Abstract

The present study analyzes individual differences in the facilitative processing of grammatical gender by heritage speakers of Spanish, asking whether these differences correlate with lexical proficiency. Results from an eye-tracking study in the Visual World Paradigm replicate prior findings that, as a group, heritage speakers of Spanish show facilitative processing of gender. Importantly, in a follow-up within-group analysis, we test whether three measures of lexical proficiency—oral picture-naming, verbal fluency, and LexTALE—predict individual performance. We find that lexical proficiency, as measured by LexTALE, predicts overall word recognition; however, we observe no effects of the other measures and no evidence that lexical proficiency modulates the strength of the facilitative effect. Our results highlight the importance of carefully selecting tools for proficiency assessment in experimental studies involving heritage speakers, underscoring that the absence of evidence for an effect of proficiency based on a single measure should not be taken as evidence of absence.

1. Introduction

Aiming for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of language experience and exposure on heritage language development, research in heritage bilingualism is starting to incorporate more measures of individual differences to capture variation both within heritage populations and across heritage and baseline groups. Across different subfields, including first language acquisition (e.g., Kubota & Rothman, 2024; Paradis, 2023) and neuro- and psycholinguistics (Bice & Kroll, 2021; Prystauka et al., 2024), a common approach is to consider individual differences in language experience, language history, and/or language use. In studies of heritage language processing, evidence from heritage speakers (HSs) of Spanish suggests that, in addition to working memory, individual differences in language proficiency, literacy, and language use modulate language processing while reading grammatical and ungrammatical sentences, in either the heritage or dominant language (Bice & Kroll, 2021). Age of first exposure to the majority language has also been found to modulate HSs’ language processing of ungrammatical sentences in eye-tracking while reading (Keating, 2022).

The present study focuses on individual differences in heritage language processing of grammatical gender during spoken word recognition and how these differences correlate with individual differences in lexical proficiency. Recognizing that there are many tools to assess lexical proficiency, and that they may measure different dimensions of lexical proficiency (Zyzik, 2022), we compare the effectiveness of three different tools in predicting HSs’ facilitative processing of grammatical gender.

1.1. Facilitative Processing, Grammatical Gender, and Individual Differences

Facilitative processing of grammatical gender is typically investigated using eye-tracking in the Visual World Paradigm (VWP) (Tanenhaus et al., 1995), in which participants view two or more items on the screen and are instructed to look at or click on the target mentioned in an auditory prompt. Crucially, the prompt includes a pre-nominal element that bears a grammatical gender cue—agreement marking matching with the subsequent target noun (e.g., gender-marked articles in Spanish: masculine el vs. feminine la). When the non-target item(s) is/are of a different gender from the target (here, the “different-gender” condition), the gender marking on the pre-nominal element serves as a disambiguating cue to the target noun. However, when the non-target item(s) is/are of the same gender as the target noun (here, the “same” condition), the pre-nominal element cannot be used as an informative cue to facilitate word recognition of the subsequent noun. Facilitative processing of grammatical gender is evidenced by a higher proportion of looks to the target noun in different-gender trials relative to same condition trials.

Facilitative processing of gender has been reported for adult monolingual speakers of languages like Spanish (Lew-Williams & Fernald, 2007, 2010), German (Hopp & Lemmerth, 2016), Dutch (Brouwer et al., 2017), and Polish (Fuchs, 2023). More recently, similar findings for adult HSs of languages like Russian (Fuchs & Sekerina, 2025; Sekerina, 2015), Spanish (Fuchs, 2021; Fuchs & Zeng, 2024; Keating, 2022), and Polish (Fuchs, 2022) suggest that HSs can use gender cues on pre-nominal elements for facilitative processing, despite commonly observed divergences between HSs and monolinguals in the offline production and comprehension of gender agreement. This target-like processing of gender in HSs may follow from the fact that HSs, like baseline speakers, acquire the target language early and naturalistically (Fuchs, 2021; Grüter et al., 2012; Montrul et al., 2014).

Studies using the VWP involve working memory and both linguistic and visuo-spatial processing; thus, it is perhaps not surprising that individual differences in the efficiency of various cognitive mechanisms can modulate performance in these tasks (Brouwer et al., 2017; Huettig & Janse, 2016). Language exposure and proficiency have also been shown to influence adult HSs’ predictive processing of verb semantics (Prystauka et al., 2024) and morphosyntactic cues such as case (Karaca et al., 2024; Özsoy et al., 2023), as well as how HSs weigh semantic vs. grammatical cues during real-time processing (Hao et al., 2024).

Little work has been performed with respect to individual differences in the facilitative processing of grammatical gender in HSs. To our knowledge, the only paper to pursue this is Pérez-Leroux et al. (2024), which provided a visual assessment of the by-participant facilitative effects of gender in a VWP study and claimed that the distribution of effects for the HSs largely overlapped with those of the baseline speakers, though they did not formally analyze these data. There is a small amount of work on individual differences in other aspects of HSs’ real-time processing of gender (e.g., Hao et al., in press; Keating, 2022). For instance, in an eye-tracking while reading study, Keating (2022) found that, while both baseline speakers and HSs showed sensitivity to mismatches in gender agreement during real-time processing, individual differences in the HS group were influenced by the age of first exposure to the majority language.

1.2. Measuring Lexical Proficiency

There are parallel lines of inquiry into the question of how best to measure proficiency in heritage populations (for an overview in Heritage Spanish, see Zyzik, 2022). Given the aims of the current study, we focus on lexical proficiency. Importantly, HSs’ lexical proficiency has been found to be correlated with broader grammatical competence (Montrul, 2016, chap. 3; Polinsky, 2018, chap. 7). Vocabulary knowledge encompasses many different dimensions. Therefore, when investigating the role of individual differences in an experimental task, the utility of any single measure of lexical proficiency may be some function of which dimension of vocabulary knowledge it captures, what the target population is, and what the nature of the main experimental task is (Zyzik, 2022). Broadly, tools for measuring lexical proficiency can be categorized as those that involve recall vs. recognition, which is further crossed with whether the tools target form, meaning, or both (Zyzik, 2022). Here, we introduce different approaches to assessing lexical proficiency via the three measures selected for the present study.

The first measure is oral picture-naming, which entails recall of form. In a picture-naming task, participants view images and must identify or recall the appropriate lexical item from memory and subsequently produce the item. This process links visual recognition to lexical production, thus objectively measuring semantic processing and lexical retrieval (Garcia & Gollan, 2022). Picture-naming tasks can be standardized—e.g., the MINT and MINT Sprint (Garcia & Gollan, 2022; Gollan et al., 2012)—or non-standardized (e.g., Fuchs, 2021; Montrul et al., 2013). Research has found that bilinguals differ from monolinguals in speed and accuracy during picture-naming in their non-dominant language and perhaps even in their dominant language (Gollan et al., 2005; Gollan et al., 2012; Ivanova & Costa, 2008). However, HSs still outperform traditional L2 learners, reflecting the modality-specific advantage for HSs in tasks aligned with their naturalistic exposure to the heritage language (Montrul et al., 2008, 2013).

The second measure of lexical proficiency that we test is a verbal fluency (VF) task, which entails recall of form and meaning. In a VF task, participants are prompted by a semantic category or a letter and must produce as many words within that category or starting with that letter as possible within a set amount of time (Lezak et al., 2012). VF tasks thus measure productive proficiency and general cognitive functioning, and both linguistic abilities and executive control influence the number of words a participant produces (Shao et al., 2014). Performance on VF tasks has been shown to correlate positively with vocabulary size (Dubé & Thordardottir, 2024; Sauzéon et al., 2011) and age of arrival in bilingual participants (Portocarrero et al., 2007). VF has also been found to correlate positively with oral picture-naming as measured by the MINT Sprint (Garcia & Gollan, 2022) and with self-reported proficiency scores in HSs of various languages (Macbeth et al., 2022).

The final measure of lexical proficiency tested in the present study is the Spanish version of the Lexical Test for Advanced Learners of English (LexTALE), which entails recognition of form. In this task, participants view a list of written real and nonwords and determine whether each item is a real word, with penalties applied for incorrect answers. The task is thus an untimed lexical decision task that measures receptive vocabulary knowledge. The LexTALE was originally developed to assess L2 proficiency in English by Lemhöfer and Broersma (2012). Research on the LexTALE has demonstrated its effectiveness in capturing lexical knowledge and proficiency differences (e.g., Diependaele et al., 2013; Khare et al., 2013), but findings generally suggest that it is more effective in high proficiency than low proficiency bilinguals (e.g., Nakata et al., 2020; Puig-Mayenco et al., 2023; Vermeiren & Brysbaert, 2024), with whom picture-naming tasks have been found to be more effective (Liu & Chaouch-Orozco, 2024). Additionally, the LexTALE entails recognition of form only, and not meaning, which may constitute a limitation relative to meaning-focused vocabulary assessments (Fairclough, 2011; Vermeiren & Brysbaert, 2024). The Spanish version, the LexTALE-Esp, was developed by Izura et al. (2014) and includes 60 real words, selected from the Subtlex-Esp database of Spanish word frequencies based on film subtitles (Cuetos et al., 2011), and 30 Spanish nonwords. Like the English version, LexTALE-Esp has been shown to reliably distinguish proficiency levels among highly proficient bilinguals (Ferré & Brysbaert, 2017; Margaretto & Brysbaert, 2022), and LexTALE-Esp has been shown to correlate more with reading comprehension than with general knowledge (Margaretto & Brysbaert, 2022). Henceforth, we will use “LexTALE” as shorthand for “LexTALE-Esp”.

1.3. Research Questions and Approach

In the present study, we investigate how individual differences in lexical proficiency correlate with facilitative processing of grammatical gender in Heritage Spanish. The latter has been consistently found at the group-level for HSs of Spanish (Fuchs, 2021; Fuchs & Zeng, 2024; Keating, 2022, 2024; Pérez-Leroux et al., 2024), and we expect to replicate these results by observing a main effect of condition (same vs. different gender; cf. Section 1.1). The study reported here additionally manipulated number—i.e., the determiner occurred in the singular (el/la) or plural (los/las). However, the outcome of this manipulation is beyond the scope of the present investigation; we analyze and report results from the subset of the data in which articles were singular, as this most closely resembles critical conditions in prior studies on facilitative processing of gender. Results of the number manipulation will be analyzed and reported elsewhere.

For the individual differences approach, given that word recognition—and thus lexical knowledge—plays a key role in VWP studies investigating facilitative processing of gender, we expect that lexical proficiency measures may help explain within-group variation in performance on these tasks. Specifically, we aim to determine whether lexical proficiency correlates with (a) overall performance on the VWP task (i.e., a main effect) and/or (b) the strength of the same vs. different gender effect (i.e., an interaction effect). The latter effect would be indicative of lexical proficiency correlating with more efficient facilitative processing of gender.

Additionally, we aim to compare three different measures of lexical proficiency in this context, targeting different dimensions of vocabulary knowledge (per Section 1.2): oral picture-naming (recall of form), VF (recall of form and meaning), and LexTALE (recognition of form). For the picture-naming task, we use a non-standardized version. Non-standardized picture-naming is independently useful in eye-tracking studies in the VWP, particularly with bilingual populations, in assessing participants’ lexical proficiency as well as their familiarity with experimental nouns and their gender (Fuchs, 2021, 2022; Hopp, 2013, 2016; Lemmerth & Hopp, 2019). However, one possible limitation is that, unlike in standardized picture-naming, in which the frequency of target items deliberately spans a wide range to capture more within-group variability, images selected for non-standardized tasks as part of VWP studies tend to have a narrower range in frequency for reasons of experimental design, possibly limiting the range of variability that can be observed. Still, participants have been shown to demonstrate a broad range of performances. Indeed, a study on L2 German found a correlation between accuracy on agreement marking in a picture-naming task and facilitative processing (Hopp, 2013). For measuring VF, we use a semantic VF task, given that semantic VF tasks are less sensitive to variation in executive control (Friesen et al., 2015; Gollan et al., 2002; Portocarrero et al., 2007). Moreover, Rommers et al. (2015) found that performance on a semantic VF task was correlated with individual variation in anticipatory processing in the VWP in a monolingual population. We note that our set of lexical proficiency measures does not represent the full range of possible measures of lexical proficiency, a limitation we discuss further in Section 4.

Although the number of studies targeting HSs’ facilitative processing is steadily increasing, only a small subset of these studies investigates individual differences (Keating, 2022; Pérez-Leroux et al., 2024; Prystauka et al., 2024), and none, to our knowledge, investigates the relationship between facilitative processing and lexical proficiency. From the psycholinguistic perspective, our study will provide insight into the dimension(s) of lexical proficiency that correlate(s) most strongly with HSs’ real-time auditory word recognition and facilitative processing. From a practical perspective, the outcome of our study may allow future research in this vein to decide which measure(s) of lexical proficiency to include in an experimental protocol when resource limitations do not allow a full battery of language proficiency assessments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eye-Tracking Materials

Forty grayscale images of concrete, picturable objects were selected: 20 represented masculine nouns and 20 represented feminine nouns. All masculine nouns ended in -o and feminine nouns ended in -a, as these are the word markers typically associated with these genders (sometimes referred to as “transparent gender”). No two target nouns were gender alternates of each other; in other words, while libro “bookM” was a target noun, libra “poundF” was not. For work on gender-alternating transparent nouns, see Pérez-Leroux et al. (2024). A complete list of target nouns for this project may be found on the OSF repository.

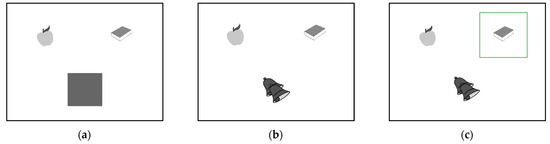

Target nouns were masculine or feminine and occurred in the singular or plural, across five conditions (Table 1), yielding a 5 × 2 × 2 design; the analysis reported below includes only the gender manipulation and only the same and different-gender conditions, holding the number of the target noun (singular) constant. Images were combined into visual displays with three images per display and no fixation cross (Figure 1a). Each noun occurred approximately an equal number of times as a target, competitor, or distractor. In each trial, the three nouns each had a different first phoneme, such that the phonological onset of the noun in the auditory prompt was an unambiguous cue to the target item regardless of experimental condition.

Table 1.

Experimental conditions for the VWP task, illustrated for M SG targets. Only the first two conditions are analyzed in the present study.

Figure 1.

The unfolding of each trial is illustrated here using a display from the different-gender condition with a M SG target: (a) an opaque box covered one of the images (here, the distractor) from the start of the trial; (b) the box disappeared 200 ms after the onset of the target noun in the audio prompt; (c) if the participant selected the target, a green square appeared.

In the critical conditions for the present study, the distractor was always of a different gender and number from the target. The competitor was always of the same number (singular) as the target. The crucial manipulation for the present research question was the gender of the competitor: In the same condition, the competitor was of the same gender as the target, and in the different-gender condition, the competitor was of the opposite gender as the target. The three other experimental conditions (see Table 1), as well as trials with plural target nouns, were implemented for reasons related to a research question not discussed in the present paper and are not included in the analysis here.

For reasons tangential to the present study, we combined the VWP with the Covered Box Paradigm (Schwarz et al., 2016), as a variant of the target-absent VWP (Fuchs, 2025; Huettig & Altmann, 2005). At the start of each trial, one of the images in the display was covered by an opaque square. This square disappeared to reveal the third image 200 ms after the onset of the noun in the audio prompt (Figure 1). In half of the experimental trials, the box covered the target item; in the other half, the box covered the distractor. Only trials in which the box covered the distractor—and the target was visible from the onset of the trial—are included in the analysis in Section 3. There were 400 total experimental stimuli, pseudo-randomly arranged into two experimental lists, such that each participant saw 200 experimental trials.

Each visual display was paired with an auditory prompt of the form Indica {el/la/los/las} [target noun]. (“Indicate the{M/F}-{SG/PL} [target noun].”). All stimuli were recorded as full sentences by a speaker of Colombian Spanish living in the US at the time of recording. From these recordings, a single token of Indica (925ms), el (508 ms), la (504 ms), los (527 ms), las (510 ms), and the singular and plural forms of each noun were selected and concatenated to ensure that the onset of the gender-marked article occurred at the same point in each trial and that the onset of the noun occurred at approximately the same point in each trial.

Each trial began with 500 ms of looking time prior to the onset of the audio prompt. Participants were instructed to click on the target item as quickly as possible. If participants did this successfully, a green square appeared around the target image (Figure 1c). Each trial lasted 4 s, and the mouse cursor was reset to the center of the screen between each trial.

2.2. Materials for Measuring Lexical Proficiency

The oral picture-naming task consisted of the 40 images included in the eye-tracking task. Participants viewed each image individually on a laptop and were instructed to name each image using an article and a noun, speaking into a microphone while their voice was recorded. Participants proceeded to each next image by pressing the right arrow on the keyboard. The task was self-timed, and participants were instructed that they could skip any word they were unfamiliar with.

The VF task consisted of three test semantic categories (vegetables, clothing items, musical instruments; order randomized per participant), and participants had 60 s per category to name as many words in Spanish as possible, speaking into a microphone while their voice was recorded. Participants first completed a practice trial (category: fruit) and were given a self-timed break between each category.

The LexTALE was obtained from www.lextale.com. Participants were presented with the instructions and completed the task in written form, on pen and paper.

2.3. Participants

Eighty-two native Spanish speakers participated in the study in person at a university in a major US city. Participants were identified as HSs or Spanish-dominant late Spanish-English bilinguals based on their self-reported language background. HSs (n = 53; mean age: 20.2 (sd = 2.2); mean age of arrival to the US: 0.9 (sd = 2.1)) were those who reported learning Spanish from birth and having spent 6 years or less in a Spanish-speaking country. Late bilinguals (n = 23; mean age: 24.4 (sd = 5.8); mean age of arrival to the US: 22.7 (sd = 5.7)) were those who reported learning Spanish and English sequentially and having spent at least 18 years in a Spanish-speaking country. Data from 6 participants were excluded from analysis because their self-reports were not compatible with the inclusion criteria for either group.

2.4. Procedure

Participants first read an information sheet and gave informed consent to participate in the study before completing the oral picture-naming task. This took place before the eye-tracking task in order to assess participants’ familiarity with the experimental nouns.

Participants then completed the eye-tracking task. They sat facing a 24-inch screen with their head stabilized approximately 36 inches from the screen. They received written instructions in Spanish and optionally received oral instructions in English before completing three practice trials. The experimenter then completed a 9-point calibration of the SR Research EyeLink 1000 Plus eyetracker; tracking was monocular. The experimental trials were randomly split into three blocks; participants were given a self-timed break after each block, and calibration was repeated prior to each block.

After completing the eye-tracking task, participants completed the VF task on a laptop. They then completed the LexTALE and the language background questionnaire, both on paper. The questionnaire was an abbreviated and modified version of the Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q) (Kaushanskaya et al., 2020; Marian et al., 2007).

2.5. Data Preparation

Data were extracted using SR Research DataViewer and prepared in R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021) using the package eyetrackingR version 0.2.0 (Forbes et al., 2023). As discussed, data from the same condition and the different-gender condition for singular target nouns were included in the analysis, as the present research questions pertain only to this subset of conditions, which correspond directly to those in prior studies on facilitative processing of gender (Fuchs, 2021; Fuchs & Zeng, 2024; Grüter et al., 2012; Keating, 2022, 2024; Lew-Williams & Fernald, 2007, 2010).

For the group analysis investigating whether the facilitative effect of gender was replicated in the current study (Section 3.2), a cluster-based permutation analysis was implemented to identify time clusters in which there was a significant effect of the contrast between the same vs. different-gender condition on the proportion of fixations to the target item (Ito & Knoeferle, 2022; Maris & Oostenveld, 2007). Data were binned into time bins of 50 ms. Separate analyses were run for the heritage group and the late-bilingual group. In each analysis, generalized mixed effects models were fitted to the data in each time bin, predicting the empirical logit of the proportion of fixations to the target by condition, with by-participant and by-item random intercepts. The data were permuted 1000 times.

For the individual differences analysis (Section 3.3), for each participant and trial, the proportion of looks to the target item from the onset of the article to the end of the trial was calculated. Trials with an average proportion of zero looks to the target over the course of the trial were excluded from analysis. The analysis was conducted by fitting mixed effects regression models predicting log-transformed proportion of looks to the target item (e.g., Huettig & Janse, 2016). P-values were obtained using the Satterthwaite method in lmerTest version 3.1-3 (Kuznetsova et al., 2017).

For the proficiency measures, responses to the picture-naming task were coded by a native Spanish speaker. An individual response was coded as correct if the participant produced the word intended by the experimental materials, or if the participant produced a word that the coder considered to be an appropriate dialectal or lexical equivalent. Responses to the VF task were coded by the same native Spanish speaker and one highly proficient L2 Spanish speaker. Coders calculated the total number of accurate words per category, with accurate words defined as those judged to be real Spanish words that fit into the semantic category. The number of words uttered in English or words that did not match the category was subtracted from a participant’s score; words that were synonyms or repetitions of previously uttered words were discounted. The coders gave the same score to 66% of participants. In cases of coder disagreement, on average, the difference between the scores was 2.4. Participant’s final VF score was the average of the two coders’ scores. Consistent with standard procedure, LexTALE scores were obtained by calculating the number of words correctly identified as real words, and subtracting from that double the number of non-words incorrectly identified as real words (Izura et al., 2014; Lemhöfer & Broersma, 2012).

3. Results

3.1. Facilitative Use of Grammatical Gender

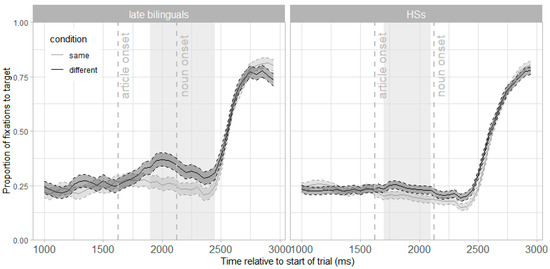

Visual inspection of Figure 2 suggests an effect of condition for both groups, albeit smaller for the HSs. A cluster-based permutation analysis of looks to the target for the late bilingual group revealed a significant cluster for the effect of condition for the period of 1900 ms to 2450 ms after the start of the trial (cluster mass statistic = 112.0, p < 0.001). A similar analysis conducted for the HS group found a significant cluster for the effect of condition for the period from 1700 ms to 2100 ms from the start of the trial (cluster mass statistic = 55.8, p < 0.001). These results indicate that the effect of condition was indeed significant for both groups, replicating prior studies on the facilitative use of grammatical gender in adult heritage bilingual speakers of Spanish (Fuchs, 2021; Fuchs & Zeng, 2024; Keating, 2022, 2024).1

Figure 2.

Proportion of looks to the target item from the start of the trial in the same vs. different-gender trials, split by participant group. Shaded areas indicate significant clusters for the effect of condition—as identified using the cluster-based permutation analysis presented in Section 3.2.

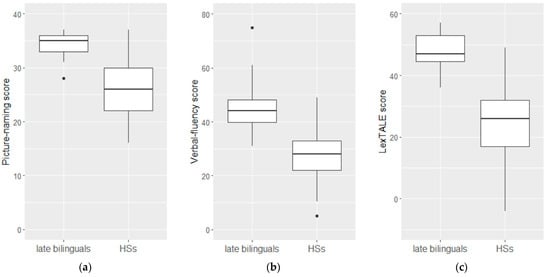

3.2. Lexical Proficiency Results

In this section, we present the distribution of participant scores (untransformed) on each of the measures of lexical proficiency. On the picture-naming task (Figure 3a), participants in the late-bilingual group, on average, correctly named 34.1 words (sd = 2.1) out of 40, and the HSs correctly named 26.2 (sd = 5.2). On the VF task (Figure 3b), which has no maximum score, participants in the late-bilingual group on average produced 45.1 Spanish words (sd = 9.5) and HSs on average produced 26.8 (sd = 8.8). On the LexTALE (Figure 3c), which has a maximum score of 60, late-bilingual participants on average scored 47.5 (sd = 5.91), and HSs on average scored 24.4 (sd = 11.5). Differences between the two groups were found to be statistically significant for all three measures, as determined by two-tailed Wilcoxon tests (p < 0.001 in all three cases). All three measures were also significantly correlated with each other, as determined by Spearman’s Rho tests for correlation (picture-naming and VF: ρ = 0.71, p < 0.001; picture-naming and LexTALE: ρ = 0.79, p < 0.001; VF and LexTALE: ρ = 0.75, p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

The distribution of participants’ lexical proficiency scores, split by group, on the (a) picture-naming task, (b) VF task, and (c) LexTALE. Black dots indicate outliers.

In all three proficiency measures, the late bilingual group showed higher lexical proficiency scores overall. We do, however, note a considerable amount of overlap between the two groups, with roughly the top 25% of the HS group performing within the same range as the late bilinguals on all three measures, though we stress that this is based solely on numerical and visual assessment.

3.3. Individual Differences Among HSs: Predicting Facilitative Use of Gender by Lexical Proficiency

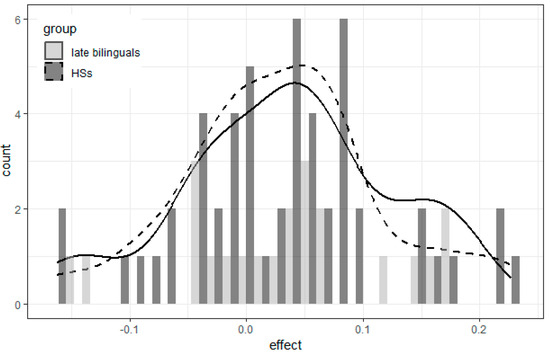

Although our primary goal is to investigate within-HS differences, we first plot the by-participant average facilitative effect of gender in order to visually compare the distribution of the effect sizes between the heritage and late-bilingual groups (Figure 4). Each participant’s average facilitative effect is taken to be the difference between their average proportion of fixations to the target in different-gender condition trials minus the average for same condition trials. Consistent with Pérez-Leroux et al. (2024), visual assessment suggests that the two groups largely overlap, including having some participants with negative effect sizes.

Figure 4.

By-participant facilitative effects for the late-bilingual and heritage groups, overlaid with density curves to show generally overlapping distributions.

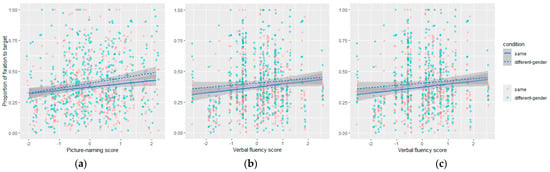

Figure 5 visualizes the relationship between condition, lexical proficiency, and proportion of looks to the target in the HS group; each observation represents a single trial for a single participant. To determine which measure(s) of lexical proficiency correlate(s) with performance in the task, we followed a hierarchical regression modeling procedure2 to determine whether a given measure or its interaction with condition improved model fit, using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for non-nested model comparison. The condition variable was simple-coded such that the same condition was the baseline (same = 0; different-gender = 1). HSs’ proficiency scores for each measure were z-transformed.3

Figure 5.

Relationship between HS participants’ proportion of looks to the target item in same vs. different-gender conditions and their lexical proficiency as measured by the (a) picture-naming task, (b) VF task, and (c) LexTALE.

The best-fitting model predicted the log-transformed proportion of looks to the target by condition and LexTALE score, with random intercepts grouped by participant. The model found a significant effect of condition (β = 0.09, SE = 0.05, t = 1.99, p = 0.047), whereby the proportion of looks to the target increased in the different-gender condition relative to the same condition. This is consistent with the results in Section 3.2. The model also found a significant effect of LexTALE (β = 0.15, SE = 0.05, t = 3.27, p = 0.002). The full results of the model are presented in Table 2. Consistent with the results of the non-nested model comparison using AIC reported above, a nested model comparison using ANOVA found that an interaction effect between condition and LexTALE did not significantly improve the model (χ2 = 2.74, p = 0.098).

Table 2.

Results of the best-fitting regression model.

4. Discussion

The results of the cluster-based permutation analysis (Section 3.1) found a significant effect of condition for both the HSs and the late bilingual group, indicating more looks to the target following the article in the different-gender condition relative to the same condition. This is evidence for the group-level facilitative effect of gender, replicating previous findings for HSs of Spanish (Fuchs, 2021; Fuchs & Zeng, 2024; Keating, 2022; Pérez-Leroux et al., 2024). Additionally, the distribution of individual facilitative effects for the HSs was numerically comparable in range to that of the late Spanish-English bilinguals (Figure 4), consistent with findings in Pérez-Leroux et al. (2024).

The three lexical proficiency measures (oral picture-naming, verbal fluency, and LexTALE) all showed that the HSs had, on average, lower proficiency scores than the late bilinguals (Section 3.2). The within-group analysis of HSs’ facilitative processing (Section 3.3) investigated whether lexical proficiency modulated individual differences in HSs’ looks to the target in the VWP task and found a reliable effect of condition consistent with the results of the cluster-based permutation analysis in Section 3.2. Importantly, of the three lexical proficiency measures, only LexTALE was found to be a significant predictor of looks to the target. Because the VWP task entails auditory word recognition and thus lexical retrieval, we expected that lexical proficiency would predict performance on the task. The significant main effect of LexTALE suggests that, broadly, lexical proficiency does indeed modulate HSs’ auditory word recognition, and this result constitutes a novel contribution to work on individual differences in heritage language processing.

It remains an open question as to why LexTALE yielded a significant effect, whereas the VF and picture-naming tasks did not. That LexTALE scores predicted performance on the task may be surprising, given that this was the only lexical proficiency task that relied on literacy and spelling in the heritage language, known to be a limitation in heritage language studies (Llombart-Huesca & Zyzik, 2019). Still, the present study is in line with previous findings that LexTALE scores predict auditory word recognition (Fricke, 2022) and anticipatory processing in Spanish-English bilingual populations (Fricke & Zirnstein, 2022), though these latter findings were shown for anticipatory processing of semantic rather than grammatical cues. Concurrent work on individual differences in Heritage Spanish language processing has found that HSs with higher LexTALE scores show a higher P600 effect in response to errors in gender agreement (Hao et al., in press), lending further evidence for the utility of LexTALE in investigating individual differences in heritage language processing. For the present study, an additional consideration is that LexTALE is the only lexical proficiency measure that we used that tested receptive rather than productive vocabulary knowledge. Receptive vocabulary tasks may capture a larger range of HSs’ vocabulary (Zyzik, 2022), and there is even evidence that this is true of written lexical decision tasks (Fairclough, 2011). Notably, this also aligns with the nature of the VWP task, which, by measuring auditory word recognition, also taps into receptive vocabulary knowledge. If this reasoning is on the right track, we might expect other measures of receptive vocabulary, such as those that rely on recognition of meaning, to also be predictive in this experimental context. One such measure to consider in future work is a multiple-choice picture-matching task like the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) (Dunn & Dunn, 2007); the Spanish-language version of the PPVT is the Test de Vocabulario en Imagines Peabody (TVIP) (Dunn et al., 1986). The lack of a task tapping into the recognition of meaning dimension of vocabulary knowledge in the present study is certainly a limitation. Finally, the LexTALE scores numerically showed the most within-group variability for HSs, which perhaps made it easier to identify meaningful variation in the results.

As to why picture-naming and VF did not significantly predict word recognition in the VWP task, we refrain from over-interpreting these findings as they constitute null results, which could be due to a lack of power rather than a meaningful absence of a relationship between scores on these measures and auditory word recognition. Still, we find the differences in results for the three measures of proficiency to be notable, as they highlight that studies that use only a single measure of proficiency and do not find an effect should proceed with caution in interpreting such a finding as evidence for the absence of an effect of proficiency on performance.

Having established that lexical proficiency modulates auditory word recognition in the VWP task, we asked whether it also modulates facilitative processing of gender, which would be evidenced by an interaction between condition and any one of the proficiency measures. Hierarchical regression modeling revealed that interaction effects between condition and the lexical proficiency measures might not contribute meaningfully to the model, suggesting a lack of evidence for a modulating effect of lexical proficiency on the facilitative effect of gender. However, as stated above, we refrain from over-interpreting this null effect, given that interaction effects in particular typically require high statistical power (Brysbaert, 2019).

5. Conclusions

The present study conducted an individual differences analysis of results from a VWP study on facilitative processing of grammatical gender in HSs of Spanish and late Spanish–English bilinguals. At the group-level, HSs showed a facilitative effect of gender, similar to the late-bilingual group and consistent with previous work in this domain (e.g., Fuchs, 2021; Fuchs & Zeng, 2024; Keating, 2022; Pérez-Leroux et al., 2024). The subsequent individual differences analysis of HSs’ results found that lexical proficiency predicted HSs’ overall task performance (higher proficiency scores were associated with a higher proportion of target fixations) but did not find evidence that lexical proficiency modulates the strength of the facilitative effect of gender.

This work adds to the existing literature on individual differences in heritage language processing, particularly facilitative processing of gender. Prior work found that exposure-related factors such as the age of onset of bilingualism modulated these processing patterns (Keating, 2022). We find that lexical proficiency, particularly recognition of form—as measured by LexTALE—modulates overall performance on the experimental task. However, the finding that not all measures of lexical proficiency were significant predictors in our analysis underscores the importance of careful selection of proficiency measurement tools. This result also highlights that the absence of an effect of a single measure of proficiency should not be taken to be evidence of the absence of an effect of proficiency in a given experimental context. We invite future work to conduct similar systematic comparisons of tools for measuring lexical proficiency in psycholinguistic studies of heritage language processing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.F. and E.K.; methodology, Z.F. and E.K.; formal analysis, Z.F. and E.K.; investigation, Z.F., A.R., E.E.-T., L.P., and L.M.; resources, Z.F.; data curation, Z.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.F., E.K., A.R., E.E.-T., L.P., L.M., M.O., and Y.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.F., E.K., A.R., E.E.-T., L.P., L.M., M.O., Y.C., S.H., C.P., and J.S.; visualization, Z.F.; supervision, Z.F.; project administration, Z.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California (application ID UP-22-01091, approved on 26 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Experimental materials, data, and code for analysis supporting reported results can be found on the first author’s OSF page at https://osf.io/5ydjh/?view_only=aa0cfc9db3a94800b63782cb8e5963a2 (accessed on 26 July 2025).

Acknowledgments

For helpful feedback and discussion, we would like to thank audiences at the USC Psycholinguistics Lab, the UCLA Department of Spanish & Portuguese, the Linguistics Department at CUNY Graduate Center, the 15th Heritage Language Institute, the 2024 Mayfest at the University of Maryland, and the 2025 meeting of the Human Sentence Processing conference. For support with data collection and processing, we would like to thank Jiamin Cheng and Damaris Ortega. All errors are our own.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| F | Feminine |

| M | Masculine |

| PL | Plural |

| SG | Singular |

Notes

| 1 | We note that cluster-based permutation analyses are the current best method for testing for an effect of a manipulation between conditions in a VWP study, but they are less reliable for estimating the onset of an identified effect (Ito & Knoeferle, 2022). For this reason, we do not make any claims pertaining to the relative onset of the effect of condition between the two groups; this matter is also not relevant to our current research questions. |

| 2 | Thank you to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this analytical approach. |

| 3 | Given the significant correlations between raw scores on the three measures of lexical proficiency reported in Section 3.2, we calculated the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for predictors in every model that contained more than one measure of lexical proficiency, to check for multicollinearity. All VIFs were found to be below 3 (a typical cut-off value is 5), indicating that although there was some inflation of the variance of predictor slopes in these models, high multicollinearity was not a major concern. |

References

- Bice, K., & Kroll, J. F. (2021). Grammatical processing in two languages: How individual differences in language experience and cognitive abilities shape comprehension in heritage bilinguals. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 58, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, S., Sprenger, S., & Unsworth, S. (2017). Processing grammatical gender in Dutch: Evidence from eye movements. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 159, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M. (2019). How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. In Journal of cognition (Vol. 2, Issue 1). Ubiquity Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuetos, F., Glez-Nosti, M., Barbón, A., & Brysbaert, M. (2011). SUBTLEX-ESP: Spanish word frequencies based on film subtitles. Psicológica, 32, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Diependaele, K., Lemhöfer, K., & Brysbaert, M. (2013). The word frequency effect in first-and second-language word recognition: A lexical entrenchment account. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66(5), 843–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, D., & Thordardottir, E. (2024). Using semantic verbal fluency to estimate the relative and absolute vocabulary size of bilinguals: An exploratory study of children and adolescents. Journal of Communication Disorders, 111, 106450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). Peabody picture vocabulary test (4th ed.). American Guidance Services, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L. M., Padilla, E. R., Lugo, D. E., & Dunn, L. M. (1986). Test de vocabulario en imagenes peabody: TVIP: Adaptacion hispanoamericana (Peabody picture vocabulary test: PPVT: Hispanic-American adaptation). American Guidance Service (AGS), Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, M. (2011). Testing the lexical recognition task with Spanish/English bilinguals in the United States. Language Testing, 28(2), 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, P., & Brysbaert, M. (2017). Can Lextale-Esp discriminate between groups of highly proficient Catalan–Spanish bilinguals with different language dominances? Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S., Dink, J., & Ferguson, B. (2023). eyetrackingR. Available online: http://www.eyetracking-r.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Fricke, M. (2022). Modulation of cross-language activation during bilingual auditory word recognition: Effects of language experience but not competing background noise. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 674157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, M., & Zirnstein, M. (2022). Predictive processing and inhibitory control drive semantic enhancements for non-dominant language word recognition in noise. Languages, 7, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, D. C., Luo, L., Luk, G., & Bialystok, E. (2015). Proficiency and control in verbal fluency performance across the lifespan for monolinguals and bilinguals. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 30(3), 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, Z. (2021). Facilitative use of grammatical gender in heritage Spanish. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 12, 845–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Z. (2022). Eyetracking evidence for heritage speakers’ access to abstract syntactic agreement features in real-time processing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 960376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, Z. (2023). Processing of grammatical gender agreement morphemes in Polish: Evidence from the Visual World Paradigm. Morphology, 34, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Z. (2025). Independent processing of lexical features on portmanteau morphemes: Evidence from Polish. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Z., & Sekerina, I. (2025). New evidence for the role of morphological markedness of gender agreement cues in monolingual and heritage-bilingual facilitative processing. In L. Clemens, V. Gribanova, & G. Scontras (Eds.), Syntax in uncharted territories: Essays in honor of Maria Polinsky (pp. 215–232). UC Irvine. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9rk3n45s (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Fuchs, Z., & Zeng, W. (2024). Facilitative processing of grammatical gender in heritage speakers with two gender systems. Heritage Language Journal, 21(1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D. L., & Gollan, T. H. (2022). The MINT sprint: Exploring a fast administration procedure with an expanded multilingual naming test. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 28(8), 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollan, T. H., Montoya, R. I., Fennema-Notestine, C., & Morris, S. K. (2005). Bilingualism affects picture naming but not picture classification. Memory & Cognition, 33(7), 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollan, T. H., Montoya, R. I., & Werner, G. A. (2002). Semantic and letter fluency in Spanish-English bilinguals. Neuropsychology, 16(4), 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gollan, T. H., Weissberger, G. H., Runnqvist, E., Montoya, R. I., & Cera, C. M. (2012). Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish-English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(3), 594–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grüter, T., Lew-Williams, C., & Fernald, A. (2012). Grammatical gender in L2: A production or a real-time processing problem? Second Language Research, 28(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J., Kubota, M., Bayram, F., González Alonso, J., Grüter, T., Li, M., & Rothman, J. (2024). Schooling and language usage matter in heritage bilingual processing: Sortal classifiers in Mandarin. Second Language Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J., Rossi, E., Nakamura, M., Luque, A., & Rothman, J. (in press). Individual differences matter in heritage language bilingual processing: Grammatical gender and ERPs. Studies in Second Language Acquisiton.

- Hopp, H. (2013). Grammatical gender in adult L2 acquisition: Relations between lexical and syntactic variability. Second Language Research, 29(1), 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, H. (2016). Learning (not) to predict: Grammatical gender processing in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 32(2), 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, H., & Lemmerth, N. (2016). Lexical and syntactic congruency in L2 predictive gender processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(1), 171–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huettig, F., & Altmann, G. T. M. (2005). Word meaning and the control of eye fixation: Semantic competitor effects and the visual world paradigm. Cognition, 96(1), B23–B32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huettig, F., & Janse, E. (2016). Individual differences in working memory and processing speed predict anticipatory spoken language processing in the visual world. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 31(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A., & Knoeferle, P. (2022). Analysing data from the psycholinguistic visual-world paradigm: Comparison of different analysis methods. Behavior Research Methods, 55, 3461–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, I., & Costa, A. (2008). Does bilingualism hamper lexical access in speech production? Acta Psychologica, 127(2), 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izura, C., Cuetos, F., & Brysbaert, M. (2014). Lextale-Esp: A test to rapidly and efficiently assess the Spanish vocabulary size. Psicológica, 35(1), 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca, F., Brouwer, S., Unsworth, S., & Huettig, F. (2024). Morphosyntactic predictive processing in adult heritage speakers: Effects of cue availability and spoken and written language experience. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 39(1), 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushanskaya, M., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Marian, V. (2020). The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Ten years later. Bilingualism, 23(5), 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, G. D. (2022). The Effect of Age of Onset of Bilingualism on Gender Agreement Processing in Spanish as a Heritage Language. Language Learning, 72(4), 1170–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, G. D. (2024). Morphological markedness and the temporal dynamics of gender agreement processing in Spanish as a majority and a heritage Language. Language Learning, 75, 146–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, V., Verma, A., Kar, B., Srinivasan, N., & Brysbaert, M. (2013). Bilingualism and the increased attentional blink effect: Evidence that the difference between bilinguals and monolinguals generalizes to different levels of second language proficiency. Psychological Research, 77(6), 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, M., & Rothman, J. (2024). Modeling individual differences in vocabulary development: A large-scale study on Japanese heritage speakers. Child Development, 96, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B., & Christensen, R. H. B. (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemhöfer, K., & Broersma, M. (2012). Introducing LexTALE: A quick and valid Lexical Test for Advanced Learners of English. Behavior Research Methods, 44(2), 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemmerth, N., & Hopp, H. (2019). Gender processing in simultaneous and successive bilingual children: Cross-linguistic lexical and syntactic influences. Language Acquisition, 26(1), 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew-Williams, C., & Fernald, A. (2007). Young Children Learning Spanish Make Rapid Use of Grammatical Gender in Spoken Word Recognition. Psychological Science, 18(3), 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew-Williams, C., & Fernald, A. (2010). Real-time processing of gender-marked articles by native and non-native Spanish speakers. Journal of Memory and Language, 63(4), 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, E. D., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., & Chaouch-Orozco, A. (2024). Evaluation of the Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) as a quick and practical proxy for language proficiency. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 14(5), 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llombart-Huesca, A., & Zyzik, E. (2019). Linguistic Factors and the Spelling Ability of Spanish Heritage Language Learners. Frontiers in Education, 4, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbeth, A., Atagi, N., Montag, J. L., Bruni, M. R., & Chiarello, C. (2022). Assessing language background and experiences among heritage bilinguals. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 993669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margaretto, B. B., & Brysbaert, M. (2022). How efficient is translation in language testing? Deriving valid Spanish tests from established English tests. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12125115/ (accessed on 26 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Marian, V., Blumenfeld, H. K., & Kaushanskaya, M. (2007). The Language Experience and Proficiency Questionnaire (LEAP-Q): Assessing language profiles in bilinguals and multilinguals. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 50(4), 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maris, E., & Oostenveld, R. (2007). Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG-and MEG-data. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 164(1), 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2016). The Acquisition of heritage languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S., Davidson, J., de la Fuente, I., & Foote, R. (2014). Early language experience facilitates the processing of gender agreement in Spanish heritage speakers. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17(1), 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S., de la Fuente, I., Davidson, J., & Foote, R. (2013). The role of experience in the acquisition and production of diminutives and gender in Spanish: Evidence from L2 learners and heritage speakers. Second Language Research, 29(1), 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S., Foote, R., & Perpiñán, S. (2008). Gender agreement in adult second language learners and Spanish heritage speakers: The effects of age and context of acquisition. Language Learning, 58(3), 503–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, T., Tamura, Y., & Aubrey, S. (2020). Examining the validity of the LexTALE test for Japanese college students. Journal of Asia TEFL, 17(2), 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, O., Çiçek, B., Özal, Z., Gagarina, N., & Sekerina, I. A. (2023). Turkish-German heritage speakers’ predictive use of case: Webcam-based vs. in-lab eye-tracking. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1155585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J. (2023). Sources of individual differences in the dual language development of heritage bilinguals. Journal of Child Language, 50(4), 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Leroux, A. T., Colantoni, L., Thomas, D., & Chen, C. H. Y. (2024). The morphophonological dimensions of Spanish gender marking: NP processing in Spanish bilinguals. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 18, 1442339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2018). Heritage languages and their speakers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portocarrero, J. S., Burright, R. G., & Donovick, P. J. (2007). Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(3), 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prystauka, Y., Hao, J., Cabrera Perez, R., & Rothman, J. (2024). Lexical interference and prediction in sentence processing among Russian heritage speakers: An individual differences approach. Journal of Cultural Cognitive Science, 8, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Mayenco, E., Chaouch-Orozco, A., Liu, H., & Martín-Villena, F. (2023). The LexTALE as a measure of L2 global proficiency. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 13(3), 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Rommers, J., Meyer, A. S., & Huettig, F. (2015). Verbal and nonverbal predictors of language-mediated anticipatory eye movements. Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics, 77(3), 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauzéon, H., Raboutet, C., Rodrigues, J., Langevin, S., Schelstraete, M. A., Feyereisen, P., Hupet, M., & N’Kaoua, B. (2011). Verbal knowledge as a compensation determinant of adult age differences in verbal fluency tasks over time. Journal of Adult Development, 18(3), 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, F., Romoli, J., & Bill, C. (2016). Reluctant acceptance of the literal truth: Eye tracking in the covered box paradigm. Proceedings of Sinn Und Bedeutung, 20, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sekerina, I. A. (2015). Predictions, fast and slow. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 5(4), 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z., Janse, E., Visser, K., & Meyer, A. S. (2014). What do verbal fluency tasks measure? Predictors of verbal fluency performance in older adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanenhaus, M. K., Spivey-Knowlton, M. J., Eberhard, K. M., & Sedivy, J. C. (1995). Integration of visual and linguistic information in spoken language comprehension. Science, 268(5217), 1632–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeiren, H., & Brysbaert, M. (2024). How useful are native language tests for research with advanced second language users? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 27(1), 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyzik, E. (2022). El conocimiento léxico de los hablantes del Español como lengua de herencia. In D. Pascual y Cabo, & J. Torres (Eds.), Aproximaciones al estudio del español como lengua de herencia (pp. 53–65). Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).