Abstract

This paper explores how attitudes affect the seemingly objective process of counting speakers of varieties using the example of Low German, Germany’s sole regional language. The initial focus is on the basic taxonomy of classifying a variety as a language or a dialect. Three representative surveys then provide data for the analysis: the Germany Survey 2008, the Northern Germany Survey 2016, and the Germany Survey 2017. The results of these surveys indicate that there is no consensus concerning the evaluation of Low German’s status and that attitudes towards Low German are related to, for example, proficiency in the language. These attitudes are shown to matter when counting speakers of Low German and investigating the status it has been accorded.

1. Introduction: “Language” Versus “Dialect”

Some languages have not always been languages but started off as dialects. Conversely, some languages have stopped being languages and have become dialects. Thus, the status of language varieties may change over time. This paper deals with such questions of status, focusing on a specific German situation, namely that of Low German. The core question here is whether Low German is a language or a dialect and what the consequences of this decision are. The interest is not so much in a strictly structural linguistic response to this question but rather in a more sociolinguistic one. The focus is not on how to technically distinguish a language from a dialect but rather on how so-called lay persons, as defined below, identify and explain this difference. The label such people attribute to a variety is crucial as it is typically accompanied with further qualities ascribed to the variety and its speakers, such as their attitudes. Moreover, conceiving of a variety as a language or dialect may lead to specific behavior. Thus, questions on the status of a variety are also essential when counting the number of its speakers. How all these aspects interact is described in the following.

First, a general definition of the labels “language” and “dialect” is in order, although this is not an easy task. The conceptual opposition of language and dialect initially “appears to be a value-free, self-evident conception” (Kamusella 2016, p. 164; for a recent account on this pair see Van Rooy 2020). From a very general perspective, a language is always a superordinate entity and a dialect a subordinate one (cf., for example, Haugen 1966). This underlines the general, asymmetric evaluation as the heart of the binary taxonomy. More detailed definitions might continue as follows: “In common usage, of course, a dialect is a substandard, low-status, often rustic form of language, generally associated with the peasantry, the working class, or other groups lacking prestige. […] Additionally, dialects are also often regarded as some kind of (often erroneous) deviation from a norm—as aberrations of a correct or standard form of language” (Chambers and Trudgill 1998, p. 3; see also Kamusella 2016, p. 166). Alongside the point that this understanding of a dialect is “in common usage” comes the declaration of its implicitness (“of course”). Hence, the common denominator of all of these qualities is the negative connotations or, more precisely, the lack of prestige attributed to dialects. As Kamusella puts it more bluntly: “those known as ‘language,’ [are] thus perceived positively as ‘true’ and ‘legitimate,’ and […] those pushed into the netherworld of often generalized contempt and neglect [are] branded as ‘dialects’” (Kamusella 2016, p. 166). Two points turn out to be decisive here: one is that this taxonomy is qualified as being used by non-linguists, and the other is the significance of the value (or the lack of it) that such people attribute to the linguistic entity in question. These aspects lie at the heart of research into language attitudes. Before turning to lay persons and language attitudes, however, a few words need to be said about the terminology used in this paper. If, burdened by their implicit, qualitative connotations, the terms “dialect” and “language” are not “particularly linguistic notion[s]” (Chambers and Trudgill 1998, p. 4), how should these linguistic entities be denoted when describing them because, surely, an academic text should be “speaking dispassionately” (Kamusella 2016, p. 165) about such matters. In this paper, the neutral term “variety” will be used (as Chambers and Trudgill 1998 do, for example). There is also an alternative to the canonized, binary taxonomy, as proposed by, e.g., Kloss (1967, 1976).1 This alternative set of labels and concepts will be explained in some detail in the next section. An additional note has to be made regarding the German concept of Dialekt. Contrary to its Anglophone counterpart “dialect”, the German Dialekt traditionally and still primarily denotes regional varieties, but it does not extend to social varieties in a more general sense (cf. Niebaum and Macha 2006, p. 1ff., see also the controversial labeling of the variety of Kiezdeutsch as a dialect by Wiese 2012 as discussed in Schröder 2013, for example).

To return to lay persons and language attitudes, research here focuses on speakers and what they think about varieties. That is, “what people say […] and what lies behind their statements” (Preston 1999, p. xxiv). The literature in this field is very diverse, dealing with different issues using a variety of methodologies or frameworks (see—to name but a few—Baker 1992; Bekker 2019; Garrett 2010; Preston 1989, 1999, 2011; Soukup 2019; Schoel et al. 2012; for the German context see Adler and Plewnia 2018, 2019; Dailey O’Cain 1999; Eichinger et al. 2012; Hundt 1992; Hundt et al. 2010; König 2014; Tophinke and Ziegler 2006). Accordingly, different labels with a range of connotations are deployed, such as language ideology, language regard, language belief, language attitudes (cf. Busch 2016; Horner and Bradley 2019; Preston 2011). This paper will use the term “attitudes.” Language attitudes used to be mostly dealt with in social psychology, but they have also been of special interest in linguistics for some time now. Eagly and Chaiken (1993, p. 1) define attitude as “a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favour or disfavour.” Thus, the evaluative nature of an attitude is essential. To emphasize the fact that people expressing language attitudes do not have linguistic expertise, they are usually called “lay linguists.” This is then mirrored in the label “folk linguistics”, (cf. Hoenigswald 1966; Niedzielski and Preston 2000; Preston 1982, 2019). The terms “lay linguist” or “lay person” thus contrast with “trained” or “academic linguists” (e.g., Bock and Antos 2019; Davies 2008; Milroy 2001).

As indicated above, using the labels “dialect” and “language”, and thereby categorizing entities, has certain side-effects. This applies when speakers think and talk about their own variety but also when others do because “[t]alking of languages, as is done using the concepts that at present we have at our disposal in the Western intellectual tool box, is not a neutral discussion, let alone idle talk. Depending on which turn the discussion takes, it may mean: the unmaking of a language or the creation of a new one from a dialect; the demotion of a language to the rank of a dialect; or the subsuming of a ‘free flowing,’ ‘unmoored’ dialect under the ‘umbrella’ of an expanding national or state language, thus entailing the disappearance of the former” (Kamusella 2016, p. 182). In other words, using a certain label for a variety involves so much more than “idle talk;” it also categorizes and positions it. The paper at hand is not so much concerned with how specialists technically define, categorize, and position the concepts of language and dialect but rather what speakers themselves think of them and what values they attribute to these concepts. Their acceptance of, loyalty to, and explicit identification with a certain way of speaking are important (cf. Haugen 1966, p. 933; Barbour and Stevenson 1998, pp. 8, 13). The speakers’ decisions and behavior regarding a specific variety are connected to their attitudes towards varieties in general.

Categorizing and positioning varieties by using certain labels is especially relevant in surveys on language, and particularly those items which involve counting the number of speakers. Usually, such items are worded using labels lay persons know and can deal with so that they can answer them appropriately.2 Lay persons’ perceptions and evaluations are crucial because they are strongly interrelated with language statistics. If lay persons conceive of their variety as a language, they may react differently to an item on that variety than lay persons conceiving of it as a dialect. Thus, seemingly simple questions aimed at counting the speakers of a variety may be understood und answered differently according to the status attributed to the variety in question. All this is particularly relevant for varieties whose status is unclear or contested (see here, for example, Tamburelli 2021; Tamburelli and Tosco 2021). The existence of near-dialectized languages like Low German “poses a problem to the statistician for which often there seems to be no satisfactory solution” (Kloss 1967, p. 37; see Section 2 for an explanation of the terminology). Even though it is stating the obvious, the main problem here is the following: if an item in a survey asks explicitly about languages, what will happen to varieties whose status is unclear? Will speakers of these varieties feel addressed by the item and name their variety (or respond in the affirmative), or will they not? Depending on this, the number of speakers supposedly elicited by the item may differ considerably, potentially challenging the reliability of such language statistics. There are variations on this problem, for example: when certain languages are enumerated in a list of possible responses to an item and others are not, such as varieties with a contested status, or when responses given by speakers of such varieties are classified as inadequate and are deleted in the editing process.3 Thus, the attitudes of lay persons invariably affect language statistics as it is lay persons who usually respond to such items and not language experts (and some of these surveys are also designed by lay persons). It does not end here: numbers produced by such surveys reinforce attitudes to varieties. That is, if a certain variety is not listed as a language in the results (or not named in a list of possible responses, or the presentation of the results employs inadequate labels), this will lead to specific interpretations regarding the evaluation of this variety.

This paper deals with all of these matters and how they interact in the context of Low German, which is spoken in Northern Germany. The particularities of its linguistic situation are explained in the following section. Based on a set of representative surveys (Section 3), attitudes towards and evaluations of Low German are described (Section 4). The fifth section sheds light on the issue of counting speakers of Low German. The conclusion (Section 6) consolidates all these aspects and elaborates on how they are interrelated.

2. Low German

Low German is spoken in northern Germany. The area where it is spoken stretches from the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein in the north to the northern parts of the states of Brandenburg, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Saxony-Anhalt in the south (cf. the map in Figure 1). In this area different varieties of Low German are spoken. In terms of language structure, Low German belongs to the North Sea Germanic group (Ingvaeonic), as do English, Frisian and Dutch (cf. Hawkins 2008). The Low German varieties differ greatly in structure from Middle and Upper German dialects (e.g., regarding the sound system; for more details on structural details, see Subchapter 5.3.2 in Goltz and Kleene 2020). Historically, it is an independent autochthonous language.

Figure 1.

The area of Low German (cf. Goltz and Kleene 2020, p. 172).

Standard German started to be used in the Low German language region in the 16th century; from its initially limited use in the written and spoken language used by the upper social classes, it spread more and more until it was finally used as a spoken language by the entire population on a broad basis. This last step took place at different times in different regions, most recently probably in East Frisia and Schleswig-Holstein in the second half of the 20th century (cf. Elmentaler 2009). Today, for most of the region’s inhabitants, Standard German is the language used in all communicative contexts. Low German occurs only to a very limited extent and, above all, only orally, that is in communication situations of close communicative proximity (with the family or in small-scale, locally bound speaker groups, see Höder 2011). It also plays a special role in radio broadcasting, theater, and everyday oral communication in certain occupations such as agriculture and care of the elderly. Stellmacher describes the linguistic situation as being a kind of latent or hidden diglossia (cf. Stellmacher 2000; see also Wiggers 2012) since Standard German is, in principle, used by everyone. The characterization of spoken Low German as a language of proximity (Nähesprache) also extends to Low German written language (cf. Elmentaler 2009, p. 36ff.). One characteristic stylistic difference between written Low German and written Standard German is that conventionalized oral-narrative forms are common in written Low German (simulation of the oral form). In addition, there is no supra-regionally standardized and codified orthography in Low German, but rather various spelling systems compete with each other (cf. Kellner 2002, cited in Elmentaler 2009).

2.1. Language or Dialect?

Bearing in mind the issues associated with distinguishing between languages and dialects, there is an alternative, proposed by, e.g., (Kloss 1967, 1976).4 He distinguishes between Ausbausprachen (‘languages by development’) and Abstandsprachen (‘languages by distance’). Ausbausprachen are “languages that are considered as such because of their extension into tools for qualified application purposes and areas” (Kloss 1976, p. 301). Abstandsprachen are defined by their structural (and not geographical) distance and are further subdivided into seemingly dialectalizable distance languages, and distance languages that are not (seemingly) dialectalized (near-dialectalized languages; cf. Kloss 1976, p. 305). Using this model and the processes of (re)shaping (Ausbau) and (near-)dialectalization ((Schein)Dialektisierung), it is possible to describe the status of certain varieties in a more adequate fashion. This model also allows for diachronic changes (e.g., Serbo-Croatian being reshaped into Serbian and Croatian (Ausbau), or the dialectalization of the Ausbau language Scots, cf. Millar 2018 on the latter). According to this model, Low German is a seemingly dialectalized or near-dialectalized Abstandsprache (cf. Kloss 1967, p. 35). Historically, by the mid-20th century, Standard German had taken over the official language domain in Northern Germany, and Low German had been dialectalized while still an Abstand language. Currently, this situation is changing again, with Low German seemingly losing its dialectalization status in 1999, as discussed below. Thus, the tools provided by Kloss’s more detailed terminology would surely facilitate a more accurate description of the status of Low German. However, this framework did not entirely replace the binary taxonomy of “language” vs. “dialect”, and—most importantly for the purpose of this paper—it is certainly not known or used by lay persons. Therefore, when addressing actual speakers, this terminology quite simply cannot be used, although it may be technically more adequate, because it is not intelligible to lay linguists.

Thus, for lay persons the prevalent labels are still “language” and “dialect”, and to complicate matters regarding Low German, the current lay assessment of its status is not clear. From a linguistic perspective, arguments in favor of classifying Low German as a language are of a structural and historical nature, including the autonomous grammar of Low German, its lexeme inventory, and its historically important functions, for example as an official language (see Goltz and Kleene 2020, p. 188ff.). These arguments were also decisive in including Low German in the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (see below). It is, however, relatively common in the literature to classify Low German as a dialect (cf. Barbour and Stevenson 1998, p. 12). Arguments in favor of Low German as a dialect include its regional limitations, its predominant use in situations of proximity, its restriction to specific communicative situations, its lack of standardization and it being roofed by Standard German (see Löffler 2003, p. 5; Goltz and Kleene 2020, p. 188). In the 1990s, the status of Low German was discussed extensively by linguists and the Low German language community (cf. Schröder and Wagener 1991; Speckmann 1991; see also the contributions in Jahrbuch des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 20195, and in Korrespondenzblatt des Vereins für Niederdeutsche Sprachforschung 20196; Walker 2018 speaks of a “Renaissance of European regional and minority languages” already emerging in the mid-1970s). This discussion finally culminated in the admission of Low German into the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML, cf. Council of Europe 1992a, 1992b). According to Walker (2018, p. 174), it was thanks to the political will of the Low German language community and its persuading the German government to fight for it that Low German was included in the ECRML (cf. also Oeter and Walker 2006, pp. 259–63).7 The ECRML came into effect in Germany in January 1999. Regarding Low German, the ECRML holds in eight federal states (Brandenburg, Bremen, Hamburg, Lower Saxony, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, North Rhine-Westphalia, Saxony-Anhalt, and Schleswig-Holstein; cf. Bundesraat för Nedderdüütsch 2014). It is important to note that Low German is explicitly treated as a regional language whereas the other relevant languages for the German context, i.e., Danish, Frisian, Romanes, and Sorbian, are treated as minority languages. The two concepts of “regional language” and “minority language” are handled differently by signatories of the ECRML. Usually, they are used interchangeably as synonyms. France, however, prefers the label “regional languages” (langues régionales) over the label “minority languages” (cf. Walker 2018, p. 185ff.) whereas the explicit distinction between a regional language and minority language is a German specificity. Low German is used on German territory but it is not a minority language because the speakers of Low German do not constitute a national minority (cf. Boysen et al. 2011; Oeter 2007; Woehrling 2005, p. 55).8 The two categories of “minority language” and “regional language” are essentially political and legal constructs but the most important point here for Low German concerns the “language” part of the term. Thanks to the ECRML and its ratification in Germany, Low German was officially assigned the status of a language, and this explicitly in contrast to German dialects and the languages of migrants in Germany (cf. Part I, Article 1 of the ECRML, see also Woehrling 2005). Of course, this is not the only effect of the ECRML. What is now state-imposed support of the Low German language (with measures to protect and expand it) has led, for example, to Low German once again being anchored as a learnable (second) language in educational institutions (e.g., kindergartens, schools, and universities), thus creating new speakers of Low German. A further consequence of the fact that Low German is being used as the language of instruction in several states in the Low German region is that a standardized variety is emerging. In the medium term, this may lead to a reduction in small-scale differences between the Low German varieties (see Elmentaler 2019, p. 572). In the long term, this may also add to the revaluation of Low German’s status. A reflection of this revaluation can already be seen in lay persons’ judgments of Low German’s status (see Section 4). The question thus arises as to what lay persons think about the current status of Low German. According to Kloss (1976, p. 306), the average North German farmer in the 1970s perceived his Low German as a dialect of the German language. Nearly fifty years later (and just over twenty years after the ECRML), the perception of the status of Low German by lay persons is no longer so clear. The ECRML and its effects have certainly influenced the general public and lay opinion. While Low German was previously characterized as being of low prestige, it has gained in prestige considerably as a result of its legal classification as a regional language and its associated linguistic and legal upgrading. The extent to which this affects the actual attitudes of lay persons is covered in Section 4 and Section 5.

2.2. Terminological Diversity

A variety of labels are used in German to designate Low German. In addition to Niederdeutsch, which is used especially in academic contexts, the terms Plattdeutsch and Platt are also common. The last two are mainly used by the speakers (or lay persons) themselves.

The term Platt is not to be understood as “flat”—although that is its literal meaning in German—or “flat countryside”, but originally meant clear, distinct, and understandable for everyone (cf. Lasch 1917). By the 17th century at the latest, the term Platt had acquired a negative meaning (see Niebaum and Macha 2006, p. 4) in which the term Platt stood for “simple, coarse”. In the last third of the 19th century, Platt appeared as a name for a regional variety without evaluative connotations (just as the more or less synonymous terms Dialekt and Mundart, see Niebaum and Macha 2006, p. 4). The term Platt thus not only describes a regional variety in a broad sense but also a specific one of them, namely the Low German Platt. As part of the regional scope of the meaning, which is limited to the Lower German area, there is also an area that is especially meant by the term Platt or “Low German,” namely Northern Low German or the so-called Küstenplatt (i.e., the Platt of the coast; see Elmentaler 2019, p. 567f; Sanders 1982, p. 84; Stellmacher 1987, p. 10).

Furthermore, the terms Platt (in combination with a place name) and Plattdeutsch are used not only in the Lower German region to designate Low German but also in the West Central German region (e.g., Eifeler Platt but also Lorraine Platt, cf. Beyer and Plewnia 2021). The German-speaking area is roughly divided into two parts (cf. Atlas zur deutschen Alltagssprache, AdA 2003; Elspaß 2007): in the south and east, the local dialect is called Dialekt (or Mundart), while in the west and north it is called Platt. Thus, the use of the term Platt is not restricted to the Low German region.

This variety of terms and meanings leads to special challenges in the context of empirical investigations and surveys, particularly concerning the wording of items including these terms but also the difficult interpretation of these terms when they are given by respondents in open-ended items. This means that if, in a nationwide survey of German, an item includes the term Platt, it is not automatically clear what is meant by it or whether it will be understood by all participants in the same way. Likewise, when a respondent gives a simple reply like Platt, it is not easy to judge which linguistic variety is actually meant. In quantitative surveys, however, it is particularly important that the items are not ambiguous (see Stellmacher 1987). It is evident that these issues have an impact on counting speakers and they need to be accounted for (see Section 5.3).

2.3. The Spectrum of Language Varieties in Northern Germany

To make matters even more complicated, the vertical language spectrum9 in the Low German area does not only consist of Low German and Standard German. Within this constellation, there is also a regionally specific version of Standard German (depending on the terminology used, it is called an accent, regiolect, regional colloquial language, North German regiolect with Low German elements; cf. Elmentaler 2019; Höder 2003; Mihm 2000). It is assumed that there are various contact and convergence phenomena between the Low German and the Standard German spectrum (see the model of Diasystematisierung, ‘diasystematization,’ in Schröder 2015, p. 35). For the historic situation, it can still be assumed that there are two clearly separable poles—the Low German one (as the base dialect) and the Standard High German one (as the standard language)—a rupture between them, i.e., a diglossic model (see, for example, König 2015, p. 134f.). For the current situation, the rupture is no longer that clear (see the beginning of Section 2 above on the diglossic situation regarding Low German).

Apparently, this regionally accented Standard German is being called Northern German (Norddeutsch) by the speakers themselves. As is often the case when the basic dialect is fading, this regional standard (regiolect) is reinterpreted as being a dialect as for most speakers it represents the most dialectal way of speaking. As a result, the term Norddeutsch adds to the already existing quite diverse battery of terms used to describe the complex linguistic situation in Northern Germany. There is the term Niederdeutsch which is mostly used in academic and official contexts, the terms Plattdeutsch and Platt, which are mainly used by the speakers themselves—with the term Platt also being used in other regions of Germany to refer to the local dialect—and finally, there is Norddeutsch.

3. Surveys

Carried out with the participation of or on behalf of the Institute for the German Language (Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache, IDS), three recent surveys provide the basis for the analysis here. The questionnaires and items were designed by the author’s research group, which then edited and analyzed the resulting data. All three surveys are representative. This means that the results can be interpreted as being representative of Germany’s resident population. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the surveys.

The first survey is the “Germany Survey 2008” (GS2008), which was conducted in the fall of 2008 for the IDS and the University of Mannheim as a nationwide telephone survey by the Wahlen research group (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen). In total, 2004 German residents were asked about their language repertoire and their attitudes towards languages and regional varieties of German, language norms, language decay and the like. For detailed results, see Gärtig et al. (2010).

The second survey is the “Northern Germany Survey 2016” (NGS2016), conducted in the summer of 2016 in cooperation with the Institute for the Low German Language (Institut für niederdeutsche Sprache, INS). In this case, 1632 residents of the Northern German-speaking area were interviewed in a telephone survey by the Wahlen research group. The topics included the interviewees’ competence in and use of Low German as well as evaluations and attributions of Low German and standard German. For initial results, see Adler et al. (2016, 2018).

The third survey is the “Germany Survey 2017” (GS2017), which the IDS conducted in the winter of 2017/18 in cooperation with the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) as part of the innovation sample of the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP-IS) of the DIW.10 The GS2017 consists of two subsamples: a main sample of 4339 respondents (data collected via personal interviews) and a subsample of 1439 respondents (data collected via online questionnaires). In the GS2017, respondents were asked about different language-related subjects, such as their language repertoire, attitudes towards languages and regional varieties of German, language decay, language variation, attitudes towards multilingualism. For some results, see Adler et al. (forthcoming) as well as Adler and Ribeiro Silveira (2020).

In the GS2008, 52.7% of the respondents were women and 47.3% men, with 15.5% aged 18 to 29 years, 52.9% aged 30 to 59, and 31.6% 60 years or older. Nearly half, or 44.7%, of the respondents had completed 9 years of formal school education (Hauptschulabschluss or lower secondary school certificate), 30.7% 10 years (Mittlere Reife or intermediate school certificate), and 24.6% 12 years and more (Abitur or upper secondary school certificate). All sixteen German federal states were represented. The number of respondents from each state corresponded to the relative population size of each state, i.e., more populous states were represented by a larger number of respondents and less populous states by fewer respondents (e.g., North Rhine-Westphalia: 21.5%, Bavaria: 15.0%, Bremen: 0.9%, Saarland: 0.8%).

The NGS2016 included 52.2% women and 47.8% men, with 17.4% aged 16 to 29, 49.2% aged 30 to 59, and 33.4% 60 years or older. Around one third, or 32.2%, of the respondents had a lower secondary school certificate, 35.5% an intermediate school certificate, and 31.2% an upper secondary school certificate while 1.1% did not give any information on their level of education. Only eight federal states were represented, based on where Low German is spoken and again in relation to their population size, namely Bremen (3.0%), Hamburg (6.8%), Lower Saxony (37.6%), Mecklenburg-West Pomerania (8.3%), Schleswig-Holstein (13.8%) as well as the northern parts of Brandenburg (7.5%), North Rhine-Westphalia (17.0%) and Saxony-Anhalt (5.9%).

The GS2017 was made up of 51.8% women and 48.2% men. The average age of the respondents was 51 years (with a standard deviation of 18.8 years); the youngest respondent was 17 years old and the oldest 96. Just over one quarter, or 26.4%, of the respondents had completed 9 years of formal school education, 29.6% 10 years, 6.6% 12 years, and 23.4% 13 years. All sixteen German federal states were represented according to their relative population size (e.g., North Rhine-Westphalia: 21.4%, Bavaria: 16.8%, Bremen: 0.9%, Saarland: 1.3%).

4. Attitudes towards Low German

4.1. Attitudes towards the Status of Low German

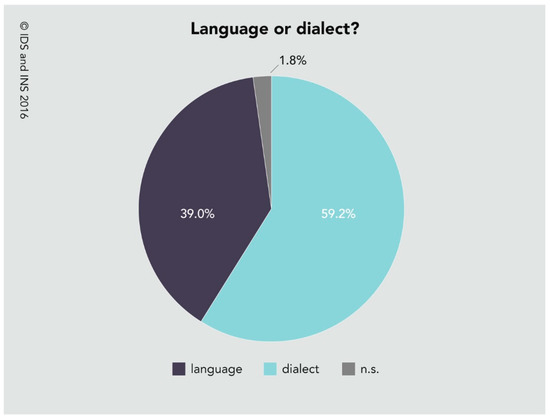

Previously there had only been anecdotal data on people’s assessment of the status of Low German, mostly based on qualitative interviews; most of the data came from small or locally restricted samples (see, for example, Arendt 2010, 2019, and Scharioth 2015 or other publications from the SIN project, such as Elmentaler et al. 2015). To fill this gap, the NGS2016 elicited data on how people assess the status of Low German. The survey was conducted in the entire Low German area, and the sample was large and representative (cf. Section 3). The respondents were asked directly whether they thought of Low German as a language or a dialect.11 The question about its status did not seem completely absurd for the interviewees: almost all of them answered the question, with only 1.8% preferring not to give an answer. The results show that the assessment of its status is not very clear (see Figure 2): A majority (59.2%) considered Low German to be a dialect while two-fifths (39.0%) answered that Low German is a language.

Figure 2.

The assessment of Low German’s status: Language or dialect (n.s. = not specified; NGS2016; Adler et al. 2018, p. 29).

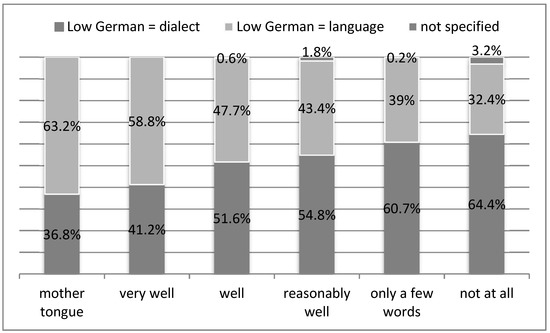

A closer analysis of the data revealed that the main factors connected to the assessment of the status of Low German are the following: competence in Low German, place of residence, and other attitudes towards Low German. Figure 3 displays the distribution of the assessment of Low German’s status according to the respondents’ self-reported proficiency in Low German. (See Section 5.3 below for more details on eliciting the participants’ proficiency in Low German.)

Figure 3.

The assessment of Low German’s status by proficiency in Low German (NGS2016).

It is mainly respondents who said that they speak Low German (very) well or as a mother tongue who considered it a language. The rating is particularly high among those who say that Low German is their mother tongue (see Section 5.3.1 below for a more detailed description of the answers to the question on the participants’ mother tongue): 63.2% in this group said it is a language (n = 36), while only 36.8% of said it is a dialect (n = 21). The responses were similar for (very) good speakers of Low German, with 58.8% and 47.7%, respectively, assuming that Low German is a language.

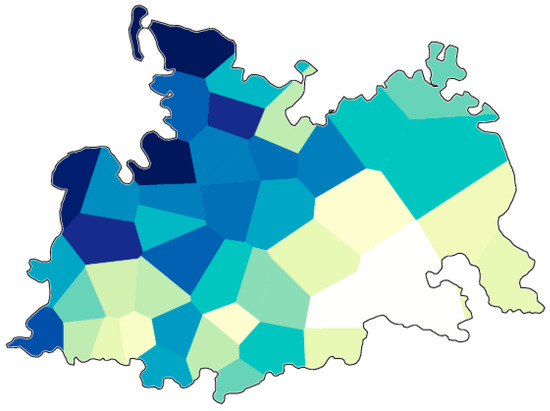

Figure 4 below illustrates the proportion of respondents categorizing Low German as a language by region. The regional units used in the map are composed of (groups of) rural districts. The darker the coloring is, the higher the proportion of respondents who said that Low German is a language.

Figure 4.

Proportion of respondents categorizing Low German as a language per region (using Gabmap; NGS2016).

The assessment of the status of Low German varies greatly from region to region. The proportion of respondents who considered Low German a language is highest in the northwest of the survey area and decreases towards the southeast. This distribution coincides with the distribution of proficiency in Low German: Low German is spoken most in the northwest of the region and proficiency decreases towards the southeast. The darkest areas more or less correspond to the region of the so-called coastal Low German (Küstenplatt), which is perceived as being the region where the “best” and the “most” Low German is spoken (see Adler et al. 2018, p. 23ff., see also Section 2.2).

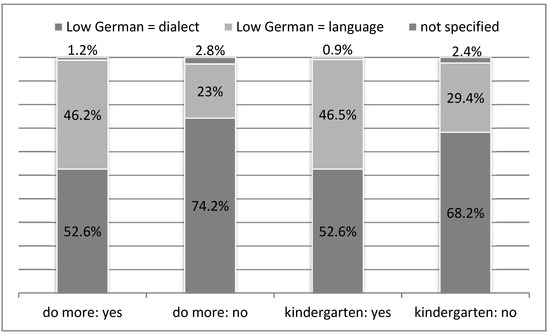

Figure 5 shows the connection between specific attitudes towards Low German and the assessment of its status. In the NGS2016, one item asked whether participants generally think that more should be done for Low German and another was related to how respondents feel about Low German kindergartens.12 Respondents who thought that more should be done for Low German and those who would send their child to a Low German kindergarten are both more likely to evaluate Low German as a language. Thus, 46.2% of the respondents who thought that more should be done for Low German consider it a language in comparison to only 23.0% of those who did not think that more should be done for Low German. Similarly, 46.5% of the respondents who would send their child to a Low German kindergarten said that Low German is a language compared with only 29.4% of those who would not send their child there. Therefore, it seems that positive attitudes towards Low German are also connected with the assessment of its status in that respondents with more positive attitudes towards Low German are more likely to consider Low German a language. Of course, these attitudes themselves are also related to Low German proficiency (see Adler et al. 2018, pp. 32ff. and 36ff.).

Figure 5.

The assessment of Low German’s status by other attitudes on Low German (NGS2016).

4.2. Evaluations of Low German

While the previous section dealt with the status of Low German, this one analyses evaluations of Low German which were elicited via the Attitudes Towards Languages scale (AToL scale, cf. Schoel et al. 2012; Adler and Plewnia 2018). The AToL scale is a reliable, valid and generalizable instrument to measure attitudes towards languages. It can be and has been used to measure attitudes towards languages and dialects. The AToL scale consists of three dimensions: value, sound, and structure, which are defined by a set of semantic differentials. This instrument was used in both the regional NGS2016 and the nationwide GS2017 to measure attitudes towards Low German and also towards Standard German. For the sound dimension, different items were used; therefore, this section only explores the results of the value and structure dimensions.

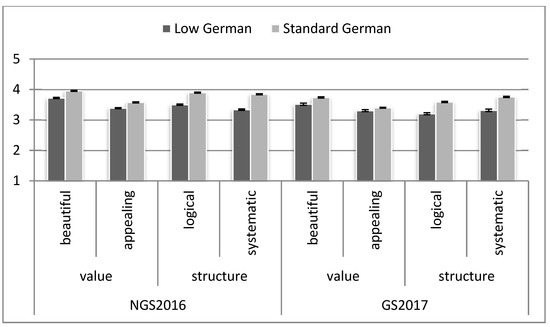

In the NGS2016, respondents were asked to rate Low German (Plattdeutsch) and Standard German (Hochdeutsch) according to the following semantic differentials on a five-point-scale: “beautiful”/“ugly” and “appealing”/”abhorrent” (value) as well as ”logical”/”illogical” and “systematic”/”unsystematic” (structure),13 allowing a comparison of the assessments of Low German and Standard German. The results from the NGS2016 are illustrated on the left-hand side of Figure 6, which plots the mean of each item, with 1 on the y-axis representing the “negative pole” and 5 the “positive pole” of each semantic differential:

Figure 6.

Evaluations of Low German and Standard German (AToL scale, NGS2016 and GS2017).

On almost all items the standard is rated more positively than Low German. This is a typical dialect-standard pattern (cf. Adler and Plewnia 2019; Schoel and Stahlberg 2012): dialects have less positive evaluations, especially on the structure dimension. In the NGS2016, the difference between the ratings for Low German and Standard German is particularly large for this dimension. Here, it is important to bear in mind that the standard variety is perceived as the well-established norm. Thus, the difference in ratings for structure comes as no surprise. As for the value dimension, the difference in ratings is less pronounced: both have relatively high ratings, with Standard German again higher.

It has already been shown that attitudes towards languages and dialects are related to how close or distant the evaluators are to/from the variety they are rating (known as the proximity effect, cf. Adler and Plewnia 2019, p. 147). The NGS2016 was restricted to Northern Germany, covering the home region of Low German. Thus, it is revealing to compare these results with the corresponding results in the nationwide GS2017, which also includes respondents from all other parts of Germany, not only the North. The results are displayed on the right-hand side of Figure 6.

In the GS2017, respondents were asked to assess Low German and German (Deutsch) using the same AToL scale.14 When assessing Low German, the interviewers always used both labels, Niederdeutsch and Plattdeutsch. The pattern of these ratings of Low German and German in the GS2017 strongly resembles the pattern in the NGS2016: German has the highest ratings on both the value and structure dimensions, although the difference is not so great for the item “appealing”. Therefore, the general distribution again reveals the typical dialect-standard pattern. Additionally, as is to be expected, the ratings for Low German are a little lower in the nationwide survey (GS2017) than in the survey conducted in its home region (NGS2016). This makes sense as outside the Low German area, people—when they speak dialect—speak other German dialects. Interestingly, however, the difference does not only affect the ratings for the home variety, Low German, but also for Standard German. This means that in general, ratings for both Low German and Standard German are higher in Northern Germany. For Low German, this can certainly be explained by proximity; as for Standard German, the reason might be a similar one. The German North is known for Standard German being very deep seated there (see Section 2 on the linguistic situation in the Low German area). It seems that the Northern respondents related to the Standard variety more closely as their variety.

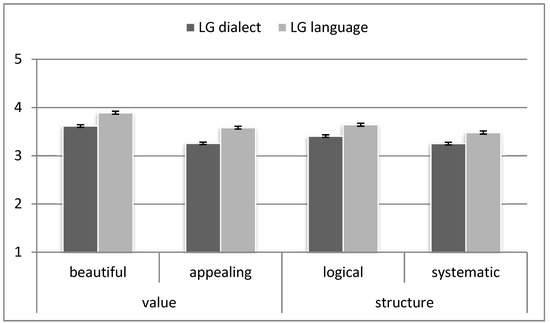

A closer analysis of the data reveals two main factors which are related to the assessment of Low German: how respondents evaluate Low German’s status (cf. Section 4.1 above) and their proficiency in Low German. Figure 7 shows the results of the AToL ratings for Low German according to whether the respondents thought of Low German as a dialect or a language (with 1 on the y-axis representing the “negative pole” and 5 the “positive pole” of each semantic differential).

Figure 7.

Evaluations of Low German (LG) by Low German’s status assessment (AToL scale, NGS2016).

On all four items in the value and structure dimensions, the ratings turn out higher for the respondents who considered Low German a language, the difference being more pronounced for the items on value. It seems that the evaluation of Low German by respondents who consider it to be a language resemble the ratings of Standard German, i.e., the items are being assessed more positively. Figure 8 below displays the ratings of Low German and Standard German according to the different evaluations of the status of Low German (with 1 on the y-axis representing the “negative pole” and 5 the “positive pole” of each semantic differential):

Figure 8.

Evaluations of Low German (LG) and Standard German (SG) by Low German’s status assessment (AToL scale, NGS2016).

On the value dimension, the lowest rating for both “beautiful” and “appealing” is for Low German by respondents who considered it a dialect. The three other means on each of the two value items (Low German by respondents considering it a language and both Standard German ratings) are higher in comparison. For the “appealing” item, they are more or less the same while for the “beautiful” item, the rating of Standard German by respondents who considered Low German a dialect is slightly higher. On the structure dimension, there is a clear difference between the Low German and Standard German ratings, with the Standard German ratings turning out higher on both. However, the Low German ratings coming from respondents who considered Low German a language tend to approach the higher ratings of Standard German. Altogether, the ratings on Low German are clearly related to how respondents assess the status of Low German. Those who considered it a language rate it quite similarly to their rating of Standard German. Thus, the language Low German is assessed similarly to the language Standard German, i.e., more positively, than when it is attributed the status of a dialect.

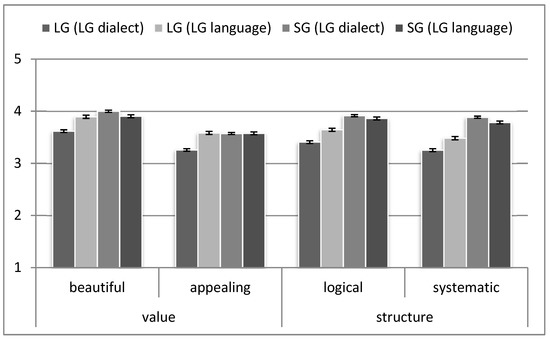

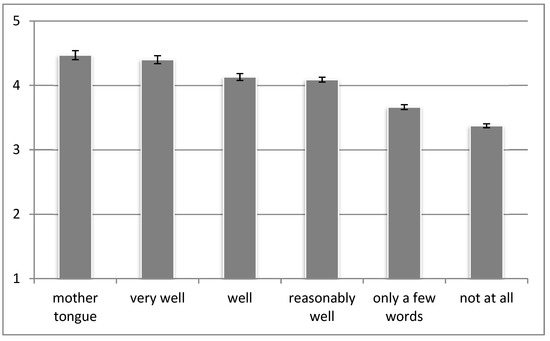

It is not the status assessment alone that affects the evaluations of Low German; proficiency in Low German is also a relevant factor. Figure 9 illustrates this effect for the “beautiful”/”ugly” item (with 1 on the y-axis representing the “negative pole” and 5 the “positive pole” of each semantic differential).15 The respondents are subdivided according to their self-reported proficiency in Low German starting on the left with Low German identified as the mother tongue, followed by the group of respondents speaking Low German very well and finishing on the right with those who say that they do not speak Low German at all (see Section 5.3 below for more details of items on the mother tongue and language proficiency).

Figure 9.

Evaluation of the item “beautiful”/“ugly” for Low German by proficiency in Low German (AToL scale, NGS2016).

The trend is evident: the ratings are higher the higher the proficiency in Low German is. Those who speak Low German very well rate it as more beautiful than those who speak it well or reasonably well, who rate it as more beautiful than those speaking only a few words of Low German or not speaking it at all.

To sum up, the evaluations of Low German based on the AToL scale are related to the status attributed to Low German and the proficiency the respondents have in Low German. Low German has the highest ratings from respondents who think of Low German as a language and who speak it (very) well or even call it their mother tongue. There are also differences between the regional and national results. It seems that while Low German is rated more highly in its home region than in the nationwide survey (as expected), Standard German also gets a higher rating in the Low German area compared with the national results. This might be explained by the special role of Standard German in the German North, especially compared with other regions in Germany where the constellations of dialect and Standard German are different (cf. Section 2, see also Adler and Silveira 2020).

5. Counting Low German

Following on from an analysis of attitudes towards Low German, this section focuses on statistics relating to Low German. As stated above, the counting of speakers is closely associated with language attitudes, especially lay persons’ attitudes towards the variety concerned. It starts with a description of the status quo of official language statistics in Germany (Section 5.1), the known numbers of speakers of Low German (Section 5.2), and a more detailed analysis of the specific challenge with regard to items and open-ended responses in language surveys concerned with Low German (Section 5.3).

5.1. Language Statistics in Germany

In Germany, there is no official census on language. Therefore, there are no official numbers of speakers of German or of speakers of the four officially recognized national minorities (i.e., Danes, Frisians, German Sinti and Roma, and Sorbs; further information on these can be found in Beyer and Plewnia 2020), or of speakers of the regional language Low German (see Adler and Beyer 2018 for an overview of languages and language policies in Germany).16 This situation changed a little in 2017 when the German microcensus started to ask each household about the predominantly used language.17 The German microcensus is Germany’s most important set of official statistics.18 Unlike a census, it does not cover the entire population but a representative 1% sample of it and it is conducted yearly. Unfortunately, the item on language in the microcensus has many shortcomings (cf. Adler 2018a, 2018b, 2019a, 2019b, 2020). Only one answer is possible (the label “language” is used in the singular in the item), there is no open-response box, the response is restricted to one respondent per household, and the item is positioned within the set of items on citizenship and length of stay. Furthermore, multilingual repertoires cannot be captured by it, although, apparently, multilingual persons are especially targeted by this item (cf. Adler 2018a, 2018b, 2019a, 2019b, 2020). What is more, the list of given answers is very limited, neither including the four recognized minority languages nor the regional language Low German (cf. Adler and Beyer 2018 on language policies in Germany). Therefore, it is impossible for speakers of those languages to give their language as a response. Thus, even though there is now an item on language elicited for official statistics in Germany, it does not produce official numbers of speakers of minority and regional languages in Germany.

The explicit absence of the minority and regional languages in the microcensus item on language is probably due to its apparent purpose (i.e., to measure language as a proxy variable for cultural integration, see Adler 2019a, p. 203f; Adler 2019b, p. 246). Two reasons for not counting these languages and their speakers are also given explicitly by the Federal Ministry of the Interior, namely a historical one, i.e., the persecution of ethnic minorities under the Nazi regime, and a judicial one, namely considerations of international law. On its homepage it states “[a]ccording to the Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, membership of a minority is an individual personal decision and is neither registered, reviewed nor contested by the government authorities” (homepage of the Bundesministerium des Innern, ‘Federal Ministry of the Interior’).19 The protection of the four national minorities in Germany relies on two European treaties: the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (see Section 2 above). The latter also includes the regional language Low German. Due to its status as a regional language, the Low German community holds a special position in this matter, i.e., even though it is not a national minority it holds a similar position in terms of protection and support for its language. Thus, even though the counting of speakers may be problematic for national minorities, as Low German is a regional and not a minority language, the counting of speakers of Low German should not be an issue.

The reservations on counting speakers of minorities can surely be discussed in more general terms. Some aspects may be perceived as being problematic, but there are also benefits, which should outweigh the drawbacks. Counting is a valuable tool for measuring the “health” of a variety, for example (cf. Urla and Burdick 2018, p. 74; see also Duchêne and Humbert 2018). Numbers can be used to “advocate for resources and recognition” (Urla and Burdick 2018, p. 73). When drawing up adequate policies, it is vital to know the current numbers of speakers, who they are, where they live and their special needs as well as whether and how the number of speakers is changing, etc. These data provide valuable information when ascertaining strategies for protecting and supporting the speakers and their languages (which are, after all, core aims of the Charter).20 That is why many language minority communities worldwide choose to count themselves, even demanding that surveys take place regularly. This is the case for the Basque community, for example (cf. Urla 1993; Urla and Burdick 2018).

5.2. Numbers on Low German

Concerning Low German, several surveys have been carried out dedicated to counting speakers and asking other questions related to the use of Low German. The most recent survey on speakers of Low German is the “Northern Germany Survey 2016” (NGS2016, see Section 3). This survey is an update of two studies on Low German carried out by the Institute for Low German (Institut für niederdeutsche Sprache, INS) in 1984 and 2007 (cf. Stellmacher 1987; Möller 2008). The INS is a private association whose goal it is to maintain and promote Low German. Until the end of 2017, it was publicly funded by the federal states of Bremen, Hamburg, Lower Saxony, and Schleswig-Holstein. As of today, the situation of the INS is still uncertain.

According to the NGS2016, 6.2% of the population of Northern Germany speak Low German very well and 9.5% speak it well while 16.7% speak it reasonably well. 25.4% speak only a few words, and 42.2% do not speak it at all (cf. Adler et al. 2018, p. 15).21 This corresponds to approximately 2.5 million speakers of Low German (cf. Goltz and Kleene 2020, p. 174).

Although there is no official count for speakers of Low German, the number of speakers is given in an official governmental publication, namely the latest report on national minorities and regional languages in Germany issued by the Federal Ministry of the Interior (Bundesministerium des Innern 2015, p. 52). The text refers to 2.6 million good and very good speakers of Low German, a number which was extracted from the first of the three surveys on Low German undertaken by the INS (cf. Möller 2008). The publication also gives a number for speakers of Sorbian, but without providing a reference or source. The only other information on numbers concerns the Danes. The report cites members of an association, a political party, and the number of children in childcare provided by a Danish association as well as the number in schools, and then the size of a Danish congregation (cf. Bundesministerium des Innern 2015, p. 17). No current numbers of speakers are mentioned for the other minorities. Thus, even though, officially, these groups should not be counted, there are some numbers in the text. The repeated references to figures indicate that there is, indeed, a need for such numbers, be it just for illustrative purposes.

5.3. Counting Speakers of Low German

Counting the speakers of a language community is anything but trivial. There is counting by observation (e.g., the Basque Street Survey, Altuna and Urla 2013) and by census or language surveys (cf. for example Welsh or Scottish Gaelic in the census surveys concerned).22 The latter typically use interviews or questionnaires (that is, mostly self-reported data), and for these the wording and presentation of the items as well as the wording and presentation of the responses are crucial. Both play a major role in determining which numbers are produced. This subsection discusses in more detail the effects of wording used in items aimed at counting speakers and the difficulties that can arise when evaluating responses. To this end, data are taken from the surveys described in Section 3. The underlying discussion of adequate items on and responses to language is one that is relevant in the context of census surveys worldwide (cf. Adler 2018a, 2018b, 2019a, 2020; Arel 2002; Busch 2016; Humbert et al. 2018; Leeman 2019; as well as Sebba 2019 on Scots).

5.3.1. Items

It is very challenging to formulate an adequate and understandable item for counting varieties that then also elicits what it was intended to. The lexemes selected for the item are essential, principally the verb used to formulate the item and the category used to retrieve the designated subject (cf. Duchêne et al. 2018, 2019; Humbert et al. 2018, see also the recommendations issued by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe 2006, 2015). Concerning categories, for example, it is crucial what label is used to denote the entity to be elicited, i.e., “dialect” or “language”.23

The two national surveys (GS2008 and GS2017) included an item on what dialects are spoken in Germany with the aim of discovering what varieties respondents name and how these are distributed. Different verb phrases were used in the two surveys. In the GS2008, the German modal verb können (i.e., ‘can’ or ‘to be able to do sth.’, ‘to know sth.’, ‘to master sth.’) was used and in the GS2017 the German verb sprechen (‘to speak’). This seems to lead to different results.

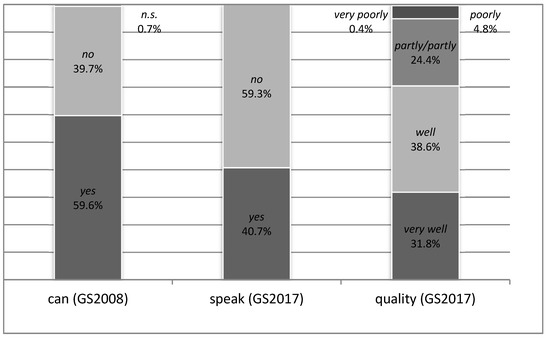

In the GS2008, the item on spoken dialects was worded as follows: “Können Sie einen deutschen Dialekt oder Platt?” (cf. Gärtig et al. 2010, p. 137). It translates as “Do you know a dialect or ‘Platt’?” The German verb sprechen is not actually used in this version of the item. Thus, it is a more abstract and broadly formulated question which allows participants, for example, to name a competence that is no longer active (cf. Adler and Plewnia 2020, p. 18). The question in the GS2017 does make use of the specific verb sprechen: “Sprechen Sie einen deutschen Dialekt?”, translated as “Do you speak a German dialect?”. This item is a little more specific; it also relates more closely to the present moment in time. The possible answers for both questions are “yes” and “no”. The results are displayed in Figure 10 below.

Figure 10.

Results of the items on dialect (GS2008, GS2017).

The proportion of positive answers in the GS2008 is higher than in the GS2017: In the GS2008, 59.6% of the respondents answered affirmatively as opposed to 40.7% in the GS2017. The latter were then asked an additional question on how well they speak this dialect (see “quality (GS2017)” in Figure 10).24 Just over two thirds said that they speak their dialect “very well” (31.8%) or “well” (38.6%), another quarter “partly/partly”, and only 5.2% admitted that they speak this dialect “poorly” or “very poorly”. The distribution of the answers (i.e., an absolute majority describing that they spoke the dialect “well” or “very well”) indicates that those who said yes to the item on general dialect proficiency had an active and rather good proficiency in mind when responding to it. Thus, an item using the verb sprechen (‘speak’) may elicit a lower total number overall, but this group of participants then seems to have a predominantly active competence in the dialect.

The labels employed in the item are also crucial, the question being whether participants are asked about dialects or languages. To judge how lay people define the labels “dialect” and “language”, one can have a look at the responses given when asked to name their dialect or their language. Both nationwide surveys, i.e., GS2008 and GS2017, included items to elicit the dialects of the respondents as well as their languages (although different kinds of questions were used). Moreover, in both surveys, respondents were asked to name dialects and languages they liked or disliked.25 The responses to these items can be analyzed in relation to the categories of the appellations respondents gave as an answer, i.e., what they usually called “dialects” and what “languages” (for more information on so-called named languages, see Horner and Bradley 2019; Otheguy et al. 2015).

When the respondents were asked to name their dialect in the GS2017, virtually all of the respondents indeed named varieties that are usually categorized as dialects or regional varieties (cf. Adler and Silveira 2020; Adler et al. forthcoming). Only a few named varieties that are usually classified as languages, and a few other respondents named German with a special kind of accent. It seems that for lay persons it is quite straightforward to fit Low German into this contextual frame, as numerous responses can be categorized as such (see Section 5.3.2 below for a further description of the actual responses concerning Low German). The corresponding item in GS2008 and the items on liked and disliked dialects in GS2008 and GS2017 produce answers that show the same distribution concerning the classification of their status.

In the corresponding items on liked and disliked languages, in the GS2017 respondents mainly named varieties that are usually classified as languages but some respondents also named regional varieties of German, such as Bavarian, Saxon and a very small number of other regional varieties (cf. Adler 2019b, p. 237f.). When the respondents were asked to name their first language (actually, the label “mother tongue” was used as it is more common in everyday German),26 the respondents mainly named varieties that can be generally categorized as languages. There were only a few answers that can be classified as dialects. Low German is mentioned only very rarely. In the GS2017, the vast majority indicated German as their mother tongue (see Adler 2019a, p. 213ff), with only one person also mentioning Low German as their mother tongue. In the GS2008, not a single person took part in the survey who stated that Low German was their mother tongue. Similarly, Low German was hardly ever mentioned as a second language (in the GS2017 there is one mention and in the GS2008 two). Even in the NGS2016, which is restricted to the Northern German region, the vast majority gave German as their mother tongue. In this Northern sample a small number, i.e., 56 respondents (3.4%), named Low German as their mother tongue, but of these, 19 gave both German and Low German as their mother tongue. This reflects what is assumed of the asymmetric distribution of Low German and Standard German in Northern Germany with Standard German being spoken by virtually everyone and as a default and Low German being used only for specific purposes.

The responses to these items indicate that the categorization of a variety as a dialect or language is perhaps not entirely clear to lay persons. While most of the answers fit the framework of the items, there are also some responses that do not. Maybe, as already indicated in the first two sections, this could be due to the unclear binary taxonomy of dialect and language. Another possible explanation could be that this taxonomy is not important or of value for most situations in the everyday life of lay persons. Usually for example, one does not need to put a name on the variety one speaks, i.e., to classify it (cf. Otheguy et al. 2015). However, as far as Low German is concerned, its categorization as a dialect seems to trigger the greatest response. In contrast, items on language do not, in general, elicit Low German, although there were a few such statements. Accordingly, only some respondents identified with Low German as their mother tongue, and this only in the NGS2016.

5.3.2. Responses

The wording of responses matters as well. This holds when designing the possible options for selected-response items (cf. the language question in the German microcensus in Section 5.1 above); and this also holds when analyzing the responses given to an open-ended item. In the GS2017, respondents who said they spoke a dialect were then asked to name this dialect. The item is in open-ended format; thus the respondents could give more or less any answer they saw fit. This format comes with many advantages, but it also has some disadvantages (cf. Plewnia and Rothe 2012, pp. 27–33). Using this format can elicit how speakers label their variety, for example. A disadvantage, though, is that such open answers are very complex to process (cf. Cuonz 2014). Usually, the answers are very varied and need to be edited before further analysis. Concerning the item at hand, this design allows for a detailed insight into how speakers of regional varieties name their varieties. In this paper, the responses relating to Northern Germany are of special interest. This item was not used in the NGS2016 as it was assumed that there would mainly be speakers of the varieties from the north of Germany.

The first difficulty regarding the editing of answers that can be identified as varieties from Northern Germany is to ascertain which variety respondents actually mean, that is, whether they intend to name Low German or rather a regionally accented variety of Standard German, i.e., Norddeutsch (see Section 2.3 above). In the nationwide GS2017, a total of 219 respondents gave answers that can be identified as regional varieties from Northern Germany. Among these answers, there are 134 that can be attributed to the category Low German. Another 84 entries cannot be attributed to the category Low German but rather to the category North German (Norddeutsch). The label used most often to designate Low German is Plattdeutsch. The results confirm what is generally assumed for the competition between the terms Niederdeutsch, Plattdeutsch, and Platt (see Section 2.2 above): Plattdeutsch is the label speakers of Low German typically use to refer to their language: 79% of the respondents who could be assigned to the category Low German used the label Plattdeutsch (one respondent used a regional variety in spelling: Plattdütsch). The second most frequent answer, the label Platt, was far behind at 15%. Otherwise, there were only five answers with a combination of a place name and Platt as well as the more technical term Niederdeutsch.

Regarding the term Platt, there is also the difficulty of its ambiguity (see Section 2.2 above). It could designate a Low German variety but also a variety from the West Middle German region. In the editing process, such responses were cross-checked using data on the place of residence, place of birth, and parents’ dialects. Thus, Platt responses that could be categorized as not designating Low German (but, for example, rather West Middle German, i.e., varieties from Hesse) were not counted as Low German Platt. Instead they were assigned to the appropriate category.

The responses in the GS2017 to the item on dialects in relation to varieties from the north of Germany reveal that naming a regional dialect is not that easy in at least two respects: first, the variety of labels (i.e., Niederdeutsch, Plattdeutsch, Platt, or even other labels) and second, what one defines as a regional dialect (or language) in Northern Germany (i.e., Niederdeutsch vs. Norddeutsch). These two aspects also make the analysis of answers challenging, to say the least.

6. Discussion: Counting Using the Categories of “Language” or “Dialect”

As the title of this article suggests, the categorization of a variety as either a language or a dialect is crucial, especially in the context of formulating items and analyzing the responses in surveys designed to count the number of speakers of a particular variety. Thus, language attitudes and language statistics are strongly intertwined. This is particularly true for Low German. While the focus of this paper lies on Low German, the basic issues are not restricted to this particular variety. To name just two other examples: classification, self-identification, and counting are also of some importance for Luxembourgish and Scots.

The status of Luxembourgish might still be contested even though, officially, this should not be the case as it is one of the official languages of Luxembourg and has been included in the country’s census for counting purposes since 2011 (cf. Fehlen and Heinz 2016; Wille et al. 2014, p. 358ff). The past and current situation of Scots bears many similarities to Low German. Both were once a standard language in their own right, and later demoted to a dialect. Nowadays, Scots is not a well-defined variety (i.e., is it a language or a dialect? Or, according to the terminology provided by Kloss 1967, see Section 2.1, a near-dialectalized Abstandsprache; for more information on Scots, see Millar 2018). Nonetheless, the Scottish census of 2011 had an item on Scots for the first time. Even in advance of the 2011 census, there was plenty of discussion about this item, as well as about the ones on English and Scottish Gaelic, as the design of the language items was considered to be very problematic. In the end, while the elicited number of speakers of Scots may be rather unreliable, the census nonetheless increased general awareness of Scots (a detailed description of this issue can be found in Sebba 2019).

The current situation of Low German is special for a number of reasons. First, the perception of its current status is unclear (see Section 2.1): while historically it was a language, by the mid-20th century it had been devalued and was mostly perceived of as a dialect. Nowadays, and especially due to the revaluation caused most notably by the European Charter, the current perception of the status of Low German is undecided but tending towards it being a language—as it is now officially. Then, there is the issue of terminological diversity concerning Low German (see Section 2.2). There are essentially three labels for Low German in German: Niederdeutsch, Plattdeutsch and Platt. The first is mainly used as a technical term in linguistics and in official texts, the second is the name the speakers use themselves, and the third is a variant of the second. The latter is, however, also used as a name for dialects in the West Middle German region of Germany. This makes the term ambiguous. Finally, there is another variety that adds to the kind of diglossic situation in Northern Germany, a regionally accented variety of Standard German called Norddeutsch (see Section 2.3).

The speakers and their attitudes lie at the heart of how a variety is used and attitudes have an impact on the counting of a variety. That is, when someone is asked whether or not they speak a certain language, their answer is surely influenced by how the question is worded, including the categorizing label used, and also by the speakers’ attitudes. Presumably, only people who consider their variety a language will name it when asked in a census, for example, what language they use at home. Thus, the counting of a variety, or rather the speakers of a variety, is influenced by attitudes towards this variety. The third and fourth sections shed light on the two issues related to this intermingling: current attitudes towards Low German (Section 4) and language statistics in Germany with a special focus on Low German (Section 5).

The survey data on language attitudes showed that there is currently no clear-cut consensus as to the status of Low German. This unclear evaluation, with a majority going for dialect status, might reflect developments of Low German in the recent past: its devaluation in the mid-20th century and its revaluation by the European Charter by the end of the 20th century. People attributing Low German with language status are especially those who speak Low German, who mainly live in the north-western part of the region and who have more positive attitudes towards Low German. The evaluations of Low German on the AToL scale displayed a pattern typical for dialects but on the value dimension, the judgements of people who consider Low German a language were more similar to those for Standard German. Overall, the value items are judged higher not only by those who consider Low German a language but also by those who have higher proficiency in Low German. This analysis pointed to clear connections between positive attitudes towards Low German, higher evaluations of Low German, higher proficiency in Low German, and considering it to be a language. Thus, the language Low German evokes other attitudes and evaluations (higher values, for example) than the dialect Low German does. From this it may be assumed that the wording of items for counting purposes (especially regarding the use of the labels dialect and language) and the actual attitudes of the speakers will have an impact on the results.

The next section explained why there are no official statistics on minority and regional languages in Germany. The German microcensus has asked about language since 2017, but Low German was not included on the list. While there may be legitimate reasons for this, the fact of not asking about these languages sends out a message as well. Official statistics do not only have the task of counting; they always represent positions and ideologies too. Only the entities counted and later published are visible. Therefore, whether an entity is counted or not definitely has an impact, and may also be interpreted as a certain evaluation of its status. Accordingly, as Low German is not counted, it is invisible in the results. This certainly does not increase its status as a language and its prestige (for Scots it was the other way round: as an item on Scots was included in the census, this had a great impact on the perception of Scots; cf. Sebba 2019).

There is information about the numbers of speakers of Low German though, produced and published by academic institutions. Counting is not the sole aim of these academic surveys; another lies in the methodology, i.e., how to count and whether different methods of counting bring about different results. Section 5.3.1 and Section 5.3.2 on items and responses show how tricky the wording of the former and the analysis of the latter can be. Using taxonomic labels such as “dialect” and “language” nudges participants in a certain direction when responding. For Low German, this means that speakers are more likely to think of it, i.e., to activate the concept of Low German in their minds, when the label “dialect” is used. The results on “mother tongues” in the NGS2016 indicate that this might not be changing much: even in the home region of Low German, only a few respondents classified their variety readily as their mother tongue. The variety and ambiguity of labels used to denote Low German and Northern German varieties make things even more complicated (i.e., Niederdeutsch, Plattdeutsch, Platt, Norddeutsch). This makes the analysis of answers where respondents are free to name any appellations they want relatively challenging and perhaps prone to errors. It also makes the wording of selected-response items on Low German very challenging as adequate and intelligible labels need to be chosen carefully.

Altogether, even if had been possible to name Low German in the German microcensus item on language, it is more than questionable whether speakers of Low German would have chosen it. Their choice would have certainly been influenced by the way the item and responses were worded and designed. This leads us back to the title of this paper, which emphasizes the significance of classifying a variety as a language or a dialect for items and responses in surveys designed to count the number of speakers of a variety. According to our data, it seems that most lay persons still identify Low German as a dialect. Therefore, when using the frame of “dialect”, Low German will quite certainly be activated, and speakers of it would name it when asked about dialects. When using the frame of “language”, in contrast, this is not so certain (as those recognizing it as a language tended to be proficient speakers of it—but not all proficient speakers do so). Thus, either way—just as Kloss (1967) predicted—in view of the uncertainty among lay persons concerning the linguistic classification of Low German, counting might still be quite problematic.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache (IDS).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Parts of the data are available through Research Data Center SOEP (https://www.diw.de/en/diw_01.c.678568.en/research_data_center_soep.html, accessed on 20 January 2020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AdA (Elspaß, Stephan, and Robert Möller). 2003. Atlas zur deutschen Alltagssprache (AdA). Available online: www.atlas-alltagssprache.de (accessed on 4 December 2020).

- Adler, Astrid. 2018a. Die Frage Zur Sprache Der Bevölkerung im Deutschen Mikrozensus 2017. Working Paper. Mannheim: Institut für Deutsche Sprache. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid. 2018b. Germany’s Micro Census 2017: The Return of the Language Question. Working Paper. Mannheim: Institut für Deutsche Sprache. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid. 2019a. Sprachstatistik in Deutschland. Deutsche Sprache 3: 197–219. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid. 2019b. Language discrimination in Germany: when evaluation influences objective counting. Journal of Language and Discrimination 3: 232–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, Astrid. 2020. Counting languages: How to do it and what to avoid. A German perspective. In Language Inequality in Education, Law and Citizenship. Edited by Hui (Annette) Zhao and Nicola McLelland Leanne Henderson. Special issue, Language, Society and Policy. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, Astrid, and Rahel Beyer. 2018. Languages and language politics in Germany/Sprachen und Sprachpolitik in Deutschland. In National Language Institutions and National Languages. Contributions to the EFNIL Conference 2017 in Deutschland. Edited by Gerhard Stickel. Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Science, pp. 221–42. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid, and Albrecht Plewnia. 2018. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der quantitativen Spracheinstellungsforschung. In Variation—Normen—Identitäten. Edited by Alexandra N. Lenz and Albrecht Plewnia. Berlin and Boston: de Gruyter, pp. 63–98. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid, and Albrecht Plewnia. 2019. Die Macht der großen Zahlen. Aktuelle Spracheinstellungen in Deutschland. In Neues Vom Heutigen Deutsch. Empirisch—Methodisch—Theoretisch. Jahrbuch des Instituts Für Deutsche Sprache 2018. Edited by Ludwig M. Eichinger and Albrecht Plewnia. Berlin and Boston: de Gruyter, pp. 141–62. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid, and Albrecht Plewnia. 2020. Aktuelle Bewertungen regionaler Varietäten des Deutschen. Erste Ergebnisse der Deutschland-Erhebung 2017. In Regiolekte. Objektive Sprachdaten und subjektive Sprachwahrnehmung. Edited by Markus Hundt, Andrea Kleene, Albrecht Plewnia and Verena Sauer. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid, and Maria Ribeiro Silveira. 2020. Spracheinstellungen in Deutschland—Was die Menschen in Deutschland über Sprache denken. Sprachreport 4: 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid, Christiane Ehlers, Reinhard Goltz, Andrea Kleene, and Albrecht Plewnia. 2016. Status und Gebrauch des Niederdeutschen 2016. Erste Ergebnisse Einer Repräsentativen Erhebung. Mannheim: Institut für Deutsche Sprache. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid, Christiane Ehlers, Reinhard Goltz, Andrea Kleene, and Albrecht Plewnia. 2018. The Current Status and Use of Low German. Initial Results of a Representative Survey. Translated by Helen Heaney. Mannheim: Institut Für Deutsche Sprache. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Astrid, Albrecht Plewnia, and Maria Ribeiro Silveira. Forthcoming. Dialekte in Deutschland. Mannheim: Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache.

- Altuna, Olatz, and Jacqueline Urla. 2013. The Basque street survey: Two decades of assessing language use in public spaces. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 224: 209–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arel, Dominique. 2002. Language questions in censuses: backward or forward-looking? In Census and Identity. The Politics of Race Ethnicity and Language in National Censuses. Edited by David I. Kertzer and Dominique Arel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 92–120. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Birte. 2010. Niederdeutschdiskurse. Spracheinstellungen Im Kontext von Laien, Printmedien und Politik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Birte. 2019. Wie sagt man hier Bewertungen von Regionalsprache, Dialekt und Standard im Spannungsfeld von regionaler Identität und sozialer Distinktion. In Handbuch Sprache im Urteil der Öffentlichkeit. Edited by Gerd Antos, Thomas Niehr and Jürgen Spitzmüller. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter, pp. 333–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Colin. 1992. Attitudes and Language. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, Stephen, and Patrick Stevenson. 1998. Variation Im Deutschen: Soziolinguistische Perspektiven. Übers. aus dem Engl. Von Konstanze Gebel. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, Ian. 2019. Language attitudes. In Language Contact: An International Handbook. Edited by Jeroen Darquennes, Joe Salmons and Wim Vandenbussche. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, (=Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft, Band 45.1). vol. 1, pp. 234–45. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Rahel, and Albrecht Plewnia, eds. 2020. Handbuch der Sprachminderheiten in Deutschland. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer, Rahel, and Albrecht Plewnia. 2021. Über Grenzen. Deutschsprachige Minderheiten in Europa. In Deutsch in Europa. Sprachpolitisch, Grammatisch, Methodisch. Jahrbuch des Instituts für Deutsche Sprache 2019. Edited by Henning Lobin, Andreas Witt and Angelika Wöllstein. Berlin and Boston: de Gruyter, pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, Bettina M., and Gerd Antos. 2019. ‘Öffentlichkeit’—‘Laien’—‘Experten’: Strukturwandel von ‘Laien’ und‚ Experten‘ in Diskursen über ‘Sprache’. In Handbuch Sprache Im Urteil Der Öffentlichkeit. Edited by Gerd Antos, Thomas Niehr and Jürgen Spitzmüller. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 54–82. [Google Scholar]

- Boysen, Sigrid, Jutta Engbers, Peter Hilpold, Marco Körfgen, Christine Langenfeld, Detlev B. Rein, Dagmar Richter, and Klaus Rier. 2011. Europäische Charta der Regional-Oder Minderheitensprachen. Handkommentar. Zürich and St. Gallen: Dike Verlag. [Google Scholar]