Abstract

This paper revisits the cross-reference marking system of Mbyá Guaraní, focusing on two phenomena: object agreement using the prefix i- and its allomorphs, and absolutive cross-reference marking in converbs. The analysis demonstrates that cross-reference marking in Mbyá is sensitive to abstract Case. Building on a view of agreement as an obligatory operation whose failure does not result in ungrammaticality, this paper argues that the segment i- is an object agreement prefix, rather than part of an allomorph of an active subject agreement prefix. This marker is underspecified for person, allowing it to cross-reference 1st, 2nd or 3rd objects. The paper further argues that converbs in Mbyá Guaraní follow an absolutive cross-reference marking pattern, where only intransitive subjects or objects are cross-referenced. This pattern is shown to be consistent with cross-linguistic and historical data from the Tupí–Guaraní family. This paper’s contributions include a proposal for case-sensitive agreement in Mbyá, with active agreement prefixes realizing agreement with nominative DPs only. The analysis also emphasizes the different roles of Infl and little v as probes for person features, with little v being underspecified and not triggering cyclic expansion. The proposed framework accounts for both hierarchical cross-reference marking in independent clauses and absolutive marking in converbs, unifying these two patterns under the assumption of Case dependence of agreement.

1. Introduction

Guaraní languages exhibit a well-known combination of active–inactive and hierarchical patterns of cross-reference marking, illustrated in (1) with Paraguayan Guaraní examples. Intransitive verbs are split into active and inactive classes, glossed A and B in examples (1a) and (1b), respectively, which cross-reference their subject with different series of markers. Because 1st and 2nd person inactive markers are phonologically similar to free pronouns, they have been analyzed as clitic doubling (e.g., che=), in contradistinction to active agreement prefixes (e.g., a-). Cross-reference marking on transitive verbs follows a hierarchical pattern illustrated in (1c) and (1d). Verbs cross-reference their subject, unless the object is higher than the subject on the person hierarchy in (2), in which case the object is cross-referenced. Subjects are cross-referenced by active markers, cf. (1c), while objects are cross-referenced by inactive markers, cf. (1d). Combinations of a first person subject and a second person object are cross-referenced by a portmanteau prefix ro-1 as illustrated in (1e).

| 1. | Paraguayan Guaraní (Zubizarreta & Pancheva, 2017, our glosses) | |||

| a. | (Che) | a-jahu | ||

| (I) | A1SG-bathe | |||

| ‘I bathe.’ | ||||

| b. | (Che) | che=r-asẽ | ||

| (I) | B1SG-LK-cry | |||

| ‘I cry.’ | ||||

| c. | (Che) | a-mbo-jahu | Juan-pe | |

| (I) | A1SG-CAUS-bathe | Juan-PE | ||

| ‘I bathe Juan.’ | ||||

| d. | (Nde) | che=mbo-jahu | ||

| (you) | B1SG=CAUS-bathe | |||

| ‘You bathe me.’ | ||||

| e. | (Che) | ro-mbo-jahu | ||

| (I) | PORT-CAUS-bathe | |||

| ‘I bathe you.’ | ||||

| 2. | Person hierarchy governing cross-reference marking: |

| 1 > 2 > 3 |

There has been significant research within the functional–typological tradition both on the Guarani active–stative system and on person-based alternations with transitive verbs. Much research on the active–stative system focuses on factors that govern cross-referencing on intransitive verbs. Comrie (1976) and Mithun (1991) argue that the choice of active or inactive cross-referencing is due to lexical aspect (Aktionsart). Velázquez-Castillo (1991) argues that both lexical aspect and participant involvement influence active–stative cross-referencing. Velázquez-Castillo (2002) further argues that the active–stative distinction is based on a spacial construction of events, which subsumes lexical aspect and participant involvement. With transitive verbs, Payne (1994) analyzes person-based alternations between active and stative marking as a direct–inverse system. Velázquez-Castillo (2007) challenges this view and argues that the spatial construction of events also governs person-based alternations with bivalent predicates.

The present paper is situated within the generative tradition and focuses on person-based alternations in transitive verbs, rather than on the active–stative distinction in intransitive predicates. The most detailed generative account of Guaraní cross-reference marking is due to Zubizarreta and Pancheva (2017), whose analysis focuses on Paraguayan Guaraní. In their analysis, cross-reference marking results from a formal agreement relation between functional heads and referential expressions, which is driven by functional head probing for phi-features (person, gender and number) in their c-command domain. Two functional heads are involved in this process: Infl and little v. Zubizarreta & Pancheva’s analysis stands in contrast to cyclic expansion accounts of hierarchical cross-reference marking (Béjar & Rezac, 2009), which have been also applied to Tupí–Guaraní languages (see notably (Deal, 2021) on Tupinambá). In a cyclic expansion analysis of the Guaraní paradigm, a single functional head probes for phi-features in its c-command domain, which is expanded when no appropriate goal is found during the first probing cycle. Both Zubizarreta and Pancheva’s (2017) analysis and cyclic agree analyses of Guaraní person indexing aim to account for the paradigm in (1a–e). However, this paradigm is incomplete, since it fails to include two relevant phenomena attested in some Guaraní languages and more generally across the Tupí–Guaraní family: object agreement using the prefix i- and absolutive agreement in converbs.

The first phenomenon of interest concerns a subset of transitive verbs where subject and object agreement co-occur, object agreement being marked by the segment i- (or its allomorphs) following subject agreement:

| 3. | Mbyá Guaraní (constructed): | |

| Xee a-i-nupã | ||

| I | A1SG-AGR-beat | |

| ‘I beat it/him/her/them.’ | ||

In the literature on Paraguayan Guaraní, such occurrences of the segment i- are analyzed as part of an allomorph of the subject agreement prefix. By contrast, this segment has been analyzed as an object agreement prefix in the literature on Mbyá Guaraní and other Tupí–Guaraní languages.2

The second phenomenon concerns a class of converbs that follow an absolutive cross-reference marking pattern: only objects and intransitive subjects are cross-referenced, as illustrated in (4). Example (4c) in particular shows that transitive converbs cross-reference their object rather than their subject even when the latter outranks the object on the person hierarchy, as we will discuss in more detail in Section 3:

| 4. | Mbyá Guaraní (Dooley, 2015) | ||||||

| a. | A-pu’ã | a-’ã-my | |||||

| A1SG-stand.up | A1SG-stand-CONV | ||||||

| ‘I stood up and remained on my feet.’ | |||||||

| b. | Xe=r-u | xe=jopy | xe=r-er-a-vy | ||||

| B1SG=LK-father | B1SG-get | B1SG=COM-go-CONV | |||||

| ‘My father got me and took me with him.’ | |||||||

| c. | Xe=r-o | py=gua | kuery | a-r-u | h-ero-kua-py | ||

| B1SG=LK-house | LOC-NMLZ | COL | A1SG-COM-come | B3-COM-be.PL-CONV | |||

| ‘I brought all of the inhabitants of my house as a group.’ | |||||||

The present paper revisits the cross-reference marking system of Guaraní, more specifically Mbyá Guaraní, in light of these two phenomena. We argue that agreement is sensitive to abstract Case in Mbyá, active markers being the morphological realization of agreement of Infl heads with nominative DPs. We argue that both Infl and little v probe for person features, but little v is underspecified and therefore never triggers cyclic expansion. In this model, active agreement prefixes and inactive clitic doubling compete for the morphological realization of phi-features on Infl, which probes for phi-features on both external and internal arguments. By contrast, object agreement markers that co-occur with subject agreement prefixes spell out phi-features on little v, which only enter into agreement relations with internal arguments.

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we review arguments that the segment i- that co-occurs with subject agreement prefixes is itself an object agreement marker in Mbyá Guaraní. In Section 3, we discuss cross-reference marking with converbs in more detail. Section 4 presents our analysis of Mbyá Guaraní alignment. Section 5 compares our proposal to Zubizarreta and Pancheva’s (2017) and Deal’s (2021) analyses. Section 6 concludes.

Unless stated otherwise, all examples in the following sections are from Mbyá Guaraní. Our primary source of data is Dooley’s (1991) description of Mbyá converbs and Dooley’s (2015) discussion of cross-reference marking in Mbyá. These examples are referenced as [D91] and [D15], respectively, after the translation line. These were supplemented by examples constructed by the second author of the manuscript, who is a native speaker of the language. These examples are referenced as [C] after the translation.

2. Object Marking

This paper focuses on the Mbyá variant of Guaraní. The basic cross-reference marking paradigm of Mbyá is identical to that of Paraguayan Guaraní (henceforth, PG), which was presented in the previous section. As in PG, with some transitive verbs, an additional prefix i- (or its allomorphs j- and nh-) attaches to the stem following a subject agreement prefix:

| 5. | A-i-nupã | ava |

| A3-AGR-hit | man | |

| ‘I hit the man.’ | ||

| 6. | A-j-apo | xe=r-o-rã |

| A3-AGR-build | B1SG=LK-house-FUT | |

| ‘I am building my house.’ | ||

In grammatical descriptions of PG, this segment has been analyzed as part of an allomorph of the subject prefix. Transitive verbs that are inflected with the additional segment are called aireales, while other verbs are called areales (see Estigarribia, 2020, pp. 133–135). We refer to this view as the aireal hypothesis:

| 7. | Paraguayan Guaraní (Estigarribia, 2020, p. 134, our glosses) | |

| Ai-pytyvõ | ichupe | |

| A1SG-help | to.him/her | |

| ‘I help(ed) him/her.’ | ||

By contrast, grammatical descriptions of Mbyá and Tupinambá as well as comparative Tupí–Guaraní (henceforth, TG) studies analyze the added segment and its cognates as object agreement prefixes (on Mbyá, see Dooley, 2015, §5.5 and Martins, 2004, §2.4.1; on TG morphosyntax and Tupinambá, see Jensen, 1987 and Rose, 2015, 2018). There are several pieces of evidence that support this analysis, which we review in this section.

Firstly, the additional segment is in complementary distribution with inactive markers that cross-reference the object. This follows straightforwardly if the segment is an object agreement prefix, under the assumption that it competes with inactive markers for object indexing on the verb. By contrast, the fact that only active markers are subject to allomorphy is not explained by the aireal hypothesis but merely stipulated.

| 8. | Ava | xe=(*i-)nupã |

| man | B1SG=(*OBJ-)hit | |

| ‘The man hit me.’ [C] | ||

Secondly, the additional segment is in complementary distribution with prefixes that bind the object, such as the reflexive prefix je-/nhe- and the reciprocal prefix jo-/nho-, as illustrated in (9). Likewise, the segment is in complementary distribution with valence increasing prefixes such as the causative prefix mo-/mbo- and the comitative causative prefix3 guero- and its allomorphs, as illustrated in (10). If the segment is an object agreement marker, this would follow from the hypothesis that valence changing prefixes and object agreement markers spell out the same functional head. In Section 4, we will argue that this is because object agreement markers spell out a transitive little vTR head and valency changing prefixes spell out a Voice head that is bundled with vTR (cf. Pylkkänen, 2008), thereby competing for exponence. It is unclear how the aireal hypothesis can explain the incompatibility of ai- allomorphs with valence-changing prefixes.

| 9. | a. | A-nhe-nupã | |

| A1SG-RELF-hit | |||

| ‘I hit myself.’ [C] | |||

| b. | O-nho-nupã | ||

| A3-RECIP-hit | |||

| ‘They hit one another.’ [C] | |||

| 10. | a. | A-mbo-’a | ava |

| A1SG-CAUS-fall | man | ||

| ‘I made the man fall.’ [C] | |||

| b. | A-guero-’a | ava | |

| A1SG-COM-fall | man | ||

| ‘I wrestled the man to the ground.’ [C] | |||

A potential objection to the analysis of the additional segment as an object marker is that it co-occurs with the portmanteau prefix ro-, which indexes a 1st person subject acting on a 2nd person object:

| 11. | Xee | ro-i-nupã |

| I | PORT-AGR-hit | |

| ‘I hit you.’ [C] | ||

If ro- spells out agreement with both the subject and the object, the additional segment cannot be an object agreement marker and should instead be analyzed as part of the aireal allomorph of the portmanteau prefix. To rebuke this objection, we point out that the portmanteau analysis of ro- has been challenged in several publications. Rose (2015, 2018) observes that the prefix ro- is independently attested as a first person plural exclusive agreement marker and that the so-called portmanteau ro- may be analyzed as a 1st person agreement marker that signals that the subject does not include the addressee in its extension. Zubizarreta and Pancheva (2017) on the other hand analyze portmanteau ro- as a contextual allomorph of the 1st person singular active agreement marker a- that is selected when the verb’s object is second person.4 In any case, it appears that ro- does not need to be analyzed as a true portmanteau prefix, i.e., a prefix that spells out subject and object agreement. Rejecting the portmanteau analysis of ro- allows us to maintain the analysis of the additional segment i- as an object agreement prefix, which in turn allows us to explain its complementary distribution with inactive object markers and valence changing prefixes.

An interesting consequence of this analysis is that the object agreement marker i- is attested both with 3rd person objects, as illustrated in examples (5) and (6), and with 2nd person objects, as illustrated in example (11). Consequently, we must assume that i- is underspecified for person. Far from being a liability, we will argue in Section 3 that this assumption allows us to make sense of the distribution of the prefix i- and its allomorphs in converbs.

The cross-referencing system of transitive verbs that we have arrived at is summarized in Table 1.5 For the sake of conciseness, nasal allomorphs of cross-reference markers are not represented in the table.

Table 1.

Transitive cross-reference marking (Dooley, 2015, p. 20).

As we noted in the introduction, 1st and 2nd person inactive markers are largely homophonous with free form personal pronouns, which are listed in Table 2. For this reason, 1st and 2nd person inactive markers have been argued to be clitic doubling,6 while active markers have been analyzed as agreement prefixes (see notably Jensen, 1998; Zubizarreta & Pancheva, 2017).

Table 2.

Personal pronouns (Dooley, 2015, p. 17).

Note that third person subjects of inactive intransitive verbs are cross-referenced either by the prefix i- and its allomorphs or by the prefix h-. However, neither of these prefixes is identical in form with the third person pronoun ha’e. This motivates their analysis as agreement prefixes rather than clitic doubling.

| 12. | a. | Kyringue | i-kane’õ | |

| children | B3-tired | |||

| ‘The children are tired.’ [C] | ||||

| b. | Yy | h-aku | ||

| water | B3-warm | |||

| ‘The water is warm.’ [C] | ||||

Jensen (1987) argues that the prefix h- is itself descended from an allomorph *c of the object marking prefix *i- in Proto-Tupí–Guaraní. This prefix is no longer attested as an object marking prefix in Mbyá Guaraní due to phonological change.7

In sum, there is evidence that the segment that is added to subject agreement markers in so-called aireales verbs is an object agreement prefix. This prefix is underspecified for person, since it can cross-reference either 2nd person or 3rd person objects. We now move to a discussion of the second phenomenon of interest in this study, namely converbs and their absolutive cross-reference marking pattern. We will see that in these constructions, object marking i- is also attested with first person objects, providing further support for our underspecification analysis.

3. Absolutive Cross-Reference Marking in Converbs

Tupí–Guaraní languages have a multi-verb construction that is referred to as a gerund (gerundio) in the Brazilian tradition of TG linguistics Rodrigues (1953) and that has alternatively been characterized as a double-verb construction (Dooley, 1991) or a serial-verb construction (Damaso Vieira & Baranger, 2021; Jensen, 1990; Velázquez-Castillo, 2004). In her description of Emerillon serialization, Rose (2009) notes that “from a cross-linguistics perspective, this construction may best be described as a converb.” We follow Rose’s suggestion in this paper and refer to said construction in Mbyá as a converb construction.

Converbs have been defined as dependent verb forms specialized for functions that are neither argumental nor adnominal (Haspelmath, 1995; Rapold, 2007). Mbyá converbs are dependent verbs formed from a closed class of intransitive active roots by adding the suffix -py or one of its allomorphs (-my/-ngy/-ny/-vy), as illustrated in Table 3. In addition, converbs can be transitivized with the causative prefix mbo- or the comitative causative prefix guero- and their allomorphs.

Table 3.

Converb roots.

While converbs cross-reference their arguments using active and inactive markers, the subjects and objects of converbs are obligatorily shared with the superordinate verb (Damaso Vieira & Baranger, 2021; Dooley, 1991). This constraint manifests itself notably in the ungrammaticality of transitive converbs combining with intransitive verbs:

| 13. | *A-a | mboka xe=r-er-a-vy | |

| A1SG-go | rifle | B1SG=COM-go-CONV | |

| Intended: ‘I left, taking the rifle with me.’ [C] | |||

The main feature of interest of Mbyá converbs for this study is that they only cross-reference their absolutive argument (Dooley, 1991, §4.3).8 Intransitive converbs cross-reference their subjects with active agreement prefixes, as illustrated by example (14):

| 14. | A-pu’ã | a-’ã-my |

| A1SG-stand.up | A1SG-stand-CONV | |

| ‘I stood up and stayed on my feet.’ [D91] | ||

Reflexive and reciprocal forms of transitive converbs are syntactically intransitive and also cross-reference their subject with active agreement prefixes:

| 15. | Ja-guata | ja-jo-guer-a-vy |

| A1.INCL-travel | A1.INCL-RECIP-COM-go-CONV | |

| ‘We accompanied each other as the travelled.’ [D91] | ||

By contrast, transitive converbs always cross-reference their object with inactive markers, regardless of the person of the subject. There are two types of transitive converbs in Mbyá: comitatives and simple causatives. Comitative converbs generally express that the subject accompanies the object in the action described by the verb (see Section 4.5 for a more in-depth discussion). These converbs show productive cross-referencing of their object with inactive markers:

| 16. | 3 → 1, object cross-referenced on converb: | ||

| Xe=r-u | xe-jopy | xe=r-er-a-vy | |

| B1SG=LK-father | B1SG-get | B1SG=LK-COM-go-CONV | |

| ‘My father got me and took me with him.’ [D91] | |||

| 17. | 1 → 3, object cross-referenced on converb: | ||||

| Xe=r-o | py=gua | kuery | a-r-u | h-ero-kua-py | |

| B1SG=LK-house | LOC-NMLZ | COL | A1SG-COM-come | B3-COM-be.PL-CONV | |

| ‘I brought all of the inhabitants of my house as a group.’ [D91] | |||||

Transitive converbs derived by simple causativization also fail to cross-reference their subject, but show defective object agreement instead: the inactive agreement prefixes i- or h- are always prefixed to the stem regardless of the person and number of the object, as illustrated by examples (18) and (19).

| 18. | 3 → 1, inactive i- marker prefixed to converb: | ||

| Xe=r-u | xe=mo-pu’ã | i-mo-’ã-my | |

| B1SG=LK-father | B1SG-CAUS-rise | AGR-CAUS-stand-CONV | |

| ‘My father made me rise and stand up.’ [D91] | |||

| 19. | 1 → 3, inactive i- marker prefixed to converb: | ||||

| Che=r-a’y | a-mo-nge | i-nõ-ngy | t-upa | r-upi | |

| B1SG=LK-son | A1SG-CAUS-sleep | B3-CAUS.lie-CONV | T-bed | LK-along | |

| ‘I put my son to sleep, making him lie down in the bed.’ [D91] | |||||

In Section 2, we analyzed the prefix i- as an object agreement prefix underspecified for person. The assumption that it is underspecified was motivated by the co-occurrence of the object marker prefix with the so-called portmanteau prefix ro- in the presence of a 1st person subject and a 2nd person object. The defective agreement pattern of causative converbs further supports this analysis.

In sum, we observe that Mbyá converbs display an absolutive cross-reference marking pattern, whereby only subjects of intransitive converbs or objects of transitive converbs are cross-referenced. In addition, absolutive cross-reference marking on causative converbs is underspecified for person.

Before we close this section, it is worth noting that converb constructions with absolutive alignment are attested across the Tupí–Guaraní family, as the following examples illustrate (see Jensen, 1990 for discussion):

| 20. | Tupinambá (Jensen, 1990) | |

| O-úr | i-kuáp-a | |

| A3-come | B3-meet-CONV | |

| ‘He came to meet him.’ | ||

| 21. | Kamaiura (Seki, 2000) | |

| A-jot | i-mo’e-m | |

| A1SG-come | B3-teach-CONV | |

| ‘I came to teach him.’ | ||

| 22. | Tapirape (Leite, 1987) | |||

| Wyrã’i | ara-pyyk | i-xokã-wo | i-’o-wo | |

| bird | A1.EXLC-catch | B3-kill-CONV | B3-eat-CONV | |

| ‘We caught the bird, killed it and ate it.’ | ||||

| 23. | Wayampi (Jensen, 1990) | |

| A-akã-nupã | i-juka | |

| A1SG-head-hit | B3-kill | |

| ‘I hit it on the head to kill it.’ | ||

Absolutive cross-reference marking is also attested in other constructions across the TG family so much so that Jensen (1998) argues that in Proto-Tupí–Guaraní, not only converbs but all other dependent verb forms were subject to absolutive alignment (this includes verbs in adverbial subordinate clauses, serial verb constructions and nominalizations).9

In other words, there is ample crosslinguistic and historical support for Dooley’s (1991) description of cross-reference marking on Mbyá converbs as an absolutive system.

4. Revised Analysis of Argument Indexing

4.1. Basics of Verbal Argument Structure and Cross-Reference Marking

We adopt a constructivist approach to event and argument structure (Marantz, 2013). Predicative roots are categorized as verbs by a little v head, and internal arguments are introduced within little vP. External arguments are introduced by a Voice head (Kratzer, 1996; Pylkkänen, 2008). As we will argue in Section 4.3, Mbyá Guaraní is a ‘bundling language,’ where Voice and little v are spelled out as a single argument (cf. Pylkkänen, 2008). We adopt a spanning view of Voice bundling, whereby Voice and little v are syntactically separate heads that are spelled out by as one (Svenonius, 2012).

Infl(ection) is located above the Voice/vP domain. Following Ritter and Wiltschko (2014), we assume that the function of Infl is to anchor the clause in the utterance context by tying it to a deictic category such as person, location or time. Languages differ in the range of categories used for anchoring. English uses time (anchoring with respect to the time of utterance), which manifests itself in the use of tense features on Infl. In Guaraní languages, by contrast, verbs are not inflected for tense, mood or aspect but only for person (and number), via active agreement prefixes. We take this as an indication that the anchoring category for Guarani is person, and that agreement prefixes spell out person features on Infl.

Given these assumptions, the basic structure of a transitive clause would be represented as follows, where DPint is the internal argument of the verb, DPext its external argument and V is the verb root:

| 24. | [IP DPext [ Infl [VoiceP DPext [ Voice [vP v [VP V DPint ]]]]]] |

In Section 1 and Section 2, we established that active agreement prefixes only cross-reference subjects of active intransitive verbs or subjects of transitive verbs. Subjects of inactive intransitive verbs and objects that outrank subjects on the person hierarchy are cross-referenced by inactive cross-reference markers, which we analyze as clitic doubling. This complementary distribution suggests that active agreement prefixes and clitic doubling compete for the morphological expression of person features on Infl. By contrast, the underspecified object agreement prefix i- and its allomorphs co-occur with subject agreement prefixes on transitive verbs. This suggests that this prefix spells out the person features of a different functional head, which we take to be a transitive little v head.

In the next subsection, we present a detailed analysis of the agreement relation between these functional heads and the verb’s core arguments. This analysis should account not only for the basic paradigm of active–inactive and hierarchical cross-reference marking of Guaraní languages but also for the distribution of object markers and the absolutive pattern of cross-reference marking in converbs.

4.2. Modeling Agreement in Independent Clauses

We adopt Deal’s (2021) theory of Agree with Interaction and Satisfaction features. Syntactic probes are characterized by two conditions: Interaction specifies the features α that a probe will copy when it finds them on a goal in its search domain. Satisfaction specifies the features β that will halt the search once the probe finds them. We can represent these two conditions as follows: [INT: α, SAT: β]. The search domain of a probe is (simplifying somewhat) its c-command domain, subject to relativized minimality, i.e., a probe will always interact with the closest goals in its c-command domain before interacting with more distant goals. Deal assumes that although Agree is an obligatory operation, its failure does not necessarily trigger ungrammaticality (cf. Preminger, 2015).

In Mbyá, Infl and transitive little v heads probe for person and number features.10 Following Harley and Ritter (2002) and Béjar and Rezac (2009) among others, Deal adopts a hierarchical decomposition of Φ-features. In Mbyá, person is structured as follows, and all person and number features are furthermore subsumed under a [Φ] root feature:

| 25. | 1P = [speaker, participant, person] | (for conciseness: [SPK, PRT, PER] or [1]) |

| 2P = [participant, person] | (for conciseness: [PRT, PER] or [2]) | |

| 3P = [person] | (for conciseness: [PER] or [3]) |

As is customary in Distributed Morphology, a feature combination A is said to be more specific than a feature combination B if and only if B is a proper subset of A. Accordingly, 3rd person is the least specific feature combination, followed by 2nd person and then 1st person.

Hierarchical cross-reference marking in Mbyá follows from the assumption that Infl interacts with [Φ] but is satisfied by [speaker], together with the observation that subjects are generated in the specifier of VoiceP and objects are generated inside little vP: (i) If Infl finds a 1st person goal in the specifier of VoiceP, it will agree with it and no other goal will be probed. This results in cross-referencing the 1st person subject. (ii) If Infl finds a 2nd person goal in the specifier of VoiceP, it will continue its search. If the object is 1st person, Infl will agree with the more specific object. This results in cross-referencing the 1st person object. Otherwise, the object is 3rd person.11 In that case, all person features on the object are also present on the 2nd person subject, therefore Infl does not copy any new person features from the object. This results in cross-referencing the 2nd person subject. (iii) If Infl finds a 3rd person goal in the specifier of VoiceP, it will probe the object and copy its [participant] and [speaker] features, if any are present, which results in cross-referencing the object. If both the subject and the object are 3rd person, Infl will probe both the subject and the object but will not copy any person features from the object that was not already copied from the subject. This results in cross-referencing the subject.

One complication is that the source of person features on Infl affects their morphological realization: while person features that are copied from subjects are spelled out as agreement prefixes, person features that are copied from objects are spelled out through clitic doubling. To explain this, we hypothesize that the morphological realization of person feature on Infl is sensitive to Case. While this assumption may seem stipulative, we will see in Section 4.4 that it supports a unified analysis of hierarchical cross-reference marking in independent clauses and absolutive cross-reference marking in converbs.

We adopt Legate’s (2008) theory of Case assignment. For nominative–accusative systems, Legate simply argues that Infl assigns nominative Case to subjects while little v assigns accusative Case to objects:

- 26.

- Nominative–accusative Case assignment:

- •

- Infl assigns nominative Case to subjects;

- •

- Little v assigns accusative Case to objects.

Coming back to Mbyá, under the assumption that Case assignment follows a nominative–accusative pattern in independent clauses, the fact that person features on Infl are spelled out as agreement prefixes only if they were copied from a subject can be captured as a constraint that ties morphological realization to Case assignment:12

| 27. | Case dependence of agreement in Mbyá: |

| Φ-features on Infl can only be spelled-out as agreement prefixes if a nominative DP with matching Φ-features is present in the specifier of InflP. |

We can implement (27) through contextual allomorphy in Distributed Morphology (Halle & Marantz, 1993), by requiring that person features on Infl be spelled out only if a nominative DP with matching features is present in the specifier of InflP. This is illustrated in (28) with Vocabulary Insertion rules for a subset of agreement prefixes:13

| 28. | a. | 1st SG agreement prefix insertion (preliminary version): |

| a- ↔ Infl[1,SG] / [InflP DP[1, SG, NOM ] __ [ …]] | ||

| b. | 2st SG agreement prefix insertion: | |

| re- ↔ Infl[2, SG] / [InflP DP[2, SG, NOM ] __ [ … ]] | ||

| c. | 3rd agreement prefix insertion: | |

| o- ↔ Infl[3] / [InflP DP[3, NOM ] __ [ …]] |

Object cross-reference marking, on the other hand, is realized by clitic doubling. Following Preminger (2019), we assume that clitic doubling is licensed by agreement. More precisely, clitic doubling in Mbyá is non-local head-movement of an object D to Infl, which is licensed by interaction between Infl and the phrase headed by D. Crucially, this movement occurs before spell-out. Consequently, the morphological realization of clitic doubling is subject to Vocabulary Insertion rules that reference Infl as shown in (29):

| 29. | a. | 1st SG clitic doubling insertion: |

| xe= ↔ [Infl D[1,SG] Infl[1,SG] ] | ||

| b. | 2st SG clitic doubling insertion: | |

| nde= ↔ [Infl D[2,SG] Infl[2,SG] ] |

Because clitic doubling and agreement prefixes compete for the morphological realization of Infl, exponent selection will be subject to the Subset Principle, and speakers will choose the most specific candidate.

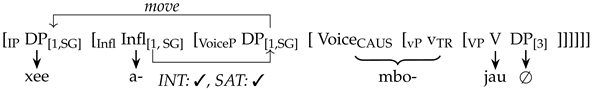

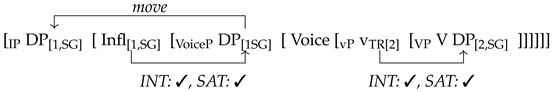

We are now in a position to provide a detailed account of hierarchical cross-reference marking in independent clauses. Consider first the case where the subject outranks the object. In (30), Infl agrees with a 1st person subject base generated in the specifier of VoiceP, copying its [1, SG] features, i.e., [SPK, PRT, PER, SG]. This satisfies Infl and no further probing takes place. After movement of the subject to the specifier of InflP, the [1, SG] features on Infl are in a configuration that licenses their spelling out as an agreement prefix, in accordance with rule (28). Since Infl does not agree with the object, clitic doubling cannot take place:

| 30. | a. | Xee | a-mbo-jau |

| I | 1SG-CAUS-bathe | ||

| ‘I bathe her/him/it/them.’ [C] | |||

| b. |  | ||

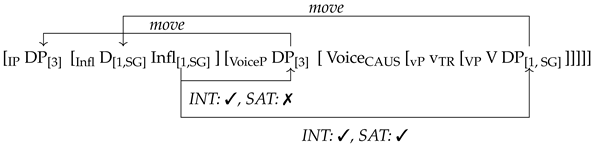

Next, consider the case where the object outranks the subject. In (31), Infl agrees with the 3rd person subject, copying its [3] feature, i.e., [PER]. Since the Satisfaction condition on Infl is not met, Infl further agrees with the object, copying its [1, SG] features. That is to say, [SPK, PRT, SG] are added to the [PER] feature already present on Infl. At spell-out, the 3rd person nominative DP in the specifier of InflP matches the features present on Infl. Consequently, the Φ-features on Infl could be realized by the 3rd person agreement prefix o- per rule (28c). However, rule (29a) also applies and is more specific, which results in spelling out Φ-features on Infl through clitic doubling:

| 31. | a. | Ha’e | xe=mbo-jau |

| 3 | B1SG=CAUS-bathe | ||

| ‘She/he/they bathe me.’ [C] | |||

| b. |  | ||

4.3. Object Marking with Underspecified Agreement Prefixes

In Section 4.2, we offered an account of active and inactive cross-reference marking in transitive verbs that focuses on subject agreement and clitic doubling. This account does not explain why an underspecified object agreement marker co-occurs with subject agreement prefixes on some transitive verbs, as described in Section 2.

We propose that underspecified object agreement prefixes spell out a transitive little vTR head. Unlike Infl, little vTR interacts with and is satisfied by [person], i.e., it is specified as [INT: person, SAT: person]. Consequently, little vTR will always agree with the object and will never trigger cyclic expansion. The derivation is straightforward when the subject outranks the object on the person hierarchy, as in example (32). In this case, Infl agrees with the subject and is spelled out as an agreement prefix as outlined in Section 4.2. Little vTR agrees with the 3rd person object:

| 32. | a. | A-i-nupã | ava | r-akã |

| A1SG-AGR-hit | man | LK-head | ||

| ‘I hit the man’s head.’ [C] | ||||

| b. |  | |||

The fact that not all transitive verbs bear object agreement prefixes can be captured as a lexical constraint, implemented as a contextual restriction on Vocabulary Insertion:14

| 33. | a. | -i ↔ vTR[person] / [ __ [ NUPÃ, etc ]] | |

| b. | ∅↔ vTR[person] | (elsewhere case) |

This analysis faces a complication when the object outranks the subject on the person hierarchy. In that case, both Infl and vTR agree with the object. Therefore, one might expect that clitic doubling should co-occur with an object agreement prefix. This prediction is not borne out since in that case the object is only cross-referenced by clitic doubling. This configuration is illustrated in (34).15

| 34. | a. | Nde | che=nupã |

| You | B1SG-hit | ||

| ‘You hit me.’ [C] | |||

| b. |  | ||

We suggest that in such configurations, the morphological realization of Φ-features on vTR is blocked by a morphological filter that bans the exponence of multiple sets of person features that were valued from the same goal. In such cases, the most informative exponent is preserved, which corresponds to clitic doubling on Infl. We can also implement this filter through contextual allomorphy:

| 35. | Double exponence filter: |

| ∅↔ vTR[α] / [ [Infl D[α] Infl[α]] [ Voice [ _ [ …]]]] |

Note that the double exponence filter does not block co-occurrence of the so-called portmanteau prefix with an object agreement marker, under the assumption that this prefix really is an allomorph of the first person subject agreement prefix. A relevant example is provided in (36), where the prefix ro- marks agreement with a first person subject in the context of a second person object:

| 36. | a. | Chee | ro-i-nupã |

| I | PORT-AGR-bathe | ||

| ‘I hit you.’ [C] | |||

| b. |  | ||

A revised Vocabulary Insertion rule for 1st person features in Infl that captures the relevant allomorphy is given in (37). Under this analysis, ro- spells out 1st person features on the Infl head in the context of a second person object in its scope. Since in that case the features on Infl and little vTR are valued by different DP, the double filter exponence does not apply and the person feature on vTR may be spelled out as an object agreement prefix:

| 37. | a. | ro- ↔ Infl[1,SG] / [InflP DP[1,SG,NOM ] __ [VoiceP Voice [vP vTR [VP V DP[2,SG] ]]]] |

| b. | a- ↔ Infl[1,SG] / [InflP DP[1, SG, NOM ] __ [ …]] |

As discussed in Section 2, the proposed analysis of object marking explains the complementary distribution of object markers with valency increasing and decreasing prefixes, which we take to spell out Voice heads. Indeed, since Voice is bundled with little vTR, valency-changing prefixes compete with object agreement prefixes for the morphological realization of the bundled head. The analysis of Mbyá as a Voice bundling language is supported mainly by the observation that verbalizing and causativizing heads are spelled out jointly (cf. Harley, 2017). Indeed, mbo- can be prefixed to nominal roots, which verbalizes the root and causativize it in the same process. This is illustrated by examples (38a) and (38b), where mbo- verbalizes the nominal phrase kupe arygua (‘saddle’) and causativizes it at the same time:

| 38. | a. | kupe | ary-gua | ||

| rib | on.top-NMLZ | ||||

| ‘saddle’ (lit. ‘thing that comes on top of the ribs’) [D15] | |||||

| b. | Ava | o-mbo-kupe | ary-gua | kavaju | |

| man | A3-CAUS-rib | on.top-NMLZ | horse | ||

| ‘The man saddled the horse.’ [D15] | |||||

4.4. Cross-Reference Marking in Converbs

In Section 3, we established that cross-reference marking in converbs follows an absolutive pattern, whereby only intransitive subjects or objects may be cross-referenced. We propose that the source of this variation is a split in the grammar of case assignment in the language, which we locate in the grammar of little vTR, following Legate (2008). More specifically, we propose that converbs follow an ‘absolutive as default’ patterns in Mbyá, as spelled out in (39):

- 39.

- Matrix clauses (nominative–accusative):

- •

- Infl assigns nominative Case to subjects

- •

- Little vTR assigns accusative Case to objects

Converbs (absolutive as default):- •

- Infl assigns nominative Case to intransitive subjects

- •

- Little vTR assigns inherent ergative Case to subjects and accusative Case to objects

This proposal is supported by diachronic studies of alignment in Tupí–Guaraní languages, which have argued that Proto-Tupí–Guaraní made use of a nominative–accusative alignment in matrix clauses and ergative-absolutive alignment in subordinate clauses Jensen (1990, 1998). In modern Tupí–Guaraní languages, various types of subordinate constructions would have preserved ergative–absolutive features, including converbs (Rose, 2009).

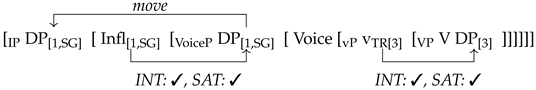

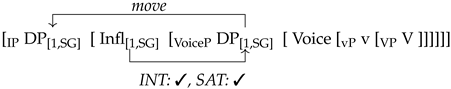

Under this analysis, subjects of intransitive converbs are nominative, hence they may be cross-referenced with agreement prefixes even if the Case dependence of agreement is active in converbs. This is indeed the case, as shown by example (40):

| 40. | a. | A-pu’ã | a-’ã-my |

| A1SG-stand.up | A1SG-stand-CONV | ||

| ‘I stood up and remained on my feet.’ [D91] | |||

| b. |  | ||

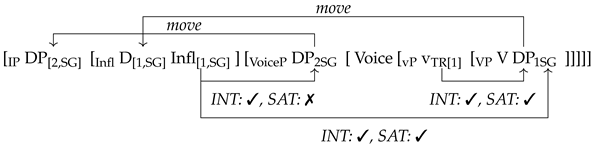

By contrast, because subjects of transitive converbs are ergative, they cannot be cross-referenced by agreement prefixes (recall from Section 3 that all converb roots are intransitive, and transitive converbs are derived either by simple causativization or by comitative transitivization). If the object is higher than the subject on the person hierarchy, this gap does not manifest itself morphologically, since in that case the object is cross-referenced by clitic doubling, just as in matrix clauses. This is illustrated by example (41):

| 41. | 3 → 1, object cross-referenced on converb: | ||

| Xe=r-u | xe-jopy | xe=r-er-a-vy | |

| B1SG=LK-father | B1SG-get | B1SG=COM-go-CONV | |

| ‘My father got me and took me with him.’ [D91] | |||

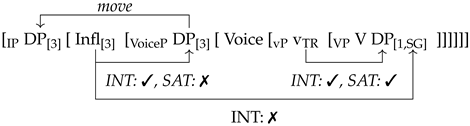

If on the other hand the subject outranks the object, Infl copies its Φ-features from the subject, but these features cannot be spelled out as agreement prefixes, since the subject is ergative. In that case, we may expect either absence of agreement morphology or resort to an underspecified agreement marker. It is the second option that is attested in Mbyá: whenever the subject of a transitive converb outranks its object, the subject is cross-referenced using the underspecified agreement prefix i- or its allomorph h- regardless of the person of the subject. This is shown in (42) and (43), where the subject of the converb is 1st person and its object is third person:

| 42. | Mboka | a-jopy | h-er-a-vy |

| Rifle | A1SG-take | B3-COM-go-CONV | |

| ‘I took my rifle and went off uninterruptedly.’ [D91] | |||

| 43. | Xe=r-a’y | a-mo-pu’ã | i-mo-’ã-my |

| B1SG=LK-son | A1SG-CAUS-rise | B3-CAUS-stand-CONV | |

| ‘I made my son stand up.’ [D91] | |||

4.5. Defective Cross-Reference Marking with Simple Causative Converbs

In Section 2, we observed that object cross-referencing with clitic doubling is unattested with simple causative converbs, unlike with comitative causative converbs. This was illustrated by the contrast between (16) and (18), which we repeat here as (44) and (45):

| 44. | 3 → 1, object cross-referenced on comitative converb: | ||

| Xe=r-u | xe-jopy | xe=r-er-a-vy | |

| B1SG=LK-father | B1SG-get | B1SG=COM-go-CONV | |

| ‘My father got me and took me with him.’ [D91] | |||

| 45. | 3 → 1, inactive i- marker prefixed to causative converb: | ||

| Xe=r-u | xe=mo-pu’ã | i-mo-’ã-my | |

| B1SG=LK-father | B1SG-CAUS-rise | AGR-CAUS-stand-CONV | |

| ‘My father made me rise and stand up.’ [D91] | |||

In order to explain the absence of clitic doubling with simple causative converbs, we hypothesize that ergative little vTR is a strong phase head. Since the object is generated in the complement of vTR, Infl cannot probe person features on the object through the strong phase boundary. This is illustrated in (46). Since the object is inaccessible to Infl, Infl cannot agree with it and clitic doubling is not licensed.

| 46. | Causative converb structure, 3 → 1: |

|

An obvious issue with this analysis is that it also appears to block clitic doubling with comitative causatives, contrary to facts. We must therefore explain why the object of comitative causatives remains accessible to the Infl probe. We believe that the answer to this question lies in the semantics of comitatives. In comitative causatives, the subject causes the object to participate in an event along with them (Dooley, 2015, §13.2.6). To illustrate, the comitative causative form (gue)ru (‘bring’) derived from the root u (‘come’) conveys that the subject causes the object to come to a place along with them. There is however evidence that the object is not generated as the internal or external argument of the verb stem, but rather as an applicative argument. This is most evident with comitative causatives of psych-verbs, whose object denotes stimulus arguments that would be realized by prepositional phrases in the non-comitative form of the verb, as illustrated in (47):

| 47. | a. | Xee | a-vy’a | kyxe | re |

| B1SG | A1SG-rejoice | knife | at | ||

| ‘I rejoiced at the knife.’ [D15: §13.2.6] | |||||

| b. | Xee | a-ro-vy’a | kyxe | ||

| B1SG | A1SG-COM-rejoice | knife | |||

| ‘I enjoyed the knife.’ [D15: §13.2.6] | |||||

The point of this example is that vy’a is an intransitive verb that selects an experiencer argument. Clearly, kyxe in (47b) cannot be understood as a causee argument of vy’a, since it cannot be understood as an experiencer. We conclude that kyxe is instead introduced by the comitative prefix ro- as an applicative object. Such syncretism between causative and applicative is frequent cross-linguistically and is commonly analyzed as the result of comitative extensions of causative forms (Shibatani & Pardeshi, 2002). South American languages stand out in this typology because many of these languages possess markers dedicated to the expression of comitative causatives, rather than causative morphemes that include comitative causation as one of their functions (Guillaume & Rose, 2010). This includes the Mbyá Guaraní prefix ero- and its cognates in Tupi Guaraní languages (ibid., p. 386).

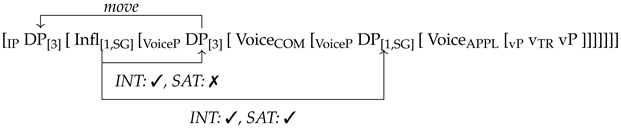

Coming back to the topic of cross-reference marking in converbs, the applicative status of objects of comitative causatives explains why they remain accessible to the Infl probe despite the presence of a strong phase boundary created by vTR. Indeed, if the comitative prefix introduces the applicative object and well as the subject, both arguments are introduced at least as high as the specifier of vTR, and are therefore accessible for probing by Infl. More precisely, we propose that the comitative causative prefix spells out a sequence of two Voice heads,16 the lower of which introduces the applicative object, while the higher head introduces the subject. This is illustrated in (48), which presents the structure of the comitative converb from example (44):

| 48. | Comitative converb structure, 3 → 1: |

|

In this structure, the lower vP denotes the event described by the bare verb stem (in example (44), an event of going), and does not introduce any argument. Little vTR introduces the causing event and VoiceAPPL introduces the applicative object of the comitative construction. VoiceCOM introduces the subject of the comitative construction and marks it both as the causer argument and as the proto-agent of the caused event. Crucially, after Infl probes the phi-feature on the specifier of VoiceCOM, the specifier of VoiceAPPL remains accessible for further probing. When the object outranks the subject on the person hierarchy, as in this example, Infl can agree with the object and its person features can be spelled out by clitic doubling.

5. Comparison to Previous Analyzes

We now compare our proposal to two recent analyses of the cross-referencing system of languages closely related to Mbyá Guaraní: Paraguayan Guaraní (Zubizarreta & Pancheva, 2017) and Tupinambá (Deal, 2021).

5.1. dos Santos (2025)

Our proposal shares important features with dos Santos’s (2025) analysis of the agreement system of Kawahíva, a Tupí–Guaraní language spoken in the states of Amazonas, Matro Grosso and Rondônia in Brazil. Like Mbyá, Kawahíva shows a split between matrix and dependent clauses in terms of agreement patterns. In matrix clauses, verbs can agree with either subjects or objects following a person hierarchy (1 > 2 > 3), while in dependent clauses only object agreement is possible. In addition, object agreement in matrix clauses in only attested when the verb or the internal argument is realized clause initially. Dos Santos analyzes this as evidence that subject agreement is hosted in the CP domain, which is absent in dependent clauses, while object agreement is hosted on a little v probe that is underspecified for person features. This aligns with our analysis of Mbyá converbs—we have argued that the absence of subject agreement in converbs follows from their truncated structure and the Case-sensitivity of agreement. The key difference is that in Mbyá, the truncation manifests as ergative Case assignment rather than the complete absence of subject agreement projections. In addition, we have also proposed a flat probe on little v to account for the distribution of the default agreement marker i-.

5.2. Zubizarreta and Pancheva (2017)

One of the main goals of Zubizarreta and Pancheva (2017) is to present a semantically substantive theory of agreement phenomena in Paraguayan Guaraní (PG). Zubizarreta and Pancheva argue that both Infl and little v probe for person features in their c-command domain, and little v acts as a strong phrase head that blocks probing by Infl inside little vP, except at its edge. Furthermore, taking inspiration from Ritter and Wiltschko’s (2014) work, they propose that Infl has interpretable person features in PG, which departs from standard assumptions about AGREE. Another important aspect of Zubizarreta and Pancheva’s proposal is the P-constraint on phases, which applies to phases that contain a D specified for 1st or 2nd person features ([+participant] in the authors’ feature geometry). The effect of the constraint is to move a 1st or 2nd person D to the edge of the phase that contains it. In PG, priority is given to 1st person. In effect, this guarantees that if a verb has a 1st or 2nd person object, this object will be moved to the edge of little vP and therefore accessible for probing by Infl.

Given these assumptions, Zubizarreta and Pancheva explain the hierarchical cross-referencing system of PG as follows. When the object does not outrank the subject, Infl probes for person features on the subject in the specifier of little vP. The subject meets the P-constraint requirement for both the v-phase and the Infl-phase and the person features on Infl are spelled out as agreement prefixes. If the object outranks the subject, the object is promoted to the edge of the v-phase and accessible for probing by Infl. Consequently, the object is also promoted to the edge of the Infl-phase where it cliticizes onto Infl.

In cases where the subject is 1st person and the object is 2nd person, the authors assume that Infl agrees with the 1st person subject, which is spelled out as a portmanteau prefix using a rule of contextual allomorphy.

Our analysis takes inspiration from Zubizarreta and Pancheva in having both Infl and little v as probes, and in exploiting the mechanism of strong phases to constrain agreement in converbs. However, we depart from them in using a theory of agreement that eschews the assumption that person features are interpretable on Infl. More importantly, Zubizarreta and Pancheva (2017) do not discuss object marking prefixes and assume that these prefixes are actually part of allomorphs of active agreement prefixes, following the aireal hypothesis that is dominant in the literature on Paraguayan Guaraní. We consider it an open question whether i- should also be analyzed as an object agreement prefix in Paraguayan Guaraní. Another major difference between our proposal and Zubizarreta and Pancheva’s (2017) analysis is that these authors do not discuss converb constructions. While there is a cognate construction with the suffix -vo in Paraguayan Guaraní, this construction does not appear to have absolutive agreement (see Velázquez-Castillo, 2004, Section 3.1 and footnote 6). Therefore, our analysis presumably does not extend to Paraguayan Guaraní in this respect.

5.3. Deal (2021)

Deal (2021) introduces the theory of Interaction and Satisfaction that we used in our analysis, and sketches an analysis of agreement Tupinambá, another Tupí–Guaraní language whose cross-reference system is similar to that of Mbyá. It should be noted that Tupinambá is one of many languages discussed in Deal’s (2021) paper and the author doesn’t intend to give an exhaustive account of cross-reference marking in this language.

Deal proposes that subject and object cross-reference marking in Tupinambá spell out person features on a single little v head. This contrast both with Zubizarreta and Pancheva’s (2017) analysis and with ours. Deal’s analysis is illustrated with examples (49) to (51) below. In (49), the subject is 3rd person and therefore only specified for Φ-features, while the object is 1st person and therefore also specified for participant (PART) and speaker (SPKR) feature. Little v is specified for Φ as its Interaction feature and SPKR as its satisfaction features. Consequently, upon agreeing the 1st person object, little v stops its probing and is subsequently spelled out as 1st person.

| 49. | a. | syé=repyák |

| 1SG=see | ||

| ‘He/She/It/They/You saw me.’ (Deal, 2021) | ||

| b. | [vP S[Φ] [ v [ V O[Φ,PART,SPKR] ]]] |

In (50), by contrast, the object is 3rd person and the subject is 1st person. Little v agrees with the object but fails to be satisfied, following which the probe reprojects and extends its probing cycle upwards in the syntactic structure, where it probes the 1st person subject which satisfies it and stops the probing. Each projection of the probe is spelled out according to the person feature specification of the argument it agreed with: 3rd person for the object and 1st person with the subject.

| 50. | a. | a-i-kutúk |

| 1SG-3-pierce | ||

| ‘I pierced him/her/it/them.’ (Deal, 2021) | ||

| b. | [vP S[Φ,PART,SPKR] [ v [ V O[Φ] ]]] |

Example (51) illustrates an ungrammatical example in which little v would continue to probe for Φ-features after agreeing with a first person object. This is ruled out by the satisfaction mechanism in Deal’s theory:

| 51. | a. | *syé=i-(r)epyák |

| 1SG=see | ||

| Intended: ‘He/She/It/They/You saw me.’ (Deal, 2021) | ||

| b. | [vP S[Φ] [ v [ V O[Φ,PART,SPKR] ]]] |

Deal’s analysis accounts elegantly for the Tupinambá data she discusses. However, we believe that using a single probe is insufficient to account for the distribution of object marking prefixes. Indeed, it is unclear how to account for the complementary distribution of object agreement prefixes with valency changing prefixes under this assumption. In our analysis, this complementary distribution is explained by the competition between valency changing prefixes and object agreement prefixes for the realization of little v, but this explanation is only possible under the assumption that subject agreement prefixes and object clitic doubling spell out another functional head, namely Infl. In this respect, we side with Zubizarreta and Pancheva (2017).

Using a single probe is also incompatible with our analysis of absolutive cross-reference marking in converbs. Our analysis relies on the assumption that the morphological realization of person features on Infl is only possible when these features are copied from a DP with nominative Case. We assume that subjects of intransitive converbs are assigned nominative Case by Infl while subjects of transitive converbs are assigned ergative Case by vTR, which explains why converbs agree with the former but not with the latter. It is unclear to us whether this analysis could be maintained under the assumption that only little v probes for person features on subjects and objects. Nevertheless, while we depart from Deal’s (2021) analysis in positing that not only little v but also Infl probe for phi-features, we believe that our account of cross-reference marking in Mbyá is largely compatible with her general theory of agreement.

6. Conclusions

This paper has revisited the cross-reference marking system of Mbyá Guaraní, focusing on two phenomena: double agreement using the object agreement prefix i- and absolutive cross-reference marking in converbs. Our analysis has demonstrated that cross-reference marking is sensitive to abstract Case in Mbyá, building on a view of agreement as an obligatory operation whose failure does not result in ungrammaticality.

We argued that the segment i- is an object agreement prefix that is underspecified for person, allowing it to cross-reference both 2nd and 3rd person objects. Additionally, we showed that converbs in Mbyá Guaraní follow an absolutive cross-reference marking pattern, where only intransitive subjects or objects are cross-referenced. This pattern aligns with historical and cross-linguistic data from the Tupí–Guaraní family.

Our contributions include the proposal that agreement in Mbyá is sensitive to Case, with active agreement prefixes realizing agreement with nominative DPs only. We also emphasized the different roles of Infl and little v as probes for person features, with little v being underspecified and not triggering cyclic expansion. Furthermore, we provided a unified framework that accounts for both hierarchical cross-reference marking in independent clauses and absolutive marking in converbs, supported by the assumption of Case dependence of agreement.

This study enhances our understanding of the complex agreement mechanisms in Mbyá Guaraní and contributes to broader discussions on cross-reference marking in Tupí–Guaraní languages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T.; Formal analysis, G.T. and A.I.; Investigation, G.T. and G.D.; Writing—original draft, G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| A1SG | First person singular, active class |

| B1SG | First person singular, inactive class |

| AGR | Agreement |

| CAUS | Causative |

| COL | Collective |

| COM | Comitative |

| CONV | Converb |

| EXCL | Exclusive |

| FUT | Future |

| INCL | Inclusive |

| LK | Linker |

| LOC | Locative |

| NMLZ | Nominalization |

| PE | Post-position pe |

| PL | Plural |

| PORT | Portmanteau prefix |

| RECIP | Reciprocal |

| T | Non-possessed marker |

Notes

| 1 | In Paraguayan Guaraní, the prefix po- is used also used for 1st person plural subjects acting on second person objects. This is unattested in Mbyá Guaraní and therefore will not be relevant for this paper. |

| 2 | Deal (2021) does take object marking into consideration in her analysis of Tupinambá, although she does not discuss the distribution of the prefix in detail. |

| 3 | Comitative causative prefixes increase the valency of a construction, like causative prefixes. In addition, they convey that the subject accompanies the object in the action described by the verb. Comitativity is discussed in more detail in Section 4.5, where we discuss the structure of comitative causative converbs in Mbyá. |

| 4 | In Paraguayan Guaraní, there would be an additional allomorph po- when the object is second person plural. |

| 5 | The row and column headers indicate the person, number and clusivity of the subject and object, respectively. The cells indicate the cross-reference marking form attested for each combination of subject and object. Note that reflexive verbs are derived by a special voice prefix and cross-reference their subjects like intransitive active verbs, hence the gap in the table. The object marking prefix i- is written in parentheses in the table, since it is not attested with all verbs. |

| 6 | If 1st and 2nd person inactive markers are clitics, insofar as they can co-occur with overt subjects or objects (see e.g., 1b), then these clitics must be said to double an argument that can be overtly realized. Of course, since core arguments are often implicit in the language (i.e., pro-drop is frequent), the doubling will often not be visible. |

| 7 | Both i- and h- were attested as object marking prefixes in Old Guaraní, a variant of Guaraní that was spoken in the Jesuitic missions in the 17th and 18th centuries. de Montoya (1724) calls them relacíon and discusses their distribution in great detail (see notably de Montoya, 1724, Part 3, ch. 2, §1-5 and §9; ch. 3 §1), supporting Jensen’s (1987) analysis. |

| 8 | In their discussion of Mbyá converbs (which they analyze as serial verb constructions), Damaso Vieira and Baranger (2021: §5.3) write that “in relation to the personal morphology, supplementary and subordinate verbs follow the same rules of independent clause verbs, not the absolutive pattern found in the original gerundive forms, employed in other languages of the group.” On a first, reading, this appears to contradict Dooley’s (1991) description. Indeed, Dooley states very clearly that Mbyá converbs, which he refers to as “V2s,” have absolutive agreement: “V2s agree only with the absolutive argument” (Dooley, 1991, p. 46). Dooley also provides a wealth of examples that support this conclusion, some of which are reproduced in Section 3 of our manuscript. On a closer reading of Damaso Vieira and Baranger (2021), it appears that what these authors mean is that Mbyá converbs do not use only inactive cross-reference markers but also make use of active markers. This contrasts with the cross-reference marking system of converbs in Proto-Tupí–Guaraní and in some modern Tupí–Guaraní languages, which only make use of inactive markers together with a special set of coreferential subject markers (see Jensen, 1998: §6.3; Rose 2009: §3.1). What matters for the present discussion is that, in Mbyá as in other Tupí–Guaraní languages where this construction is still attested, converbs only cross-reference their absolutive argument, i.e., either their intransitive subject or their object. We find no contradiction between Dooley (1991) and Damaso Vieira and Baranger (2021) in this respect. |

| 9 | Absolutive cross-reference marking was also documented in Old Guaraní. Indeed, (de Montoya, 1724, Suplemento, ch. 3) describes “another way to conjugate verbs” when the root is followed by the particle ni or its allomorph mi. Montoya’s description makes it clear that only absolutive arguments are cross-referenced in this construction. |

| 10 | We will focus on person features, which are the most relevant for our account, and only discussion number feature when relevant. |

| 11 | Reflexive and reciprocal predication is realized through valency reduction prefixes in Mbyá. Therefore, if the subject of a transitive verb is 1st or 2nd person, its object will never have the same person specification. |

| 12 | Note that this is different from the situation where agreement itself is mediated by case (cf. Bobaljik, 2008). In Mbyá, Infl can agree with accusative DPs, but the person feature copied from an accusative DP will not be spelled out as agreement prefixes. |

| 13 | Third person agreement prefixes and pronouns are unmarked for number. Recall that [1] stands for [SPK, PRT, PER], [2] for [PRT, PER] and [3] for [PER]. |

| 14 | In order to keep glosses light, we do not represent the null object marker in glossed examples. |

| 15 | Remember that ‘[3]’ is short for ‘[person].’ In this example, little vTR only probes for [person], which is copied onto the probe following establishment of an agreement relation with the 2nd person object, hence the notation ‘vTR,[3]’. |

| 16 | An anonymous reviewer asked what the consequences are of stacking voice heads. We believe that they are innocuous, but this is because we have adopted a broad definition of Voice. As we observed in Section 4.3, we analyze all valency increasing and decreasing heads as Voice heads. That is to say, we extend to the category of Voice to functional heads that pertains to grammatical voice in general. Our notion of grammatical voice aligns with Zúñinga and Kittilä (2019), who observe that “the grammatical voice category covers a wide range of phenomena, including causatives, applicatives, passives, antipassives, middles, and others.” Having thus defined Voice, we observe that allowing recursion of Voice heads follows from the simple fact that recursion of valency increasing/decreasing prefixes is overtly attested in Mbyá (see Vieira, 2018). One could of course restrict the category of Voice to active and passive voice heads, along the lines of Kratzer (1996) and much subsequent literature. This would exclude other forms of valency increasing or decreasing, for which we would use some label other than Voice. But since we are subtyping our voice heads (i.e., we distinguish the plain active Voice, from the causative VoiceCAUS, from the comitative VoiceCOM, etc.), it seems that the debate about whether we should apply the label Voice to all these heads is merely terminological. Ultimately, we decided to use the label “Voice” in a way that reflects a broad understanding of grammatical voice that goes beyond passive/active diathesis. |

References

- Béjar, S., & Rezac, M. (2009). Cyclic agree. Linguistic Inquiry, 40, 35–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobaljik, J. D. (2008). Where’s Phi? Agreement as a post-syntactic operation. In D. Harbour, D. Adger, & S. Béjar (Eds.), Phi theory: Phi-features across interfaces and modules (pp. 295–328). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Comrie, B. (1976). Review of G.A. Klimov’s outline of a general theory of ergativity [Ocerk obscej teorii ergativnosti]. Lingua, 38, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaso Vieira, M., & Baranger, E. (2021). Object sharing in Mbya Guarani: A case of asymmetrical verbal serialization? Languages, 6(1), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, A. R. (2021). Interaction, satisfaction, and the PCC. Linguistic Inquiry, 55(1), 39–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Montoya, R. (1724). Arte de la lengua Guaraní, por el P. A. Ruiz de Montoya S. J. Con los Escolios, Anotacionesy Apéndices del P. Paulo Restivo. Santa María la Mayor. Available online: http://www.etnolinguistica.org/biblio:montoya-1724-arte (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Dooley, R. (1991). A double verb construction in Mbyá Guaraní. Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, University of North Dakota Session, 35, 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, R. (2015). Léxico Guarani, dialeto Mbyá: Introdução. Associação Internacional de Linguística—SIL Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, W. (2025). Verb-initial clauses in Kawahíva. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 43, 563–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estigarribia, B. (2020). A grammar of paraguayan guarani. UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume, A., & Rose, F. (2010). Sociative causative markers in South American languages: A possible areal feature. In F. Franck (Ed.), Essais de typologie et de linguistique générale: Mélanges offerts à Denis Creissels (pp. 383–402). ENS Éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale, & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20 (pp. 111–176). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, H. (2017). The ‘bundling’ hypothesis and the disparate functions of little v. In R. D’Alessandro, I. Franco, & A. Gallego (Eds.), The verbal domain (pp. 3–28). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, H., & Ritter, E. (2002). Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language, 78, 482–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haspelmath, M. (1995). The converb as a cross-linguistically valid category. In M. Haspelmath, & E. König (Eds.), Converbs in cross-linguistic perspective: Structure and meaning of adverbial verb forms—Adverbial participles, gerunds (pp. 1–56). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C. (1987). Object prefix incorporation in Proto-Tupí-Guaraní verbs. Language Sciences, 9, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C. (1990). Cross-referencing changes in some Tupí-Guaraní languages. In D. Payne (Ed.), Amazonian linguistics, studies in lowland South American languages (pp. 117–158). University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C. (1998). Comparative Tupí-Guaraní Morpho-syntax. In D. Derbyshire, & G. Pullum (Eds.), Handbook of Amazonian languages (pp. 490–603). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer, A. (1996). Severing the external argument from its verb. In J. Rooryck, & L. Zaring (Eds.), Phrase structure and the lexicon (pp. 109–137). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legate, J. (2008). Morphological and abstract case. Linguistic Inquiry, 39(1), 55–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, Y. (1987, August 3–28). Referential hierarchy and Tapirape split marking systems. Working Conference on Amazonian Languages, Eugene, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Marantz, A. (2013). Verbal argument structure: Events and participants. Lingua, 130, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M. F. (2004). Descrição e análise de aspectos da gramática do Guarani Mbyá [Ph.D. thesis, UNICAMP]. [Google Scholar]

- Mithun, M. (1991). Active/agentive case marking and its motivations. Language, 67(3), 510–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, D. (1994). The Tupí-Guaraní inverse. In P. Hopper, & B. Fox (Eds.), Voice: Form and function (pp. 313–340). Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Preminger, O. (2015). Agreement and its failures. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Preminger, O. (2019). The PCC, the no-null-agreement generalization, and clitic doubling as long head movement. Talk Presented at CASTL, University of Tromsø. [Google Scholar]

- Pylkkänen, L. (2008). Introducing arguments. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rapold, C. (2007). Defining converbs ten years on—A hitchhiker’s guide. In S. Völlmin, A. Amha, C. J. Rapold, & S. Zaugg-Coretti (Eds.), Converbs, medial verbs, clause chaining and related issues. Rüdiger Köppe Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, E., & Wiltschko, M. (2014). The composition of INFL: An exploration of tense, tenseless languages, and tenseless constructions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 32(4), 1331–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A. D. (1953). Morfologia do verbo Tupi. Letras, 1, 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, F. (2009). The origin of Serialization: The case of Emerillon. Studies in Language, 33(3), 644–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, F. (2015). When “you” and “I” mess around with the hierarchy: A comparative study of Tupi-Guarani hierarchical indexation systems. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi: Ciências Humanas, 10(2), 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, F. (2018). Are the Tupi-Guarani hierarchical indexing systems really motivated by the person hierarchy. Typological Hierarchies in Synchrony and Diachrony, 121, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Seki, L. (2000). Gramática do Kamaiurá. Editora da Unicamp. [Google Scholar]

- Shibatani, M., & Pardeshi, P. (2002). The causative continuum. In M. Shibatani (Ed.), The grammar of Causation and interpersonal manipulation (pp. 85–126). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Svenonius, P. (2012). Spanning [Master’s thesis, University of Tromsø]. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Castillo, M. (1991). The semantics of Guaraní agreement markers. In Proceedings of the annual meeting of the berkeley linguistics society (Vol. 17, pp. 324–335). Linguistic Society of America. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Castillo, M. (2002). Guaraní causative constructions. In M. Shibatani (Ed.), The grammar of causation and interpersonal manipulation (Vol. 48, pp. 507–534). Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Castillo, M. (2004). Serial verb constructions in Paraguayan Guarani. International Journal of American Linguistics, 70, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Castillo, M. (2007). Voice and transitivity in Guaraní. In M. Donohue, & S. Wichmann (Eds.), The typology of semantic alignment systems (pp. 380–395). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, M. M. D. (2018). Recursion in tupi-guarani languages: The cases of tupinambá and guarani. In L. Amaral, M. Maia, A. Nevins, & T. Roeper (Eds.), Recursion across Domains (pp. 166–184). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zubizarreta, M. L., & Pancheva, R. (2017). A formal characterization of person-based alignment: The case of Paraguayan Guaraní. Natural Language and Linguistics Theory, 35, 1161–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñinga, F., & Kittilä, S. (2019). Grammatical voice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).