Discourse Markers in French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) Dialogues and Their Translation into French: A Corpus-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Overview of Discourse Markers in Signed Languages

“et in French is monosemous, that is, it only encodes addition even though it can be pragmatically enriched in context (for instance, to express a consequence). By contrast, same in LSFB is polysemous and encodes addition and comparison, which leads to other meanings such as alternative”

2.2. Discourse Marker Models Used in Signed Language Research

2.3. Discourse Markers and Translation

3. Methodology

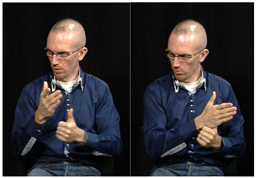

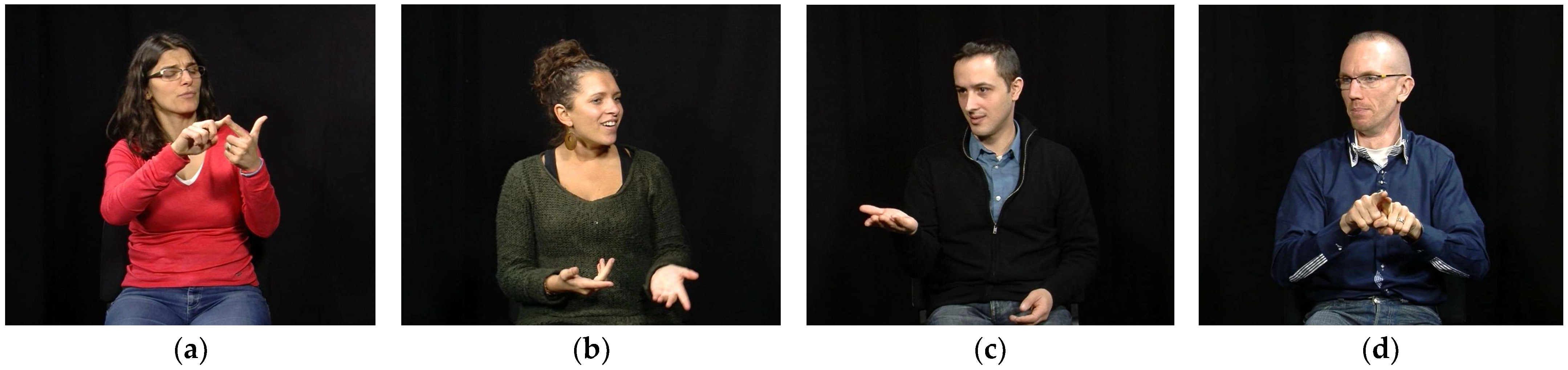

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Identification of Discourse Markers and Annotation

“a grammatically heterogeneous, syntactically optional, multifunctional type of pragmatic markers. Their specificity is to function on a metadiscursive level as procedural cues to constrain the interpretation of the host unit in a co-built representation of on-going discourse. They do so by either signaling a discourse relation between the host unit and its context, expliciting the structural sequencing of discourse segments, expressing the speaker’s meta-comment on their phrasing, or contributing to the speaker-hearer relationship.”

- Type_DM: This is a parent tier used to annotate whether the DM was manual, nonmanual, spatial, or a combination without any a priori distinction between the different possibilities.

- Articulators_DM: This is a child tier of the Type_DM tier used to annotate the specific articulators that produced the DM. When several articulators (of any type) were used, they were annotated in the same line and separated by “+”.

- Domain_DM: This is a child tier of the Type_DM tier used to annotate the domain attributed to the DM. A controlled vocabulary with the four possible domains (i.e., ideational, rhetorical, sequential, and interpersonal, see Section 2.2) was created and associated with this tier.

- Function_DM: This is a child tier of the Type_DM tier used to annotate the function attributed to the DM. A controlled vocabulary with the fifteen possible functions (addition, agreeing, alternative, cause, concession, condition, consequence, contrast, disagreement, hedging, monitoring, quoting, specification, temporal, and topic, see Section 2.2) was created and associated with this tier.

- Translation_DM: This is a child tier of the Type_DM tier used to annotate whether the DM was translated as another DM in French (in which case the DM in French was copied from the translation tier) or not (NO-DM).3

- Comment_DM: This is a parent tier in which comments related to any of the previous tiers were introduced, if necessary.

4. Results

4.1. Types of Discourse Markers in LSFB

| Example (1)—CLSFB2703_S056_00:01:15.655–00:01:21.192 | |||||

|  |  |  |  |  |

| pt:loc | ecole | integration | bien | ami | parler |

| pt:loc | school | integration | good | friend | speak |

|  |  |  |  |  |

| bien | mais | soir | savoir | aller | parents |

| good | but | evening | know | go | parents |

|  |  | |||

| avoir | sl | la-bas | |||

| have | sign-language | there | |||

| ‘When I was integrated into a mainstream school, it was good because I could speak with my friends. However, when I went home in the afternoon, I knew I could sign with my parents.’ | |||||

| Example (2)—CLSFB2703_S055_00:02:55.696–00:03.00.960 | |||||

|  |  |  |  |  |

| pt:pro1 | famille | palm-down | sourd | palm-down | ami |

| pt:pro1 | family | palm-down | deaf | palm-down | friend |

|  |  |  |  |  |

| sourd | palm-up | ami | entendant | oui | ecole |

| deaf | palm-up | friend | hearing | yes | school |

|  |  |  | ||

| pt:loc | avoir | plusieurs | entendants | ||

| pt:loc | have | several | hearing | ||

| ‘I had my family, whose members are deaf, but I didn’t have deaf friends. I had hearing friends, I had some hearing friends at school.’ | |||||

| Example (3)—CLSFB2315_S048_00:01:08.861–00:01:18.051 | |||||

|  |  |  |  |  |

| home | avant | habiter | grotte | dans | suivre |

| man | before | live | cave | inside | follow |

|  |  |  |  |  |

| manger | avant | chase | animal | fleche | ds:lancer-fleche |

| eat | before | hunt | animal | arrow | ds:throw-arrow |

|  | ||||

| mange | animal | ||||

| eat | animal | ||||

| ‘One must follow the diet of the men who lived inside caves long ago. They chased animals using arrows and ate these animals.’ | |||||

4.2. Domains and Functions of Discourse Markers in LSFB

| Example (4), ideational domain—CLSFB2315_S048_00:02:05.016–00:02.12.390 | |||||||

| nom | exercice | titre | convenir | mouvement | corps | convenir | exemple |

| name | exercise | title | match | movement | body | match | example |

| utiliser | ds:barre | ds:disque | ds:lever | ||||

| use | ds:bar | ds:disc | ds:lift | ||||

| ‘The exercise consists of body movements. For instance, we lift barbells.’ | |||||||

| Example (5), rhetorical domain—CLSFB2315_S048_00:00:57.797–00:01.00.951 | |||||||

| avoir | dire | titre | developper | dix | titre | dix | point |

| have | say | title | develop | ten | title | ten | point |

| programme | |||||||

| program | |||||||

| ‘There are 10 capacities, so 10 points in the program.’ | |||||||

| Example (6), sequential domain—CLSFB1904_S041_00:03:08.521–00:03.12.606 | |||||||

| pt:pro1 | savoir | oui | palm-up | dependre | niveau | social | variable |

| pt:pro1 | know | yes | palm-up | depend | level | social | variable |

| ‘Yes, I know. In fact, it depends on the social level.’ | |||||||

| Example (7), interpersonal domain—CLSFB1904_S040_00:00:16.653–00:00.25.556 | |||||||

| <S041> | besoin | vie | battre | objectif | vie | avancer | titre |

| need | life | fight | objective | life | advance | title | |

| aussi | developper | <S040> | ca-veut-dire | monde | sourd | toujours | developper |

| also | develop | it-means | world | deaf | always | develop | |

| toujours | |||||||

| always | |||||||

| ‘<S041> [Deaf people] need to fight for their lives so that they can move forward. They sort of need to develop. <S040> So the deaf world is always developing.’ | |||||||

| Example (8)—CLSFB2703_S055_00:02:08.737–00:02:08.971 | ||||||

| pt:pro1 | monde | sourd | oui | c-est | aller | maman |

| pt:pro1 | world | deaf | yes | it-is | go | mother |

| ‘For me, the deaf world was… yeah, when I went with my mum [to the museums].’ | ||||||

| Example (9)—CLSFB2315_S005_00:08:31.024–00.08.31.112 | ||||||

| si | moins | onze | point | jeter | cartes | jeter |

| if | less | eleven | point | throw | cards | throw |

| ‘If they have less than eleven points, they must discard the cards.’ | ||||||

| Example (10)—CLSFB2315_S005_00:05:42.159–00:05:44.880 | |||||

| palm-up | pt:pro1 | adorer | pt:pro1 | two | lbuoy(2):two |

| palm-up | pt:pro1 | love | pt:pro1 | two | lbuoy(2):two |

| ‘So I love two things.’ | |||||

| Example (11)—CLSFB1904_S040_00:00:47.702–00:00:52.406 | ||||||

| <S041> | pt:poss1 | frere | soeur | voir | pt:pro3 | different |

| pt:poss1 | brother | sister | see | pt:pro3 | different | |

| <S040> | palm-up | oui | reserve | pt:poss1 | ||

| palm-up | yes | reserved | pt:poss1 | |||

| ‘<S041> My brother and my sister are different. <S040> That’s it, yes, they are more reserved.’ | ||||||

4.3. Translation of Discourse Markers from LSFB to Written French

| Example (12) | ||||||

| pt:pro1 | monde | sourd | oui | c-est | aller | maman |

| pt:pro1 | world | deaf | yes | it-is | go | mother |

| Il y avait, d’un côté, le monde des sourds. Ø Je me rappelle encore quand j’allais au musée avec ma maman. | ||||||

| ‘There was, on the one hand, the deaf word. Ø I remember when I went to the museum with my mum.’ | ||||||

| Example (13) | |||||

| palm-up | pt:pro1 | adorer | pt:pro1 | two | lbuoy(2):two |

| palm-up | pt:pro1 | love | pt:pro1 | two | lbuoy(2):two |

| Moi, j’adore deux choses. | |||||

| ‘Me, I love two things.’ | |||||

5. Discussion

“The omission of a marker is related to several factors: the marker, and specifically its meaning and domain, the type of relation (e.g., continuous relations favor deletion), cross-linguistic differences (e.g., lack of equivalent, avoiding stylistic awkwardness), and extralinguistic factors such as the translation process per se (not taking the risk of omitting a word if there is no good reason to do so) or even the genre, e.g., subtitling is known to increase the deletion of linguistic material, especially when lexical content is low”.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADD | Addition |

| AGR | Agreeing |

| ALT | Alternative |

| ASL | American Sign Language |

| Auslan | Australian Sign Language |

| CAU | Cause |

| CSS | Concession |

| CND | Condition |

| CSQ | Consequence |

| CTR | Contrast |

| DIS | Disagreement |

| DM | Discourse marker |

| HDG | Hedging |

| IDE | Ideational domain |

| INT | Interpersonal domain |

| LSC | Catalan Sign Language |

| LSE | Spanish Sign Language |

| LSFB | French Belgian Sign Language |

| LSV | Venezuelan Sign Language |

| MNT | Monitoring |

| QUO | Quoting |

| RHE | Rhetorical domain |

| SEQ | Sequential domain |

| SPE | Specification |

| TMP | Temporal |

| TOP | Topic |

Appendix A

| DMs | Domain | Function | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| apres ‘afterward’ (9) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_0bbbb5e7f4b546367645cb39a8a0ebec.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (5), SEQ (4) | TMP (9) | Alors (1), et (1), en fait (1), puis (2) |

| aussi ‘also’ (20) (Also annotated as same in previous studies) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_2690fa781e408c17bf545a82dd6564ea.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (8), RHE (4), SEQ (8) | ADD (7), ALT (1), CAU (1), CSQ (3), HDG (5), SPE (3) | En fait (1), mais aussi (1) |

| autre.part ‘other side’ (3) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_b5a5bd73161f2a5a7b817935a166fb02.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | SEQ (3) | TMP (2), ALT(1) | Puis (1) |

autre.theme ‘another topic’ (1) | SEQ (1) | TOP (1) | ---- |

| c-est-ca ‘that’s it’ (1) (Considered a palm-up instance in previous studies) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_9d09bd4c3c17c7b4167b705134273958.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | INT (1) | AGR (1) | ---- |

| ca-veut-dire ‘it means’ (12) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_903165b2e5be4af9125bbf3b4e571d3e.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (7), RHE (2), SEQ (2), INT (1) | ALT (2), CSQ (2), HDG (1), SPE (7) | Donc (1), en fait (1), mais (1) |

| exemple ‘example’ (7) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_81d50c7ee9c2d2b7a4759856f1d89c1c.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (6), SEQ (1) | SPE (7) | Par exemple (4) |

| gsign (12) (ID-gloss given to non-lexical forms, i.e., gestures. The form illustrated below is also annotated as palm-down in the LSFB Corpus.)  | SEQ (12) | CSQ (1), MNT(9), TOP (2) | Alors (1) |

| juste.f ‘exact’ (with F handshape) (1) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_23a21453add9981318a5ba9afdedd6fc.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | INT (1) | CSQ (1) | ---- |

| lbuoy (30) (Basic ID-gloss for list buoys. It is enriched with information regarding the handshape of the form (which may vary from one to ten extended fingers) and the item in the list referred to.) | IDE (13), SEQ (17) | ADD (20), ALT (1), MNT (2), TOP (7) | En premier lieu (1), en second lieu (1), ensuite (1), et (1), et puis (1) |

| mais ‘but’ (21) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_583411bf97eda607fdb7362e0ce48d6d.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (9), RHE (7), SEQ (4), INT (1) | ALT (2), CCS (15), CTR (3), DIS (1) | Ensuite (1), et (2), mais (4), par contre (1), pourtant (1) |

| meme.y ‘same’ (with Y handshape) (3) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_c16fc7e7d71659703139e8588307bc4a.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | RHE (3) | CCS (3) | ---- |

| ok ‘ok’ (3) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_a01dd0dfdc2a170333015e48485084bb.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | SEQ (2), INT (1) | AGR (1), MNT (1), TOP (1) | D’accord (1), ok (1) |

| ou ‘or’ (2) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_cae822d64c44b1ffccb7582a28f2f187.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (2) | ALT (2) | Ou (1) |

| ou.ou ‘or’ (with O and U handshape) (5) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_349a3bbac257eba9bb5422f17161a79e.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (5) | ALT (5) | Ou (2) |

| oui ‘yes’ (22) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_dcfe3735bcd3701927a539f968a1e033.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | RHE (2), SEQ (9), INT (11) | AGR (13), MNT (6), TOP (3) | Oui (12) |

| palm-up (23) (This ID-gloss is used in English, in line with other corpora.) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_eb04774c23fc5d1dafb28ec8a451e4c5.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (1), RHE (3), SEQ (13), INT (6) | ADD (1), AGR (2), ALT (1), CAU (1), MNT (12), QUO (1), SPE (1), TOP (4) | Bien sûr (1), en fait (1), donc (1) |

| parce-que ‘because’ (8) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_31ca5baeda7a5649210c46681ebef16d.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (2), RHE (5), INT (1) | CAU (8) | Parce que (2) |

| pas ‘not’ (1) (One of the meanings of this sign is ‘finish’.) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_449d733d3827660ab8c4fc19a57edfdd.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | SEQ (1) | CSQ (1) | ---- |

| plus ‘plus’ (3) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_39fdac9a426be976a982b4aca6997e1e.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (1), SEQ (2) | ADD (3) | En plus (2) |

| pourquoi ‘why’ (7) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_180624112e51055fec61454961f1dab7.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | RHE (5), INT (2) | CAU (7) | Mais (1), parce que (1) |

| si ‘if’ (21) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_1f2f4d1dd1067bbc3f3f493677d27870.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (20), RHE (1) | CND (21) | Si (8) |

| suivant ‘next’ (3) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_8778e8a52e72897b02f1566893d84cf5.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | IDE (3) | TMP (3) | Après (1), et ensuite (1) |

| titre ‘title’ (5) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_43d84f6c5780bee88749ee54789b465c.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | RHE (5) | HDG (4), SPE (1) | En gros (1) |

| voila ‘that’s it’ (6) (Considered a palm-up instance in previous studies) https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/img/pictures/signe_f2bb92c924ade837f1c594300be43dfb.gif (accessed on 18 April 2025) | SEQ (2), INT (4) | AGR (3), MNT (2), TOP (1) | Quoi (1) |

Appendix B

| Domains | DMs |

|---|---|

| Ideational | apres, aussi, ca-veut-dire, exemple, lbuoy, mais, ou, ou.ou, palm-up, parce-que, plus, si, suivant |

| Rhetorical | aussi, ca-veut-dire, mais, meme.y, oui, palm-up, parce-que, pourquoi, si, titre |

| Sequential | apres, aussi, autre.part, autre-theme-1h, ca-veut-dire, exemple, gsign/palm-down, lbuoy, mais, ok, oui, palm-up/voila, pas, plus, puffed cheeks |

| Interpersonal | c-est-ca/palm-up/voila, ca-veut-dire, juste.f, mais, ok, oui, parce-que, pourquoi, head nod |

| Function | DMs |

|---|---|

| Addition | aussi, lbuoy, palm-up, plus |

| Agreeing | c-est-ca/palm-up/voila, ok, oui, head nod |

| Alternative | aussi, autre.part, ca-veut-dire, mais, lbuoy, ou, ou.ou, palm-up |

| Cause | aussi, palm-up, parce-que, pourquoi |

| Concession | mais, meme.y |

| Condition | si |

| Consequence | aussi, ca-veut-dire, gsign/palm-down, juste.f, pas |

| Contrast | mais |

| Disagreement | mais |

| Hedging | aussi, ca-veut-dire, titre, puffed cheeks |

| Monitoring | lbuoy, gsign/palm-down, ok, oui, palm-up/voila |

| Quoting | palm-up |

| Specification | aussi, ca-veut-dire, exemple, plus, titre, palm-up |

| Temporal | apres, autre.part, suivant |

| Topic | autre-theme-1h, lbuoy, gsign/palm-down, ok, oui, palm-up/voila |

Appendix C

| Domains | Functions |

|---|---|

| Ideational | Addition (17), alternative (9), cause (5), concession (8), condition (21), consequence (2), contrast (2), specification (16), temporal (8) |

| Rhetorical | Addition (1), agreeing (4), alternative (5), cause (10), concession (8), condition (1), consequence (3), contrast (1), hedging (5), specification (1) |

| Sequential | Addition (17), alternative (2), concession (8), consequence (4), hedging (5), monitoring (28), quoting (1), specification (2), temporal (7), topic (19) |

| Interpersonal | Agreeing (19), cause (3), consequence (1), disagreement (1), monitoring (6), specification (1) |

| 1 | As established by convention, signed language glosses are written in capital letters. A hyphen is used when a gloss is composed of two words, such as palm-up. pt:loc stands for a pointing used with a locative value; pt:pro1 refers to the first-person pronoun, pt:pro3 to the third-person pronoun, and pt:poss1 to the first-person possessive pronoun. ds followed by a colon and a word or multiple words represents a depicting sign. Note also that ID-glosses used in previous research are written in English for ease of readability (cf. note 2). However, ID-glosses are written in French with a translation into English for the results related to this research. This decision was made to allow the reader to consult the DMs in the LSFB lexicon (https://www.corpus-lsfb.be/lexique.php, accessed on 18 April 2025) using the same language (see note 4). |

| 2 | The sign same is the DM aussi (‘also’) in the present research. The two ID-glosses given to this sign previously in English and currently in French reflect some of its possible meanings, namely comparison and addition. |

| 3 | Note that for this initial research on all DMs and their translation into written French, it was not possible to examine the translation in detail. Therefore, NO-DM includes cases where DMs may have been omitted or substituted by other types of linguistic units (e.g., reformulations, phrases, etc.) in the target text. Similarly, no further analysis on whether DMs were translated literally or non-literally, with a more general or specific meaning, was carried out. |

| 4 | The identification codes of LSFB examples, either illustrated with pictures or not, start with the name of the corpus, followed by the session, the task, the signer’s code, and the time code. The ID-glosses are written in French, and their literal translation into English is provided below. A translation of the whole segment of discourse in English is also given between quotation marks. |

| 5 | c-est-ca and voila are considered variants of palm-up, in line with previous studies (e.g., Gabarró-López, 2018, 2019; Lepeut & Shaw, 2022). The three ID-glosses are grouped throughout this paper, but they stand as separate entries in Appendix A so that the reader can grasp the different articulatory variants of palm-up. |

References

- Cartoni, B., Zufferey, S., & Meyer, T. (2013). Using the Europarl corpus for cross-linguistic research. Belgian Journal of Linguistics, 27, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cettolo, M., Girardi, C., & Federico, M. (2012). WIT: Web inventory of transcribed and translated talks. In M. Cettolo, M. Federico, L. Specia, & A. Way (Eds.), Proceedings of the 16th EAMT conference (pp. 261–268). European Association for Machine Translation. [Google Scholar]

- Crible, L. (2017). Discourse markers and (dis)fluency across registers: A contrastive usage-based study in English and French [Ph.D. thesis, Université catholique de Louvain]. [Google Scholar]

- Crible, L., Abuczki, A., Burkšaitiené, N., Furkó, P., Nedoluzhko, A., Rackevičiené, S., Oleskeviciene, G., & Zikánová. (2019). Functions and translations of underspecified discourse markers in TED Talks: A parallel corpus study on five languages. Journal of Pragmatics, 142, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crible, L., & Degand, L. (2019). Domains and functions: A two-dimensional account of discourse markers. Discours, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crible, L., & Gabarró-López, S. (2021). Coherence relations across speech and sign language: A comparable corpus study of additive relations. Languages in Contrast, 21(1), 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crible, L., Gandolfi, G., & Pickering, M. J. (2024). Feedback quality and divided attention: Exploring commentaries on alignment in task-oriented dialogue. Language and Cognition, 16(4), 895–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crible, L., & Zufferey, S. (2015). Using a unifed taxonomy to annotate discourse markers in speech and writing. In H. Bunt (Ed.), Proceedings 11th joint ACL—ISO workshop on interoperable semantic annotation (Isa-11) (pp. 14–22). Association for Computational Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, M. J. (2008). Pragmatic markers in contrast: The case of well. Journal of Pragmatics, 40(8), 1373–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, M. J. (2022). Translating discourse markers: Implicitation and explicitation strategies. In M. J. Cuenca, & L. Degand (Eds.), Discourse markers in interaction (pp. 215–245). De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Dister, A., Francard, M., Hambye, P., & Simon, A.-C. (2009). Du corpus à la banque de données. Du son, des textes et des métadonnées. L’évolution de la banque des données textuelles orales VALIBEL (1989–2009). Cahiers de Linguistique, 33(2), 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovoljc, K. (2016, January 24–26). Annotation of multi-word discourse markers in spoken Slovene. Discourse Relational Devices Conference (LPTS 2016), Linguistic and Psycholinguistic Approaches to Text Structuring, Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Mujica, C. L. (2004). Esquema de taxonomía de marcadores por venir. Seminario de Investigación en Sintaxis: Marcadores y Conectores. Postgrados en Lingüística, Universidad de los Andes. Merida, Venezuela. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, M., & Zufferey, S. (2017). Methodological issues in the use of directional parallel corpora. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 22(2), 270–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenlon, J., & Hochgesang, J. (2022). Signed language corpora. Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarró-López, S. (2018). Discourse markers in French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) and Catalan Sign Language (LSC): Buoys, palm-up and same. Sign Language and Linguistics, 21(1), 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarró-López, S. (2019). What can discourse markers tell us about genres and vice versa? A corpus-driven study of French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB). Lidil – Revue de linguistique et de didactique des langues, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarró-López, S. (2020). Discourse markers, where are you? Investigating the relationship between their functions and their position in French Belgian Sign Language conversations. Sign Language Studies, 20(2), 231–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarró-López, S., & Heylens, A. (2025, June 27). Translating gesture: The case of palm-ups in an LSFB-to-French student and expert corpus. 11th European Society for Translation Studies Congress, Online Congress Day, Leeds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Gabarró-López, S., Meurant, L., & Hanquet, N. (2024). Crossing boundaries: Using French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) and multimodal French corpora for contrastive, translation and interpreting studies. Across Languages & Cultures, 25(2), 268–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, G., Sekine, K., Schembri, A., & Johnston, T. (2019). Comparing signers and speakers: Building a directly comparable corpus of Auslan and Australian English. Corpora, 14(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, J., Zufferey, S., Evers-Vermeul, J., & Sanders, T. (2017). Cognitive complexity and the linguistic marking of coherence relations. A parallel corpus study. Journal of Pragmatics, 121(2), 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoza, J. (2011). The discourse and politeness functions of HEY and WELL in American Sign Language. In C. B. Roy (Ed.), Discourse in signed languages (pp. 70–95). Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Institut d’Estudis Catalans. (2025). Corpus LSC. Available online: https://corpuslsc.iec.cat/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Johnston, T. (2010). From archive to corpus: Transcription and annotation in the creation of signed language corpora. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 15(1), 106–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, T. (2019). Auslan corpus annotation guidelines. Available online: https://auslan.org.au/about/annotations/ (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Johnston, T., & Schembri, A. (2007). Australian sign language (Auslan): An introduction to sign language linguistics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lepeut, A. (2022). When hands stop moving, interaction keeps going: A study of manual holds in the management of conversation in French-speaking and signing Belgium. Languages in Contrast, 22(2), 290–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepeut, A., & Gabarró-López, S. (in press). Insights into signed language interaction management through backchannels: The case of French Belgian Sign Language and Catalan Sign Language. Pragmatics.

- Lepeut, A., & Shaw, E. (2022). Time is ripe to make interactional moves: Bringing evidence from four languages across modalities. Frontiers in Communication, 7, 780124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombart, C. (forthcoming). Bilingualism, sign language and prosody: A comparative study of contrastive focus marking by bimodal bilinguals (French-LSFB) and by native speakers and signers [Ph.D. dissertation, Université de Namur & Université de Mons]. [Google Scholar]

- McEnery, T., & Wilson, A. (2001). Corpus linguistics. Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, R. M. L. (1992). Footing shifts in American Sign Language lectures [Ph.D. thesis, University of California]. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M., & Bahan, B. (2001). Discourse analysis. In C. Lucas (Ed.), The sociolinguistics of sign languages (pp. 112–144). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meurant, L. (2015). LSFB Corpus. A digital open-access corpus containing videos and annotations in French Belgian Sign Language. Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique—FNRS and University of Namur. Available online: http://www.corpus-lsfb.be (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Meurant, L., Bernagou, E., Sánchez, S., De Clerck, C., Raes, G., Fonzé, S., Notarrigo, I., Gabarró-López, S., Paligot, A., & Sinte, A. (2015). Lex-LSFB. Base de données lexicales de la langue des signes de Belgique francophone (LSFB) issue du Corpus LSFB. LSFB-Lab, University of Namur. [Google Scholar]

- Meurant, L., Lepeut, A., Tavier, A., Vandenitte, S., Lombart, C., Gabarró-López, S., & Sinte, A. (forthcoming). The multimodal FRAPé Corpus: Towards building a comparable LSFB and Belgian French corpus. LSFB-Lab, University of Namur. [Google Scholar]

- Nzoimbengene, P. (2016). Les ‘discourse markers’ en lingála. Étude sémantique et pragmatique sur base d’un corpus de lingála de kinshasa oral [Ph.D. thesis, Université catholique de Louvain]. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, Y. (2006). Marcadores manuales en el discurso narrativo en la lengua de señas venezolana. Letras, 72, 157–208. [Google Scholar]

- Portolés Lázaro, J. (2007). Marcadores del discurso. Ariel Practicum. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, C. B. (1989). Features of discourse in an American Sign Language lecture. In C. Lucas (Ed.), The sociolinguistics of the deaf community (pp. 231–251). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schembri, A., & Cormier, K. (2022). Signed language corpora: Future directions. In J. Fenlon, & J. Hochgesang (Eds.), Signed language corpora (pp. 196–220). Gallaudet University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sloetjes, H., & Wittenburg, P. (2008). Annotation by category—ELAN and ISO DCR. In N. Calzolari, K. Choukri, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, J. Odijk, S. Piperidis, & D. Tapias (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th international conference on language resources and evaluation (LREC’08) (pp. 816–820). European Language Resources Association (ELRA). [Google Scholar]

- Stokoe, W. C. (2005). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American deaf. Studies in Linguistics. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education: Occasional Papers 8, 10(1), 3–37, (Original work published 1960). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villameriel, S. (2008). Marcadores del discurso en la lengua de signos española y en el español oral: Un estudio comparativo. In A. Moreno Sandoval (Ed.), El valor de la diversidad (meta)lingüística. Actas del VIII congreso de lingüística general. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Villameriel, S. (2010). EN-CAMBIO y ES-DECIR: Origen de los marcadores discursivos de la lengua de signos en el español oral. In Actas del IX congreso de lingüística general (Valladolid, 21–23 de junio de 2010). Available online: https://cnlse.es/antiguos/EN%20CAMBIO%2C%20ES%20DECIR%20-%20Sa%C3%BAl%20Villameriel.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Zufferey, S. (2016). Discourse connectives across languages: Factors influencing their explicit or implicit translation. Languages in Contrast, 16(2), 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, S., & Cartoni, B. (2012). English and French causal connectives in contrast. Languages in Contrast, 12(2), 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | DMs or Discourse Relations | Language Direction | Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crible et al. (2019) | All DMs with a focus on ‘and’, ‘but’, and ‘so’ | Unidirectional from English to Czech, French, Hungarian, and Lithuanian | TED Talks (Cettolo et al., 2012) |

| Cuenca (2008) | ‘Well’ | Unidirectional from English to Catalan and Spanish | The film Four Weddings and a Funeral and its dubbed versions |

| Cuenca (2022) | Connective DMs | Unidirectional from Catalan to English | Papers from the Catalan Historical Review and their translations |

| Dupont and Zufferey (2017) | Concessive relations | Bidirectional between English and French | The News Corpus (Dupont & Zufferey, 2017), Europarl Direct (Cartoni et al., 2013), and TED Talks (Cettolo et al., 2012) |

| Hoek et al. (2017) | ‘Because’, ‘so’, ‘also’, ‘in addition’, ‘although’, ‘but’, ‘if’, and ‘unless’ | Unidirectional from English to Dutch, German, French, and Spanish | Europarl Direct (Cartoni et al., 2013) |

| Zufferey (2016) | Dans la mesure où (‘insofar as’), en effet (‘indeed’), and or (‘now’, ‘but’) | Unidirectional from French to English, German, and Spanish | Europarl Direct (Cartoni et al., 2013) |

| Zufferey and Cartoni (2012) | Causal relations | Bidirectional between English and French | Europarl Direct (Cartoni et al., 2013) |

| Task | Topic of the Dialogue | Genre | Duration | Signer’s Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Childhood memories | Narrative—explicative | 4′53″ | S055 |

| S056 | ||||

| 4 | Deaf or hearing: advantages and disadvantages | Argumentative—explicative | 3′14″ | S040 |

| S041 | ||||

| 15 | Your hobby, job, passion: equipment, actions, movements, rules, etc. | Descriptive—explicative | 10′45″ | S005 |

| S048 |

| Type of DM | Absolute Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Manual + nonmanual | 210 | 83.7 |

| Nonmanual | 22 | 8.7 |

| Manual | 19 | 7.6 |

| Total | 251 | 100 |

| Domains | Absolute Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sequential | 93 | 37.0 |

| Ideational | 88 | 35.1 |

| Rhetorical | 39 | 15.5 |

| Interpersonal | 31 | 12.4 |

| Total | 251 | 100 |

| Functions | Absolute Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | 35 | 13.9 |

| Monitoring | 34 | 13.5 |

| Concession | 24 | 9.5 |

| Agreeing | 23 | 9.1 |

| Condition | 22 | 8.8 |

| Specification | 20 | 8.0 |

| Topic | 19 | 7.6 |

| Cause | 18 | 7.2 |

| Alternative | 16 | 6.4 |

| Temporal | 15 | 6.0 |

| Consequence | 10 | 4.0 |

| Hedging | 10 | 4.0 |

| Contrast | 3 | 1.2 |

| Disagreement | 1 | 0.4 |

| Quoting | 1 | 0.4 |

| Total | 251 | 100 |

| Translation of DMs in LSFB | Absolute Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Not translated by another DM in French | 178 | 71.0 |

| Translated by a DM in French | 73 | 29.0 |

| Total | 251 | 100 |

| Domains | Absolute Frequency of Omission/Substitution | % Regarding the Total | % Within the Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential | 73 | 41.0 | 78.4 |

| Ideational | 55 | 30.9 | 62.5 |

| Rhetorical | 32 | 18.0 | 82.0 |

| Interpersonal | 18 | 10.1 | 58.0 |

| Total | 178 | 100 | ---- |

| Functions | Absolute Frequency of Omission/Substitution | % Regarding the Total | % Within the Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring | 31 | 17.4 | 91.2 |

| Addition | 26 | 14.6 | 74.3 |

| Concession | 18 | 10.1 | 75.0 |

| Agreeing | 10 | 5.6 | 43.5 |

| Condition | 14 | 7.9 | 63.4 |

| Topic | 14 | 7.9 | 73.7 |

| Specification | 13 | 7.3 | 65.0 |

| Cause | 13 | 7.3 | 72.2 |

| Alternative | 12 | 6.7 | 75.0 |

| Hedging | 9 | 5.0 | 90.0 |

| Consequence | 8 | 4.5 | 80.0 |

| Temporal | 7 | 3.9 | 46.7 |

| Contrast | 1 | 0.6 | 33.3 |

| Disagreement | 1 | 0.6 | 100.0 |

| Quoting | 1 | 0.6 | 100.0 |

| Total | 178 | 100 | ---- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gabarró-López, S. Discourse Markers in French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) Dialogues and Their Translation into French: A Corpus-Based Study. Languages 2025, 10, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090243

Gabarró-López S. Discourse Markers in French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) Dialogues and Their Translation into French: A Corpus-Based Study. Languages. 2025; 10(9):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090243

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabarró-López, Sílvia. 2025. "Discourse Markers in French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) Dialogues and Their Translation into French: A Corpus-Based Study" Languages 10, no. 9: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090243

APA StyleGabarró-López, S. (2025). Discourse Markers in French Belgian Sign Language (LSFB) Dialogues and Their Translation into French: A Corpus-Based Study. Languages, 10(9), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090243