In this study, we set out to document, for the first time, the rates of, and the lexical diversity in, adjective intensification among L2 learners of German (L1 English). We additionally attended to the issue concerning whether sociodemographic variables (i.e., length of residence, age, and gender) and individual learner differences (i.e., L2 language proficiency, intensity of exposure to the L2, and L2 socioaffect) can predict (a) the inter-individual variation in syntactic adjective intensification, and (b) the observed intra-individual variation based on a weighted measure of intensifier lexical diversity. We now discuss these issues in accordance with our three RQs and corresponding hypotheses.

5.1. RQ1: General Patterns of Syntactic Adjective Intensification

We first sought to determine at what rates learners of L2 German intensify adjectives, and how the lexical diversity in their intensification practices measures up to what has been reported for L1 German communities. Of the 442 intensifiable adjectival heads in our corpus, 193 were intensified, which corresponds to an intensification rate of 44%. In spoken (standard) German among speakers from Germany,

Stratton’s (

2020) analysis revealed an intensification rate of 37%;

Stratton and Beaman’s (

2025) analysis of Swabian German revealed a rate of 27%;

Pheiff’s (

in press) analysis of Swiss German revealed a rate of approximately 22%. The L2 learners in the present study, it would seem, demonstrate comparatively high rates of intensification. This confirms our first hypothesis, namely that, as has been frequently attested (e.g.,

Lorenz, 1998;

Philip, 2007;

Recski, 2004), L2 learners often ‘overuse’ intensifiers when compared to patterns observed in L1 speech communities (

Czerwionka & Olson, 2020). Several rationales for this overuse have been put forth. According to

Philip (

2007), it may be a way for learners to enhance their (perceived) fluency in a communicative instance, essentially functioning as a compensatory strategy to reinforce their meaning due to limited vocabulary or pragmatic awareness.

Czerwionka and Olson (

2020, p. 24) also maintain that an overreliance on intensifiers in the L2 may result from “the desire to communicate emotion and involvement with others, key pragmatic meanings associated with intensifiers that positively impact interactions” (see also, e.g.,

Baños, 2013). Especially within a sample of L2 learners of German with L1 English, the higher rates may also reflect the fact that the syntactic patterns involving intensifiers are cross-linguistically similar, thus encouraging transfer from the L1 to the L2 (we revisit this more extensively in the next section). Relatedly, the pragmatic meaning of intensifiers is comparable between languages, in that they function as pragmatic devices which can express heightened emotion and involvement. Given the informal environment of data collection (i.e., via a VR experiment), the observed overuse may also reflect L2 learners’ attempt to communicate emotion, subjectivity, and involvement; indeed, as

Taguchi (

2022, p. 326) notes, VR tasks require “greater social-interpersonal demands” and invoke strong affective responses in participants (see also

Taguchi, 2021). That said, we must bear in mind that the reference studies outlined here stem from different corpora (see

Section 2.1), which emphasizes that any comparisons in terms of rates of intensification must be made with caution.

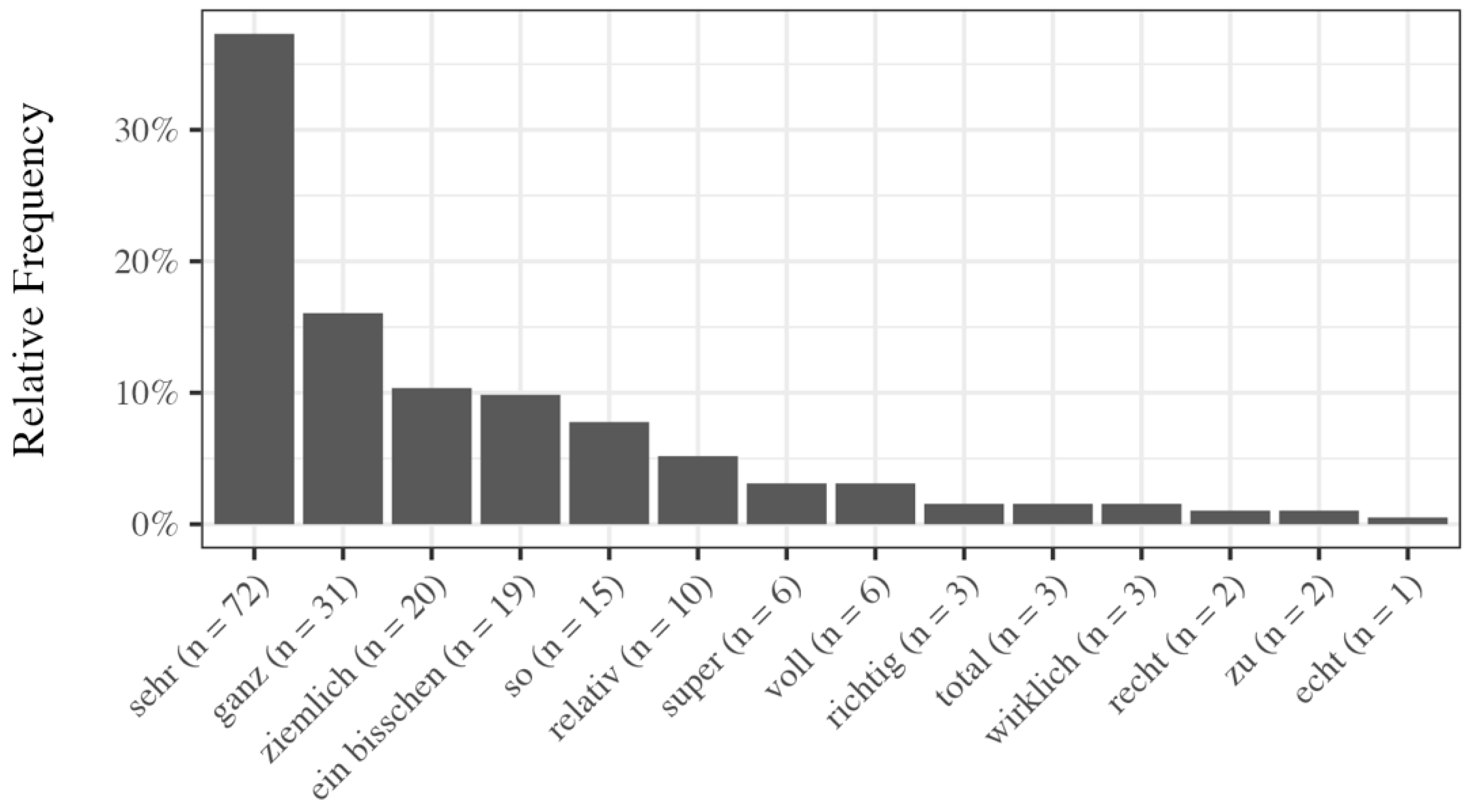

Despite the general overuse of intensifiers, we identified two trends consistent with L1 speech communities. First, rates of amplification (i.e., scaling a quality upward) and downtoning (i.e., scaling a quality downward) were generally consistent with reports from the literature attesting a 70% amplifier and 30% downtowner divide in L1 German (see,

Stratton, 2020, p. 200;

Stratton & Beaman, 2025, p. 122; though cf.

Pheiff, in press, who found amplification rates of approximately 80%). This finding moreover stands in agreement with the cross-linguistically stable insight that amplifier expressions are more frequent than downtoners in terms of both tokens and types (

D’Arcy, 2015, p. 460;

Pintarić & Frleta, 2014, p. 44;

Stratton, 2020, p. 200;

2021, p. 41;

Stratton & Sundquist, 2022, p. 400;

Van Olmen, 2023, pp. 26–27). Second, the lexical manifestations of intensifiers and their relative frequencies bear clear parallels to reports from L1 German communities. In line with

Stratton (

2020),

Stratton and Beaman (

2025), and

Pheiff (

in press), intensifiers such as

sehr ‘very’ and

ganz ‘completely’ rank among the most frequent, alongside

ziemlich ‘rather, quite’,

ein bisschen ‘a bit’ and

so ‘so’.

5.2. RQ2: Predictors of Adjective Intensification

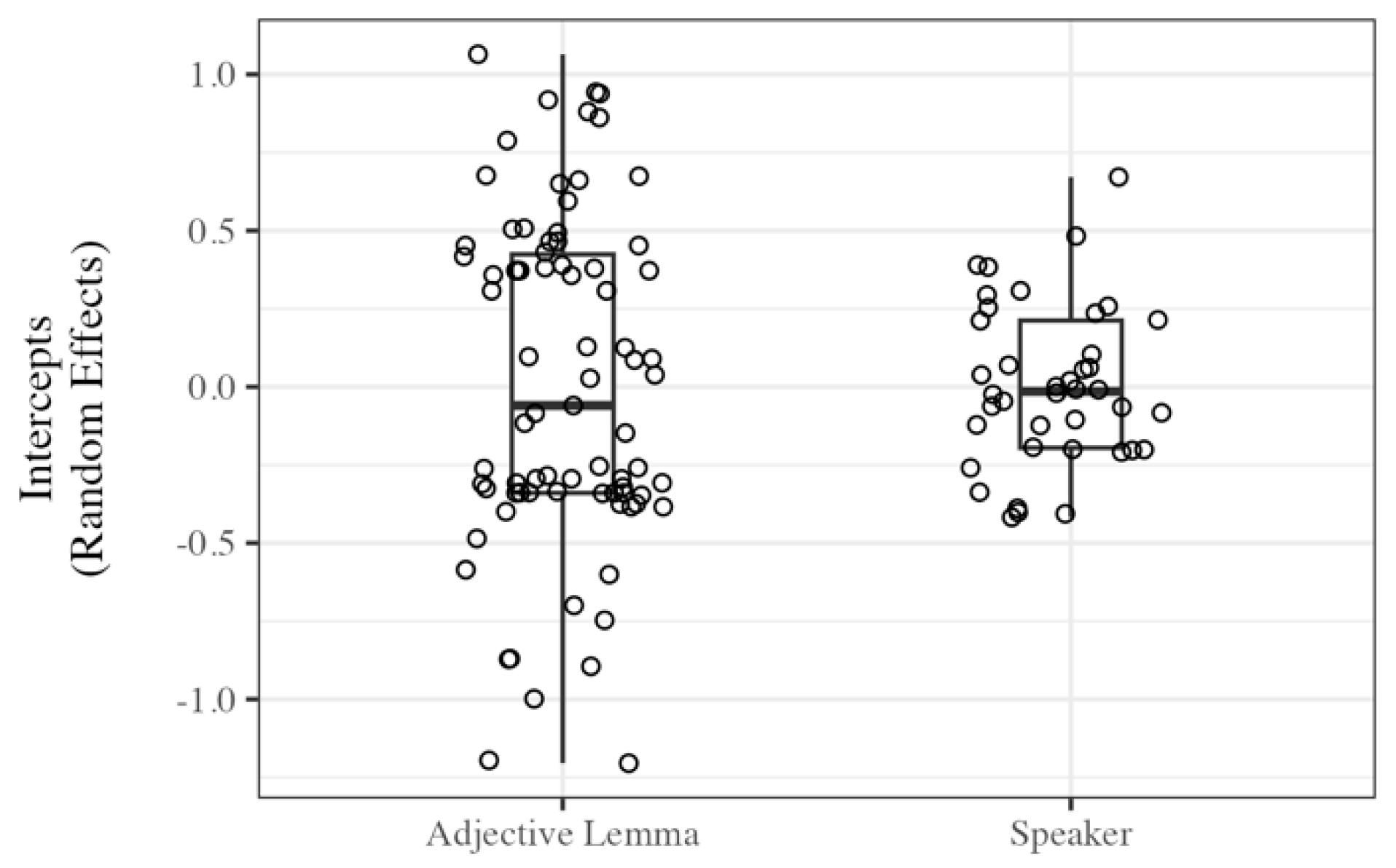

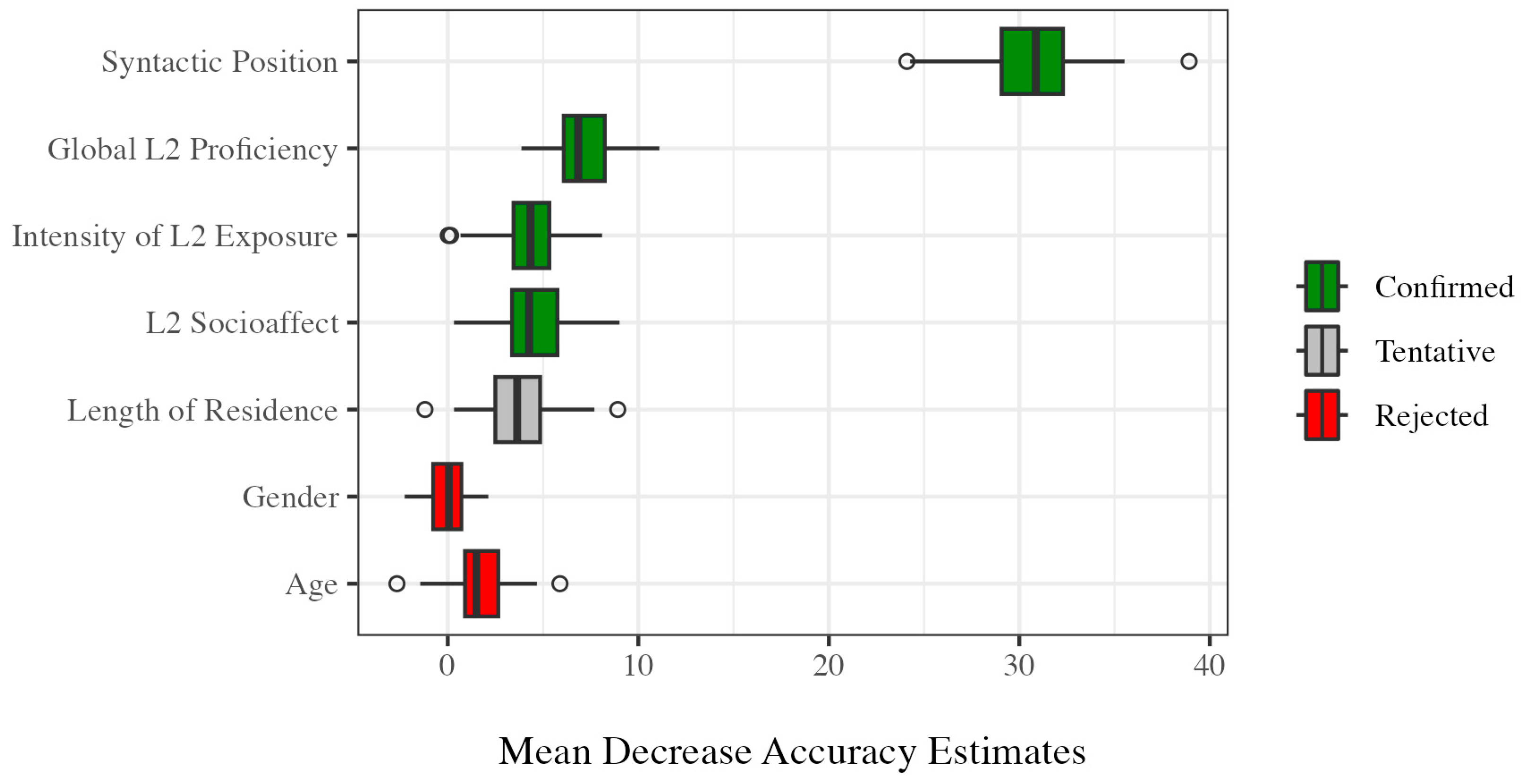

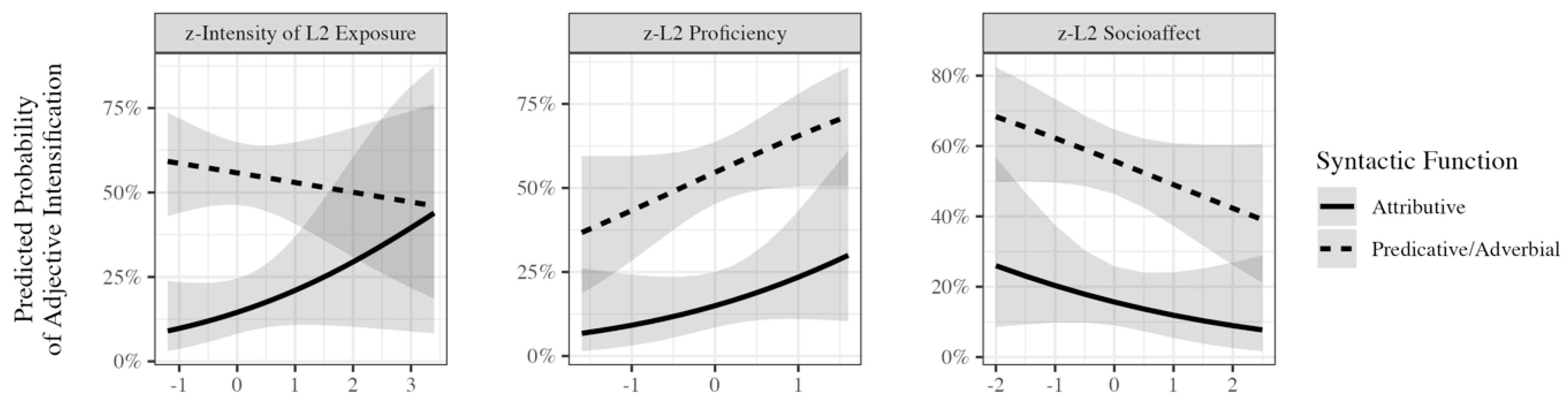

Our second goal was to determine whether any of the sociodemographic variables (i.e., length of residence, age, and gender) or individual learner differences (i.e., L2 language proficiency, intensity of exposure to the L2, and L2 socioaffect) can predict the inter-individual (i.e., between-person) variation in adjective intensification. The Boruta algorithm (i.e., a classification method which aims to provide the best-possible and non-redundant set of constraints that predict the outcome variable) suggested that the effects of the sociodemographic variables were negligible, while the individual learner differences may more successfully predict intensification among L2 speakers of German. We thus submitted the three individual learner difference variables to mixed-effects regression analysis in order to determine their respective predictive power while controlling for the effects of the other covariates and accounting for idiosyncratic variance in the data via random effects (i.e., issues which are not taken into account in the Boruta algorithm). As it turns out, the effects of these three variables—in interaction with the syntactic context of the adjectival head—were non-significant, which, strictly speaking, refutes our second hypothesis. That said, several of the effect sizes were notable; given the data sparsity by virtue of the small corpus, we find it prudent to discuss some of the more pronounced trends we observed and to provide potential explanations for them, also because the Boruta analysis did indicate that these factors are not irrelevant where L2 adjective intensification is concerned.

The most pronounced—but again, non-significant—trends were identified in relation to L2 learners’ intensification of adjectives in relation to global L2 proficiency. That is, more proficient learners tended to engage in higher rates of intensification. This finding is generally in line with previous variationist SLA work attesting that more proficient learners will accommodate, at least to some extent, to the sociopragmatic norms of the L2 community (e.g.,

Davydova, 2024;

Edmonds & Gudmestad, 2014;

Kanwit et al., 2018;

Czerwionka & Olson, 2020), even if they do overshoot in terms of intensification rates. Furthermore, the trend that higher L2 proficiency favors intensification of adjectives in attributive context is conform with insights from diverse SLA scholars focusing on L2 grammatical variation. For example, adjectives in attributive function typically require morphological agreement and specific word order constraints—features of the target language which are acquired later in the developmental process.

Vyatkina et al. (

2015) exemplified in her corpus of written texts by L2 learners of German that beginning learners primarily rely on the predicative use of adjectives, whereas increasingly proficient learners increase their rates of usage of adjectives in attributive function. This trend is not necessarily restricted to L2 German, either, as her findings confirm results from other L2 contexts (e.g., L2 French, L2 English) that associate high frequencies of predicative adjectives with lower L2 proficiency (e.g.,

Hinkel, 2002) and those of attributive adjectives with higher L2 proficiency (

Granfeldt & Nugues, 2007;

Grant & Ginther, 2000). Our results add to this scope of research, corroborating that, not only does the use of attributive adjectives generally increase in relation to L2 proficiency, but so too does the ability to augment them via sociopragmatic devices (i.e., intensifiers).

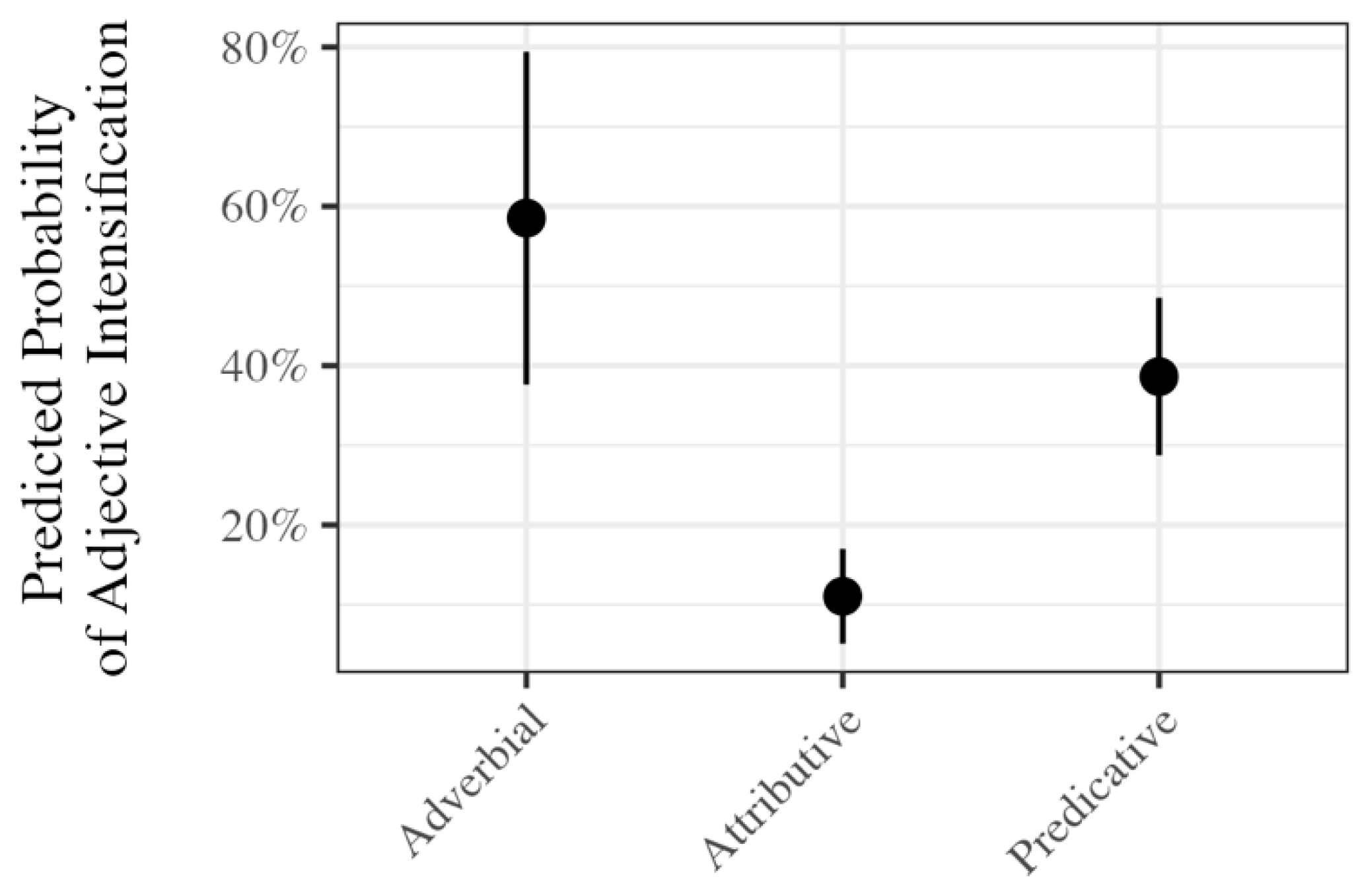

While non-significant, the finding that L2 socioaffect was negatively correlated with adjective intensification was indeed curious, although not necessarily unprecedented in the grander scheme of SLA. Specifically, low L2 socioaffect was associated with extreme overuse of intensifiers, with the model predicting rates as high as 70% in the context of predicative adjectives. L2 learners with a more pronounced affective orientation towards the L2 were, in contrast, predicted to intensify predicatively used adjectives at rates of approximately 40% (see

Figure 4). As we see it, L2 learners reporting higher affective orientation towards the target language may exhibit greater sensitivity to social norms and communicative appropriateness in the target language. Since intensification can carry emotional weight—expressing emphasis, exaggeration, or heightened affect (e.g.,

Baños, 2013)—those who are more socially attuned may avoid overuse to maintain perceived politeness and appropriateness during interactions in the L2. In other words, learners reporting higher affective engagement with the L2 are likely to prioritize pragmatic adaptability, leading them to opt for more measured and contextually appropriate expressions rather than overly frequent intensification. This trend aligns well with insights on the effects of related psychological and affective variables on L2 performance; specifically, factors relating to cultural empathy, open-mindedness, and flexibility are associated with high performance in terms of verbal fluency, vocabulary, phrasal knowledge, and more generally with successful intercultural adaptation and L2 learning (e.g.,

Forsberg Lundell et al., 2018;

Moyer, 2021;

Ożańska-Ponikwia & Dewaele, 2012). For example, in their study of late French L2 learners,

Forsberg Lundell and Sandgren (

2013) emphasized that individuals “who had an open mind and were able to empathize with others led to their engagement with successful learning strategies (including exposing themselves to the L2 community), in order to integrate well professionally and socially” (p. 249).

Collectively, our inter-individual analyses demonstrate that lower-level learners (and, similarly, those with low affective engagement with the L2, i.e., low scores on L2 socioaffect), are less sensitive to target-like frequency (i.e., they tend to either under- or overuse intensifiers compared to L1 speakers) compared to more advanced language learners. One pattern that our qualitative inspection of participant utterances revealed was that, in cases where low-proficiency learners intensified adjectives—both in predicative and attributive function—they did so by way of frequent phrases (e.g.,

ganz normal ‘completely normal’) and/or when the intensification pattern resembled structures especially common for their L1 English (e.g.,

sehr schön ‘very beautiful’,

so groß ‘so big’). The latter effects, we hypothesize, may be a result of cross-linguistic influence, a finding which is by no means unheard of in variationist SLA.

Spina et al. (

2025), for example, who investigated L2 learners of Italian in South Tyrol (the majority of whom spoke L1 German) found that a dominant German-speaking linguistic environment was a significant predictor of learners’ preferences for a syntactic over a morphological intensification type. Among Croatian learners of L2 English,

Lovrović and Pintarić (

2019) similarly maintain that their students employed common adverb–adjective collocations in their L2 English as found in their L1 Croatian; this again points to potential mechanisms of cross-linguistic influence as speakers learn to harness sociopragmatic variation in their L2.

5.3. RQ3: Explaining Intra-Individual Variation in Adjective Intensification

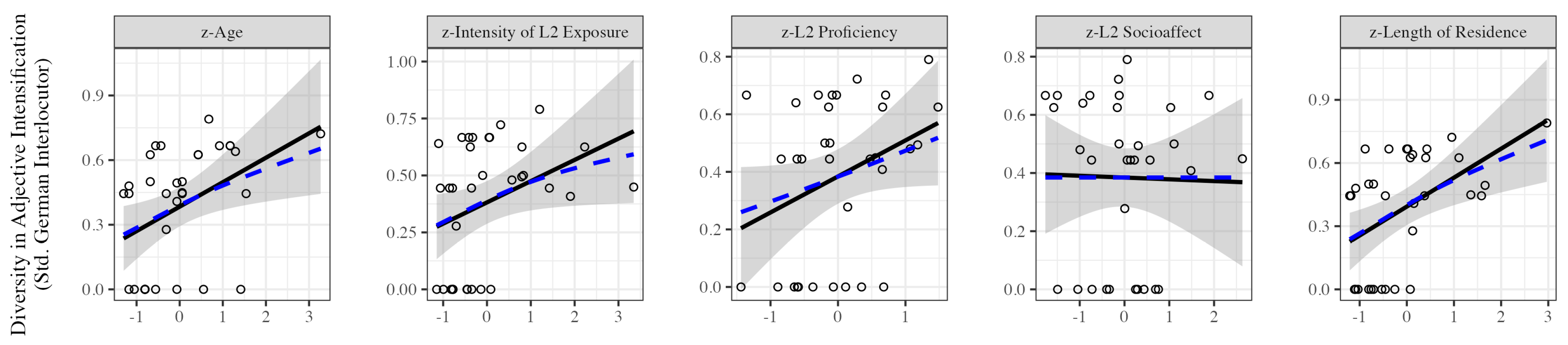

Perhaps the most unexpected finding emerged in relation to the significant differences in the lexical diversity in adjective intensification as a function of the VR interlocutor. Indeed, this analysis did not feature in our original RQs for several reasons: (1) We were interested in L2 learners’ global diversity in adjective intensification, i.e., regardless of potential external influences such as VR interlocutor; (2) rates of adjective intensification did not significantly differ between interlocutors; and (3) in no other analyses has this external factor constrained these L2 learners’ linguistic behavior (see, e.g.,

Wirtz et al., 2024;

Wirtz, 2025). Here, however, we found that the diversity in adjective intensification was higher in interaction with the standard German-speaking VR interlocutor. It seems feasible that we may be observing certain psycholinguistic processes at play. Specifically, standard German is the variety typically employed in, for instance, testing situations, classroom settings, formal interactions, etc., in which enhanced attention to form is encouraged, often resulting from the increased cognitive complexity of the respective activity. From psycholinguistic and SLA research, we know that lexical variety benefits from this increased attention to form induced by task complexity (e.g.,

J. C. Mora et al., 2024;

Robinson, 2001), which may explain the effects of VR interlocutor in terms of L2 learners’ lexical diversity in adjective intensification. Importantly, while the overall rate of intensification did not differ by VR interlocutor, lexical diversity requires not only frequent use but also variation across types. This distinction may help explain why diversity—but not frequency—was affected by VR interlocutor condition.

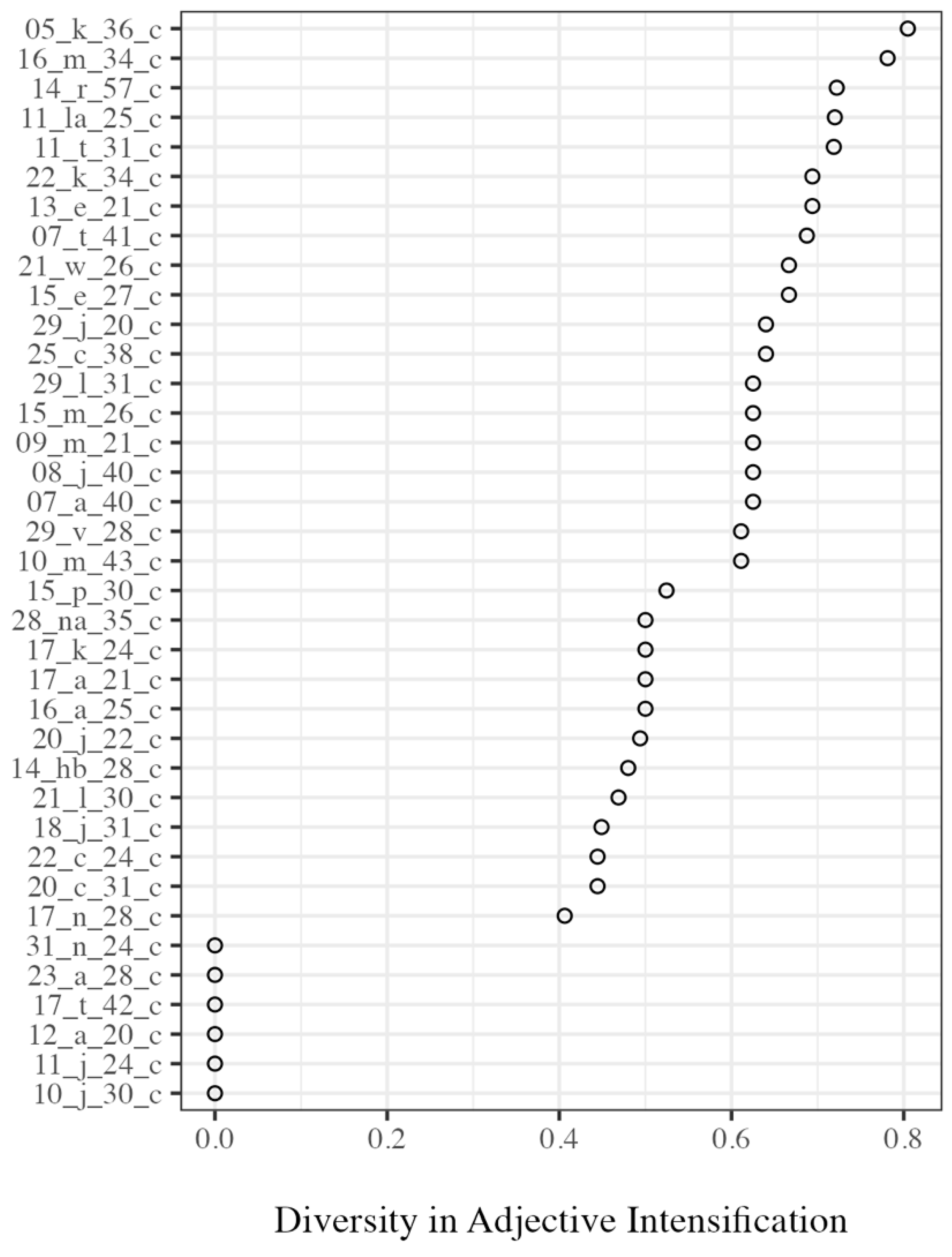

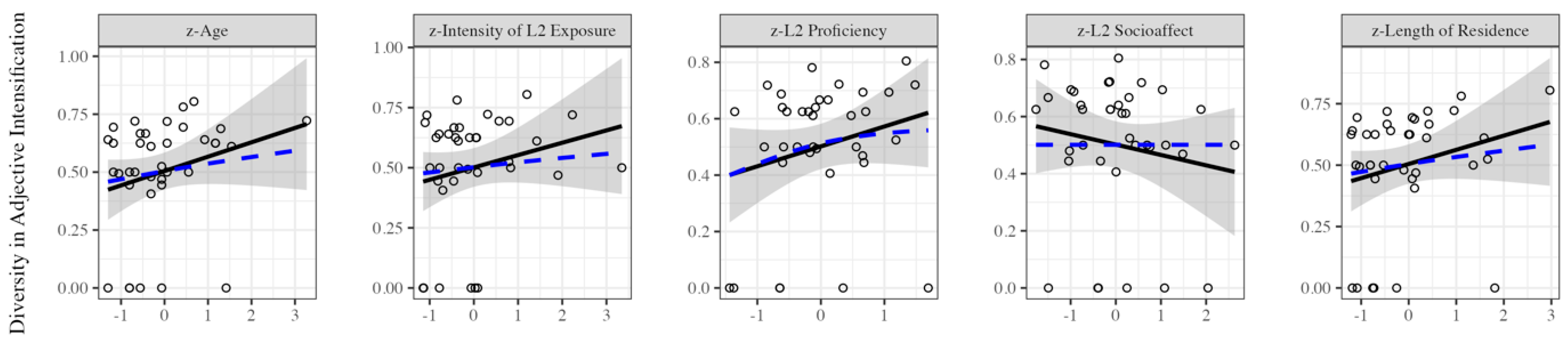

The third and final question we asked was whether intra-individual variation, operationalized as the diversity in adjective intensification based on

Wirtz et al. (

in press) measure of variation intensity, can be predicted by the same set of sociodemographic variables and individual learner differences as used in the inter-individual analyses. At the global level (i.e., variation intensity computed on the basis of L2 learners’ data in interaction with the standard German-speaking and dialect-speaking VR interlocutor), we found only weak and non-significant correlations between the sociodemographic variables and the individual learner differences of interest, which, under a strict interpretation, refutes our third hypothesis. Again, in light of the data sparsity, and also because the weak effects we observed at the global level turned out to be significant in interaction with the standard German-speaking VR interlocutor, a brief discussion of the most prominent trends and their potential explanations seems warranted.

Length of residence in Austria and speaker age exhibited the comparatively strongest positive effects. The effect of length of residence is intuitive when considering previous variationist SLA findings that prolonged exposure to L1 input and increased opportunities for interaction in varied social settings are often associated with more successful acquisition of stylistic and pragmatic variation (e.g.,

Bardovi-Harlig & Bastos, 2011;

Davydova et al., 2017;

Howard et al., 2013;

George, 2014). Our finding also appears reminiscent of the trend that collocational knowledge and lexical diversity are especially susceptible to development in relation to extended stays abroad (e.g.,

Edmonds & Gudmestad, 2014,

2021;

Czerwionka & Olson, 2020). Similarly, the positive—albeit non-significant at the global level—effect of age implies that older speakers tend to demonstrate greater intra-individual variation in adjective intensification, especially in interaction with the standard German-speaking VR interlocutor. Arguably, this may relate to differences in cumulative linguistic experience, i.e., the relationship between cognitive aging and the linguistic repertoire. In this vein, we know that certain cognitive abilities, specifically those relating to fluid intelligence such as working memory, processing speed, and spatial ability decline across the lifespan; meanwhile, crystallized functions such as verbal ability, vocabulary depth, the ability to draw on previously acquired knowledge and experiences, and comprehension tend to increase well into late adulthood (e.g.,

Park & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009;

Murman, 2015;

Rohwedder & Willis, 2010;

Salthouse, 2010). Indeed, developmental psychologists have found that older adults generally demonstrate richer vocabulary and employ more complex grammatical structures compared to younger individuals (e.g.,

Luo et al., 2019). This cumulative acquisition of vocabulary, arguably also including pragmatic devices such as intensifiers, likely transfers to the L2 as well, which may aid in explaining the, albeit weak, correlations between intra-individual variation in adjective intensification and speaker age.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

The present paper has made first strides in documenting the extent to which L2 learners of German acquire patterns of adjective intensification reported for L1 communities. There are, however, several (methodological) limitations which warrant consideration.

First, our corpus was built based on an experimental task originally intending to assess the L2 acquisition of standard German and Austro-Bavarian vernacular varieties. While the VR experiment was useful in facilitating an informal, conversational setting (see also

Wirtz, 2022), arguably representing an optimal site for the analysis of adjective intensification (e.g.,

Ito & Tagliamonte, 2003;

Stratton, 2020), the VR task was relatively short (approximately 15 minutes per participant) and thus resulted in a comparatively small corpus of intensifiable adjectival heads. The present dataset was nevertheless advantageous—and was thus chosen—because it facilitated first hints as to how migrants living in Austria acquire patterns of intensification, and came with an extensive battery of sociodemographic variables and individual learner differences that could be subjected to systematic correlational analyses.

Second, comparisons of L2 learners’ acquisition of intensifier variation with rates of intensification among Austrian speakers could not be made given the dearth of research on the matter in Austria-centered sociolinguistics. Considering the accumulating interest in intensifier variation in L1 German communities (e.g., perceived standard German in Germany (

Stratton, 2020), Swabian German (

Stratton & Beaman, 2025), and Swiss German dialects (

Pheiff, in press)), findings from the Austro-Bavarian and Austro-Alemannic context will undoubtedly aid in identifying salient cross-varietal patterns.

Finally, it has been asserted that L2 overuse of certain intensifiers can negatively impact communication.

Philip (

2007) and

Czerwionka and Olson (

2020) among others maintain that this overuse may be identified as inappropriate or unexpected, too colloquial, or communicating a sense of overstatement, but that these negative effects can often be mitigated by an increase in intensifier lexical diversity—a trend we also observed among high-proficiency learners. These assumptions provide us with a number of testable hypotheses. Much like

DuBois (

2023) questioned whether L2 learners’ use of colloquial lexical items affects L1 speakers’ judgements of their proficiency, future research might explore the extent to which L2 overuse of intensifiers is perceived to hinder effective communication in the target language. It is of additional interest whether different rates of intensification, varying in lexical diversity, modulate these perceptions. Such studies will necessarily address topics of inter- and intra-individual variation, L2 use of lexical and pragmatic devices, and, more broadly, the potential existence of ‘double standards’ in terms of whether L2 speakers suffer the same negative consequences of colloquial language as do L1 speakers without reaping the same benefits.