Abstract

The aim of this paper is to reconsider some aspects of the so-called clause/noun-phrase (non-)parallelism (Abney 1987 and much subsequent work). The question that arises is to find out what is common and what is different between the clause as a Complementizer Phrase (CP)-structure and the noun as a Determiner Phrase (DP)-structure in terms of structure and derivation. An example of structural parallelism lies in the division of the clause and the noun phrase into three domains: (i) the Nachfeld (right periphery), which is the thematic domain; (ii) the Mittelfeld (midfield), which is the inflection, agreement, Case and modification domain and (iii) the Vorfeld (left periphery), which is the discourse- and operator-related domain. However, we will show following Giusti (2002, 2006), Payne (1993), Bruening (2009), Cinque (2011), Laenzlinger (2011, 2015) among others that the inner structure of the Vorfeld and of the Mittelfeld of the clause is not strictly parallel to that of the noun phrase. Although derivational parallelism also lies in the possible types of movement occurring in the CP and DP domains (short head/X-movement, simple XP-movement, remnant XP-movement and pied-piping XP-movement), we will see that there is non-parallelism in the application of these sorts of movement within the clause and the noun phrase. In addition, we will test the respective orders among adverbs/adjectives, DP/Prepositional Phrase (PP)-arguments and DP/PP-adjuncts in the Mittelfeld of the clause/noun phrase and show that Cinque’s (2013) left–right asymmetry holds crosslinguistically for the possible neutral order (without focus effects) in post-verbal/nominal positions with respect to the prenominal/preverbal base order and its impossible reverse order.

1. Introduction

Since the very beginning of Generative Grammar the parallelism between the deverbal nominal construction the enemy’s recent destruction of the city and the clause The enemy recently destroyed the city has been questioned. Lees proposes that such derived nominals are the result of transformational rules that apply in syntax [1]. Chomsky argues against this syntactic approach and assumes that such constructions are derived through lexical rules within the framework of what will be called the Lexicalist Hypothesis [2].

The structural parallelism between the noun phrase (NP) and the clause has emerged more strikingly from Abney’s [3] Determiner Phrase (DP)-hypothesis and has been further developed and discussed in much subsequent work (Cinque [4], Giusti [5,6,7], Payne [8], Bruening [9], Laenzlinger [10,11], among others; see also Bernstein [12] for an overview).1 The aim of this paper is to revisit some properties related to the so-called clause/noun phrase parallelism. The question that arises is to find out what is common and what is different between the clause as a Complementizer Phrase (CP)-structure and the noun as a DP-structure in terms of structure and derivation.2

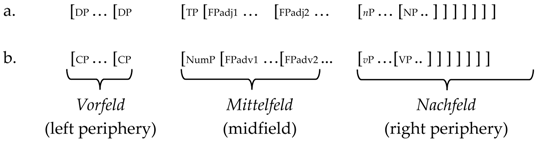

At first sight one case of structural parallelism lies in the division of the clause and the noun phrase into three domains (Grohmann [16], Laenzlinger [10], Wiltschko [17]).

| 1. |  |

These three domains (DP/CP, NumP/TP and NP/VP) are constituted of multilayered split-structures. The Nachfeld is the thematic domain where the arguments merge and their θ-role is assigned/valued (Laenzlinger [10], Larson [18], and Chomsky [19], among others). The Mittelfeld (or midfield) is the inflection, agreement and Case domain (Pollock [20], Belletti [21], Cinque [4,22]). It is also the domain where modifiers externally merge (adjectives and adverbs, see Cinque [22,23]; Laenzlinger [10,11,24]). The Vorfeld is the discourse-related, referential and quantificational domain (Laenzlinger [10], Rizzi [25], Rizzi and Bocci [26], Aboh [27]). However, it will be demonstrated that the inner structure of the left periphery and of the midfield of the clause is not strictly parallel to that of the noun phrase (Payne [8], Bruening [9]).

As will be shown in this paper, there is also derivational parallelism in the possible types of movement occurring in the CP and DP structures: short X-movement, simple XP-movement, remnant XP-movement and pied-piping XP-movement. Nevertheless, we will see that there is non-parallelism in the application of these sorts of movement within the clause and the noun phrase. To be more precise, in this article we will study the order among adverbs/adjectives, DP/Prepositional Phrase (PP)-arguments and DP/PP-adjuncts in the Mittelfeld and the Vorfeld of the clause/noun phrase and test if Cinque’s left–right asymmetry [28] (see (2) below) holds for the possible neutral order (without focus effects) in post-verbal/nominal positions (2c) and (2d) with respect to the base order in (2a) and the impossible reverse order in (2b).

| 2. | Left–right asymmetry | ||||||||

| GermanV-final/Tatar/Japanese | |||||||||

| a. | (x) y z | V/N (base) | |||||||

| b. | *z y | (x) V/N | |||||||

| GermanV2/English/Romance | |||||||||

| c. | V/N | (x) | y | z | |||||

| d. | V/N | z | y | (x) | |||||

The paper is organized as follows. After the introduction Section 2 deals with the structure of the left periphery for the clause (Section 2.1) and the noun phrase (Section 2.2). We will present arguments in favor of a split-CP/DP structure on the basis of multiple complementizer and determiner occurrences, fronting of arguments and adjuncts for topicalization, focalization and other informational prominence effects. Section 2.1 is concerned with the Nachfeld involving a vP shell structure for the clause and its corresponding nP shell for the noun phrase and their left periphery. The arguments merge in the thematic domain according to the Universal Thematic Hierarchy. Immediately above vP/nP, there are discourse-related positions (e.g., a focus position). In Section 3 the midfield of the clause (Section 3.1) and of the noun phrase (Section 3.2) is described and analyzed comparatively in some languages of different families. The relevant constituents whose respective ordering is studied are adjectives/adverbs, DP/PP-adjuncts and DP/PP-arguments. We will show that Cinque’s left–right asymmetry holds for several languages according to their V/N-initial and V/N-final configurations. Section 4 contains the conclusion.

2. The Rich Structure of the Left Periphery

2.1. The Clause (CP)

Since Rizzi [25] the CP layer has been assigned a Force-Finiteness articulation. The cartography of the split-CP structure is given in (3) following Rizzi [25,29,30] and Rizzi and Bocci [26].

| 3. | Force > Top* > Int > Top*> Foc > Mod* > Top* > QPembed > Fin > Subj |

In French the arguments can move to Topic Phrase (TopP) (recursively in clitic-left dislocation), as illustrated below in (4a, c and d). Movement to Focus Projection (FocP as a single projection) is restricted to adjuncts in French contrary to Italian, as shown in (4b–c).3

| 4. | a. | [TopP | De | ce | livre, | [SubjP | je sais | que | tu | en | parleras]] | |||||||||||

| About | this | book, | I know | that | you | of-it | talk-fut | |||||||||||||||

| ‘About this book, I know you will talk.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | [FocP | DEMAIN, | [SubjP | nous | irons | à | la plage, | pas aujourd’hui]] | ||||||||||||||

| Tomorrow-foc | we | go-fut | to | the beach, | not today | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘TOMORROW we will go to the beach, not today.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | [FocP | DEMAIN, | [TopP | à | la plage, | nous y | irons, | pas aujourd’hui]] | ||||||||||||||

| Tomorrow-foc | to | the beach | we there | go-fut, | not today | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘TOMORROW to the beach we will go, not today.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | [TopP | A | la plage | [FocP | DEMAIN, | nous y | irons, | pas aujourd’hui]] | ||||||||||||||

| To | the beach | tomorrow-foc | we there | go-fut, | not today | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘To the beach TOMORROW we will go, not today.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

As argued by Rizzi [30], fronted adverbs move to Mod(if)P (modifier projection). Crossing another modifier results in a Relativized Minimality effect, as shown in (5) with the adverb probably blocking movement of lentement.4

| 5. | Lentement, | ils | se | sont | (*probablement) | tous | dirigés | vers | la sortie |

| Slowly | they | Pron-REFL | are | (*probably) | all | move | toward | the exit | |

| ‘Slowly, they (*probably) all move to the exit.’ | |||||||||

The data in (6) indicate that PP-adjuncts target a Top projection rather than a Mod(if) projection provided that there is no Relativized Minimality effect from the intervention of an adverb (Top vs. Mod(if)).

| 6. | a. | Dans | deux | jours, | nous | irons | probablement | à | la plage. | |||||||

| In | two | days | we | go-FUT | probably | to | the beach | |||||||||

| ‘In two days we will probably go to the beach’ | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | De | ses | propres | mains, | il | a | récemment | réparé | des | Voitures. | ||||||

| Of | his | own | hands | he | has | recently | repaired | DET-INDEF | cars | |||||||

| ‘With his own hands, he recently repaired (some) cars’ | ||||||||||||||||

The different occurrences of complementizers (que/that si/if, de, à, etc., see Rizzi [25,30]) are further arguments in favor of a rich split-CP structure. It is assumed that they occupy distinct positions in the left periphery (Force, Interrogative (Int), Finite (Fin)). The fact that complementizer doubling exists in some languages (Irish English, Dutch, Picard, Northern Italian dialects, early Romance, spoken Spanish, European Portuguese; see McCloskey [31], Villa-García [32] and Paoli [33] for data and references) gives further support for the split CP. The higher complementizer occurs in Force and the lower one in Fin and a topic or a focus can be sandwiched between them.5 Note that, akin to complementizers, determiner doubling and determiner spreading are attested in languages like Swedish, Romanian, Hebrew and Swiss/German dialects for the former and Greek for the latter. These facts will be discussed in the next section. As regards complementizer ‘spreading’, Villa-Garcia reports the example of spoken Spanish in (7) with multiple topics [32].

| 7. | Me | dijeron | que | si llueve | (que) | se | quedan | aquí, | y | que | si nieva | (que) | también. |

| cl. | said | that | if rains | that | cl. | stay | here | and | that | if snows | that | too | |

| ‘They told me that they are going to stay here if it rains or snows.’ | |||||||||||||

2.2. The Noun Phrase (DP)

By analogy with Rizzi’s split-CP analysis, some authors (Giusti [5,6,7], Laenzlinger [10,11,24], Aboh [27], Puskás and Ihsane [35], Ihsane [36] among others) propose a split-DP structure. What corresponds to Force is Ddeixis/specificity and, similarly, Fin is equated to Ddefinitness/determination. Laenzlinger [10,11] puts forth the structure in (8) which also contains dedicated positions for fronted constituents (topic, focus, etc.).

| 8. | Structure: (QP) > DPdeixis > FocP > TopP/ModifP > DPdet |

According to Laenzlinger [10,11] and Cinque [37] the focus projection hosts emphatic fronted adjectives in Romance. This is illustrated in (9a) for French. The ungrammaticality of example (9b) shows that there is a single FocP available in the left periphery.

| 9. | a. | C’ | est | une | SUPERBE | nouvelle | occasion. | ||||

| This | is | a | superb-foc | new | occasion | ||||||

| ‘This is a SUPERB new occasion.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | *C’ | est | une | RECENTE | SUPERBE | voiture | rouge | italienne. | |||

| This | is | a | recent-foc | superb-foc | car | red | Italian | ||||

| ‘This is RECENT SUPERB red Italian car.’ | |||||||||||

French and other Romance languages also have a low FocP (see Samek-Lodovici [38]), situated near NP, as illustrated by the following example (see Section 2 and Section 3.2).

| 10. | (C’est) | une | voiture | rouge | italienne | SUPERBE. |

| (This is) | a | car | red | Italian | superb | |

| ‘(This) is a SUPERB red Italian car.’ | ||||||

The specifier of TopP in (8) is a position for topicalized arguments and adjuncts, while the specifier of ModifP (Modifier Projection) is a position for fronted non-focalized adjectives. The order among TopP, FocP and ModifP is difficult to establish given that the left periphery of the noun phrase is more constrained in terms of constituent fronting than that of the clause. In other words, the information structure of the noun phrase is poorer (less developed) than that of the clause. This restriction is arguably due to the fact that DPs are usually embedded within CP (except in elliptic constructions, e.g., responses to questions or non-verbal expressions, e.g., interjections) and hence have indirect access to discourse contexts.

The paradigm below exemplifies movement of arguments to TopP or FocP in Serbo-Croatian, Hungarian, Russian and Greek. In (11a/a’) the Dative complement is topicalized in front of the adjective of quality as the result of movement of the DP to the specifier of a left-peripheral TopP. This is also the case of the Genitive DP complement in (11b/b’). The Hungarian example in (11c’) is an instance of movement of the noun’s Dative complement to a topic position in the DP-layer. The Russian example in (11d’) as compared to (11d) shows that the Genitive complement is fronted for topicalization or focalization effects. In (11e/e’) one can observe that the Genitive Possessor DP can move to the specifier of a left-peripheral focus projection (see originally Horroks and Stravou [39]). Finally, the Romanian example in (11f’) illustrates movement of the noun’s Genitive complement (see (11f)) to a topic fronted position as a marked option.

| 11. | a. | [DP | [QualP | velikodušana | [NP | pomoć] | [PP | u novcu] | [DP | siromasnima] ]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| generous | gift | of money | the-poor-DAT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a′. | [DP | [TopP | [DP | siromasnima] | [QualP | velikodušana | [NP | pomoć] | [PP | u novcu] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the-poor-DAT | generous | gift | of money | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [DP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘a generous gift of money to the poor.’ | Serbo-Croatian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | [DP | [QualP | lepa | [NP | ćerka] | [DP+Gen | Slavnoy matematičara]]] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| nice | girl | famous mathematician-GEN | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘the famous mathematician’s nice girl.’ | Serbo-Croatian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b′. | [DP | [TopP | [DP+Gen | slavnoy matematičara] | [QualP | lepa | [NP | ćerka]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| famous mathematician-GEN | nice | girl | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | [DP | egy | [QualP | nagylelkü | [NP | pénz | adomány ] | [DP | a szegenyeknek] | [PP | a | bank reszerol]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | generous | money | gift | the-poor-DAT | the | bank by | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c′. | [DP | egy | [TopP | [DP | a szegényeknek] | [TopP | [PP | a | bank | részeéöl] | [QualP | nagylelkü | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | the-poor-DAT | the | bank | by | generous | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [NP | pénz | adomány] | [DP | [PP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| money | gift | the-poor-DAT | the bank by | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘a generous gift of money to the poor by the bank.’ | Hungarian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | [DP | [[QualP | velikolepnaya | [NP | mašina]] | [FPGen | [DP | moego | papi] ]] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| beautiful | car | my | father-GEN | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘my father’s beautiful car.’ | Russian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d′. | [DP | [TopP/FocP | [DP | moego papi +Gen] | [[QualP | velikolepnaya | [NP | mashina]] | [FPpp | s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| my father-GEN | beautiful | car | with | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| otkryvaiusheisia | kryshjei]]]] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| open | roof | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘my father’s beautiful car with an open roof.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| e. | [DP | to | [AdjP | oreo] | [DP | to | [NP | vivlio] | [DP+Gen | tis Marias]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the | nice | the | book | the Maria-GEN | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Maria’s nice book.’ | Greek [40] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| e′. | [DP | [FocP | [DP | tis Marias] | [DP | to | [AdjP | oreo] | [DP | to | [NP | vivlio ]]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the Maria-GEN | the | nice | the | book | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| f. | [DP | [AdjP | frumoasa] | [NP | maşină] | [DP+Gen | a | lui | Ion]] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| beautiful | car | POSS | the | Ion-GEN | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Ion’s beautiful car.’ | Romanian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| f′. | [DP | [TopP | [DP+Gen | a | lui | Ion] | [AdjP | frumoasă] | [NP | maşină]]] (marked option) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| POSS | the | Ion-GEN | beautiful | car | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Ion’s beautiful car.’ | Romanian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note that movement (fronting) of arguments can target a Case position in the left periphery, as in the Saxon Genitive constructions in (12a,b) and the possessive construction in Hungarian in (12d) in which a Dative Case (vs. a Nominative Case in (12c)) is assigned to the possessor.

| 12. | a. | [DP [GenP [DP John]’s [DP [NP [[DP | English | ||||||||||||

| b. | [DP [GenP [DP Johanns] [DP [NP [DP | German | |||||||||||||

| c. | [DP | (a) | [NomP | [DP | Mari] | [QualP | szép | [NP | kalap-ja]]] | Hungarian [41] | |||||

| the | Mari-NOM | nice | hat | ||||||||||||

| ‘Mari’s nice hat.’ | |||||||||||||||

| d. | [DP | [DatP | [DP | Mari-nak] | [DP | a | [QualP | szép | [NP | kalap-ja ]]]]] | |||||

| Mari-DAT | the | nice | hat | ||||||||||||

| ‘Mari’s nice hat.’ | |||||||||||||||

As already mentioned, adjective fronting can be triggered by focalization. This is the case not only in French (example (9a) and (13a)), but also in Greek (example (13b)). English also displays movement of adjectives to a left-peripheral focus position (example (13c,d)) and to a quantifier position (example (13e,f)).

| 13. | a. | [DP | une | [FocP | SPLENDIDE | [AgrP | voiture | [QualP | [NP | |||||||||||

| a | splendid-foc | car | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘a SPLENDID car.’ | French | |||||||||||||||||||

| b. | [DP | to | [FocP | KOKKINO | [DP | to | [NP | forema] | [QualP | [NP | ||||||||||

| the | RED | the | dress | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘the RED dress.’ | Greek | |||||||||||||||||||

| c. | These are BLACK small dogs, not white ones. | |||||||||||||||||||

| d. | [DP [FocP How clever [DP a [QualP | |||||||||||||||||||

| e. | This is [QP too tough [DP a [QualP | |||||||||||||||||||

| f. | [QP Such [DP a [question]]] | English | ||||||||||||||||||

As in Romance, adjectives can be fronted in Serbo-Croatian for prominence effects (see Guisti [5] for data and discussion). The adjective lepa ‘beautiful’ in (14) moves past the possessive element moya ‘my’.7

| 14. | [DP | [TopP/Modif | lepa | [PossP | moja | [QualP | [NP | devojčica ]]]]] | |

| beautiful | my | girl | |||||||

| ‘my beautiful girl.’ | Serbo-Croatian | ||||||||

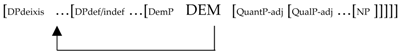

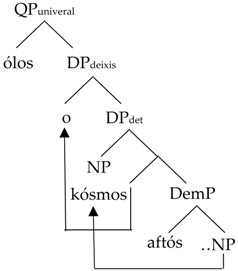

In addition, there are other types of movement to the left periphery. They concern demonstratives, possessives (Genitive DPs, pronouns) and universal quantifiers in Italian, Spanish, Romanian and Greek. In the same vein as Brugè [42,43] we propose that demonstratives occur in two different positions. They externally merge in the high portion of the midfield (unlike Brugè for whom it is in the low portion near NP) and possibly move to DPdeixis, a noun phrase initial position. This is represented in (15).8

| 15. |  |

The pairs of nominal constructions in (16) show that the demonstrative can occur in two positions and, when it is initial, it is in complementary distribution with the definite article.

| 16. | a. | [DP | el | [AgrP-NP | libro | viejo | [DemP | este | [de sintaxis]]]] | |||||

| the | book | old | this | of syntax | ||||||||||

| ‘this old book of syntax.’ | Spanish | |||||||||||||

| a′. | [DPdeixis este [AgrP-NP libro [QualP viejo [de sintaxis]]]] | |||||||||||||

| b. | [DP | fete | [D | le] | [DemP | acestea | [QualP | frumoase ]]] | ||||||

| girls | -the | these | beautiful | |||||||||||

| ‘these beautiful girls.’ | Romanian | |||||||||||||

| b′. | [DPdeixis aceste [AgrP-NP fete [QualP frumoase ]]] | |||||||||||||

| c. | [QP | Sve | [AgrP-NP | lepe | zemlje | [DemP | ove ]]] | |||||||

| all | beautiful | countries | these | |||||||||||

| ‘all these beautiful countries.’ | Serbo-Croatian | |||||||||||||

| c′. | [QP | Sve | [DPdeixis | ove | [AgrP-NP | lepe | zemlje]]] | |||||||

| all | these | beautiful | countries | |||||||||||

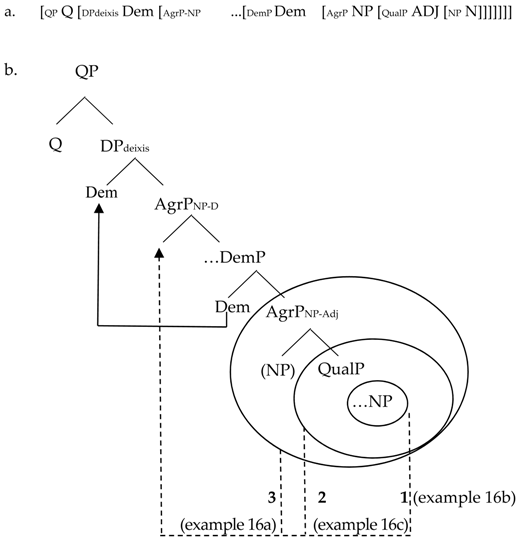

The structures in (17a) and (17b) show that (i) the demonstrative can move from DemP to DPdeixis; (ii) (case 1) the NP alone can move to an agreement position (AgrPNP related to D), which corresponds to example (16b); (iii) (case 2) the QualP including the prenominal adjective and the noun phrase raises to AgrPNP-D (example (16c)) and finally (iv) (case 3) the projection AgrPNP-Adj whose specifier is realized by the raised NP and which includes the adjective-related projection moves to AgrPNP-D (example 16a).

| 17. |  |

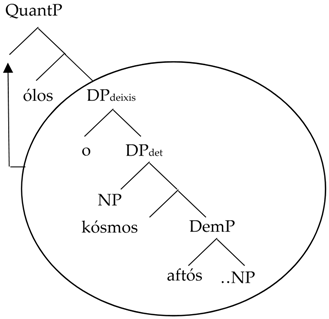

Greek displays even more complex DP-internal transformations involving a universal quantifier, a demonstrative and a definite determiner.9

| 18. | a. | ólos | aftós | o | kósmos | Q < Dem < Det < N | ||

| all | this | the | people(sg) | |||||

| ‘all these people.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *o | aftós | ólos | kósmos | *Det < Dem < Q < N | |||

| the | this | all | people | |||||

| c. | ólos | o | kósmos | aftós | Q < Det < N < Dem | |||

| all | the | people | this | |||||

| d. | o | kósmos | aftós | ólos | Det < N < Q < Dem | |||

| the | people | all | this | |||||

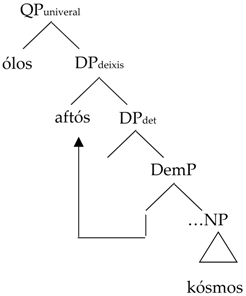

The example (18a) is assigned the structural representation in (19).

| 19. |  |

The tree in (20) corresponding to example (18c) shows that the noun raises as an NP to DPdet, while the determiner moves from Ddet to Ddeixis. As for the demonstrative, it remains in its base position.

| 20. |  |

The structure in (21) holds for the order in (18d). On the basis of the order in (20) there is further pied-piping movement of DPdeixis to the specifier of QuantP, hence the final position of the universal quantifier.

| 21. |  |

One should notice that the reverse prenominal order cannot be derived from any types of movement on the basis of the base order in (20). This constraint is reminiscent of Cinque’s left–right asymmetry (see Section 3).

As in the case of double/multiple complementizers, determiner reduplication provides further evidence in favor of the split-DP structure. Consider first the case of French superlatives, as in (22). We can observe that there is definite determiner doubling.

| 22. | [[DP1 | la | [SuperlP | plus | belle | [DP2 | la | fille | [blonde]]]]] | |

| the | most | beautiful | the | girl | blond | |||||

| ⇒ | [[DP2 | la | fille | [blonde] | [DP1 | la | [SuperlP | plus | belle [DP t]]]] | |

| the | girl | blond | the | most | beautiful | |||||

| ‘the most beautiful blond girl.’ | ||||||||||

Following recent proposals, the projections labeled SuperlP in (22) contains Corver’s DegP [45] and can be identified as Alexiadou’s PredP [46], Kayne’s Small Clause [47], or Cinque’s Reduced Relative Clause [37,48]. Given the derivation in (22) the lower DP2 moves to the specifier of DP1 past the superlative projection. Each D is realized lexically as a definite determiner.10

Romanian also displays determiner doubling, but with two different determiners, namely –ul and ce(l) in (23a–c).

| 23. | a. | mărul | cel | roşu | |

| apple-the | (the) | red | |||

| ‘the red apple.’ | |||||

| b. | studenţii | cei | interesaţi | (de lingvistică) | |

| students-the | (the) | interested | (in linguistics) | ||

| ‘the students interested in linguistics.’ | |||||

| c. | casa | cea | de piatră | ||

| house-the | (the) | of stone | |||

| ‘the house of stone.’ | |||||

The determiner-like element ce(l) can be prenominal in front of quantifier-like prenominal elements (as a last resort strategy according to Cornilescu [49]), as in (24).

| 24. | cele | două legi |

| the | two laws |

The postnominal ce(l) is associated with predicative elements, hence it is involved in a predicative structure (Cornilescu [49] and Cinque [48]; see also Marchis and Alexiadou [50] for an analysis in terms of pseudo-polydefiniteness, Cornilescu and Nicolae [51], Sleeman and Perridon [52], and Sleeman et al. [53] for discussion and references therein).

In Scandinavian (e.g., Norwegian, Swedish) a definite determiner (article) and a definite suffix co-occur only when a prenominal adjective is used.

| 25. | den | *(nya) | bok-en | Swedish |

| the | new | book-the | ||

| ‘the new book.’ | ||||

We assume that den stands in Ddeixis and –en in Ddetermination. The noun plus the adjective (extended NP-movement) moves to the specifier of Ddetermination. The question arises as to why determiner doubling is restricted to the context of prenominal adjective occurrence. The presence of adjectives is a trigger for multiple determiner occurrences in languages like Greek, Romanian and Scandinavian. However, Alexiadou shows that the multiple determiner is not a unified phenomenon crosslinguistically, and this was also the case of the multiple complementizer [46].

Hebrew also displays some sort of determiner reduplication (see Alexiadou [46]), as the example in (26) shows with the use of the prefix ha-.

| 26. | ha-rabanim | ha-fanatim | ha-‘elo |

| the-rabbis | the-fanatic | the-these | |

| ‘these fanatic rabbis.’ | |||

Shlonsky argues that the case in (26) differs from determiner reduplication/spreading in that the reduplicated morpheme ha- is analyzed as an agreement marker rather than a true determiner [54].

Determiner spreading in Greek is a much debated topic in Generative Grammar, especially within the framework of the DP-hypothesis (Alexiadou [46], Alexiadou and Wilder [55], Panagiotidis and Marinis [56]). The split-DP analysis sheds new light on this phenomenon. Consider first some facts. Determiner spreading is only possible with the definite determiner, as shown by the contrast between (27) and (28).

| 27. | a. | to | kókkino | (to) | vivlió | |

| the | red | the | book | |||

| ‘the red book.’ | ||||||

| b. | to | vivlió | (to) | kókkino | ||

| the | Book | the | red | |||

| 28. | a. | ená | kókkino | (*ená) | vivlió | (cf. dialects of German) |

| a | Red | a | book | |||

| ‘a red book.’ | ||||||

| b. | ená | vivlió | (*ená) | kókkino | ||

| a | book | a | red | |||

In addition, determiner spreading in (27), which is not obligatory, is possible with prenominal and postnominal predicative adjectives.11 It is also interesting to point out that determiner spreading can be total or partial. This is illustrated by the examples in (29) taken from Alexiadou and Wilder [55] and Leu [57].

| 29. | a. | to | megálo | to | kókkino | to | vivlió | (total) |

| the | big | the | red | the | book | |||

| b. | to | megálo | to | vivlió | to | kókkino | (total) | |

| the | big | the | book | the | red | |||

| c. | to | megálo | to | kókkino | vivlió | |||

| the | big | the | red | book | (partial) | |||

| ‘the big red book.’ | ||||||||

| d. | to | megálo | kókkino | vivlió | (partial) | |||

| the | big | red | book | |||||

However, not all partial combinations are permitted given the ungrammaticality of (30).

| 30. | a. | *to | megálo | kókkino | to | vivlió |

| the | big | red | the | book | ||

| b. | *to | vivlió | to | megálo | kókkino | |

| the | book | the | big | red | ||

| c. | *to | vivlió | megálo | to | kókkino | |

| the | book | big | the | red | ||

| d. | *to | megálo | to | vivlió | kókkino | |

| the | big | the | book | red | ||

On the basis of these facts we propose that determiner spreading is a phenomenon of the left periphery involving Ddet-to-Ddeix movement (see (31)) through the head of Modifier Projections whose specifier is occupied by the prenominal fronted adjective (see (32)). Such movement may leave possible spelt-out copies of the raised determiner and the chain of copies cannot be broken, as shown by the ungrammaticality of (30) (see Larson and Yamakido [58,59] for a similar analysis in terms of spell out of D-copies).12

| 31. |  |

| 32. | a. | [DP1 | to | [ModifP | megálo | to | [ModifP | kókkino | to | [DP2 | vivlió | [D | |

| b. | [DP1 | to | [ModifP | megálo | (to) | [ModifP | kókkino | (to) | [DP2 | vivlió | [D | ||

The analysis of the example (29b) is quite complex: the adjective of size moves to the left-peripheral ModifP, the noun to a topic position within DP and the adjective of color to a focus or Modif position. This is represented in (33).

| 33. | [DP1 to [ModifP megálo to [TopP vivlió to [FocP/ModifP kókkino ] [DP2 [D |

A question arises from the impossibility of determiner spreading with indefinites in Greek contrary to some German/Swiss dialects and Northern Swedish (e.g., ein ganz ein guete Wi ‘a totally a good wine’, en store n kar ‘a big a man’, examples drawn from Alexiadou [46] (pp. 96–97). Again, this contrast shows that “multiple determiner” is not a uniform phenomenon crosslinguistically.13

So far, we have observed some structural and derivational parallelism in terms of split-C/split-D, Fin-to-Force/Ddet-to-Ddeix-movement and complementizer/determiner doubling and spreading. However, there are differences in the occurrence and inner configuration of discourse-related projections between the CP and DP layer, and the CP-domain is richer than the DP-domain in terms of information structure.

2.3. vP/ nP and Their Left Periphery

vP and nP are the thematic domain of the clause and of the noun phrase, respectively. Arguments externally merge in this domain according to the following Universal Thematic Hierarchy14 (Grimshaw for the clause [61], Jackendoff [62], Baker [63]) and Universal Thematic Assignment hypothesis (Baker [64]).

| 34. | (POSS >) AGENT > (EXPER) > BENEF > THEME/PATIENT > LOCATION |

Right above the thematic domain, there are focus and topic projections at the left-border of vP (Belletti [65,66], Lahousse et al. [67]) and possibly nP (Laenzlinger [24], Samek-Lodovici [38]). As far as the clause is concerned, the right periphery (Nachfeld) looks like (35).

| 35. | …[TopP Top15 [FocP Foc [vP Agent [VP Beneficiary V Theme/Patient]]]] |

As for the noun, deverbal and agent-related nouns (destruction, gift, picture, painting, etc.) are particularly relevant to the hierarchy in (34) (e.g., the bankAgent’s gift of moneyTheme to the poorBeneficiary). As proposed by Laenzlinger [10,11], the left periphery of NP is also the locus of a focus position and a predicative projection. In (36a) the right-hand focalized adjective occurs in the low focus position, and the predicative participial adjective in (36b) occupies the specifier of a low predicative projection (or reduced RC). The noun and the other adjectives/adjuncts are situated at Spell-Out in positions higher than FocP/PredP and the NP-domain (see Section 3.2 for details).

| 36. | a. | une | voiture | italienne | rouge | [FocP | (vraiment | resplendissante) | /SPLENDIDE | [NP ]] |

| a | car | Italian | red | (really | resplendent) | /SPENDID | ||||

| ‘a SPLENDID red Italian car (really resplendent).’ | ||||||||||

| b. | une | voiture | rouge | De sport | [PredP | toute | équipée | [NP ]] | ||

| a | car | red | of sport | all | equipped | |||||

| ‘a red sport car all equipped.’ | ||||||||||

As for arguments, they leave the domain where they externally merge to reach dedicated positions where their case- and ϕ-features as well as their information structural features can be valued. This is expressed in the full nP/vP evacuation principle in (37).16

| 37. | Full nP/vP evacutation principle: “All arguments must leave the vP (and nP) domain in order to have their A-features (i.e., Case and ϕ) and I-features (i.e., informational features such as top, foc) checked/matched/assigned/valued in the overt syntax.” [69] (p. 19); [10] |

Laenzlinger [24] proposes that the information structural features are parasitic on Case/Agreement features in the Mittelfeld and are realized on dedicated heads/projections in the left and right periphery (Rizzi [25,29], Belletti [65,66]). Within the same framework it is argued that verb raising is realized as (possibly extended) vP-movement and noun raising as (possibly extended) nP-movement. Since the arguments have evacuated the vP/nP domain, such movement is an instance of remnant movement. Recall that head movement is very local and limited to V to v, N to n, Fin to Force, and Ddet to Ddeix.

3. The Midfield: The Order Among Complements and Adjuncts

In Section 1 we have introduced Cinque’s [28] left–right asymmetry schematized as (38).

| 38. | a. | okAB(C) H° |

| b. | *(C)BA H° | |

| c. | okH° AB(C) | |

| d. | ok H° (C)BA | |

We will test the validity of this asymmetry for portions of the Midfield of the clause, where the head H° in (38) corresponds to the verb (V), and, similarly, for portions of the noun phrase, where H° corresponds to the noun (N).

On the basis of (38), Cinque accounts for Greenberg’s Universal 20 involving the respective orderbof demonstratives, numerals and adjectives in pre- and postnominal position [70]. Given the base order in (39) realized in English (no NP-movement), it is possible to have the same linear postnominal order in (40) realized in Kîîtharaka, a Bantu language. This order results from successive NP-movement past the demonstrative, the numeral and the adjective. In Gungbe (example (41) from Aboh [27]) the postnominal order of Dem, Num and Adj is the mirror-image one of the prenominal order in English (39). This order is obtained after successive pied-piping roll-up movement (Cinque [70] (p. 324)). Leaving aside some other postnominal possible orders, the prenominal sequence in (42) is not attested crosslinguistically. In fact, without NP-movement, there is no way to derive such a prenominal reverse order from the base order in (39).

| 39. | Dem > | Num > | Adj > | N | ||||

| these | five | nice | cars | |||||

| 40. | N > | Dem > | Num > | Adj | (NP-movement) | |||

| i-kombe | bi-bi | bi-tano | bi-tune | |||||

| 8-cup | 8-this | 8-five | 8-red | |||||

| ‘these five red cups.’ | Kîîtharaka, Bantu | |||||||

| 41. | N > | Adj > | Num > | Dem | ||||

| àgásá | ɖàxó | àtɔ̀n | éhè | lɔ́ | lέ | |||

| crabs | big | three | dem | det | nb | |||

| ‘these three big crabs.’ | Gungbe | |||||||

| 42. | *Adj > Num > Dem > N | |||||||

Another illustration of Cinque’s left–right asymmetry within the noun phrase is adjective ordering in pre- and postnominal contexts. The sequence of adjectives in Germanic illustrated in (43) for English is considered the basic one. The postnominal order of adjectives in (44) is linearly the same as in the prenominal order in (43). This order is attested in Romance and Gaelic and results from NP-movement past the adjectives. The examples of French (Romance) and Hebrew in (45), which contain adjectives of different types, display the reverse order of postnominal adjectives as compared to the basic prenominal order in (43). Such an order results from pied-piping roll-up movement (extended NP-movement, see Laenzlinger [11], Shlonsky [54] for details). As in the case of (42), the reverse order of prenominal adjectives with respect to the basic order in (43) is not possible unless the first adjective is focalized (‘These are black small dogs, but not white ones’). In the absence of NP-movement, this order cannot be derived. The case of adjective focalization results from movement of the adjective to a left-peripheral focus position (see Section 2.2).

| 43. | Adj1 > Adj2 > N | Germanic | |

| red American car | |||

| 44. | N > Adj1 > Adj2 | |||||

| a. | un | vase | ovale | chinois | ||

| a | vase | oval | Chinese | |||

| ‘an oval Chinese vase.’ | Romance (French) | |||||

| b. | cupán | mór | cruinn | |||

| cup | large | green | ||||

| ‘a large green cup.’ | Irish (see also Welsh) | |||||

| 45. | N > Adj2 > Adj1 | |||||

| a. | une | voiture | américaine | rouge/splendide | ||

| a | car | American | red/splendid | French | ||

| ‘a splendid red American car.’ | ||||||

| b. | para | švecarit | xuma | |||

| cow | Swiss | brown | ||||

| ‘a Swiss brown cow.’ | Hebrew | |||||

| 46. | *Adj2 > Adj1 > N unless Adj2 is focalized |

| (These are BLACK small dogs, not white ones.)17 |

Let us now consider whether the left–right asymmetry in (38) holds for the distribution of complements and adjuncts around the verb within the clause (Section 3.1) and the noun within the noun phrase (Section 3.2).

3.1. The Clause

Cinque proposes the universal hierarchy of adverbs in (47) [22].

| 47. | [Frankly/Franchement Moodspeech act > [unfortunately/malheureusement Moodevaluative > [apparently/apparemment Moodevidential > [probably/probablement Modepistemic > [once/autrefois Tpast > [then/ensuite Tfuture> [maybe/peut-être Mod(ir)realisis > [necessarily/nécessairement Modnecessity > [possibly Modpossibility > [deliberately/intentionnellement Modvolitional > [inevitably/inévitablement Modobligation > [cleverly/intelligemment Modability/permission > [usually/habituellement Asphabitual > [again/de nouveau Asprepetitive > [often/souvent Aspfrequentative > [quickly/rapidement Aspcelerative> [already/déjà Tanterior > [no longer/plus Aspperfect > [still/encore Aspcontinuative > [always/toujours Aspperfect > [just/juste Aspretrospective > [soon/bientôt Aspproximative > [briefly/brièvement Aspdurative > [typically/typiquement Aspgeneric/progressive > [almost/presque Aspprospective > [completely/complètement AspSgCompletive(I) > [all/tout AspPlCompl > [well/bien Voice > [fast/vite Aspcelerative(II) > [completely/complètement AspSgCompletive(II) > [again/de nouveau Asprepetitive(II) > [often/souvent Aspfrequentative ]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]] |

Cinque explicitly points out that there should be DP/PP-related positions among (some classes) of adverbs for verb’s complements [22]. Along the same lines, Laenzlinger [24,71,72] argues in a crosslinguistic study that the verb and its arguments can float among adverbs depending on Case and Information Structure conditions. For instance, in French the participial verb and its direct complement can occur before or after a temporal adverb and a manner adverb. This is illustrated in (48).18

| 48. | Jean | a | probablement | fini | dernièrement (fini) | son travail | soigneusement | (fini) | (son travail) |

| Jean | has | probably | achieved | recently | his work | carefully |

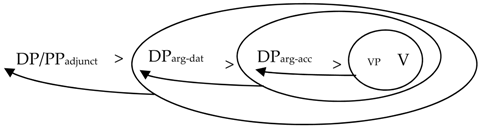

In addition, there is a hierarchy of Case- and P-related positions in the Mittelfeld for DP/PP-complements and DP/PP-adjuncts (Cinque [28], Kayne [73], and Krapova and Cinque [74]). Recall that all arguments left their thematic domain to reach dedicated position in the Mittelfeld. As for adjuncts, they externally merge in the midfield according to the hierarchy proposed by Krapova and Cinque [74,75] and expressed in Cinque [23] as (49).

| 49. | DP time > DP location > … > DP instrument >… > DP manner > … > DP agent > DP goal > DP theme > V (Cinque [23] (p. 10)) |

In order to know whether there is a hierarchy of Case and P-related positions in the midfield, we have to take into consideration Case-marking languages with V-final configurations like German or Japanese (Soare [34], Laenzlinger [24,71]). The German sentences in (50a–c), which display the neutral order of constituents, show that the manner PP-adjunct most naturally precedes the verb’s complements and the Dative complement precedes the Accusative complement which gives rise to the midfield neutral preverbal order in (51) (see Laenzlinger [71], and Pittner [76]).

| 50. | a. | Hans | hat | aus | Großzügigkeit | seinem | Bruder | Geld | geschickt. | |||||||||||||

| Hans | has | by | generosity | his-DAT | brother | money | sent | |||||||||||||||

| ‘Hans sent money to his brother with much generosity’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Die | Bank | hat | kürzlich | aus | Großzügigkeit | den | Armen | Geld | gegeben. | ||||||||||||

| The | Bank | has | recently | by | generosity | the-DAT | poor | money | given | |||||||||||||

| ‘The bank recently gave money to the poor with much generosity’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | Hans | hat | mit | viel | Spaß | seinem | Bruder | ein/dieses | Geschenk | gesendet. | ||||||||||||

| Hans | has | with | much | pleasure | his-DAT | brother | a/this | gift | sent | |||||||||||||

| ‘Hans sent a/this gift to his brother with much pleasure’ | Laenzlinger [71] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 51. | [DP/PPadjunct < DPDat < DPAcc < V] |

In V-initial contexts (SVO), where adjuncts and complements follow the verb, as in French and English, the neutral order of constituents is the mirror-image of the order in (50/51) (see Cinque [77], Schweikert [78], Tescari Neto [79] for relevant discussion).19 This is illustrated in (52) and represented in (53).

| 52. | a. | La banque a récemment donné de l’argent aux pauvres avec une grande générosité. |

| b. | The bank recently gave some money to the poor with great generosity. | |

| 53. | [V < DPAcc < DPDat < PPadjunct]20 |

The reverse order in (52) is obtained after successive roll-up derivation giving rise to “snowballing” effects. This is represented in (54) in a simplified way. After the Acc- and Dat-arguments have evacuated vP and reached their Case-related position, the verb raises cyclically, first as vP past the Acc-argument, then as the extended projection containing the verb and its Acc-object past the Dat-object and finally as the extended projection containing the verb and two object arguments past the PP-adjunct position which merges in a position higher than the objects, hence the “snowballing” effect.

| 54. |  |

As such, this is a (partial) illustration of Cinque’s [23,28] left–right asymmetry in natural language applied to the Mittelfeld’s neutral order (Adjunct OV vs. VO Adjunct).

To summarize, the possible types of movement that apply to the clausal internal structure are given in (55).

| 55. | Once the arguments evacuated from vP, the verb alone can undergo remnant (possibly extended) vP-movement. As further steps, the verb and its extended projection can undergo pied-piping movement of two types: whose-picture (Spec-head, i.e., [V + Adv]) or picture of whom (Head-Compl, i.e., [ Adv + V]). If pied-piping movement is successive, roll-up effects are obtained (snowballing). |

3.2. The Noun Phrase

As in the case of adverbs within the clause, there is a hierarchy of adjectives within the noun phrase. Following Cinque [4], Laenzlinger [10,11,24], and Scott [80], the simplified hierarchy can be established in (56) for event-denoting nouns and (57) for object-denoting nouns Laenzlinger [11] (p. 650).

| 56. | Adjspeaker-oriented > Adjsubject-oriented > Adjmanner > Adjthematic |

| ‘the probable clumsy immediate American reaction to the offense’ |

| 57. | Adjquantification > Adjquality > Adjsize > Adjshape >Adjcolor > Adjnationality |

| ‘numerous wonderful big American cars’ | |

| ‘various round black Egyptian masks’ |

Cinque provides a more fine-grained hierarchy with dual positions for direct/indirect adjectival modifiers [37] (see also Sproat and Shih [81,82], Larson [83]) and the possible position for the noun in Germanic and Romance. See (58) and Table 1.

| 58. | a. | English: AP in a reduced RC > direct modification AP > N > AP in a reduced RC |

| b. | Italian: direct modification AP > N > direct modification AP > AP in a reduced RC | |

Table 1.

APs in reduced RCs vs. APs in direct modification.

This paper is not only concerned with adjective ordering and positioning, but also with the respective order of complements and adjuncts before and after the noun.21

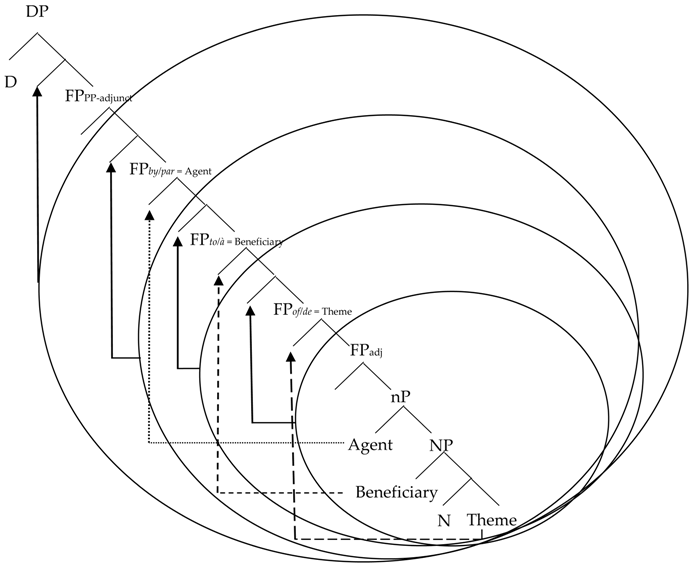

The order of DP/PP-complements/arguments and adjuncts is tested with deverbal nouns since they overtly express a thematic and Case-hierarchy. We first consider N-final languages like Japanese and Tatar which display neutral order of prenominal elements, as illustrated in (59) and represented in (60).

| 59. | Japanese (=Tatar, a head-final Turkic language) | ||||||||||||||

| a. | kooseinoo | bakudan-de-no | Amerikajin | niyoru | machi-no | yôshanai | hakai | ||||||||

| high-tech | weapon-with-GEN | American | by | city-GEN | brutal | destruction | |||||||||

| ‘the destruction of the city by the Americans with high-tech weapons’ | |||||||||||||||

| b. | ginkô | niyoru | mazushii | hito | e no | okane-no | kandaina | kifu | |||||||

| bank | by | poor | people | to-DAT | money-GEN | generous | gift | ||||||||

| ‘a generous gift of money to the poor by the bank’ | |||||||||||||||

| 60. | PPadjunct > PPargument > DPDative > DPGenitive > Adjectives > N | Japanese and Tatar (unmarked/neutral order) |

The nominal constructions in French and English given in (61a–d) show that the neutral linear order of postnominal elements is the mirror-image of the prenominal order in (60), as represented in (62).

| 61. | a. | the brutal destruction of the city by the enemy with heavy artillery |

| b. | la destruction brutale de la ville par l’ennemi avec de la grosse artillerie | |

| c. | a recent gift of money to the poor by the bank with great generosity | |

| d. | le don récent d’argent aux pauvres par la banque avec/d’une grande générosité | |

| 62. | of/de (GEN) < to/à (DAT) < by/par (OBL) < PPAdjunct |

Given the base order in (60), the nominal structure in (62) contains a hierarchy of PP-related projections22 in the Mittelfeld between the DP-border and the adjective-related projections. The unmarked sequences of PPs in (61a–d) are derived from successive roll-up movement, as schematized in (63). More precisely, as a first step the arguments leave the nP-domain and move to their dedicated argumental PP-related position (FPby > FPto > FPof). The adjective-related projection which contains the adjective and the noun undergoes successive roll-up movement through PP-related projections and reaches a position higher than that of the PP-adjunct.

| 63. |  |

So far, the higher part of the French Mittelfeld has been made of the following sequence of PPs: (recursive) de-phrase < à-phrase < par-phrase. Such an order can be refined if we take the co-occurrence of de-PPs into consideration, as exemplified in (64) (see Laenzlinger [10] for a thematic hierarchy of PP-positions in the French noun phrase).23

| 64. | a. | le | tableau | d’Aristote | de ce collectionneur | par Rembrandt | (d’une grande beauté) | ||||||||||||

| the | painting | of Aristote | of this collector | by Rembrandt | (of great beauty) | ||||||||||||||

| ‘This collector’s painting of Aristote by Rembrandt (of great beauty).’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| b. | le | tableau | de Rembrandt | du Louvre | (d’une grande beauté) | ||||||||||||||

| the | painting | of Rembrandt | from the Louvre | (of great beauty) | |||||||||||||||

| ‘Rembrandt’s painting from the Louvre (of great beauty).’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| c. | l’ordre | de départ | du général | à ses troupes | (par le général) | avec fermeté | |||||||||||||

| the order | of departure | of the general | to his troops | (by the general) | with strictness’ | ||||||||||||||

| d. | la promesse | de bonté | de Jean | à l’Eglise | (avec sincérité) | ||||||||||||||

| the promise | of kindness | of Jean | to the Church | (with sincerity) | |||||||||||||||

| ‘Jean’s promise of kindness to the Church (with sincerity).’ | |||||||||||||||||||

| e. | l’envoi | d’une lettre | à Marie | de Paris | par Jean | (avec amour) | |||||||||||||

| the sending | of a letter | to Marie | from Paris | by Jean | (with love) | ||||||||||||||

The unmarked orders of postnominal complements realized in these examples show that co-occurring de-PPs are (preferably) used according to the linear series of PPs in (65).

| 65. | D < N < de-Theme < de-Agent < à-Goal < de-Source < par-Agent < Adjunct |

This order is derived from successive roll-up movement steps that apply to the midfield structure in (66), which gives rise to the mirror-image order (see also 63 above for some details in terms of derivation).

| 66. | DP > FPpp [ADJUNCT] > FPpar [AGENT] > FPde [SOURCE] > FPà [GOAL] > FPde [AGENT] > FPde [THEME] > …n/NP (see Laenzlinger [24,71]) |

Scrambling/reordering of postnominal elements is always possible as a marked option. These alternative orders involve subtle information structural effects, as for instance in French:

| 67. | a. | l’envoi | par Jean | d’une lettre | à Marie | de Paris | avec amour |

| the sending | by John | of a letter | to Mary | from Paris | with love | ||

| b. | l’envoi | à Marie | d’une lettre | par Jean | avec amour | ||

| the sending | to Mary | of a letter | by John | with love | |||

This is a case of DP-internal scrambling, probably an instance of single XP-movement and is similar to CP/TP-internal scrambling of arguments/complements (German, Japanese, French).

So far, the possible types of movement within the noun phrase are summarized as (68).

| 68. | The noun alone can undergo remnant (possibly extended) nP/NP-movement. Then, the noun and its extended projection can undergo pied-piping movement of two types: whose-picture (Spec-head, i.e., N + Adj) or picture of whom (Head-Compl, i.e., Adj + N). If pied-piping movement is successive, roll-up effects are obtained (snowballing). |

Thus, we can observe that both the clause and the noun phrase display the same types of movement (compare (68) with (55)), although their application is not strictly parallel due to structural differences, especially in the midfield and the left periphery.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have offered a cartographic study of the left periphery, the midfield and, to a lesser extent, the Nachfeld (thematic domain and its left periphery) of both the clause and the noun phrase in several languages of different families (Romance, Germanic, Slavic, Greek, etc.). We have seen that Cinque’s left–right asymmetry holds for different parts of the clausal and nominal structure, especially concerning the order of adjuncts and arguments in the midfield, on the basis of a comparison between head-final and head-initial configurations. The so-called parallelism between the clause and the noun concerns (i) the division of both the clausal and nominal structures into three parallel domains and (ii) the possible types of movement (short head-movement, single XP-movement, remnant movement and pied-piping movement). However, there are differences in the conditions of application on some of these movement types between the clause and the noun phrase. More precisely, the derivational steps of vP and nP movement proceed differently due to Case and agreement properties. This is also the case for possible derivations involving complements/arguments within the clause and the noun phrase.

In addition, we have observed that the left periphery as well as the midfield of the clause and the noun phrase show significant differences (i.e., non-parallelism) in their internal organization involving the respective distribution of adverbs/adjectives,24 DP/PP-arguments and DP/PP-adjuncts. More precisely, we have seen that the left periphery is richer, or more developed, in terms of structures and discourse properties in the clause than in the noun phrase. This is attributed to the fact that the noun phrase has a less direct access to the discourse context being usually embedded within the clause.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the editors of the present issue of Languages and the four anonymous reviewers for their relevant comments and suggestions concerning the form and content of the paper. Many thanks go to my colleagues for their empirical and theoretical support: Goljian Kacheava, Eric Haeberli, Genoveva Puskas, Gabriela Soare, Luigi Rizzi, Ur Shlonsky, Giuliano Bocci, and Richard Zimmerman.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Lees, R.B. 1960. The Grammar of English Nominalizations. Bloomington, IN, USA: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. 1970. Remarks on Nominalization. In Readings in English Transformational Grammar. Edited by R.A. Jacobs and P.S. Rosenbaum. Waltham, MA, USA: Ginn, pp. 184–221. [Google Scholar]

- Abney, S. 1987. The English Noun Phrase in Its Sentential Aspect. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. 1994. On the evidence for partial N movement in the Romance DP. In Paths Towards Universal Grammar. Edited by G. Cinque, Koster, J.-Y. Pollock, L. Rizzi and R. Zanuttini. Georgetown, WA, USA: Georgetown University Press, pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, G. 1996. Is there a FocusP and TopicP in the Noun Phrase Structure? Univ. Venice Work. Pap. Linguist. 6: 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, G. 2002. The Functional Structure of Noun Phrases: A Bare Phrase Structure Approach. In Functional Structure in DP and IP. The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by G. Cinque. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, Volume 1, pp. 54–90. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, G. 2006. Parallels in clausal and nominal periphery. In Phases of Interpretation. Edited by M. Frascarelli. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, J. 1993. The Headedness of Noun Phrases: Slaying the Nominal Hydra. In Heads in Grammatical Theory. Edited by G.G. Corbett, N.M. Fraser and S. McGlashan. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 114–139. [Google Scholar]

- Bruening, B. 2009. Selectional Asymmetries between CP and DP Suggest That the DP Hypothesis Is Wrong. Univ. Pa. Work. Pap. Linguist. 15: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Laenzlinger, C. 2005. Some Notes on DP-internal Movement. GG@G 4: 227–260. [Google Scholar]

- Laenzlinger, C. 2005. French Adjective Ordering: Perspectives on DP-internal Movement Types. Lingua 115: 645–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.B. 2001. The DP Hypothesis: Identifying Clausal Properties in the Nominal Domain. In The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Theory. Edited by M. Baltin and C. Collins. Malden, MA, USA: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 536–561. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, A. 1997. No escape from syntax: Don’t try morphological analysis in the privacy of your own Lexicon. Univ. Pa. Work. Pap. Linguist. 4: 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, A. 2001. Adjective syntax and noun raising: Word order asymmetries in the DP as the result of adjective distribution. Stud. Linguist. 55: 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borer, H. 2005. Structuring Sense. In Name Only. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann, K. 2003. Prolific Domains. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltschko, M. 2014. The Universal Structure of Categories: Towards a Formal Typology. Cambridge Studies in Linguistics Series 142; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.K. 1998. On the Double Object Construction. Linguist. Inq. 19: 335–391. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, J.-Y. 1989. Verb movement, UG and the structure of IP. Linguist. Inq. 20: 365–425. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A. 1989. Generalized Verb Movement: Aspects of Verb Syntax. Turin, Italy: Rosenberg & Sellier. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. 1999. Adverbs and Functional Heads: A Cross-linguistic Perspective. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. 2010. Word Order Typology. A Change of Perspective. In Proceedings of the TADWO Conference. Edited by M. Sheehan and G. Newton. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laenzlinger, C. 2011. Elements of Comparative Generative Grammar: A Cartographic Approach. Padova, Italy: Unipress. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L. 1997. The Fine Structure of the Left Periphery. In Elements of Grammar. Edited by L. Haegeman. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 281–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L., and G. Bocci. 2017. The left periphery of the clause—Primarily illustrated for Italian. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Syntax, 2nd ed. Edited by M. Everaert and H.C. Van Riemsdijk. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Aboh, E. 2004. Topic and Focus within D. Linguistics in The Netherlands 21: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. 2013. Cognition, universal grammar, and typological generalizations. Lingua 130: 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, L. 2001. On the position “Int(errogative)” in the left periphery of the clause. In Current studies in Italian syntax. Essays offered to Lorenzo Renzi. North-Holland Linguistic Series 59; Edited by G. Cinque and G. Salvi. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier, pp. 287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, L. 2004. Locality and the left periphery. In Structures and Beyond. The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by A. Belletti. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, Volume 3, pp. 104–131. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, J. 2006. Questions and questioning in a local English. In Crosslinguistic Research in Syntax and Semantics. Edited by R. Zanuttini. Washington, DC, USA: Georgetown University Press, pp. 87–123. [Google Scholar]

- Villa-García, J. 2012. Recomplementation and locality of movement in Spanish. Probus 24: 257–314. [Google Scholar]

- Paoli, S. 2007. The Fine structure of the left periphery: COMPs and subjects; evidence from Romance. Lingua 117: 1057–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soare, G. 2009. The Syntax-Information Structure Interface and Its Effects on A-Movement and A’-Movement in Romanian. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Puskás, G., and T. Ihsane. 2001. Specific is not Definite. GG@G 2: 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsane, T. 2008. The Layered DP: Form and Meaning of French Indefinites. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. 2011. The Syntax of Adjectives. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Samek-Lodovici, V. 2010. Final and non-final focus in Italian DPs. Lingua 120: 802–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horroks, G., and M. Stravou. 1987. Bounding Theory and Greek syntax: Evidence from wh-movement in NP. J. Linguist. 23: 79–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntelitheos, D. 2002. Possessor Extraction and the Left Periphery of the DP. Unpublished manuscript. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Department of Linguistics, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Szabolcsi, A. 1994. The Noun Phrase. In The Syntactic Structure of Hungarian. Syntax and Semantics Series 27; Edited by F. Kiefer and K.É. Kiss. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press, pp. 179–274. [Google Scholar]

- Brugè, L. 1996. Demonstrative Movement in Spanish: A Comparative Approach. Univ. Venice Work. Pap. Linguist. 6: 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brugè, L. 2002. The Positions of Demonstratives in the Extended Nominal Projection. In Functional Structure in DP and IP: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by G. Cinque. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, Volume 1, pp. 15–53. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, M. 2005. Nominal Phrases from a Scandinavian Perspective. Linguistik Aktuell Series 87; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Corver, N. 1997. Much-support as last resort. Linguist. Inq. 28: 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, A. 2013. Multiple Determiners and the Structure of DPs. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, R. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. Two types of non-restrictive relatives. Presented at Colloque de Syntaxe et Sémantique à Paris, Paris, France, 4–6 October 2007; Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 7. Edited by O. Bonami and P. Cabredo Hofherr. Available online: http://www.cssp.cnrs.fr/eiss7/cinque-eiss7.pdfsp.cnrs.fr/eiss7/cinque-eiss7.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2016).

- Cornilescu, A. 2006. Modes of Semantic Combinations: NP/DP. Adjectives and the Structure of the Romanian DP. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2004. Edited by J. Doetjes and P. Gonzàlez. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins, pp. 43–69. [Google Scholar]

- Marchis, M., and A. Alexiadou. 2008. On the distribution of adjectives in Romanian: The cel construction. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory: Selected Papers from ‘Going Romance’, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 6–8 December 2007. Edited by E. Aboh, E. van der Linden, J. Quer and P. Sleeman. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins, pp. 161–178. [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu, A., and A. Nicolae. 2011. On the Syntax of Romanian Definite Phrases: Changes in the Patterns of Definiteness Checking. In The Noun Phrase in Romance and Germanic. Structure, Variation, and Change. Edited by P. Sleeman and H. Perridon. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins, pp. 193–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman, P., and H. Perridon. 2011. The Noun Phrase in Romance and Germanic: Structure, Variation and Change. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeman, P., F. Van de Velde, and H. Perridon. 2014. Adjectives in Germanic and Romance. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadephia, PA, USA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Shlonsky, U. 2004. The form of Semitic noun phrases. Lingua 114: 1465–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiadou, A., and C. Wilder. 1998. Adjectival Modification and Multiple Determiners. In Predicates and Movement in the DP. Edited by A. Alexiadou and C. Wilder. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins, pp. 303–332. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotidis, P., and T. Marinis. 2011. Determiner spreading as DP-predication. Stud. Linguist. 65: 268–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, T. 2001. A Sketchy Note on the Article-Modifier Relation: Evidence from Swiss-German which Sheds Light on Greek Determiner Spreading. GG@G 2: 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.K., and H. Yamakido. Zazaki ‘double Ezafe’ as Double Case-Marking. Presented at the Linguistics Society of America Annual Meeting, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 8 January 2006; Available online: https://semlab5.sbs.sunysb.edu/~rlarson/lsa06ly.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2016).

- Larson, R.K., and H. Yamakido. 2008. Ezafe and the Deep Position of Nominal Modifiers. In Adjectives and Adverbs. Syntax, Semantics, and Discourse. Edited by L. McNally and C. Kennedy. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, pp. 43–70. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, A., L. Haegeman, and M. Stravou. 2007. Noun Phrase in the Generative Perspective. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, J. 1990. Argument Structure. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, R.S. 1990. Semantic Structures. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.C. 1997. Thematic Roles and Syntactic Structure. In Elements of Grammar: Handbook of Generative Syntax. Edited by L. Haegeman. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 73–137. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.C. 1988. Incorporation. A Theory of Grammatical Function Changing. Chicago, IL, USA: London, UK: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A. 2001. Inversion as focalization. In Subject Inversion in Romance and the Theory of Universal Grammar. Edited by A. Hulk and J.-Y. Pollock. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, pp. 60–90. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, A. 2004. Aspects of the low IP area. In The Structure of IP and CP. The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by L. Rizzi. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, Volume 2, pp. 16–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lahousse, K., C. Laenzlinger, and G. Soare. 2014. Intervention at the Periphery. Lingua 143: 56–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svenonius, P. 2004. On the Edge. In Peripheries. Syntactic Edges and Their Effects. Edited by D. Adger, C. de Cat and G. Tsoulas. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer, pp. 259–288. [Google Scholar]

- Laenzlinger, C., and G. Soare. 2005. On merging positions for arguments and adverbs in the Romance Mittelfeld. In Contributions to the Thirtieth Incontro di Grammatica Generativa. Edited by W. Schweikert and N. Munaro. Venice, Italy: Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina, pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. 2005. Deriving Greenberg’s Universal 20 and Its Exceptions. Linguist. Inq. 36: 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laenzlinger, C. 2015. Comparative Adverb Syntax: A Cartographic Approach. In Adverbs: Diachronic and Functional Aspects. Edited by K. Pittner. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins, pp. 207–238. [Google Scholar]

- Laenzlinger, C. 2015. The CP/DP (non-)parallelism Revisited. In Syntactic Cartography: Where Do We Go from Here? Edited by U. Shlonsky. Oxford, UK: New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, pp. 128–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, R. 2002. On Some Prepositions that Look DP-internal: English of and French de. Catalan J. Linguist. 1: 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- Krapova, I., and G. Cinque. 2005. On the Order of Wh-phrases in Bulgarian Multiple Wh-fronting. Univ. Venice Work. Pap. Linguist. 15: 171–197. [Google Scholar]

- Krapova, I., and G. Cinque. 2008. On the Order of wh-Phrases in Bulgarian Multiple wh-Fronting. In Formal Description of Slavic Languages: The Fifth Conference, Leipzig 2003. Edited by G. Zybatow, L. Szucsich, U. Junghanns and R. Meyer. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang, pp. 318–336. [Google Scholar]

- Pittner, K. 2004. Adverbial positions in the German middle field. In Adverbials. The Interplay between Meaning, Context and Syntactic Structure. Edited by J.R. Austin, S. Engelberg and G. Rauh. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins, pp. 253–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. Complement and Adverbial PPs: Implications for Clause Structure. In Proceedings of the GLOW 25, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 9–11 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schweikert, W. 2005. The Order of Prepositional Phrases in the Structure of the Clause. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Philadelphia, PA, USA: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Tescari Neto, A. 2013. On Verb Movement in Brazilian Portuguese: A Cartography Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Ca’Foscari University, Venice, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, G.-J. 2002. Stacked Adjectival Modification and the Structure of Nominal Phrases. In Functional Structure in DP and IP: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by G. Cinque. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, Volume 1, pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sproat, R., and C. Shih. 1988. Prenominal adjective ordering in English and Mandarin. NELS 18: 465–489. [Google Scholar]

- Sproat, R., and C. Shih. 1991. The cross-linguistic distribution of adjective ordering restrictions. In Interdisciplanary Approaches to Language. Essays in Honor of S. Y. Kuroda. Edited by C. Georgopoulos and R. Ishihara. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 565–593. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R.K. 1998. Events and modification in nominals. In Proceedings from Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) VIII. Edited by D. Strolovitch and A. Lawson. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press, pp. 145–168. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, J.-C. 1982. Ordres et Raisons de la Langue. Paris, France: Le Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Ruwet, N. 1972. Théorie Syntaxique et Syntaxe du Français. Paris, France: Le Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, G. 1980. On Extraction from NP. J. Ital. Linguist. 5: 47–99. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See also work in the framework of Distributed Morphology (Marantz [13], Alexiadou [14]) where the parallelism between clauses and derived nominals is also striking (the category of the root is defined syntactically, i.e., syntax feeds the lexicon, see also Borer’s [15] exo-squeletal lexical approach). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | In this context it is important to make a distinction between event-denoting nouns (deverbal/derived nominals) and object-denoting nouns as well as between state-denoting and event-denoting verbs. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | A cleft construction is used for arguments as shown by the contrast between (ia) and (ib).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The celerative adverb lentement ‘slowly’ externally merges in a position lower than the modal projection hosting the adverb probably. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | A similar analysis can be adopted for subjunctive clauses in languages like Greek and Romanian where a subjunctive marker co-occurs with the higher complementizer. The latter merges in Force, while the former merges in Fin which is a mood-related head (see Soare [34] for Romanian). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Note that Saxon Genitive is restricted to [+animate] nouns in German, as compared to English.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | As regards DP/PP-adjuncts, their fronting to the left periphery is very restricted in the languages studied in this paper. A case in point is Russian where a few PP-adjuncts can move to the DP-domain as a contrastive (focus) effect. This is illustrated in (v) and (vi) below.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | See also Julien [44] for a similar proposition, but also Bernstein [12] who argues against Brugè’s analysis. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Note that the prenominal raised demonstrative is compatible with a definite determiner in Greek contrary to Spanish and Romanian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | There are alternative analyses in terms of N(P)-ellipsis or postnominal predication (see Alexiadou [46] (pp. 68ff) and references cited therein). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Determiner Spreading is not possible with non-predicative adjectives such as alleged, Italian and with adjectives selecting a complement like proud of his son N (see Alexiadou and Wilder [54], Cinque [37,48], Laenzlinger [24] and Alexiadou [46]). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | There are alternative proposals in the literature, especially in terms of Reduced Relative Clause or Small Clause (Alexiadou and Wilder [55] on the basis of Kayne [47], Cinque [37,48]; see Alexiadou [46] for a review). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | As suggested by an anonymous reviewer, this difference may be due to the fact that indefinites are quantifiers, not articles, in Greek (see Laenzlinger [24] (p. 178) for a similar proposal). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | See the references cited in Alexiadou et al. [60] (pp. 503ff) for the thematic hierarchy within the noun phrase. This analysis in terms of NP-internal thematic hierarchy has been challenged by Grimshaw [61] among others. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | TopP is higher than FocP, as shown by the following contrast:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | This principle is based on the fact that nP and vP are phases (see Svenonius [68], Cornilescu and Nicolae [51]) and their arguments must move to an edge position to be accessible for Agree (to be probed). This position is externally to nP and vP given Kayne’s Linear Corresponding Axiom [47] (nP and vP cannot have more than one specifier). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | However, there are limits to such mirror-ordering of adjectives under focalization, as shown by the contrast between (i) and (ii).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | This also holds in other Romance languages (e.g., Italian) and more restrictively in English (as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer). See Laenzlinger [24] for a large comparative study of adverb intervention. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | This is similar for the noun phrase (Laenzlinger [24] and see also Section 3.2).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||