Abstract

The role native language transfer plays in L2 acquisition raises the question of whether L1 constitutes a permanent representational deficit to mastery of the L2 morphosyntax and prosody or if it can eventually be overcome. Earlier research has shown that beginning and low intermediate Anglophone L2 French learners are insensitive to French morphosyntactic and prosodic constraints in using in situ pronouns transferred from the L1. The prosodic transfer hypothesis (PTH) proposes that native prosodic structures may be adapted to facilitate acquisition of L2 prosodic structure. Our study presents new evidence from three Anglophone advanced learners of L2 French that indicates ceiling performance for pronoun production (99% accuracy in 300 tokens over nine interviews) and grammaticality judgment (98% accuracy). This native-like performance demonstrates target French morphosyntax and prosody, built—as predicted by the PTH—by licensing pronominal free clitics in a new pre-verbal L2 position distinct from post-verbal L1. Furthermore, the learners’ data confirms accurate prosody by way of appropriate prominence patterns in clitic + host sequences, correct use of clitics with prefixed verbs, use of stacked pronouns, as well as correct prosodic alternations involving liaison and elision. These results counter impaired representation approaches and suggest early missing inflection may be overcome.

1. Introduction

The role of the native language in L2 acquisition has been a topic of inquiry for decades (e.g., Lado 1957; Schwartz and Sprouse 1996) and is of particular interest in cases where the two languages differ in several dimensions. This notion of transfer raises the question of whether the native language constitutes a permanent representational deficit to mastery of the new morphosyntax (Hawkins and Chan 1997; Tsimpli and Dimitrakopoulou 2007) or if it can eventually be overcome (Lardiere 2007; Rothman 2011). In the arena of prosody, one proposal concerning native language influence is the prosodic transfer hypothesis (PTH, Goad and White 2006, 2008, 2009), which argues that learners’ native language prosodic structures may be used to accommodate L2 functional material.

The acquisition of French pronouns is a challenge for Anglophone second language (L2) learners, since the two languages differ morphosyntactically and prosodically for object pronouns.

| 1. | a. | I see John | ||||||

| b. | I see him | |||||||

| c. | *I him see | |||||||

| d. | I see’m | |||||||

| 2. | a. | Je vois Jean | ||||||

| b. | Je le vois | |||||||

| c. | *Je vois le | |||||||

In terms of morphosyntax, English pronouns are located in the canonical object position of the full noun phrase (1a, b) and may optionally be right-cliticized to the verb (1d). In contrast, French object pronoun clitics are left-adjoined to the inflected verb (2b), and are not in the canonical direct object position (2a, c). The acquisition of L2 Romance pronouns has been a subject of investigation to test morphosyntactic transfer hypotheses (White 1996; Hawkins and Franceschina 2004; Granfeldt and Schlyter 2004; Arche and Domínguez 2011) in studies that indicate that mastery of clitic pronouns varies substantially according to proficiency level.1 Beginning learners of L2 French clearly transfer English structures in producing in situ pronouns as in (2c) (Herschensohn 2000; Hawkins 2001), while intermediate proficiency learners show transitional responses, both behavioral and cortical, to ungrammatical in situ pronouns (Sneed German et al. 2015). Little research has been done on advanced learners of L2 French with respect to object clitic pronouns.2

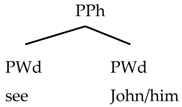

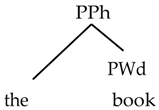

Nor have object clitics been examined with respect to the prosodic transfer hypothesis. In terms of prosodic structure, English nouns and pronouns and French nouns constitute independent prosodic words, whereas French object pronouns constitute free clitics attached to the left of the verb, so that the prosodic structure of (2b) is as shown in (3c), where the clitic is attached as a sister to the prosodic word (PWd) and a daughter to the prosodic phrase (PPh) (Goad and Buckley 2006). English pronouns, normally independent prosodic words, may also cliticize, but as right-branching affixal clitics, so that the prosodic structures of (1a/b) and (1d) are as shown in (3a) and (3b) (Selkirk 1996).

| 3. | English | ||||

| a. | |||||

| |||||

| b. | |||||

| |||||

| French | |||||

| c. | |||||

| |||||

The French clitic is both directionally (left, not right) and prosodically (free, not affixed) distinct from the English pronominal clitic. In their nominal morphosyntax, however, both languages share a similar prosodic free clitic structure, that of the leftward article plus noun as in (4).

| 4. | French/English | |

| ||

The availability of this structure is interesting, given the PTH’s proposal that target L2 prosody can be built when L1 structures are licensed in new positions (“minimal adaptation”, Goad and White 2004).

In this article, we explore implications of the PTH for Anglophone acquisition of L2 French clitics by examining new data from advanced learners with extensive experience in the target environment. The first background section describes French and English pronouns (Section 2.1), prosodic structure and the prosodic transfer hypothesis (Section 2.2), and previous research on the L2 acquisition of French clitics (Section 2.3), which leads to our research questions for advanced learners (Section 2.4). The next sections present new evidence from advanced learners of L2 French (participants and methodology described in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2, respectively), coming from three case studies that include data on production and grammaticality judgments (results presented in Section 3.3). We discuss the new evidence in light of the PTH (Section 4), arguing that the data support the hypothesis in demonstrating the learners’ shift to L2 French prosody. Our analysis adopts the concept of minimal adaptation of native prosodic structures to accommodate L2 functional material. We close with some brief concluding remarks (Section 5).

2. Background

2.1. French and English Object Pronouns

Cross-linguistically, pronouns fall into strong, weak and clitic classes (Cardinaletti and Starke 1999). Strong pronouns project the most complex syntactic, semantic and phonological structure, followed by weak pronouns and finally by clitics.3 French pronouns include parallel sets of strong and clitic pronouns in six persons, while English pronouns are strong unless cliticized to the verb as in (1d) (Table 1).4

Table 1.

Pronouns of English and French.

Strong pronouns in French and English are phonetically free standing and fully referential, whereas clitics in French are morphosemantically minimal (person, gender and number features) and structurally deficient, requiring phonological attachment to a host. Strong pronouns act like full determiner phrases (DPs) in French in that they are syntactically mobile and phonologically stressed. They, but not clitic pronouns, can appear in coordination (5), in isolation (6) and in prepositional phrases (7). They are quite frequent in left and right dislocation (8) and are usually animate/ human.

| 5. | Elle | et le prochain, | je | les | ai écoutés. |

| *La | et le prochain, | je | les | ai écoutés. | |

| ‘Her and the next one, I listened to them.’ | |||||

| 6. | Qui a-t-il aidé? | |||

| ‘Who did he help?’ | ||||

| Lui/Toi/Elles | ||||

| ‘him/you/them.’ | ||||

| *Le/*Te/*Les | ||||

| ‘him/you/them.’ | ||||

| 7. | Toi | seul | va | au cínema | avec lui. |

| *Tu | seul | va | au cínema | avec le. | |

| ‘You alone go to the movies with him.’ | |||||

| 8. | Moi, | je trouve | qu’il est stupide |

| *Me, | je trouve | qu’il est stupide | |

| ‘Me, I think he’s stupid.’ | |||

In contrast, clitic pronouns are unstressed, may not remain in situ, and refer to both animate and inanimate referents. Roberts (2010, p. 41) analyzes French clitics as “simultaneoulsy maximal and minimal elements”, bundles of features (number, gender, person, case) in the head D of the Determiner Phrase in which they occur, whose defective nature requires cliticization to an inflected verb or infinitive. English strong pronouns resemble French ones in syntactic distribution and stress, as the translations indicate. The clitic forms differ between English and French, however, in terms of placement, morphological variation, feature specification, as well as prosody, as outlined in the next section.

To be able to use pronouns, Anglophone learners need to master the implicit knowledge that French object pronouns must be placed in non-canonical position to the left of the verb; that strong and weak pronouns are in syntactic complementary distribution (nominative and objective obligatory clitic); that French pronouns are marked for person, number and gender (as English), but that gender is grammatical, not semantic (and thus applies to every inanimate noun as well as animate). Learners also need to prosodically integrate object pronouns in a way compatible with L2 target structures.

2.2. Prosodic Structure

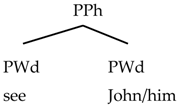

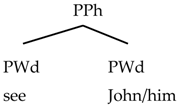

Which prosodic representations accommodate object pronouns in English and French? English object pronouns are typically realized as full prosodic words (9a), but may cliticize as right-branching affixal clitics (9b) (Selkirk 1996).

When an object pronoun in English is realized as a full prosodic word (9a), it attaches as a PWd sister to the verb, itself a PWd, with both of these linking to a phonological phrase node. A different structure is projected under phonological reduction of the pronoun. In this case (9b), failing to project its own PWd node, the pronoun is instead incorporated into an embedded prosodic word structure as a structurally deficient sister to the PWd verb.

| 9. | Prosodic structure of English object pronouns | ||

| a. | b. | ||

|  | ||

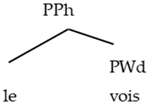

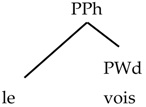

In French, on the other hand, (as for all “morphologically-free functional items [in French] which precede their host” (Goad and Buckley 2006, p. 114)), object pronouns are prosodically left-branching free clitics (10).

| 10. | Prosodic structure of French object pronouns | |

| ||

The free clitic—which can be separated from its host by other elements—differs from its affixal counterpart by its direct relation to the PPh: “the function word is sister to PWd and daughter to phonological phrase” (Selkirk 1996). The English affixal clitic cannot be separated from its host (11), whereas the French free clitic can, as we see in examples involving clitic stacking in Tense Phrases (12).

| 11. | a. | I saw’m | ||

| b. | *I saw’m’n’er | [I saw him and her] | ||

| 12. | a. | J’ai | offert | le cadeau | ||||||||

| I have | offered | the-M gift | ||||||||||

| ‘I offered the gift.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | Je | ne | l‘ai | pas | offert | |||||||

| I | NEG | have | NEG | offered | ||||||||

| ‘I didn’t offer it.’ | ||||||||||||

| c. | Je | ne | le | lui | ai | pas | offert | |||||

| I | NEG | it | to him | have | NEG | offered | ||||||

| ‘I didn’t offer it to him.’ | ||||||||||||

In (12a) the subject clitic je ‘I’ (which elides before the vowel-initial auxiliary) is attached to the inflected verb; in (12b, c) it is separated from the verb by additional pronominal and negative clitics that can intervene. French prosodic alternations include elision of vowels before following vowels and liaison of final consonants in function words when they precede vowel-initial content words/PWds. The nominal and verbal structures in which liaison and elision occur are the PPh, which may be iterated (Buckley 2005). Acquisition of French prosody is partially diagnosed by the learner’s use of these prosodic alternations.

With respect to the free clitic structure in French, it is noteworthy that it is one which occurs in English, albeit in a different context—in article + noun sequences. In other words, English articles are, like French object pronouns, prosodically left-branching free clitics (13). Note that in both English and French, other elements may be inserted (e.g., adjectives) between the free clitic article and the head noun in the DP, just as clitics may be stacked before the verb in the TP. It is well known that articles are acquired before object clitics in L1A and L2A (Prévost 2009; Paradis et al. 2014).

| 13. | Prosodic structure of English articles | |

| ||

According to the prosodic transfer hypothesis (Goad et al. 2003; Goad and White 2006, 2008, 2009), learners have difficulty with L2 prosody distinct from L1. Goad and White (2004, 2006, 2008, 2009) and Goad et al. (2003) study L1 Mandarin and L1 Turkish learners of L2 English to test the PTH with respect to distinctive L2 prosodic structures in the past tense (Mandarin does not mark tense and does not allow affixal prosody) and articles (neither Mandarin nor Turkish have articles and do not allow free affixes-left). The series of articles suggests that learners accommodate the L2 English prosodic structures either by omission (of tense or article) or by adapting an L1 prosodic realization. For example, some of the L1 Turkish participants (Goad and White 2009) used an L1-licit prosodic structure of a stressed article in L2 English (even when L2 stressing was not appropriate). This tendency is confirmed by Snape and Kupisch (2010) in their phonetic analysis (using Praat software, www.praat.org) of an L1 Turkish L2 English learner’s article production in which she overused stressed articles.

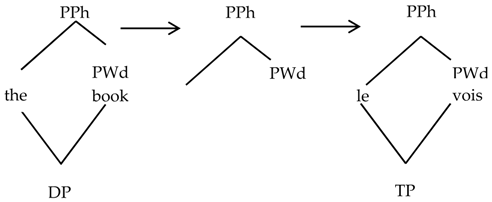

We have seen that English pronouns vary in prosodic realization between prosodic words and affixal clitics-right, whereas French consistently requires object pronouns to be free clitics-left. The two languages differ, therefore, not only in the directionality of object clitic placement (driven by morphosyntax) but also in their prosodic structure (affixal vs. free clitics). The PTH offers a means by which a distinct new L2 prosodic structure might be built by licensing L1 structures in new positions (“minimal adaptation”, Goad and White 2004). Goad and White (2009, p. 9) point out two conditions for minimal adaptation: “(a) when they [structures] can be built through combining pre-existing (L1) licensing relations; or (b) when they involve L1 structures being licensed in new positions.” Given the availability to our learners of the left-branching free clitic structure in (13), we assume that minimal adaptation in this case would involve the extension of the L1 free clitic-left structure for nominal DP morphosyntax, to verbal TP configurations. This process is illustrated in (14).

| 14. | Minimal adaptation in the L2 acquisition of object clitics |

| |

The possible prosodic transfer illustrated in (14) is similar to the one discussed in Goad and White (2009), which involved some of the L1 Turkish participants’ inappropriate use of a stressed article prosodic structure in their L2 English, except that in the case at hand the prosodic transfer would be facilitative.5

2.3. L2A of Clitics

This section reviews previous research on the L2 acquisition of French clitic pronouns, and then looks at investigations of prosodic structure, mainly of English determiners. Over the past 40 years, there have been several studies of French pronouns, indicating that beginning learners of L2 French manifest four types of pronoun realizations: in situ placement of strong and clitic pronouns (15), use of null pronouns (16), past participle cliticization (17) and correct left clitic placement (Herschensohn 2000; Hawkins 2001; Granfeldt and Schlyter 2004; Herschensohn 2004; Prévost 2009).6

| 15. | In situ | ||||||||

| a. | J’ai | vu | elle | (= je | l‘ | ai vue) | (Herschensohn 2004) | ||

| I have | seen | her-STG | (I | her-CL | have seen) | ||||

| ‘I saw her.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Il | veut | les | encore | (= les | veut) | (Selinker et al. 1975) | ||

| He | wants | them-CL | still | (= them-CL | wants | ||||

| ‘He wants them still.’ | |||||||||

| 16. | Null pronoun | ||||||||

| a. | T‘ | as placé [e] | sur le lit | (= tu l’as placé) | (Herschensohn 2004) | ||||

| You-SG | have placed | on the-M bed | (= you-SG it have placed) | ||||||

| ‘You put it on the bed.’ | |||||||||

| b. | J‘ai | mangé [e] | (= je l’ai mangé) | (Adiv 1984 ) | |||||

| I have | eaten | (= I it have eaten) | |||||||

| ‘I ate it.’ | |||||||||

| 17. | Past participle | ||||||||

| a. | Vous | avez | la | pris | (= vous l’avez pris) | (Herschensohn 2004) | |||

| You-PL | have | it-F | taken | (= you-PL it have taken) | |||||

| ‘You have taken it.’ | |||||||||

| b. | J’ai | le | vu | (= je l’ai vu) | (Granfeldt and Schlyter 2004) | ||||

| I have | it-M | seen | (I it have seen) | ||||||

| ‘I saw it.’ | |||||||||

The most prevalent errors in early interlanguage are the use of null pronouns (16)—similar to that of children acquiring French as an L1 (Hamann 2004; Hulk 2004; Paradis et al. 2014)—and in situ pronouns (15). Paradis et al. (2014, p. 170) note for L1A “regarding incorrect structures, over 90% were omitted objects”. In situ French pronouns reflect native language transfer of English morphsyntactic structure, while null objects could represent a well-documented tendency to missing inflection and missing functional items (Prévost and White 2000; Lardiere 2007; Arche and Domínguez 2011). As learners advance in proficiency they show more native-like command of pronouns (Arche and Domínguez 2011; Cuza et al. 2013; Grüter and Crago 2012; Sneed German et al. 2015).

Acquisition of L2 Romance pronouns has been a subject of investigation to test morphosyntactic transfer hypotheses (Granfeldt 2005; Granfeldt and Schlyter 2004; Arche and Domínguez 2011). Impaired representation approaches (Snape et al. 2009) assume that adult learners will have persistent difficulties mastering grammatical (uninterpretable) features of an L2, and that the syntactic deficit will be represented by persistent morphosyntactic errors. In contrast, missing inflection approaches (Prévost and White 2000; Lardiere 2007) attribute morphological errors to other problems such as processing overload or prosodic difficulties. In any case, evidence from earlier studies indicates that mastery varies according to proficiency level: beginning learners of L2 French transfer from English in producing in situ pronouns, whereas intermediate learners show transitional responses, both behavioral and cortical, to ungrammatical in situ pronouns (Sneed German et al. 2015).

Sneed German et al. (2015) use both behavioral measures and event related potentials (ERPs) to investigate comprehension of object clitics by two groups of intermediate Anglophone learners of L2 French and native speakers. Event related potentials, which record electrophysiological cortical activity using scalp electrodes, have been used to determine reactions to language phenomena in real time, with temporal resolution to the millisecond (Friederici et al. 1993; Hagoort and Brown 1999; Osterhout et al. 2004, 2006; Steinhauer 2014). Lexico-semantic and morpho-syntactic anomalies reliably elicit two distinct native responses, the N400 and the P600 respectively.7 For example, sentence (18b), would elicit a negative trending electrophysiological wave 400 ms after the event of interest (cream vs. batteries), compared to (18a).

| 18. | a. | I drink my tea with cream | ||

| b. | I drink my tea with batteries | |||

In contrast, (19b) would elicit a positive going wave 600 ms after the area of interest compared to (19a).

| 19. | a. | I drink my tea with cream | ||

| b. | I drinks my tea with cream | |||

Event related potentials research with L2 learners has documented mixed results, with beginners usually insensitive to violations, but showing increasingly native-like cortical responses with greater proficiency (Foucart 2008; McLaughlin et al. 2010; Tanner et al. 2013).

Given extensive production data documenting Anglophone in situ L2 French pronouns, Sneed German et al. (Sneed German et al. 2015) tested reactions to ungrammatical in situ strong and clitic pronouns (20a, b), as well as grammatical sentences (20c) that serve as a baseline.8

| 20. | a. | Après | le | match | elle | a rencontré | *le./ *les | dans | la | rue |

| After | the-M | match | she | has met | him-CL/them-CL | in | the-F | street | ||

| ‘After the match she met him/them in the street.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Après | le | match | elle | a rencontré | *lui/ *eux | dans | la | rue | |

| After | the-M | match | she | has met | him-STG/ them-STG | in | the-F | street | ||

| ‘After the match she met him/them in the street.’ | ||||||||||

| c. | Après | le | match | elle | l’a/les a | rencontré(s) | dans | la | rue | |

| After | the-M | match | she | him-CL/them-CL | has met | in | the | street | ||

| ‘After the match she met him/ them in the street.’ | ||||||||||

From a prosodic perspective, strong pronouns are licit in a stressed PWd position (20b), but they are morphosyntactically ungrammatical. In contrast, the in situ clitics (20a) are both morphosyntacitcally and prosodically illicit. Participants did two behavioral tasks (grammaticality judgments and general proficiency) and their cortical reactions were measured. The native French speakers showed predictable behavioral results (near ceiling accuracy) and a robust P600 to ungrammatical in situ pronouns, both strong and clitic. The high-intermediates’ results were qualitatively similar in behavioral and ERP responses to natives and significantly better than low-intermediates. In contrast, the low-intermediates’ results on the behavioral grammaticality judgments (GJ) task showed chance judgement of in situ clitics, (rejected 49% of the time), while ungrammatical strong pronouns were dismissed only 23% of the time, suggesting that low-intermediates are not sensitive to the ungrammaticality of these constructions.9

An important inference for further investigation concerns the response distinction between strong and clitic pronouns for the two groups of intermediates. Recall that the English pronoun system uses strong pronouns as the default and differs in morphosyntactic form and word order from the French system, in which object pronouns may only be clitic. Both groups of intermediates showed higher accuracy and more French-like cortical responses to the clitic violations than the strong pronouns. The less proficient group persists in their acceptance of prosodically licit strong pronouns, while showing an emerging implicit understanding of object clitics; one might conclude that while still apparently using their L1 English settings for pronoun placement, their cortical response demonstrates emerging sensitivity to French prosody. In particular, learners may be demonstrating sensitivity to the apparent prosodic deficiency of the clitic pronouns in L2 input. This in turn may be part of a general emerging sensitivity to French schwa (the vowel of highly frequent object clitics me, te, and le). If this is the case, part of leaners’ higher intolerance for the clitic pronoun in situ results from an emergent awareness that the schwa vowel is incompatible with a prominent position. This may facilitate the acquisition of morphosyntax, while not necessarily driving it.

The more proficient group, while showing some residual behavioral acceptance of strong pronouns, already were approaching the French natives in their responses to the ungrammatical in situ clitics. The research cited earlier on beginning and intermediate Anglophone learners of L2 French provides evidence that beginners and low intermediates transfer native pronoun word order, but with increasing proficiency, learners are able to gain mastery of L2 French morphosyntax, as indicated by comprehension, production and cortical measures. We infer that L2 learners can acquire features and word order different from the L1 system, but need to further investigate prosody.

2.4. Research Questions for Advanced Learners

Turning now to a proficiency level that has been less explored, that of advanced L2 French, we are led to the following research questions. Recall the prosodic structures involved in French and English clitic constructions ((9) is repeated here):

| 9. | Prosodic structure of English object pronouns | ||

|  | ||

English full pronouns are PWds under PPh, whereas their reduced clitic forms are affixal clitics right-attached to the PWd verb. In the early stages of L2A, the in situ pronouns that have been observed in production can be analyzed prosodically as PWd, as in (9a). There is no phonological evidence (phonological reduction or prosodic weakness) to suggest an affixal clitic (9b) analysis. In contrast, French object clitics are left free clitics under PPh, just as French and English articles are.

Beginning L2 French learners persist in Anglophone transfer with in situ placement; intermediate learners appear to gain prosodic sensitivity, distinguishing licit strong pronouns in situ from illicit clitics. We investigate advanced learners of L2 French pronouns to determine if they have adapted their object clitics to a French-like prosodic representation of left free clitics (left sister to PWd, daughter of PPh), or if they persist in using an English-like PWd structure (right sister to PWd). We pose the following research questions.

Research questions (RQs)

In order to determine that advanced learners have adapted to French prosody in their comprehension and production of pronominal clitics, we will need to prove that they are not using the English-like representations in (9).10 A lack of prosodic prominence on object clitics (RQ2) will rule out a PWd analysis, while clitic “stacking” (RQ3) will constitute evidence against an affixal clitic analysis. The production of clitics before verbs with prefixes will constitute further evidence against an affixal analysis (RQ4) (Buckley 2005, p. 127, citing Hannahs (1995)). We pose the following research questions.

- RQ1.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French show any evidence of prosodic transfer in their comprehension (grammaticality judgments) or production (morphosyntax) of object pronouns?

- RQ2.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French produce object pronouns with any prosodic prominence?

- RQ3.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French produce object pronouns in “stacked” sequences?

- RQ4.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French produce object pronouns before verbs with prefixes?

3. New Evidence from Advanced Learners

In this section we present L2 French data on production and GJ drawn from oral interviews with Chloe (age of acquisition onset 13), Eleanor (age of onset 17) and Max (age of onset 48), all post-puberty L2 learners.11 As noted earlier, French object clitic usage can be problematic for L2 learners, as indicated by several studies cited in the previous section. We examine the use of French object clitics and strong pronouns in three interviews for each individual conducted before, during, and after a period abroad of seven to nine months (a total of nine interviews over a nine-month period). The following section provides a description of the subjects and the data collection.12

3.1. Participants

Max (age 59–60 at interview) began studying French at age 48, first on his own (completing the “French in Action” video program of first-year French) and later (with his wife Eleanor) with the help of a native French tutor who met with them one hour weekly for conversational exchanges over a period of 11 years prior. Eleanor (age 53 at interview) studied for six years in high school and college and at age 28 spent two months with a family in France. She and Max vacation annually in France and do extensive reading, independent vocabulary/grammar study, audio listening, and television viewing in French for 16-18 h per week at home. At the time of the interviews, Max and Eleanor were spending four months in Paris and three months in Lyon, where they had daily contact with French in a variety of contexts. Chloe, (age 22–23 at interview), studied French for nine years in high school and college; spent six months in a family in France at age 16 (Herschensohn 2001, 2003) and four months in study abroad at age 20. Subsequently, she became an “assistante d’anglais” (English teaching assistant) in the French overseas department of Réunion for nine months. Table 2 summarizes these points.

Table 2.

Characteristics of subjects.

3.2. Materials and Methods

Although the project was ostensibly longitudinal (over seven to nine months), the interviews showed that the learners were sufficiently advanced to have reached a fairly steady state, and so the differences among the interviews were rather minimal. No notable change was observed over time in the error rate (but Chloe’s production increases over the nine month period), and for this reason, we have collapsed the results from the three interviews together. Interviews were conducted by one of the authors (who has been certified by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages), who informally evaluated the three as being at an advanced level according to the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) Guidelines (cf. http://www.actfl.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=4236). All three were able to use a range of tenses and moods, to discuss hypothetical situations and to carry out conversations on abstract and theoretical topics. They nevertheless made errors, particularly of gender assignment and aspect (Herschensohn and Arteaga 2009, 2016). Conducted in a university office or in the learner’s residence in France, each interview included elicitations of the following areas: present tense, descriptions of everyday routines and environments; past and future tenses; hypothetical situations; role play including a problem (e.g., confronting a dry cleaner for damage or introducing a speaker at a lecture). The interviewer gave leading questions to carry forward the conversation, but it was the interviewees who provided most of the dialogue.

After the interview, subjects did written grammaticality tasks related to pronouns and other topics. The GJ task was adapted from Hawkins et al. (1993) and modified to have three versions for the three interviews. Comprising 50 sentences, half of which were ungrammatical, it had been used in the earlier studies reported (Herschensohn 2001, 2003, 2004; Herschensohn and Arteaga 2007, 2009, 2016). It included sentences that targeted both pronoun use (20% of the sentences) and verb placement (80% of the sentences); representative sentences for the pronouns are included in Appendix A. Participants were asked to mark the sentences as G (grammatical), NS (not sure) or * (ungrammatical) and to correct the latter.

The data from the interviews were transcribed and checked for accuracy by three linguists fluent in French. The pronoun production data were coded and compiled by a graduate research assistant. The evidence was in the present case evaluated for all obligatory contexts of non-nominative pronouns, and for all uses of non-nominative pronouns, which were coded as strong or clitic. The production data from the nine interviews included 17,000 words, of which 217 were object clitics and 91 strong pronouns.

3.3. Results from Production and Grammaticality Judgments

The evidence from the interview production and the grammaticality judgments indicates near ceiling performance on object pronoun production and the grammaticality judgment task. Table 3 documents the suppliance in obligatory contexts (the denominator in Table 3) of the 217 accurate object clitics, Table 4 portrays the correct use of the 91 strong pronouns (plus one error), while Table 5 gives the results of the GJ task. The three interviewees produced no prosodic errors of clitics in situ or strong pronouns as preverbal; more importantly, they produced consistent and accurate elision and liaison of function words, indicating ease with the L2 prosodic alternations (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Object clitic suppliance in obligatory contexts.

Table 4.

Strong pronoun use.

Table 5.

Accuracy of pronouns in GJT.

The only errors in object clitic suppliance or word order were Eleanor’s in the second and third interviews (21).

| 21. | Eleanor (II, III) | ||||||||

| a. | vous | nous | n’ | aimez | pas | (= vous ne nous aimez pas) | |||

| you-PL | us | NEG | like-2PL | NEG | (= you-PL NEG us like-2PL NEG) | ||||

| ‘You do not like us.’ | |||||||||

| b. | dis | à | lui | (= dis-lui) | |||||

| tell-2SG | to | him-ST | (tell him-DAT-CL) | ||||||

| ‘Tell him.’ | |||||||||

Chloe made lexical errors of case assignment (22), which were not counted as lack of supply or wrong morphological form.

| 22. | Chloe (II, II, III) | ||||||||

| a. | me | visitent | (= me rendent visite) | ||||||

| me-CL | visit-3PL | (= me-ACC pay visit)) | |||||||

| ‘They visit me.’ | |||||||||

| b. | les | répondre | (= leur répondre) | ||||||

| them-ACC | to answer | (them-DAT to answer) | |||||||

| ‘To answer them.’ | |||||||||

| c. | leur | aider | (= les aider) | ||||||

| them-DAT | to help | (them-ACC to help) | |||||||

| ‘To help them.’ | |||||||||

As for the strong pronouns, most were used in PPs (obligatory suppliance indicated in Table 4 as the denominator); in addition, the three participants used freestanding strong pronouns (indicated by “+” in the table; these were supplemental, not required). These correct tokens numbered 91. Eleanor mistakenly used tu for toi in interview II (23), that is the additional “+*1” indicated in her Interview II column.

| 23. | Strong pronoun errors (Eleanor II) | ||||||

| vous, | tu | et Michel | (= vous, toi et Michel) | ||||

| you-PL | you-SG-CL | and Michel | (= you-PL you-SG-STG and Michel) | ||||

| ‘Y’all, you and Michel.’ | |||||||

The errors include mainly lexical errors (21b, the verb dire ‘to say’ requires an indirect object clitic, not a PP complement), and two case reversals on the object clitics (22b, c). Eleanor misaligns her negative clitic ne (21a) and misuses strong and clitic pronouns (21b, 24). The word order error in 21a is noteworthy in that the object clitic is placed (and “stacked”) to the left of the negative clitic particle ne—a placement incompatible with an affixal clitic analysis of object pronouns on the part of this speaker.

As the first section has shown, beginning and intermediate Anglophone learners of L2 French transfer native pronoun word order, but the evidence here indicates that these advanced learners appropriately use pronominal morphosyntax and word order. The pronominal errors produced by the interviewees do not resemble those of beginners; there are no in situ clitics or missing objects. Rather, the few mistakes that do appear are almost all lexical errors or wrong case.

As for the grammaticality judgments (Table 5), the advanced learners’ all indicated rejection of in situ clitics and across the board acceptance of properly placed object clitics. There were no errors for Eleanor, and one not sure response in Interview I for Max for ungrammatical sentence (24).13

| 24. | *Ils | deux | sont partis | à midi | (= tous les deux, ils sont partis) | |

| They | two | are gone | at noon | |||

| ‘They both left at noon.’ | ||||||

In contrast, Chloe did not complete the GJT for Interview I, and made wrong judgements for the sentences in (25) in the other sessions.

| 25. | a. | Eve-Anne s’est brossé les cheveux (NS, Int II) | ||

| ‘EA brushed her hair.’ (G) | ||||

| b. | Est-ce que vous leur avez parlé ? (*, Int II) | |||

| ‘Have you spoken to them?’ (G) | ||||

| c. | Ils deux sont partis à midi. (G, Int II, III) | |||

| ‘They both left at noon.’ (*) | ||||

The three participants correctly rejected in situ clitics and accepted correctly placed clitics (cf. Appendix A). In contrast, Chloe and her peer Emma, taking the same GJT at an earlier stage of development (Herschensohn 2004), averaged less than 70% accuracy on the task, with mistaken judgements about in situ clitics and those ungrammatically attached to past participles.

4. Discussion

Recall the research questions posed earlier.

- RQ1.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French show any evidence of prosodic transfer in their comprehension (grammaticality judgments) or production (morphosyntax) of object pronouns?

- RQ2.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French produce object pronouns with any prosodic prominence?

- RQ3.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French produce object pronouns in “stacked” sequences?

- RQ4.

- Do advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French produce object pronouns before verbs with prefixes?

Do Max, Eleanor and Chloe indicate in their use of L2 French pronouns that they have adapted their object clitics to a French-like prosodic representation of left free clitics (left sister to PWd, daughter of PPh), or do they persist in using the English-like PWd structure (right sister to PWd)? As discussed earlier, if the clitics are never stressed, the PWd analysis is eliminated, and if clitics are “stacked”, or used before prefixed verbs, the affixal analysis is invalid.

Our three learners show no evidence of prosodic prominence (stress) on object clitics that are preverbal; the only pronouns used in the stressed position (freestanding and in PPs) are strong pronouns. We therefore eliminated the PWd analysis (which may be appropriate for beginning learners who transfer in situ pronouns from English). As we saw earlier, the advanced learners’ GJs all indicated rejection of in situ clitics and across the board acceptance of properly placed object clitics. Furthermore, Max, Eleanor and Chloe show evidence of stacked pronouns (see Appendix B) as in (26).

| 26. | a. | Je ne le connais pas (Chloe II) | ||

| ‘I don’t know him.’ | ||||

| b. | il s’en fichait (Max III) | |||

| ‘he doesn’t care a whit.’ | ||||

| c. | je ne l’ai jamais visité (Eleanor III) | |||

| ‘I have never visited it.’ | ||||

Their ability to stack clitics shows that they are not using a flipped affixal clitic analysis (which permits no stacking), but rather are treating these leftward clitics attached to inflected and infinitival verbs as free clitics. Finally, Max at least uses preverbal object clitics with verbs containing prefixes such as ré-, and dé- (Appendix B).

The accuracy of both production and comprehension (GJs) indicates mastery of the L2 French morphosyntax of clitic pronouns. As Arche and Domínguez (2011, p. 305) note, “if learners have acquired the morphosyntactic properties of Spanish clitics, then high rates in both the production and comprehension tasks will be observed.” We answer the first question in the negative, as the learners have overcome the transfer of English word order and morphosyntax; their only errors are lexical. We consequently see no impaired representation of their L2 syntax with respect to the use of strong and clitic pronouns in French. Although beginning and low intermediate French L2 learners make persistent errors with in situ clitics in behavioral responses and non-native neural responses, advanced Anglophone learners of L2 French master French pronoun word order and morphosyntax. These advanced learners demonstrate target-like mastery of French pronoun word order and prosody in production, and sensitivity to ungrammatical uses in grammaticality judgments. Similarly to Gabriele et al.’s (2013, p. 225) observations, we believe “our results show that by an advanced level of proficiency, learners can process features not instantiated in the native language similarly to native speakers”.

As for prosodic stucture, recall that English pronouns vary in prosodic realization between prosodic words and affixal clitics-right, while French consistently requires object pronouns to be free clitics-left. However, we noted the availability of leftward free clitics in both L1 and L2 DPs. It is our point that learners are incapable of gaining the free clitic construction for French clitic pronouns for quite a long time. Anglophone learners are able to gain free clitic articles at the beginning and intermediate stages, so the free clitic prosodic structure is presumably available to beginning–intermediate learners in L1 English and L2 French articles (which are morphologically identical to third person clitic pronouns). The difficulty that the Anglophone learners have with French object pronouns is clearly not a difficulty with the prosody at the beginning and early intermediate stages, since they master the article plus noun left-clitic structure early on (indeed, they can simply transfer the L1 to L2 DP prosody). Our point is that a combination of factors that differentiate English and French pronouns—the contrasts noted by Cardinaletti and Starke (1999) in terms of semantic, morphological, syntactic and phonological properties—seem to converge to inhibit command of French object pronouns by early Anglophone learners. We propose that it is not until high intermediate (cf. Sneed German et al. 2015) and advanced levels that learners finally gain the implicit mastery that enables them to transfer this article free clitic prosody from DP to TP. Despite its availability, the beginning and intermediate learners were unable to adapt that structure to TP in L2 French. Eventually, though, at the advanced level, learners attain the ability to adapt the DP structure of prosodic free clitics to the TP domain, supporting the PTH (transfer of the L1 free clitic article) and the related concept of minimal adaptation (adapting the DP clitic to a TP domain) of native prosodic structures to construct the new L2 structures. The prosodic transfer hypothesis maintains that target prosody can be built when L1 structures can be licensed in new positions, and it is clear that the advanced learners have mastered the leftward clitics, licensing the pronominal objects in L2 preverbal instead of L1 postverbal positions. A lack of stressed preverbal clitics, together with the presence of stacked clitics and clitics before prefixed verbs, demonstrates that the correct surface word order corresponds to the correct prosodic structure as well; the clitics are prosodified as free clitics, and not as PWds or affixal clitics.

Together with previous research, our results show that target prosody achieved via minimal adaptation, that is the transfer of the free clitic construction (article + noun) to a new context (pronoun + verb), cannot take place in an immediate transfer, but rather, a certain threshold of proficiency must be reached before the prosodic structures are adapted. Morphosyntax and prosody must apparently develop in parallel.

5. Conclusions

Beginning and low intermediate Anglophone L2 French learners are insensitive to French prosodic constraints in using in situ pronouns transferred from the L1, as proposed by the prosodic transfer hypothesis.14 The PTH proposes that native prosodic structures may be adapted to facilitate the acquisition of L2 prosodic structure. This study has presented new evidence from three Anglophone advanced learners of L2 French that indicates ceiling performance for pronoun production (99% accuracy in 300 tokens over nine interviews) and grammaticality judgments (98% accuracy). This native-like performance demonstrates that target French morphosyntax and prosody, are built—as predicted by the PTH—by licensing pronominal free clitics in a new pre-verbal L2 position distinct from post-verbal L1. Furthermore, accurate prosody is confirmed by correct pronoun placement, pronoun use in stacked sequences and with prefixed verbs, as well as target-like production of prosodic alternations (liaison, elision) in the learners’ data. These results counter impaired representation approaches and suggest that early missing inflection may be overcome.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deborah Arteaga, Elisa Sneed German, Cheryl Frenck Mestre, Neal Snape and audiences at EuroSLA 2016 and GALA 2017 for comments and questions. We thank Kristen Piepgrass for transcribing and coding the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Examples of Grammaticality Judgment Sentences with Pronouns/Clitics*

- La television? Nous la regardons tous les jours. (‘The television? We watch it every day.’)

- *Marie? Est-ce que vous avez vu la? (=vous l’avez vue?) (‘Marie? Have you seen her?’)

- Eve-Anne s’est brossé les dents. (‘Eve-Anne brushed her teeth.’)

- *Marc a lave se avec du savon de Marseille (=Marc s’est lavé). (Marc washed with soap from Marseille.)

- Est-ce que tu leur as parlé? (‘Did you speak to them?’)

- *Marie et Paul, je la et le connais. (=je les connais) (‘Marie and Paul, I know them.’)* indicates ungrammaticality; the correct sentence follows.

Appendix B. Examples of Stacked Clitics and Clitics before Prefixed Verbs

- Stacked clitics

- Je ne le connais pas. (Chloe II) (‘I don’t know him.’)

- Je vois aucune façon de s’en sortir. (Chloe III) (‘I see no way of getting out of here.’)

- Tout le monde s’y intéresse. (Max II) (‘everyone is interested in that.’)

- Il s’en fichait. (Max III) (‘he didn’t care a whit about it.’)

- Le soleil ne s’est levé jusqu’à 8h30. (Eleanor II) (‘the sun didn’t come up until 8:30.’)

- Je ne l’ai jamais visité. (Eleanor III) (‘je have never visited it’)

- Clitics before prefixed verbs

- Mais tout le monde est en train de se déplacer. (Max I) (‘… everyone is moving’)

- Pour assurer qu’aucun étudiant ne se démarque pas par rapport aux autres. (Max II) (‘to make sure that no student stands out with respect to the others.’)

- Son désir est de se réintégrer. (Max III) (‘her desire is to reintegrate herself.’)

References

- Adiv, Ellen. 1984. Language learning strategies: The relation between L1 operating principles and language transfer in L2 development. In Second Languages: A Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Edited by Roger Andersen. Rowley: Newbury House, pp. 125–42. [Google Scholar]

- Arche, María J., and Laura Domínguez. 2011. Morphology and syntax dissociation in SLA: Evidence from L2 clitic acquisition in Spanish. In Morphology and Its Interfaces. Edited by Alexandra Galani, George Tsoulas and Glyn Hicks. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 291–320. [Google Scholar]

- Auger, Julie. 1994. Pronominal Clitics in Québec Colloquial French: A Morphological Analysis. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, Meaghen. 2005. Prosodic constraints and the syntax-phonology interface: The phonology of object clitics in L2 French. In BUCLD 29 Proceedings. Edited by Alejna Brugos, Manuella R. Clark-Cotton and Seungwan Ha. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 122–33. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Michal Starke. 1999. The typology of structural deficiency: A case study of the three classes of pronouns. In Clitics in the Languages of Europe. Edited by Henk van Riemsdijk. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 145–233. [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson, Jennifer. 2010. Convergent evidence for categorical change in French: From subject clitic to agreement marker. Language 86: 85–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux, and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. The role of semantic transfer in clitic drop among simultaneous and sequential Chinese-Spanish bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 35: 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cat, Cécile. 2005. French subject clitics are not agreement markers. Lingua 115: 1195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, Nigel, Lydia White, Joyce Bruhn de Garavito, Silvina Montrul, and Philippe Prévost. 2002. Clitic placement in L2 French: Evidence from sentence matching. Journal of Linguistics 38: 487–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucart, Alice. 2008. Grammatical Gender Processing in French as a First and Second Language. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, 2008, Université de Provence & University of Edinburgh, Provence, France, Edinburgh, Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- Friederici, Angela D., Erdmut Pfeifer, and Anja Hahne. 1993. Event related brain potentials during natural speech processing: Effects of semantic, morphological and syntactic violations. Cognitive Brain Research 1: 183–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, Alison, Robert Fiorentino, and José Alemán Bañón. 2013. Examining second language development using event-related potentials: A cross-sectional study on the processing of gender and number agreement. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 213–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goad, Heather, and Meaghen Buckley. 2006. Prosodic structure in child French: Evidence for the foot. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 5: 109–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goad, Heather, and Lydia White. 2004. Ultimate attainment of L2 inflection: effects of L1 prosodic structure. In EuroSLA Yearbook 4. Edited by Susan H. Foster-Cohen, Michael Sharwood Smith, Antonella Sorace and Mitsuhiko Ota. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins, pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Goad, Heather, and Lydia White. 2006. Ultimate attainment in interlanguage grammars: A prosodic approach. Second Language Research 22: 243–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goad, Heather, and Lydia White. 2008. Prosodic structure and the representation of L2 functional morphology: A nativist approach. Lingua 118: 577–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goad, Heather, and Lydia White. 2009. Prosodic transfer and the representation of determiners in Turkish-English interlanguage. In Representational Deficits in SLA: Studies in Honor of Roger Hawkins. Edited by Neal Snape, Yan-kit Ingrid Leung and Michael Sharwood Smith. Amsterdam and Philadellphia: J. Benjamins, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Goad, Heather, Lydia White, and Jeffrey Steele. 2003. Missing inflection in L2 acquisition: defective syntax or L1-constrained prosodic representations? Canadian Journal of Linguistics 48: 243–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, Ana. C., Colin Phillips, Nina Kazanina, and David Poeppel. 2010. The linguistic processes underlying the P600. Language and Cognitive Processes 25: 149–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granfeldt, Jonas. 2005. The development of gender attribution and gender concord in French: A comparison of bilingual first and second language learners. In Focus on French as a Foreign Language. Edited by Jean-Marc Dewaele. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Granfeldt, Jonas, and Suzanne Schlyter. 2004. Cliticisation in the acquisition of French as L1 and L2. In The Acquisition of French in Different Contexts: Focus on Functional Categories. Edited by Philippe Prévost and Johanne Paradis. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins, pp. 334–70. [Google Scholar]

- Grüter, Theres. 2008. When learners know more than linguists: (French) direct object clitics are not objects. Probus 20: 211–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, Theres, and Martha Crago. 2012. Object clitics and their omission in child L2 French: The contribution of processing limitations and L1 transfer. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 531–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagoort, Peter, and Colin M. Brown. 1999. Gender electrified: ERP evidence on the syntactic nature of gender processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 28: 715–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamann, Cornelia. 2004. Comparing the development of the nominal and the verbal functional domain in French Language Impairment. In The Acquisition of French in Different Contexts: Focus on Functional Categories. Edited by Philippe Prévost and Johanne Paradis. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins, pp. 109–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hannahs, S.J. 1995. The phonological word in French. Linguistics 33: 1125–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roger. 2001. Second Language Syntax. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Roger, and Cecilia Yuet-hung Chan. 1997. The partial availability of Universal Grammar in second language acquisition: The ‘failed functional features hypothesis’. Second Language Research 13: 187–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roger, and Florencia Franceschina. 2004. Explaining the acquisition and non-acquisition of determiner-noun gender concord in French and Spanish. In The Acquisition of French in Different Contexts. Focus on Functional Categories. Edited by Philippe Prévost and Johanne Paradis. Philadelphia and Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 175–207. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Roger, Richard Towell, and Nives Bazergui. 1993. Universal Grammar and the acquisition of French verb movement by native speakers of English. Second Language Research 9: 189–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschensohn, Julia. 2000. The Second Time Around: Minimalism and L2 Acquisition. Philadelphia and Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Herschensohn, Julia. 2001. Missing inflection in L2 French: Accidental infinitives and other verbal deficits. Second Language Research 17: 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschensohn, Julia. 2003. Verbs and rules: Two profiles of French morphology acquisition. Journal of French Language Studies 13: 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschensohn, Julia. 2004. Functional categories and the acquisition of object clitics in L2 French. In The Acquisition of French in Different Contexts: Focus on Functional Categories. Edited by P. Prévost and J. Paradis. Philadelphia and Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 207–42. [Google Scholar]

- Herschensohn, Julia, and Deborah Arteaga. 2007. Marquage grammatical des syntagmes verbaux et nominaux d’un apprenant avancé. AILE 25: 159–78. [Google Scholar]

- Herschensohn, Julia, and Deborah Arteaga. 2016. Parameters, features and re-assembly in L2 French DP. In The Acquisition of French in Multilingual Contexts. Edited by Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes, Katrin Schmitz and Natascha Müller. Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matters, pp. 215–33. [Google Scholar]

- Herschensohn, Julia, and Deborah Arteaga. 2009. Tense and Verb Raising in advanced L2 French. Journal of French Language Studies 19: 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, Michael L., and Veena D. Dwivedi. 1998. Syntactic processing by skilled bilinguals. Language Learning 48: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulk, Aafke. 2004. The acquisition of the French DP in a bilingual context. In The Acquisition of French in Different Contexts: Focus on Functional Categories. Edited by Philippe Prévost and Johanne Paradis. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins, pp. 243–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard. 1975. French Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lado, Robert. 1957. Linguistics across Cultures: Applied Linguistics for Language Teachers. Ann Arbor: University Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2007. Ultimate Attainment in Second Language Acquisition: A Case Study. Mahwah: L. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, Judith, Darren Tanner, Ilona Pitkänen, Cheryl Frenck-Mestre, Kayo Inoue, Geoffrey Valentine, and Lee Osterhout. 2010. Brain potentials reveal discrete stages of L2 grammatical learning. Language Learning 60 S2: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, Francisco, and Lori Repetti. 2014. On the morphological restrictions of hosting clitics in Italian and Sardinian dialects. L’Italia Dialettale: Rivista di Dialettologia Italiana 75: 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Osterhout, Lee, Judith McLaughlin, Albert Kim, Ralf Greenwald, and Kayo Inoue. 2004. Sentences in the brain: Event-related potentials as real-time reflections of sentence comprehension and language learning. In The On-Line Study of Sentence Comprehension: Eyetracking, ERP, and Beyond. Edited by Manuel Carreiras and Charles E. Clifton Jr. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osterhout, Lee, Judith McLaughlin, Ilona Pitkänen, Cheryl Frenck-Mestre, and Nicola Molinaro. 2006. Novice learners, longitudinal designs, and event-related potentials: A paradigm for exploring the neurocognition of second-language processing. Language Learning. 56: 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, Antoine Tremblay, and Martha Crago. 2014. French-English bilingual children’s sensitivity to child-level and language-level input factors in morphosyntactic acquisition. In Input and Experience in Bilingual Development. Edited by Theres Grüter and Johanne Paradis. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins, pp. 161–80. [Google Scholar]

- Perpiñán, Silvia. 2017. Catalan-Spanish bilingualism continuum: The expression of non-personal Catalan clitics in the adult grammar of early bilinguals. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7: 477–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévost, Philippe. 2009. The Acquisition of French: The Development of Inflectional Morphology and Syntax in L1 Acquisition, Bilingualism, and L2 Acquisition. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Philippe, and Lydia White. 2000. Accounting for morphological variation in second language acquisition: Truncation or missing inflection? In The Acquisition of Syntax: Studies in Comparative Developmental Linguistics. Edited by Marc-Ariel Friedemann and Luigi Rizzi. Harlow: Longman, pp. 202–35. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Ian. 2010. Agreement and Head Movement: Clitics, Incorporation and Defective Goals. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, Jason. 2011. L3 syntactic transfer selectivity and typological determinacy: The Typological Primacy Model. Second Language Research 27: 107–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Bonnie D., and Rex A. Sprouse. 1996. L2 cognitive states and the full transfer/full access model. Second Language Research 12: 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinker, Larry, Merrill Swain, and Guy Dumas. 1975. The interlanguage hypothesis extended to children. Language Learning 25: 139–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1996. The prosodic structure of function words. In Signal to Syntax: Bootstrapping from Speech to Grammar in Early Acquisition. Edited by James L. Morgan and Katherine Demuth. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 187–213. [Google Scholar]

- Snape, Neal, Yan-kit Ingrid Leung, and Michael Sharwood Smith, eds. 2009. Representational Deficits in SLA: Studies in Honor of Roger Hawkins. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Snape, Neal, and Tanja Kupisch. 2010. Ultimate attainment of second language articles: A case study of an endstate second language Turkish-English speaker. Second Language Research 26: 527–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneed German, Elisa, Julia Herschensohn, and Cheryl Frenck-Mestre. 2015. Pronoun processing in Anglophone late L2 learners of French: Behavioral and ERP evidence. Journal of Neurolinguistics 34: 15–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, Karsten. 2014. Event related potentials (ERPs) in second language research: A brief introduction to the technique, a selected review and an invitation to reconsider critical periods in L2. Applied Linguistics 35: 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhauer, Karsten, John E. Drury, Paul Portner, Matthew Walenski, and Michael T. Ullman. 2010. Syntax, concepts and logic in the temporal dynamics of language comprehension: Evidence from event-related potentials. Neuropsychologia 48: 1525–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, Darren, Judith McLaughlin, Julia Herschensohn, and Lee Osterhout. 2013. Individual differences reveal stages of L2 grammatical acquisition: ERP evidence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 16: 367–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimpli, Ianthi Maria, and Maria Dimitrakopoulou. 2007. The Interpretability Hypothesis: Evidence from wh-interrogatives in second language acquisition. Second Language Research 23: 215–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Lydia. 1996. Clitics in L2 French. In Generative Perspectives on Language Acquisition. Edited by Harald Clahsen. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins, pp. 335–68. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Even early bilinguals may show variability. Perpiñán (2017) describes non target-like responses by Spanish-dominant bilinguals for Catalan clitics non-existent in Spanish, indicating a divergent Catalan grammar despite very early exposure (before age four) to Catalan. |

| 2 | Hoover and Dwivedi (1998) and Duffield et al. (2002) study the use of clitics (in reading and sentence matching tasks, respectively) in French students that they label as advanced. |

| 3 | Romance clitic syntax has been discussed for decades within generative theory, beginning with Kayne (1975). See recent summaries by Roberts (2010) and Grüter (2008). Generally, there are two approaches, one group treating clitics as agreement markers on the verb (Grüter 2008; Culbertson 2010), and the other arguing that clitics must move from within the Verb Phrase (Kayne 1975; Roberts 2010; Cardinaletti and Starke 1999; De Cat 2005). |

| 4 | Our focus here is on strong and clitic pronouns that are relevant for French and English. In Italian in Telefono a loro ‘we phone them’ the pronoun is strong, in Telefono loro it is weak, and in Gli telefono it is a clitic (Ordoñez and Repetti 2014). |

| 5 | We thank a reviewer for pointing out that the syntactic literature on clitics has used the distinction phonological versus syntactic clitics to refer to the English clitic-right type versus the French clitic-left type (cf. Kayne 1975; Auger 1994). |

| 6 | Herschensohn (2004) reports on Chloe, one of the subjects of the current study, at an earlier stage of her L2 French acquisition, at which she makes numerous production and comprehension errors. |

| 7 | For discussion, see Gouvea et al. (2010); Steinhauer et al. (2010). |

| 8 | Given the incremental appearance of the clitic le, the reader’s first reaction to (20a) would be to process le as an article of an anticipated noun phrase. |

| 9 | Buckley (2005), in a phonological analysis of a clitic production task given to intermediate French learners, found a small sub-group of her participants who stress the clitics; most of the participants did not assign prominence to the clitics. |

| 10 | An anonymous reviewer notes “in order to show that clitics are free clitics in interlanguage French, it must be shown that no other analysis is possible.” We thank this reviewer for suggesting the following diagnostics. |

| 11 | This research protocol was approved by the University of Washington IRB committee, in compliance with human subjects guidelines. All subjects gave their informed consent to participate in interviews and grammaticality tasks. Pseudonyms are used. |

| 12 | Chloe’s L2 French mastery at an earlier stage is reported in Herschensohn (2001, 2003, 2004); the three advanced learners are documented (for TP and DP phenomena) in Herschensohn and Arteaga (2007, 2009, 2016). |

| 13 | Sentence (25) was not varied for the three versions; it is ungrammatical since the subject clitic is stressed, but can only be corrected through paraphrase. |

| 14 | We thank a reviewer for pointing out that in order to show that the difficulty is for prosodic reasons, further research should include the three levels of proficiency using the same experimental tasks. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).