Abstract

In his most recent work, Landau suggests that control in impersonal passive constructions is cross-linguistically limited to attitude verbs and argues that this universal restriction offers convincing support for his two-tiered theory of control (TTC) over his earlier “single tier” Agree-based model. This paper further examines sentences involving control and passivization and argues that improved empirical coverage is achieved in this area by a single-tier Agree approach to control, one fundamentally different from Landau’s earlier analysis in its extension to control Reuland’s proposals reducing binding phenomena to Agree.

1. Introduction

It is probably accurate to say that the current standard generative approach to obligatory control (OC) typified by sentences like (1a,b) is the “two-tiered theory of control” (TTC) developed in Landau (2015, forthcoming).

- (1)

- You forgot/managed [PRO to call].

- The bank teller asked/persuaded me [PRO to write down my PIN].

That is, in his most recent work, Landau (2015, forthcoming) rejects his earlier approach to control, which was based on a single process of Agree (cf. Landau 2000, 2003, 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013), in favor of the view that obligatory control involves either just predication (the first “tier” of control) or predication interacting with binding (the second “tier”). In other words, it is these two separate processes that conspire to determine that the reference of PRO must respectively be the subject NP you in (1a) and the matrix object NP me in (1b).

As will be made clear in this section, Landau (2015, pp. 68–75) offers as convincing evidence for his new theory the lack of so-called Visser’s Generalization (VG) effects in impersonal passive control structures involving attitude predicates, i.e., sentences of the type It was agreed to raise taxes. However, the next section of this paper will show that a closer look at these constructions (and others) reveals that they are actually problematic for this approach. Specifically, we will see that Landau’s TTC (a) both overgenerates ungrammatical impersonal passive sentences and undergenerates other grammatical ones, (b) incorrectly precludes non-obligatory control (NOC) in impersonal passives across languages, and (c) offers no account of Visser’s Generalization.

All of these problems will be shown in Section 2 to result from Landau’s primary claim that there are two distinct routes of control. Given this, a novel, “single tier” Agree-based approach to control will be developed in Section 3, one that rejects any of the control-specific notions employed in Landau’s earlier Agree approach, for example, his self-described ad hoc use of a [+/−R] feature. This new analysis will be similar in spirit and technical implementation to Reuland’s (2011) minimalist approach to binding. In particular, it will be assumed with Kratzer (2009); Reuland (2011), and Landau (2015) that PRO is a minimal pronoun, i.e., it enters derivations with all of its ϕ-features unspecified, and, as a consequence of this, must have them valued in some way in order to be interpretable at PF and LF. However, in contrast to Landau (2015), this interpretability will be achieved either by a default process of feature-overwriting, set up within the syntax via Agree (in which case a context of obligatory control obtains), or, barring that, by Last Resort to semantic binding or pragmatic antecedent determination (in which case a reading of non-obligatory control NOC results). Section 4 will show how this analysis accommodates each of the facts introduced in the preceding sections.

Let us begin, then, by considering how Landau (2015) uses certain facts involving impersonal passive constructions to argue against his earlier Agree approach to control and towards one based primarily on predication, at times coupled with binding.

Jenkins (1972) and Visser (1973) were the first to observe that on their usual obligatory object control use, verbs like ask and persuade accept personal passivization (2b), whereas subject control verbs, like promise in (2c), do not (2d). Since Bresnan (1982), this empirical fact has been referred to as “Visser’s Generalization” (VG).1

- (2)

- The bank teller asked/persuaded me [PRO to write down my PIN].

- I was asked/persuaded [PRO to write down my PIN].

- You promised me [PRO to call].

- *I was promised [PRO to call].

Subsequent research on languages like Dutch, French, German, Norwegian, and Swedish by Evers (1975); Manzini (1983); Koster (1987); van Urk (2013), and others has established not only that VG holds universally in personal passives like those in (1), but also that it is intriguingly absent in impersonal passives, such as the ones in (3a,b).

- (3)

Landau (2015, pp. 68–75) argues that impersonal passive constructions offer convincing support for his two-tiered theory of control (TTC), according to which antecedent determination in contexts of obligatory control (OC) is not determined by a unique process of Agree, as previously hypothesized in Landau (2000, 2003, 2004, 2007, 2010, 2013), but rather by predication alone (in the case of exhaustive control/non-attitude verbs) or by predication acting in conjunction with binding (in the case of partial control/attitude verbs).2 In the TTC, the role of Agree is simply to transmit uninterpretable morphological phi-features to obligatorily controlled PRO (PROOC) at PF.

More specifically, Landau (2015, p. 71) suggests that impersonal passives are subject to a universal restriction that can be observed by comparing the grammatical examples in (3a,b) above with the ungrammatical ones in (4).

- (4)

- *It was continued/forgotten [PRO to move forward with this project].

As Landau points out, the two sets of examples contrast in the semantic type of the matrix verb. The class of attitude verbs in (3a,b) allows impersonal passivization, while the non-attitudes in (4) disallow it. He next observes that this restriction is unexpected under his earlier “single-tiered” Agree approach to control since both types of examples are analyzed in an identical fashion. The restriction falls out, however, from his new theory, according to which control into the complement clause of non-attitude verbs involves direct predication of the property denoted by the embedded clause of the understood controller, while control into the complement of an attitude verb is “indirect,” involving binding of a pro in the embedded Spec of CP by the controller, coupled with predication of the property denoted by the embedded clause of that pro.

To see this more clearly, consider the structures the TTC associates with these examples, given below in (5a,b). In these examples and elsewhere in the text, IMP is a visual representation of the understood thematic subject of the passive verb.3 That is, as in Landau (2015), no claim is being made here with respect to whether the understood thematic subject is a truly implicit argument (i.e. one discharged only in the lexicon) or is actually syntactically projected as a so-called weak implicit argument, a nominal whose lack of a [D] feature precludes predication, as argued in Landau (2010). As a final clarification, note that indices below and elsewhere simply serve to make intended readings explicit. In line with the Inclusiveness Condition, they have no theoretical status in minimalist theory (MT), in contrast with some earlier versions of generative grammar.

- (5)

- It was IMPi agreed/decided [CP proi [FinP PROi to establish a new nation onnew principles]].

- *It was IMPi continued/forgotten [FinP PROi to move forward with this project].

The grammaticality of (5a) follows from the assumption that control in attitude contexts involves binding, more specifically, binding of pro by IMP, coupled with predicating the property denoted by the embedded FinP of that pro.4 That is, contrasts of the type given below in (6a,c), adapted from Chomsky (1986, pp. 120–21), have established that predication requires a syntactically projected argument associated with a [D] feature since the property denoted by together may be licitly predicated of you (6a) and PRO (6b), but not of the implicit thematic subject of the passive (6c). On the other hand, contrasts like those in (7a,b), due to Williams (1985), show that implicit arguments can serve as binders since IMP can refer to the same individual as he in (7a) and it induces a Principle C violation in (7b) when it refers to John.

- (6)

- It is impossible [for you to visit me together].

- It is impossible [PRO to visit me together].

- *It is impossible [for me to be IMP visited together].

- (7)

- [The IMPx realization that hex was unpopular] upset him.

- *[The IMPx realization that Johnx was unpopular] upset him.

In sum, the implicit argument in (5a) binds pro, which itself serves as the syntactically projected argument of predication of the embedded FinP, producing a grammatical result. In contrast, the complement clause of non-attitude verbs like those in (5b) is assumed to lack an “enriched” logophoric layer, i.e., to have no pro in the embedded CP. Therefore, no bindee is available to serve as a referential link between IMP and PRO. This leaves direct predication as the only possible route of control, which results in ungrammaticality since the only NP available to serve as the subject of predication is expletive it and contrasts like those in (8a,b)–(9a,b), respectively observed in Safir (1985, pp. 33–38) and Jaeggli and Safir (1989, p. 19), establish that PRO is non-expletive not only in sentential subject position (a context of non-obligatory control), but also in the subject position of an infinitival complement clause (a configuration generally associated with obligatory control).

- (8)

- [Before PRO making a big decision], every option should be considered.

- *[PRO being obvious that Marie won’t be returning], we can leave.

- (9)

- It is possible that it pleases him that Mary is sick.

- *It is possible [PRO to please him that Mary is sick].

We conclude on the basis of the facts introduced thus far that Landau appears to be correct. The constraint on impersonal passivization that he observes in relation to examples like (5a,b) seems to support a TTC.5 In the next section, we will take a much closer look at such data in order to show that a fuller range of facts actually supports a different view, namely, one in which obligatory control is a unified phenomenon that is best captured in terms of standard Agree relations already assumed in MT.

2. Data Involving Control and Passivization That Are Problematic for the TTC

2.1. Visser’s Generalization

Let us begin by noting that the two-tiered theory of control (TTC) presently offers no account of Visser’s Generalization (VG), illustrated above in (2a,d). To see this, consider the structures it associates with the key examples repeated below in (10a,b):

- (10)

- Ik was IMPi asked [CP prok [FinP PROk to write down my PIN]].

- *Ik was IMPi promised [CP proi [FinP PROi to call]].

The verbs promise and ask are both attitude verbs. The TTC would, therefore, associate them with the same syntactic configuration, namely, one in which there is a pro in the embedded clause that could theoretically be bound by either the explicit argument I or the implicit agent of the passive. This correctly predicts the grammaticality of (10a). (The second reading in which the implicit agent serves as the antecedent of PRO is presumably ruled out on semantic grounds.) However, it also incorrectly rules in (10b). That is, semantic considerations correctly preclude the reading in which the NP I serves as the antecedent of pro, however, nothing should prevent IMP from doing so, predicting a grammatical result.

Interestingly, in earlier work, Landau (2013) and van Urk (2011, 2013) argue that an Agree approach to control offers an account of VG in addition to the lack of Visser’s effects in impersonal passives like (3a,b). They suggest that in personal passives like (10a,b) the matrix T must undergo Agree with the overt NP in its Spec in order for that argument’s case licensing needs to be met. This makes the matrix surface subject the designated controller, predicting grammaticality when this designation aligns with the semantically designated controller, as in (10a), as well as ungrammaticality when it does not, as in (10b). Impersonal passives are then argued to allow control by the impersonal passive agent precisely because T does not have to undergo Agree with expletive it, the latter’s function simply being to check T’s EPP feature.

As we will see in the next subsection, certain facts involving impersonal passives introduced in Reed (2018a, 2018b), as well as novel data being introduced here appear to be problematic for this particular Agree approach to the data. Such facts led Reed to advocate a Bare Output Condition approach to control. However, Section 4 will show that key modifications can be made to the Agree approach that allow it to preserve Landau and van Urk’s insights without recourse to a separate “control theory” as in Reed.

2.2. Impersonal Passives

Having considered how VG poses problems for the TTC, let us consider next how Reed’s (2018a, 2018b) data pose problems for it as well. Her facts primarily involve French, but also English, impersonal passives that exhibit the three “signature” characteristics of non-obligatory control (NOC) uncovered in earlier literature and summarized in Landau (2000, pp. 31–36; 2013, p. 181, pp. 232–33). Namely, Reed introduces impersonal passives that have licit arbitrary readings, ones that involve long distance control, and others that license strict readings under VP-ellipsis. As she observes, the existence of these facts is problematic for Landau’s (2013) and van Urk’s (2011, 2013) Agree approach to control since they advocate a theory in which NOC can only arise when Agree is syntactically barred from determining PRO’s antecedent and, in the case of impersonal passives, the structure they propose always makes that route possible.6

This section will show two things. First, in those areas in which the grammar of Dutch allows for a replication of Reed’s results, the native speakers of that language that were consulted by the present author reported that impersonal passives can exhibit the signature characteristics of NOC.7 This fact will tentatively be interpreted here as indicating that this construction may allow NOC cross-linguistically, although this claim awaits verification by future researchers. Secondly, and most importantly, the fact that impersonal passives in some dialects of these languages do clearly allow NOC will be shown to be as problematic for the TTC as Reed showed it to be for the Agree model.

With respect to the data, consider first the fact that Dutch speakers reported that the example in (11) allows an arbitrary reading, i.e., one in which PRO is understood to refer to any arbitrary candidate who wishes his or her application to be considered by the selection committee. In other words, PRO does not have to refer to the implicit argument of the passive verb meaning preferred, which is the members of the committee. The native speakers that were consulted by the present author reported that the same is true with respect to the English gloss and Reed originally showed this to be true of French.

- (11)

- Ik benaderde de selectiecommissie met de vraag hoe mijn foto aan teI contacted the selection.committee with the question how my photo prt toleveren.? Er bleek dat er (door het comité) de voorkeur aansupply there turned-out that there (by the committee) the preference togegeven wordt [om deze aan te leveren in jpeg].given is COMP these prt to supply in jpeg‘I contacted the selection committee about how to submit my photo.It turns out that it’s preferred (by the committeex) [PROarb to submit in jpeg].’

For purposes of comparison, (12) shows that PRO in the preceding example contrasts in this respect with PRO in a structure that uncontroversially involves OC.

- (12)

- The committeex prefers [PROx/*arb to submit photos in jpeg].

The sentence in (13) next shows that Dutch (and English) impersonal passives allow long distance control, as Reed also showed to be true of French. The pragmatic context here is one in which there are two individuals on the telephone who were supposed to get together in Chicago for a meeting set up by a third party, the speaker’s secretary. Native speakers of Dutch have reported that PRO in this case can be understood to refer not to the implicit argument of the passive verb meaning arranged (i.e., to the secretary), but rather to the two people having the conversation.

- (13)

- Verbolgen zakenvrouw aan haar telefoon in Chicago:irate businesswoman on her telephone in ChicagoWaar ben je? Er was door mijn secretaresse geregeldwhere are you there has.been by my secretary arranged[om elkaar hier in Chicago te ontmoeten].COMP each.other here in Chicago to meet‘Irate businesswoman on her phone in Chicago:Where are you? It was arranged by my secretaryx[PRONOC=speaker+listener to meet each other here in Chicago!]’

As expected, obligatory (partial) control PRO in (14) differs from the preceding example in this respect:

- (14)

- My secretary Alanx arranged [PROx+listener/*speaker+listener to meet you in Chicago].

In sum, it appears that Reed may be correct in claiming that impersonal passives can license NOC readings in some languages/dialects. Before considering whether this is problematic for the TTC, let us first briefly address the issue of just why native speakers report that PRO in the vast majority of impersonal passives simply must refer to the understood agent of the passive verb. In other words, let us consider why this construction could often be perceived by native speakers to involve obligatory control (OC) when it technically does not.

Reed, extending a proposal in Williams (1992), suggests that this is due to the pragmatics involved in antecedent determination in contexts of NOC. Namely, Williams was the first to observe in relation to contrasts of the type in (15a,b) below that PRONOC often must be interpreted “logophorically” in the sense that it is judged to be grammatical only if it refers to the person whose thoughts, feelings, or speech is being reported. In other words, naïve native speakers consistently report (15a) to involve “obligatory control” by the NP Bill, when, technically speaking, it does not.

- (15)

- [PRONOC=x having just arrived in town], the main hotel seemed to Billx to be the best place to stay.

- *[PRONOC=x having just arrived in town], the main hotel collapsed on Billx.

Given that the understood agent of a passive attitude verb is the logophoric center, it is expected to be the usual referent of PRONOC unless some “atypical” context either precludes or strongly disfavors it. The contexts in (11) and (13) are of that atypical type: selection committees often have preferences with respect to the format of a candidate’s dossier, yet they are unlikely to do the actual work involved in complying with them. Similarly, secretaries frequently set up meetings that other people attend.

Thus far, this section has shown that Reed’s observations concerning the licitness of NOC in French and English impersonal passives may well extend to certain dialects of Dutch. Let us next consider whether this fact proves as problematic for the TTC as she shows it does for the earlier Agree model.

That it does becomes obvious when one reconsiders the preceding discussion concerning the grammaticality contrasts in (5a,b). Namely, we saw that Landau accounts for the apparent restriction on impersonal passivization to complement clauses of attitude verbs via the assumption that these constructions are uniquely contexts of OC.8 That is, it is only by assuming that PRO must have its antecedent obligatorily determined via predication, be it directly (as is the case for non-attitudes) or indirectly (as is the case for attitudes), that the TTC is able to explain why only the latter class of verbs tolerate impersonal passivization. That is, Landau claims that only attitudes accept impersonal passivization because only they select for a complement clause with an enriched CP layer (one containing a pro) that opens up an indirect, binding route of control.

2.3. On the Attitude/Non-Attitude Constraint

A third area that proves problematic for the TTC involves ungrammatical French and English impersonal passives of the type in (16a,c), noted in Reed (2018a, 2018b), and grammatical Dutch sentences of the type in (17a,b), originally observed in Evers (1975) and Koster (1987, p. 120), and novel French (17c,d) and English examples like (17e–j).9 The former show that there are many attitude predicates that do not tolerate impersonal passivization, the latter that, in many languages, there are also numerous non-attitude verbs that allow it.10

- (16)

- *Il a été menacé [de PRO fermer l’établissement].it has been threatened of to.close the establishment*‘It was threatened to close down the establishment.’

- *Il a été adoré [PRO danser toute la nuit].it has been loved to.dance all the night*‘It was loved to dance all night long.’

- *Il a été offert [d’amener le vin].it has been offered of to.bring the wine*‘It was offered to bring the wine.’

- (17)

- Er werd geprobeerd (om) Bill te bezoeken.there was tried for Bill to visit‘Someone tried to visit Bill.’

- Er werd vermeden vrag en te stellen.there was avoided questions to ask‘People avoided asking questions.’

- Il a été essayé plusieurs fois sans succès de neutraliserit has been tried several times without success of to.neutralizeles effets dévastateurs de ce virus.the effects devastating of this virus‘It has been tried many times without success to neutralize the devastatingeffects of this virus.’

- Une fois de plus, il a été évité de poser le problème sur le planone time of more it has been avoided of to.pose the problem on the planede la responsabilité entre états…of the responsibility between states‘Once again, they avoided addressing the problem in terms of the responsibilityshared between member states.’

- It has been tried/attempted for some time now to put together a proposal thatwe can all live with.

- It had never previously been undertaken to cross the Atlantic on a wooden raft.

- It should have been required of AIG to make concessions to their counterparties.

- According to the Norwegian animal welfare regulations, it has been forbiddento build new tie-stall barns since 2004.

- From the videos, it was managed to confirm that the participants followedthe task instructions…

- It has been managed/dared by only a select few to scale this mountain underthese conditions.

The examples in (17g–i) were drawn from journals listed on ludwig.guru.

In line with the discussion of (5a,b) above, the TTC would associate the examples in (16a-c) with a structure parallel to (18a) and the ones in (17a–j) with the one parallel to (18b). These structures lead one to expect judgments counter to those attested. Namely, the ungrammatical sentences in (16) are predicted to be grammatical because there should be a binding route available for control, and, as Pitteroff and Schäfer (2018) observe with respect to Dutch-type languages, grammatical ones like (17a–j) are predicted to be ungrammatical because there is none.

- (18)

- It was IMPi agreed/decided [CP proi [FinP PROi to establish a new nation on new principles]].

- *It was IMPi continued/forgotten [FinP PROi to move forward with this project].

To summarize, this section has looked more closely at three empirical areas in which passivization interacts with control in view of evaluating the degree to which the TTC successfully accommodates the facts. The discussion has shown that the TTC presently does not account for Visser’s Generalization; it incorrectly precludes NOC in impersonal passives; and it both under- and overgenerates since grammatical impersonal passivization is expected with any attitude verb and ungrammaticality with any non-attitude one.

It is interesting to observe that in all three areas, the problems arise because of two assumptions underlying the TTC, namely, that the attitude vs. non-attitude verb distinction is syntactically encoded via distinct complementation types and that this encoding, being semantically based, must be uniform across a given class. In other words, the attitude/non-attitude distinction paves the way for two distinct routes of control, with all members of a given class being associated with exactly the same “route.”

In the next section, it will be argued that a fuller account of the data can be made to follow from a uniform Agree approach to control that preserves many of Landau’s insights without making these two assumptions. In addition, it will be optimally parsimonious in that no recourse will be made to control-specific notions like Landau’s (2000) earlier [+/−R] feature or his current assumption that control verbs are special in that only they obligatorily c-select for transitive FinPs (Landau 2015). In this respect, the approach put forth here will be very much like Reuland’s (2011) MT approach to binding phenomena in both spirit and technical implementation.

3. A Modified Agree Approach to Control

Let us begin by clarifying the status of PRO under this analysis. In seminal MT work by Harley and Ritter (2002), Pesetsky and Torrego (2004a, 2004b), and others, overt pronouns are syntactically treated as bundles of interpretable and uninterpretable features, the phonetic realization of which is determined at PF by vocabulary insertion rules. Logically, then, the same type of approach should, and will, be adopted here with respect to PRO.

In view of doing this, consider first the types of lexical entries and vocabulary insertion rules these authors have put forth for overt English pronouns, given below in (19a-i). According to (19a), the pronoun I is the PF spell-out form of the feature bundle interpretable [D] categorial feature, interpretable [+singular] number feature, interpretable [+participant (in the linguistic exchange)] person feature, interpretable [+author (i.e., speaker/writer)] person feature, and an uninterpretable [case] feature that has been valued as [Nominative] via agreement with finite T during the course of the derivation. Similarly, (19b) states that me spells out a feature bundle that is identical to I except its case feature has been valued [+Accusative] by v/AgrO. Similar claims are made in the other entries. The pronoun it has two entries in (19g,h) because it is the only pronoun in the sample that has separate referential and expletive uses.

- (19)

- [i D], [i sing +], [i part +], [i author +], [u NOM] → I

- [i D], [i sing +], [i part +], [i author +], [u ACC] → me

- [i D], [i sing −], [i part +], [i author +], [u NOM] → we

- [i D], [i part +], [i author −], [u Case] → you

- [i D], [i sing +], [i part −], [i fem. +], [u NOM] → she

- [i sing +], [i part −], [i male +], [u NOM] → he

- [i D], [i sing +], [i part −], [i thing +], [u ACC] → it

- [i D], [i sing +], [i part −], [u Case] → it

- [i D], [i sing −], [i part −], [u NOM] → they

While the overt pronouns in (19a–i) are fully specified for interpretable ϕ-features, PRO has long been assumed to lack any inherent interpretable specification for person, number, and gender, acquiring those features, in some way(s), from the understood antecedent, also known as the controller. Interestingly, previous work in minimalist theory (MT) indicates that there are overt pronominals that appear to mirror PRO to a degree in this respect, so-called “minimal pronouns.”

Kratzer (2009), for example, observes in relation to the sloppy or bound variable reading of the Partee (1989, fn. 3) inspired examples below in (20a,b) that at LF my and you cannot be fully specified for the person features they overtly bear since they respectively refer not only to the speaker and the listener, but to others as well. That is, (20a) can convey not only that the speaker is the sole person capable of taking care of his or her own children, but also that other individuals are unable to take care of theirs. In other words, my can interpretively extend beyond the first person feature for which it is overtly inflected. Similarly, (20b) can mean not only that the listener is the sole person who is able to eat what s/he cooks, but also that others cannot eat the food that they themselves have prepared.

Kratzer (2009), for example, observes in relation to the sloppy or bound variable reading of the Partee (1989, fn. 3) inspired examples below in (20a,b) that at LF my and you cannot be fully specified for the person features they overtly bear since they respectively refer not only to the speaker and the listener, but to others as well. That is, (20a) can convey not only that the speaker is the sole person capable of taking care of his or her own children, but also that other individuals are unable to take care of theirs. In other words, my can interpretively extend beyond the first person feature for which it is overtly inflected. Similarly, (20b) can mean not only that the listener is the sole person who is able to eat what s/he cooks, but also that others cannot eat the food that they themselves have prepared.

- (20)

- I am the only one here who can take care of my children.

- Only you can eat what you cook.

Kratzer suggests that this intriguing “disconnect” between overt morphological inflection for ϕ-features and their semantic interpretation can be made to follow from the assumption that pronouns do not always enter a derivation fully specified for person, number, and gender. They may sometimes do so entirely lacking a portion of this feature bundle and when this occurs, the “absent” feature(s) must later be acquired at PF in order for the pronoun to be “pronounceable,” i.e., to satisfy PF interpretability conditions. More specifically, when a pronoun enters a derivation ϕ-complete, a referential reading is derived. The sentence in (20a) will, for example, convey the idea that only the speaker is able to take care of the speaker’s children and will say nothing about other people’s abilities with respect to their own. On the other hand, when it enters the derivation underspecified for (i.e. lacking) certain ϕ-features, the bound variable reading arises. In particular, the “missing” feature(s) are acquired at PF via feature transmission under binding, the latter being previously set up in the computational component via Agree. More specifically, if a minimal pronoun undergoes Agree for independent reasons with a head fully specified for interpretable ϕ-features within the computational system, as, for example, my children does with v in (20a), then the ϕ-features of the latter can be “added to” or “unify with” the impoverished feature bundle of the minimal pronoun at PF. Since this unification occurs “late,” the minimal pronoun comes to obligatorily agree morphologically with its antecedent in ϕ-features while differing from it with respect to the interpretation of those features.11

Kratzer (2009, fn. 2, pp. 198, 232) and Reuland (2011, pp. 307–11) suggest that PRO is a member of the class of minimal pronouns. However, they leave the details of its analysis open for future research. Landau (2015, p. 23) appears to follow up on their suggestion when he proposes the lexical entry in (21) for PRO, according to which it entirely lacks inherent specification for interpretable ϕ-features. As his entry makes clear, however, he departs from Kratzer (and follows Reuland) in assuming that PRO enters derivations with a complete set of unvalued ϕ-features already in place. What makes a pronoun “minimal” for him, in other words, is simply that a portion (in PRO’s case, all) of that feature bundle is unvalued.

- (21)

- [i D], [u ϕ]

Given the Safir (1985) facts in (8a,b) and (9a,b), Landau’s original entry in (21) will be adopted here with one minor modification. Namely, an inherent [-expletive] feature will be assumed to be form part of (21). This assumption is necessary in order to capture the ungrammaticality of examples like (8b) and, especially, (9b) above.12 It appears to be further justified by the fact that the vast majority of pronouns in English, French, and other languages are non-expletive. In English, for example, only it and there may serve as dummy pronouns, and even they are not unambiguously so, being associated with referential entries as well. In this respect, then, PRO is very much a “normal” pronoun that fits into the pronominal paradigm in (19).13 Specifically, PRO will be assumed that the Spell-Out form determined by the vocabulary insertion rule in (22).

- (22)

- elsewhere → ∅

Given Kiparsky’s (1973) Elsewhere Condition or Halle’s (1997) Subset Principle, (22) makes the claim that PRO is the phonetically null spell-out form of a pronoun unassociated with any of the more specified feature bundles in a given language. In English, for example, PRO will be the form that surfaces when a pronoun is not associated with the more fully specified features in (19a–i) above, explaining, in MT terms, why PRO never appears in positions specified for Case. It is important to note that other languages will have different feature specifications for various overt pronouns, which means that PRO’s distribution may well vary from language to language in interesting ways that will be left open for future research, much as Reuland (2011) observes in relation to binding phenomena. In any case, however, PRO will be assumed here to be the Elsewhere pronominal form universally.

Having clarified the lexical entry of PRO that is being adopted here, we can turn next to the issue of how it comes to be morphologically and semantically associated with the person, number, and gender features of its controller.

As a point of departure, let us first reconsider how Landau (2015, 2016) addresses this issue. Following Kratzer (2009), he suggests that PRO is like other minimal pronouns in that it must acquire a complete set of ϕ-features “late,” at PF, in order to be interpretable to the A-P system, a proposal that may initially seem odd with respect to PRO since there is usually no immediately obvious (i.e., overt) disconnect between its understood ϕ-features and those of the antecedent. In support of this position, however, Landau observes that although partial control PRO (PROPC) in French sentences like (23) is apparently associated with the same morphological ϕ-features of its understood antecedent, it interpretatively differs from it in number. That is, the use of the first person, singular reflexive pronoun me ‘myself’ in (23) indicates that PRO matches the controller je ‘I’ in morphological ϕ-features even though it interpretatively must refer to a plural group of individuals that only includes the speaker.

- (23)

- Je préférais [PROPC me réunir dans la salle de séminaire].I preferred myself to.meet in the room of seminar‘I preferred to meet in the seminar room.’

To account for this “disconnect” in morphological and semantic number, Landau follows Kratzer in assuming that Agree relations previously established in the computational component determine a minimal pronoun’s morphological ϕ-features at PF, while its semantic features are determined in a distinct way at LF. His technical implementation with respect to PRO differs from her approach to other minimal pronouns, however, since the notion of feature unification under binding is abandoned in favor of Pesetsky and Torrego’s (2004a, 2004b) and Reuland’s (2011) feature sharing under Agree. In (23) above, for example, Landau assumes that PROPC enters the derivation with a full set of unvalued ϕ-features. These features become valued via predication (a form of Agree), coupled with binding in the case of attitude verbs, in the fashion overviewed in Section 2. These features are then spelled out at PF as being morphologically identical to those of the controller.14 Because feature sharing is assumed to occur at PF, it is “too late” to determine semantic interpretation. Therefore, PROPC’s semantic ϕ-features are determined at LF, again with reference to Agree relations previously set up within the computational system. More specifically, we noted in Section 2 that predication, coupled with binding in the case of attitude verbs like the one in (23), is assumed to account for the fact that the reference of PROPC must include that of the controller. The understood plurality of PROPC is attributed to an abstract associative morpheme (AM) on the embedded T that functions as a group operator on the index of the controller, yielding a set that includes at least one other discourse salient referent.15

Although Landau’s conception of PRO as a minimal pronoun in (21) is being adopted here, the discussion of Section 2 has made it clear why his approach to its ϕ-feature determination (i.e., control) is not. Before turning to the specifics of how the present analysis makes these determinations, however, there is an issue that warrants some discussion not only because it arises in relation to the PC example just discussed, but also because its resolution impacts on the form the new approach will take. Namely, the discussion of (23) has revealed an empirical area not involving passivization that Landau (2015, 2016) argues offers particularly strong support for his TTC. In other words, we have seen that, under his analysis, the semantics of non-attitude verbs is such that they select for an impoverished CP that allows only direct predication as a means to establish control, whereas attitudes select for an “enriched” CP, one containing a pro that opens up an indirect (binding + predication) means of doing so. This means that only the latter class of verbs can allow PC since direct predication with feature valuation within the computational component is assumed by Landau to entail a complete match in the morphological and semantic ϕ-features of PRO and the controller. The grammaticality contrast between PC examples involving attitudes like (23) and ones involving non-attitudes like (24) is put forth as evidence for this claim.

- (24)

- *Mary bothered/remembered [PRO to meet in the seminar room].

While native speakers consistently report the contrast between (23) and (24), the conclusion that it can only follow from a TTC is cast into doubt by a number of alternative approaches to PC that exist in the literature, only a handful of which will be discussed here since the goal is not to determine which approach to PC is the best one, but rather that a “single-tiered” approach to control is not at odds with the very existence of this phenomenon.

Let us first consider the influential semantic approach to PC put forth in Pearson (2013, 2016). An examination of her analysis, which is formulated in relation to Landau’s (2000, 2013) earlier Agree model, reveals that it also challenges his more recent TTC and, in particular, his assertion that PC readings arise because the syntax of attitude control verbs (i.e., the type of complement they select) gives rise to a structure that allows binding coupled with predication, whereas EC results from predication. More specifically, Pearson (2016, p. 699) develops an equally viable approach to PC that uniquely involves predicative CP complement clauses, proposing that the lexical semantics of a given matrix control verb is what determines whether or not a PC reading is licensed. In particular, Pearson (2016, pp. 728–29) suggests that PC is an epiphenomenon that is parasitic on the grammar’s need to represent the semantic nature of events. Integrating seminal insights in Landau’s earlier work concerning the temporal “mismatches” exhibited by PC verbs, Pearson argues that only attitude verbs license PC because only their lexical semantics requires that the property expressed by the complement clause be interpreted relative to world <w>, time <t>, and individual <i> arguments distinct from those associated with the matrix verb. These distinct indices allow for “shifts” in both time and subject between the matrix and complement clauses, the latter type of “shift” allowing for a semantically plural PRO to be introduced. The meaning of EC verbs, on the other hand, is claimed to be such that the embedded clause must be interpreted relative to the same <w,i,t> as the matrix, precluding any shift in time or subject. PC is, therefore, licensed in an example like The chair of the committeek expects [PRO+k to meet today at noon]. because the truth of the embedded clause is evaluated not with respect to <w,i,t> of the matrix, but rather with respect to the set worlds consistent with the chair’s expectations in which there is an agent who stands in a systematic way to the chair (namely, that agent is the entire committee of which the matrix subject is the head), and at a specific time subsequent to the time at which the expectation is held, that plural agent meets at noon. On the other hand, *Maryk bothered [PRO+k to meet in the seminar room]. is unacceptable because the truth of the complement clause is lexically specified for interpretation relative to the same indices of the matrix. Thus, the time <t> of the embedded clause cannot shift, nor, more importantly, can the reference of the subject. The latter fact precludes PRO from being plural, as required by collective meet.

Pearson’s work not only shows that PC can be captured without the two-tiered syntax advocated by Landau, but it also challenges the claims he makes with respect to which verbs license PC and why. While Landau (2015) assumes that attitude verbs uniformly license PC, Pearson (2016, pp. 719–20) argues that only a subset of them do. Furthermore, she includes in the set of attitudes, verbs that Landau has long excluded, accounting for the lack of PC with these verbs in lexical semantic terms. As we will see, the class of potential licensers of PC is reduced under Pearson’s theory. What is important about this is that, if she is correct, then this seriously calls into question Landau’s claim that it is the uniform type of complement clause selected by attitudes that licenses PC. The second syntactic “route” of control is no longer what is truly licensing the phenomenon, so the theory would require additional machinery to rule out PC with a subset of attitudes. Since Pearson’s approach appears to be able to make the cuts where they need to be made in terms of a single syntactic route of control supplemented by lexical semantics, the null hypothesis would be that this is the way to proceed.

To explain, Pearson (2016, pp. 706–7, 714) uses the standard tests assumed in Landau (2015) involving “double vision” puzzles to show that claim and pretend are indeed both attitude verbs, as he claims. However, she departs from Landau in arguing that both fail to license PC, cf. the ungrammaticality of sentences like *John claimed/pretended to live together, which is to be contrasted with examples such as John wanted to live together.16 On the other hand, Landau (2015, p. 6) excludes implicative verbs like try from the class of attitudes, cf. *John tried to live together, but Pearson (2016, p. 718) argues that the classic tests place this verb in that category, so some distinct factor must account for its inability to license PC.

To account for these facts, Pearson (2016, p. 719) proposes that only canonical attitude verbs that involve non-simultaneous temporal interpretation license PC. Claim and pretend are said to preclude PC because they are simultaneous (cf., e.g., *Yesterday John pretended/claimed to be sick tomorrow). Try precludes PC as well, but in this case it is because it is a “non-canonical” attitude, as made clear by the pragmatically odd existence entailment associated with sentences like #John tried to ride a unicorn, which is lacking in a canonical attitude example like John wants to ride a unicorn.

In short, the preceding discussion has shown that Pearson’s approach to PC removes the need to syntactically license PC vs. EC via distinct complementation types: the same type of complement clause (a predicative CP) is able to capture the facts in lexical semantic terms.

The analysis recently developed in Haug (2014) also challenges Landau’s approach to PC and at an even more fundamental level. Although Haug sees no need to take a position with respect to the syntax of PC and EC, explicitly leaving open the possibility that attitudes and non-attitudes may (or may not) select different complement types, he nonetheless advances empirical and semantic arguments that support Pearson’s lexical semantic account of the time shift attested in attitude sentences involving PC, but cast doubt on approaching subject shift the same way. He instead argues that the understood plurality of PROPC should be treated in terms of the pragmatic phenomenon of “bridging” (Clark 1975; Asher and Lascarides 1998; Nouwen 2003). If correct, then Haug’s results would equally preclude the type of syntactically-based “hard-wiring” that Landau (2015) makes use of to encode the plurality of PROPC, namely, his abstract associative morpheme.

To see this clearly, let us first consider Haug’s empirical argumentation. He notes with Landau and many others that PC is always somewhat marginal and requires strong contextual support. He observes that the experimental results obtained in White and Grano (2013, p. 474) formally confirm this. Their psycholinguistic study of the grammaticality judgments of native speakers of American English reveals a statistically significant degradation in the acceptability of any sentence involving PC, even one involving a canonical, non-simultaneous attitude verb. As Haug (2014, p. 218) points out, this result is unexpected if PC is “hard-wired.” However, it follows if PC is a pragmatic repair strategy triggered by semantic ill-formedness, as he suggests.

In terms of semantic argumentation, Haug (2014, pp. 220–21) shows that Pearson’s hard-coding approach to subject shift makes incorrect scope predictions, while her parallel treatment of time shift does not. Namely, he observes that since both shifted elements are assumed to be lexically encoded by the matrix verb both should obligatorily take low scope relative to any operator that outscopes it. That this prediction is only met with respect to time shift is made clear by the paraphrases of his sentence in (25) in which the matrix subject everybody, which Pearson predicts should take wide scope over both PROPC and the embedded time argument (leading to distributive readings in both cases), can, in fact, only distribute over the <t> index.

- (25)

- Everybody wanted to have lunch together.Cannot be paraphrased:For all x, x wanted there to be a group y of which x is a part such that yhas lunch together.cf. !Everybody wanted to have lunch together, but with different people.Can be paraphrased:Everybody wanted to have lunch together, but they all had differenttime preferences.

Similarly, he observes that (26a) is incorrectly predicted to allow the reading in (26b), in which the modal component of want takes scope over PROPC, but it can only mean (26c), in which PROPC clearly outscopes modality.

- (26)

- John is lonely. He wants to have lunch together.

- John wants someone to have lunch with.

- John wants to have lunch with some contextually salient group that includes himself.

Given these considerations, Haug concludes that an alternative approach to PC is warranted and he develops one in terms of partial compositional discourse representation theory (PCDRT), treating examples of PC like (27) on a par with non-control structures like (28a–c). In short, PC is viewed as a type of discourse anaphora, more specifically, it is assumed to involve pronominal bridging, parallel to (28b–c).

- (27)

- The chairi wants [PRO+i to gather at six].

- (28)

- The chairi is happy. The committee+i met at six.

- My next-door neighbors make a lot of noise.He plays the drums and she keeps on shouting at him.

- The priest was tortured for days. They wanted him to reveal wherethe insurgents were hiding.

Under his analysis, many of the examples of PC that native speakers judge to be ill-formed involve “failed” bridging, on a par with similar failures involving overt pronouns, such as the ones in (29a–b) below.

- (29)

- My next-door neighbors make a lot of noise. #I met her yesterday.

- #Every doctor wants him (=the patient) to get better.

More specifically, Haug follows Nouwen (2003, pp. 74–76) in assuming that pronominal bridging is subject to a number of pragmatic conditions that include coherence, referential uniqueness, and the use of uniquely semantic information to make the “bridge.” The sentence in (29a) above, for example, violates the coherence condition, there being no clear link between the first sentence and the second one, in contrast with the acceptable example in (28b). Sentence (29b), on the other hand, involves violations of both the uniqueness condition and the restriction involving the use of uniquely semantic information to make the bridge since the semantics of doctor fails to introduce a unique patient to which him would refer.

In relation to PC, Haug makes use of these same conditions to account, among other things, for the unacceptability of “superset control” observed in Landau (2000, p. 7) and illustrated below in (30). That is, a reading in which the committee agrees that one of its members, namely, the chair, should wear a tie is ruled out because the lexical semantics of committee does not allow for that unique individual to be picked out as the referent of PRO.

- (30)

- The chairi was glad the committeex had agreed [PROx+ to wear a tie].

Although Haug does not do so, it seems plausible to extend his approach to explain the contrast in (31a,b), drawn from Landau (2013, p. 164).

- (31)

- The chair wanted [PROPC to meet at 6:00].

- *The chair met at 6:00.

Namely, in (31a) the pragmatic repair strategy is triggered by the ill-formedness of the exhaustive control (EC) reading, this ill-formedness being due to a clash between the collective nature of meet and singular meaning of the chair. Bridging is successful because each of the aforementioned pragmatic conditions are fulfilled. That is, one need only make reference to semantic information related to the chair to identify a unique referent for PRO (the committee of which s/he is the head) to arrive at a coherent discourse. In contrast, the non-control example in (31b) remains ill-formed until much stronger contextual support is provided, as in (32):

- (32)

- After trying for weeks to find a time when everyone is free,the chairx has finally given up. Important decisions have to be made, so shex ismeeting this Saturday morning at 6:00 am, even if it means meeting all by herself.

In sum, we have seen that Haug provides a second approach to PC that in no way entails distinct complementation with respect to attitude and non-attitude verbs.17 In fact, one could even argue that his analysis could be used to re-open the door to the still more radical view, defended, e.g., in Bowers (2008, pp. 138–41), that if PC does reduce to EC in the case of attitudes, then perhaps it can be found with non-attitudes as well, given appropriate pragmatic conditions. The grammaticality of the portion of Bowers’ examples given below in (33a–c), which involve matrix control verbs of the EC/non-attitude class, appear to support this view, as do the novel examples in (34a,b).18

- (33)

- The chair managed to meet at 6:00.

- The union organizer didn’t dare to gather during the strike.

- The chair forgot to meet this week.

- (34)

- If I were chair, I wouldn’t bother to meet in the conference room today.We can all save ourselves a trip to campus and meet at Panera instead!

- I just can’t stand it anymore! I told myself that I was done with you and me, butafter a week apart, I now realize that I need to kiss and make up—right here andright now. It’s that or I simply go insane.

To summarize, the purpose of this brief discussion of PC has been to show that there exist alternative approaches to the phenomenon that do not entail adopting Landau’s “enriched” vs. “impoverished” CP approach to control. These alternative analyses theoretically allow for the contrast between examples like (23) and (24) above to be captured without the recognition of two types of PROOC—PROEC and PROPC—each subject to a distinct means of ϕ-feature determination. Given this, the null hypothesis would be that there are not. This is the working hypothesis adopted here.

Having clarified the position being taken here with respect to PC, let us return to the question of how PRO’s ϕ-features are determined under this new approach. The point of departure is Reuland’s (2011) “minimal pronoun” analysis of Dutch zich ‘himself’ since, as the discussion will soon make clear, crucial aspects of his proposals are going to be extended here to control.

Reuland observes, in line with earlier literature, that Dutch zich ‘himself’ can refer not only to masculine singular entities, as it does in his example below in (35), but also to masculine plural ones, and even feminine or neuter antecedents in both the singular and the plural. Given this, he concludes that zich is inherently specified for interpretable categorial and third person features, but lacks inherent gender and number, interpretatively acquiring those feature specifications, in a way to be made clear momentarily, from its antecedent. We observe, with Landau (2015), that PRO behaves in a parallel fashion, except it lacks inherent specification for any ϕ-features, acquiring them all, in a fashion to be made clear shortly, from its antecedent.

- (35)

- Willemx voelde [zichx wegglijden].‘William felt himself slip away.’

To formally account for the acquisition of zich’s understood gender and number features, Reuland adopts the lexical entry below in (36), according to which it is inherently specified for an interpretable [π] categorial feature, an interpretable third person feature, and unvalued number and gender features.19 In other words, he assumes, contra Kratzer, that minimal pronouns enter derivations with full feature bundles. What makes a pronoun “minimal” is the presence of underspecified features that require valuation under Agree in order to respect the principle of full interpretation (PFI) at PF and LF.

- (36)

- [i π ], [i 3rd], [u number], [u gender]

Reuland next proposes that the effect of Agree sometimes extends beyond simple feature valuation to include a process of feature overwriting/replacement, with the proviso that this does not violate the principle of recoverability of deletion (PRD), i.e., does not modify the original interpretation of the overwritten lexeme. In other words, agreement relations standardly assumed to exist within MT are assumed to not only value uninterpretable features, but also, in certain cases, entirely replace them, making them instances of the same feature(s). When this occurs, the affected lexeme becomes the theoretical equivalent of a copy.

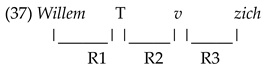

In the case of zich in (35) above, for example, it is standardly assumed that there is agreement between finite T and Willem that values the latter’s [u Case feature] and the former’s [u ϕ-features]. In addition, finite T is standardly assumed to agree and create a tense dependency with v, valuing the latter’s [tense] feature. Finally, v is assumed to agree with zich, valuing the former’s [u ϕ-features] and the latter’s [u Case feature]. In short, there are standardly assumed to be the three distinct agreement chains R1–R3 indicated below in (37).

Reuland suggests that these three chains compose to form a single complex chain with the ϕ-features of Willem available to overwrite those of zich because this does not violate the PRD. More specifically, the ϕ-features of Willem can replace those of zich because the only specified features zich inherently has (its categorial and person features) are interpretive constants and so can be replaced by those of Willem without changing zich’s original interpretation. That is, every lexeme associated with a nominal categorial feature is subject to the same semantic interpretation rule, so Willem’s categorial feature can overwrite that of zich without modifying the latter’s original meaning. Similarly, third person features are always interpreted as [-speaker, -addressee]. Therefore, those of Willem again “will do.” Finally, zich is inherently unspecified for number and gender, so overwriting those features with those of Willem also respects the principle of recoverability of deletion (PRD). In short, chain composition and feature overwriting make zich indistinguishable from Willem. The two have literally the same features. They do not happen to be specified for the same feature settings, as is the case in a sentence like (38) below, in which John and him both had the same third person, singular number, and masculine gender feature settings upon entering the derivation. Put differently, feature overwriting is impossible in the case of him in (38) because him has an inherent number feature that would contribute to a distinct interpretation—one in which him does not refer to John. In this case, therefore, overwriting is precluded by the PRD.20

- (38)

- John loves him.

To complete his analysis, Reuland proposes that syntactic feature overwriting is treated by the semantic component as logical syntax binding as the latter is conceived of in Reinhart (2000, 2006).21 More specifically, Reuland assumes that pronominals consist uniquely of ϕ-feature bundles—i.e., they lack the type of intrinsic descriptive or referential content associated with non-pronominals like cat, which means that they are unable to directly refer. Put differently, they function semantically as variables and, as such, must be “closed off” (i.e., become referentially identified) as soon as possible via variable binding. The requirement that this closing off occur “as soon as possible” means that binding within logical syntax, i.e., binding previously “set up” via feature-overwriting within the computational system as in (35), takes precedence over pragmatic and semantic antecedent determination. In other words, the accidental co-reference (pragmatic binding) in (39) and semantic binding in (40a,b) are both “last resort” strategies that determine the reference of a pronoun only when the syntactically-driven means are not available, i.e., when there is no agreement and hence no possible chain formation.

- (39)

- Johnx has a gun. Will hex attack?

- (40)

- Johnx saw a snake near himx.

- Johnx said that Mary likes himx.

Finally, Reuland (2011, pp. 132–33) notes that if agreement is available to set up syntactically-driven antecedent determination, but this derivation “crashes,” as it does, for example on the bound reading of (38) above, then the “last resort” strategies are barred. In other words, “Rejection is Final.” A discourse strategy, for example, cannot be later invoked to “smuggle in” a reading blocked within the computational system.

With this brief overview in place, we can turn now to how these proposals, developed in relation to binding, can be extended to control. In line with Reuland’s approach, we assume that (a) minimal pronouns (in this case, PRO) enter derivations with part (in PRO’s case, all) of their ϕ-features unvalued; (b) Agree not only systematically values the underspecified features of the minimal pronoun to satisfy the principle of full interpretation (PFI), but it may also set up a complex chain that entirely replaces those features, provided there is no violation of the principle of recoverability of deletion (PRD). In this case, the overwritten lexeme is the equivalent of a copy; (c) feature overwriting is interpreted as binding by the semantic component; (d) this computationally-driven process of referentially identifying pronouns takes precedence over any pragmatic or purely semantic means of doing so; (e) as is standard in minimalist theory, Agree is local and proceeds in phases headed by C and v; and, finally, (f) C and v can only serve as probes for goals in their local c-command domain (TP and VP respectively).

Let us now consider the effects these assumptions have in relation to a classic example of obligatory subject control, as in (41):

- (41)

- Maryx prefers [FinP to PROx have tea with her breakfast].

As the preceding structure makes clear, it is being assumed here, on the basis of evidence involving Q-float and Romance clitic climbing placement discussed in Baltin (1995) and Reed (2014, pp. 257–58), that PRO does not obligatorily undergo movement from its initial merge position in Spec, vP, although the reader should bear in mind that nothing crucial hinges on this assumption with respect to the data being treated in this paper.

As (41) makes equally evident, it is also being (this time, crucially) assumed, following Reed (2014), that obligatory control (OC) involves FinP complementation, whereas non-obligatory control (NOC,) as in (42a–c) below, involves ForceP (formerly, CP) complementation:

- (42)

- Your babyx doesn’t know [ForceP when to PRONOC=z feed himx]. Youz do!

- Iz think that my momx has figured out [ForceP where to PRONOC=z+ go onour honeymoon].

- Speaker A: I know I’m the only one who can do anything about thissituation, but I just don’t know [ForceP what to PRO do].Speaker B: I don’t either.(Can mean I don’t know what you (=Speaker A) should do either.)

As Reed (2014, p. 168) observes, the hypothesis that complementation type determines the relative distribution of OC and NOC not only immediately opens up a means of accommodating the fact that NOC can be attested in certain complement clauses, something that Landau’s two-tiered theory of control (TTC) precludes, but it also explains why OC clauses in languages like French and English can be headed by an overt Fin (de ‘of’ or à ‘at’), but never by an unambiguously overt head of CP (also known as ForceP) (i.e., que ‘that’).22 In addition, since CP/ForceP is standardly assumed to “constitute a phase,” this would lead one to expect it to block not only the type of complex chain formation Reuland uses to “set up” syntactic binding, but also OC. That is, one would expect ForceP to block any Agree-based process in a fashion akin to what has long been assumed, e.g., with respect to Accusative Case feature valuation of an argument in a complement clause by a matrix verb. In other words, it has been frequently claimed that what was originally termed “exceptionally case-marking” (ECM) is only possible if the complement clause is “smaller than” ForceP, as in (43a,b) below. Given this, one would expect the same to be true of complex chain formation since it too is implemented via Agree.

- (43)

- I made [vP them wait].

- *I made [ForceP that them wait].

We thus conclude that ForceP complementation precludes complex chain formation, i.e., it precludes the feature overwriting necessary for OC. This means that the types of Last Resort strategies Reuland appeals to in relation to the examples in (39)–(40) above are at work in examples involving NOC like those above in (42).

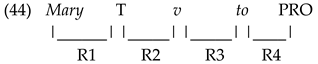

Returning to OC in (41), let us next make the standard assumptions that (a) there is agreement between finite matrix T and Mary that values the latter’s [u Case feature] and the former’s [u ϕ-features], and (b) matrix T agrees and creates a tense dependency with the matrix v, valuing the latter’s [tense] feature. We then make the novel assumptions that (a) matrix v agrees with the embedded T, valuing the latter’s [u tense feature], and (b) embedded T agrees with PRO, valuing the latter’s [u ϕ-features], overwriting them with those of the controller via complex chain formation.23 The PRD is respected since PRO is associated only with inherent categorial and non-expletive features that can be overwritten by those of Mary without any change in meaning. In short, we assume the four distinct agreement chains R1–R4 indicated below in (44). These compose to form a complex chain with overwriting of the features of PRO with those of Mary, in a fashion parallel to what Reuland proposes with respect to zich in examples like (37).

To accommodate object control in an example like (45), we need only make the further standard hypothesis that a transitive matrix verb undergoes agreement with its direct object, a hypothesis that has been previously substantiated in the literature by past participle agreement in languages like French. In (46), for example, the verb meaning painted overtly agrees in gender and number with its object, the pronoun that refers to les chaises ‘the chairs.’24

- (45)

- They always tell mex [to PROx try harder].

- (46)

- Les chaises, je les ai peintes.the chairs I them.fem.pl have painted.fem.pl‘As for the chairs, I painted them.’

Given this, a complex chain in an example like (45) has access to the ϕ-features of both the subject and the object. Therefore, either bundle could, theoretically, overwrite the feature bundle of PRO.25 Following a tradition that dates back to at least Manzini (1983, p. 423), it will be assumed here that both options are made available by the computational system, but one reading, in this case, the one involving subject control, is ruled out on purely semantic grounds in the fashion discussed at length by such authors as Sag and Pollard (1991) and Jackendoff and Culicover (2003).

Before demonstrating how this approach accommodates the problematic data introduced in Section 2, we close this one by briefly observing that this analysis, which is based on feature overwriting, immediately gains the advantages of movement approaches to control developed, e.g., in Bowers (1981); O’Neil (1995), and Hornstein (1999), among others, without suffering from their disadvantages. For example, it has been known since at least Lebeaux (1985, pp. 350–51) that PROOC requires a c-commanding antecedent, as made clear by the contrasts in (47a,b):

- (47)

- Mattx expects [to PROx do well on the exam].

- *Mattx’s sister expects [to PROx do well on the exam].

While movement approaches to control conclude that this fact is expected if control involves A-movement since the examples below in (48a,b) make it clear that the same contrasts obtain in that domain, it is equally expected under the present analysis since the matrix T/V complex agrees with Matt in (47a), but not in (47b). That is, we have followed Reuland in assuming that agreement sets up feature-overwriting. This means that PRO is the theoretical equivalent of a copy of Matt, so it is not unexpected that it exhibits characteristics of “true” copies, i.e., ones derived via movement.

- (48)

- Matt seemed [(Matt) to (Matt) do well on the exam].

- *Mattx’s sister seemed [(Matt) to (Matt) do well on the exam].

On the other hand, the present analysis does not suffer from certain problems that have been observed in the literature with respect to movement approaches to control. For example, feature-overwriting, unlike movement, obviously does not violate the minimal link condition in examples like (49), nor does an analysis based on Agree have to resort to pro to account for NOC in English examples like (50), nor is such an approach inherently unable to handle split control in examples like (51).26

- (49)

- I promised John [(I) to (I) bring the money].

- (50)

- John told Sam [how pro to hold oneself erect at a royal ball].

- (51)

- Maryx suggested to Billy [to PROx+y introduce themselves to the President].

4. Control and Passivization

With the proposal in place, it is now possible to return to the problematic data involving passivization and control introduced in Section 2. The reader will recall that the discussion there showed that the two-tiered theory of control (TTC) is currently unable to account for Visser’s Generalization (VG), exemplified by sentences like (2d) above. It incorrectly precludes non-obligatory control (NOC) in impersonal passives, such as (11) and (13) above. Finally, it can neither block the ungrammatical impersonal passives attested with certain attitude verbs, cf. (16a–c), nor generate the grammatical ones involving non-attitudes, as in (17a–j). Each of these areas will be considered in turn, beginning with how this analysis accounts for VG.

The present proposal associates an example like (2d) with a structure parallel to (52), which, it is important to note, follows Parsons (1990), Lasersohn (1993), Bruening (2013), and others in assuming, contra Landau (2010), that the understood thematic subject of a passive verb is entirely unrepresented at LF. In other words, it is being assumed here that the passive morphology essentially “deletes” the agent from a verb’s argument structure, although this argument remains interpretatively available via either meaning postulates (Lasersohn) or existential binding (Bruening).27

- (52)

- *Maryx was promised (Maryx) [FinP to PROx to call].

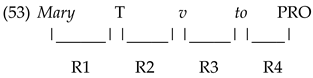

In this example, PRO enters the derivation with a bundle of unvalued ϕ-features. During the course of the derivation, (at least) the four agreement relations in (53) are established that lead to complex chain formation. Namely, finite matrix T agrees with Mary, valuing that NP’s [u Case feature] and T’s [u ϕ-features]; matrix T agrees and creates a tense dependency with the matrix v; matrix v agrees with the embedded T, valuing the latter’s [u tense feature]; and, finally, the embedded T agrees with PRO, ultimately valuing the latter’s [u ϕ-features] via a complex chain. The result of this derivation is that PRO is obligatorily interpreted as a copy of Mary, a reading that is semantically ill-formed, given the meaning of subject control promise. Since Rejection is Final, no pragmatic or purely semantic antecedent determination is possible and native speakers find the sentence ungrammatical.

Turning now to the lack of Visser’s effects in impersonal passives like (3a,b), these are associated with a structure parallel to (54):

- (54)

- It was agreed [ForceP [FinP to PRONOC establish a new nation on new principles]].

In (54), the embedded ForceP constitutes a phase that precludes any agreement between the matrix T/v complex and the embedded T. As a consequence, complex chain formation is not an option, which means that a context of NOC results. That is, PRO must resort to pragmatic strategies to establish its reference. Following Reed (2018a, 2018b), we assume that since a verb like agree designates its understood agent as its logophoric center, native speakers report that PRO “obligatorily” refers to that argument.28

Turning now to the NOC readings associated with sentences like (11) and (13), we note that these are associated with the representative structure in (55), which is, of course, parallel to (54):

- (55)

- I contacted the selection committee about how to submit my photo. It turns out thatit’s preferred (by the committeex) [ForceP [FinP to PRONOC submit in jpeg]].

In this example, the presence of ForceP again precludes the type of agreement into the embedded clause that is necessary for feature-overwriting, which means PRO’s reference is again pragmatically determined. The context in this sort of “atypical” example, however, strongly disfavors the usual reading in which the understood agent of a passive attitude verb serves as the controller. Namely, in (55), the agent of the matrix verb is a selection committee and such committees are rarely responsible for actually submitting photos to a candidate’s dossier. For this reason, we understood that the candidate, whoever that is, is expected to do so. A clearly NOC reading results.

Turning finally to the undergeneration problem associated with Dutch, French, and English examples of the type in (56) and that of overgeneration associated with ones parallel to (57) in French and English, we note that these can be easily accommodated by assuming the c-selectional differences in bold below:

- (56)

- It has been tried for some time now [ForceP [FinP to PRO put together a proposal167) that we can all live with]].

- (57)

- *Itx was threatened/loved/offered [FinP to PROx comment on the issue].

Namely, grammatical impersonal passivization is attested in Dutch, French, and English examples like (56) for the very reasons advanced in relation to (54): the embedded ForceP constitutes a phase that precludes agreement between the matrix T/v complex and the embedded T. Therefore, complex chain formation is blocked and PRO must resort to pragmatic strategies to establish its reference. Given the meaning of try, its understood agent is the most likely candidate since one cannot literally make an effort that directly results in someone else putting together a proposal.

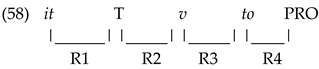

On the other hand, FinP complementation in (57) sets up the types of agreement relations associated with complex chain formation/OC in the manner discussed above in relation to (52), represented graphically below in (58). Given these relations, PRO is understood to essentially be a copy of expletive it, which clashes, semantically, with the agent theta-role assigned to PRO by the embedded verb comment. Since Rejection is Final, no alternative pragmatic means of establishing PRO’s reference can be appealed to and the result is ill-formed.

In sum, the discussion of this section has shown how a novel “single-tier” Agree-based approach to control can resolve significant issues that the TTC faces with respect to the structures in which control interacts with passivization. One strong point of this analysis is that it makes use of no mechanisms particular to control, employing only the standard minimalist notions Reuland (2011) used earlier to eliminate the separate “binding theory” of the government-binding (GB) era. PRO, under the present proposal, now falls rather neatly within the pronominal system of a language: It is simply a “minimal pronoun” subject to “Elsewhere” realization.

On the other hand, the aspect of the analysis that has not yet been shown “fall out” of any larger grammatical mechanism is its use of c-selection (ForceP vs. FinP) to account for key data. At this point, this may strike the reader as undesirable or suspicious since c-selection is generally viewed as arbitrary in nature, giving it a stipulative flavor.

There is, however, a long-standing and on-going accumulation of evidence supporting the view that complementation selection of the very type employed here does reduce, to a certain degree, to larger considerations that are primarily semantic in nature. The proposals in this paper can be shown to fit into and extend this body of work. For example, in a paper originally written in 1979, Noonan (2007) proposes that c-selection is a matter of pairing specific types of syntactic categories with specific semantic types of matrix verbs. In particular, cross-linguistic evidence indicates that it is generally the case that the stronger the semantic bond between the events described by a matrix and embedded predicate, the greater the degree of syntactic integration involved in the complement. More specifically, matrix verbs that uniquely select ForceP complements, i.e., clauses headed by that in English and que in French, are lowest on the scale of syntactic and semantic integration. In other words, the meaning of these verbs is such that they do not unequivocally determine various deictic categories in the complement clause, such as the latter’s tense markers or the reference of any pronouns it may contain.

This is illustrated below in (59a,b) in which the meaning of the utterance predicate mentioned determines neither the tense of the embedded T, nor the reference of the pronoun he. Simply put, one may make a statement about someone, including oneself, that was true in the past, is true now, or will be true in the future. There is no logical link between mentioning an event and its occurrence. This lack of semantic integration is reflected in or set up by the selection of a ForceP complement by the matrix verb.

- (59)

- Zekez mentioned that hez/j appeared in yesterday’s broadcast.

- Zekez mentioned that hez/j will be appearing tomorrow’s broadcast.

On the other hand, Noonan observes, verbs uniquely selecting for “smaller” syntactic complement types, such as FinPs involving infinitival to or reduced VP small clauses of the type I saw Bill leave, do make such determinations.29 The sentences below in (60a,b), for example, show that the meaning of caused is such that it determines the understood tense of its complement clause, as well as the potential reference of the embedded subject pronoun. In other words, the causal relation is such that the time of caused event cannot precede the time of the causing and the reference of him cannot be that of Zeke. C-selection for FinP syntactically sets this up these strong semantic bonds.

- (60)

- Zekez caused him!z/j to stumble yesterday.

- !Zeke caused him to stumble next week.

Particularly revealing, in this respect, are the verbs that Noonan (2007) observes can allow multiple complement types, such as believe in (61a,b):

- (61)

- I believe that Zeke is an idiot.

- I believe Zeke to be an idiot.

When believe selects a ForceP, as in (61a), there are no limitations on various deictic elements in the embedded sentence, as made clear with respect to tense (62a) below. However, when believe selects an embedded to-infinitival clause (FinP), as in (62b), the latter must be interpreted as holding at the same time as the matrix verb. Such multiple selection is possible because the meaning of believe, unlike cause, does not necessarily entail any specific temporal relationship between the matrix and embedded events, as is the case for cause. However, it does allow for one and, for this reason, non-integrated (ForceP) and integrated (FinP) options may, and in the case of believe do, exist.

- (62)

- I believe that Zeke is/was/will be an idiot.

- I believe Zeke to be an idiot !yesterday/!tomorrow.