Short-Term Sources of Cross-Linguistic Phonetic Influence: Examining the Role of Linguistic Environment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Long-Term Sources of Cross-Linguistic Phonetic Influence

2.2. Short-Term Sources of Cross-Linguistic Phonetic Influence

2.3. Research Questions

RQ1: Does a short-term change in the linguistic environment impact phonetic production? For this study, a short-term change in linguistic environment is operationalized as a single speaker moving from an English-dominant linguistic environment to a Spanish-dominant linguistic environment (or vice-versa).

RQ2: Does proficiency in the L2 interact with linguistic environment?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Stimuli

- a. Te voy a leer este poema.‘I am going to read this poem to you.’

- b. ¿Doblaste a la derecha en la calle principal?‘Did you turn to the left on the main street?’

- c. Jaime comió los caramelos.‘Jaime ate the candies.’

3.3. Procedure

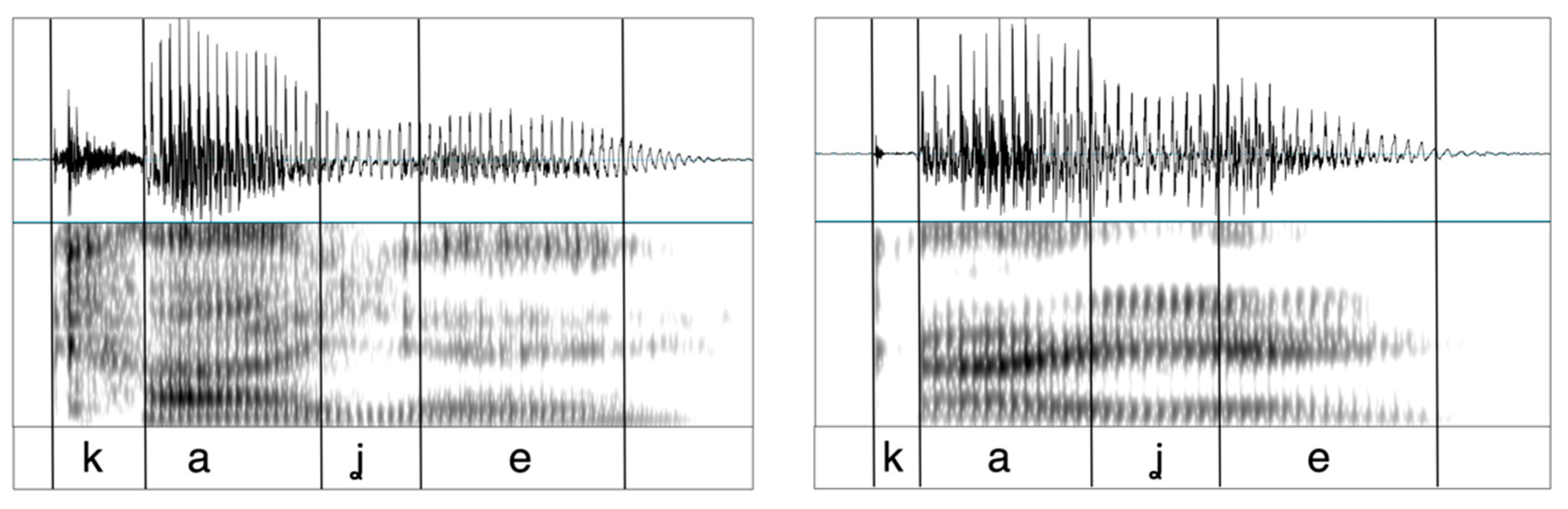

3.4. Voice Onset Time Analysis

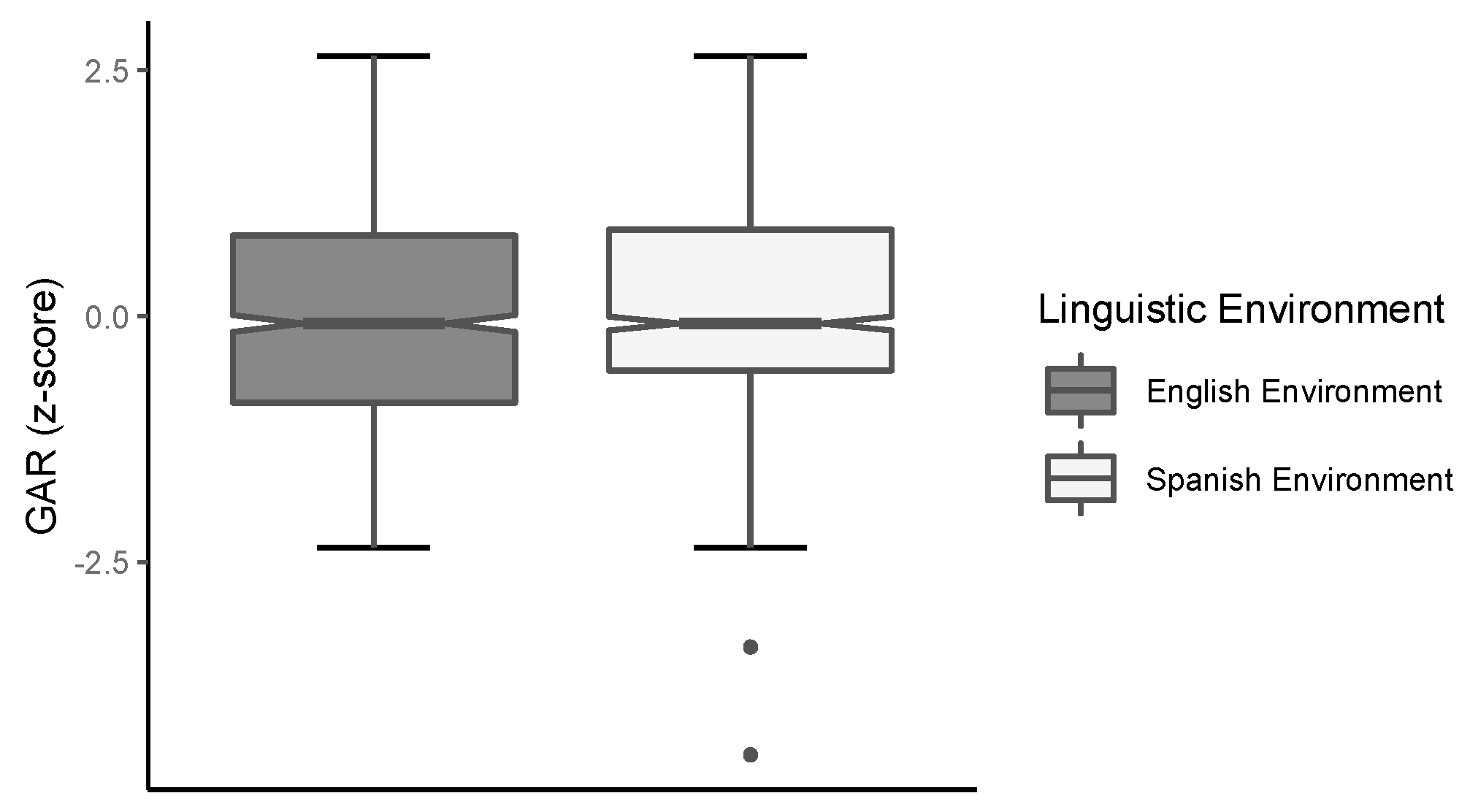

3.5. Global Accent Rating Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Voice Onset Time

4.2. Global Accent Rating

5. Discussion

Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Participant | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 172.98 | 13.15 | |

| Spanish Environment | 34.33 | 5.59 | −0.36 |

| Item | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 15.95 | 3.99 | |

| Spanish Environment | 5.36 | 2.31 | 0.09 |

Appendix B

| Participant | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 171.17 | 13.08 | |

| Spanish Environment | 37.17 | 6.10 | −0.39 |

| Item | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 15.95 | 3.99 | |

| Spanish Environment | 5.37 | 2.32 | 0.09 |

Appendix C

| Participant | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 0.399 | 0.632 | |

| Spanish Environment | 0.053 | 0.230 | −0.17 |

| Item | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 0.005 | 0.072 | |

| Spanish Environment | 0.014 | 0.119 | −0.2 |

Appendix D

| Participant | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 0.364 | 0.604 | |

| Spanish Environment | 0.056 | 0.238 | −0.22 |

| Item | Variance | Std. Dev. | Corr. |

| Intercept | 0.005 | 0.072 | |

| Spanish Environment | 0.014 | 0.119 | −0.2 |

References

- Amengual, Mark. 2012. Interlingual influence in bilingual speech: Cognate status effect in a continuum of bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 517–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual, Mark. 2016. Cross-linguistic influence in the bilingual mental lexicon: Evidence of cognate effects in the phonetic production and processing of a vowel contrast. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual, Mark. 2018. Asymmetrical interlingual influence in the production of Spanish and English laterals as a result of competing activation in bilingual language processing. Journal of Phonetics 69: 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, Mark, Catherine T. Best, Michael D. Tyler, and Christian Kroos. 2011. Inter-language interference in VOT production by L2-dominant bilinguals: Asymmetries in phonetic code-switching. Journal of Phonetics 39: 558–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babel, Molly, and Jamie Russell. 2015. Expectations and speech intelligibility. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 137: 2823–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balukas, Colleen, and Christian Koops. 2015. Spanish-English bilingual voice onset time in spontaneous code-switching. International Journal of Bilingualism 19: 423–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, Dale, Roger Levy, Christoph Scheepers, and Harry J. Tily. 2013. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language 68: 255–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Christopher, Amber Nota, Simone A. Sprenger, and Monika S. Schmid. 2016. L2 immersion causes non-native-like L1 pronunciation in German attriters. Journal of Phonetics 58: 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, Catherine T., and Michael Tyler. 2007. Nonnative and second-language speech perception. In Language Experience in Second Language Speech Learning: In Honour of James Emil Flege. Edited by Murray J. Munro and Ocke-Schwen Bohn. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. Austin: COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. Available online: http://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2018. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer. Version 6.0.37. Available online: http://www.praat.org (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Bullock, Barbara E., and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. 2009. Trying to hit a moving target: On the sociophonetics of code-switching. In Multidisciplinary Approaches to Code Switching. Edited by Ludmilla Isurin, Donald Winford and Kees de Bot. Amsterdam: John Benjamin, pp. 189–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, Barbara E., Almeida Jacqueline Toribio, Verónica González, and Amanda Dalola. 2006. Language dominance and performance outcomes in bilingual pronunciation. In Proceedings of the 8th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference. Edited by Mary Grantham O’Brien, Christine Shea and John Archibald. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Caramazza, Alfonso, Grace H. Yeni-Komshian, Edgar B. Zurif, and Ettore Carbone. 1973. The acquisition of a new phonological contrast: The case of stop consonants in French-English bilinguals. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 54: 421–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, Joseph V. 2020. The longitudinal development of fine-phonetic detail: Stop production in a domestic immersion program. Language Learning 70: 768–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, Joseph V., and Miquel Simonet. 2018. Perceptual categorization and bilingual language modes: Assessing the double phonemic boundary in early and late bilinguals. Journal of Phonetics 71: 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedrus Corporation. 2015. SuperLab Pro (Version 5.0.5) [Computer Program]. San Pedro: Cedrus Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Taehong, and Peter Ladefoged. 1999. Variation and universals in VOT: Evidence from 18 languages. Journal of Phonetics 27: 207–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Campos, Manuel. 2004. Context of learning in the acquisition of Spanish second language phonology. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 26: 249–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil. 1987. The production of “new” and “similar” phones in a foreign language: Evidence for the effect of equivalence classification. Journal of Phonetics 15: 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil. 1988. Factors affecting degree of perceived foreign accent in English sentences. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 84: 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil. 1991. Age of learning affects the authenticity of voice-onset time (VOT) in stop consonants produced in a second language. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 89: 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil. 1995. Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. In Speech Perception and Linguistic Experience: Issues in Cross-Language Research. Edited by Winifred Strange. Timonium: York Press, pp. 233–77. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, James Emil, and Wieke Eefting. 1987. Production and perception of English stops by native Spanish speakers. Journal of Phonetics 15: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil, and Robert Port. 1981. Cross-language phonetic interference: Arabic to English. Language and Speech 24: 125–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil, Murray J. Munro, and Ian R. A. MacKay. 1995. Factors affecting strength of perceived foreign accent in a second language. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 97: 3125–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, James Emil, Ian R. A. MacKay, and Diane Meador. 1999. Native Italian speakers’ perception and production of English vowels. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 106: 2973–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Carol A., Valery Sramko, David J. Ostry, Sarah A. Rowland, and Pierre Hallé. 2008. Cross language phonetic influences on the speech of French–English bilinguals. Journal of Phonetics 36: 649–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollan, Tamar H., and Victor S. Ferreira. 2009. Should I stay or should I switch? A cost–benefit analysis of voluntary language switching in young and aging bilinguals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 35: 640–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Kalim, and Andrew Lotto. 2013. A Barfi, un Pafri: Bilinuals’ pseudoword identifications support language-specific phonetic systems. Psychological Science 24: 2135–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-López, Verónica. 2012. Spanish and English word-initial voiceless stop production in code-switched vs. monolingual structures. Second Language Research 28: 243–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, David W., and Jubin Abutalebi. 2013. Language control in bilinguals: The adaptive control hypothesis. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 25: 515–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, Peter, and Catriona J. MacLeod. 2016. SIMR: An R package for power analysis of generalised linear mixed models by simulation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 7: 493–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, François. 1998. Studying bilinguals; methodological and conceptual issues. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 1: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, François. 2001. The bilingual’s language modes. In One Mind, Two Languages: Bilingual Language Processing. Edited by Janet Nicol. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 2008. Studying Bilinguals. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 2012. An attempt to isolate, and then differentiate, transfer and interference. International Journal of Bilingualism 16: 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, François, and Joanne L. Miller. 1994. Going in and out of languages: An example of bilingual flexibility. Psychological Science 5: 201–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guion, Susan G., Tetsuo Harada, and J. J. Clark. 2004. Early and late Spanish–English bilinguals’ acquisition of English word stress patterns. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 207–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Robert M. 2001. The Sounds of Spanish: Analysis and Application (with Special Reference to American English). Somerville: Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, Jennifer, and Katie Drager. 2010. Stuffed toys and speech perception. Linguistics 48: 865–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. 2019. Lenguas Maternas: Personas entre 18 y 64 años de edad según las lenguagas maternas más frequentes que tienen, por característica sociodemográfica. Available online: http://www.ine.es/jaxi/tabla.do?type=pcaxis&path=/t13/p459/a2016/p01/l0/&file=01016.px (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Jarvis, Scott, and Aneta Pavlenko. 2008. Crosslinguistic Influence in Language and Cognition. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, Ghada. 2002. /r/ production in English and Arabic bilingual and monolingual speakers. In Leeds Working Papers in Linguistics and Phonetics 9. Edited by Diane Nelson. Leeds: Leeds University, pp. 91–129. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, Ghada. 2009. Phonetc accommodation in children’s code switching. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code Switching. Edited by Barbara Bullock and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Cambridge: Cambridge University, pp. 142–60. [Google Scholar]

- Koops, Christian, Elizabeth Gentry, and Andrew Pantos. 2008. The effect of perceived speaker age on the perception of PIN and PEN vowels in Houston, Texas. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 14: 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl, Patricia K. 1992. Infants’ perception and representation of speech: Development of a new theory. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Spoken Language Processing. Edited by John J. Ohala, Terrance M. Neary, Bruce L. Derwing, Megan H. Hodge and Grace E. Wiebe. Edmonton: University of Alberta, pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl, Patricia K. 1993a. Infant speech perception: A window on psycholinguistic development. International Journal of Psycholinguistics 9: 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl, Patricia. K. 1993b. Innate predispositions and the effects of experience in Speech Perception. The Native Language Magnet Theory. In Developmental Neurocognition: Speech and Face Processing in the First Year of Life. Edited by Bénédicte de Boysson-Bardies, Scania de Schonen, Peter Jusczyk, Peter McNeilage and John Morton. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 259–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lafford, Barbara, and Joseph Collentine. 2006. The effects of study abroad and classroom contexts on the acquisition of Spanish as a second language. In The Art Of Teaching Spanish: Second Language Acquisition: From Research To Praxis. Edited by Barbara Lafford and Rafael Salaberry. Washington: Georgetown University Press, pp. 103–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Junkyu, Juhyun Jang, and Luke Plonsky. 2015. The effectiveness of second language pronunciation instruction: A meta-analysis. Applied Linguistics 36: 345–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisker, Leigh, and Arthur S. Abramson. 1964. A cross-language study of voicing in initial stops: Acoustical measurements. Word 20: 384–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, Gillian. 2005. (How) can we teach foreign language pronunciation? On the effects of a Spanish phonetics course. Hispania 88: 557–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, Gillian. 2010. The combined effects of immersion and instruction on second language pronunciation. Foreign Language Annals 43: 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, Andrea, and Carol Stoel-Gammon. 2005. Are bilinguals different? What VOT tells us about simultaneous bilinguals. Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders 3: 118–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, Roy C. 1992. Losing English as a first language. The Modern Language Journal 76: 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldner, Kasia, Leah Hoiting, Leyna Sanger, Lev Blumenfeld, and Ida Toivonen. 2019. The phonetics of code-switched vowels. International Journal of Bilingualism 23: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, Murray J., and Tracey M. Derwing. 1995. Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning 45: 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers-Scotton, Carol. 1997. Duelling Languages: Grammatical Structure in Codeswitching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagle, Charles L., Colleen Moorman, and Cristina Sanz. 2016. Disentangling research on study abroad and pronunciation: Methodological and programmatic considerations. In Handbook of Research on Study Abroad Programs and Outbound Mobility. Edited by Donna M. Velliaris and Deb Coleman-George. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 673–95. [Google Scholar]

- Niedzielski, Nancy. 1999. The effect of social information on the perception of sociolinguistic variables. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 18: 62–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Daniel J. 2013. Bilingual language switching and selection at the phonetic level: Asymmetrical transfer in VOT production. Journal of Phonetics 41: 407–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Daniel J. 2015. The gradient effect of context on language switching and lexical access in bilingual production. Applied Psycholinguistics 37: 725–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Daniel J. 2016. The Role of code-switching and language context in bilingual phonetic transfer. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 46: 263–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Daniel J. 2017. Bilingual language switching costs in auditory comprehension. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 32: 494–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Daniel J. 2019. Phonological processes across word and language boundaries: Evidence from code-switching. Journal of Phonetics 77: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Michel. 1993. Linguistic, psycholinguistic, and neurolinguistic aspects of ‘interference’ in bilingual speakers: The Activation Threshold Hypothesis. International Journal of Psycholinguistics 9: 133–45. [Google Scholar]

- Piske, Thorsten, Ian R. A. MacKay, and James Emil Flege. 2001. Factors affecting degree of foreign accent in an L2: A review. Journal of Phonetics 29: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piske, Thorsten, James Emil Flege, Ian R. A. MacKay, and Diane Meador. 2002. The production of English vowels by fluent early and late Italian-English bilinguals. Phonetica 59: 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Riney, Timothy J., and James E. Flege. 1998. Changes over time in global foreign accent and liquid identifiability and accuracy. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 20: 213–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, Hanna, and Sandra Peters. 2016. On the origin of post-aspirated stops: Production and perception of/s/+ voiceless stop sequences in Andalusian Spanish. Laboratory Phonology: Journal of the Association for Laboratory Phonology 7: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancier, Michele L., and Carol A. Fowler. 1997. Gestural drift in a bilingual speaker of Brazilian Portuguese and English. Journal of Phonetics 25: 421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Monika S., Steven Gilbers, and Amber Nota. 2014. Ultimate attainment in late second language acquisition: Phonetic and grammatical challenges in advanced Dutch–English bilingualism. Second Language Research 30: 129–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Geoffrey, Anna Balas, and Arkadiusz Rojczyk. 2015. Phonological factors affecting L1 phonetic realization of proficient Polish users of English. Research in Language 13: 181–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieter, John W., and Gretchen Sunderman. 2008. Language switching in bilingual speech production: In search of the language-specific selection mechanism. The Mental Lexicon 3: 214–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Ellen. 2009. Acquiring a new second language contrast: An analysis of the English laryngeal system of native speakers of Dutch. Second Language Research 25: 377–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonet, Miquel. 2014. Phonetic consequences of dynamic cross-linguistic interference in proficient bilinguals. Journal of Phonetics 43: 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, Carlos, and François Grosjean. 1984. Bilinguals in a monolingual and a bilingual speech mode: The effect on lexical access. Memory and Cognition 12: 380–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, Megan, and Avizia Y. Long. 2018. Acquisition of phonetics and phonology abroad: What we know and how. In The Routledge Handbook of Study Abroad: Research and Practice. Edited by Cristina Sanz and Alfonso Morales-Front. New York: Routledge, pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Stoehr, Antje, Titia Benders, Janet G. Van Hell, and Paula Fikkert. 2017. Second language attainment and first language attrition: The case of VOT in immersed Dutch–German late bilinguals. Second Language Research 33: 483–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2018. ACS 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables: Languages Spoken at Home. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Language%20Indiana&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S1601&hidePreview=false (accessed on 22 October 2020).

| 1 | For a discussion on the interaction between length of residence and other variables, notably age of acquisition, see Piske et al. (2001). As Piske et al. (2001) note, length of residence “only provides a rough index of overall L2 experience” (p. 197). While many studies talk about immersion, immigration, and length of residence, these may be used as a proxy for overall L2 experience. For the current study, it is relevant that these factors, whether conceptualized as L2 experience or length of residence, function as long-term sources of linguistic change and interaction. |

| 2 | In short, one group of participants was tested en route to the host country of the study abroad program (i.e., prior to leaving Indiana, USA, and upon arrival in Madrid, Spain) and one group of participants was tested en route to the home country (i.e., prior to leaving Madrid, Spain, and upon arrival in Indiana, USA). While this presents a potential confound, such that one group may have had a six-week “advantage” by participating following six weeks of immersion in the host country, statistical analysis controlled for between-participant differences with the random effects structure, effectively comparing each participant to her or himself. |

| 3 | Following suggestions by an anonymous reviewer, subsequent analysis was conducted with proficiency as a three-way categorical variable. Two different group cut-offs were considered. First, parallel to the subgroups in Figure 4, three approximately equal-sized proficiency groups were considered: low (n = 6), mid (n = 7), and high proficiency (n = 7). Second, three proficiency groups were identified using visual analysis of participant BLP Spanish score distributions: low (n = 5), mid (n = 12), and high proficiency (n = 3). Model comparison, following the procedure outlined below, showed that neither categorical approach to proficiency significantly improved model fit for either the VOT (equal sized groups: χ2(4) = 1.380, p = 0.848; unequal sized groups: χ2(4) = 7.427, p = 0.115) or the GAR analysis (equal sized groups: χ2(4) = 3.517, p = 0.475; unequal sized groups: χ2(4) = 5.690, p = 0.224) relative to a model without proficiency. As such, proficiency, regardless of operationalization, does not appear to significantly influence VOT or interaction with linguistic environment for this group of learners. |

| 4 | As the main goal of this project was to examine the effect of linguistic environment, the main analysis compares the productions of participants in two different linguistic environments. The two groups (i.e., US-Spain and Spain-US) served to counter-balance session order. As such, some group differences are possible as the Spain-US group was tested following six weeks in the Spanish linguistic environment. Addressing the possible effect of group, a subsequent model was conducted with linguistic environment and group as fixed effects,. Model comparison showed that the inclusion of group significantly improved model fit (χ2(2) = 7.395, p = 0.025). This is not unexpected, given that overall, the Spain-US group (M = 39.6 ms, SD = 18.3 ms) produced significantly shorter VOTs than the US-Spain group (M = 46.8 ms, SD = 19.1 ms), t(787) = 5.693, p < 0.001. To confirm that the impact of linguistic environment was similar for each group, separate models were conducted for each group. The model structure was parallel to the main model above. Results suggested that linguistic environment did not significantly impact VOT for either the US-Spain group (b = −2.616, t = −1.136) or the Spain-US group (b = 4.799, t = 1.923). |

| 5 | Parallel to the by-group analysis for VOT, mixed effect model was conducted on GAR with linguistic environment and group as fixed effects. Model comparison showed that the inclusion of group did not significantly improve model fit (χ2(2) = 5.143, p = 0.076). As with VOT, results demonstrated that linguistic environment did not significantly impact the GAR for either the US-Spain group (b = 0.13, t = 1.169) or the Spain-US group (b = −0.03, t = −0.572). |

| Component | Scale a | English M (SD) | Spanish M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language History | 0–120 | 104.2 (8.7) | 17.2 (8.4) |

| Language Use | 0–50 | 46.6 (2.8) | 3.3 (2.8) |

| Language Proficiency | 0–24 | 23.8 (0.6) | 14.2 (2.6) |

| Language Attitudes | 0–24 | 23.4 (2.8) | 15.0 (5.4) |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | d | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (English Environment) | 44.45 | 3.37 | 13.175 | 37.70 | 51.19 | ||

| Spanish Environment | 0.22 | 1.85 | 0.119 | −3.47 | 3.91 | 0.03 | [−0.15, 0.22] |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (English Environment) | 58.53 | 13.36 | 4.380 | 31.80 | 85.26 |

| Spanish Environment | 1.41 | 7.37 | 0.191 | −13.33 | 16.14 |

| Proficiency | −0.18 | 0.17 | −1.088 | −0.52 | 0.15 |

| Spanish Environment: Proficiency | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.166 | 0.02 | −0.05 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | d | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (English Environment) | −0.027 | 0.147 | −0.185 | −0.321 | 0.267 | ||

| Spanish Environment | 0.065 | 0.082 | 0.795 | −0.099 | 0.229 | 0.06 | [−0.06, 0.19] |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (English Environment) | −1.013 | 0.608 | −1.666 | −2.229 | 0.203 |

| Spanish Environment | −0.006 | 0.287 | −0.022 | −0.580 | 0.568 |

| Proficiency | 0.012 | 0.008 | 1.667 | −0.003 | 0.027 |

| Spanish Environment: Proficiency | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.259 | −0.006 | 0.008 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olson, D.J. Short-Term Sources of Cross-Linguistic Phonetic Influence: Examining the Role of Linguistic Environment. Languages 2020, 5, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040043

Olson DJ. Short-Term Sources of Cross-Linguistic Phonetic Influence: Examining the Role of Linguistic Environment. Languages. 2020; 5(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlson, Daniel J. 2020. "Short-Term Sources of Cross-Linguistic Phonetic Influence: Examining the Role of Linguistic Environment" Languages 5, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040043

APA StyleOlson, D. J. (2020). Short-Term Sources of Cross-Linguistic Phonetic Influence: Examining the Role of Linguistic Environment. Languages, 5(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040043