Ideas Buenas o Buenas Ideas: Phonological, Semantic, and Frequency Effects on Variable Adjective Ordering in Rioplatense Spanish

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Default pre-nominal position (English) | Default post-nominal position (Spanish) |

| (1) A serious problem | (2) Un problema grave |

| (3) | Me | gusta | mucho | la | comida | argentina. (post-position) |

| me | like.3SG | a lot | DET | food | Argentinian | |

| ‘I like Argentinian food a lot.’ | ||||||

| (4) | *Me | gusta | mucho | la | argentina | comida. (pre-position) |

| me | like.3SG | a lot | DET | Argentinian | food | |

| (‘I like Argentinian food a lot.’) | ||||||

| (5) | Un problema grave (post-position, restrictive reference: a problem that is serious) |

| (6) | Un grave problema (pre-position, non-restrictive reference: a problem, which by the way is serious) |

| ‘a serious problem’ |

2. The Research Context

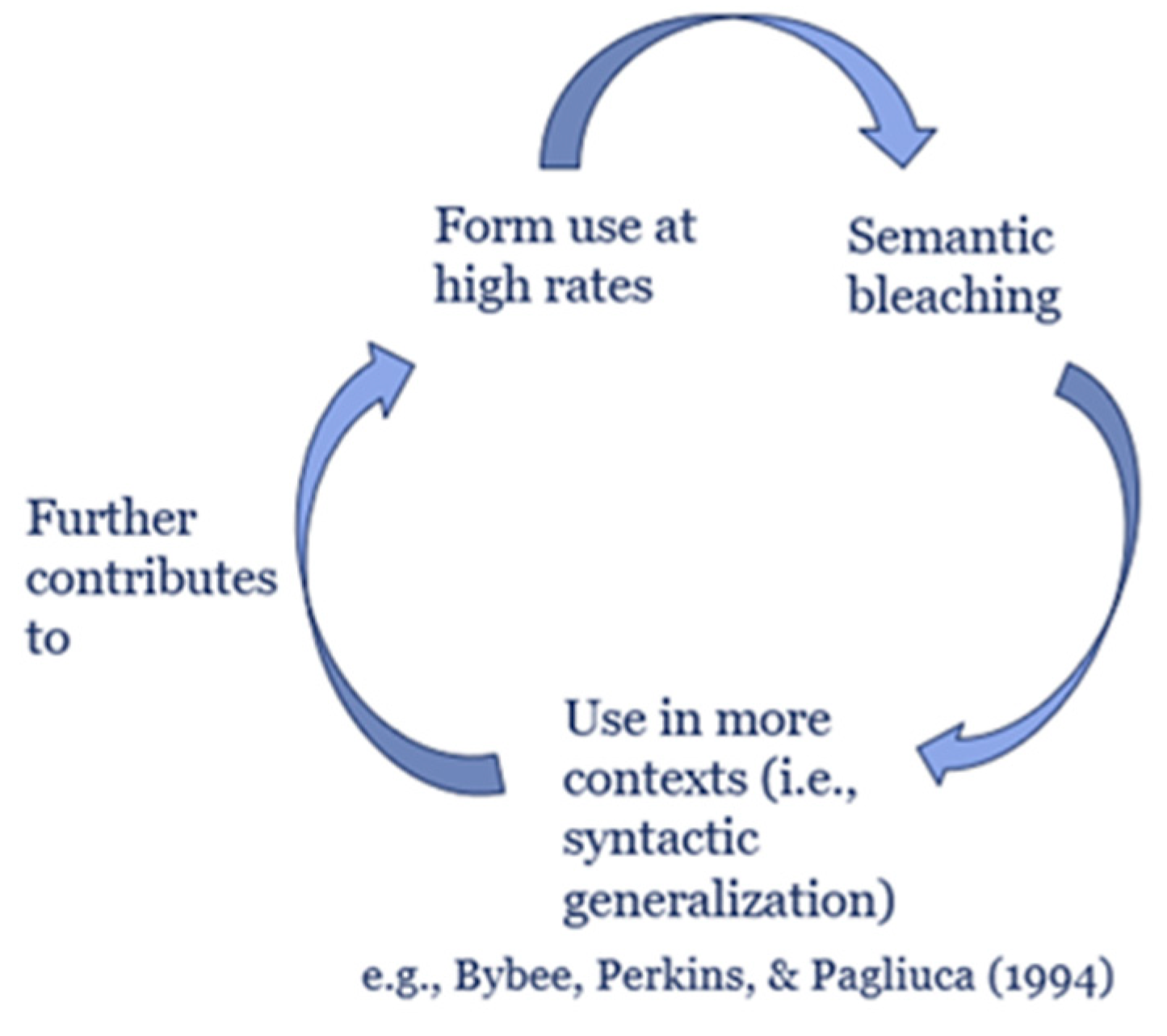

2.1. Usage-Based Approaches and Lexical Frequency

2.2. Adjective Position in Spanish

| (7) | Debemos | ayudar | a | los | hambrientos | niños. | [+specific] |

| have.1PL | to help | prep | DET | hungry | children | ||

| ‘We have to help the hungry children.’ | |||||||

| (8) | Debemos | ayudar | a | los | niños | hambrientos. | [±specific] |

| have.1PL | to help | prep | DET | children | hungry | ||

| ‘We have to help the children, who are hungry.’ | |||||||

| (9) | Susana | prefirió | la | versión | original. |

| Susana | prefer.PRET.3SG | DEF.ART | version | original | |

| ‘Susana preferred the original version’. | |||||

2.3. Remaining Gaps in the Study of Variable Adjective Position

3. Materials and Methods

- What is the frequency of selection of pre-posed adjectives on a written contextualized preference task in rioplatense Spanish?

- What linguistic and extralinguistic variables predict pre-position? Is pre-position favored by shorter adjectives, high-frequency adjectives, and a particular semantic class? Do a particular age group and gender favor pre-position?

3.1. Participants

3.2. Tasks, Variables, and Hypotheses

| (10) | Hernán: A mí me impresiona el paso del tiempo. ¡Hace 20 años de esto! Pero como si hubiera sido ayer. (‘Hernán: I’m impressed by the passing of time. It’s been 20 years now! But it feels as if it were yesterday.’) ___________________________________________. |

| |

| (‘Anyway, all those moments seem like fresh experiences.’) | |

| |

| (‘Both are equally acceptable’.) |

4. Results

4.1. Rates of Selection

4.2. Independent Variables

4.3. Individual Adjective Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Answers to Research Questions

5.2. Interpreting the Roles of Lexical Frequency, Semantics, and Syllable Weight

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Rioplatense Spanish | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log Odds | N | % (of Pre-Position) | Factor Weight | |

| Individual Adjective (p = 3.63 × 10−159) | ||||

| Grandes ‘big’ (shape/space, higher-freq.) | 1.669 | 345 | 69.6 | 0.841 |

| Buenos ‘good’ (evaluation, higher-freq.) | 1.517 | 331 | 66.5 | 0.820 |

| Nuevos ‘new’ (temporal, higher-freq.) | 1.250 | 340 | 61.2 | 0.777 |

| Rudos ‘tough’ (evaluation, lower-freq.) | −0.369 | 345 | 28.1 | 0.409 |

| Frescos ‘fresh’ (temporal, lower-freq.) | −1.542 | 373 | 12.3 | 0.176 |

| Llanos ‘flat’ (shape/space, lower-freq.) | −2.524 | 374 | 5.3 | 0.074 |

| Range 77 | ||||

| Syllable-Weight Difference (Adjective Relative to Noun) (p = 5.18 × 10−23) | ||||

| −2 syllables | 0.719 | 526 | 49.8 | 0.672 |

| 0 syllables | 0.190 | 529 | 41.8 | 0.547 |

| −1 syllable | 0.043 | 540 | 40.6 | 0.511 |

| +1 syllable | −0.952 | 513 | 25.1 | 0.278 |

| Range 39 | ||||

| Age Group (p = 0.0363) | ||||

| 55+ | 0.329 | 464 | 45.7 | 0.582 |

| 35–54 | −0.024 | 891 | 39.7 | 0.494 |

| 18–34 | −0.305 | 753 | 35.2 | 0.424 |

| Range 16 | ||||

| Gender (p = 0.932) | ||||

| Women | 0.009 | 1548 | 39.5 | [0.502] |

| Men | −0.009 | 560 | 39.3 | [0.498] |

| Total N = 2108 | Overall rate 39.4% pre-position | |||

| Participant (random) | ||||

| Random St. Dev. | 0.674 | |||

| Fixed R2 = 0.449, Random R2 = 0.067, Total R2 = 0.516; log likelihood −988.836 | ||||

References

- Aaron, Jessi E. 2010. Pushing the envelope: Looking beyond the variable context. Language Variation and Change 22: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, Tainara, and Scott A. Schwenter. 2018. Variable negative concord in Brazilian Portuguese: Acceptability and frequency. In Contemporary Trends in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics: Selected Papers from the Hispanic Linguistic Symposium 2015. Edited by Jonathan E. MacDonald. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Jennifer E., Anthony Losongco, Thomas Wasow, and Ryan J. L. Ginstrom. 2000. Heaviness vs. newness: The effects of structural complexity and discourse status on constituent ordering. Language 76: 28–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronoff, Mark. 2013. Varieties of Morphological Defaults and Exceptions. ReVEL 7. Available online: www.revel.inf.br/eng (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Bayley, Robert, Kristen Greer, and Cory Holland. 2017. Lexical frequency and morphosyntactic variation: Evidence from U.S. Spanish. Spanish in Context 14: 413–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Andrés. 1981. Gramática de la Lengua Castellana Destinada al uso de los Americanos. [Grammar of the Spanish Language for Americans]. Edited by R. Trujillo de crítica. Tenerife: Santa Cruz de Tenerife. First published 1847. [Google Scholar]

- Bosque, Ignacio. 1996. On specificity and adjective position. In Perspectives on Spanish Linguistics. Edited by Javier Gutiérrez Rexach and Luis Silva Villar. Los Angeles: UCLA, vol. 1, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bosque, Ignacio. 2001. Adjective position and the interpretation of indefinites. In Current Issues in Spanish Syntax and Semantics. Edited by Javier Gutiérrez Rexach and Luis Silva Villar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Esther L. 2013. Word classes in phonological variation: Conditioning factors or epiphenomena? In Selected Proceedings of the 15th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Chad Howe, Sarah Blackwell and Margaret Lubbers Quesada. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 179–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Esther L., and William D. Raymond. 2012. How discourse context shapes the lexicon: Explaining the distribution of Spanish f-/h-words. Diachronica 92: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, Leone, Elena Lieven, and Anna L. Theakston. 2018. The effects of animacy and syntax on priming: A developmental study. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2002. Word frequency and context of use in the lexical diffusion of phonetically conditioned sound change. Language Variation and Change 14: 261–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2006. From usage to grammar: The mind’s response to repetition. Language 82: 711–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2007. Regular morphology and the lexicon. In Frequency of Use and the Organization of Language. Edited by Joan L. Bybee. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 167–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 2010. Language, Usage and Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L. 2017. Grammatical and lexical factors in sound change. Language Variation and Change 29: 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, Joan L., Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in the Languages of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno-Pulido, Alberto. 2012. Variability in Spanish adjectival position: A corpus analysis. Sintagma 24: 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Colantoni, Laura, and Celeste Rodríguez Louro, eds. 2013. Perspectivas Teóricas y Experimentales Sobre el Español de la Argentina. [Theoretical and experimental perspectives on the study of Argentinian Spanish]. Madrid: Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Östen. 1985. Tense and Aspect Systems. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Dam, Lotte. 2018. The semantics of the Spanish adjective positions: A matter of focus. Research in Language 16: 223–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davies, Mark. 2016. Corpus del Español: Web/Dialects. Available online: https://www.corpusdelespanol.org/web-dial/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Davies, Mark. 2018. Corpus del Español: NOW. Available online: https://www.corpusdelespanol.org/now/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Davies, Mark, and Kathy Hayward Davies. 2018. A Frequency Dictionary of Spanish: Core Vocabulary for Learners, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Delbecque, Nicole. 1990. Word order as a reflection of alternate conceptual construals in French and Spanish: Differences and similarities in adjective position. Cognitive Linguistics 1: 349–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demonte, Violeta. 1999. El adjetivo. Clases y usos. La posición del adjetivo en el sintagma nominal [Adjective position in the noun phrase]. In Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. Edited by Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte. Madrid: Espasa, pp. 129–215. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel, and Sara L. Zahler. 2018. Testing formal Accounts of variation: A sociolinguistic analysis of word order in negative word + más constructions. Hispania 101: 605–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, Amanda, and Aarnes Gudmestad. 2014. Your participation is greatly/highly appreciated: Amplifier collocations in L2 English. Canadian Modern Language Review 70: 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erker, Daniel, and Gregory R. Guy. 2012. The role of lexical frequency in syntactic variability: Variable subject personal pronoun expression in Spanish. Language 88: 526–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalona Torres, Juan. 2020. Degree, time and focus: A historical tale of a poco. In Current Theoretical and Applied Perspectives on Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. Edited by Diego Pascual y Cabo and Idoia Elola. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 133–51. [Google Scholar]

- File-Muriel, Richard J. 2006. Spanish adjective position: Differences between written and spoken discourse. In Functional Approaches to Spanish Syntax: Lexical Semantics, Discourse, and Transitivity. Edited by J. Clancy Clements and Jiyoung Yoon. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan, pp. 203–18. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, Kimberly L. 2010. Beyond “naturalistic”: On the role of task characteristics and the importance of multiple elicitation methods. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 3: 501–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Adele E. 2013. Constructionist approaches. In The Oxford Handbook of Construction Grammar. Edited by Thomas Hoffmann and Graeme Trousdale. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, John A. 1994. A Performance Theory of Order and Constituency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Jennifer. 2001. Lexical frequency in morphology: Is everything relative? Linguistics 39: 1041–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, Mark R. 2014. Adjective placement in three modes of Spanish: The role of syllabic weight in novels, presidential speeches, and spontaneous speech. IULC Working Papers 14: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J. 1991. On some principles of grammaticalization. In Approaches to Grammaticalization. Edited by Elisabeth C. Traugott and Bernd Heine. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J., and Elizabeth C. Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huback, Ana Paula. 2011. Irregular plurals in Brazilian Portuguese: An exemplar model approach. Language Variation and Change 23: 245–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, Daniel. 2005. Adjective position, specificity, and information structure in Spanish. Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft der Univiersität Konstanz 119: 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Daniel E. 2009. Getting off the Goldvarb standard: Introducing Rbrul for mixed-effects variable rule analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judy, Tiffany. 2018. The syntax-semantics of adjectival distribution in adult Polish-Spanish childhood bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40: 367–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, Matthew, and Kimberly L. Geeslin. 2018. Exploring lexical effects in second language interpretation: The case of mood in Spanish adverbial clauses. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 40: 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, Matthew, and Kimberly L. Geeslin. 2020. Sociolinguistic competence and interpreting variable structures in a second language: A study of the copula contrast in native and second-language Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 42: 775–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William. 2001. Principles of Linguistic Change, Vol. 2: Social Factors. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Hanjung. 2011. Gradients in Korean case ellipsis: An experimental investigation. Lingua 121: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xiaoshi, and Robert Bayley. 2018. Lexical frequency and syntactic variation: Subject pronoun use in Mandarin Chinese. Asia-Pacific Language Variation 4: 135–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linford, Bret, and Naomi L. Shin. 2013. Lexical frequency effects on L2 Spanish subject pronoun expression. In Selected Proceedings of the 16th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Jennifer Cabrelli Amaro, Gillian Lord, Ana de Prada Pérez and Jessi E. Aaron. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- McColl Miller, Robert. 2007. Trask’s Historical Linguistics, 2nd ed. London: Hodder. [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Rivera, Antonio. 1999. Variación fonológica y estilística en el español de Puerto Rico [Phonological and stylistic variation in the Spanish of Puerto Rico]. Hispania 82: 529–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, Marcial. 1980. The semantics of adjective position in Spanish. Selecta 9: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk, Randolph. 1991. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London and New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. 1985. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London and New York: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, Marathon M. 1956. A Textbook of Modern Spanish. New York: Henry Holt and Company. First published 1894. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española (RAE). 2009. Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. [New grammar of the Spanish language]. Madrid: Espasa Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Salvá, Vicente. 1988. Gramática de la Lengua Castellana 1 (Estudio y Edición de M. Lliteras). Madrid: Arco Libros. First published 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Sankoff, David, and Pierrette Thibault. 1981. Weak complementarity: Tense and aspect in Montreal French. In Syntactic Change. Edited by Brenda Johns and David Strong. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, pp. 206–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenter, Scott A., and Rena Torres Cacoullos. 2008. Defaults and indeterminacy in temporal grammaticalization: The “perfect” road to perfective. Language Variation and Change 20: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, Megan, Bret Linford, and Kimberly L. Geeslin. 2018. Acquisition of sociophonetic variation: Intervocalic/d/reduction in native and nonnative Spanish. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada 31: 309–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Francesca Filiaci. 2006. Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research 22: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallerman, Maggie. 2015. Understanding Syntax, 4th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Terker, Andrew. 1985. On Spanish adjective position. Hispania 68: 502–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticio, M. Emma. 2010. Locality Domains in the Spanish Determiner Phrase. London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, Michael. 1998. Introduction: A cognitive-functional perspective on language structure. In The New Psychology of Language: Cognitive and Functional Approaches to Language Structure (vol. 1). Edited by Michael Tomasello. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. vii–xxxi. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Cacoullos, Rena. 2011. Variation and grammaticalization. In The Handbook of Hispanic Sociolinguistics. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 148–67. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, James. 2010. Variation in Linguistic Systems. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wasow, Thomas. 1997. Remarks on grammatical weight. Language Variation and Change 9: 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Donald. 1996. Totally awesome English! Modern English Teacher 5: 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmet, Marc. 1980. Anteposition et posposition de l’epithete qualificative em francais contemporain [Pre-position and post-position of the qualitative epithet in modern French]. Travaux de Linguistique 7: 179–201. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Research operationalizing lexical frequency has often used large-scale, external measures (i.e., global frequency, Bybee 2002), although smaller, corpus-internal measures may alternatively be used (i.e., local frequency, Erker and Guy 2012). |

| 2 | When containing a determiner, these phrases may be considered NPs or determiner phrases, depending upon theoretical orientation (see Tallerman 2015, Ch. 4 for discussion). |

| 3 | Informational focus or non-contrastive focus expresses new information without explicitly contrasting it with an element in the discourse. Contrastive focus is the element chosen from a set of mutually known entities to the exclusion of the other elements (Lee 2011). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | One noun was an exception. Líder ‘leader’ carries penultimate stress in the singular but antepenultimate stress in the plural. Nevertheless, buenos líderes patterned with other −1 syllable weight difference forms in our results. |

| 6 | Along with meeting the syllable-difference guidelines above, each noun was chosen so that it would be more frequent or less frequent than the modifying adjective, in the case of the lower- and higher-frequency adjective pairings, respectively. The most frequent noun used ranked 88 (vidas ‘lives’), with the least frequent ranked noun 4998 on the top 5000 list (jugadas ‘tricks’), along with four unranked nouns (montañas ‘mountains’, traumas ‘traumas’, vivencias ‘experiences’, tropiezos ‘mistakes’). Relative frequency is further considered in Section 5.2. |

| 7 | Rudo reveals lower rates of pre-position in corpora if we focus on the nouns used on our task, as Table 6 will demonstrate. |

| 8 | The full task is in IRIS at https://www.iris-database.org/iris/app/home/detail?id=york%3a938555&ref=search. |

| 9 | Future work may consider additional variables such as social class or educational level, which have received little attention for this structure. Our sample did not permit analysis of these variables, as our participants generally had higher educational levels. |

| 10 | We consider the role of the individual adjective in our second regression. Presenting two different regression models was more illustrative of the roles played by our independent variables and the adjectives therein than displaying only one. The second analysis thus helps reveal patterns that may be absconded by the initial one. |

| 11 | For comparison’s sake, we ran an additional regression that combined “both” with the pre-posed response to determine where pre-position was allowed. The hierarchy of factor groups and constraint rankings within groups were identical to those of Table 4, although age group missed significance (p = 0.101). |

| 12 | The full regression table can be found in Appendix A. Because the values for the other independent variables were nearly identical to those of Table 4, only the new variable (i.e., individual adjective) and the model summary information are presented in Table 5. |

| 13 | Searching only the Web/Dialects corpus for the plurals yielded the same ranking as the combined Web/Dialects and NOW corpora reported in Table 6. |

| 14 | Recall that our +1 category required use of the elative form of the adjective (e.g., grandísimas montañas ‘very big mountains’), since our task otherwise consisted of bi-syllabic plural nouns and adjectives. It is likely that both the greater length and lower frequency of elative forms contributed to the tendency for post-position. Future research that includes longer adjectives (or shorter nouns) will help disambiguate these factors. |

| 15 | An anonymous reviewer inquired whether grandes might invoke different readings as a pre-posed versus post-posed choice, especially with nouns that are more figurative/less concrete. Although pre-position was favored when grandes modified the abstract nouns tropiezos ‘mistakes’ and decepciones ‘disappointments’, these were also its −1 and −2 syllable-difference pairings, which again were favorable contexts for pre-position across the task. Future work will benefit from manipulating figurativeness/concreteness. |

| 16 | Nevertheless, we certainly do not claim that semantic class is unimportant overall in conditioning pre-position, since only some classes participate in this phenomenon. |

| Independent Linguistic Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Semantic Class | Syllable-Weight Difference (ADJ Relative to N) | Adjective Frequency |

| Evaluation: Buenos ‘good’ Rudos ‘tough’ | −2 syllables: e.g., Buenas bibliotecas ‘good libraries’ | Higher (ranked 62–115): Buenos ‘good’ Grandes ‘big’ Nuevos ‘new’ |

| Shape/Space: Grandes ‘big’ Llanos ‘flat’ | −1 syllable: e.g., Nuevos parajes ‘new places’ | Lower (2124–4859): Frescos ‘fresh’ Llanos ‘flat’ Rudos ‘tough’ |

| Temporal: Nuevos ‘new’ Frescos ‘fresh’ | 0 syllables: e.g., Calles llanas ‘flat roads’ | |

| +1 syllable: e.g., Grandísimas montañas ‘very big mountains’ | ||

| Pre-Posed (PL) | Post-Posed (PL) | Total (PL) | Pre-Posed (Lemma) | Post-Posed (Lemma) | Total (Lemma) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADJ | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Grande | 28,691 | 91.7 | 2585 | 8.3 | 31,276 | 100 | 118,878 | 93.3 | 8526 | 6.7 | 127,404 | 100 |

| Nuevo | 45,335 | 88.1 | 6099 | 11.9 | 51,434 | 100 | 123,443 | 89.0 | 15,247 | 11.0 | 138,690 | 100 |

| Bueno | 10,436 | 85.9 | 1717 | 14.1 | 12,153 | 100 | 86,094 | 93.9 | 5639 | 6.2 | 91,733 | 100 |

| Rudo | 29 | 46.8 | 33 | 53.2 | 62 | 100 | 124 | 52.3 | 113 | 47.7 | 237 | 100 |

| Llano | 6 | 9.0 | 61 | 91.0 | 67 | 100 | 82 | 26.4 | 229 | 73.6 | 311 | 100 |

| Fresco | 59 | 7.5 | 733 | 92.6 | 792 | 100 | 201 | 9.2 | 1980 | 90.8 | 2181 | 100 |

| Buenos Aires Group | Pre-Position | Post-Position | Both | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| 100 respondents | 831 | 34.6 | 1277 | 53.2 | 292 | 12.2 | 2400 | 100 |

| 99 non-categorical respondents | 831 | 35.0 | 1277 | 53.7 | 268 | 11.3 | 2376 | 100 |

| 99 non-categorical respondents (“both” response removed) | 831 | 39.4 | 1277 | 60.6 | -- | -- | 2108 | 100 |

| Log Odds | N | % (of Pre-Position) | Factor Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjective Frequency (p = 2.77 × 10−146) | ||||

| Higher (62–115) | 1.392 | 1016 | 65.7 | 0.801 |

| Lower (2124–4859) | −1.392 | 1092 | 14.9 | 0.199 |

| Range 60 | ||||

| Syllable-Weight Difference (Adjective Relative to Noun) (p = 7.54 × 10−23) | ||||

| −2 syllables | 0.695 | 526 | 49.8 | 0.667 |

| 0 syllables | 0.201 | 529 | 41.8 | 0.550 |

| −1 syllable | 0.055 | 540 | 40.6 | 0.514 |

| +1 syllable | −0.951 | 513 | 25.1 | 0.279 |

| Range 39 | ||||

| Semantic Class (p = 4.64 × 10−8) | ||||

| Evaluation | 0.466 | 676 | 46.9 | 0.614 |

| Shape/space | −0.228 | 719 | 36.2 | 0.443 |

| Temporal | −0.238 | 713 | 35.6 | 0.441 |

| Range 17 | ||||

| Age Group (p = 0.0419) | ||||

| 55+ | 0.314 | 464 | 45.7 | 0.578 |

| 35–54 | −0.028 | 891 | 39.7 | 0.493 |

| 18–34 | −0.286 | 753 | 35.2 | 0.429 |

| Range 15 | ||||

| Gender (p = 0.908) | ||||

| Women | 0.011 | 1548 | 39.5 | [0.503] |

| Men | −0.011 | 560 | 39.3 | [0.497] |

| Total N = 2108 | Overall rate 39.4% pre-position | |||

| Participant (random) | ||||

| Random St. Dev. | 0.645 | |||

| Fixed R2 = 0.399, Random R2 = 0.067, Total R2 = 0.466; log likelihood −1017.634 | ||||

| Individual Adjective (p = 3.63 × 10−159) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjective | Semantic Class | Frequency | Log Odds | N | % (of Pre-Position) | Factor Weight |

| Grandes | Shape/Space | Higher (62–115) | 1.669 | 345 | 69.6 | 0.841 |

| Buenos | Evaluation | Higher (62–115) | 1.517 | 331 | 66.5 | 0.820 |

| Nuevos | Temporal | Higher (62–115) | 1.250 | 340 | 61.2 | 0.777 |

| Rudos | Evaluation | Lower (2124–4859) | −0.369 | 345 | 28.1 | 0.409 |

| Frescos | Temporal | Lower (2124–4859) | −1.542 | 373 | 12.3 | 0.176 |

| Llanos | Shape/Space | Lower (2124–4859) | −2.524 | 374 | 5.3 | 0.074 |

| Range 77 | ||||||

| Total N = 2108 | Overall rate 39.4% pre-pos. | |||||

| Participant (random) | ||||||

| Random St. Dev. | 0.674 | |||||

| Fixed R2 = 0.449, Random R2 = 0.067, Total R2 = 0.516; log likelihood −988.836 | ||||||

| Web/Dialects | Web/Dialects, Argentina | Web/Dialects + NOW | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Posed (Lemma) | Post-Posed (Lemma) | Pre-Posed (Lemma) | Post-Posed (Lemma) | Pre-Posed (PL) | Post-Posed (PL) | |||||||

| ADJ Lemma | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Grande | 1792 | 97.7 | 42 | 2.3 | 130 | 98.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 1620 | 98.4 | 27 | 1.6 |

| Bueno | 2505 | 97.5 | 65 | 2.5 | 167 | 97.7 | 4 | 2.3 | 2177 | 96.3 | 84 | 3.7 |

| Nuevo | 425 | 91.4 | 40 | 8.6 | 49 | 89.1 | 6 | 10.9 | 589 | 93.0 | 44 | 7.0 |

| Rudo | 49 | 27.1 | 132 | 72.9 | 6 | 37.5 | 10 | 62.5 | 28 | 24.6 | 86 | 75.4 |

| Fresco | 16 | 10.7 | 133 | 89.3 | 2 | 25.0 | 6 | 75.0 | 12 | 8.3 | 132 | 91.7 |

| Llano | 3 | 0.8 | 388 | 99.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 100.0 | 4 | 2.0 | 199 | 98.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanwit, M.; Terán, V. Ideas Buenas o Buenas Ideas: Phonological, Semantic, and Frequency Effects on Variable Adjective Ordering in Rioplatense Spanish. Languages 2020, 5, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040065

Kanwit M, Terán V. Ideas Buenas o Buenas Ideas: Phonological, Semantic, and Frequency Effects on Variable Adjective Ordering in Rioplatense Spanish. Languages. 2020; 5(4):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040065

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanwit, Matthew, and Virginia Terán. 2020. "Ideas Buenas o Buenas Ideas: Phonological, Semantic, and Frequency Effects on Variable Adjective Ordering in Rioplatense Spanish" Languages 5, no. 4: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040065

APA StyleKanwit, M., & Terán, V. (2020). Ideas Buenas o Buenas Ideas: Phonological, Semantic, and Frequency Effects on Variable Adjective Ordering in Rioplatense Spanish. Languages, 5(4), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040065