Dealing with Idioms: An Eye-Tracking Study of Cognitive Processing on L1, L2 and Heritage Speakers of Spanish

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Idioms and Their Processing

Context: Ana y Pedro tienen un bar con karaoke en Madrid. A menudo la gente se emborracha y causa problemas. En el bar hay muchas peleas entre los clientes. Ana y Pedro han tomado nota de todo lo sucedido y han decidido limitar estrictamente la entrada de personas al bar.

(“Ana and Pedro run a karaoke bar in Madrid. People often get drunk and cause trouble. There are frequent fights among customers. Ana and Pedro have taken note of all incidents and have decided to strictly limit who is allowed to enter the bar.”)

(1) Ana y Pedro tienen una lista secreta. No dejan entrar a ninguna persona que haya causado problemas anteriormente.

(“Ana and Pedro have a secret list. They do not allow entry to anyone who has previously caused trouble.”)

(2) Ana y Pedro tienen una lista negra. No dejan entrar a ninguna persona que haya causado problemas anteriormente.

(“Ana and Pedro have a blacklist. They do not allow entry to anyone who has previously caused trouble.”)

- Literalness, or the extent to which an idiom allows for an alternative literal interpretation;

- Transparency, or the degree to which the idiom’s meaning can be predicted from the meanings of its individual components;

- Familiarity, or the availability of the expression in the mental lexicon; and

- Frequency of use.

1.2. The Processing of Idiomaticity and the Different Speaker Profiles

2. Methodology

2.1. Materials, Preliminary Validation Test, and Areas of Interest

- Full utterance: The full utterance, including the target expression (idiom/non-idiom). Example: Juan y Ana tienen una lista negra/lista secreta;

- Target expression: The word combination that functions as either an idiomatic unit or a non-idiomatic expression. Example: lista negra/lista secreta;

- Key lexical element: The component of the target expression that triggers idiomatic recognition. Example: lista;

- Complementary lexical element: The second lexical component that, together with the first element, forms the idiomatic or non-idiomatic unit. Example: negra/secreta.

2.2. Experimental Design and Measures

- Total reading time (TRT): The cumulative fixation duration across all reading passes on the critical unit, representing overall processing effort.

- First-pass reading time (FRT): The duration of the initial encounter with the critical unit, reflecting the formation of an initial assumption.

- Re-reading time (RRT): The cumulative time spent revisiting the critical AOI after the first pass reading time, reflecting subsequent verification or revision of the initial assumption.

2.3. Participants

- The L1 speaker group consisted of 32 university students aged 18–25, with a gender distribution of 62% women and 38% men. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

- The L2 group included 25 university students in the same age range. All participants were from the United States and reported no Hispanic background. The gender distribution was 58% women and 42% men. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Their first language was English, and they held an officially certified B2 level in Spanish. At the time of the study, they were enrolled in C1-level Spanish courses. Although the participants were tested during a temporary academic stay of three months at Universidad Nebrija, all L2 speakers were permanent residents of the United States. Consequently, their linguistic background reflects the typical acquisition context for L2 learners in the United States, characterized by limited long-term immersion in natural Spanish-speaking environments and primarily classroom-based instruction.

- The heritage speaker group consisted of 20 participants born in the United States in the same age range, with 65% women and 35% men. Nearly 90% reported having two Hispanic parents, and 10% had only one parent of Hispanic origin. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Their first language was English, and they were enrolled in a C2-level Spanish course specifically designed for this speaker profile at the time of the study. All participants permanently resided in the United States and were temporarily enrolled in a three-month academic program at Universidad Nebrija. As a result, their exposure to Spanish reflects the typical linguistic environment of U.S.-based heritage speakers, who generally have not experienced long-term immersion in Spanish-speaking societies beyond this limited academic stay. Early exposure to Spanish was verified through a pre-screening questionnaire, which included information on home language use during childhood, the language spoken by parents, the age at which Spanish exposure began, and current usage patterns. All heritage speakers reported exposure to Spanish from birth or early childhood, with regular home use. In terms of current usage, the group was highly homogeneous: 93% reported actively using Spanish in academic or family contexts.

2.4. Apparatus and Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Track loss: First-pass reading time in the area of the full utterance = 0 ms.

- Fast reading observations: First-pass reading time in the area of the full utterance < 80 ms and second-pass reading time in AOI_1 < 80 ms.

- Slow reading observations: Total reading time in the area of the full utterance > 800 ms.

3. Results

3.1. Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1 Speakers

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) |

| Idiom | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) |

| Percentage difference | 2.70% | −3.73% | −4.35% | −5.12% |

| p-value | 0.565 | 0.643 | 0.360 | 0.940 |

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Comp. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | 255.03 (SE: 19.82) | 210.76 (SE: 19.67) | 239.19 (SE: 20.07) | 223.85 (SE: 20.02) |

| Idiom | 253.92 (SE: 20.01) | 213.80 (SE: 19.89) | 229.19 (SE: 20.11) | 215.97 (SE: 19.81) |

| Percentage difference | −0.44% | 1.44% | −4.18% | −3.52% |

| p-value | 0.974 | 0.652 | 0.522 | 0.970 |

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | 31.11 (SE: 15.31) | 79.32 (SE: 15.29) | 80.61 (SE: 15.26) | 44.15 (SE: 15.36) |

| Idiom | 39.73 (SE: 15.37) | 65.83 (SE: 15.26) | 76.68 (SE: 15.27) | 39.47 (SE: 15.26) |

| Percentage difference | 27.71% | −17.01% | −4.88% | −10.6% |

| p-value | 0.409 | 0.314 | 0.482 | 0.912 |

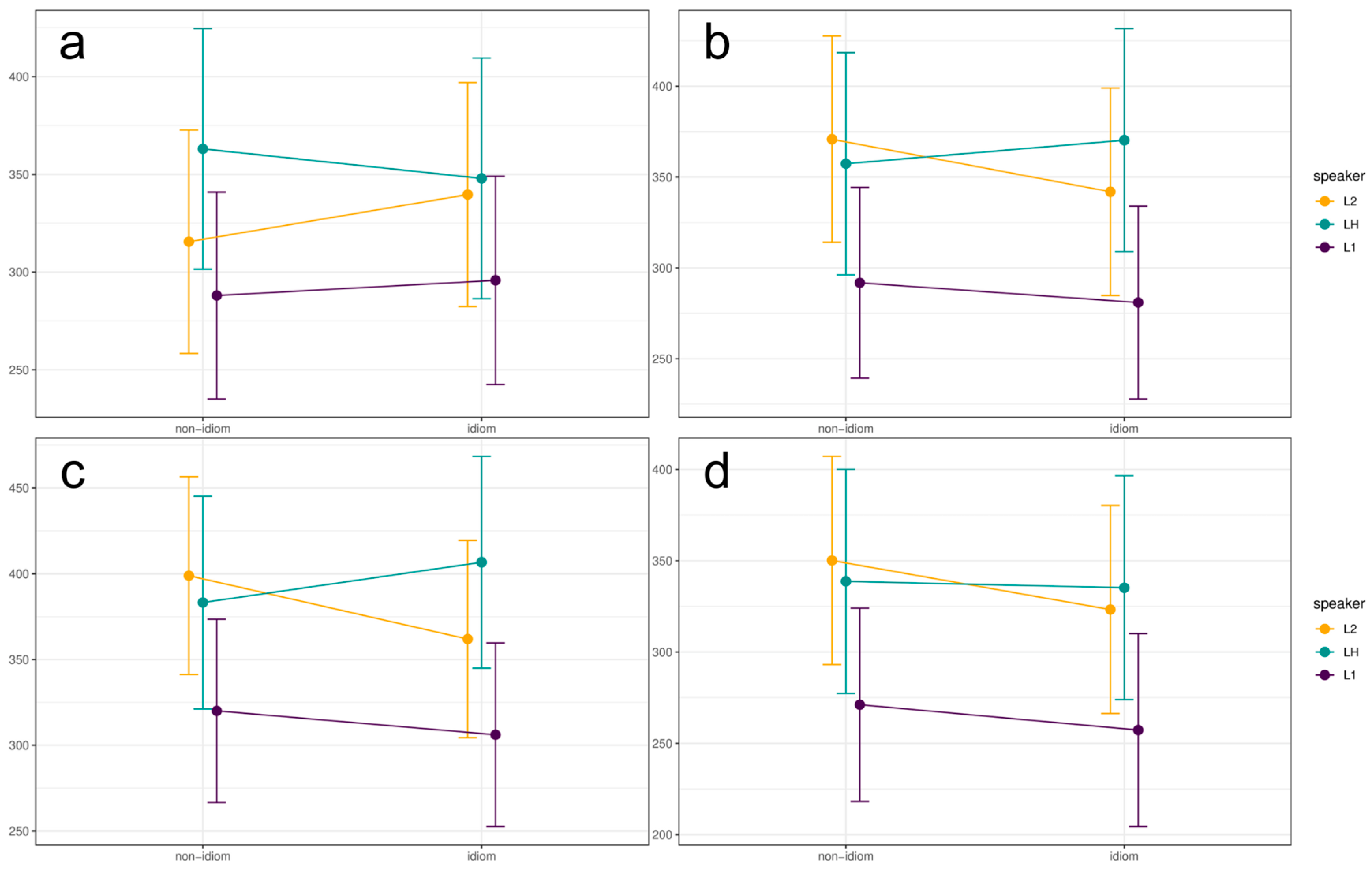

3.2. Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1, L2, and Heritage Speakers

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | L1 | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) |

| L2 | 315.53 (SE: 29.15) | 370.79 (SE: 28.96) | 398.89 (SE: 29.43) | 350.15 (SE: 29.09) | |

| % diff. | 9.56% | 27.08% | 24.65% | 29.13% | |

| p-value | 0.251 | 0.018 | 0.071 | 0.025 | |

| L1 | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) | |

| LH | 363.02 (SE: 31.40) | 357.30 (SE: 31.21) | 383.25 (SE: 31.67) | 338.71 (SE: 31.30) | |

| % diff. | 26.05% | 22.46% | 19.76% | 24.91% | |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.103 | 0.277 | 0.187 | |

| Idiom | L1 | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) |

| L2 | 339.64 (SE: 29.24) | 341.87 (SE: 29.13) | 361.93 (SE: 29.35) | 323.27 (SE: 29.05) | |

| % diff. | 14.83% | 21.7% | 18.24% | 25.65% | |

| p-value | 0.039 | 0.021 | 0.109 | 0.017 | |

| L1 | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) | |

| LH | 347.92 (SE: 31.43) | 370.26 (SE: 31.33) | 406.72 (SE: 31.52) | 335.19 (SE: 31.26) | |

| % diff. | 17.63% | 31.81% | 32.87% | 30.28% | |

| p-value | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.004 |

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 | 339.64 (SE: 29.24) | 341.87 (SE: 29.13) | 361.93 (SE: 29.35) | 323.27 (SE: 29.05) |

| LH | 347.92 (SE: 31.43) | 370.26 (SE: 31.33) | 406.72 (SE: 31.52) | 335.19 (SE: 31.26) |

| Percentage difference | 2.44% | 8.3% | 12.38% | 3.69% |

| p-value | 0.642 | 0.272 | 0.240 | 0.540 |

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Non-idiom | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) |

| Idiom | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) | |

| % diff. | 2.7% | −3.73% | −4.35% | −5.12% | |

| p-value | 0.565 | 0.643 | 0.360 | 0.940 | |

| L2 | Non-idiom | 315.53 (SE: 29.15) | 370.79 (SE: 28.96) | 398.89 (SE: 29.43) | 350.15 (SE: 29.09) |

| Idiom | 339.64 (SE: 29.24) | 341.87 (SE: 29.13) | 361.93 (SE: 29.35) | 323.27 (SE: 29.05) | |

| % diff. | 7.64% | −7.8% | −9.27% | −7.68% | |

| p-value | 0.061 | 0.614 | 0.296 | 0.933 | |

| LH | Non-idiom | 363.02 (SE: 31.40) | 357.30 (SE: 31.21) | 383.25 (SE: 31.67) | 338.71 (SE: 31.30) |

| Idiom | 347.92 (SE: 31.43) | 370.26 (SE: 31.33) | 406.72 (SE: 31.52) | 335.19 (SE: 31.26) | |

| % diff. | −4.16% | 3.63% | 6.12% | −1.04% | |

| p-value | 0.459 | 0.072 | 0.294 | 0.060 |

3.3. Overview

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. On the Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1 Speakers

4.2. On the Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1, L2, and Heritage Speakers

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arunachalam, S. (2013). Experimental methods for linguists. Language and Linguistics Compass, 7(4), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S. D., & Weber, A. (2016). Bilingual and monolingual idiom processing is cut from the same cloth: The role of the L1 in literal and figurative meaning activation. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, S. D., & Weber, A. (2021). Phrasal learning is a horse apiece: No recognition memory advantages for idioms in L1 and L2 adult learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 591364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumans, L. (2006). The attributive possessive in Moroccan Arabic spoken by young bilinguals in the Netherlands and their peers in Morocco. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 9, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehmer, B., & Czachór, A. (2012). The formation and distribution of the analytic future tense in Polish–German bilinguals. In K. Braunmüller, & C. Gabriel (Eds.), Multilingual individuals and multilingual societies (pp. 297–314). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, H., Dobrovol’skij, D. O., Kühn, P., & Norrick, N. R. (Eds.). (2007). Phraseologie: Ein internationales handbuch zeitgenössischer forschung = Phraseology: An international handbook of contemporary research (Vols. 1 and 2). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciari, C., & Glucksberg, S. (1991). Understanding idiomatic expressions: The contribution of word meanings. In G. Simpson (Ed.), Understanding word and sentence (pp. 217–240). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G. (2021). Psycholinguistic approaches to figuration. In S. A. Soares da (Ed.), Figurative language–intersubjectivity and usage (pp. 307–338). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G., & Conklin, K. (2014). Getting your wires crossed: Evidence for fast processing of L1 idioms in an L2. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17(4), 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G., & Conklin, K. (2017). Cross language lexical priming extends to formulaic units: Evidence from eye-tracking suggests that this idea ‘has legs’. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(2), 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G., & Conklin, K. (2020). Is all formulaic language created equal? Unpacking the processing advantage for different types of formulaic sequences. Language and Speech, 63(1), 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carston, R. (Ed.). (2002). Thoughts and utterances: The pragmatics of explicit communication. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Carston, R. (2012). Relevance theory. In G. Russell, & D. Graff Fara (Eds.), Routledge companion to the philosophy of language (pp. 163–176). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carston, R. (2016). The heterogeneity of procedural meaning. Lingua, 175, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslicka, A. (2006). Literal salience in on-line processing of idiomatic expressions by second language learners. Second Language Research, 22, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślicka, A. B., Heredia, R. R., & García, A. C. (2021). The(re)activation of idiomatic expressions (La(re)activación de expresiones idiomáticas). Studies in Psychology, 42(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, H., & Felser, C. (2006). Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 27(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L. (2014). The comprehension of ambiguous idioms in context. In C. Cacciari, & P. Tabossi (Eds.), Idioms: Processing, structure, and interpretation (pp. 163–200). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, K., & Schmitt, N. (2008). Formulaic sequences: Are they processed more quickly than nonformulaic language by native and nonnative speakers? Applied Linguistics, 29, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronk, B. C., & Schweigert, W. A. (1992). The comprehension of idioms: The effects of familiarity, literalness, and usage. Applied Psycholinguistics, 13(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiarini, C., Hubers, F., & Strik, H. (2022). Learning L2 idioms in a CALL environment: The role of practice intensity, modality, and idiom properties. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 863–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKeyser, R. M. (1997). Beyond explicit rule learning: Automatizing second language morphosyntax. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(2), 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, P., Heagerty, P., Liang, K.-Y., & Zeger, S. (2002). Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R. (2009). Implicit and Explicit Learning, Knowledge and Instruction. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reinders (Eds.), Implicit and explicit knowledge in second language learning, testing and teaching (pp. 3–26). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandell-Vidal, M. V. (2020). Léxico, gramática y procesos cognitivos en la comunicación lingüística. In M. V. Escandell-Vidal, J. Amenós Pons, & A. K. Ahern (Eds.), Pragmática (pp. 39–59). Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrmeir, L., Kneib, T., Lang, S., & Marx, B. (2013). Regression: Models, methods and applications. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, M., & Loureda Lamas, Ó. (2025). Spanish as a heritage language: A global perspective. In M. Lacorte (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of hispanic applied linguistics (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, D. J., & Jenkins, C. (1973). Some effects of context on the comprehension of ambiguous sentence. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R. W. (1980). Spilling the beans on understanding and memory for idioms in conversation. Memory & Cognition, 8, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R. W., & Colston, H. L. (2007). Psycholinguistic aspects of phraseology: American tradition. In H. Burger, D. Dobrovol’skij, P. Kühn, & N. R. Norrick (Eds.), Phraseologie: Ein internationales handbuch zeitgenössischer forschung = Phraseology: An international handbook of contemporary research (Vol. 2, pp. 819–836). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R. W., & Gonzales, G. P. (1985). Syntactic frozenness in processing and remembering idioms. Cognition, 20(3), 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridneva, E. M., Ivanenko, A. A., Zdorova, N. S., & Grabovskaya, M. A. (2023). The processing of Russian idioms in heritage Russian speakers and L2 Russian learners. Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, 21(4), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. J. (2002). The automatic cognate form assumption: Evidence for the parasitic model of vocabulary development. International Review of Applied Linguistics (IRLA), 40(2), 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, K., Nyström, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., & van de Weijer, J. (2011). Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hulstijn, J. H. (2019). An individual-differences framework for comparing nonnative with native speakers: Perspectives from BLC theory. Language Learning, 69, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N., & Nekrasova, T. (2007). The processing of formulaic sequences by second language speakers. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, J., & Garrett, M. (1972). Resolving ambiguity: Effect of biasing context in the unattended ear. Cognition, 1, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundation of cognitive grammar (Vol. 1). Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Libben, M. R., & Titone, D. A. (2008). The multidetermined nature of idiom processing. Memory & Cognition, 36, 1103–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureda, Ó., Cruz, A., Recio Fernández, I., & Rudka, M. (2021). Comunicación, partículas discursivas y pragmática experimental. Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, A. (2009). The linguistic similarities of Spanish heritage and second language learners. Foreign Language Annals, 41, 252–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlock, T., & Heredia, R. R. (2002). 11 Understanding phrasal verbs in monolinguals and bilinguals. Advances in Psychology, 134, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, M. S., Glucksberg, S., & Cacciari, C. (1994). Semantic productivity and idiom comprehension. Discourse Processes, 17, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2006). On the bilingual competence of Spanish heritage speakers: Syntax, lexical-semantics and processing. International Journal of Bilingualism, 10(1), 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2015). The acquisition of heritage languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S., & Rodríguez Louro, C. (2008). Beyond the syntax of the null subject parameter: A look at the discourse-pragmatic distribution of null and overt subjects by L2 learners of Spanish. In The acquisition of syntax in Romance languages (pp. 401–418). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Fernández, F. (2024). Nociones sobre lenguas de herencia. Dirigidas al profesorado de español. In S. Bailini, M. V. Calvi, & E. Liverani (Eds.), El español como lengua de mediación en contextos educativos y profesionales. II congreso de Español como lengua extranjera en Italia (CELEI) (pp. 10–25). Instituto Cervantes. [Google Scholar]

- Noveck, I. A., Griffen, N., & Mazzarella, D. (2023). Taking stock of an idiom’s background assumptions: An alternative relevance theoretic account. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1117847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortony, A., Schallert, D. L., Reynolds, R. E., & Antos, S. J. (1978). Interpreting metaphors and idioms: Some effects of context on comprehension. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 17, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M., Traxler, M. J., & Crocker, M. W. (2000). Ambiguity resolution in sentence processing: Evidence against frequency-based accounts. Journal of Memory and Language, 43(3), 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2018). Heritage languages and their speakers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 372–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, K. (2009). Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(8), 1457–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reichle, E. D., Rayner, K., & Pollatsek, A. (2003). The E-Z reader model of eye-movement control in reading: Comparisons to other models. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 26(4), 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommers, J., Dijkstra, T., & Bastiaansen, M. (2013). Context-dependent semantic processing in the human brain: Evidence from idiom comprehension. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 25(5), 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalowitz, N. (2010). Cognitive bases of second language fluency. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Segalowitz, N., & Hulstijn, J. (2005). Automaticity in bilingualism and second language learning. In J. F. Kroll, & A. M. B. De Groot (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches (pp. 371–388). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siyanova-Chanturia, A., Conklin, K., & Schmitt, N. (2011). Adding more fuel to the fire: An eye-tracking study of idiom processing by native and non-native speakers. Second language Research, 29(2), 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition (2nd ed.). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Swinney, D. (1976). Does context direct lexical access? Midwestern Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Swinney, D., & Cutler, A. (1979). The access and processing of idiomatic expressions. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabossi, P., Fanari, R., & Wolf, K. (2009). Why are idioms recognized fast? Memory & Cognition, 37, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, N. (2008). The effect of working memory, semantic access, and listening abilities on the comprehension of conversational implicatures in L2 English. Pragmatics & Cognition, 16(3), 517–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titone, D., & Libben, M. (2014). Time-dependent effects of decomposability, familiarity and literal plausibility on idiom priming: A cross-modal priming investigation. The Mental Lexicon, 9(3), 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A., Derwing, B., Libben, G., & Westbury, C. (2011). Processing advantages of lexical bundles: Evidence from self-paced reading and sentence recall tasks. Language Learning, 61(2), 569–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, G., Schmitt, N., & Galpin, A. (2004). The eyes have it: An eye-movement study into the processing of formulaic sequences. In Schmitt (Ed.), Formulaic sequences: Acquisition, processing and use (pp. 153–172). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlancker-Sidtis, D. (2003). Auditory recognition of idioms by native and nonnative speakers of English: It takes one to know one. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B. (Ed.). (2004). Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Moreno, R. E. (2001). Representing and processing idioms. UCL Wording Papers in Linguistics, 13, 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Moreno, R. E. (2003). Relevance Theory and the construction of idiom meaning. UCL Wording Papers in Linguistics, 15, 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D. (2011). The conceptual-procedural distinction: Past, present and future. In V. Escandell-Vidal, M. Leonetti, & A. Ahern (Eds.), Procedural meaning: Problems and perspectives (pp. 1–31). Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. (2016). Reassessing the conceptual-procedural distinction. Lingua, 175, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D., & Carston, R. (2007). A unitary approach to lexical pragmatics: Relevance, inference and ad hoc concepts. In R. Burton (Ed.), Pragmatics (pp. 230–259). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. N. (2017). Generalized additive models: An introduction with R. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, A. (2002). Formulaic language and the lexicon. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valero Fernández, P.; Cruz, A.; Teucher, M.; Recio Fernández, I.; Loureda Lamas, Ó. Dealing with Idioms: An Eye-Tracking Study of Cognitive Processing on L1, L2 and Heritage Speakers of Spanish. Languages 2025, 10, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070153

Valero Fernández P, Cruz A, Teucher M, Recio Fernández I, Loureda Lamas Ó. Dealing with Idioms: An Eye-Tracking Study of Cognitive Processing on L1, L2 and Heritage Speakers of Spanish. Languages. 2025; 10(7):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070153

Chicago/Turabian StyleValero Fernández, Pilar, Adriana Cruz, Mathis Teucher, Inés Recio Fernández, and Óscar Loureda Lamas. 2025. "Dealing with Idioms: An Eye-Tracking Study of Cognitive Processing on L1, L2 and Heritage Speakers of Spanish" Languages 10, no. 7: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070153

APA StyleValero Fernández, P., Cruz, A., Teucher, M., Recio Fernández, I., & Loureda Lamas, Ó. (2025). Dealing with Idioms: An Eye-Tracking Study of Cognitive Processing on L1, L2 and Heritage Speakers of Spanish. Languages, 10(7), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070153