From Hispanisms to Anglicisms: Examining the Perception and Treatment of Native Linguistic Features Associated with Interference in Translator Training

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Key Notions

| (1) | {Ejercitar/*Ejercitando} | cada | día | es | lo | mejor | |

| {Exercise-inf/Exercise-pseudoger} | every | day | is | the | best | ||

| ‘Exercising every day is the best.’ | |||||||

3. Background and Motivation

| (2) | The church was built by the Germans in the early 19th century. | |||||||||

| (3) | a. | La | iglesia | fue | construida | por | los | alemanes | a | comienzos |

| The | church | was | built | by | the | Germans | at | beginnings | ||

| del | siglo | XIX | ||||||||

| of.the | century | 19 | ||||||||

| b. | #La | iglesia | se | construyó | por | los | alemanes | a | comienzos | |

| The | church | refl | built | by | the | Germans | at | beginnings | ||

| del | siglo | XIX | ||||||||

| of.the | century | 19 | ||||||||

| ‘The church was built by the Germans in the early 19th century.’ | ||||||||||

4. Method

4.1. Participants

4.2. Linguistic Features

| (4) | Encontré | a | Pablo | bailando | en | la | calle | ||

| I.found | acc | Pablo | dancing | in | the | street | |||

| ‘I found Pablo dancing in the street.’ | |||||||||

| (5) | Este | es | un | hermoso | día | ||||

| This | is | a | beautiful | day | |||||

| ‘This is a beautiful day.’ | |||||||||

| (6) | Marcelo | escapó | rápidamente | después | del | choque | |||

| Marcelo | escaped | quickly | after | of.the | crash | ||||

| ‘Marcelo escaped quickly after the crash.’ | |||||||||

| (7) | Esta | institución | fue | creada | en | 1950 | |||

| This | institution | was | created | in | 1950 | ||||

| ‘This institution was created in 1950.’ | |||||||||

| (8) | Necesitas | inscribirte | para | poder | participar | en | el | concurso | |

| You.need | register | to | can | participate | In | the | contest | ||

| ‘You need to register to be able to participate in the contest.’ | |||||||||

4.3. Materials

- Label: Gerunds. Definition: Impersonal verbal forms that in Spanish end with -ndo. Examples: jugando (‘playing’), bailando (‘dancing’).

- Label: Adjectives placed before the noun. Definition: N/A. Examples: hermoso día (‘beautiful day’), altos edificios (‘tall buildings’).

- Label: Adverbs with the ending -mente. Definition: N/A. Examples: rápidamente (‘rapidly, quickly’), efectivamente (‘effectively, indeed’).

- Label: Passive constructions. Definition: Any sentence with the verb ser + participle where the grammatical subject assumes the role of the patient. Examples: La iglesia fue construida a comienzos del siglo XVIII (‘The church was built in the early 18th century’), Pedro fue regañado por su madre (‘Pedro was scolded by his mother’).

- Label: Constructions with the verb poder + infinitive. Definition: N/A. Examples: Al fin podré comer (‘Finally I’ll be able to eat’), Para poder participar hay que estar inscrito (‘In order to be able to participate one must have signed in’).

- Question: {Regarding the use of [label], understood as [definition]/Defining [label] as [definition]/Regarding the use of [label]}, which of the following options corresponds to your experience as a translation student? Options: (a) In general, my instructors have promoted the use of [label] in Spanish or have shown a favorable attitude toward this type of {forms/constructions}; (b) In general, my instructors have not referred to the possibility of using [label] in Spanish or have shown a neutral attitude toward this type of {forms/constructions}; (c) In general, my instructors have discouraged the use of [label] in Spanish or have shown an unfavorable attitude toward this type of {forms/constructions}; (d) My instructors’ attitudes toward the use of [label] in Spanish have been rather heterogeneous.

- Question: Defining an anglicism as any linguistic use coming from English or that imitates uses characteristic of this language13, would you agree to call [label] as anglicisms? Options: (a) Yes; (b) No; (c) I am not sure.

- Question: Personally, do you consider the use of [label], in general, to be acceptable when writing in Spanish and when translating from English to Spanish? Options: (a) Yes; (b) No.

- Question: {Regarding the use of [label], understood as [definition]/Defining [label] as [definition]/Regarding the use of [label]}, which of the following options corresponds to your behavior as a translation instructor? Options: (a) In general, I promote the use of [label] in Spanish or show a favorable attitude toward this type of {forms/constructions} with my students; (b) In general, my attitude toward [label] in Spanish is neutral; (c) In general, I discourage the use of [label] in Spanish or show an unfavorable attitude toward this type of {forms/constructions} with my students.

- Question: Defining an anglicism as any linguistic use coming from English or that imitates uses characteristic of this language, would you agree to call [label] as anglicisms? Options: (a) Yes; (b) No; (c) I would not know.

- Question: Personally, do you consider the use of [label], in general, to be acceptable when writing in Spanish and when translating from English to Spanish? Options: (a) Yes; (b) No.

5. Results

5.1. Overview of Student Responses

5.2. Overview of Instructor Responses

5.3. Stigmatization/Xenofication Scores

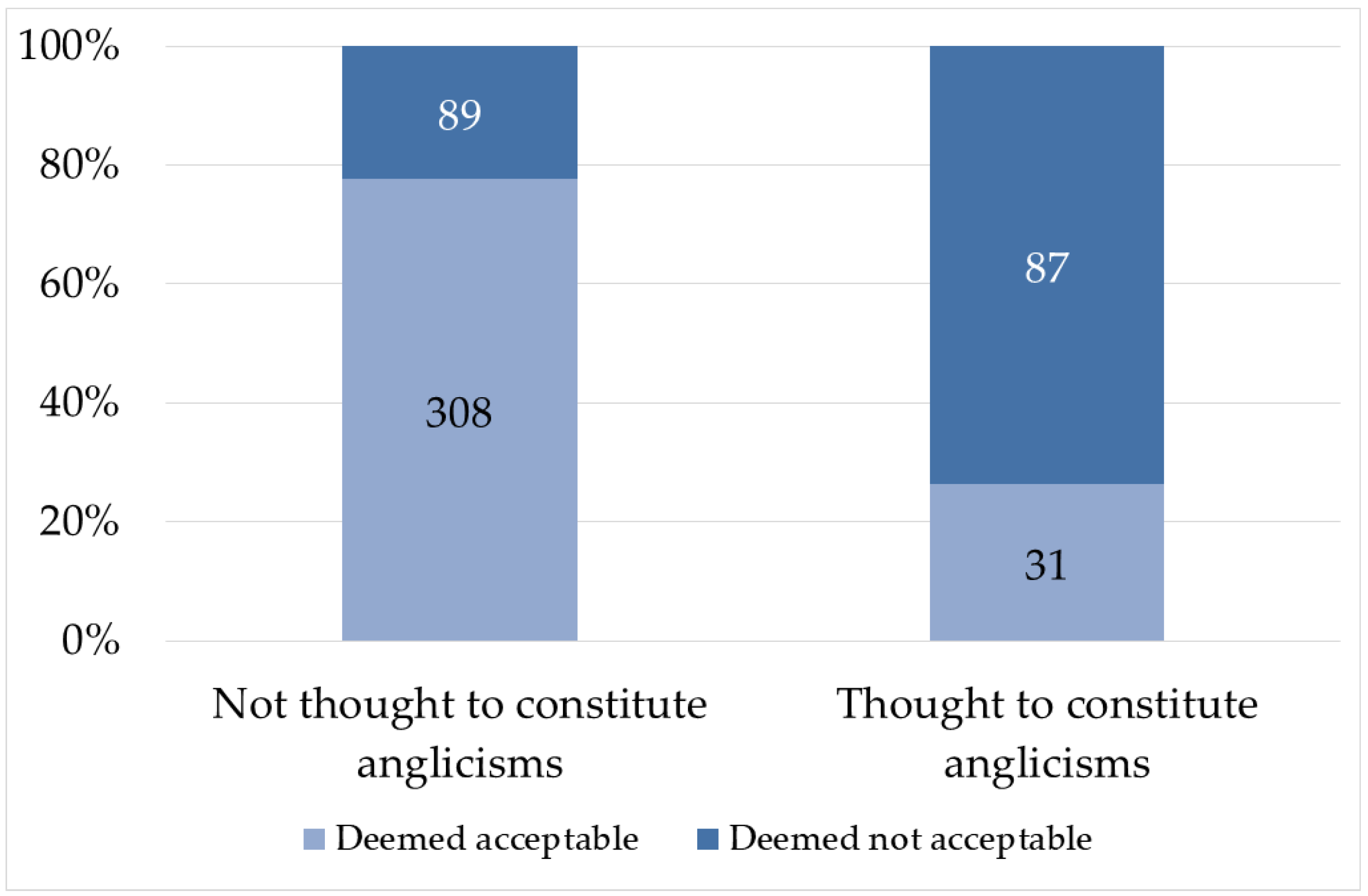

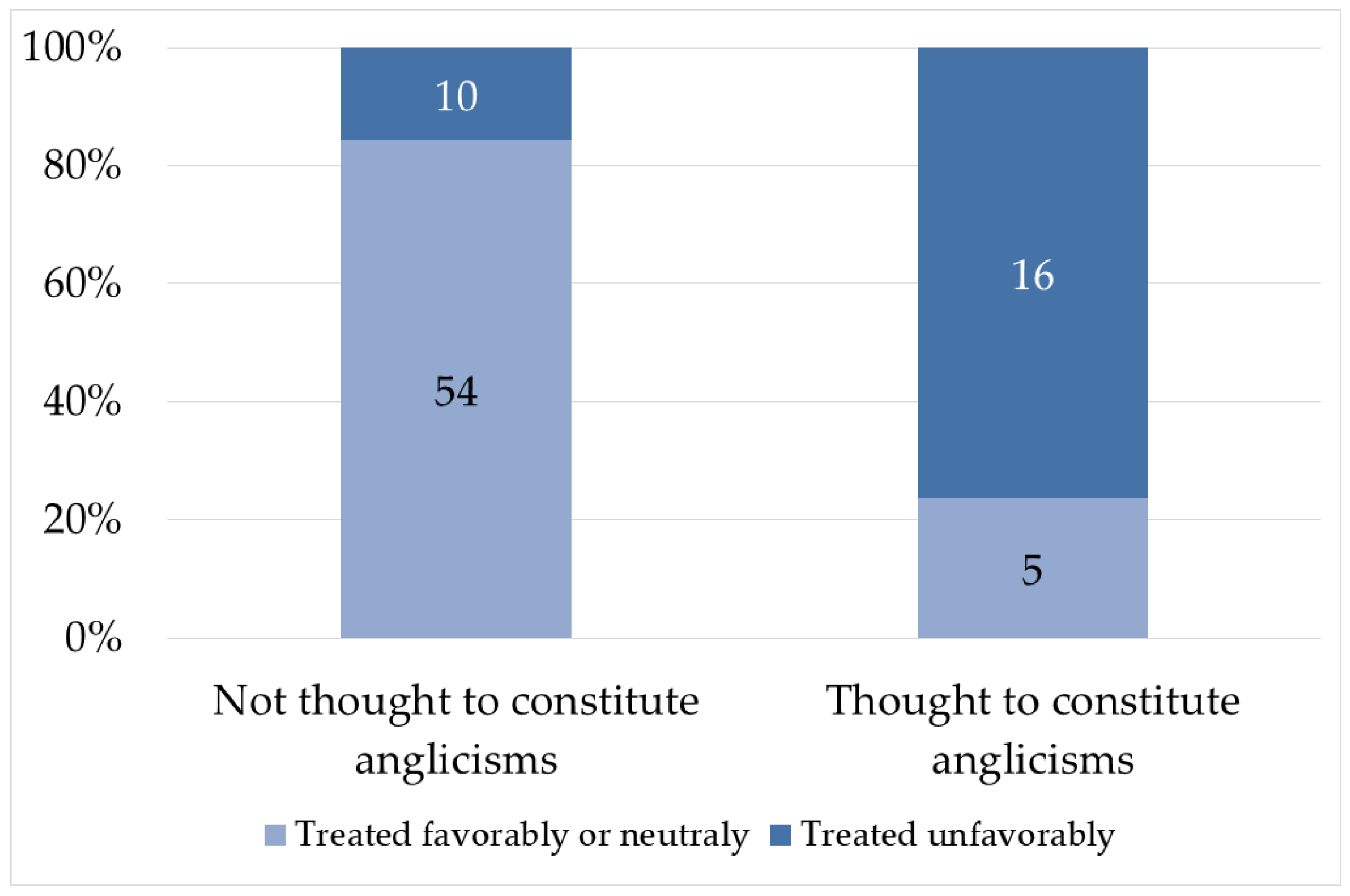

5.4. Examining the Association of Purported Relation to English with Acceptability and Classroom Attitudes

5.5. Comparing the Responses Elicited by the Different Features

5.6. Summary and Discussion

The passive voice is used much more in English than in Spanish, where it is found mostly in literary contexts. The passive voice in Spanish is used with increasing frequency in journalistic prose, but this is considered the result of literal translation from English. For those who are not yet experts in the language, it is best to avoid the passive voice in Spanish.(p. 84)

6. Conclusions

The gerund is often used incorrectly. So deep is the conviction of this fact, that it has come to cause another: the fact that many make strenuous efforts to avoid the gerund when writing, as though they were contemplating a dangerous landscape and preferred to go around it in order to avoid walking through it. But detours are never a good writing procedure. It is possible to navigate through obstacles without problems knowing what and where the obstacles are.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguado de Cea, Guadalupe. 1990. Interferencias lingüísticas en los textos técnicos. In II Encuentros Complutenses en Torno a la Traducción, 12–16 de Diciembre de 1988. Edited by Margit Readers and Juan Conesa. Madrid: Instituto Universitario de Lenguas Modernas y Traductores, Universidad Complutense, pp. 163–96. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcos Llorach, Emilio. 1969. Gramática Estructural, Según la Escuela de Copenhague y con Especial Atención a la Lengua Española. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcos Llorach, Emilio. 1999. Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz Varó, Enrique, and María Antonia Martínez Linares. 1997. Diccionario de Lingüística Moderna. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Anderman, Gunilla, and Margaret Rogers, eds. 2005. In and out of English: For Better, for Worse? Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Arauz, Pedro. 1992. Errores frecuentes en la traducción. In Actas de las I Jornadas Internacionales de Inglés Académico, Técnico y Profesional: Investigación y Enseñanza. Edited by Sebastián Barrueco, Lina Sierra and María José Sánchez. Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, pp. 179–83. [Google Scholar]

- Blas Arroyo, José Luis. 1991. Problemas teóricos en el estudio de la interferencia lingüística. Revista Española de Lingüística 21: 265–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bosque, Ignacio, and Violeta Demonte, eds. 1999. Gramática Descriptiva de la Lengua Española. 3 vols, Madrid: Espasa Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Montoro, M.ª José. 1983. La Voz Pasiva. Madrid: Coloquio. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Lluch, Mónica. 2005. Translación y variación lingüística en Castilla (siglo XIII): La lengua de las traducciones. Cahiers d’Études Hispaniques Médiévales 28: 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claros Díaz, M. Gonzalo. 2016. Cómo Traducir y Redactar Textos Científicos en Español: Reglas, Ideas y Consejos. Barcelona: Fundación Dr. Antonio Esteve. [Google Scholar]

- Company Company, Concepción. 2012. Condicionamientos textuales en la evolución de los adverbios en -mente. Revista de Filología Española 92: 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coseriu, Eugenio. 1977. Sprachliche lnterferenz bei Hochgebildeten. In Sprachliche Interferenz: Festschrift für Werner Betz. Edited by Herbert Kolb and Hartmut Laufferpp. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag, pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu, Eugenio. 1982a. Determinación y entorno: Dos problemas de una teoría del hablar. In Teoría del Lenguaje y Lingüística General: Cinco Estudios. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 282–323. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu, Eugenio. 1982b. Sistema, norma y habla. In Teoría del Lenguaje y Lingüística General: Cinco Estudios. Madrid: Gredos, pp. 11–113. [Google Scholar]

- De Saussure, Ferdinand. 2011. Course in General Linguistics. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Del Rey Quesada, Santiago. 2017. (Anti-)Latinate syntax in Renaissance dialogue: Romance translations of Erasmus’s Uxor Mempsigamo. Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 133: 673–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez de Rodríguez-Pasques, Petrona. 1970. Morfología y sintaxis del adverbio en -mente. In Actas del Tercer Congreso Internacional de Hispanistas. Edited by Carlos Magis. México: El Colegio de México, pp. 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría Arriagada, Carlos I. 2011. Sobre el uso de adverbios en -mente en la traducción inglés-castellano. Paper presented at the XI Congreso Nacional de Estudiantes de Traducción e Interpretación, Valparaíso, Chile, October 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverría Arriagada, Carlos I. 2016a. Actitudes y preferencias de estudiantes de traducción inglés-español frente a recursos gramaticales del español asociados a anglicismos de frecuencia. Estudios Filológicos 58: 67–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría Arriagada, Carlos I. 2016b. La interferencia lingüística de frecuencia. Boletín de Filología 51: 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco Aixelá, Javier. 2019. BITRA—Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation. Available online: http://dti.ua.es/en/bitra/introduction.html (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- García González, José Enrique. 1998. Anglicismos morfosintácticos en la traducción periodística (inglés-español): Análisis y clasificación. Cauce 20–21: 593–622. [Google Scholar]

- García Yebra, Valentín. 1984. Teoría y Práctica de la Traducción. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- García Yebra, Valentín. 1985. Traducción y Enriquecimiento de la Lengua del Traductor: Discurso Leído el Día 27 de Enero de 1985. Madrid: Real Academia Española. [Google Scholar]

- Gili Gaya, Samuel. 1980. Curso Superior de Sintaxis Española. Barcelona: Vox. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, Sylviane, and Helen Swallow. 1988. False friends: A kaleidoscope of translation difficulties. Langage et l’Homme 23: 108–20. [Google Scholar]

- Iguina, Zulma, and Eleanor Dozier. 2008. Manual de Gramática: Grammar Reference for Students of Spanish. Boston: Thomson Heinle. [Google Scholar]

- Jaspert, Nikolas. 2015. An introduction to discourses of purity in transcultural perspective. In Discourses of Purity in Transcultural Perspective (300–1600). Edited by Matthias Bley, Nikolas Jaspert and Stefan Köck. Leiden: Brill, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kabatek, Johannes. 1997. Zur Typologie sprachlicher Interferenzen. In Neue Forschungsarbeiten zur Kontaktlinguistik. Edited by Wolfgang W. Moelleken and Peter J. Weber. Bonn: Dümmler, pp. 232–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman, Eric, and Michael Sharwood Smith, eds. 1986. Crosslinguistic Influence in Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koessler, Maxime, and Jules Derocquigny. 1928. Les Faux Amis, ou les Trahisons du Vocabulaire Anglais. Paris: Libraire Vuibert. [Google Scholar]

- Kussmaul, Paul. 1995. Training the Translator. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro Carreter, Fernando. 1997. El Dardo en la Palabra. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutenberg. [Google Scholar]

- López Guix, Juan Gabriel, and Jacqueline Minett Wilkinson. 1997. Manual de Traducción. Barcelona: Gedisa. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, Emilio. 1991. Anglicismos y traducciones. In Studia Patriciae Shaw Oblata: Quinque Magisterii Lustris Apud Hispaniae Universitates Peractis. Edited by Santiago González y Fernández-Corugedo, Juan E. Tazón Salces, María Socorro Suárez Lafuente, Isabel Carrera Suárez and Virginia Prieto López. Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo, vol. 1, pp. 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, Emilio. 1996. Anglicismos Hispánicos. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Lorian, Al. 1967. Les latinismes de syntaxe en français. Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur 77: 155–69. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Pérez, Pedro Jesús. 1971. Los Anglicismos en el Ámbito Periodístico: Algunos de los Problemas que Plantean. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Vivaldi, Gonzalo. 2000. Curso de Redacción: Teoría y Práctica de la Composición y del Estilo. Madrid: Thomson. [Google Scholar]

- Molina Plaza, Silvia. 1995. Anglicismos léxicos y sintácticos en la traducción literaria de textos del inglés al español. In La Palabra Vertida. Investigaciones en Torno a la Traducción: Actas de los VI Encuentros Complutenses en Tomo a la Traducción. Edited by Rafael Martín-Gaitero and Miguel Ángel Vega. Madrid: Editorial Complutense, pp. 621–28. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, José Joaquín. 2002. La actual crisis de la voz pasiva en español. Boletín de Filología 39: 103–21. [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio, María Teresa. 2005. The influence of English on Italian: The case of translations of economic articles. In In and out of English: For Better, for Worse? Edited by Gunilla Anderman and Margaret Rogers. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Newmark, Peter. 1988. A Textbook of Translation. New York: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Newmark, Peter. 1991. About Translation. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Odlin, Terence. 1989. Language Transfer: Cross-linguistic Influence in Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Chris. 1980. El Anglicismo en el Español Peninsular Contemporáneo. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 12 April 2019).

- Rabadán, Rosa, Belén Labrador, and Noelia Ramón. 2006. Putting meanings into words: English ‘-ly’ adverbs in Spanish translation. In Studies in Contrastive Linguistics: Proceedings of the 4th International Contrastive Linguistics Conference. Edited by Cristina Mourón Figueroa, Moralejo Gárate and Teresa Iciar. Santiago de Compostela: Servicio de Publicaciones, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, pp. 855–62. [Google Scholar]

- RAE = Real Academia Española. 1973. Esbozo de una Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- RAE/ASALE = Real Academia Española and Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española. 2009. Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Espasa Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón, Noelia, and Belén Labrador. 2008. Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English–Spanish parallel corpus. Target 20: 275–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochel, Guy, and María Nieves Pozas Ortega. 2008. Dificultades Gramaticales de la Traducción al Francés. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Medina, María Jesús. 2002. Los anglicismos de frecuencia sintácticos en español. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada 15: 149–70. [Google Scholar]

- Serna, Ven. 1970. Breve examen de unos anglicismos recientes. In Actas del Tercer Congreso Internacional de Hispanistas. Edited by Carlos Magis. México: El Colegio de México, pp. 839–45. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Ross. 1997. English in European Spanish. English Today 13: 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toury, Gideon. 1995. Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Orta, Ignacio. 1986. Un enfoque sistémico de la comparación de las estructuras oracionales pasivas en inglés y en castellano. In Aspectos Comparativos en la Lengua y Literatura de Habla Inglesa. AEDEAN: Actas del IX Congreso Nacional. Edited by Asociación Española de Estudios Anglo-Norteamericanos. Murcia: Asociación Española de Estudios Anglo-Norteamericanos and Departamento de Filología Inglesa, Universidad de Murcia, pp. 203–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Ayora, Gerardo. 1977. Introducción a la Traductología: Curso Básico de Traducción. Washington: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Véliz Ojeda, Eduardo, and Víctor Cámara Cámara. 2010. La “parataxis” como anglicismo de frecuencia en traducciones del inglés al castellano: Análisis desde los estudios culturales. Paper presented at the XI Congreso Nacional de Estudiantes de Traducción e Interpretación, Copiapó, Chile, October 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Venuti, Lawrence. 1998. The Scandals of Translation: Towards an Ethics of Difference. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich, Uriel. 1968. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | All quotes from works in languages other than English have been translated by us. |

| 2 | A reviewer mentions a lack of clarity regarding the relationship between interference as understood in disciplines such as sociolinguistics, applied linguistics, and translation studies. However, even if the term interference has historically been used in different senses in different disciplines, here we have provided a precise definition that can be applied in all the aforementioned disciplines. On the other hand, the phenomena dealt with in these disciplines will obviously often show important differences. Thus, for example, the psycholinguistic processes leading to interference in regular monolingual conversation and in simultaneous interpretation are likely to be quite different, since the first situation involves processing and producing only one language, while the second involves a constant alternation between different languages between processing and production. Yet these differences should be irrelevant for the purposes of the present paper, so long as the phenomena in question can be said to be interferential according to our definition. |

| 3 | In cases of cross-linguistic divergence, it is more appropriate to speak of antianglicisms (see del Rey Quesada 2017, pp. 678–79; Echeverría Arriagada 2016b, pp. 109–10; Lorian 1967, p. 168). |

| 4 | A key underlying distinction here is that between linguistic signs—defined in terms of a signifier and a signified, to use de Saussure’s (2011) terms—and mere phonic forms. As signs, Spanish actual and actualangl are distinguished from each other by different meanings; therefore, they must be treated as different linguistic entities. |

| 5 | The distinction made in the previous note also applies to grammar. Thus, in the case of these gerund-looking forms, we can say that the language user is using phonic forms that normally correspond to Spanish gerunds, but not that he or she is using actual Spanish gerunds, since this grammatical class (as it exists in Spanish) is defined not only by a phonic form, but also (and most importantly) by a particular grammatical meaning. |

| 6 | Echeverría Arriagada (2016b, p. 110) provides a useful analogy for understanding the problem. If a frequency anglicism is defined in strictly statistical terms, as the relative overuse of a linguistic element of the local or target language due to English influence, then referring to the linguistic elements involved in this type of phenomenon as though they were anglicisms in themselves is comparable to confusing a fish with its shoal. |

| 7 | We use the term xenofication (suggested to us by Trevor Bero) to refer to the action of treating something (e.g., a linguistic feature) as foreign or alien to the local environment (see Jaspert 2015, p. 6). The notion of xenofication, thus defined, should not be confused with that of foreignization, which has to do with “how much a translation assimilates a foreign text to the translating language and culture, and how much it rather signals the differences of that text” (Venuti 1998, p. 102). |

| 8 | This is something we have seen in person several times in the translation classroom. Of course, here one could also use an active sentence like Los alemanes construyeron la iglesia a comienzos del siglo XIX (‘The Germans built the church in the early 19th century’). However, this option would not preserve the order of the original, something one might want to do for pragmatic reasons. On the other hand, a sentence like La iglesia la construyeron los alemanes a comienzos del siglo XIX could have an undesired focalizing effect. |

| 9 | Only in one of these institutions were students trained in a third working language. |

| 10 | Naturally, space constraints make it impossible to delve into the peculiarities of these types of linguistic elements in Spanish, which in any case are not relevant for our purposes. For a general characterization, see, (e.g., Alarcos Llorach 1969, 1999; Bosque and Demonte 1999; Gili Gaya 1980; RAE/ASALE 2009). |

| 11 | On the distinction between these different phenomena of qualitative and quantitative interference, see Echeverría Arriagada 2016b, pp. 103–104. It should be noted that the distinction is sometimes not made consistently. This seems to be the case, for example, in Rodríguez Medina’s (2002) study, since, after distinguishing between frequency anglicisms and “innovative” anglicisms, the author says that “[w]hen the gerund becomes a syntactic frequency anglicism, due to its repetitive use, it appears in certain contexts carrying functions that are alien to it” (p. 162). |

| 12 | It should be noted that in focusing on these types of elements we are not making any assumptions about English–Spanish equivalences or correspondences (or the lack thereof). |

| 13 | A reviewer believes to have detected two different notions of anglicism in this study. Specifically, he or she claims that anglicisms are defined as discourse phenomena in the questionnaires, while being treated as belonging to the language system earlier in the paper. Nevertheless, from the start, we have explicitly placed interference phenomena in general (including anglicisms) on the level of discourse, in accordance with Weinreich. It should be noted, however, that this does not prevent us from labeling certain abstract linguistic units as interference phenomena, as long as they only exist as an outcome of interference in the contexts under consideration (e.g., the case of actualangl in Spanish-speaking contexts, discussed in Section 2, as defined across occurrences). |

| 14 | This led us to discard three additional groups of questions originally included in the survey (two from the student questionnaire and one from the instructor questionnaire), as after further consideration we determined that the phrasing of these questions could elicit reports pertaining specifically to particular discursive instances of the features of interest, instead of to the features as such. |

| 15 | Logically speaking, the propositions “A is an X” and “A can occur as an X” are very different. Compare, for example, the sentences H2O can occur as an ice cube and #H2O is an ice cube. |

| 16 | S/X scores are presented as a compound measure of the perception and treatment of the target elements, merging the concepts of stigmatization and xenofication into a single, broader concept. Thus, these scores do tell us not about the stigmatization and xenofication of the target elements separately, but only in the aggregate. The rationale for this, other than practical convenience, is that stigmatization and xenofication, as expected, are closely related in the data. |

| 17 | Here we only considered instructors’ responses about their own classroom behavior considering that students’ responses on their instructors’ attitudes correspond to subjective impressions of the cumulative behavior of several individuals. |

| 18 | All statistical tests were performed with R (R Core Team 2019). |

| 19 | “French and English use the passive […] in proportions much higher than our language. It is convenient that translators bear this preference in mind, in order to avoid stylistic shortcomings and even grammatical errors” (RAE 1973, p. 451). |

| Favorable | Neutral | Unfavorable | Heterogeneous | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerunds | 9 (10%) | 3 (4%) | 60 (70%) | 14 (16%) |

| Prenominal adjectives | 1 (1%) | 17 (20%) | 40 (46%) | 28 (33%) |

| -mente adverbs | 16 (19%) | 23 (27%) | 22 (25%) | 25 (29%) |

| Passive constructions | 3 (4%) | 6 (7%) | 64 (74%) | 13 (15%) |

| poder + infinitive | 7 (8%) | 56 (65%) | 4 (5%) | 19 (22%) |

| Yes | No | Not Sure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gerunds | 9 (11%) | 62 (72%) | 15 (17%) |

| Prenominal adjectives | 31 (36%) | 41 (48%) | 14 (16%) |

| -mente adverbs | 7 (8%) | 63 (73%) | 16 (19%) |

| Passive constructions | 41 (48%) | 31 (36%) | 14 (16%) |

| poder + infinitive | 9 (11%) | 45 (52%) | 32 (37%) |

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Gerunds | 46 (53%) | 40 (47%) |

| Prenominal adjectives | 47 (55%) | 39 (45%) |

| -mente adverbs | 76 (88%) | 10 (12%) |

| Passive constructions | 33 (38%) | 53 (62%) |

| poder + infinitive | 77 (90%) | 9 (10%) |

| Favorable | Neutral | Unfavorable | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gerunds | 5 (29%) | 4 (24%) | 8 (47%) |

| Prenominal adjectives | 3 (18%) | 11 (65%) | 3 (17%) |

| -mente adverbs | 1 (6%) | 4 (23%) | 12 (71%) |

| Passive constructions | 2 (12%) | 6 (35%) | 9 (53%) |

| poder + infinitive | 2 (12%) | 12 (70%) | 3 (18%) |

| Yes | No | Not sure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gerunds | 5 (29%) | 11 (65%) | 1 (6%) |

| Prenominal adjectives | 3 (18%) | 13 (76%) | 1 (6%) |

| -mente adverbs | 3 (18%) | 12 (70%) | 2 (12%) |

| Passive constructions | 13 (76%) | 4 (24%) | 0 (0%) |

| poder + infinitive | 8 (47%) | 9 (53%) | 0 (0%) |

| Yes | No | |

|---|---|---|

| Gerunds | 12 (71%) | 5 (29%) |

| Prenominal adjectives | 11 (65%) | 6 (35%) |

| -mente adverbs | 14 (82%) | 3 (18%) |

| Passive constructions | 10 (59%) | 7 (41%) |

| poder + infinitive | 13 (76%) | 4 (24%) |

| I1 a | I2 b | I3 c | I4 d | I5 e | I6 f | Total Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerunds | 7.0 | 1.1 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 23.3 |

| Prenominal adjectives | 4.6 | 3.6 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 3.5 | 19.7 |

| -mente adverbs | 2.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 15.2 |

| Passive constructions | 7.4 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 7.6 | 4.1 | 35.4 |

| poder + infinitive | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 11.5 |

| Comparison | χ2 | DF | p | p’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students’ responses on instructor classroom behavior (N = 172 in each test) | ||||

| Passive constructions vs. gerunds a | 4.17 | N/A | 0.26 | 0.78 |

| Passive constructions vs. prenominal adjectives a | 17.29 | N/A | <0.001 | 0.009 ** |

| Passive constructions vs. -mente adverbs | 43.16 | 3 | <0.001 | <0.001 *** |

| Passive constructions vs. poder + infinitive a | 98.86 | N/A | <0.001 | 0.0050 ** |

| Instructors’ responses on their own behavior in the classroom (N = 34 in each test) | ||||

| Passive constructions vs. gerunds a | 1.74 | N/A | 0.53 | 1 |

| Passive constructions vs. prenominal adjectives a | 4.67 | N/A | 0.13 | 0.50 |

| Passive constructions vs. -mente adverbs a | 1.16 | N/A | 0.55 | 1 |

| Passive constructions vs. poder + infinitive a | 5.00 | N/A | 0.09 | 0.46 |

| Overall responses to whether the target elements constitute anglicisms (N = 206 in each test) | ||||

| Passive constructions vs. gerunds | 37.03 | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 *** |

| Passive constructions vs. prenominal adjectives | 8.64 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Passive constructions vs. -mente adverbs | 45.30 | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 *** |

| Passive constructions vs. poder + infinitive | 30.38 | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 *** |

| Overall acceptability judgments (N = 206 in each test) | ||||

| Passive constructions vs. gerunds | 3.81 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.36 |

| Passive constructions vs. prenominal adjectives | 3.81 | 1 | 0.05 | 0.36 |

| Passive constructions vs. -mente adverbs | 44.90 | 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 *** |

| Passive constructions vs. poder + infinitive | 44.90 | 1 | <0.001 | <0.001 *** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Echeverría, C.I.; González-Fernández, C.A. From Hispanisms to Anglicisms: Examining the Perception and Treatment of Native Linguistic Features Associated with Interference in Translator Training. Languages 2019, 4, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4020042

Echeverría CI, González-Fernández CA. From Hispanisms to Anglicisms: Examining the Perception and Treatment of Native Linguistic Features Associated with Interference in Translator Training. Languages. 2019; 4(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleEcheverría, Carlos I., and César A. González-Fernández. 2019. "From Hispanisms to Anglicisms: Examining the Perception and Treatment of Native Linguistic Features Associated with Interference in Translator Training" Languages 4, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4020042

APA StyleEcheverría, C. I., & González-Fernández, C. A. (2019). From Hispanisms to Anglicisms: Examining the Perception and Treatment of Native Linguistic Features Associated with Interference in Translator Training. Languages, 4(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages4020042