L1 Attrition vis-à-vis L2 Acquisition: Lexicon, Syntax–Pragmatics Interface, and Prosody in L1-English L2-Italian Late Bilinguals

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Emergence of Attrition in Late Bilingualism

1.2. Investigating L1 Attrition Alongside L2 Acquisition Across Multiple Domains

1.2.1. The Lexicon

1.2.2. The Syntax–Pragmatics Interface

1.2.3. Prosody

| (1) | a. | Alex never received a letter. |

| b. | The candidates were notified by letter, but Alex never received a letter. |

1.3. Comparing Long-Term Residents to Classroom-Based Learners

1.4. Examining Attrition in L1-English

1.5. The Current Study

1.5.1. Research Questions

- Is evidence of L1 (i.e., English) attrition found in different groups of late L2 (i.e., Italian) speakers (i.e., long-term residents in Italy vs. university students in the UK)? If so, does attrition affect the two groups to the same extent?

- Does L1 attrition affect separate language domains (i.e., the lexicon, syntax–pragmatics interface, and prosody) within the same individuals? If so, does attrition affect these domains to different degrees1?

1.5.2. Predictions and Hypotheses

- Prediction 1: Assuming Schmid and Köpke’s (2017a, 2017b) contested claim that “every bilingual is an attriter” (as discussed in Section 1.1), we expect evidence of L1-English attrition for both groups, albeit to different degrees.

- -

- Hypotheses: Following Schmid and Köpke’s (2017a, 2017b) continuum-based model of attrition, we hypothesise that long-term residents in Italy may show more extensive L1 attrition than university students learning Italian in the UK. This prediction is based on differences in the quantity and quality of the input the two groups receive, as well as likely differences in dominance and proficiency (see participant characteristics in Section 2.1), which may favour attrition in the immersed context over the instructed context, as discussed in Section 1.3. Specifically, long-term residents in Italy may show not only slower processing but also lower accuracy and greater divergence in preferences from L1 functional monolinguals3 (i.e., controls) than university students in the UK in L1 comprehension/production. Attrition effects may, in turn, be more limited for university students in the UK—e.g., showing only slower processing, but not necessarily lower accuracy or highly divergent preferences from L1 controls in comprehension and production tasks. However, the overall degree of L1-English attrition found may be lower than that reported in previous research on L2-English speakers due to the prestige and lingua franca status of English nowadays. This potentially allows residents in Italy to access (and thus maintain) their L1 more easily, as well as making it less stimulating for university students in the UK to practice and better their L2, when compared to bilinguals of other L1s (e.g., L1-Italian, Spanish, French, etc.) in anglophone countries or university students learning L2-English in their respective L1 countries.

- Prediction 2: We expect that some4 domains will be more susceptible to L1 attrition than others, with attrition anticipated to be more prominent in the lexicon compared to the syntax–pragmatics interface or prosody. However, differences are also expected within these domains, depending on the group of speakers.

- -

- Hypotheses: First, given that lexical access has consistently been shown to be one of the most vulnerable domains in L1 attrition (see Section 1.2.1), lexical attrition may be present in both bilingual groups; however, given that L2 immersion contexts have been found to increase L1 inhibition (Linck et al., 2009) as well as differences in input, lexical attrition may be more pronounced among long-term residents in Italy. Second, based on the predictions of Sorace and Filiaci’s (2006) IH, attrition at the syntax–pragmatics interface (i.e., in anaphora resolution) is generally expected. However, based on Hulk and Müller’s (Hulk & Müller, 2000; Müller & Hulk, 2001) assumptions of the directionality of CLI, attrition from Italian to English is not predicted, since English permits only overt pronouns, whereas Italian allows both overt and null forms conditioned by discourse (see Section 1.2.2). Thus, while attrition due to CLI is not predicted, attrition driven by processing demands may still remain possible, especially in the case of long-term residents due to the likely increase in L1 inhibition and differences in input as a result of L2 immersion. Third, given that residents in an L2-speaking country are exposed daily to L1-like prosody in a range of communicative settings, the quality and quantity of L2 input may gradually influence their L1 prosodic patterns. On the other hand, classroom-based students in their L1-speaking country typically receive more limited and formal input, and prosody is rarely a focus of explicit instruction, making prosodic attrition less likely in this group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- University students in their final year of Italian studies at different UK universities, born in the UK, and who grew up with English as their only L1—currently living in the UK (n = 27).

- Long-term residents in Italy, born in the UK, and who grew up with English as their only L1—currently living in Italy after having emigrated there (and started learning Italian) at sixteen years of age or older (n = 27).

- L1-English controls, born and living in the UK and fluent in no other language aside from English—with knowledge of an L2 at school level permitted, as long as it was not deemed fluent (n = 31).

- L1-Italian controls, born and living in Italy and fluent in no other language aside from Italian—with knowledge of an L2 at school level permitted, as long as it was not deemed fluent (n = 27).

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Lexicon: Translation-Recognition Task

- Lexical neighbour (LN) distractors, where the second word presented (the L1 word; e.g., “amber”) is similar to the first word (the L2 word; e.g., albero/”tree”) in form.

- Translation neighbour (TN) distractors, where the second word presented (e.g., “spree”) is similar in form to the correct L1 translation (e.g., “tree” for albero).

- Semantic (S) distractors, where the second word presented (e.g., “leaves”) is similar in meaning to the correct L1 translation (e.g., “tree” for albero).

2.2.2. Syntax–Pragmatics Interface: Self-Paced Reading Task

- Twelve items with (overt) pronoun ambiguity, possibly resolved either towards the NP1 or towards the NP2 (i.e., “ambiguous NP1/2”).

- Twelve items with unambiguous (overt) pronoun resolution, half with forced NP1 resolutions (i.e., “unambiguous NP1”) and half with forced NP2 resolutions (i.e., “unambiguous NP2”).

- Forty-eight (English)/sixty (Italian) filler items6.

- Examples of ambiguous NP1/2 stimuli for anaphora resolution:

| (2) | a. | La nipote | saluta | la nonna | sull’autobus. | Lei | è | davvero ansiosa. |

| b. | The granddaughter | greets | the grandmother | on the bus. | She | is | really anxious. |

- Examples of unambiguous NP1 stimuli for anaphora resolution:

| (3) | a. | La nipote | saluta | il nonno | sull’autobus. | Lei | è | davvero ansiosa. |

| b. | The granddaughter | greets | the grandfather | on the bus. | She | is | really anxious. |

2.2.3. Prosody: Picture-Naming Task

- Contrastive/contrastive (CC), where both the adjective and the noun describing the second image (i.e., the target NP) were absent from the description of the preceding image; e.g., a blue dragon preceded by a red pumpkin (32 items in total).

- Contrastive/given (CG), where the first content word of the description of the second image contrasted with the first content word of the preceding NP, but the second content word was the same; to give an English example, a red tiger preceded by a blue tiger (16 items in total).

- Given/contrastive (GC), where the second content word of the target NP contrasted with the second content word of the preceding NP, but the first content word was the same; to give an English example, a yellow flower preceded by a yellow pumpkin (16 items in total).

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Design Measures and Predicted Outcomes

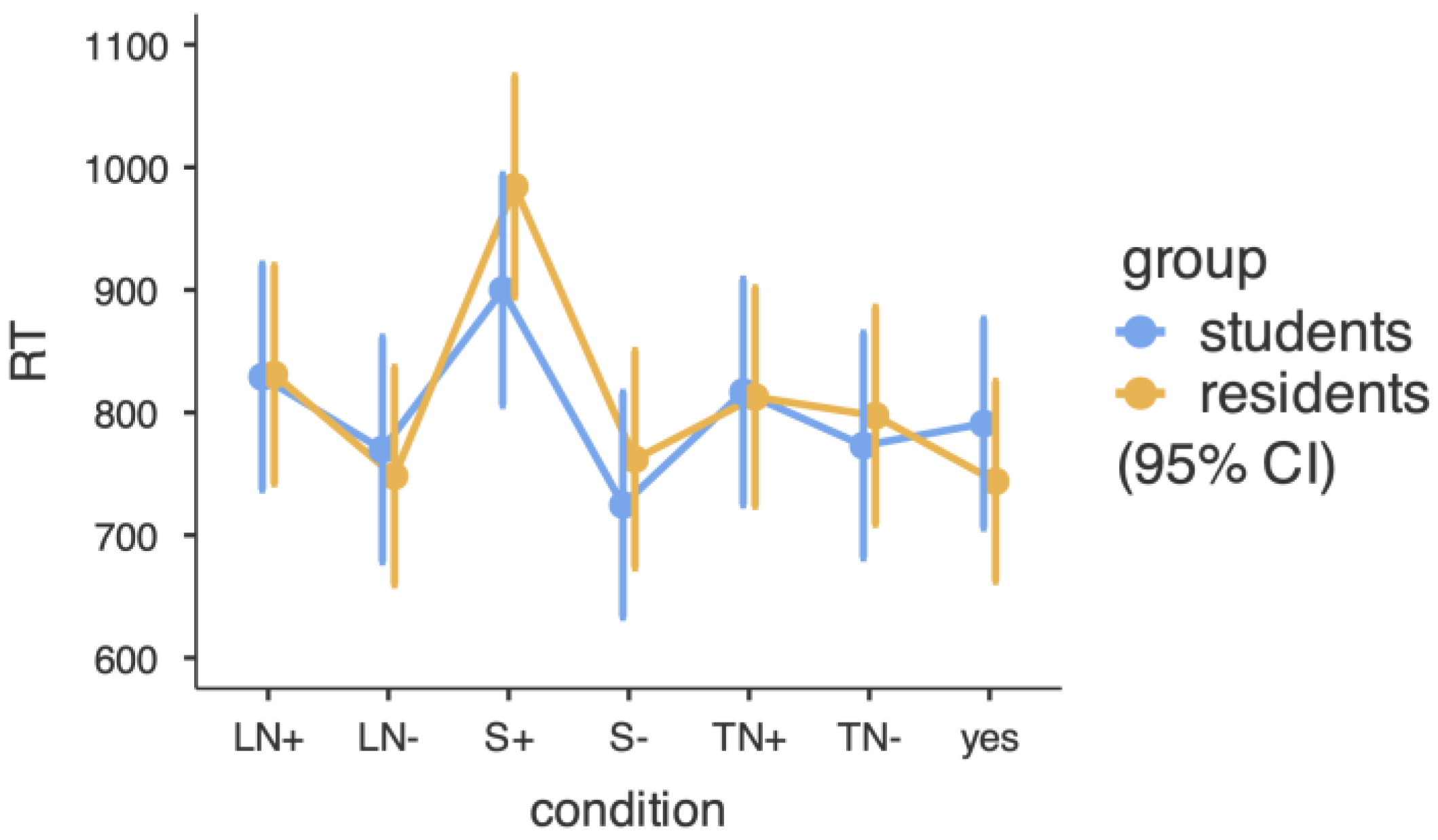

- TRT: For accuracy (1 = accurate, 0 = inaccurate), it was expected that long-term residents in Italy (henceforth “residents”) would be less likely to respond accurately in S+ trials compared to S- trials, as a result of the increased semantic interference reported in speakers with higher L2 proficiency. Conversely, university students in the UK (henceforth “students”) were anticipated to show lower accuracy in TN+ trials compared to TN- trials, as a result of the heightened lexical interference reported in speakers with lower L2 proficiency. As for RTs, S+ trials were expected to result in longer RTs for residents, whereas students were predicted to have longer RTs for TN+ trials.

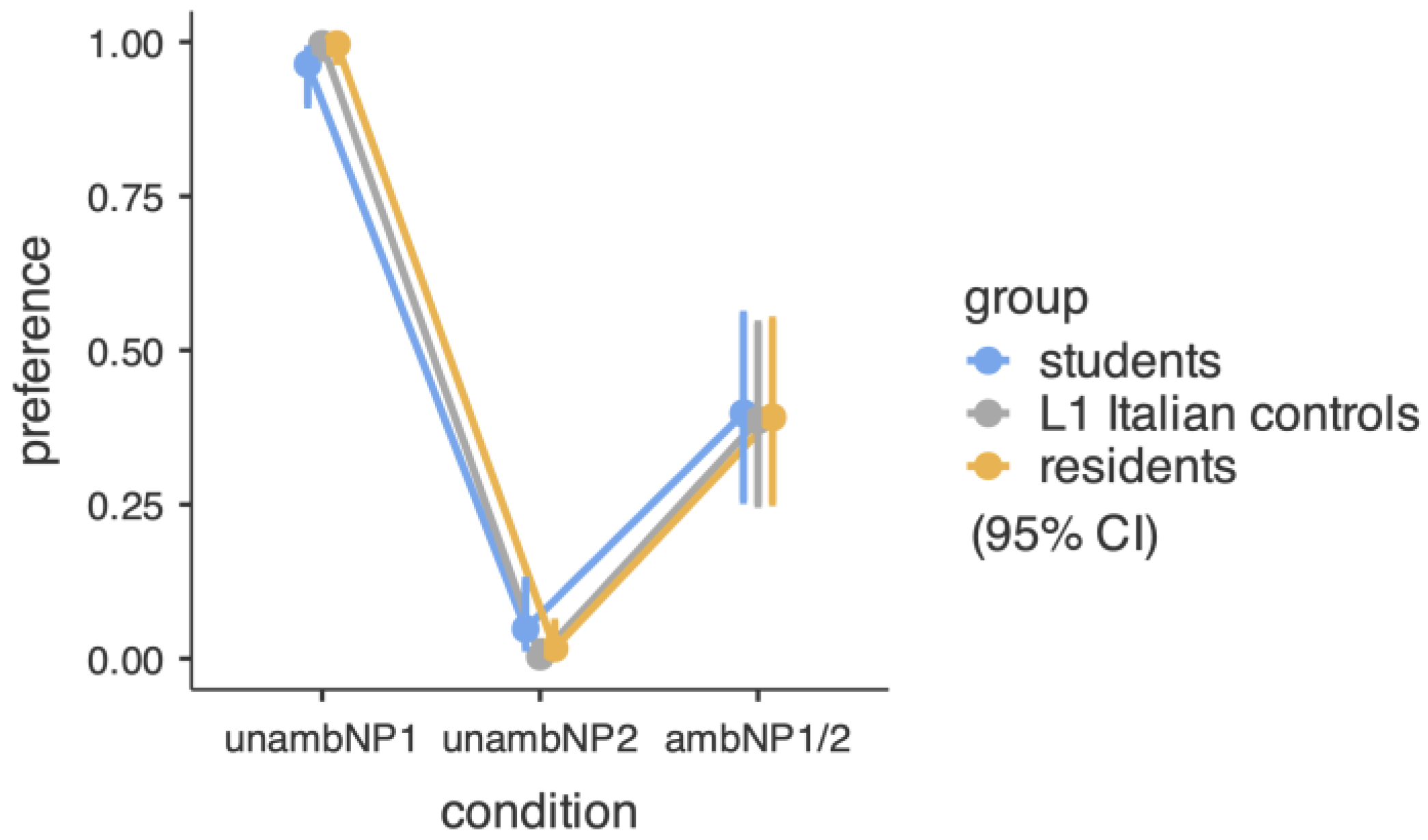

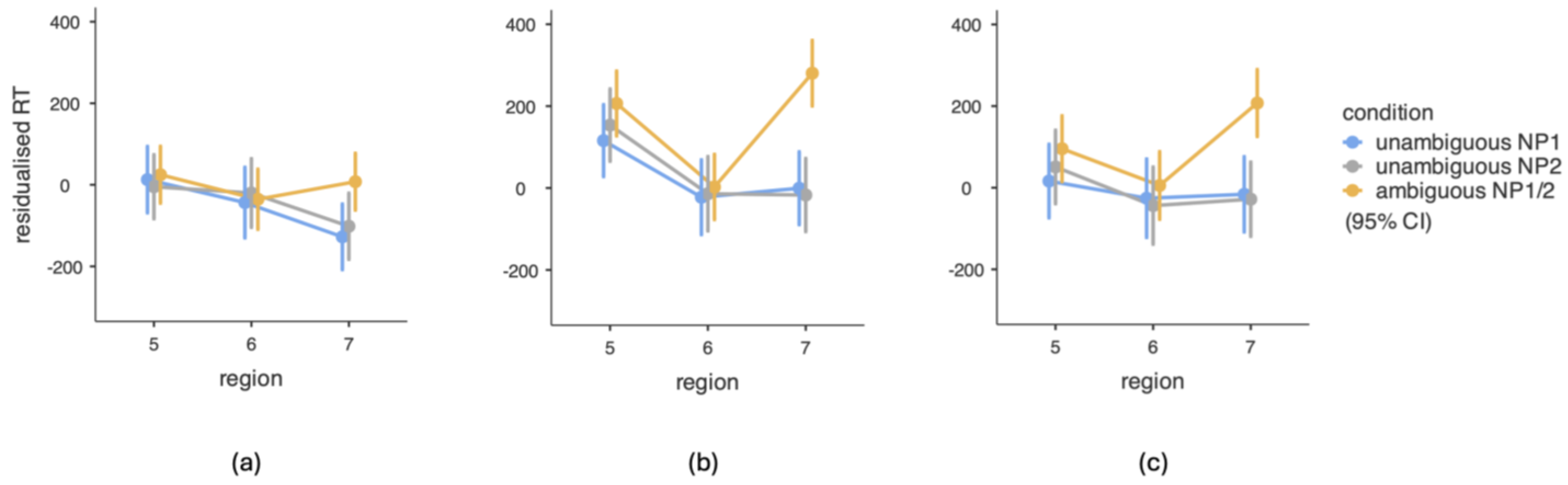

- SPRT: For preference (1 = NP1, 0 = NP2), no significant differences were anticipated between the groups in L1-English (i.e., no L1 attrition predicted), due to the assumed directionality of CLI: from English (the language with one option) to Italian (the one with two options), but not vice versa. On the other hand, in L2-Italian, it was expected that ambiguous NP1/2 (target) trials would be more likely to be resolved as NP1 for both bilingual groups—especially students—when compared to L1-Italian controls, due to the influence of L1-English. As for RTs, no CLI-induced group differences in RTs were anticipated in L1-English; however, some general slowdown in English may still be possible, particularly among residents due to the likely increase in L1 inhibition and differences in input as a result of L2 immersion. In L2-Italian, both bilingual groups—especially students—were expected to take longer on ambiguous NP1/2 trials compared to L1-Italian controls.

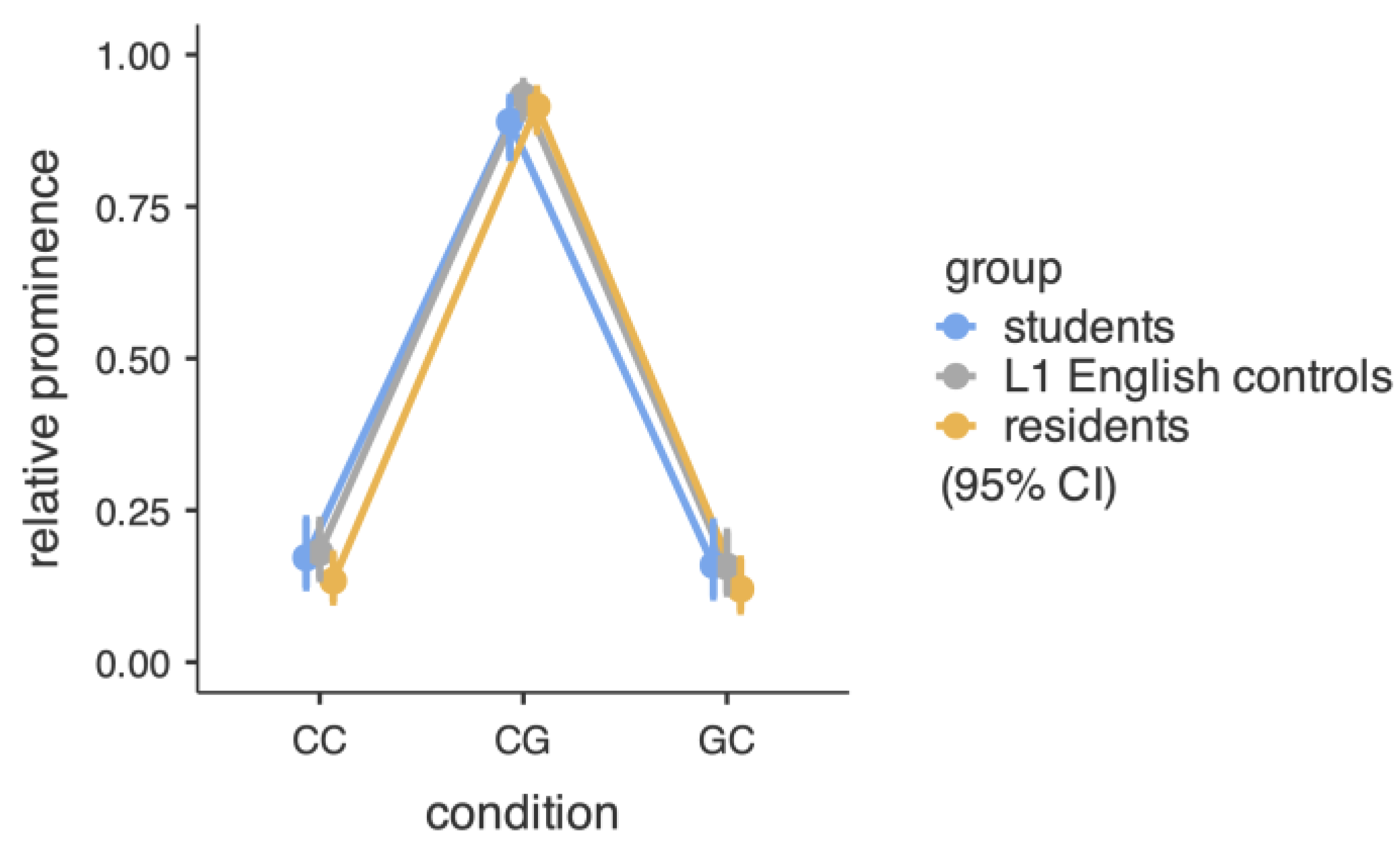

- PNT: For relative prominence (1 = adjusted for repetition, 0 = not adjusted), residents were expected to be less likely to adjust prominence in L1-English compared to L1-English controls and students in CG trials, due to potential L2-to-L1 intonational transfer. In L2-Italian, it was expected that students would be more likely than both residents and L1-Italian controls to adjust prominence in CG trials, due to possible L1-to-L2 transfer.

2.5. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

3.1. TRT Results

3.2. SPRT Results

3.3. PNT Results

3.3.1. Confirmatory Analyses for Prominence Adjustment

3.3.2. Exploratory Analyses for Cross-Item Prominence Adjustment

4. Discussion

4.1. L1 Attrition in Different Bilingual Speakers and Language Domains

4.2. The Relationship Between L1 Attrition and L2 Acquisition

4.3. L1 Attrition: CLI and/or Processing Demands?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the original PhD work that this article is based on, RQ2 also examined whether the resolution of different structures within the same domain (i.e., pronouns and relative clauses) is affected to the same extent. However, to keep the discussion focused and manageable in scope, this article focuses on pronoun resolution only. Full coverage of relative clause resolution is available in Zingaretti (2022) and forthcoming work. |

| 2 | Individual predictions were also formulated and preregistered on the AsPredicted platform for each section of this study. For lexical access: https://aspredicted.org/g2cp-db3b.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025); for syntactic interfaces: https://aspredicted.org/vs69-2pfh.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025); for prosody: https://aspredicted.org/wkxw-kbsc.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025). |

| 3 | As explained in Section 2, the participants chosen as English and Italian controls are “monolingual” in the sense that they are not fluent in any language other than their L1. However, they may have studied other languages in school, highlighting an increasing difficulty in finding fully monolingual speakers nowadays—thus supporting recent proposals to replace monolingual controls in second language research (see Rothman et al., 2023). |

| 4 | In the original prediction 2 (see note 1 above), all domains were expected to be affected for long-term residents in Italy, given the inclusion of relative clauses, which were expected to undergo attrition (cf. Zingaretti, 2022). |

| 5 | We also aimed to investigate accuracy and speed in L1/L2 word production through the use of two verbal fluency tasks (with semantic and phonemic categories, respectively). However, due to technical issues, participants’ verbal fluency recordings did not save properly (i.e., recordings either did not save at all, or the initial parts were missing from the saved files) and could thus not be analysed. |

| 6 | The higher number of fillers in Italian was to account for twelve additional items with ambiguous null pronouns initially included in the language. However, due to the potential resolution bias introduced by the lack of unambiguous null pronoun items, ambiguous null pronoun items were later excluded from the final analysis. |

| 7 | Only a subset (n = 92) of the participants completed the PNT. |

| 8 | Contrary to the preregistration, separate models were fitted for English and Italian in both the SPRT and PNT, as different participant groups completed each language version (e.g., L1-Italian controls completed the tasks in Italian, while L1-English controls completed them in English). |

| 9 | While not part of the preregistered analysis, it was necessary to add the variable region in the analyses in order to detect at what point, critically or post-critically, processing costs would show if they occurred. |

| 10 | Contrary to the preregistered analyses, yes trials were added to the regression model by removing the independent variable relatedness and including all conditions in one model. |

References

- Amenta, S., Badan, L., & Brysbaert, M. (2021). LexITA: A quick and reliable assessment tool for Italian L2 receptive vocabulary size. Applied Linguistics, 42(2), 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R. W. (1982). Determining the linguistic attributes of language attrition. In R. D. Lambert, & B. F. Freed (Eds.), The loss of language skills (pp. 83–118). Newbury House. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, L. (2024). The role of linguistic input in adult grammars: Modelling L1 morphosyntactic attrition [Ph.D. thesis, University of Southampton]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, M., Bernardini, S., Ferraresi, A., & Zanchetta, E. (2009). The WaCky wide web: A collection of very large linguistically processed web-crawled corpora. Language Resources and Evaluation, 43(3), 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, D. J., Levy, R., Scheepers, C., & Tily, H. J. (2013). Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of Memory and Language, 68(3), 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baus, C., Costa, A., & Carreiras, M. (2013). On the effects of second language immersion on first language production. Acta Psychologica, 142(3), 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, M. (1993). La adquisición del italiano: Más allá de las propiedades sintácticas del parámetro pro-drop. In J. Liceras (Ed.), La lingüística y el análisis de los sistemas no nativos (pp. 129–139). Dovehouse. [Google Scholar]

- Bolinger, D. (1972). Degree words (Vol. 53). Janua Linguarum. Series Maior. De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfieni, M. (2018). Bilingual continuum: Mutual effects of language and cognition [Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh]. Available online: https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/31365 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Bonfieni, M., Branigan, H. P., Pickering, M. J., & Sorace, A. (2019). Language experience modulates bilingual language control: The effect of proficiency, age of acquisition, and exposure on language switching. Acta Psychologica, 193, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J. (2003). The intercultural style hypothesis: L1 and L2 interaction in requesting behaviour. In V. Cook (Ed.), Effects of the second language on the first (pp. 62–80). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro, G., & Sorace, A. (2019). The interface hypothesis as a framework for studying L1 attrition. In M. S. Schmid, & B. Köpke (Eds.), The oxford handbook of language attrition (pp. 24–35). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, G., Sorace, A., & Sturt, P. (2016a). What is the source of L1 attrition? The effect of recent L1 re-exposure on Spanish speakers under L1 attrition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(3), 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, G., Sturt, P., & Sorace, A. (2016b). Selectivity in L1 attrition: Differential object marking in Spanish near-native speakers of English. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 45(3), 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherciov, M. (2011). Between attrition and acquisition: The dynamics between two languages in adult migrants [Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto]. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. (2000). Minimalist inquiries. In R. Martin, D. Michaels, & J. Uriagereka (Eds.), Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of howard lasnik (pp. 89–155). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, V. (Ed.). (2003). Effects of the second language on the first. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruttenden, A. (1993). The de-accenting and re-accenting of repeated lexical items. In Proceedings of the ESCA workshop on prosody (pp. 16–19). Working Papers 41. Department of Linguistics and Phonetics, University of Lund. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, D. (2012). English as a global language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza, A. (2010). On the L1 attrition of the Spanish present tense. Hispania, 93(2), 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, E. (2007). Hesitation markers in English, German, and Dutch. Journal of Germanic Linguistics, 19(02), 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, E. (2017). How phonetics and phonology inform L1 attrition (narrowly defined) research. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 7(6), 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, E., Tusha, A., & Schmid, M. S. (2018). Individual phonological attrition in Albanian–English late bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 21(2), 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prada Pérez, A. (2009). Subject expression in Minorcan Spanish: Consequences of contact with Catalan [Ph.D. thesis, The Pennsylvania State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Długosz, K. (2021). L2 Effects on L1 in foreign language learners: An exploratory study on object pronouns and verb placement in WH-questions in Polish. Prace Językoznawcze, 23(4), 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, L., & Hicks, G. (2016). Synchronic change in a multidialectal community: Evidence from Spanish null and postverbal subjects. In A. Cuza, L. Czerwionka, & D. Olson (Eds.), Inquiries in Hispanic linguistics: From theory to empirical evidence (pp. 53–72). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostert, S. (2004). Sometimes I feel as if there’s a big hole in my head where English used to be!: Attrition of L1 English. International Journal of Bilingualism, 8(3), 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duñabeitia, J. A., Baciero, A., Antoniou, K., Antoniou, M., Ataman, E., Baus, C., Ben-Shachar, M., Çağlar, O. C., Chromý, J., Comesaña, M., Filip, M., Đurđević, D. F., Dowens, M. G., Hatzidaki, A., Januška, J., Jusoh, Z., Kanj, R., Kim, S. Y., Kırkıcı, B., … Pliatsikas, C. (2022). The multilingual picture database. Scientific Data, 9(1), 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallucci, M. (2019). GAMLj Suite for jamovi. Available online: https://gamlj.github.io (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Gargiulo, C. (2020). On L1 attrition and prosody in pronominal anaphora resolution [Ph.D. thesis, Lund University]. Available online: https://www.ht.lu.se/en/series/9855440/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Green, D. W. (1986). Control, activation, and resource: A framework and a model for the control of Speech in bilinguals. Brain and Language, 27(2), 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D. W. (1998). Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 1(2), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, F. (1989). Neurolinguists, beware! The bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. Brain and Language, 36(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido Mendes, C., & Iribarren, C. (2007). Fixação do parâmetro do sujeito nulo na aquisição do português europeu por hispanofalantes. In XXII Encontro nacional da associação portuguesa de linguística: Textos seleccionados (pp. 483–497). Associação Portuguesa de Linguística. [Google Scholar]

- Gussenhoven, C. (2004). The phonology of tone and intonation (1st ed). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürel, A. (2004). Selectivity in L2-induced L1 attrition: A psycholinguistic account. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 17(1), 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürel, A. (2007). (Psycho)linguistic Determinants of L1 Attrition. In B. Köpke, M. S. Schmid, M. Keijzer, & S. C. Dostert (Eds.), Language attrition: Theoretical perspectives (pp. 99–121). John Benjamins. Available online: https://benjamins.com/catalog/sibil.33.08gur (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Hicks, G., & Domínguez, L. (2020). A model for L1 grammatical attrition. Second Language Research, 36(2), 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberg, J. (1993). Pitch accent in context: Predicting intonational prominence from text. Artificial Intelligence, 63(1–2), 305–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, M. (1990). Accentual patterning in ‘new’ vs ‘given’ subjects in English (Vol. 36, pp. 81–97). Working papers. Lund University, Department of Linguistics and Phonetics. [Google Scholar]

- Hulk, A., & Müller, N. (2000). Bilingual first language acquisition at the interface between syntax and pragmatics. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 3(3), 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, M. B. (2012). Advanced language attrition of Spanish in contact with Brazilian Portuguese [Ph.D. thesis, University of Iowa]. Available online: http://rgdoi.net/10.13140/RG.2.2.27341.84962 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Jarvis, S. (2019). Lexical Attrition. In M. S. Schmid, & B. Köpke (Eds.), The oxford handbook of language attrition (pp. 240–250). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J., Baker, W., & Dewey, M. (2018). The Routledge handbook of English as a lingua franca. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, M. A., Carpenter, P. A., & Woolley, J. D. (1982). Paradigms and processes in reading comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 111(2), 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltsa, M., Tsimpli, I. M., & Rothman, J. (2015). Exploring the source of differences and similarities in L1 attrition and heritage speaker competence: Evidence from pronominal resolution. Lingua, 164(B), 266–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kecskes, I. (1998). The state of L1 knowledge in foreign language learners. WORD, 49(3), 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kecskes, I., & Papp, T. (2000). Foreign language and mother tongue. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Kecskes, I., & Papp, T. (2003). How to demonstrate the conceptual effect of the L2 on L1? Methods and techniques. In V. Cook (Ed.), The effect of the second language on the first (pp. 247–267). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. H. O., & Starks, D. (2008). The role of emotions in L1 attrition: The case of Korean-English late bilinguals in New Zealand. International Journal of Bilingualism, 12(4), 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpke, B. (2002). Activation thresholds and non-pathological first language attrition. In F. Fabbro (Ed.), Advances in the neurolinguistics of bilingualism (pp. 119–142). Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, J. F., & Ma, F. (2018). The bilingual lexicon. In E. M. Fernández, & H. S. Cairns (Eds.), The handbook of psycholinguistics (pp. 294–319). Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, J. F., & Stewart, E. (1994). Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Language, 33(2), 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J. F., & Tokowicz, N. (2005). Models of bilingual representation and processing: Looking back and to the future. In J. F. Kroll, & A. M. de Groot (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches (pp. 531–553). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, T., Bayram, F., & Rothman, J. (2017). Terminology matters II: Early bilinguals show cross-linguistic influence but are not attriters. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 7(6), 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D. R. (1980). The structure of intonational meaning: Evidence from English. Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, D. R. (2008). Intonational phonology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenshtein, V. I. (1966). Binary codes capable of correcting deletions, insertions, and reversals. Soviet Physics Doklady, 10(8), 707–710. [Google Scholar]

- Linck, J. A., Kroll, J. F., & Sunderman, G. (2009). Losing access to the native language while immersed in a second language: Evidence for the role of inhibition in second-language learning. Psychological Science, 20(12), 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, C. (2006). Focus and split-intransitivity: The acquisition of word order alternations in non-native Spanish. Second Language Research, 22(2), 145–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, C. (2009). Selective deficits at the syntax-discourse interface: Evidence from the CEDEL2 corpus. In Y. Leung, N. Snape, & M. Sharwood-Smith (Eds.), Representational deficits in second language acquisition (pp. 127–166). John Benjamins. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/22165 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Ma, F., Chen, P., Guo, T., & Kroll, J. F. (2017). When late second language learners access the meaning of L2 words: Using ERPs to investigate the role of the L1 translation equivalent. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 41, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaza, P., & Bel, A. (2006). Null subjects at the syntax-pragmatics interface: Evidence from Spanish interlanguage of Greek speakers. In M. G. O’Brien, C. Shea, & J. Archibald (Eds.), Proceedings of the 8th generative approaches to second language acquisition conference (GASLA 2006) (pp. 88–97). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Marian, V., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). The language experience and proficiency questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50(4), 940–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinis, T. (2010). Using on-line processing methods in language acquisition research. In E. Blom, & S. Unsworth (Eds.), Experimental methods in language acquisition research (pp. 139–162). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Villena, F. (2023). L1 Morphosyntactic attrition at the early stages: Evidence from production, interpretation, and processing of subject referring expressions in L1 Spanish-L2 English instructed and immersed bilinguals [Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Granada]. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10481/81920 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Martín-Villena, F., & Lozano, C. (2020). Anaphora resolution in topic continuity: Evidence from L1 English–L2 Spanish data in the CEDEL2 corpus. In J. Ryan, & P. Crosthwaite (Eds.), Referring in a second language: Studies on reference to person in a multilingual world (pp. 119–141). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennen, I. (2004). Bi-directional interference in the intonation of Dutch speakers of Greek. Journal of Phonetics, 32(4), 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michnowicz, J. (2015). Maya-spanish contact in yucatan, mexico: Context and sociolinguistic implications. In S. Sessarego, & M. G. Rivera (Eds.), New perspectives on Hispanic contact linguistics in the Americas (pp. 21–42). Iberoamericana/Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, S., & Yoon, J. (2019). Morphology and language attrition. In Oxford research encyclopedia of linguistics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, T. H., Dilley, L. C., & McAuley, J. D. (2014). Prosodic patterning in distal speech context: Effects of list intonation and F0 downtrend on perception of proximal prosodic structure. Journal of Phonetics, 46, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N., & Hulk, A. (2001). Crosslinguistic influence in bilingual language acquisition: Italian and French as recipient languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 4(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, S. G., & Terken, J. M. B. (1982). What makes speakers omit pitch accents? An experiment. Phonetica, 39(4–5), 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, M. (1993). Linguistic, psycholinguistic, and neurolinguistic aspects of ‘interference’ in bilingual speakers: The activation threshold hypothesis. International Journal of Psycholinguistics, 9, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, M. (2004). A neurolinguistic theory of bilingualism. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, M. (2007). L1 attrition features predicted by a neurolinguistic theory of bilingualism. In B. Köpke, M. S. Schmid, M. Keijzer, & S. Dostert (Eds.), Studies in bilingualism (pp. 121–133). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, B. R., Grison, S., Gao, X., Christianson, K., Morrow, D. G., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. (2014). Aging and individual differences in binding during sentence understanding: Evidence from temporary and global syntactic attachment ambiguities. Cognition, 130, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porte, G. (1999). English as a forgotten language: The perceived effects of language attrition. ELT Journal, 53(1), 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, R. (1993). Methods for dealing with reaction time outliers. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 510–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Reichle, R. V., & Birdsong, D. (2014). Processing focus structure L1 and L2 French: L2 proficiency effects on ERPs. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 36(3), 535–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, P. E., & Berry, G. M. (2021). Cross-linguistic influence in L1 processing of morphosyntactic variation: Evidence from L2 learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 42(1), 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezlescu, C., Danaila, I., Miron, A., & Amariei, C. (2020). More time for science: Using testable to create and share behavioral experiments faster, recruit better participants, and engage students in hands-on research. Progress in Brain Research, 253, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ordóñez, I., & Sainzmaza-Lecanda, L. (2018). Bilingualism effects in Basque subject pronoun expression: Evidence from L2 basque. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 8(5), 523–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, J., Bayram, F., DeLuca, V., Di Pisa, G., Duñabeitia, J. A., Gharibi, K., Hao, J., Kolb, N., Kubota, M., Kupisch, T., & Laméris, T. (2023). Monolingual comparative normativity in bilingualism research is out of ‘control’: Arguments and alternatives. Applied Psycholinguistics, 44(3), 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103(3), 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S. (2016). First language attrition. Language Teaching, 49(2), 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S. (2019). The impact of frequency of use and length of residence on L1 attrition. In M. S. Schmid, & B. Köpke (Eds.), The oxford handbook of language attrition. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S., & Cherciov, M. (2019). Introduction to extralinguistic factors in language attrition. In M. S. Schmid, & B. Köpke (Eds.), The oxford handbook of language attrition (pp. 505–522). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S., & Jarvis, S. (2014). Lexical access and lexical diversity in first language attrition. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17(4), 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S., & Köpke, B. (2009). L1 attrition and the mental lexicon. In A. Pavlenko (Ed.), The bilingual mental lexicon (pp. 209–238). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S., & Köpke, B. (2017a). The relevance of first language attrition to theories of bilingual development. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 7(6), 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S., & Köpke, B. (2017b). When is a bilingual an attriter? Response to the commentaries. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 7(6), 721–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M. S., & Köpke, B. (Eds.). (2019). The oxford handbook of language attrition (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliger, H. W., & Vago, R. M. (Eds.). (1991). First language attrition. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A. (2005). Selective optionality in language development. In L. M. E. A. Cornips, & K. P. Corrigan (Eds.), Current issues in linguistic theory (Vol. 265, pp. 55–80). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A. (2011). Pinning down the concept of ‘interface’ in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 1(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A. (2012). Pinning down the concept of interface in bilingual development: A reply to peer commentaries. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 2(2), 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A. (2016). Referring expressions and executive functions in bilingualism. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 6(5), 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A. (2020). L1 attrition in a wider perspective. Second Language Research, 36(2), 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A., & Filiaci, F. (2006). Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research, 22(3), 339–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, A., Serratrice, L., Filiaci, F., & Baldo, M. (2009). Discourse conditions on subject pronoun realization: Testing the linguistic intuitions of older bilingual children. Lingua, 119(3), 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sučková, M. (2020). Acquisition of a foreign accent by native speakers of English living in the Czech Republic. ELOPE: English Language Overseas Perspectives and Enquiries, 17(1), 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderman, G. (2013). Translation recognition tasks. In J. Jegerski, & B. VanPatten (Eds.), Research methods in second language psycholinguistics (pp. 185–211). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderman, G., & Kroll, J. F. (2006). First language activation during second language lexical processing: An Investigation of lexical form, meaning, and grammatical class. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(3), 387–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerts, M. (2007). Contrast and accent in Dutch and Romanian. Journal of Phonetics, 35(3), 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerts, M., Krahmer, E., & Avesani, C. (2002). Prosodic marking of information status in Dutch and Italian: A comparative analysis. Journal of Phonetics, 30(4), 629–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerts, M., & Zerbian, S. (2010). Intonational differences between L1 and L2 English in South Africa. Phonetica, 67(3), 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talamas, A., Kroll, J. F., & Dufour, R. (1999). From form to meaning: Stages in the acquisition of second-language vocabulary. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 2(1), 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The jamovi project. (2022). jamovi (version 2.3). Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Torregrossa, J., Andreou, M., Bongartz, C., & Tsimpli, I. M. (2021). Bilingual acquisition of reference: The role of language experience, executive functions and cross-linguistic effects. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 24(4), 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimpli, I. M., & Sorace, A. (2006). Differentiating Interfaces: L2 performance in syntax-semantics and syntax-discourse phenomena. In D. Bamman, T. Magnitskaia, & C. Zaller (Eds.), Proceedings of Boston University Conference on Language Development 30 (pp. 653–664). Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimpli, I. M., Sorace, A., Heycock, C., & Filiaci, F. (2004). First language attrition and syntactic subjects: A study of Greek and Italian near-native speakers of English. International Journal of Bilingualism, 8(3), 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, C., Van Wonderen, E., Koutamanis, E., Jan Kootstra, G., Dijkstra, T., & Unsworth, S. (2022). Cross-linguistic influence in simultaneous and early sequential bilingual children: A meta-analysis. Journal of Child Language, 49(5), 897–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Maastricht, L., Krahmer, E., & Swerts, M. (2016). Prominence patterns in a second language: Intonational transfer from Dutch to Spanish and vice versa. Language Learning, 66(1), 124–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, G. S., & Caplan, D. (1996). The measurement of verbal working memory capacity and its relation to reading comprehension. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49(1), 51–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreich, U. (1953). Languages in contact: Findings and problems. Linguistic Circle of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Weltens, B., & Grendel, M. (1993). Attrition of vocabulary knowledge. In R. Schreuder, & B. Weltens (Eds.), The Bilingual lexicon (pp. 135–156). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, G., & Schmid, M. S. (2018). First language attrition and bilingualism. In D. Miller, F. Bayram, J. Rothman, & L. Serratrice (Eds.), Bilingual cognition and language: The state of the science across its subfields (pp. 225–250). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Zingaretti, M. (2022). First language attrition in late bilingualism: Lexical, syntactic and prosodic changes in English-Italian bilinguals [Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingaretti, M., Garraffa, M., & Sorace, A. (2024). The impact of bilingualism on hate speech perception and slur appropriation: An initial study of Italian UK residents. In S. Cruschina, & C. Gianollo (Eds.), An investigation of hate speech: Use, identification, and perception of aggressive language in Italian (pp. 193–230). Helsinki University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingaretti, M., & Spelorzi, R. (2021). Bridging the gap between native and non-native English-speaking teachers: Insights from bilingualism research. Spark: Stirling International Journal of Postgraduate Research, 7(1), 1–14. Available online: https://spark.stir.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Zingaretti-and-Spelorzi_final.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

| Characteristic | University Students | Long-Term Residents | L1-English Controls | L1-Italian Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants | 27 | 27 | 31 | 27 |

| Born in | UK | UK | UK | Italy |

| Living in | UK | Italy | UK | Italy |

| L1 | English | English | English | Italian |

| L2 | Italian | Italian | N/A | N/A |

| Gender a | ♀ = 24 | ♀ = 21 | ♀ = 17 | ♀ = 23 |

| ♂ = 3 | ♂ = 6 | ♂ = 13 | ♂ = 4 | |

| ⚲ = 0 | ⚲ = 0 | ⚲ = 1 | ⚲ = 0 | |

| Age (Years) | M = 21.9 | M = 45.4 | M = 27 | M = 28.2 |

| SD = 1 | SD = 14.4 | SD = 6.2 | SD = 7.9 | |

| Age of L2 Acquisition (Years) | M = 17.6 | M = 24 | N/A | N/A |

| SD = 1.3 | SD = 7.7 | |||

| Length of Residence in L2 Country (Years) b | M = 0.1 | M = 20.4 | N/A | N/A |

| SD = 0.3 | SD = 14.1 | |||

| L2 Proficiency Score c | M = 32.2 | M = 69.9 | N/A | N/A |

| SD = 24.1 | SD = 16.6 | |||

| Working Memory Score (Number Recalled) d | M = 46.4 | M = 49.7 | M = 45.7 | M = 47.7 |

| SD = 9.8 | SD = 8.3 | SD = 10.7 | SD = 5.5 |

| Italian | English | Related (+) | Unrelated (−) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN+ | TN+ | S+ | LN− | TN− | S− | ||

| albero | tree | amber | spree | leaves | norms | hirer | agenda |

| University Students in UK | Long-Term Residents in Italy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | Accuracy | RT | Accuracy | |

| Yes Trials | 738 | 78.2% | 775 | 94.1% |

| No Trials | ||||

| Lexical Neighbour | ||||

| Related | 788 | 96.2% | 859 | 96.6% |

| Unrelated | 733 | 98.9% | 777 | 99.3% |

| Translation Neighbour | ||||

| Related | 777 | 93.3% | 843 | 94.1% |

| Unrelated | 726 | 97.0% | 815 | 100% |

| Semantic Distractor | ||||

| Related | 847 | 79.8% | 1000 | 87.1% |

| Unrelated | 691 | 98.5% | 797 | 98.1% |

| University Students in UK | Long-Term Residents in Italy | L1 Controls | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP1 | NP2 | p | NP1 | NP2 | p | NP1 | NP2 | p | |

| English | |||||||||

| Unambiguous NP1 | 97.5% | 2.5% | *** | 99% | 1% | *** | 97% | 3% | *** |

| Unambiguous NP2 | 2.5% | 97.5% | *** | 1% | 99% | *** | 3% | 97% | *** |

| Ambiguous NP1/2 | 55.5% | 44.5% | * | 53% | 47% | 57% | 43% | ** | |

| Italian | |||||||||

| Unambiguous NP1 | 94.5% | 5.5% | *** | 99% | 1% | *** | 99% | 1% | *** |

| Unambiguous NP2 | 7% | 93% | *** | 3% | 97% | *** | 1% | 99% | *** |

| Ambiguous NP1/2 | 43% | 57% | 42% | 58% | 41% | 59% | *** | ||

| University Students in UK | Long-Term Residents in Italy | L1 Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | PNA | PA | PNA | PA | PNA | |

| English | ||||||

| CC | 19.2% | 80.8% | 15.4% | 84.6% | 19.6% | 80.4% |

| CG | 87.3% | 12.7% | 89.6% | 10.4% | 92.2% | 7.8% |

| GC | 17.9% | 80.1% | 14% | 86% | 17.3% | 82.7% |

| Italian | ||||||

| CC | 2.4% | 97.6% | 0.4% | 99.6% | 0.7% | 99.3% |

| CG | 35.4% | 64.6% | 10.1% | 89.9% | 0.5% | 99.5% |

| GC | 0.3% | 99.7% | 0.2% | 99.8% | 0% | 100% |

| University Students in UK | Long-Term Residents in Italy | L1 Controls | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | PA | PNA | N | PA | PNA | N | PA | PNA | |

| CC | 109 | 62% | 38% | 164 | 56% | 44% | 175 | 65% | 35% |

| CG | 56 | 86% | 14% | 90 | 96% | 4% | 90 | 92% | 8% |

| GC | 55 | 69% | 31% | 82 | 44% | 56% | 89 | 61% | 39% |

| Lexicon | Syntax–Pragmatics Interface | Prosody | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 Attrition | L2 Acquisition | L1 Attrition | L2 Acquisition | L1 Attrition | L2 Acquisition | |

| Students in UK | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Residents in Italy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ? | ✓ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zingaretti, M.; Chondrogianni, V.; Ladd, D.R.; Sorace, A. L1 Attrition vis-à-vis L2 Acquisition: Lexicon, Syntax–Pragmatics Interface, and Prosody in L1-English L2-Italian Late Bilinguals. Languages 2025, 10, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090224

Zingaretti M, Chondrogianni V, Ladd DR, Sorace A. L1 Attrition vis-à-vis L2 Acquisition: Lexicon, Syntax–Pragmatics Interface, and Prosody in L1-English L2-Italian Late Bilinguals. Languages. 2025; 10(9):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090224

Chicago/Turabian StyleZingaretti, Mattia, Vasiliki Chondrogianni, D. Robert Ladd, and Antonella Sorace. 2025. "L1 Attrition vis-à-vis L2 Acquisition: Lexicon, Syntax–Pragmatics Interface, and Prosody in L1-English L2-Italian Late Bilinguals" Languages 10, no. 9: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090224

APA StyleZingaretti, M., Chondrogianni, V., Ladd, D. R., & Sorace, A. (2025). L1 Attrition vis-à-vis L2 Acquisition: Lexicon, Syntax–Pragmatics Interface, and Prosody in L1-English L2-Italian Late Bilinguals. Languages, 10(9), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090224