Abstract

This paper contributes to our understanding of the grammatical architecture of heritage languages and, specifically, the role of lexical semantics, by examining the syntactic distribution of Spanish psych verbs. Object experiencer psych verbs in Spanish fall into two classes: Class II (e.g., molestar “to bother”) and Class III (e.g., encantar “to love”). Class II verbs allow numerous syntactic alternations, while Class III verbs are more restricted syntactically. The asymmetry under investigation here is attributed to a lexical semantic featural difference—Class II verbs can be [±change of state], while Class III verbs are always [−change of state]. Two groups of HSs, (intermediate (n = 21) and advanced (n = 18)), and a group of Spanish dominant bilinguals (n = 19) completed two judgment tasks, a standard proficiency measure, a vocabulary task, and a biographical questionnaire. Results reveal that the responses of both HS groups are consistent with the Spanish dominant bilinguals in nearly all conditions, indicating that HSs are highly sensitive to this syntactic distribution. These results also highlight the importance of considering the results of individual verbs in studies that focus on lexical semantics, as they not only help us understand aggregate trends, but also reveal, in this case, that even in cases of deviant underlying semantic representations, licensing restrictions at the syntax-lexical semantic interface remain intact, suggesting that this is an area of resilience in the Heritage Spanish grammar.

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

This paper contributes to our understanding of the grammatical architecture of heritage languages by examining a linguistic phenomenon that lies at the interface of syntax and lexical semantics—the syntactic distribution of object experiencer psych verbs. The role of lexical semantics in the adult heritage speaker (HS) grammar is relatively understudied within the Spanish heritage literature as well as more broadly. Yet, this area of research can inform questions at the forefront of heritage language research that relate to the nature of resilience vs. divergence in the heritage grammar as well as the role of the input in bilingual language acquisition.

Cross-linguistically, research suggests that “core” syntactic knowledge tends to be an area of resilience in the heritage grammar (see Benmamoun et al. 2013; Lohndal et al. 2019).1 Research focused on heritage Spanish provides conflicting evidence regarding this claim. Some studies (e.g., Cuza 2013, 2016) examining word order in interrogatives suggest that syntactic properties are, in fact, vulnerable to attrition. Other studies, however, find that in comparison to properties found at both internal and external interfaces, properties of core syntax are more resilient. For example, Montrul (2004) found that Spanish HSs were more successful during an oral production task with the syntax of null subjects and object clitics (considered part of the purely syntactic domain) than with the distribution of null vs. overt subjects, differential object marking (DOM), and clitic doubling, all phenomena found at the interface of syntax with semantics/pragmatics. Similarly, Montrul (2010) found in both an oral production task and an acceptability judgment task that HSs performed better on clitic placement (considered part of the core syntax) than on DOM and clitic left dislocation (CLLD) constructions, which represent interfaces of syntax with semantics/pragmatics. The results of several other studies indicate vulnerability of the syntax-semantics and syntax-pragmatics interfaces in the Spanish grammar (e.g., Cuza and Frank 2011; Gondra 2020; Hoot 2017; Montrul 2002, 2009; Montrul and Ionin 2010), although a few studies also found no evidence of difficulties in properties at the syntax-discourse interface in Spanish HSs (Leal et al. 2014, 2015). Finally, numerous studies indicate vulnerability of phenomena at the interface of syntax and morphology in heritage Spanish, including tense, aspect, and mood (e.g., Giancaspro 2019; Montrul 2002, 2009; Perez-Cortes 2020) and gender agreement (e.g., Montrul et al. 2008). Limited research, however, has focused on the role of lexical semantics in the heritage grammar (see Section 1.3.2).

Following prior research, heritage speakers are understood here as bilinguals who have acquired a minority language (i.e., Spanish) naturalistically within the context of a societal majority language (i.e., English) (e.g., Rothman 2007, 2009; Valdés 2000). The heritage language may be a unique first language (L1), or, in many cases, may be acquired simultaneously along with the majority language. In either case, formal education is generally conducted in the majority language, and, consequently, the use of the heritage language is often reserved for familial and social interactions. Typically, despite varying degrees of proficiency in the heritage language, it becomes the less dominant language as heritage bilinguals approach adulthood (Montrul 2004; Montrul and Potowski 2007).

Research has shown that the development of the heritage grammar is characterized by variability in terms of both the quantity and quality of the input received in the heritage language (e.g., Montrul 2010; Rothman 2007; Pascual y Cabo and Rothman 2012; Leal et al. 2014). When compared to monolingual native speakers, who acquire their native language in a context in which it is the societal majority language, HSs receive less linguistic input over time and may not receive any formal education in the heritage language. The input they do receive is most likely to come from first-generation immigrants and other heritage speakers, whose grammars have been influenced by these same factors (Gürel 2004; Gürel and Yılmaz 2013; Leal et al. 2015). These varying experiences and levels of input result in a variability that is not typically found in monolingual grammars. Consequently, an important aspect of heritage language research has been to identify which areas of the heritage grammar are particularly vulnerable to this variability and which are more resilient.

This study informs this question by examining an understudied domain of the heritage grammar—the interface of lexical semantics and syntax. As mentioned earlier, cross-linguistic evidence suggests that properties of “core syntax” seem to be more resilient to variability in the heritage grammar. These phenomena, such as phrase structure (Benmamoun et al. 2013), apply consistently regardless of the lexical items appearing in a particular construction. In contrast, some syntactic constructions are largely dependent on the semantics of lexical items.2 In these cases, word meanings directly influence argument structure. Studies of syntactic phenomena that are largely influenced by lexical semantics are particularly relevant for discussions of input related to heritage development. In these cases, the speaker depends not only on the syntactic input received, but also, crucially, on the input necessary to acquire the underlying semantic representation of the relevant lexical item, which, in turn, determines the argument structure.

The present study explores HS knowledge of the syntactic distribution of a widely studied phenomenon in Spanish—psych verbs. However, unlike previous research, which has focused on their morphosyntactic behavior, and which suggests that dative experiencer predicates are particularly vulnerable in HS grammars (e.g., Montrul 1998, 2016; Pascual y Cabo 2013, 2020; Silva-Corvalán 1994; Toribio and Nye 2006), this study examines the grammatical distribution of these verbs, which is dependent on lexical semantic knowledge.

1.2. Spanish Psych Verbs

Psych verbs denote a mental or emotional state and therefore can be characterized by the presence of an <experiencer> argument, which represents the individual(s) experiencing the emotional state (Belletti and Rizzi 1988). In contrast, the subject of a transitive non-psych verb is typically an <agent>. For example, in (1), the subject, John, is an <experiencer>, as he is the individual who experiences admiration for Sally, the object. In contrast, in (2), John is the <agent> of the verb “eat”, as he initiates or performs the action of the verb (Dowty 1979).

| 1. | John | admires | Sally |

| <experiencer> | <theme> | ||

| subject | object |

| 2. | John | eats | cake |

| <agent> | <theme> | ||

| subject | object |

Psych verbs in Spanish have traditionally been divided among three classes based on the correspondence of the <experiencer> to a particular syntactic argument. Class I verbs, as in (3), have a subject experiencer; Class II verbs, as in (4), have an accusative object experiencer; and Class III verbs, as in (5), have a dative object experiencer (Belletti and Rizzi 1988; Parodi-Lewin 1991). This study will focus on verbs that fall into Classes II–III, which encompass all object experiencer verbs.

| 3. | Juan | teme | los temblores |

| Juan-nom | fear-3.sg | the earthquakes-acc | |

| “Juan fears earthquakes.” | |||

| 4. | Los temblores | asustan | a | Juan |

| the earthquakes-nom | frighten-3.pl | dom | Juan-acc | |

| “Earthquakes frighten Juan.” | ||||

| 5. | A | Juan | le | gustan | los deportes |

| prep | Juan-dat | cl.dat | like-3.pl | sports-nom | |

| “Juan likes sports.” | |||||

Object experiencer psych verbs in Spanish are of particular interest in terms of argument structure due to the syntactic alternations that obtain with Class II, but not Class III verbs. The fact that the grammar allows certain argument structure alternations with Class II verbs, but not Class III verbs results in an asymmetrical grammatical distribution, which is the focus of the current study. Perhaps the most recognized argument structure alternation displayed by Class II verbs is the alternation between the accusative and dative experiencer forms. While accusative experiencers have traditionally been associated with Class II verbs and dative experiencers with Class III verbs, in fact ALL Class II verbs allow both types of object experiencers (see 6a–b). In contrast, Class III verbs allow only dative experiencers (see 7a–b).

| 6. | a. | Los temblores | asustan | a | Juan |

| the earthquakes-nom | frighten-3.pl | dom | Juan-acc | ||

| “Earthquakes frighten Juan.” | |||||

| b. | A | Juan | le | asustan | los temblores | |

| prep | Juan-dat | cl.dat | frighten-3.pl | earthquakes-nom | ||

| “Earthquakes frighten Juan.” | ||||||

| 7. | a. | *Los deportes | gustan | a | Juan |

| the sports-nom | like-3.pl | dom | Juan-acc | ||

| “Juan likes sports.” | |||||

| b. | A | Juan | le | gustan | los deportes | |

| prep | Juan-dat | cl.dat | like-3.pl | sports-nom | ||

| “Juan likes sports.” | ||||||

This asymmetric pattern of grammaticality is due to an asymmetry in the lexical semantic makeup of the verbs. Class II verbs can entail a change of state in the event of the predicate, although this is not always the case. Consequently, Class II verbs display a variable [±change of state] feature setting, in which [+change of state] licenses the grammatical use of the accusative experiencer form, while [−change of state] licenses the grammatical use of the dative experiencer form. In contrast, Class III verbs never entail a change of state and therefore display an invariable [−change of state] feature setting, meaning only the dative experiencer form is grammatically licensed for these verbs.

A less salient alternation resulting from this pattern of feature settings is the possessor attribute factoring alternation (Levin 1993). This alternation includes a structural option licensed by [+change of state], which can express that the emotional state of the experiencer is caused by the attribute/activity of a possessor. Example 8 illustrates this with the Class II verb molestar (“to bother”). 8a shows the accusative experiencer form of the verb (similar to 4 and 6a), while 8b shows the alternate structural option. In 8a, the possessor and attribute, which are the cause of the emotional state, are expressed as a single subject DP ([los chistes de Juan “Juan’s jokes”], while in 8b, the possessor is the subject DP ([Juan]) and the attribute ([sus chistes “his jokes”]) is expressed as the object of a preposition. To highlight the fact that this alternation obtains only in verbs with a [+change of state] setting, the dative experiencer counterparts of this example are given in 8c–d. 8c shows the dative experiencer form of this sentence (similar to 5 and 7b), licensed by [−change of state]. This form is grammatical, as Class II verbs can be [±change of state.] However, the structural alternation in which the attribute is separate from the subject DP (licensed by [+change of state]), as in 8d, is not allowed by the grammar, because the presence of the dative experiencer must be licensed by [−change of state].

| 8. | a. | Los chistes | de Juan | molestaron | a | María |

| the jokes | of Juan | bother-3.pl.past | >dom | Maria-acc | ||

| “Juan’s jokes bothered Maria.” | ||||||

| b. | Juan | molestó | a | María | con | sus chistes | |

| Juan | bother-3.sg.past | >dom | Maria-acc | with | his jokes | ||

| “Juan bothered Maria with his jokes.” | |||||||

| c. | A | Maria | le | molestaron | los chistes de Juan | |

| prep | Maria-dat | cl.dat | bother-3.pl.past | the jokes of Juan | ||

| “Juan’s jokes bothered Maria.” | ||||||

| d. | *A | Maria | le | molestó | Juan | con | sus chistes | |

| pre | Maria-dat | cl.dat | bother-3.sg.past | Juan-nom | with | his jokes | ||

| “Juan bothered Maria with his jokes.” | ||||||||

Examples 9a–d illustrate the fact that this alternation does not apply to Class III verbs. Class III verbs, like gustar (“to like”), have an invariable [−change of state] feature setting; consequently, neither of the forms containing an accusative experiencer are licensed by Class III verbs, as shown by 9a and 9b. The dative experiencer form (licensed by [−change of state], given in 9c, is grammatical, and is the canonical form for Class III verbs. 9d, however, is disallowed by the grammar, as we saw with the verb molestar, because the alternate form containing the PP must be licensed by [+change of state], but the dative experiencer can only be licensed by [−change of state]. As such, the possessor attribute factoring alternation occurs in Class II psych verbs in Spanish, but not in Class III verbs. The structures presented here, which comprise the test items in the experimental tasks of this study, are representative of a more extensive pattern in Spanish, in which Class II verbs allow greater variability in structure, while the syntax of Class III verbs is more restricted.

| 9. | a. | *Los chistes | de Juan | gustaron | a | María |

| the jokes | of Juan | like-3.pl.past | >dom | Maria-acc | ||

| “Maria liked Juan’s jokes.” | ||||||

| b. | *Juan | gustó | a | María | con | sus chistes | |

| Juan | bother-3.sg.past | >dom | Maria-acc | with | his jokes | ||

| “Juan liked Maria with his jokes.” | |||||||

| c. | A | Maria | le | gustaron | los chistes de Juan | |

| prep | Maria-dat | cl.dat | bother-3.pl.past | the jokes of Juan | ||

| “Maria liked Juan’s jokes.” | ||||||

| d. | *A | Maria | le | gustó | Juan | con | sus chistes | |

| pre | Maria-dat | cl.dat | bother-3.sg.past | Juan-nom | with | his jokes | ||

| “Juan liked Maria with his jokes.” | ||||||||

1.3. Previous Research

1.3.1. Psych Verbs in Heritage Spanish

Previous research on psych verbs in heritage Spanish has focused largely on morphosyntactic properties, particularly of dative experiencers. Toribio and Nye (2006) utilized a production task and a judgment task to evaluate HS knowledge of several properties of dative experiencers, including subject–verb agreement, clitic–experiencer agreement, omission of the dative marker “a”, and case marking on the experiencer. HS production and judgments showed errors in all categories and overacceptance of ungrammatical items, leading the authors to claim that the HSs displayed “significant instability with respect to their knowledge of the features associated with gustar” (Toribio and Nye 2006, p. 268).3 Similarly, Pascual y Cabo (2013) utilized a judgment task to test knowledge of the following structural aspects of Class III verbs: omission of the dative clitic, case agreement innovations (e.g., yo gusto “I like”), and verb agreement innovations. The results of this task show that while the HSs accept the grammatical dative experiencer form, they also overaccept ungrammatical sentences in all of the aforementioned categories when compared to monolingual and bilingual control groups. This was particularly notable in HS participants at the intermediate level.

Of particular relevance to the current study, Pascual y Cabo (2016) examined the hypothesis that HSs have reanalyzed the argument structure of Class III verbs and treat them syntactically more like Class II verbs. This was tested via a judgment task including Class III verbs in passive constructions, based on the fact that passives are typically allowed with Class II verbs, which can be agentive, but not Class III verbs, which are unaccusative. The results show that HSs at both intermediate and advanced levels of proficiency overaccept passives with Class III verbs (which are uniformly rejected by a monolingual control group). The author concludes that these data support the hypothesis that these HSs have reanalyzed Class III verbs and treat them with the “hybrid nature” of Class II verbs.

1.3.2. Lexical Semantics in Heritage Spanish

While few studies have examined the role of lexical semantics in heritage Spanish, three studies provide evidence in this domain. Zapata et al. (2005) examined knowledge of syntactic behaviors of unergative and unaccusative verbs (representing properties of the “lexico-semantic” domain) along with Topicalization and CLLD (representing properties of the “discursive–semantic” domain). A preference task was used to examine HS sensitivity to syntactic restrictions related to the lexical subclasses (i.e., unergative vs. unaccusative verbs). According to the authors, the results show “evidence of indeterminacy in knowledge of argument mapping with subclasses of monovalent predicates” (p. 386). Taking into account the results of all aspects of the study, the authors suggest that knowledge of the core syntactic properties under investigation (those related to TP, AgrS, and AgrO) remains robust in these HSs, while properties of the lexico- and discursive–semantic interfaces are more vulnerable.

Montrul (2006) also examined the behavior of unaccusatives and unergatives in the heritage Spanish grammar via a judgment task and a processing task. The judgment task examined these two verb types with preverbal subjects, postverbal subjects, bare plural postverbal subjects, and in absolutive and passive constructions. HS responses differed from monolingual controls in two of the five conditions tested: HS judgments of intransitives in the absolutive were “less determinate”, and, when compared to the monolinguals, they overaccepted both types of intransitives in the passive (although their judgments for both types—1.57/5—still fall clearly into the rejection range). There were no differences between the groups in the remaining three conditions. Overall, Montrul argues that the HSs showed “robust knowledge of the syntactic effects of unaccusativity” (p. 37).

More recently, Zyzik (2014) examined the overgeneralization of intransitive verbs into transitive contexts with a causative meaning in heritage Spanish. This study used a sentence acceptability task to test unaccusative and unergative verbs in causative contexts in two groups of HSs (intermediate and advanced) and a group of monolingually-raised native speakers (NSs). The results show that HSs accept intransitive verbs in ungrammatical transitive contexts at a higher rate than NSs, displaying overgeneralization of the causative argument structure. These results were also mediated by verb type and proficiency. HSs overgeneralized more with unaccusative verbs than unergative verbs, and HSs at a lower proficiency level displayed more overgeneralization. The author suggests that these results indicate that the syntax-lexical semantics interface does not have “special or protected status” in relation to other domains that may be vulnerable in the heritage grammar (p. 22).

1.3.3. Motivation for Study and Research Questions

This study was motivated by previous research on the acquisition and underlying representation of Spanish psych verbs in heritage speakers, which suggests that the morphosyntactic properties of dative experiencers are an area of vulnerability in the HS grammar. However, object experiencer psych verbs in Spanish are quite diverse in nature, and relatively little is known about HS knowledge of the many additional argument structures permitted (and not permitted) by these types of verbs. The asymmetrical patterns of grammaticality that arise as a result of lexical semantic featural differences in object experiencer psych verbs provide a particularly interesting test case for HS knowledge at the interface of syntax and lexical semantics, because it is precisely these featural differences (and not simply the classifications used by linguists) that determine their argument structure possibilities. From a large number of argument structures possible with object experiencer verbs, a subset was selected for this study, which aims to build naturally on prior research and is representative of the syntactically flexible nature of Class II verbs as compared to the more restricted Class III verbs.

Further motivation for this study arose from the ongoing discussion regarding domains of vulnerability vs. resistance in the HS grammar. Cross-linguistic evidence for the resilience of core syntactic properties is robust, while many studies suggest that properties found at interfaces with other domains are more vulnerable (see Benmamoun et al. 2013; Lohndal et al. 2019; Sorace 2011). However, prior research on the interface of syntax and lexical semantics, particularly in Spanish, does not paint a clear picture. The results of Zapata et al. (2005) and Zyzik (2014) imply vulnerability in the HS grammar in this area, while the results of Montrul (2006) suggest that Spanish HSs maintain robust knowledge of syntactic behavior determined by lexical semantics.

Finally, prior research on heritage Spanish illustrates that proficiency can play a role in HS knowledge in various domains (Giancaspro 2019; Hoot 2017; Montrul 2004, 2009; Pascual y Cabo 2013; Zyzik 2014); however, there is limited evidence related to the role of proficiency at the syntax-lexical semantics interface. Zyzik (2014) found that participants at a lower proficiency level were less sensitive to transitivity violations, but other studies do not provide evidence in this area. Zapata et al. (2005) did not address proficiency, and the participants in Montrul (2006) were nearly all advanced, which did not allow for comparison across proficiency levels. Still, Montrul (2006) writes “proficiency in Spanish matters for Spanish–English bilinguals who are heritage speakers of Spanish, as it correlates significantly with potential language loss in different grammatical areas” (p. 65). More recent proposals (Putnam and Sánchez 2013; Perez-Cortes et al. 2019) argue that the indeterminacy found in HS data at lower proficiency levels is not the result of language loss; rather, it is the effect of a restructuring process during which bilinguals may have reduced or inhibited access to certain representations as a result of competing representations in their grammar.

To guide the investigation of this subset of argument structure distribution in Spanish psych verbs, the following research questions and hypotheses were put forth:

Research Question 1.

Are heritage Spanish speakers sensitive to the syntactic distribution of object experiencer psych verbs licensed by the lexical semantic feature [±change of state]?

Hypothesis 1.

Heritage speakers will display sensitivity to the syntactic behavior of Class II psych verbs, but may be less sensitive to the syntactic restrictions of Class III verbs and overaccept sentences with Class III verbs in ungrammatical conditions.

This hypothesis is based on the findings of Pascual y Cabo (2016)—in which HSs overaccepted Class III verbs in passive constructions, which are only allowed with Class II verbs—and his claim that HSs have reanalyzed Class III verbs as Class II verbs. Under the theoretical framework of the present study, this result would suggest that HSs associate Class III verbs with a variable [±change of state] feature setting rather than a fixed [−change of state] feature setting.

Research Question 2.

Does Spanish proficiency play a role in heritage Spanish speakers’ sensitivity to the syntactic distribution under investigation here?

Hypothesis 2.

Heritage speakers at a lower proficiency level will be less sensitive to the full syntactic distribution under investigation here and will be more likely to overaccept sentences with Class III verbs in ungrammatical conditions.

This hypothesis is based on previous research (e.g., Giancaspro 2019; Hoot 2017; Montrul 2004, 2009; Pascual y Cabo 2013) which has found that proficiency is a predictor of HS knowledge.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Data from two groups of Spanish HSs (intermediate (n = 21) and advanced (n = 18)) and a group of Spanish dominant bilinguals (n = 19) are reported here.4,5 Heritage speakers were placed in groups based on their performance on a standard Spanish proficiency measure (DELE), which has been used frequently in prior heritage Spanish research (e.g., Giancaspro 2019; Montrul 2006, 2009; Pascual y Cabo 2013, 2016). This proficiency measure includes 30 multiple-choice questions focused on vocabulary knowledge and 20 questions related to grammar and vocabulary within a contextualized close task. Following prior studies (e.g., Giancaspro 2019; Montrul 2009; Pascual y Cabo 2013, 2016), participants who scored between 40–50 were considered Advanced and participants who scored between 30–39 were considered Intermediate.6 At the time of participation, all of the HSs were graduate or undergraduate students at a large, public university in the U.S. All were native speakers of Spanish who were born in the U.S. or who had been living continuously in the U.S. since childhood. Of the 21 participants in the Intermediate group, 17 were born in the U.S. and four moved to the U.S. as children (at ages 1–8, mean age of arrival—3 years). Of the 18 participants in the Advanced group, 13 were born in the U.S. and five moved to the U.S. as children (at ages 0–6, mean age of arrival—3.2 years). As is representative of the heritage Spanish population in and around the location of this university, the participants and their families came from varying Spanish-speaking countries. However, the majority of participants in both HS groups were from Mexico. Intermediate HSs came from Mexico (16), Puerto Rico (2), Guatemala (1), El Salvador (1), and Peru (1). Advanced HSs came from Mexico (9), Colombia (3), Puerto Rico (2), Spain (2), Ecuador (1), and Honduras (1). All of the heritage speaker participants reported English as their dominant language on a biographical questionnaire.

A group of Spanish dominant bilinguals was also tested to serve as a point of comparison (see Table 1). This group of bilinguals was selected as a comparison rather than Spanish monolinguals (which have often been considered the standard “control group” in similar research) in light of the reported effects of the experience of bilingualism (e.g., Bialystok 2009; Sorace 2004, 2011). By comparing two groups of bilinguals, the variables that differ across groups are limited, and, at least in principle, cognitive (and other) differences between monolinguals and bilinguals are held constant. The principal distinctions between these two types of participants—HSs vs. Spanish dominant bilinguals—lies in their linguistic experiences and the input they have received. While the HSs spent most (or all) of their life in an environment where Spanish was not the majority language and grew to become dominant in English, the Spanish-dominant bilinguals spent the majority of their life in their native, Spanish-speaking country and retained Spanish as their dominant language. Like the HSs in this study, the Spanish-dominant bilinguals came from various Spanish-speaking countries, including Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Spain. All were living in the U.S. at the time of participation; however, all moved to the U.S. in adulthood (at the age of 22 or older, mean age of arrival—29 years) and had been living in the U.S. for an average of 2.76 years at the time of participation. Crucially, all of these bilinguals reported Spanish as their dominant language.

Table 1.

Participant information.

2.2. Procedure

All three groups completed two judgment tasks, the Spanish proficiency measure, and a biographical questionnaire (along with three additional experimental tasks not reported on here) in a laboratory under the supervision of the researcher. All tasks were completed via Qualtrics. The HS groups also completed a vocabulary task containing the 18 verbs included in the experimental tasks (see Table 2). The vocabulary task was a multiple choice task in which participants were instructed to select the English equivalent of each Spanish verb. Participants in both groups were highly accurate (heritage Intermediate group—97.4% accuracy, heritage Advanced group—98.8% accuracy). The data presented here excludes those items containing a verb that an individual participant was unfamiliar with. In other words, if a participant did not accurately identify the English equivalent of a particular verb, their data for all items in both tasks containing that verb were removed.

Table 2.

Verbs used in experimental tasks7.

2.3. Tasks

Participants completed two acceptability judgment tasks, each containing items comprised of twelve Class II verbs and six Class III verbs (see Table 2).

2.3.1. Acceptability Judgment Task—Aural Stimuli

The first task was an acceptability judgment task with aural stimuli (see Appendix A). The stimuli were recorded by a female native speaker from Colombia and presented along with a picture designed to evoke a general context for the item. Participants were instructed to listen to the recording and rate it on a 1–4 Likert scale (1—Sounds very bad, 2—Sounds bad, 3—Sounds good, 4—Sounds very good). Participants could replay the recording as many times as they wanted (although this was observed infrequently by the researcher). This task contained 72 total items—18 items each in the accusative and dative experiencer forms (12 x Class II verbs, 6 x Class III verbs) and 36 filler items (containing the same verbs presented in the middle construction8). For the experimental items, all verbs were used in present tense, all experiencers were [+singular, +animate], and all subjects were [+singular, −animate]. The order of items was randomized for all participants. See examples below.

| 10. | Accusative experiencer—Class II | |||

| La tarea | confunde | a | Jessica | |

| the homework-nom | confuse-3.sg | dom | Jessica-acc | |

| “The homework confuses Jessica.” | ||||

| 11. | Accusative experiencer—Class III | |||

| *La política | importa | a | Claudia | |

| the politics | matter-3.sg | dom | Claudia-acc | |

| “Politics matter to Claudia.” | ||||

| 12. | Dative experiencer—Class II | ||||

| A | Sergio | le | fascina | la biología | |

| prep | Sergio-dat | cl.dat | fascinate-3.sg | the biology-nom | |

| “Biology fascinates Sergio.” | |||||

| 13. | Dative experiencer—Class III | ||||

| A | Raúl | le | encanta | el fútbol | |

| prep | Raul-dat | cl.dat | love-3.sg | the soccer-nom | |

| “Raúl loves soccer.” | |||||

2.3.2. Acceptability Judgment Task—Written Stimuli

The second task was an acceptability judgment task with written stimuli (see Appendix B). For each item, participants were presented with a brief written context, followed by the written stimuli item. Like in the first task, stimuli were randomized, and participants were instructed to rate the stimuli item on a 1–4 Likert scale. This task also contained 72 total items—18 items (12 x Class II, 6 x Class III) in each of the forms relevant to the possessor attribute factoring alternation (see Section 1.2 and examples below).9 In all stimuli items, verbs were used in present tense, experiencers were [+singular, +animate], possessors were [+singular, +animate], and subjects were [+singular, −animate].

| 14. | a. | Sample context: |

| Fernando grita mucho mientras ve el partido de fútbol de su equipo preferido. Cuando su vecino, Luís, lo escucha, piensa que está en peligro. | ||

| “Fernando screams a lot while watching his favorite team play soccer. When his neighbor, Luis, hears him, he thinks he is in danger.” |

| b. | Accusative experiencer (Class II) | |||||

| Los gritos | de Fernando | asustan | a | Luís | ||

| the screams | of Fernando | frighten-3.pl | >dom | Luis-acc | ||

| “Fernando’s screams frighten Luis.” | ||||||

| c. | Accusative experiencer + PP (Class II) | ||||||

| Fernando | asusta | a | Luis | con | sus gritos | ||

| Fernando | frighten-3.sg | >dom | Luis-acc | with | his screams | ||

| “Fernando frightens Luis with his screams.” | |||||||

| d. | Dative experiencer (Class II) | |||||

| A | Luis | le | asustan | los gritos de Fernando | ||

| prep | Luis-dat | cl.dat | frighten-3.pl | the screams of Fernando | ||

| “Fernando’s screams frighten Luis.” | ||||||

| e. | Dative experiencer + PP (Class II) | |||||||

| *A | Luis | le | asusta | Fernando | con | sus gritos | ||

| prep | Luis-dat | cl.dat | frighten-3.sg | Fernando-nom | with | his jokes | ||

| “Fernando frightens Luis with his screams.” | ||||||||

3. Results

3.1. Acceptability Judgment Task—Aural Stimuli

Inferential statistical analysis was conducted by entering the responses (1–4) into a mixed-effects linear regression model with fixed effects of Group (Heritage Intermediate, Heritage Advanced, Span dominant bilinguals), Verb Class (Class II, Class III), and Argument Structure (accusative experiencer, dative experiencer), with random by-participant and by-item intercepts. The model returned significant effects of Verb Class (F(1,32.021) = 29.699, p < 0.001) and Argument Structure (F(1,32.017) = 86.373, p < 0.001) and significant interactions of Group*Verb Class (F(2,1961.550) = 6.198, p = 0.002), and Class*Argument Structure (F(1,32.017) = 47.940, p < 0.001). The estimates of variance were 0.074 for participant and 0.108 for item.

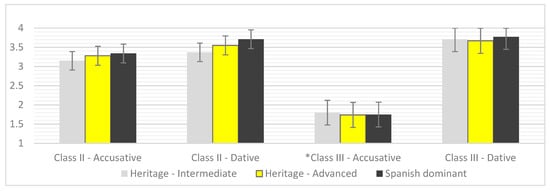

The mean ratings of all conditions are presented in Figure 1. As Class II verbs allow both argument structures, the first two conditions are expected to be accepted. A distinction is expected, however, with Class III verbs, which allow only the dative. Pairwise comparisons (with Bonferroni corrections) confirm that the mean responses of all three groups are consistent with this pattern. None of the groups make a significant distinction between accusative/dative experiencers with Class II verbs (p ≥ 0.102), while all groups make a significant distinction between argument structures with Class III verbs (p < 0.001). Finally, while all groups perform similarly in this task for the most part, pairwise contrasts indicate that the responses of the HS Intermediate group are significantly lower than those of the Spanish dominant bilinguals for the dative experiencer with Class II verbs (p = 0.012).

Figure 1.

Judgment task with aural stimuli—mean ratings.10

3.2. Acceptability Judgment Task—Written Stimuli

The responses of the judgment task with written stimuli were entered into a mixed-effects linear regression model with fixed effects of Group (Heritage Intermediate, Heritage Advanced, Spanish dominant bilinguals), Verb Class (Class II, Class III), and Argument Structure (accusative experiencer, accusative experiencer + PP, dative experiencer, dative experiencer + PP) and random by-participant and by-item intercepts. All main effects were significant: Group (F(2,56.328) = 4.270, p = 0.019), Verb Class (F(1,63.176) = 142.794, p < 0.001), and Argument Structure (F(3,67.727) = 93.966, p < 0.001). The model also returned significant interactions of Group*Verb Class (F(2,3978.202) = 36.010, p < 0.001), Group*Argument Structure (F(6,3977.379) = 20.355 p < 0.001), Class*Argument Structure (F(3,67.727) = 41.287, p < 0.001), and Group*Class*Argument Structure (F(6,3977.379) = 3.321, p = 0.003). The estimates of variance were 0.065 for participant and 0.064 for item.

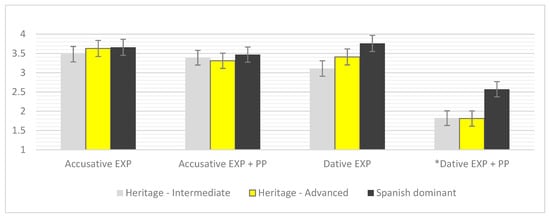

This task was comprised of items relevant to the possessor–attribute factoring alternation. Mean ratings for the four argument structures with Class II verbs are given in Figure 2. As Class II verbs allow this alternation, the accusative experiencer as well as the accusative experiencer + PP should be accepted. The dative experiencer should also be accepted with Class II verbs, while the dative experiencer + PP is disallowed by the grammar regardless of verb class, and therefore should be rejected. Pairwise comparisons confirm that all groups make a significant distinction between the ungrammatical dative exp + PP form and the remaining three grammatical forms (p < 0.001). There are no significant distinctions across groups for either of the accusative experiencer forms (p ≥ 0.51). There are, however, differences in group performance in the dative experiencer conditions. Pairwise contrasts indicate that the mean ratings of the two HS groups are significantly lower than those of the Spanish dominant bilinguals for the dative experiencer form (p ≤ 0.006) and dative experiencer + PP form (p < 0.001) with Class II verbs.

Figure 2.

Judgment task with written stimuli—mean ratings for Class II verbs.

What is particularly notable here is that the ratings of the Spanish dominant bilinguals are unexpectedly high in this condition. A closer look at the Spanish dominant bilingual data shows that the mean rating is relatively consistent across individual verbs in this class; however, it is highly variable across participants. Given that this overacceptance is noticeable only with Class II verbs (and not with Class III verbs), it is possible that the syntactic flexibility of Class II verbs makes some participants less likely to reject them, even in an ungrammatical structure.11

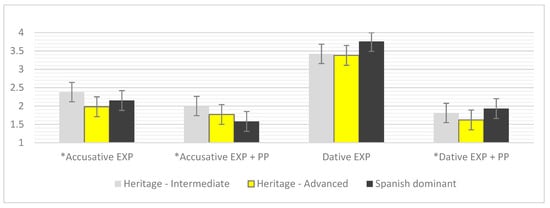

The mean ratings by group for the same four argument structures with Class III verbs are given in Figure 3. In contrast to Class II verbs, Class III verbs do not allow either accusative experiencer form, so we expect both of these forms to be rejected. As noted above, the dative experiencer + PP form is ungrammatical regardless of verb class, and thus should be rejected, leaving the dative experiencer as the only grammatical option here. As such, we expect to see a clear distinction between the grammatical dative experiencer form and the remaining three ungrammatical forms. Pairwise comparisons confirm that all groups make this distinction; mean ratings for the dative experiencer form are significantly higher than those of the remaining three argument structures (p = 0.008). Although the Spanish dominant bilinguals clearly reject both accusative experiencer forms, their mean ratings for the accusative + PP form are lower than their ratings for the accusative experiencer (p = 0.008), suggesting a stronger sensitivity to the less frequent accusative + PP form. Descriptively speaking, the ratings of the HS groups also follow this pattern, although the difference does not reach significance.

Figure 3.

Judgment task with written stimuli—mean ratings for Class III verbs.

There are also some minor differences across groups. In the accusative form (unlicensed here), the mean ratings of the heritage intermediate group are significantly higher than those of the heritage advanced group (p = 0.012), although neither heritage group differs from the Spanish dominant bilinguals. In the accusative + PP form (unlicensed here), the mean ratings of the heritage intermediate group are significantly higher than the Spanish dominant bilinguals (p = 0.006), and in the dative experiencer form, which is the only grammatical option with Class III verbs, the mean ratings of both heritage groups are significantly lower than the Spanish dominant bilinguals (p ≤ 0.03).

To summarize, the responses of all groups are in line with predicted patterns of grammaticality across tasks, suggesting that all groups are sensitive to the syntactic distribution under investigation. Overall, the responses of the HS groups are generally consistent with those of the Spanish dominant bilinguals, with differences in limited conditions. Across twelve conditions in both tasks, the responses of the heritage intermediate group differ from the Spanish dominant bilinguals in five conditions, while the heritage advanced group differs from the Spanish dominant bilinguals in just three conditions, all of these involving dative experiencers in the task with written stimuli.

3.3. Individual Verbs

The nature of the syntax-lexical semantics interface inherently requires that the speaker acquire the necessarily underlying components of verb meaning that determine the relevant syntactic behavior. In this case, it is the [±change of state] feature setting that determines the syntactic possibilities of the object experiencer verbs under investigation here. While the aggregate results for each condition suggest that both HS groups are largely sensitive to this grammatical distribution, an analysis of results by individual verb provides some further insight into the lexical semantic representations of these participants and sheds light on some of the inter-group differences.

Among Class II verbs, entusiasmar (“to enthuse”) received comparatively low ratings12 from both HS groups in grammatical conditions (accusative and dative experiencer) in the first task and from the heritage intermediate group in grammatical conditions (accusative, accusative + PP, and dative) in the second task. This result, rather than being indicative of an underlying lexical semantic representational issue, seems to reveal that the HSs, particularly at the intermediate proficiency level, simply are not comfortable with the use of this verb (whereas the Spanish dominant bilinguals consistently make the appropriate grammatical distinctions for this verb across conditions). Although the HSs (whose data is included here)13 were able to identify the meaning of this verb in the vocabulary task, it is possible that they were (i) only vaguely familiar with the verb’s general meaning, or (ii) able to identify the verb because it is a cognate with English, but had not truly acquired the underlying lexical semantic representations of the verb such that they are sensitive to its grammatical use.14 The low ratings for entusiasmar with the dative experiencer form also contributed to the statistical difference found between the HS groups and the Spanish dominant bilinguals in this condition in both tasks.

Among Class III verbs, interesar (“to interest”) received relatively high ratings from both HS groups in the (ungrammatical) accusative experiencer condition in the first task and high ratings from ALL groups in both (ungrammatical) accusative experiencer conditions in the second task. As these ratings fell clearly into the range of acceptance in some cases (e.g., 3.24/4), we could hypothesize that the HSs have assigned this verb a variable [±change of state] feature setting (rather than a fixed [−change of state] feature setting), which results in the licensing of accusative experiencer forms. The fact that the ratings for this verb were also relatively high among the Spanish dominant bilinguals in the second task suggest that this may be representative of the input the HSs receive from Spanish dominant bilinguals.

Finally, given the emphasis placed on the verb gustar (“to like”) in previous research examining dative experiencers, it is worth noting some of the results of this verb here. In particular, across tasks, in ungrammatical conditions containing accusative experiencers (including accusative experiencer + PP), both the HS groups and the Spanish dominant bilinguals rated gustar consistently lower than other Class III verbs (in the first task, for example, the HS groups essentially rate gustar at floor when used with an accusative experiencer—1.00 and 1.11.) This suggests that these participants are acutely sensitive to these ungrammatical uses of the verb gustar. This is likely due to its high frequency (according to Davies (2006), it is the most frequent of the 18 verbs included here, ranking 353 among all words in Spanish).

4. Discussion

The first research question guiding this study addresses heritage speakers’ sensitivity to the syntactic distribution of object experiencer psych verbs licensed by the lexical semantic feature [±change of state]. It was hypothesized that HSs would be sensitive to the syntactic behavior of verbs with a variable [±change of state] feature setting (i.e., Class II verbs), but may be less sensitive to the restrictions on verbs with a fixed [−change of state] feature setting (i.e., Class III verbs). This would be evidenced by overacceptance of Class III verbs in ungrammatical conditions, and, in light of the theoretical approach undertaken here, would suggest that the participants associate Class III verbs with a variable [±change of state] feature setting rather than a fixed [−change of state] feature setting.

These data reveal that the HS participants are, in fact, quite sensitive to the syntactic distribution under investigation. The results of both tasks show that the HS groups make significant distinctions based on grammaticality in all conditions, appropriately reflecting the licensing restrictions. While the HSs do not generally overaccept Class III verbs in ungrammatical conditions, it is relevant to note that the results of the verb interesar suggest that the HSs associate this verb with a variable [±change of state] feature setting rather than a fixed [−change of state] feature setting. This individual result is in line with the hypothesis, but, crucially, it reflects the nature of representation of an individual verb and is not representative of the heritage speakers’ treatment of Class III verbs in general. Rather, the overall results suggest that the HSs have successfully mapped the relevant features to the appropriately licensed argument structures, while interesar is a clear outlier.

This finding underscores the nature of properties found at the interface of syntax and lexical semantics and the importance of experimental design in investigating these properties. When syntactic behavior is driven by lexical semantics, results are highly dependent on participants’ familiarity with individual lexical items, and the results of one verb may not be representative of a speaker’s knowledge of (i) other verbs which share the same underlying feature(s), and/or (ii) the licensing relationship between particular features and argument structure. Consequently, it is fundamental to include a variety of lexical verbs and consider the results of these verbs individually as well as collectively.

These results are somewhat inconsistent with the findings of Pascual y Cabo (2016), in which HSs overaccepted Class III verbs in the passive form, which is theoretically only allowed with Class II verbs. In this study, HSs did not display a clear tendency to overaccept Class III verbs in ungrammatical contexts, although the heritage intermediate group did so in two conditions. (In the second task, ratings of this group were significantly higher than the advanced group in the accusative condition and higher than the Spanish dominant bilinguals in the accusative + PP condition, but still fell within the rejection range in both cases). This contrast is intriguing, especially since one of the tasks in this study was very similar to that employed in Pascual y Cabo (2016): namely, a judgment task with aural stimuli using a 1–4 Likert scale. One possible explanation is the difference in HS participants in the two studies. The participants in Pascual y Cabo (2016) were all of Cuban descent, while the participants of this study came from a variety of Spanish-speaking countries. However, I am unaware of any dialectal differences that would play a role in the syntactic distributions studied herein. A methodological aspect that might play a role is verb selection. The current study included six Class III verbs, while the relevant experimental items in Pascual y Cabo (2016) included only the verb gustar. Consequently, the results of that study may not be as generalizable to other verbs or contexts (this actually raises another interesting distinction, as the HS participants in this study were acutely sensitive to licensing restrictions on the verb gustar in comparison to other verbs sharing the [−change of state] feature setting (see Section 3.3), while the participants in Pascual y Cabo (2016) were apparently less sensitive to grammatical restrictions on gustar). Another possibility is that HSs are more sensitive to licensing restrictions involving certain argument structures as compared to others.

The second research question addresses the role of Spanish proficiency in heritage speakers’ sensitivity to this syntactic distribution. It was predicted that HSs at a lower proficiency level would be less sensitive to this distribution. Generally speaking, this hypothesis was not borne out in these data, as both HS groups made clear distinctions across tested conditions. However, there are some subtle differences across groups that indicate proficiency was deterministic in specific conditions. In both tasks, a developmental trend emerges in conditions with Class II verbs in the licensed dative experiencer form (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). While all groups clearly accept items in this condition, the ratings of the heritage intermediate group are significantly lower than the Spanish dominant bilinguals (p = 0.012) in the first task and significantly lower than both other groups (p < 0.03) in the second task. As mentioned in Section 3.3, this result was influenced to some extent by the low ratings given to the verb entusiasmar; still, the results indicate that ratings increase along with proficiency in these two grammatical conditions, with more pronounced differences in the task with written stimuli.

In addition, as mentioned earlier in this section, the ratings of the heritage intermediate group for [−change of state] verbs in the second task were significantly higher than the advanced group in the accusative condition and higher than the Spanish dominant bilinguals in the accusative + PP condition (although still within the rejection range in both unlicensed cases). Notably, this result was only found in the task with written stimuli—there were no differences across groups in the corresponding condition in the task with aural stimuli. One possible explanation for this is that the intermediate HSs responded more naturally to aural stimuli. This would be consistent with prior research indicating that heritage bilinguals perform better on oral vs. written tasks (e.g., Montrul et al. 2008). In this study, this seems to interact directly with proficiency, which is not surprising, given that the HSs in the advanced group scored higher on a written proficiency test, suggesting they may have more experience using Spanish in written contexts.

However, these results may be better explained by recent proposals (Putnam and Sánchez 2013; Perez-Cortes et al. 2019), which claim that proficiency interacts with frequency of use (or language activation) to predict automaticity. Under these accounts, heritage speakers at higher proficiency levels will display a higher degree of automaticity and will be more likely to successfully access information involved in a particular aspect of grammar. In the present study, then, we could argue that the advanced HSs, whose behavior was more consistent across tasks, demonstrate a higher level of automaticity in this area as compared to the intermediate HSs, who may have had more limited access to certain representations, particularly in response to written stimuli.

The subtle role of proficiency and its interaction with stimuli mode in this study can provide insight into studies of the heritage grammar in several respects. The performance of the HSs in the task with aural stimuli supports the idea that structures at the syntax-lexical semantics interface are resilient to variability. At the same time, the effects of proficiency in the task with written stimuli suggest that HSs with lower (written) proficiency may be more likely to respond differently to aural vs. written stimuli in experimental tasks. Several prior studies, which found proficiency to be deterministic in HS performance, involved morphosyntactic properties, often reliant upon knowledge of inflectional morphology (e.g., Giancaspro 2019; Montrul 2009), or discourse-related properties (e.g., Hoot 2017), both of which have been shown to be areas of vulnerability in the heritage grammar. This may be attributed to the fact that proficiency effects are more pronounced in more vulnerable domains (as well as in tasks that rely more heavily on written comprehension).15

The findings presented here build upon prior research at the syntax-lexical semantics interface in heritage Spanish, but much further research is needed. The results of this study are seemingly inconsistent with the findings of Zapata et al. (2005), who reported vulnerability at this interface based on indeterminate results with subclasses of intransitive verbs, and Zyzik 2014), who found that HSs overaccepted intransitive verbs in transitive contexts. However, these results are generally consistent with the findings of Montrul (2006), who found that HSs have a robust knowledge of syntactic behavior in this domain, and that differences in particular conditions can be attributed to particular verb types.

In order to successfully acquire the syntactic distribution under investigation here, speakers must come to acquire knowledge of both (i) the lexical semantics of the verb, and (ii) which feature settings license which forms. In other words, they must acquire the underlying semantic representation of each verb, but they also need to derive from the input how exactly this semantic representation influences the argument structure—i.e., the licensing of features to forms. I have already highlighted the importance of considering the results of individual verbs, as acquisition of the underlying semantic representations of a verb is entirely dependent on the speaker being familiar with that verb. In this study, the apparent unfamiliarity of one verb (entusiasmar) was fundamental in understanding the results of several conditions. The results of another (interesar) indicate that the lexical semantics of the verb may be represented differently than we would expect; however, crucially, the licensing of forms remains consistent. This suggests that, independently of whether these heritage bilinguals have fully acquired the lexical semantic feature setting of a verb, they are consistent when it comes to mapping feature settings to argument structure.

This study contributes novel data to expand our understanding of the heritage grammar; however, some limitations must be recognized. While the subset of argument structures tested here builds naturally on prior research and is representative of the asymmetry across object experiencer psych verbs in Spanish, it is still just a minor subset of the argument structures possible with (some of) these verbs and the distribution relies on a single lexical semantic feature: [±change of state]. In the future, a more robust set of argument structures dependent on additional features would provide more depth to the insights gleaned here.

5. Conclusions

This study has shown that HSs of Spanish are highly sensitive to the syntactic distribution of object experiencer psych verbs determined by the lexical semantic feature [±change of state]. Subtle differences based on proficiency emerge only in specific conditions and typically in response to written stimuli. The results presented here highlight the importance of considering individual verbs in studies of this type, in which syntax is dependent on lexical semantics. In this case, the individual verb results not only help us better understand trends across conditions, but also serve as an additional window into the grammar, revealing that even in cases of deviant underlying semantic representation, licensing restrictions at the syntax-lexical semantic interface remain fully intact. In sum, these data provide evidence to suggest that the interface of syntax and lexical semantics is an area of resilience in the heritage Spanish grammar.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Diana Arroyo for providing the recordings for the first task and to Sadie Hobbs for her assistance with coding and preparing the data for statistical analysis. I would also like to thank the audience at the 7th National Symposium on Spanish as a Heritage Language, the anonymous reviewers who provided valuable feedback, and Brad Hoot, editor of this special issue. Any outstanding errors are my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Acceptability Judgment Task with Aural Stimuli—Experimental Items

Class II verbs—accusative experiencer

| La tarea confunde a Jessica. | |

| El arte impresiona a Alejandro. | |

| El ambiente relaja a Cristina. | |

| La música anima a Javier. | |

| La tormenta asusta a Carmen. | |

| La película emociona a José. | |

| El libro entusiasma a Raquel. | |

| La biología fascina a Sergio. | |

| La poesía inspira a Inés. | |

| El ruido molesta a Sandra. | |

| El coche preocupa a Rubén. | |

| El dinero sorprende a Iván. |

Class III verbs—accusative experiencer

| *La verdad duele a Clara. | |

| *El fútbol encanta a Raúl. | |

| *Su familia falta a Diego. | |

| *El chocolate gusta a Eva. | |

| *La tecnología interesa a Mario. | |

| *La política importa a Claudia. |

Class II verbs—dative experiencer

| A Jessica le confunde la tarea. | |

| A Alejandro le impresiona el arte. | |

| A Cristina le relaja el ambiente. | |

| A Javier le anima la música. | |

| A Carmen le asusta la tormenta. | |

| A José le emociona la película. | |

| A Raquel le entusiasma el libro. | |

| A Sergio le fascina la biología. | |

| A Inés le inspira la poesía. | |

| A Sandra le molesta el ruido. | |

| A Rubén le preocupa el coche. | |

| A Iván le sorprende el dinero. |

Class III verbs—dative experiencer

| A Clara le duele la verdad. | |

| A Raúl le encanta el fútbol. | |

| A Diego le falta su familia. | |

| A Eva le gusta el chocolate. | |

| A Mario le interesa la tecnología. | |

| A Claudia le importa la política. |

Appendix B. Acceptability Judgment Task with Written Stimuli

Class II verbs—accusative experiencer

- Víctor necesita ayuda con la clase de matemáticas y sus padres contratan a un tutor que se llama Javier. Sin embargo, Javier no le está ayudando mucho porque sus lecciones son muy largas y complicadas.Las lecciones de Javier confunden a Víctor.

- Celia es una cocinera profesional y por eso está nerviosa cuando Alberto le invita a cenar en su casa. Sin embargo, resulta que Alberto cocina fenomenal; ¡Celia no se lo puede creer!Las comidas de Alberto impresionan a Celia.

- Cuando Gonzalo regresa de un viaje, siempre está muy estresado. Afortunadamente, su amiga Miriam hace masajes excelentes que siempre le ayudan a sentir mejor.Los masajes de Miriam relajan a Gonzalo.

- Silvia dedica mucho tiempo a sus estudiantes, siempre dándoles comentarios positivos sobre sus trabajos. Carla, una de sus estudiantes, no tiene muy buenas notas pero al recibir los comentarios de la profesora se siente motivada.Los comentarios de Silvia animan a Carla.

- Fernando grita mucho mientras ve el partido de fútbol de su equipo preferido. Cuando su vecino, Luís, lo escucha, piensa que está en peligro.Los gritos de Fernando asustan a Luís.

- Andrés llega a la casa con buenas noticias para su esposa, Julia; ¡tiene dos semanas de vacaciones! Ella está encantada con las noticias, y ya quiere planear un viaje.Las noticias de Andrés emocionan a Julia.

- Sofía y Cristian están trabajando juntos en un proyecto. Cristian está nervioso porque no tiene muchas ideas. Sin embargo, Sofía tiene muchas ideas y después de escucharlas, Cristian piensa que el proyecto va a salir muy bien.Las ideas de Sofía entusiasman a Cristian.

- Isabel tiene 15 años y nunca ha salido de su pueblo. Su prima, Beatriz, vive en la ciudad. Isabel podría pasar todo el día escuchando las historias de su prima y su vida en la ciudad.Las historias de Beatriz fascinan a Isabel.

- Tomás participa en muchas manifestaciones que apoyan la reforma educativa, pero no le parecen muy útiles. Sin embargo, cuando escucha las palabras de Guillermo, el líder del movimiento, se siente motivado de nuevo.Las palabras de Guillermo inspiran a Tomás.

- Juan tiene un buen sentido de humor y siempre está contando chistes. Desafortunadamente, su amiga María no tiene un buen sentido de humor y se ofende con los chistes de Juan.Los chistes de Juan molestan a María.

- Típicamente, Carolina es una persona muy responsable y positiva, pero esta semana ha llegado tarde al trabajo y casi no ha hablado con nadie. Enrique, su hermano, se da cuenta y teme que le esté pasando algo.Las acciones de Carolina preocupan a Enrique.

- Gloria asiste a un concierto de su amiga Mónica. Durante el concierto, Gloria queda impresionada con los talentos de su amiga. Mónica no sólo toca el piano, ¡ella canta y baila también!Los talentos de Mónica sorprenden a Gloria.

Class III verbs—accusative experiencer

- Óscar y Martin son viejos amigos y se reúnen cada año. Normalmente lo pasan muy bien, pero esta vez Martín empieza a sentirse mal después de hablar con Óscar, porque su amigo dice que está gordo y necesita hacer más ejercicio.*Los comentarios de Óscar duelen a Martin.

- Marcos aprendió a cantar flamenco en España y de vez en cuando canta algunas canciones para su esposa Verónica. Ella dice que podría escuchar las canciones todos los días porque son tan bonitas.*Las canciones de Marcos encantan a Verónica.

- Cuando Daniela se va de viaje, Jaime se queda solo en la casa y piensa tristemente en los abrazos de ella. Aunque los viajes son cortos, parece una eternidad.*Los abrazos de Daniela faltan a Jaime.

- Alejandra no puede cocinar bien, pero su amiga Tania hace unas galletas riquísimas. Las hace cada fin de semana y siempre le trae algunas a Alejandra porque sabe que son sus favoritas.*Las galletas de Tania gustan a Alejandra.

- Miguel y Roberto empiezan a hablar un día y se dan cuenta de que tienen intereses similares dentro del campo de la psicología. Roberto menciona algunos artículos que ha publicado y Miguel va directamente a la biblioteca para buscarlos.*Los artículos de Roberto interesan a Miguel.

- Victoria y Blanca son muy buenas amigas, así que cuando Blanca le cuenta a Victoria que ha perdido su trabajo y no tiene dónde vivir, Victoria está muy preocupada y quiere ayudarla.*Los problemas de Blanca importan a Victoria.

Class II verbs—accusative experiencer + PP

- Víctor necesita ayuda con la clase de matemáticas y sus padres contratan a un tutor que se llama Javier. Sin embargo, Javier no le está ayudando mucho porque sus lecciones son muy largas y complicadas.Javier confunde a Víctor con sus lecciones.

- Celia es una cocinera profesional y por eso está nerviosa cuando Alberto le invita a cenar en su casa. Sin embargo, resulta que Alberto cocina fenomenal; ¡Celia no se lo puede creer!Alberto impresiona a Celia con sus comidas.

- Cuando Gonzalo regresa de un viaje, siempre está muy estresado. Afortunadamente, su amiga Miriam hace masajes excelentes que siempre le ayudan a sentir mejor.Miriam relaja a Gonzalo con sus masajes.

- Silvia dedica mucho tiempo a sus estudiantes, siempre dándoles comentarios positivos sobre sus trabajos. Carla, una de sus estudiantes, no tiene muy buenas notas pero al recibir los comentarios de la profesora se siente motivada.Silvia anima a Carla con sus comentarios.

- Fernando grita mucho mientras ve el partido de fútbol de su equipo preferido. Cuando su vecino, Luís, lo escucha, piensa que está en peligro.Fernando asusta a Luís con sus gritos.

- Andrés llega a la casa con buenas noticias para su esposa, Julia; ¡tiene dos semanas de vacaciones! Ella está encantada con las noticias, y ya quiere planear un viaje.Andrés emociona a Julia con sus noticias.

- Sofía y Cristian están trabajando juntos en un proyecto. Cristian está nervioso porque no tiene muchas ideas. Sin embargo, Sofía tiene muchas ideas y después de escucharlas, Cristian piensa que el proyecto va a salir muy bien.Sofía entusiasma a Cristian con sus ideas.

- Isabel tiene 15 años y nunca ha salido de su pueblo. Su prima, Beatriz, vive en la ciudad. Isabel podría pasar todo el día escuchando las historias de su prima y su vida en la ciudad.Beatriz fascina a Isabel con sus historias.

- Tomás participa en muchas manifestaciones que apoyan la reforma educativa, pero no le parecen muy útiles. Sin embargo, cuando escucha las palabras de Guillermo, el líder del movimiento, se siente motivado de nuevo.Guillermo inspira a Tomás con sus palabras.

- Juan tiene un buen sentido de humor y siempre está contando chistes. Desafortunadamente, su amiga María no tiene un buen sentido de humor y se ofende con los chistes de Juan.Juan molesta a María con sus chistes.

- Típicamente, Carolina es una persona muy responsable y positiva, pero esta semana ha llegado tarde al trabajo y casi no ha hablado con nadie. Enrique, su hermano, se da cuenta y teme que le esté pasando algo.Carolina preocupa a Enrique con sus acciones.

- Gloria asiste a un concierto de su amiga Mónica. Durante el concierto, Gloria queda impresionada con los talentos de su amiga. Mónica no sólo toca el piano, ¡ella canta y baila también!Mónica sorprende a Gloria con sus talentos.

Class III verbs—accusative experiencer + PP

- Óscar y Martin son viejos amigos y se reúnen cada año. Normalmente lo pasan muy bien, pero esta vez Martín empieza a sentirse mal después de hablar con Óscar, porque su amigo dice que está gordo y necesita hacer más ejercicio.*Óscar duele a Martin con sus comentarios.

- Marcos aprendió a cantar flamenco en España y de vez en cuando canta algunas canciones para su esposa Verónica. Ella dice que podría escuchar las canciones todos los días porque son tan bonitas.*Marcos encanta a Verónica con sus canciones.

- Cuando Daniela se va de viaje, Jaime se queda solo en la casa y piensa tristemente en los abrazos de ella. Aunque los viajes son cortos, parece una eternidad.*Daniela falta a Jaime con sus abrazos.

- Alejandra no puede cocinar bien, pero su amiga Tania hace unas galletas riquísimas. Las hace cada fin de semana y siempre le trae algunas a Alejandra porque sabe que son sus favoritas.*Tania gusta a Alejandra con sus galletas.

- Miguel y Roberto empiezan a hablar un día y se dan cuenta de que tienen intereses similares dentro del campo de la psicología. Roberto menciona algunos artículos que ha publicado y Miguel va directamente a la biblioteca para buscarlos.*Roberto interesa a Miguel con sus artículos.

- Victoria y Blanca son muy buenas amigas, así que cuando Blanca le cuenta a Victoria que ha perdido su trabajo y no tiene dónde vivir, Victoria está muy preocupada y quiere ayudarla.*Blanca importa a Victoria con sus problemas.

Class II verbs—dative experiencer

- Víctor necesita ayuda con la clase de matemáticas y sus padres contratan a un tutor que se llama Javier. Sin embargo, Javier no le está ayudando mucho porque sus lecciones son muy largas y complicadas.A Víctor le confunden las lecciones de Javier.

- Celia es una cocinera profesional y por eso está nerviosa cuando Alberto le invita a cenar en su casa. Sin embargo, resulta que Alberto cocina fenomenal; ¡Celia no se lo puede creer!A Celia le impresionan las comidas de Alberto.

- Cuando Gonzalo regresa de un viaje, siempre está muy estresado. Afortunadamente, su amiga Miriam hace masajes excelentes que siempre le ayudan a sentir mejor.A Gonzalo le relajan los masajes de Miriam.

- Silvia dedica mucho tiempo a sus estudiantes, siempre dándoles comentarios positivos sobre sus trabajos. Carla, una de sus estudiantes, no tiene muy buenas notas pero al recibir los comentarios de la profesora se siente motivada.A Carla le animan los comentarios de Silvia.

- Fernando grita mucho mientras ve el partido de fútbol de su equipo preferido. Cuando su vecino, Luís, lo escucha, piensa que está en peligro.A Luís le asustan los gritos de Fernando.

- Andrés llega a la casa con buenas noticias para su esposa, Julia; ¡tiene dos semanas de vacaciones! Ella está encantada con las noticias, y ya quiere planear un viaje.A Julia le emocionan las noticias de Andrés.

- Sofía y Cristian están trabajando juntos en un proyecto. Cristian está nervioso porque no tiene muchas ideas. Sin embargo, Sofía tiene muchas ideas y después de escucharlas, Cristian piensa que el proyecto va a salir muy bien.A Cristian le entusiasman las ideas de Sofía.

- Isabel tiene 15 años y nunca ha salido de su pueblo. Su prima, Beatriz, vive en la ciudad. Isabel podría pasar todo el día escuchando las historias de su prima y su vida en la ciudad.A Isabel le fascinan las historias de Beatriz.

- Tomás participa en muchas manifestaciones que apoyan la reforma educativa, pero no le parecen muy útiles. Sin embargo, cuando escucha las palabras de Guillermo, el líder del movimiento, se siente motivado de nuevo.A Tomás le inspiran las palabras de Guillermo.

- Juan tiene un buen sentido de humor y siempre está contando chistes. Desafortunadamente, su amiga María no tiene un buen sentido de humor y se ofende con los chistes de Juan.A María le molestan los chistes de Juan.

- Típicamente, Carolina es una persona muy responsable y positiva, pero esta semana ha llegado tarde al trabajo y casi no ha hablado con nadie. Enrique, su hermano, se da cuenta y teme que le esté pasando algo.A Enrique le preocupan las acciones de Carolina.

- Gloria asiste a un concierto de su amiga Mónica. Durante el concierto, Gloria queda impresionada con los talentos de su amiga. Mónica no sólo toca el piano, ¡ella canta y baila también!A Gloria le sorprenden los talentos de Mónica.

Class III verbs—dative experiencer

- Óscar y Martin son viejos amigos y se reúnen cada año. Normalmente lo pasan muy bien, pero esta vez Martín empieza a sentirse mal después de hablar con Óscar, porque su amigo dice que está gordo y necesita hacer más ejercicio.A Martin le duelen los comentarios de Óscar.

- Marcos aprendió a cantar flamenco en España y de vez en cuando canta algunas canciones para su esposa Verónica. Ella dice que podría escuchar las canciones todos los días porque son tan bonitas.A Verónica le encantan las canciones de Marcos.

- Cuando Daniela se va de viaje, Jaime se queda solo en la casa y piensa tristemente en los abrazos de ella. Aunque los viajes son cortos, parece una eternidad.A Jaime le faltan los abrazos de Daniela.

- Alejandra no puede cocinar bien, pero su amiga Tania hace unas galletas riquísimas. Las hace cada fin de semana y siempre le trae algunas a Alejandra porque sabe que son sus favoritas.A Alejandra le gustan las galletas de Tania.

- Miguel y Roberto empiezan a hablar un día y se dan cuenta de que tienen intereses similares dentro del campo de la psicología. Roberto menciona algunos artículos que ha publicado y Miguel va directamente a la biblioteca para buscarlos.A Miguel le interesan los artículos de Roberto.

- Victoria y Blanca son muy buenas amigas, así que cuando Blanca le cuenta a Victoria que ha perdido su trabajo y no tiene dónde vivir, Victoria está muy preocupada y quiere ayudarla.A Victoria le importan los problemas de Blanca.

Class II verbs—dative experiencer + PP

- Víctor necesita ayuda con la clase de matemáticas y sus padres contratan a un tutor que se llama Javier. Sin embargo, Javier no le está ayudando mucho porque sus lecciones son muy largas y complicadas.*A Víctor le confunde Javier con sus lecciones.

- Celia es una cocinera profesional y por eso está nerviosa cuando Alberto le invita a cenar en su casa. Sin embargo, resulta que Alberto cocina fenomenal; ¡Celia no se lo puede creer!*A Celia le impresiona Alberto con sus comidas.

- Cuando Gonzalo regresa de un viaje, siempre está muy estresado. Afortunadamente, su amiga Miriam hace masajes excelentes que siempre le ayudan a sentir mejor.*A Gonzalo le relaja Miriam con sus masajes.

- Silvia dedica mucho tiempo a sus estudiantes, siempre dándoles comentarios positivos sobre sus trabajos. Carla, una de sus estudiantes, no tiene muy buenas notas pero al recibir los comentarios de la profesora se siente motivada.*A Carla le anima Silvia con sus comentarios.

- Fernando grita mucho mientras ve el partido de fútbol de su equipo preferido. Cuando su vecino, Luís, lo escucha, piensa que está en peligro.*A Luís le asusta Fernando con sus gritos.

- Andrés llega a la casa con buenas noticias para su esposa, Julia; ¡tiene dos semanas de vacaciones! Ella está encantada con las noticias, y ya quiere planear un viaje.*A Julia le emociona Andrés con sus noticias.

- Sofía y Cristian están trabajando juntos en un proyecto. Cristian está nervioso porque no tiene muchas ideas. Sin embargo, Sofía tiene muchas ideas y después de escucharlas, Cristian piensa que el proyecto va a salir muy bien.*A Cristian le entusiasma Sofía con sus ideas.

- Isabel tiene 15 años y nunca ha salido de su pueblo. Su prima, Beatriz, vive en la ciudad. Isabel podría pasar todo el día escuchando las historias de su prima y su vida en la ciudad.*A Isabel le fascina Beatriz con sus historias.

- Tomás participa en muchas manifestaciones que apoyan la reforma educativa, pero no le parecen muy útiles. Sin embargo, cuando escucha las palabras de Guillermo, el líder del movimiento, se siente motivado de nuevo.*A Tomás le inspira Guillermo con sus palabras.

- Juan tiene un buen sentido de humor y siempre está contando chistes. Desafortunadamente, su amiga María no tiene un buen sentido de humor y se ofende con los chistes de Juan.*A María le molesta Juan con sus chistes.

- Típicamente, Carolina es una persona muy responsable y positiva, pero esta semana ha llegado tarde al trabajo y casi no ha hablado con nadie. Enrique, su hermano, se da cuenta y teme que le esté pasando algo.*A Enrique le preocupa Carolina con sus acciones.

- Gloria asiste a un concierto de su amiga Mónica. Durante el concierto, Gloria queda impresionada con los talentos de su amiga. Mónica no sólo toca el piano, ¡ella canta y baila también!*A Gloria le sorprende Mónica con sus talentos.

Class III verbs—dative experiencer + PP

- Óscar y Martin son viejos amigos y se reúnen cada año. Normalmente lo pasan muy bien, pero esta vez Martín empieza a sentirse mal después de hablar con Óscar, porque su amigo dice que está gordo y necesita hacer más ejercicio.*A Martin le duele Óscar con sus comentarios.

- Marcos aprendió a cantar flamenco en España y de vez en cuando canta algunas canciones para su esposa Verónica. Ella dice que podría escuchar las canciones todos los días porque son tan bonitas.*A Verónica le encanta Marcos con sus canciones.

- Cuando Daniela se va de viaje, Jaime se queda solo en la casa y piensa tristemente en los abrazos de ella. Aunque los viajes son cortos, parece una eternidad.*A Jaime le falta Daniela con sus abrazos.

- Alejandra no puede cocinar bien, pero su amiga Tania hace unas galletas riquísimas. Las hace cada fin de semana y siempre le trae algunas a Alejandra porque sabe que son sus favoritas.*A Alejandra le gusta Tania con sus galletas.

- Miguel y Roberto empiezan a hablar un día y se dan cuenta de que tienen intereses similares dentro del campo de la psicología. Roberto menciona algunos artículos que ha publicado y Miguel va directamente a la biblioteca para buscarlos.*A Miguel le interesa Roberto con sus artículos.

- Victoria y Blanca son muy buenas amigas, así que cuando Blanca le cuenta a Victoria que ha perdido su trabajo y no tiene dónde vivir, Victoria está muy preocupada y quiere ayudarla.*A Victoria le importa Blanca con sus problemas.

References

- Belletti, Adriana, and Luigi Rizzi. 1988. Psych-verbs and θ-theory. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 6: 291–352. [Google Scholar]

- Benmamoun, Elabbas, Silvina Montrul, and Maria Polinsky. 2013. Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics 39: 129–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen. 2009. Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 12: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro. 2013. Crosslinguistic influence at the syntax proper: Interrogative subject-verb inversion in heritage Spanish. International Journal of Bilingualism 17: 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro. 2016. The status of interrogative subject-verb inversion in Spanish-English bilingual children. Lingua 180: 124–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, and Joshua Frank. 2011. Transfer effects at the syntax-semantics interface: The case of double-que questions in heritage Spanish. Heritage Language Journal 8: 66–89. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Mark. 2006. A Frequency Dictionary of Spanish: Core Vocabulary for Learners. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dowty, David R. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar: The Semantics of Verbs and Times in Generative Semantics and in Montague’s PTQ. Dordrecht: Reidel. [Google Scholar]