Abstract

This paper reports on a comprehensive phonetic study of American classroom learners of Russian, investigating the influence of the second language (L2) on the first language (L1). Russian and English productions of 20 learners were compared to 18 English monolingual controls focusing on the acoustics of word-initial and word-final voicing. The results demonstrate that learners’ Russian was acoustically different from their English, with shorter voice onset times (VOTs) in [−voice] stops, longer prevoicing in [+voice] stops, more [−voice] stops with short lag VOTs and more [+voice] stops with prevoicing, indicating a degree of successful L2 pronunciation learning. Crucially, learners also demonstrated an L1 phonetic change compared to monolingual English speakers. Specifically, the VOT of learners’ initial English voiceless stops was shortened, indicating assimilation with Russian, while the frequency of prevoicing in learners’ English was decreased, indicating dissimilation with Russian. Word-final, the duration of preceding vowels, stop closures, frication, and voicing during consonantal constriction all demonstrated drift towards Russian norms of word-final voicing neutralization. The study confirms that L2-driven phonetic changes in L1 are possible even in L1-immersed classroom language learners, challenging the role of reduced L1 use and highlighting the plasticity of the L1 phonetic system.

1. Introduction

Cross-linguistic phonetic interaction in bilingualism and language learning is believed to be bidirectional: the earlier acquired, more established language (L1) can be affected by the later acquired, often non-dominant, language (L2). This type of crosslinguistic interaction is known by many names: back-transfer, reverse interference, phonetic drift, and language attrition, to name a few. We define this type of interaction as phonetic changes in speakers’ L1 brought about by use of L2 and refer to these changes primarily as L2-to-L1 (phonetic) effects or L1 drift.

A few prominent lines of inquiry dominated the previous research on L2-to-L1 effects, leaving the full scope of this phenomenon under-explored. Specifically, the majority of previous work has focused on proficient bilinguals or advanced second language learners and most speakers were studied in the situation of L2 immersion (Baker and Trofimovich 2005; Barlow et al. 2013; Bergmann et al. 2016; Caramazza et al. 1973; Chang 2012; De Leeuw 2019; De Leeuw et al. 2018; De Leeuw et al. 2010; Flege 1987; Fowler et al. 2008; Guion 2003; Harada 2003; Hopp and Schmid 2013; Kartushina and Martin 2019; Lang and Davidson 2019; Lev-Ari and Peperkamp 2013; MacLeod and Stoel-Gammon 2005; Major 1992; Mayr et al. 2012; Mora and Nadeu 2012; Mora et al. 2015; Sancier and Fowler 1997; Simonet 2010; Tobin et al. 2017; Ulbrich and Ordin 2014). Moreover, language pairings often involved Western European languages, such as English, Spanish, French, German, and Dutch, which tend to be relatively similar phonologically and share the Latin alphabet. Finally, these studies on cross-language interaction have typically focused on sound classes that have distinct phonetic realizations in the respective languages, such as oral stops, distinguished across languages via voice onset time (VOT), or oral vowels, distinguished via formant frequencies.

The current study expands the scope of previous work on L2-to-L1 effects by examining a population of relatively inexperienced learners of a rarely studied Slavic second language (Russian). The L2 learners in the present study reside in the home country and are immersed in their native language (American English). Moreover, in addition to inquiring how comparable phonological categories can affect one another’s acoustic realization across languages, the present study also considers the transferability of phonological processes from L2 to L1. We target the acoustic realization of word-initial voiced and voiceless stops in native speech of American learners of Russian, to determine whether it has been affected by exposure to Russian. In addition, we investigate word-final stops, fricatives and affricates in learners’ English to establish whether their productions show an effect of the Russian final devoicing rule.

In the following sections, we discuss the theoretical underpinnings of the L2-to-L1 phonetic effects (Section 1.1), provide a brief overview of the previous literature on the topic (Section 1.2), and introduce the details of the present study (Section 1.3).

1.1. Mechanism of L2-to-L1 Effects

Among the theoretical models put forth to account for the production of second language speech, the speech learning model (or SLM/SLM-r; Flege 1995, 2003; Flege and Bohn 2020) explicitly predicts bidirectional phonetic interactions and outlines their general mechanism.

SLM postulates that sound categories of learners’ first and second languages coexist in the same phonological space, which a-priori creates a possibility for mutual influence. Moreover, SLM proposes that a mechanism of ‘equivalence classification’ affects the perception of L2 sounds that are acoustically non-identical but similar to existing L1 categories. As a result, corresponding L1 and L2 sounds are joined under the same category and their acoustic properties are predicted to affect each other, such that L2 sounds are realized in an L1-like manner, and L1 sounds are produced similarly to L2 ones—a situation known as category assimilation.

Flege’s own work (e.g., Flege 1987) and much of the subsequent research, however, demonstrated that phonetically separate sound categories are nevertheless maintained across languages in the speech of bilinguals, with one or both deviating from the monolingual norm in the direction of assimilation to the other language (Baker and Trofimovich 2005; Caramazza et al. 1973; Chang 2012; Flege and Eefting 1987a, 1987b; Fowler et al. 2008; Harada 2003; Major 1992; Sancier and Fowler 1997; Sundara and Baum 2006). This cross-language separation suggests that bilinguals are able to discern the acoustic–phonetic differences between the cross-language equivalents even when they are merged under the same category. Moreover, this ability is an important condition of the L2-to-L1 effects. If bilinguals perceived L2 sounds as indistinguishable from the ones in their L1, there could not be any influence of L2 on the production of L1.

This brings us to the importance of sufficient experience with L2 required for L2-to-L1 effects to take place. The assumption that L2 experience plays an important role has dominated most of the literature on L2-to-L1 phonetic effects. A large proportion of previous cross-sectional studies reported that the L1 was affected by the L2 either exclusively or to a greater degree in participants with longer L2 exposure and/or higher L2 proficiency (Baker and Trofimovich 2005; Bergmann et al. 2016; Dmitrieva et al. 2010; Flege 1987; Guion 2003; Herd et al. 2015; Huffman and Schuhmann 2016; Lang and Davidson 2019; Major 1992; Peng 1993; Schmid 2013; Schuhmann and Huffman 2015; Tobin et al. 2017).

A reduction in L1 use may also be responsible for the observed L2-assimilatory changes in the L1 speech of bilinguals (De Leeuw et al. 2010; Kartushina and Martin 2019; Mora and Nadeu 2012; Mora et al. 2015; Sancier and Fowler 1997). Indeed, phonetic changes in L1 were typically detected in circumstances that simultaneously provided greater L2 exposure and limited the use of L1, i.e., in bilinguals who were immersed in the L2-dominant environment. Moreover, in some cases it was proposed that continuous L1 use prevented L1 drift despite intensive L2 exposure (De Leeuw et al. 2010; Tobin et al. 2017).

To summarize, current theoretical models predict the emergence of L2-to-L1 phonetic effects in experienced L2 speakers, with a possible added condition of reduced L1 use. In the following section, we review relevant studies which serve to refine these general predictions.

1.2. Previous Research on L2-to-L1 Phonetic Effects

Research consistently demonstrated that greater L2 experience and proficiency lead to a greater likelihood of L2-to-L1 phonetic effects for sequential bilinguals and adult language learners. For example, Flege (1987) demonstrated that the VOT of English [t] was significantly more French-like in the speech of Americans residing in Paris, compared to American students and teachers of French who were residing domestically. The French [t] of speakers of French residing in Chicago was also significantly different from that of French monolinguals, in the direction of assimilation to English, indicating the combined effect of proficiency, experience, and immersion. Later, Lang and Davidson (2019) showed that only Americans residing in Paris, but not American students on a short-term study abroad in France, experienced a drift in native vowel acoustics in the direction of L2 norms, confirming the important role of long-term immersion.

L2 pronunciation proficiency has also been linked more directly to changes in L1 phonetics. Major (1992) reported a positive correlation between L2 proficiency and L1 drift for American immigrants to Brazil: the closer they approximated Portuguese VOT norms in their production of L2 voiceless stops, the more they deviated from native norms in their L1 productions, in the direction of assimilation to L2 (although see Kartushina and Martin (2019) who report a negative L2 proficiency–L1 drift correlation).

The age of L2 acquisition also plays a role in promoting L2-to-L1 phonetic effects. In Guion (2003), only early and mid but not late Quechua–Spanish bilinguals revealed an effect of L2 (Spanish) on native vowel acoustics. Similarly, in Baker and Trofimovich (2005) an L2-to-L1 cross-language influence in vowels was uncovered only for early but not late Korean–English bilinguals, suggesting the importance of accumulated L2 experience.

Estimating L2 experience via length of residence in an L2-dominant environment, Dmitrieva et al. (2010) showed that Russian speakers of English with greater L2 experience were more likely to realize final obstruents in Russian in a more English-like manner, with less devoicing. Similarly, Bergmann et al. (2016) established that native speech of long-term German immigrants to Canada was perceived as more accented by their monolingual compatriots as a function of a longer residence abroad.

While the effects of L2 exposure and L2 proficiency are almost inevitably conflated in research on long-term immigrants, Chang (2012, 2013) was able to disentangle the two. Chang (2012) demonstrated L1 drift in several phonetic parameters, including VOT and vowel spectrum, in beginner American learners of Korean after only a short immersion in Korean during a study abroad program. Crucially, these participants achieved only elementary proficiency in Korean by the end of the six-week program, while L1 drift was observed already at week two. This work suggests that L2 proficiency by itself is not a necessary condition of L2-to-L1 phonetic effects, but L2 exposure which comes about due to L2 immersion may be.

Chang’s work does share the element of L2 immersion, providing a level of L2 input that is both abundant and authentic, even if it is primarily overheard, with much of the previous literature. There is evidence that even overhearing-type exposure to another language may have important and long-lasting consequences. Au et al. (2002) and Knightly et al. (2003) showed that individuals who, early in life, were exposed to Spanish without learning it (‘overhearers’), upon enrolling in an L2 Spanish class, demonstrated near-native like VOTs in Spanish, compared to learners in the same class who did not overhear Spanish earlier in life. Moreover, Chang (2019b) demonstrated that L1 drift persisted for L2 learners immersed in L2 even when they no longer actively used the second language, suggesting that ambient language exposure in adulthood as well as in early childhood is an important factor affecting language production. Caramazza et al. (1973) also reported an interaction between English and French, exclusively in the direction of English affecting French, for residents of Canada who spoke only one of the two languages but were presumably exposed to both.

This work raises an important question about the minimum amount of L2 exposure required to trigger L2-to-L1 phonetic effects. Clearly, the intensive and authentic exposure provided by L2 immersion can be sufficient. However, what about non-immersion-type exposure to L2? Research on L2 learners in non-immersion situations is relatively scarce but it provides some indication that an even more fleeting introduction to another language may trigger phonetic changes in L1.

Traditional classroom learners of additional languages have been largely overlooked when it comes to L2-to-L1 effects. A number of studies examining non-immersion population were often conducted with small numbers of participants, thus arriving at somewhat inconclusive results. Huffman and Schuhmann (2016) examined four beginner American learners of Spanish and reported little evidence of L2-to-L1 phonetic effects. Between weeks 2 and 6 of language instruction, learners demonstrated no changes in the VOT of native voiced or voiceless stops. Only the frequency of prevoicing in English suggested a tendency to dissimilate away from Spanish: three participants decreased or eliminated prevoicing from their English voiced stops. Schuhmann and Huffman (2015) did show that after a period of explicit phonetic training, three out of five learners of Spanish shortened their English voiceless stops’ VOT, indicating assimilation to Spanish. Herd et al. (2015), the only large-scale (N = 40) cross-sectional study of classroom learners known to us, demonstrated that near-native and advanced learners of Spanish produced English voiced stops with more negative VOTs than beginner learners. The near-native, advanced, and intermediate learners also produced more peripheral English vowels than beginner learners did—a difference also compatible with the effect of Spanish on English. This study indicates that L1 drift is possible in more experienced classroom L2 learners but, in the absence of the monolingual control group, it was not established whether beginner learners also modified the acoustics of their native speech in the direction of second language norms. Overall, the available studies on L2-to-L1 effects in classroom learners provide limited evidence that L2 exposure in the classroom may be sufficient to trigger L1 drift.

Another reason to study classroom learners is the fact that they continue to reside in the home country while acquiring their L2. Most foreign language courses in US colleges provide active instruction 3–5 h a week. For the remainder of the time, learners use their L1. The amount of reduction in L1 use and exposure is most likely negligible in these circumstances.

This aspect of classroom language learning is important because the reduction in L1 use associated with L2 immersion could play an important role in creating conditions for the L2-to-L1 phonetic effects. Conversely, continued L1 use has been suggested to promote and protect the ‘authenticity’ of L1 speech (Kartushina et al. 2016b). For example, Bergmann et al. (2016) demonstrated a negative correlation between the amount of L1 use and the degree of perceived non-native accent in the L1 speech of long-term German immigrants to North America. De Leeuw and colleagues also showed that the German of immigrants to Canada and The Netherlands was less likely to be perceived as non-native sounding if they had a high amount of contact with other Germans in a monolingual mode (De Leeuw et al. 2010). Moreover, Mora and colleagues (Mora and Nadeu 2012; Mora et al. 2015) reported that greater use of L1 Catalan promoted more monolingual-like Catalan vowels in Catalan–Spanish bilinguals. Although Tobin et al. (2017) did not detect any L1 drift in the native speech of Spanish learners of English after a 3–4 months period of L2 immersion in the United States, they explained this result by the lack of a sufficient reduction in L1 use.

The dominant, and thus more frequently used, language is also believed to be protected from the cross-linguistic influence. For example, Kartushina and Martin (2019) showed that, in balanced Catalan–Spanish bilinguals, both languages were affected by immersion in English but in Spanish-dominant bilinguals only Catalan vowels drifted towards English (see also Caramazza et al. (1973) and Mack (1989)).

To summarize, much previous research indicates that while advanced L2 proficiency is not a necessary condition for L2-to-L1 phonetic effects, greater L2 exposure and experience promote L1 drift. Immersion-type exposure to L2 is particularly conducive to L1 drift. Moreover, the reduction in L1 use, which typically co-occurs with L2 immersion and L2 dominance, is another possible condition for L2-to-L1 phonetic effects.

The population of classroom learners, which has not been widely studied with respect to L1 drift, provides an essential complement to previous work on immersed learners; a comparison that leads to a better understanding of the role of L2 immersion and reduced L1 use in bidirectional cross-language interaction. The following section describes the present study designed to address the question of L1 drift in classroom language learners.

1.3. Present Study

The present study aims to determine whether exposure to a second language via classroom learning can lead to phonetic changes in the native speech of the learners. The second language studied by our participants is Russian.

Russian is a relatively unusual choice for American learners and a comparatively difficult language to acquire for English speakers. In a ranking of languages encompassing four different difficulty categories, the US Foreign Service Institute placed Russian in category III, among ‘hard’ languages with significant linguistic and/or cultural differences from English (https://www.state.gov/foreign-language-training/), and specified that approximately 1100 class hours are required to reach general professional proficiency in speaking and reading (S3 and R3). This amounts to 14 semesters of study, assuming a fairly typical five hours per week over a 16-week semester study pattern. Thus, although participants for the present study were recruited from the second through to the sixth semesters of Russian study, it is reasonable to assume that most had not managed to reach advanced proficiency in this amount of time.

Unlike more frequently studied languages such as French, German, Italian, and Spanish, Russian does not share the same writing system with English. This makes L1 English–L2 Russian a qualitatively different and novel language pairing to consider. In particular, we ask whether, L1 drift is as likely in pairings of languages with fewer linguistic, orthographic, and cultural similarities as among more similar languages.

We consider the voice onset time of word-initial voiced and voiceless stops as the phonetic aspect potentially subject to L1 drift. In addition to this commonly studied parameter, we examine onset f0—pitch at the beginning of the post-consonantal vowel—as a secondary correlate of voicing. Secondary correlates have rarely been studied in L2 learners and we know little about their propensity to drift towards L2 in L1 speech.

Russian realizes its initial prevocalic [+voice] stops as robustly prevoiced (with negative VOT) and its initial prevocalic [−voice] stops as voiceless unaspirated (short lag VOT) (Ringen and Kulikov 2012). English realizes its initial prevocalic [+voice] stops as a combination of weakly prevoiced (about 30% for the population, Dmitrieva et al. 2015) and voiceless unaspirated stops (70%), and its initial prevocalic [−voice] stops as voiceless aspirated (long lag VOT) (Lisker and Abramson 1964). This phonetic difference between Russian and English stop voicing is usually not taught explicitly in Russian language courses, as was confirmed by Purdue University Russian language instructors.

The expected pattern of L1 drift, based on previous research, includes a well-documented tendency towards VOT shortening in voiceless English stops. It is also possible that the prevoicing period in English [+voice] stops could be lengthened under the influence of Russian. Finally, the proportion of prevoiced to voiceless unaspirated stops among English [+voice] segments could change towards a greater frequency of prevoicing, in assimilation with Russian.

With respect to onset f0, the two languages demonstrate a congruent covariation of f0 with phonological categories (lower f0 after [+voice] stops) but an incongruent covariation with phonetic VOT categories: first, f0 is lower after prevoiced stops than after voiceless unaspirated stops in Russian but there is no such difference in English because short lag and lead VOT stops are variants of the same phonological category (Kulikov 2012; Dmitrieva et al. 2015). Thus, exposure to Russian could lead to f0 lowering after prevoiced stops in participants’ English speech. Second, English voiceless unaspirated stops are characterized by low onset f0, as they are phonologically voiced, while Russian voiceless unaspirated stops are characterized by high onset f0, as they are phonologically voiceless. Thus, an L2-to-L1 effect in this case would involve the relative raising of onset f0 after voiceless unaspirated stops in the English of Russian learners.

Finally, we investigate the temporal indices of voicing in word-final obstruents: preceding vowel duration, consonant constriction duration, and duration of voicing during constriction. This additional area of interest was selected because of important differences between English and Russian in the way phonological and phonetic voicing is treated in final obstruents. English, for the most part, maintains phonetic differences between phonologically voiced and voiceless final obstruents, although there is a gradient tendency to devoice in this position, especially for fricatives (Davidson 2016). Russian, on the other hand, features categorical devoicing in word-final position. We aim to investigate the possibility of L2-to-L1 influence on the basis of phonological rules which apply in the L2. We hypothesize that learners’ L1 may adopt this phonological process from the L2 (Barlow et al. 2013; Simonet and Amengual 2020).

We further hypothesize that such influence may be especially likely for areas of L1 phonology that trend towards change, in particular if change is in the direction of the L2 process, in this case, devoicing (see Barlow et al. (2013) and Bullock and Gerfen (2004) for similar reasoning). Thus, English speakers exposed to Russian may be expected to demonstrate a stronger tendency to devoice in word-final position than is observed for monolingual English speakers.

To summarize, the present study examines L1-immersed classroom language learners in order to extend previous investigations of L2-to-L1 effects to populations not characterized by extensive L2 exposure and reduced L1 use due to L2 immersion. To establish the phonetic effects of their L2, Russian, on their L1, English, we examine the acoustic properties of word-initial stops (VOT and onset f0), and word-final obstruents (temporal indices of final voicing).

Following previous research, we conduct two types of comparisons: that between learners’ L1 and L2, in order to determine whether the two systems are distinct or merged with respect to the select acoustic properties (a within-subject comparison) and those between learners’ and monolinguals’ L1s, in order to determine whether L2-to-L1 effects have taken place in learners’ speech (a between-subject comparison). We believe that it is important to conduct both comparisons in order to demonstrate that a degree of phonetic learning has taken place in these speakers’ L2, and that L1 drift, if present in their speech, is consistent with the nature of phonetic learning they achieved in their L2 speech. By establishing the degree of L2 phonetic learning for our participants, we further our understanding of the conditions under which L1 drift can be expected to occur. Moreover, the cooccurrence of L1 drift and L2 phonetic learning for the same features supports the notion that L2 phonetic learning is what triggers L1 drift.

To determine that L1 drift is a relatively stable feature of learners’ native speech as opposed to the short-term effect of producing speech in the two languages in immediate succession, we analyzed the effect of the order of language elicitation.

We also examine the relationship between the extent of individual L1 drift and L2 proficiency in order to test the hypothesis that magnitude of drift in L1 is linked to the degree of pronunciation gains in L2.

Thus, the three main objectives of the present research are: (1) to determine whether phonetic learning has taken place in the Russian speech of learners; (2) to determine whether L1 drift has taken place in the English speech of learners; and (3) to determine whether the degree of phonetic learning/pronunciation gains were correlated with the degree of L1 drift.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty native speakers of American English learning Russian as a second language participated in the study: eleven men and nine women, between the ages of 19 to 24 years (M = 20.6, SD = 1.3). They were recruited and recorded in two locations: Purdue University (14 participants) and the University of Kansas (6 participants). Participants filled out a language background questionnaire after the recording. All reported English as their first and native language. All participants reported learning Russian mainly through college classroom instructions and only four participated in a 2–4 months-long Russian study abroad program some time during the year preceding their enrollment in the study. On average, they studied Russian for 5 semesters by the time of participation (SD = 3, R = 1.5–12). The amount of class time varied by level, e.g., from five hours a week for semesters 1 through 4 of Russian, to three hours a week, starting from the 5th semester (Purdue campus).

Participants reported using Russian mostly in class or with classmates, on average for four hours per week (ranging from one to 6 h). Four participants reported using Russian with a family member but only up to one hour a week. The most commonly reported type of engagement with Russian was reading (M = 2 h/week, R = 1–6 h/week). Writing in Russian was the second most common activity (M = 2 h/week, R = 0.5–4 h/week). Only about half of the participants reported listening to Russian radio or watching Russian TV (M = 3 h/week, R = 1–6 h/week).

Participants’ average self-reported Russian fluency was ‘fair’ (‘3’ on a 7-point scale), and the degree of accentedness in Russian was ‘moderate’ (‘3’ on a 7-point scale). All participants studied additional modern languages in classroom settings (the majority of participants studied only one additional language per person), most commonly Spanish, French and German (for 5 semesters on average, across these three languages). Achieved proficiency was ‘fair’ on average (‘3’ on a 7-point scale). Only three participants reported ‘good’ or ‘very good’ knowledge of an additional language (German and Spanish).

Eighteen native speakers of American English from the same dialectal area (Midwest) participated in the study as the control group: four men and fourteen women, between the ages of 18 and 57 (M = 25.8, SD = 9.8). These participants were recruited at Purdue University from the same undergraduate student population. They self-identified as native and monolingual speakers of Midwestern English without significant knowledge of other languages. Although all had some experience of learning a second language in instructional settings (most often Spanish or French), this experience was current or recent for only three participants.

None of the participants in either experimental or control group reported a hearing or speech impairment, and all were compensated for participation with course credit or cash. The study was approved by the Purdue University and University of Kansas Institutional Review Boards, protocols 1409015219 and 00003743, respectively.

2.2. Elicitation Materials

Elicitation materials consisted of English and Russian minimal and near-minimal monosyllabic pairs contrasting word-initial and word-final voicing.

The 44 English pairs consisted of 18 stop-initial (e.g., cap–gap), 18 stop-final (e.g., mop–mob), 6 fricative-final (e.g., safe–save), and 2 affricate-final (e.g., rich–ridge) pairs. There was a total of 75 experimental items (some words were used in the word-initial and the word-final condition). Bilabial, alveolar, and velar stops were represented in equal numbers and final fricatives were labiodental (2 pairs) and alveolar (4 pairs). Preceding and following context was largely limited to the vowels [æ], [α], and [Λ]. There was no significant difference in lexical frequency between voiced and voiceless members of the pairs (COCA Corpus, Davis (2008)). Forty-eight mono- and disyllabic distractor items were also included. A complete list of English target stimuli is provided in Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2.

The 42 Russian pairs consisted of 18 stop-initial (e.g., [kostj]–[gostj] ‘bone’–‘guest’), 18 stop-final (e.g., [xrjip]–[grji

] ‘wheeze’–‘mushroom’), and 6 fricative-final pairs (e.g., [rjis]–[prjiz̥] ‘rice’–‘prize’), for a total of 84 experimental items. Bilabial, dental, and velar stops were represented in equal numbers and final fricatives were labiodental (1 pair) or alveolar (4 pairs). Preceding and following vowels were mid-low [e], [a], and [o] in about two-thirds of cases, the rest contained high vowels [i], [u], or [ɨ]. There were no significant differences in lexical frequency between voiced and voiceless stimuli (Russian National Corpus 2003). Forty-five mono- and disyllabic distractor items were also included. A complete list of target stimuli is provided in Appendix A, Table A3 and Table A4.

2.3. Procedure

Participants recorded at Purdue University were seated in front of the computer screen in a double-walled sound-attenuated booth. E-prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA) was used to display the words for elicitation. The words appeared on the screen one by one, in a random order. Each word stayed on the screen for 2 s and was followed by 0.5 s of blank screen. Participants were instructed to pronounce each word the way they speak normally. The whole list was presented three times to each participant with short breaks offered between the blocks. The recording was performed using an Audio-Technica AE4100 cardioid microphone and a TubeMP preamp connected directly to a PC.

For participants recorded at the University of Kansas, a similar procedure was used. PowerPoint software was used to present the prompts on the screen, in a random order for each participant, with each word displayed on the screen for 1.5 s, followed by 1.5 s of blank screen. Recordings were performed in an anechoic chamber, using an Electro-Voice N/D 767a microphone and Marantz PMD671 digital recorder.

This computer-controlled stimulus presentation elicits an appropriately consistent rate of speech across and within participants. The order of Russian and English conditions was counterbalanced across participants, with a brief break between conditions. Due to technical issues, only one repetition of each item was recorded for one experimental participant, and only English data were collected from another experimental participant.

2.4. Measurements

For initial stops, voice onset time (VOT) and onset f0 were measured. For final obstruents, preceding vowel duration, duration of consonantal constriction, and duration of voicing during constriction were measured. Segmentation was performed manually based on Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2018) waveform, and spectrogram representations and using standard segmentation criteria. Measurements were collected using custom-written Praat scripts.

VOT was measured from the onset of consonantal release until the onset of voicing. Onset f0 was measured at the vowel onset as soon as the Praat autocorrelation algorithm detected periodicity. Obtained f0 values were examined for algorithm errors and corrected manually if necessary. Normalization was performed by converting f0 values to semitones relative to each participant’s individual mean onset f0, using the formula 12ln(x/individual mean onset f0)/ln2, based on the semitone normalization procedure in Boersma and Weenink (2018). After normalization, outliers more than two standard deviations away from the normalized grand mean onset f0 were removed from further analysis (97% of onset f0 measurements were retained). The resulting values represented the deviation of each onset f0 value, on the logarithmic scale, from each participant’s mean, now represented as 0.

Duration of the preceding vowel, duration of the closure for stops/affricates, frication portion for fricatives/affricates, and duration of voicing during constriction were measured for final obstruents.

3. Results

All the reported Linear Mixed Models (LMM) were implemented in SPSS 26.0 with the same random effects structure: a random intercept for subject and for item. Significance of the fixed factors and interactions was assessed via ANOVA tests. All pairwise comparisons were performed with Sidak correction. To avoid averaging across positive and negative VOT values, separate statistical models were fit to stops with prevoicing and stops with positive VOT.

We report results for initial stops first, followed by results for final obstruents. Within each of those sections, we begin by reporting the comparison between learners’ Russian and English speech, to determine whether the two languages were produced by learners in a phonetically distinct way and to establish the degree of phonetic learning in their L2. We then proceed to report the comparison between learners’ English speech and English speech of monolingual controls to test for L1 drift in learners’ speech. We finish by reporting the correlations between the degree of phonetic learning in each learner’s L2 and the magnitude of L1 drift in his or her English speech.

3.1. Initial Stops

3.1.1. Learners’ Russian vs. English

The goal of this analysis was to establish whether learners’ Russian productions were acoustically distinct from their own English speech.

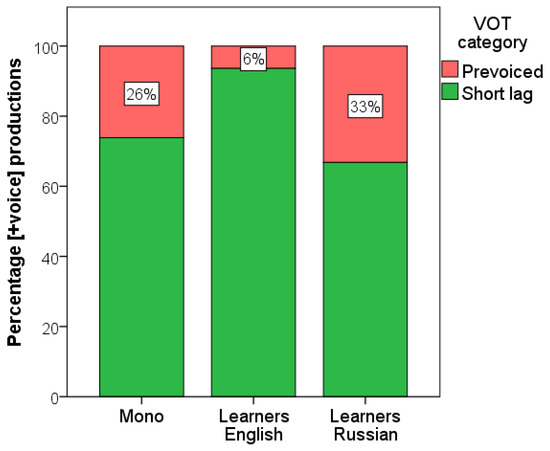

Positive VOT: Positive VOT of initial stops was analyzed using an LMM with Language (Russian vs. English), Voicing, Place of Articulation (included to account for systematic variability in VOT duration as function of place of articulation) and the two-way Language by Voicing interaction as fixed factors. The results demonstrated a significant effect of Language, F(1, 66.85) = 12.45, p = 0.001, Voicing, F(1, 66.65) = 690.39, p < 0.001, Place of Articulation, F(2, 66.46) = 34.13, p < 0.001, and a significant Language by Voicing interaction, F(1, 66.58) = 24.70, p < 0.001.

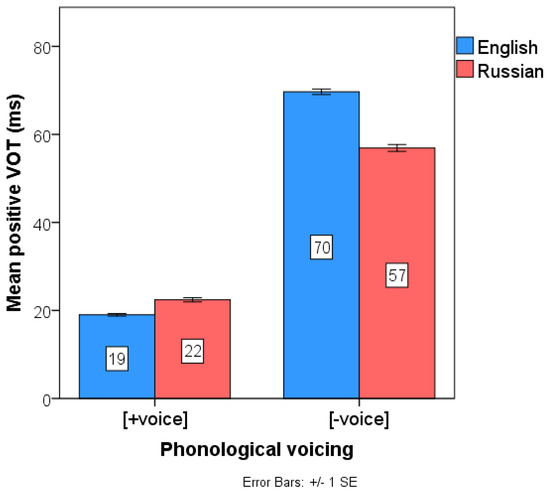

The effects of Voicing and Place of Articulation were due to a longer positive VOT for voiceless than for voiced stops and an increase in VOT in the following order: labial < coronal < dorsal, where every pairwise comparison was statistically significant. The effect of Language was due to longer VOTs in English (M = 45 ms, SD = 30 ms) than in Russia (M = 43 ms, SD = 28 ms). This effect was mostly driven by differences between the voiceless stops, while voiced stops were produced with more comparable VOTs across languages (see Figure 1). The significant Language by Voicing interaction confirms the magnitude of this asymmetry. The shortened VOT of initial voiceless stops produced in Russian indicated that learners were in the process of acquiring the phonetics of the Russian voiceless category, by targeting shorter lag productions. However, with a mean of 57 ms their Russian realizations were only 13 ms away from their English long lags (M = 70 ms) and still far from being true Russian-like voiceless stops.

Figure 1.

Mean positive voice onset time (VOT) of voiced and voiceless initial stops in learners’ English and Russian.

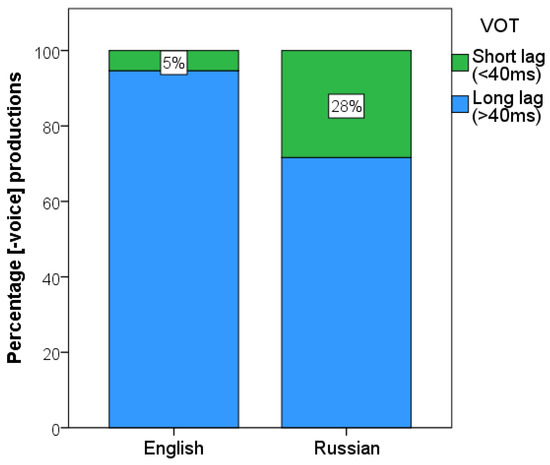

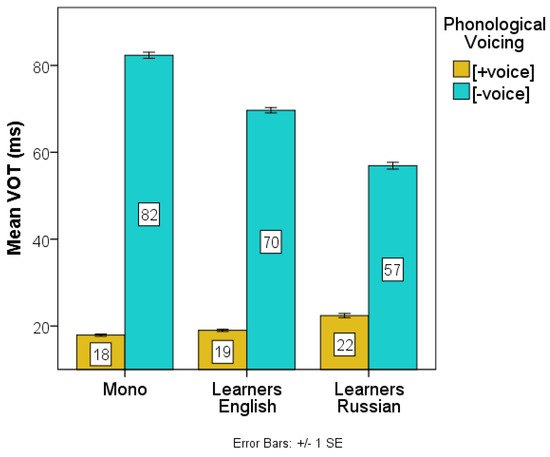

Given that Russian voiceless productions were, on average, shorter in VOT than English ones, another important question is how many instances of learners’ Russian stops could be categorized as ‘short lag’. Using a relatively generous cut-off of 40 ms (to accommodate for the lower rate of speech in isolated word production and the longer VOT of velar stops) to demarcate the boundary between short lag and long lag voiceless stops (Lisker and Abramson 1964), we calculated the proportions of such realizations in participants’ Russian and English speech. Figure 2 shows the distribution. While only 5% of short lags were detected among English voiceless stops, in Russian the proportion rose to 28%, indicating that appreciable VOT shortening affected almost a third of Russian productions. This asymmetry was significant in a chi-square test, χ2(1, N = 2155) =200.61, p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Percentage of short lag productions among [−voice] stops in learners’ English and Russian.

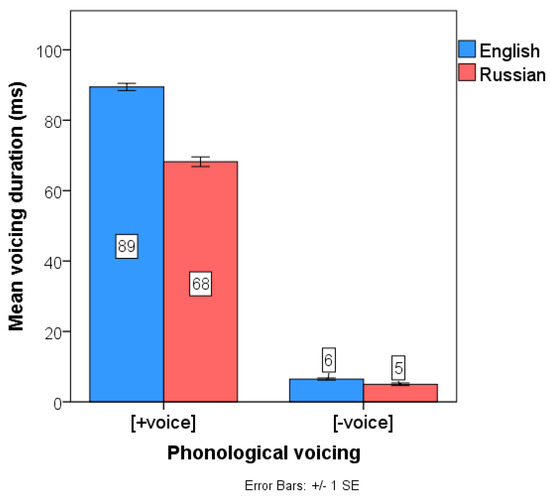

Negative VOT: Negative VOT of initial [+voice] stops was analyzed using an LMM with Language and Place of Articulation as fixed factors to establish whether the duration of prevoicing differed between learners’ Russian and English speech. The results showed a significant effect of Language, F(1, 101.85) = 21.10, p < 0.001. Russian [+voice] stops were characterized by a longer prevoicing period (M = 100 ms, SD = 37 ms) than English initial [+voice] stops (M = 78 ms, SD = 27 ms). Thus, although both English and Russian license prevoiced stops as representatives of the [+voice] category, they were phonetically distinct in the realizations of these American learners of Russian.

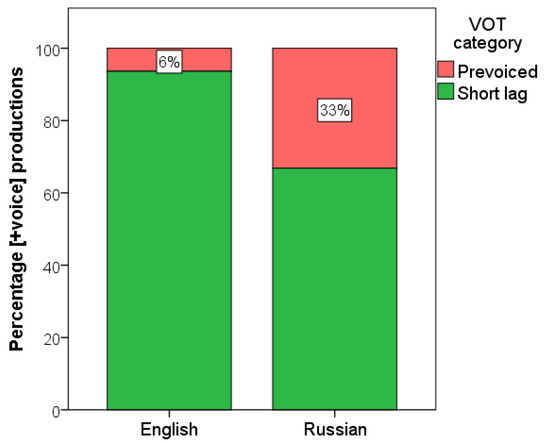

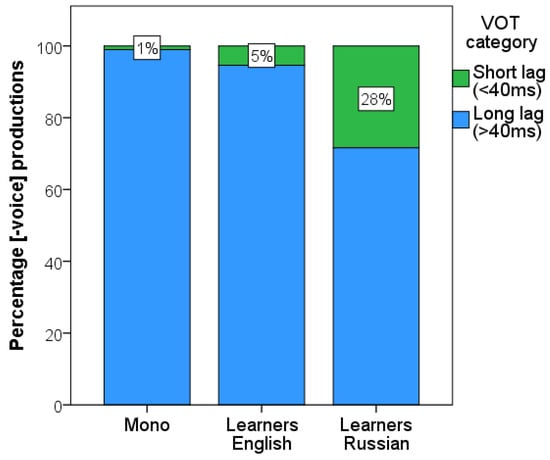

The frequency of prevoicing is another cross-linguistically distinguishing aspect, since all Russian [+voice] stops are supposed to be produced with prevoicing. To determine the extent to which learners reached this objective, we calculated the proportion of prevoiced realizations among [+voice] Russian and English stops, shown in Figure 3. While only 6% of English voiced stops were realized with prevoicing, 33% of Russian realizations were prevoiced, suggesting that learners were producing prevoiced realizations of Russian [+voice] stops, although well below the rate of native speakers.

Figure 3.

Percentage of prevoiced productions among [+voice] stops in learners’ English and Russian.

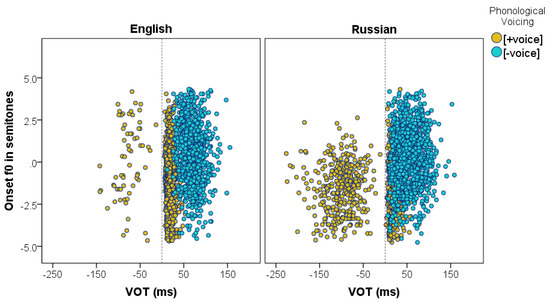

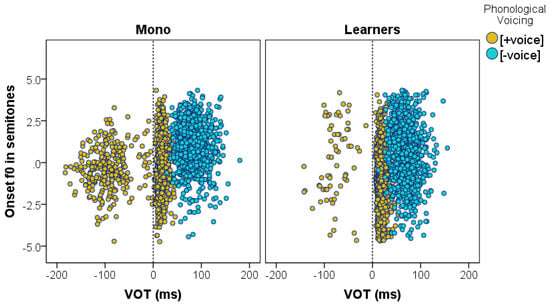

Onset f0: Figure 4 demonstrates the distribution of normalized onset f0 values in the English and Russian speech of the same participants. A few differences between the languages are apparent. First, prevoiced stops form a more substantial category in Russian than in English, with the distribution visibly shifted towards lower f0 values, compared to the English prevoiced distribution. Second, the Russian [−voice] distribution is less compact than the English one in terms of VOT range, encompassing a span of shorter values (up to 0 ms VOT) and, as a result, overlapping with [+voice] stops produced at short lags. The two distributions (Russian [+voice] short lags and Russian [−voice]) nevertheless maintain a separation in terms of f0 values, with visibly lower f0 of [+voice] short lags.

Figure 4.

Scatterplots of onset pitch at the beginning of the post-consonantal vowel (f0) and VOT values for learners’ English and Russian initial stops.

To examine the alignment of onset f0 values with both the phonological voicing and VOT categories in the two languages of learners, their normalized f0 values were analyzed in an LMM with Language, Voicing, and Language by Voicing interaction as fixed factors. In this analysis, Voicing was a hybrid category with three levels ([+voice] stops were split into those with prevoicing and those without): [+voice] prevoiced, [+voice] short lag, and [−voice]. This was motivated by the fact that the two types of [+voice] stops have very distinct VOT implementations and may be expected to behave differently in Russian where prevoiced stops form a separate phonological category to the exclusion of short lag stops.

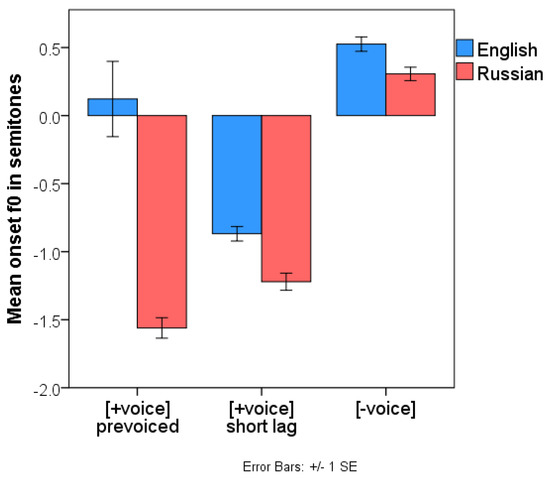

The results demonstrated a significant effect of Language, F(1, 104.85) = 25.52, p < 0.001, and Voicing, F(2, 192.07) = 104.79, p < 0.001, and a significant Language by Voicing interaction, F(2, 190.10) = 4.48, p = 0.013. Onset f0 was significantly lower in Russian than in English. The effect of Voicing was driven by significantly higher onset f0 after voiceless stops compared to either prevoiced or short lag [+voice] stops, without a significant difference between the latter. The interaction between Language and Voicing was triggered by the divergent behavior of f0 after prevoiced stops. As shown in Figure 5, Russian prevoiced stops lowered f0 even more than English prevoiced stops.

Figure 5.

Mean onset f0 across the three categories of initial stops in learners’ English and Russian.

To investigate this tendency further, we compared prevoiced and [+voice] short lag stops in English and in Russian separately, in LMM analyses with a single fixed effect: VOT category. The difference was significant only in Russian, F(1, 1068.69) = 25.63, p < 0.001, where prevoiced stops triggered lower onset f0 than short lag stops, being members of the same phonological category. This result suggests that learners of Russian were developing an awareness of prevoicing as a separate phonological category in Russian and attempting to single it out with a distinct f0 pattern.

We were further interested in onset f0 of [−voice] short lags. The question of interest here is whether, when producing Russian short lags, learners transfer all the co-varying properties of English initial short lags, including low f0.

We compared f0 values of Russian [+voice] short lags, Russian [−voice] short lags (<40 ms), and Russian [−voice] long lags (>40 ms) in an LMM model with a single fixed factor with these three levels. The effect was significant, F(2, 70.33) = 34.83, p < 0.001, and the results of pairwise comparisons demonstrated that f0 was significantly higher after both voiceless categories than after the voiced one, without a significant difference between the two voiceless categories.

Interim summary: The results demonstrated that learners were attempting to approximate Russian phonetic norms by producing (a) shorter VOTs in Russian [−voice] stops, (b) longer prevoicing in Russian [+voice] stops, (c) more instances of [−voice] stops with short lag VOT in Russian than in English and (d) more instances of [+voice] stops with prevoicing in Russian than in English. The acoustics of learners’ Russian stops were significantly different from their English stops. However, they were clearly not reaching native-like phonetic norms (all short lag [−voice] stops and all prevoiced [+voice] stops).

Onset f0 findings indicate that learners were able to manipulate the two correlates of voicing—VOT and onset f0—separately from each other. In particular, they did not transfer the low onset f0 associated with initial short lag stops in English to Russian when producing Russian short lags. Instead, they assigned onset f0 values in accordance with the phonological membership of the intended stop, equally successfully in Russian and in English. One result that deserves special notice is the significantly lower onset f0 assigned to Russian prevoiced [+voice] stops compared to Russian [+voice] short lags. These two sets of realizations were not distinguished via onset f0 in native English; thus, the difference is specific to the Russian productions of learners.

3.1.2. Learners’ English vs. Monolingual Controls’ English

The goal of this analysis is to determine whether learners’ productions of initial English stops were affected by exposure to Russian. This effect would be revealed if significant differences were demonstrated in the acoustic realization (in terms of VOT and onset f0) of initial English stops by the two speaker groups (learners’ English vs. monolingual English).

Positive VOT: Positive VOT of initial stops was analyzed using an LMM with Group (Learners vs. Monolinguals), Voicing, Place of Articulation, and Group by Voicing interaction as fixed factors. The results demonstrated a significant effect of Group, F(1, 35.87) = 6.73, p = 0.014, Voicing, F(1, 32.64) = 2364.47, p < 0.001, PA, F(2, 32.43) = 33.75, p < 0.001, and a significant Group by Voicing interaction, F(1, 3828.06) = 182.54, p < 0.001. The effects of Voicing and Place of Articulation demonstrated a longer VOT for voiceless stops and an increase in VOT in the following order: labial < coronal < dorsal, where every pairwise comparison was statistically significant.

The effect of Group demonstrated a longer overall VOT produced by monolingual participants (M = 59 ms, SD = 35 ms) than by learners (M = 45 ms, SD = 30 ms) (this effect was driven primarily by voiceless stops). The significant interaction between Group and Voicing was due to the fact that voiced stops were produced with comparable VOT values across the two groups, while voiceless stops had longer VOT for monolinguals than for learners. Moreover, as Figure 6 shows, learners’ mean voiceless VOT in English was situated between that of monolinguals and their own Russian productions. The shortened voiceless VOT of learners’ English is compatible with an influence of Russian, where the voiceless category is realized via short lag VOT.

Figure 6.

Mean positive VOT of voiced and voiceless initial stops in the English of monolingual controls and learners; learners’ Russian is provided for comparison.

To assess the possible role of elicitation order, an LMM was conducted on English data from learners only, with Order of language elicitation (Russian first or English first), Voicing, and Voicing by Order as fixed effects (all subsequent analyses of Order were conducted with the same model structure). The results confirmed the effect of Voicing, F(1, 34.075) = 658.189, p < 0.001, but showed no main effect of Order. The Voicing by Order interaction was significant, F(1, 2027.94) = 15.89, p < 0.001, due to the fact that in the Russian-first condition, learners’ [+voice] English stops were pronounced with longer VOT than in the English-first condition. This result agrees with the observation that learners produced relatively long VOTs for short lag [+voice] stops in Russian (see Figure 6), thus their Russian pronunciation tendencies for these types of stops spilled over into English when it was spoken next. The results therefore revealed no evidence that drift towards shorter VOTs in learners’ English was triggered by speaking Russian immediately prior to speaking English.

We were also interested in assessing how many of the English voiceless stops produced by learners could be categorized as ‘short lag’ as a result of this drift. We used a cut-off value of 40 ms, which categorized 99% of the voiceless stops produced by control speakers as long lags. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 7, the proportion of short lags was slightly higher for learners than for monolinguals. This asymmetry was significant in a chi-square test, χ2(1, N = 2028) = 30.24, p < 0.001. Thus, about 5% of stops produced by learners were on the margins of the long lag category, moving into the short lag territory.

Figure 7.

Percentage of short lag productions among [−voice] stops in monolingual controls’ and learners’ English; learners’ Russian is provided for comparison.

Negative VOT: Negative VOT of initial stops was analyzed using an LMM with Group and Place of Articulation as fixed factors to determine whether the duration of prevoicing in learners of Russian differed from that of monolingual controls. Neither factor was a significant predictor of prevoicing duration.

VOT categories in voiced stops: Figure 8 shows that monolingual controls produced prevoicing with almost equal frequency as learners did in their Russian productions (about 30%). In comparison, learners’ English was almost devoid of prevoicing, with only 6% prevoiced stops. This asymmetry between controls and learners’ English was significant in a chi-square test: χ2(1, N = 2230) = 158.38, p < 0.001.

Figure 8.

Percentage of prevoiced productions among [+voice] stops in monolingual controls’ and learners’ English; learners’ Russian is provided for comparison.

Moreover, when learners’ English productions were split by order of language elicitation, the Russian-first condition resulted in only 3% prevoicing in English, compared to 9% in the English-first condition. These results point towards a possibility of divergence from Russian in learners’ English speech; a divergence which can be amplified if Russian is elicited first. Exposure to Russian, where prevoicing marks a separate phonological category, led learners to decrease the incidence of allophonic prevoicing in their English speech.

Onset f0: Figure 9 demonstrates the distribution of onset f0 values and VOT values in English speech of learners and monolingual controls. The two groups present relatively comparable pictures, with the exception of a more substantial prevoiced distribution in controls than in learners and a greater separation between positive VOT categories in monolinguals than in learners. As discussed above, these tendencies are likely due to learners’ drift towards shorter VOT in their voiceless productions due to convergence with Russian, and a decrease in the incidence of prevoicing as an expression of divergence from Russian. Learners also demonstrate greater variability in onset f0 values, especially in [−voice] long lag stops.

Figure 9.

Scatterplots of onset f0 and VOT values in English productions of learners and monolingual speakers.

Onset f0 values in English productions of learners and monolingual controls were compared in an LMM analysis with Group and Voicing (three categories: [+voice] prevoiced, [+voice] short lag, and [−voice]) and Group by Voicing interaction as fixed factors. The results showed a significant effect of Voicing, F(2, 108.63) = 108.10, p < 0.001, due to a significant difference between [−voice] stops and the two [+voice] categories, with no significant difference between the latter two. No other effects or interactions reached significance. This result suggests that experience with Russian did not significantly affect the way learners realized onset f0 in their English speech.

Interim summary: The results revealed significant differences between learners and monolinguals which can be attributed to convergence and divergence with Russian in learners’ English. These differences affected only VOT, while English onset f0 was not affected by exposure to Russian.

Specifically, VOT of learners’ voiceless stops was shortened, moving towards their own Russian productions. Learners’ voiced stops, in contrast, tended towards divergence: not in terms of VOT values (VOT of [+voice] stops, including duration of prevoicing, was not affected) but in terms of prevoicing frequency. Learners produced significantly fewer prevoiced stops in English than monolingual controls. Combined with the fact that learners’ Russian prevoiced stops were marked by extra-low onset f0, these findings suggest that learners were targeting prevoiced stops as a distinct non-native category.

There was some evidence for the role of elicitation order: A decrease in the number of prevoiced stops in English was amplified if Russian elicitation occurred immediately prior.

3.1.3. Individual Variability in Drift

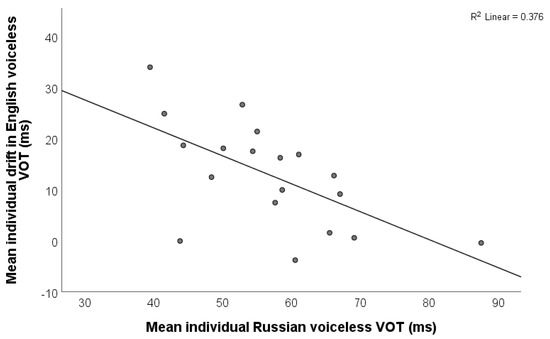

The initial stop measures, which showed evidence of L1 drift, included positive VOT of voiceless stops and the frequency of prevoicing in voiced stops. Therefore, we focused on these parameters in evaluating individual drift and its covariation with subjective and objective measures of Russian pronunciation proficiency.

To estimate the magnitude of L1 drift in each participant, we subtracted each learner’s mean English voiceless VOT from the grand mean voiceless VOT of all monolingual participants. The resulting value represented how much each learner deviated in their voiceless VOT from the average monolingual norm (greater values represent greater deviation from English monolingual long lag norms and greater approximation of Russian short lag norms).

These values were checked for correlation with each learner’s average Russian voiceless VOT. The prediction tested is that learners who were more successful in shortening their Russian voiceless VOT are also expected show a greater amount of drift in their English voiceless VOTs.

The results of the two-tailed Pearson correlation analysis showed a significant negative correlation between the individual drift and individual Russian voiceless VOT (r = −0.613, p = 0.005). Figure 10 shows that participants with the shortest Russian voiceless VOTs demonstrated the greatest L1 drift in the direction of Russian short lag norms.

Figure 10.

Correlation between individual L1 drift in English voiceless VOT (y-axis; larger values indicate greater drift towards Russian-like short lag VOT) and individual Russian voiceless VOT (x-axis).

We also checked the magnitude of drift parameter for correlations with self-estimated Russian speaking proficiency and self-estimated accentedness (subjective measures), where proficiency and accentedness scores on a seven-point scale were treated as continuous parameters, but neither revealed significant co-dependencies. A similar analysis was conducted for individual frequency of prevoicing across learners’ two languages, with no significant results.

Interim summary: Correlation analyses of initial stop data indicated that for VOT of voiceless stops, the magnitude of individual L1 drift was significantly correlated with pronunciation proficiency in Russian, when the latter was measured objectively via acoustic analysis.

3.2. Final Stops

3.2.1. Learners’ Russian vs. English

Similar to the analysis of initial stops, the examination of the acoustic correlates of final voicing assessed whether and to what extent the learners approximated the goal of neutralizing the voicing distinction in word-final position in Russian, while maintaining the contrast in English.

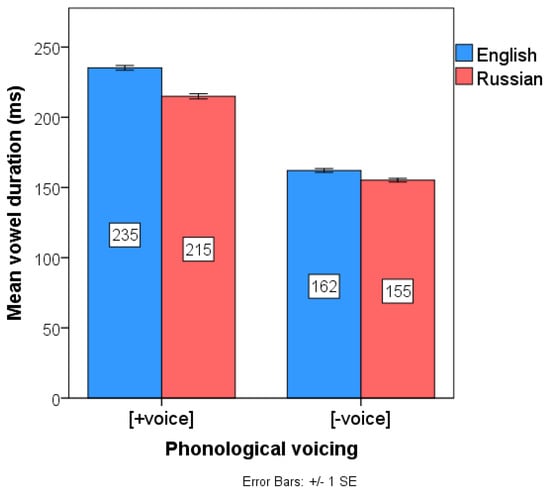

Vowel duration: Duration of the vowel preceding final obstruents was analyzed using an LMM with Language, Voicing, and Language by Voicing as fixed factors. The results demonstrated a significant effect of Voicing, F(1, 90.19) = 10.01, p = 0.002, and a significant Language by Voicing interaction, F(1, 90.18) = 13.20, p < 0.001. Vowels were significantly longer before voiced (M = 226 ms, SD = 67 ms) than before voiceless obstruents (M = 159 ms, SD = 52 ms). The difference was greater in learners’ English than in their Russian (see Figure 11), explaining the Language by Voicing interaction, and indicating that learners were approximating a reduction in the voicing distinction in Russian, by shortening vowels in the voiced context. While this modification is consistent with partial devoicing of [+voice] final obstruents in Russian, complete neutralization was clearly not achieved.

Figure 11.

Mean vowel duration before voiced and voiceless final obstruents in learners’ English and Russian.

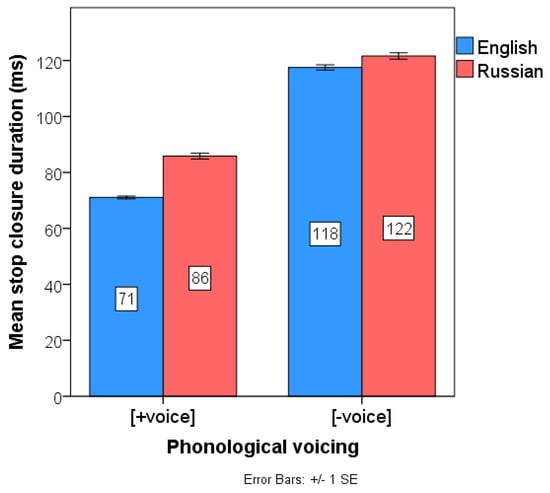

Constriction duration: Stop closure duration and fricative frication duration were analyzed in two separate LMMs with Language, Voicing, and Language by Voicing as fixed factors. Affricates were absent from this analysis because none were included among the Russian stimuli.

The results for closure duration demonstrated a significant effect of Voicing, F(1, 69.67) = 411.59, p < 0.001, Language, F(1, 75.94) = 61.85, p < 0.001, and a significant Language by Voicing interaction, F(1, 69.67) = 6.05, p = 0.016. Stop closure was significantly longer in voiceless (M = 119 ms, SD = 41 ms) than in voiced stops (M = 76 ms, SD = 28 ms). Closures were also significantly longer in learners’ Russian (M = 104 ms, SD = 40 ms) than in their English (M = 94 ms, SD = 41 ms). Finally, as Figure 12 demonstrates, the difference between voiced and voiceless closures was smaller in Russian than in English, at the expense of longer [+voice] closures in Russian, explaining the significant Language by Voicing interaction. Again, longer [+voice] Russian closures are compatible with partial devoicing of those stops in participants’ Russian speech.

Figure 12.

Mean voiced and voiceless final stop closure duration in learners’ English and Russian.

Results for frication duration showed no significant effects beyond that of Voicing, F(1, 18.99) = 35.36, p < 0.001: voiceless fricatives were significantly longer (M = 273 ms, SD = 60 ms) than voiced ones (M = 210 ms, SD = 58 ms).

Voicing duration: The duration of the closure or frication portion of the final obstruent characterized by laryngeal voicing (glottal pulsing), in ms, was submitted to an LMM analysis with Language, Voicing, and Language by Voicing as fixed factors. The results demonstrated a significant effect of Language, F(1, 95.53) = 7.28, p = 0.008, and Voicing, F(1, 99.99) = 678.34, p < 0.001, and a significant Language by Voicing interaction, F(1, 99.99) = 6.47, p = 0.013. English final obstruents contained more voicing (M = 48 ms, SD = 59 ms) than Russian final obstruents (M = 36 ms, SD = 48 ms). Voiced final obstruents had more voicing (M = 83 ms, SD = 55 ms) than voiceless ones (M = 6 ms, SD = 16 ms). The interaction was due to the fact that the difference between voiced and voiceless obstruents was greater in participants’ English than in their Russian speech, as shown in Figure 13. The voicing contrast between final obstruents in Russian was reduced via partial devoicing of the voiced obstruents.

Figure 13.

Mean duration of laryngeal voicing during closure or frication portion of the final voiced and voiceless obstruents in learners’ English and Russian.

Interim summary: The results for final obstruents overall demonstrated that learners attempted to implement voicing neutralization in their Russian productions. The preceding vowel duration, stop closure duration, and voicing during constriction demonstrated subphonemic but statistically significant tendencies towards partial devoicing of final [+voice] obstruents, although complete neutralization was not achieved. Thus, similarly to initial obstruents, we observed that participants aimed to implement appropriate phonetic differences between English and Russian final obstruents.

3.2.2. Learners’ English vs. Monolingual Controls’ English

Similar to initial stops, the goal of the analysis was to determine whether learners’ English productions were affected by exposure to Russian. If significant differences are detected between experimental and control groups in the acoustic implementation of final obstruents, these could suggest a ‘drift’ towards Russian norms.

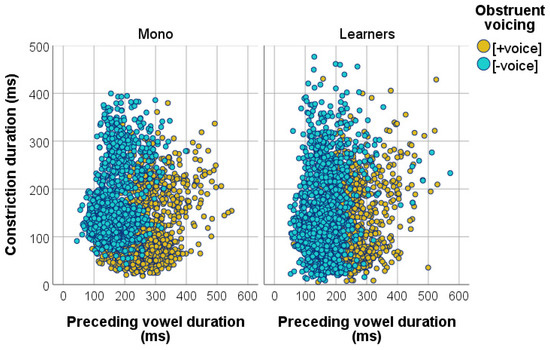

Figure 14 shows the distribution of voiced and voiceless final obstruents, based on the constriction duration (closure duration for stops and frication duration for fricatives) and preceding vowel duration, in the English speech of monolingual controls and learners of Russian. Although this display does not contain all datapoints (affricates were excluded due to extra-long constrictions and a relatively small number of tokens), it provides a representative picture of the differences between monolingual speakers and learners. First, the learners’ distribution demonstrates a greater amount of variability in terms of constriction duration. However, most importantly, learners’ data demonstrate visibly less separation between the two voicing categories in both dimensions. This suggests that learners’ English is drifting towards a reduction in the final voicing contrast, at least in these two acoustic dimensions. The direction of the drift is consistent with an influence of Russian final voicing neutralization. To determine whether these tendencies were statistically significant, each dimension of contrast was subjected to statistical analysis.

Figure 14.

Scatterplot of constriction duration and preceding vowel duration for final stops and fricatives in English speech of monolingual controls and learners.

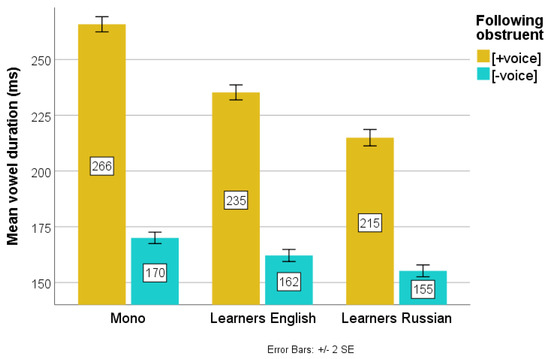

Vowel duration: Vowel duration was analyzed in an LMM with Group (Learners vs. Controls), Voicing, and Group by Voicing as fixed factors. The results demonstrated a significant effect of Group, F(1, 36.01) = 4.24, p = 0.047, Voicing, F(1, 802.35) = 8.51, p = 0.004, and a significant Group by Voicing interaction, F(1, 5961.38) = 140.31, p < 0.001. Vowels were significantly longer before voiced (M = 250 ms, SD = 68 ms) than before voiceless obstruents (M = 166 ms, SD = 51 ms). Monolingual speakers produced longer vowels (M = 219 ms, SD = 75 ms) than learners (M = 199 ms, SD = 70 ms). The interaction revealed that the vowel duration difference as a function of consonant voicing was greater for monolingual speakers than for learners. This suggests that learners experienced drift towards Russian norms evidenced by partial devoicing of [+voice] obstruents in terms of preceding vowel duration (see Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Mean vowel duration before voiced and voiceless obstruents in monolingual controls’ and learners’ English; learners’ Russian productions are provided for comparison.

To address the role of elicitation order in the emergence of L1 drift, we conducted an LMM analysis of vowel duration within the group of learners with fixed factors of Voicing, Order (Russian-first or English-first), and Voicing by Order. The results confirmed a significant effect of Voicing, F(1, 641.98) = 16.09, p < 0.001, but showed no other significant effects.

Constriction duration: Duration of closure (for stop consonants and affricates) and duration of frication (for fricatives and affricates) were analyzed in two separate LMM analyses with Group (Monolinguals vs. Learners), Voicing, and Group by Voicing as fixed factors.

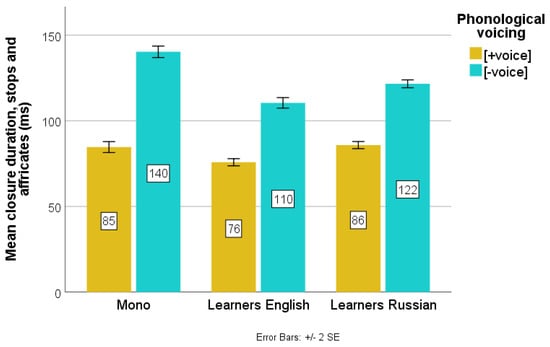

Analysis of closure duration demonstrated a significant effect of Voicing, F(1, 40.98) = 28.08, p < 0.001, Group, F(1, 35.82) = 9.26, p = 0.004, and a significant Group by Voicing interaction, F(1, 4457.49) = 82.83, p < 0.001. Voiceless stops and affricates had significantly longer closures (M = 125 ms, SD = 56 ms) than voiced ones (M = 80 ms, SD = 44 ms), but this difference was considerably more pronounced in monolinguals’ than in learners’ English, explaining the interaction. As Figure 16 shows, the average difference in closure duration between voiced and voiceless categories was smaller in learners’ than in monolinguals’ English, and was more comparable to the amount of contrast realized in learners’ Russian speech. The reduction in contrast in learners’ speech occurred by shortening voiceless closures.

Figure 16.

Mean voiced and voiceless closure for final stops and affricates in monolingual controls’ and learners’ English productions; learners’ Russian productions are provided for comparison.

The Order analysis for closure duration revealed no effects beyond the expected effect of Voicing, F(1, 38.01) = 68.86, p < 0.001.

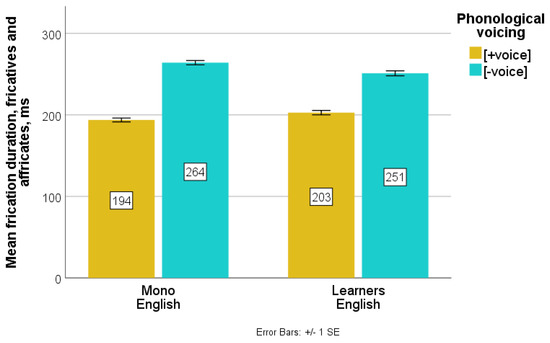

Analysis of frication duration demonstrated a significant effect of Voicing, F(1, 65.38) = 9.80, p = 0.003, and a significant Group by Voicing interaction, F(1, 1756.68) = 32.18, p < 0.001. Voiceless fricatives and affricates presented significantly longer frication duration (M = 257 ms, SD = 62 ms) than voiced ones (M = 198 ms, SD = 54 ms) and the difference was more pronounced in monolinguals’ than in learners’ English (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Mean voiced and voiceless frication for final fricatives and affricates in monolingual controls’ and learners’ English productions.

The Order analysis showed no significant effects of Voicing, Order, or Voicing by Order. This result indicates that the order of language presentation did not affect the magnitude of drift in learners’ L1 for fricative duration. The absence of significant Voicing effect also suggests that voicing-dependent differences in final frication duration could be completely neutralized in learners’ English speech.

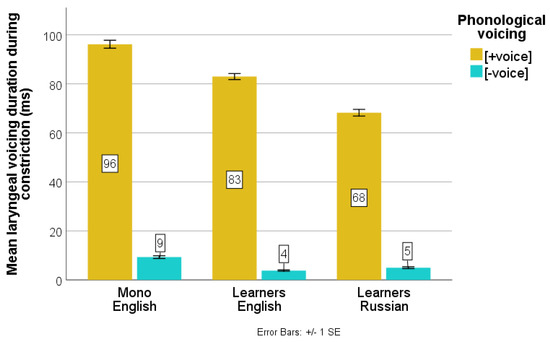

Voicing duration: The duration of glottal pulsing during the frication or closure portion of stops, affricates, and fricatives was analyzed in an LMM with Group, Voicing, and Group by Voicing as fixed factors. The results showed an effect of Voicing, F(1, 57.38) = 321.56, p < 0.001, and a Group by Voicing interaction, F(1, 5970.59) = 19.89, p < 0.001. Significantly more laryngeal voicing was detected during the constriction portion of phonologically voiced (M = 90 ms, SD = 57 ms) than voiceless (M = 7, SD = 17) final obstruents. This difference was more pronounced in the speech of monolingual participants than learners, explaining the interaction. As Figure 18 demonstrates, less laryngeal voicing was found in the learners’ final [+voice] obstruents than in those of monolinguals, although the reduction was not quite as great as in learners’ Russian speech.

Figure 18.

Mean duration of voicing during constriction of final obstruents in monolingual controls’ and learners’ English; learners’ Russian is provided for comparison.

The Order analysis for voicing duration confirmed the effect of Voicing, F(1, 57.38) = 321.56, p < 0.001, and revealed a Voicing by Order interaction, F(1, 5970.59) = 19.89, p < 0.001, which, unexpectedly, was due to greater neutralization of the final voicing contrast in the English-first condition.

Interim summary: The results demonstrated that learners’ English has drifted towards Russian norms of final voicing neutralization in terms of preceding vowel duration, closure duration, frication duration, and voicing during constriction of the final obstruents. In most cases, the magnitude of contrast was reduced compared to monolingual controls but the contrast itself was nevertheless maintained. Only in the case of frication duration did the contrast between voiced and voiceless consonants approach complete neutralization in the English speech of learners.

The effects of order of language elicitation were few and inconsistent. In the case of preceding vowel duration, eliciting Russian first has increased the drift effect in English, while in the case of voicing during constriction, eliciting English first led to a greater drift effect in English.

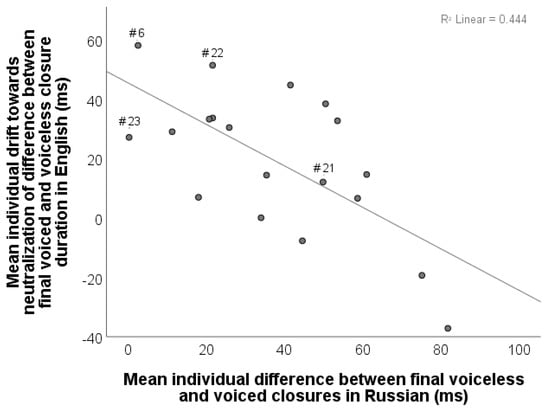

3.2.3. Individual Variability and Drift

The final obstruent measures which showed evidence of drift included preceding vowel duration, closure duration, frication duration, and duration of voicing during closure/frication. These parameters were evaluated for correlations between degree of individual drift and Russian pronunciation proficiency.

Russian pronunciation proficiency was evaluated objectively, as an individual acoustic difference between average voiced and average voiceless productions, and subjectively, as a self-reported speaking proficiency score and accentedness score.

The individual degree of drift was estimated by subtracting, for each participant, the average voiced-voiceless difference from the grand average monolingual voiced-voiceless difference (thus obtaining a ‘difference of differences’). Similar calculations were conducted for vowel duration, closure duration, frication duration, and duration of voicing during closure/frication (in all calculations of the voiced-voiceless difference, a smaller value was always subtracted from a larger one, e.g., vowel duration before voiceless obstruents was subtracted from vowel duration before voiced obstruents but voiced closure was subtracted from the voiceless closure).

Calculated in this manner, the individual values for drift were larger if a participant produced a smaller amount of durational difference in a given parameter between the voiced and voiceless obstruent, i.e., if they drifted more in the direction of Russian final voicing neutralization, as compared to an average monolingual difference.

Two-tailed Pearson correlational analyses revealed a significant negative relationship between individual drift in vowel duration (r = −0.539, p = 0.017), closure duration (r = −0.666, p = 0.002), and voicing duration (r = −0.463, p = 0.046) and the voiced-voiceless difference in these parameters in their Russian speech. In other words, those participants who drifted the most towards Russian neutralization norms in their English were also the ones who neutralized the same parameter more successfully in their Russian speech. Figure 19 illustrates the relationship for closure duration. Interestingly, in all three analyses, it was always a subset of the four learners (# 6, 21, 22, and 23) who had lived in Russia who consistently demonstrated the strongest drift, the greatest pronunciation gains, or both (e.g., Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Correlation between average individual L1 drift towards the reduction in voiceless-voiced closure duration difference in final stops/affricates and average individual difference between final voiceless and voiced closures in Russian (y-axis: larger values indicate greater drift towards Russian-like contrast neutralization; x-axis: larger values indicate greater distinction between voiced and voiceless obstruents). Labelled datapoints are participants who had lived in Russia.

The amount of drift in all of these parameters, except voicing duration, also correlated significantly with self-estimated Russian speaking proficiency (r = 0.526, p = 0.017 for vowel duration and r = 0.514, p = 0.020 for closure duration), such that participants with high self-estimated Russian proficiency were the ones who drifted towards Russian the most in their English. No measure of drift correlated with the self-estimated degree of accentedness in Russian.

Interim summary: For three acoustic correlates of the final voiced-voiceless distinction, correlational analyses revealed a significant dependency between the amount of L1 drift and the degree of pronunciation proficiency in L2, as evaluated objectively via acoustic measures. In two of these cases, a subjective measure of pronunciation proficiency, namely self-evaluated speaking proficiency in Russian along a one- to seven-point Likert scale, also correlated with the magnitude of drift, suggesting that, at least in some cases, such simple self-reported data align with the objective acoustic measures.

3.3. Summary of the Results

The comparisons between Russian and English productions of L2 learners demonstrated that learners, as a group, were attempting to implement the phonetic differences between the two languages (as they pertain to the implementation of voicing in particular) in their Russian productions. At the same time, while producing acoustically distinct targets in their two languages, learners’ productions were still quite distinct from the Russian norms.

Despite the relatively modest gains in Russian pronunciation abilities, learners also demonstrated discernable effects of exposure to Russian in their English speech. Comparisons with a monolingual control group revealed significant differences in the majority of examined acoustic parameters. Most differences were compatible with the effect of Russian in the direction of convergence. Additionally, the individual magnitude of L1 drift in the direction of Russian norms was, in many cases, correlated with the degree of pronunciation gains in Russian speech: participants who could be considered more proficient speakers of Russian (as evaluated using acoustic measurements or self-reported speaking proficiency scores) demonstrated the greatest degrees of L1 drift.

4. Discussion

The present study examined native and second language speech of American learners of Russian in order to determine whether classroom exposure to L2 can lead to phonetic changes in learners’ L1.

First, to confirm that classroom exposure to L2 resulted in phonetic learning, as evidenced by effective separation of L1 and L2 systems in the speech of the participants, and to evaluate the degree of this learning, we conducted a comparison between the acoustics of learners’ Russian and English sounds. The results indicated that, for almost every measure taken, learners produced statistically distinct values in Russian and English. In Russian, their word-initial voiceless stops had shorter VOTs, their word-initial voiced stops had longer prevoicing, the frequency of prevoiced stops was higher, and prevoiced stops were characterized by extra-low onset f0, compared to English. Learners’ word-final voiced obstruents were also partially devoiced in Russian, compared to English. All of these modifications were in the direction of approximating native Russian norms: short lag voiceless stops, robustly and near-exclusively prevoiced voiced stops, lower onset f0 after prevoiced stops, and word-final devoicing.

The fact that distinct productions were obtained across learners’ L1 and L2 indicates that even at these relatively early stages of learning, taking place while immersed in L1, participants grasped the phonetic differences between similar phones across the languages and were attempting to implement them in their L2 speech. These results fit in with a wide array of similar findings for bilinguals and L2 learners, demonstrating not merged but distinct productions across the two languages (Baker and Trofimovich 2005; Flege and Eefting 1987a, 1987b; Fowler et al. 2008).

At the same time, it is clear that these learners were not near-native like in their L2 pronunciation by any measure. Their initial [−voice] stops were too aspirated and their initial [+voice] category was still dominated by short lag productions, instead of prevoiced ones. Their final [+voice] obstruents were also only slightly devoiced as opposed to fully devoiced, as expected in Russian speech. Therefore, using these acoustic measures, we can conclude that, at least with respect to pronunciation, these learners were not highly proficient/advanced in their L2.

The question remains whether we can expect L2-driven phonetic changes in the learners’ native speech for these non-advanced speakers immersed in the L1. The answer given by the present results is ‘yes’. A comparison of learners’ English to the native English monolingual group revealed acoustically subtle but statistically significant differences, all compatible with the influence of Russian. Learners’ initial [−voice] stops were characterized by shortened VOTs, indicating assimilation with Russian. Comparison of learners of Russian with the monolingual group also revealed a tendency to reduce the magnitude of the phonetic contrast between final voiced and voiceless obstruents. This reduction was implemented via partial devoicing of [+voice] final obstruents and is compatible with the effect of the Russian final devoicing process.

This finding suggest that L2 phonological rules can trigger phonetic changes in speakers’ L1. The present outcome may also have been helped by the fact that American English is already gravitating towards variable final devoicing, most strongly in fricatives (Davidson 2016), thus facilitating this particular back-transfer from Russian. It is interesting that there was no significant frication duration difference between voiced and voiceless fricatives and affricates in learners’ English. Thus, if learners have ‘drifted’ all the way into Russian-like complete neutralization (with respect to this parameter) then it was only in segments that are especially prone to devoicing in their L1. This finding warrants further research in order to learn more about the conditions under which phonological processes may seep from bilinguals’ L2 into their L1.

Interestingly, English [+voice] stops were not affected, neither short lag nor prevoiced ones. Only the frequency of prevoicing showed a change, notably, in the direction of dissimilation from Russian. A similar effect was reported by Huffman and Schuhmann (2016), who indicated that some American learners of Spanish produced fewer or no prevoiced stops in their English after 6 weeks of classroom Spanish instruction. This result merits attention because it demonstrates that L1 phonetic changes in the direction of dissimilation from L2 are possible even at the beginning stages of L2 acquisition—a possibility not provided for in SLM, which predicts that only advanced learners will dissimilate after having created separate categories for L2 sounds. Moreover, this finding indicates that the dissimilatory or assimilatory direction of crosslinguistic interaction can be determined not only by the stage of L2 acquisition but also by the sound category itself. Specifically, the present data suggest that L1 may tend towards dissimilation with L2 when L1 offers a choice of sub-phonemic variants of the same category only one of which is used in L2 to represent the same phonological category.

Overall, phonetic parameters affected by L1 drift were a subset of those used by participants to differentiate their L1 and L2, suggesting that L2 phonetic learning is a natural precursor of L1 drift.

The present evidence of L2-to-L1 phonetic effects in American learners of Russian indicates that even relatively dissimilar language pairings are subject to such phonetic interactions. Assimilatory changes in the acoustics of English obstruents suggest that despite great linguistic differences between the two languages overall and the use of different orthographic symbols for these sounds, Russian and English segments influenced each other. Orthography has been shown to play a powerful role in adult second language learning, which relies greatly on literacy and orthographic input, unlike first language acquisition (Bassetti and Atkinson 2015; Bassetti et al. 2015; Hayes-Harb et al. 2018). Nevertheless, the present study shows, in agreement with previous research on dissimilar language pairs such as English and Korean, that orthographic differences are not insurmountable obstacles for equivalence classification even in highly literate adult language learners. Equivalence classification between English and Russian obstruents, leading to cross-language assimilatory changes, could be facilitated by similarities in the phonological functioning of these segments in the respective languages. The two languages have similar sets of voiced and voiceless obstruents, which contrast initially and intervocalically but assimilate in voicing when in clusters and devoice, to different degrees, when in final position. Additionally, equivalent phonological categories across these two languages can be realized in phonetically identical ways, albeit in different contextual environments, e.g., English [−voice] stops can be implemented with short lag VOT word-medially before unstressed vowels, similarly to Russian [−voice] stops.