1. Introduction: Ecological Approaches to Composition and Language Learning

Regardless of how engrossed they may be in their smartphones, students heading to class travel through places that play a major role in their identity formation. However, if their mobile technology and their academic courses both end up drawing students’ minds away from their lived environments, then something is truly lost in their education, especially for students learning English or another language. Nonetheless, teachers often employ technology-based strategies to enhance language learners’ engagement with their surroundings. The concept of “mobile-assisted language learning” (“MALL”) has typically focused on the technological devices students use (e.g.,

Schenker and Kraemer 2017), but

Rocca (

2018) has recently called for further research on the inherent mobility of language learners: “A mobile language learner is a learner on the move because they keep their learning moving along in various environments, inside and outside the classroom, and through various resources, mobile and/or stabile” (p. 2). Shifting emphasis toward “mobile language learning” (“MoLL”) therefore seeks to integrate not only learning technologies but also any kind of human-made or natural resource in students’ environments—much in the same way that numerous educators have been applying ecological approaches in language and composition classrooms.

The emergence of ecocomposition—the linking of ecology and composition—in college English classrooms has paralleled the rise of sociocultural and other context-oriented theories of second language acquisition (SLA). Although there is considerable debate among SLA theorists, researchers have generally agreed that learning to speak and write in a new language occurs as a process embedded in a social context (

Lantolf 2012;

Leki 2010;

Mackey et al. 2012). Ecocomposition represents a similar turn toward context, emphasizing not only the social milieu but also the broader physical ecosystem in which writing takes place (

Dobrin 2001;

Dobrin and Weisser 2002;

Moekle 2012;

Weisser and Dobrin 2001). Ecocomposition theorists such as

Dobrin (

2001) point to

Cooper (

1986) as the first to propose an ecological metaphor of seeing all writing as interwoven in a web-like social system, in which each writer not only adapts to others but also exerts influence on the ecosystem as a whole (

Dobrin 2001, p. 20).

Syverson (

1999) further theorized an “ecology of composition” as a dynamic “meta-complex system” that unites multiple levels of complex systems in which a writer participates (p. 5), and she provided case studies to demonstrate the appeal of such an ecological framework. As the field of ecocomposition grew, theorists began exploring the totality of interrelationships among writers, readers, discourses, non-human lifeforms, bioregions, and individual locations, thus leading to innovations in composition pedagogy (

Dobrin 2001;

Dobrin and Weisser 2002).

Just as composition instructors have been increasing efforts to bring ecological content into composition classrooms, language educators have also been seeking to integrate concepts from ecology into second language pedagogy.

Van Lier (

2004) for instance brings ecological theories into conversation with Vygotskian sociocultural approaches to SLA, proposing an “ecology of language learning” based on a worldview that recognizes humanity’s intertwinement with the global ecosystem. With awareness about environmental issues continually rising, educators across the world have been applying environmental content-based instruction in ESL/EFL classrooms over the past three decades (

Hauschild et al. 2012;

Jacobs et al. 1998;

Li 2013;

McRae 1998;

Nkwetisama 2011;

Tangen and Fielding-Barnsley 2007;

Vakhromova 2011). Teachers of various subjects have reported successful engagement of English language learners in response to place-based activities, which connect students to local natural and community resources in order to support learning of English, science, and other subjects (

Manookin 2018;

Powers 2004;

Smith and Sobel 2010;

Sobel 2005;

Westervelt 2007).

In the field of English composition studies, scholars such as

Elsherif (

2013) and

Rioux (

2016) argue for the benefits of ecocomposition pedagogy and place-based writing in ESL and multilingual classrooms. However, although a number of researchers have reported on the integration of place-based and ecological content into language courses, there is need for further cross-fertilization between the fields of ecocomposition and second language acquisition.

In this essay, I share my experience developing a place-based compare–contrast writing and multimedia assignment for ESL composition students at a U.S. university. I then argue for this assignment’s applicability in secondary education and collegiate language learning contexts due to its grounding in theories of content-based language instruction and place-based ecocomposition.

2. Reinvigorating the Compare–Contrast Genre

A number of scholars have discussed using campus ecology to engage students in college composition classes (

Manookin 2018;

Monsma 2001), but they do not specifically discuss the usage of the compare–contrast genre, which is a popular genre in secondary schools and colleges because of its emphasis on analytical skills and textual organization. Several experimental studies have focused on instructional methods for teaching compare–contrast writing in secondary education settings (

Hammann and Stevens 2003;

Kirkpatrick and Klein 2009;

MacArthur and Philippakos 2010), but there is need for further research on using this genre in ESL/EFL, world language, and environmentally-based learning contexts

When teaching the compare–contrast genre, teachers commonly face difficulty in helping students select original topics to compare. In advanced second language composition courses, students may be expected to choose topics that are more academically-oriented than simply comparing two animals, two holidays, or two countries. As an instructor of college ESL composition, I realized that one way to help students narrow down appropriate topics for comparison is by asking them to select two places in their immediate environment and to conduct in-person and online research on those locations. While the compare–contrast essay can be considered an abstract or even stale genre, a place-based approach transforms this assignment into an opportunity to build on the inherent mobility of language learners traversing a broader ecosystem.

One perhaps underemphasized resource for place-based language learning is the presence of architectural and engineering technologies that students experience in their daily lives. Since students taking college ESL courses are usually either international students or immigrants, exploring their campus environments can be a stimulating intercultural experience. Campus environments often showcase a range of building designs and other striking landscapes such as monuments, gardens, and green spaces. From architecture echoing Greco-Roman classical forms to more modern designs featuring abstract geometry and eco-friendly engineering, the structures on U.S. college campuses embody a variety of rhetorical messages about the character of their academic communities. Because of the potential for campus spaces to provide rich content for students to compare and write about, I modified my department’s required compare–contrast assignment by instructing students to write their essays on two of their favorite buildings or spaces on campus.

3. The Design of the Assignment: Essay and Oral Slideshow Presentation

According to department guidelines at my university, the second assignment in first-year ESL composition courses requires a compare–contrast essay of about 700–900 words and a brief oral presentation accompanied by visual aids. The students transition into this compare–contrast unit, which takes about four weeks, after having completed a definition essay assignment that emphasizes basic writing concepts such as thesis statements, structure, and topic sentences. In my course, I use the compare–contrast essay to teach research and citation skills (using APA format), methods of generating points of comparison for analyzing their chosen topics, and text structure, for which students have the option of using a point-by-point structure or a subject-by-subject structure, as explained in their course textbook (

Rosa and Eschholz 2012).

With departmental support, I modified this assignment to require students to choose two locations or buildings on campus, and I devised a series of lessons to raise students’ awareness of the sustainable design technology and rhetorical messages embodied in the architecture on campus. To support students’ research, I introduced a variety of online and print resources published by the university, such as campus news websites, historical articles at the library website, and a photographic tour book (

Stout et al. 2006). An especially useful source was a university “green-tour” website featuring pictures and articles about eco-friendly technologies used in various green spaces and campus buildings, many of which have been awarded Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certifications by the U.S. Green Building Council (

Pennsylvania State University n.d.b). I also demonstrated how to find credible sources about eco-friendly design principles and the history of architecture using the Gale Virtual Reference Library database, which includes thousands of online encyclopedias and reference books. These resources empower students to evaluate the environmental and aesthetic impact of the various campus locations they have chosen to compare.

The assignment also prompts students to compare and contrast how their chosen spaces use rhetorical techniques to communicate messages about the university. Rhetorical analysis is an essay genre of its own, commonly employed in L1 English composition courses. As rhetorical theorists such as

Glenn (

2017) have for several years defined rhetoric as “the purposeful use of language and images” (p. 3), many of today’s compositionists seek to raise students’ awareness of the rhetorical messages surrounding us in our daily lives (

Lunsford and Ruszkiewicz 2016). Using the rhetorical triangle diagram—which poses the author, the message, and the audience as the three sides of a rhetorical context—I ask students to consider the campus designers and architects as “authors” sending particular messages to a rhetorical audience made up of students, staff, and visitors. I originally experimented with applying the rhetorical triangle to campus in a previous L1 composition course, in which I had students write essays about campus spaces using the rhetorical analysis strategies covered in

Lunsford and Ruszkiewicz’s (

2016) composition textbook,

Everything’s an Argument. For the compare–contrast essay in my ESL composition courses, I encouraged students to synthesize their online research about various styles of neo-classical, modernist, and sustainable architecture in order to evaluate the possible rhetorical messages that their favorite campus spaces are sending to students and staff.

Students’ research for this assignment also incorporates ground-level observations. Students are instructed to take notepads and their smartphones to their locations of inquiry so they can jot down their thoughts and take photos to be used in their slideshow presentations. In order to introduce students to ground-level research methods during the first week of this unit, I incorporate a lesson that sends students in small groups to conduct an outdoor rhetorical analysis activity and report their findings to the class at the end of the period.

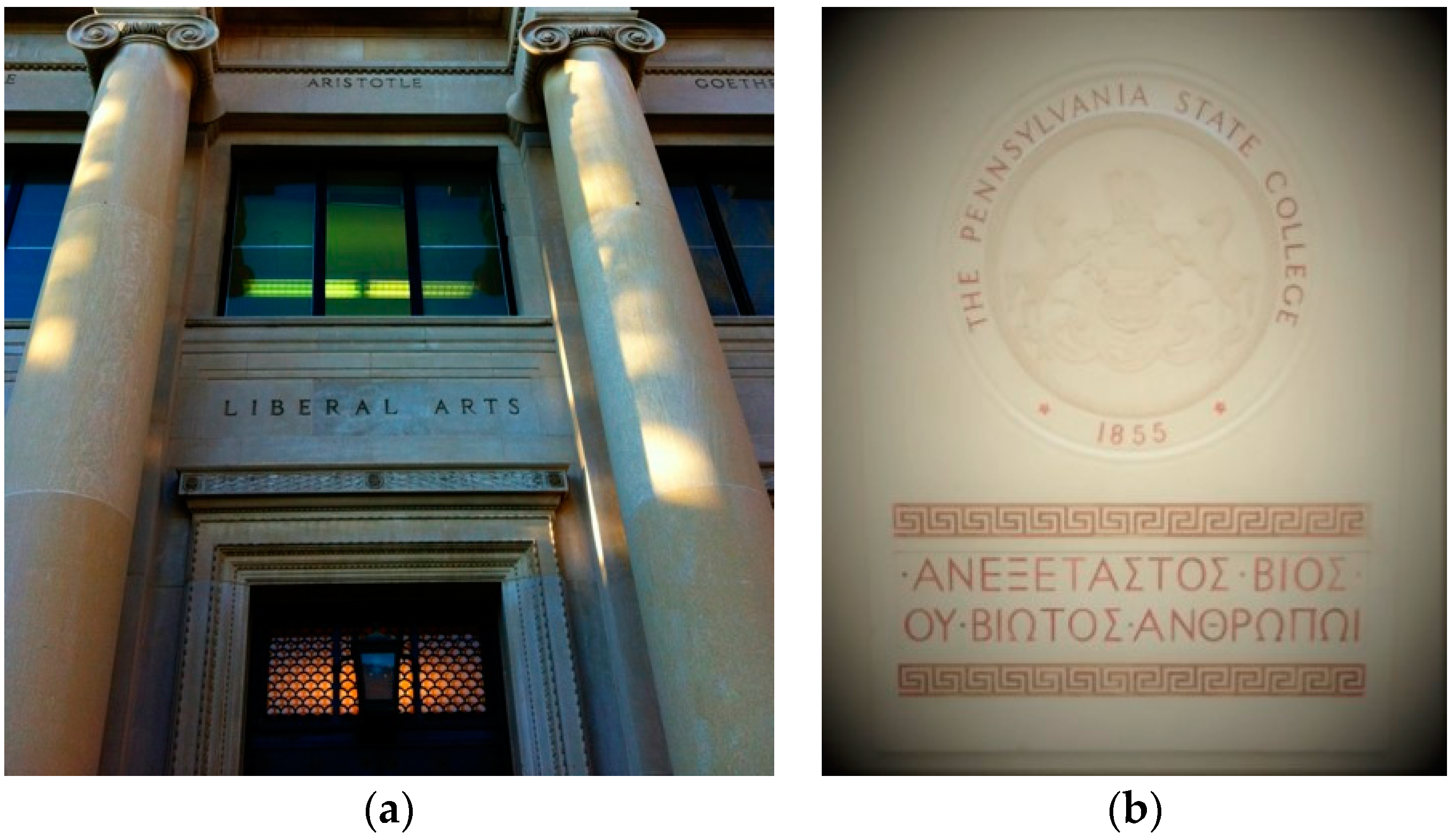

At the beginning of this lesson, I present a slideshow with pictures of a few campus buildings and briefly model how to analyze the rhetorical messages these buildings send. One building I discuss, devoted to the liberal arts, features neoclassical pillars outside, while a wall in the foyer displays the Ancient Greek text of a famous quote by Socrates from Plato’s Apology (38a), which can be translated as “the unexamined life is not worth living” (

Plato 2002, p. 41) (

Figure 1). I ask students to discuss why they think the university displays this quote and what this represents about campus history.

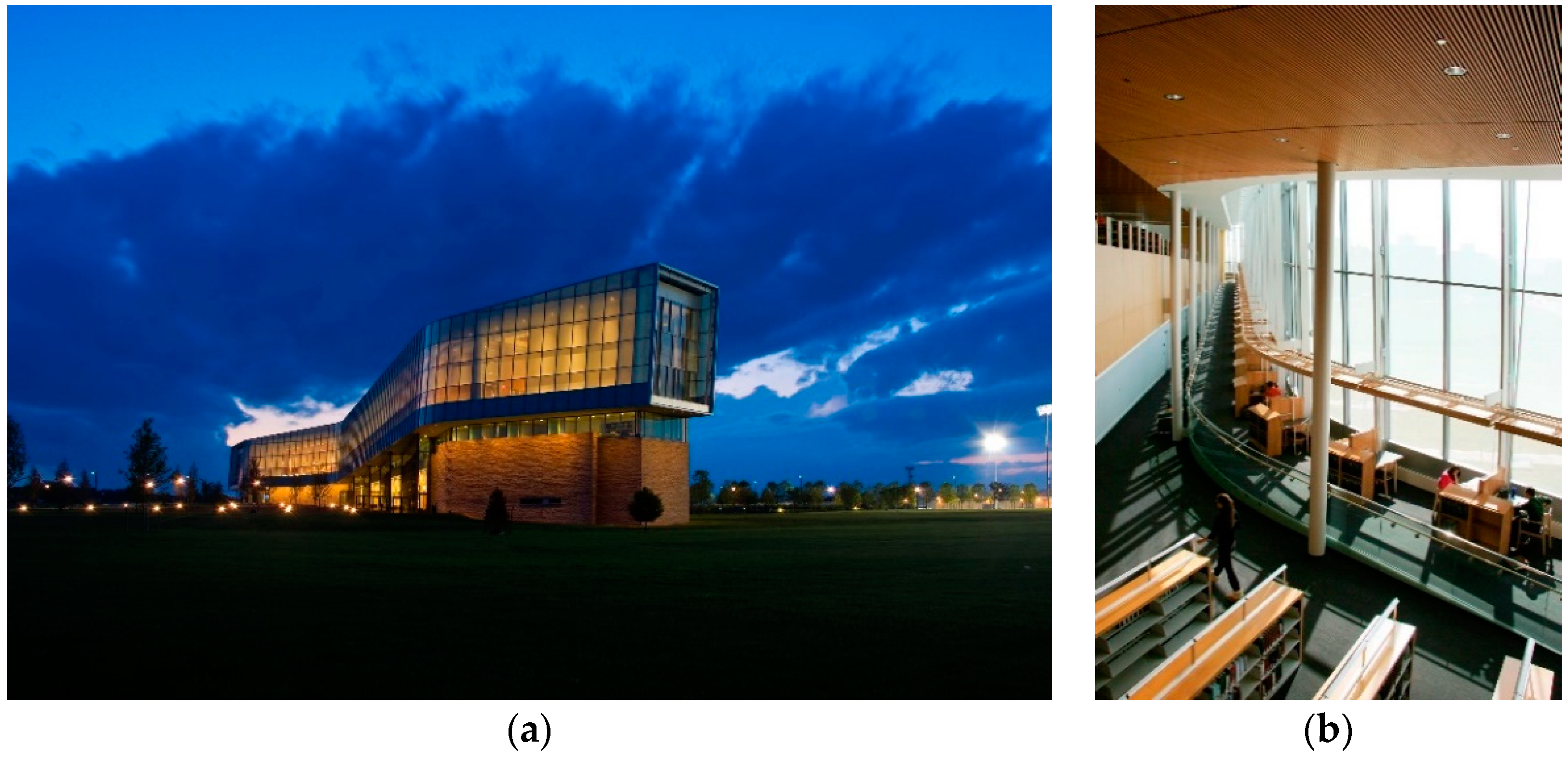

Then we look at pictures of the Penn State law school building, which features postmodern glass-based architecture and well-lit, airy study spaces, and I also show them the webpage that explains the building’s use of eco-friendly architecture (

Pennsylvania State University n.d.a) (

Figure 2). We then discuss the rhetorical messages that students might receive through experiencing the building’s innovative design, which activates their thinking for the next task.

I then send the students outside in small groups to analyze notable features within a few hundred meters of their classroom, and to prepare a brief group presentation for the class. I ask one student from each group to take a few photos of what they notice and immediately email them to me with their smartphones. When students return, I project their pictures on the front screen while each group stands up to explain their pictures and the rhetorical messages they encountered while walking outside. At the end of class, I emphasize the importance of taking a similar approach when conducting ground-level research for their own projects.

After students have drafted and peer-reviewed their essays, the compare–contrast unit culminates in a class period devoted to small group presentations. Students prepare a slideshow with photographs of their two chosen campus spaces and present four-minute presentations on the key findings they wrote about in their compare–contrast essays. In order to reduce performance anxiety and promote students’ confidence, I arrange the seats in the classroom so that presentations are conducted simultaneously in groups of about five students, who display their slideshows on laptops or tablets. Thus, the students practice technical communication skills through designing their slideshows and incorporating their own photographs and captions. The students present their slideshows three times total for different groups of students, and a few minutes are provided after each presentation for small group discussion. As a result of this communal presentation experience, the English language learners practice their speaking skills while also learning from one another about their shared campus environment.

4. Personal Reflections on Students’ Experiences

While using this assignment over three semesters in 2017–2018, I have made several personal observations that I would like to share. Since the content of my lessons gave an overview of three themes—visual rhetoric on campus, the history of architecture, and sustainable design—students’ essays tended to focus on one or more of these themes, in varying combinations.

Some students wrote and presented on how campus architecture is often designed to appeal to students emotionally, both to create a mood conducive to studying and to connect them to campus culture, including the historical liberal arts tradition. Several students argued that various campus spaces and buildings have the ability to evoke emotions of pride in their school, to induce meditative states that support students’ concentration on their schoolwork, and to promote a sense of professionalism due to the formality of certain spaces. In my assessment of their papers and presentations, I believe this group of students expressed awareness that the school is using visual rhetoric to influence their study habits and attitudes toward the school.

Another group of students, which overlaps with the first group of students discussed above, chose to focus on the use of sustainable design on campus. A number of students discussed the countless decisions that go into designing eco-friendly buildings, from choosing sustainably-sourced materials to determining the most efficient use of sunlight and rainwater. Among this group of students, some students also emphasized that the presence of these features, which are well-publicized, rhetorically communicates the university’s ethical message about sustainability and the need to limit greenhouse emissions.

I have noticed that many college students are inherently interested in local campus history and in environmentally-conscious design, and I believe that these aspects of the assignment motivated students to put effort into learning how to cite research appropriately and how to structure their essays. In my opinion, I also found that using the compare–contrast genre stimulated students’ thinking by encouraging them to ask focused questions about each location in light of the research they found about the other location. It has also been stimulating for me as a teacher to learn more about my workplace as I prepared these lessons and read student papers, and I gained insight into students’ perceptions about the values that the university is conveying through the architecture and engineering of campus spaces.

One limitation of this essay is that my conclusions are based on my personal observations, rather than on formally collected data. In the future, I believe it may be profitable to conduct a more formal study on campus-based writing in ESL courses in order to corroborate the observations I have made about students’ positive reception of this assignment.

5. Discussion

There are a number of theoretical considerations that lead me to recommend this campus space compare–contrast assignment for adoption in ESL/EFL college composition courses, world language composition courses, and U.S. high school ESL programs. With modifications for their own program objectives and unique locality, instructors in various contexts may find this assignment beneficial for motivating intermediate and advanced language learners to tackle challenging research writing objectives. In addition, students who are newcomers to a local bioregion may initially feel alienated from their environment, but I argue that this assignment has the potential to reduce feelings of alienation and can even help students understand their environmental responsibilities in a hypermobile world. Grounded in theories of content-based instruction, place-based education, and ecocomposition, this assignment offers two main benefits for international and immigrant students in college and high school environments: enhancing students’ motivation to work on linguistic skills and raising students’ sense of satisfaction and belonging on campus. Researchers and theorists have argued that these benefits are linked to various instructional practices that I have endeavored to embody in the campus space compare–contrast assignment.

5.1. Content-Based Instruction

Lyster (

2007) broadly defines content-based instruction as any form of teaching that uses subject matter “as a means for providing second language learners with enriched opportunities for processing and negotiating the target language through content” (p. 1).

Hauschild et al. (

2012) specifically advocate the use of environmentally-themed content-based instruction for its ability to strengthen language skills while helping students “become more informed citizens, both locally and globally” (pp. 1–2).

Lyster (

2007) reports that many researchers have found that content-based instruction, which synthesizes linguistic and cognitive development, provides the “requisite motivational basis for purposeful communication” and increases students’ contact with meaningful discourse in the target language (p. 2). In my courses, the compare–contrast assignment encouraged students to explore rich content and develop their own perspectives about how to compare campus spaces. I noticed that while comparing the buildings, monuments, gardens, and other kinds of spaces, students developed questions based on their own interests and personal observations, thus gaining motivation to search for sources with content on a wide range of subjects, including U.S. and local history and culture, architectural styles, sustainable engineering, environmental science, and psychology. During this compare–contrast unit, students needed to search for vocabulary to communicate their experiences with concrete locations, they encountered new vocabulary in their research, and they also practiced manipulating advanced concepts when writing their essays and giving their presentations.

Because students were sharing their own discoveries about campus, I believe they gained the requisite motivation to organize their points using an appropriate essay structure, to provide accurate citations, and to showcase their interpretive skill—all of which require intense cognitive focus. To support this process, I scheduled individual conferences to assess their rough drafts and discuss how they might revise their essay structures. In addition, the prospect of orally presenting a slideshow with their own photographs to their peers seemed to motivate them to enhance the professionalism of the design and execution of their presentations. Although most of the presentations were given in an intimate setting of small groups, I also encouraged a handful of students to present using the front screen before the whole class since some of them were interested in tackling this kind of professional communication task. On presentation day, students would play the role of tour guides sharing the deeper significance of their own corners of campus for an interested audience.

In my experience, many students brought prior interests in solving environmental issues, and they found the engineering and sustainability content of their research to be engaging. From their own research and from viewing classmates’ presentations, students had several opportunities to gain a holistic understanding of the lifespan environmental impact of buildings, including factors related to the procurement of materials, the maintenance of the building, and even the ability to recycle the building in the future. At my university, many international students come to the U.S. to study engineering, economics, and business, and thus they resonated with these lessons on sustainability embedded on campus, and ultimately every academic and professional discipline can benefit from incorporating an ecological perspective. As

Moekle (

2012) states, “Bringing sustainability into the undergraduate experience through courses in rhetoric and composition is valuable precisely because the many challenges of sustainability will be solved not only through science and policy, but through writing studies that focus on communicative acts among various audiences” (p. 83). A number of my students went on to write about solutions for environmental problems for their final research essay at the end of the semester, and ultimately I would argue that the content of this compare–contrast unit empowers students with the vocabulary and concepts needed to voice their perspectives both on campus and beyond whenever they encounter environmental issues.

5.2. Ecocomposition and Place-Based Education

The application of community-oriented ecological content in the composition classroom goes by many names. I am primarily classifying this compare–contrast assignment as an ecocomposition assignment, but it also qualifies as place-based education, which is closely related. Although the concepts of ecocomposition and place-based education overlap, ecocomposition focuses on writing and rhetoric about any kind of ecological topic, whereas place-based education uses students’ immediate environment and can be implemented in almost any field of teaching and learning.

Dobrin (

2001) characterizes ecocomposition as an “inquiry for action” that investigates “the relationship between discourse, nature, environment, location, place, and the ways in which these categories get mapped, written, codified, defined, and in turn, the way in which nature and environment affects discourse” (p. 14). In discussing the definition of ecocomposition,

Dobrin (

2001) argues that it is better to leave the term open-ended rather than to strictly codify its definition, especially since he sees ecocomposition as more of a spatial metaphor, as a “site for the kind of activism that resists the oppression not just of nonhuman organisms and environments, but of all oppressive structures” (p. 14). This holistic approach recognizes that environmental problems often overlap with social justice issues related to race, class, gender, culture, and other demographic factors, as emphasized by a number of scholars of ecocomposition and ecocriticism (

Dobrin and Weisser 2002, p. 175;

Lynch et al. 2012, pp. 4–6;

Moekle 2012, p. 77;

Owens 2001a, p. xiii;

Reynolds 2004, p. 11).

Compared to ecocomposition, which is broad enough to incorporate topics about anywhere in the world, place-based education by definition takes the students’ current location as the starting point of inquiry.

Smith and Sobel (

2010) point out that an increasing number of educators in various fields are adopting location-oriented approaches, which go by various names such as service learning and environmental education. In response to these various approaches,

Smith and Sobel (

2010) argue that the terms “place-based” and “community-based” are the most effective for capturing the need to balance both human and “more-than-human” interests: “What place- and community-based education seeks to achieve is a greater balance between the human and non-human, ideally providing a way to foster the sets of understanding and patterns of behavior essential to create a society that is both socially just and ecologically sustainable” (p. 22). In addition, place-based education can be applied not only in rural or wilderness environments, but also in suburban and urban environments, where students may confront links between environmental degradation and social inequality in their daily lives (

Leou and Kalaitsidaki 2017;

Russ and Krasny 2017). Thus, place-based education shares ecocomposition’s holistic approach to ethics, society, and the environment.

In recent decades, educators have been using place-based approaches at all levels of schooling for teaching a variety of subjects, including ESL, English, science, and social studies (

Manookin 2018;

McRae 1998;

Monsma 2001;

Powers 2004;

Smith and Sobel 2010;

Sobel 2005;

Tangen and Fielding-Barnsley 2007;

Westervelt 2007). In a study evaluating four place-based education programs in primary and secondary schools,

Powers (

2004) reports that teachers noticed enhanced engagement not only among students in general, but also among English language learners and students with special needs (pp. 26–28). In college composition contexts,

Monsma (

2001) testifies to the positive impact on student writing resulting from using his campus as a resource for place-based composition assignments, and

Manookin (

2018) discusses the use of nature-based writing for engaging English language learners in her college ESL composition courses. In my own teaching context, I found that my students demonstrated a similar level of engagement both in learning about their campus and in improving their writing and communication skills.

One unique aspect of ecocomposition is the way it theorizes the bidirectional relationship between writing and the world, as

Dobrin and Weisser (

2002) explain: “ecocomposition takes as one of its primary goals the desire to encourage students to consider the relationships between (written) language and the earth’s systems in which they must survive” (p. 131). Admittedly, my compare–contrast assignment might not fully actualize this goal since I did not explicitly present ecocomposition’s philosophy about the mutual relationship between the world and written discourses. Nevertheless, while students primarily used their writing to elucidate the historical significance and design of campus spaces, a number of students used the conclusions of their essays and presentations to press home the point that eco-friendly rhetoric embodied on campus should inspire us to pursue sustainability. These students thus appeared to understand the role that their own writing plays in promoting the sustainability awareness of their readers. In addition, a number of my students argued that their university is using these buildings as educational tools, especially since a variety of resources publicize the campus’ eco-friendly buildings, such as those with LEED certifications (

Pennsylvania State University n.d.b,

Stout et al. 2006). By considering the ethical messages sent on campus, students gained opportunities to see that these buildings also serve as models for designing future buildings—a topic that may in fact intersect with some of my students’ eventual career paths.

In addition to introducing concepts that can help students pursue sustainability in their own lives and careers, place-based ecocomposition assignments can make a positive impact on how students’ construct their identities. While learning about eco-friendly technology can raise students’ sense of global citizenship, perhaps the most significant impact is the way this assignment can enhance students’ sense of connection to their campus. Because of my students’ level of engagement and the emotions expressed in their essays and presentations, I believe this assignment has the potential to influence students’ sense of “bioregional identity.”

According to landscape architecture theorist

Thayer (

2003), a “bioregion” is a “unique region definable by natural (rather than political) boundaries with a geographic, climatic, hydrological, and ecological character capable of supporting unique human and nonhuman living communities” (p. 3).

Thayer (

2003) argues that developing a sense of bioregional identity promotes ethical thinking about how to live as a citizen of a particular locality, and that gaining a bioregional identity is essential for diverse communities to cooperate across ethnic and political boundaries to work toward a “mutually sustainable future for humans, other life-forms, and earthly systems” (p. 6). Place-based education can directly impact both teachers’ and students’ bioregional identities. For example, environmental educators such as

Leou and Kalaitsidaki (

2017) report that place-based programs in New York City have raised the local environmental awareness of teachers and students, thus enhancing their sense of ethical citizenship in the Hudson River watershed.

In applying the concept of bioregionalism to college composition,

Lindholdt (

2001) argues that addressing ecological identity “can reintegrate an estranged citizenry and help restore degraded ecosystems if applied in writing courses” (p. 244).

Owens (

2001b) similarly emphasizes that college composition instructors have a special responsibility to promote an ethic of sustainability because of their broad access to incoming students and because of the interdisciplinarity of college writing (p. 29). When teaching international and immigrant students who may have recently moved to a new country for their studies, I believe it is imperative to welcome these students as full citizens of the bioregion, in which all members share responsibility to cooperate for a more sustainable future. In an age of hypermobility, the campus space compare–contrast assignment offers students a concrete starting point for learning about how the local culture has been responding to various environmental challenges, such as reducing greenhouse emissions, reducing waste, and promoting local biodiversity.

5.3. Addressing Acculturation and Alienation through Place-Based Ecocomposition

The potential of place-based ecocomposition to impact students’ sense of responsibility and bioregional identity is especially relevant to international students and immigrants studying English in the U.S., who are in the process of negotiating their identities and adapting to a new local environment and culture. During their first year of college, domestic-born students often plug into campus life bringing prior knowledge about their college’s history and culture, but international students typically do not share this kind of background knowledge that is essential to forming a positive sense of student identity and belonging. Researchers have reported that international students often feel alienated from their new communities (

Du and Wei 2015;

Gu et al. 2010;

Yeh and Inose 2003). Research has also demonstrated that international students’ acculturation to a new study environment can be stressful, even leading to mental health struggles due to difficulty forming social networks, linguistic challenges, discrimination, and academic stressors (

Arias-Valenzuela et al. 2016;

Jung et al. 2007;

Yeh and Inose 2003;

Ying and Han 2006).

Jung et al. (

2007) define acculturation as “the process of cultural change resulting from contact with a different culture and the process of adapting,” and further explain that acculturation can in some cases result in a person turning away from his/her cultural background, but it can also result in students balancing aspects of their new and previous cultural identities (p. 609). Based on their research study on the acculturation and mental health of Chinese international students,

Du and Wei (

2015) argue that college staff and faculty in the U.S. can best serve international students by valuing “these students’ needs for connection with people from both U.S. society and their [own] ethnic communities” (p. 321).

Du and Wei (

2015) also recommend that college professors and staff increase opportunities for international students to learn about their host culture, as higher levels of acculturation are shown to be associated with higher levels of life satisfaction.

Jung et al. (

2007), citing

Birman (

1998), emphasize that during the acculturation process, international students with higher familiarity with the host country’s popular culture are often more likely to feel confident about communicating with members of the host culture. Based on a survey investigating the acculturation of international students in the hyperdiverse city of Montreal, Canada,

Arias-Valenzuela et al. (

2016) conclude that because students who reported the development of a local Montréalais identity also reported a relatively high level of satisfaction toward their new cultural group, universities should consider taking steps to encourage students to develop local identities in order to improve their overall acculturation experiences (p. 136).

Place-based writing assignments directly address some of the cultural needs of international students because learning about their campus is a concrete starting point for studying their host culture. In addition, the theme of sustainable design, as emphasized in the campus space compare–contrast assignment, provides students with opportunities to consider how the campus spaces they use on a daily basis are connected to the broader ecosystem in which we are all enmeshed. Place-based assignments are able to promote students’ affiliation with their community and bioregion (

Lindholdt 2001), and as literary critics

Lynch et al. (

2012) explain, a local bioregional identity can complement other foundations for identity, such as nationality or ethnicity (p. 4). Place-based ecocomposition assignments thus are not asking students to give up aspects of their cultural identities. Rather, I would argue that they are simply offering international and immigrant students opportunities to become more informed and engaged as members of their current bioregion. Bioregionalism emphasizes the commonality of space among inhabitants, despite linguistic, ethnic, and cultural differences, and thus place-based assignments have the potential to reduce students’ feelings of alienation regarding their new environment. Being invited to participate as an ethical citizen of their school or college is affirming for English language learners, who may initially feel alienated, and ecological content often appeals to students because they may already value sustainability due to their own cultural upbringings.

The place-based compare–contrast assignment also aims to foster students’ independence and agency to construct their own meanings for the places they choose to compare. After conducting an extensive two-year study of international students at four campuses in the U.K.,

Gu et al. (

2010) concluded that most of the students surveyed were able to adapt to their new study environment “not because of their dependence upon others, but the exercise of their own agency and resilience to achieve and succeed” (p. 18). This trend implies that support given by university staff to international students should ultimately build on the individual agency and resilience of students themselves. Place-based research assignments fulfill this criterion, as they require students to go out and interact independently with their environment.

6. Conclusions

This essay showcases the benefits of a compare–contrast essay and multimedia assignment that applies principles of place-based ecocomposition to a college ESL context. This assignment takes the common student activity of snapping photos of their school and transforms it into an opportunity for students to learn how to write in the compare–contrast genre, structure their texts, synthesize research, and practice academic speaking skills. In order to implement this assignment in ESL/EFL courses and intermediate/advanced language courses in secondary schools and colleges, instructors first need to conduct their own ground-level and online research on their school and community as a part of lesson planning. Instructors using this assignment can expect a number of benefits for students: the content is able to engage and motivate students to work on their writing and other language skills, the ecological emphasis can promote an ethic of sustainability, and the place-based research experience has the potential to improve the experience of international and immigrant students by increasing their sense of connection to their community at a time when they may be struggling with acculturative stress and alienation.

This essay also identifies a significant gap in research on the acculturation experiences of international students, as the role of bioregional identity has not been fully explored in the literature. In discussing the relative lack of research on environmental approaches to pedagogy and cultural studies,

Reynolds (

2004) states, “While race, class, and gender have long been viewed as the most significant markers of identity, geographic identity is often ignored or taken for granted. However, identities take root from particular sociogeographical intersections, reflecting where a person comes from” (p. 11). In addition to bringing unique bioregional identities into the classroom, students experience further influences on their bioregional identities due to living in a new school community. A critical skill for students in today’s hypermobile world is taking responsibility for their ecological impact when moving into a new environment, and place-based assignments can open both students’ and instructors’ minds to the unique environmental needs in their communities.

This kind of place-based approach can also be enlightening for instructors who are curious about students’ perspectives on their lived environments. In my experience implementing this place-based compare–contrast assignment over several semesters, students expressed a variety of positive emotions about their campus community, and many of them concluded that their campus sends a strong rhetorical message about the value of history, diversity, and sustainability. With its content-based approach, this assignment ultimately provides students with vocabulary and concepts for talking about sustainability in future academic, professional, and community contexts, thus empowering them to address the looming environmental issues of our world.