A Longitudinal Study in the L2 Acquisition of the French TAM System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The French, English and Spanish TAM Systems

- 1.

- Je ne peux pas y aller avec toi, je dois rendre ce rapport demain.No puedo ir contigo, tengo que entregar este informe mañana.‘I cannot go with you, I have to turn in this report tomorrow’.

- Je voudrais bien y aller avec toi, mais ce n’est pas possible.Me gustaría ir contigo, pero no puedo.‘I would like to go with you, but I can’t’.

- Tu aurais dû me le dire, je t’aurais aidé.Me lo tendrías que haber dicho, te hubiera ayudado.‘You should have told me, I would have helped you’.

- 2.

- Elle a échoué à ses examens parce qu’elle était malade.Suspendió sus exámenes porque estaba enferma.‘She failed her exams because she was sick’.

- Je suis triste qu’elle soit malade.Me apena que esté enferma.‘I’m sad that she is sick’.

- Il est dommage vous n’ayez pas pu venir avec nous.Es una lástima que no pudiera venir con nosotros.‘It’s a pity that you couldn’t come with us’.

- 3.

- Elle pense que c’est-IndPrespossible/*ce soit-SubjPrespossible.‘She thinks it’s possible’

- Elle ne pense pas que c’est-IndPresvrai/ce soit-SubjPresvrai.‘She does not think it’s true’

- Pense-t-elle que c’est intéressant-IndPres/ce soit-SubjPresintéressant?‘Does she think it’s interesting?’

- 4.

- Paul cherche un traducteur qui sait-IndPres/sache-SubjPres/saurait-CondPresl’arabe.‘Paul is looking for a translator who knows Arabic’.

- Lisa aimerait travailler avec des collègues qui la respectent-IndPres- SubjPres/respecteraient-CondPres.‘Lisa would like to work with colleagues who respect her’.

- 5.

- They insist that all the students sign up for a counselor.

- They insist that this student sign up for a counselor

- 6.

- The customer is demanding that the stores return his money.

- The customer demanded that the store return his money

- 7.

- We insist that he be the one to make the call.

- The customer demanded that his money be returned.

- 8.

- We insist that he not make the telephone call.

- *We insist that he do/does make the telephone call.

- 9.

- Estaba caminado sola, no sé por qué.Elle marchait seule, je ne sais pas pourquoi.‘She was walking by herself, I don’t know why’.

- Estoy pensando en este nuevo proyecto.Je suis en train de réfléchir à ce nouveau projet.‘I’m thinking about this new project’.

- Estaba cocinando la cena.Il préparait/était en train de préparer le dîner.‘He was cooking dinner’.

- 10.

- Quand je vivais à Nice, je jouais au tennis en été.Cuando vivía en Nice, jugaba al tenis durante el verano.‘When I lived in Nice, I would play tennis in the summer’.

- 11.

- Lo han vendido.Ils l’ont vendu.‘They have sold it’.

- Han empezado a construir la casa nueva.Ils ont commencé à construire la nouvelle maison.‘They have started to build the new house’.

- Hace much tiempo que lo conozco.Je le connais depuis longtemps.‘I have known him for a long time’.

- 12.

- Sophie est sortie-pc avec ses amis hier soir.Sophie went out with her friends last night.

- Sophie sort-IndPres avec ses amis de temps en temps.Sophie has been going out with her friends once in a while.

3. Literature Review of French TAM Studies

4. Learnability Issues and Research Questions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Participants

5.2. Classroom Setting and Materials

5.3. Procedure and Tasks

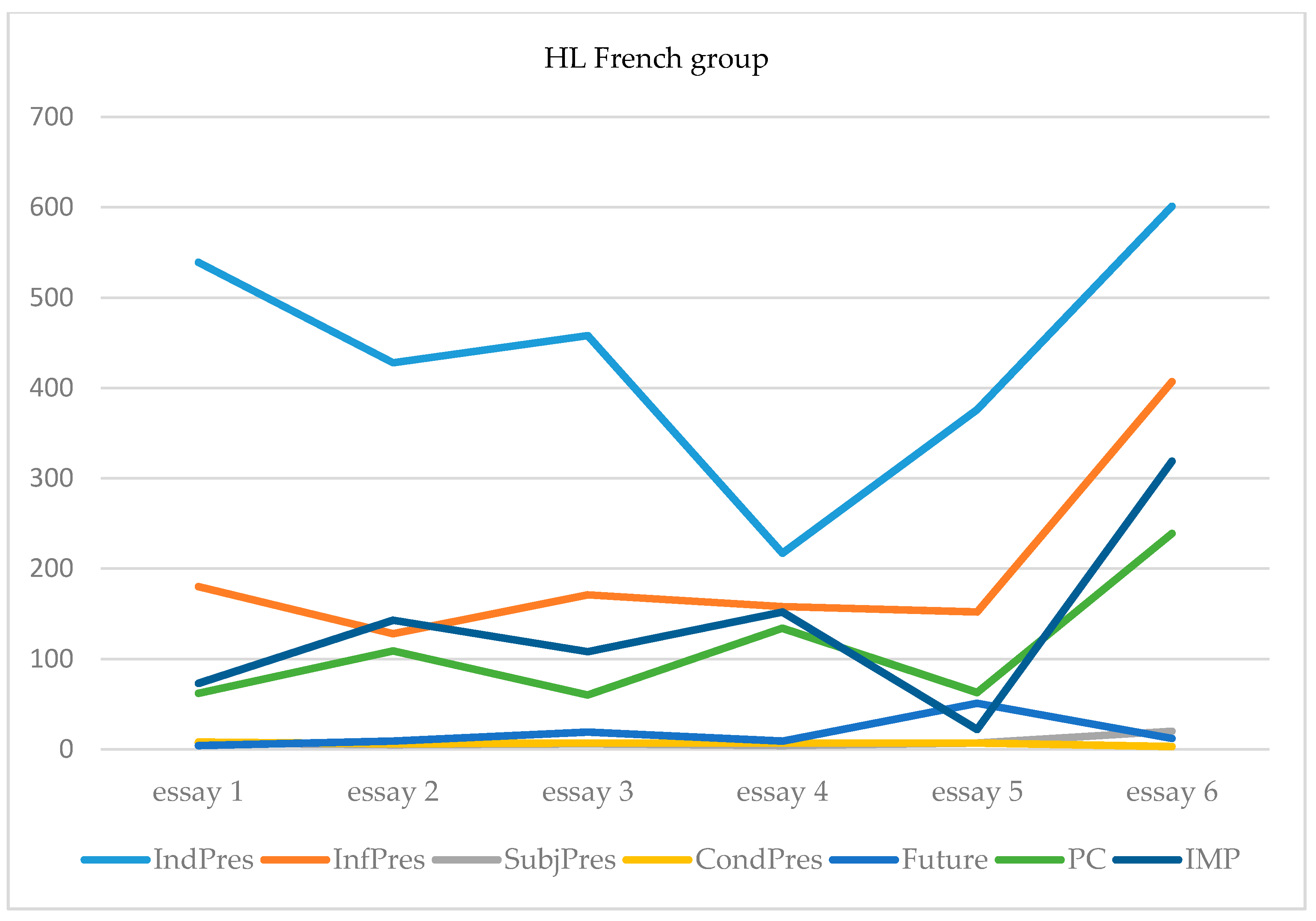

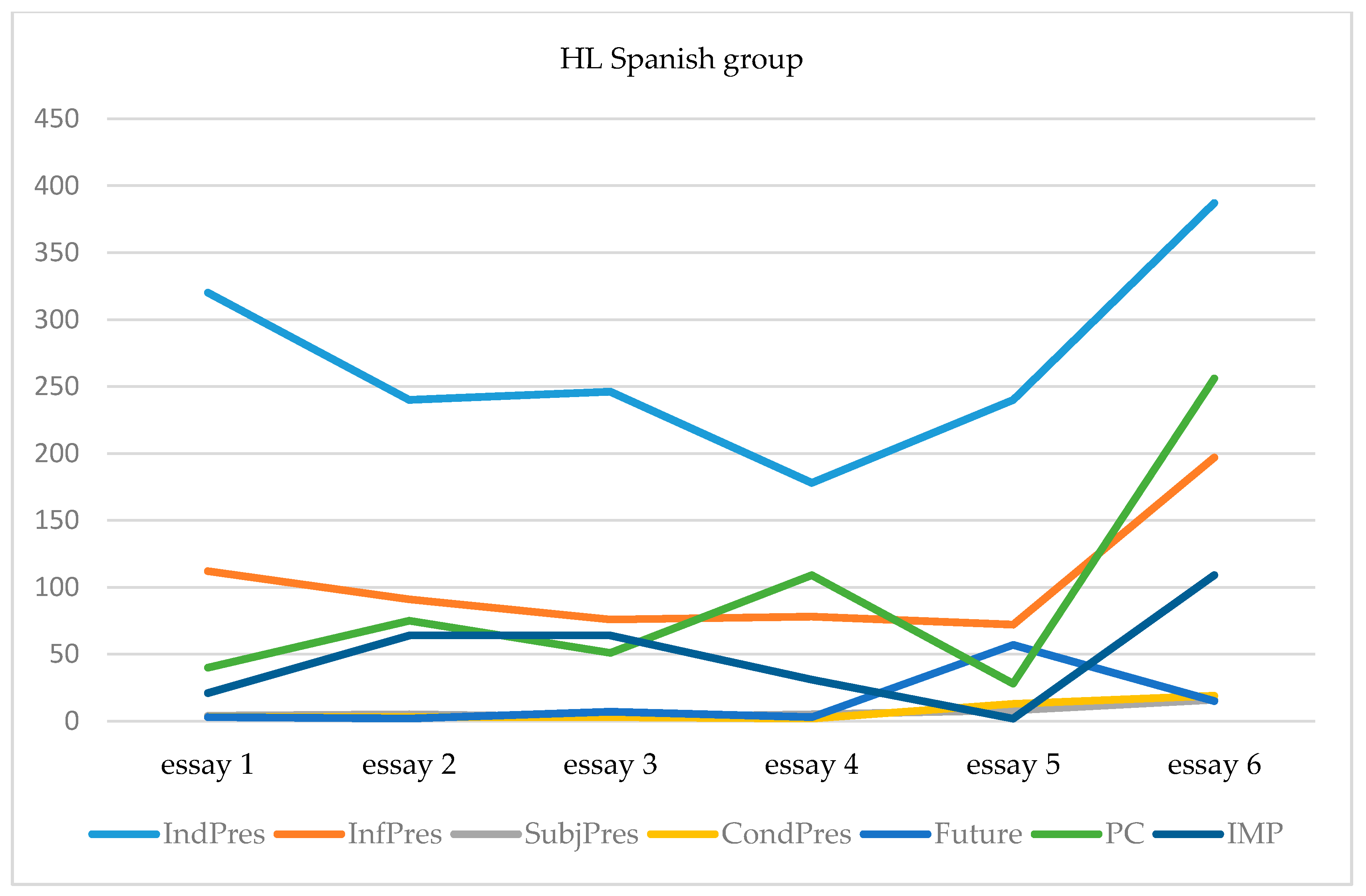

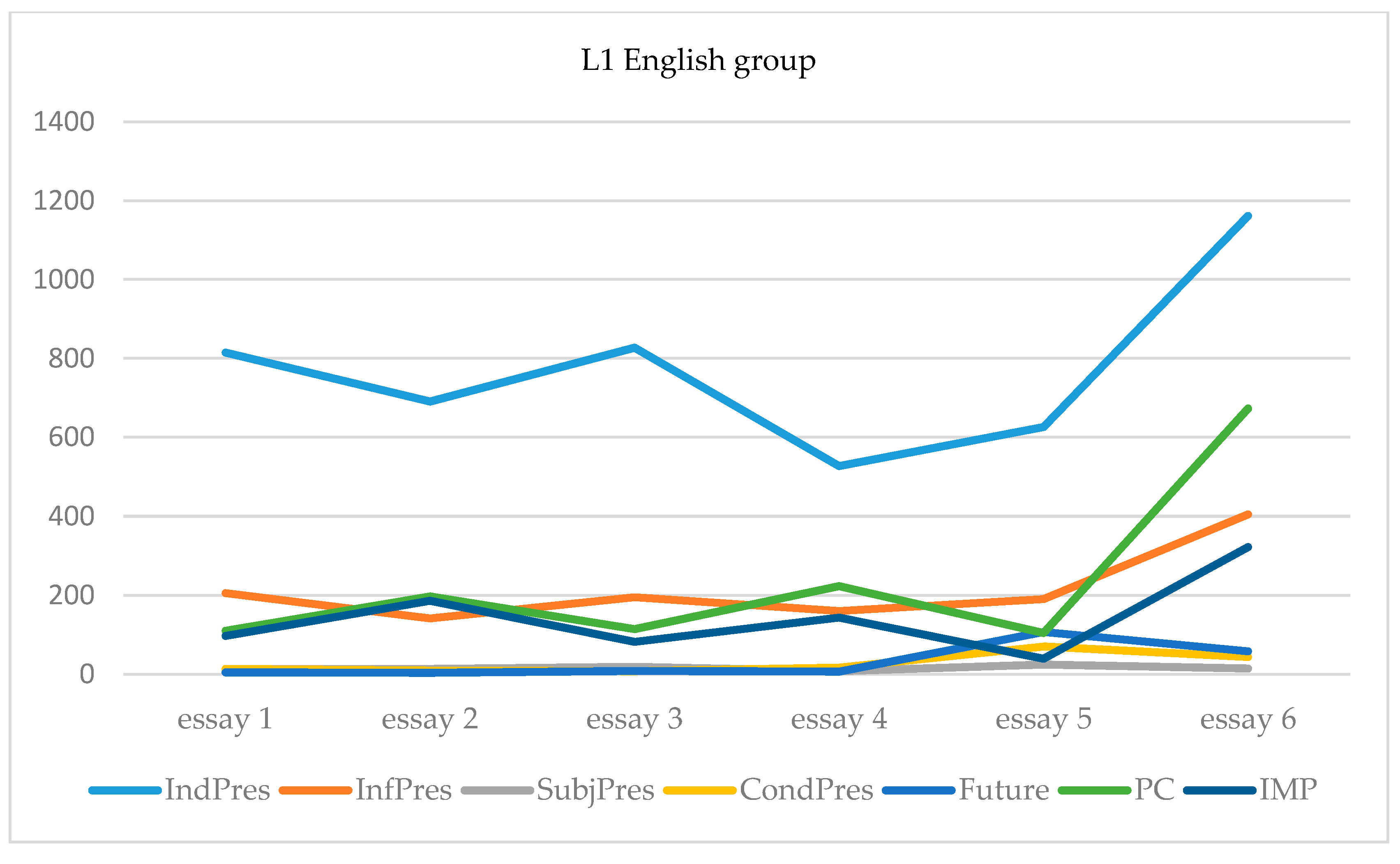

6. Results

7. Discussion

- 13.

- Une âme sœur est-IndPresquelqu’un qu’on aime-IndPres, et qui nous aide-IndPresàdevenir- InfPresla meilleure personne qu’on puisse- SubjPresêtre-InfPres.A soulmate is someone we love and who helps us to become the best person we can be’.

- 14.

- Donc la mort de Renée n’est-IndPrespas inutile parce qu’elle a- IndPresun but, la mort deRenée permet- IndPresque Paloma vive-SubjPres.‘So Renée’s death is not useless because it has a goal, Renée’s death allows Paloma to live’.

- 15.

- Tandis que tous les policiers déshumanisent-IndPresles juifs, un policier écoute- IndPresSarah et la laisse-IndPress’échapper-InfPresdu camp.‘While all the policemen dehumanize Jews, one policeman listens to Sarah and lets herflee the camp’.

- 16.

- Les concierges qui ont- IndPresdu courage et de la sympathie pour les familles juives etceux qui ont- IndPrespeur des policiers et qui sont-indpres coupables de dénoncer-InfPresles familles.‘Building managers who are brave and feel for the Jewish families, and those who areafraid of the policemen and who are capable of denouncing families’.

- 17.

- Quand elle est arrivée, elle a demandé de voir M. Lamarc, elle a dû attendre seulement quelquesminutes pour lui *apparaître-Infet *mener-Infelle à son bureau (essay 5, L1 English group)‘When she arrived, she asked to see Mr. Lamarc, she only had to wait a few minutes forhim to appear and show her to his office’

- 18.

- Si Julia n’avait pas trouvé-pqple secret de la famille de son mari, sa vie n’aurait sansdoute pas été touchée-CondPast.‘If Julia had not found her husband’s family, it would probably not have changed her life’.

- 19.

- Parce que leur famille avait déménagé-pqpdans l’appartement de Sarah il y a plusieursannées, Julia avait trouvé-pqple lien vers les deux familles.‘Because her family had moved into Sarah’s apartment several years ago, Julia had foundthe connection between the two families’.

- 20.

- Peut-être que si l’Holocauste n’a pas eu lieu-*pc/pqp, Sarah aurait vécu-CondPastune longuevie innocente.‘Maybe, if the Holocaust had not taken place, Sarah would have lived a long, innocentlife’.

- 21.

- Dans cette partie, on apprendra-futune chose secrète de chaque personnage et Jeannotrévèlera- futson vrai nom.‘In this part, we will learn a secret about each character and Jeannot will reveal his realname’.

- 22.

- Dans mon film, je vais changer-FutProle rôle de Marcel Langer un peu, et l’acteur quipeut-IndPrescompléter-InfPresce personnage est-IndPresGerard Butler.‘In my movie, I’m going to change the role of Marcel Langer a bit, and the actor who cancomplete this character is Gerard Butler’.

- 23.

- Par contre, le petit frère de Sarah n’avait pas été trouvé-pqp, car il s’était caché-pqpet Sarah nousracontera-futles malheurs et sentiments qu’elle a ressentis-pcdurant plus d’un mois.‘On the other hand, Sarah’s little brother was not found because he hid and Sarah will tellus about the misfortunes and feelings she experienced for over a month’.

- 24.

- Quand sa famille a été soudainement arrêtée-pc pour la déportation, Sarah a verrouillé-pcson petitfrère Michel dans le placard de sorte qu’il serait-*CondPressûr et caché jusqu’à ce qu’elle puisse-SubjPresretourner-InfPresle sauver-InfPres.‘When her family was suddenly arrested to be deported, Sarah locked up her little brotherMichel in the closet so that he would be safe and hidden until she could come back andsave him’.

- 25.

- J’ai bien aimé-pcle livre, mais pour l’adapter-InfPrespour le cinéma il faut-IndPresque jechangerais-*CondPres/SubjPresplusieurs parties de l’histoire.‘I liked the book, but to turn it into a movie, I need to change several parts of the story’.

- 26.

- Renée est-IndPresune veuve et concierge qui a travaillé-*pc/IndPresdans l’appartement depuis27 ans, mais elle cache-IndPresqu’elle aime- IndPresla philosophie, Ia litterature, la gastronomieet la musique classique parce qu’elle croit- IndPresque les residents ne voudraient-CondPrespascela.‘Renée is a widow and building manager who has been working for 27 years, but she hides that she likes philosophy, literature, gastronomy, and classical music because shethinks that the residents would not like it’.

- 27.

- François avait toujours imaginé-pqpque ses parents sportifs se sont rencontrés-*pc/pqpau bordde la piscine ou au stade et qu’il avait-imp un frère, jusqu’un jour il a appris-pcla vérité.‘François had always imagined that his athletic parents had met by the pool or thestadium and that he had a brother until he learned the truth one day’.

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Essays’ Topics [Translated from French]

- Essay 1. Oscar et la dame rose

- Essay 2. Un secret

- Essay 3. L’élégance de l’hérisson

- Essay 4. Elle s’appelait Sarah

- Essay 5. Adaptation of Les enfants de la liberté

- Essay 6. Choose one of the following movies: Il y a longtemps que je t’aime (Claudel 2008), Les choristes (Barratier 2004), La vie rêvée des anges (Zonca 1998). Take notes as you watch it, then write a 4–6 page short story.

References

- Ahern, Aoife, José Amenós-Pons, and Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes. 2016. Mood interpretation in Spanish: Towards an encompassing view of L1 and L2 interface variability. In Acquisition of Romance Languages: Old Acquisition Challenges and New Explanations from a Generative Perspective. Edited by Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes, Pilar Larrañaga and Maria Juan-Garau. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 141–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoun, Dalila. 2005. The acquisition of tense and aspect in L2 French from a Universal Grammar perspective. In Tense and Aspect in Romance Languages: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives. Edited by Dalila Ayoun and Rafael Salaberry. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 79–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoun, Dalila. 2013. The Second Language Acquisition of French Tense, Aspect, Mood and Modality. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoun, Dalila. 2015. There is no time like the present: A longitudinal case study in L2 French acquisition. In The Acquisition of the Present. Edited by Dalila Ayoun. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoun, Dalila, and Jason Rothman. 2013. Generative approaches to the L2 acquisition of temporal-aspectual-mood (TAM) systems. In Research Design and Methodology in Studies on Second Language Tense and Aspect. Edited by Rafael Salaberry and Llorenc Comajoan. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 119–56. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth, Carl. 2005. From empirical results to the teaching of aspectual distinctions. In Tense and Aspect in Romance Languages. Edited by Dalila Ayoun and Rafael Salaberry. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 211–52. [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovo, Claudia, Joyce Bruhn de Garavito, and Philippe Prévost. 2015. Mood selection in relative clauses. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 37: 33–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgovono, Claudia, and Philippe Prévost. 2003. Knowledge of polarity subjunctive in L2 Spanish. Paper presented at 27th Boston University Conference on Language Development, Somerville, MA, USA, November 1–3; pp. 150–61. [Google Scholar]

- Celce-Murcia, Marianne, and Diane Larsen-Freeman. 1999. The Grammar Book. An ESL/EFL Teacher’s Course, 2nd ed. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo, Lourdes, Rosa Manchón, and Florentina Nicolás-Conesa. 2019. What do learners notice when processing written corrective feedback? In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Research in Classroom Learning: Processing and Processes. New York: Routledge, pp. 173–87. [Google Scholar]

- Collentine, Joseph. 2003. The development of subjunctive and complex-syntactic abilities among FL Spanish learners. In Studies in Spanish Second Language Acquisition: The State of the Science. Edited by Barbara Lafford and Rafael Salaberry. Washington: Georgetown University Press, pp. 74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Collentine, Joseph. 2010. The acquisition and teaching of the Spanish subjunctive: An update on current findings. Hispania 93: 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: CUP. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod, and Younghee Sheen. 2006. Reexamining the role of recasts in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 28: 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Claudia. 2008. Reexamining the role of explicit information in processing instruction. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 30: 277–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, Susan. 2013. Input, Interaction and the Second Language Learner. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Goad, Heather, Lydia White, and Jeffrey Steele. 2003. Missing inflection in L2 acquisition: Missing syntax or L1-constrained prosodic representations? Canadian Journal of Linguistics 48: 243–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Roger, and Cecilia Yuet-hung Chan. 1997. Partial availability of Universal Grammar in second language acquisition: The failed formal features hypothesis. Second Language Research 13: 187–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roger, and Sarah Liszka. 2003. Locating the source of defective past tense marking in advanced L2 English speakers. In The Interface between Syntax and Lexicon in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Roeland van Hout, Aafke Hulk, Folkert Kuiken and Richard Towell. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar, Belma, and Bonnie Schwartz. 1997. Are there optional infinitives in child L2 acquisition? In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Elizabeth Hughes, Mary Hughes and Annabel. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 257–68. [Google Scholar]

- Herschensohn, Julia. 2001. Missing inflection in second language French: Accidental infinitives and other verbal deficits. Second Language Research 17: 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschensohn, Julia, and Debbie Arteaga. 2009. Tense and verb raising in advanced L2 French. Journal of French Language Studies 19: 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Martin. 2005. The emergence and use of the plus-que-parfait in advanced French interlanguage. In Focus on French as a Foreign Language. Edited by Jean-Marc Dewaele. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Martin. 2008. Morpho-syntactic development in the expression of modality: The subjunctive in French L2 acquisition. Revue Canadienne de Linguistique Appliquée 11: 171–91. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Martin. 2009. Expressing irrealis in L2 French: A preliminary study of the conditional and tense-concordancing in L2 acquisition. Issues in Applied Linguistics 17: 113–35. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Martin. 2012. From tense and aspect to modality: The acquisition of future, conditional and subjunctive morphology in L2 French. A preliminary study. Cahiers Chronos 24: 201–23. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Martin. 2015. At the interface between sociolinguistic and grammatical development: The expression of futurity in L2 French. A preliminary study. Arborescence 5: 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Izquierdo, Jesús. 2009. L’aspect lexical et le développement du passé composé et de l’imparfait en français L2: Une étude quantitative auprès d’apprenants hispanophones. The Canadian Modern Language Review 65: 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, Jesús. 2014. Multimedia instruction in foreign language classrooms: Effects on the acquisition of the French perfective and imperfective distinction. The Canadian Modern Language Review 70: 188–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, Jesús, and Laura Collins. 2008. The facilitative role of L1 influence in tense-aspect marking: A comparison of Hispanophone and Anglophone learners of French. The Modern Language Journal 92: 350–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, Jesús, and Maria Kihlstedt. 2019. L2 imperfective functions with verb types in written narratives: A cross-sectional study with instructed Hispanophone learners of French. The Modern Language Journal 103: 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Francis. 1986. Semantics of the English Subjunctive. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Larry D., and Margarita Suñer. 1980. The meaning of the progressive in Spanish and Portuguese. Bilingual Review 7: 222–39. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Wolfgang, and Clive Perdue. 1997. The Basic Variety (or couldn’t natural languages be much simpler?). Second Language Research 13: 301–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeau, Emmanuelle. 2007. Pas si simple! La place du PS dans l’interlangue d’apprenants. Cahiers Chronos 19: 177–97. [Google Scholar]

- Labeau, Emmanuelle. 2009. Le PS: Cher disparu de la rubrique nécrologique? Journal of French Language Studies 19: 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2000. Mapping features to forms in second language acquisition. In Second Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory. Edited by John Archibald. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 102–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2008. Feature assembly in second language acquisition. In The Role of Formal Features in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Juana Liceras, Helmut Zobl and Helen Goodluck. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 106–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2009. Some thoughts on the contrastive analysis of features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research 25: 173–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lealess, Allison. 2005. En Français, il Faut Qu’on Parle Bien: Assessing Native-Like Proficiency in L2 French. Master’s thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Shaofeng. 2010. The effectiveness of corrective feedback in SLA: A meta-analysis. Language Learning 60: 309–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, Kevin, and Rosamond Mitchell. 2015. Subjunctive use and development in L2 French: A longitudinal study. Language, Interaction & Acquisition 6: 42–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mourelatos, Alexander. 1978. Events, processes, and states. Language and Philosophy 2: 415–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, Florence. 2005. The emergence of morpho-syntactic structure in French L2. In Focus on French as a Foreign Language: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Edited by Jean-Marc Dewaele. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 88–113. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, John, and Lourdes Ortega. 2000. Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning 50: 417–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, John, and Lourdes Ortega. 2015. Implicit and explicit instruction in L2 learning. Norris & Ortega (2000) revisited and updated. In Implicit and Explicit Learning of Languages. Edited by Patrick Rebuschat. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 443–82. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Frank R. 2001. Mood and Modality. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Frank R. 2003. Modality in English: Theoretical, descriptive and typological issues. In Modality in Modern English. Edited by Roberta Facchinetti, Manfred Krug and Frank R. Palmer. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Piske, Thorsten, and Martha Young-Scholten. 2009. Input Matters in SLA. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Philippe. 2003. On the nature of root infinitives in adult L2 French. In Romance Linguistics: Theory and Acquisition. Selected Papers from the 32nd Linguistic Symposium on Romance Languages (LSRL). Edited by Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux and Yves Roberge. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 367–84. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Philippe, and Lydia White. 2000. Missing surface inflection or impairment in second language acquisition? Evidence from tense and agreement. Second Language Research 16: 103–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, Tanya. 2006. Interface Strategies. Optimal and Costly Computations. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salaberry, Rafael, and Dalila Ayoun. 2005. The development of L2 tense/aspect in the Romance languages. In Tense and Aspect in Romance Languages: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives. Edited by Dalila Ayoun and Rafael Salaberry. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Carlota. 1991. The Parameter of Aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Carlota. 1997. The Parameter of Aspect, 2nd ed. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2000. Syntactic optionality in non-native grammars. Second Language Research 16: 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2003. Ultimate L2 attainment. In Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Michael Long and Cathy Doughty. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 130–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2005. Selective optionality in language development. In Syntax and variation. Reconciling the Biological and the Social. Edited by Leonie Cornips and Karen P. Corrigan. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2011. Pinning down the concept of interface in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Francesca Filiaci. 2006. Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research 22: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Ludovica Serratrice. 2009. Internal and external interfaces in bilingual development: Beyond structural overlap. Bilingualism 73: 89–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, Nina. 1997. Form-focused instruction and second language acquisition: A review of classroom and laboratory research. Language Teaching 29: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi, and Antonella Sorace. 2006. Differentiating interfaces: L2 performance in syntax-semantics and syntax-discourse phenomena. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, BUCLD 30. Edited by David Bamman, Tatiana Magnitskaia and Colleen Zaller. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 653–64. [Google Scholar]

- van Osch, Brechje, Aafke Hulk, Petra Sleeman, and Suzanne Aalberse. 2017. Knowledge of mood in internal and external interface contexts in Spanish heritage speakers in the Netherlands. In Multidisciplinary Approaches to Bilingualism in the Hispanic and Lusophone World. Edited by Kate Bellamy, Michael W. Child, Paz González, Antje Muntendam and M. Carmen Parafit Couto. Amterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Vendler, Zeno. 1967. Verbs and times. In Linguistics and Philosophy. Edited by Zeno Vendler. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 97–121, reprinted in Philosophical Review 1957, 66, 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Yingli, and Roy Lyster. 2010. Effects of form-focused practice and feedback on Chinese EFF learners’ acquisition of regular and irregular past tense forms. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 32: 235–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | As a marked mood necessary to express various modalities (i.e., the speaker’s attitude towards the utterance), the subjunctive is considered as a benchmark in the L2 acquisition of French. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | Izquierdo and Kihlstedt (2019) focuses even more narrowly on imparfait in written narratives by Hispanophone learners (n = 94). |

| 4 | Recasts are defined as a corrective reformulation of an erroneous utterance during a natural interaction, they are thus a form of implicit negative feedback e.g., (Spada 1997). |

| 5 | Un secret, novel by Philippe Grimbert (2007) and movie by Claude Miller (2007); Elle s’appelait Sarah, novel by Tatiana de Rosnay (2010) and movie by Gilles Paquet-Brenner (2010); Les enfants de la liberté, novel by Marc Lévy (2008), no film adaptation; Oscar et la dame en rose, novel and film by Eric Emmanuel Schmitt (2009); L’élégance du hérisson, novel by Muriel Barbéry (2009) and film by Mona Achache (2009). |

| 6 | The abbreviations used for the forms are as follows: IndPres (indicative present), PC (passé composé), IMP (imparfait), InfPres (infinitive present), PartPres (present participle), CondPres (conditional present), SubjPres (subjunctive present), PQP (plus-que-parfait), FutPro (future proche, near future), InfPast (infinitive past), CondPast (conditional past), PresProg (present progressive), SubjPast (past subjunctive), PS (passé simple), IMPProg (imparfait progressive), PastPart (past participle), FutProg (future progressive). |

| 7 | The forms were chosen because they were either frequent (i.e., indicative present, infinitive present, passé composé, imparfait, future) or provided a temporality and/or mood contrast (i.e., subjunctive present, plus-que-parfait, present participle, conditional present). |

| 8 | A General Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) was used to test for significant differences in mean error percentage for the fixed effects of groups, essays, and their interaction. Subject intercept was used as a random effect. A separate GLMM was conducted for each error type. |

| 9 | The appropriate verbal forms would be: Quand elle est arrivée, elle a demandé de voir M. Lamarc, elle a dû attendre seulement quelques minutes pour qu’il apparaisse-SubjPres et la mène-SubjPres à son bureau. |

| 10 | The Sonoran Mexican Spanish of our participants does not differ from European Spanish in its use of past aspectual distinctions or indicative-subjunctive alternation (Carvalho 2018, personal communication). |

| 11 | The 160 subjunctive tokens were used with the following triggers: de sorte que (n = 1), afin que (n = 2), après que (n = 1)—although it is followed by the indicative in prescriptive grammars, French native speakers use it with the subjunctive—bien que (n = 26), avant que (n = 6), pour que (n = 14), jusqu’à ce que (n = 17), que (n = 20), falloir (n = 6), aimer (n = 3), souhaiter (n = 1), vouloir (n = 34), ne pas croire (n = 1), le fait que (n = 2), noun/adjective que (n = 23), superlative (n = 3). |

| L1 English n = 9 | Heritage French n = 4 | Heritage Spanish n = 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| gender | F (n = 7), M (n = 2) | F (n = 4) | F (n = 2), M (n = 1) |

| age | 21 (20–22) | 22 (20–24) | 21.7 (20–23) |

| college status | undergraduate | ||

| college major | French (n = 5) | French (n = 2) | French (n = 3) |

| age of onset | 15–17 | 0 | 15–17 |

| L2 setting | instructed | home/instructed | instructed |

| Francophone stay | no (n = 6) yes (n = 4) 6 weeks to a year | yes (n = 4) 4–12 years | no (n = 3) |

| motivation | very to extremely motivated | ||

| L1 English (n = 9) | Essay 1 | Essay 2 | Essay 3 | Essay 4 | Essay 5 | Essay 6 | Total Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| words | 8681 | 8704 | 8346 | 8859 | 9326 | 16,126 | 60,042 |

| verbal tokens | 1289 | 1274 | 1277 | 1126 | 1193 | 2800 | 8959 |

| IndPres | 815 | 691 | 827 | 527 | 626 | 1161 | 4647 |

| IndPres % | 63.22% | 54.24% | 64.76% | 46.8% | 52.47% | 41.46 | 52% |

| Errors | 36–4.41% | 9–1.30% | 9–1.08% | 16–3.03% | 8–1.27% | 44–3.78% | 122–2.65% |

| PC | 110 | 197 | 114 | 223 | 104 | 673 | 1421 |

| PC % | 8.53% | 15.46% | 8.92% | 19.8% | 8.71% | 24.03% | 15.9% |

| Errors | 21–19.09% | 18–9.13% | 7–6.14% | 10–4.48% | 3–2.88% | 46–6.83% | 105–7.4% |

| IMP | 97 | 186 | 82 | 143 | 39 | 322 | 869 |

| IMP % | 7.52% | 14.6% | 6.42% | 12.7% | 3.26% | 11.5% | 9.7% |

| Errors | 8–8.24% | 9–4.83% | 3–3.65% | 10–6.99% | 1–2.56% | 14–4.34% | 45–5.2% |

| InfPres | 205 | 141 | 195 | 160 | 190 | 405 | 1296 |

| InfPres % | 15.9% | 11.06% | 15.37% | 14.21% | 15.92% | 14.46% | 14.5% |

| Errors | 27–13.17% | 9–6.38% | 11–5.64% | 14–8.75% | 11 -5.78% | 23–5.67% | 95–7.3% |

| PartPres | 16 | 14 | 11 | 15 | 17 | 25 | 98 |

| PartPres % | 1.24% | 1.18% | 0.86% | 1.33% | 1.42% | 0.003% | 1.09% |

| Errors | 2–12.5% | 2–14.28% | 0–0% | 4–26.67% | 1–5.88% | 0–0% | 9–9.2% |

| CondPres | 13 | 9 | 7 | 16 | 70 | 43 | 158 |

| CondPres % | 1.01% | 0.71% | 0.55% | 1.42% | 5.86% | 1.53% | 1.76% |

| Errors | 3–23.1% | 5–55.6% | 0–0% | 10–62.5% | 5–7.14% | 8–18.6% | 31–19.6% |

| SubjPres | 12 | 13 | 18 | 7 | 24 | 14 | 88 |

| SubjPres % | 0.93% | 1.02% | 1.41% | 0.62% | 2.0% | 0.5% | 0.98% |

| Errors | 3–25% | 1–7.69% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 14–100% | 18–20.4% |

| PQP | 4 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 0 | 49 | 74 |

| PQP % | 0.31% | 0.23% | 0.23% | 1.33% | 0.0% | 1.75% | 0.82% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 6–12.2% | 6–8.1% |

| Future | 4 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 107 | 58 | 186 |

| Future % | 0.31% | 0.23% | 0.63% | 0.53% | 8.96% | 2.07% | 2.07% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–12.5% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–0.53% |

| FutPro | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 26 |

| FutPro % | 0.54% | 0.23% | 0.078% | 0.089% | 0.25% | 0.39% | 0.29% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–100% | 0–0% | 1–9.1% | 2–7.7% |

| InfPast | 3 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 35 |

| InfPast % | 0.23% | 0.15% | 0.31% | 0.62% | 0.75% | 0.35% | 0.39% |

| Errors | 1–33.3% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–11.1% | 0–0% | 2–5.7% |

| CondPast | 1 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 21 |

| CondPast % | 0.07% | 0.71% | 0.31% | 0.26% | 0.0% | 0.14% | 0.23% |

| PresProg | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| PresProg % | 0.07% | 0.078% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.084% | 0.11% | 0.067% |

| SubjPast | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 10 |

| SubjPast % | 0.07% | 0.078% | 0.0% | 0.18% | 0.0% | 0.21% | 0.11% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–16.7% | 1–10% |

| PS | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| PS % | 0.0% | 0.078% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.11% | 0.044% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–66.7% | 2–50% |

| IMPProg | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| IMPProg % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.15% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.022% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–50% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–50% |

| PastPart | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| PastPart % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.078% | 0.089% | 0.16% | 0.03% | 0.056% |

| FutProg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| FutProg % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.084% | 0.0% | 0.011% |

| Imperative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| Imperative % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.43% | 0.133% |

| HL French (n = 4) | Essay 1 | Essay 2 | Essay 3 | Essay 4 | Essay 5 | Essay 6 | Total Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| words | 4872 | 5043 | 5532 | 5296 | 5071 | 9617 | 35,431 |

| verbal token | 891 | 850 | 850 | 738 | 704 | 1703 | 5736 |

| IndPres | 539 | 428 | 458 | 217 | 376 | 601 | 2619 |

| IndPres % | 60.5% | 50.3% | 53.9% | 29.4% | 53.4% | 35.3% | 45.6% |

| Errors | 4–0.74% | 6–1.4% | 2–0.43% | 1–0.46% | 2–0.53% | 25–4.2% | 40–1.5% |

| PC | 62 | 109 | 60 | 134 | 63 | 239 | 667 |

| PC % | 6.9% | 12.8% | 7.1% | 18.2% | 8.95% | 14.0% | 11.6% |

| Errors | 2–3.2% | 5–4.6% | 3–5% | 5–3.73% | 2–3.2% | 15–6.3% | 32–4.8% |

| IMP | 73 | 143 | 108 | 152 | 22 | 319 | 817 |

| IMP % | 8.2% | 16.8% | 12.7% | 20.6% | 3.12% | 18.7% | 14.2% |

| Errors | 1–1.4% | 6–4.2% | 7–6.5% | 17–11.2% | 2–9.1% | 11–3.4% | 44–5.4% |

| InfPres | 180 | 128 | 171 | 158 | 152 | 407 | 1196 |

| InfPres % | 20.2% | 15.1% | 20.1% | 21.4% | 21.59% | 23.9% | 20.85% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–1.2% | 0–0% | 7–4.6% | 1–0.24% | 10–0.83% |

| PartPres | 4 | 12 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 18 | 68 |

| PartPres % | 0.44% | 1.41% | 1.64% | 1.35% | 1.42% | 1.1% | 1.18% |

| Errors | 1–25% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1 | 0–0% | 2–2.9% |

| CondPres | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 38 |

| CondPres % | 0.89% | 0.71% | 0.82% | 0.95% | 0.99% | 0.01% | 0.66% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–28.6% | 3–42.8% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 5–13.2% |

| SubjPres | 7 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 20 | 49 |

| SubjPres % | 0.78% | 0.58% | 0.71% | 0.54% | 0.99% | 1.17% | 0.08% |

| PQP | 6 | 5 | 1 | 25 | 5 | 19 | 61 |

| PQP % | 0.67% | 0.58% | 0.11% | 3.38% | 0.71% | 1.1% | 1.06% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–8% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–3.3% |

| Future | 4 | 9 | 19 | 9 | 51 | 12 | 104 |

| Future % | 0.44% | 1.05% | 2.22% | 1.22% | 7.24% | 0.07% | 1.81% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 1–11.1% | 0–0% | 1–11.1% | 0–0% | 2–16.7% | 4–3.8% |

| FutPro | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 17 |

| FutPro % | 0.22% | 0.0% | 0.11% | 0.27% | 0.56% | 0.04% | 0.29% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–50% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–5.9% |

| InfPast | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| InfPast % | 0.0% | 0.11% | 0.35% | 0.27% | 0.28% | 0.01% | 0.17% |

| CondPast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 8 |

| CondPast % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.41% | 0.0% | 0.02% | 0.13% |

| SubjPast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| SubjPast % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.27% | 0.0% | 0.005% | 0.05% |

| PS | 4 | 4 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 27 | 50 |

| PS % | 0.44% | 0.47% | 0.11% | 1.49% | 0.42% | 1.58% | 0.87% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–9.1% | 0–0% | 1–3.7% | 2–4% |

| PastPart | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 10 |

| PastPart % | 0.11% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.27% | 0.14% | 0.03% | 0.17% |

| Errors | 1–100% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–100% | 1–100% | 6–100% | 10–100% |

| Imperative | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 18 |

| Imp. % | 0.11% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.14% | 0.09% | 0.32% |

| ImpProg | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ImpProg % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.11% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.017% |

| HL Spanish (n = 3) | Essay 1 | Essay 2 | Essay 3 | Essay 4 | Essay 5 | Essay 6 | Total/Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | 2849 | 3230 | 2946 | 3052 | 2815 | 5300 | 20,192 |

| word average | 949.67 | 1076.67 | 982 | 1017.33 | 938.33 | 1766.67 | 6730.67 |

| verbal token | 521 | 496 | 460 | 428 | 431 | 1041 | 3377 |

| IndPres | 320 | 240 | 246 | 178 | 240 | 387 | 1611 |

| IndPres % | 61.4% | 48.38% | 53.48% | 41.59% | 55.68% | 37.17% | 47.7% |

| Errors | 10–3.1% | 7–2.9% | 2–.81% | 5–2.8% | 4–1.7% | 12–3.1% | 40–2.5% |

| PC | 40 | 75 | 51 | 109 | 28 | 256 | 559 |

| PC % | 7.78% | 15.12% | 11.16% | 25.46% | 6.49% | 24.61% | 16.6% |

| Errors | 5–12.5% | 0–0% | 2–3.9% | 5–4.6% | 1–3.6% | 13–5.1% | 26–4.6% |

| IMP | 21 | 64 | 64 | 31 | 2 | 109 | 291 |

| IMP % | 4.03% | 12.9% | 13.91% | 7.24% | 0.46% | 10.47% | 8.62% |

| Errors | 1–4.76% | 4–6.25% | 19–29.7% | 3–9.7% | 0–0% | 5–4.6% | 32- 10.9% |

| InfPres | 112 | 91 | 76 | 78 | 72 | 197 | 626 |

| InfPres % | 21.5% | 18.34% | 16.52% | 16.22% | 16.71% | 3.58% | 18.53% |

| Errors | 8–7.1% | 9–9.9% | 4–5.3% | 3–3.8% | 0–0% | 2–1.0% | 26–4.2% |

| PartPres | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 23 |

| PartPres % | 0.57% | .60% | 0.65% | 1.16% | 0.69% | 0.57% | 0.68% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–33.3 | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 1–4.3% |

| CondPres | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 19 | 43 |

| CondPres % | 0.57% | .60% | 0.65% | 0.46% | 3.02% | 1.82% | 1.27% |

| Errors | 0–0% | 1–33.3% | 2–66.7% | 1–50% | 0–0% | 3–15.8% | 7–16.3% |

| SubjPres | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 16 | 41 |

| SubjPres % | 0.76% | 1.0% | 0.65% | 1.16% | 1.86% | 1.53% | 1.21% |

| Errors | 1–25% | 1–20% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–12.5 | 4–9.7% |

| PQP | 2 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 0–0% | 12 | 32 |

| PQP % | 0.38% | 1.41% | 0.65% | 1.86 | 0.0% | 1.15% | 0.94% |

| Future | 3 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 57 | 15 | 87 |

| Future % | 0.57% | 0.40% | 1.52% | 0.7% | 13.22% | 1.44% | 2.57% |

| Errors | 2–66.7% | 1–50% | 0–0% | 1–66.7% | 0–0% | 2–13.3% | 6–6.9% |

| FutPro | 9 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 25 |

| FutPro % | 1.72% | 0.40% | 0.21% | 0.46% | 0.69% | 0.77% | 0.74% |

| Errors | 2 | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 0–0% | 2–8.0% |

| InfPast | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 20 |

| InfPast % | 0.57% | 0.40% | 0.0% | 1.16% | 0.69% | 0.67% | 0.59% |

| CondPast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| CondPast % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.23% | 0.0% | 0.29% | 0.12% |

| PresProg | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| PresProg % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.21% | 0.0% | 0.23% | 0.0% | 0.06% |

| SubjPast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| SubjPast % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.09 | 0.03% |

| Imperative | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Imperative % | 0.19% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.23% | 0.09 | 0.89% |

| Past participle | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Past participle % | 0.0% | 0.40% | 0.0% | 0.23% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.89% |

| InfPresProg | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| InfPresProg % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.43% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.06% |

| ImpProg | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| ImpProg % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.29% | 0.89% |

| RecentPast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| RecentPast % | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.09 | 0.03% |

| L1 English | HL French | HL Spanish | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erroneous Tokens | Percentage | Erroneous Tokens | Percentage | Erroneous Tokens | Percentage | |

| IndPres | 122 | 2.65% | 40 | 1.5% | 40 | 2.5% |

| PC | 105 | 7.4% | 32 | 4.8% | 26 | 4.6% |

| IMP | 45 | 5.2% | 44 | 5.4% | 32 | 10.9% |

| InfPres | 95 | 7.3% | 10 | 0.83% | 26 | 4.2% |

| PartPres | 9 | 9.2% | 68 | 1.18% | 1 | 4.3% |

| CondPres | 31 | 19.6% | 5 | 13.2% | 7 | 16.3% |

| SubjPres | 18 | 20.4% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 9.7% |

| PQP | 6 | 8.1% | 2 | 3.3% | 0 | 0% |

| Future | 1 | 0.53% | 4 | 3.8% | 6 | 6.9% |

| PastPart | 5 | 0.56% | 10 | 100% | 0 | 0% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayoun, D. A Longitudinal Study in the L2 Acquisition of the French TAM System. Languages 2020, 5, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040042

Ayoun D. A Longitudinal Study in the L2 Acquisition of the French TAM System. Languages. 2020; 5(4):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyoun, Dalila. 2020. "A Longitudinal Study in the L2 Acquisition of the French TAM System" Languages 5, no. 4: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040042

APA StyleAyoun, D. (2020). A Longitudinal Study in the L2 Acquisition of the French TAM System. Languages, 5(4), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages5040042