Abstract

In the Hispanic world, the analysis of discourse particles from a microdiachronic perspective has emerged as a relatively recent area of research that has already demonstrated its efficacy, particularly in the context of Spain. However, in the case of Mexico, this type of study is still marginal. The objective of this paper is to analyze hacer de cuenta in Mexican Spanish during the 20th and 21st centuries to illustrate its processes of grammaticalization and pragmatization. To this end, a comprehensive analysis of the CREA and CORDE corpora, as well as six corpora of Mexican Spanish, was conducted. This methodological approach was proposed for three reasons. Firstly, it facilitated the acquisition of a diverse sample of examples. Secondly, it ensured the inclusion of corpora from different decades. Thirdly, it obtained examples that approximate orality. The findings suggest that during this period, hacer de cuenta was undergoing a process of pragmatization. Consequently, it can be regarded as a discourse particle that primarily encodes an intersubjective value, through which the speaker attempts to share with the interlocutor the way she/he conceptualizes a particular event.

1. Introduction

In the context of diachronic studies of discursive particles, theoretical concepts such as grammaticalization (Hopper, 1991; Heine, 2002; Heine & Kuteva, 2002; Hopper & Traugott, 2003), subjectivation (Traugott, 1995; Company, 2004; Garachana, 2008; Nikiforidou, 2012), and pragmatization (Garachana, 2008; Mihatsch, 2020) have been utilized to explain the processes undergone by these elements.

Grammaticalization is defined as a gradual process of diachronic (macro)-change that affects all levels of linguistic analysis (Garachana, 2008). Lexical items and constructions become grammatical entities and subsequently evolve to fulfill new grammatical functions over time (Lehmann, 2015). This phenomenon can be conceptualized as an enrichment of grammar, whereby grammatical functions are attributed to forms that were previously devoid of such functions (Kuryłowicz, 1965). Grammaticalization has been described as a universal and recurrent process in the world’s languages (Kiparsky, 1994). This helps to understand the processes by which functional units, such as discourse particles, emerge (Company, 2004; Garachana, 2008; Pons Bordería, 2016; Mihatsch, 2020).

As a process, grammaticalization can be subdivided into four stages (Heine, 2002). Initially, the form manifests its fundamental meaning, though it may possess one or more characteristics that promote its application to additional structures. Alternatively, its meaning may be susceptible to diverse interpretations. In a subsequent stage, the bridging context is introduced, whereby the form exhibits a certain degree of ambiguity, leading the listener to make some inferences or implicatures with respect to the original meaning. Consequently, an inferential mechanism is initiated, whereby the target meaning is presented instead of the source meaning (Heine, 2002; Croft & Cruse, 2008). Therefore, the linguistic form may be associated with different bridging contexts, which in turn may, though not necessarily, promote the emergence of conventionalized grammatical meanings.

In a third stage, the switch context is presented, and a semantic isolation occurs. Thus, the target meaning is now taken to be a meaning per se. At this point, the switch contexts become incompatible with some salient property of the original meaning, and thus a possible interpretation in terms of the source meaning is ruled out. It is noteworthy that the newly established meaning is subsequently demonstrated to be the sole viable interpretation, frequently manifesting in a specific context due to its constrained occurrence.

The final step in this process is conventionalization, which occurs when inferences regarding meaning are made based on frequency of use. These inferences are made in contexts that are not specific to any particular context, and thus, they become “inherent,” “usual,” or “normal.” A method for ascertaining whether a meaning has become conventionalized involves analyzing its capacity to be utilized in novel contexts that differ from those that characterized the bridging and switch contexts. Garachana (2008) has noted that this process frequently culminates in the creation of grammatical elements specialized in expressing the speaker’s opinion. This phenomenon of subjectivization is understood as a diachronic change, signifying the evolution of linguistic expression over time.

Subjectivization is characterized, among other things, by the loss of the referential meaning of the construction in favor of the development of a more subjective meaning. Consequently, it is a process that “lleva desde significados anclados en el mundo sociofísico hasta otros que constituyen una manifestación en el plano textual de la opinión del hablante. Se va así desde lo más externo a los más interno, o lo que es lo mismo, desde lo más objetivo a lo más subjetivo” (Garachana, 2008, p. 18).

As Traugott (1995) has observed, this phenomenon entails an emphasis on linguistic meanings that are more focused on the speaker’s perspective. This process involves a development in which meanings increasingly incorporate the speaker’s perspective, attitudes, and evaluations. Therefore, subjectivization is a crucial aspect of grammaticalization and plays a key role in the generation of discourse markers (Traugott, 1995). This author posits that there exist multiple mechanisms through which subjectivization occurs in grammaticalization, among which are metaphor and metonymy; however, the salient one for the present research is conceptual metaphor.1 This is due to the fact that it facilitates the process by which words with concrete meanings are able to acquire more abstract and subjective meanings. The conceptual metaphor facilitates the comprehension of the cognitive domains presented by the construction hacer de cuenta, which transitions from a material referential plane to one of a notional nature, thereby encoding events in the mental field. In conclusion, as Garachana (2008, p. 31) asserts, “en la subjetivización hay siempre un hablante que no está interesado en hablar del mundo, sino de sus valoraciones a propósito de una determinada realidad.”

In a similar vein, pragmatization (Garachana, 2008; Mihatsch, 2020) is frequently utilized to denote the series of changes that a linguistic element undergoes, resulting in the acquisition of specific pragmatic functions. Pragmatization has also been defined as a (sub)-type of grammaticalization that is often present in both discourse markers and discourse particles (Camargo & Grimalt, 2022) and reflects their proceduralization (Escandell Vidal, 2017). Among the changes identified in pragmatization, Garachana (2008, p. 30) has pointed out six key ones: (i) loss of referential meaning, (ii) inferential process (metonymic or metaphoric), (iii) loss of agentive control of the subject, (iv) extension of the predicative scope, (v) fixation and autonomy of the predication, and (vi) reduction in or loss of syntactic capacities.

On the other hand, the relevance of incorporating data from the 20th and 21st centuries in the micro-diachronic study of discourse particles has recently been emphasized (Pons Bordería, 2014; Pons Bordería & Salameh, 2024). This emphasis is largely attributable to the fact that this type of data can provide arguments to explain the formal and functional changes that have occurred during these centuries. This new methodology for micro-diachronic analysis has demonstrated its reliability in various studies (e.g., Pons Bordería, 2016; Llopis & Pons Bordería, 2020; Mihatsch, 2020; Camargo & Grimalt, 2022). However, in the context of Mexican Spanish, there is a significant gap in research in this area, especially when compared to the state of the art in Spain, for instance.

In this scenario, the objective of this study is to demonstrate the pragmatization of hacer de cuenta through the characterization of the morphological, syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic processes that this construction has undergone. The analysis of data from the 20th and 21st centuries will serve as the basis for this study.

The initial hypothesis asserts that, over the course of these two centuries, hacer de cuenta underwent significant changes in morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, thereby contributing to its development as a discourse particle. These changes can be observed in its recently acquired functions, including introducer of hypothetical discursive contexts (1) and exemplification (2) (De Mello, 1994; Guillén, 2022; Uribe, 2024):

- 98 I: se me hizo fácil/para fines del mes de enero mana me fui con él/así de rápido/haz de cuenta que en un mes lo conocí/empezamos a salir/y yo agarré y me fui con él. CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.98 I: I didn’t think it through/by the end of January mana I went with him/just like that/imagine that in a month I met him/we started dating/and I went with him.

- 84 I: [mejor] me iba/lo que sacaba en la semana lo/haz de cuenta que ganaba/por decir tres mil pesos/agarra-/agarraba dos mil y invertía mil pesos. CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.84 I: what I earned in the week/suppose that I earned/to say three thousand pesos/I took two thousand and invested one thousand pesos. CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.

For example, in Example (1), I is talking about how she made the decision to run away with her partner very soon and with haz de cuenta que (imagine that) shares a hypothetical context with her interlocutor: en un mes lo conocí, empezamos a salir y me fui con él (in a month I met him, we started dating, and I went with him). On the other hand, in Example (2), I comments that he always had the habit of saving, and with haz de cuenta que (suppose that) presents an example of how he did it: ganaba tres mil pesos, agarraba dos mil y invertía mil pesos (I earned three thousand pesos, I took two thousand and invested one thousand pesos).

As we will try to prove, hacer de cuenta is currently undergoing a process of pragmatization due to its structure being fixed in the second person singular of the imperative mood. Additionally, it has undergone syntactic impoverishment (Garachana, 2008), which has enabled it to acquire greater independence and mobility within the discourse units.

For this purpose, and in accordance with Foolen’s (2011) criterion of exhaustiveness, the following corpora of Mexican Spanish were consulted: the two volumes of the Corpus del español mexicano contemporáneo (UNAM, 2012; El Colegio de México, 2022), El habla de la ciudad de México (Lope Blanch, 1971), El habla popular de la ciudad de México (Lope Blanch, 1976), the Corpus Sociolingüístico de la Ciudad de México (Martín Butragueño & Lastra, 2011, 2012, 2015), and the Mexican cities in the corpus of Proyecto para el estudio sociolingüístico del español de España y América (PRESEEA, 2014): Guadalajara, Mexicali, Monterrey, and Puebla, and in Ameresco (Albelda & Estellés, n.d.): Mexico City, Monterrey, and Queretaro. Finally, the CREA (Real Academia Española, n.d.a) and CORDE (Real Academia Española, n.d.b) corpora were also consulted.

2. Materials and Methods

As a starting point, this paper adopts the principle of exhaustiveness proposed by Foolen for the analysis of pragmatic markers:

The minimal methodological requirement in present-day research is that an analysis of a PM [pragmatic marker] in a specific language is based on a substantial set of “real” uses of the marker, whereby not only isolated utterances but also their context is taken into consideration. Better still is the exhaustive analysis of a corpus, in which all occurrences of a PM are accounted for.(Foolen, 2011, p. 221)

For this reason, it was decided to incorporate as many corpora as possible from the 20th and 21st centuries of Mexican Spanish. This, in turn, allowed us to solve one of the methodological problems of the micro-diachronic analysis of discourse particles: the lack of data from colloquial oral contexts (Garachana, 2008; Pons Bordería, 2014; Mihatsch, 2020). Hereafter, the corpora included in this research are presented.

The first volume of the Corpus del español mexicano contemporáneo (CEMC-I, UNAM, 2012) covers the period from 1921 to 1974 and is made up of 996 written and oral records by Mexican authors or recorded conversations from the linguistic–ethnographic collection of El Colegio de México. The second volume (CEMC-II, El Colegio de México, 2022) is also composed of 996 written and oral texts, but from 1975 to 2018. Although the purpose of these volumes was “reunir muestras que sean representativas de los usos de la lengua en México, orientadas, sobre todo, a documentar vocabulario, tanto del más reciente, como del más tradicional” (UNAM, 2012), we argue that their inclusion can provide clues about the use of hacer de cuenta during these years, especially since the examples provide sufficient context to carry out such an analysis.

The Norma culta corpus (Lope Blanch, 1971) consists of 56 samples. In 31 of these samples there is more than one informant, which at times results in the interviewer not participating and, therefore, not leading the interview. In these interviews, relatives are usually involved in the recording, which means that the participants share a close experiential relationship, and topics from everyday life are addressed (Briz, 2010).

The Habla popular corpus (Lope Blanch, 1976) consists of 34 samples, 12 of which have more than one informant, which means less participation by the interviewer. In addition, the interviewees are usually co-workers or friends, so there is a relationship of equality, an experiential relationship of proximity, a lower degree of planning, and a greater thematic everydayness (Briz, 2010). Also, several interviews were recorded without the knowledge of the participants. To sum up, some of the samples from these two corpora are closer to colloquial oral contexts, mainly because certain features of colloquialism are noticeable in them (Briz, 2010), the most obvious being +relation of social equality, +experiential relation of proximity, +thematic everydayness, +/−higher degree of planning, and +interpersonal purpose.

The Corpus Sociolingüístico de la Ciudad de México (CSCM, Martín Butragueño & Lastra, 2011, 2012, 2015) was collected between 1997 and 2005. It consists of 108 interviews grouped into three educational levels: high (at least 16 years of schooling), middle (up to 12 years of schooling), and low (up to 6 years of schooling). These groups are also divided into three generational groups: young people (20–34 years of age), adult (35–54 years of age), and older (55 years of age and over). Finally, the informants are divided equally into women and men. Despite the fact that these are sociolinguistic interviews, the authors argue that in some cases, during the interview, the characteristics of the exchange are close to those of a conversation, so it could be the ideal context for the emergence of hacer de cuenta.

The corpora of the Mexican cities present in PRESEEA (2014) are also included: Guadalajara, Mexicali, Monterrey, and Puebla. As members of this project, these corpora follow specific sociolinguistic criteria, such as stratification by age, educational level, and sex. Like the CSCM, the interviews sometimes show some features of conversation. Finally, these materials were collected between 2006 and 2016 and show the behavior of hacer de cuenta during the first decades of the 21st century.

We also consider the conversations from the Mexican cities included in the Corpus Ameresco (Albelda & Estellés, n.d.): Mexico City, Monterrey, and Queretaro. Due to their characteristics, these conversations are colloquial (Briz, 2010) and reflect a register different from all the other corpora. Thus, they are shown to be the ideal context for the occurrence of hacer de cuenta. These conversations were collected between 2015 and 2022.

Therefore, the corpora, although with different registers and characteristics, reflect a period that runs mainly from 1921 to 2022. We assume that, in this way, we have enough examples to be able to explain the formal and functional changes that hacer de cuenta underwent during this period.

Finally, although they are not exclusively from Mexican Spanish, the Corpus de Referencia del español actual (CREA) (Real Academia Española, n.d.a) and the Corpus Diacrónico del Español (CORDE) (Real Academia Española, n.d.b) were also consulted.

On the other hand, with regard to the written texts in the Corpus del español mexicano contemporáneo, it was decided to include them in view of what some authors (López Serena, 2007; Garachana, 2008; Mihatsch, 2020) have said about the fact that it is common in literature to imitate orality.

Once the corpus was integrated, each one was manually reviewed. In most cases, this task was made possible thanks to the search tools and criteria available for each corpus. For example, in the case of the Pan-Hispanic corpora (PRESEEA, 2014; Ameresco, Albelda & Estellés, n.d.), the “city” filter was very useful to restrict the search to the cities of Mexico. However, in the case of the corpora coordinated by Lope Blanch (1971, 1976), which do not have specific search tools, it was necessary to go through all the samples to identify the occurrences of hacer de cuenta.

It should be noted that several examples were eliminated because they were included in the volumes of the Corpus del español mexicano contemporáneo, but they originally belonged to the corpora coordinated by Lope Blanch or the CSCM.

Finally, the analysis considers the study of morphological (verbal inflection), syntactic (position within the utterance, element it introduces, its function as a predicative head), semantic (lexical equivalence), and pragmatic (type of modality, functions as a discursive particle) variables.

3. Results

The data show several important trends. Firstly, there is an exponential increase in the use of hacer de cuenta in the 20th century (n = 180, 26.7%) and particularly in the 21st century (n = 488, 72.3%). In contrast, only seven instances (1%) were documented in the 19th century. This radical change may be related, in part, to the type of corpus consulted, which is closer to colloquial orality. As has been previously noted in other works (Garachana, 2008), the incorporation of oral corpora from the 20th and 21st centuries leads to a substantial increase in the occurrence of discourse particles typical of this register.

Another aspect that was revealed is the presence of hacer de cuenta almost exclusively in the varieties of American Spanish,2 as shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Distribution of hacer de cuenta in the varieties of Spanish.

The following analysis offers both qualitative and quantitative descriptions of hacer de cuenta. For the purpose of presentation, the data have been organized according to the variables of each language level in which they occur. Initially, morphological characteristics of the construction are explored to demonstrate the degree of fixation of its constituents. Second, syntactic behavior is described to verify the progressive loss of its syntactic functions in favor of the gain of pragmatic and functional properties. Thirdly, semantic behavior of the construction is presented to demonstrate the different meanings that it acquired in its process of evolution. Finally, pragmatic–discursive behavior is detailed to show the modal and discourse properties that have been acquired.

It is important to note that, although the study focuses on data from the 20th and 21st centuries, cases from the 19th century are included to contextualize the developments that occurred in these two centuries.

3.1. Morphological Characteristics

In the course of grammaticalization, a formal erosion occurs. This phenomenon is characterized by the loss or simplification of the formal characteristics of the original word. Consequently, a process of demorphologization happens, characterized by the tendency of words to adopt invariable forms. As result, the new grammatical forms that emerge from the process of grammaticalization tend to behave as closed grammatical particles, without inflection of gender, number, or person.

A morphosyntactic reanalysis is also often presented, in which the existing structure is reinterpreted under a new functional configuration. In this reanalysis, what was originally a lexical construction can become a grammatical unit. These modifications are indicative of the progressive loss of lexical autonomy of the original forms and their subsequent integration as functional elements within the grammar of the language.

In the case of hacer de cuenta, it is a construction with a light verb; that is, it has a verbal head that encodes morphological information and a prepositional phrase (PP) that provides the lexical meaning, as shown in Example (3). However, over time, the morphological variation of the predicative head becomes less prevalent, and there is a tendency for it to appear in the imperative mood in second person singular, as illustrated in Example (4):

- 3.

- ¿No es cierto que es una locura, cuando mañana podemos pasar horas enteras juntos, donde no tengamos que temer, en casa, donde haremos de cuenta que no estamos en París y respiraremos en el invernáculo el olor de nuestros bosques? CORDE, Colombia. 19th century.Is it not true that it is madness, when tomorrow we can spend whole hours together, where we do not have to be afraid, at home, where we will suppose that we are not in Paris and breathe in the greenhouse the smell of our forests?

- 4.

- Tu tío no más vio que entraban por los equipajes y haz de cuenta que le nacieron alas en los pies –respondió Conchita. CREA, Mexico. 20th century.Your uncle just saw them coming in through the luggage and imagine that he had wings on his feet –he answered.

This trend is evident when examining the fact that the imperative concentrates the vast majority of the compiled cases (n = 554, 82%). This verbal mode exhibits a significant diachronic progression, with only two cases in the 19th century (0.36%), 114 cases in the 20th century (20.58%), and 438 cases in the 21st century (79.49%). This finding suggests a marked preference for direct exhortative constructions, which are associated with a more colloquial style, where direct appeal to the interlocutor is privileged. This phenomenon points out an expansion in and consolidation of the construction over time, indicating a recent vitality and its potential incorporation into the grammatical system of contemporary Mexican Spanish.3

On the other hand, the subjunctive with an exhortative or jussive value also appears as a relevant form, although to a lesser extent. A total of 95 cases have been documented, which are distributed as follows: 19th century (n = 2, 2.11%), 20th century (n = 45, 47.37%), and 21st century (n = 48, 50.53%). This regularity suggests that the subjunctive has maintained a constant presence as a strategy of indirect or more attenuated exhortation, in contrast to the immediacy of the imperative. Within this category, second person singular stands out again, representing 83 of the 95 cases of the subjunctive.

In contrast, the indicative mood has only 21 occurrences in the whole corpus. Most of them are concentrated in the 20th century (n = 16, 76.19%), while in the 21st century their frequency drops notably (n = 2, 9.52%). Furthermore, the subtypes of grammatical person within the indicative mood (such as first person and second person in the singular and plural) are poorly represented, which reinforces the idea that their role has been, in general terms, marginal and fleeting.

Finally, it is noteworthy that non-personal forms of the verb are present in low numbers. These include the infinitive (n = 5), the gerund (n = 1), and the nominal forms (n = 4). These are only documented in the 20th century. This low frequency, coupled with their apparent disappearance in the 21st century, suggests that these forms have not played a significant or sustained role in the observed grammatical change.

Therefore, the cases in which hacer de cuenta appears in second person singular imperative offer clear evidence of its evolution. A total of 538 cases (79.70%) have been documented, with none occurring during the 19th century, suggesting that exhortative use was not yet widespread or conventionalized. An alternative explanation may be the fact that, in historical corpora, second person forms tend to be less frequent, mainly because the type of text they include does not promote the appearance of these forms.4

Conversely, a substantial increase is observed in the 20th century (n = 105, 19.52%), signifying the initiation of the grammaticalization process. This process intensifies during the 21st century (n = 433, 80.48%). The findings indicate the emergence of the second person singular imperative as a predominant form of exhortation or instruction. Additionally, it suggests the evolution of hacer de cuenta to a well-established form of verbal exhortation or instruction, in which the speaker addresses the interlocutor directly so that the latter imagines, simulates, or pretends a situation.

The absence of this phenomenon in the 19th century, followed by its emergence in the 21st century, suggests a discernible trajectory of grammaticalization. This trajectory entails the evolution of an expression from its initial state as a compound and semantically transparent entity to its subsequent grammaticalization and pragmatically marked function. The result of this process is a fixed form that is subject to almost automated interpretation.

In summary, the morphological properties indicate that hacer de cuenta has undergone a process of formal reduction and functional fixation, oriented towards exhortative uses. While morphologically diverse uses coexisted in the 19th and 20th centuries, in the 21st century an imperative form addressed to the second person singular has become dominant. This suggests that we are dealing with a case of morphological and pragmatic specialization in current Mexican Spanish.

3.2. Syntactic Characteristics

Grammaticalization involves a process of syntactic change characterized by the loss of autonomy of the construction, the increase in cohesion between its components, the fixing of the order, the restructuring of its function within the sentence, and, in some cases, phonetic reduction or morphological erosion.

As demonstrated in Examples (5) through (7), hacer de cuenta undergoes a transformation from a full predicative head governing a subordinated noun sentence to gaining syntactic independence and appearing in a variety of contexts as an independent unit with a high degree of mobility.

- 5.

- Haga de cuenta que estoy enfermo y desahuciao. ¡Vaya! ¡Ta hecho! Si no es así será de otro modo. Matarse y matar son dos cosas que nadie le priva a un hombre resuelto. Tenga paciencia. CREA, Uruguay, 20th century.Suppose that I’m sick and evicted. Wow! It’s a done deal! If not, it will be otherwise. To kill oneself and to kill are two things that no one deprives a resolute man. Be patient.

- 6.

- No, pus, eso ya es parte, eso ya es aparte. De eso pus yo hago de cuenta que no tengo nada; tengo no más lo que trabajo de aquí. CEMC-I, Mexico, 20th century.No, that’s part of it, that’s separate. I imagine that I don’t have anything; I only have what I earn here.

- 7.

- 372 I: desde desde mmm/Reino Aventura para <~pa> arriba/haz de cuenta. CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.372 I: from from mmm/Reino Aventura to up/picture.

In Example (5), haga de cuenta (suppose that) is in initial position of intervention, while in Example (6), hago de cuenta (I imagine that) appears within the utterance. In both cases, the construction cannot be omitted because the resulting syntactic structure would be agrammatical. In contrast, in Example (7), haz de cuenta (picture) appears in the final position of intervention. Due to the absence of the conjunction que, it can be deleted, and the syntactic structure remains grammatical.

A diachronic analysis of its position within the discursive unit reveals significant changes over time. In the 19th century, the available data are scarce, which suggests limited use or less fixation of the construction in specific positions. In contrast, in the 20th and 21st centuries, there has been a marked increase in its frequency, accompanied by a tendency towards greater stability in its placement within the utterance, as evidenced in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Position of hacer de cuenta.

A salient change is observed in the final position of the utterance. In the 20th century, it represented 28% of the registered cases (n = 7), while in the 21st century the proportion rises to 72% (n = 18). This indicates a progressive consolidation of this position in contemporary discourse. This phenomenon may be attributed, at least in part, to an increased degree of pragmatic autonomy of hacer de cuenta.

On the other hand, the occurrence of hacer de cuenta in the initial position of intervention is extremely rare. A single instance has been documented in the 20th century, and no examples have been reported in the 21st century in this position. This observation suggests that the construction rarely occupies an absolute initial position in discourse.

An examination of the initial position of the act reveals an interesting evolution. In the 19th century, only 4.40% (n = 4) of cases corresponded to this position, while in the 20th century the percentage increased to 32.97% (n = 30), reaching 62.64% (n = 57) in the 21st century. This growth suggests that the construction has gained stability at the beginning of discourse sequences, possibly due to its use as a particle that introduces fictitious situations or hypothetical scenarios.

A pronounced trend is evident in the middle position of act. In the 19th century, this position represented a mere 0.19% (n = 1) of the registered cases. However, in the 20th century, this percentage increased to 23.09% (n = 121), and in the 21st century, it reached a significant 76.72% (n = 402). This consolidation suggests that the construction has been firmly established in this position in modern discourse, which may be related to its integration into more complex structures and its function as a marker of a specific discourse relationship.

Now, from the perspective of its syntactic functions, a gradual process of functional diversification can be seen, following a typical trajectory of grammaticalization. Table 3 shows the distribution between two main uses: as a discursive particle and as a predicative head.

Table 3.

Distribution of hacer de cuenta according to its function.

In Example (8), an example is provided to illustrate the use of hacer de cuenta as a predicative head:

- 8.

- MTY_054_03_15_A: y haz de cuenta que le pidió permiso a su mamá y todo/pero/ella/tenía más o menos/unos/dieciocho años///(1) y se fue//pero sin ser experta ni en nada ni en nada. AMERESCO-MTY, 21st century.MTY_054_03_15_A: and imagine that she asked her mother for permission and everything//but/she/was more or less/about/eighteen years old////(1) and left//but without being an expert in anything or anything.

In this case, the construction establishes syntactic relations with another constituent; that is to say, it requires a subordinated noun sentence in the role of direct object to complete its meaning. From a syntactic perspective, this construction is non-elidable and cannot be moved without altering the grammaticality or the meaning of the utterance.

In contrast, there are other cases where the construction presents greater syntactic autonomy:

- 9.

- 286 I: ese ba- baja de las montañas que ahí están cerca/hay unas montañas muy altas muy grandes/haz de cuenta como el Popocatépetl. CSCM, Mexico, 21st century.286 I: that co- come down from the mountains that are close by/there are some very high mountains/suppose like the Popocatepetl.

In the previous example, haz de cuenta can be omitted or moved without altering the grammaticality or meaning of the utterance. It no longer requires an argument to complete its meaning. In analogous cases, the construction functions as a discourse particle.

As can be seen in Table 3, in the 19th century, hacer de cuenta was used exclusively as a predicative head, generally with an assertive or modal value within sentence structures. Its process of grammaticalization had not begun or was still in its early stages.

During the 20th century, a significant change occurred. The proportion of uses as a discourse particle increased to 37.78% (n = 68), while 62.22% (n = 112) of the occurrences still corresponded to the predicative head. These data suggest that the construction is beginning to acquire more abstract and discursive functions, which could reflect a syntactic reanalysis by the speakers.

In the 21st century, the trend towards functional diversification persists, albeit without a substantial percentage increase. The analysis reveals that the utilization of hacer de cuenta as a discourse particle represents 36.07% (n = 176 cases), while as a predicative head it continues to be in the majority, with 63.93% (n = 312 cases). While the percentages remain relatively stable compared to the previous century, the absolute growth of the data indicates a consolidation of both functions in the contemporary Mexican Spanish repertoire.

The overall data confirm this functional duality: of the 675 cases analyzed, 36.15% correspond to use as a discourse particle and 63.85% to use as a predicative head. This distribution suggests that, while the construction maintains its value as a predicative head, it has expanded its functional scope to encompass discourse roles that traditionally correspond to markers of attitude, modality, or evidence.

When considered as a whole, these data demonstrate a process of partial grammaticalization. Hacer de cuenta has transitioned from a strictly syntactic–semantic use as a full predicate to a pragmatic–discursive function, without fully abandoning its original function. This multifaceted behavior is a hallmark of expressions undergoing grammaticalization, which coexist for an extended period in both the syntactic and pragmatic domains before ultimately settling definitively in one domain or giving rise to diversified variants.

With regard to the internal syntactic structure, the analysis of the data reveals a clear tendency towards the fixation of certain syntactic structures, as well as a process of standardization of the way in which the propositional content associated with this construction is expressed. This tendency is illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Type of structure and propositional content.

In the 19th century, data are limited, but some relevant patterns have been identified. A single instance of a bare singular noun (without determiners or modifiers) is documented, constituting 14.29% of this subtype. Additionally, six cases (0.90% of the aggregate total) are observed, wherein the nominal constituent assumes the form of a PP introduced by de (of) followed by a singular noun phrase (NP). The absence of any documented use of a determiner followed by a singular NP suggests that this form had not yet become conventionalized at the time.

In the 20th century, we observe a notable change. The use of the PP with de (of) followed by a singular noun becomes the dominant pattern, with 172 occurrences representing 25.83% of the overall total. In addition, there are two cases (100% of this subtype) in which a determiner is introduced before the noun, which suggests greater flexibility in the structure of the nominal complement and a possible expansion towards more marked forms. The use of the bare noun also persists, with six cases constituting 85.71% of the occurrences recorded for this subtype.

In the 21st century, the usage pattern is further consolidated. The PP with de (of) + singular NP has emerged as the predominant form, comprising 488 cases, which account for 73.27% of the overall total. This overwhelming majority points to a robust structural fixation that may be linked to the grammaticalization of the construction. The complement of the NP adopts a highly conventionalized form, potentially semi-semantic, while the content of the NP begins to lose lexical variability and is oriented towards more abstract meanings or stereotypical interpretations.

In contrast, there are no cases of bare nouns, which could indicate a loss of productivity of this form because it is less clear or less suitable for functioning within a more grammaticalized discursive framework.

Finally, with regard to the form with determiner + singular NP, it is surprising that no cases have been documented in the 21st century. This observation suggests that, despite its marginal presence in the 20th century, this structure did not manage to consolidate itself as a productive linguistic pattern.

Therefore, the data demonstrate a discernible process of structural fixation in the nominal complement that follows hacer de cuenta, where the most grammaticalized form—the PP introduced by de (of)—has nearly completely displaced the other variants. This phenomenon aligns with grammaticalization processes, wherein increased syntactic fixation and a reduction in structural variability accompany the transition in the functional status of the construction within the linguistic system.

3.3. Semantic Characteristics

During grammaticalization, a generalization of meaning is observed in which the linguistic unit abandons its specific lexical sense and begins to embody broader or more diffuse semantic values. This tendency is accompanied, in many cases, by an increase in subjectivity or intersubjectivity in the use of grammaticalized forms (Traugott, 1995). That is to say, there is a greater involvement of the speaker in the utterance, whether through judgments, attitudes, or modulations of epistemic commitment.

From a semantic perspective, grammaticalization involves a reconfiguration of meaning. That is to say, the word or construction ceases to function as a carrier of referential meaning and takes on a functional or structural role within the discourse. This transition does not entail the complete loss of the original meaning; rather, it signifies a gradual reduction in its lexical load, which is now subject to the novel grammatical or pragmatic functions attributed to the form during the process of grammaticalization.

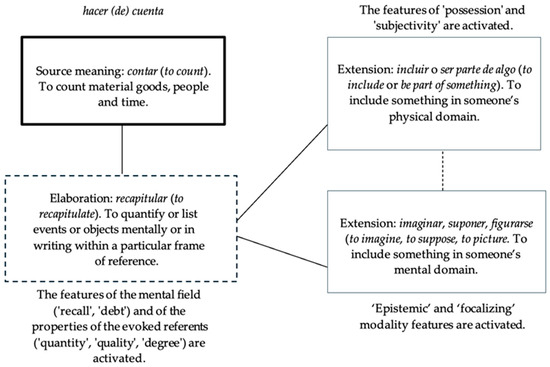

The construction hacer de cuenta underwent numerous semantic shifts over time. Consequently, its meaning transitioned from its historical association with the enumeration of tangible entities to its more abstract connotations, as illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Semantic network of hacer de cuenta.

Figure 1 shows the process of semantic change that the construction hacer de cuenta has undergone. The base meaning refers to the material and physical cognitive domain, related to the action of counting. In a first stage, the construction transits from this material domain to an abstract one; it no longer lists objects, but now mentally recapitulates a series of elements or the steps of a process, so that it has a meaning equivalent to recapitulate, so that a semantic elaboration is presented—that is, new features are incorporated to the original meaning. Subsequently, two extensions emerge: one equivalent to incluir (to include) or ser parte de (to be part of) and another one that refers to events of the mental field, equivalent to suponer (to suppose), imaginar (to imagine), or figurarse (to picture), depending on the degree of specificity of the focused referent.5 In the equivalent to incluir (to include) or ser parte de (to be part of), the quantification of the referents is no longer emphasized, but rather it is emphasized to whom the property of these objects is attributed. On the other hand, the semantic extension that encodes events of the mental field (such as suppose, imagine, or picture) leaves aside the notion of quantification and highlights the properties of the referents focused by the construction. By referring to mental events, this elaboration activates epistemic and intersubjective modal features that were not present in the original meaning.

Thus, the data in the corpus show different meanings that are encoded through different syntactic structures, as can be seen in the following examples:

When expressing the meaning of contar (to count):

- 10.

- Quince. Son orita de nietos, de los de mis hijas orita ya están: dos… Tres de mi hijo, y tres… Cuatro de mi hija, haga usté la cuenta. Cuatro de mi hija… Y tres de mi hijo. Siete; ésos son los que tengo allá a mi lado. CEMC-I, Mexico, 20th century.Fifteen. Now I have fifteen grandchildren, my daughter has two already… My son has three, and three… four more of another daughter, do the math. Four grandchildren of my daughter… and three more of my son. Seven, those are grandchildren that I have there, close to me.

When it expresses the meaning of recapitular (to recapitulate):

- 11.

- le diré que vuelva mañana. >Emilio se alarmó mostrándose muy preocupado. < e-Laurita, por favor no me hagas eso, por si lo ignoras vivo en Azcapotzalco y para llegar a la oficina hago más de una hora. Haz cuenta del tiempo que necesito para llenar el informe que debo poner en manos del señor Reina mañana sin falta. CEMC-I, Mexico, 20th century.I will tell him to come back tomorrow. >Emilio was alarmed and very worried. < e-Laurita, please don’t do that to me, in case you don’t know, I live in Azcapotzalco, and it takes me more than an hour to get to the office. Do count the time I need to fill out the report that I must put in the hands of Mr. Reina tomorrow without fail.

By the 20th century, a divergence in meaning had emerged among the constructions hacer cuenta, hacer la cuenta, and hacer de cuenta. Consequently, hacer de cuenta has lost its etymological meaning and now only encodes meanings related to events in the mental realm.

When the speaker introduces a hypothetical situation, the construction has the value of suponer (to suppose):

- 12.

- 91 I: pues <~ps> de repente/o sea/a veces haz de cuenta que/hoy por ejemplo/viene gente pero a comprar plantas/flores/normales/¿no?/CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.91 I: well/all of a sudden/I mean/sometimes suppose that/today for example/people come to buy plants/flowers/regular/right?

When a speaker describes a scene to their interlocutor in such a manner as to express their point of view on a given situation, hacer de cuenta assumes the value of imaginar (to imagine):

- 13.

- 510 I: mh/y entonces haz de cuenta luego me dice/”es que/vamos a comprar una televisión”/le digo “ay/no/está muy bien la que tenemos ahorita”/y dice este/porque ya conozco su “vamos a comprar” CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.510 I: mh/and then imagine he says/”we are going to buy a television”/I say “oh/no/the one we have right now is fine”/and he says this/because I know what his “we are going to buy” really means.

Finally, when the speaker wishes to focus a specific referent to illustrate or situate a particular element of what said, the construction assumes the function of figurarse (to picture):

- 14.

- E: pero para eso necesitas/trabajar un chingo y juntar feria y no andar/<simultáneo> metiéndote cosas ¿no? </simultáneo>I: <simultáneo> ¡ándale!/sí </simultáneo>/para eso haz de cuenta/necesito jalar/y juntar una feriecita y acoplarme tú y ella/y/sí/comprar haz de cuenta/un traspasillo en las colonias/en las <vacilación/>/en la Fome cuarenta y cinco o en San Ángel. PRESEEA-MTY, Mexico, 21st century.E: but for that you need to/work a lot and save money and not be/<simultaneous> putting things in your body, right? </simultaneous>I: <simultaneous> precisely!/yes </simultaneous>/for that picture/I need to work very hard/and save a feriecita and couple you and her/and/yes/buy/a transfer in the neighborhoods/in the <hesitation/>/in the Fome forty-five or in San Angel.

The diachronic analysis of the lexical equivalences associated with hacer de cuenta reveals a significant process of semantic transformation over time. Table 5 demonstrates how, from the 19th to the 21st century, this construction has been reinterpreted or paraphrased through various verbal forms, thereby enabling us to infer its semantic value in specific contexts. The forms contar (to count), imaginar (to imagine), recapitular (to recapitulate), figurarse (to picture), and suponer (to suppose) reveal not only the diversity of meanings attributed to hacer de cuenta but also its progressive specialization and semantic abstraction.

Table 5.

Lexical equivalents of hacer de cuenta through the centuries.

During the 19th century, the construction was predominantly interpreted as synonymous with suponer (to suppose), accounting for 71.43% (n = 5) of the observed cases during this period. To a lesser extent, it appears as equivalent to imaginar (to imagine), with 28.57% (n = 2). This distribution indicates that, at this early stage, hacer de cuenta retained a relatively complete meaning, linked to mental processes of simulation or hypothesis, which is consistent with its not yet fully grammaticalized character.

In the 20th century, the spectrum of equivalences underwent significant expansion. The most prevalent equivalence is still suponer (to suppose), accounting for 44.44% of the data (n = 80). However, it exhibits a decline in relative frequency compared to novel forms such as imaginar (to imagine) (31.67%, n = 57) and figurarse (to picture) (21.67%, n = 39%). This lexical diversification can be interpreted as a sign of semantic transition, indicating that the construction began to be used in contexts where simulated mental activity predominates. However, it can also be understood as an expression of a change in perspective or a fictitious internal representation, elements that pave the way for more abstract and subjective uses. Marginal occurrences of equivalents such as contar (to count) and recapitular (to recapitulate), with a frequency of 1.11%, are also noteworthy. This behavior suggests specific, less conventional applications or discourse reinterpretations of the expression.

In the 21st century, there is a marked consolidation of the equivalences to imaginar (to imagine) (42.83%, n = 209) and suponer (to suppose) (39.14%, n = 191), which together represent more than 80% of the cases. This consolidation indicates a semantic stabilization around values associated with cognitive processes such as mental simulation and conjecture. Likewise, the equivalence with figurarse (to picture) (18.03%, n = 88) is strengthened, while the marginal equivalences with contar (to count) and recapitular (to recapitulate) disappear. This pattern suggests that hacer de cuenta has reached a predominantly subjective and abstract interpretation, which is consistent with its increasing grammaticalization as a discourse particle in contemporary contexts.

An analysis of this variable reveals a clear trajectory: from fuller and more referential lexical meanings in the 19th century to more abstract, mentalized, and subjective interpretations in the 20th and 21st centuries. This evolution mirrors a semantic transformation consistent with grammaticalization processes, wherein concrete meaning is eroded in favor of more general discourse functions.

On the other hand, the analysis that combines the lexical equivalences of hacer de cuenta with its syntactic functions (discourse particle or predicative head) throughout the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries allows us to clearly observe the process of grammaticalization that this construction has undergone. This evolution is evident not only in the shift in its semantic values but also in the displacement of its functions within the structure of the utterance, as illustrated below.

In the 21st century, this trend has been consolidated: 36.07% of occurrences of the construction operate as a discourse particle, while 63.93% still maintain a predicative function. It is noteworthy that, although the aggregate proportion of discourse particles remains relatively stable compared to the previous century, a substantial redistribution has occurred in terms of lexical equivalences. For instance, in the equivalent uses of figurarse (to picture), the proportion of discourse particles remains substantial (68.18%, n = 60), thereby validating the assertion that this lexical form persists in its function as a bridge to grammaticalization. In the cases equivalent to imaginar (to imagine) and suponer (to suppose), although predicative functions still dominate (69.38% and 72.77%, respectively), there is a relative increase in discursive uses compared to the 20th century.

When considered as a whole, these data lead us to affirm that hacer de cuenta has moved from a lexical and predicative use to a discourse and grammaticalized position, especially through its equivalences with verbs such as figurarse (to picture), which show a greater tendency to subjectivization and to mark the speaker’s point of view. The simultaneous presence of predicative and discourse functions suggests that the grammaticalization process is advanced, albeit not yet complete.

The distribution of data according to the syntagmatic position in which the construction appears and its lexical equivalence is indicative of a close relationship between its lexical equivalences (e.g., imaginar (to imagine), suponer (to suppose), figurarse (to picture), contar (to count), and recapitular (to recapitulate)) and the different syntagmatic positions it occupies within the sentence (final position, initial position of utterance or act, middle of utterance/initial position of act, middle of utterance/middle of act). This two-fold dimension of the analysis is particularly relevant for understanding not only the changes in the meaning and use of the construction but also its functionalization within the discourse. The most significant results are presented below in Table 6.

Table 6.

Relation between position and lexical equivalence.

During the 19th century, construction appears to have mainly predicative functions and is located mostly in initial positions of the utterance or communicative act (57.14%), suggesting a use still linked to its full value as a lexicalized verb. The equivalences documented in this century—to imagine and to suppose—demonstrate analogous patterns: imaginar (to imagine) occurs exclusively in the initial position (100%), while suponer (to suppose) exhibits a more varied distribution, also appearing in middle positions (40% in middle/initial of act; 20% in middle/middle of act), which anticipates an imminent shift towards syntagmatic zones that are less prototypical for a full verb.

In the 20th century, a significant redistribution of construction can be observed, with constructions occupying internal positions in the utterance more frequently—in particular, the middle of the utterance/middle of the act (67.22% of the total). This position is compatible with pragmatic or discourse functions, and its increase is indicative of a process of functional readjustment. Lexical equivalences confirm this trend. For example, figurarse and suponer have high percentages in this position (71.79% and 73.75%, respectively), while imaginar still retains a certain distribution in initial positions (22.81%). These data suggest that certain lexical equivalences favor the transition to discourse functions more than others and, with this, the movement towards middle syntagmatic positions, traditionally associated with parenthetical elements or discursive particles.

In the 21st century, this tendency has become increasingly pronounced. Hacer de cuenta is used in 82.38% of cases where it is positioned in the middle of the utterance or act, indicating its consolidation as a pragmatic unit with reduced dependence on a predicative structure. The equivalences with imaginar (to imagine) and suponer (to suppose) show behaviors consistent with this interpretation: imaginar (to imagine) occurs almost exclusively in this position (89.47%), and suponer (to suppose) in 83.25%. Conversely, figurarse (to picture) exhibits a higher frequency in the final position (17.05%) and the initial position (11.36%), although it also appears predominantly in the middle position (63.64%). This observation suggests potential for more flexible usage or an intermediate phase in its pragmatic evolution.

Another salient aspect pertains to the relationship between the various lexical equivalences that the construction may possess and the processes of semantic change it underwent over the course of centuries. The analysis enables the observation of a progressive transition from a literal or original meaning towards more abstract, inferential, or markedly pragmatic forms. Table 7 illustrates how, over time, this construction undergoes processes of elaboration and semantic extension, which are characteristic of the phenomenon of semantic grammaticalization. These processes are articulated with the emergence of different lexical equivalences, such as contar (to count), figurarse (to picture), imaginar (to imagine), recapitular (to recapitulate), and suponer (to suppose), in different centuries.

Table 7.

Lexical equivalences through centuries.

In the 19th century, the construction has a marginal presence of 1.04% (n = 7). It is associated with only two lexical equivalences: imaginar (to imagine) (n = 2) and suponer (to suppose) (n = 5). These two cases exemplify an extension of the elaborated meaning, suggesting that even in its earliest phase within the analyzed corpus, the construction had begun to diverge from a literal referential meaning and was employed for conjectural or fictitious purposes. It is noteworthy that no occurrences are associated with the basic meaning, such as to count in an arithmetic or literal sense. This suggests that this value was no longer productive in the language of the time or was in the process of functional displacement.

During the 20th century, there was a considerable expansion in the use of the construction (26.67% n = 180 of the total), as well as a diversification of lexical equivalences. Notably, the corpus includes novel entries such as contar (to count) and recapitular (to recapitulate), which point to the fundamental meaning or its immediate elaboration. However, these equivalences remain marginal, with only two instances each, accounting for a mere 1.11% of the total for the century. This suggests that the literal senses of the construction had already been displaced in favor of more abstract uses. Conversely, equivalences with figurarse (to imagine), imaginar (to imagine), and suponer (to suppose) were classified as cases of extension of elaborated meaning. This category is indicative of an evolution towards subjective, hypothetical, or unreal interpretations, which points to the use of hacer de cuenta as an epistemic or simulation operator.

In the 21st century, the trend that was observed in the previous century is consolidated: construction is found in 72.30% (n = 488) of the cases in the corpus and is associated in its entirety with processes of extension of elaborated meaning. The most frequent equivalences are imaginar (to imagine) (n = 209) and suponer (to suppose) (n = 191), followed by figurarse (to picture) (n = 88). These expressions refer to hypothetical mental acts, thereby reinforcing the interpretation that hacer de cuenta has evolved to function as a linguistic resource marking unreality, simulation, or the epistemic attitude of the speaker towards propositional content. The complete absence of equivalences related to the base meaning or its initial elaboration (e.g., to count and to recapitulate) confirms that the literal value of the construction has been completely displaced in contemporary usage.

Thus, hacer de cuenta has undergone a process of gradual semantic change, in which its initial literal meaning has been replaced by increasingly abstract interpretations. This transformation is characterized by a typical pattern of semantic grammaticalization, whereby it evolves from a concrete referential meaning to an inferential, subjective, and discursive one. This transition is exemplified by the lexical equivalences that accompany the construction at each stage, thereby demonstrating that, in contemporary usage, hacer de cuenta functions as a highly grammaticalized expression, associated with pragmatic-discourse functions rather than with complete lexical content.

3.4. Pragmatic–Discourse Characteristics

In pragmatic terms, a grammaticalized construction tends to lose its propositional content and become a unit that guides the interpretation of the utterance or the speaker’s attitude towards the content. From a discourse perspective, grammaticalization typically entails the relocation of the form within the discourse structure. Constructions that initially occupied argumentative positions within the utterance transition to peripheral positions, such as the initial position of the utterance or act, and function as discourse particles.

The form ceases to contribute directly to propositional content and begins to organize the information in the discourse. It does so by indicating logical relationships (cause, contrast, consequence), structural relationships (beginning, continuation, closure), or enunciative relationships (emphasis, reformulation, exemplification).

In essence, the grammaticalization of a word or construction signifies the loss of lexical autonomy and the gain of pragmatic and discourse specialization. Consequently, it transforms into a linguistic instrument capable of modulating the overall meaning of an utterance, structuring discourse, and regulating the communicative dynamics between speakers.

With respect to modal properties, the data demonstrate that hacer de cuenta obtained epistemic and intersubjective modal values throughout the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries, as evidenced by the following examples:

- 15.

- le diré que vuelva mañana. >Emilio se alarmó mostrándose muy preocupado. < e-Laurita, por favor no me hagas eso, por si lo ignoras vivo en Azcapotzalco y para llegar a la oficina hago más de una hora. Haz cuenta del tiempo que necesito para llenar el informe que debo poner en manos del señor Reina mañana sin falta. CEMC-I, Mexico, 20th century.I will tell him to come back tomorrow. >Emilio was alarmed and very worried. < e-Laurita, please don’t do that to me, in case you don’t know, I live in Azcapotzalco, and it takes me more than an hour to get to the office. Do count the time I need to fill out the report that I must put in the hands of Mr. Reina tomorrow without fail.

- 16.

- MTY_026_04_15_B: [¿y la] mesa? mira///(1.5) ¿ves?//ay cositasMTY_026_04_15_A: así van a estar mis hijos/jugando con el aroMTY_026_04_15_C: haz de cuenta que está viendo una mosca parada ahí. AMERESCO-MTY, Mexico, 21st century.MTY_026_04_15_B: [and the] table? look////(1.5) see?//oh, little thingsMTY_026_04_15_A: that’s how my children are going to be/playing with the hoopMTY_026_04_15_C: suppose that he’s looking at a fly standing there.

- 17.

- X: corazón de bambúI: corazón de bambú/haz de cuenta que estás comiendo palmitos o algo así/porque es [muy bueno] Norma culta: nuevas transcripciones, Mexico, 20th century.X: bamboo heartI: bamboo heart/imagine that you are eating palm hearts or something like that/because it is [very good].

In Example (15), the construction means recapitular (to recapitulate) and encodes a deontic modality value. In Example (16), the construction introduces the enunciation of a hypothetical situation; therefore, it encodes an epistemic irrealis modal value that can be glossed as suponer (to suppose). In Example (17), it helps to construct a shared subjectivity between speaker and listener, thus acquiring an intersubjective modal value.

A transformation can be observed in the modal functions associated with hacer de cuenta. This phenomenon explains its process of grammaticalization and discourse specialization, as seen in Table 8.

Table 8.

Lexical equivalences and modal functions.

Consequently, during the 19th century, all instances of hacer de cuenta were associated with suponer (to suppose) and the epistemic irrealis modality. It is employed to denote hypothetical content. This linguistic phenomenon persisted throughout subsequent centuries, accompanied by a progressive diversification of lexical equivalences.

During the 20th century, equivalence with contar (to count) (n = 2) and with recapitular (to recapitulate) (n = 2) is exclusively associated with a deontic modality, which implies obligation, necessity, or command. In contrast, the constructions associated with figurarse (to picture) (n = 39) and imaginar (to imagine) (n = 5) show a marked presence of the intersubjective modality (100% and 91.2%, respectively). For its part, suponer (to suppose) shows a shift towards the epistemic irrealis modality, with 98.75% of cases, suggesting a consolidation of its function as a marker of hypothesis.

In the 21st century, this modal specialization is further accentuated. The equivalences with figurarse (to picture) (n = 88) and imaginar (to imagine) (n = 209) are associated almost exclusively with the intersubjective modality. This indicates that the construction has acquired a discourse function that frames hypothetical statements and, in addition, establishes a shared framework of interpretation between the interlocutors. In all instances (n = 191), suponer (to suppose) manifests a propensity to codify an epistemic irrealis modality.

The results indicate an evolution of hacer de cuenta from predicative and semantically rich uses to more abstract and discourse modal uses. The intersubjective (57.93%, n = 391) and epistemic irrealis (41.48%, n = 280) modalities dominate usage in the 20th and 21st centuries, evidencing a functional shift towards the field of modalization.

The examination of the data yielded evidence indicative of a process of progressive grammaticalization. The construction in question has been observed to acquire discourse functions while retaining, albeit to a lesser extent, its predicative role. This phenomenon is illustrated in Table 9.

Table 9.

Function of hacer de cuenta and its lexical equivalences.

In the 19th century, hacer de cuenta manifests exclusively in the capacity of a predicative head function (n = 7). This finding suggests that its semantic and syntactic functionality had been seamlessly integrated into the sentence structure, effectively functioning as a verb. In the 20th century, a marked functional shift emerges, with 37.78% (n = 68) of instances now functioning as a discourse particle, while 62.22% (n = 112) maintain their role as a predicative head. Figurarse (to picture) exhibits a higher frequency as a discourse particle (82.05%, n = 32), while imaginar (to imagine) and suponer (to suppose) demonstrate a mixed pattern, with a predominance of predicative use (70.18%, n = 40, and 76.25%, n = 61, respectively).

In the 21st century, this trend has been consolidated, with use as discourse particle representing 36.07% (n = 176), while predicative use represents 63.93% (n = 312). In terms of lexical equivalence, figurarse (to picture) maintains a high percentage as discourse particle, 68.18% (n = 60), while imaginar (to imagine) (69.38%, n = 145) and suponer (to suppose) (72.77%, n = 139) retain the role of predicative head.

A comprehensive analysis of the data reveals a gradual transition in hacer de cuenta. The stability of the percentages in the 20th and 21st centuries indicates that grammaticalization is progressing, yet this process coexists with predicative uses. This phenomenon of functional diversity is characteristic of many constructions in grammatical transition.

3.5. Hacer de Cuenta as Discourse Particle

As demonstrated in the analysis, hacer de cuenta has followed the typical path of constructions in the process of grammaticalization. First, there is the lexical stage (19th century), where there is full predicative value and variable inflection. Next, there is the intermediate stage (20th century), where there is functional ambiguity, partial fixation, and semantic loss of predicative value. Finally, there is the discursive stage (21st century), where there is the function of discourse particle, fixed structure, and subjective orientation. Therefore, hacer de cuenta is progressively incorporated into the repertoire of discourse strategies that express simulation, exemplification, and intersubjective appeal.

Furthermore, upon examination of their current uses, other aspects can be identified that are typical of discourse particles. Firstly, it is evident that there exist fixed forms, such as haz de cuenta and haga de cuenta. Secondly, these forms exhibit a high degree of mobility within discursive units. Thirdly, they begin to occur in adjacency with discourse markers, especially o sea (that is) and por ejemplo (for example). A subsequent exposition will provide a concise delineation of the pragmatic functions of hacer de cuenta.

3.5.1. Introducer of Hypothetical or Fictitious Discursive Contexts

As previously mentioned, the lexical equivalences figurarse (to picture), imaginar (to imagine), and suponer (to suppose) are the ones that enable hacer de cuenta to have discourse functions, primarily because they refer to the encoding of events in the mental field. Thus, with hacer de cuenta, the speaker introduces discourse contexts that she/he evaluates as possible, for either expressive or explanatory purposes, as can be seen in Examples (18) to (20):

- 18.

- 465 E: ¿por qué?/o sea por ejemplo ¿a lo- a los dieciocho qué/cómo/cómo pensabas? o/¿o qué?466 I: ¿cómo pensaba?/o sea pensaba que <~que:>/haga de cuenta que/si yo decía “voy a hacer esto” es porque lo voy a hacer ¿no?/y o sea/nadie me podía decir otra cosa/y pues <~pus> ahorita como que ya <~ya:> la piensas más/para hacerlo/como que maduras un poco/a como a <~a:> a los dieciocho. CSCM, Mexico, 21st century.465 E: why?/I mean, for example, at eighteen what/how/how did you think? or/or what?466 I: how did I think?/I mean, I thought that/suppose that/if I said “I’m going to do this” it’s because I’m going to do it, right?/and I mean/no one could tell me otherwise/and then now you think about it more/to do it/like you mature a little/like at eighteen.

- 19.

- MEX_047_04_21_A: [sí]/porque cuando yo ya intenté registrar a Andrés/y haz de cuenta que cuando lo registras y/pones la enfermedad que tenga//te dan una lista de clínicas en las que es atendido/y ya tú pones no sé/médico particular/pero aun así tienes que escribir/[el nombre y la cédu]la del doctor que la está atendiendo. AMERESCO-CDMX, Mexico, 21st century.MEX_047_04_21_A: [yes]/because when I tried to register Andres/and imagine that when you register him/and/write the disease he has//they give you a list of clinics where he is treated/and you choose I don’t know/private doctor/but you still have to write/[the name and the ID] number of the doctor who is treating him.

- 20.

- [I talks about the risks of getting a tattoo]130 I: [supongamos]/supongamos que haz de cuenta/que alguien utiliza las mismas agujas//¿no?/solamente se podría contagiar alguien/de sida//si yo la tatuara///y en el mismo momento/estuviera tatuando a otra persona con las mismas agujas//¿no? CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.130 I: [suppose]/suppose imagine/that someone uses the same needles///right?/only someone/could get AIDS//if I tattooed her///and at the same moment/I was tattooing someone else with the same needles//right?

In Example (18), haga de cuenta allows the speaker to introduce, for explanatory purposes, a hypothetical scenario: si yo decía “voy a hacer esto” (if I said “I’m going to do this”). This hypothetical nature is reinforced by the use of the preterit tense. In Example (19), the same thing happens: haz de cuenta introduces the hypothetical scenario cuando lo registras y pones la enfermedad (when you register him and write the disease). Finally, in Example (20), I also introduces a hypothetical scenario: alguien utiliza las mismas agujas (someone uses the same needles). The presence of suponer (to suppose) reinforces the hypothetical nature of the utterance.

In all the preceding examples, haz de cuenta/haga de cuenta has a function like pongamos (que) (let’s say) when “precede e introduce una situación hipotética que va a usarse como ejemplo” (Fuentes Rodríguez, 2009, p. 251). In such cases, its primary function is to encode epistemic modal values, which can be paraphrased as either suponer (to suppose) or imaginar.

3.5.2. Exemplifier

In other works, it has been posited that hacer de cuenta functions as an exemplification device (Guillén, 2022; Uribe, 2024). In these cases, the discourse particle is proximate to ponte tú (picture!), which, according to Poblete (2008), “[p]resenta el miembro del discurso como un ejemplo, esto es, como una situación concreta que ilustra lo dicho anteriormente o una parte de lo que se está diciendo.” The following examples illustrate this phenomenon:

- 21.

- 664: E: órale/no pues <~pus> sí está canijo/¿no?665 I: mh/pues no canijo/pero pues <~pus> con que pidas bien/lo que pasa es que tú contratas haz de cuenta a Cemex/¿no?//o cualquier compañía que se dedique a hacer concreto. CSCM, Mexico, 20th century.664: E: órale/no, it is difficult/isn’t it?665 I: mh/well, not really/but if you order well/what happens is that you hire, picture Cemex/right?//or any company that is dedicated to making concrete.

- 22.

- MTY_026_04_15_B: [ese se] parece a Dogoberto haz de cuenta Dogoberto//el que te digo que andaba suelto///(2) ese es el arlequín/¡mira con los gatos!/fíjate qué amorazo con los gatos. AMERESCO-MTY, Mexico, 21st century.MTY_026_04_15_B: [that looks] like Dogoberto imagine Dogoberto//the one I told you was on the loose///(2) that’s the harlequin/look at him with the cats!/look how much he loves cats!

- 23.

- I: entonces nosotros le damos la dimensión a más o menos a donde creemos/que le va a quedar al molde/el molde es una cazuela/haga de cuenta este/un molde ¿no? en un en un un cocimiento se pone y entonces ya se le echa primero se moja/para que rechupe lo seco. PRESEEA-PUE, Mexico, 21st century.I: then we give the dimension to more or less where we consider/that it will fit the mold/the mold is a casserole/picture mmm/a mold, right? it is put in an oven and then it is poured first it is wet/to moisten the dry part.

In Examples (21) to (23), haz de cuenta/haga de cuenta introduces a particular example that must be considered in order to progress with the discourse. In the first example, a specific company is highlighted (Cemex); in the second example, the focus is on a particular person (Dagoberto); and in the third example, a type of mold is emphasized (a casserole). It is noteworthy that, in such cases, the conjunction que is frequently omitted.

Additionally, in these cases, exemplification is also linked to functions of focalization, as it “permite concretar o especificar un referente […] y, a partir de esta concreción, se inicia o continúa la argumentación del hablante” (Guillén, 2022, p. 15). Consequently, in explanatory contexts, the construction is used to present an example that illustrates a particular situation, but it is not a matter of imagining for the sake of imagining but rather of facilitating understanding.

Finally, in both of these functions, the intersubjective value of hacer de cuenta is evident. In the case of introducing hypothetical discursive contexts, the speaker is sharing his or her own subjectivity, thereby prompting the interlocutor to imagine or suppose a situation in a manner analogous to the speaker’s own. Conversely, in the context of exemplification and focalization, intersubjectivity is manifested when the speaker focuses on a particular referent to emphasize its importance. This makes it easier for both the speaker and the listener to focus on the same information.

4. Discussion

The analysis of the data enabled the identification of a series of key findings that facilitate comprehension of the semantic–pragmatic trajectory and the grammatical processes that affected hacer de cuenta. In this way, it is possible to clearly delineate the mechanisms of linguistic change that underlie its evolution and to shed light on the syntactic, discourse, and modal aspects that have intervened in its functional reconfiguration.

Firstly, one of the most salient results is the displacement of the original meaning of the construction, contar (to count). In the 19th century, hacer de cuenta occurs exclusively with lexical equivalences associated with the verb suponer (to suppose) (71.43%) and imaginar (to imagine) (28.57%). By the 20th century, and more pronouncedly in the 21st, the scope of its equivalences has expanded. Of particular note is the substantial growth of imaginar (to imagine) and figurarse (to picture), which have emerged as the most salient verbs in the semantic functioning of the construction. Concurrently, suponer (to suppose) maintains its preeminence, accounting for 40.89% of the absolute frequency.

This process involves an extension of the elaborated meaning, a phenomenon that has become increasingly prominent in the 20th and 21st centuries. Indeed, more than 70% of the data corresponds to forms that have acquired new interpretative nuances. These new connotations are mainly associated with the mental processing of unreal, hypothetical, or fictional situations.

The data demonstrate that the evolution of hacer de cuenta can be characterized as a process of re-elaboration and extension of the source meaning, which is accentuated over time. With the exception of the verbs contar (to count) and recapitular (to recapitulate), the equivalences analyzed participate in this movement towards more abstract and functional meanings. This tendency is consistent with general patterns of grammaticalization, in which mental verbs tend to acquire discursive and modal functions.

Secondly, from a syntactic perspective, a significant transition process can be observed. Hacer de cuenta is moving from being a predicative head to acquiring the functions of a discourse particle. Specifically, in the 19th century, the construction occurs exclusively as a verbal head; however, from the 20th century, and more clearly in the 21st century, a substantial part of the data corresponds to uses as a discourse particle (36.15% in total).

In particular, this change is evidence of a process of grammaticalization, in which hacer de cuenta progressively loses its full lexical content to acquire a pragmatic value related to information management (focusing uses), the modality of the utterance (intersubjective uses), and the orientation of the listener towards a specific interpretation (exemplifier uses).

The phenomenon of grammaticalization is also evident in the syntagmatic position of the construction within the utterance. In these centuries, there is a clear tendency for it to move towards the middle and final positions of act and intervention. This pattern demonstrates a movement towards the right periphery. In this regard, Pons Bordería (2016, 2022) has noted that, during the process of grammaticalization, discourse particles can transition from the left periphery to the right periphery, and be in the final position.

Thirdly, in modal terms, hacer de cuenta tends to predominantly express intersubjective (57.93%) and epistemic irrealis (41.48%) values. This distribution suggests that its synchronic uses favor interpretations where the speaker assumes a perspective shared with his interlocutor (intersubjectivity) or constructs hypothetical scenarios without commitment to the truth of the utterance (epistemic irrealis). The virtual disappearance of deontic values (0.59%) underscores the abandonment of the normative uses that may have existed in previous stages.

In summary, it can be posited that hacer de cuenta has undergone a process of semantic, functional, and modal restructuring. For this reason, it has gone from being a fully compositional and predicative expression to being consolidated as a grammaticalized resource with discourse, modal, and intersubjective functions. This transformation exemplifies the mechanisms through which a language evolves to encompass increasingly specialized forms in the organization of communicative interaction.

The analysis of data from the 20th and 21st centuries enabled the formulation of these conclusions, as these periods saw a substantial augmentation of hacer de cuenta. This substantial increase in data availability has enabled the compilation of a sufficient number of examples and a wide array of registers, thereby facilitating the tracing of the process of grammaticalization.

This micro-diachronic analysis facilitates the explanation of the synchronic uses of hacer de cuenta, especially the functions of exemplifier, focalizer, and introducer of hypothetical scenarios. Thus, this type of analysis is very useful for describing the evolution of discourse particles in relatively short periods of time.

In summary, hacer de cuenta is undergoing a process of grammaticalization. This process involves the adoption of a conceptual metaphor, enabling it to transition from concrete meaning, contar (to count), to more abstract ones, such as imaginar (to imagine) and figurarse (to picture). Concurrently, a process of pragmatization is evident, whereby hacer de cuenta and, more specifically, haz de cuenta, is acquiring pragmatic values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.G.E.; methodology, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V.; software, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V.; validation, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V.; formal analysis, A.B.J.V.; investigation, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V.; resources, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V.; data curation, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V., writing—review and editing, J.E.G.E.; visualization, J.E.G.E. and A.B.J.V.; supervision, J.E.G.E.; project administration, J.E.G.E.; funding acquisition, J.E.G.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication of this article was made possible thanks to the support of the projects CIPROM/2021/038 Hacia la caracterización diacrónica del siglo XX (DIA20), Generalitat Valenciana, and PID2021-125222NB-I00 Aportaciones para una caracterización diacrónica del siglo XX, funded by the MCIN7AE/10.13039/501100011033/ and FEDER Una manera de hacer Europa.