Abstract

This paper investigates the morphosyntactic and semanto-pragmatic behavior of the German neo-pronoun xier, a gender-neutral form used to refer to nonbinary individuals. Framed within the Minimalist Program, the analysis explores how xier carries a gender feature that encodes nonbinary identity—not through binary morphological marking, but via presupposition. The use of xier triggers a presupposition about the referent’s identity: that they are nonbinary. This gender feature is not absent, void or underspecified, but interpretively rich and categorically distinct. The analysis thus rejects any account treating xier as lacking gender. Instead, it argues that xier exemplifies a grammatical strategy of encoding gender beyond the binary, through formal structures that engage the interpretive system directly. The paper further argues that xier’s morphosyntactic profile—including its compatibility with standard agreement morphology—shows that nonbinary gender can be syntactically represented and participate fully in φ-feature interactions. Drawing on cross-linguistic comparisons (e.g., English they and the Italian adaptation ze), the study shows how presuppositional gender encoding supports stable φ-Agree, interface-compatible labeling without requiring binary valuation. The proposal refines the architecture of φ-features by allowing for interpretively active gender categories that are formally encoded even when they do not match traditional binary specifications. This account offers a model for how minimalist syntax can accommodate socially driven innovations without abandoning core theoretical principles. Xier, in this light, demonstrates that grammatical systems can expand to encode emerging reference categories—not by omitting gender, but by formally encoding nonbinary gender via presupposition. This study is the first to offer a formal syntactic account of a German neo-pronoun, linking socially driven innovation to core φ-feature operations like Agree and valuation.

Keywords:

neo-pronouns; German; nonbinary language; presupposition; minimalist syntax; agree; phi-features 1. Introduction

The emergence of gender-neutral and nonbinary pronouns poses both a theoretically fruitful and empirically pressing challenge for formal syntax. Examples include English singular they in (1) and the German xier [ksiːɐ] in (2):

| (1) | They have bought a new car. | ||||

| (2) | Xier | hat | ein | neues | Auto |

| xier-nom.sg | aux.ind.prs.3sg | indef.acc.sg.n | new-acc.sg.n | car | |

| gekauft. | |||||

| ptcp-buy-ptcp | |||||

| ‘That person has/they have bought a new car.’ | |||||

While they has been the focus of extensive investigation from sociolinguistic, formal morphosyntactic and diachronic perspectives (see, among many others, Bodine, 1975; Baranowski, 2002; Balhorn, 2004; LaScotte, 2016; Bjorkman, 2017; Conrod, 2018, 2019; Ackerman, 2019; Konnelly & Cowper, 2020), xier has received comparatively little attention (e.g., Scheibl, 2023; Cassaris, 2025). This relative neglect is largely due to its limited entrenchment in actual language use.

From a formal standpoint, such elements typically challenge canonical φ-feature specifications and raise fundamental questions about the architecture of agreement, the interpretive role of pronouns and the adaptability of syntactic theory in light of socially driven linguistic innovation. In (1), they is formally ambiguous between a third-person plural and a gender-indefinite third-person singular pronoun. The latter use—attested since the 14th century in reference to non-specific, quantified individuals—has more recently been extended to refer to individuals whose gender identity does not conform to binary categories (Balhorn, 2004, p. 91; Konnelly & Cowper, 2020, p. 1). Notably, in English (as in other Germanic languages including German), plural pronominal morphology does not encode grammatical gender.

In contrast, xier in (2) is a so-called “neo-pronoun” that has emerged within queer and LGBTQI+ communities to explicitly denote individuals who identify outside the traditional male/female gender binary. More broadly, neo-pronouns are newly introduced or recently adopted personal pronouns crafted to represent gender identities beyond the conventional categories, often arising from marginalized groups seeking inclusive and precise linguistic self-expression. To clarify the distinction between the examples above, we note the following: while (1) supports both a singular, nonbinary reading (3a) and a canonically plural reading (3b), among other interpretations, (2) is restricted solely to the interpretation in (3a).

| (3) | a. | ∃e[buy(e) ∧ Agent(e,x) ∧ ∃y[car(y) ∧ new(y) ∧ Theme(e,y)] ∧ Perfect(e)] ∧ Human(x) ∧ Atomic(x) ∧ ¬Male(x) ∧ ¬Female(x) |

| ‘There is (or was) a completed event of buying in which some human individual (who is neither male nor female)1 bought a new car.’ | ||

| b. | ∃P [Plural(P) ∧ Human(P) ∧ ∃e [buy(e) ∧ Agent(e, P) ∧ ∃x [car(x) ∧ new(x) ∧ Theme(e, x)] ∧ Perfect(e)]] | |

| ‘There is (or was) a completed event of buying in which some group of humans bought a new car.’ |

Xier is productively used in academic and various linguistically and socially inclusive contexts, as illustrated by the attestation in (4)—an excerpt from an event announcement for a talk by Anna Heger, published on the official website of the University of Göttingen:

| (4) | Anna Heger arbeitet seit 2009 an alternativer Grammatik und zeichnet politische und biographische Comics. […] Xier selber ist feministisch, nonbinary queer, bi, weiß, Ossikind und studiert. |

| ‘Anna Heger has been working on alternative grammar since 2009 and draws political and biographical comics. […] They themselves are feminist, nonbinary queer, bi, white, a child of East Germany and a student.’ | |

| (https://uni-goettingen.de/en/541689.html accessed on 25 August 2025) |

In (5), an academic discourse-studies paper discussing, among other topics, the work of Karen Barad—a scholar frequently referred to using linguistically nonbinary language—xier appears alongside other nonbinary strategies. For example, the colon in Mitbegründer:in (‘co-founder’) functions as an inclusive morphological strategy realized through a typographical device. Here, the originally verbal particle mit- corresponds to the prefix co- in English, -begründ- is the verb stem, -er- is the default masculine agentive suffix and -in marks the feminine form. The colon signals gender inclusivity and is accompanied by phonetic correlates, such as a glottal stop at its position, enabling reference to individuals of any gender, including those who do not identify within the binary domain. At the same time, xier co-occurs with traditionally gendered elements like the feminine-marked relative pronoun die (‘who’) and the indefinite article eine (‘a’), which results in somewhat ambiguous or conflicting interpretations of referential gender identity:

| (5) | 16 Jahre später knüpft Karen Barad, die als eine Mitbegründer:in des New Materialism gilt, […]. Mit dem Agentiellen Realismus konzeptualisiert Barad Diskurse und Materie als verschränkte Praktiken. Xier fokussiert dabei die Intra-Aktionen materiell-diskursiver Praktiken, die …. |

| ‘Sixteen years later, Karen Barad—considered one of the co-founders of New Materialism—builds on this work […]. With agential realism, Barad conceptualizes discourse and matter as entangled practices. They focus on the intra-actions of materially-discursive practices that….’ | |

| (B. Kleiner and C. Kretzschmar (2021): Diskurs, Materie und Materialisierung bei Judith Butler und Karen Barad (scientific paper)) |

Two closely intertwined factors are especially important: first, the emergence of xier stems from socially driven language change rather than gradual language-internal evolution; second, xier was introduced abruptly into German and unlike English singular they, it had no prior existence as a lexical item in the language.

The issue becomes particularly salient within the framework of the Minimalist Program (Chomsky, 1995 and much subsequent work), which aims to account for linguistic competence through maximally constrained principles and minimal representational apparatus. Within this framework, the behavior of pronouns is primarily governed by their participation in core syntactic operations—Agree, Merge, and Labeling—and by the structure of their internal φ-feature composition, traditionally comprising [Person], [Number] and [Gender].

The emergence of nonbinary pronouns like xier, however, invites a re-examination of these assumptions. While forms like xier pattern distributionally with canonical third-person singular pronouns, they diverge in feature composition: they bear [Person: 3] and [Number: Sg], but its gender feature diverges from the conventional binary model in important ways. This situation raises several crucial theoretical questions:

- Are all three φ-features obligatorily required for successful Agree when one (here: [Gender]) deviates from canonical specification? If so, should such non-canonical gender features be analyzed as a form of underspecification tied to feature completeness or must they be treated as distinct, formally specified values within the feature system?

- Can Labeling proceed when feature sharing involves non-canonical or nonbinary gender specifications rather than the expected binary values?

- What interpretive effects arise when the gender feature is morphosyntactically specified but diverges from the binary paradigm in pronominal DPs?

- Crucially, does the presence of pronouns like xier suggest that syntactic models may overemphasize canonical feature configurations, calling for a broader or more flexible conception of feature completeness that accommodates nonbinary values?

This paper offers a feature-driven minimalist analysis of xier, arguing that it instantiates a pronominal expression bearing a systematically non-canonical, but formally specified [Gender] value. This distinct feature is neither absent nor underspecified in the traditional sense, but diverges from binary norms in its formal and interpretive properties. I contend that this configuration yields multiple syntactic and semantic consequences:

- (i)

- Variation in agreement morphology arising from interaction with nonstandard or contextually valued gender features;

- (ii)

- Potential extensions to the Agree operation to accommodate goals bearing formally distinct, yet interpretable, gender specifications;

- (iii)

- Implications for the Labeling Algorithm, given its reliance on canonical φ-feature congruence and the presence of formally novel feature values;

- (iv)

- A departure from traditional gender-indexed presuppositions, resulting in semantic flexibility that aligns with the social motivations underpinning forms like xier.

This analysis addresses broader theoretical issues specifically regarding xier. Its well-formedness, despite diverging from canonical binary gender values, suggests that for xier, [Gender] remains an obligatory and interpretable feature. However, in xier, the specification of this feature transcends traditional binary categories, inviting a reconceptualization of gender as a flexible, context-dependent dimension within the syntactic feature system (at least in the contexts in which it is productively used). Under Distributed Morphology (hencefort: DM; Halle & Marantz, 1993; Embick & Noyer, 2007), where Vocabulary Insertion is conditioned by syntactic feature bundles, xier challenges existing frameworks by necessitating formal encoding of nonbinary gender values while maintaining morphosyntactic coherence.

By addressing these issues, this paper seeks, on the one hand, to offer an initial step toward filling a gap in the research literature concerning the syntax and feature composition of xier; on the other hand, it aims to contribute to two interrelated domains of theoretical inquiry. First, it proposes a more flexible model of φ-feature architecture within the DP—one that accommodates non-canonical feature specifications while preserving full syntactic functionality. Second, it explores how minimalist syntax might account for sociolinguistically motivated innovation without appealing to stipulative or theory-external mechanisms. Pronouns like xier offer a productive testing ground for evaluating the robustness and adaptability of syntactic theory in the face of natural language variation and change.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews canonical φ-feature specification in German third-person singular pronouns, establishing a baseline for the analysis of xier. Section 3 proposes a formal feature structure for xier, emphasizing the implications of its non-canonical gender specification. Section 4 offers a brief, illustrative comparison between xier and English singular they, building on the theoretical insights developed in Section 3. Section 5 concludes.

2. Canonical Pronouns and φ-Feature Specification

2.1. Pronouns and φ-Features

Within the Minimalist Program (Chomsky, 1995), pronouns are standardly analyzed as D-heads bearing interpretable φ-features, which mediate morphosyntactic agreement and valuation operations. In German, third-person singular pronouns—er (masculine, ‘he’), sie (feminine, ‘she’) and es (neuter, ‘it’)—instantiate fully specified φ-feature bundles, serving as canonical targets for φ-Agree. These forms establish a baseline for probing the structural and interpretive properties of non-canonical pronouns such as xier, whose feature composition departs from traditional gender-marking paradigms.

Let us begin by outlining the feature composition of canonical third-person singular pronouns. Gender features belong to the class of what is commonly referred to as φ-features, a set that typically includes [Person] and [Number], in addition to [Gender]. These features are distinguished from others, such as [Case], by their semantic content: φ-features contribute directly to interpretation, whereas [Case] functions as a formal licensing requirement with no inherent interpretive value. Accordingly, in the structural representation in (6), the latter is represented as distinct from the φ-feature bundle:

| (6) | a. | er → [D [Case: Nom] [φ: [Person: 3, Number: sg, Gender: masc]]] |

| b. | sie → [D [Case: Nom] [φ: [Person: 3, Number: sg, Gender: fem]]] | |

| c. | es → [D [Case: Nom] [φ: [Person: 3, Number: sg, Gender: neut]]] |

It is important to distinguish here between formal φ-features and semantic (natural) gender features. The [+masc] value in (6a) is a formal specification in the morphosyntactic agreement system: it is part of the lexical entry for er ‘he’ and interacts with agreement probes in the syntax. In minimalist terms, “interpretable” means that the feature is legible at LF, not that it necessarily encodes a natural-gender property of the referent. In German, formal gender features may—but need not—align with natural gender. For instance, in (7), the pronoun er is formally [+masc] but refers to an inanimate noun whose grammatical gender is masculine, without any implication of male biological sex:

| (7) | Maria | ging | zum | Tischi. | Eri | |||

| Maria | go-ind.pst.3sg | to-def.dat.sg.m | table | he-nom.sg | ||||

| stand | in | der | Ecke. | |||||

| stand-ind.pst.3sg | in | def.dat.sg.f | corner | |||||

| ‘Maria went to the table. It was standing in the corner.’ | ||||||||

This shows that the presence of [+masc] on er is a property of the grammar’s feature system rather than a semantic entailment of “male”. The same holds for [+fem] features on sie ‘she’ when used with inanimates.

The use of the canonical pronouns referring to overtly sexed (masculine or feminine) human individuals is exemplified in (8) (for the neuter, see the discussion in Section 3.2 below). Note that in (8a) and (8b), the masculine and feminine references, as well as the corresponding grammaticality judgments, are based solely on conventional name-based presuppositions rather than any explicitly provided contextual or referential cues:

| (8) | a. | Hansi | wird | nicht | kommen. | Eri/*siei | ||

| Hans | aux.ind.prs.3sg | neg | come-inf | he-nom.sg/she-nom.sg | ||||

| ist | zu | müde. | ||||||

| be-ind.prs.3sg | too | tired | ||||||

| ‘Hans is not coming. He is too tired.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Mariai | wird | nicht | kommen. | Siei/*eri | |||

| Hans | aux.ind.prs.3sg | neg | come-inf | she-nom.sg/he-nom.sg | ||||

| ist | zu | müde. | ||||||

| be-ind.prs.3sg | too | tired | ||||||

| ‘Maria is not coming. She is too tired.’ | ||||||||

Φ-features are instantiated on the D head, which projects into a nominal expression that may, depending on syntactic context, be embedded within a KP layer (cf. Bittner & Hale, 1996; Cardinaletti & Starke, 1999). The φ-features are crucial in regulating the interaction between DPs and functional heads through the operation Agree and they facilitate labeling, case assignment and interpretation at the C-I and SM interfaces.

2.2. How Does Agree Work in German?

Agree, one of the core operations in the Minimalist framework, is responsible for establishing syntactic dependencies by “relating sets of features in the syntactic component” (Levin, 2015, p. 29). These feature relations determine the structural hierarchies that underlie clause structure.

The standard definition of Agree (cf. Chomsky, 1995, 2000, 2001; Zeijlstra, 2012) is as follows (but see below for further discussion):

| (9) | Let α and β be syntactic objects in a derivational workspace. α enters into an Agree relation with β iff the following conditions are met: | ||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| a. | γ bears a matching [iF], | ||

| b. | γ is closer to α than β is (i.e., γ is c-commanded by α and asymmetrically c-commands β). | ||

From a morphosyntactic perspective, canonical third-person personal pronouns serve as optimal goals in an Agree relation, which is initiated when a functional head—e.g., T—bears unvalued φ-features. The pronoun, carrying a full set of valued φ-features, satisfies the probe’s requirements by triggering valuation for features such as [Person], [Number] and [Gender].2 In return, it receives abstract Case—typically nominative in subject position—as a reflex of the successful syntactic dependency.

In head-initial TP languages, Agree is typically assumed to proceed downward, with the T head acting as a probe that searches for a goal within its c-command domain.

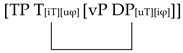

| (10) |  |

In the representation in (10), T is clearly positioned above the vP-internal DP, as is uncontroversially assumed for SVO languages such as English.

The syntactic architecture of German, however, has been the subject of extensive debate over the past few decades, with a range of competing proposals. Some analyses posit that German projects a TP with the vP shell linearized to its right, thereby producing an underlying SVO configuration in line with the universal base order proposed within the antisymmetric framework of Kayne (1994):

| (11) | [TP T [vP DP V]] |

Others even reject the presence of TP in German altogether, proposing instead that CP directly selects vP as its complement—a view defended, e.g., by Haider (2010):

| (12) | [CP C [vP DP V]] |

In the present analysis, I adopt a more traditional approach, assuming that TP is present and head-final in German, as shown in (13):

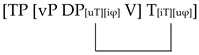

| (13) | [TP [vP DP V] T] |

This structural choice has direct implications for the operation of Agree: since T is merged higher and to the right, it does not c-command its potential goals within vP in the relevant configuration. As a result, the standard mechanism of downward Agree cannot apply straightforwardly. This configuration therefore necessitates upward Agree, whereby the goal probes upward to value features on a higher head (viz., the probe is c-commanded by the goal)—a mechanism that has been independently proposed in a number of empirical domains (see Zeijlstra, 2012; Wurmbrand, 2014; Winchester, 2019, among others). To be sure, there is by no means a consensus in the literature as to whether such a mechanism is universally available, or, if it is, how exactly it operates in natural language syntax (cf. the informative overview in Diercks et al., 2020).3 If a configuration like (13) indeed requires upward probing, then the relevant structural representation would correspond to (14a) and more specifically to (14b):

| (14) | a. | [XP Goal[iF] [YP Probe[uF]]] |

| b. |  |

Abstracting away from the finer details of the analysis, I take the very existence of parametric variation between languages with head-initial vs. head-final TP to suggest that the directionality of Agree—upward vs. downward—can itself be a reflex of deeper configurational settings. If this is on the right track, then we are dealing with a paradigmatic case of parametric variation: structural asymmetries correlate with distinct mechanisms of syntactic dependency. This, in turn, lends further support to differentiated approaches to syntactic dependency formation, as proposed, e.g., by Koopman (2006), Béjar and Řezáč (2009), Baker (2008), Putnam and van Koppen (2011), and Carstens (2016) and Himmelreich (2017).

This bidirectional feature valuation is crucial for morphosyntactic convergence. It governs subject–verb agreement, determines verbal morphology (cf., e.g., er schläft/*schlafen, he-nom sleep-ind.prs.3sg/*sleep-ind.prs.3pl, ‘he sleeps’) and preserves φ-feature consistency across syntactic domains. Such dependencies are necessary for achieving derivational success under Minimal Search, which requires that derivations satisfy interface conditions using the least costly, most local operations available. This principle encapsulates a key development within generative approaches: the insight that locality constraints—such as Relativized Minimality (Rizzi, 1990), Strict Cyclicity (Chomsky, 2007, p. 5) and related mechanisms—are foundational to the architecture of syntactic computation.

2.3. Canonical Pronouns, Presuppositions and Paradigms

At the interface level, φ-features—and, in particular, [Gender]—encode significant presuppositional content, as illustrated in (8) above. Previous work (Cooper, 1979; Heim & Kratzer, 1998; Sauerland, 2008) has demonstrated that gender-marked pronouns introduce gender-indexed presuppositions that must be satisfied by contextual information. Consider the following examples, which involve human referents:

| (15) | a. | Sie | hat | angerufen. |

| she-nom.sg | aux.ind.prs.3sg | v.prt.ptcp-call-ptcp | ||

| ‘She called.’ | ||||

| → presupposes [+feminine] referent | ||||

| b. | Er | ist | gegangen. | |

| he-nom.sg | aux.ind.prs.3sg | ptcp-go-ptcp | ||

| ‘He left.’ | ||||

| → presupposes [+masculine] referent | ||||

When canonical pronouns refer to human individuals, their grammatical gender features often correlate with presuppositions about the referent’s natural gender (e.g., er → male, sie → female). However, this correlation does not hold in all uses: the same pronouns can occur with inanimate antecedents solely by virtue of grammatical gender agreement, as in (7) above. In such inanimate uses, the φ-feature [gender] remains formally specified and syntactically active but does not introduce natural-gender presuppositions. This distinction between formal feature specification and semantic gender content is crucial for understanding how nonbinary pronouns like xier fit into the system, since their interpretable gender feature is inherently referential and identity-linked rather than grammatically arbitrary.

In spontaneous speech, the assignment of masculine or feminine gender in cases like (15) often arises from one of two sources: either (i) from the speaker’s individual assumptions or conceptualizations of the referent’s gender identity or (ii) from contextually grounded knowledge of the referent’s self-identified gender. In this sense, gender specification may be the result of speaker-based inference or context-sensitive reference resolution—both of which feed into the satisfaction of presuppositional requirements at the discourse level. If the referent of the pronoun fails to satisfy such presuppositions—e.g., if sie (‘sie’) refers to an individual who is, or is known to identify as, male—the utterance becomes pragmatically infelicitous. This makes canonical pronouns semantically rich, in the sense that they condition felicity on backgrounded contextual entailments.

This interface effect is tightly correlated with the syntax. The feature [gender] is not merely a PF phenomenon: it is interpretable and projects into LF, contributing to the propositional content. This justifies the traditional view that φ-features on pronouns are syntactically and semantically relevant. In this light, sie does not simply happen to surface as feminine—it encodes femininity as a formal interpretive feature.

Canonical pronouns also aid in disambiguating anaphoric dependencies. In embedded CPs or contextually dense structures, gender-marked pronouns restrict the set of accessible antecedents. Consider the following (16):

| (16) | Als | Annax | Mariay | umarmte, | lächelte | siex/y. |

| when | Anna | Maria | hug-ind.pst.3sg | smile-ind.pst.3sg | she-nom.sg | |

| ‘When Anna hugged Maria, she smiled.’ | ||||||

Here, the pronoun sie restricts the potential antecedents to Anna or Maria, with both referents being possible and the choice often influenced by speaker preference. Resolution depends on factors such as salience and discourse prominence. Thus, φ-features serve not only as morphosyntactic and semantic cues but also as pragmatic filters shaping referential accessibility within complex discourse contexts.

Regarding their paradigms, canonical German pronouns realize fully specified feature bundles encoding both φ- and case features, partly through syncretism. These features are structurally integrated in German, such that φ-features are systematically associated with case morphology. (17) illustrates the paradigm of canonical third-person pronouns:

| (17) | Case | Gender | ||

| Masc | Fem | Neut | ||

| Nom: | er | sie | es | |

| Acc: | ihn | sie | es | |

| Dat: | ihm | ihr | ihm | |

| Gen: | seiner | ihrer | seiner | |

In addition to their role in φ-agreement, canonical pronouns contribute to labeling under Chomsky’s (Chomsky, 2013, 2015) Labeling Algorithm, a mechanism whereby syntactic objects are assigned labels at the interfaces based on feature-sharing or movement asymmetries. In standard subject-T configurations, T labels the projection via φ-Agree with the subject. When the subject bears a complete φ-feature bundle (crucially, including [Gender]), this configuration yields a stable label. Thus, φ-completeness plays a direct role in derivational convergence, as successful label formation at the phase level hinges on the availability of a fully specified φ-set.

In technical terms, the completeness of the φ-set also interacts with the Activity Condition (Chomsky, 2000), according to which only syntactic objects with unvalued features (e.g., uCase) remain active for further operations. Canonical pronouns like sie in (16) above are active at the relevant point in the derivation because they require Case valuation, and they are sufficiently specified to satisfy φ-probes introduced by functional heads such as T.

This tightly integrated constellation of morphological form, syntactic properties, semantic content and pragmatic function constitutes the formal baseline against which underspecified or innovative forms like neo-pronouns must be evaluated. As the next sections will show, a form like xier, distinguished by its presuppositionally encoded [Gender] feature that differs from traditional binary specifications, may nevertheless enter into Agree relations, support labeling and contribute to discourse reference. Whether this capacity arises from native syntactic mechanisms or is facilitated by compensatory processes at the PF or interpretive levels is the focus of the next section.

3. The Morphosyntax and Referential Properties of xier

Having established the featural and syntactic behavior of canonical third-person pro-nouns in German, we now turn to the neo-pronoun xier. This section investigates its morphosyntactic representation and derivational behavior, with a particular focus on its φ-feature specification, agreement behavior and interaction with the derivational architecture of the Minimalist Program.

Xier exhibits a fully fledged paradigm in the singular,4 as shown in (18), and has a corresponding possessive pronoun xies [ksiːz] and a form, dier [diːɐ], functioning as a definite article and a relative pronoun (19):

| (18) | Nominative | Genitive | Dative | Accusative | ||||||||

| xier | xieser | xiem | xien | |||||||||

| (Cassaris, 2025, p. 204; based on Heger, 2021) | ||||||||||||

| (19) | a. | Xier | will | verreisen. | ||||||||

| xier-nom.sg | want-ind.prs.3sg | travel-inf | ||||||||||

| ‘That person wants/they want to travel.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | Xier | packt | xiesen | Koffer. | ||||||||

| xier-nom.sg | pack-ind.prs.3sg | xies-acc.sg.m | suitcase | |||||||||

| ‘That person is/they are packing their suicase.’ | ||||||||||||

| c. | Diem | Nachbar_in, | dien | wir | vorhin | |||||||

| def.dat.sg | neighbor | rel.acc.sg | we-nom.sg | earlier | ||||||||

| trafen, | bringe | ich | Post. | |||||||||

| meet-ind.pst.1pl | bring-ind.prs.1sg | I-nom | post | |||||||||

| ‘I’m bringing mail to the neighbor we met earlier.’ | ||||||||||||

| (all examples from Heger, 2021, translations and glosses mine) | ||||||||||||

In (19a), xier functions as the subject of the sentence, as already illustrated in the examples in (4) and (5) in Section 1. In (19b), the same form occurs along with its corresponding possessive. As with the canonical pronouns, the possessive is derived from the genitive form of the pronoun and realized with inflectional morphology—here marking the accusative singular masculine, due to the inherent masculine gender of Koffer ‘suitcase’. In (19c), the definite article accompanying Nachbar_in—a gender-neutral orthographic form of the noun ‘neighbor’, which would otherwise appear with either a zero allomorph for the masculine or the overt derivational suffix -in for the feminine—is inflected for dative, since diem Nachbar_in serves as the indirect object of the clause. The relative pronoun, by contrast, surfaces with accusative morphology, as it functions as the direct object within the relative clause.

With respect to the issue at hand, xier differs from typical pronouns not only in form but also in feature composition. Although it consistently carries [Person: 3] and [Number: Sg], its status regarding [Gender] is less straightforward. To illustrate this, we begin with a provisional representation that treats xier as lacking a morphosyntactically valued [Gender] feature, which will be examined and refined through the examples that follow:

| (20) | xier → [D [φ: [Person: 3, Number: Sg, Gender: ∅]]] |

Here, [Gender: ∅] reflects a view in which xier enters the derivation without a morphosyntically valued gender feature. This depiction captures an initial intuition often associated with gender-neutral forms: that they lack specification where binary pronouns (e.g., er, sie) show overt gender agreement. This is not the analysis adopted in this paper. The purpose of (20) is heuristic: to represent a common structural assumption that will be rejected and replaced below.

3.1. Feature Pseudo-Deficiency and Licensing

If taken seriously, this representation would classify xier as having a partial φ-set—complete in [Person] and [Number], but incomplete in [Gender]. Such an object might be treated, following Roberts (2010), as some sort of a defective goal: one unable to satisfy a probing head’s full feature requirements and thus prone to incorporation, movement, or morphological reduction (e.g., cliticization).

Empirically, however, xier does not behave like a defective or deficient pronoun. It surfaces in canonical argument positions, interacts with functional projections and participates in agreement chains without exhibiting instability or reduction. The partial φ-feature account fails to predict this behavior. Moreover, if xier genuinely lacked a gender feature, it should pattern like expletives or syntactic defaults—yet it clearly contributes referential content and constrains discourse felicity in ways that are not available to pronouns like es ‘it’. These facts suggest that the depiction in (20), while formally coherent, is descriptively inadequate.

This inadequacy becomes particularly clear in three core syntactic domains:

- Agree: Functional heads like T probe for full φ-feature sets. Under the provisional view, T would find [person] and [number], but no [gender] on xier. One might expect agreement failure, default morphology or structural repair. Xier, however, regularly triggers agreement in naturalistic usage and functions unproblematically in finite contexts.

- Labeling: In the Chomskyan model (2013, 2015), shared φ-features are often required for label formation (e.g., in TP configurations). A deficient φ-set might predict unstable labeling or dependency on fallback mechanisms (e.g., C-driven labeling or remerger), yet there is no indication that xier induces derivational instability.

- Activity and Case licensing: The Activity Condition requires arguments to bear unvalued features to remain visible for Agree. If xier were fully specified except for [Gender], it should in principle lose activity too early. The fact that it remains case-active and agreement-capable indicates that its feature bundle is sufficient for full syntactic participation.

Taken together, these observations point toward a different conclusion: xier is not (morpho)syntactically incomplete or genderless. Rather, its [Gender] feature takes a non-traditional form—not absent, but differently valued. What might look like underspecification in (20) is more accurately understood as an instance of nonbinary specification that operates through interpretive mechanisms rather than morphology.

3.2. Presuppositional Gender and Interpretive Valuation

Building on the preceding discussion, I propose that xier bears a [Gender] feature that is neither binary nor morphologically overt, but presuppositionally valued. Its use signals that the referent identifies as nonbinary.

The claim that xier encodes a presupposition about the referent’s gender identity can be supported by applying a set of well-established presupposition diagnostics (cf., e.g., the seminal works by Karttunen 1973, 1974, 2016; Karttunen & Peters, 1979; Chierchia & McConnell-Ginet, 1990; Heim & Kratzer, 1998). Table 1 applies six such “classic” tests—by now standard in the literature—to xier. Each diagnostic assesses whether the inference to a nonbinary referent persists under various embeddings, challenges or cancelation attempts. The third column contains translations only, without interlinear glosses, to ensure readability.

Table 1.

Shows the presuppositional behavior of xier.

Table 1 shows that the nonbinary inference systematically projects through negation, questions, conditional clauses and modal contexts and can be explicitly targeted in “Hey, wait a minute!”-type objections. The defeasibility (cancellability) test reveals a familiar asymmetry: although presuppositions can, in principle, be canceled in carefully constructed or metalinguistic contexts, in normal usage, the attempted cancelation of xier’s nonbinary inference sounds contradictory or is perceived as socially marked (in the relevant cell, the symbol “#” indicates that the sentence is pragmatically odd or contradictory in the intended interpretation.).

These results converge on the conclusion that xier’s gender specification behaves like a robust presupposition in the classical sense, while also exhibiting heightened pragmatic resilience due to its socially indexical content—a property that distinguishes it from more easily accommodated or neutralized presuppositions such as binary gender marking in er/sie.

The cancelation behavior of xier warrants closer examination. While its projection properties align with those of canonical presupposition triggers, its resistance to cancelation differs in important ways from some well-known cases in the literature. A comparison with standard existential presuppositions illustrates this difference.

A noteworthy contrast emerges when xier is compared to more familiar presupposition triggers in cancelation contexts. Consider the following (21):

| (21) | a. | Der | König | von | Frankreich | existiert | nicht. | ||

| def.nom.sg.m | king | of | France | exist-ind.prs.3sg | neg | ||||

| ‘The king of France does not exist.’ | |||||||||

| b. | #Xier | ist | binär. | ||||||

| xier | be-ind.prs.3sg | binary | |||||||

| ‘Xier is binary’ | |||||||||

In (21a), the existential presupposition can be explicitly canceled without infelicity (‘The king of France does not exist—in fact, there is no king of France’), as expected for backgrounded content in the classical sense (cf., among many others, (Frege, 1892) for the sense/reference framework; (Strawson, 1950; Karttunen, 1973)). In (21b), by contrast, attempted cancelation (‘Xier is binary—in fact, they are not non-binary’) is typically judged contradictory. As an anonymous reviewer points out, one possible interpretation of this pattern is that the nonbinary specification of xier forms part of its asserted, at-issue content, rather than a presupposition.

However, the projection patterns documented in Table 1 above argue against such a reclassification: the gender specification survives embedding under negation, questions, conditionals, and modals in the same way as canonical presuppositions. The difference in cancellability can therefore not be attributed to a change in the grammatical status of the content, but to the nature of the content itself. Whereas the presupposition in (21a) concerns the mere existence of an individual satisfying a description—allowing for neutral factual correction—the presupposition in (21b) concerns a socially anchored categorization of the referent’s gender identity. In socially salient contexts, attempts to “cancel” such content are not processed as neutral adjustments to the common ground, but as rejections of the referent’s self-identification. This pragmatic enrichment (strengthening) yields the strong contradiction intuition observed in (21b), despite the underlying grammatical profile being presuppositional. This account preserves the analysis of xier as a presupposition trigger in the classical grammatical sense (lexically specified and projecting under embedding) while also capturing its heightened pragmatic resilience, which arises from the interaction between truth-conditional meaning in the formal semantic component and socially indexical meaning. Such cases illustrate the importance of integrating social meaning into models of presupposition, demonstrating that projection behavior and cancelation patterns can diverge when the presupposed content encodes identity-relevant information.

That said, xier’s presuppositional profile is not identical to that of other referential presuppositions: while some can be accommodated or overridden in the immediate discourse (cf., e.g., the gender-switch repair in (22a)), xier exhibits more limited flexibility. In (22a) and (22b), capitalization of a syllable marks corrective focus intonation.

| (22) | a. | A: | (X to a father of a child:) | |||||||||||

| How old is he? | ||||||||||||||

| B: | SHE is three years old. | |||||||||||||

| b. | A: | Alex | ist | wirklich | nett. | Er | ||||||||

| Alex | be-ind.prs.3sg | really | nice | he-nom | ||||||||||

| ist | immer | so | hilfsbereit! | |||||||||||

| be-ind.prs.3sg | always | so | helpful | |||||||||||

| ‘Alex is really nice. He is always so helpful!’ | ||||||||||||||

| B: | XIER | ist | immer | so | hilfsbereit. | |||||||||

| xier | be-ind.prs.3sg | always | so | helpful | ||||||||||

| ‘(Let me correct you:) XIER (not HE) is always so helpful!’ | ||||||||||||||

Switching to xier for a referent previously introduced with er/sie typically signals a change in how the speaker aligns with the referent’s self-identification and abrupt cancelation is often socially marked. In other words, such a “repair” rarely functions as a neutral clarification of facts about the referent; rather, it tends to be interpreted as a socially indexical act, additionally signaling that reference to the individual should henceforth employ xier in accordance with current norms of gender-inclusive usage. This suggests that while xier behaves like other presupposition triggers in projection, it is also embedded in a domain of socially anchored indexical meaning that resists neutral accommodation.

Note that the [Gender] feature discussed in this paper is not semantically neutral or underspecified (as in [Gender: Neut]), but positively interpretable: it contributes presuppositional content that constrains reference and conditions anaphoric accessibility.

This makes xier fundamentally different from canonical er/sie/es in their inanimate uses. In those cases, the [gender] feature is formally specified but semantically vacuous with respect to natural gender. By contrast, xier’s [Gender: Nonbinary] feature is both formally specified—and thus available for agreement—and semantically interpretable in the natural-gender sense: it presupposes that the referent identifies outside the binary male/female categories. In other words, xier’s gender feature is never purely grammatical in the way that the masculine in Tisch (‘table’: masc) or the feminine in Lampe (‘lamp’: fem) is; its felicity conditions are always anchored in the social and identity-related properties of the referent.

This analysis basically shifts the explanatory burden from morphological realization to interpretive mechanisms at the syntax–semantics–pragmatics interface. In this view, xier does not lack gender, but encodes gender differently through pragmatic presupposition rather than canonical morphological opposition. The relevant [Gender] value is part of its lexical specification and projects as a condition on felicitous use.

While the discussion so far has focused on xier’s presuppositional profile, its interaction with German’s grammatical gender system raises further questions about how socially anchored gender features are integrated into agreement. Let us now consider the examples in (23):

| (23) | a. | Sie | hatte | ein | Kind. | Es | |

| she-nom.sg | have-ind.pst.3sg | indef.acc.sg.n | child | it-nom.sg | |||

| hieß | Miriam. | ||||||

| be-called-ind.pst..3sg | Miriam | ||||||

| ‘She had a child. Its name was Miriam.’ | |||||||

| (M. Bach (ed.) (2019), Liebe – Freundschaft – Erwachsenwerden, p. 50) | |||||||

| The pronoun es agrees with the grammatical neuter gender of Kind ([Gender: Neuter]), with no natural-gender inference. | |||||||

| b. | Sie | hatte | ein | Kind. | Sie | ||

| she-nom.sg | have-ind.pst.3sg | indef.acc.sg.n | child | she-nom.sg | |||

| hieß | Miriam. | ||||||

| be-called-ind.pst.3sg | Miriam | ||||||

| ‘She had a child. Her name was Miriam.’ | |||||||

| The pronoun sie reflects semantic agreement with the child’s gender identity (in many cases aligned with, but not restricted to, biological sex—e.g., the referent could be a transgender girl), overriding the grammatical neuter of Kind. | |||||||

| c. | Maria | hatte | ein | Kind. | Xier | |||

| Maria | have-ind.pst.3sg | indef.acc.sg.n | child | xier-nom.sg | ||||

| hieß | Sam. | |||||||

| be-called-ind.pst.3sg | Sam | |||||||

| ‘She had a child. Its[+nonbinary] name was Sam.’ | ||||||||

| The pronoun xier reflects socially indexical agreement: it encodes the nonbinary identity of the referent, overriding the grammatical neuter of Kind. The nonbinary value is not retrieved from the noun’s lexical entry but from discourse knowledge about the referent’s self-identification. | ||||||||

| d. | Julian | wirkt | sehr | sympathisch, | aber | xier | ||||||

| Julian | seem-ind.prs.3sg | very | nice | but | xier-nom.sg | |||||||

| ist | einfach | nicht | das, | was | ||||||||

| be-ind.prs.3sg | simply | neg | that-nom.sg.n | rel.nom.sg.n | ||||||||

| Ru | sucht. | |||||||||||

| Ru | look-for-ind.prs.3sg | |||||||||||

| ‘Julian seems very nice, but they are simply not what Ru is looking for.’ | ||||||||||||

| (amazon.de, user’s review of E. Bloom (2024), Singlebude gesucht - Weihnachtswichtel gefunden (novel)) | ||||||||||||

| Naturally occurring example of xier with a proper name antecedent; agreement value comes from socially anchored information about the referent’s identity. | ||||||||||||

The contrast between (23a)–(23c) shows that German pronouns can reflect three distinct sources of [gender] specification: (i) purely grammatical gender determined by the lexical entry of the antecedent noun (Kind in (23a)); (ii) semantic agreement with the referent’s natural gender (23b); and (iii) socially indexical gender encoding, as with xier in (23c), which presupposes a nonbinary identity. The example in (23d) illustrates the same socially indexical mechanism with a proper name antecedent. Crucially, socially induced gender values are not extra-grammatical annotations; they enter the same φ-feature bundle that controls agreement, but their value assignment takes place at the syntax–semantics–pragmatics interface rather than being fixed in the lexicon. This integration means that introducing new ways to refer to human individuals—such as through xier—directly enriches the inventory of grammatically retrievable gender values, expanding the agreement system beyond the binary paradigm.

From this perspective, purely grammatical gender and socially induced gender are not mutually exclusive categories, but occupy different positions within the same feature-assignment architecture. Grammatical gender values are lexically specified, stable across contexts, and retrieved directly from the stored properties of the noun. Socially induced gender values, by contrast, originate in discourse-level knowledge about the referent’s self-identification, but, once assigned, they behave like any other interpretable φ-feature in the agreement system. In other words, socially indexical gender is “grammaticalized” at the point of feature assignment: it is formally part of the bundle that enters agreement relations, even though its source is pragmatic. The capacity of the grammar to accommodate such values demonstrates that innovations like xier are not merely sociolinguistic overlays, but genuine expansions of the grammatical gender system.

In a sense, xier can be argued to carry more semantically relevant gender information than the canonical, human-referential, grammatically neuter pronoun es. In (23a), as we said, es refers back to ein Kind (‘a child’) and bears neuter grammatical gender, in agreement with its antecedent. Note that the noun Kind is lexically specified as neuter—that is, it is inserted into the Lexicon with an inherent [Gender: Neut] feature, as evidenced by the indefinite article in (23a), which displays the morphological form of an accusative neuter. Semantically, however, es does not encode natural gender; it functions as a referential placeholder for a human referent whose gender is unspecified or backgrounded. In this sense, es is not genderless, but rather carries a semantically uninterpretable gender feature that enables reference without presupposing binary gender membership (in those contexts where es refers to a human individual). This creates a conceptual gap: while es can be used for human referents, it lacks socially meaningful gender information and can thus feel inadequate or impersonal in contexts requiring precise gender reference. By contrast, xier carries an interpretable nonbinary gender feature that actively encodes and indexes the referent’s identity outside the male/female binary, making it semantically richer and socially more informative in human reference contexts.

Indeed, in (23d), xier likewise refers to a human outside the male/female binary, but does so via an interpretable, nonbinary gender feature. Both es and xier permit reference to individuals whose gender is not represented within the er/sie dichotomy. However, while es relies on morphosyntactic agreement and often implies gender de-emphasis—or, in some contexts, even dehumanization, given its use for inanimates and abstract entities—xier positively encodes a nonbinary gender identity, thereby making gender a semantically active dimension of reference. In this respect, xier parallels es in rejecting binary gender presuppositions, yet diverges crucially in the interpretability and social anchoring of its gender feature. In Table 2, the main semantic features of xier are set out:

Table 2.

Summarizes the semantically relevant features of xier.

Given this, it would therefore be inaccurate to claim that xier lacks gender. On the contrary, xier exhibits a cluster of semantically interpretable φ-features that distinguish it from traditional pronominal forms. As a third-person singular expression, xier is referential and definite, denoting a specific discourse-salient individual. Crucially, it encodes interpretable gender semantics, signaling a nonbinary or non-normatively gendered referent, and thereby expands the conventional gender paradigm beyond the binary opposition marked by er and sie. The pronoun presupposes humanness and animacy, excluding inanimate or abstract referents. While person and number are semantically relevant in constraining reference and predicate compatibility, the most significant semantic innovation of xier lies in its gender feature, which is not defaulted nor grammatically assigned, but contextually grounded in the identity of the referent. Additionally, xier carries socially indexical content, aligning with the speaker’s recognition of the referent’s gender identity. While this indexical dimension lies outside canonical φ-features, it contributes non-trivially to the interpretation and discourse function of the pronoun.

Importantly, nonbinary gender is primarily a social categorization, not one natively encoded in the morphological gender system of German. As such, it could not be accommodated within the pronominal inventory without innovation. This necessitated the intentional introduction of neo-pronouns into both the deictic paradigm and the lexicon of German. The integration of xier has been—and still is—adaptive rather than systemic and has met with resistance from portions of the speech community, at least in early stages of adoption.

The human referent of xier is semantically specified as nonbinary, and this specification is grammatically encoded not via inflectional morphology, but via presupposition. Xier participates in φ-Agree operations just like morphologically gender-marked pronouns; the [Gender] feature it carries is syntactically visible, though its value is not morphologically expressed within the existing binary system.

This account avoids misclassifying xier as a default or repair strategy. Instead, it explains why xier is both referentially precise and socially meaningful. Its felicity is contingent on contextually recoverable presuppositions, supporting a principled distinction between the absence of feature value and contextually licensed valuation. From a theoretical perspective, this proposal motivates a refinement in the treatment of φ-features: φ-Agree can target features that are formally encoded but interpretively valued, extending the empirical reach of minimalist theory without necessitating revisions to its architecture. (The existence of) xier thus shows how socially driven innovations can be formally accommodated within the grammar through mechanisms already available in the theory: presupposition, contextual valuation and syntactic feature visibility.

Under this analysis, the use of nonbinary [GENDER] values does not result in ill-formedness or structural marginality; rather, it is formally encoded in a way that reflects its semantic distinctiveness. Xier is neither a gap-filler nor a placeholder, but a grammatical exponent of a third [Gender] value—syntactically active, semantically rich and pragmatically anchored.

3.3. Formal Integration of xier

Given the semantic profile established above, we can now examine how xier integrates into the φ-feature system at the syntax–semantics interface. Syntactically, xier is merged as a DP in argument position and participates in standard Agree and case-licensing operations. When T probes for φ-features, it locates xier and retrieves a fully specified feature bundle, including an interpretable, nonbinary gender feature. This [Gender] feature is lexically encoded, syntactically visible and semantically interpretable, despite not being part of a binary morphological alternation pattern.

Accordingly, the DP is merged with the φ-feature structure in (24a). T enters the derivation bearing an unvalued φ-probe (24b); upon Agree, the probe is fully valued (24c):

| (24) | a. | [DP xier [φ: [3, Sg, G<nonbinary>]]] |

| b. | T: [uφ: ___ ] | |

| c. | T: [uφ: [3, SG, G<nonbinary>]] |

In sum, while er, sie and es express gender through morphologically distinct forms aligned with the masculine/feminine/neuter system, xier is a dedicated exponent of [Gender: Nonbinary], a value that is grammatically integrated into the φ-feature system and fully active in Agree and interpretation at LF.

Crucially, the [Gender] feature on xier contributes to the presuppositional content of the DP, conditioning felicity in discourse contexts where the referent’s nonbinary identity is accessible or inferable, as seen above. On this view, there is no need to posit a default, repair or underspecified derivation: xier satisfies Agree, licenses case and converges without deviation from established syntactic mechanisms. The proposal thus positions xier as a φ-bearing nominal on par with human-referential, binary-gendered pronouns while capturing the structural integration of nonbinary gender into the existing feature system. It formalizes this integration without requiring any revisions to the architecture of the grammar.

In languages like German, where predicate morphology does not encode φ-features such as [Gender], the integration of a neo-pronoun like xier gives rise to grammatical challenges that are structurally limited. Consequently, xier can appear in predicative contexts without producing apparent agreement “mismatches,” as illustrated in (25a) and (25b). In these examples, (i) xier, like a binary human referent identified by a corresponding conventionally masculine (Hans) or feminine (Maria) proper name, does not trigger the realization of any additional nonbinary inflectional morphology; and (ii) the symbol “ø” marks the absence of an overt morpheme in the relevant position:5

| (25) | a. | Xier | ist | sehr | nett-ø. | |

| xier | be-ind.prs.3sg | very | nice | |||

| ‘That person is/they are very nice.’ | ||||||

| b. | Xier | ist | nicht | gekommen-ø. | ||

| xier | be-ind.prs.3sg | neg | ptcp-come-ptcp | |||

| ‘That person/they did not come.’ | ||||||

The main complications associated with xier in German are thus lexical in nature, arising for the speaker community in contexts where elements such as determiners, possessive pronouns and, in some cases, nominal stems continue to realize gender morphologically (cf. (19) above). While these issues are non-trivial, they remain structurally confined and do not interfere directly with φ-Agree operations at the clausal level.

By contrast, Romance languages such as Italian exhibit a more pervasive system of morphological gender agreement (cf., e.g., D’Alessandro & Roberts, 2008, p. 478; Giusti, 2011, pp. 117–118, Giusti, 2021; D’Alessandro, 2022). The gender system of this language distinguishes only between masculine and feminine, and φ-features are morphologically realized across a broader range of syntactic categories, including adjectives and past participles. This is evident even in basic copular constructions, as illustrated in (26).

| (26) | Italian | ||||

| a. | Il | ragazzo | è | pover-o. | |

| def.sg.m | young-man | be-ind.prs.3sg | poor-sg.m | ||

| ‘That young man is poor.’ | |||||

| (Redolfi, 2022, p. 24) | |||||

| b. | Maria | è | partit-a. | ||

| Maria | aux.ind.prs.3sg | leave-ptcp.sg.f | |||

| ‘Maria has left.’ | |||||

| (Belletti, 2006, p. 495) | |||||

In these constructions, the predicative adjective pover- (‘poor’) and the past participle partit- (‘left’) in the passato prossimo (at least morphologically comparable to the English present perfect) obligatorily agree in gender and number with the subject. Assuming bidirectional Agree as mentioned above, the subject DP in Spec,TP bears fully specified [Gender] and [Number] features, inherited from D along with its case feature. The predicative adjective, positioned lower in the tree, acts as a probe with unvalued gender and number features that search upward to the subject DP to receive their values. This upward valuation mechanism accounts for the observed agreement on predicative adjectives.

As a result, the integration of nonbinary pronouns such as ze—a neo-form originally introduced and adapted from English to express nonbinary identity (e.g., Comandini, 2021)—poses a greater challenge to the grammar. Like xier, ze encodes an interpretable, presuppositional gender feature that is not compatible with the binary opposition encoded in the Italian agreement system. Its use in predicative constructions requires morphological innovation, as shown in (27a) and (27b) (adaptations of the examples in (26); the abbreviation nb in the glosses stands for “nonbinary”):

| (27) | Italian | |||

| a. | Ze | è | pover-ə. | |

| ze | be-ind.prs.3sg | poor-sg.nb | ||

| ‘That person is/they are poor.’ | ||||

| b. | Ze | è | partit-ə. | |

| ze | aux.ind.prs.3sg | leave-ptcp.sg.nb | ||

| ‘That person has left.’ | ||||

In (27a), the adjective appears with a nonstandard suffix -ə (schwa), employed in emergent registers to mark gender-neutral or nonbinary reference either only in the singular and plural (Giusti, 2022, 13ff.; De Cesare, 2024). In (27b), the same suffix is extended to the past participle partitə, replacing the canonical masculine (partito) or feminine (partita) forms.6 Note that standard Italian does not license -ə in these positions, as this variety lacks the vowel entirely in its phonological system. These forms illustrate the extent to which the integration of neo-pronouns in Italian necessitates grammatical reconfiguration: since gender agreement is obligatory in these environments, the system must either adopt novel morphological exponents—some of which pose articulatory challenges for certain speakers—or tolerate systematic agreement mismatches.

The contrast between German and Italian illustrates the typological conditions under which nonbinary pronouns can be integrated with greater or lesser structural friction. In German, where φ-features are not realized on predicative morphology, the grammatical system permits integration without predicate-level agreement mismatches, with complications largely confined to the morphological lexicon. Crucially, however, this structural openness does not entail sociolinguistic accessibility: many speakers, particularly those not actively engaged with gender-inclusive language practices, remain hesitant or unwilling to adopt xier in actual usage. In Italian, by contrast, where gender is a structurally embedded feature of predicate agreement, the addition of a third gender value introduces both morphosyntactic and morphophonological pressures. These involve not only formal constraints on Agree, but also broader issues of learnability, acceptability and the adaptation of grammatical norms within the language community.

Summing up the foregoing discussion, German xier—and, incidentally, also Italian ze, which is not the primary focus here—does not simply omit binary gender values but encodes a positively specified, interpretable [Gender] feature whose value explicitly excludes [Masculine] and [Feminine]. This exclusion is not an output of underspecification or morphosyntactic default, but a grammatically encoded presupposition that the referent is nonbinary or otherwise non-classifiable under binary gender categories. The semantic contribution of xier can be approximated as in (28):

| (28) | ⟦xier⟧ = λx: ¬binary(x). x |

| ‘The individual x such that x is not classifiable under binary gender distinctions.’ |

This presuppositional profile sets xier apart both from semantically ambiguous forms and from φ-complete but referentially minimal pronouns. For example, German es is φ-complete but typically associated with non-individuated or inanimate referents, while English singular they, although compatible with nonbinary reference, does not necessarily presuppose it. In contrast, xier encodes a referential constraint that is both semantically specific and pragmatically regulated: its use is felicitous only in discourse contexts where the referent’s nonbinary identity is accessible or inferable.

At the level of morphosyntactic integration, xier is inserted at Vocabulary Insertion as the exponent of a φ-bundle containing a nonbinary [Gender] value. The relevant insertion rule can be stated as in (29):

| (29) | [Person: 3, Number: Sg, Gender: nb] → xier/D_ |

| ‘Insert the pronoun xier when the morphosyntactic context includes a feature bundle with [Person: 3, Number: Sg, Gender: nb] (i.e., third-person singular with nonbinary gender) and the insertion site is a determiner-level (D) position.’ |

This insertion rule follows directly from standard assumptions in DM, including the Elsewhere Condition (originally, Kiparsky, 1973), which guarantees that xier is selected only when no more specific gender-marked form (e.g., er, sie, es) applies.

Taken together, these facts show that xier is not a placeholder or a morphosyntactic repair form, but a formally licensed, semantically enriched and pragmatically anchored pronominal element. Its φ-feature profile does not merely determine agreement, but conditions felicity at the level of discourse: the referent must not instantiate a value within the binary gender paradigm. In this sense, xier exemplifies presuppositionally conditioned reference—a case where formal licensing is tightly coupled with socially meaningful interpretation.

The difference between underspecified and positively specified gender features is crucial here. An underspecified pronoun such as they in English is lexically compatible with any gender value, and any nonbinary construal must be supplied pragmatically from context. This is not enough to generate the kind of robust, socially anchored presupposition observed with xier. Because xier’s φ-feature bundle contains a positively specified [Gender: Nonbinary] value, it does more than simply refrain from marking [Masculine] or [Feminine]: it grammatically encodes nonbinary identity as part of its conventional meaning. This formal specification ensures that the nonbinary inference projects across embeddings and resists cancelation, making it an inherent property of the pronoun rather than a context-dependent enrichment. The social indexicality associated with xier therefore arises from the interaction of this grammatical feature with discourse-level norms of identity-respect, not from gender underspecification alone.

Against this background and building on the observations made in Section 1, the following section offers a comparative examination of xier and English semantically singular they and focuses on how both elements mediate between φ-feature specification and context-sensitive interpretation at the syntax–semantics interface.

4. Xier and Singular They: A Comparative View

4.1. Feature Architecture and Presuppositional Profile

The analysis developed in the previous section has shown that xier is syntactically merged as a φ-complete DP and enters into agreement relations on a par with binary-gendered pronouns. Its φ-feature bundle includes a lexically specified value for [Gender: Nonbinary], which is morphosyntactically visible and semanto-pragmatically presuppositional. Xier is not underspecified: it does not merely omit [Masculine] or [Feminine], but positively encodes a gender value that presupposes the referent’s non-membership in the binary paradigm. It allows only one semantic interpretation: a referent must be nonbinary or otherwise situated outside the gender binary. This constraint is imposed not merely by pragmatic inference but by the formal properties of the feature bundle passed through the derivation: xier is introduced with a fully specified [Gender: Nonbinary] feature that conditions felicity at LF. However, for the form to be used felicitously in discourse, the speaker must possess or assume contextually relevant knowledge—that the referent self-identifies in a way that falls outside the binary gender paradigm. The interplay between formal specification and speaker-based presupposition thus reflects a deeper coupling between (morpho)syntax, semantics and pragmatic licensing.

The next step is to situate xier within a broader crosslinguistic perspective by contrasting it with English singular they. To make the contrasts between these two elements explicit, Table 3 summarizes the core morphosyntactic, semantic and pragmatic differences before turning to further diagnostics:

Table 3.

Comparison of the morphosyntactic, semantic and pragmatic properties of xier and singular they.

Applying the same projection diagnostics used for xier makes the contrast with singular they explicit. For xier, the “referent-is-nonbinary” inference survives under negation, in questions and in conditional or modal embeddings (cf. Table 1 above), demonstrating the characteristic projection behavior of presuppositional content. For singular they, however, these same contexts yield no such projection: the sentences in (30)–(34) can be interpreted without any commitment to the referent’s gender identity. This shows that they does not lexically encode a [Gender: Nonbinary] feature; any nonbinary construal must be pragmatically derived from context rather than from the pronoun’s conventional meaning:

| (30) | Negation test: If singular they carried a presupposition that the referent was nonbinary, that inference should survive under negation, as it does for xier. In (30a)–(30b), however, both the affirmative and negative sentences are compatible with the referent being of any gender. No backgrounded gender assumption is present. | |

| a. | They are from Berlin | |

| b. | They are not from Berlin. | |

| Both (30a) and (30b) permit interpretations in which the referent is male, female, nonbinary or of unknown gender; no obligatory presupposition projects. | ||

| (31) | Question test: Presuppositions typically survive in polar interrogatives. For xier, Ist xier aus Berlin? (‘Is xier from Berlin?’) still presupposes that the referent is nonbinary. For they, no such presupposition arises: the question can be asked in complete ignorance of the referent’s gender. | |

| Are they from Berlin? | ||

| This interrogative is neutral with respect to gender; no obligatory or automatic nonbinary inference is triggered. | ||

| (32) | Conditional and modal tests: Presuppositions also normally project out of conditional antecedents and modal complements. For xier, such embeddings leave the nonbinary inference intact. In (32a)–(32b), by contrast, the use of they remains gender-neutral: the sentences can be true regardless of the referent’s gender identity. | |

| a. | If they are from Berlin, they probably know Alexanderplatz. | |

| b. | They might be from Berlin. | |

| Neither (32a) nor (32b) entails or presupposes that the referent is nonbinary. | ||

| (33) | “Hey, wait a minute!” test: With xier, a “Hey, wait a minute!” challenge can target the presupposed nonbinary identity. For they, as in the following example, such a challenge is only felicitous if the interlocutor happens to have drawn a contextual inference; it can then be met with a denial that leaves the sentence content intact. | |

| A: | They are from Berlin. | |

| B: | Wait—are you saying Alex is nonbinary? | |

| A: | No—I just don’t know Alex’s gender; “they” was intended generically. | |

| (34) | test: Directly asserting the opposite of the supposed presupposition is normally infelicitous for genuine presuppositions (cf. xier). With they, cancelation is straightforward and acceptable. | |

| I just met the new project manager today. They start next week. Well—I guess I can also say “she”: Alex is actually a cis woman who’s moving here from Berlin. | ||

| In this (diagnostically very transparent) context, they is used initially to refer to a person whose gender is irrelevant to the first part of the statement. The subsequent specification of Alex’s gender is conversationally natural and produces no contradiction, demonstrating that they carries no lexically encoded nonbinary presupposition. The gender information here is entirely at-issue: they may have been used because the speaker did not know or did not wish to specify Alex’s gender, or because they was functioning as a generic pronoun. Once the actual gender is specified, no inconsistency arises, further confirming that no lexically encoded nonbinary presupposition is present. | ||

It should be specified, however, that the nonbinary interpretation of singular they, which is likewise potentially available, is entirely compatible with—and arguably directly facilitated by—the fact that they lacks any lexically specified gender feature. The absence of projection effects in (30)–(34) confirms that singular they does not lexically encode a [Gender: Nonbinary] value and therefore does not grammatically presuppose nonbinary identity. Instead, its gender semantics are underspecified: they denotes an individual or plurality without committing to any specific gender category in its lexical meaning. In contexts where the intended referent is known to be nonbinary, the nonbinary construal of they arises via pragmatic enrichment: the hearer infers the intended identity from discourse context, shared knowledge or explicit metalinguistic framing. Crucially, because this inference is not part of the pronoun’s conventional meaning, it is cancelable without contradiction, as (34) illustrates. The contrast with xier thus hinges on the grammatical source of the gender inference: for xier, the nonbinary specification is lexically presuppositional and projects in the classical sense, whereas for singular they, it is a pragmatic inference derived from underspecification. This distinction highlights how formally similar pronouns in different languages can occupy divergent positions in the morphosyntax–semantics–pragmatics interface, with important consequences for their behavior in both linguistic theory and social practice.

4.2. Morphosyntactic Reuse and Pragmatic Gender Inference

The insertion rule shown in (29) above reflects a dedicated mapping between a nonbinary φ-feature bundle and its overt morphological exponent. As such, xier participates in a system of syntactic agreement, morphological realization and semantic interpretation that is entirely parallel to that of canonical third-person pronouns like er and sie, differing only in gender value.

This sharply contrasts with English singular they, which occupies a radically different point in the morphosyntactic and interpretive space. Morphologically, they retains identity with the third-person plural form. It does not undergo morphological reanalysis or instantiate a distinct insertion rule for its singular, nonbinary use. Syntactically, they is merged with the feature bundle:

| (35) | [Person: 3, Number: Pl, Gender: ∅] → they/D_ |

In other words, there is no distinct syntactic or morphological representation for singular they in English grammar. Its singular use is not encoded through dedicated φ-feature specifications, but instead relies on interpretive flexibility at the syntax–semantics interface. This semantic elasticity enables they to support at least two distinct readings, contextually resolved, as illustrated in (36). These uses can be described as “nonbinary-specific” (36a) and “gender-neutral” (36b). In (36a), the referent is explicitly identified—but could in principle also be inferable through common ground, without the explicitation in the first sentence—as a nonbinary individual, which licenses the semantically enriched use of they as a marker of nonbinary identity. In (36b), instead, they functions as an unspecified, gender-neutral pronoun with no presuppositional commitment to the referent’s gender identity. Here, the antecedent is indefinite and non-identifiable and no gender-related inference is drawn.

| (36) | a. | Nonbinary-specific use (identity-linked) |

| Spike is a nonbinary writer. They recently published a novel about their experiences navigating life outside the gender binary. | ||

| → they=ιx [nonbinary(x)∧x=spike] | ||

| b. | Gender-neutral use (indefinite or de-gendered referents) | |

| There’s always someone in the office who can help. If you need anything, they’ll be happy to assist you. | ||

| → they=λx. human(x)∧gender(x)=unspecified |

While the first reading overlaps semantically with xier, it is contextually inferred rather than grammatically required in the sense that its externalization is otherwise ambiguous. The second reading, by contrast, is (still) unavailable to xier,7 which cannot felicitously refer to indefinite or gender-unspecified individuals. This semantic bifurcation underscores the fact that they is interpreted despite—not because of—its morphosyntactic profile. The pronoun’s plural φ-feature specification is maintained even when it functions as a semantically singular, gender-neutral or nonbinary expression.

This asymmetry has significant theoretical consequences. Whereas xier instantiates a nonbinary gender value via φ-feature specification, they exemplifies semantic reappropriation, that is, a plural form adapted for singular reference in ways that the grammar does not structurally distinguish. This distinction manifests both in presuppositional strength and syntactic behavior. xier is subject to discourse constraints that enforce nonbinary interpretation. Failure to meet this presupposition yields infelicity. The pronoun they, instead, is semantically and pragmatically underspecified and its felicity depends entirely on context.

In DM terms, they reflects insertional economy but interpretive ambiguity: a single exponent is reused across distinct referential contexts. Xier, however, expands the morphological inventory in direct correspondence to a unique φ-feature composition. The contrast is therefore not just semantic or pragmatic, but fundamentally architectural: it concerns how languages allocate featural distinction across lexical items and how interpretive constraints are formalized at the syntax–semantics interface.

In sum, these facts illustrate two distinct mechanisms for enabling socially meaningful reference in natural language:

- Explicit, morphosyntactically transparent encoding via lexical insertion (xier);

- Semantically flexible reinterpretation of an existing morphological form (they).

The distinction reinforces the broader claim that φ-feature systems are sites of both formal constraint and sociolinguistic adaptation, allowing the integration of nonbinary reference through both structural augmentation and pragmatic enrichment.

5. Summary and Conclusions

This paper has examined the morphosyntactic and interpretive properties of the German neo-pronoun xier, arguing that it occupies a well-defined position within the φ-feature architecture, characterized by a lexically specified and interpretable [Gender: Nonbinary] value. Within this framework, xier participates in regular Agree operations, is accessible to syntactic probes and contributes a discourse-level presupposition requiring nonbinary reference.

Unlike English singular they, whose interpretation is context-dependent and—just as the canonical pronoun from which it has been derived—morphosyntactically plural, xier displays a formally encoded referential restriction. Its φ-feature bundle does not reflect underspecification, but instead instantiates a specific, nonbinary value that is both syntactically active and semantically meaningful.

These findings support the broader view that φ-feature systems are capable of encoding socially salient distinctions via formally regular mechanisms. The case of xier demonstrates how pronominal innovation can be accommodated within established syntactic architecture, extending the inventory of interpretable features without requiring structural modification.

While the discussion has focused on xier, this approach may provide a foundation for future research on other emerging German neo-pronouns such as dey (the lexical germanization of English they), sier and nin. These forms raise parallel questions about the interaction between social identity, feature specification, and syntactic licensing—questions that merit further investigation within the framework of minimalist syntax and DM.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In formulas such as (3a), the expression “¬Male(x) ∧ ¬Female(x)” is to be understood as indicating that the referent identifies as neither male nor female rather than representing an objective biological or external classification. This interpretive stance aligns with self-identification and aims to respect the socio-identity dimensions of nonbinary reference. |