The Reading and Writing Connections in Developing Overall L2 Literacy: A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Case of Portugal

1.2. The Need of Teacher Training for Teaching English to Young Learners in Portugal: What Should Be the Profile of Primary English Language Teachers?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Motivation for Developing Reading

2.2. Research Questions

- (1)

- To analyze to what extent the lack of appropriate teacher training opportunities for teaching young learners negatively impacts on primary school students’ English language reading and writing achievement?

- (2)

- To what extent is using picturebooks/storybooks effective in motivating young English language learners, thus having a positive impact in strengthening the connections in English language reading and writing?

3. Method

3.1. Context

3.2. Sites and Participants

Social science is fundamental to a democratic society, and should be inclusive of different interests, values, funders, methods and perspectives. This principle was achieved by implementing an action-research program in a low-SES setting, thus endowing children the opportunity to learn English and exposing them to the most recent trends for effect English language reading and writing development.

All social science should respect the privacy, autonomy, diversity, values and dignity of individuals, groups and communities. This was set by obtaining parental consent for the children to participate in the study, thus ensuring anonymity.

All social science should be conducted with integrity throughout, employing the most appropriate methods for the research purpose. As previously stated, the implemented approach was thought to be beneficial for the learners, and actually the results put in evidence outstanding qualitative progress in their ability to read and write.

All social science should aim to maximize benefit and minimize harm. By implementing the action-research plan in order to foster literacy development in the foreign language, we were actually making an attempt to counteract the damaging effects of poverty in literacy development.

3.3. Research Design and Classroom Observational Procedures: The Developed Qualitative Study

3.4. Describing the Study

Dear Zoo: A Lift-the-Flap Book (Rod Campbell)The Very Hungry Caterpillar (Eric Carle)The Gruffalo (Julia Donaldson and Alex Scheffler)The Grufalo’s Child (Julia Donaldson and Alex Scheffler)A Squash and a Squeeze ((Julia Donaldson and Alex Scheffler)Monkey Puzzle (Julia Donaldson)

- L1: “You know teacher, before I did not enjoy English, but now I do.”

- L2: “I like English too.”

- T: “Why?”

- L3: “You know, sometimes I say I do not like English, and before I did not, but now I do enjoy it and whenever I say I do not, I’m just joking”.

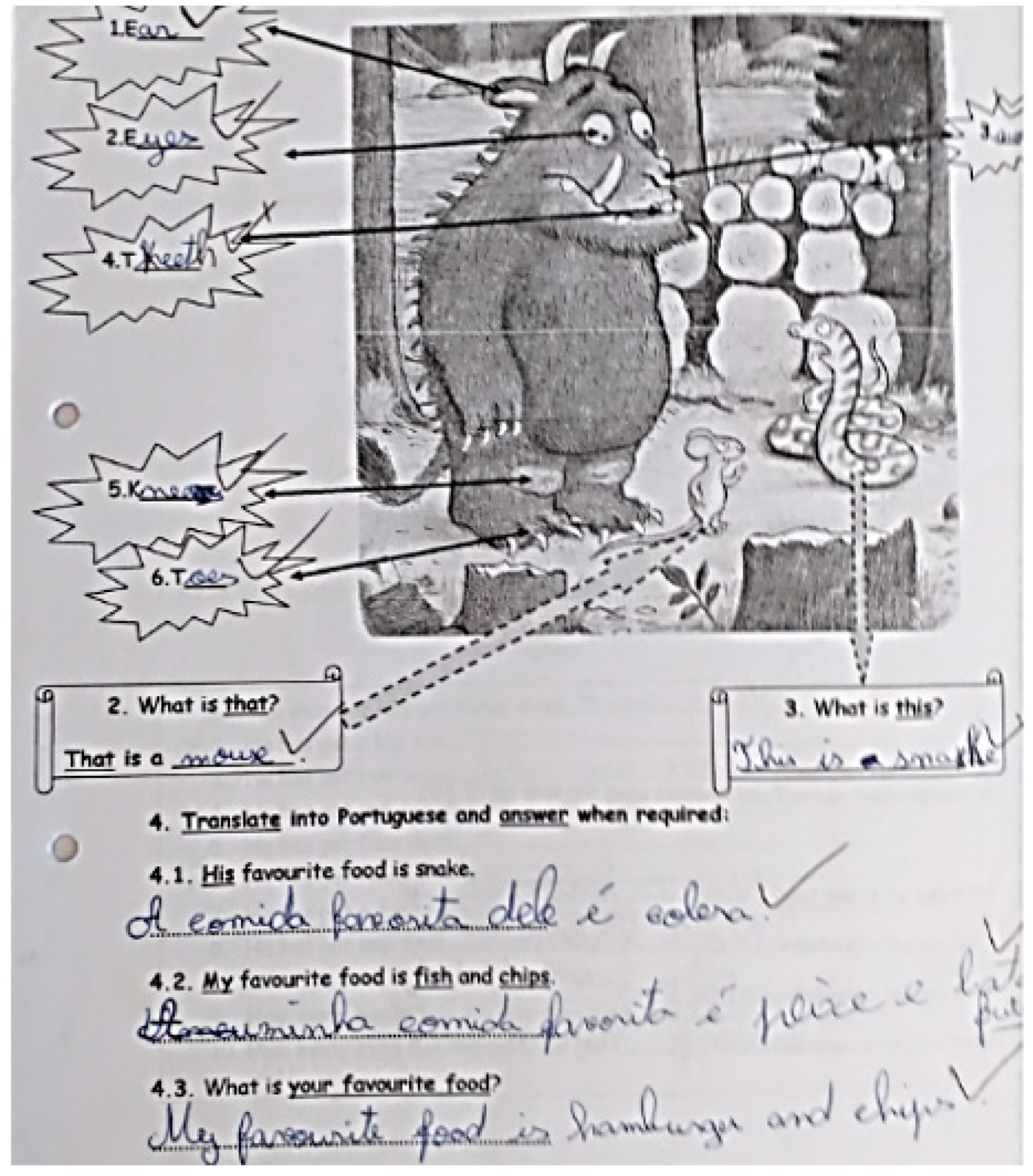

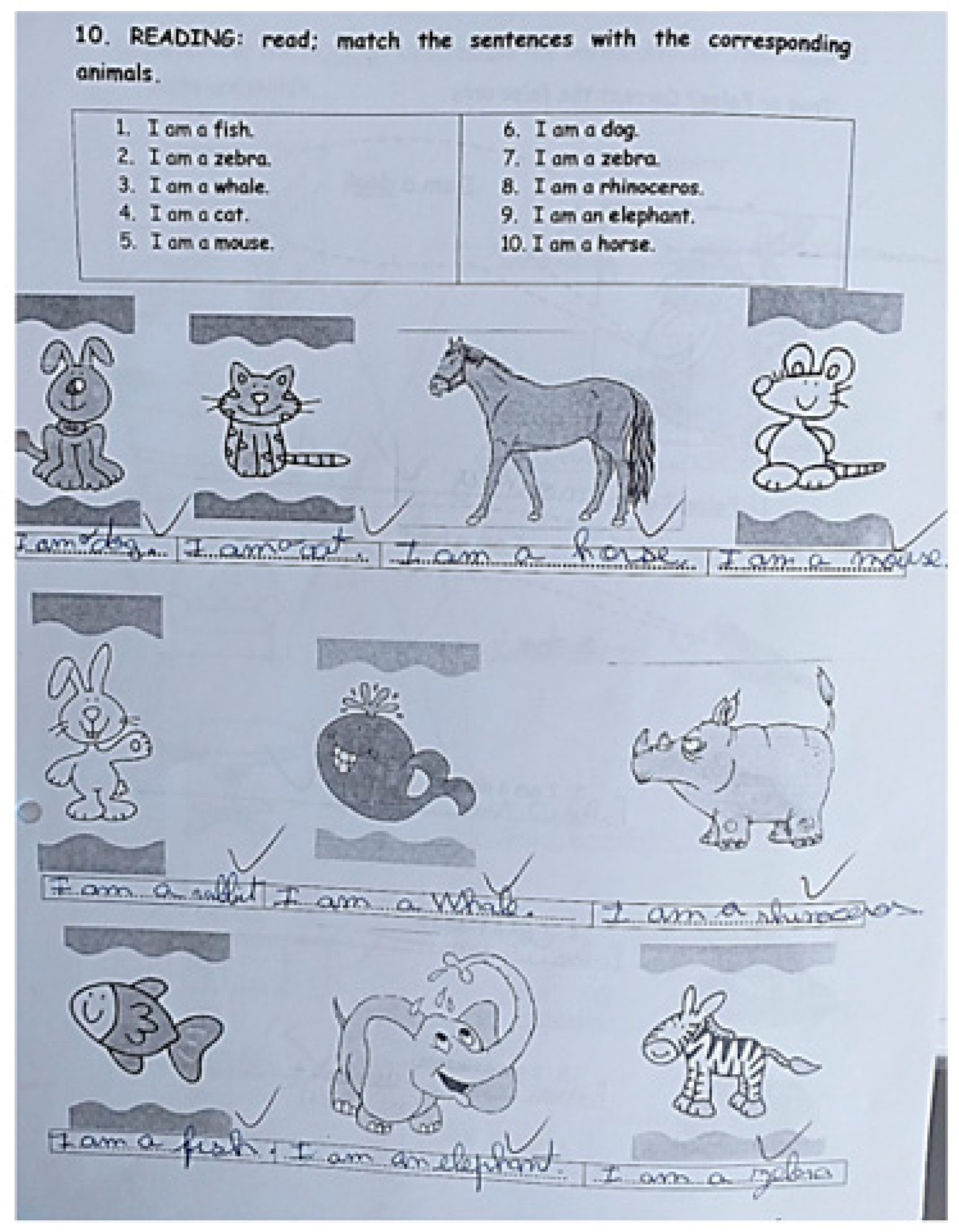

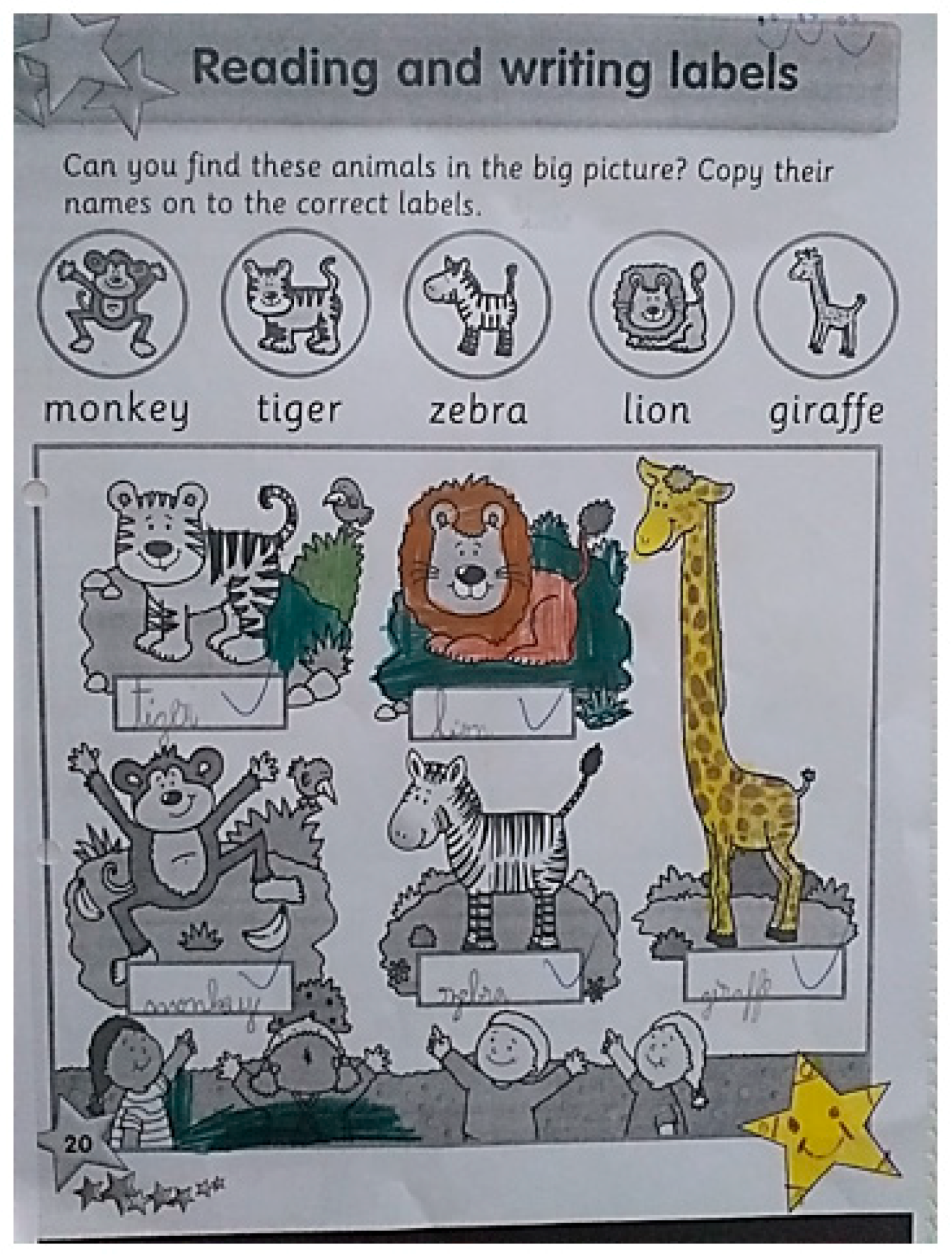

4. Findings

- (a)

- Initial EFL methodologies’ outcomes;

- (b)

- The effects of the use of storybooks and worksheets (EFL instructional material) in students’ reading and writing achievement;

- (c)

- Degree of learner active response/interaction/involvement.

- T: Now, Mrs. [author] is going to tell you a story about the animals, okay?

- About the Zoo, okay? So, I am going to start okay? So please listen, okay?

- T: ‘I wrote [T uses points to herself to explain ‘I’ and uses hand gestures to convey writing symbol] a letter to the Zoo. They sent me a... [and lifts the flap and shows the elephant] So, I wrote a letter.

- L [L1]: Say it in Portuguese.

- T: I wrote a letter [T picks up paper and pen and pretends writing as she speaks] 8 L [L1]: oh! You are writing.

- T: Yes! I wrote a letter to the Zoo to ask for a pet, an animal, okay?

- T: And they, the Zoo sent me an [T pauses a bit before uncovering the hidden animal] elephant. He was too big [T uses gestures and puts her hands above her 12 head]. He was too big, too big. [T places hand over her head to convey the meaning of big] 14 L [L1]: big!

- Classroom [L1]: too big.

- T: I sent him back [T uses right hand turning it to the right to convey the act of sending something away].

- L [L1]: you went away.

- Teacher: no, he, he [pointing to the animal picture] went away.

- L [L1]: he went away [points to herself again and conveys act of sending away].

- T: I sent him back, yes!

- T: So the Zoo sent me a? [T uses a sort o question emphasis before revealing the animal] giraffe!

- Learners [L2]: Giraffe!

- T: He was too tall. [T lifts up her feet and puts her hands above her head, showing her hand above her height]. Too tall.

- Classroom [L1]: Too big. Bigger.

- I sent him back.

- L [L1]: he went away.

- T: So they sent me a? [lifts book flap and waits for learners’ answers]. 32 L [L1]: lion, lion.

- T: Lion (rises her voice tone)! He was too fierce [T changes her voice tone to a more aggressive one, extends her hand pretending the lions’ claws and imitates lion’s sound when angry at the same time- grrr). Too fierce [T repeats same procedure].

- L [L1]: he was evil.

- T: Yes. He was too fierce. I sent him back.

- L [L1]: he went away again.

- T: So the Zoo sent me a?…

- Classroom [L1]: camel! Camel!

- T: a camel!

- Classroom [L2]: camel!

- T: a camel!

- Classroom [L2]: a camel!

- T: he was too grumpy! [T crosses her arms and pretends a grumpy face]. Too grumpy. Too grumpy.

- Classroom [L1]: irritable.

- T: Yes, too grumpy. I sent him back.

- Classroom [L1]: he went away.

- T: Yes. So they sent me a?

- Classroom [L1]: snake!

- T: snake!

- Classroom [L1]: teacher, you know we have seen a snake here in our school and we killed her. Yeah, she went from this life for a better one. She was poisonous.

- T: So they sent me a snake. She was too scary. So I sent him back. They sent me a?

- Classroom [L1]: monkey! Monkey!

- T: Monkey! But he was too naughty [T laughs, changes on voice-tone and 61 pretends to be making fun of something, stealing learners’ notebooks to convey the meaning of naughty].

- Classroom [L1]: bad behaved. 64 L [L1]: he won’t steal my stuff!

- T: Yes, naughty. The monkey was very naughty. The monkey was too naughty. I sent him back.

- T: So they sent me a?

- L [L1]: frog.

- T: frog. But he was too jumpy [T pretends small jumps]. So I sent him back.

- L [L1]: he’s gone.

- T: In English!

- T/Classroom: I sent him back.

- T: So at the Zoo they thought and thought and thought [T points with one finger to her head making small circles] and sent me a?

- Classroom [L2]: Dog!

- T: Dog! He was perfect. I kept him [T joins her arms as she was preparing

- herself to hug a baby to suggest withholding something in a caring way].

- T: So, did you like the story? Did you like the story? [Teacher smiles to convey the verb like and points to the storybook]

- Classroom [L1]: Yes!

- (…) 13:16–story review

- T: So, what animal would you like? Would you like the monkey, the elephant, the giraffe, the lion, the camel or the snake? Which animal would you like

- [points to learner]?

- L [L2]: elephant

4.1. The EFL Questionnaire Application

4.2. The EFL Questionnaire Results

4.2.1. Reasons for learning English

4.2.2. Changes in Learners’ Assessment

4.3. The Leuven Involvement Scale

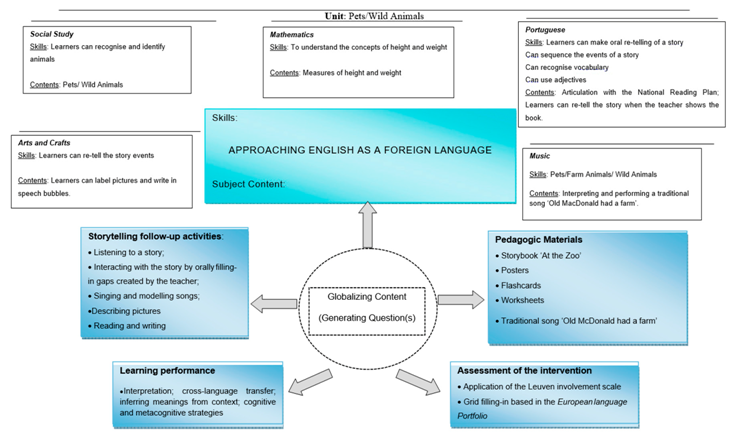

5. Content for Language and Integrated Learning (CLIL), through English across the Curriculum

5.1. Authentic Storybooks and Narration

- L1: “You know teacher, before I did not enjoy English, but now I do.”

- L2: “I like English too.”

- T: “Why?”

- L1: “I don’t know, I just know I enjoy it now.”

- L3: “You know, sometimes I say I do not like English, and before I did not, but now I do enjoy it and whenever I say I do not, I’m just joking.”

5.2. The Multilingual School Play

6. Discussion

(1) To observe the implementation of the initial national strategy for teaching English to young learners in Portuguese primary schools, in association with the lack of suitable teacher training opportunities;

(2) To analyze the effects of an action-research plan, based on a reading intervention program (resorting to picturebooks/storybooks) to foster the connections between reading and writing in English.

7. Implications

- Children’s literature, cartoons, strategies resorting to language play (i.e., drama, pretend-play, music) are powerful pedagogic tools to use whenever possible with young learners, especially economically disadvantaged children. In terms of storybooks, besides their motivational interactive nature and being authentic sources of the language, they allow cross-curricular work with primary key curriculum themes, thus enhancing meaningful learning. Children’s literature assists as an outstanding vehicle to help second language reading and writing, from ages as young as 6 years old.

- As well as children from mid- and high-SES, children from low-SES areas should also be entitled to democratic L2 reading and writing practices and endowed with “learning how to learn” skills.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Key Principles of Content for Language and Integrated Learning (CLIL)

| Key Principles of Content for Language and Integrated Learning (CLIL) | |

| 1 | Additional-language instruction is more effective when integrated with content instruction |

| 2 | Explicit and systematic language instruction is important |

| 3 | Student engagement is the engine of learning |

| 4 | Both languages should have equally high status |

| 5 | The fisrt language can be a useful tool for learning the additional language and new academic knowledge and skills |

| 6 | Classroom-based assessment is critical for programme success |

| 7 | All children can become bilingual |

| 8 | Strong leadership is critical for successful dual-language teaching |

Appendix B. Design of a Cross-Curricular Approach to Teach Second Language Reading and Writing

Appendix C. (Translated into English). English in Primary State Schools—1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Grades

References

- Al-Mansour, Nasser Saleh, and Ra’ed Abdulgader Al-Shorman. 2011. The effect of teacher’s storytelling aloud on the reading comprehension of Saudi elementary stage students. Journal of King Saud University-Languages and Translation 23: 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Momani, Ibrahim A., Fathi M. Ihmeideh, and Abdallah M. Abu Naba’h. 2010. Teaching Reading in the early years: Exploring home and kindergarten relationships. Early Child Development and Care 180: 767–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aram, Dorit, and Shira Biron. 2004. Joint storybook reading and joint writing interventions among low-SES preschoolers: Differential contributions to early literacy. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 19: 588–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, Arda, and Hayriye Taraf. 2010. Contextualizing young learners’ English lessons with cartoons: Focus on grammar and vocabulary. Procedia Social Behavioural Sciences 2: 5212–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, Diane, and Timothy Shanahan. 2006. Developing Literacy in Second-Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers Mahwah. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, Robert C., and Sari K. Biklen. 1998. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Boudersa, Nassira. 2016. The Importance of Teachers’ Training Programs and Professional Development in the Algerian Educational Context: Toward Informed and Effective Teaching Practices. Expériences Pédagogiques. Available online: http://exp-pedago.ens-oran.dz (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- British Educational Research Association. 2018. BERA’s Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. PE Scholar, UK. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Burstall, Claire. 1975a. Factors affecting foreign-language learning: A consideration of some research findings. Language Teaching and Linguistics: Abstracts 8: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstall, Claire. 1975b. French in the primary school: The British experiment. Canadian Modern Language Review 31: 388–402. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel, Rivi. 2019. Parents’ discourse on English for young learners. In Language Teaching Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copland, Fiona, Sue Garton, and Anne Burns. 2014. Challenges in Teaching English to Young Learners: Global Perspectives and Local Realities. TESOL Quarterly 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 1995. White Paper on Education and Training. Teaching and Learning towards the Learning Society. Available online: www.europa.eu/documents/comm/white_papers pdf/com95_590_en.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2010).

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Language: Teaching, Learning, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2004. Promoting language learning and linguistic diversity 2004–2006: An action plan 2004–2006. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. ISBN 92-894-6626-X. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2007. Guide for the Development of Language Education Policies in Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2010. White Paper on Intercultural Dialogue. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online: www.coe.int/t/dg4/intercultural/Source/White%20Paper_final_revised_EN. pdf (accessed on 5 June 2010).

- Coyle, Do, and Philip Hood. 2010. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creese, Angela. 2005. Is this content-based language teaching? Linguistics and Education 16: 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, David. 2003. English as a Global Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csizér, Katya, and Zoltán Dörnyei. 2005. The internal structure of language learning motivation and its relationship with language choice and learning effort. The Modern Language Journal 89: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Jim. 1991. Interdependence of first- and second-language proficiency in bilingual children. In Language Processing in Bilingual Children. Edited by Ellen Bialystok. Cambrige: Cambridge University Press, pp. 70–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2006. Identity texts: The imaginative construction of self through multiliteracies pedagogy. In Imaging Multilingual Schools: Languages in Education and Glocalization. Edited by O. Garcia, T. Skutnabb-Kangas and M.E. Torres-Guzmán. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Mary A. 2013. Clay’s Theoretical Perspective: A Literacy Processing Theory. In Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading, 6th ed. Edited by Donna Alvermman, Norman Unrau and Robert Rudell. Newark: International Reading Associations, pp. 636–56. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, Nell, Victoria Purcell-Gates, Leigh Hall, and Cathy Tower. 2006. Authentic Literacy Activities for Developing Comprehension and Writing. The Reading Teacher 60: 344–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Gail, and Jean Brewster. 2014. Tell it Again! The Storytelling Handbook for Primary Teachers, 3rd ed. London: British Council. [Google Scholar]

- Enever, Janet. 2011. ELLiE Early Language Learning in Europe. London: British Council. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, Kathryn, and Elaine Reese. 2005. Picture book reading with young children: A conceptual framework. Developmental Review 25: 64–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, Raquel J. 2014. O Desenvolvimento das Competências de Leitura e Escrita no Ensino Pré-Escolar—O Contributo da Consciência Fonológica. Mestrado em Didática da Língua Portuguesa, Escola Superior de Educação, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, Richard. 2010. Raising Confident Readers: How to Teach Your Child to Read and Write-from Baby to Age 7. Boston: Lifelong Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gobël, Kerstin, and Andreas Helmke. 2010. Intercultural learning in English as foreign language instruction: The importance of teachers’ intercultural experience and the usefulness of precise instructional directives. Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 1571–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helot, Christine, and Andrea Young. 2006. Imagining Multilingual Education in France: A Language and Cultural Awareness Project at Primary Level. Imagining Multilingual Schools Multilingual Matters, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Becky H. 2016. A synthesis of empirical research on the linguistic outcomes of early foreign language instruction. International Journal of Multilingualism 13: 257–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jared, Debra, Pierre Cormier, Bethy A. Levy, and Lesly Wade-Woolley. 2011. Early predictors of biliteracy development in children in French immersion: A 4-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology 103: 119–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, Laura, Joan Kaderavek, Xitao Fan, and Aileen Hunt. 2009. Accelerating Preschoolers’ Early Literacy Development Through Classroom-Based Teacher–Child Storybook Reading and Explicit Print Referencing. Journal Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 40: 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korat, Ofra. 2005. Contextual and non-contextual knowledge in emergent literacy development: A comparison between children from low SES and middle SES communities. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 20: 220–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laevers, Ferre. 1994. The Leuven Involvement Scale for Young Children LIS-YC. Manual: Centre for Experiential Education. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Carmen, Philip Hood, and Doreen Coyle. 2020. Blossoming in English: Preschool Children’s Emergent Literacy Skills in English. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, Donald, Bessie Dendrinos, and Panayota Gounari. 2006. A Hegemonia da Língua Inglesa. Edições Pedagogo. Porto: Editora Bertrand. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, Peter D., Susan C. Baker, Richard Clément, and Sarah Conrod. 2001. Willingness to communicate, social support and language learning orientations of immersion students. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 23: 369–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, Peter D., Susan C. Baker, Richard Clément, and Leslie A. Donovan. 2003. Talking in order to learn: Willingness to communicate and intensive language programs. Canadian Modern Language Review 59: 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, Peter, Rcihard Clément, Zoltán Dörnyei, and Kimberly Noels. 2012. A Conceptualizing Willingness to Communicate in a L2: A Situational Model of L2 Confidence and Affiliation. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Mehigan, Gene. 2020. Effects of Fluency Oriented Instruction on Reading Achievement and Motivation among Struggling Readers in First Class in Irish Primary Schools. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Education, Faculty of Arts, National University of Ireland, University College, Cork, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, B. Mathew, and A. Michael Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. 2005. Programa de Generalização de Inglês no Ensino Básico–3.º e 4.º anos de Escolaridade. Portugal [Programme for the Generalization of English in Primary Schools-3rd and 4th Years of Schooling]. Available online: http://www.mne.gov.pt/Portal/PT/Governos_Constitucionais/GC17/ME/Comunicacao/Outros_Documentos/20050705_ME_Doc_Ingles_Basico.htm (accessed on 10 November 2005).

- Ministry of Education. 2006. Programa de Generalização de Inglês no Ensino Básico–1.º e 2.º anos de Escolaridade. Portugal. [Programme for the Generalization of English in Primary Schools–1st and 2nd Years of Schooling]. Despacho n.º 12 590/2006. Diário da República n.º115, II série (). Portuguese Law no 12 590/2006 Diary of Republic no 115, II Series. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Basico/AEC/desp_12591_2006.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2005).

- Ministry of Education. 2018. Inglês: Documentos Curriculares de Referência. Available online: https://www.dge.mec.pt/ingles (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Mourão, Sandie. 2015a. Learning English Is Child’s Play—How to Leave Them to It. Voices. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/learning-english-childs-play (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Mourão, Sandie. 2015b. The potential of picturebooks with young learners. In Teaching English to Young Learners. Critical Issues in Language Teaching with 3–12 years old. Edited by J. Bland. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Mourão, Sandie, and Sónia Ferreirinha. 2016. Early language learning in Portugal. Unpublished Report. Available online: http://www.appi.pt/activeapp/wpcontent/uploads/2016/07/Pre-primary-survey-report-July-FINAL-rev.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Mourão, Sandie, and Mónica Lourenço. 2015. Early Years Second Language Education: International Perspectives on Theories and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Susan. 2016. Opportunities to Learn Give Children a Fighting Chance. Journal Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice 65: 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolov, Marianne. 1999. ‘Why do you learn English?’ ‘Because the teacher is short.’ A study of Hungarian children’s foreign language learning motivation. Language Teaching Research 3: 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunan, David. 1999. Second Language Teaching and Learning. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, Luís. 2011. A Formação de Professores de Inglês para o 1º Ciclo do Ensino Básico. Tese de Doutoramento, Departamento de Artes e Letras, Universidade da Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Piasta, Shayne, Laura Justice, Anita S. McGinty, and Joan Kaderavek. 2012. Increasing Young Children’s Contact with Print During Shared Reading: Longitudinal Effects on Literacy Achievement. Journal Child Development 83: 810–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinter, Annamaria. 2006. Teaching Young Language Learners (Oxford Handbooks for Language Teachers). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell-Gates, Victoria, Nell Duke, and Joseph Martineau. 2007. Learning to Read and Write Genre-Specific Text: Roles of Authentic Experience and Explicit Teaching. Reading Research Quarterly 42: 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchey, Kristen, and Deborah L. Speece. 2006. From Letter Names to Word Reading: The Nascent Role of Sublexical Fluency. Contemporary Educational Psychology 31: 301–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, Damian, and Brian Mcmillan. 2011. The Practice of Policy: Teacher Attitudes toward “English Only”. System 39: 251–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, David, and J. R. Martin. 2012. Learning to Write, Reading to Learn: Genre, Knowledge and Pedagogy in the Sydney School. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Saracho, Olivia, and Bernanrd Spodek. 2010. Parents and children engaging in storybook reading. Journal Early Child Development and Care 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Maria V. 2012. Gêneros textuais e ensino-aprendizagem de línguas: um estudo sobre as crenças de alunos-professores de Letras/Língua Inglesa. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística Aplicada), Universidade Estadual do Ceará, Ceará, Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sulzby, Elizabeth. 1992. Transitions from Emergent to Conventional Writing (Research Directions). Language Arts 69: 290–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum, Michal, and Limor Tahar. 2008. Willingness to communicate in the language of the other: Jewish and Arab students in Israel. Learning and Instruction 18: 283–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Barbara, Debra Pearson, and Michael Rodriguez. 2003. Reading Growth in High-Poverty Classrooms: The Influence of Teacher Practices That Encourage Cognitive Engagement in Literacy Learning. The Elementary School Journal 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, Efleda, and Lauren Lawson. 2015. ‘Well, we’re going to kindergarten, so we’re gonna need business cards!’: A story of preschool emergent readers and writers and the transformation of identity. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 17: 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiman, Rebecca. 2005. Knowledge about letters as a foundation for reading and spelling. In Handbook of Orthography and Literacy. Edited by M.R. Joshi and G.P. Aaron. Mahwah: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Treiman, Rebecca, and Victor Broderick. 1998. What’s in a name? Children’s knowledge of letters in their own names. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 70: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiman, Rebecca, Ruth Tincoff, Kira Rodriguez, Angeliki Mouzaki, and D.J. Francis. 1998. The foundations of literacy: Learning the sounds of letters. Child Development 69: 1524–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treiman, Rebecca, Brett Kessler, Tatiana C. Pollo, Brian Byrne, and Richard K. Olson. 2016. Measures of kindergarten spelling and their relations to later spelling performance. Scientific Studies of Reading 20: 349–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unsworth, Len, and Kathy Mills. 2018. Multimodal Literacy. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vee, Harris. 2008. A cross-curricular approach to ‘learning to learn’ languages: Government policy and practice. Curriculum Journal 19: 255–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes Cambridge, Mass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wedin, Asa. 2010. Wedin, Asa 2010. Narration in Swedish pre and primary school: A resource for language development and multilingualism. Language, Culture and Curriculum 23: 219–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, Hsueh-Yin, and Zhu Hua. 2010. The phonological development of a trilingual child. International Journal of Bilingualism 14: 105–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesil-Dagli, Ummuhan. 2011. Predicting ELL Students’ Beginning First Grade English Oral Reading Fluency from Initial Kindergarten Vocabulary, Letter Naming, and Phonological Awareness Skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 26: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, Yen Na, Neil Cohn, and Way Kwok-Wai Lau. 2021. Effects of picture-word integration on reading visual narratives in L1 and L2. Journal Learning and Instruction 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jianying, and Jiren Liu. 2018. The Effects of Extensive Reading on English Vocabulary Learning: A Meta-analysis. Journal English Language Teaching 11: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Well-Being | Signals |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Extremely low | The child clearly shows signs of discomfort such as crying or screaming. They may look dejected, sad, frightened or angry. The child does not respond to the environment, avoids contact and is withdrawn. The child may behave aggressively, hurting him/ herself or others. |

| 2 | Low | The posture, facial expression and actions indicate that the child does not feel at ease. However, the signals are less explicit than under level 1 or the sense of discomfort is not expressed the whole time. |

| 3 | Moderate | The child has a neutral posture. Facial expression and posture show little or no emotion. There are no signs indicating sadness or pleasure, comfort or discomfort. |

| 4 | High | The child shows obvious signs of satisfaction (as listed under level 5). However, these signals are not constantly present with the same intensity. |

| 5 | Extremely high | The child looks happy and cheerful, smiles, cries out with pleasure. They may be lively and full of energy. Actions can be spontaneous and expressive. The child may talk to him/herself, play with sounds, hum, sing. The child appears relaxed and does not show any signs of stress or tension. He/she is open and accessible to the environment. The child expressed self-confidence and self-assurance. |

| OBJECTIVES | Activities | CONTENTS | Projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learners: | Learners: | Lexis: relevant vocabulary related to the topic–Pets/Wild animals * (depending on the social setting teacher must be aware that learners might not be familiar with all the vocabulary in their native language.) Expressing feelings Cross-curricular links: Social Study by | |

| Speaking

|

| |

| Listening

| ||

| |||

| Speaking

| ||

|

| ||

| Writing

| ||

| question and answer —“hello, how are you?” E.g., “I’m sad”, etc.

| discussing Pets/Wild Animals; Endangered species Literacy–describing animals by using adjectives (“too tall”: “too fierce”,…) | |

| Listening

| ||

| Speaking

| ||

| can justify the animal choice | ||

Listening

| |||

| Speaking | |||

| Photocopies | ||

| Worksheet |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lucas, C. The Reading and Writing Connections in Developing Overall L2 Literacy: A Case Study. Languages 2020, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040069

Lucas C. The Reading and Writing Connections in Developing Overall L2 Literacy: A Case Study. Languages. 2020; 5(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleLucas, Carmen. 2020. "The Reading and Writing Connections in Developing Overall L2 Literacy: A Case Study" Languages 5, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040069

APA StyleLucas, C. (2020). The Reading and Writing Connections in Developing Overall L2 Literacy: A Case Study. Languages, 5(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040069