4. Reanalysis, Refunctionalization and Subjectivization of the Verb Form Habemos

As I have mentioned before, one of the changes experienced by haber was from being a transitive verb to an impersonal one. This change caused its paradigm to be reduced to the third-person singular although, by participating in compound tenses and in verbal periphrases as an auxiliary verb, it managed to keep its whole paradigm identical to the one it used to have as a transitive verb.

Once

habemos became an auxiliary verb, the first-person plural experienced a formal reduction. The change

avemos cantado >

hemos cantado (i.e., the phonetic reduction of the fourth person or the first-person plural of the perfect) has been carefully analysed in

Bustos Gisbert and Moreno Bernal (

1992) and, more recently, in

Rodríguez Molina (

2010,

2012).

Rodríguez Molina (

2012), based on

Girón Alconchel (

2004, p. 870), states that the alternation

hemos/habemos (

avemos) became less and less frequent once the transitive use of

haber was lost. The shortened form was a more effective iconic manifestation of its use as an auxiliary. According to Rodríguez Molina, the reduction started at the beginning of the 16th century and by the 18th century

habemos disappeared from the standard variant, although it has dialectal presence (cf.

Rodríguez Molina 2012, p. 181) and the data on which this work is based are consistent with this. From the first quarter of the 16th century, the long forms are obsolete and appear mainly in legal texts, pastoral poetry and stigmatized dialects (

Girón Alconchel 2004, p. 866).

The dialect variation is important in order to track the spread of change. Rodríguez Molina’s data (

Rodríguez Molina 2012, p. 207) suggest that the short form (

hemos cantado) emerges in Aragon and spreads from there. According to this author, the causes of change can be grouped as: (1) phonetic reduction after the grammaticalization of compound verb tenses; (2) essentially phonetic factors (the bilabial occlusive voiced sound loss in the intervocalic position and the syncope of the low central vowel); (3) an analogy process to preserve the reduction in the verbal paradigm.

4According to our results, reduction must have happened around the 16th century. The corde registers 98 cases of hemos used as an auxiliary verb in the 13th century, a number that increased in the following centuries and reached 4174 cases by the 16th century. Throughout this period, the frequency of habemos (avemos) and hemos as an auxiliary is similar but two centuries later, in the 18th century, the frequency of hemos is recorded at 2162—and increases to 13,000 in the 19th century and 16,503 in the 20th century. On the other hand, the frequency of habemos decreases; there were 81 recorded cases in the 18th century, 68 cases in the 19th century and there was a small rebound in the 20th century, when there were 145 recorded cases. These results seem significant to us.

Based on the results of

Table 1, we can state that

habemos was kept in relation to the possessive meaning and, residually, as an auxiliary verb. On the other hand,

hemos was generalized as the prototypical auxiliary verb (see the numbers in bold print in

Table 1).

Table 1 shows very different use frequencies for

habemos (

avemos) vs.

hemos as auxiliary verb forms in the 18th, 19th and 20th century. If one compares only the auxiliary meaning of these forms, as in

Table 2, it appears that

habemos (

avemos) is marginally used as an auxiliary verb as compared to

hemos.

Considering these results, it appears that habemos is also bound to disappear as an auxiliary verb form, especially during the 19th and 20th century, even if one considers its presence in some Spanish dialects. As a possessive verb, its situation is similar; during the 20th century it was used sporadically in fixed phrases like the ones in example (5a). It is clear that its use as an auxiliary or as a possessive verb form has no major relevance in terms of frequency. Habemos was registered in cases like the ones in example (5b), which, although recent, seem to be marginal.

| (5) a. | Y | cuánta | sabiduría | habemos menester | |

| | And | how much | wisdom | need-PRES1P | |

| | | | | | |

| | para | retener | nuestros | prisioneros | |

| | for | hold back-INF | POS-1P | prisoners | |

| | | | | | |

| | sin | destripar-los | | | |

| | without | gut.INF-ACUS3P | | | |

| | (Hace tiempos, 1935–1936, Colombia, corde, s.v. habemos menester) |

| | “And how much wisdom must we need in order to retain our prisoners without gutting them.” |

| | | | | | |

| | Si | de | todo | lo | que |

| | If | of | everything | PRON | REL-3S |

| | | | | | |

| | habemos menester | hubiese | copia | sobrada | |

| | need-PRES1P | thereisIPFV.SBJV | copy | extra | |

| | (Misión de la Universidad, 1930, Spain, corde, s.v. habemos menester) |

| | “If there were an extra copy of everything we need.” |

| b. | alguna vez | nos | habemos de | apartar | |

| | some time | ACU-1P | AUX-PRES1P | move away-INF | |

| | | | | | |

| | del | común y simple | modo | de | decir |

| | of.ART | common and simple | way | of | say |

| | (Poesía española. Ensayo de métodos y límites estilísticos, 1950, Spain, corde, s.v. habemos de apartar) |

| | “Some time we must have to move away from the common and simple way of saying.” |

| | | | | | |

| | mandar | matar | a | un hombre ordinario, | |

| | order-INF | kill-INF | to | a man ordinary | |

| | | | | | |

| | pone | a | un hombre | tan grande | en |

| | place-PRES3S | to | a man | so great | in |

| | | | | | |

| | el | estrecho | que | habemos | visto |

| | the | strait | that | AUX-PRES1P | seen-PTCP |

| | (Discurso de recepción en la Real Academia Española: Pasión y muerte del Conde de Villamediana, 1964, Spain, corde, s.v. habemos visto) |

| | “To order an ordinary man to be killed, places a great man in the situation that we have seen.” |

| | | | | | |

| | ya | sabéis | la | voluntad | que |

| | already | know-PRES2P | the | will | that |

| | | | | | |

| | la Católica Reina mi Señora, | é | yo | habemos | |

| | the My Lady the Catholic Queen | and | I | AUX-PRES1P | |

| | | | | | |

| | tenido | é | tenemos | al | bien |

| | had-PTP | and | have-PRES1P | to.ART | good |

| | (Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar, 1963, Cuba, corde, s.v. habemos tenido) |

| | “You know already what My Lady the Catholic Queen and I have willed to be correct.” |

Despite what we have previously said, the frequency of habemos grows in the 21st century, when the verb has an existential meaning, because, as is widely known, the agreement of haber in contemporary Spanish is a general and widely spread phenomenon, even though it is not always recorded in written form.

In my opinion, as stated in a previous study on

haber’s agreement (

Hernández Díaz 2005), it is necessary to make a distinction between the creation of two different kinds of agreement, for they depend on different semantic, and, more importantly, pragmatic reasons. I am referring to the contrast in example (6).

| (6) a. | Lo | más | enriquecedor | fue | cómo | |

| | The | most | enriching | be-PST3S | how | |

| | | | | | | |

| | contaban | las tradiciones | que | habían | | |

| | relate-IPFV3P | the traditions | that | there are-IPFV3P | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | en | sus | pueblos | | | |

| | in | POS-3P | hometown | | | |

| | (Manuscript, c. 2000, México) | |

| | “What was most enriching was how they told of the traditions that they had in their hometowns.” | |

| | | | | | | |

| | no | deben | haber | fueros | ni | |

| | not | AUX-PRES3P | be-INF | exemptions | nor | |

| | | | | | | |

| | privilegios | respect | e | este | problema | |

| | privileges | regarding | of | this | problem | |

| | (TV, México) | | | | | |

| | “There should not be neither exemptions nor privileges regarding this problem.” | |

| | | | | | | |

| | No | habían | copias, | entonces | reduje | |

| | Not | there be-IPFV3P | photocopies | so | reduce-PST1S | |

| | | | | | | |

| | los horarios | para | hacer-los | en | la | computadora |

| | the schedules | for | make.INF-ACUS3P | on | the | computer |

| | (Spoken language, México) |

| | “There were no copies, so I reduced the schedules in order to make them on the computer.” |

| b. | Habemos | muchos | aquí | que | somos | inocentes |

| | There be-PRES1P | many | here | that | be-PRES1P | innocent |

| | (Socialmention, 2015) |

| | “There are many of us here who are innocent.” |

| | | | | | | |

| | yo | sé | que | habemos | | |

| | I | know-PRES1S | that | there be-PRES1P | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | muchos | que nos | sentimentos | así | y | |

| | many | who | feel-PRES1P | like this | and | |

| | | | | | | |

| | no | tiene | nada | de | malo | |

| | not | have-PRES3S | nothing | about | wrong | |

| | (Socialmention, 2015) |

| | “I know that there are many of us who feel this way and there is nothing wrong about it.” |

| | | | | | | |

| | habemos | personas | que | por | fuera | |

| | there be-PRES1P | people | who | by | outsid | |

| | | | | | | |

| | aparentamos | y | fingimos | ser | humildes | |

| | pretend-PRES1P | and | feign-PRES1P | be-INF | humble | |

| | (Google, 2015) | | | | | |

| | “There are many people of us who on the outside pretend and feign to be humble people.” |

In both (6a) and (6b), the reanalysis of the element governed by the existential verb

haber, as the subject of the sentence, is evident. This mechanism was defined as follows:

The change in the structure of an expression or kind of expression, which is not related to any immediate or essential modification in its superficial expression.

As different authors have stated (

Company 2010;

García 1990;

Narrog 2007), a reanalysis might or might not have repercussions in formal expression but will definitely have repercussions on a conceptual level. Reanalysis is completed, in cases like example (6), because it has happened at an internal and external level of expression and because of the way in which it manifests itself or becomes updated in the agreement.

As we know, reanalysis is a major mechanism for grammaticalization and for linguistic change in general, mainly because it is a prerequisite for the implementation of change through analogy: a process that modifies shallow evidences and that spreads reanalysis’ effects not only within the same linguistic system but also inside the speaking community. The analogy that caused the grammatical uses I am interested in was the intransitive mono-argument constructions’ formal structure, because whenever a predicate has only one argument, it will prototypically be the subject of the sentence. The first example in (6a) shows a very evident analogy because the existential verb habían is coordinated with existían, which makes the two sentences look syntactically equal in the eyes of the speaker.

The development of agreement in

habemos is a case of refunctionalization, except for the one exhibited in (6a), because it does not only imply the reanalysis of an existing entity as the sentence’s subject but also the reuse of what is almost a junk form or a very marginal one in standard Spanish, as we have seen. Based on the results shown in

Table 1, we can attest that the rotation of

habemos and

hemos seems to have been related, at some point, to the former’s possessive value and that, once it lost this value,

habemos was occasionally kept as an auxiliary verb. Keeping both forms, then, turned out to be unnecessary. Therefore,

habemos became a morphological archaic case of

hemos but in terms of system and frequency the former was practically considered to be ‘junk.’ According to

Lass (

1988, p. 36), there are only three outcomes for a residual expression: (1) complete loss; (2) remaining as waste without a specific function; or (3) remaining and being systematically used for another purpose, instead of being left aside. The third option is defined by Lass as exaptation and, according to the results in

Table 3, that is precisely what happened to

habemos.Even though grammarians in the 19th century identify the use of habemos with the meaning ‘existir’ (‘to exist’) as a mistaken agreement, results show that during the 20th and 21st century exaptation was the solution for habemos. This verb form was marginally used as an auxiliary or with a possessive meaning during the 19th and 20th centuries. However, during the 20th century and during the first fourteen years of the 21st century, it regained strength not only to express existence—for habemos with existential meaning does not merely mean that algo está o existe en alguna parte (‘something is or exists somewhere’)—but also as the verb form that allows the speaker to include himself as member of a group or class. Such a group exhibits a clear set of characteristics and is located inside space and time coordinates—real and metaphorical—as is shown in example (7). Thus, the recovery of habemos involved its refunctionalization, through subjectivization, as well. Moreover, since habemos, unlike other impersonal existential verb forms, was reused as an existential verb with the option to indicate the grammatical person, in some way, it might be seen as an exaptation process.

| (7) | De | hecho, | habemos | un | equipo | grande | | |

| | In | fact, | there be-PRES1P | a | team | big | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | que | seguimos | trabajando | en | ello | | | |

| | that | AUX-PRES1P | working-gerund | on | it | | | |

| | (Socialmention 2015) | | |

| | “In fact, we are a large team that continues to work on it.” | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | No generalizo | que | todos | somos | | | | |

| | Not generalize-PRES1S | that | everybody | be-PRES1P | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | asi (sic) | y | se (sic) | que | habemos | | | |

| | like that | and | know-PRES1S | that | there be-PRES1P | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | personas | que | estamos | orgullosos | de | quienes | somos! |

| | people | that | be-PRES1P | proud | of | who | be- PRES1P |

| | (Socialmention, 2015) | |

| | I do not generalize that we all are like this and I know that we are people who are proud of who we are.” | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | Con respecto | al | trato | que | se | | | |

| | Regarding | to.ART | treatment | that | IMPER | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | les | da | a | las personas | creo | | | |

| | DAT-3P | give-PRE3S | to | the people | believe-PRES1S | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | que | no | es | muy bueno, | ya que | | | |

| | that | not | be-PRES3S | very good, | because | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | habemos | personas | muy | ignorantes | y | | | |

| | therebePRES1P | people | very | ignorant | and | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | que | nos | consideramos | con | mucha | | | |

| | that | AUX-1P | consider-PRES1P | with | so much | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | suerte | como | para | no | tener | ese | tipo | de enfermedad |

| | lucky | as | | not | have-INF | that | kind of | illness |

| | (Google, 2015) |

| | “Regarding the treatment that has been given to people, I think that it is not such a good thing, because we are very ignorant people and we consider ourselves lucky for not having that kind of illness.” |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | y | si (sic) | habemos | personas | que | | | |

| | and | yes | there be-PRES1P | people | that | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | somos | como | somos | de | nacimiento | | | |

| | be-PRES1P | like | be-PRES1P | of | birth | | | |

| | | | | | | | | |

| | y | no | podremos | cambiar | | | | |

| | and | not | can-FUT1P | change-INF | | | | |

| | (Google, 2015) |

| | “And, indeed, we are people who we are from birth and we won’t be able to change.” |

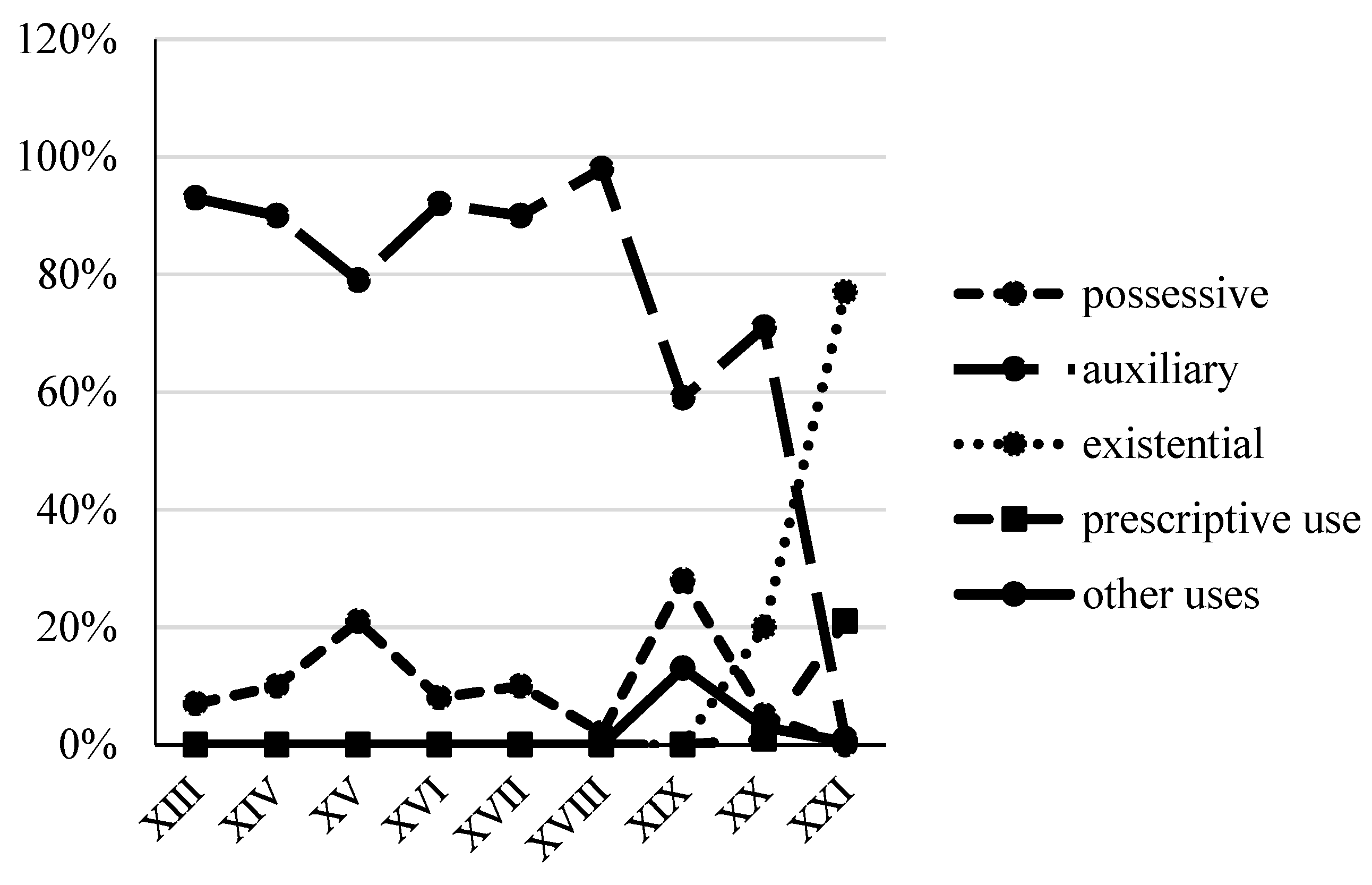

Going back to the results of

Table 3, I deem it necessary to explain the two far right columns: ‘prescriptive use’ and ‘other use.’ The former attracts my interest because, in Google, these cases equal 34%, that is, 55 of the 160 first reported examples. I decided to classify them as ‘prescriptive use’ because they are, in a sense, an expansion of suggestions by grammar books to avoid agreement between the verb

haber and a mono-argument noun phrase. These results refer to articles, pages, blogs or chats that describe this agreement as incorrect and they censure it. This shows a genuine interest in the subject, as well as the frequency of the phenomenon, for we can assume that prescription occurs as often as there is a violation of a rule. Then, to the far right, the ‘other use’ column gathers fixed phrases where

haber is used with possessive meaning but it does not make any sense to classify them as truly transitive uses. Taking this into account, the refunctionalization of the verb form

habemos seems to be almost complete.

Figure 1 shows the refunctionalization of

habemos diachronically.

There is no doubt that the refunctionalization of habemos may be explained as a change through subjectivization, because grammatical alternatives, which are reduced to formal options dissociated from meaning in some theories, are studied in change theories as carriers of meaning. Such meaning is defined by different perception forms in a situation, rather than by different objective or fact conditions. Exposing the figurative condition of language allows us to approach rotation as part of the common pragmatic meaning of language, where we can see that change in shape also implies change in meaning.

Having observed an increasing tendency in correcting the agreement of habemos, we could ask ourselves why there is insistence on exaptation. The answer lies in the hypothesis ‘change in shape implies change in meaning’ because, subjectively, the advantage of habemos over hay or even over other verbs that can give constructions an existential sense, is that the speaker is able to include himself in the referred event as a directly affected member of the situation. It is worth mentioning that existential sentences with habemos in the corpus usually refer to events where the speaker, as part of the subject, plays the part of ‘theme.’ A theme that is somehow affected by the described situation, because sentences include theme as being part of a class with specific circumstances, frequently deemed negative (for example signs of vulnerability), as shown in italics in (8).

| (8) | habemos | personas | que | le | | |

| | there be-PRES1P | people | who | DAT-3S | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | damos | fiebre | a | la | calentura | |

| | give-PRES1P | fever | to | the | temperatura | |

| | (Doña Bárbara, 1929, Venezuela, CORDE, s.v. habemos personas) |

| | “There are those of us who give fever to fever.” |

| | | | | | | |

| | hay, | habemos | todavía | | | |

| | there be-PRES3S | there be-PRES1P | still | | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | militares | pundonorosos, | para | defender | | |

| | militaries | honorable | for | defend-INF | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | los intereses | del | pueblo | y | de la | Patria! |

| | the interests | of.ART | people | and | of the | homeland |

| | (El Papa verde, 1954, Guatemala, corde, s.v. habemos) |

| | “There are still honorable men, including me, to defend the interests of the people and of the homeland.” |

| | | | | | | |

| | habemos | maestros | que | tienen (sic) | 25años | de enseñanza |

| | there be-PRES1P | teachers | who | have-PRES3P | twenty-five years | of teaching |

| | (Proceso, 1997, México, CREA, s.v. habemos) |

| | “There are those of us teachers that have been teaching for 25 years.” |

| | | | | | | |

| | habemos | muchos | venezolanos | que | | |

| | There be-PRES1P | many | Venezuelans | who | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | estamo | inocentes | de | todo | estos | males |

| | be-PRES1P | innocent | of | all | these | misfortunes |

| | (Socialmention, 2015) |

| | “There are many of us Venezuelans who are innocent of all these misfortunes.” |

| | | | | | | |

| | habemos | miles | de | profesionales | | |

| | There be-PRES1P | thousands | of | profesionales | | |

| | | | | | | |

| | en | este sector | que | aunque | mal | pagados, |

| | in | this sector | that | even | bad | payed-PTCP |

| | | | | | | |

| | exprimidos | por | los | empresarios | y | |

| | used-PTCP | by | the | enterprise people | and | |

| | | | | | | |

| | con | convenios caducados | tenemos | un | trabajo | |

| | with | agreements expired | have-PRES1P | a | job | |

| | (Socialmention, 2015) |

| | “There are thousands of us professionals in this sector that though poorly payed, exploited by the businessmen with bad contracts, we still have a job.” |

Thus, the refunctionalization of habemos is another way in which the Spanish expresses a change of mood within the syntactic subject. This is the reason why, even though the phenomenon is constantly condemned, its presence is a fact, due to the communicative advantages it has in pragmatics.

The cooptation of habemos to mean the ‘existence of a class to which the speaker belongs or includes himself’ is possible thanks to the personal inflectional morpheme. As we know, recycling of the form may be or may not directly related to its former or original use or can be used marginally. For habemos, we consider it is the second case because the marginal relationship lies in the personal form of the verb but it is not related to its previous possessive value. It is related to an existential value it rarely had in Latin and which increased in Old Spanish. The recycling and recovery of habemos to include the speaker as part of the subject is overwhelming, if we consider the most frequent combinations of habemos. In accordance with Google web browser results, in frequency order they are as follows: habemos personas que… (‘There are those of us people that…’) (393,000 cases), habemos gente que… (‘There are those of us that…’) (389,000), habemos algunos que… (‘There are some of us people that…’) (305,000), habemos algunas que… (‘There are some of us women that…’) (229,000), habemos quienes… (‘There are those of us who…’) (225,000 cases), habemos hombres que… (‘There are those of us that…’) (221,000), habemos mujeres que… (‘There are those of us women that…’) (219,000), habemos muchos que… (‘There are many of us that…’) (174,000 cases).

In approaching the end of this analysis, I would like to make it clear that my approach to haber has been a many-angled diachronic one, inserted in grammaticalization and reanalysis theory. I would also like to add that I did not find those theories useful in explaining refunctionalization regarding the development of agreement or the special case of habemos, because we are not dealing with a gradual one-way phenomenon in Spanish language history. It is surprisingly odd, within these theories, to find a practically useless obsolete word regaining expressive strength. However, under light shed by refunctionalization and by subjectivization, as an exaptation case, the change turns out to be natural and transparent. Thus, I consider that the development of agreement in haber, specifically in habemos, can be partially explained from on the grounds of grammaticalization. I also consider that both grammaticalization and exaptation allow us to explain a sudden phenomenon that neither has a unidirectional behaviour, nor ends in a grammatical or more grammatical form than the one at the beginning. It is a phenomenon with a form that reinserts itself, inside the verbal paradigm by building a new paradigm, through reanalysis and refunctionalization, due to subjective and pragmatic value assessment.