 survey shows a drastic decline in competence: about 30 years ago, 35% could still speak Low German well or very well (Stellmacher 1987). Correspondingly, Low German is considered vulnerable according to the UNESCO Red Book (Red Book 2020) and has been recognized by the European Language Charter (European Language Charter 1992) as a regional language since 1999 (INS 2008; Arendt 2014a, 2020). In order to preserve the language, Low German is now anchored in various forms in schools in the northern federal states with the aim of teaching the language. The current pupils, and in part also the teachers, are the third or even fourth generation, who—if at all—have only heard Low German from their grandparents or great grandparents. The 2nd and 3rd generation usually has some passive knowledge, but the language is barely used actively (Arendt 2017, p. 301). Basically, the family is no longer the place of language transmission and maintenance. Rather, speakers see extra-familial institutions, which include schools, kindergartens and cultural institutions, as the place to protect the language (Adler et al. 2016, p. 35).

In addition to the top-down measures in the state education sector, there are numerous mostly semi-public civic associations that dedicate themselves to language preservation primarily from a bottom-up perspective. For example, in its Atlas Niederdeutsch (2020), the Heimatverband Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2020 listed 38 corresponding associations in an initial exploratory survey and showed that they are distributed throughout the federal state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. So far, these associations of speakers have not been the focus of investigations into language preservation. The assumption is that this represents unjustified neglect of relevant social language actors in specific network-structured CofP. The usefulness of such civic community-based initiatives is also emphasized by Bermingham and Higham (2018, p. 404). This is why this case study will focus on the “Plattdüütschkring” network as an example.

1.2. Theoretical Foundation of Language Attitudes, Small Languages, Identity of “New Speakers” and Communities of Practice

How do you preserve an endangered language? This is one of the central questions of sociolinguistic research on minority languages. Language attitudes, the identities of speakers and places of use play an important role. For this reason, these three aspects are the focus of this paper.

As subjective linguistic data, language attitudes are the subject of dialectological and especially sociolinguistic research. Depending on the perspective, further aspects of the iridescent term become relevant for the definition. The present contribution follows a context-sensitive approach inspired by social psychology and interaction analysis from perceptual dialectology (Anders et al. 2010; Preston 2011; Cramer and Montgomery 2016) and folk linguistics (Preston 2019; Antos 1996) and defines language attitudes as “individually different, socially conditioned, collectively anchored meta-linguistic evaluation structures that are acquired in language socialization and manifested, handed down and modified in interactions”. Evaluation objects are languages, language use and/or groups of speakers”. (Arendt 2019a, p. 336; Eichinger et al. 2012). Based on the traditional socio-psychological conceptualization of attitudes, encompassing the three components cognitive, conative and emotional (Wänke and Bohner 2006), a tripolar model of language attitudes was established in sociolinguistic research: The three constitutive poles of language attitudes are first, explicit meta-linguistic evaluations in the expression of language attitudes, second, language use practices and third, (mostly experimentally determined) reactions to perceived variants (Arendt 2011; Niedzielski and Preston 2003).

Numerous studies usually refer to only one aspect of language attitudes, such as meta-linguistic reflections (Hornsby and Vigers 2018; Puigdevall et al. 2018; Davies 2010), and thus obtain a very profound picture for this one area. However, these approaches can only partially capture the complexity of language settings. To go beyond this one-sided orientation, the present contribution examines typical language use practices and meta-linguistic reflections on linguistic identities, norms and at least two poles of triadic conditionality and relates them reflexively to each other. It is assumed that by combining language use on one hand, and meta-linguistic reflections, on the other hand, a correspondingly complex picture of language attitudes can be reconstructed. Thus, the social registration of variants (Johnstone 2016) can be viewed from two perspectives, and the results can be placed in the context of the New Native Speaker dichotomy.

Low German thus shows typical characteristics of so-called small languages (Pietikäinen et al. 2016), contested languages (Tamburelli and Tosco 2021), minority languages (Hogan-Brun and O’Rourke 2019; Arendt 2020) and their revitalization (Fishman 1991). This paper follows a dynamic approach to the constitution of small or contested languages, focusing on speakers as social actors, their language practices and the communities they create. The numerous linguistic changes, such as marginalization, suppression and loss of communicative domains, have a serious impact on the identities of the members of the linguistic communities.

In sociolinguistic research, identity is seen on a social constructivist basis as a dynamic and context-sensitive product of linguistic, social practices (Buchholz 1999; Buchholz and Hall 2005). This means that, contrary to a unitary essentialist model, there is not one true stable identity of a person, but that different partial identities of a person can be activated depending on the context (Döring 2003, p. 329). Language plays a central role here: Firstly, different linguistic practices (language use) in the form of different styles can indicate different identities. Processes of enregisterment describe how speech styles acquire different social meanings (Coupland 2013, p. 292; Johnstone 2016). The connection between regional identity and dialectal speech has been repeatedly demonstrated (Ehlers 2018). Secondly, metalinguistic expressions of self-attribution and attribution to others form building blocks of both identity representation and language attitudes. Language attitude expressions as identity displays have been investigated in various studies with regard to Low German (Arendt 2010; Scharioth 2015). For smaller languages, a speaker group with special identity features has been constituted: The non-family, institutionally controlled teaching of small languages in different educational institutions leads to a change in typical speaker biographies, resulting in the emergence of so-called “new speakers” (Jaffe 2015; McCarty 2018; O’Rourke 2018; Hornsby and Vigers 2018; Fhlannchadha and Hickey 2018) as an innovative group of language actors and a crucial issue in current research in the field of small languages. “New speakers” (Hornsby 2015; Jaffe 2015) are children or adults who acquire “a socially and communicatively consequential level of competence and practice” (Jaffe 2015, p. 25). In addition, numerous studies have traced partially precarious identity constructions as a specific feature of this group (Dunmore 2016; Puigdevall et al. 2018), which can be summarized as “deviant identities”. This positioning is, in turn, the result of specific communicative experiences, such as the non-acceptance of their use of language by so-called native speakers (Hornsby 2015), numerous corrections (Arendt 2012) and an ambivalent relationship to belonging, authorities and authenticities (O’Rourke 2015; Bermingham and Higham 2018; Fhlannchadha and Hickey 2018). Hornsby (2015) metaphorically described the difference between new and “traditional” speakers as a “gap” that “can hinder language revitalization projects” (Hornsby 2015, p. 107). At the same time, he pleads for a holistic, inclusive approach that takes both groups of speakers into account in future research (Hornsby 2015, p. 120) and makes the mutual border-drawing practices themselves the subject of discussion. Following this approach, the present contribution also focuses on “new speakers” and “traditional speakers” in their relationship to each other.

As mentioned above, the starting point of this case study is an intergenerational network called “Plattdüütschkring”, where members meet regularly to address the exclusion of their variety. They thus simultaneously constitute a language-centered community as an analog network with high density and multiple possible functions for the group members. Thus, this study follows both a theory of communities of practice (CofP) (Eckert and McConell-Ginet 1999; Buchholz 1999; Gee 2005; Dodsworth 2013) and sociolinguistic approaches that place speakers and their practices at the center of research rather than the language itself (Gal 2006, p. 13; Hornsby 2015). CofP are not only characterized by a special group-constitutive language use (Buchholz 1999; Mendoza-Denton 2008), in which linguistic practices index ingroup and outgroup belongings. The members also share common values and norms (Dodsworth 2013). This means that typical speech styles can acquire specific social meanings within the CofP, as can the articulation of collectively shared attitudes. Research on language-centered CofP forms an important part of speech community studies (Dodsworth 2013, p. 270). As a typical procedure of new studies, variable analyses are combined with ethnographic observations or narrative interviews (Buchholz 1999; Mendoza-Denton 2008; Locher and Bolander 2017, p. 409). Only in this way is it possible to reconstruct the social-symbolic meaning of linguistic practices from the participants’ perspective.

1.3. Research Objectives

Starting from a complex, tripolar concept of language attitudes, the contribution focuses on both linguistic practices and meta-linguistic reflections. The focus is on speakers of the small-language Plattdeutsch as social actors. In addition to new speakers, so-called “native” or “traditional speakers” (Hornsby 2015) are also considered in order to counteract a one-sided concentration on the former in an inclusive perspective. The sociolinguistically relevant research topic of “speech communities” is examined in the following article, using the language-centered network “Plattdüütschkring” as an example and subjecting it to an in-depth analysis. The members of this network are located in the area of tension between traditional speakers on one hand and new speakers on the other. By analyzing their language practices, their positions in terms of linguistic norms, belonging and authority, as well as their functional attribution of the network, the claim to bridge the gap between new and native speakers is fulfilled. Furthermore, insights into the complex structure and multifunctionality of networks will be provided. On this basis, their possible contribution to language maintenance can be discussed. The central question of the article can be formulated as follows: What significance do certain CofP have in relation to the goals of language revitalization? Can theses on the promotion of language use be derived from the results? Can such networks be seen as possible places for language revitalization, analogous to families? (Section 5)

In order to achieve these goals and answer the central question, the paper focuses on answering the following three sub-questions:

- (1)

- Sub-questions on language use: How can the typical language use of the CofP be characterized? That is, what linguistic practices are constitutive for the network? Do the network members also apply their meta-linguistic appreciation in typical linguistic practices?—In other words, can the network members contribute to language maintenance through typical linguistic practices? (Section 3.1)

- (2)

- Sub-questions on identities: Which aspects of identity are made relevant by members in relation to belonging as a positioning activity? What role does differentiation between new and traditional speakers play?—Does membership in the network thus form relevant identity components conducive to language maintenance? (Section 3.2)

- (3)

- Sub-questions on motives for participation: What are the motives for participating in the network? What functions and characteristics are associated with the network?—What characterizes a successful, temporally stable network that can support language maintenance in the long term? (Section 3.3)

This case study aims to expand the current state of sociolinguistic research in three ways. The paper aims to provide (1) further insights into language maintenance, (2) further methodological insights, and (3) an expansion of the typical group of varieties analyzed, as follows:

- (1)

- further insights into language maintenance: Specific language-centered CofP focus on previously neglected but potentially relevant actors in language maintenance. By focusing on the network as a specific context and the corresponding positioning practices of its members, this contribution also follows the currently relevant lines of research on “new speakerhood”, which McCarty (2018, p. 471f.) summarizes by stating that “context matters” [and] “[p]ositionality matters”.

- (2)

- further methodological insights: On one hand, social groups, their language use and their attitudes are original objects of sociolinguistic research (Holmes and Hazen 2013), which—as shown above—have at times been considered with a very restrictive focus. The combination of language use and attitudinal analyses expands the hitherto partially one-sided focus on language use or language attitudes or identities. This study, in combining the objects of investigation, can thus help to provide holistic sociolinguistic insights into small speech communities and also constitutes an expansion of previous research in methodological terms.

- (3)

- expansion of the typical group of varieties analyzed: Low German has not yet been the focus of international research. This article will show that the situation has many similarities to other small languages, which further substantiates the relevant research results. At the same time, contextual differences may emerge that can plausibly support further contrastive analyses.

2. Materials and Methods

This case study follows a qualitative research approach, which investigates comparatively open research questions on comparatively few research units in great detail using semi-structured data collection methods. The data are analyzed interpretatively with typical hermeneutic methods of the qualitative paradigm (Section 2.2). The aim is an explorative description of the research object and the derivation of theoretical assumptions (Döring and Bortz 2016, pp. 184–93).

2.1. Participants and Procedure

At the center of the article is the language-centered network “Plattdüütschkring” (Plattdeutschkreis). The 5–10 members, currently aged 30–80, meet every 14 days—in times before COVID-19—for about 1 1/2 h in a private flat. The network has now been in existence for 15 years. It was originally founded in the academic sphere to protest against university cutbacks regarding Low German. The first members were, therefore, academics interested in learning and speaking Low German. Gradually, the membership structure changed: on one hand, more new members joined through a newspaper advertisement and personal contacts. On the other hand, the student members mostly left the network again after finishing their studies. However, there were never more than a maximum of 10 members. More would not have been possible at the private meetings. Some members like N-VN have been involved almost from the beginning. Nevertheless, the comparatively homogeneous structure has changed in recent years, as has the objective. The current motives and objectives of the participants have not yet been researched and are therefore the subject of the following analyses (see Section 3.3). Due to the language-related, functional objectives, the internal network relationship of the participants can basically be characterized as formal according to the socio-psychological theory of social relationships (Döring 2003, p. 405). Based on the common goal orientation, the network can be more accurately described as a typical community of practice (CofP) (Buchholz 1999; Dodsworth 2013).

The data of the present study consists of two parts addressing the two different aspects of language attitudes outlined above—linguistic practices on one hand and meta-linguistic reflections on the other. Written data and participant observations serve as variable-analytical and ethnographically oriented reconstructions of typical language use practices. On this basis, the dialect depth in terms of dialectal standard divergences of the speakers can be compared and related to their self-statements. Meta-linguistic reflections of identity, belonging, and motives for participation were collected in qualitative, narrative interviews. The triangulation of medially and structurally different data will enable a multiperspective holistic view of the network members, their practices and their subjective interpretations.

The selection of participants for this study (Table 1) is based on a “judgment sampling” (Hoffman 2013, p. 31), which is most common for sociolinguistic and narrative interviews. This means that participants were deliberately selected to meet the predetermined criteria of the study. In this case, the three criteria were: first, they had to be members of the network; for the variable analyses, they had to have regularly participated in email communication; and third, they had to be classifiable as new or traditional speakers. The difference criteria needed to be as evenly distributed as possible: of the nine participants, five are male, four female, four traditional and five new speakers; three are aged over 65, three (or four) between 30 and 65 and three (or two) under 30.

Table 1.

Participants of this case-study.

The codes result from a systematic change of the initials of the participants and a classification as T for traditional speakers and N for a new speaker. The classification of the participants into one of the two categories as traditional or new speakers, as suggested by a reviewer, is somewhat difficult (Jaffe 2015). In principle, the classification should be based on self-categorization, i.e., from the participant’s perspective. This is problematic because, first, it was not possible to interview everyone, and second, the interviewees either did not position themselves at all or did so ambivalently. For the classification, I, therefore, used the language used in the interview and the described language biography as further criteria. In doing so, I followed the criteria of the new speakers from Section 1. The traditional speakers are T-LÜ, T-SD and T-TK according to the self-assessment, T-FN according to third-party positioning. In the interview, T-SD positions herself as a competent speaker with Low German in family conversation but vehemently negates having grown up with Low German. N-VN emphasizes in the interview that she taught herself Low German but is constantly improving her skills. N-GÖ is described by the other members as a “learner” who uses the network to improve his competence. The same applies to N-SH. The classification of N-JG and N-BF was based solely on ambivalent self-positioning.

The author has taken part in more than 50 meetings in the last 15 years, as is common in CoP-studies, in order to understand the meaning of the interactions, shared norms and social symbols adequately (Dodsworth 2013, p. 272; Buchholz 1999). This way, I got to know the members better and can make statements about the strength of the network ties. In the present network, most members are known to each other only through the network and only interact with each other there. They neither share a common circle of friends nor a common neighborhood, nor are they workmates. One would therefore speak of predominantly weak ties among the network members (Dodsworth 2013, p. 267). The exception is a father-son constellation (T-LÜ and N-BF). In terms of social science network theories, this is thus a formal network with primarily weak ties (Döring 2003, p. 407). Only the analyses will reveal whether this assessment is also true from the participants’ perspective.

The email corpus of the network has been systematically collected since 03/2011 and currently comprises 667 emails (state as of 11/2020) with about 25 words each. The total volume amounts to about 16,675 words. Of this total corpus, a partial corpus of emails of T-FN, T-LÜ, N-VN, T-SD, N-GÖ and N-SH were formed for the analysis of language use, reflecting as even a distribution as possible according to age, gender and language biographical experience (in the sense of new and native speakers). Of the six members, one email from each year since membership has been integrated into the corpus of analysis so that data from 2011–2020 are available. This corpus consists of 1403 words in 39 emails.

In order to reconstruct language attitudes and identities, eight qualitative interviews were conducted. In doing so, this study follows a qualitative paradigm (Flick et al. 2015; Döring and Bortz 2016; Mey and Mruck 2020), adopting a more sociological and anthropological approach (Holmes and Hazen 2013, p. 1). The data collection was based on the following considerations: Qualitative, semi-structured interviews focus on the subjective experience of the participants and thus, they make events and behaviors which cannot directly be observed accessible (Döring and Bortz 2016, p. 356). It makes it possible to reconstruct individual value and sense systems from the participant’s perspective. This is particularly relevant for CofP, which is partially constituted by specific internal norms and values (Section 1.2). Qualitative interviews (Froschauer and Lueger 2020) have been successfully used many times in sociolinguistic research on new speakers and have proven to be a valid data collection tool to describe attitudes and identities (Fhlannchadha and Hickey 2018; Dunmore 2018; Selleck 2018; Smith-Christmas 2018; Bermingham and Higham 2018; Hornsby and Vigers 2018). They have also been used in the context of Low German (Arendt 2010; Schröder and Jürgens 2017). The members were asked in a casual atmosphere about their motives for membership, their experiences and their relationship to the Low German language by means of narrative interviews. The aim was to derive information about communicated network-related identities and roles in terms of belonging and authority (Section 3.2) as well as motivations for language use and membership (Section 3.3). The corpus of narrative interviews is in two parts as there was an interval of 10 years between the interviews. Except for two cases, different members took part on the second occasion (see Table A1 in Appendix A). In a contrasting perspective, this also allows statements to be made about the processes of change from semi to new to native speakers (Jaffe 2015, p. 26). In this way, the functionality of the network for language preservation processes can be captured. In the first round of data collection in 2010/11, four young, mostly new speakers (N-BF, N-JG, T-TK, N-SH) were surveyed, each with a duration of about 30–60 min. A total of 158 min of data are available. In the second round of the 2020 survey, four currently active members (T-LÜ, N-BF, N-VN, T-SD) were surveyed for 45–90 min. A total of 231 min of data is available. The interviews were transcribed according to the GAT conventions (Couper-Kuhlen and Barth-Weingarten 2011).

2.2. Data Analysis

The first sub-question about the typical language use of the network (Section 1.3) was differentiated and operationalized into the following three sub-questions for the variable analysis of written email communication:

- Which dialectality quotient is shown in the emails and thus in the written email correspondence of the network members? Is the high esteem for the language also reflected in the direct interaction?

- Which variants show the highest density, and to what extent does this finding correspond with language typological characteristics and evaluations in the meta-linguistic reflections?—Do the members use a specific or typical form of the variety?

- Are the differences between new and native language use reflected in such a way that the density of variants in the native language is noticeably higher? Are two distinct varieties constituted here, as partially reconstructed in the research literature (see Hornsby 2015)?

In order to answer these questions, the emails were subjected to a detailed analysis of typical Low German linguistic variables (Section 3.1.2) using the qualitative-quantitative analysis software MAXQDA (Ehlers 2018, p. 100). For this purpose, the dialectal standard divergences were categorically recorded on the three linguistic levels of phonology, morphology and lexis. The number of deviations in total and per level was divided by the number of words to determine the dialectality quotients (Table A2 in Appendix A). The calculation is based on the model of the German Language Atlas (Herrgen et al. 2001; Schmidt and Herrgen 2011), as this has been successfully used in numerous dialectological studies on Low German (SiN 2010; Elmentaler 2011; Scharioth 2015; Ehlers 2018). The present adaptation, however, does not require any differentiated weightings since the available medially written data do not distinguish between dialectal and medially oral standard deviations. The results were then related to the self- and other-positioning as new or native speakers. A tertium comaparationis identical analysis of variables was carried out on a current literary Low German text. This makes it possible to make statements about the dialect depth of the emails in comparison to other Low German-language texts and to interpret them in relation to this.

The data of the interview corpus will be analyzed following an interpretative approach that is oriented towards discourse (Spitzmüller and Warnke 2011; Baxter 2018) and conversation analysis (Sidnell and Stivers 2013). While discourse analysis focuses on the content of what is said in the form of arguments and topics, conversation analysis concentrates on sequential aspects (Stivers 2013; Benwell and Stokoe 2020) of the joint production of interactive events by the participant and interviewer (Arendt 2014b). The combination of the two perspectives has already been tested and has proven to be appropriate in various surveys of language attitudes (Arendt 2010; Scharioth 2015). The identity constructions in the interviews are operationalized as “social positioning of self and other” (Buchholz and Hall 2005, p. 586), which captures identities as narrative (re)constructions in terms of positioning (Lucius-Hoene and Deppermann 2004; Benwell and Stokoe 2020). Indicators for self-positioning, on one hand, were phrases with pronouns in the first person singular or plural, and for external positioning, on the other hand, pronouns in the 3rd person singular and plural in the subject and object position. Transcript excerpts and their interpretations serve to verify the plausibility of the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Practices of Network Communication

The following Section 3.1 focuses on language use aspects of the network and examines constitutive network practices in relation to the high value of language, language-typical characteristics of network communication and thus unfolding language functions, and differences between new and native speakers constituted in language use.

3.1.1. Interactive Practices and Topics in Meetings

The following paragraphs are based on participating observations as well as on experiences described in the narrative interviews. Communication during the meetings is primarily in Low German, first, on topics of everyday life, second, on socially and politically relevant topics and third, on literary texts. In some cases, interactive meta-linguistic sequences occur in the second subject area when gaps in naming need to be identified and addressed. This also involves the creative expansion of vocabulary (Arendt 2012), which can already be seen in the Low German name of the network “Plattdüütschkring”, a neologistic composite of language and an archaic form for “association”. Low German is deliberately used multifunctionally in the oral ad-hoc network communication, first, as an everyday and near language, second, as an extension language and third, as a literary language. Through this multifaceted use of language, various communicative practices in the regional language are in simultaneous use, which can contribute equally to the development of competence and the expansion of the corpus—at least with regard to concrete group communication. At the same time, the members use typical educational practices such as homework or small puzzles, which serve to expand and test knowledge.

The following three insights seem particularly relevant: First, the diversity of practices and themes simultaneously demonstrates the multifunctionality of the network itself, in that it serves as a place of everyday use, for the discussion of relevant social issues and for the examination of cultural, literary works in equal measure. The members thus constitute family, friendly and educational contexts in equal measure. Second, in their ingroup communication, the members reverse the conditions of linguistic reality with a barely perceptible use of Low German and use this variety as a group-constitutive tool of ingroup communication. Third, use shows a direct correlation to the value of the language, which contrasts the usual speaking about Low German with a conscious speaking in Low German. In doing so, they simultaneously pursue a hierarchization of their varieties and form “identities of resistance” (O’Rourke 2018).

3.1.2. Language Use in Written E-mail Communication

The emails appear functionally and formally homogeneous at first glance. Thematically they revolve around the organization of the meetings and—analogous to the communication at the meetings—are almost exclusively written in Low German. As a rule, network members must therefore already have competence in the production of written media in order to participate in the email communication.

| Example 1: Email corpus, T-LÜ cancels a meeting (01/2020). |

| Leewe Plattschnacker ... nee, Kinnings, dat ward ok hüt Abend nix mit mi. Mal kieken, wurans dat bi’t nächste Mal utseihn ward. Ick ward worschienlich öwer versöken, an’n Sünnabend to den’n Runden Disch na (…) to kamen. Denn seihn wi uns viellicht. Hartliche Gröten T-LÜ |

| Dear speakers of Low German ... No, kids, it’s not going to work out for me tonight either. Let’s see how it will look next time. But I will probably try to come to the “round table” in (…) on Saturday. Maybe we’ll see each other then. Best regards T-LÜ |

| Example 2: E-mail-corpus, N-VN, ratifies a meeting (09/2014). |

| Mine Leiven, an mi sall dat nich liggen(?). Kommt ma tosamen bi mi. Grötings N-VN |

| My dears, it shall not be my fault(?). Come together at my place. Greetings N-VN |

Examples 1 and 2 illustrate the two central characteristics of the emails: thematic focus on the organization of meetings and their relative brevity. On average, the emails consisted of 25 words.

There are some passages in High German in the overall corpus, but all emails from the partial corpus of the six members are in recognizable Low German. The relatively high density of variants is still striking. In 1403 words, 1313 variants (tokens) were coded. In a cursory lexical analysis of the invitation emails in Arendt (2012), numerous hybrid, inter-dialectal forms (Britain and Trudgill 2000) from other Low German dialectal areas as well as neologisms, some of which were ratified and further used by the members, stood out. The following analysis focuses on the emails of the members and includes all levels of language systems (except syntactic).

The most frequent standard deviations with 1221 tokens were on the phonological level (vocal: 617; consonantal: 604), which was nevertheless reconstructed solely on the basis of the graphical realization. The second most frequent were variances on the morphological level with 72 tokens (nominal: 54; verbal: 18). Lexical differences were found only 20 times. The fact that the findings revealed a phonological dominance is in line with typical dialectological findings on dialects of German and other small languages (Hornsby 2015) and specific features of the Low German language, including the missing second sound shift and New High German diphthongization.

It is interesting to note that the dialectality quotient in all emails is relatively similar (see Table A2 in Appendix A). Although they do not reach the value of the literary language tertium comparationis, the differences shown are small. A clearly discernible difference between new speakers, such as N-VN, N-GÖ and N-SH, and traditional speakers, such as T-FN, T-LÜ and T-SD, is hardly noticeable. The differences between the dialect quotients (DQ) at the phonological and overall level are only about 0.2. Only T-LÜ reaches even higher values. This similarity may be due to the fact that the members-only participate in written communication if they possess a level of competence considered sufficient. According to statements in narrative interviews, such as N-VN, they also write their emails using relatively standardized dictionaries. Moreover, we can also explain the similarities as the result of processes of micro- and even mesosynchronization (Schmidt and Herrgen 2011, pp. 29–32), where members have simply learned from each other through imitation. In this sense, they reuse typical forms and phrases from other members and/or from the emails they are replying to. This is possible not least because of the lack of thematic variation in the emails: mostly it is about invitations, attendance confirmations or cancellations of meetings (see Examples 1 and 2). The following collectively used linguistic variants (including the number of tokens) are intended to illustrate the similarities in language use.

- Morphology:

- ∘

- Diminutive of nouns with ~ing in Grötings; used by: T-FN (3); T-LÜ (1×); N-VN (2×); N-SH (5×); T-SD uses tschüssing (4×) instead.

- Phonology:

- ∘

- Vowel rounding [i-y] in bün; used by T-FN (3×); T-LÜ (1x); T-SD (2×); N-SH (5×).

- ∘

- Undisplaced plosive [k] instead of fricative [ç] in ik: T-SD (4× ick); T-LÜ (13× ick); T-FN (12×); N-SH (25×); N-VN (12×).

- Lexicon:

- ∘

- No specific lexical forms could be identified in the current analysis. Neologisms such as Brägenschööt for “memory” only appear in the invitation emails, but not in reply emails (Arendt 2012). There, however, they do get passed on since a similar text is always written.

The phonological and morphological variants are typical regional forms of use (Ehlers 2018), which are by no means network-specific. Nevertheless, as variants that are collectively repeatedly used, they characterize internal network communication and can thus have a group-constitutive effect (Dodsworth 2013, p. 269). The CofP thus trades and validates regionally typical forms and thus registers them as appropriate forms of the intended Low German language community, which indicate belonging (Coupland 2013; Johnstone 2016).

While the description of language use is still comparatively simple, statements about acquisition within or outside the CofP are much more presuppositional. In order to be able to confirm the plausibility of network communication as a possible place of acquisition, more in-depth, longitudinally oriented analyses would be necessary, as is common in research on child language acquisition (Arendt 2019b). While it is not generally possible to say with certainty which of these explanations applies, individual differences are certainly present.

3.1.3. Preliminary Summary: Hierarchical Occupation of a Variety through Varied Use and Diversity of Topics and Practices

The sub-questions outlined above (Section 1.3 and Section 2) can now be answered in terms of use as follows: internal network communication is medially realized in Low German both orally in the meetings and in writing in an email. The network members reverse the public marginalization of their variety by means of the exclusive use of Low German language to create a hierarchy of their variety and occupy and socially register it for their ingroup communication. The appreciation of the Low German language realized in the interviews and in membership is thus directly reflected in a dominant monolingual usage. The attitude finds its echo in use, instantiating a monolingual norm. Based on the topics dealt with, Low German is used in the practices as a multifunctional variety whose radius extends beyond everyday communication to society and politics. In this way, the members break with the traditional views of Low German as a purely near-language variety and thus expand restrictive boundaries in their activities.

The variable-analytical description of the emails opened up a view of creative-hybrid structures on the lexical level and dominance of the phonological/graphical level with regard to the dialectality quotient. The chosen phonological/graphical and morphological variants are typical for the language area of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and indicate the relatively high competence of the network members. Furthermore, a noteworthy finding of the analyses is that there is a consistently high density of variants and hardly any differences between new and traditional speakers. The difference between the two is therefore not clearly visible within the written language use in the emails.

3.2. Narrated Identities of Belonging, Competences and Experiences

Section 3.2 focuses on the identity aspect of the network members and examines which characteristics are set as relevant by the members in relation to belonging as a positioning activity. It is examined whether and how a possible differentiation into new &/vs. Native speakers are made, and on what basis this is done. These findings will be related to the results of the usage analyses. The following findings are based on both interview corpora (2011 and 2020). The central characteristic that determines who belongs to the “de plattdüütschen” speaking community is the self-certified language competence. This applies here, as well as in other membership negotiations (see, e.g., Jaffe 2015). This is not surprising since it is a matter of belonging to a language community. What is striking, however, is how different the self-positionings are and how ambivalent their relationship is to the demonstrated competence in situ, i.e., in the interview itself, or to the findings from the email corpus (see Section 3.1 and Figure 1).

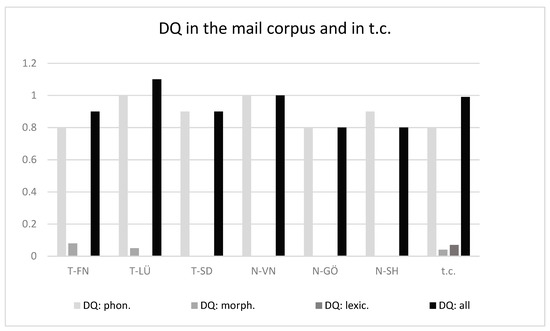

Figure 1.

Dialect quotients (DQ) in the email corpus and in t.c. (including language-structural differences).

Whereas the previous study (Arendt 2012) onward new speakers showed a relative homogeneity of language attitudes, in this study, encompassing both new and traditional speakers, there are additional, different aspects which are relevant. From a methodological point of view, these differences make it clear that a view focused solely on new speakers always allows for a selective perspective. However, if both groups meet as interaction partners—as in the present network Plattdüütschkring—or the pupils in the families, language attitudes and concepts that are to be recorded as equally valid in research may collide here (see Hornsby 2015).

The following differentiation into (1) traditional, (2) new and (3) ideal speaker is based on self- and third-party attributions of the network members in the interviews. However, the statements do not merely reflect the opinions of the interviewees but were obtained in an interactive exchange with the interviewer, i.e., through topic-controlling questions (Arendt 2014b). For this reason, the following transcript sections integrate the question as far as it seems necessary for understanding.

3.2.1. Traditional, Native Speakers: Mother Tongue Speakers from Childhood On

In the corpus, we only have one reference in which the interviewee presents himself as a native speaker. All the others more or less explicitly negate the attribution, such as T-SD, who, for example, rejects family language experiences during the many years of marriage. Three aspects of this are particularly relevant. First, “native speaker” seems to be a protected term that may only be used by those who have acquired language competence in the family during childhood, those who have “grown-up” with it (Jaffe 2015, p. 25). Second, the term seems to function similarly to a magic word in such a way that belonging no longer must be proven by language use but is proclaimed solely by the corresponding self-positioning. Third, this leads to a hierarchization of acquisition paths that hypostasizes family transmission (Hornsby 2015, pp. 108–9). At the same time, criteria are mentioned with which the new speakers usually position themselves as other: not from childhood; not in a family; not competent.

In his statements in Low German throughout the interview and in Example 3, T-LÜ clearly positions himself as a native speaker.

| Example 3: Transcript corpus 2020: T-LÜ describes his mother tongue competence. | ||

| 96 | T-LÜ: | bün also tau seggen ein <<gedehnt>muttersprachler.> |

| 97 | dat HEIT ik bün as kind (.) plattdüütsch UPwussen. | |

| 98 | I: | hm-hm. |

| 99 | T-LÜ: | KENN dat nich anners von öllern von (.) |

| 100 | geschwister von de naverslüüd | |

| 101 | von (.) von (alle(n)). (-) | |

| 102 | ik harr allerdings GLÜCK; | |

| 103 | I: | dat MEINT? |

| 104 | T-LÜ: | as ik to SCHAUL keem künn ik ok all HOCHdüütsch. |

| 96 | T-LÜ | so I can say a <<stretched>native speaker.> |

| 97 | I: | that is, I grew up in Low German as a child |

| 98 | mhm. | |

| 99 | T-LÜ: | don’t know it any differently from my parents |

| 100 | siblings brothers and sisters neighbours | |

| 101 | from (.) from (all). (-) | |

| 102 | I was lucky though | |

| 103 | I: | that means? |

| 104 | T-LÜ: | when I came to school, I already knew standard german |

The categorization as native is especially emphasized by realizing it in High German and stretched. The phrase “so tau seggen” (to put it this way) prepares the utterance as deviating from the rest of the utterance context and at the same time acts as a distancing from the term. Nevertheless, he takes it up four more times without these distancing framings. In the above example, in l. 96 till 99, he describes his entire childhood as exclusively in Low German. In doing so, he follows the usual descriptions of older speakers (Arendt 2010). Quite explicitly, he claims his belonging to the Low German language community with reference to his acquisition biography and—rather implicitly—by using the variety throughout the interview.

3.2.2. “New Speakers” and “Cheeky” Low Germans

What characterizes the “other” network members? Unlike the “native speaker”, “Plattdüütschen”, the other network members lack a clear nominal term for self-designation (see also Jaffe 2015, p. 21f. for new speakers of Corsican). They do not refer to themselves by attributing themselves to an established category and/or consciously reinterpreting it for themselves. Rather, they paraphrase or simply describe themselves and their age, competence and acquisition biography. This means that they obviously lack a constitutive, distinct term that they can use as an appropriate, meta-linguistic building block for their self-positioning.

The 2011 data collection focused exclusively on members who implicitly positioned themselves as new speakers or learners. The three central language experiences and ideologies positioned there can be summarized as follows:

- 1.

- Environment hostile to speech

The members experience their own use of Low German as problematic in two ways. They thus “outen sich/come out” as “merkwürdig, schrullig/strange, quirky” (N-SH) in a language environment dominated by High German, and as “not belonging” in the Low German-speaking community if their language use is meta-linguistically corrected (N-BF) or not ratified in object language (N-SH, N-BF, N-JG). Their language offers are not accepted; instead, communication continues in High German. On the basis of these experiences, they form language identities that can be described as “deviant identities”.

- 2.

- Purist norms and old normative authorities

A conservative-puristic language norm is inherent in all the statements of the 2011 corpus as an ideal. The “mixture” with High German is evaluated as proof of lack of competence and is pejoratively referred to as “kauderwelsch” (T-TK). This is remarkable in that such an ideal negates a language contact and exchange process that has lasted for about 400 years. At the same time, this perspective leads to a categorization of language variants as “errors”. This perspective is based not least on experienced corrections to language use by “older native speakers” (N-BF; N-SH) (Example 9).

- 3.

- Half competences

On the basis of the experience gained, the new speakers describe their competence as deficient. Their aim is to use the language correctly and effortlessly and for it to be as purely Low German as possible (Section 3.2.3). Typical “but” constructions in the sense of “I can already do XY, but not yet AB” are striking, as in the following Example 4.

| Example 4: Transcript corpus 2011: N-JG describes his but-competence (interview corpus 2011). | ||

| 138 | I: | MI interessiert nu egentlich (.) |

| 139 | wat du SÜLBM denkst; | |

| 140 | un wat du SÜLBM dor oewer seggen würdst. | |

| 141 | N-JG: | (1.2) |

| 142 | hm’ (-) | |

| 143 | also vielLICHT; | |

| 144 | ik bün BÄ:der worden- | |

| 145 | ik kann n BÄ:ten wat verTELLN- | |

| 146 | äwer ik wull nich seggen dat ik GOUD bün; | |

| 147 | NOCH nich. | |

| 148 | [da bruk ik noch [TIED för. | |

| 149 | I: | [hm. [hm-hm; |

| 150 | [so MIddl (.) vielLICHT; | |

| 151 | N-JG: | [so PUNKT. |

| 152 | also fö:r för en jungen MI:NSCHn? (.) | |

| 153 | I: | [hm-hm; |

| 154 | N-JG: | [künn ein viellicht SEGGn |

| 155 | kann ik VÄ:L. | |

| 156 | I: | [hm-hm; |

| 157 | N-JG: | [viellICHT. |

| 138 | I: | I am actually interested in |

| 139 | what you think | |

| 140 | and what you yourself would say about it. | |

| 141 | N-JG: | (1.2) |

| 142 | hm’ (-) | |

| 143 | so perhaps; | |

| 144 | I have become better- | |

| 145 | I can tell you a little bit- | |

| 146 | but I would not say that I am good; | |

| 147 | still not. | |

| 148 | [I still need [time for | |

| 149 | I: | [hm. [hmm-hmm; |

| 150 | [so medium (.) perhaps; | |

| 151 | N-JG: | [so full stop. |

| 152 | [so for a young man (.) | |

| 153 | I: | [hm-hm; |

| 154 | N-JG: | [one could say much easier |

| 155 | I can do a lot. | |

| 156 | I: | [hm-hm; |

| 157 | N-JG: | [perhaps. |

In Example 4 from the 2011 survey, the male member N-JG is asked to describe his competence. In terms of the structure of the discussion, we see here a partly corresponding treatment of the obligation to proceed, which is established by the question in line 138f. He evasively answers first that he has become better through the network, in line 144. He explicitly negates the evaluation of his competence as “good” in line 146, with the typical “but” phrase. In lines 152 and 163 (not part of the example 4), he arranges his competence in relation to the identity-building blocks postulated as central: age and speaking community: he can do a lot considering he is a young person, but not compared to a Low German speaker. He thus implicitly segregates himself from the group of competent Low German speakers and claims only limited membership. We see that differentiation is established here as a category of participants and that the positioning methods have shown frame one’s own identity as deviant and deficient. However, when we relate these statements to formal aspects of language use, these positioning processes appear in a completely new light. The meta-linguistic construction of insufficient competence is in blatant contradiction to the realized use of language: the variety used by N-JG—very similar to the native T-LÜ in Ex. 3—testifies to a high level of procedural competence. The language level shown here could be classified as B2 according to the CEFR. This can best be shown by taking a look at two phonological variants that are constitutive of Low German: First, it realizes the lenetration of the plosive [t] in bäder (l. 144) and the minimal diphthongization of the long vowel u: in goud (l. 146). The latter even points to knowledge of internal differentiation, in that he chooses the typical—and distinct-variant for his site and not a hybrid, inter-dialectal form.

The 2020 survey showed very similar views on the purist norm. However, the environment is described not so much as hostile to language in general, rather as unfriendly to speech since there are no competent dialog partners. Apart from T-LÜ, however, there are also consistently staged “but-competencies” (N-VN, T-SD, N-BF).

In Example 5, N-BF describes himself as “cheeky” when he explicitly claims to belong to the Low German speaker group. When asked where he would belong, he answers as follows:

| Example 5: Transcript corpus 2020: N-BF claims belonging but discusses associated problems. | ||

| 1171 | N-BF: | würd mich als VORpommern bezeichnen ((...)) |

| 1172 | wenn ich FRECH bin würd ich sagen- | |

| 1173 | ja ich bin mittlerweile n PLATTdüütschen jung; | |

| 1174 | I: | mhm (.) wieso FRECH? |

| 1175 | N-BF: | weil ich glaube dass ((...)) die bezeichnung |

| 1176 | plattdüütsch würde | |

| 1177 | also dass jemand sagt ich (bün’n) PLATTdüütschn- | |

| 1178 | würde ich fast nur den | |

| 1179 | MUTTersprachlern zunächst vorbehalten; | |

| 1180 | I: | mhm; |

| 1181 | N-BF: | ja? ich bin ich bin ein ich bin DÄne |

| 1182 | ich bin italIENer ((...)) | |

| 1183 | ich bin PLATTdeutscher is=is für mich son bißchen | |

| 1184 | ((...)) | |

| 1185 | würde=ich sagen eigentlich ist die bezeichung der | |

| 1186 | MUTTersprachler- | |

| 1187 | aber (.) da es die kaum noch GIBT- | |

| 1188 | I: | mhm |

| 1189 | N-BF: | würde ich mittlerweile sagen; |

| 1190 | dei plattdüütschen sünd dei | |

| 1191 | dei wat mit plattdüütsch MAken. | |

| 1192 | I: | mhm |

| 1193 | N-BF: | und (tominnest an dei ein oder annern ställ |

| 1194 | dat nutzen und UMsetzen) | |

| 1195 | I: | mhm |

| 1196 | N-BF: | und deswegen ja. würde ich sagen (.) (bün) ichn |

| 1197 | PLATTdeutscher. | |

| 1171 | N-BF: | would describe myself as Pomeranian ((…)) |

| 1172 | if I am cheeky I would say- | |

| 1173 | yes, I am now a Low German guy; | |

| 1174 | I: | mhm (.) why cheeky? |

| 1175 | N-BF: | because I believe that ((…)) the term |

| 1176 | “plattdeutscher” would | |

| 1177 | so that someone says I (am) PLATTdeutsche- | |

| 1178 | I would almost exclusively reserve for | |

| 1179 | MOTHER tongue speakers at first; | |

| 1180 | I: | mhm; |

| 1181 | N-BF: | yes? I am I am a I am Danish |

| 1182 | I am Italian ((…)) | |

| 1183 | I am a Low German is=is a little bit different for me | |

| 1184 | ((…)) | |

| 1185 | I would say is actually the name of | |

| 1186 | the native speakers | |

| 1187 | but (.) as they hardly exist anymore | |

| 1188 | I: | mhm |

| 1189 | N-BF: | I would say by now |

| 1190 | the Low Germans are the ones | |

| 1191 | who do something with Low German | |

| 1192 | I: | mhm |

| 1193 | N-BF: | and (at least in one or the other place) |

| 1194 | use and implement it | |

| 1195 | I: | mhm |

| 1196 | N-BF: | and therefore yes. I would say (.) I (am) |

| 1197 | a Low German | |

In contrast to T-LÜ in Example 3, N-BF here requires much more effort to communicate reasons that make his membership in the imaginary group of “Low German speakers” plausible. He implicitly assumes that his position is potentially controversial. This can also be seen in the framing of his behavior as “cheeky”. In doing so, he simultaneously inscribes himself into a “next-generation” of Low German speakers and shows resistance by questioning conventionalized attributions. In that way, he constructs a comparatively ambivalent positioning, partly within the group and ratifying its norms and partly outside the group, breaking established norms and revolutionizing them. At the same time, the example allows for processes of identity change: While N-BF in the 2011 survey communicated his affiliation rather cautiously or as a wish, here, he is making a new adjustment to the principles “dei plattdüütschen sünd dei wat mit plattdütsch maken”/Low Germans are those who do something with Low German“(l. 1190f.) and is actively enrolling in the community.

3.2.3. Idealizations: Normative Concepts of an Ideal Speaker: “a Low German” with a Phonologically Trained Heart

As the findings of the previous section show, the “other” network members seem to find it difficult to claim membership in the language community without a constitutive acquisition biography. A reversal of the acquisition biography is simply no longer possible for them—however much they may regret this. However, what does the ideal speaker of Low German look like, one whose membership is not questioned and whose role model the “others” work on? What characterizes an ideal speaker beyond a specific biography?

Rather abstract and diverse attributions are shown, based on a romanticized language ideology, as in Example 6, and hierarchizing language-structural phenomena, as in Examples 7 and 8.

| Example 6: Transcript corpus 2020: T-SD romanticizes belonging. | ||

| 1148 | I: | wat måkt ein gauden plattdüütsch schnacken UT? |

| 1149 | wat is wichtig? | |

| 1150 | wat würdest DU seggen? | |

| 1151 | T-SD: | na dat wat ick di von anfang an SECHT heff; |

| 1152 | dat möt ut HARten kommen. | |

| 1153 | UNbedingt. | |

| 1154 | un dat WOLLN ne? | |

| 1155 | tja wat anners kann man da nich seggen. | |

| 1148 | I: | what makes good Low German speaking? |

| 1149 | what is important? | |

| 1150 | what would you say? | |

| 1151 | T-SD: | what I told you from the beginning |

| 1152 | it must come from the heart | |

| 1153 | absolutely | |

| 1154 | and want it, right? | |

| 1155 | well, you cannot say anything else | |

In response to the question of good language use, T-SD uses the metaphor of the heart in Example 6 to establish the typical set pieces of a romantic transformation typical of lay linguistic myths (Davies 2010). In fact, she repeats these prerequisites for “good Low German usage” five times in the transcript, partially extended in “heart and soul”. She thus uses a typical pair formula, i.e., patterned word pairs that are usually realized together in a syntactic context. These traditional pairs also encode the often clichéd nature of language ideologies. The statements on her own activities with older people and children implicitly include T-SD in this “heart and soul community”. Such a concept thus allows her to join the community of speakers.

In addition, selected phonological variants were repeatedly seen in the interviews as relevant aspects of an accent that have an inclusive effect or were interpreted as indexical markers. For Low German, these included the realization of the apical R-sound [r] in the consonantal range (e.g., N-SH; T-SD; N-VN) and the realization of a dull A-sound [å] in the vocal range (e.g., T-LÜ). These variants are constructed in the interviews as distinctive shibboleths and socially registered as proof of competence equivalent to that of a native speaker and as an accent that successfully indexes authenticity (Hornsby 2015, p. 107; Johnstone 2016). Their mastery decides in the speakers’ consciousness whether they are entitled or not to belong to the language community.

In Example 7, N-SH describes a typical—deficit-oriented—self-evaluation of one’s own competence and makes the variable [r] explicitly relevant.

| Example 7: Transcript corpus 2011: N-SH describes learning difficulties and the shibboleth [r]. | ||

| 323 | N-SH: | naja diese geFÜHL wir können das |

| 324 | NIE wirklich vom KLANG her lernen. | |

| 325 | I: | hm-hm’ |

| 326 | N-SH: | das kriegen wir nich HIN. |

| 327 | ich kann überhaupt kein ER rollen also- | |

| 328 | I: | ((lachen)) |

| 329 | N-SH: | das IS (.) das klingt immer so FLACH; |

| 323 | N-SH: | well this feeling we can NEVER really learn |

| 324 | this from the sound. | |

| 325 | I: | hm-hm’ |

| 326 | N-SH: | we can’t manage that. |

| 327 | I can’t roll any ER so- | |

| 328 | I: | ((laughter)) |

| 329 | N-SH: | the IS (.) that always sounds so FLAT; |

The difficulties of achieving a “native-like accent” have been repeatedly described in the research literature as a typical characteristic of “new speakers” (i. a. Hornsby 2015, pp. 110–12). A comparison with the older “native-language” network member shows that the perspectives are identical: The relevance of the typical accent or the phonological level is rated consistently high by both sides.

In Example 8, T-LÜ expands on a narrative exclusion on the basis of the phonological, concrete vocal shibboleth of a dull and elongated a-sound, a mixture between [œ] and [з], which does not exist in standard German and is orthographically represented as [å].

| Example 8: Transcript corpus 2020: T-LÜ interprets vocalic shibboleths. | ||

| 891 | T-LÜ: | wiel hei ok mal wat (-)äh anners utspräken deit; |

| 892 | I: | mhm. |

| 893 | T-LÜ: | (--) ne? |

| 894 | dat (.) doran MARKT man; | |

| 895 | dor mark ICH jedenfalls GANZ genau ob | |

| 896 | ein’n plattdüütschen is odder NICH. | |

| 897 | besonders dat AH und dat (oh). | |

| 898 | I: | mhm. |

| 899 | T-LÜ: | also (.) dor mark ik GANZ genau ob se uns |

| 900 | verkackeiern oder nich. | |

| 891 | T-LÜ: | because he sometimes pronounces something (-) uh differently; |

| 892 | I: | hm-hm. |

| 893 | T-LÜ: | (--) right? |

| 894 | the (.) you can tell by that; | |

| 895 | that’s how I can tell exactly | |

| 896 | whether he is a Low German or NOT. | |

| 897 | especially AH and dat (oh). | |

| 898 | I: | hm-hm. |

| 899 | T-LÜ: | so (.) there I can see exactly whether they |

| 900 | are fooling us or not. | |

T-LÜ, in Example 8, expands on how pronunciation is the pivotal marker of entitlement to belong. As a native speaker (Example 3), he or she has the competence to make the distinct classification “ob ein’n plattdüütschen is orrer nich/whether one is a Low German is or not” (l. 895f.). To do this, he or she selects a specific linguistic variable, which is hierarchized and registered as an ingroup characteristic. The classification of the “false” realization of a variable as “verkackeiern/fooling” (l. 900) is also revealing. The utterance implies a normatively oriented deception in which they—the others—deceive us—the speakers—or not. In concrete terms, this means whether they have a legitimate or an unjustified claim to belong to the community of speakers—and—whether they are allowed to use the language quasi legally (l. 901, not part of the transcript in Example 8). The one doing the fooling has no claim to belonging—at least in the eyes of the native speaker T-LÜ.

A comparison with the results of the usage analyses is revealing here (see Section 3.1.2). There, too, the high dialectality quotient of the emails was largely based on phonological variants. The fact that these are mentioned in the narrative interviews is therefore by no means arbitrary but is reflected in use. A constitutive characteristic of the variety is a dominant phonological difference to standard German.

3.2.4. Preliminary Summary of Narrated Identities: Normative Hierarchy of Acquisition Scenarios and Competences as Aspects of Belonging

The results lead to the following answers to the sub-questions outlined above (Section 1.3) dealing with identity aspects: With regard to belonging, the aspects of identity are mainly language acquisition courses and competences, which are relevant in establishing demarcations between native and new speakers. Speakers with a family background (i.e., since childhood) and unrestricted competences, especially at the phonological level, can lay a legitimate claim to belonging. This hierarchization of the phonological level correlates with the variable-analytical findings of use (see Section 3.1.2). The email analyses also show a dominant phonological difference to standard German. While “native speakers” can fall back on an established nomenclature for positioning, the “others” use paraphrases. At the same time, the interview corpus 2020 reveals signs of change in such a way that these concepts will be partially questioned, reinterpreted and redesigned by a subsequent generation of speakers. This enables them to locate themselves confidently in the community without having to meet all the criteria. This is necessary because acquisition biographies simply cannot be reversed. The language attitudes marked in the utterances of these groups of speakers show numerous parallels to results of other studies of new speakers and point to seemingly universal structures.

However, the contrasting analyses of both groups of speakers also reveal numerous similarities in values, goals and norms that can facilitate successful interaction. The “gap” in the sense of (Hornsby 2015) does not seem so big here—as was the case with the language used in the emails. Rather, the differences can offer fertile insights and experiences for both sides, from which bridges can be built. The following Section 3.3 can provide further insights into this in the reconstruction of the motives for membership.

3.3. Motives of Participation

The network has now been in existence for 15 years with identical and changing members and a high 14-day meeting rate. This means that the members make comparatively high voluntary commitments, which gives rise to questions such as the following: What are the motives for network membership? What has kept the members together for over 15 years? What functions are associated with the network? What characteristics are attributed to the network, and to what does it appear comparable? What are the norms of language use and authorities that are negotiated collectively? Studies of the motivation for language acquisition and use among new speakers show the range of individual goals and, at the same time—implicitly—the problems of everyday use and acceptance (Jaffe 2015, pp. 31–35; Bermingham and Higham 2018).

3.3.1. Function as a Social Shelter—Social Cohesion in a Personal, Informal, Egalitarian Atmosphere

In both interview surveys, social components are highlighted as special characteristics of the network.

On the basis of quantified statements from the 2011 survey, (1) human familiarity, (2) error tolerance and (3) lack of constraints were characteristics of the network that the “new speakers” said were relevant to them (Figure 2 in Arendt 2012, p. 17).

- N-JG meets people “wichtig för mi worden sünd/that have become important for me” (l. 772);

- N-SH describes a “durchweg total freundschaftliches positives Gefühl/totally friendly positive feeling throughout “(l. 210);

- T-TK explains the function of meeting “nette Leute/nice people” (l. 179).

The 2020 interviews show similar results, with members describing what makes the network so special for them:

- N-BF: “kein Zwang kein druck/no obligation no pressure” (l. 72); “zu freunden kommen/come to friends” (l. 78);

- T-SD: “platt räden, gleichgesinnte, die dat bewusst pflegen/speak Platt, like-minded people, who consciously maintain it” (l. 714f.); “as ein lüttes stück to hus/like a little piece of home” (l. 956);

- N-VN: “freundschaften” haben sich herausgebildet/friendships have come out of it” (l. 794), “das macht Spaß/it is fun” (l. 827);

- T-LÜ: “de lockere Atmosphäre/the relaxed atmosphere” (l. 696), “ok privat bäden wat von’nanner wüssten/and get to know each other a bit” (l. 762f.).

The members experience themselves as equal in all their diversity. Just as everyone brings something of their own to read aloud, everyone contributes something to the meeting, such as biscuits, tea or vegetables: “un jeder bringt wat mit/ everyone brings something” (T-LÜ, l. 835). Through these attributions, the network and the meetings become a social shelter that ensures social cohesion in an informal, egalitarian atmosphere. Thus, identities of caring and friendship develop at the same time, and the network offers central components conducive to good mental health.

3.3.2. Function as Protection and Action Space—Protected and Ratified Use

The members of the network report in unison about difficulties in using the Low German language in everyday life. In their opinion, these difficulties have two causes.

First, it is due to a lack of dialog partners. Very few of them can find people to talk to in everyday life or at home, such as T-SD and T-LÜ, with whom they can then communicate in Low German only in some cases. T-LÜ formulates this normative exclusivity as follows: “un süss gifft dat minschen (.) mit dei ik blots plattdüütsch räden kann/then there are people with whom I can only talk in Low German” (T-LÜ; l. 1133f.). The younger members of the network, however, all report problems in finding suitable dialog partners, which explains the function of the network as a place of interactive use in everyday life. T-TK 2011 reports on these difficulties and the relevance of the network as follows: “ich KENN keinen der plattdeutsch kann, ne?/I DO NOT KNOW anyone who can speak Low German, ne? (T-TK; l. 126). In addition to discussions on everyday topics, the network also offers the opportunity to expand domains of use by regularly presenting literary texts in a scenic setting or reading out factual texts. In this way, the functional spectrum of language is illuminated in many ways, both in use and stored as meta-linguistic knowledge (Section 3.1.1).

Second, the network functions as a shelter from instruction and correction, especially for the “new speakers”, as these aspects also make use more difficult. They report in unison about experiences where their use of Low German was not only not ratified, but—beyond that—made the subject of interaction and—mostly negatively—evaluated. Thus, the interaction was framed as a test, and the other-initiated external correction by the mostly older speakers led to face-threats (Goffman 1999).

In the following Example 9, N-BF describes such corrections logically as a “schelle an n hinterkopp/slap on the back of the head” (l. 333), thus evaluating them as a quasi-physically tangible punishment.

| Example 9: Transcript corpus 2011: N-BF talks about corrections. | ||

| 311 | N-BF: | j!A!, jA der plattdeutschkreis, |

| 312 | also grade, grade auch ähm, | |

| 313 | so wie ihr uns AUfgenommen habt, die akzeptA:nz, | |

| 314 | I: | hm-hm’ |

| 315 | N-BF: | nämlich nicht, dass wenn man ebend |

| 316 | auf die alten trifft | |

| 317 | man gnadenlos immer korrigiert WIRD, ne? | |

| 318 | I: | hm-hm’ |

| 319 | N-BF: | dieses SOfort, |

| 320 | also das das hat mir eben doch inner späldäl | |

| 321 | früher immer sehr viel kOpfzerbrechen, | |

| 322 | deswegen hab ich mich da auch nicht | |

| 323 | getraut zu sprechen, | |

| 324 | die A:lten habm früher mit dir immer nur | |

| 325 | platt geredet, | |

| 326 | I: | hm-hm- |

| 327 | N-BF: | war ja sozusagen als kleiner junge mit |

| 328 | um AUfbauen helfen | |

| 329 | und sie haben mit dir nur plattdeutsch | |

| 330 | gerEdet und du musstest, | |

| 331 | wenn du was wolltest, auch plattdeutsch [zurück | |

| 332 | I: | [hm-hm` |

| 333 | N-BF: | nur wenn du denn was fAlsch gesagt hast, |

| 334 | dann wurdest du so richtig gemA:ßregelt, | |

| 335 | I: | hm-hm? |

| 336 | N-BF: | denn wurd sofORT gesagt das heißt so |

| 337 | und so und so und äh, | |

| 338 | grade bei BUCHstaben, | |

| 339 | also ich weiß noch ich hab immer bookstafen und | |

| 340 | bokstawen | |

| 341 | und sofort, wie so ne schelle ann hinterkopp | |

| 311 | N-BF: | yes, yes, the “Plattdeutschkreis”, |

| 312 | so just, just also um, | |

| 313 | how you have received us, the acceptance, | |

| 314 | I: | hm-hm’ |

| 315 | N-BF: | namely not that when you meet |

| 316 | the old people | |

| 317 | one is always corrected without mercy, right? | |

| 318 | I: | hm-hm’ |

| 319 | N-BF: | this immediately, |

| 320 | well, that is what has given me in the “späldäl” in the past | |

| 321 | a lot of headaches, | |

| 322 | which is why I did not | |

| 323 | dare to speak there, | |

| 324 | in the past the old ones used to talk to you in | |

| 325 | Low German, | |

| 326 | I: | hm-hm- |

| 327 | N-BF: | was helping build up |

| 328 | as a young boy | |

| 329 | and they only talked to you in Low German and you had to | |

| 330 | if you wanted something, | |

| 331 | also in Low German [back | |

| 332 | I: | [hm-hm` |

| 333 | N-BF: | only if you said something wrong |

| 334 | then you were really disciplined, | |

| 335 | I: | hm-hm? |

| 336 | N-BF: | because it was immediately said, that is called so and so |

| 337 | and so and so and uh, | |

| 338 | especially with letters, | |

| 339 | well I remember I always have “bookstafen” | |

| 340 | and “bokstawen” | |

| 341 | and immediately, like a slap on the back of the head | |

The special nature of the network is expanded on in contrast to the negative experiences of use in a theatre community. There, “reprimands” (l. 333) in the form of “merciless corrections” (l. 317) led to “a lot of headaches” (l. 321) and even fear of speaking (l. 322f.). Furthermore, the explanations present a monolingual language ideology oriented towards linguistic correctness, in which the older speakers (natives) are constructed as norm guardians of “their” variety.

Such difficulties can be met with resignation or courage. The members rely on courage. Courage to defy existing implicit and explicit, sometimes frightening standards of use. Consequently, courage is often a topic of discussion in the interview:

- T-SD: “denn […] hebben sei mihr maut platt tau räden/because […] gave me the courage to speak Low German” (l. 762); “dann bin ick ja ok mutig ne? […] denn heff ick ganz väl maut […] un heff wat up platt secht/then I am also courageous, ne […] then I have a lot of courage […] and said something in Low German” (l. 658ff.);

- N-BF: “aber dieser mut mit mit der runde zu sprechen/this courage to speak to the group” (l. 195);

- N-SH: “ja, naja denn hab ich ne weile mut gesammelt [to speak, B.A.]/Yeah, well, I gathered my courage for a while” (l. 65).

The experiences described both inside and outside the network make it appear as a place of protected and ratified use. It thus generates positive interactive experiences that can have a supportive acquisition effect, as numerous studies on language and discourse acquisition show (Arendt 2019b; Heller 2014; Stude 2014). As a consequence, use can be increased and improved in the long term, even outside the network.

In addition to the functions of use described above, some members also have a strong language policy motivation: Their use of the language ensures the preservation of the language. This is how T-SD describes their motivation for membership in the network “plattdeutsch pflegen im kleinen kreis/cultivating Low German in a small group” (l. 760). This basic attitude arises from a dominantly negative and conservative view of the current language reality, which makes the language appear to be endangered. This language attitude unites the members as well as the insight that they themselves must take responsibility for the protection and that this is possible through use and activities. For example, T-LÜ reports on Low German theatre plays, which he writes, N-BF on language policy activities and T-SD and N-VN on their educational work in schools and at work. All this is not without resistance or skepticism from the High German environment. These aspects form a stable and homogenizing evaluative attitudinal basis for all members.

Overall, the members present themselves as “identities of resistance” (O’Rourke 2018) and “braveness” at the same time. Both concepts testify to the bravery and thus also to chivalrous virtues that can be integrated into a positive self-image.

3.3.3. Function as a Place of Teaching and Learning—Knowledge Acquisition and Transfer

Many statements from both the new speakers in 2011 and other members in 2020 describe educational language practices such as homework and goals of knowledge acquisition and knowledge sharing. In the overall view of the narratives, the binary division of speakers into new and native is probably most clearly reflected here. The new speakers describe the network primarily as a place to test their knowledge and improve their language use, and the native speakers as a place to speak and pass on experiences. The following evidence should make this binary functional differentiation more plausible:

(1) Knowledge acquisition in the network

- T-SD praises “de Informationen de Input de man krägen deit/all the information the input you get” (l. 911);

- N-BF experienced the network as a “Offenbarung, dass es plattdeutsch auch außerhalb von kunst riemels […] gibt/revelation that Low German also exists outside of art “riemels” […]” (l. 184);

- N-VN “hat [das Netzwerk, B.A.] möglichkeit eröffnet Plattdeutsch richtig zu können/has [the network, B.A.] made it possible to be able to speak Low German correctly” (l. 671).