Gender in Unilingual and Mixed Speech of Spanish Heritage Speakers in The Netherlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Grammatical Gender

2.1. Gender in Dutch

2.2. Gender in Spanish

3. Previous Literature

3.1. Dutch and Spanish Gender in the Speech of Heritage Bilinguals

3.2. Dutch and Spanish Gender in Code-Switched Speech

- esto es un pequeño pocket‘this is a small pocket’[Sastre 1, *KEV] (http://bangortalk.org.uk/speakers.php?c=miami)

- 2.

- a. el table‘the.m table’b. la table‘the.f table’c. la umbrella‘the.f umbrella’

4. Research Questions and Hypotheses

5. Methodology

5.1. Materials

5.2. Procedure

5.3. Participants

5.4. Coding

6. Results

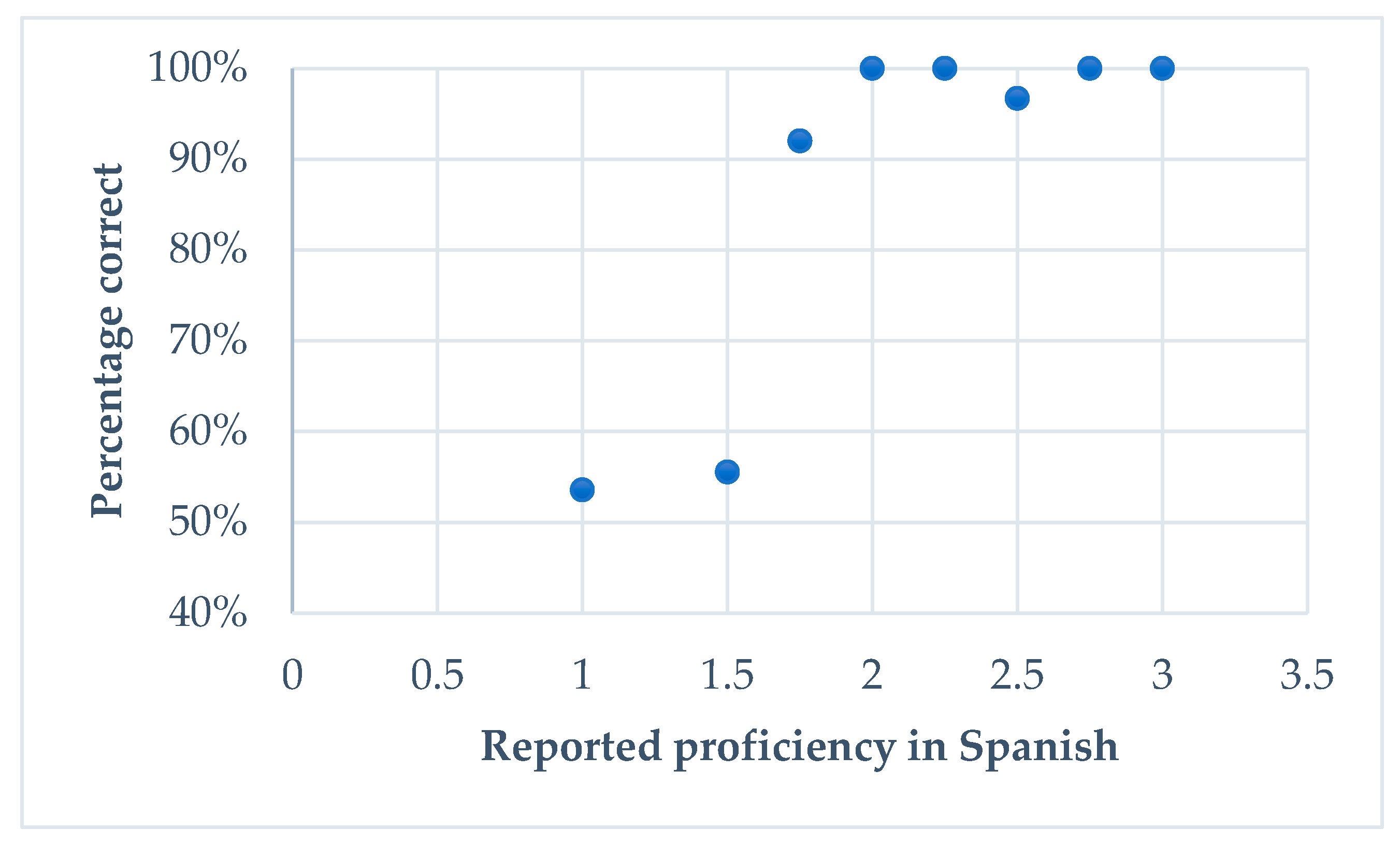

6.1. Unilingual Spanish

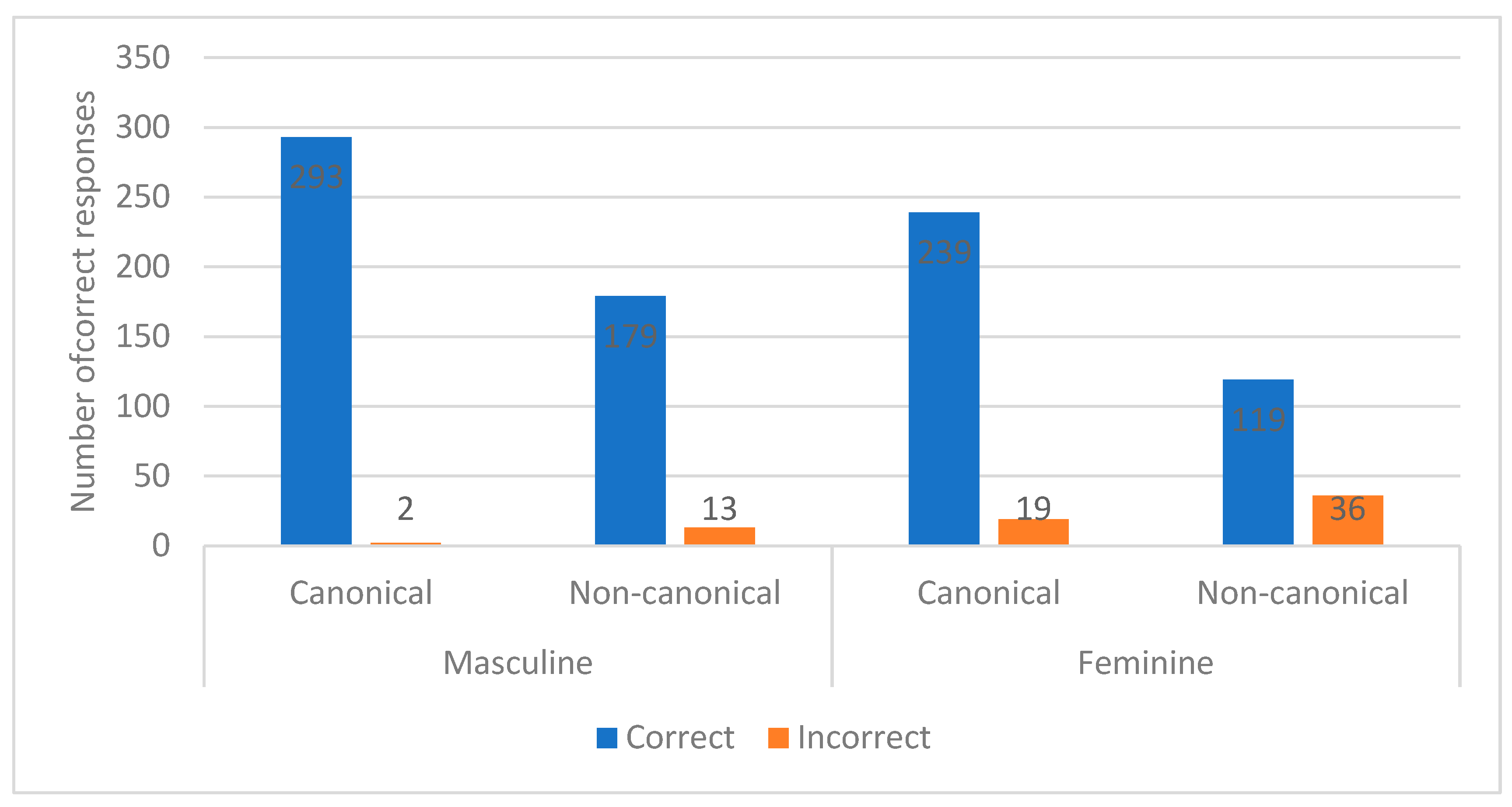

6.1.1. Linguistic Variables

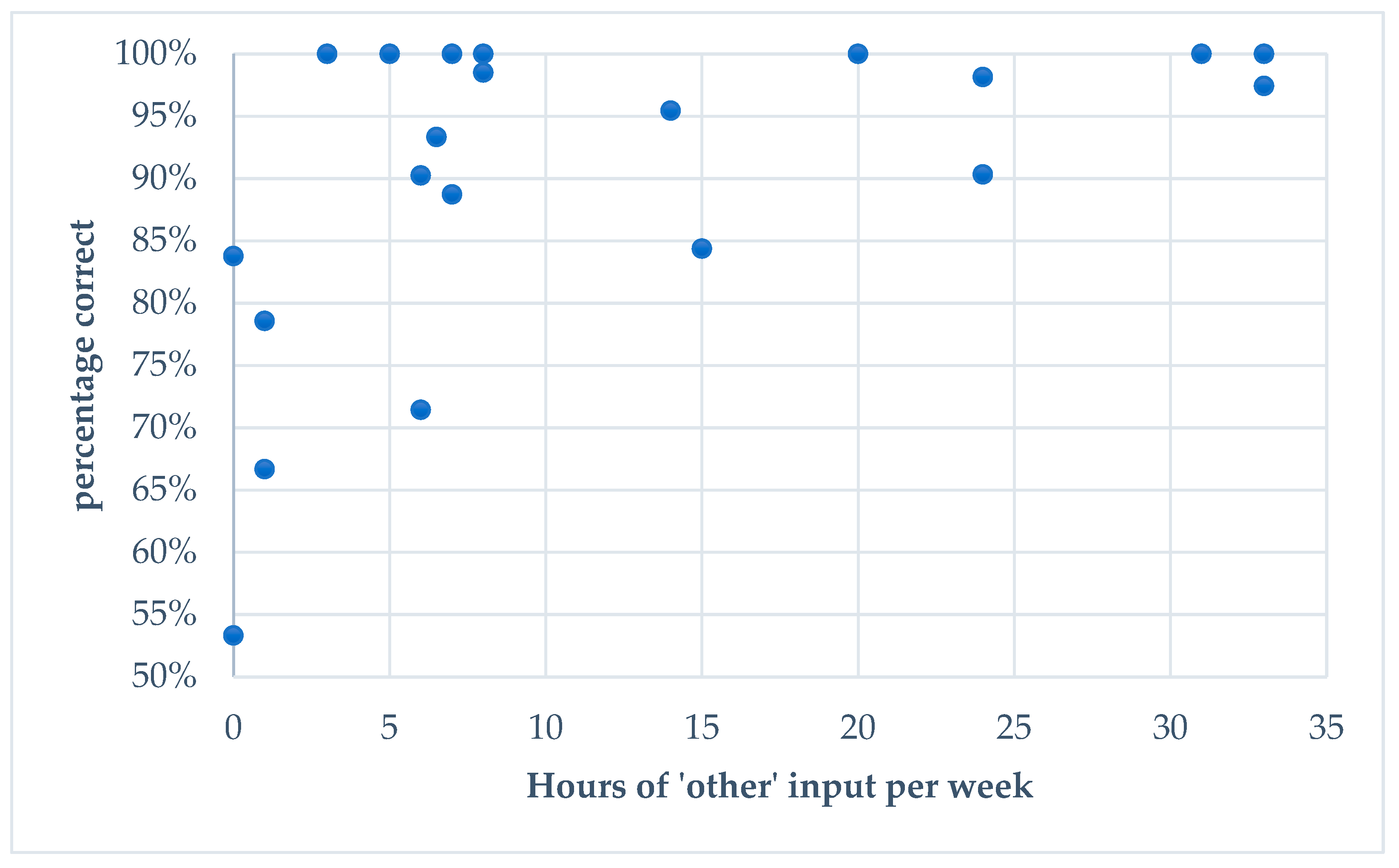

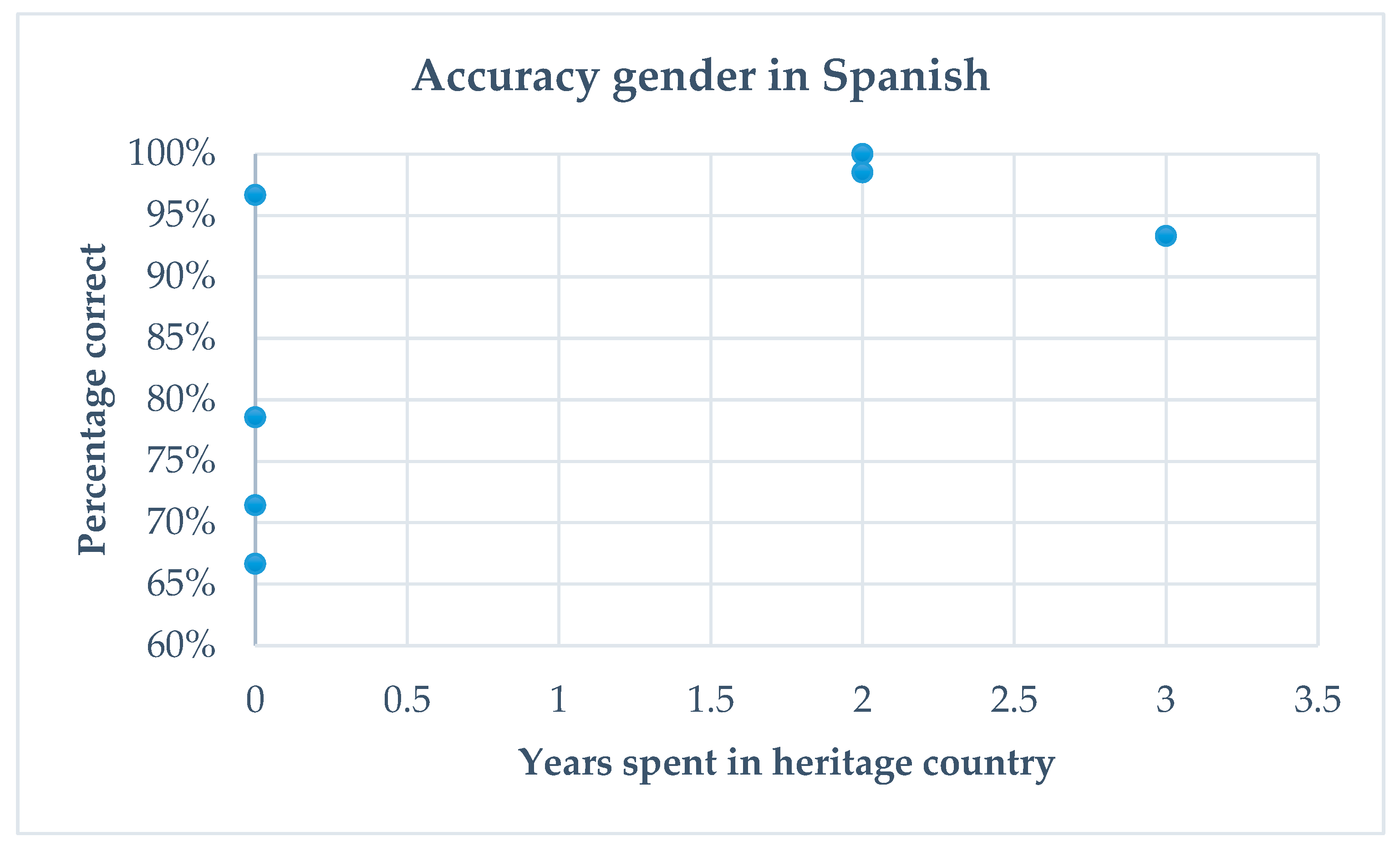

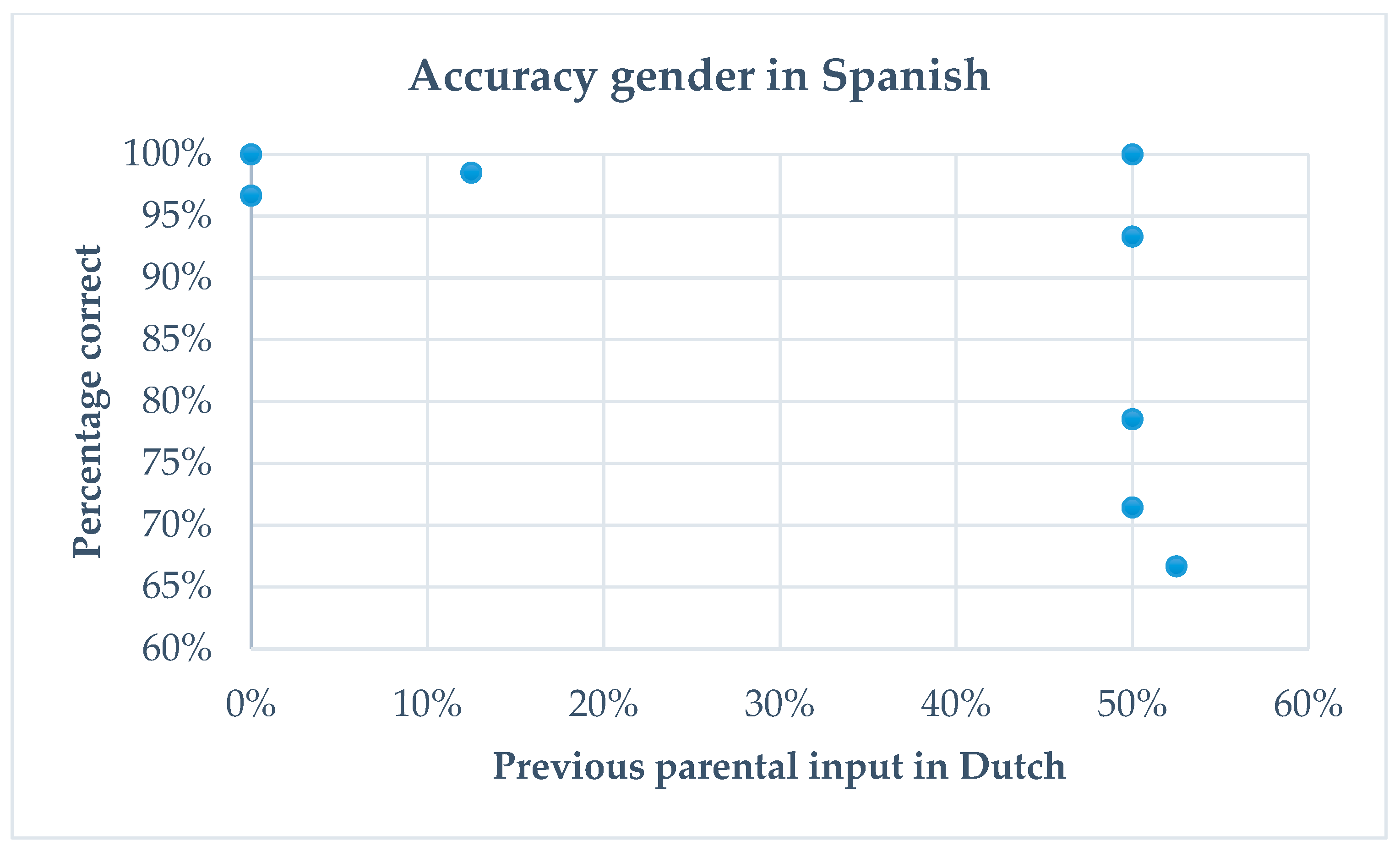

6.1.2. Extralinguistic Variables

6.2. Unilingual Dutch

6.2.1. Linguistic Variables

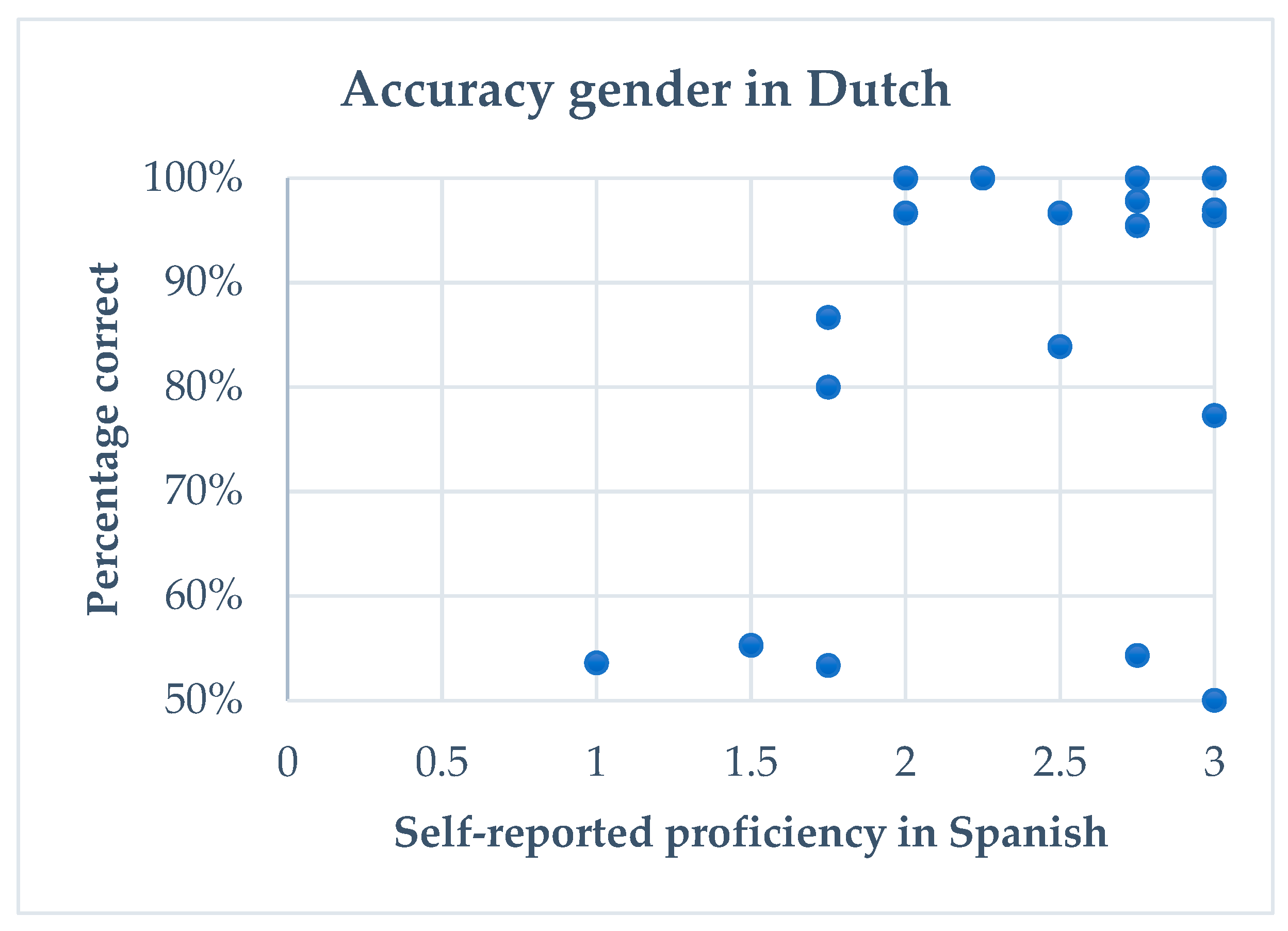

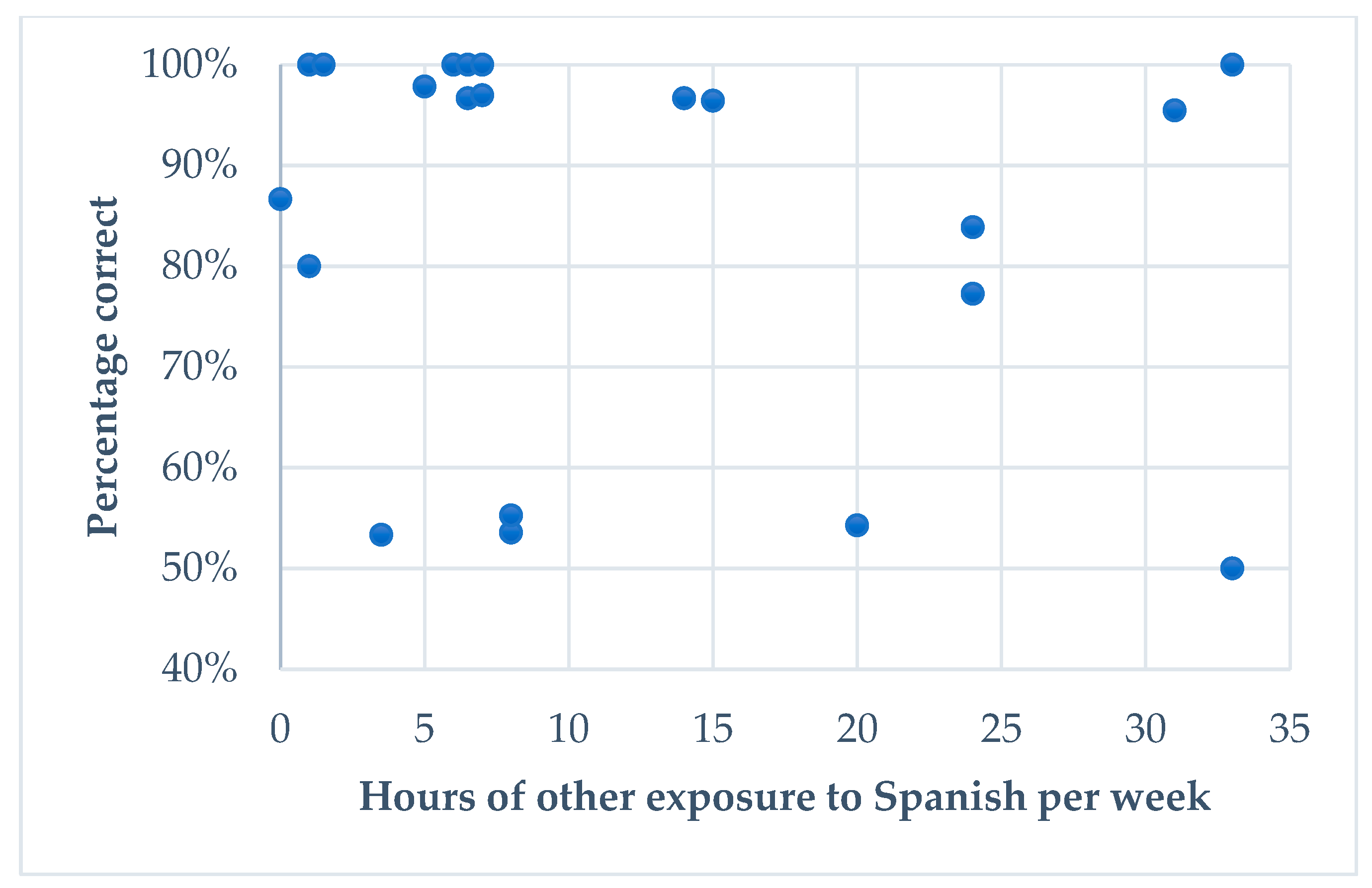

6.2.2. Extralinguistic Variables

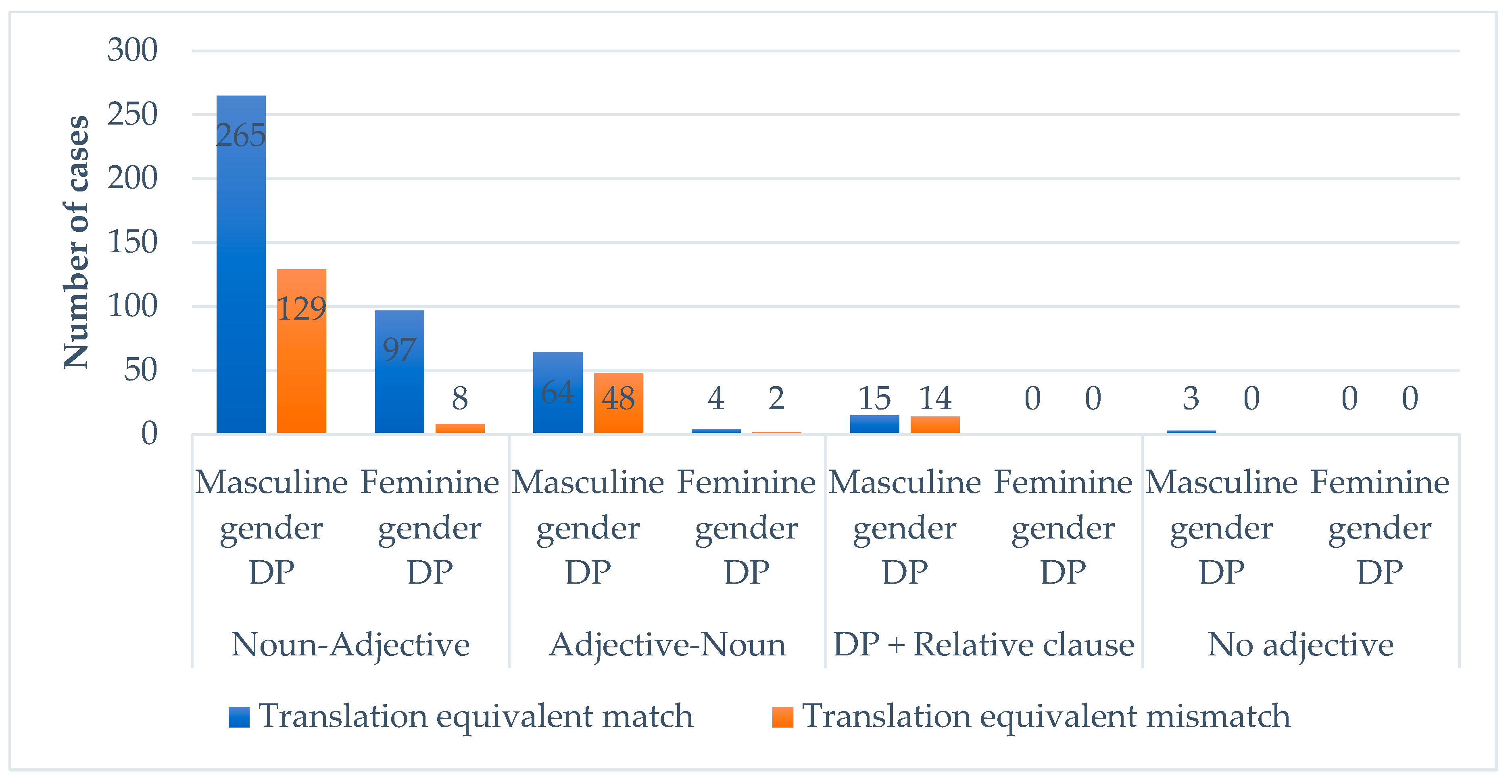

6.3. Code-Switched Speech

6.3.1. Spanish-Dutch Mode

6.3.2. Spanish-Dutch Mode—Individual Differences between Participants

- Masculine default strategy.

- Feminine default strategy.

- Analogical gender strategy.

- Prenominal adjective—masculine default.

- DP with relative clause—masculine default.

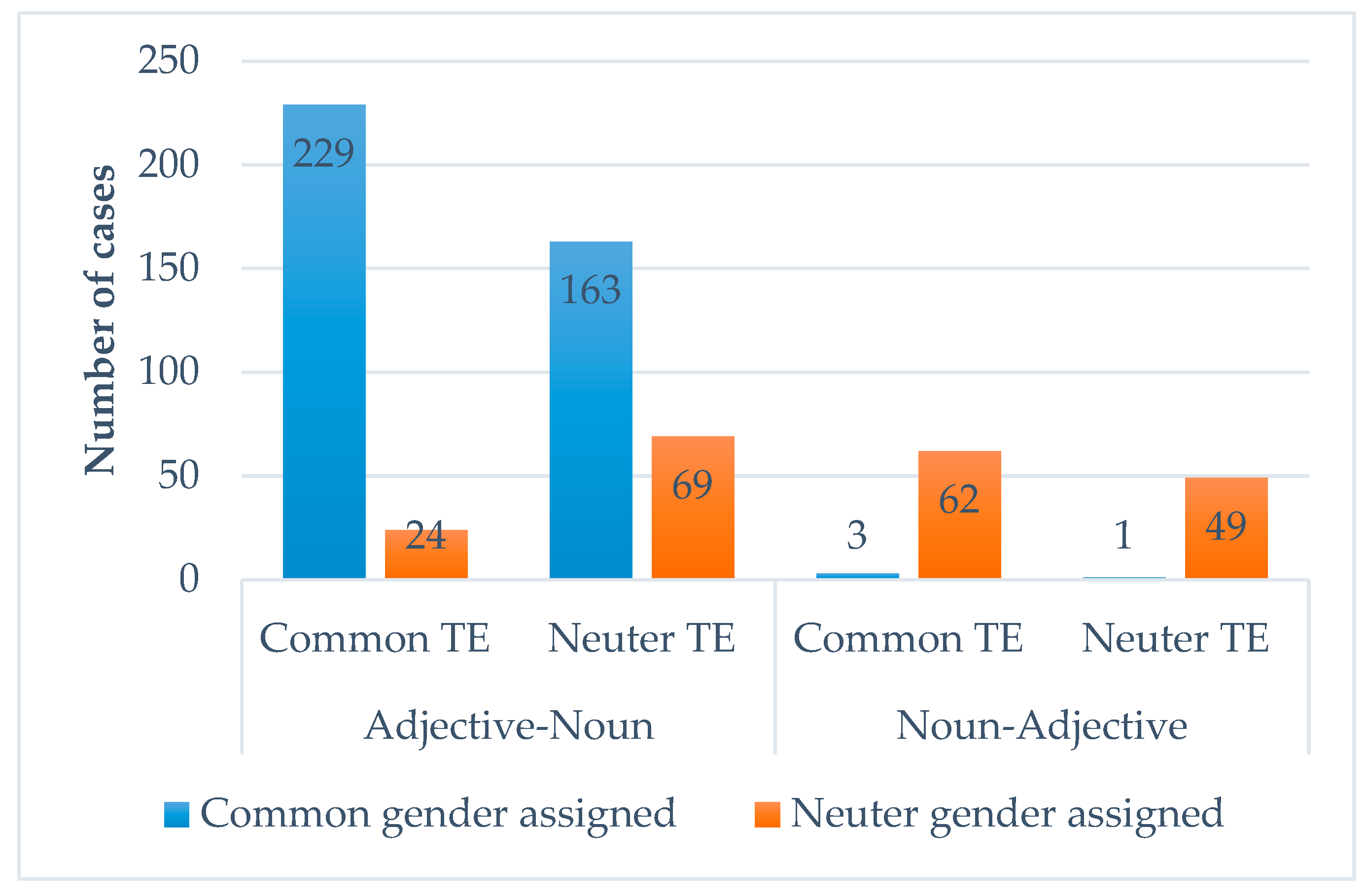

6.3.3. Dutch-Spanish Mode

6.3.4. Dutch-Spanish Mode—Individual Differences between Participants

- Common default strategy.

- Neuter default strategy.

- Analogical gender strategy.

- Postnominal neuter default strategy.

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Aalberse, Suzanne, Ad Backus, and Pieter Muysken. 2019. Heritage Languages. A Language Contact Approach. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, Irma V. 2011. Spanish gender agreement under complete and incomplete acquisition: Early and late bilinguals’ linguistic behavior within the noun phrase. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 14: 332–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Raquel T. 1999. Noun phrase gender agreement in language attrition: Preliminary results. Bilingual Research Journal 23: 318–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baayen, R. Harald, Douglas J. Davidson, and Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language 59: 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiola, Lucia, and Ariane Sande. 2018. Gender assignment in Basque/Spanish mixed Determiner Phrases: A study of simultaneous bilinguals. In Code-switching—Experimental Answers to Theoretical Questions: In honor of Kay González-Vilbazo. Edited by Luis López. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Balam, Osmer, Usha Lakshmanan, and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. 2021. Gender assignment strategies among simultaneous Spanish/English bilingual children from Miami, Florida. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 14. [Google Scholar]

- Balam, Osmer. 2016. Semantic categories and gender assignment in contact Spanish: Type of code-switching and its relevance to linguistic outcomes. Journal of Language Contact 9: 405–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, Kate, M. Carmen Parafita Couto, and Hans Stadthagen-Gonzalez. 2018. Investigating Gender Assignment Strategies in Mixed Purepecha–Spanish Nominal Constructions. Languages 3: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, Elma, Daniela Polišenská, and Fred Weerman. 2008. Articles, adjectives and age of onset: The acquisition of Dutch grammatical gender. Second Language Research 24: 297–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, Geert. 2019. The Morphology of Dutch, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boumans, Louis Patrick Clémens. 1998. The Syntax of Code-Switching: Analysing Moroccan Arabic/Dutch Conversation. Ph.D. dissertation, Katholieke Universiteit, van Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuis, Hans. 2013. Syntax of Dutch: Adjectives and Adjective Phrases. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Susanne. 1989. Second-language acquisition and the computational paradigm. Language Learning 39: 535–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, Michael, and Anne Pauwels. 2013. The Dutch language in Australia. In Language and Space. An International Handbook on Linguistic Variation. Volume 3: Dutch. Edited by Frans Hinskens and Johan Taeldeman. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 858–79. [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, Michael. 1977. Nieuw-Hollands or Double-Dutch. Dutch Studies 3: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, Greville G. 1991. Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornips, Leonie, and Aafke Hulk. 2008. Factors of success and failure in the acquisition of grammatical gender in Dutch. Second Language Research 24: 267–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornips, Leonie. 2008. Loosing grammatical gender in Dutch: The result of bilingual acquisition and/or an act of identity? International Journal of Bilingualism 12: 105–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Rocío Pérez-Tattam. 2016. Grammatical gender selection and phrasal word order in child heritage Spanish: A feature re-assembly approach. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 19: 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuchar, Margaret, Peredur Davies, Jon Russell Herring, M. Carmen Parafita Couto, and Diana Carter. 2014. Building bilingual corpora. In Advances in the Study of Bilingualism. Edited by Enlli Môn Thomas and Ineke Mennen. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, Evelyn, Aafke Hulk, and Ianthi Maria Tsimpli. 2018. Crosslinguistic influence in the discovery of gender: The case of Greek–Dutch bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 21: 694–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, Nadine, Malin Hager, and Natascha Müller. 2012. Code-switching within determiner phrases in bilingual children: French, Italian, Spanish and German. Zeitschrift für Französische Sprache und Literatur 122: 227–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeizabarrena, María José, and Amaia Munarriz-Ibarrola. 2019. Gender variability in mixed DPs as evidence for a less stable “third” lexicon in code-switching. Paper presented at 37th AESLA International Conference, Valladolid, Spain, March 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeizabarrena, María José. 2009. Development in language mixing: Early Basque-Spanish bilingualism. In Hispanic Child Languages: Typical and Impaired Development. Edited by John Grinstead. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Goebel-Mahrle, Thomas, and Naomi L. Shin. 2020. A corpus study of child heritage speakers’ Spanish gender agreement. International Journal of Bilingualism, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullberg, Marianne, Peter Indefrey, and Pieter Muysken. 2009. Research techniques for the study of code-switching. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-Switching. Edited by Barbara E. Bullock and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Leonie Cornips. 2006. Neuter gender and interface vulnerability in child L2/2L1 Dutch. In Paths of Development in L1 and L2 Acquisition. Edited by Sharon Unsworth, Teresa Parodi, Antonella Sorace and Martha Young-Scholten. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 107–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriondo Etxeberria, Alejandra. 2017. Kode-alternantzia elebidun gazteetan: DS nahasiak. Gogoa 16: 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarri van Suchtelen, Pablo. 2016. Spanish as a Heritage Language in The Netherlands. A Cognitive Linguistic Exploration. Ph.D. dissertation, Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Jake, Janet L., Carol Myers-Scotton, and Steven Gross. 2002. Making a minimalist approach to codeswitching work: Adding the Matrix Language. Bilingualism, Language and Cognition 5: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Królikowska, Marta Anna, Emma Bierings, Anne L. Beatty-Martínez, Christian Navarro-Torres, Paola E. Dussias, and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. 2019. Gender assignment strategies within the bilingual determiner phrase: Four Spanish-English communities examined. Paper presented at 3rd Conference on Bilingualism in the Hispanic and Lusophone World (BHL), Leiden, The Netherlands, January 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchenbrandt, Imme. 2005. Gender Acquisition in Bilingual Spanish. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism. Edited by James Cohen, Kara T. McAlister, Kellie Rolstad and Jeff MacSwan. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 1252–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2018. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 564–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2013. A new term for a better distinction: A view from the higher end of the proficiency scale. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 203–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liceras, Juana M., Raquel Fernández Fuertes, Susana Perales, Rocío Pérez-Tattam, and Kenton Todd Spradlin. 2008. Gender and gender agreement in bilingual native and non-native grammars: A view from child and adult functional-lexical mixings. Lingua 118: 827–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liceras, Juana M., Raquel Fernández Fuertes, Aurora Bel, and Cristina Martínez. 2012. The mental representation of Gender and Agreement Features in Child 2L1 and Child L2 grammars: Insights from code-switching. Paper presented at UIC Bilingualism Forum, Chicago, IL, USA, October 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana M., Raquel Fernández Fuertes, and Rachel Klassen. 2016. Language dominance and language nativeness. The view from English-Spanish codeswitching. In Spanish-English Codeswitching in the Caribbean and the US. Edited by Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo, Catherine M. Mazak and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 107–38. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk, 3rd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Mercer. 1969. Frog, Where Are You? New York: Dial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvana, and Kim Potowski. 2007. Command of gender agreement in school-age Spanish-English Bilingual Children. International Journal of Bilingualism 11: 301–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvana, Justin Davidson, Israel De La Fuente, and Rebecca Foote. 2014. Early language experience facilitates the processing of gender agreement in Spanish heritage speakers. Bilingualism 17: 118–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvana, Rebecca Foote, and Silvia Perpiñán. 2008. Gender agreement in adult second language learners and Spanish heritage speakers: The effects of age and context of acquisition. Language Learning 58: 503–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munarriz-Ibarrola, Amaia, Varun de Castro Arrazola, M. Carmen Parafita Couto, and María José Ezeizabarrena. 2019. Gender in the production of Spanish-Basque mixed nominal constructions. Paper presented at 3rd Conference on Bilingualism in the Hispanic and Lusophone World (BHL), Leiden, The Netherlands, January 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, Naomi. 2015. A sociolinguistic view of null subjects and VOT in Toronto heritage languages. Lingua 164: 309–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Lourdes. 2019. The study of heritage language development from a bilingualism and social justice perspective. Language Learning 70: 15–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, Ricardo, and Naomi Lapidus. 2003. An adaptive approach to noun gender in New York contact Spanish. In A Romance Perspective on Language Knowledge and Use. Selected papers from the 31st Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages. Edited by Rafael Núñez-Cedeño, Luis López and Richard Cameron. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 209–32. [Google Scholar]

- Parafita Couto, M. Carmen, Amaia Munarriz, Irantzu Epelde, Margaret Deuchar, and Beñat Oyharçabal. 2015. Gender conflict resolution in Spanish-Basque mixed DPs. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 18: 304–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Barbara Z. 2002. Narrative competence among monolingual and bilingual school children in Miami. In Language and Literacy in Bilingual Children. Edited by D. Kimbrough Oller and Rebecca E. Eilers. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 135–74. [Google Scholar]

- Polinsky, Maria, and Gregory Scontras. 2019. Understanding heritage languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 22: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplack, Shana, Alicia Pousada, and David Sankoff. 1982. Competing influences on gender assignment: Variable process, stable outcome. Lingua 57: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, Andrew, Tanja Kupisch, Regina Köppe, and Gabriele Azzaro. 2007. Concord, convergence and accommodation in bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 10: 239–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, Iggy M. 1989. The organisation of grammatical gender. Transactions of the Philological Society 87: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodina, Yulia, and Marit Westergaard. 2017. Grammatical gender in bilingual Norwegian-Russian Acquisition: The role of input and transparency. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 20: 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sadek, Carmen, Jackie Kiraithe, and Hildebrando Villareal. 1975. The acquisition of the concept of grammatical gender in monolingual and bilingual speakers of Spanish. In 1975 Colloquium on Hispanic Linguistics. Edited by Frances M. Aid, Melvyn C. Resnick and Bohdan Saciuk. Washington: Georgetown University Press, pp. 131–49. [Google Scholar]

- Teschner, Richard V., and William M. Russell. 1984. The gender patterns of Spanish nouns: An inverse dictionary-based analysis. Hispanic Linguistics 1: 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- Treffers-Daller, Jeanine. 1993. Mixing Two Languages: French-Dutch Contact in a Comparative Perspective. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, Sharon, Froso Argyri, Leonie Cornips, Aafke Hulk, Antonella Sorace, and Ianthi Maria Tsimpli. 2014. The role of age of onset and input in early child bilingualism in Greek and Dutch. Applied Psycholinguistics 35: 765–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés Kroff, Jorge R. 2016. Mixed NPs in Spanish-English bilingual speech: Using a corpus-based approach to inform models of sentence processing. In Spanish-English Codeswitching in the Caribbean and the US. Edited by Rosa E. Guzzardo Tamargo, Catherine M. Mazak and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés Kroff, Jorge R., Frederieke Rooijakkers, and M. Carmen Parafita Couto. 2019. Spanish Grammatical Gender Interference in Papiamentu. Languages 4: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Osch, Brechje, Aafke Hulk, Petra Sleeman, and Pablo Irizarri van Suchtelen. 2014. Gender agreement in interface contexts in the oral production of heritage speakers of Spanish in The Netherlands. Linguistics in The Netherlands 31: 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Osch, Brechje. 2019. Vulnerability in heritage speakers of Spanish in The Netherlands: An interplay between language-internal and language/external factors. Doctoral dissertation, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- van Osch, Brechje, and Petra Sleeman. 2018. Spanish heritage speakers in The Netherlands: Linguistic patterns in the judgment and production of mood. International Journal of Bilingualism 22: 513–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Lydia, Elena Valenzuela, Martyna Kozlowska-MacGregor, and Yan-Kit Ingrid Leung. 2004. Gender and number agreement in nonnative Spanish. Applied Psycholinguistics 25: 105–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Throughout the paper, bold text is used for Dutch, while italics are used for Spanish. |

| 2 | There are, however, phonological and semantic constraints to the realization of the schwa-suffix, which were avoided in the experiment of the present study (Broekhuis 2013, sct. 5.1; Booij 2019, pp. 41–44). |

| 3 | Although we wish to refrain from a perspective that views heritage grammars as deficient in any way, terms such as ‘target’ and ‘accuracy’ are sometimes used throughout this paper to refer to ‘complying with the monolingual grammar’. |

| 4 | This study also included heritage speakers of Papiamento and Turkish, who did the same director-matcher task as the Spanish speakers in order to compare the results of speakers of different HLs. In an ideal situation, four color adjectives that inflect for gender in Spanish would have been chosen. However, because Papiamento borrowed many of its color adjectives from Dutch, several color adjectives that do inflect in Spanish could not be used, as this would complicate Dutch-Papiamento code-switching. Three color adjectives that do inflect for gender in Spanish (black, white, red) remained, and a fourth one (green) was picked because the Papiamento word is different from Dutch. |

| 5 | To reduce the time of the experimental procedure, we did not include a separate measure of general proficiency, and used the participants’ self-reports for our analyses. Previous research with heritage speakers of Spanish in The Netherlands (van Osch 2019) has shown self-reports to correlate significantly with other measures of proficiency such as the DELE (Diploma Español de Lengua Extranjera) and lexical decision tasks. Proficiency in Dutch was not measured, as we assumed the speakers to be monolingual-like in their dominant language. |

| 6 | Even though the effect size of ‘other input in Spanish’ is considerably lower than that of ‘use of the HL with immediate family´, we consider the high z-value and low p-value for the former variable to indicate that it is indeed a meaningful result deserving of mention. |

| 7 | Even though the effect size of ‘number of years spent in the heritage country’ is considerably lower than that of ‘previous parental input’, we consider the high z-value and low p-value for the former variable to indicate that it is indeed a meaningful result that deserves mention. |

| 8 | An anonymous reviewer pointed our attention to the relatively large standard error for this effect. However, given the large estimate, we consider this effect to be indeed a meaningful result that deserves mention. |

| 9 | Although it could be argued that an absent determiner, when combined with an inflected adjective, may also be an indication of an omitted definite determiner (and thus a definite DP), our data show that within the same participant, absent determiners sometimes combined with inflected and sometimes with uninflected adjectives, implying that it is likely that in the former case, the adjective is used to assign common gender and in the latter to assign neuter gender. |

| 10 | Even though the effect sizes of these two variables differ considerably, we consider the high z-values and low p-values to indicate that both variables indeed are important predictors of gender assignment in our data. |

| 11 | Although there were participants that used invariably neuter postnominal adjectives, none of the extra-linguistic variables we looked at served as a predictor. |

| Definite | Indefinite | |

|---|---|---|

| Common | de klein-e boom ‘the small tree’ | een klein-e boom ‘a small tree’ |

| Neuter | het klein-e huis ‘the small house’ | een klein-Ø huis ‘a small house’ |

| Canonical Noun | Non-Canonical Noun | Non-Canonical Adj. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | el/unlibro pequeño ‘the/a small book’ | el/un peine pequeño ‘the/a small comb’ | el/un libro grande ‘the/a big book’ |

| Feminine | la/unamesa pequeña ‘the small table’ | la/una flor pequeña ‘the small flower’ | la/una mesa grande ‘the big table’ |

| 1. hamer—‘hammer’ | 2. huis—‘house’ | |

| Default gender (masc.) | elhamer | elhuis |

| Default gender (fem.) | lahamer | lahuis |

| Analogical gender | elhamer | lahuis |

| Spanish equivalent | el martillo (masc.) | la casa (fem.) |

| 1. martillo—‘hammer’ | 2. casa—‘house’ | |

| Default gender (common) | demartillo | decasa |

| Default gender (neuter) | hetmartillo | hetcasa |

| Analogical gender | demartillo | hetcasa |

| Dutch equivalent | de hamer (common) | het huis (neuter) |

| Common Gender | Neuter | |

|---|---|---|

| Canonical masculine | hamer/martillo ‘hammer’ hoed/sombrero (or gorro) ‘hat’ | boek/libro ‘book’ oog/ojo ‘eye’ |

| Canonical feminine | kaars/vela ‘candle’ fles/botella ‘bottle’ | huis/casa ‘house’ bed/cama ‘bed’ |

| Non-canonical masculine | bank/sofá (or sillón) ‘couch’ kam/peine ‘comb’ | hart/corazón ‘heart’ spook/fantasma ‘ghost’ |

| Non-canonical feminine | sleutel/llave ‘key’ bloem/flor ‘flower’ | kruis/cruz ‘cross’ |

| Subject. | Age at Testing | Gender | Age of Arrival | Years Spent in NL | Years Spent in HL Country | HL Lessons | Language Usage % | Parental Input % | Other Input (hours per week) | Average Skill HL | Learning Disability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate Family NL | Immediate Family HL | Non-Immediate Family NL | Non-Immediate Family HL | Input Aged 0–4 NL | Input Aged 0–4 HL | Current Input NL | Current Input HL | ||||||||||

| SA01 | 20 | F | 8 | 13 | 8 | yes | 0 | 100 | 81 | 19 | 5 | 2.75 | |||||

| SA02 | 28 | F | 10 | 19 | 10 | no | 15 | 85 | 4 | 96 | 20 | 2.75 | |||||

| SA03 | 52 | F | 12 | 32 | 20 | yes | 100 | 0 | 13 | 88 | 15 | 3 | |||||

| SA04 | 21 | F | 0 | 18 | 4 | yes | 68 | 32 | 92 | 8 | 24 | 3 | |||||

| SA05 | 37 | M | 0 | 37 | 0 | yes | 100 | 0 | 38 | 63 | 33 | 3 | |||||

| SA06 | 20 | F | 3 | 18 | 2 | no | 60 | 40 | 75 | 25 | 31 | 2.75 | 1 | ||||

| SA07 | 19 | F | 4 | 16 | 4 | no | 67 | 33 | 83 | 17 | 24 | 2.5 | |||||

| SA08 | 19 | F | 0 | 19 | 0 | no | 83 | 17 | 100 | 0 | 6 | 2.75 | |||||

| SC01 | 10 | M | 0 | 10 | 0 | no | 60 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 56 | 45 | 1 | 2.25 | |

| SC02 | 8 | F | 0 | 8 | 0 | no | 50 | 50 | 80 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 55 | 45 | 6.5 | 2.5 | |

| SC03 | 11 | M | 3 | 9 | 3 | no | 63 | 37 | 80 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 6.5 | 3 | 3 |

| SC04 | 10 | M | 6 | 4 | 6 | no | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| SC05 | 9 | F | 0 | 7 | 2 | no | 70 | 30 | 50 | 50 | 13 | 88 | 38 | 63 | 8 | 1.5 | |

| SC06 | 9 | M | 2 | 7 | 2 | no | 67 | 33 | 80 | 20 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 7 | 2.75 | |

| SC07 | 9 | F | 0 | 9 | 0 | no | 67 | 33 | 100 | 0 | 53 | 48 | 55 | 45 | 1 | 1.75 | |

| SC08 | 8 | F | 0 | 8 | 0 | no | 50 | 50 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 100 | 55 | 45 | 14 | 2 | |

| ST01 | 15 | F | 11 | 4 | 11 | yes | 17 | 83 | 50 | 50 | 33 | 3 | |||||

| ST02 | 13 | F | 0 | 13 | 0 | no | 87 | 14 | 58 | 42 | 7 | 3 | |||||

| ST03 | 13 | F | 0 | 13 | 0 | no | 50 | 50 | 90 | 10 | 1.5 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| ST04 | 15 | F | 0 | 15 | 0 | no | 83 | 17 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1.75 | |||||

| ST05 | 15 | M | 9 | 6 | 9 | no | 15 | 85 | 91 | 9 | 3.5 | 1.75 | |||||

| Subject Number | Noun-Adjective | Adjective-Noun | DP+Relative Clause | Main Strategy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | |||||||

| Ma | Mi | Ma | Mi | Ma | Mi | Ma | Mi | Ma | Mi | ||

| SA01 | 10 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| SA02 | 17 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 & 3 | ||||||

| SA03 | 14 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| SA04 | 16 | 14 | 1 | ||||||||

| SA05 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 3 | |||||||

| SA06 | 19 | 1 | 14 | 3 | |||||||

| SA07 | 16 | 12 | 1 | ||||||||

| SA08 | 27 | 17 | 4 | 1 & 3 | |||||||

| SC01 | 15 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| SC02 | 26 | 23 | 1 | ||||||||

| SC03 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 1 & 3 | ||||||

| SC04 | 24 | 10 | 2 | 1 & 3 | |||||||

| SC05 | 12 | 15 | 3 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| SC06 | 16 | 12 | 1 | 4 | |||||||

| SC07 | 12 | 11 | 4 | ||||||||

| SC08 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| ST01 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| ST02 | 15 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 1 & 3 | ||||||

| ST03 | 16 | 14 | 4 | ||||||||

| ST04 | 15 | 14 | 5 | ||||||||

| ST05 | 15 | 1 | 11 | 3 | |||||||

| Subject Number | Self-Reported Proficiency Spanish | Gender Accuracy Dutch | Gender Accuracy Spanish | Usage Non-Immediate Family Dutch | Usage Non-Immediate Family Spanish | Other Input Spanish | Main Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA01 | 2.75 | 97.83% | 100.00% | 80.00% | 11.43% | 5.0 | 3 |

| SA02 | 2.75 | 54.29% | 100.00% | 3.75% | 96.25% | 20.0 | 1 & 3 |

| SA03 | 3 | 96.43% | 84.38% | 12.50% | 87.50% | 15.0 | 1 |

| SA04 | 3 | 77.27% | 98.15% | 91.67% | 8.33% | 24.0 | 1 |

| SA05 | 3 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 37.50% | 62.50% | 33.0 | 3 |

| SA06 | 2.75 | 95.45% | 100.00% | 75.00% | 25.00% | 31.0 | 3 |

| SA07 | 2.5 | 83.87% | 90.32% | 63.33% | 16.67% | 24.0 | 1 |

| SA08 | 2.75 | 100.00% | 90.24% | 100.00% | 0.00% | 6.0 | 1 & 3 |

| SC01 | 2.25 | 100.00% | 78.57% | 40.00% | 60.00% | 1.0 | 1 |

| SC02 | 2.5 | 96.67% | 71.43% | 80.00% | 20.00% | 6.5 | 1 |

| SC03 | 3 | 100.00% | 93.33% | 80.00% | 20.,00% | 6.5 | 1 & 3 |

| SC04 | 1 | 53.57% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 0.00% | 8.0 | 1 & 3 |

| SC05 | 1.5 | 55.26% | 98.51% | 50.00% | 50.00% | 8.0 | 3 |

| SC06 | 2.75 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 80.00% | 20.00% | 7.0 | 4 |

| SC07 | 1.75 | 80.00% | 66.67% | 100.00% | 0.00% | 1.0 | 4 |

| SC08 | 2 | 96.67% | 95.45% | 60.00% | 20.00% | 14.0 | 4 |

| ST01 | 3 | 50.00% | 97.44% | 41.67% | 41.67% | 33.0 | 1 |

| ST02 | 3 | 96.97% | 88.73% | 58.33% | 41.67% | 7.0 | 1 & 3 |

| ST03 | 2 | 100.00% | 83.78% | 75.00% | 8.33% | 1.5 | 4 |

| ST04 | 1.75 | 86.67% | 53.33% | 100.00% | 0.00% | 0.0 | 5 |

| ST05 | 1.75 | 53.33% | 100.00% | 91.43% | 8.57% | 3.5 | 3 |

| Adjective-Noun | Noun-Adjective | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Common Gender DP |

Neuter Gender DP |

Common Gender DP |

Neuter Gender DP | Main Strategy | |||||

| Subject Number | Match | Mismatch | Match | Mismatch | Match | Mismatch | Match | Mismatch | |

| SA01 | 2 | 14 | 14 | 4 | |||||

| SA02 | 13 | 16 | 1 | ||||||

| SA03 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 4 | ||||

| SA04 | 14 | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| SA05 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 1 & 4 | ||||

| SA06 | 18 | 11 | 7 | 1 & 3 | |||||

| SA07 | 15 | 14 | 1 | ||||||

| SA08 | 21 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 1 & 3 | ||||

| SC01 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 & 3 | |||

| SC02 | 3 | - | |||||||

| SC03 | 15 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| SC04 | 24 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| SC05 | 12 | 13 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| SC06 | 16 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 1 & 3 | ||||

| SC07 | 4 | 1 | 11 | 11 | 2 | ||||

| SC08 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 4 | ||

| ST01 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ||

| ST02 | 16 | 8 | 7 | 1 & 3 | |||||

| ST03 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 2 & 4 | ||||

| ST04 | 11 | 12 | 4 | ||||||

| ST05 | 15 | 14 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Subj # | Gender Accuracy Dutch | Gender Accuracy Spanish | Age of Onset Dutch | Years in HL Country | Other Input Spanish | Usage Immediate Family Dutch | Usage Immediate Family Spanish | Main Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA01 | 97.83% | 100.00% | 8 | 8 | 5.0 | 0.00% | 50.00% | 4 |

| SA02 | 54.29% | 100.00% | 10 | 10 | 20.0 | 15.00% | 85.00% | 1 |

| SA03 | 96.43% | 84.38% | 12 | 20 | 15.0 | 100.00% | 0.00% | 4 |

| SA04 | 77.27% | 98.15% | 0 | 4 | 24.0 | 68.33% | 31.67% | 1 |

| SA05 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 0 | 0 | 33.0 | 100.00% | 0.00% | 1 & 4 |

| SA06 | 95.45% | 100.00% | 3 | 2 | 31.0 | 56.67% | 40.00% | 1 & 3 |

| SA07 | 83.87% | 90.32% | 4 | 4 | 24.0 | 66.67% | 33.33% | 1 |

| SA08 | 100.00% | 90.24% | 0 | 0 | 6.0 | 83.33% | 16.67% | 1 & 3 |

| SC01 | 100.00% | 78.57% | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 56.67% | 36.67% | 1 & 3 |

| SC02 | 96.67% | 71.43% | 0 | 0 | 6.5 | 50.00% | 50.00% | - |

| SC03 | 100.00% | 93.33% | 3 | 3 | 6.5 | 63.33% | 36.67% | 3 |

| SC04 | 53.57% | 100.00% | NA | NA | 8.0 | 0.00% | 100.00% | 1 |

| SC05 | 55.26% | 98.51% | 0 | 2 | 8.0 | 70.00% | 30.00% | 1 |

| SC06 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 2 | 2 | 7.0 | 66.67% | 33.33% | 1 & 3 |

| SC07 | 80.00% | 66.67% | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 66.67% | 33.33% | 2 |

| SC08 | 96.67% | 95.45% | 0 | 0 | 14.0 | 33.33% | 33.33% | 4 |

| ST01 | 50.00% | 97.44% | 11 | 11 | 33.0 | 16.67% | 83.33% | 1 |

| ST02 | 96.97% | 88.73% | 0 | 0 | 7.0 | 86.50% | 13.50% | 1 & 3 |

| ST03 | 100.00% | 83.78% | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 50.00% | 50.00% | 2 & 4 |

| ST04 | 86.67% | 53.33% | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 83.00% | 17.00% | 4 |

| ST05 | 53.33% | 100.00% | 9 | 9 | 3.5 | 15.00% | 85.00% | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boers, I.; Sterken, B.; van Osch, B.; Parafita Couto, M.C.; Grijzenhout, J.; Tat, D. Gender in Unilingual and Mixed Speech of Spanish Heritage Speakers in The Netherlands. Languages 2020, 5, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040068

Boers I, Sterken B, van Osch B, Parafita Couto MC, Grijzenhout J, Tat D. Gender in Unilingual and Mixed Speech of Spanish Heritage Speakers in The Netherlands. Languages. 2020; 5(4):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040068

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoers, Ivo, Bo Sterken, Brechje van Osch, M. Carmen Parafita Couto, Janet Grijzenhout, and Deniz Tat. 2020. "Gender in Unilingual and Mixed Speech of Spanish Heritage Speakers in The Netherlands" Languages 5, no. 4: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040068

APA StyleBoers, I., Sterken, B., van Osch, B., Parafita Couto, M. C., Grijzenhout, J., & Tat, D. (2020). Gender in Unilingual and Mixed Speech of Spanish Heritage Speakers in The Netherlands. Languages, 5(4), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040068